Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

Unpacking Exclusion, Grievance Redress, and the Relevance of Citizen-Assistance

Mechanisms

Report submitted under Azim Premji University COVID-19 Research Funding Programme 2020

April 2021

In collaboration with:

Project Team

Principal Investigators

Aaditeshwar Seth, Gram Vaani and Indian Institute of Technology Delhi

Aarushi Gupta, Dvara Research

Mira Johri, University of Montreal

Dvara Research Team

Aishwarya Narayan

Nishanth Kumar

Anupama Kumar

Gram Vaani Team

Sultan Ahmad

Arshiya Bhutani

Matiur Rahman

Lamuel Enoch,

Deepak Kumar

Ashok Sharma

Amarjeet Kumar

Lal Ranjan Pappu

Volunteers

1

Ranjan Kumar, Archana Kumari, Abodh Thakur, Dinesh Singh Lodhi, Rajni Kumar Singh, Shyamlal

Lodhi, Lakshman Kumar Singh, Bipin Kumar, Pramod Verma, Naresh Anand, Upendra Kumar,

Nand Kumar Chaudhry, Panna Lal, and Rahul Ranjan.

Tika Vaani

Dinesh Pant

1

Please see Appendix 3 for more details on Gram Vaani’s volunteers.

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................... 1

List of Tables and Figures ..................................................................................................... 2

List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 4

Summary of Findings ............................................................................................................6

1. Project Overview ........................................................................................................... 11

1.1 Background .................................................................................................................................... 11

1.2 Research Methodology ................................................................................................................ 11

1.3 Project Limitations ........................................................................................................................ 15

2. Exclusion from Social Protection Entitlements ............................................................... 17

2.1 Background .................................................................................................................................... 17

2.2 Glossary of Exclusion .................................................................................................................... 22

2.3 Research Methodology ................................................................................................................ 27

2.4 Data Summary ............................................................................................................................... 28

2.5 Data Analysis: Understanding Exclusionary Factors in Social Protection Schemes ............. 30

2.5.1 Typology of Exclusion (All Schemes) .................................................................................... 30

2.5.2 Typology of Exclusion (DBT) .................................................................................................. 32

2.5.3 Typology of Exclusion (MGNREGA) ...................................................................................... 43

2.5.4 Typology of Exclusion (PDS)................................................................................................... 51

2.6 Key Findings: Distilling Trends in Exclusion ............................................................................... 61

Annexure 2A: Exclusion from the Employees’ Provident Fund Scheme .................................. 64

3. Resolving Grievances in Social Protection ...................................................................... 72

3.1 Background .................................................................................................................................... 72

3.2 Research Methodology ................................................................................................................ 73

3.3 Glossary of Action Pathways ....................................................................................................... 74

3.4 Action Pathways for Grievance Redress in Direct Benefit Transfers ..................................... 76

3.5 Action Pathways for Grievance Redress in MGNREGA ............................................................ 87

3.6 Action Pathways for Grievance Redress in PDS ........................................................................ 93

3.7 Key Findings: Resolution Pathways in Social Protection Schemes ...................................... ..99

Annexure 3A: Resolving Grievances in the Employees’ Provident Fund Scheme .................. 101

4. Standard Operating Procedures for Civil Society Organisations .................................... 104

5. Final Recommendations .............................................................................................. 124

Appendix 1: Process Flow of Direct Benefit Transfers ....................................................... 133

Appendix 2: Decision Trees used in Volunteer Interviews ................................................ 135

Appendix 3: Details of Gram Vaani Volunteers ................................................................. 136

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Azim Premji University for giving us this opportunity under their COVID-19

Research Funding Programme 2020. We are excited to be a part of the brilliant cohort of research

organisations selected under the Programme. Gram Vaani’s extensive field engagements with

citizens in the last-mile have been the backbone of this research project. Their work has allowed

the team’s researchers to take a closer look at the various challenges citizens have faced in

accessing social protection entitlements, providing the necessary granularity to our analysis. The

excellent field-level knowledge from the organisation’s Community Managers and volunteers has

added another level of detail to our analysis that would not have been possible without them.

We are also grateful for the crucial feedback we received from Dr. Rajendran Narayanan,

Rakshita Swamy, Aninditha Adhikari, and Sakina Dhorajiwala.

A special note of thanks to Indradeep Ghosh (Executive Director, Dvara Research) and the Dvara

community at large for their continuous support and encouragement. We also owe thanks to our

colleagues at the Social Protection Initiative (Anupama Kumar and Hasna Ashraf) for their

valuable insights at each stage of development of this project.

Protection of Personal Data/Privacy Disclosure:

All personal identifiers, including names, specific identification numbers (ration card number,

universal account number, etc.) were removed from the data that was collected for this research.

Further, the case studies that form part of this project use pseudonyms so as to protect the

identity of the citizens interviewed.

1

List of Tables and Figures

Table 1: Overarching Exclusion Framework

Table 2: Scheme-specific Exclusion Frameworks

Table 3: Glossary of Exclusion

Table 4: Process Flow under DBT

Table 5: DBT Exclusion Framework

Table 6: MGNREGA Exclusion Framework

Table 7: PDS Exclusion Framework

Table 8: PF Exclusion Framework

Table 9: Glossary of Action Pathways

Table 10: Back-end Transmission of DBT Payment Files

Figure 1: The Gram Vaani Model

Figure 2: Scheme-Wise Composition of Specific Complaints

Figure 3: Temporal Progressions of Specific Complaints

Figure 4: Location-wise Distribution of Specific Complaints

Figure 5: Typology of Exclusion (Overarching Framework)

Figure 6: Typology of Exclusion Disaggregated by Scheme (Overarching Framework)

Figure 7: Temporal Progression of Complaints at Pre-Entry Stage

Figure 8: Temporal Progression of Complaints at Entry Stage

Figure 9: Temporal Progression of Complaints at Benefit Processing Stage

Figure 10: Temporal Progression of Complaints at Endpoint Stage

Figure 11: Composition of DBT Schemes

Figure 12: Sources of Exclusion in DBT

Figure 13: Exclusion during DBT Enrolment

Figure 14: Scheme-Wise Exclusion (DBT Enrolment)

Figure 15: Scheme-Wise Exclusion (DBT Failure of Benefit Crediting)

Figure 16: Scheme-Wise Temporal Progression of DBT Complaints

Figure 17: Temporal Progression (Failure of Benefit Crediting)

Figure 18: Temporal Progression (DBT Enrolment)

Figure 19: Temporal Progression (DBT Cash Withdrawal)

Figure 20: Sources of Exclusion in MGNREGA

Figure 21: Exclusion during MGNREGA Benefit Processing

Figure 22: Exclusion in Work Allocation and Wage Payment Processing

Figure 23: Temporal Progression of MGNREGA Complaints

Figure 24: Comparing Sources of Exclusion (COVID-19 PDS Ex-Gratia Transfers vs. Monthly PDS)

Figure 25: Details within Sources of Exclusion at Entry Stage (Total PDS System)

Figure 26: Exclusion during Ration Collection

2

Figure 27 & 28: Exclusion under Non-Compliance (COVID-19 PDS Ex-Gratia Transfers vs. Monthly PDS)

Figure 29: Sources of Exclusion in Employees’ Provident Fund

Figure 30: Exclusion during Enrolment Procedures

Figure 31: Exclusion under Completion of Employee Records

Figure 32: Flowchart of Action Pathways (PM Kisan)

Figure 33: Flowchart of Action Pathways (Pension)

Figure 34: Flowchart of Action Pathways (MGNREGA)

Figure 35: DBT Fund Flow

3

List of Abbreviations

AePS

Aadhaar-enabled Payment System

APB

Aadhaar Payment Bridge

BAO

Block Agriculture Office/Officer

BDO

Block Development Office/Officer

BPL

Below Poverty Line

CEO

Chief Executive Officer

CIDL

COVID-19 Impact on Daily Life Survey

CSC

Common Services Centre

CSO

Civil Society Organisation

CSP

Customer Service Point

CSS

Centrally Sponsored Scheme

DAO

District Agriculture Officer

DBT

Direct Benefit Transfer

DC

District Collector

DM

District Magistrate

DoB

Date of Birth

DoE

Date of Exit

DoJ

Date of Joining

EPF

Employees’ Provident Fund

EPFO

Employees’ Provident Fund Organization

FPS

Fair Price Shop

FPSO

Fair Price Shop Owner

FTO

Fund Transfer Order

GRS

Gram Rozgar Sahayak

IVR

Interactive Voice Response

KYC

Know Your Customer

MIS

Management Information System

MGNREGA

Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act

NeGP

National e-Governance Plan

NFSA

National Food Security Act

NGO

Non-Governmental Organisation

NPCI

National Payments Corporation of India

NSAP

National Social Assistance Programme

PAN

Permanent Account Number

PDS

Public Distribution System

PFMS

Public Financial Management System

4

PHH

Priority Household

PM JDY

Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana

PM Kisan

Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi

PMGKY

Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana

PMT

Proxy Means Testing

PMUY

Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana

PO

Programme Officer

PoS

Point of Sale

PWD

Public Works Department

RTI

Right to Information

RTPS

Right to Public Service

SDM

Sub Divisional Magistrate

SDO

Sub Divisional Officer

SECC

Socio Economic Caste Census

SHG

Self Help Group

SMS

Short Messaging Service

SOP

Standard Operating Procedure

TA

Technical Assistant

UAN

Universal Account Number

UIDAI

Unique Identification Authority of India

5

Summary of Findings

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in India has had far-reaching socio-economic

implications in the form of national lockdowns, consequent suspension of economic activity, and

reversal of internal migration, to name a few. The lockdown particularly led to significant distress

among citizens due to employment loss, wage cuts, transportation and food supply disruption,

and other issues that increased the dependency of people on social protection schemes. Relief

packages by governments included ex-gratia food and cash entitlements delivered using the

Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) and the Public Distribution System (PDS) infrastructure.

i

We also

saw many returning migrant workers from cities turn towards the Mahatma Gandhi National

Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREGA) programme to seek temporary work.

ii

The pandemic

has underscored the necessity of building safety nets. However, it has also brought to surface the

various gaps that have continued to impede the delivery of many welfare interventions. A

plethora of challenges is faced by both prospective and existing beneficiaries attempting to

access their entitlements. These challenges have proven to be difficult to resolve in the absence

of robust grievance redress mechanisms, causing widespread exclusion. Volunteers from civil

society organisations such as Gram Vaani have attempted to intermediate in many of these

instances, assisting citizens in navigating a complex system that is marked by inadequate

transparency and weak accountability structures.

This report is a compilation of our research efforts over the last year. It encompasses an analysis

of the typology of challenges faced by citizens in accessing their entitlements and the resolution

pathways that were used by volunteers to assist such citizens. We cover welfare beneficiaries

across seven DBT schemes

2

, MGNREGA, PDS, and Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) in the states

of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu. Lastly, in addition to broad policy

recommendations, we also propose a set of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that can be a

ready reference for community-based institutions, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), or

government-run help centres, engaged in citizen assistance in the field of social welfare and

accountability.

Understanding Exclusionary Factors in Social Protection

Exclusion may occur in various forms across the many stages of scheme design and

implementation. Using data from Gram Vaani’s Interactive Voice Response (IVR) platform and

2

For the purpose of this study, the set of DBT schemes includes the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-

KISAN), Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY), Pensions, Jan Dhan Yojana, cash transfers under

the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana, Welfare Board schemes (specific to Tamil Nadu), and some

other state-specific transfers. Please note that although MGNREGA wages are transferred through the DBT

system, we have created a separate framework for the scheme given some of its unique features,

including raising work demand and work allocation.

6

deep-dive interviews of beneficiaries selected through critical case sampling, we documented

the various scheme-related challenges citizens faced during March-November 2020. We analysed

a total of 1017 citizen complaints across the aforesaid schemes: DBT (261), MGNREGA (96), PDS

(542), and EPF (118). To understand the typology of challenges citizens faced in accessing welfare

benefits (including those announced in the wake of the outbreak), we developed a framework

that maps exclusionary factors under four key stages of welfare interventions, viz., targeting,

enrolment, back-end processing of benefit, and lastly, disbursement. The key insights that have

emerged from processing the IVR data using this exclusion framework as a guiding tool have

expanded our understanding of welfare access and the existing gaps therein. We summarise

them below:

• The highest incidence of exclusion in DBT schemes

3

occurs during the back-end processing

stage. A variety of reasons (Aadhaar linkage, spelling error, blocked accounts) can lead to

unsuccessful crediting of beneficiary accounts. About 55% of the total DBT-related

complaints from March-June 2020 (the stipulated period for transfers of PMGKY DBT

entitlements) belonged to this category of issues. The prevalence of this exclusion

category in the overall sample indicates the extent of opacity involved in the back-end

processing of all welfare transfers.

• In the context of MGNREGA, we found that 66% of all complaints pertained to either

problems with work allocation or wage payment processing. About 77% of all complaints

falling in the ‘Work Allocation’ category are instances of complete exclusion, i.e. people

not having been allotted any work at all. The scale of the issue has underscored that the

efficacy of the scheme is seriously compromised, even while there is substantial demand

for it. A similar percentage of those calling to report wage issues stated either not having

been paid at all or not having received the full wage due to them.

• Analysis of PDS complaints highlighted that many citizens who needed government

support were excluded from in-kind transfers under PMGKY simply by virtue of not having

a ration card, given the relief package’s eligibility criteria. Secondly, another interesting

aspect that emerged from our analysis is the prevalence of discretionary denial and

quantity fraud by fair price shop officers, wherein people are denied their ration or sent

away empty-handed or with less ration than the entitled quota, with no clear or

documented reasons for the shortfall.

• Most EPF complaints pertained to problems people faced in withdrawing their PF

contributions due to incomplete employee records or inconsistencies in the spelling of

names, date of birth, dates of employment, etc. Lack of cooperation and timely assistance

by employers was found to be a key reason for these issues.

3

Please note that these do not include MGNREGA and PDS.

7

These findings provided us with a worm’s eye view of the welfare ecosystem, helping us

document challenges self-reported by citizens attempting to access their entitlements. Following

this was the next step in our research, which involved understanding how volunteers have

assisted citizens in resolving some of these challenges across schemes in all the four states.

Resolving Grievances in Social Protection

In the second stage of our research project, we studied the various modalities through which

Gram Vaani volunteers assist citizens. Through a detailed qualitative analysis of IVR recordings

and volunteer interviews (to document the actions taken by volunteers), we were able to create

an Impact Framework (analogous to the aforementioned Exclusion Framework) that categorised

volunteer actions under three broad heads (see Glossary of Action Pathways for more detail):

Information Provision to Citizen, Issue Escalation to Higher Officials, and Direct Assistance by

Volunteer. The last action pathway can be further broken down into two sub-categories,

Resolution on Citizen Behalf (in which volunteers fill forms/file complaints on citizen’s behalf)

and Interaction with Access Point (in which volunteers informally negotiate with local access

points to help citizens). It must be noted that the action pathways used by volunteers differ from

one stage of exclusion to another for each scheme. Further, they may not always be successful,

resulting in volunteers using a trial and error method to resolve grievances. A detailed analysis of

this has been provided in Chapter 3. Below we only summarise some of the broad insights:

• Issue Escalation to officials at the block or district level is the most prominent action

pathway used by volunteers across schemes for a variety of citizen grievances. This is

done by forwarding the voice recording of the grievance directly through the IVR to the

appropriate officials, or via WhatsApp or Facebook to their official account. Our analysis

shows that this action pathway is primarily used by volunteers when any one or more of

the following contexts characterises citizen complaints:

o The delivery mechanism of the scheme follows a top-down structure in which

most crucial functions are not in the jurisdiction of local-level officials (such as

those at the Panchayat-level), who, if not more effective, are usually more

accessible to ordinary citizens. This necessitates that the complaint is escalated to

officials at higher tiers who have the official capacity to address grievances.

o In schemes which may follow a more decentralized implementation mechanism

(such as the PDS) but there is prevalence of petty corruption or lack of cooperation

on part of local-level officials.

o There are inadequate or cumbersome official grievance redress mechanisms in

place, that make issue escalation more efficient, or a necessary mechanism to gain

more information.

8

o Other action pathways have proven to be unsuccessful and the issue merits an

escalation to higher officials to ensure that citizens are able to access their

rightful entitlements.

• Local advocacy by writing letters to the administration is also used as an Issue Escalation

pathway for problems that are faced by many citizens in a community. Broad-based

evidence is collected by the Gram Vaani team by running IVR surveys and documenting

the voice reports received on their platforms. Rather than taking an approach of

addressing individual grievances, this method often helped initiate system-wide steps by

the administration to address the problems.

• Resolution on Citizen Behalf as an action pathway has been prominent for schemes (and

certain stages within the scheme) that have some front-end mechanisms in place for

complaint filing, application tracking, data correction, etc., which citizens themselves are

not able to navigate. This occurs in cases where the processes are complex, or resolution

requires access to online portals which citizens are not able to use.

• Interaction with Access Point as an action pathway has been prominent for those cases

in which there is lack of cooperation/non-compliant behaviour on the part of local-level

officials, individual banking agents, or operators of Fair Price Shops. Such interaction may

sometimes also entail warnings given by volunteers, citing the possibility of issue

escalation if the said local functionary does not comply/address the grievance.

This extensive use of mechanisms outside the formal grievance redress mechanisms put up by

the government highlights the gaps that citizens face in grievance redressal. We discuss evidence

in this report indicating that citizens hardly use formal grievance redress mechanisms because of

accessibility barriers, complexity, low trust, or just not feeling empowered enough. They prefer

resorting to CSOs such as Gram Vaani, or other social workers or panchayat representatives, who

are more approachable and aware to deal with the complex citizen-state interface on welfare

schemes. This leads us to make some key recommendations as below.

Key Recommendations

The key observations that emerge from our research is that ensuring access to social entitlements

is impeded by many last-mile problems that citizens are not able to navigate on their own. They

need assistance from CSOs and social workers who are well-versed with the procedures for

various government schemes and can guide them or act on their behalf for smoother citizen-

9

state interactions. This could take the form of escalating issues to appropriate government

officials who have the authority to solve problems, or report to senior officials about violations

by lower-ranking officials, or assist the citizens in filling out appropriate forms, or in some cases

even provide actionable information to the citizens. However, what is clear is that the citizen-

state interface for access to social protection is not seamless by any means, and by-and-large it

cannot be managed by the citizens alone. The introduction of technology is not a solution, and

in fact the centralization of processes that it typically initiates often makes it harder for citizens

to deal with the system, disempowering the very stakeholder that it was meant to support.

The resounding conclusion from our research is that the state-citizen interfaces in welfare

schemes need to be redesigned to become more citizen-centric, and state-run help centres or

community based institutions or CSOs and social workers should be integrated in the

welfare access and grievance redressal processes to make them more accessible to citizens.

Therefore, in addition to recommending a set of systemic improvements that need to be set

in motion using policy levers, we also provide a detailed set of standard operating procedures

that can be used a ready reference by community based institutions and CSOs involved in

resolving citizen grievances in welfare. We also note that given the hyper-local expertise of

such organisations, government departments may choose to embed them as part of their

official grievance redress system, while also adopting simple technological innovations to

ensure more accessible and transparent welfare access and grievance redress systems.

The report has been organised in the following manner. Chapter 1 provides a broad overview of

the project, the key research objectives and the broad research methodology. Chapter 2 and its

accompanying Annexure 2A explore the various causal factors that lead to exclusion of citizens

from social protection schemes and the EPF respectively. Chapter 3 and its accompanying

Annexure 3A provide a detailed description of the various action pathways that Gram Vaani

volunteers employed to resolve these grievances. Chapter 4 consists of a set of Standard

Operating Procedures for community based institutions and civil society organisations,

and Chapter 5 provides broad policy recommendations for various governmental and

banking entities. The appendices at the end of the report include explanation of the various

technical processes under DBT for reference, an excerpt from our volunteer interview

questionnaire, and lastly, further details on the volunteers of Gram Vaani, without whom this

piece of work would not have been possible.

10

1. Project Overview

1.1. Background

The COVID-19 lockdown and subsequent public health measures followed in India to contain the

pandemic spread have severely impacted poor and vulnerable populations on food security,

livelihood, and access to health services

4

. Although the government has mobilized several relied

measures, there has been extensive documentation of exclusion of deserving people from

availing these social protection measures.

5

In this research project, the four collaborating

organisations utilised our collective knowledge and field resources to undertake action research

specific to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the course of last year, teams across

these organisations have been documenting such issues faced by the citizens,

6

understanding

reasons behind the exclusions,

7

assisting them in availing welfare and social security schemes,

8

and advocating for improvement in the operational processes to reduce exclusions.

9

Our three

key research objectives along with the specific research methodology used at each step have

been detailed in the section below.

1.2. Research Methodology

Research Objective 1: Analysis of user-generated content to understand the different challenges

citizens face in accessing social protection entitlements.

Gram Vaani operates a network of voice-based community media platforms in several rural areas

of North India (Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh) and among industrial sector

workers in Delhi NCR and several districts in Tamil Nadu.

iii

The organisation provides an

Interactive Voice Response (IVR) platform, through which users can obtain local news updates,

record their own voice messages requesting help, or simply narrate their own experiences

iv

. The

simple, low-tech innovation permits access to grievance redressal and information that

4

Janta Parliament, https://jantaparliament.wordpress.com/, Aug 16-21, 2020: With representation from across

the country by over 250 speakers, this is an exhaustive documentation of issues facing the citizens, including issues

related to social protection schemes.

5

COVID-19: Analysis of Impact and Relief Measures, https://cse.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/covid19-analysis-of-

impact-and-relief-measures/, Accessed September 5th 2020: A compilation of several surveys, including some

specifically on access to relief measures – Azim Premji University survey of 5,000 households, Gram Vaani survey

of 2,400 people, Dalberg survey of 47,000 households.

6

Mira Johri, Sumeet Agarwal, Aman Khullar, Dinesh Chandra, Vijay Sai Pratap, Aaditeshwar Seth. The First 100

Days: How Has COVID-19 Affected Poor and Vulnerable Groups in India? Under review, August 2020. A policy brief

based on the study is available.

7

Dvara Research and Gram Vaani. Falling Through the Cracks: Case-studies in Exclusions from Social Protection.

Accessed September 5th 2020.

8

Gram Vaani. Campaigns for the Rights and Dignity of the Marginalized, During COVID-19. August 2020.

9

Aaditeshwar Seth, Sultan Ahmad, Orlanda Ruthven. #NotStatusQuo: A Campaign to Fix the Broken Social

Protection Systems in India. August 2020.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

11

marginalised communities generally lack. The organisation also ran awareness campaigns,

targeted towards the low-income group and the migrant workers. The key objective of these

campaigns was to spread awareness about welfare schemes and entitlements announced during

the pandemic. These included, but were not limited to, work opportunities and procedural details

around MGNREGA, accessing PMGKY benefits (food and cash), eligibility rules for schemes like

PM Kisan, among others.

Figure 1 describes the Gram Vaani model in further detail. In March 2020, the Gram Vaani COVID-

19 response network formed in collaboration with 25+ CSOs began documenting people’s

experiences and complaints specific to the national lockdown and socio-economic fallouts of the

pandemic. During the COVID-19 lockdown in India, more than 1 million users called into the

platforms during the first two months of the lockdown itself, and over 20,000 voice reports were

left by the people, describing their experiences or reporting grievances or asking for assistance

to access social protection schemes.

v

The primary data of audio recordings used to fulfil this

research objective was obtained through Gram Vaani’s community media platforms.

We then undertake an exercise to code the grievances based on reasons of exclusion as per

exclusion frameworks developed for the schemes studied. Grievances coded against this

framework help us understand the relative extent of different issues that can lead to exclusion,

such as documentation gaps for scheme eligibility, mismatches in the spelling of names between

Aadhaar and other pieces of documentation, problems in Aadhaar-bank account linkages,

inactive bank accounts, etc. These issues spanned various schemes including, PDS, MGNREGA,

DBT-linked schemes such as PM-KISAN, Jan Dhan, and NSAP, and employment-linked schemes

like PF. We hence select these schemes as our focus for this segment of our research project.

Extensive campaigns were also undertaken by Gram Vaani on some of these schemes, and

therefore rich data already exists to understand the nature of problems that arise on the ground.

Another component of our analysis is a compilation of deep-dive case studies in exclusion, titled

Falling through the Cracks: Case Studies in Exclusion from Social Protection. In this ongoing blog

series, we cover stories of citizens who have been excluded from social protection benefits

delivered as a part of DBT, PDS, and MGNREGA. We analyse these cases as per the

aforementioned exclusion frameworks, to build strong narratives about exclusion on the ground.

Research Objective 2: Understanding the various modalities through which Gram Vaani

volunteers assist citizens in resolving the challenges they face.

When grievances recorded are taken up by volunteers and subsequently resolved, the practice

on Gram Vaani platforms is to record an impact story detailing the process that was followed for

resolution. Gram Vaani has accumulated a rich set of impact stories recorded during the COVID-

19 period about problems resolved with access to government schemes. We develop a coding

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

12

schema for impact stories, to help understand the actions volunteers become required to take

when exclusion occurs at various stages, across various schemes.

Research Objective 3: Proposing a set of Standardised Operating Procedures (SOPs) that can be

used by community based institutions and civil society organisations for grievance redressal.

Many of the systemic improvements that have been proposed in the report require concerted

efforts on the part of governmental departments and the political will to move towards more

inclusive systems. Therefore, for the short-term, we propose a set of procedures that can guide

community based institutions and civil society organisations engaged in social welfare and

accountability in their work. These procedures lay down the various steps that such an

organisation can follow to reduce exclusion at the last-mile and work hand-in-hand with local

government officials to assist citizens in accessing their welfare benefits.

Figure 1: The Gram Vaani Model

The broad components of our research methodology across the aforesaid objectives are as

follows:

Pre-processing of Complaints Data

A subset of approximately 1000 audio recordings that were specifically complaints related to

welfare schemes were compiled after human-moderated transcription of the complaints. At this

step, all personal information was anonymized as well. The data were further coded using the

exclusion frameworks described in the previous section. The dataset was first partitioned

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

13

10

A more detailed methodology for this exercise using illustrative examples is available on request.

according to the scheme to which a recording pertains. For each recording, we identified the

source of exclusion using the information provided by the caller. Using this information, we

decide which stage of the relevant exclusion framework it maps to best, and code accordingly.

10

Analysis of Coded Data

The processed data was analysed to compile aggregate statistics on the prevalence of exclusion

across each stage of welfare delivery. This also included a spatial and temporal analysis of the

complaints. Data summaries and descriptive statistics have been compiled and presented at the

beginning of each chapter.

Deep Dive Case Studies

We also used a critical case sampling approach to identify cases that highlighted archetypal

exclusionary factors and undertook deep-dive interviews to develop written case studies. We

have currently compiled eight such in-depth case studies which provide a local context to

exclusion and provide further information than what is limited to the original recording. These

telephonic interviews adopted a semi-structured format, and were conducted with the

beneficiary and the community volunteer that was assigned to the original case, and sometimes

with concerned local functionaries (such as a Fair Price Shop (FPS) officer, or Common Services

Centre (CSC) operator).

Impact Stories Dataset

The dataset of impact stories provided a clear view regarding how volunteers functioned when

grievances were brought to them. By listening to and organising these audio clips by the actions

taken by volunteers, we were able to create an Impact Framework (analogous to the previous

Chapter’s Exclusion Framework) that categorised volunteer actions based on the resolution

pathways adopted by them.

Interviews with Volunteers and Local Government Stakeholders

A substantial part of our understanding of how citizen grievances are resolved was obtained

through deep-dive telephonic interviews of volunteers from each state in a semi-structured

format. A secondary aspect of our research methodology involved deep-dive interviews with

government officials responsible for the local administration of the welfare schemes. We used

some of our preliminary insights from volunteer interviews and fed them into our interviews with

relevant officials.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

14

A detailed discussion of the research methodologies used for each component of the project has

been provided in the respective chapters.

1.3. Project Limitations

1. Since most of the data analysed were user generated, the level of information varies greatly

across complaints from it being too little to it being very rich and detailed. To ensure

consistency in our analysis, we extracted the relevant information only for a fixed set of

information categories, potentially resulting in either loss of information for some detailed

calls or in missing data for some. However, this limitation was partly countered by

undertaking extensive deep-dive case studies of beneficiaries from the dataset selected

through a critical case sampling approach. Secondly, given that the data is user-generated

(outside of any official grievance redressal portals) and was analysed based on a ‘pull’

mechanism, it must be noted that this study is not representative of the total proportion of

citizens who face challenges in accessing their welfare entitlements. It is also acknowledged

that the citizens who have been able to reach out and report their grievances are only a

fraction of the total number of people who continue to remain excluded from various

schemes.

2. The dataset on citizen complaints has relatively fewer number of calls pertaining to cash

withdrawal compared to the other stages of exclusion. Since our dataset only contains user-

generated complaints, we speculate that this might be the case because citizens may not

generally prefer approaching a civil society organisation to report issues of cash accessibility,

unless they are quite serious (such as CSP/bank manager fraud). One can also argue that this

might happen because of the low prevalence of such problems. However, results from other

action research projects

11

do not lend much credence to that narrative.

3. The dataset comprising of citizen complaints used to document exclusion and the dataset

comprising of impact stories/action pathways do not overlap. That is, the impact stories

analysed in Chapter 3 are not of those complaints that were analysed in Chapter 2. This is

because the audio recordings in each dataset did not have any personal identifiers apart from

citizen names to track a given complaint and its resolution pathway.

4. The project did not cover the assessment of official grievance redress mechanisms currently

being operated by the various Ministries/Departments. The report analyses only those

grievances that citizens reported into our platform either after their efforts with using the

government-run mechanisms had failed or they were not confident or trusting enough to use

those systems. A comprehensive audit of the existing grievance redress systems in welfare is

a critical requirement and this report seeks to set the context for any such future work.

11

A recent study by LibTech India, titled, Length of the Last Mile, finds that MGNREGA workers spend a

considerable amount of time and money in accessing banking infrastructure across the surveyed states.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

15

5. Since the primary data was obtained through voice recordings made by people calling into

the Gram Vaani IVR platforms, this data excludes problems faced by those people who may

not have been able to access the IVR platforms. Technologies, even simple IVR systems that

do not require the Internet or smartphones, are known to introduce their own divides. The

gender divide in technology access is well known, where rural women have lower access to

mobile phones and consequently are less capable of using them.

vi

Further, community groups

marginalized because of caste or other barriers use mobile phones less than more wealthy

groups.

vii

Gram Vaani volunteers do seek out such groups specifically by trying to reach them

proactively rather than only respond to incoming requests, and we plan to do more extensive

research on such categories of exclusionary factors in the future. However, due to this bias in

technology access, the extent of exclusions identified through our analysis is likely to be an

underestimate of the actual situation on the ground.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

16

2. Exclusion from Social Protection Entitlements

2.1. Background

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to surface the various gaps that have

continued to impede welfare delivery in India, for both cash and in-kind welfare transfers. The

urgency to reach citizens in dire need of financial and livelihood support, dictated by the socio-

economic fallouts of the pandemic-induced lockdown, has led to the mobilisation of increased

funds for various social protection schemes.

viii

A relief package, in the form of Pradhan Mantri

Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKY), was also announced by the Ministry of Finance, Government of

India. As part of this scheme, ex-gratia cash transfers were deployed for women Pradhan Mantri

Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) account holders and below poverty line (BPL) pensioners, and free

ration was announced for approximately 80 crore poor citizens.

ix

While the introduction of these

relief measures was timely on the part of the government, their effective delivery to citizens has

been less than ideal. Archetypal last-mile issues, exacerbated by the COVID-19 lockdowns, have

either delayed beneficiaries’ entitlements or, as seen in some cases, led to the failure of receipt

altogether.

x,xi,xii

With COVID-19 ex-gratia transfers as one of the recent interventions, the welfare

landscape in the country has gone through significant changes over the past few years as well, in

particular with the introduction of a new system for digitised transfer of cash benefits under

various schemes in the form of ‘Direct Benefit Transfers’ (DBT). DBT, along with the coupling of

Aadhaar as an identification system and PMJDY bank accounts, has dominated recent welfare

discourse. Most of these efforts have been introduced as policy tools to reduce leakages in

delivery and to eliminate ghost beneficiaries, but have introduced new issues as welfare

beneficiaries continue to flag challenges in accessing their entitlements.

xiii

While some challenges

relate to typical bureaucratic delays, database errors, blocked bank accounts, others may include

discretionary denial of benefit or overcharging by last-mile functionaries. Given the diversity of

delivery issues as well as their source of origin, we developed a framework to systematically

document exclusion in welfare delivery. This framework, by mapping points of exclusion across

four key stages viz., beneficiary identification, enrolment, back-end processing, and

disbursement, provides an overview of the beneficiary journey and the challenges faced therein.

Each process in the framework corresponds to a unique layer of exclusion and helps us document

the problems in the pipelines of welfare delivery.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

17

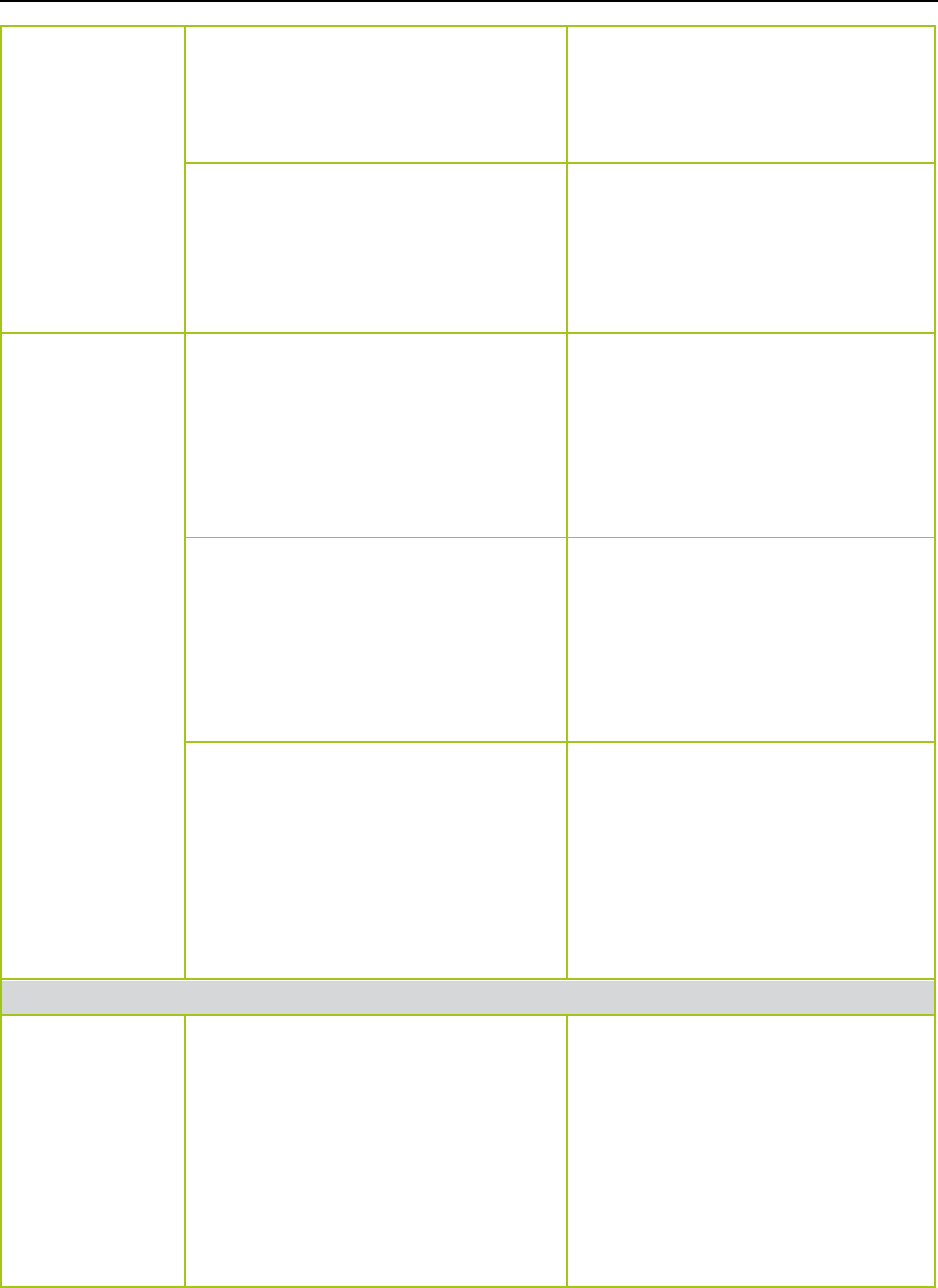

Table 1: Overarching Exclusion Framework

Process Number

Exclusion Stage

Sources of Exclusion

Process 1 (E1)

Pre-Entry

Enumeration Targeting and Eligibility

Rules

Process 2 (E2)

Entry

Proof of Eligibility and Application

Processing

Process 3 (E3)

Benefit Processing

Authorisation and Release of Benefit

Process 4 (E4)

Endpoint

Cash Withdrawal/In-kind Collection by

Beneficiary

Overarching Exclusion Framework

First Stage of Exclusion or E1 (Pre-Entry): The first point of exclusion within the welfare system

is the methodology for identifying beneficiaries. Although a few schemes such as MGNREGA and

PM Kisan allow for self-registration,

xiv

most depend on the Below Poverty Line (BPL), and Socio-

Economic Caste Census (SECC) lists for identifying beneficiaries. The reliability of Proxy Means

Testing (PMT), as seen in the case of identifying deprived households using a BPL list, has been

called into question multiple times in the past. In 2015, the erstwhile Planning Commission,

during a performance evaluation of PDS (a programme that relied on BPL list for identification of

beneficiaries), stated that a large section of the population (particularly daily wage earners) who

have been kept out of the target group because of their income levels, were potentially food

insecure households and therefore the proportion of people with food insecurity need not be

identified with the Commission’s poverty ratio.

xv

Although the more recent SECC is an

improvement over the BPL approach, concerns related to its data have also emerged. Vested

interest to overstate the extent of deprivation by respondents and errors in enumeration leading

to under-counting of the poorest sections are some of the major concerns associated with SECC

(2011).

xvi

Lastly, SECC was conducted in 2011, almost ten years ago, and is therefore not up-to-

date.

xvii

Additionally, the eligibility rules of many schemes by default exclude groups that are in

need of the said safety net, for example, exclusion of informal sector workers from Employees’

Provident Fund

xviii

. Such targeting methodologies and eligibility rules form the first layer of

exclusion. Understanding the exclusion in the targeting stage may help us design more inclusive

ways to identify poor households in the next SECC to be conducted in 2021.

Second Stage of Exclusion or E2 (Entry): Given the targeted nature of most welfare schemes, the

process of enrolment consists of stringent eligibility checks which require the beneficiary to

submit a range of documents to prove their eligibility. Prospective beneficiaries must incur high

costs, for instance, foregoing a day’s wage, having had to make multiple visits to finish the

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

18

enrolment process or procure necessary documents. Secondly, with the introduction of digitised

databases, spelling/linkage errors in beneficiary records during the data entry stage might lead

to the failure of validation checks during the onboarding of beneficiaries. Such errors may take

an inordinately long time to get corrected, given the scarcity of fully functioning enrollment

points. For instance, the functional capacity of enrolment points such as Common Services

Centres (CSC) or local government functionaries (such as the lekhpal

12

or patwari

13

) has been

limited only to the collection and submission of scheme applications but has not been extended

to include functions such as processing corrections in scheme databases, corrections in Aadhaar

details, etc. Record correction processes (a major factor causing inordinate delay in credit of

beneficiary accounts) continue to require action of government departments, often subject to

bureaucratic delays. The lack of a streamlined system, despite the presence of CSCs

14

, and

cumbersome documentation requirements continue to be a source of exclusion at this stage.

Third Stage of Exclusion or E3 (Benefit Processing): For cash transfer schemes, back-end

processing involves the transfer of funds in the form of payment files from the relevant

Ministry/Department to beneficiary accounts via the National Payments Corporation of India’s

digital infrastructure. Most DBT transactions rely on the digital infrastructure of the Aadhaar

Payment Bridge (APB) and are routed using the Aadhaar-enabled Payment System (AePS).

xix

This

stage may be characterised by transaction failures, i.e., failure of crediting a beneficiary’s

account, which may occur due to a variety of reasons.

15

These include improper Aadhaar seeding,

invalidity of account status (blocked/frozen/dormant), pending Know Your Customer (KYC), etc.

Recently, data of failure rates received from four financial institutions with a pan-India presence

reveal an average percentage of AePS failed transactions of 39% across providers in April 2020.

xx

As a rule, we describe all procedures that pertain to the back-end processing of benefits as E3.

For instance, the aspects of work allocation and payment of wages under MGNREGA qualify as

E3. Similarly, issues that potentially disrupt the PDS supply chain have also been bucketed under

E3.

Fourth Stage of Exclusion or E4 (Endpoint): This stage relates to the endpoint of the welfare

chain. Assuming the beneficiary did not fall through any of the previously mentioned fractures in

the welfare pipeline, they may still face issues while withdrawing the cash from their bank

12

A lekhpal is a clerical government officer who primarily maintains revenue accounts and land records at the

village level.

13

A patwari is the lowest state functionary in the Revenue Collection System and is tasked with maintaining

land records and tax collection.

14

In the Pragya Kendra Assessment study, more than four in ten of the survey respondents indicated that they had

to additionally visit an elected official/government official to get their work done, indicating that CSCs were

not functioning as one-stop shops.

15

See relevant case studies: Exclusions in Tamil Nadu’s Labour Welfare System, Exclusion from PM Kisan due to

payment of instalments into wrong bank account, and Exclusion from PM Kisan due to delay in correction of PFMS

records.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

19

account or collecting ration from a fair price shop (FPS). This might sometimes be due to the

unavailability of a cash-out point/FPS (especially exacerbated during the COVID-19 lockdown) or

operational issues such as network failures, biometric failures, and in some cases,

overcharging/fraud/discretionary denial. For instance, Dvara Research’s COVID-19 Impact on

Daily Life (CIDL) survey highlighted that, even before the lockdown was announced, banking

points have not been available in close proximity to many villages present in the sample, and the

residents of those villages had to travel to other villages to avail banking services.

xxi

Even when

they are accessible, networks errors or glitches in Point of Sale (PoS) devices might lead to

multiple visits by beneficiaries, leading to high costs especially for those residing in peri-urban

and rural areas. Further, DBT beneficiaries requiring access to banking services are often

vulnerable to overcharging and fraud

xxii

in the last-mile. This is due to the absence of robust

monitoring mechanisms and the inadequacy of incentives paid out to last-mile

functionaries.

xxiii,xxiv

Scheme-specific Exclusion Frameworks

While these four broad stages in the design and delivery of welfare interventions are common

across schemes, their individual components vary from one scheme to another. Given the unique

nature of each welfare scheme that forms part of this project, we have developed specific

exclusion frameworks that capture the granularity of processes involved in each scheme.

1. Exclusion framework for all DBT schemes: This framework details points of exclusion

common to all DBT schemes, given the common architecture they all rely on for benefit

delivery. The analysis of DBT schemes also includes the various ex-gratia cash transfers

announced under PMGKY.

2. Exclusion framework for MGNREGA: This framework details the various points of

exclusion that are unique to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee

Act (MGNREGA) programme. While wage payments under MGNREGA are made through

DBT, the remaining procedures are characterised by specific exclusionary factors found

only under this programme.

3. Exclusion framework for Public Distribution System: This framework captures points of

exclusion in the Public Distribution System (PDS), an in-kind transfer programme under

the National Food Security Act, 2013.

xxv

The analysis of PDS also includes the various ex-

gratia PDS transfers announced under PMGKY.

4. Exclusion framework for Employees’ Provident Fund: This framework details the various

potential exclusionary stages in the process flow of the EPF scheme, which institutes

provident funds, pension funds and deposit-linked insurance funds for employees of

factories and other establishments under the Employees’ Provident Funds and

Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1952.

xxvi

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

20

Table 2 unpacks these four exclusion frameworks and maps them back to the four key

exclusionary stages. Table 3 provides a glossary of exclusion, defining various sources of

exclusion under each scheme from Table 2.

Table 2: Scheme-specific Exclusion Frameworks

Stage

Scheme

Pre-Entry

Stage (E1)

Entry Stage (E2)

Benefit

Processing

(E3)

Endpoint

(E4)

DBT

Targeting

Methodologies

and Eligibility

Rules*

Documentation

Requirements

Failure of

Benefit

Crediting

Availability of

Access Points

Application

Processing

Operational

Issues

Overcharging

MGNREGA

Not

Applicable

16

Job Card

Application

Processing

Work

Allocation

Availability of

Access Points

Wage

Payment

Processing

Operational

Issues

Overcharging

PDS

Targeting

Methodologies

and Eligibility

Rules*

Documentation

Requirements

Supply Chain

Issues

Accessibility

Application

Processing

AePDS Back-

end

Authentication

Failures

Details in Ration

Card

Non-

Compliance

Employees’

Provident Fund

(EPF)

Targeting

Methodologies

and Eligibility

Rules*

Completion of

Employee

Records

PF

Contribution

Fund

Withdrawal

Issues

Registration

Process (of either

Employer or

Employee)

*Evidence on exclusion during the pre-entry stage has only been documented for ex-gratia PDS transfers under

PMGKY and not for other schemes as it is outside of the scope of this research project.

16

Under MGNREGA, any person who is above the age of 18 and resides in rural areas is entitled to apply for work.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

21

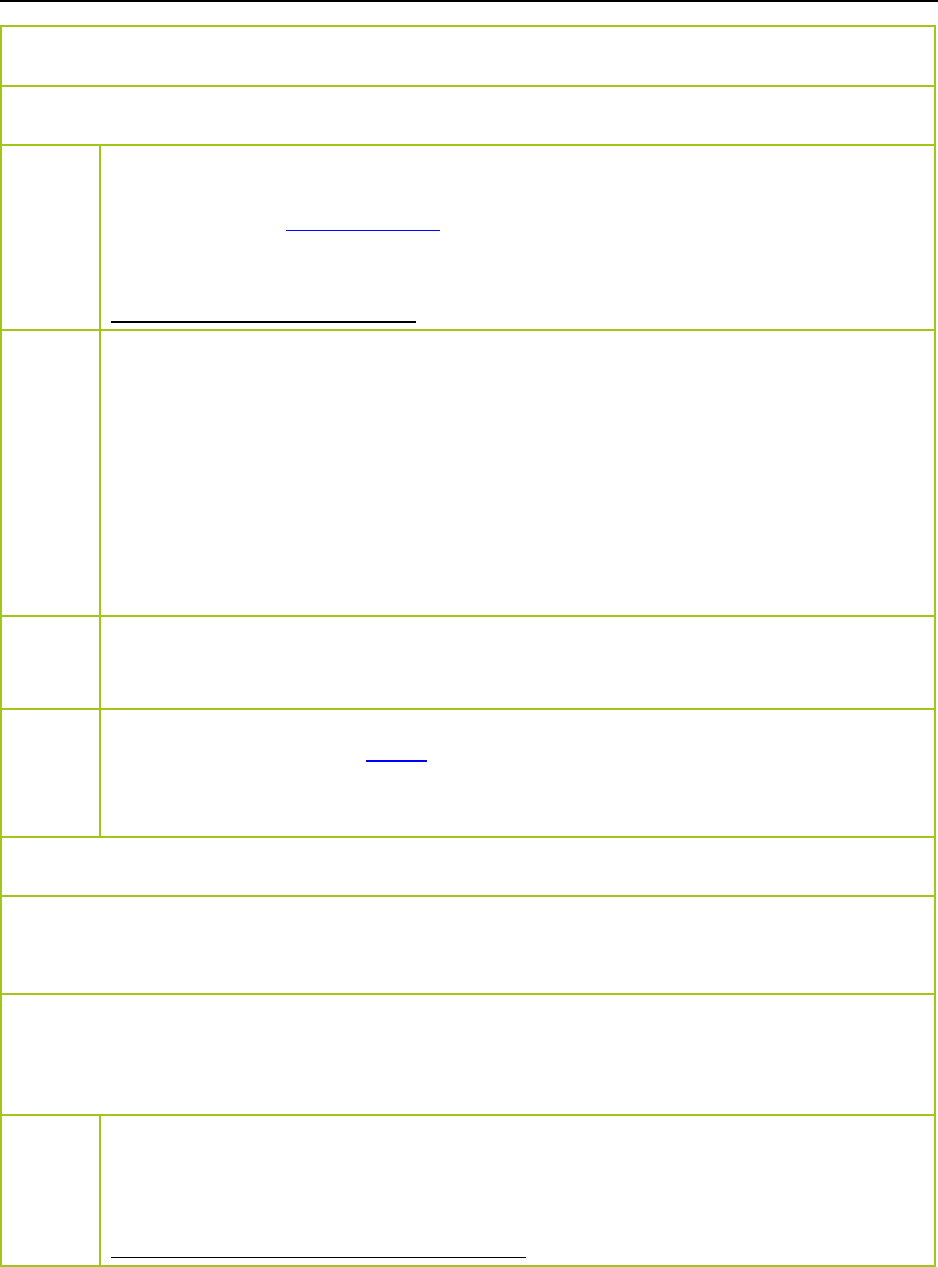

2.2. Glossary of Exclusion

Table 3: Sources of Exclusion- Explained

Exclusion Code

Source of Exclusion

Description

DBT Exclusion

E2 (Enrolment

Procedures)

Documentation Requirements

Scheme applicants bear both time

and monetary costs in order to

procure documents to prove their

eligibility, especially under list-

based schemes.

Application Processing

Inordinate delays in the processing

of scheme applications have

excluded many deserving people

who continue to await the receipt

of their entitlements. General

opaqueness, lack of status

communication, and weak GRM

(Grievance Redressal

Management) make welfare

transfers inaccessible for many

citizens.

E3 (Benefit

Processing)

Failure of Benefit Crediting

The failure to receive DBT

entitlements in one’s bank

accounts. The reasons for failure

may vary, including improper

Aadhaar seeding, database errors,

blocked bank accounts, etc.

E4 (Cash

Withdrawal)

Availability of Access Points

Includes availability of a proximate

banking point to withdraw or check

the status of DBT entitlements.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

22

Operational Issues

Includes issues such as

overcrowding at banks, time-

consuming provision of services,

network failures, cash shortages,

biometric authentication failure,

glitches related to Point of Sale

(PoS) devices, etc. Some of these

issues may not lead to exclusion

necessarily but result in high costs

(both temporal and monetary) for

welfare beneficiaries

Overcharging

Includes instances of bribery,

fraudulent behaviour, or any other

improprieties on the part of cash-

out point personnel.

MGNREGA Exclusion

E2 (Entry Stage)

Job Card Application Processing

Includes issues where a job seeker

is unable to obtain a job card,

despite having enquired

about/applied for the same. This

may be due to non-cooperation

from the enrolment point, or a

processing error post-submission

of documents.

E3 (Benefit

Processing)

Work Allocation

The job cardholder is unable to

obtain work, despite having

requested the same. This category

includes cases wherein cardholders

faced issues in raising their

demand for work and were

consequently excluded from

unemployment benefits. It also

includes the ad-hoc allotment of

work for only a few days despite

requests for longer periods of time.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

23

Wage Payment Processing

Includes all improprieties after

work allocation, such as workers

being unpaid/partially paid or

experiencing payment delays.

E4 (Cash

Withdrawal)

Availability of Access Points

*Same as above*

Operational Issues

Overcharging

PDS Exclusion

E1 (Pre-Entry

Stage)

Targeting Methodologies and

Eligibility Rules

The eligibility rules for identifying

beneficiaries of ex-gratia in-kind

transfers under PMGKY excluded

many people who were in need of

government support but did not

receive free ration due to lack of a

ration card.

E2 (Enrolment)

Documentation Requirements

The citizen is unable to procure the

required documentation to prove

their eligibility as a ration

cardholding candidate.

Application Processing

The citizen has not been allotted a

ration card despite having

submitted the requisite forms and

documentary proof. They may

experience undue delays due to

impropriety at the enrolment

point, or issues with the submitted

documents/forms causing rejection

or stalling of an application.

Details in Ration Card

Citizens may face issues in

updating details on their ration

card. This may pertain to the

addition/deletion of family

members after a change in family

structure or to errors/changes in

addresses, names, etc.

E3 (Benefit

Processing)

Supply Chain Issues

Any disruptions in the

transportation of foodstuff

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

24

between godowns, or from

godowns to the Fair Price Shop can

cause exclusion due to supply

chain issues.

AePDS Back-end

Includes issues related to the

linkage of Aadhaar and ration card

or other backend database issues

that lead to the failure of ration

collection at FPS.

E4 (Ration

Collection)

Accessibility

Implies exclusion due to the

unavailability of a proximate Fair

Price Shop. It also accounts for

improper operation of the Fair

Price Shop in the form of crowding

or erratic hours of functioning.

Authentication Failures

Authentication failures may be

caused by POS device errors,

biometric failures or network

errors that prevent citizens from

collecting their entitled grains at

the Fair Price Shop.

Non-Compliance

Includes all problems caused by

improper behaviour by the Fair

Price Shop Officer, who may

charge higher prices than

stipulated, provide lower quantity

than entitled, or exercise discretion

in how they distribute grain.

PF Exclusion

E2 (Enrolment

Procedures)

Completion of Employee Records

Includes failures due to incomplete

employee records that ultimately

impede withdrawal of PF by

workers: KYC procedures of the

employee must be complete, and

bank details must be in order. The

Date of Joining/Date of Exit

provided must be correct. If the

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

25

employee transfers from one

company to another, either

company must make the requisite

linkages between the old and new

PF accounts.

Registration Process (of either

Employer or Employee)

Inclusive of all issues that may arise

during the registration process:

The company’s registration with

the PF Office may be expired or

incomplete. Second, the employer

may fail to properly register an

employee with the PF Office.

E3 (Benefit

Processing)

PF Contribution

Includes issues where the

employer fails to match the

employee’s contribution to their

provident fund monthly.

E4 (Withdrawal)

Fund Withdrawal Issues

Includes issues employees face

while withdrawing their PF

entitlement due to company

closure or company not

cooperating. Can arise is the

company has shut down and is not

available for approving the

withdrawal application or is not

cooperating to sign-off on the

withdrawal forms.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

26

2.3 . Research Methodology

The database of complaints collected through Gram Vaani’s COVID-19 response network for the

period of March – November 2020 forms a qualitative dataset to study exclusion in a systematic

manner. However, the incoming cases range from specific complaints of exclusion pertaining to

a welfare scheme, to general reports of distress during the COVID-19 lockdown. This report only

covers those complaints that were specific to a welfare scheme from the lens of exclusion and

does not analyse calls related to general distress. The research methodology for this chapter is

detailed below:

Pre-processing of Complaints data

The database of approximately 1000 complaints were compiled after human moderated

transcription of the complaints and all personal information was anonymised. The data was

further coded using the exclusion frameworks described in the previous section. The dataset was

first partitioned according to the scheme to which a recording pertains. For each recording, we

identified the source of exclusion using the information provided by the caller. Using this

information, we decide which stage of the relevant exclusion framework it maps to best, and

code accordingly. In some instances, wherein the caller does not provide enough information

with which to recognise correctly why exclusion occurs, NAs are introduced into the dataset.

Analysis of Coded Data

The processed data was analysed to compile aggregate statistics on the prevalence of exclusion

across each stage of welfare delivery, spatial and temporal analysis of complaints data across

schemes. Data summaries and descriptive statistics have been compiled and presented in the

following sections.

Deep Dive Case Studies

We used a critical case sampling approach to identify cases that highlighted archetypal

exclusionary factors and undertook deep-dive interviews to develop written case studies. We

have currently compiled 8 such in-depth case studies which provide a local context to exclusion

and provide further information than what is limited to the original recording. These telephonic

interviews adopted a semi-structured format, and were with the beneficiary, the community

volunteer that was assigned to the original case, and sometimes with concerned local

functionaries (such as a Fair Price Shop (FPS) officer, or Common Services Centre (CSC) operator).

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

27

2.4 . Data Summary

The dataset of complaints comprises approximately 1000 complaints which have been used to

document exclusion as per the aforementioned frameworks. This overall dataset represents

some of the key social protection measures in India: Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) schemes

17

,

Public Distribution System (PDS), Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act

(MGNREGA), PM Kisan, and Employees’ Provident Fund (PF), among others. Figure 2 provides the

scheme-wise composition of our dataset. As mentioned above, the complaints span the time

frame of March – November 2020. This allows us to understand the occurrence of exclusion

during the COVID-19 lockdown period (which also coincides with the deployment of the COVID-

19 welfare package under PMGKY) and the post-lockdown period.

Figure 2: Scheme-Wise Composition of Specific Complaints

On 22 March 2020, a nationwide lockdown was announced, which closed businesses and

suspended transportation services. This severely impacted people’s livelihoods and their ability

to afford and access essential items. On 26 March, the Finance Minister announced a slew of

relief measures under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana, including direct cash transfers.

17

For the purpose of this study, the set of DBT schemes includes the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-

KISAN), Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY), Pensions, Jan Dhan Yojana, cash transfers under the Pradhan

Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana, Welfare Board schemes (specific to Tamil Nadu), and some other state-specific

transfers. Please note that although MGNREGA wages are transferred through the DBT system, we have created a

separate framework for the scheme given some of its unique features, including raising work demand and

work allocation.

The maximum number of

complaints analysed belong to PDS

(53%) category, followed by other

DBT schemes (26%).

DBT

26%

MNREGA

9%

PDS

53%

PF

12%

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

28

Our dataset witnesses its highest frequency of complaints in April (See Figure 3), corresponding

to the period immediately following the lockdown and relief announcements. Perhaps in the first

phase of lockdown (25 March – 14 April), users required the most assistance or informational

clarifications regarding their welfare entitlements when they were suddenly rendered out of

work and deprived of other income sources. The number of complaints peter down as the months

pass, which may be attributed to several reasons. The severity of users’ living situations may have

tempered down as the lockdown eased up, or they became more familiar with accessing relief-

welfare, requiring the Gram Vaani platform less.

The geographical context for this analysis is described in Figure 4. The state from which most

complaints originate is Bihar at 32%, followed by Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. There are a

considerable proportion of calls for which the origin location is unknown. This geographical

distribution is largely reflective of the strength of the Gram Vaani network in certain areas.

Figure 3: Temporal Progressions of Specific Complaints

0%

20%

40%

60%

Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov

Bihar,

31.96%

Uttar

Pradesh,

20.45%

Tamil

Nadu,

15.54%

Unknown,

12.39%

Jharkhan

d, 7.08%

Madhya

Pradesh,

5.60%

Haryana,

4.42%

Delhi,

1.67%

Other,

0.88%

Most complaints in the dataset

(32%) originate from Bihar, followed

by Uttar Pradesh (21%).

Figure 4: Location-wise Distribution of Complaints

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

29

Number of incoming complaints

peaked in April.

2.5. Data Analysis: Understanding Exclusionary Factors in Social Protection

Schemes

In this section, we provide an overview of the various sources of exclusion that have

been reported under each of the welfare schemes and take a closer look at the various

temporal trends that emerge from the data.

2.5.1. Typology of Exclusion (All Schemes)

Before delving into scheme-specific analyses, it is worth understanding the broad typology

of exclusion in the sample using our overarching framework (Figure 5). The overarching

framework serves to tie exclusion across schemes together, by defining broad stages from

which a citizen may be excluded from any of the welfare schemes within the scope of this

project.

Figure 5: Typology of Exclusion (Overarching Framework)

From Figure 5, it is apparent that Benefit Processing (E3) is the most prominent stage at which

citizens experience exclusion across schemes. The prevalence of this exclusion category in the

overall sample indicates the extent of opacity involved in the back-end processing of all welfare

transfers.

0%

20%

40%

Pre-Entry [E1] Entry [E2] Benefit

Processing [E3]

Endpoint [E4]

The highest incidence of

exclusion occurs during the

‘Benefit Processing’ stage

across all welfare schemes,

followed by ‘Endpoint’.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

30

Figure 6: Typology of Exclusion Disaggregated by Scheme (Overarching Framework)

Further, we identify the prominence of stage-wise exclusion across the four schemes studied

(Figure 6). For both DBT and MGNREGA, we see a prominence of issues at the Benefit Processing

Stage (E3). Benefit Processing (E3) issues are responsible for nearly 85% of all issues amongst DBT

schemes, and approximately 71% of all issues amongst MGNREGA grievances. Analysis in later

sections reveals that the concerning sources of exclusion for these schemes are the processing

of payments (for DBT) and allocation of work and subsequent payment of wages (for MGNREGA).

Complaints at the Pre-Entry (E1) stage are present only for PDS, and not for any of the other

schemes. Even within PDS, it is specifically the ex-gratia in-kind entitlements under PMGKY that

have been marked as exclusion at Pre-Entry (E1). that the Pre-Entry (E1) stage of other schemes

is outside the scope of this project. Finally, issues at the Entry (E2) stage are most prominent in

the PF set of complaints as compared to all other schemes.

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

DBT MNREGA PDS PF

Pre-Entry [E1] Entry [E2] Benefit Processing [E3] Endpoint [E4]

Endpoint (E4) issues are

most prominent for the

PDS, while Benefit

Processing (E3) is a

significant problem in

both DBT and

MGNREGA.

0%

20%

40%

60%

Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov

PDS

0%

20%

40%

60%

Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct

DBT MNREGA PDS PF

Figure 7: Temporal Progression of Complaints at

Pre-Entry Stage

Figure 8: Temporal Progression of Complaints at

Entry Stage

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

31

The graphs above display the time progression of complaints specific to each source of exclusion

(E1 to E4), disaggregated by the scheme. It can be seen from Figure 7 that Pre-Entry (E1) issues

(regarding the PDS) peak in April. About 60% of all Pre-Entry complaints occur in April. This is not

surprising as all Pre-Entry complaints pertain to the ex-gratia PDS transfers, and April was during

the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdown period. Figure 8 shows that Entry (E2) issues peak in

June, mostly due to the PDS related complaints, and Figure 9 shows that Benefit Processing (E3)

issues in April, mostly due to DBT. Finally, Figure 10 displays that Endpoint (E4) issues peaked in

April as well due to PDS related complaints.

2.5.2. Typology of Exclusion (DBT)

Under DBT, beneficiaries enrolled under welfare schemes receive monetary benefits from the

concerned Ministry directly into their bank accounts. The DBT architecture used in the

transmission of monetary benefits involves a variety of agencies, governmental or otherwise, and

a standard operating procedure

xxvii

that guides these actors. Under DBT, the three key processes

involved are detailed in Table 4.

0%

20%

40%

60%

Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov

DBT MNREGA PDS PF

0%

20%

40%

60%

Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov

DBT MNREGA PDS PF

Pre-Entry (E1), Benefit Processing (E3) and Endpoint (E4) complaints peak in April. Whereas

complaints at Entry (E2) peak in June.

Figure 9: Temporal Progression of Complaints at

Benefit Processing (E3) Stage

Figure 10: Temporal Progression of Complaints at

Endpoint (E4) Stage

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

32

Table 4: Process Flow under DBT

18

Process 1

Enrolment

Proof of Eligibility, Application Submission, and

Processing

Process 2

Back-end Transfer

Generation and Transmission of Payment File

Process 3

Withdrawal

Money Withdrawal by Beneficiary

Composition of DBT schemes in the sample: 27% of all complaints pertained to issues in Direct

Benefit Transfer schemes. Figure 11 provides an overview of the composition of the DBT scheme

set.

Figure 11: Composition of DBT Schemes

Identification of Key Exclusionary Factors in DBT

The following section analyses calls across the aforesaid schemes using the DBT exclusion

framework detailed in Table 5 below. We discuss the stages in the order of the frequency in which

they occur in our dataset.

18

For a detailed description of DBT Process Flow, please refer to the Appendix.

Delivery of Social Protection Entitlements in India

33

Table 5: DBT Exclusion Framework

Stage

Scheme

Pre-Entry Stage

(E1)

Enrolment (E2)

Benefit

Processing (E3)

Cash-Out

(E4)

DBT

Targeting

Methodologies

and Eligibility

Rules*

Documentation

Requirements

Failure of Benefit

Crediting

Availability of

Access Points