NAT

COTER

Rural proofing

– a foresight framework for

resilient rural communities

Commission for

Natural Resources

Commission for

Territorial Cohesion Policy

and EU Budget

© European Union, 2022

Partial reproduction is permitted, provided that the source is explicitly mentioned.

More information on the European Union and the Committee of the Regions is available online at

http://www.europa.eu and http://www.cor.europa.eu respectively.

QG-05-22-139-EN-N; ISBN: 978-92-895-1233-6; doi:10.2863/542366

II

This report was written by

Roland Gaugitsch, Isabella Messinger, Wolfgang Neugebauer,

Bernd Schuh (ÖIR); Maria Toptsidou, Kai Böhme (Spatial Foresight).

Language review by Arndt Münch (ÖIR).

It does not represent the official views of the European Committee of the

Regions.

Table of contents

Executive Summary 1

Introduction 3

1. State of play of Rural proofing 7

1.1 Rural proofing in the Better Regulation Agenda 7

1.2 Rural proofing methodologies 8

1.2.1 Rural proofing (Finland) 8

1.2.2 Regional Impact Assessment Statement (Australia) 10

1.2.3 Rural Lens (Canada) 11

1.2.4 Rural proofing (New Zealand) 12

1.2.5 Rural proofing (England) 13

2. Existing TIA tools 15

2.1 TIA Quick Check 16

2.2 RHOMOLO 17

2.3 LUISA 18

2.4 EATIA 19

2.5 TARGET TIA 20

2.6 Territorial Foresight 22

3. The specificities of rural areas 25

3.1 Trends and challenges in rural areas 25

3.2 Impacts on policy planning and assessment tools 31

3.3 Types of rural areas 33

4. Application and improvement of existing methodologies 37

4.1 Rural proofing through Territorial Impact Assessment – TIA Quick

Check 37

4.1.1 Defining the frame of the assessment 38

4.1.2 Systemic picture of effects 40

4.1.3 Assessment of potential impacts 42

4.1.4 Suitability and improvements 43

V

4.2 Rural proofing with a territorial foresight touch – the hypothetical

case of the REPowerEU plan 45

4.2.1 Defining the foresight question 45

4.2.2 Collecting relevant trends, wild cards & challenges 46

4.2.3 Identifying possible future pathways in a participatory

process 47

4.2.4 Analysis and post-processing of possible pathways 49

4.3 Rural proofing through Territorial Impact Assessment – ESPON

EATIA 50

4.3.1 Screening 50

4.3.2 Scoping 51

4.3.3 Assessment and evaluation 53

4.3.4 Suitability and improvements 54

5. Guidance for better rural proofing 55

5.1 Factors for implementing rural proofing 56

5.1.1 Success factors 56

5.1.2 Main challenges 58

5.2 Selecting methodologies 59

5.3 Recommendations 61

5.3.1 Methodological developments 61

5.3.2 Policy developments 63

5.3.3 Supporting measures 64

6. Conclusion 67

6.1 Recommendations for the EU policymaking process 69

6.2 Recommendations for local, regional and national authorities 70

List of interviews 73

Bibliography 75

VI

Tables

Table 1: Additional indicators added to the TIA Quick Check 39

Table 2: Selection of relevant trends, wild cards and challenges

(hypothetical examples) 46

Table 3: Possible relevant future pathways and their implications on

rural areas (hypothetical examples) 48

Table 4: Future-wise rural proofing – Summary table 49

Figures

Figure 1: Population by type of demographic change by urban-rural

typology, 2010-2040 26

Figure 2: Shrinking and growing regions in the European Union 27

Figure 3: Percentage of households with access to Internet >30Mbit/s

in 2019 or latest available year, at the rural and national

levels 30

Figure 4: Typology of “complex shrinking” in rural and intermediate

regions 35

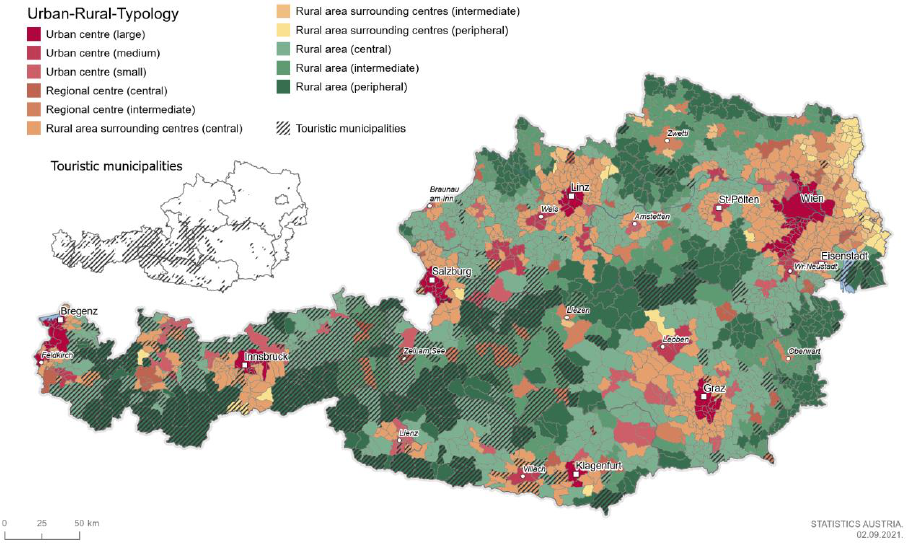

Figure 5: Urban-Rural-Typology of Statistic Austria including

Tourism 36

Figure 6: Systemic picture TIA Quick Check 41

Figure 7: Impact on all regions (left) vs. rural regions (right) 42

Figure 8: Impact classes for all regions (top) vs. rural regions

(bottom) 43

Figure 9: EATIA logic chains 51

Figure 10: Regionalised impacts 52

Figure 11: Impact assessment matrix 53

1

Executive Summary

The study Rural proofing – a foresight framework for resilient rural communities

is focussing on a term that has become in recent years a prominent concept within

rural development. Rural areas are considered as particularly at-risk regarding

disparities and unbalanced impacts of policies on EU level and other levels of

governance, therefore the idea of “rural proofing”, namely ensuring that “thinking

rural” becomes part of the policy design at all governance levels, potential

negative impacts are addressed and positive aspects of a policy are fostered. Rural

proofing is called for by the Cork Declaration 2.0, by the EU long-term-vision on

rural areas and is a declared approach of the 2022 Work Programme of the

European Commission.

Rural proofing is furthermore included in the Better Regulation Agenda at

multiple points. From a methodological point of view it is close to Territorial

Impact Assessment (TIA) as recognised by the Better Regulation Toolbox, tool

#34 in its approach of focussing on assessing impacts based on specific regional

traits and characteristics. Rural proofing however is not only an impact

assessment process, but rather part of the overall policy design. “Thinking rural”

needs to be relevant at all stages, from drafting the initial policy strategy all the

way to impact assessment after implementation.

Based on expert interviews and literature review, an assessment of existing rural

proofing approaches in (mainly) national circumstances was conducted in the

study, identifying main challenges and main success factors for implementing

rural proofing. Building on this knowledge, a grid assessment of existing TIA

approaches was conducted in order to identify potentials and shortcomings of

those methodologies for rural proofing. While some methodologies are not well

suited due to their methodological approach or geographic focus, three particular

methodologies were identified that can potentially contribute to rural proofing

exercises. The TIA Quick Check, territorial foresight as well as EATIA carry such

a potential, all of which apply different approaches regarding territorial

demarcation, use of quantitative data and expert involvement.

As none of those methodologies has yet been applied for rural proofing, three

cases demonstrating the practical application in hypothetical examples were

developed. The test runs do not only serve as practical examples, but also

contributed to identifying shortcomings in practical application. Based on those

test-runs a number of recommendations for further development of those tools

could be made. Inter alia, improvements are advised to specific tools, increasing

their geographical resolution and database flexibility as well as visualisations.

2

Furthermore particular guidance for application in rural proofing as well as

adapting templates provided to the specific application are recommended.

Apart from specific of methodologies, the wider implementation of rural proofing

in policymaking, including supporting measures has been assessed. The study has

shown, that rural proofing where it has been applied rarely succeeded if it

consisted only of a checklist approach or an individual methodology. Key factor

for successful implementation was the establishment of a responsible ministerial

department or other governmental body for rural proofing. Those bodies should

provide expert input to other departments on thematic and methodological issues,

act as a networking and exchange platform, and in general be involved in policy

drafting processes from early stages onward. A solid basis for rural proofing

within the legislative framework is also considered as a key success factor.

Therefore, a better link between the EU legislative process as laid down in the

Better Regulation Guidelines, the existing emphasis on Territorial Impact

Assessment and Rural Proofing will be necessary. For example, at EU level, tool

#34 should be expanded in order to address, how TIA can serve rural proofing

exercises, and how the methods currently included can be used in practice.

Another entry point for such an integration may be the preliminary impact

assessment stage, where the use of a territorial lens (including the rural one) may

serve as horizontal first assessment step to identify potential impacts of the

sectoral dimensions (economic, social, environmental etc.) in different types of

territories.

The study provides detailed recommendations on the above topics, aiming to

contribute to the development and mainstreaming of rural proofing and TIA at all

governance levels. Not only the EU level, but also national and regional levels are

addressed and specific guidance for them is provided. Ultimately, the study should

contribute to the debate on rural proofing raising awareness about the issue, but

also provides concrete recommendations for the successful implementation.

3

Introduction

This study is focussing on a term that has become in recent years a prominent

concept within rural development. Rural proofing has become a part of actions to

strengthening territorial impact assessments and is a declared approach of the

2022 Work Programme of the European Commission. Rural areas are considered

as particularly at-risk regarding disparities and unbalanced impacts of policies on

EU level and other levels of governance.

In 2016 the Cork Declaration first coined the term “rural proofing” in the context

of the CAP: “The rural potential to deliver innovative, inclusive and sustainable

solutions for current and future societal challenges such as economic prosperity,

food security, climate change, resource management, social inclusion, and

integration of migrants should be better recognised. A rural proofing mechanism

should ensure this is reflected in Union policies and strategies. Rural and

agricultural policies should build on the identity and dynamism of rural areas

through the implementation of integrated strategies and multi-sectorial

approaches.”

1

It has become obvious that since the CAP reform 1999 with the

introduction of Rural Development in the realm of Agricultural Policy that rural

areas are seen as specifically to be addressed regions in Europe. The assumption

was (and still is) that rural areas are differently affected by policies (as compared

to urban regions) due to the specific traits such as, for example, low population

density and net-population loss, lower income and economic potential, relatively

high dependence on single sectors (agriculture and related sectors) and low

connectivity and infrastructure endowments.

Rural proofing shall in this sense support to revitalise rural areas and close the

rural-urban gap by ensuring all relevant policies are aligned with rural needs and

realities. It is one of the transversal elements outlined in the Long-term Vision for

Rural Areas

2

. As the long-term vision, the rural proofing tool to be developed shall

contribute to implementing Art. 174 and 349 TFEU. As a part of the Better

Regulation Agenda, it should serve to assess the anticipated impact of major EU

legislative initiatives on rural areas. The vision also calls for Member States to

consider implementing the rural proofing principle at the national, regional and

local level.

Throughout the years there have been various definitions used and, in many cases,

there has been a mix of defining the term with policy changes to be captured by

the mechanism. In a most recent publication for the European Network for Rural

1

https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/cork-declaration_en.pdf

2

https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/new-push-european-democracy/long-term-vision-

rural-areas_en

4

Development (ENRD) the following definition has been used: “rural proofing is

a systematic process to review the likely impacts of policies, programmes and

initiatives on rural areas because of their particular circumstances or needs (e.g.

dispersed populations and poorer infrastructure networks). In short, it requires

policy-makers to ‘think rural’ when designing policy interventions in order to

prevent negative outcomes for rural areas and communities.”

3

This definition implies that rural proofing is to be regarded as a tool to assess

territorial impacts caused by any policy/intervention specifically filtering between

these effects in rural vs. any other areas. In other words, this definition leads the

way to the following components of the term:

• Territorial impacts: to be understood as a consequence of an external trigger

(exposure to a policy, shock, intervention) for a specific type of territory (rural

area – to be specifically defined and demarcated from any other area – e.g.,

urban). This definition follows a set of certain territorial characteristics, which

determine the reaction of the territory on the external trigger.

• Overall effect/impact: to be identified in contrast to any other territories. This

means that without comparison this contrast or difference of effect may not be

seen.

• Territorial unit: following suit the issue of demarcation of rural areas is then

the granulation on which the impact has to be captured. This implies that any

territory too large in size may not be suited to effectively show the different

effects of the policies. The phenomena of levelling out effects in too large an

area may occur.

This brings rural proofing very close to the methodological approaches used for

Territorial Impact Assessment. The Better Regulation Guidelines Toolbox

4

(Tool

#34) uses the two concepts synonymously: “Impact assessments and evaluations

should systematically consider territorial impacts when they are relevant and

there are indications that they will be significant for different territories of the

EU. Thanks to territorial impact assessments (TIA) and rural proofing

5

, the needs

and specificities of different EU territories can be better taken into account (for

3

Atterton J. (2022): Analytical overview of rural proofing approaches and lessons learned; ENRD Thematic

Group Rural proofing – Draft background document; Rural Policy Centre, SRUC (Scotland’s Rural

College)

4

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/br_toolbox_-_nov_2021_-_chapter_3.pdf

5

Commission Communication, The Future of Food and Farming, COM(2017) 713 and Commission

Communication: A Long Term Vision for Rural Areas, COM(2021) 345

5

instance of urban

6

/rural areas, cross-border areas

7

and the EU outermost

regions

8

) to facilitate cohesion across the Union.” It furthermore defines TIA in

the following way: “Territorial impact assessments are looking into all thematic

aspects of impact assessments (economic, social, and environmental) by

translating them into the territorial setting (regions)”. This strong conceptual link

between TIA and rural proofing is explored in the study. TIA methodologies

provide an important input for the methodological development of rural proofing.

For many years rural proofing has been rather applied on the Member State level

with more or less success and stringency (see examples from the ENRD Working

Group on Rural proofing

9

). The Cork Declaration and the following policy

discussion the Directorate for Agriculture (DG AGRI) has lifted the mechanism

up to the EU level. Quite logically – as the regional/local focus is clearly

embedded the Committee of the Regions (CoR) has also been following the

debate with interest. The study “Rural proofing – a foresight framework for

resilient rural communities” for which the present document is written aims at

identifying the mainstreaming potentials of existing rural proofing methodologies

and territorial impact assessment methodologies in the EU policy process. It

should contribute to a better understanding of rural proofing, its links with TIA,

its potentials and its limitations.

The study is based on desk research, expert interviews and case studies of rural

proofing applications. It is split in 5 parts:

• State of play of rural proofing in which past and recent developments in

the EU policy process related to rural proofing are outlined. Existing

methodologies from inside and outside of the EU are assessed regarding

their methodological approach and its advantages and disadvantages.

Experience in implementation (if available) is also presented.

• Existing TIA tools which assess methods for territorial impact assessment

currently applied. Their suitability for rural proofing is assessed and, if

applicable, which modifications to the methodology would have to be

made.

• The specificities of rural areas where the crucial challenges for rural areas

which are oftentimes considered the reason for a need for rural proofing are

6

Pact of Amsterdam: Urban Agenda for the EU (2016) and Council Conclusions on an Urban Agenda for the

EU (24.6.2016)

7

Commission Communication: Boosting growth and cohesion in EU border regions, COM(2017) 534

8

defined in Article 349 TFEU, which provides for the adoption of specific legislative measures for the EU

nine outermost regions across EU policies, taking into account their permanent constraints.

9

https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/enrd-thematic-work/long-term-rural-vision/TG-rural-proofing_en_en

6

outlined. The implications for policy planning and in particular rural

proofing tools are addressed as well.

• Application and improvement of existing methodologies in which

(virtual) case studies of applications of rural proofing are conducted. For

example, policies, three different methodologies are showcased and

potential outputs are presented.

• Guidance for better rural proofing finally synthesizes the results of parts

1 to 4 and provides recommendations for rural proofing at EU, national,

regional and local level as well as general recommendations for enhancing

the EU legislative process to include rural proofing.

7

1. State of play of Rural proofing

Rural proofing has been implemented in various forms in a number of countries,

with implementations ranging from voluntary application to mandatory part of the

policymaking process and from development of specific methodologies to

inclusion in broader impact assessments for policies. The term “Rural proofing”

and methodologies explicitly connected with it is particularly known in some

(former) commonwealth countries as well as in Scandinavia.

In the European Union, no such methodology has been adopted as standard,

though the European Commission underlines the need for it in several documents.

Notably the Cork 2.0 Declaration calls for an implementation of a rural proofing

mechanism in EU policymaking. Furthermore, the EC in the Staff Working

Document “A long-term Vision for the EU’s Rural Areas – Towards stronger,

connected, resilient and prosperous rural areas by 2040” states that a rural

proofing mechanism will be put in place for the EU policymaking process as part

of the Better Regulation Agenda (Atterton 2022; Bryce 2022; Expert interviews

2022; European Commission 2016; European Commission 2021).

1.1 Rural proofing in the Better Regulation Agenda

Following the call of the Cork Declaration and the long-term vision for rural areas,

the European Commission included particular considerations for rural areas into

the Better Regulation Agenda. While urban-rural disparities, challenges for rural

regions etc. have been mentioned in the Better Regulation Guidelines and

Toolbox before as well, the discussions seem to have influenced the recent

revision of the Toolbox in 2021. Notably, explicit reference to rural areas is

currently made in 11 individual tools:

• #18 Identification of Impacts

• #24 Competition

• #28 Digital-ready policymaking

• #30 Employment, working conditions, income distribution, social

protection and inclusion

• #31 Education and training, culture and youth

• #34 Territorial impacts

• #35 Developing countries

• #36 Environmental impacts

• #49 Format of the evaluation report

• #55 Horizontal matters

• #59 Cost estimates and the “one in, one out” approach

8

Furthermore, the term “rural proofing” is explicitly included in Tool #34

Territorial impacts, and assessment of effects concerning particularly rural

regions is stressed multiple times in this tool. While the Commission recommends

several particular methodologies for Territorial Impact Assessments (which can

partly include assessments of impacts on rural regions), no such recommendation

is made for rural proofing. The European Commission has announced in the past

however that the development of a tool for assessing impacts on rural areas is

currently ongoing (European Commission 2021, ENRD 2017)

1.2 Rural proofing methodologies

A number of approaches for rural proofing have already been applied, with

different methodologies and approaches, on different geographical levels and

against different policy backgrounds. Based on academic literature and in

particular based on inputs gathered from the recent ENRD meeting of the

Thematic Group on rural proofing, some of the most relevant methodologies have

been selected and are described below. For each method, a brief outline of the

approach, a grid-assessment based on the paper of characteristics of rural proofing

methods (Atterton 2022) as well as an overview of advantages and disadvantages

is provided.

1.2.1 Rural proofing (Finland)

Development and implementation of rural proofing in Finland started in the mid-

2000s based on international examples. While the importance of such assessments

was recognised by policymakers, it still was seen as an additional burden to the

law-making process and thus introduced only as voluntary action (Nordberg 2020,

4; Atterton 2022, 3). The core of the method is formed by a checklist produced by

the rural policy council located in the ministry of agriculture, however

implementation rests with the authority concerned with a specific policy.

Depending on the policy and implementation level, the checklist is completed

either by individual public officials, or in cooperative workshops engaging NGOs

or even the wider public. The process is supported by geospatial data analysis and

a questionnaire in some cases (Husberg 2022; Atterton 2022, 3).

9

Rural proofing

Mandatory?

Suggested application

Application is suggested/encouraged. The Rural Policy Council acts within their networks

and actively pushes/supports the relevant policymakers where necessary or requested.

Method for assessing the impacts

Stakeholder consultation/single person

assessment/checklist/data-based assessment

Depending on the implementation level, different methods are usually used. The core is

formed by a checklist, however methods for completion of the checklist differ. On national

level, mainly one or a few civil servants assess the potential effects based on their knowledge

and experience. On regional and local level, the process is usually more participatory bringing

in stakeholder workshops, questionnaires etc.

Involved institutions

Agricultural or rural ministry or authority/Non-

Agricultural or rural ministry or authority

The responsibility for implementing the procedure for a specific policy rests with the

authority in charge of that policy. The overall responsibility for rural proofing methodologies,

guidance and support lies with the Agricultural Ministry.

Level of application

National/regional/local level

The method has mainly been applied at regional and local level, and occasionally at national

level.

When in the policy process is it applied?

Early policy design phase/late policy design phase

The method is used ex-ante. It is advised to be used in the early policy design phase, however

as it is a voluntary procedure, in practice the responsible authorities can decide when/where

to use it.

Thematic focus

Rural areas (general)

A broad range of thematic fields are addressed in the checklist and assessment. Those fields

are supposed to cover all relevant topics for rural areas, no specific thematic focus can be

identified.

Source: Atterton (2022, 3), Husberg (2022), Nordberg (2020, 4f)

Main advantages of the method are its broad thematic orientation and adaptability

to regional and local circumstances. It can be tailored for different circumstances

and as such be applied to all kinds of legislation. It raises awareness of rural issues

in policymaking, and if applied in a participatory manner, it can act as an

“incubator” for regional and local actions by bringing different stakeholders

together (Husberg 2022; Nordberg 2020, .4f)

The main disadvantages are the slow uptake due to its voluntary nature and the

large amount of time and resources needed for a participatory process. As rural

proofing is one out of multiple available impact assessments, this reduces the

likeliness of it being applied even more (Husberg 2022; Nordberg 2020, .4f).

Overall, the method is strongly tied to other “checklist” approaches that have been

developed by different countries, and picks up multiple elements from them. It is

by design “open” to various assessment methodologies, and best used in a

participatory manner at lower geographic levels. This allows finetuning the

assessment to a wide variety of circumstances and topics, which is particularly

important for rural areas.

10

1.2.2 Regional Impact Assessment Statement (Australia)

The Regional Impact Assessment Statement (RIAS) was implemented in July

2003 by the State Government of South Australia and comprises an extensive

analysis of regional impact. It is required any time a significant decision may

impact services in regions. As the RIAS policy was introduced as a new approach,

agencies got assistance in deciding how best to implement it in their particular

circumstances. After a feedback process in different training and information

sessions, the guideline has been revised and re-published (DTED 2005, 2).

Title of the method

Regional Impact Assessment Statement (RIAS)

Mandatory?

Legislation backed mandatory

The RIAS process must be applied to any major government decision that will affect regional

services. This includes new policies, legislation or funding proposals, new or amended

regulatory provision, new or altered service delivery models, and program design and

evaluation.

Method for assessing the impacts

Checklist

A RIAS shall follow the template available on the website of the Department of Primary

Industries and Regions of the Government of South Australia (PIRSA). The template can be

understood more as a general guidance than a checklist, indicating the required text parts

and matters to be covered in the document.

Involved institutions

Rural ministry or authority

The Government of South Australia, Department of Primary Industries and Regions (PIRSA)

is committed to ensuring effective consultation and communication with regional South

Australian communities prior to the implementation of decisions with a significant impact on

regional communities. The RIAS Policy is part of that commitment. Regional South Australian

communities can download the RIAS template from the PIRSA homepage.

Level of application

Regional

The RIAS applies to all South Australian Government departments, agencies and statutory

bodies.

When in the policy process is it applied?

Early policy design phase/late policy design phase

A RIAS must be prepared prior to implementation of any decision that result in a significant

impact to one or more regional communities. This includes changes to existing or introducing

new services or initiatives.

Thematic focus

Specific topics

During the preparation of a RIAS economic factors, social and community factors,

environmental factors as well as equity factors shall be considered.

Source: PIRSA (2018; 2019a; 2019b; s.a.)

The main advantages of the Regional Impact Assessment Statements are the legal

framework, the precise definition of when a RIAS is to be carried out, and the

standardised guideline in the form of a template.

The main disadvantage of this method is the purely descriptive approach, which

does not allow for the same degree of objectivity as could be achieved, for

example, through quantitative evaluations. Furthermore, the guidance is rather

broad and leads to significant variation in implementation.

11

To conclude, the Regional Impact Assessment Statements are a good tool to get a

first overview whether a major government decision might affect regional

services, but cannot supplement a more detailed analysis. Since RIAS is a purely

descriptive method and no precise statistical analysis is required, the individual

assessments vary significantly in terms of depth and content. As a result,

individual RIAS are not comparable with each other – especially if they were

written by different persons or agencies.

1.2.3 Rural Lens (Canada)

In 1996, the “Rural Secretariat” was founded within the Department of

Agriculture and Agri-Food to bring together governments departments

concerning rural issues and priorities and to promote dialogue between rural

Canadians and the federal government. The Rural Lens in this context was

developed as a policy tool to review federal policies and programs through the

eyes of people living in distant and rural areas. The “Rural Secretariat” however

was discontinued in 2013 (Atterton 2019, 34ff). Nowadays, a new approach to

highlighting rural issues in the policymaking process has been implemented in the

context of Gender-based-analysis plus.

Title of the method

Rural Lens

Mandatory?

Legislation backed suggested

Despite its mandate, the Rural Lens had no authority to enforce horizontal coordination. After the

completion of the draft review, the Rural Lens Unit submitted a report back to the respective

government department. Considering the implementation of the comments, sponsoring

departments had no responsibility to report back to the Rural Lens Unit or the Rural Secretariat.

There was no legislation that required government departments to apply the Rural Lens and no

sanctions if it was not applied.

Method for assessing the impacts

Checklist

The Rural Lens tool was divided in 10 stages which were: Concept; Environmental Scan and

Impact Assessment; People and Organisations Involved; Development and Design;

Communications; Validation and Consultations; Refine Initiative and Identify Resources;

Approval; Deliver Program; Monitor and Evaluate Program. The guide described the stages on

the left side and included a template to fill in, questions to answer or examples to follow on the

right side.

Involved institutions

Agricultural or rural authority

The Rural Secretary prepared a guide for using the Rural Lens, which was published by

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

Level of application

National

The Rural Lens was designed to review federal programmes and policies from the perspectives of

remote and rural regions.

When in the policy process is it applied?

Early policy design phase/late policy design phase

Although, the Rural Lens was created as a policy tool to review federal programmes and policies

in the early development stages, it tended to be applied in the later policy development stages.

Thematic focus

Rural areas (general)/specific topic

In stage 2, environmental and general impacts on rural, remote and urban areas were

scanned and assessed. Further sub-columns for specific groups could be added.

Source: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (2001), Atterton (2019, 34ff).

12

Advantages: An early impact assessment could have helped to identify positive

and negative effects on rural areas. The guidance provided is rather

comprehensive gives a good overview on important questions to be considered.

Disadvantages: Since the Rural Lens tended to be applied in the later policy

development stages, it was often too late for the adaptation of the policy or

programme. The role and importance of the Rural Secretariat was somewhat

hidden and the success of the Rural Secretariat and the Rural Lens was mostly

“behind the scenes”. Furthermore, the Rural Secretariat had limited financial

resources and a small number of employees, which complicated long-time

planning. (Atterton 2019, 34ff)

Following the Rural Lens model, the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador

developed a Rural Lens tool and has published a guide for public bodies with the

aim of assessing regional policy implications. The Rural Lens was created to help

Cabinet decision-makers evaluate both positive and negative direct/intended,

indirect/unintended, and disproportionate or divergent implications of proposed

Cabinet decisions on rural individuals, stakeholders, and communities (PEP

2019, 3). In the past years, considerable additional efforts were made to integrate

rural considerations in the policymaking process, including mandating the

considerations through “gender-based analysis plus” in some topics and creating

a centre of expertise for rural proofing. The assessments place an emphasis on

rural economic development, however include broader rural issues as well. This

approach is considered successful in encouraging the communities to contribute

to rural development and supporting development from the inside.

1.2.4 Rural proofing (New Zealand)

In 2018, New Zealand made a formal commitment to rural proofing,

acknowledging the importance of rural communities to the country, as well as the

different structures, challenges, and drivers that exist in these communities,

implying that the impact and outcomes of new policies and programs may differ

from those in urban areas. Linked to this process, the New Zealand government

presented policymakers with recommendations for rural proofing. Along with the

recommendations, policymakers are provided a checklist, a paper detailing typical

concerns to examine, and a case study example (Atterton 2022, 4).

Title of the method

Rural proofing

Mandatory?

Suggested application

Rural proofing is a guidance tool for agencies rather than a mandatory assessment process.

Method for assessing the impacts

Checklist

The Ministry for Primary Industries published a rural proofing Guide for policy development

and service delivery planning with 7 points that should to be considered early and throughout

policy development and implementation to make rural proofing effective. Furthermore, the

13

rural proofing Impact Assessment Checklist is designed to help to consider potential impacts

on rural communities while developing a policy.

Involved institutions

Ministry

The Ministry for Primary Industries published the rural proofing Guide and the rural

proofing Impact Assessment Checklist. The implementation lies with the authorities

responsible for a specific policy.

Level of application

National/regional/local level

Since the rural proofing Guide and the rural proofing Impact Assessment Checklist are not

mandatory yet, the level of application is not specified.

When in the policy process is it applied?

Early policy design phase/late policy design phase

It is recommended to consider rural proofing early and throughout policy development and

implementation to be most effective.

Thematic focus

Specific topic

The rural proofing Guide focusses on infrastructure, health, education and other services,

ease of doing business/cost of compliance and communication.

The rural proofing Impact Assessment Checklist foresees to identify benefits and implications

for rural communities in the following areas: infrastructure, social, business, equity, and

other.

Source: MPI (2018a; 2018b), SWC (2018, 2)

The rural proofing Guide and the rural proofing Impact Assessment Checklist

have the advantage of providing an easy way to identify benefits and implications

for the rural communities. The guidance for its application is rather

comprehensive. The rural proofing Guide also indicates relevant rural contacts

and organisations to seek advice from.

The main disadvantages of this methods are its non-mandatory nature, the purely

descriptive approach to an impact assessment, as well as the explicit distinction

between “urban” and “rural” areas and comparing these regions with each other.

Overall, the method offers a first introduction to rural proofing. Despite the purely

descriptive approach, the comprehensive guidance ensures some consistency in

application. The government has established a core group on rural proofing as a

supporting measure, which monitors specific policy areas. Where relevant and

needed they take part in consultations, provide advice on rural issues and also

provide methodological support. Furthermore, they are available to authorities for

ad-hoc consultation on specific questions, ensuring a quick and unbureaucratic

process. This has been identified as one of the main success factors for rural

proofing in New Zealands policymaking.

1.2.5 Rural proofing (England)

Rural proofing in general has a long tradition in England being introduced in the

year 2000, with a formal requirement to publish annual reports on the matter.

Implementation however was lacking commitment from the responsible

14

authorities, and if conducted was done at a late stage without the possibility to

influence the policy process. The government department for rural affairs

provides guidance on assessing impacts on rural regions in the form of a checklist,

decision trees and examples for possible assessments (DEFRA 2017; DEFRA

2021; Atterton 2022)

Rural proofing (England)

Mandatory?

Mandatory application

While in principle rural proofing for policies is mandatory and dedicated personnel is defined

at each department, practical implementation seems to be lacking

Method for assessing the impacts

Checklist

Based on guidance provided by the department of rural affairs, a department responsible for

a specific policy has to assess the potential impacts, their strength and required policy actions

to address them. The method involves guiding questions and decision trees, with a descriptive

assessment of impacts.

Involved institutions

Ministry

The department responsible for a policy conducts the assessment.

Level of application

National/regional/local level

The level of application in principle is open, however guidance tends to be oriented towards

the national level. Further guidance on applying the method on the local level is provided by

other institutions and considered informal.

When in the policy process is it applied?

Early policy design phase/late policy design phase

As per the guidance the rural proofing exercise should be conducted in the early policy

design phase. Practical implementation shows however it is usually done at a later stage with

little potential influence.

Thematic focus

Rural areas (general)/specific topic (e.g.

environment, farming … )/Sub-element of TIA

The thematic focus is broad, explicitly addressing infrastructure and services, working and

living conditions, environment and equality

Source: DEFRA 2017; DEFRA 2021; Atterton 2022

The main advantage of the method is the formal commitment by the government

and the annual monitoring reports for implementation. Furthermore,

comprehensive guidance on the government level is published and regularly

updated to account for changing circumstances.

Main disadvantage is not linked to the method itself but to the practical

application. As responsible personnel was defined, the resources were available,

however, it seems the willingness to take up the issue in the policy design phase

was not high. There were no consequences if the assessment was not carried out

in an adequate manner, and furthermore confusion about responsibilities

contributed to the lacking quality (DEFRA 2017; DEFRA 2021; Atterton 2022).

15

2. Existing TIA tools

Territorially differentiated impacts of policies have been a topic in academic

research as well as in policymaking for a long time. Territorial Impact Assessment

(TIA) as a way of analysing such territorially differentiated impacts in a structured

manner as well as formulate suggestions for adapting policies based on the

outcomes of such analyses. By design, such TIA methodologies should be neutral,

i.e. not judging on the success of a policy but simply answering the question

“which regions or types of regions are impacted in which way by the policy”. In

some cases, such an imbalance in impacts can be undesirable and requires action

by policymakers to reduce them, while in other cases it might be acceptable or

even a desired effect (Fischer et. al. 2014, ESPON 2018).

The European Commission in the Better Regulation Toolbox, Tool #34

“Territorial Impacts” included a reference to rural proofing, however does not

consider it a TIA in itself. Nevertheless, a number of existing TIA methodologies

are in principle suitable for assessing impacts on rural areas, either by themselves

or in comparison with other regions. No TIA method developed so far can be used

as-is for rural proofing (in the sense as elaborated above – i.e. with its strong

normative character of policy shaping instead of policy assessing) without

additional considerations, however several methodologies can be easily adapted

or integrated into a rural proofing exercise (EC 2021, 297-303).

The Better Regulation Toolbox explicitly references three TIA methodologies

(TIA Quick Check, RHOMOLO and LUISA), all of which are assessed on their

suitability for rural proofing below. Furthermore, additional methodologies which

are the most commonly referenced ones in academic literature and at the same

time potentially suitable for rural proofing were included in the assessment,

namely EATIA, TARGET TIA and Territorial Foresight methodologies. There

are numerous other methodologies available, however many of them are either

outdated or not promising for rural proofing. The CoR has conducted research on

this topic already and provided a comprehensive overview of available

methodologies (CoR 2019) for further reference.

For the selected methodologies, a grid assessment outlining the general approach

and characteristics has been conducted below. The limited space available

naturally only allows for a quick overview, however weblinks are included for

further in-depth information for each method.

16

2.1 TIA Quick Check

The ESPON TIA Quick Check is an ex-ante territorial impact assessment method

with a hybrid approach based on the vulnerability concept. The combination of

territorial sensitivity (in the form of quantitative data) and exposure (expert

assessments in a workshop setting) leads to maps of potential territorial impacts

(impact patterns) for each region. It allows for a comparison of regional impacts

in the fields of economy, environment, society and governance, however

indicators used are broad and can be tailored to different effects (OIR, AIDICO

2013; OIR 2021). Furthermore, the assessment can be focused on different types

of regions, i.e., allows to address rural regions in particular (OIR 2021).

ESPON TIA Quick Check

General method

Hybrid

The method applies a combination of quantitative data (“sensitivity”) from statistical sources

and qualitative data in the form of expert judgement on the strength of effects (“exposure”)

collected in a workshop setting.

Processes/methods used

Territorial data analysis, Workshops, reporting

The core of the method is formed by an expert workshop, during which effects are identified

and maps on potential territorial impacts are generated with the webtool. The interpretation

of the maps takes place in the same workshop setting.

Territorial level

NUTS3

While the method in principle is capable to work on any territorial level, as long as

granulated statistical data is available, the Webtool available at the moment works on NUTS3

level. On this level, the balance between data availability on the European level and a

granulation fine enough to capture a regions characteristics is hit. The method is however

transferrable, e.g., to the national context, where different statistical data might be available.

Timing in the policy process

Ex-ante

The method is designed for an ex-ante assessment and should ideally be placed in the

inception impact assessment phase for EU policies.

Suitability for rural proofing

Could be used without modifications

While assessment of impacts on rural regions has been part of some TIA exercises, it has not

yet been used in a dedicated rural proofing setting. Comparative assessments are possible

without modification to the webtool at the moment. Some modifications could however

increase the suitability for rural proofing, e.g., improving the visibility of specific types of

regions on produced maps.

Source: OIR, AIDICO 2013; OIR 2021

The method allows for focusing the assessment on rural regions, thus in principle

is capable of contributing to rural proofing exercises. Within past assessments,

rural regions have been addressed in several instances, however, it has not yet

been used for a specific rule proofing application (CoR 2022). Based on the

underlying methodology, all assessments are comparative, i.e. either comparing

impacts on rural regions with urban regions, or comparing impacts on rural

regions amongst each other.

17

Main advantage is that the methodology is already recognised by the better

regulation toolbox as one of the territorial impact assessment methodologies for

the EU policy process. This ensures that knowledge about the method is already

available and would allow for easy adoption in rural proofing applications.

The method and tool are developed in projects commissioned by ESPON EGTC,

which provide trainings, webinars and application support

10

.

2.2 RHOMOLO

RHOMOLO

11

is a “Spatial Computable General Equilibrium Model” originally

developed by the JRC and DG REGIO for the assessment of cohesion policy on

regional level. It can be used for broader policy assessments in several fields, with

multiple modules expanding its capabilities beyond the assessment of purely

economic impacts. It is a well-tested and established methodology and recognised

by the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, making it well suited for impact assessments

of EU policies in the ordinary legislative procedure (COR 2019, 5f; Mercenier et.

al. 2016).

RHOMOLO

General method

Quantitative

The method relies on a tailored computable general equilibrium model for calculating regional

impacts on NUTS 2 level.

Processes/methods used

Quantitative assessment

The core of the method is built by the CGE which models interlinkages between regional

economies. A baseline scenario is produced, to which a policy is introduced as a “shock”

allowing for calculating impacts to regional economies. The method is highly specialised and

requires expert inputs.

Territorial level

NUTS2

The model includes all EU NUTS2 regions and one region which represents the rest of the world.

Timing in the policy process

Ex-ante and ex-post

The method allows for both ex-ante as well as ex-post assessments.

Suitability for rural proofing

Could be used with modifications

Main issue related to rural proofing is the territorial level, i.e. NUTS2 level. This does not allow

for sufficient distinction between rural and other regions. The method thus in principle is

transferrable and can be used, however relies on the collection and calculation of background

data on lower regional level.

Source: CoR 2019, 5f; Mercenier et. al. 2016

Since the results of RHOMOLO are calculated of NUTS2 level, the direct

application to rural proofing is limited. NUTS 2 does not allow for clear

distinction between rural- and other areas, as almost all NUTS 2 regions contain

10

https://www.espon.eu/tia-tool-2022

11

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/rhomolo

18

a multitude of different types of sub-regions, including both densely populated

urban areas as well as rural areas. The methodological approach would be

transferrable to lower geographical levels, however would require considerable

effort to calculate and construct the underlying matrices. Another approach

proposed by the developers is the combination of RHOMOLO and LUISA model

assessments as outlined below (Lavalle et. al. s.a.).

The model has been applied with success on higher geographical levels. Access

to the Rhomolo Webtool is possible for interested persons with registration.

However, application to concrete policies requires expert knowledge. The JRC

runs a dedicated webpage for the model

12

.

2.3 LUISA

LUISA

13

refers actually not to one single model, but is considered a “Territorial

Modelling Platform”. At its core, it is a cross-sectoral model for projecting “land

functions” in a grid-based approach modelling the change in land function for

each grid cell over time based on inputs form several external models/sources.

Based on those land function projections, a number of different modules can

provide results for a range of aspects (e.g. accessibility, employment…). LUISA

can also be applied in combination with RHOMOLO with outputs from one model

feeding into the other one (Lavalle s.a. 3ff; CoR 2019, 6f).

LUISA

General method

Quantitative

Core element is a grid-based land-function projection model. Results are obtained by

comparison of a calculated baseline scenario with calculated “policy scenarios”

Processes/methods used

Quantitative assessment

The assessment of the primary land-function projection calculates projections types of land

use in a 100x100m grid. Further modules are linked to those primary results, allowing to

calculate e.g. impacts on accessibility or employment

Territorial level

Free or flexible

The primary model is grid-based producing results on a 100x100m grid. Outputs regarding

further results can vary in territorial level, partially linked to the level of input data.

Timing in the policy process

Ex-ante

The model is primarily used on ex-ante assessments. It has been applied at several stages and

is not linked to a specific phase of the policy process.

Suitability for rural proofing

Could be used with modifications

The grid-based results allow for a clear differentiation and calculation of results for rural

areas. The modelling platform is in principle open and allows to tailor functionalities for

rural proofing, e.g. allowing to single out rural regions in the assessment, or aggregating

results for rural regions only.

Source: Lavalle s.a. 3ff; CoR 2019

12

https://rhomolo.jrc.ec.europa.eu/

13

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/luisa

19

The modelling platform is flexible and allows for the integration of modules,

tailoring to specific rural proofing application. The grid-based nature of land-use

projections is well suited for singling out impacts on rural regions in a policy

assessment. In particular in combination with RHOMOLO outputs (i.e. based on

the proposed RHOMOLO-LUISA linkage by the JRC) a sophisticated projection

of potential impacts on rural regions can be produced on a sufficiently detailed

regional level. Application to concrete policies requires expert knowledge, i.e. not

easy to integrate in a simple inception impact assessment or similar procedures

(Lavalle s.a., 5f).

LUISA has been applied with success and is one of the methodologies recognised

by the Better Regulation Toolbox. Access to the modelling platform is possible

for interested persons. The JRC runs a dedicated webpage for the platform

14

.

2.4 EATIA

EATIA (ESPON and Territorial Impact Assessment) is a methodology developed

in the framework of the ESPON programme. It is set up in a participatory manner,

aiming to involve relevant stakeholders and decision makers alongside of experts

in the assessment. At its core it consists of an “impact assessment matrix” which

is filled step-by-step by the assessors streamlining the expert knowledge gathered

through workshops and other consultation formats. The regions and types of

regions for which the assessment is made are defined in the process and are in

principle not bound to any administrative or statistical regions. The matrix finally

provides impact scores and directions of impacts for visualisation in maps and

other graphics (ESPON 2012).

EATIA

General method

Qualitative

The method is mainly based on expert consultation in different formats. Qualitative

assessments are made building on a structured process guided by an assessment grid. Results

are visualised and verbalised.

Processes/methods used

Stakeholder involvement/workshops

The methodology is highly participatory and involves stakeholders and external experts

through direct consultation as well as through structured workshops.

Territorial level

Free or flexible

The regions or types of regions which are affected in a specific manner as well as their

distinction is defined in the process. Due to the qualitative nature of the methodology it is not

limited to administrative boundaries or statistical regions.

Timing in the policy process

Ex-ante/ex-post

The method can be used for both ex-ante as well as ex-post assessments. The broader and

flexible nature of the qualitative assessments is suited particularly well for ex-ante

14

https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/luisa_en

20

assessments where little data is available.

Suitability for rural proofing

Could be used without modifications

Defining the assessed types of regions and distinguishing effects on different types of regions

form each other is at the core of the methodology. While principally it should be left open to

the involved experts to define the types of regions in one of the preparatory steps, it would be

possible to predefine “rural regions” for the assessment.

Source: ESPON 2012

Rural proofing methodologies in the UK were among the several methodologies

inspiring the EATIA method. In the cases where EATIA was trialled so far,

impacts on rural regions were assessed as one of different typologies, but were

not at the centre of assessments (ESPON 2012). As the method includes as one of

the first steps to define the types of regions for which the assessment is made, it

is however suited for rural proofing without further modifications.

The flexible nature of EATIA allows to tailor it to many different circumstances,

i.e. it can be used from the European level down to on sub-national level.

Furthermore, the assessment can address a broad range of topics or it can be

focused on a few topics of particular interest. Due to the qualitative nature, it is

particularly suited for thematic areas where other methodologies are limited due

to the lack of quantitative data available.

The original methodology however is somewhat limited in capturing smaller

differentiations as it only defines 2 positive and 2 negative impact classes.

Furthermore, if a broad range of topics are to be addressed, numerous

consultations are necessary in order to avoid basing assessments only on single-

expert-opinions.

The methodology is thus particularly valuable for broader assessments and for

cases were little or no quantitative data is available.

The method itself has not been applied outside of the ESPON project it was

developed for and trialled in. ESPON runs a website section for the project

15

.

2.5 TARGET TIA

TARGET TIA is not recognised by the Better Regulation Guidelines (BRG) as

one of the standard TIA methodologies, however it has been applied both as test-

run in an academic setting as well as in practice assessing impacts on cross-border

programmes. The method allows to assess the impacts along predefined

15

https://www.espon.eu/programme/projects/espon-2013/targeted-analyses/eatia-espon-and-territorial-impact-

assessment

21

dimensions (socioeconomic, environmental, sustainability,

governance/cooperation and polycentricity) and is based on the vulnerability

concept (for hybrid assessments) or purely on qualitative expert judgement (for

ex-ante assessments). Essentially, the method consists in the calculation of an

impact matrix (on a -4 to +4 scale) consisting of arithmetic average of impacts for

indicators under each dimension and finally calculating of an overall impact

(Medeiros 2014).

TARGET TIA

General method

Hybrid

Depending on the timing of the assessment, a purely qualitative approach (ex-ante) or a

combined qualitative and quantitative approach (ex-post) is used. In a multi-vector approach,

numerical impact values are calculated for four predefined territorial cohesion dimensions

Processes/methods used

Interviews/quantitative assessment

Depending on the timing and thus approach, either solely qualitative assessments based on

methodological knowledge and expert interviews are conducted, or a combined quantitative-

qualitative approach combining statistical data with expert interviews is followed.

Territorial level

Free or flexible

In principle the territorial level is free as for qualitative assessments the territorial units can

be defined in the process. However, when using quantitative data, the availability of data

determines the possible territorial level for the assessments.

Timing in the policy process

Ex-ante/ex-post

Both ex-ante as well as ex-post assessments are possible

Suitability for rural proofing

Could be used with modifications

For assessing impacts on individual regions as compared to others, the tool is suited well.

For larger-scale comparisons, the effort necessary for an assessment is considerably larger

than for other methodologies.

Source: Medeiros 2014

The TARGET TIA methodology can be used for assessing impacts on specific

regions, thus it can be used for rural regions in comparison with other regions.

However, assessments on a broader scale, i.e., multiple regions, can require a lot

of resources and might not be feasible. Furthermore, the fixed dimensions of the

original methodology are geared towards cohesion policy and might be too strict

and not the most relevant ones for a specific rural proofing exercise.

The flexibility of the method regarding data availability and territorial level is

valuable when targeting certain thematic fields which are not well-backed with

data. Furthermore, the broader scale of impacts as compared to other

methodologies is useful for distinguishing in more detailed ways between regions

and effect strength.

22

2.6 Territorial Foresight

The method of territorial foresight brings together qualitative and quantitative

analysis, combining foresight with elements of territorial impact assessment. The

method builds largely along participatory and co-creative approaches, in

combination with thorough desk research and mapping, for locating the territorial

implications. There are four key steps that guide territorial foresight (Böhme,

Lüer, & Holstein, 2020).

• Step 1: Defining the research “what if” question. At this stage is where the

link to the policy and the territory is made. The question should include the

future element, the territory in focus, the policy to be assessed for rural

proofing and the time horizon. In the case of rural proofing, the following

question could serve as example “What future outlooks would rural regions

have if policy A, is put into place by 2030?” Therefore, in the case of rural

proofing, the territory will be the rural areas, while the question will ask

how the respective policy to be assessed will impact rural areas in future.

• Step 2: Going through a thorough desk study and background research by

reviewing existing literature, material and resources to identify relevant

trends, factors, wild cards, challenges and their impacts, time span and

possible impacts on the territories, e.g., following the STEEP approach

(Social, Technological, Economic, Environmental, Political).

• Step 3: Running the participatory process, i.e., involving engaged experts

and stakeholders in a well-structured participatory processes, to spark

lateral, out-of-the-box thinking. Different approaches can be used, ranging

from workshops and focus groups, to surveys and interviews. The

participatory approach is also used for identifying and sketching

preliminary scenarios and territorial implications e.g., for rural areas in the

case of rural proofing. A key step in this process is to make a first

stakeholder mapping.

• Step 4: Post-processing of the material, i.e., developing a combined picture

of Steps 1-3 and bringing them together into a coherent story. At this stage,

the mapping of the identified territorial implications can be finalised.

Territorial foresight

General method

Hybrid

The method combines qualitative and quantitative approaches, drawing from literature, as

well as available data through desk research.

Processes/methods used

Desk research and participatory processes

The key starting point of the method is a thorough desk research of different sources, to run a

23

first trend collection, i.e., a collection of drivers, trends, challenges, wild cards that may

influence different territories to a different extend. The next core element of the process is the

participatory process, which benefits from the lateral thinking and expert knowledge of

different stakeholders. At this stage the impacts of the policy at hand on rural areas will be

discussed.

Territorial level

Free/flexible

The method for identifying and locating the territorial implications can work at different

levels. Depending on the availability of data, insofar that qualitative material can be used for

the development of maps. In the case of absence of quantitative material, the experts’

knowledge and qualitative sources are used instead. In the case of rural proofing, the rural

areas are in focus. The future impacts that a respective policy may have on rural areas will be

shown in the maps and scenario story.

Timing in the policy process

Ex-ante

The territorial foresight method is not used to predict the future. Instead it offers a flexible

tool for developing different possible futures and can be used for assessing what impacts a

policy may be used on different territories. Therefore it is designed for ex-ante practice.

Suitability for rural proofing

Could be used without modifications

The territorial foresight method has not been used so far for rural proofing. However, it could

potentially be a good method for exploring the impacts different policies may have in the

future, on rural areas. A focus on rural areas may be reflected in the mapping process of the

method.

Source: Böhme, Lüer, & Holstein, 2020

The territorial foresight method can be a possible method for rural proofing

exercises, although it has not been that specifically used before. An advantage of

the method is that in can deal with the high complexity and uncertainty of the

future and future trends by using lateral thinking and co-creation approaches.

Territorial foresight is a credible method for exploring futures and dealing with

this uncertainty for such a normative concept as the “future”. For rural proofing,

it can be used to check what impacts a policy may have on rural areas in future.

Furthermore, the territorial implications further add an interesting element of

“how” the different futures look like “where”.

The added value of foresight can be summarised to better anticipation, i.e. to

prepare better and sooner, better policy innovation, i.e. bringing new thinking in

policy making and running a future-proofing, i.e. a stress test of existing or prosed

strategies against different futures (OECD, 2019). To ensure a trustworthy

analysis, specific elements need to be considered during the process, such as

covering a variety of topics (e.g. by following the STEEP, Social, Technological,

Economic, Environmental and Political approach and specific topics within),

analysing possible cross-policy impacts and exploring possible biases, e.g. by

asking specific questions or exploring the matters from different angles (European

Parliament. EPRS. Panel for the Future of Science and Technology, 2021). This

helps in designing better and more sound policies for all types of territories.

24

The method has so far been used in a number of projects from ESPON for the

development of territorial scenarios, such as the ESPON Territorial Futures

(ESPON, 2018), the ESPON Territorial Scenarios for the Baltic Sea Region

(ESPON, 2019) and the ESPON Territorial Scenarios for the Danube and the

Adriatic Ionian macro-regions (ESPON EGTC, 2020).

Other methods may include a stronger focus on qualitative approaches, such as

modelling or trend extrapolation, horizon scanning methods, Delphi methods,

impact analyses and others. A more detailed description of these methods can be

found in the following indicative and non-exhaustive list of sources:

• European Commission. (2021). 2021 Strategic Foresight Report. The EU’s

capacity and freedom to act. Brussels: Secretariat General, European

Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/strategic-

planning/strategic-foresight/2021-strategic-foresight-

report_en#documents

• European Parliament. EPRS. Panel for the Future of Science and

Technology. (2021). Guidelines for foresight-based policy analysis.

• European Commission. (2020). Communication from the Commission to

the European Parliament and the Council – 2020 Strategic Foresight

Report. Charting the course towards a more resilient Europe. https://eur-

lex.europa.eu/legal-

content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0493&from=EN

• OECD. (2019). Strategic Foresight for Better Policies. Building Effective

Governance in the Face of Uncertain Futures.

• Rosling, H., Rosling, O. & Rönnlund, A. R. (2018). Factfulness: ten reasons

we’re wrong about the world – and why things are better than you think.

First edition. New York: Flatiron Books.

• European Commission DG Environment. (2017). Methodological

Framework for the systemic identification of emerging issues for the

environment.

• UNDP. (2014). Foresight: the Manual.

http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/capacity-

building/global-centre-for-public-service-excellence/foresightmanual.html

• Randers, J. (2012). 2052: a global forecast for the next forty years. White

River Junction, Vt.: Chelsea Green Pub.

• Loveridge, D. (2009). Foresight: The Art and Science of Anticipating the

Future. New York and London: Routledge.

• UNIDO. (2005). Technology Foresight Manual (Vol. 2).

25

3. The specificities of rural areas

The EU’s rural areas are home to 137 million people representing almost 30% of

its population and over 80% of its territory, considering all communes and

municipalities of Europe with low population size or density. While they have

always faced particular challenges, social and economic changes of the last

decades, including globalisation and urbanisation, are changing the role and

nature of rural areas (European Commission, 2021a). While potentially giving the

impression of a “gloomy future” for rural areas, the following section will focus

mainly on the challenges and topics relevant for such areas. These must not be

understood though as a purely negative outlook, as oftentimes challenges are also

linked to opportunities. E.g. remote regions might suffer from low accessibility or

broadband infrastructure, however at the same time the remoteness secures natural

capital which could not be maintained in other places. Rural proofing should not

only try to address the negative aspects (i.e. also contribute to fostering

development potentials and advantages of regions), nevertheless oftentimes the

challenges as compared to other regions are oftentimes the crucial aspect in policy

design (Shortall, Sherry 2019; ENRD 2017).

3.1 Trends and challenges in rural areas

Challenging trends in rural areas can be identified in numerous thematic fields.

Some of the main issues are population decline and ageing, erosion of rural

infrastructure and service provision, including access to healthcare, social

services and education as well as to postal and banking services. Rural areas are

also affected by shrinking employment opportunities, reduction in income or

limited transport services and lower digital connectivity (European Commission,

2021a).

Rural shrinkage and demographic change

The demographic change in rural areas is characterised by two trends: the overall

loss of population (“shrinking”) and the increase of the share of older people and

the decrease of younger people (“aging”).

In 2020, already 34% of the EU population lived in a shrinking region. Rapid

reductions in population are more likely to occur in rural regions than in urban

ones (11% as against 1%). Projections show that in the future, more regions will

be shrinking. In 2040, already 51% of the EU population will live in shrinking

regions. (European Commission, 2022)

26

Figure 1: Population by type of demographic change by urban-rural typology, 2010-

2040

Source: European Commission (2022)

Across Europe almost 60% of Predominantly Rural or Intermediate NUTS 3

regions meet criteria of sustained (past or projected future) demographic decline.

These regions cover almost 40% of the area of the EU and contain almost one

third of its population. These regions are mostly in the East and South of Europe,

with scattered regions in the North and West, in particular in Germany and

Sweden (ESPON ESCAPE, 2020).

The EU’s population in general is ageing, however the population in rural areas

is already older, on average, than the population in towns and suburbs and cities.

Rural regions have, on average, seen a reduction in population in recent years

mainly due to negative natural population change, not compensated by sufficient

positive net migration. Certain eastern and southern Member States are even

confronted with both challenges, as natural population change and net movement

in their rural regions have been negative. Moreover, young women are more likely

to leave rural regions than young men. These demographic trends, when coupled

with a lack of connectivity, infrastructure and productivity challenges and low

access to public services including education and care, can contribute to the lower

attractiveness of rural areas as places to live and work in particular for younger

people (European Commission, 2021a).

27

Figure 2: Shrinking and growing regions in the European Union

Source: ESPON ESCAPE

Especially rural regions will have to adjust to a growing population aged 65 and

over, and a shrinking working age and younger population with severe

consequences (European Commission, 2022):

• The shrinking of the working-age population (aged 20-64) weakens growth

potential and skills development, while favouring the concentration of

economic activities in fewer locations. This could lead to labour market

shortages.

• The increase in the population aged 65 and over is likely to lead to an

increase in the demand for healthcare, which will have to adapt their

infrastructure and services to make them more accessible to people with

limited mobility, and increase the capacity of healthcare services.

• Large reductions in the number of young people are likely to lead to a

reduction in the number of schools, which may lead to longer distances to

the closest school.

As a result of demographic change, there will be more older patients suffering

from chronic diseases. Almost half of persons 65 years or older are perceived as

28

having a disability or long-standing activity limitation. In addition, the effects of

climate change, natural disasters and environmental degradation and pollution

tend to disproportionately increase pressure on older people’s health. This will

increase the need for healthcare and other care or support services.

16

Economic parameters

While higher growth has enabled the gap to narrow since 2000, gross domestic

product (GDP) per capita in rural regions was still considerably lower (at 75%)

than the EU average in 2018. The economic catching-up did furthermore not reach

remote rural regions (which remain at around 70% of EU GDP per capita).

The average employment rate in the EU’s rural areas increased between 2012 and

2020 (from 67.5% to 73.1%, i.e. higher than in cities), while the average

unemployment rate dropped (from 10.4% to 5.9%, i.e. lower than in cities).

Young people have a higher unemployment rate compared to the general working

age population, also in rural areas.

In terms of share of population that is at risk of poverty or social exclusion, the

figures in 2019 are higher in rural areas (22.4%), compared to cities (21.3%) and

towns and suburbs (19.2%), and in ten Member States the percentage of the

population at-risk-of-poverty in rural areas has increased since 2012 (European

Commission, 2021a).

There is a gap between male and female employment in rural areas of 13

percentage points (versus 10 percentage points in cities), rising to over 20 in

certain Member States. This gap has remained fairly stable at EU level since 2012.

In over half of the Member States, this gender employment gap is wider in rural

areas than cities. Many women have precarious contracts (e.g. seasonal workers)

or play an “invisible role” in rural societies (e.g. assisting spouses), which may

leave them exposed to vulnerable situations (such as no access to social protection