AIR QUALITY IN

LEWISHAM: A GUIDE

FOR

PUBLIC HEALTH

PROFESSIONALS

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

COPYRIGHT

Greater London Authority

February 2022

Published by

Greater London Authority

City Hall

Kamal Chunchie Way

E16 1ZE

www.london.gov.uk

enquiries 020 7983 4000

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

1

PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT

Public health professionals in local authorities have a critical role to play in driving

systemic progress on air pollution. There is now an urgent need for ambitious local action

to protect both human and planetary health. In the context of the pandemic and the

escalating climate emergency, it is crucial that London’s recovery is socially just and

green. This will help to tackle these threats and prevent thousands of premature deaths

caused by air pollution.

We published our last borough-specific guidance documents for local authority public

health professionals in 2012. It is fair to say that a lot has changed since then.

Air pollution is a major cause of premature death and disease; and is the largest

environmental risk to public health in the UK. The Greater London Authority (GLA)

estimated that in 2019 there were between 3,600 and 4,100 premature deaths

attributable to air pollution

1

. Both short and long-term exposure to air pollution can lead

to a wide range of harmful effects which come about at every stage of life, from a foetus’

first weeks in the womb all the way through to old age. The main pollutants of concern

within London are nitrogen dioxide (NO

2

) and particulate matter (PM). Currently, there is

no clear evidence of a safe level of exposure below which there is no risk of adverse

health effects. Therefore, reductions in concentrations of NO

2

and PM below air quality

standards is likely to bring additional health benefits.

Air pollution affects everyone who lives and works in London. However, some –

especially, children, the elderly, and people with pre-existing health conditions – are

most vulnerable. People on low incomes or from ethnic minorities are also more affected

by poor air quality, partly because they often live in the more polluted areas of London.

Children in London are almost four times more likely than children elsewhere in England

to attend a school in a highly polluted area. In December 2020, a landmark ruling by a

London Coroner concluded that Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah died, aged nine in 2013, from a

combination of acute respiratory failure, severe asthma and air pollution exposure. It is

the first time in the UK that air pollution has been listed as a medical cause on a death

certificate. The Coroner’s Prevention of Future Deaths report also highlighted a lack of

public and professional awareness about the risks of air pollution.

Considering this it is more vital than ever for borough public health teams to work with

other relevant local authority teams on air quality as air pollution does not respect

borders. We recommend Joint Strategic Needs Assessments are regularly updated to

include the latest information shown in this document. They should also take account of

the recommendations set out in the Coroner’s Prevention of Future Deaths report.

Collaborative action is needed across sectors and systems to reduce air pollution, risks

1

http://erg.ic.ac.uk/research/home/resources/ERG_ImperialCollegeLondon_HIA_AQ_LDN_11012021.pdf

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

2

and health inequalities; and to ensure air pollution is considered in every relevant policy

at the local level. We must tackle different pollutants together and maximise societal

gains. There are a wide range of co-benefits to improving air quality. This is not just in

terms of improving health and reducing health inequalities; it will also help boost the

economy, environment and climate change adaptation and mitigation.

In 2012, we provided local authorities with borough-specific guidance documents to

support public health professionals who may not have previously worked in air quality.

Our aim was to provide all the information needed to quickly get to grips with the issue

of air quality. This updated document reflects the latest scientific evidence on both the

impacts of, and solutions to, air pollution. This will enable effective local responses

through setting out knowledge, recommendations, or approaches for action. It has been

tailored to support and enhance collaboration and public health leadership to address air

pollution. It presents the latest air quality and health data and analysis for London’s 32

boroughs and the City of London in 33 bespoke reports.

We hope you will find this report useful for:

- assessing and framing air pollution risks in a health and environmental context and

ensuring air pollution is prioritised appropriately

- extracting data and evidence that you can use in your Joint Strategic Needs

Assessment on air quality, Health and Wellbeing Strategy and Air Quality Action Plan,

including raising awareness of the health and economic costs of air pollution

- discussions with local authority colleagues around how to tackle the health impacts of

air quality ensuring a joined-up approach at local and at system level, including in the

context of action on climate change

- raising awareness of the contribution that action on air quality has to a range of

public health outcome measures

- reaching out to colleagues in healthcare organisations, such as doctors, nurses and

pharmacists around opportunities to strengthen their education, training and

awareness in relation to air quality

- spreading best practice to GPs and sensitive receptors

Authors

This document was prepared by the Greater London Authority in partnership with the UK

Health Security Agency (UKHSA). It includes input from the London Association of

Directors of Public Health, London Councils, and public health specialists from the London

boroughs of Croydon and Lewisham. It also includes input from environmental specialists

in the London boroughs of Merton, Richmond upon Thames, Wandsworth, Kingston and

Sutton.

To find out more, please contact: [email protected]

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

3

Contents

PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT ................................................................................................................................... 1

1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 6

1.1 Air pollution in London: Facts and figures ................................................................................................................ 6

1.2 The case for tackling London’s air pollution crisis .................................................................................................... 7

1.3 Green Recovery from COVID-19 ............................................................................................................................... 7

2 AIR POLLUTION AND ITS HEALTH IMPACTS .............................................................................................................. 9

2.1 What is air pollution? ............................................................................................................................................... 9

2.2 Main sources of air pollution in London ................................................................................................................... 9

2.3 Main pollutant types of concern in London .............................................................................................................. 9

2.4 Health effects of air pollution and associated health inequalities ......................................................................... 10

2.5 Indoor air pollution ................................................................................................................................................ 14

2.6 Public Health Outcomes Framework ...................................................................................................................... 14

2.7 The Cost of Air Pollution ......................................................................................................................................... 15

3 POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORKS FOR IMPROVING AIR QUALITY .........................................................................16

3.1 World Health Organisation (WHO) ........................................................................................................................ 16

3.2 EU Directive ............................................................................................................................................................ 16

3.3 UK Air Quality Policy............................................................................................................................................... 16

The Air Quality Standards Regulations 2010 ........................................................................................................... 16

Clean Air Strategy, 2019 .......................................................................................................................................... 17

Environment Act, 2021............................................................................................................................................ 18

3.4 Local authority responsibilities ............................................................................................................................... 18

4. AIR QUALITY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT OF COMPLIANCE...........................................................................20

4.1 Air Quality Monitoring in London ........................................................................................................................... 20

4.2 Communicating levels of air pollution .................................................................................................................... 20

4.3 Actions already taken to clean up London’s air ..................................................................................................... 22

4.4 Impact of COVID-19 on air quality in London ......................................................................................................... 27

5 AIR QUALITY AND ITS HEALTH IMPACTS IN LB LEWISHAM ......................................................................................28

5.1 Location and monitoring ........................................................................................................................................ 28

5.2 Annual mean concentrations ................................................................................................................................. 28

5.3 Air quality focus areas ............................................................................................................................................ 29

5.4 Health Impacts in LB Lewisham ............................................................................................................................. 30

6 WHY FURTHER ACTION IS NEEDED ..........................................................................................................................32

6.1 Maximising the health benefits from improving air quality ................................................................................... 32

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

4

6.2 Communicating with patients and the public ........................................................................................................ 33

6.3 Actions boroughs can take to improve air quality ................................................................................................. 34

7 NEXT STEPS .............................................................................................................................................................36

8 APPENDICES ............................................................................................................................................................38

Appendix 1 National Air Quality objectives and European Directive limit and target values ...................................... 38

Appendix 2 Fraction (%) of mortality attributable to long term exposure to PM

2.5

(2019) .......................................... 40

Appendix 3 Public Health Outcomes Framework indicators that could be influenced by policies to improve air quality

..................................................................................................................................................................................... 41

Appendix 4 Relevant London Strategies ....................................................................................................................... 43

Appendix 5 PM monitoring in LB Lewisham ................................................................................................................. 45

Appendix 6 Population exposure .................................................................................................................................. 46

Appendix 7 Imperial College London study data sources and methodology ................................................................ 52

Appendix 8 Local Authority population, total deaths from all causes, range of mortality burden (deaths) for PM

2.5

and NO

2

and mean fraction of mortality attributable to PM

2.5

and NO

2

in 2019. ........................................................ 53

Appendix 9 Actions for Londoners to mitigate against air pollution ............................................................................ 55

Appendix 10 LEDNET/ ADPH Recommendations for action to clean up London’s air .................................................. 57

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

5

Figure 1 Types of particulate matter (UFP, PM

2.5

, PM

10

). Of these, UFP and PM

2.5

are the most

harmful types for health. Image source VFA ..................................................................................... 10

Figure 2 Impact of Air Pollution on Health throughout a lifetime. Taken from PHE Health Matters

2018.................................................................................................................................................... 10

Figure 3 Health effects of air pollution, taken from PHE Health Matters, 2018. .............................. 11

Figure 4 Air pollution affects everyone but there are inequalities in exposure and the greatest

impact on the most vulnerable. Taken from PHE Health Matters 2018 ........................................... 13

Figure 5 Trend in NO

2

in London vs no ULEZ scenario ....................................................................... 22

Figure 6 Changes in hourly average NO

2

(weekdays, central London) .............................................. 27

Figure 7 LB Lewisham Focus Areas, London Atmospheric Emissions Inventory (LAEI 2016) ............ 29

Figure 8 Mean fraction of mortality attributable to PM

2.5

and NO

2

in each London borough .......... 30

Figure 9 Illustrated Air Pollution Hierarchy, taken from PHE’s 2019 evidence review. .................... 32

Figure 10 Why travel makes a difference. Taken from PHE Health Matters 2018 ............................ 33

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

6

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Air pollution in London: Facts and figures

• In London alone, air pollution leads to thousands of premature deaths and costs the city’s

economy an estimated £3.7bn every year

2

.

• NO

2

and PM

2.5

, the two pollutants of greatest concern in London, are linked to a variety of

adverse health impacts.

• Air pollution affects everyone who lives, works, or visits London but it disproportionally

affects the poorest and most vulnerable communities, including children.

• In 2019, in areas where the least affluent Londoners live, the annual average concentration

of NO

2

was 3.8 µg/m

3

more than the most affluent areas. That is 13 per cent higher. For

PM

2.5

, the most deprived areas had an annual average concentration 0.7 µg/m

3

, six per cent

higher than the least deprived areas.

• There is currently no safe level for PM

2.5

or NO

2

. In recognition of this, the World Health

Organisation (WHO) recently lowered its guideline limits for PM

2.5

to 5 µg/m

3

and NO

2

to

10 µg/m

3

. The aim is to achieve the lowest concentrations

possible

3

.

• There have been improvements in air quality across London in recent years, especially for

NO

2

. In 2019, 84 per cent of major roads in London met the legal limit for NO

2

4

, compared

to 46 per cent in 2016 and just 37 per cent in 2013. Despite the dramatic progress to date,

air pollution remains the biggest environmental risk to health.

• London has already taken bold action with the introduction of the central London Ultra Low

Emission Zone (ULEZ) in 2018. This has reduced concentrations of NO

2

at roadside sites in

the central zone by 44 per cent. The ULEZ was further expanded in 2021.

• Since 1 March 2021, most heavy vehicles have had to meet Euro VI emission standards of

the London-wide Low Emission Zone (LEZ). This includes lorries, buses, and coaches. These

standards are the same as the ULEZ, so there is only one charge for heavy vehicles in London.

• The ULEZ expansion will reduce road transport emissions of nitrogen oxides (NO

x

) by 30 per

cent. This will mean an expected 92 per cent of roads in London would comply with legal

limits for NO

2

by the end of 2021. Combined with other measures, this puts us on track for

legal compliance by 2025 at the latest. Reducing NO

2

or PM concentrations below air quality

standards is likely to bring additional health benefits.

• More action is needed locally and nationally as most areas of London are exceeding WHO

guideline limits for PM

2.5

.

2

https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/asthma_kings_report_april_2019_final.pdf

3

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228

4

https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/london-atmospheric-emissions-inventory--laei--2019

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

7

1.2 The case for tackling London’s air pollution crisis

There are a wide range of co-benefits to improving air quality. This is not just in terms of

improving health and reducing health inequalities. It is also good for the economy, environment,

and climate change adaptation and mitigation.

Air pollution affects everyone who lives and works in London; and London has some of the poorest

air quality in England. The Mayor’s vision is for London to have the best air quality of any major

world city. His ambition is to go beyond the legal requirements to protect human health and

minimise inequalities. The pandemic has highlighted stark health inequalities across the city. A

report by Imperial College London offered a comprehensive overview of the most credible

evidence for the links between air pollution and COVID-19. It found that there are a small number

of studies supporting a relationship between long-term exposure to air pollution and higher risk of

Covid-19 or its adverse consequences

5

. The report also highlighted air pollution’s role in increasing

vulnerability to, and severity of, a range of acute lower and upper respiratory infections.

1.3 Green Recovery from COVID-19

London is vulnerable to many of the impacts of the climate crisis, including worsening flooding and

heatwaves. That is why the Mayor has been clear that London’s recovery from the COVID-19

pandemic must be a green one.

The city’s recovery is led by the London Recovery Board, chaired jointly by the Mayor and Chair of

London Councils. It brings together leaders from across London’s government, business and civil

society, the health and education sectors, trade unions and the police. The aim is to oversee the

long-term recovery effort. The board, which includes the NHS, has committed to taking a missions-

based approach for both economic and social recovery.

One of the nine missions, the Green New Deal Mission, aims to tackle the climate and ecological

emergencies and improve air quality. It will do this by doubling the size of London's green

economy by 2030 to accelerate job creation for all. The Green New Deal Mission focuses on three

key themes:

1) Decarbonising and transforming the built environment;

2) Greening London’s transport and public realm; and

3) Mobilising new finance and support green jobs, skills and lifestyles.

Theme two has the potential to improve air quality. Project areas focus on supporting modal shift,

electrifying London’s vehicle fleet and infrastructure and developing zero emission zones.

Prioritising sustainability, climate mitigation, and resilience is also a cross-cutting principle

underpinning work across all the recovery missions.

5

https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/environmental-research-

group/ReportfinalAPCOVID19_v10.pdf

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

8

The first national lockdown in the pandemic (from March to June 2020) led to behavioural changes

by Londoners which temporarily helped improve air quality. These included a reduction in

personal vehicle use, road traffic, and an increase in active travel whilst socially distancing. Cleaner

air and reduced traffic noise were widely noted and valued during this period. However, levels of

road traffic and air pollution have been increasing since then. We now need coordinated action to

ensure that these gains are not lost.

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

9

2 AIR POLLUTION AND ITS HEALTH IMPACTS

2.1 What is air pollution?

Air pollution is the largest environmental risk to public health in the UK

6

. Both indoor and outdoor

air pollution can harm health. An air pollutant is anything in the air that could harm people’s

health, including small particles, liquid droplets and gases. Air pollutants are emitted from a range

of man-made and natural sources; and can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary

pollutants are emitted directly from a source whilst secondary pollutants form when other

pollutants (primary pollutants) react in the atmosphere.

2.2 Main sources of air pollution in London

Most of the air pollution in London is produced by traffic, heating, and burning of solid fuels. Over

40% per cent of the NO

2

in London comes from road transport (LAEI, 2019). This is why the highest

concentrations of NO

2

are recorded at busy roadside locations.

Around a third of the PM

2.5

emitted in London comes from road transport. A large proportion

(40%) also comes from construction, wood burning, and commercial cooking (LAEI, 2019).

Alongside emissions from local and regional sources, levels of PM are also influenced by emissions

from mainland Europe and further afield. The sources of larger PM

10

particles are broadly similar,

and road transport accounts for around a quarter of PM

10

in London. The 2019 London

Atmospheric Emissions Inventory (LAEI) was published in December 2021 and provides an update

to the previous LAEI2016 and a new baseline for 2019. Data from the LAEI is publicly available on

the London Data Store and includes concentration maps, population exposure data and emissions

by pollutant and source split by London Zone and by borough. Officers are encouraged to review

the 2019 inventory and specific data sets for their boroughs.

2.3 Main pollutant types of concern in London

The UK Air Quality Standards Regulations (2010) sets standards for a variety of pollutants

considered harmful to human health and the environment. These are detailed in Appendix 1. The

pollutants of most concern in London are NO

2

, PM

2.5

and ozone (O

3

). NO

2

is a toxic gas produced

during combustion processes, such as in the engine of a car. Some PM

2.5

occurs naturally, such as

dust and sea salt, and some is man-made, such as particulates from vehicle exhausts and burning

solid fuels. O

3

is a secondary man-made pollutant formed when air pollution from internal

combustion engines (NOx) and power plants (Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)) combines

chemically with oxygen. PM (see figure 1) and the gases NO

2

and O

3

are particularly damaging

pollutants for human health

7

. PM

2.5

is the air pollutant thought to have the greatest impact on

human health. There is no recognised safe level for health

2

.

6

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/air-pollution-applying-all-our-health/air-pollution-applying-all-our-

health

7

https://www.blf.org.uk/support-for-you/air-pollution/what-is-it

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

10

2.4 Health effects of air pollution and associated health inequalities

The health effects of air pollution are complex, and range in severity. Air pollution can harm health

at every stage of life from the first weeks in the womb all the way through to old age (figure 2).

In some cases, the damage can be gradual and may not become apparent for many years.

However, it can also have short-term impacts which may exacerbate symptoms, increase hospital

Figure 2 Impact of Air Pollution on Health throughout a lifetime. Taken from PHE

Health Matters 2018

Figure 1 Types of particulate matter (UFP, PM

2.5

, PM

10

). Of these, UFP and PM

2.5

are the most

harmful types for health. Image source VFA

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

11

admissions and even death

8

(figure 3). Long-term exposure (over years or lifetime) reduces the

number of years we spend in good health (healthy life expectancy). There is no level of exposure

which doesn’t impact on health. As such, reducing NO

2

or PM concentrations below air quality

standards is likely to bring additional health benefits. This is reflected in the recently updated

WHO air quality guidelines, which are significantly tighter than their previous guidelines

9

.

Table 1 below summarises some of the main health impacts of NO

2

, PM

2.5

and PM

10.

Table 1 Overview of health impacts for key pollutants of concern.

8

Health matters: air pollution - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

9

WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines (2021) https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/who-global-air-quality-

guidelines

10

A mixture of particles and/or liquid droplets in the air that have a diameter less than 2.5 micrometres across (one

400

th

of a millimetre).

11

A mixture of particles and/or liquid droplets in the air that have a diameter less than 10 micrometres across.

Pollutant

Key health impacts

NO

2

Effects on lung development (lung function growth), respiratory

infections in early childhood and effects on lung function in adulthood.

PM

2.5

10

Based on current evidence, PM

2.5

is thought to be the air pollutant which

has the greatest impact on human health. Both short and long-term

exposure to PM

2.5

increases mortality risk from lung and heart diseases

and stroke as well as increasing hospital admissions.

PM

10

11

Like PM

2.5

(which is a subcomponent of PM

10

), PM

10

harms the

respiratory and cardiovascular systems, and increases the chance of

premature death.

Figure 3 Health effects of air pollution, taken from PHE Health Matters, 2018.

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

12

When air pollutants enter the body, they can affect various organs and systems

12

. This includes:

• The eyes, nose and throat

• The lungs and respiratory system, including worsening asthma and chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease and as a cause of lung cancer

• The heart – heart and blood vessel diseases, including strokes and hardening of the arteries

(atherosclerosis), are some of the main health effects of air pollution.

There are several methods for measuring the impact of air pollution upon health. The Committee

on the Medical Effects of Air Pollution (COMEAP) has released a comprehensive document

13

collating its recommendations for quantifying air pollutants’ health impacts.

Long-term exposure to air pollution reduces life expectancy by increasing the incidence of lung,

heart and circulatory conditions

14

. Long-term exposure to air pollution in early life can have a

lasting effect on lung function, including suppressing children’s lung function growth

15

. Maximising

development of lung function in childhood is important as low lung function leads to less reserve if

lung disease develops. This is associated with higher health risks if lung disease develops later in

life.

Asthma, a long-term inflammatory condition of the conducting airways of the lungs, leads to

coughing, wheezing, chest tightness and shortness of breath. Asthma symptoms in those who

have the condition can be exacerbated by various stressors. These include respiratory viral

infection, allergen exposure, and episodes of elevated air pollution

16

.

There is increasing evidence of air pollution having a potential role in causing asthma, especially in

people who live near busy roads

17

. In addition, short-term peaks in pollution levels are a trigger

that can make asthma symptoms worse, increasing the risk of exacerbations

18

. This is also true for

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

19

. Quality and Outcomes Framework data from GP

12

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-air-pollution/health-matters-air-pollution

13

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/927754/Summa

ry_of_COMEAP_recommendations_for_quantification.pdf

14

Jos Lelieveld, Andrea Pozzer, Ulrich Pöschl, Mohammed Fnais, Andy Haines, Thomas Münzel, Loss of life expectancy

from air pollution compared to other risk factors: a worldwide perspective, Cardiovascular Research, Volume 116,

Issue 11, 1 September 2020, Pages 1910–1917,

15

Schultz ES, Litonjua AA, Melén E. Effects of long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution on lung function in

children. Current allergy and asthma reports. 2017 Jun;17(6):1-3.

16

https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/asthma

17

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-air-pollution/health-matters-air-pollution

18

Orellano P, Quaranta N, Reynoso J, Balbi B, Vasquez J. Effect of outdoor air pollution on asthma exacerbations in

children and adults: systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. PloS one. 2017 Mar 20;12(3):e0174050.

19

Song Q, Christiani DC, Ren J. The global contribution of outdoor air pollution to the incidence, prevalence, mortality

and hospital admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

International journal of environmental research and public health. 2014 Nov;11(11):11822-32.

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

13

registers shows approximately 508,000 people with asthma and 117,000 people with COPD live in

London (2019-20 data)

20

.

Emerging evidence suggests air pollution may affect the brain and is possibly linked to dementia

and cognitive decline

21

and mental health impacts

22

. There is also evidence associating air

pollution with impacts in pregnancy and early childhood, such as low birth weight

23

.

As shown in figure 4, some groups are particularly susceptible to the harms of air pollution. These

include older people, children, pregnant women and those with existing cardiovascular or lung

disease

24

. People who live / work in highly polluted areas, near busy roads, or who spend long

periods in traffic, are also at increased risk. This is because congestion is strongly associated with

air pollution, and car occupants are typically exposed to more air pollution than cyclists or

pedestrians

25

.

20

https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMDZiMmI2MzEtMWVjZC00YTVlLWI5NjEtMTNkODM3M2M0NDk3IiwidCI6IjU

wZjYwNzFmLWJiZmUtNDAxYS04ODAzLTY3Mzc0OGU2MjllMiIsImMiOjh9

21

Power MC, Adar SD, Yanosky JD, Weuve J. Exposure to air pollution as a potential contributor to cognitive function,

cognitive decline, brain imaging, and dementia: a systematic review of epidemiologic research. Neurotoxicology. 2016

Sep 1;56:235-53.

22

Braithwaite I, Zhang S, Kirkbride JB, Osborn DP, Hayes JF. Air pollution (particulate matter) exposure and

associations with depression, anxiety, bipolar, psychosis and suicide risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Environmental health perspectives. 2019 Dec 18;127(12):126002.

23

Stieb DM, Chen L, Eshoul M, Judek S. Ambient air pollution, birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Environmental research. 2012 Aug 1;117:100-11.

24

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-air-pollution/health-matters-air-pollution

25

http://content.tfl.gov.uk/technical-note-20-what-are-the-main-health-impacts.pdf

Figure 4 Air pollution affects everyone but there are inequalities in exposure and

the greatest impact on the most vulnerable. Taken from PHE Health Matters 2018

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

14

Ethnic minorities and deprived communities are hardest hit by air pollution in London

26

. In 2019,

areas where the most deprived Londoners lived, had a higher annual average concentration of

NO

2

by 3.8 µg/m

3

than the least deprived areas. For PM

2.5

, areas where the most deprived

Londoners live had an annual average concentration 0.7 µg/m

3

higher than the least deprived

areas

27

. The Mayor is now taking measures to tackle London’s air pollution. By 2030, these should

reduce the gap in exposure to NO

2

between the least and most deprived by 70 per cent

28

.

2.5 Indoor air pollution

Polluted air is a problem not only outside our homes and workplaces but inside them too. It is not

the primary focus of this report. However, the WHO estimates that close to four million people

worldwide die prematurely each year due to household (indoor) air pollution (2018 data

29

). This is

a serious problem in countries where solid fuel is the main way to cook and heat homes, and

where ventilation is poor.

In the UK, indoor air quality is affected by domestic gas combustion from cooking and heating.

Other sources of indoor air pollution include wood-burning stoves and open fires, cleaning agents,

VOCs, tobacco smoke, mould, condensation and asbestos. The National Institute for Health and

Care Excellence (NICE) has recently provided guidance on improving indoor air quality

30

.

In recent years, wood burner use has increased. This means its relative contribution to local PM

2.5

is increasing even more rapidly as contributions of other sources like traffic are gradually reduced.

A European Environment Bureau report showed that even Euro-certified 'Eco-stoves' produce 750

times more PM

2.5

per gigajoule of energy than a modern HGV

31

. A recent study found that wood

burning accounts for between 23 and 31 per cent of urban-derived PM

2.5

in London

32

.

2.6 Public Health Outcomes Framework

The Public Health Outcomes Framework (PHOF) examines indicators that help to understand

trends in public health. It also enables local authorities to benchmark and compare their own

outcomes with other local authorities. For example, one indicator looks at the health impacts of

air pollution: the fraction (%) of mortality attributable to long-term exposure to PM

2.5

. This is

calculated using modelled PM

2.5

levels. A graph showing breakdown by borough of the percentage

of mortality attributable to long-term PM

2.5

exposure across London in 2019 is in chapter 5. The

underlying data are in appendix 2 and the Public Health Outcomes framework in appendix 3.

26

http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review

27

https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/air_pollution_and_inequalities_in_london_2019_update_0.pdf

28

https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/air_quality_in_london_2016-2020_october2020final.pdf

29

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/household-air-pollution-and-health

30

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng149/resources/visual-summary-pdf-7022755693

31

https://eeb.org/library/where-theres-fire-theres-smoke-emissions-from-domestic-heating-with-wood/

32

https://uk-

air.defra.gov.uk/assets/documents/reports/cat05/1801301017_KCL_WoodBurningReport_2017_FINAL.pdf

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

15

2.7 The Cost of Air Pollution

The 2019 Clean Air Strategy

33

estimated air pollution in England could cost £5.3bn a year in terms

of health and social care by 2035. This is if no action is taken and includes both PM

2.5

and NO

2

. This

is a cumulative cost for health conditions strongly associated with air pollution: coronary heart

disease; stroke; lung cancer; and childhood asthma. When health issues with weaker evidence of

association are also added, the costs could reach £18.6bn by 2035. These include chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease; diabetes; low birth weight; and dementia. Air pollution can impact

people of working age, which can also have economic effects, for instance, if they must take days

off work. The Confederation of British Industry (CBI) estimates that improving our air quality could

benefit the UK’s economy by £1.6bn each year. This would be by preventing premature deaths

and providing three million additional working days. It also found that cleaner air in London would

benefit the city’s local economy by £500m, almost one third of the national yearly benefit

34

.

33

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/clean-air-strategy-2019

34

https://www.cbi.org.uk/media/5539/2020-09-cbi-economics-caf-report.pdf

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

16

3 POLICY AND LEGAL FRAMEWORKS FOR IMPROVING AIR

QUALITY

3.1 World Health Organisation (WHO)

Most air quality legislation in Europe and the UK is derived from health-based evidence provided

by the WHO. The WHO has published various guidelines for both global air quality and European

air quality based on the latest worldwide research. In September 2021, the WHO announced

changes to its guideline air quality limits (previously published in 2005). The annual PM

2.5

limit has

reduced from 10 μg/m

3

to 5 μg/m

3

and annual NO

2

from 40 μg/m

3

to 10 μg/m

3

.

The Mayor’s current ambition is to meet the 10 μg/m

3

threshold for PM

2.5

by 2030. Many of the

Mayor’s strategies and policies (London Plan, LLAQM Guidance, London Environment Strategy)

refer to the WHO limits. This will continue to mean the WHO limits at the time of writing, which

was 10 μg/m

3

. Meanwhile, the Mayor continues to work for a zero-pollution city. This includes

efforts to achieve the health-based guidelines that WHO originally set for 2030 mindful of the

impacts on Londoners. He will also continue to lobby for a 10 μg/m

3

threshold for PM

2.5

by 2030.

3.2 EU Directive

The European Union has issued an air quality Directive (2008/50/EC – the “Air Quality

Directive”).

35

The directive sets standards for a range of pollutants considered harmful to human

health and the environment.

The UK is no longer a European Union member. However, the Air Quality Directive is now a part of

UK domestic legislation through the Air Quality Standards Regulation

36

.

The directive standards include limit values, which are legally binding and must not be exceeded.

These limit values include a concentration value for the pollutant, an averaging period over which

it is measured and when these should be achieved. In some case, it also includes an allowable

number of exceedances of the value per year. The directive also includes target values, which are

set out in the same manner as limit values. However, these should be reached where possible by

taking cost-effective measures.

3.3 UK Air Quality Policy

The Air Quality Standards Regulations 2010

The Air Quality Standards Regulations 2010 include criteria for determining how to assess

achievement of the limit values. This includes consideration of locations and length of exposure in

relation to the averaging period of the limit values. In addition, the regulations state sampling

points must be sited where the highest concentrations occur, and people exposed for longer

35

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/air/quality/legislation/existing_leg.htm

36

www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2010/1001/contents/made

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

17

periods of time. These should be significant in relation to the averaging period of any limit value

(that is, 15 minutes, one hour, 24 hours etc).

The limit values for the UK Air Quality Standards and the updated WHO guideline limit values are

shown below in table 2. The UK Air Quality Standards limit values for NO

2

were not met in parts of

Greater London in 2019. However, the number of Londoners living in areas exceeding the UK Air

Quality Standards for NO

2

fell from over 2 million in 2016 to 119,000 in 2019, a reduction of 94 per

cent.

In 2016, the whole of London exceeded the previous WHO guideline limit for PM

2.5

of 10 μg/m

3

.

The latest data from LAEI2019 shows there are now almost 1.2 million Londoners living in areas

below the 10 μg/m

3

limit and there has been a 19 per cent reduction in PM

2.5

across the whole of

the city since 2016. However, with the WHO guideline limit for PM

2.5

reducing to 5 μg/m

3

, there is

still work to be done to ensure Londoners can breathe clean air.

Table 2 Air Quality Standards Regulations and updated WHO guideline values

Clean Air Strategy, 2019

The Government’s Clean Air Strategy

41

provides a policy framework for air quality management

and assessment in the UK. It sets out these proposals in detail and indicates how devolved

administrations intend to make their share of emissions reductions. It identifies air quality

37

200 μg/m

3

hourly average is not to be exceeded more than 18 times a year

38

A mixture of particles and/or liquid droplets in the air that have a diameter less than 2.5 micrometres across (one

400

th

of a millimetre).

39

In 2020, the annual mean limit value was reduced to 20 µg/m

3

.

40

A mixture of particles and/or liquid droplets in the air that have a diameter less than 10 micrometres across.

41

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/clean-air-strategy-2019

Pollutant

UK Air Quality Standards

(EU Limit Value)

WHO guideline value

(2021 update)

NO

2

40 μg/m

3

annual mean

200 μg/m

3

1-hour mean

10 μg/m

3

annual mean

15 μg/m

3

1-hour mean

37

PM

2.5

38

25 μg/m

3

annual mean

39

5 μg/m

3

annual mean

15 μg/m

3

24-hour mean

PM

10

40

40 μg/m

3

annual mean

50 μg/m

3

24-hour mean

15 μg/m

3

annual mean

45 μg/m

3

24-hour mean

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

18

standards and objectives for key air pollutants which are designed to protect health and the

environment. The Government has since brought forward plans to end the sale of new

conventional petrol and diesel cars and vans to 2030

42

. This is ten years earlier than previously

proposed.

Environment Act, 2021

The Act introduces a duty on the government to bring forward at least two air quality targets by

October 2022 for consultation. This will be set in secondary legislation. The first will aim to reduce

the annual average level of PM

2.5

in ambient air. The second will be a long-term target (set a

minimum of 15 years in the future). The Environment Act did not include legally binding PM

2.5

targets or provide cities with the powers and funding needed to meet them.

3.4 Local authority responsibilities

Under the Environment Act 1995

43

local authorities have a statutory responsibility in Local Air

Quality Management (LAQM). This is to make sure that the national air quality

objectives (appendix 1) will be achieved by the relevant deadlines. If a local authority finds any

places where the objectives will not be achieved, it must declare an Air Quality Management Area

(AQMA) there.

Much of London has been designated AQMAs. The DEFRA website has an interactive map of all

AQMAs in the country. Local authorities which have wholly or partly designated their boroughs as

AQMAs must under LAQM produce an Air Quality Action Plan (AQAP)

44

. AQAPs set out how local

authorities, working with other agencies, will use their powers to meet the air quality objectives.

The Mayor’s London Local Air Quality Management (LLAQM) framework

45

is the statutory

process for London’s local authorities to review and improve local air quality. In March 2019

boroughs were consulted on a range of updates and improvements to the LLAQM. After a

successful consultation, the new LLAQM was published in October 2019. The updates were done

to:

• ensure boroughs are taking ambitious action, which is properly coordinated at the regional

level, and which supports Mayoral objectives. This includes those set out in the London

Environment Strategy.

• ensure that London boroughs continue to work towards achievement of WHO guideline

values for pollutants even when legal limits are met.

42

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-takes-historic-step-towards-net-zero-with-end-of-sale-of-new-

petrol-and-diesel-cars-by-2030

43

www.environment-agency.gov.uk/netregs/legislation/.../107183.aspx

44

http://uk-

air.defra.gov.uk/reports/cat09/1107211126_Mapping_Action_Plan_Guidance_Final__Report_April_2011.pdf

45

https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/environment/pollution-and-air-quality/working-london-boroughs

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

19

• update information in the guidance documents to reflect new research, policies, and

priorities.

There are 187 Air Quality Focus Areas in London. These are locations that not only exceed the

national air quality objective for NO

2

but also have high levels of footfall. These areas were

identified in the LAEI 2010 as requiring interventions to help reduce emissions and personal

exposure. This is not an exhaustive list of London’s hotspot locations. However, it is where the GLA

believe the problem to be most acute. We have selected Air Quality Focus Areas based on the

following factors:

- Baseline air quality for NO

2

and PM

10

by 20m grid resolution

- Locations where air pollution limit values have been exceeded

- Level of human exposure

- Local geography and topography

- Local sources of air pollution

- Traffic patterns

- Future predicted air quality trend

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

20

4. AIR QUALITY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT OF

COMPLIANCE

There are several health and environmental strategies which are relevant to air quality. Details of

these can be found in appendix 4.

4.1 Air Quality Monitoring in London

London’s air quality is constantly monitored by high-accuracy Automatic Reference-Level monitors

at over 100 different locations. Most of these are owned and paid for by London’s boroughs.

These sites are mainly managed through the London Air Quality Network (LAQN) delivered by the

Measurement Team at Imperial College. Ricardo Energy and Environment also run several of these

sites. More information on this network is available on the Air Quality England website.

There is minimal PM

2.5

monitoring within the London network. We encourage boroughs to

consider increasing PM

2.5

monitoring capacity as this pollutant has the greatest impact on human

health.

Analysers on Air Quality England and the LAQN are Defra-approved and calibrated and maintained

in accordance with its technical guidance on air quality monitoring. You can read more here about

Defra’s approval method for gas analysers and particulate instruments.

The LAQN is supplemented by low cost Breathe London monitors and diffusion tubes. Breathe

London’s street-by-street sensor air quality monitoring system is being used to analyse harmful

pollution in toxic hotspots across the city. These include near schools, hospitals, construction sites

and busy roads. These data will support policymaking and help inform and engage local

communities. However, it is not a replacement for the Reference-Level monitors which are vital

for assessing trends and compliance with legal air quality limits. We recently launched two new

ways for people, businesses and communities to join the Breathe London Network. The Breathe

London Shop is intended for those who already have funding. There is also the Breathe London

Community Programme through which communities can apply for 10 fully funded nodes in this

round.

We are working towards consolidating these data, so they are freely available in one location on

the Breathe London website.

4.2 Communicating levels of air pollution

The Daily Air Quality Index

The Daily Air Quality Index (DAQI) offers information on levels of air pollution and provides

recommended actions and health advice. The index is numbered 1-10 and divided into four bands

(low 1-2, moderate 4-6, high 7-8, very high 9-10). This provides detail about air pollution levels in a

simple way, like the sun index or pollen index. The DAQI and its associated messaging are currently

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

21

being reviewed. This follows the Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah inquest and the need to include more

specific messaging for different population groups

46

.

Step 1: Determine whether you (or your children) are likely to be at-risk from air pollution. Adults

and children with heart or lung problems are at greater risk of symptoms. Older people are more

likely to suffer from heart and lung conditions than young people. It therefore makes good sense

for them to be aware of current air pollution conditions. Children with asthma may notice they

need to use their reliever medication more on days when air pollution levels are higher than

average.

Step 2: If you may be at-risk, and are planning strenuous activity outdoors, check the air pollution

forecast.

Step 3: Use the health messages corresponding to the highest forecast level of pollution as a

guide.

Mayor’s air quality alerts system

The Mayor’s air quality alerts system communicates to Londoners on days where air pollution is

elevated. It uses stakeholder organisations’ networks and messages displayed in public locations

(including bus countdown signs). It issues alert communications in several formats to reach as

many Londoners as possible. The system uses the same criteria as the DAQI.

During periods of moderate, high and very high air pollution the Mayor’s Air Quality Alert system

sends warning emails to signed-up stakeholders. This includes over 3,300 school contacts. Alerts

and guidance are also available via social media and the London.gov website.

When a high and very high air pollution day is forecast, air quality alerts are displayed at many

public locations across London. This includes all bus stop Countdown signs, the road network and

on the London Underground. These are combined forecasts - meaning they are based on a

number of public forecasts: airText, Defra (Met Office) and Imperial. Furthermore, for high and

very high air pollution episodes we also alert the London Resilience Forum (which includes the

NHS and UK HSA). This action enables more Londoners to be reached via their networks.

Work is underway to improve the reach of the alerts especially for vulnerable groups, including

understanding how alerts can work within health care settings. Local authorities can play a key

role in making this happen through their local health, education and social care networks and

involvement in integrated care systems. To find out more and for support on working with local

NHS networks, please email [email protected].

AirTEXT

airTEXT provides information on the level of pollution in an area using ‘low’, ‘moderate’ and ‘high’

bandings. Whenever moderate or high levels of pollution are expected, subscribers to the airTEXT

46

Government responds to Coroner after Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah inquest - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

22

service receive a text message, call or voicemail. This enables the recipient to determine what

steps they should take to prepare themselves for the expected level of pollution. For example,

taking a different route/mode of transport to work, keeping their medication with them or not

exercising outside on certain days. Currently around 10,000 people use the airTEXT service

through text, Twitter or the website.

4.3 Actions already taken to clean up London’s air

The Mayor is committed to cleaning up London’s air and is delivering an ambitious action plan to

tackle this problem. He has introduced a range of hard-hitting measures to reduce air pollution

and protect public health. These include:

Incentivising the use of cleaner vehicles. Much of the improvements in air quality seen in London

since 2016 can be attributed to the Central London ULEZ (figure 5). The ULEZ operates 24/7 daily,

within the same area of central London as the congestion charge. In October 2021, the ULEZ

expanded up to but not including, the North and South Circular Roads. Most vehicles, including

cars and vans, need to meet the ULEZ emission standards, or pay a daily charge to drive in the

zone.

In the first 10 months of the central London scheme (before the pandemic), the ULEZ had already

delivered a range of benefits:

ULEZ

impact

Figure 5 Trend in NO

2

in London vs no ULEZ scenario

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

23

• Trend analysis shows in February 2020 concentrations of NO

2

at roadside sites in the central

zone were 39 µg/m

3

less than in February 2017

47

. This is a fall of 44 per cent. After the first

ten months of operation average compliance with ULEZ standards were 79 per cent in a

24-hour period. This was 77 per cent in congestion charging hours. This is far higher than 39

per cent in February 2017 and 61 per cent in March 2019, the month before the ULEZ was

introduced.

• Analysis was carried out to determine the directly attributable impact of the ULEZ. In the

first two months of 2020. NO

2

concentrations in central London were on average 29 µg/m

3

lower than they would have been otherwise. This equates to a reduction of 37 per cent.

• Preliminary estimates indicate that by the end of 2019, the ULEZ had reduced NO

x

emissions

from road transport in the central zone by 230 tonnes. This is a reduction of 35 per cent.

• The ULEZ is also helping to tackle the climate emergency. Preliminary estimates indicate that

by the end of 2109, the ULEZ had reduced carbon dioxide (CO

2

) emissions from road

transport in the central zone by 12,300 tonnes. This is a reduction of six per cent.

• It’s too early to measure most long-term health benefits. However, we have commissioned

Imperial College London to measure changes in asthma exacerbations and hospital

admissions

48

.

• Compliance has steadily increased since its introduction. In May 2021, some 87 per cent of

vehicles seen in the central zone on an average day met the strict ULEZ emissions standards.

The expanded ULEZ was launched on 25 October 2021. It operates up to, but not including, the

North Circular Road and South Circular Road to create a single, larger zone. Nearly four million

people live within the expanded ULEZ zone. Here, six in ten households do not own a car yet suffer

poor air quality in part caused by polluting vehicles. The compliance rate (percentage of vehicles

detected in the zone that meet the strict emissions standards) during the first month was 92 per

cent

49

. This is a 53 per cent increase on the 2017 compliance levels of 39 per cent. On an average

weekday, there were 47,000 fewer non-compliant vehicles in the expanded zone than the two

weeks before the scheme was introduced. This is a 37 per cent reduction in non-compliant

vehicles. There were also 11,000 fewer vehicles driving at all.

The ULEZ expansion will result in a 30 per cent reduction of road transport emissions of NO

x

. This

means that 92 per cent of roads in London were expected to comply with legal limits for NO

2

by

the end of 2021. Combined with other measures, this puts us on track for legal compliance by

2025 at the latest.

Since 1 March 2021 most heavy vehicles, including lorries buses and coaches, have had to meet

the Euro VI emission standards of the London-wide Low Emission Zone (LEZ). These standards are

the same as the ULEZ meaning there is only one charge for heavy vehicles operating in London.

47

In February 2017 the Mayor confirmed the introduction of the T-charge as a stepping-stone for the ULEZ and this

can be seen as the start of the accelerated change in the vehicle fleet as Londoners and businesses prepared for the

new schemes and buses on routes in central London began to be upgraded to become ULEZ compliant

48

Health Impact Assessment of Air Pollution on Asthma in London | London City Hall

49

https://www.london.gov.uk/WHAT-WE-DO/environment/environment-publications/expanded-ultra-low-emission-

zone-first-month-report

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

24

Six months on from their introduction, these changes are already delivering results

50

. Ninety-five

per cent of large and heavy vehicles operating in London met the standards in August 2021. This is

up from 48 per cent in February 2017 when the scheme was announced.

The LEZ also has significant benefits outside of London. Independent analysis shows that vehicles

passing through London’s Low Emission Zone went through 95 per cent of towns and cities in

England and Wales. This has brought cleaner air to a combined population of 18 million people.

The Mayor has invested over £61m in funding for scrappage schemes that helped small

businesses, charities operating minibuses and low-income and disabled Londoners. These schemes

have helped replace nearly 15,000 older, more polluting vehicles. Over the past two and a half

years the Mayor’s scrappage schemes have proved very popular. Combined, they have helped

thousands of Londoners and small businesses prepare for the ULEZ and its expansion. Demand for

the schemes has been consistently high throughout that time. It shows how ordinary Londoners

are taking the steps they need to clean up London’s filthy air well in advance. The Mayor continues

to make the case to Government to fund a targeted national scrappage scheme.

Cleaning up London’s bus fleet. The Mayor continued transforming London’s bus fleet by phasing

out pure diesel buses and committing to buy only hybrid or zero-emission double decker buses

from 2018. As of 1 January 2021, all buses in Transport for London’s (TfL’s) 9,000-strong core bus

fleet meet or exceed the cleanest Euro VI emission standards. This effectively makes the whole

city a Low Emission Bus Zone and reduces bus-related NOx emissions by 90 per cent. There are

currently over 600 zero emission buses in the fleet. London now has the largest zero emission bus

fleet in Western Europe.

Cleaning up the taxi fleet. The Mayor is phasing out diesel taxis to help make London’s taxi fleet

the greenest in the world. Since January 2018, TfL policy has been for all newly registered taxis to

be Zero Emission Capable (ZEC). To support this, in 2017 the Mayor provided funding for taxi

delicensing, to help get rid of the oldest, most polluting diesel black cabs from London’s fleet.

There are currently well over 5,000 ZEC, including more than 100 fully electric, taxis in operation in

London. This is from a baseline of zero in 2017.

Cleaning up private hire (minicabs). Private hire vehicles are also subject to strict emission

standards. As of 1 January 2020, private hire vehicles under 18 months must be ZEC when licensed

for the first time. From 1 January 2023, this will apply to all private hire vehicles licensed for the

first time. With their 10-year age limit, this will help London’s private hire fleet be zero emission

capable by 2033 at the latest. There are now over 14,000 Zero Emission Capable private hire

vehicles.

Reducing air pollution from other, non-road sources. The Mayor is also acting on non-road

sources of air pollution, including construction. This includes the unique Non-Road Mobile

Machinery Low Emission Zone (NRMM LEZ). This has eliminated over 16.5 tonnes of PM and 297

tonnes of NOx emissions from construction between 2016 and 2019. The project has since been

50

https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/lez_six_month_on_report-final.pdf

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

25

expanded from the initial 13 boroughs and now covers the whole of London. It is managed by

Merton.

Cleaning up the air around schools. Since 2018 the Mayor has spent more than £1m on air quality

action at schools and nurseries. This includes auditing the air quality at 50 primary schools and 20

nurseries in the city’s most polluted areas. It also includes funding measures to help schools and

nurseries reduce local pollution. Based on the positive results of these pilot programmes this

approach is now being replicated by several London boroughs.

In February 2021 the Mayor launched the London Schools Pollution Helpdesk. This aims to support

schools across the city to carry out air quality audits and implement recommendations. Progress in

this area is particularly urgent for schools in Air Quality Management Areas. Public health

departments should be aware of the school audit programme. All schools, particularly those near

main roads, should perform air quality audits.

Cleaning up air pollution hotspots in London boroughs. The Mayor’s Air Quality Fund of £22m has

supported a variety of local and pan-London projects to improve air quality. For example, the

Hackney Low Emission Neighbourhood contributed to an estimated 16 per cent reduction in local

NOx emission. Find out more about Low Emission Neighbourhoods here.

Expanding London’s electric vehicle charging infrastructure. The Mayor has supported delivery of

over 300 rapid charge points – from zero in 2016 – and over 3,000 standard charge points. This

includes London’s first rapid charging hub at Stratford International. Two further hubs are planned

at Baynard House, City of London and Glass Yard, Greenwich. London now has over 600 rapid

charge points and over 8,000 residential charge points, a third of the UK’s total. These have been

delivered thanks to leadership and effective collaboration between the public and private sectors.

Empowering Londoners to take action to reduce their exposure to pollution. Alongside a

comprehensive air quality monitoring network, the Mayor operates a system of alerts on the days

with the worst air pollution. This includes providing information on more than 2,500 countdown

signs at bus stops. See section 4.2 for more on communicating levels of air pollution.

As well as the GLA funded Breathe London network, Sutton, Kingston, Merton and Richmond upon

Thames are using the network to install their own monitors. They are installing an additional 131

air quality sensors as part of the South London Partnership’s InnOvaTe Project. By the end of 2022,

the network will have over 300 sensors

51

.

Case study: School Streets

Between April 2020 and March 2021, over 300 School Streets have been delivered across London

with funding from TfL and the boroughs. The aim is to tackle children’s exposure to air pollution

and improve their health.

51

https://www.breathelondon.org/

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

26

School Streets are initiatives where roads surrounding schools are closed to motor traffic at drop-

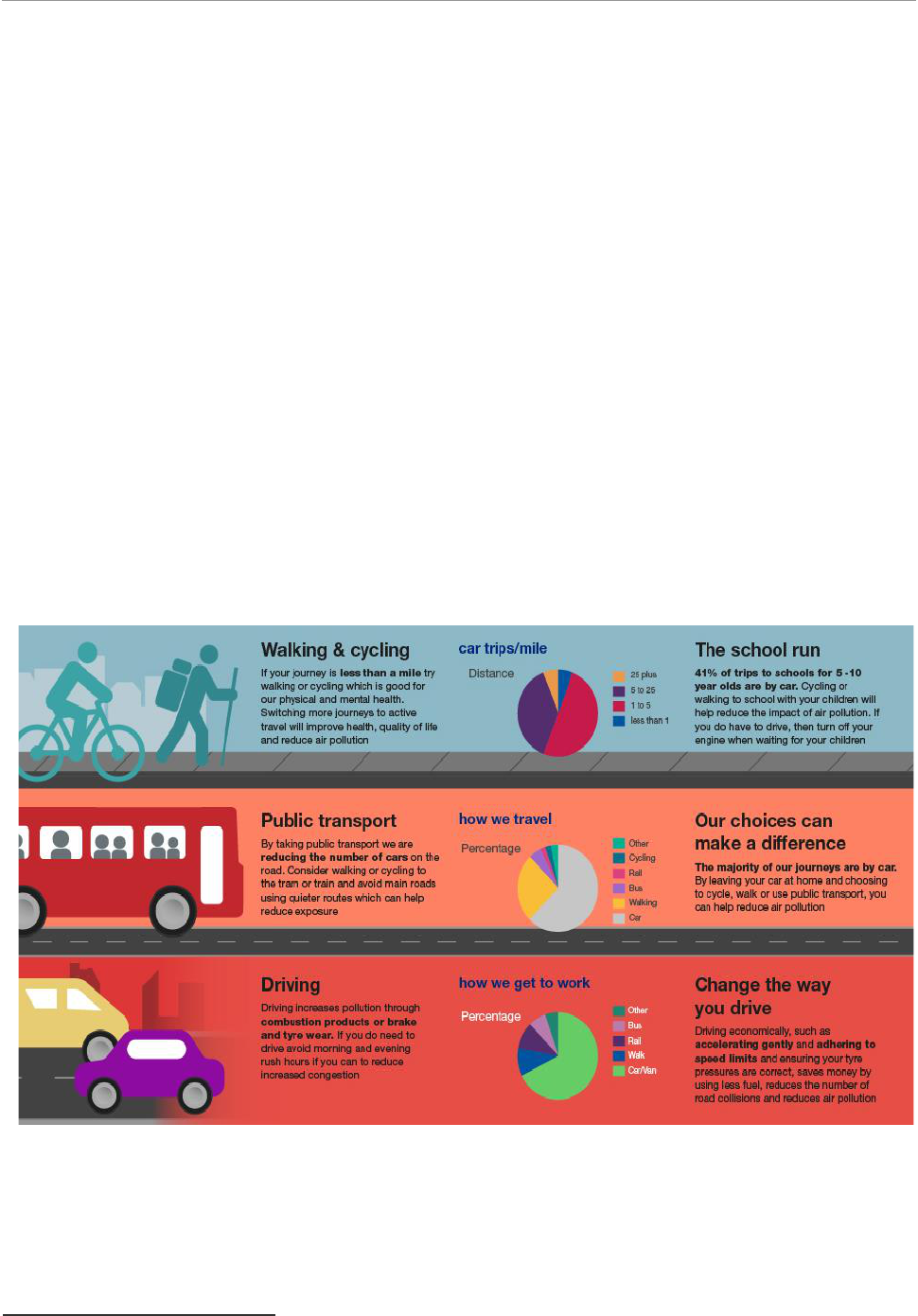

off and pick-up times. This enables children to walk or cycle to school, reducing car trips and

improve air quality. School Streets also provide space for social distancing and help to reduce road

danger around schools, making journeys safer and easier.

To measure their air quality benefits, 30 sensors from the Breathe London network were installed

at 18 primary schools across Brent, Enfield and Lewisham. These record NO

2

levels on School

Streets. It found that stopping traffic at pick-up and drop-off times reduced NO

2

levels by up to 23

per cent at these schools. On average, 81 per cent of parents and carers supported the measures

at their children’s school.

Case Study: Idling Action

Vehicle Idling Action is a London-wide behaviour change campaign. It is funded by the Mayor’s Air

Quality Fund and led by the City of London and London Borough of Camden. The campaign is

helping to reduce localised air pollution caused by motorists leaving their engines running when

parked. The project team works directly with 31 local authorities. It runs school workshops,

engages businesses to use greener vehicles and cargo bikes, offers vehicle fleet training, and

ensures idling regulations are enforced across London.

Since 2016, over 1,500 idling action events have taken place, teaching 3,860 students about air

pollution and health. Their schools have also been supported to act on engine idling by delivering

77 air quality and anti-idling workshops across 31 boroughs. In addition, the project has delivered

Idling Action events at 35 schools and idling hotspots to engage idling drivers. Idlers were asked to

switch off their engines and informed about the impact idling has on air quality and health. In

2021, the project created a four-week billboard, radio and digital advertising campaign – Engine

Off Every Stop (EOES). It ran across London to raise awareness of engine idling and its health

impacts and reached an estimated nine million plus people.

Case study: StreetSpace for London

The emerging recovery from the spring 2020 COVID-19 lockdown presented a challenge for TfL.

This is because public transport was required to run at much lower levels of passenger capacity to

provide space for social distancing. There were concerns that car travel may be more attractive

than before the pandemic. This was due to temporarily lower congestion levels and public

perceptions about the risk of exposure to coronavirus on public transport. However, a potential

car-based recovery was recognised to have major risks to safety, public health, economic recovery

and the environment. In addition, it was contradictory to the aims of the Mayor’s Transport

Strategy.

In response, TfL developed the StreetSpace for London programme, in line with national

government guidance to urgently reconsider how street space is used. The aim was to provide safe

and appealing spaces to walk and cycle as an alternative to car use. Interventions included

temporary cycle routes to extend the strategic cycle network and footway widening to make more

space for people walking. This was applied in town centres and at transport hubs.

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

27

StreetSpace for London focused on rapidly rolling out cycling infrastructure, bus priority,

neighbourhood improvements and lower speeds, using temporary materials and an accelerated

approach. By March 2021, almost 100km of new or upgraded cycle routes were built, and 86km of

bus lanes were upgraded to 24/7. In addition, 2,259 signal timing changes were made to prioritise

people walking, and 88 Low Traffic Neighbourhoods were delivered.

4.4 Impact of COVID-19 on air quality in London

In March 2020 strict measures were introduced to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic in London. This

had a significant impact on NO

2

levels, mainly due to less motor traffic. Once weather effects were

accounted for, reductions were, in general, greater at roadside sites than urban background sites.

The change in NO

2

concentrations from COVID-19 restrictions must be seen within the wider

context of improvements in London’s air quality in recent years. This is due to initiatives such as

the ULEZ. Additionally, during lockdown O

3

and PM concentrations increased highlighting the

importance of non-transport emission sources and the need for action on these also.

In 2020, hourly average NO

2

at all central London sites had already reduced by 35 per cent

compared to the same period in 2017. This was before measures to address the COVID-19

outbreak were introduced. During the first lockdown there was an additional reduction of 26 per

cent. This reduction was even higher at roadside sites (figure 6). NO

2

levels at monitoring sites in

central London remained low in 2021 despite increases in traffic following the end of lockdowns.

Just a 2.7 per cent increase was seen when comparing the first lockdown in 2020 to the same

period in 2021.

Figure 6 Changes in hourly average NO

2

(weekdays, central London)

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

28

5 AIR QUALITY AND ITS HEALTH IMPACTS IN LB LEWISHAM

5.1 Location and monitoring

The London Borough (LB) of Lewisham is situated in South East London. It is made up of 18 wards

and has a population of 303,536

52

.

In 2001 LB Lewisham designated four large areas and a series of ribbon roads AQMAs due to

exceedances in NO

2

and PM

10

. Air quality is monitored at five automatic monitoring sites in the

borough.

The annual mean limit value for NO

2

and for PM

10

is 40 g/m

3

. Concentrations within the limit

value are highlighted in green, exceedances of the limit value are highlighted in yellow, with

exceedances greater than 50% of the limit value indicated in red.

More information about air pollution limit values is included in appendix 1.

5.2 Annual mean concentrations

Annual mean NO

2

concentrations measured at all automatic monitoring stations have constantly

decreased since 2017, and more generally over the 7-year period (2014-2020) for which data have

been reported (see table 3, below).

The automatic monitoring stations at Catford, New Cross and Loampit Vale have previously

breached the annual mean objective of 40 g/m

3

(table 3). Although all sites remained below the

objective in 2020, all sites remain above the WHO guideline limit (10 µg/m

3

). Note, the monitoring

sites are described as either background, kerbside, roadside or industrial background. New Cross

and Loampit Vale are roadside sites, whilst Catford, Deptford Green and Honor Oak Park are

background sites. Specific details of each site can be found in the LB Lewisham annual status

reports.

Table 3 Annual Mean NO

2

Concentration monitoring results (μg m

-3

)

Site

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

Catford

54

43

44

43

38

33

29

New Cross

42

47

46

49

42

38

29

Loampit Vale

56

51

58

54

46

43

36

52

https://directory.londoncouncils.gov.uk/demographics/population/lewisham/

Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Lewisham

29

Site

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

Lewisham Depot

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

19

Honor Oak Park

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

N/A

24

16

The national air quality objective for PM

10

is 40 g/m

3

and for PM

2.5

is 25 g/m

3

. As mentioned

previously, the WHO has recently updated its Air Quality guidelines following an assessment of the