Assistivetechnologypolicy:apositionpaperfromthefirst

globalresearch,innovation,andeducationonassistive

technology(GREAT)summit

Downloadedfrom:https://research.chalmers.se,2019-05-1119:10UTC

Citationfortheoriginalpublishedpaper(versionofrecord):

MacLachlan,M.,Banes,D.,Bell,D.etal(2018)

Assistivetechnologypolicy:apositionpaperfromthefirstglobalresearch,innovation,and

educationonassistivetechnology(GREAT)summit

Disabilityandrehabilitation.Assistivetechnology,13(5):454-466

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2018.1468496

N.B.Whencitingthiswork,citetheoriginalpublishedpaper.

research.chalmers.seoffersthepossibilityofretrievingresearchpublicationsproducedatChalmersUniversityofTechnology.

Itcoversallkindofresearchoutput:articles,dissertations,conferencepapers,reportsetc.since2004.

research.chalmers.seisadministratedandmaintainedbyChalmersLibrary

(articlestartsonnextpage)

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Assistive technology policy: a position paper from the first global research,

innovation, and education on assistive technology (GREAT) summit

Malcolm MacLachlan

a,b,c

, David Banes

d

, Diane Bell

e

, Johan Borg

f

, Brian Donnelly

g

, Michael Fembek

h

,

Ritu Ghosh

i

, Rosemary Joan Gowran

j

, Emma Hannay

k

, Diana Hiscock

l

, Evert-Jan Hoogerwerf

m

, Tracey Howe

n

,

Friedbert Kohler

o

, Natasha Layton

p

, Siobh

an Long

q

, Hasheem Mannan

r

, Gubela Mji

b

,

Thomas Odera Ongolo

s

, Katherine Perry

t

, Cecilia Pettersson

u

, Jessica Power

v

, Vinicius Delgado Ramos

w

,

Lenka Slepi

ckov

a

x

, Emma M. Smith

y

, Kiu Tay-Teo

z

, Priscille Geiser

aa

and Hilary Hooks

a

a

Assisting Living & Learning (ALL) Institute, Maynooth University, Maynooth, Ireland;

b

Centre for Rehabilitation Studies, Stellenbosch University,

Tygerburg, South Africa;

c

Olomouc University Social Health Institute, Palacky University Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic;

d

David Banes

Access, Doha, UK;

e

Centre for Rehabilitation Studies, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa;

f

Lund University, Sweden;

g

CECOPS CIC,

Buckinghamshire, UK;

h

Essl Foundation, Vienna, Austria;

i

Mobility India, Bangalore, India;

j

Department of Clinical Therapies, Faculty of Education

and Health Sciences, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland;

k

Acasus, Hong Kong, Hong Kong;

l

Help Age International, London, UK;

m

AIAS

Bologna onlus, Bologna, Italy;

n

Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK;

o

Hammond Care Braeside Hospital, University of New South Wales,

Sydney, Australia;

p

Department of Health Professions, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Australia;

q

Assistive Technology and

SeatTech Services, Enable Ireland, Dublin, Ireland;

r

Health Systems Research Group, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland;

s

African Disability

Forum, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia;

t

Independent Consultant & Policy Advocate, Brussels, Belgium;

u

Department of Architecture and Civil

Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Goteborg, Sweden;

v

Centre for Global Health, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland;

w

Faculdade de Medicina da University of S

~

ao Paulo, S

~

ao Paulo, Brazil;

x

Olomouc University Social Health Institute, Palacky University Olomouc,

Olomouc, Czech Republic;

y

Graduate School, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada;

z

Melbourne School of

Population and Global Health, Melbourne University, Melbourne, Australia;

aa

International Disability Alliance, Geneva, Switzerland

ABSTRACT

Increased awareness, interest and use of assistive technology (AT) presents substantial opportunities for

many citizens to become, or continue being, meaningful participants in society. However, there is a signifi-

cant shortfall between the need for and provision of AT, and this is patterned by a range of social, demo-

graphic and structural factors. To seize the opportunity that assistive technology offers, regional, national

and sub-national assistive technology policies are urgently required. This paper was developed for and

through discussion at the Global Research, Innovation and Education on Assistive Technology (GREAT)

Summit; organized under the auspices of the World Health Organization’s Global Collaboration on

Assistive Technology (GATE) program. It outlines some of the key principles that AT polices should address

and recognizes that AT policy should be tailored to the realities of the contexts and resources available.

AT policy should be developed as a part of the evolution of related policy across a number of different

sectors and should have clear and direct links to AT as mediators and moderators for achieving the

Sustainable Development Goals. The consultation process, development and implementation of policy

should be fully inclusive of AT users, and their representative organizations, be across the lifespan, and

imbued with a strong systems-thinking ethos. Six barriers are identified which funnel and diminish access

to AT and are addressed systematically within this paper. We illustrate an example of good practice

through a case study of AT services in Norway, and we note the challenges experienced in less well-

resourced settings. A number of economic factors relating to AT and economic arguments for promoting

AT use are also discussed. To address policy-development the importance of active citizenship and advo-

cacy, the need to find mechanisms to scale up good community practices to a higher level, and the

importance of political engagement for the policy process, are highlighted. Policy should be evidence-

informed and allowed for evidence-making; however, it is important to account for other factors within

the given context in order for policy to be practical, authentic and actionable.

ä IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

The development of policy in the area of asssitive technology is important to provide an overarching

vision and outline resourcing priorities.

This paper identifies some of the key themes that should be addressed when developing or revising

assistive technology policy.

Each country should establish a National Assistive Technology policy and develop a theory of change

for its implementation.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 27 February 2018

Revised 19 April 2018

Accepted 19 April 2018

KEYWORDS

Disability; policy; assistive

technology; impairment;

ageing; economics;

accessibility

CONTACT Mac MacLachlan [email protected] Assisting Living & Learning (ALL) Institute, Maynooth University, Maynooth, Ireland

African Network for Evidence to Action on Disability (AfriNEAD).

ß 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

DISABILITY AND REHABILITATION: ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY

2018, VOL. 13, NO. 5, 454–466

https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2018.1468496

Introduction

The aim of this position paper is to outline a broad framework for

discussing the principles that should underlie assistive technology

policies for application nationally or internationally. However, we

will also consider aspects of strategy or action plans where such

aspects are relevant to policy being realistic and achievable, across

often vastly different contexts. Table 1 gives our working defini-

tions of assistive products, assistive technology systems and social

exclusion; one of the major barriers that we argue can be over-

come by assistive technology.

The difference between policy, strategy and action plans is

often not clear, and these terms are used in different and often

over-lapping ways in the literature. Table 2 summarizes how we

use these terms. Based on our engaging with the literature and

our experience of working with a range of stakeholders on these

issues, we suggest these are the most parsimonious and useful

ways of distinguishing between these terms.

It is also important to understand the role of legislation in rela-

tion to these processes. Legislation refers to statutory law; mean-

ing laws that have been approved and enacted by the governing

body of a country – the government. This may also require estab-

lishing State institutions to ensure that the law is practised in the

way intended and that it has the anticipated results. If it does not,

then it may require legislative revision. Sometimes advocacy

groups may undertake strategic litigation, where they take a spe-

cially selected case (which is often representative of the experi-

ence of many people) to court in order to show that the law is

unfair and, therefore, attempt to change the law. Alternatively, a

local authority may have established a policy concerning an

assistive technology system and citizens may have come to rely

on this service; but if it is not legislated for, there may be nothing

stopping the local authorities withdrawing the service at some

future point.

The relationship between policy, strategy and action plans

should be one of "cascading": both operationally (how things are

done), locally and regionally; ensuring that there are effective

mechanisms for national policies to successfully work in often

quite different subnational contexts. This may mean that the same

things are done in somewhat different ways and perhaps by dif-

ferent organizations, groups or individuals, in different places.

Depending on the context, the policy may need to be flexible

enough to foresee diverse ways of achieving the same ends, so

that citizens can achieve the rights legislated for in their

country’s law.

International policies, strategies and action plans on

assistive technology

Assistive technology was first introduced in international policies

through the Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities

for Persons with Disabilities [3], and was further entrenched into

international policies with the advent of the Convention on the

Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [4]. The Incheon

Strategy “Make the right real” is an example of a strategy that

includes the provision of assistive technology as an important

means to achieve disability-inclusive development [5]. The World

Report on Disability [6] has highlighted the need for action to

improve the provision of assistive technology globally, and this

has been reiterated in the Global Disability Action Plan 2014–2021

[7]. Similarly, the Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and

Health 2016–2020 [8], recognizes the vital role of assist-

ive technology.

In the Standard Rules, one of the four rules on preconditions

for equal participation requires States to ensure the development

and supply of assistive products to assist people with disabilities

to increase their level of independence and to exercise their

rights. As important measures to achieve the equalization of

opportunities, States should ensure the provision of assistive prod-

ucts according to the need. Besides supporting the development,

production, distribution and servicing of assistive products, States

are to support the dissemination of knowledge about them.

States should also recognize that all who need these products

should have access to them, which includes financial accessibility.

Assistive products should be provided free of charge or at such a

low price that people requiring AT or their families can afford

them. Moreover, States should consider requirements of girls and

boys concerning the design, durability and age-appropriateness of

assistive products [3].

In contrast to the general approach of the Standard Rules, the

CRPD is more selective in mentioning assistive technology as a

measure that States should take to promote, protect and ensure

the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental

freedoms. However, assistive technology measures are not

included – at least not explicitly – in all relevant CRPD articles.

Despite this limitation, the principles of Article 3 on non-discrimin-

ation, equality of opportunity, and equality between men and

women, as well as Article 5 on elimination of discrimination on

the basis of disability, infer that States are to ensure that all peo-

ple, irrespective of disability, gender and age, have access to

affordable assistive products [9].

It is also important to note that accessibility (of which access

to assistive technology is a part) is a precondition to the enjoy-

ment of other rights. The CRPD Committee’s second General

Table 1. Definitions of assistive products, assistive technology systems and

social exclusion.

An assistive product is “any product (including devices, equipment, instruments,

and software), either specially designed and produced or generally available,

whose primary purpose is to maintain or improve an individual’s functioning

and independence and thereby promote their wellbeing” [1]. The term

“assistive technology” is often used as a generic term.

Assistive technology systems refer to “the development and application of organ-

ized knowledge, skills, procedures, and policies relevant to the provision, use,

and assessment of assistive products” [1]. This therefore includes training in

the use of assistive technology and other infrastructure and technologies,

such as ICT, that promote the effectiveness of assistive technology.

Social exclusion is " … a complex and multi-dimensional process … [which]

involves the lack or denial of resources, rights, goods and services, and the

inability to participate in the normal relationships and activities, available to

the majority of people in a society, whether in economic, social, cultural or

political arenas. It affects both the quality of life of individuals and the equity

and cohesion of society as a whole” [2].

Table 2. Defining and differentiating policies, strategies and action plans.

Policy is a set of principles adopted or proposed by a government, party, busi-

ness, or individual. It provides the ‘What and Why’ of a course of action. A

policy might for instance be based on principles of equity, social justice, or

entrepreneurship and mandate equitable access to specific services

or products.

Strategy provides a map for how policy can be enacted, a blueprint for how to

proceed – it provides the ‘How’ of a course of action. This may include defin-

ing specific goals, analyzing the situation, identifying barriers, specifying

deliverables, or envisaging future scenarios.

Action Plans indicate the way in which strategy will be enacted, they zoom in

on the detail of the action – they address the “Whom, When and Where”

ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY POLICY: GREAT POSITION PAPER 455

Comment was on Article 9: Accessibility [10]. It stresses the inter-

relation of this right with other rights and articles (e.g., Articles 9,

19, 21, 28.2a, 26.3). The Comment asserts that “Accessibility” is

related to groups, whereas reasonable accommodation is related

to individuals. This means that the duty to provide accessibility is

an “ex-ante” duty; meaning that it must be provided before the

fact of it becoming a problem – States must ensure accessibility,

‘up front’ as it were.

The recent Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of

persons with disabilities (2017), while broader than assistive tech-

nology, also describes how to provide rights-based support and

assistance to persons with disabilities, in consultation with them.

The CRPD also indicates that rehabilitation services (including

assistive technology) should be provided as close as possible to

where people live (Articles 26.1b, 25c). This is important for

smaller countries, particularly small island countries, which may

not have assistive technology production capacity. In such situa-

tions, other mechanisms need to ensure adequate procurement

sources. Finally, it is important to note that the responsibility of

States that have ratified the CRPD to ensure affordable provision

of assistive technology is not limited by country borders. Through

Article 32 on international cooperation, States commit to both

technical and economic cooperation on assistive technology.

Assistive technology policy and international

development

It is important to position assistive technology policy within the

broader context of international development generally as well as

more specific policy innovations, and conventions should be dir-

ectly relevant to people with a range of impairments, including

the aging population, who may benefit from the use of assistive

products. The Sustainable Development Goals [11] is a set of 17

goals, internationally agreed-upon, that will guide international

efforts across all countries to target their development efforts to

ensure that “nobody is left behind”. Recently Tebbutt et al. [12]

have illustrated how the achievement of each of these 17 goals

can be facilitated through the incorporation of assistive technol-

ogy, at the population level, when planning to reach these goals.

Assistive products can be conceived as both mediators of social

change (i.e., as a mechanism social change works through) and as

moderators of that change (as a factor that determines the extent

of the change, particularly whether it reaches the more marginal-

ized and vulnerable groups in society).

Within this context a global increase in awareness of the need

for quality, affordable, and reliable assistive products is evident.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has coordinated a collab-

orative effort through the Global Collaboration on Assistive

Technology (GATE) to maintain Assistive Technology at the fore-

front of global and sustainable developments. The remit of GATE

necessitates that it is relevant to all people who experience

impairments in whatever realm and at any age: this includes, for

example, people with non-communicable diseases, injury, visual or

hearing loss, mental health conditions including dementia and

autism, gradual functional decline, or frailty. As such, assistive

technology has an important role to play in promoting access to

education, employment, justice, health and wellbeing; as well as

to the broader cross-cutting values of promoting social inclusion

and participation, independence and autonomy (or chosen inter-

dependence) and leading a dignified and consequential life.

Assistive technology cuts across all sectors and ages, and it is

paramount that policy initiatives recognize and reflect this, rather

than seeking to silo it. This presents policy makers with the signifi-

cant challenge of providing a fully integrated system that is

capable of delivering at the population level, while at the same

time providing specific assistive technology that matches to the

particular needs of individual users (namely the Matching Person

and Technology (MPT) Model [13] or the Human Activity Assistive

Technology Model [14]).

We are living in a rapidly changing world due to the digital

revolution that is not only changing the way people live, learn,

produce and even think; but also changing decision-making proc-

esses, the way information is delivered, problems are solved and

policies are developed. This also makes the distinction between

high- and low-tech assistive products increasingly blurred, and has

the potential to reduce price barriers to high tech solutions. From

a systems perspective the digital revolution should be seen as a

resource for AT user empowerment and participation in reaching

the SDGs, whilst also being careful to avoid the risk of a wider

digital and technological divide by not incorporating these oppor-

tunities systemically [15].

Khasnabis et al. [1] have outlined some of the key components

that need to be addressed in the Assistive Technology system and

the Commentary paper in this special issue [16] describes the

principal P’s that should also be considered in policy develop-

ment. To avoid overlap, we therefore refer the reader to the

MacLachlan and Scherer paper [16] which should be read in con-

junction to this policy paper, particularly for examples of a sys-

tems thinking perspective in Assistive Technology.

Policy gaps

Different types of gaps exist in a number of areas relevant to pol-

icy development in this field. This includes, the identification of

short and long-term evidence that would be useful for policy

making, the use of existing data and information within policy,

fostering policy development in an inclusive manner, the evalu-

ation of existing policy according to human rights and social

inclusion criteria, the implementation of policy, and its monitoring

and evaluation by an appropriate range of stakeholders, especially

the consumers and users of such technology. Very often policy-

makers – including in the health and welfare sectors – are not

familiar with disability, impairment or assistive technology issues,

and are, therefore, not aware of some of the policy challenges in

this area, including the significant challenge of cross-sectoral

working [17].

In many countries, the first step in creating inclusive policy for

assistive technology will be to connect different communities with

an interest in assistive technology; to encourage sharing experien-

ces and best practices, and to simply become aware of stakehold-

ers already working in this field – from various international

organizations, governments, academics, data experts, standardiza-

tion bodies and of course civil society organizations. There are

very different ways to build this community, and the community

will be strongest if a thorough mapping process to establish exist-

ing formats, technologies and stakeholders is undertaken.

Stakeholders who are often overlooked in these processes may

include (but are not limited to), self-advocates for the independ-

ent-living movement, Indigenous peoples in countries where their

inclusion is often marginalized, rural people – especially women

and girls – in poorly resourced settings; people with intellectual

disabilities [18] for whom assistive technology may be especially

beneficial for community living [19], refugees or internally dis-

placed people.

In the APODD (African Policy on Disability and Development)

project [17], three types of policy gaps were identified: A Policy

Awareness Gap – where policy makers knew little about disability-

specific policy instruments (e.g., CRPD), and disability

456 M. MACLACHLAN ET AL.

representatives knew little about the policy instruments used in

mainstream international development. There was also a Policy

Process Gap, even where there was consultation with Disabled

Peoples Organisations (DPOs), the final version of documents

rarely reflected their primary concerns. A third gap, a Policy

Implementation-Monitoring Gap, was also noted, where there were

a lack of explicit indicators for monitoring and evaluation, that

were disaggregated by disability, or had disability specific con-

cerns. We anticipate that many of these gaps will also be appar-

ent for the users of assistive products. For instance, Gowran et al.

[20] give an example of the policy gap that exists in the provision

of wheelchair and seating assistive technology in Ireland; high-

lighting the need for greater awareness of those more distant

from service provision, for example, policy makers. They also indi-

cate the process gap across a number of facets of assistive tech-

nology systems – for example, when accessing services, assessing

and delivering services, tracking, tracing and taking care of assist-

ive technology; providing education for all and advanc-

ing research.

Figure 1 illustrates a simplified conceptualization of the primary

components involved in policy development and implementation.

While some models suggest an idealized linear sequence; again

this is rarely our experience, with the components often being

combined in non-ideal, time-limited and resource-constrained cir-

cumstances, substantially funnelled through the needs of local

contexts and settings. Each of these components should nonethe-

less be addressed through inclusive policy development and

implementation processes [21].

Engaging in policy often requires understanding the triggers

for policy change, or renewal. While the CRPD and other inter-

national policies may well set the context for a discussion on

assistive technology policy; such instruments on their own are

rarely sufficient to propel government towards policy work. So

what sort of argument may engage the attention of government

and policy makers? Evidence concerning the social, economic and

wellbeing benefits, and impact, of assistive technology, may be

especially persuasive. The widespread fragmented delivery of serv-

ices, which are often mainly reactive, with many silos, and often

with many specialists in the “supply chain”, is a very costly way to

provide a service. Thus, arguments addressing the need for

improved efficiency may be relevant. With the increasingly

emphasis on person-centeredness, on co-design and on user-led

initiatives; it may also be argued that the ethos of the assistive

technology sector, is out of kilter with government policy else-

where, and, therefore, serves to diminish its coherence and overall

effectiveness.

It is also crucial not to underestimate the challenges of produc-

ing good policy in this domain. For instance, policy has to be

across all sectors, in the same way that people live across all sec-

tors. It also needs to consider the whole-life-span approach to

people’s lives. These are both difficult for government, requiring

cross-ministerial work and for government to commit to long

term planning, which may not be expedient for shorter-term polit-

ical gain. More generally, for governments to have a policy on AT,

it has to be made clear that it is all AT i.e., everything from walk-

ing sticks to digital health; and this also fits in with holistic and

person-centred care and support. However, policy is often most

influenced by financial rewards for doing something, or financial

penalties (through prosecution or reputational damage) for not

doing something. The economic case for assistive technology,

therefore, needs to be strengthened and is perhaps one of the

most important change factors for improving assistive technology

systems. The economic case will be made most emphatically

when there is evidence of the effectiveness of assistive technology

at the individual, community and Sate/national levels; and so

research, monitoring and evaluation has to target these different

levels in ways that allows for the findings to be integrated

meaningfully.

Empowering people

While it is people who empower people, assistive technology can

contribute to creating the conditions where this is possible. The

CRPD promotes the rights and perspectives of people to be cen-

tral to policy development. A critical route to empowerment is

the establishment, by States, of mechanisms for DPO (Disabled

People’s Organisations) engagement in policy development, moni-

toring and evaluation. Articles 4–3 of the CRPD obligate State to

actively consult with DPOs in decision-making. DPOs can help ori-

ent priorities, provide inputs on what works and what does not,

and suggest and provide strategies to reach out to persons with

disabilities. This is critical to ensure the view of users is considered

and that the assistive technology policy is grounded in a rights-

based approach that truly empowers them.

Figure 1. Components of the policy process (reproduced by permission [21]).

ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY POLICY: GREAT POSITION PAPER 457

In addition to Articles contained within the CRPD, research sug-

gests that around a third of assistive products that are provided

may go unused; providing a powerful pragmatic and economic

argument for AT user involvement and training. In other contexts,

this perspective, most recently referred to as PPI ( “public and

patient involvement”) recognizes that public participation enhan-

ces the design and delivery of better services [22]. Research also

indicates that the greater the extent to which such participation is

formalized in established structures, the more satisfactory are the

results [23].

This presents policy makers with an intriguing contradiction. If

policy development or reform is to effectively address the needs

of those who have been marginalized by mainstream society (and

previous policy), then such processes need to be explicitly disrup-

tive – meaning they need to explicitly change the structures that

oppress and marginalize. Structures in the process of policy

reform need to be established to “institutionalise disruption” (see

[21]). This may mean, for instance, re-imagining systems for the

delivery of assistive products, it may mean the development of a

new cadre working across a range of assistive products; it may

mean self-assessment for some assistive products. Stronger user

involvement in the policy process also presents the opportunity

to potentially uproot and transform prevailing power structures

that may, by design or default, be perpetuating a lack of access

to assistive products.

Our overarching schematic of the strategic issues for assistive

technology systems depicts the interlocking areas of People,

Place, Pace, Personnel, Products, Provision and Policy; it is pre-

sented in Figure 3.

Progressive bridging of the assistive technology

system gap

We base our conceptualization of access on the General Comment

of the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and

Cultural Rights (2000), and we then apply this to the assistive

technology systems in a country. According to the General

Comment a State should have policies and programs that pro-

mote the availability (sufficient quantities), accessibility (both

physically, economically and in terms of provision of information),

acceptability (culturally, socially, gender and age appropriate),

adaptability (appropriate to local contexts) and quality (in terms

of safety, efficacy and usability and being evidence-based) of

assistive products and services. These criteria – known as the

“AAAAQ”–should also be adopted with regard to the rights of

participation, accountability and transparency, in their perform-

ance. We also supplement this with two additional, and crucial,

“A”s for assistive technology. The first additional A – Affordability

– is so crucial for this sector that it needs to be unpacked from

the concept of Accessibility more generally. Second, many people

with functional impairments, particularly (but by no means only)

in resource poor contexts, are simply not aware that many impair-

ments that may be alleviated, or overcome, by the use of assistive

technology. In fact, this applies not just to potential users but also

to health and social care personnel in resource rich and poor

areas. Thus, Awareness is the second addition, as a key moderator

of access to assistive technology.

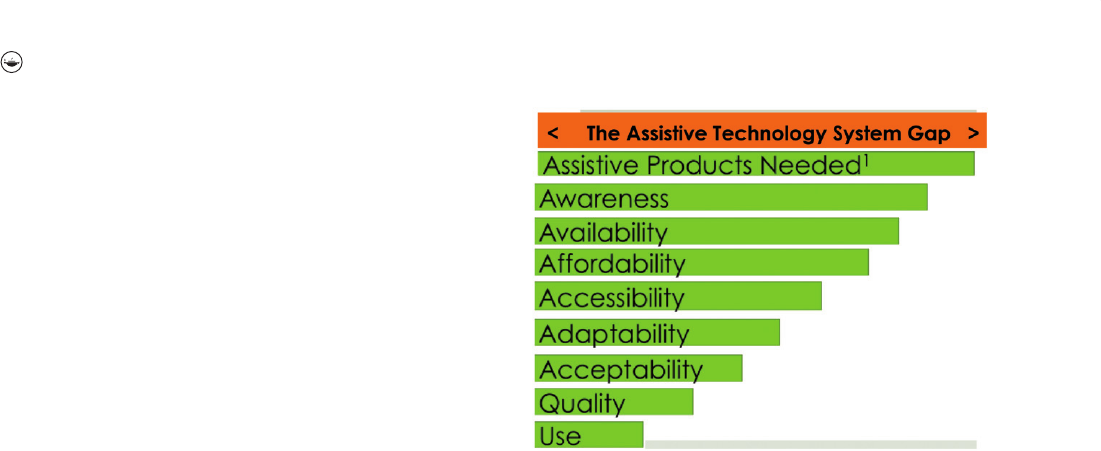

Figure 2 illustrates our understanding of how the real gap

between the need for and provision and use of appropriate assist-

ive products should be unpacked and understood in terms

of access.

Consistent with the CRPD which promotes “progressive real-

ization” (while all rights may not be achievable immediately,

States should be able to show that they are on a path to their

realistic achievement), we recognize that policy should also adopt

this principle (re Pace, discussed in Scherer et al. [16]; along with

and recognition that “domestication” of best practice (as with the

CRPD) may play out differently, in different contexts (refer to

Place, as discussed in Scherer et al. [16]). However, it is clear that

disability and access to assistive technology is often heavily gen-

dered; with girls and women often having less opportunity to

access it; which may also reflect other inequities regarding wealth,

age, ethnicity or geography (e.g., remote and rural areas). So,

while progressive realization and domestication may result in var-

iations between countries, it is very important that these do not

reinforce general practices of discrimination, towards girls, and

women, as a particular example.

A systems-thinking perspective (see [16]) also requires taking a

long-term view of the Assistive Technology system. Responding to

the assistive technology needs of people is not a single step pro-

cess that finishes as soon as the person has an appropriate solu-

tion. Rather, delivering on Assistive Technology involves

supporting people over a longer period in their developing new

or associated technology needs. The participation of empowered

Assistive Technology users in sectors such as education and

employment is highly desirable, as well as their political and cul-

tural participation, but policy makers should be aware that those

sectors need to be prepared to welcome the participation of all.

At micro-level, this means carefully managing change. At the

macro-level, Assistive Technology provision should be seen as a

crucial part of wider efforts to build a more inclusive society.

Good practice in assistive technology systems: a

country case study of Norway

Sund [24] has described the Norwegian Assistive Technology

model, established in 1995. Its primary objectives included (1)

establishing a unified, national system for assistive technology, (2)

addressing users’ practical/functional daily problems regarding the

AT they used, (3) giving the users rights in law to necessary and

appropriate assistive products, free of charge, (4) providing users

with the same level of services regardless of where they live, (5)

establishing a common ICT system for registration of purchases,

distribution, repairs, regular servicing and refurbishment of assist-

ive product, and (6) user involvement in the system and a focus

on the individual strongly emphasized. To facilitate this structur-

ally, Norway established 18 assistive technology centres (hereafter

Figure 2. A schematic representation of Assistive Technology System gaps.

1

Note

this bar chart is not to scale – globally the number of assistive products needed

far exceeds those available; sometimes by a ratio of 10 or more to one, and this

is patterned by socioeconomic factors, marginalization and so on.

458 M. MACLACHLAN ET AL.

denoted AT centres) – one in each county (administrative area) of

the country. Each AT centre coordinates assistive technology activ-

ities within their county, and cooperates closely with the local

health and rehabilitation services, in order to address the users

practical/functional daily problems (see also, Nordic Cooperation

on Disability Issues [25]).

Importantly, it is the local authorities (the municipalities) that

have the fundamental responsibility for health care, and social

and rehabilitation services; including the provision of assistive

products. Trained personnel (usually occupational therapists or

physiotherapists) are responsible for identifying and assessing the

users needs, recommending and providing assistive products, as

well as following up the users situation in daily life.

If appropriate rehabilitation or health care services are not

available in the local community, the individual will be referred to

the AT centre in their county. These centres are centres of excel-

lence serving as a referral system covering the whole county and

they give services and guidance within mobility, hearing, vision,

communication, cognition and the environment. The AT centres

have personnel (such as occupational therapists, physiotherapists,

technicians/engineers, speech therapists, opticians) with expert

knowledge about the application and adaptability of assistive

products. They give guidance to the local authorities and other

stakeholders in the county. More local community authorities ask

for assistance from the AT centre if the local network does not

have sufficient expertise. In some cases, the municipalities and AT

centres cooperate with retailer or suppliers of assistive products in

order to solve the users practical/functional problems. This helps

to ensure that users see professionals with the same expertise

and are given the same level of service regardless of where

they live.

Within the overall national AT system, there are also some

national competence centres with distinct areas of expertise that

also can be called upon by county AT Centres. Based on national

agreements with the retailers and/suppliers, AT centres purchase

assistive products and distribute them to the different municipal-

ities. They also repair the assistive products when needed, and do

regular servicing of electro-medical assistive devices at given inter-

vals. Interestingly, in terms of sustainability, about one-third of the

distributed assistive products are refurbished ones. These recycled

products have had worn parts replaced and the assistive products

are cleaned properly and should be “as new” before being pro-

vided to a new user. The AT centres organize and run yearly train-

ing courses on assistive technology for employees in the

municipalities and hospitals. There is a considerable emphasis on

the assistive products being be safe to use. Table 3 highlights

some relevant statistics regarding the Norwegian AT system, as

of 2016.

While Norway is a comparatively very rich country, its system-

atic-tiered approach to assistive technology is noteworthy, and its

commitment to recycling a significant proportion of its assistive

products – or their components – also demonstrates a strong

commitment to cost-saving. These and other aspects of its

Table 3. Some attributes of the Norwegian Assistive Technology System

(see [26]).

Norway has 5.2 million inhabitants, of which approximately 20% (as of 2015)

live in rural areas (see: http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/norway/

rural-population).

138,150 users received one or several assistive products from the AT centres.

They constituted 2.7% of the population

56.6% of the users were women

64.1% of the users were 67 years of age and older

11.4% of the users were 18 years of age or younger

2,240 US dollars per user or 60 US dollars per inhabitant were spent on

assistive products

37,190 ordinary repairs of the assistive products were performed. 81.0% of

these were performed by technicians at the AT centre (78.0%) or by deal-

ers (22.0%)

78.0% of the assistive products were delivered within the target of 3 weeks

of assessment.

Figure 3. The Norwegian Assistive Technology System model: 18 Assistive Technology Centres, one in each county, cooperate closely with the health care and rehabili-

tation services at the municipal level.

ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY POLICY: GREAT POSITION PAPER 459

geographically inclusive approach may well be relevant to many

more poorly resourced policy contexts.

Areas with different resources may be able to recycle in differ-

ent ways. So, in the case of wheelchairs, reusing a wheelchair

means that it has been cleaned with minor repairs and issued for

reuse; refurbishing means that the wheelchair has been com-

pletely revamped to “as good as new” condition, ready for reissue;

while recycling a wheelchair mean taking it out of commission

and recycling the materials and parts. Policy may indicate the

need for, and prioritize the resources for, some or all of these; and

seek to achieve them in a systemic way. Allowing them to occur

in an ad hoc manner is not likely to be the most efficient use of

resources at a national level.

Some dimensions of assistive technology policy: results

of a stakeholder consultation

Scholl and MacLachlan [27] undertook a literature review, a focus

group with WHO regional representatives, Key Informant inter-

views and three country case studies through in-country inter-

views and document analysis (in South Africa, Philippines and PDR

Laos). They sought to identify what people felt were important

elements to include in the development of a framework to sup-

port countries in developing national assistive technology policies.

Their specific aim was to explore the relevance of policy themes

used in the ground-breaking and now well established WHO

Essential Medicines List, which has the aim of making essential

medicines more accessible, globally. This aim is, therefore, cogent

to the Priority Assistive Products List (APL). The research also

addressed facilitators and barriers for the AT sector across these

different settings. Table 4 summarizes the themes that arose from

this research.

Policy in low- and middle-income countries

It is important to say that many of the critical issues for assistive

technology policy are similar in high-, middle-, and low-income

contexts; thus the challenges in Figures 1–3 are common.

However, in poorly resourced contexts, there are often additional

challenges. As assistive technology presents opportunities to

address social exclusion, the allocation of resources in poorer set-

tings is crucial. Our definition of social exclusion (Table 1) stresses

the “lack or denial of resources, rights, goods and services, and

the inability to participate” and goes on to state that this lack or

denial of resources affects “equity and cohesion of society as a

whole” [2]. Generally, in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC),

the provision of assistive products is inadequate with poorly struc-

tured systems in place to aid service delivery [28,29]. We have

found that policy development in such contexts – and often in

higher-income contexts too – frequently excludes its intended

beneficiaries, and may indeed be undertaken by consultants

unfamiliar with the country in question, and with reference points

related to contexts with much greater resources. Wazakili et al.

[30] in their study of inclusion of persons with disabilities in

poverty reduction strategy processes (PRSPs) in Malawi found that

they often had limited knowledge about the PRSP process, which

partly accounted for their limited participation in policies that are

geared towards poverty alleviation.

In some countries, the situation is poor – there is a negligible

assistive technology industry and/or few professionals to provide

appropriate technologies. Where assistive products are available,

they are often unaffordable to the majority who could benefit

from them. Cheaper assistive products, when they are available,

are often of poor quality, poorly adjusted and serviced, or inad-

equately explained, and thus difficult and off-putting to use [31].

Articles 4 and 26 of the Convention make it clear that ultim-

ately, governments are responsible to ensure that appropriate

assistive technology is available and affordable and that provision

is made for users to be trained to use assistive products [29,31].

Recently both the South African National Departments of

Health and Social Development have drawn from the CRPD to

develop the white paper on disability and rehabilitation frame-

work strategy. Both documents put emphasis on the importance

of available and affordable assistive technology for persons with

disabilities [32]. Yet other research in South Africa suggests that

the failure to effectively implement the health and rehabilitation

articles of the UNCRPD is largely due not only to negative atti-

tudes in society in general [32] but also from government officials

and service providers towards people with disabilities [33] and a

rights-based approach. This certainly incorporates most people

who use assistive products. Fundamentally then, it is not only

improved “systems” but also changed organizational, societal, reli-

gious and cultural attitudes that are necessary to improve access

at the systems and policy level. However, it may be that the

actual use of assistive products can itself change attitudes in a

positive way. In Bangladesh Borg et al. [34] found that people

using assistive products were about three times more likely to

report positive attitudes from neighbours, than did people with

similar impairments who did not use assistive products.

Although stigma towards disability is a worldwide problem, it

is important to stress that in all cultural and economic contexts

there are valuable resources that can be harnessed to promote

assistive technology systems. For instance, in Africa, AfriNEAD

((the African Network for Evidence to Action on Disability) see

[35]) represents a ready vehicle to promote policy dialogue on

assistive technology. Cultural resources such as the Ubuntu phil-

osophy of collective support and harmony can be a facilitative

context in which to develop supportive and empowering services

and opportunities [36]. Of course the Ubuntu ethos can be found

in context elsewhere too: engaging key stakeholder to reflect and

work collectively; to share understanding as a community of prac-

tice for sustainable development in AT and other support serv-

ices [20,37].

The importance of assistive technology for the ageing popula-

tion is now being recognized globally and even in resource-rich

countries it is a significant challenge. For instance, a systematic

review of “intelligent assistive technology ” (IAT; meaning more

technologically sophisticated) for dementias found that while the

IAT spectrum continues to expand rapidly, in volume and variety;

many structural limitations to successful adoption persist. These

include insufficient clinical validation and insufficient focus on

potential user’s needs; and this even in comparatively very weal-

thy countries. In poorer contexts, such as Puerto Rico, Hispanic

older adults with functional limitations living independently, were

found to have unmet assistive technology needs; particularly to

compensate for physical limitations and to increase safety per-

formance, mostly around instrumental activities of daily living [38].

Table 4. Possible elements of, facilitators for and barriers to, the development

of national assistive technology policies.

Elements: Affordability, Financing, Supply Systems, Regulation & Quality

Assurance, Rational Use, Research & Innovation, Human Resources,

Monitoring & Evaluation, Governance

Barriers: Conceptual, Capacity, Civil Society, Financing, Geography, Governance,

Human Resources, Rationale Use, Supply Systems

Facilitators: Civil society, Country Context, Political Will, Strong

Partner Landscapes.

460 M. MACLACHLAN ET AL.

Access to assistive technology continues to be a problem,

often especially so in rural areas. In rural China, this has also been

reported along with the barrier that “vague and complex regu-

lations” constitute their use [39]. For many countries with quite

rapidly aging populations, these challenges will have to be quickly

and systemically addressed by resources being provided on the

basis of well-articulated policy. The focus of much recent innov-

ation and developments in assistive technology has been on high

tech solutions and whilst appropriate there is probably a greater

need for more low tech affordable assistive technology products

for safety and instrumental activities of daily living. There are also

advantages of scale in addressing the accessibility of the environ-

ment in community, workplace and public settings, through

dropped curbs, ramps, lifts and handrails and communication

(e.g., hearing loops).

Assistive technology across the life course

In some countries, 46% of people with disabilities are older peo-

ple (aged 60 or over; https://www.un.org/development/desa/dis-

abilities/disability-and-ageing.html). The proportion of people with

disabilities who are in this older group is likely to increasing in

most countries, in coming years. This being the case it will be

important for assistive technology policy to adopt a life-course

perspective. This should reference to global movement for older

people and their work in advocating for better services, including

assistive technology. Older People’s Associations (OPAs) and

Disabled People’s Organisations (DPO’s) could perhaps have

greater impact on assistive technology policy and provision by

working more closely together; and this is something that can be

promoted through the process policy development [21].

From a life course perspective, we see moments along the

course of our lives where we need to access assistive technology,

not only for permanent use but also short term; and so policy

needs to cater for these different types of scenarios and needs.

The life course perspective also embraces the need for such policy

to be cross-sectoral – for instance, across education, employment

and health. Seeing the assistive technology implications of disabil-

ity, or chronic illness, along the life course, also recognizes that

assistive technology research and practise will have to develop a

much stronger population science ethos; rather than being siloed

in rehabilitation, with another silo in disability, another in educa-

tion, and so on. This surely is the crux of the policy challenge to

social inclusion at the population level.

The economic case for investing in assistive technology

Improved functioning from the use of assistive technology may

have wide ranging positive economic impacts on individuals and

society. As discussed below, the economic benefits stem from

improved health outcomes and quality of life, better education

and employment outcomes, and higher productivity. These bene-

fits could translate into a reduction in the health and social care

costs associated with impaired functioning. More broadly, the

benefits of assistive technology may also extend to a stronger

labour supply and industry development, which would benefit the

economy as a whole.

Assistive technology has been shown to improve health out-

comes and quality of life for people in need, and for care givers.

This includes comparative improvements in overall health

reported by users of wheelchairs [40], quality of life and physical

health among hearing aids users [41–43]; and better quality of life

and reduced symptoms of depression among nursing home resi-

dents who used spectacles [44]. Evidence also shows slower

functional decline and higher likelihood of maintaining independ-

ence among older people living with a disability who received

assistive products and home modification [45]; positive health and

social effects from an accessible home environment among peo-

ple with functional limitation [46]; as well as positive impacts of

assistive products on children with physical impairments and their

caregivers [47]. A systematic review by Chase and colleagues

found that AT and home modifications along with other interven-

tions prevented falls among community-dwelling older adults [48]

(see also Cho et al. [46]).

Evidence suggests that improved health outcomes could

reduce healthcare and social care costs. For example, Bensi et al.

[49] reported savings of e290,000 per person, over a 5-year period

because of increased autonomy, reduced dependence on personal

assistants and improvement in quality of life through greater con-

trol of living spaces through home adaptation, mobility and living

aids, and other AT interventions. The Disability Federation of

Ireland and Enable Ireland [50] also found comparable annual sav-

ings of e59,000 per person, following the provision of environ-

mental control technologies at home. Likewise, Barnard [51]

demonstrated that AT can result in 45% lower costs for funding

authorities in a single year.

Assistive technology also has an important role to play in keep-

ing people living in their own homes, in their own communities.

In reviewing investment to allow older people to remain living

within their own homes Snell, Fernandez and Forder [52] found

that equipment and adaptations led to reductions in the demand

for other health and social care services worth on average £579

per recipient, per annum. Such services lead to improvements in

quality of life of the person, which they estimated to be worth

£1522 per annum in reduced service requirements. Based on an

estimated average scenario and a client base of 45,000 individuals

receiving interventions at a total cost of approximately £270 mil-

lion, it is likely to generate reductions in the demand for health

and social care services worth £156 million, over the lifetime of

the equipment, and to achieve quality of life gains costed at £411

million [52].

The provision of assistive technology could confer positive

impacts on existing and future workforce. The impact could be as

direct and immediate as returning a person to work by providing

a prosthetic limb and rehabilitation; or improving the vision of

workers by providing corrective lenses. For example, workers with

poor vision in Rwanda, not wearing glasses, were three times

more likely to be asked by supervisors to repeat their work of

sorting coffee beans, than after receiving and wearing glasses

[53]. Importantly, assistive technology also helps with laying the

foundation for a stronger future workforce through increasing lev-

els of education and better education outcomes. Earlier fitting of

hearing aids contributes to better language, academic and social

outcomes in children [54]. In China, the provision of free glasses

to children with short-sightedness was found to improve their

performance on mathematics test to a statistically significant

degree [55]. These are important mediators for building skills for

the future workforce.

The cost of retaining an employee who acquires a disability is

considerably less than the cost of hiring and training new employ-

ees. Work Without Limits [56] suggest that such costs range from

$3000 to $22,000 depending on the seniority of the post, consid-

erably higher than the average $500 spent on accommodations.

Parry [57] notes “the average cost to accommodate an employee

with a disability is $500, the benefits can be substantial: employ-

ees with disabilities are five times more likely to stay on the job

than their counterparts without a disability. That translates into

less money and time spent hiring employees.” Work Without

ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY POLICY: GREAT POSITION PAPER 461

Limits [56] suggest that 46% of reasonable accommodations at

work cost absolutely nothing; with another 45% having a one-

time cost, typically around $500. They also assert that employees

with disabilities often exhibit high retention rates, which can

translate into financial savings for employers.

The assistive product market is set to greatly expand in the

near future, fuelled by population growth and increased longevity,

as well as advances in technology. For example, the global market

for assistive products for the elderly and people with disability

was valued at US$14.1 billion in 2015. By 2024, the market is esti-

mated to reach US$26.0 billion, corresponding to a compound

annual growth rate of 7.4% between 2016 and 2024 [58].

In many countries, domestic markets for assistive products and

related industries are relatively new and awaiting further develop-

ment. Developing local industry could not only serve to meet the

local demand at an affordable cost, but also to provide opportuni-

ties for job creation through enhancing local technical capability

and innovation. Furthermore, like other industries, the benefits

would have positive spillover effects to the broader economy

along the value chain of the primary (raw materials), secondary

(manufacturing) and tertiary (service) sectors. The potential of the

sector has been noted by some governments and has been incor-

porated into their economic development plan. For example, the

State Council of the People’s Republic of China has issued a plan

to foster “innovation capability, industry upgrade, effective market

supply and a favourable market environment, to enhance industry

development”, with a view to generating outputs of more than

¥700 billion (US$103.3 billion) from the rehabilitation and assistive

products industry [59]. Other examples include the emerging

hearing device manufacturing sector in a number of countries,

including India, Brazil and Thailand [60].

The argument for the growth of the assistive technology indus-

try within countries may be persuasive for policy-makers, and in

capturing parliamentary interest. At the First Global Assistive

Technology Conference in Beijing (2014) (http://www.ispoint.org/

events/global-conference-assistive-devices-technology-industry),

the Heads of State from China and Germany were present to test-

ify to their country’s support for and interest in assistive technol-

ogy; this was also clearly demonstrated by the strong presence of

manufactures form both countries at the accompanying EXPO

trade fair. The Second Global Assistive Technology Conference,

Beijing 2017, explicitly linked assistive technology to China’s ambi-

tious “Belt and Road” initiative; for increasing its trade and cultural

links with Asia, Africa and Europe. Such initiatives have high-

lighted the importance of policy addressing market shaping.

Market shaping in the assistive technology context refers to

engaging market factors with social equity; balancing these to

allow genuine need due to impairment to develop into reliable

demand for assistive products, and for affordable and quality sup-

ply to embrace social gain, as well as financial profitability [61].

Another relevant policy issue is that many assistive technology

products are viewed by States as medical devices and are subject

to rigorous legislative requirements or subject to particular stand-

ards (for instance, as approved by the International Standards

Organization, ISO). Whilst this may be appropriate in many circum-

stances, it can be restrictive for access in other contexts, where in

particular some lower-tech solutions may be more realistic, more

affordable and more likely to be effectively maintained. Standards

may, therefore, need to be more dimensional than absolute, with

of course minimum standards to ensure safety and the prevention

of harm to users. Onerous legislative requirements also drive up

cost, time to development and can be off putting to investment

by innovators and industry; thus reducing availability and

affordability.

A final and often neglected aspect of assistive technology eco-

nomics is that many types of assistive products can help increase

productivity for those that are not living with a disability – leading

to wider application of current technologies and, therefore,

increasing economic benefits. Indeed, mainstreaming accessibility

and various forms of assistive technology within existing products

is a key focus for many of the leading technology companies

today. So for instance Apple’s development of Siri or Microsoft’s

eye-gaze technology are examples of assistive technologies that

have gone mainstream and can contribute to everybody’s prod-

uctivity and quality of life.

The role of active citizenship

The full and active participation of civil society – in particular

DPOs as organizations representing a diversity of users of assistive

technology – is important in order to authenticate the policy pro-

cess. We highlight three issues where civil society has an espe-

cially important role. Access to relevant information for all social

actors in a timely and accurate way is crucial. In particular, with

regard to persons with disabilities, it is necessary to ensure that

information can be provided in accessible and alternative formats,

in order to promote the full and effective participation of this

group. Civil society is often the provider of accessible formats;

such as through screen readers, screen magnifiers, or text to

speech devices; but also formats not necessarily provided by tech-

nology, such as Easyread or Sign Language.

Capacity building programs in areas such as human rights

advocacy, leadership and awareness raising, designed for and usu-

ally run by civil society organizations, are critical in enabling peo-

ple with disabilities, DPOs and NGOs, to claim rights and develop

focused campaigns on achieving them. Policy needs to identify

channels for how this activity can contribute to policy develop-

ment and implementation. Without providing such channels, and

legitimizing this activity, rights claimers are placed on the

‘outside’, and can be seen as negative and critical of government,

when in fact they are advocating for internationally agreed human

rights principles. Creating a space for meaningful participation –

including DPOs and NGOs as representative organizations – is also

about ensuring the conditions for meaningful participation are

created, in terms of staff sensitized, accessibility of venues and

accessible information and communication. There is thus a corre-

sponding need to heighten awareness within policy-making

domains that those on the ‘outside’ share many of the same goals

as policy makers. It may well be that important lessons can be

learned from the experience of other marginalized groups (such

as women and girls, ethnic minorities and older people) to influ-

ence mainstream policy.

Once completed, these first steps can lead to civil society rep-

resentatives being empowered; this may include forming national

coalitions, meeting government officials to review, monitor and

oversee national policies. It may also involve people with disability

securing leading roles in government, business, education, in fact,

in any area of life. An important role of civil society is also to

highlight the intersectionality of disability and assistive technology

needs. For instance, people with impairments come from all walks

of life and age; they may be men or women; members of indigen-

ous society, who may themselves be marginalized; they may live

in isolated rural areas, or urban slums. To ensure that policy

becomes fully inclusive, these intersectional forms of marginaliza-

tion have to be recognized and taken into account; preventing

different forms of marginalization multiplying disadvantage. For

instance, the use of assistive technology is associated with inclu-

sion and wellbeing even among marginalized groups in very

462 M. MACLACHLAN ET AL.

difficult circumstances; such as children with amputations in Gaza

[62]. However, we recognize that there are often greater barriers

for those with a weaker voice, such as people with intellectual dis-

ability, who also have much to benefit from initiatives such as

GATE [18] and so greater efforts need to be made to address

these barriers.

The International Disability Alliance brings together over 1100

organizations of persons with disabilities and their families; from

across eight global and six regional networks, and will continue to

advocate the global community to create the conditions for the

effective realization of the rights enshrined in the CRPD at country

level. This implies systematic and meaningful consultation with

persons with disabilities (including assistive technology users) and

their representative organizations to guide the definition, monitor-

ing and evaluation of assistive technology policies (in line with

CRPD Article 4.3). IDA and its members are an important conduit

for mobilizing the diversity of users, including most marginalized

groups such as persons with intellectual disabilities, persons with

psychosocial disabilities, persons with deaf-blindness or indigen-

ous persons with disabilities; bringing the perspective of users of

assistive technology, in all service research, procurement and

delivery. IDA, with its Members, is particularly concerned by the

need to frame assistive technology policies that truly respond to

the rights of all persons with disabilities, in particular in low and

middle income countries, to access quality assistive technology, at

an affordable cost, as close as possible to where people live. This

includes influencing assistive technology policies, public procure-

ment policies as well as ensuring that accessibility and reasonable

accommodation, including assistive technology, is included and

properly resourced in all concerned public policies [63].

While civil society has a critical representational and advocat-

ing role – and, in some cases, is a major service provider – it is

also important to ensure that policy cultivates the expectation of

civil duty being shared among all of us. It is, therefore, crucial that

such duty is not partitioned or separated; not a “them” or “us”;

but rather a shared responsibility to be addressed through

acknowledging ownership of the challenges of promoting equit-

able assistive technology systems and working through engage-

ment with people as working as a sustainable community

of practice.

Scaling good practices

National Assistive Technology policies should recognize the poten-

tial of small-scale good practices to be scaled in a variety of ways.

This is particularly important in resource poor contexts, where a

range of different service providers (including different civil soci-

ety organizations) may have developed small-scale but innovative

projects; that lack the infrastructure to be brought to the next

stage. The value of adopting a systematic approach to scaling,

such as Expandnet (http://www.expandnet.net/) (which chimes

with a human rights perspective and with the presence of civil

society actors), is a principle that should be anticipated in policy.

Such scaling may require action at the structural level (scaling-up)

as well as replication (scaling-out) of existing good practices.

Examples of structural change that promote some aspects of the

CRPD have been reported in various countries by the UNPRPD

Programme (see [11]); although none of these projects has as yet

focused on scaling assistive technology initiatives other groups

are working towards this [20].

Why policy and evidence differ

Cairney [64] cites four obstacles to evidence-based policymaking.

First, even where “ the evidence ” exists, it doesn’ t actually tell you

what to do: This may occur because evidence points to problems,

but not solutions; it may focus more on effectiveness than appro-

priateness; scientists may exaggerate or disagree about findings,

implications or implementation methods; evidence may be patchy

because it crosses traditional disciplinary or policy boundaries; or

evidence may be presented in an unsystematic, unfamiliar, or

impenetrable format, perhaps coming from foreign countries

and contexts.

Second, the sort of evidence that is needed, is not what is avail-

able – demand for evidence does not match the supply: Research

funding may prioritize “magic bullet” interventions, that would

reduce or remove the need for political choice; the scientific

method may narrow focus on simplified and controllable variables,

while policy makers seek solution to complex problems; “the

evidence” may be interpreted selectively, or differently by policy

makers; who may need to make decisions quickly amidst uncer-

tainty; need to make decisions, the consequences of which may

take years to unfold and which are influenced by other factors.

Third, in the complexity of policymaking the role of evidence may

be unclear and contested: Many researchers do not understand the

policy process and other stakeholders may know better how to

influence it; the demand for evidence may depend on which gov-

ernment department is involved, which may favour some types or

sources of evidence over others.

Fourth, and perhaps most surprising for researchers, evidence-

based policy making and good policymaking, are not synonymous:

For instance, reducing evidence-policy gaps may mean centraliz-

ing power in the hands of just a few policymakers and ignoring

other sources of knowledge (such as personal experience and

judgement). It may mitigate against public or user involvement, it

may not value consultation with stakeholders with different per-

spectives, and thus it may undermine participatory approaches to

policy making.

We would add a fifth element: that policies should be policy-

based: By this, we mean that a National Assistive Technology

Policy should articulate with other cogent polices; be they inter-

national conventions (e.g., CRPD), best practice in relevant aspects

of regulation and law making [65], or more context-relevant

national polices (for instance, on rehabilitation or inclu-

sive education).

In our view, Assistive Technology policy must, therefore, be evi-

dence-informed, but its fundamental basis must be broader and

more inclusive than of only evidence that accords with strictly sci-

entific standards. A variety of stakeholder views, contextual, cul-

tural, resources and systems perspectives must also inform policy;

ideally with these perspectives being assessed and synthesized in

systematic and transparent ways that also further increases their

credibility. While some forms of evidence review, such as realist

synthesis, give much more emphasis to contextual and process

issues than do conventional systematic reviews (see for instance

[66,67]) for participation to be genuine, there can never, in prin-

ciple, exist a one-to-one transformation from scientific research to

policy: this is neither realistic nor desirable.

Policy needs political engagement

Many of those who are evidence-producers (researchers, practi-

tioners, users) are often unsure how, or simply unwilling, to

undertake effective political engagement. At other times, advo-

cates are frustrated by the difficulty of getting assistive technol-

ogy on the political agenda. People may talk of political

engagement wistfully; in opaque terms, as a factor outside their

control; or in negative terms, as a vaguely dirty business that is a

ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY POLICY: GREAT POSITION PAPER 463

necessary evil. The reality of the demands on policy makers is that

direct and persistent engagement is required to hold their atten-

tion, particularly on new ideas that may initially appear as yet

another demand.

Effective political engagement is a critical success factor in a

number of areas where assistive technology is salient – health,

education, employment. To be realistic about developing policy

on assistive technology systems, it is likely that a country will

need several assistive technology leaders, or champions, who can

understand the political landscape in which they work, translate

technical content into compelling material to engage politicians,

network and interact with key stakeholders; in short, to become

policy entrepreneurs. Some elements of this work will require

such advocates to be supported by, or undertake, a detailed polit-

ical economy analysis of factors likely to propel change in the

desired direction, and those likely to impede it.

Conclusions

This position paper demonstrates the complexity involved when

generating policy towards sustainable assistive technology provi-

sion. States that have ratified the CRPD have reporting obligations

to the CRPD Committee, to outline just how they are planning to

do this. While the general ethos of the Convention is supportive

of assistive technology, it is nonetheless rather vague (e.g., see

[9]). Currently, many States that have reported have not made ref-

erence to assistive technology within their reports [68]. We feel

the development of, and adoption of, a General Comment on

Assistive Technology (i.e., a statement additional and complimen-

tary to the CRPD) would be very helpful in both the development

of National Assistive Technology Policies, and in guiding the

Committee on how to most constructively respond to States

reports submitted to it, especially regarding those sections per-

taining to assistive technology, or indeed the absence of

such reporting.

Among other things assistive technology policy should pro-

mote ageing from a life course perspective, the need for popula-

tion level data, reducing rehabilitation silo-ing, promoting inter-

sectoralism and intersectionality, the need for more low-tech

assistive technology, universal and environmental access, the insti-

tutionalization of disruption, and the scaling of good practices. It

should also value evidence-informed as opposed to evidence-

based policy.

Work is currently underway on the development of a

Framework to guide and evaluate assistive technology policy; and

many of the ideas in this paper will inform that framework. We

need to evaluate – both quantitatively and qualitatively – the

extent to which policies, strategies and action plans related to AT,

incorporate principles of human rights and enable equitable

access in practice. This calls for analysis of policy “on the books”

where it does exist, the process of policy making, it implementa-

tion, and the documentation of the lived experiences of persons