THE RISE OF NONBINDING INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS:

AN EMPIRICAL, COMPARATIVE, AND NORMATIVE ANALYSIS

Curtis A. Bradley,

*

Jack Goldsmith

**

& Oona A. Hathaway

***

The Article II treaty process has been dying a slow death for decades,

replaced by various forms of “executive agreements.” What is only beginning to be

appreciated is the extent to which both treaties and executive agreements are

increasingly being overshadowed by another form of international cooperation:

nonbinding international agreements. Not only have nonbinding agreements become

more prevalent, but many of the most consequential (and often controversial) U.S.

international agreements in recent years have been concluded in whole or in

significant part as nonbinding international agreements. Despite their prevalence

and importance, nonbinding international agreements are not currently subject to

any of the domestic statutory or regulatory requirements that apply to binding

agreements. As a result, they are not centrally monitored or collected within the

executive branch, and they are not systematically reported to Congress or disclosed

to the public.

This Article focuses on three of the most important types of nonbinding

international agreements concluded by the United States: (1) high-level formal

agreements; (2) joint statements and communiques; and (3) nonbinding agreements

concluded by administrative agencies. After describing these categories and their

history, the Article presents the first empirical study of U.S. nonbinding agreements,

*

Allen M. Singer Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School.

**

Learned Hand Professor, Harvard Law School.

***

Gerard C. and Bernice Latrobe Smith Professor of International Law, Yale Law School.

For excellent research assistance, we thank Josh Asabor, Tilly Brooks, Patrick Byxbee,

Yilin Chen, Ben Daus-Haberle, Eliane Holmlund, Simon Jerome, Tori Keller, Madison Phillips,

Annabel Remudo, Nathan Stull, Danielle Tyukody, and Kaylee Walsh. We also thank Ayoub

Ouederni for his outstanding assistance analyzing and presenting the data. We thank the many

scholars, lawyers, and government officials from around the world who provided us with insights into

the process for making nonbinding agreements. For assistance with the FOIA requests to more than

twenty federal agencies and lawsuits against the Departments of State, Defense, and Homeland

Security, we thank Daniel Betancourt, Jackson Busch, Charles Crain, Roman Leal, Abby Lemert,

David Schultz, Sruthi Venkatachalam, Kataeya Wooten, Brianna Yates, and especially Michael

Linhorst of the Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic at Yale Law School. For helpful

comments and suggestions, we thank Helmut Aust, Jean Galbraith, Duncan Hollis, Thomas

Kleinlein, Tim Meyer, Kal Raustiala, Michael Reisman, Ryan Scoville, David Zaring, and

participants in faculty workshops at the University of Chicago Law School and Yale Law

School.

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

2

drawing on two new databases that together include more than 2100 nonbinding

agreements. Based on this study, the Article argues that many of the concerns that

prompted Congress to regulate binding executive agreements starting in the 1970s

also apply to nonbinding agreements. Finally, drawing in part on insights obtained

from a comparative assessment of the practices and reform discussions taking place

in other countries, the Article suggests legal changes designed to enhance

coordination and accountability.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 3

I. NONBINDING INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS IN U.S. LAW AND PRACTICE ... 9

A. What is a Nonbinding International Agreement? ....................................... 9

B. Nonbinding International Agreements in U.S. Law ................................. 12

C. The Modern Forms of Nonbinding International Agreements ................. 21

II. AGENCY NONBINDING AGREEMENTS: AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS ................ 29

A. Why Agencies Conclude Nonbinding Agreements ................................. 29

B. Analyzing Agency Nonbinding Agreements ........................................... 36

III. A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE ......................................................................... 50

A. The Global Rise of Nonbinding Agreements ........................................... 50

B. Coordination ............................................................................................. 53

C. Transparency ............................................................................................ 56

D. Legislative Participation ........................................................................... 58

E. Summary .................................................................................................. 60

IV. LEGAL REFORM ................................................................................................... 61

A. Nonbinding Agreements and Domestic Delegation ................................. 62

B. Accountability Issues: Coordination, Reporting, Transparency .............. 63

C. International Best Practices ...................................................................... 75

CONCLUSION .............................................................................................................. 77

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

3

INTRODUCTION

The only process specified in the Constitution for making international

agreements is the one set forth in Article II, which requires that presidents obtain the

advice and consent of two-thirds of the Senators present.

1

This treaty process,

however, has been dying a slow death for decades.

2

It has been replaced in part by

various forms of “executive agreements” that are authorized by a statute, a prior

treaty, or the president’s independent constitutional authority.

3

Executive

agreements, like treaties, are binding under international law. While executive

agreements are increasingly used as substitutes for treaties, their numbers too have

declined in recent years.

4

As treaties and executive agreements have declined, another form of

international cooperation has grown in prominence: nonbinding international

agreements. A nonbinding international agreement is an agreement between two or

more sovereign states, or between a state and an international organization, that is

not governed by international law. Whether an agreement is “binding” or not

determines whether it triggers a range of formal rules under international law,

including rules relating to compliance and state responsibility for breach. This is

why international lawyers sharply distinguish the two categories. Yet because the

international legal system often lacks centralized adjudication or enforcement, in

practice nonbinding agreements operate in ways functionally similar to many

binding agreements—that is, they rely on informal enforcement mechanisms such as

coordination, reciprocity, and reputation.

1

See U.S. CONST. art. II, § 2.

2

See Oona A. Hathaway, Curtis A. Bradley & Jack L. Goldsmith, The Failed Transparency

Regime for Executive Agreements: An Empirical and Normative Analysis, 134 HARV. L. REV. 629,

632 (2020) (noting that the Clinton administration submitted approximately 23 treaties per year, the

George W. Bush administration submitted around twelve per year, the Obama administration

submitted around five per year, and the Trump administration submitted only five treaties in Trump’s

first three and a half years in office). In the first year of his presidency, President Biden submitted one

treaty to the Senate—the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the

Ozone Layer. That year, the Senate consented to no treaties.

3

See, e.g., Oona A. Hathaway, Presidential Power Over International Law, 119 YALE L.J.

140 (2009) (documenting “a little noticed transformation during the last half-century in the way

international law is made in the United States” from Article II treaties to executive agreements).

4

President Bill Clinton made an average of 257 executive agreements per year, President

George W. Bush 230 per year, and President Barack Obama 148 per year. President Donald Trump

concluded just 68 from when he took office until February 2018. See Jeffrey S. Peake, The Decline of

Treaties? Obama, Trump, and the Politics of International Agreements 40 tbl.1 (Apr. 6, 2018)

(unpublished manuscript).

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

4

It is difficult to overstate how important nonbinding agreements have become

to U.S. foreign policy. Almost all of the most consequential (and often

controversial) international agreements made by the last three presidential

administrations were nonbinding.

5

Recent examples of U.S. nonbinding agreements

include the EECD/G20 agreement on global tax reform; the Glasgow Climate Pact

among almost 200 nations that aims to reduce fossil fuel emissions; the Artemis

Accords, an eight-nation framework for interpreting and implementing provisions of

the binding Outer Space Treaty; the New Atlantic Charter, a United States-United

Kingdom agreement for promoting democratic values and institutions; and the

agreement between the United States and the Taliban concerning the withdrawal of

U.S. forces from Afghanistan, which President Biden controversially implemented in

August 2021. These high-profile agreements are the tip of the iceberg of a vast

agreement-making practice that largely flies under the radar of public and

congressional scrutiny.

6

The executive branch has many incentives to make agreements nonbinding

rather than binding. In contrast to Article II treaties and executive agreements that

are authorized by statute, the executive branch can make nonbinding international

agreements without the need to obtain congressional authorization or approval.

7

And

in contrast to executive agreements, which most commentators believe are limited to

matters that relate to the president’s independent constitutional authority, the

executive branch maintains that it can make nonbinding agreements on practically

any topic.

8

Nonbinding agreements also permit the executive branch to avoid

accountability and transparency mandates. The executive branch has a legal duty to

5

See infra Section I.C.

6

See infra Part II.

7

In responding to a question from a member of Congress about why the Obama

Administration did not use the Article II treaty process when concluding an important nuclear

agreement with Iran, Secretary of State John Kerry explained, “I spent quite a few years trying to get

a lot of treaties through the United States Senate and quite frankly, it has become physically

impossible. That is why. Because you can’t pass a treaty anymore.” Secretary of State John Kerry,

Testimony Before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House Foreign Affairs Committee (July 28,

2015), https://www.c-span.org/video/?327359-1/secretaries-kerry-moniz-lew-testimony-iran-nuclear-

agreement.

8

By contrast, under most accounts, the president’s constitutional authority to conclude

binding executive agreements (a) must be tied to an independent presidential authority, (b) is narrower

than the power to enter into Article II treaties and congressional-executive agreements, and (c)

generally encompasses discrete issues such as the recognition of other governments and the settlement

of claims. See Hathaway, Bradley & Goldsmith, supra note 2, at 639-41; see also, e.g., Medellin v.

Texas, 552 U.S. 491, 532 (2008) (referring to “the Executive’s narrow and strictly limited authority to

settle international claims disputes pursuant to an executive agreement”). For a broader view of the

president’s independent authority, see Harold Hongju Koh, Twenty-First-Century International

Lawmaking, 101 GEO. L.J. ONLINE 1 (2012).

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

5

report to Congress all binding agreements other than Article II treaties and to publish

the important ones.

9

But it can skirt these duties altogether by making a nonbinding

agreement, which it need not report or publish. In a world where foreign policy

challenges persist but Congress is gridlocked, it is no surprise that the executive

branch is drawn to a form of agreement that it can make on any topic, and without

congressional approval or accountability.

By all indications, the executive branch’s use of nonbinding agreements has

been growing for some time. In 2005, amidst the decline in binding agreements, a

lawyer in the State Department Legal Adviser’s Office observed that nonbinding

agreements had shown a “marked increase.”

10

As this Article documents, that trend

has accelerated since that observation. Moreover, many other countries have

witnessed a similar shift from binding to nonbinding arrangements.

11

For example,

the legal adviser to Germany’s Federal Foreign Office has noted that “[a]s seemingly

everywhere else, the significance of non-legally binding agreements has consistently

been rising in our practice.”

12

And the head of the treaty division of Mexico’s

foreign ministry has reported that approximately 70% of Mexico’s international

agreements are now nonbinding.

13

Previous U.S. scholarship has highlighted the growing phenomenon of

nonbinding international agreements. In 1977, in the wake of the nonbinding

Helsinki Accords, Oscar Schachter wrote a brief comment analyzing the “twilight

existence” of such nonbinding international agreements.

14

In 2002, Kal Raustiala

observed that agencies were using non-legally binding “Memoranda of

Understanding” to structure “transgovernmental cooperation.”

15

In 2009, Duncan

9

See Hathaway, Bradley & Goldsmith, supra note 2, at 645-51.

10

Robert E. Dalton, National Treaty Law and Practice: United States, in NATIONAL TREATY

LAW AND PRACTICE: DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF MONROE LEIGH 765, 767 (Duncan B. Hollis et

al. eds., 2005).

11

This finding is the result of a survey we conducted of experts and officials from more than

a dozen countries, as well as publicly available materials relating to a number of other countries.

12

Christophe Eick, Legal Adviser, German Federal Foreign Office, Welcome and Opening

Remarks, https://rm.coe.int/0-1-c-eick-cahdi-ws-opening-remarks/1680a23543.

13

See Alejandro Rodiles, ITAM School of Law, Mexico, Survey for University of Chicago

Law School Conference on “Non-Binding International Agreements: A Comparative Assessment”

(submitted Sept. 1, 2021) (on file with authors).

14

See Oscar Schachter, Editorial Comment: The Twilight Existence of Nonbinding

International Agreements, 71 AM. J. INT’L L. 296 (1977).

15

Kal Raustiala, The Architecture of International Agreements, 43 VA. J. INT’L L. 1, 22-23

(2002). See also Kal Raustiala & David G. Victor, Conclusion, in THE IMPLEMENTATION AND

EFFECTIVENESS OF INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL COMMITMENTS (David G. Victor, Kal Raustiala

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

6

Hollis and Joshua Newcomer emphasized the importance of nonbinding agreements

(which they called “political commitments”) in U.S. practice, provided a taxonomy

of these agreements, and considered their constitutional implications.

16

In 2012,

Harold Koh explained how nonbinding agreements operated in conjunction with

binding instruments to effectuate “layered diplomacy” in U.S. practice.

17

And in

2014, Jean Galbraith and David Zaring offered a foreign relations law perspective on

nonbinding agreements concluded by administrative agencies (which they called

“soft law agreements”).

18

These studies provide a valuable starting point for understanding nonbinding

agreements. But none seeks to discern the extent and nature of the U.S. practice of

concluding nonbinding agreements. Nonbinding agreements are extraordinarily

difficult to study because they operate in a law-free zone—no international or

domestic legal rules govern them—and because the systems that track international

agreements do not include nonbinding agreements. Article II treaties are published

by the Senate,

19

listed in the Treaties in Force compilation prepared by the State

Department,

20

and registered with the United Nations;

21

executive agreements are

collected by the State Department and reported to Congress under the Case-Zablocki

Act,

22

and are published in both public and private databases.

23

Nonbinding

& Eugene B. Skolnikoff, eds., 1998) (advocating the use of nonbinding agreements in international

environmental cooperation).

16

See Duncan B. Hollis & Joshua J. Newcomer, “Political” Commitments and the

Constitution, 49 VA. J. INT’L L. 507 (2009).

17

Koh, supra note 8, at 14.

18

See Jean Galbraith & David Zaring, Soft Law as Foreign Relations Law, 99 CORNELL L.

REV. 735 (2014). A related literature explores the reasons why nations might conclude nonbinding

agreements (sometimes characterized as “informal” or “soft law” commitments) rather than binding

ones. See, e.g., Anthony Aust, The Theory and Practice of Informal International Instruments, 35

INT’L & COMP. L. Q. 787 (1986); Charles Lipson, Why are Some International Agreements Informal?,

45 INT’L ORG. 495 (1991); Gregory Shaffer & Mark A. Pollack, Hard and Soft Law: What Have We

Learned?, in INTERNATIONAL LAW AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: INSIGHTS FROM

INTERDISCIPLINARY SCHOLARSHIP (Jeffrey L. Duffoff & Mark A. Pollack, eds., 2012).

19

See Congress.gov (“About Treaty Documents”), https://www.congress.gov/search?

q=%7B%22source%22%3A%22treaties%22%7D.

20

U.S. Department of State, Treaties in Force, https://www.state.gov/treaties-in-force/.

21

United Nations Treaty Collection, https://treaties.un.org.

22

See 1 U.S.C. § 112b.

23

See KAV Agreements, HEINONLINE, https://home.heinonline.org/titles/World-Treaty-

Library/KAV-Agreements [https://perma.cc/P745-KWCP]; Treaties and Other International Acts

Series (TIAS), U.S. Dep’t of State, https://www.state.gov/tias [https://perma.cc/CFC8-BDSU]. We

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

7

agreements, by contrast, have no central repository and are not subject to any rules

about transparency or publication. Most nonbinding agreements are thus never made

public. And the ones available to the public are scattered across the internet based

on the varying preferences of the dozens of agencies and departments that make

them. Most other countries similarly fail to make their nonbinding agreements

public. This has made nonbinding agreements challenging to study.

To overcome these problems, we took three steps. First, we built the first-

ever database of the nonbinding agreements concluded by U.S. administrative

agencies. Working with a team of research assistants, we gathered all public

information we could obtain on such nonbinding agreements. We then filed

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests with more than twenty federal agencies

that we determined conclude nonbinding agreements, in order to obtain their

nonpublic records. When they failed to respond in a timely manner to our FOIA

request, we sued the Departments of State, Defense, and Homeland Security to

obtain their records of nonbinding agreements. In addition, we built a smaller (but

still substantial) database of a second form of nonbinding agreements—joint

statements and communiques issued following high-level international meetings or

conferences. These efforts have resulted in two databases that together already

include over 2100 nonbinding agreements that we have coded and analyzed to

provide an unprecedented quantitative empirical glimpse into the U.S. nonbinding

agreements practice.

24

Second, we interviewed government officials in several administrative

agencies about their experiences in connection with the drafting and conclusion of

nonbinding agreements. These interviews provided invaluable information about

why agencies choose to conclude nonbinding agreements and the processes that they

follow. Third, we reached out to experts and officials in other countries to learn

more about how their legal and regulatory systems address nonbinding international

agreements. This gave us a broader comparative perspective from which to view

U.S. practice than prior scholarship.

A key contribution of this Article, then, is to excavate and describe a growing

practice relating to international law. Nonbinding agreements, we show, are not just

an important part of the international agreement landscape; they are, increasingly, the

dominant part. The field of international law—in the United States and globally—

documented in earlier work that these databases are not complete, and we recommended reforms for

improving transparency. Still, the databases do exist. See Hathaway, Bradley & Goldsmith, supra

note 2.

24

We will continue to update a publicly available database on Dataverse that will include all

current agreements as well as additional agreements obtained through litigation or under FOIA.

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

8

must reorient itself to this new reality. Increasingly, international cooperation is

shaped by commitments that claim not to be law at all. This development has

important ramifications for how international law is taught and studied, both in the

United States and elsewhere, and it raises fundamental questions about the nature of

the international legal system.

The growing importance of nonbinding agreements also raises the question—

largely unaddressed in prior scholarship—about whether and how such agreements

should be regulated domestically.

25

In the United States, nonbinding agreements in

many cases serve the role once reserved for Article II treaties and binding executive

agreements. And yet they are entirely exempt from the reporting and publication

requirements that apply to binding agreements. As we will explain, in some ways

nonbinding agreements should be treated differently, in part to preserve the

flexibility that such agreements offer. With this in mind, and drawing upon ideas

being discussed in other countries, we recommend reforms to enhance executive

branch accountability and transparency.

Unlike many issues of government accountability and transparency,

legislative reform here is plausible. Congress has often amended the Case-Zablocki

Act since the 1970s, and pending legislation proposes to amend it yet again—in part

to address reform proposals that we made in an earlier article.

26

The proposed

legislation, if enacted, would also begin to address some nonbinding

agreements. The proposed legislation does not go far enough, but it shows that

Congress is interested in improving accountability and transparency in this context.

Part I of this Article describes the rise of nonbinding international agreements

in U.S. practice and their current lack of legal regulation. Part II presents a novel

empirical account of the nonbinding agreements concluded by U.S. administrative

agencies based on numerous sources. Part III is a comparative analysis of how other

nations are addressing the regulatory challenges presented by nonbinding

agreements. Building on Parts II and III, Part IV considers potential legal reforms

for the United States, with a particular focus on executive branch coordination and

public transparency. The Article concludes with reflections on the implications of

the rise of nonbinding international agreements for the field of international law.

25

We addressed this question briefly in prior work. See Hathaway, Bradley & Goldsmith,

supra note 2, at 708-10. See also Ryan Harrington, A Remedy for Congressional Exclusion from

Contemporary International Agreement Making, 118 W. VA. L. REV. 1211, 1236-42 (2016)

(discussing how the Case-Zablocki Act could be construed to apply to nonbinding agreements).

26

See infra note 224.

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

9

I. NONBINDING INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS IN U.S. LAW AND PRACTICE

A nonbinding international agreement can be bilateral or multilateral and can

take many forms.

27

A common element among all forms of these agreements is that

they are not governed by international law—a characteristic that has implications for

why nations make them and how they operate in practice. This Part provides

background on nonbinding agreements made by the United States to set the stage for

the empirical, comparative, and normative analysis that follows. It begins by

defining nonbinding agreements. It then explains the historical use of these

agreements by the United States and their place in the U.S. domestic legal system.

Finally, it examines contemporary U.S. practice concerning nonbinding agreements

and organizes the agreements into three categories for purposes of analysis.

A. What is a Nonbinding International Agreement?

A nonbinding international agreement can best be understood by comparison

to a binding international agreement, which in international law nomenclature is

called a “treaty.” A treaty is “an international agreement concluded between States. .

. and governed by international law.”

28

Important legal consequences of a legally

binding treaty include pacta sunt servanda (a duty to observe the terms of the treaty),

state responsibility for violations, and legal remedies for breach, such as reparations

and countermeasures.

29

A nonbinding international agreement is simply an agreement between

nations that is not governed by international law.

30

Such an agreement imposes no

27

Different terms have been used to capture what we call “nonbinding international

agreements,” including “political commitments,” “informal agreements,” “informal arrangements,”

“nonbinding arrangements,” “nonbinding documents,” “nonbinding instruments,” “nonbinding

arrangements,” “soft law agreements,” and (in an earlier era) “gentlemen’s agreements.” See, e.g.,

ANTHONY AUST, MODERN TREATY LAW AND PRACTICE 18 (3d ed. 2013); Robert Dalton, Asst. Legal

Adviser for Treaty Affairs, International Documents of a Non-Legally Binding Character, State

Department, Memorandum (Mar. 18, 1994) (copy on file with authors). Although some observers

might think that the word “agreement” connotes bindingness, we use “nonbinding agreements”

because it best reflects the role that these documents play in the international system. The term has,

moreover, been used in recent international discussions of the topic. See infra Part III.

28

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, supra note 4, art. 2(1)(a) (emphasis added).

Under international law, all international agreements that are governed by international law, including

“executive agreements,” are considered treaties.

29

See, e.g., AUST, supra note 27, at 315-17.

30

It is also not governed by domestic law. States make contracts—for example with

corporations concerning investment matters and sometimes with other states—that are governed by

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

10

international legal duty to comply with its terms, and breach or non-compliance with

the agreement implicates no international legal consequences. This does not mean

that nonbinding agreements lack any relationship to binding international law. To

the contrary, nonbinding agreements can serve as the basis for or precursor to

binding instruments made later;

31

provide interpretive guidance for binding

agreements;

32

clarify or expand upon the requirements of binding obligations;

33

be

embedded or incorporated into a binding obligation or instrument;

34

and influence

the development of customary international law.

35

But nonbinding agreements do

not create direct legal obligations and the attendant consequences.

36

The difference between a binding and a nonbinding agreement is easy to

articulate in theory but distinguishing between the two in practice can be challenging

because there is no universally accepted test for drawing the distinction. One test

domestic law rather than international law. See Organization of American States, Inter-American

Juridical Committee, Guidelines on Binding and Non-Binding Agreements 55-56 (2020),

http://www.oas.org/en/sla/iajc/docs/Guidelines_on_Binding_and_NonBinding_Agreements_publicati

on.pdf [hereinafter OAS Report]. Nonbinding international agreements exclude such contracts.

31

For example, the 1988 Baltic Sea Ministerial Declaration and the 1992 Baltic Sea

Declaration “paved the way for the 1992 Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of

the Baltic Sea Area,” a binding agreement. Andreas Zimmermann & Nora Jauer, Possible Indirect

Legal Effects of Non-legally Binding Instruments, Expert Workshop on Non-Legally Binding

Agreements in International Law (Mar. 26, 2021), at https://rm.coe.int/1-2-zimmermann-indirect-

legal-effects-of-mous-statement/1680a23584.

32

For example, investment tribunals “rely on non-binding rules . . . to establish procedures

through which to adjudicate disputes in a binding fashion,” and in legally binding decisions the

tribunals sometimes use “non-binding instruments to fill gaps in international investment

agreements.” Tim Meyer, Alternatives to Treaty-Making—Informal Agreements, in THE OXFORD

GUIDE TO TREATIES 59, 64 (Duncan Hollis ed., 2d ed. 2020).

33

For example, “space-faring states have favored legally nonbinding principles and technical

guidelines that are layered on top of . . . preexisting treaties” related to outer space. Koh, supra note

8, at 15. Similarly, in the environmental context, “decisions of treaty bodies, such as a Conference of

the Parties (COP), are often non-binding but can supplement or expound on binding obligations.”

Meyer, supra note 32, at 64.

34

In differing ways, this was true of both the Paris Agreement on climate change and the Iran

nuclear deal. See infra text accompanying notes 96-102.

35

See International Law Commission, Draft conclusions on identification of customary

international law with commentaries (2018), A/73/10, Conclusions 6, 9, and 10. Some scholars claim

that a nonbinding commitment might bind a country under the principle of estoppel, but the point is

not established in national practice. See OAS Report, supra note 30, at 126.

36

See OAS Report, supra note 30, at 123 (noting that nonbinding agreements do not “trigger

pacta sunt servanda nor any of the secondary international legal effects that follow treaty-making

(e.g., the law of treaties, State responsibility, specialized regimes)”).

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

11

looks predominantly to the intent of the parties.

37

However, intent is not always easy

to discern. Some nonbinding agreements expressly state that they are nonbinding.

But many do not, in which case intent must be inferred from the language of the

agreement, the circumstances under which it was made, and other contextual

factors.

38

A second test turns on objective factors. On this view, “the agreement’s

subject-matter, text, and context determine its binding or non-binding status

independent of other evidence as to one or more of its authors’ intentions.”

39

The intent and objective tests often lead to the same conclusion about the

bindingness of an agreement. But uncertainties in the application of each test,

combined with the fact that different nations follow different tests, mean that nations

sometimes disagree about whether an agreement between them is binding or not.

Several prominent international tribunal cases involved disputes about whether

certain agreements were binding or not.

40

In the 1990s, the United States considered

certain defense-related memoranda of understanding to be binding agreements, but

its partners (Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom) regarded them as

nonbinding political commitments.

41

Similarly, the United States viewed the nuclear

deal with Iran in 2015 as a nonbinding agreement, but Iran insisted that it was a

37

The intent test was embraced by the International Law Commission in its important mid-

century study of the law of treaties, see, e.g., II Yearbook of the International Law Commission 189

(1966), and by the delegates to the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, U.N. Conference on

the Law of Treaties, Summary Records of Second Session, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.39/11, Add.1, 225,

13. It is the approach used by, among other countries, the United States, see Dalton, supra note 27,

and the United Kingdom, see AUST, supra note 29, at 31.

38

See, e.g., Dalton, supra note 27 (noting that the test for legal bindingness is “the intent of

the parties, as reflected in the language and context of the document, the circumstances of its

conclusion, and the explanations given by the parties”).

39

See OAS Report, supra note 30, at 80-81 and notes 127-134; Meyer, supra note 32, at 59.

40

See, e.g., Maritime delimitation and territorial questions between Qatar and Bahrain (Qatar

v. Bahrain), 1994 I.C.J. 112, ¶¶ 20–22 (Jurisdiction and Admissibility); Agean Sea Continental Shelf

Case (Greece v. Turk.), 1978 I.C.J. 3, ¶¶ 97–100 (Dec. 19); Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in

the Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh/Myanmar), Case No. 16, Judgement of Mar. 14, 2012, ITLOS Rep. 4,

¶¶ 61–69.

41

See John H. McNeill, International Agreements: Recent US-UK Practice Concerning the

Memorandum of Understanding, 88 AM. J. INT’L L. 821 (1994).

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

12

binding agreement.

42

And more recently, the United States and Mexico disagreed

about the bindingness of an agreement concerning migration.

43

The final definitional point is that, for our purposes, the fact that an

agreement is nonbinding does not necessarily mean that it is “soft law.” The two

concepts are sometimes used interchangeably, especially in scholarly discussions.

44

But soft law is often used as a broader term to capture agreements and international

policies that impose weak or uncertain obligations through some combination of

nonbindingness, vague or hortatory terms, shallow obligations, and a lack of

enforcement mechanisms.

45

For purposes of this Article, a nonbinding international

agreement is simply one that is not governed by international law, and it can include

agreements with vague or precise terms, shallow or deep obligations, and

enforcement mechanisms or no such mechanism.

B. Nonbinding International Agreements in U.S. Law

This section reviews how nonbinding agreements fit within the framework of

U.S. domestic law. It begins with a brief description of the history of such

agreements in the United States, and it then turns to the president’s domestic

42

See STEPHEN P. MULLIGAN, CONG. RESEARCH SERV., LSB10134, WITHDRAWAL FROM THE

IRAN NUCLEAR DEAL: LEGAL AUTHORITIES AND IMPLICATIONS 1 (2018) (stating the U.S. view); Eline

Gordts, Iran’s Foreign Minister to U.S. Senators: ‘The World is Not the United States’, HUFFINGTON

POST (Mar. 9, 2015), https://www.huffpost.com/entry/zarif-senators-letter_n_6834296 (explaining the

Iranian view).

43

See Joint Declaration and Supplementary Agreement Between the United States of

America and Mexico, Mex.-U.S., June 7, 2019, T.I.A.S. No. 19-607; Rachel Withers, Mexico

Releases the Full Text of Trump’s Immigration “Deal,” VOX, June 15, 2019,

https://www.vox.com/2019/6/15/18680129/us-mexico-immigration-deal-release-trump-tariff. In

response to a query from Senator Menendez, the State Department declared the agreement binding.

Letter from Mary Elizabeth Taylor, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Legislative Affairs, U.S.

Department of State, to Robert Menendez, Ranking Member, Committee on Foreign Relations,

United States Senate (Sept. 9, 2019). Yet, according to a U.S. government lawyer, “the Government

of Mexico considers it non-binding.” Email from U.S. Government Lawyer to Oona A. Hathaway

(June 5, 2021).

44

See, e.g., Andrew T. Guzman & Timothy L. Meyer, International Soft Law, 2 J. LEGAL

ANALYSIS 171, 201-21 (2010); see also Dinah L. Shelton, Soft Law, in ROUTLEDGE HANDBOOK OF

INTERNATIONAL LAW 68 (David Armstrong ed., 2008).

45

See Kal Raustiala, Form and Substance in International Agreements, 99 AM. J. INT’L L.

581 (2005); Kenneth W. Abbott & Duncan Snidal, Hard and Soft Law in International Governance,

54 INT’L ORG. 421, 422 (2000); W. Michael Reisman, The Concept and Functions of Soft Law in

International Politics, in 1 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF JUDGE TASLIM OLAWALE ELIAS 135 (Emmanuel G.

E & Prince Bola A. Ajibola, S.A.N. eds., 1992).

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

13

authority to make them, their status in the domestic legal system, and their lack of

domestic regulation.

1. A Brief History of Nonbinding Agreements. The history of nonbinding

international agreements in the United States is murky. Diplomatic letters and other

papers effectuated informal agreements with other nations since the Founding. But a

distinct category of what we today mean by nonbinding international agreements did

not clearly emerge until the twentieth century.

46

Before then, the executive branch

made hundreds of agreements on its own authority. But there appears to have been

little discussion of whether these agreements were binding or nonbinding under

international law.

The issue became more salient in the early twentieth century as the Senate

began to complain about the executive branch’s increasingly ambitious use of the

executive agreement power.

47

The executive branch defended some agreements on

the ground that they lasted only as long as the executive branch chose to enforce

them and did not bind future administrations or the nation as a whole. Theodore

Roosevelt invoked this theory to justify the 1905 agreement he made with the

Dominican Republic for administering customs houses in Santo Domingo.

48

William Howard Taft made a similar argument, when he was Roosevelt’s Secretary

of War, to justify an agreement that defined the relative jurisdictions in cities at both

ends of the Panama Canal.

49

Taft described the agreement as a modus vivendi (or

temporary agreement) that was “revocable at will,” but it lasted beyond the

Roosevelt administration because subsequent administrations continued to enforce

46

There were concepts akin to nonbinding agreements much earlier. See, e.g., EMER DE

VATTEL, THE LAW OF NATIONS 355 (Béla Kapossy & Richard Whatmore eds., Liberty Fund 2012)

(1797) (distinguishing a “personal alliance” or “personal treaty,” which “expires with him who

contracted it,” from a “real alliance” or “real treaty,” which “attaches to the body of the state, and

subsists as long as the state, unless the period of its duration has been limited”).

47

For example, the Senate reacted testily to President McKinley’s use of an executive

agreement to “arrange[] the Spanish withdrawal from Puerto Rico, Cuba, and other former

possessions” at the termination of the Spanish-American war, and to early twentieth century

presidents’ agreements establishing U.S. policy in the far east, including the Open Door Policy, the

intervention in the Boxer Rebellion, and several agreements with Japan. See Bruce Ackerman &

David Golove, Is NAFTA Constitutional?, 108 HARV. L. REV. 799, 818 (1995). See generally Michael

D. Ramsey, The Treaty and Its Rivals: Making International Agreements in U.S. Law and Practice, in

SUPREME LAW OF THE LAND? DEBATING THE CONTEMPORARY EFFECTS OF TREATIES WITHIN THE

LEGAL SYSTEM OF THE UNITED STATES (Paul Dubinsky, Gregory Fox & Brad Roth eds., 2017)

(describing “enormous changes in U.S. foreign relations” by end of nineteenth century that led to

“new forms of agreement-making,” including “the rise of nonbinding agreements”).

48

See THEODORE ROOSEVELT, THEODORE ROOSEVELT, AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY 551 (1913).

49

See WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT, OUR CHIEF MAGISTRATE AND HIS POWERS 112 (1916).

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

14

it.

50

Similarly, Secretary of State Robert Lansing explained that the 1917 Lansing-

Isgii agreement—which resolved various U.S.-Japan issues relating to China—

lacked “any binding force” on the United States, and was “simply a declaration of . .

. the policy of this Government, as long as the President and the State Department

want to continue that policy.”

51

Despite these early precedents, commentators in the first third of the

twentieth century disagreed about which of hundreds of other agreements made by

the executive branch were binding on the nation rather than simply a policy of a

particular administration. Quincy Wright’s influential 1922 book, The Control of

American Foreign Relations, argued that executive agreements that settled claims

and possibly agreements made under the Commander in Chief power were binding

on the nation under international law.

52

Wright maintained that other types of

executive agreements—which he variously labeled protocols, modus vivendi,

“gentlemen’s agreements,” administrative agreements, or agreements that define

executive policy—are “binding only on the president that makes them.”

53

He noted

that “presumably the foreign government would have no ground for objection if a

subsequent President discontinued such an executive agreement.”

54

Wright’s

assessment was influential, but other commentators reached different conclusions.

55

50

Investigation of Panama Canal Matters: Hearing Before the S. Comm. on Interoceanic

Canals, 59th Cong. 2590 (1907) (cable of Secretary of War William Howard Taft to Secretary of

State John Hay); see also id. at 2741-42 (Senator Morgan noting that the jurisdictional boundaries are

“settled here temporarily and provisionally by a modus vivendi”).

51

Treaty of Peace with Germany: Hearing Before the S. Comm. on Foreign Rels., 66th

Cong. 219 (1919) (testimony of Secretary of State Robert Lansing). President Harding later described

the “so-called Lansing-Ishii agreement” as an “exchange of notes [that], in the nature of things, did

not constitute anything more than a declaration of Executive policy.” GREEN HAYWOOD

HACKWORTH, 5 DIGEST OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 431 (1943). President Wilson said it was “an

understanding,” not an agreement.

52

QUINCY WRIGHT, THE CONTROL OF AMERICAN FOREIGN RELATIONS 240-44 (1922).

53

Id. at 238; see also id. at 54, 235, 237, 243. It appears from context in these passages that

Wright was not using the term “binding” to suggest that international law governed these agreements,

but rather to suggest that whatever political or moral obligation they imposed applied only to the

administration that made them.

54

Id. at 238.

55

See, e.g., GEORGE SUTHERLAND, CONSTITUTIONAL POWER AND WORLD AFFAIRS 120-21

(1919) (distinguishing executive agreements binding on the nation from those that “constitute[e] only

a moral obligation”); CHARLES HENRY BUTLER, TREATY-MAKING POWER OF THE UNITED STATES §

463 (1902) (concluding that “protocols,” Butler’s term for many executive agreements, “are binding

in a moral sense upon the Executive department of the administration making them,” but do not bind

the legislature, and “[i]t is doubtful if they are binding even morally upon any administration other

than that which entered into them”); Harry Swain Todd, The President’s Power to Make International

Agreements, 11 CONST. REV. 160, 162 (1927) (noting that the “question as to the binding force of an

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

15

The wide range of positions was possible because the executive branch was rarely

clear, beyond the few precedents mentioned above, about which agreements were

binding on the nation. The U.S. Supreme Court never addressed the issue.

56

The meaning and scope of nonbinding international agreements within U.S.

practice began to clarify in the middle decades of the twentieth century. The

increased use and importance of executive agreements starting in the 1930s sparked

a scholarly debate that highlighted the massive number and array of agreements

made on the President’s authority alone and raised anew questions about which were

binding.

57

In the 1940s, Presidents Roosevelt and Truman announced the Atlantic

Charter and the Yalta and Potsdam agreements (concerning aims and principles

relating to World War II and its aftermath) on their own authority. The United States

claimed that all three were nonbinding under international law, but some countries

and scholars disagreed about the latter two.

58

In 1949, the International Law

Commission began work on the law of treaties that would result in 1969 in the

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. That Convention’s definition of a treaty

as “an international agreement . . . governed by international law” aimed to exclude

nonbinding international agreements.

59

The question of which U.S. international agreements were binding and which

were nonbinding assumed new importance with the passage of the Case-Zablocki

Act in 1972. That Act required the Secretary of State to transmit to Congress “the

executive agreement is not easy to discuss” and is “not entirely settled in the minds of jurists”);

Charles Cheney Hyde, Agreements of the United States Other Than Treaties, in 17 GREEN BAG 229

(1905) (an agreement made by or at direction of the president “is in most cases a binding one upon the

nation.”); John W. Foster, The Treaty-Making Power Under the Constitution, 11 YALE L.J. 69, 79

(1901) (concluding that that “there are certain acts of an international character, binding the

Government, which the President may perform without the interposition of the Senate”).

56

The closest case we have found is United States ex rel Angarica v. Bayard, 127 U.S. 251,

261 (1888), where the Court assumed that an exchange of letters between the Secretary of State and

the Mexican equivalent was not binding on successors.

57

Compare Myres S. McDougal & Asher Lans, Treaties and Congressional-Executive or

Presidential Agreements: Interchangeable Instruments of National Policy: I, 54 YALE L.J. 181, 197-

99, 198 nn.15 & 17, 318-23 (1945) (maintaining that with a few exceptions, all executive agreements

are presumptively binding on the United States under international law), with Edwin Borchard, Shall

the Executive Agreement Replace the Treaty?, 53 YALE L.J. 664, 678-80 (1944) (suggesting that most

executive agreements bind only the administration that makes them). This debate was also influenced

by the Supreme Court’s decisions in United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203 (1942) and United States v.

Belmont, 301 U.S. 324 (1937), which made clear that some sole executive agreements could be

binding and supreme federal law.

58

See Schachter, supra note 14, at 297-98 & nn.10-11 (collecting sources).

59

See Fritz Münch, Comments on the 1968 Draft Convention on the Law of Treaties: Non-

Binding Agreements, 29 ZAÖRV 1 (1969); Schachter, supra note 14; Dalton, supra note 27.

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

16

text of any international agreement . . . other than a treaty, to which the United States

is a party.”

60

Disagreement immediately arose about what types of agreements were

included within this obligation. In 1976, the Legal Adviser to the State Department

established a five-part test for resolving this issue, the “central requirement” of

which was whether the parties to the agreement intended it to be binding under

international law.

61

These criteria were reflected in federal regulations beginning in

1981.

62

At least since that time, party intent has been the primary touchstone in U.S.

practice in determining whether an agreement is binding or nonbinding under

international law.

63

The State Department has issued modest guidance about

“formal, stylistic, and linguistic features” that an agreement should include and

exclude to ensure that it is nonbinding.

64

But the executive branch has never

explained in a comprehensive way which executive agreements are binding and

which are nonbinding.

2. Domestic Authorization to Make Nonbinding Agreements. In practice the

executive branch appears to assert the authority to make nonbinding agreements with

other countries on practically any topic. While few observers in modern times have

questioned this practice,

65

there is no settled account of the constitutional basis for it.

The text of the Constitution does not speak directly to the issue, and neither the

Supreme Court nor the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel has addressed

it.

60

1 U.S.C § 112b(a).

61

Foreign Relations Authorization Act: Hearing on S. 1190 Before the Subcomm. on Int’l

Operations of the S. Comm. on Foreign Rels., 95th Cong. 294 (1977) (memorandum by Legal Adviser

of Dep’t of State Monroe Leigh to key department personnel) [hereinafter Leigh Memorandum]. The

secondary requirements were significance, specificity, two or more parties, and form. Id. at 293-94.

62

The regulations were promulgated pursuant to a 1979 amendment to the Case-Zablocki

Act and are codified today at 22 C.F.R. § 181.2(a)(1).

63

See Dalton, supra note 27 (providing examples from the 1970s and 1980s).

64

See U.S. Department of State, Guidance on Non-Binding Documents, https://2009-

2017.state.gov/s/l/treaty/guidance/index.htm [hereinafter State Department Guidance]. To take one of

several examples, the guidance states that “we advise that negotiators avoid terms such as ‘shall’,

‘agree’, or ‘undertake’ [in nonbinding agreements, and] “we have urged that terms such as ‘should’ or

‘intend to’ or ‘expect to’ be utilized in a non-binding document.”

65

Hollis & Newcomer, supra note 16, make normative arguments against the conventional

wisdom, see id. at 575, as does (briefly) Michael D. Ramsey, Executive Agreements and the

(Non)treaty Power, 77 N.C. L. REV. 133, 143 (1998). But see Michael D. Ramsey, Evading the

Treaty Power?: The Constitutionality of Nonbinding Agreements, 11 FIU L. REV. 371, 375-76 (2016)

(concluding that the “Constitution’s text and practice thus appear to allow Presidents to make

nonbinding agreements” but adding that “the President has a constitutional obligation to assure that a

purportedly nonbinding agreement is clearly and unequivocally nonbinding under international law”).

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

17

The chief constitutional foundation for nonbinding agreements is the

president’s power to conduct the nation’s diplomatic relations and to speak on behalf

of the United States in the conduct of these relations.

66

This power derives in part

from the president’s textual authority (notably with Senate consent) to “make

Treaties” and to “appoint Ambassadors . . . and Consuls,” from the president’s power

to “receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers,” from the president’s status as

chief executive, and, sometimes, from the president’s duty to “take care to faithfully

execute the Law.”

67

The power has also been recognized in practice since the

Founding and flows from what Professor Louis Henkin described as the president’s

“control of the foreign relations ‘apparatus’”—the diplomatic machinery that

includes the State Department and other executive departments, U.S. ambassadors,

consuls, and ministers, and the president’s personal agents.

68

These sources of

authority—the implications of constitutional text, longstanding historical practice,

and control over the diplomatic machinery—provide the foundation for a number of

the president’s most important foreign relations powers.

69

The power to make

nonbinding international agreements is arguably best understood to flow from these

sources as well.

One way to view a nonbinding agreement is as a statement of U.S. foreign

policy, in coordination with other governments, that any party can opt out of

unilaterally. Viewed this way, the power to make such agreements falls within the

president’s power to announce U.S. foreign policy positions. Indeed, some

nonbinding international agreements might be viewed as a form of diplomatic speech

between the United States and foreign governments about how the parties intend to

act on matters that they have competence to execute. Such speech occurs countless

times every day in numerous contexts and in manifold forms. The president and his

or her subordinates could not exercise their diplomatic powers or meet their

66

See, e.g., Zivotofsky v. Kerry, 576 U.S. 1, 21 (2015) (president has “a unique role in

communicating with foreign governments”); United States v. Louisiana, 363 U.S. 1, 35 (1960)

(president is “the constitutional representative of the United States in its dealings with foreign

nations”).

67

U.S. CONST. art. II, § 1, cl. 1; id., art. II, § 2, cl. 2; id., art. II, § 3; Constitutionality of

Section 7054 of the Fiscal Year 2009 Foreign Appropriations Act, 33 Op. O.L.C., 2009 WL 2810454

(June 1, 2009) (describing various sources for the President’s authority to conduct diplomatic

relations).

68

LOUIS HENKIN, FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION 41 (2d ed.

1996). A fourth possible basis is the Article II Vesting Clause. See Ramsey, Evading the Treaty

Power, supra note 65.

69

These powers include the power to announce U.S. foreign policy positions, to state the

U.S. interpretation of rules of customary international law, to assert rights on behalf of the nation and

its citizens and to claim reparations, and to recognize foreign governments and their territories. See

HENKIN, supra note 68, at 41-45.

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

18

diplomatic responsibilities without communication of this sort. This communication

can be highly informal and unimportant (such as an email agreeing to meet to discuss

a small matter). It can be more formal and more important, such as a joint

communique stating common positions and aims on certain policy issues. And, at

the opposite end of the spectrum from the casual email, it can be a formal,

complicated, and important but nonetheless nonbinding agreement signed by heads

of state. The entire spectrum is encompassed by the president’s power over

diplomatic communications for the United States.

70

3. Nonbinding Agreements and Domestic Law. Nonbinding agreements do

not have the status of domestic federal law. They are by definition not “law.” And

they do not fit within the instruments identified in the Supremacy Clause—the

Constitution, treaties, or “laws of the United States . . . made in pursuance” of the

Constitution.

71

The Supreme Court has recognized that some “sole” executive

agreements operate as federal law that preempts state law.

72

But these decisions to

date have been limited to legally binding executive agreements.

73

And the Court has

emphasized, in the context of the president’s long-established power to settle claims

via executive agreement, that the power to make binding domestic law via executive

agreements is “narrow and strictly limited.”

74

The Court has also more generally

emphasized that the president in our system is not a lawmaker.

75

Given that the

scope of the president’s power to make nonbinding agreements is practically

limitless, it would be an unfathomable expansion of presidential power, and

disruption of the domestic legal system, if these instruments also had the status of

domestic law. These are some of the reasons why no one has ever seriously

suggested that nonbinding agreements have that status.

70

The president has sometimes even been described as the “sole organ of the federal

government in the field of international relations.” United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., 288

U.S. 378, 319 (1936). This description is now generally regarded as an overstatement. See Zivotofsky

v. Kerry, 135 S. Ct. 2076, 2090 (2015) (noting that “[i]t is not for the President alone to determine the

whole content of the Nation’s foreign policy”).

71

U.S. CONST. art. VI, cl. 2.

72

See United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203 (1942); United States v. Belmont, 301 U.S. 324

(1937).

73

For example, the Litvinov agreement that was at issue in both the Pink and Belmont

decisions was a binding sole executive agreement. See CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH LIBRARY,

TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS: THE ROLE OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE 88

(2001) [hereinafter CRS Study].

74

Medellín v. Texas, 552 U.S. 491 (2008).

75

See, e.g., Medellin v. Texas, 554 U.S. 759 (2008); Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v.

Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952).

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

19

Nonbinding agreements can, however, influence or become part of domestic

law. First, executive branch officials often implement or comply with nonbinding

agreements within the executive branch bureaucracy.

76

Second, Congress can

incorporate nonbinding agreements into binding domestic legislation. For example,

Congress in the Clean Diamond Trade Act implemented the Kimberley Process

Certification Scheme, a nonbinding agreement that aims to remove conflict

diamonds from the global supply chain.

77

Third, administrative agencies can through

rulemaking and other instruments implement nonbinding agreements domestically.

For example, the international banking rules reflected in the nonbinding Basel

Accords “are the basis for binding domestic regulations of the banking industry.”

78

Fourth, it is conceivable that some elements of nonbinding agreements might

preempt state law under the theory of executive branch foreign policy preemption

suggested in American Insurance Ass’n v. Garamendi.

79

4. Lack of Domestic Regulation. Another remarkable characteristic of

nonbinding international agreements is that, despite their prevalence and importance,

they are not currently subject to any of the statutory or regulatory requirements that

apply to binding agreements. Congress long ago imposed transparency and

accountability requirements on the executive branch with respect to binding

international agreements. Under the Case-Zablocki Act, the executive must report to

Congress “any international agreement . . . other than a treaty” within sixty days after

it takes effect.

80

There is also a statutory obligation to publish important agreements

76

See Hollis & Newcomer, supra note 16, at 542 (noting that “[o]fficials regularly conform

U.S. foreign policy to existing political commitments”); cf. Richard R. Baxter, International Law in

“Her Infinite Variety”, 29 INT’L L. & COMP. L.Q. 549, 556 (1980) (“Bureaucrats follow through on

what they have said that they would do through force of bureaucratic habit”).

77

See 19 U.S.C. §§ 3901 et seq.; Interlaken Declaration on Kimberley Process Certification

Scheme for Rough Diamonds (Nov. 5, 2002), at https://www.kpcivilsociety.org/wp-

content/uploads/2019/10/KP-InterlakenDeclaration-KPCS-1102.pdf. See also Mallory Stewart, Are

Treaties Always Necessary? How U.S. Domestic Law Can Give Teeth to Non-Binding International

Commitments, 2010 ASIL PROCEEDINGS 189.

78

Meyer, supra note 39, at 64; see also Galbraith & Zaring, supra note 22.

79

539 U.S. 396, 415 (2003). The Court held in Garamendi that the executive branch foreign

policy reflected in a legally binding sole executive agreement that called for the establishment of a

fund to compensate victims of Nazi persecution preempted a California state insurance recovery law.

Some commentators read Garamendi as recognizing an “independent presidential power to override

state laws that interfere with executive branch foreign policy.” Michael D. Ramsey & Brannon P.

Denning, American Insurance Association v. Garamendi and Executive Preemption in Foreign

Affairs, 46 WM. & MARY L. REV. 825 (2004) (emphasis added). If so, a court might conceivably

derive such a policy from a nonbinding agreement.

80

1 U.S.C. § 112b(a).

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

20

on the State Department’s website within 180 days after they take effect.

81

As we

have documented elsewhere, there are a number of deficiencies in this regime,

82

and

Congress is currently considering legislation that would bolster it.

Regulations adopted by the State Department to implement the requirements

make clear that they apply only if the parties to an agreement “intend their

undertaking to be legally binding, and not merely of political or personal effect.”

83

The regulations further state that “[d]ocuments intended to have political or moral

weight, but not intended to be legally binding, are not international agreements,” and

they give as an example the Helsinki Accords. More than twenty years ago, the

Congressional Research Service noted that “some believe these kinds of

[nonbinding] arrangements could represent a large loophole” in the reporting

regime.

84

Since then, the phenomenon of nonbinding agreements has grown

significantly.

Within the executive branch, the usual standards for approving and keeping

track of executive agreements do not apply to nonbinding agreements. The State

Department’s “C-175” process, named after a circular issued in 1955, is designed to

“facilitate[] the application of orderly and uniform measures to the negotiation,

conclusion, reporting, publication, and registration of U.S. treaties and international

agreements, and facilitate[] the maintenance of complete and accurate records on

such agreements.”

85

Pursuant to this process, before negotiating an agreement, an

executive agency must obtain pre-approval from the State Department.

86

After the

agreement is negotiated, the agency must receive additional C-175 approval from

State to conclude the agreement. Furthermore, after conclusion of the agreement, the

81

1 U.S.C. § 112a(d). For additional discussion of the reporting and publication obligations,

see Hathaway, Bradley & Goldsmith, supra note 2, at 645-54. Classified agreements are reported to

congressional committees but not published.

82

See generally id.

83

22 C.F.R. § 181.2(a)(1). Even before the adoption of the regulations, the State Department

had taken the position that the Case-Zablocki Act reporting obligation did not apply to nonbinding

agreements. See Schachter, supra note 14, at 302 (1977) (quoting from a memorandum by the State

Department Legal Adviser to “Key Department Personnel” dated March 12, 1976 on “Case Act

Procedures and Department of State Criteria for Deciding What Constitutes an International

Agreement”).

84

CRS Study, supra note 73, at 231.

85

11 U.S. Dep’t of State, Foreign Affairs Manual § 721,

https://fam.state.gov/fam/11fam/11fam0720.html.

86

Congress has similarly directed in the Case-Zablocki Act that “[n]otwithstanding any other

provision of law, an international agreement may not be signed or otherwise concluded on behalf of

the United States without prior consultation with the Secretary of State.” 1 U.S.C. § 112b(c).

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

21

agency is supposed to transmit a copy to State for central collection.

87

But this

centralized approval and collection process applies only to binding agreements.

88

In sum, even though nonbinding agreements can be as consequential as

binding agreements and often resemble them in form and enforcement, they are not

subject to any of the legal regulations that apply to binding agreements.

C. The Modern Forms of Nonbinding International Agreements

Nonbinding international agreements arise in a wide variety of institutional

settings and come in a wide variety of forms. A major challenge to analyzing them

is defining their scope. One cannot hope to be comprehensive, since nonbinding

agreements can include all manner of informal diplomatic communication, including

emails, phone calls, and everyday cables that foster relatively trivial forms of

international cooperation and coordination, including about lunch dates and future

communications.

For purposes of the analysis in this Article, we consider three of the most

consequential forms of nonbinding agreements: (1) high-level formal agreements; (2)

joint statements and communiques issued by state representatives; and (3)

nonbinding agreements between U.S. administrative agencies and their foreign

counterparts that promote various forms of international regulatory cooperation.

While these categories capture three distinctive types, there is variation within them,

the lines between them are not always sharp, and they leave out less formal and less

consequential forms of nonbinding agreements.

89

Nonetheless, these categories

provide a framework for understanding the main forms of nonbinding agreements

concluded by the United States.

1. High-Level Formal Agreements. The first category involves formal and

often elaborate agreements, usually about important matters agreed to by senior

governmental officials, that commit the nation (as opposed to an agency or other

subunit) to a course of action. These agreements often have many of the trappings of

87

See 22 C.F.R. § 181.3(b).

88

See State Dep’t, Office of the Legal Adviser, Circular 175 Procedure, https://2009-

2017.state.gov/s/l/treaty/c175/index.htm (“The Circular 175 procedure does not apply to documents

that are not binding under international law. Thus, statements of intent or documents of a political

nature not intended to be legally binding are not covered by the Circular 175 procedure.”); see also 22

C.F.R. § 181.4. If there is a question about whether an agreement is binding, agencies are supposed to

submit the agreement to State no later than twenty days after signing it for a determination. See 22

C.F.R. § 181.3(c). But it is unclear how this obligation is enforced.

89

For example, our three categories exclude oral agreements, exchanges of letters that do not

result in a joint text, and standard-setting rules of international organizations.

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

22

binding international agreements, such as content organized by articles, entry into

force and termination provisions, and sometimes even dispute resolution provisions.

But the parties nonetheless do not intend the agreements (or significant parts of the

agreements) to be binding under international law. They can be either bilateral or

multilateral.

While these types of nonbinding agreements have become more prevalent,

they are far from new. For example, the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which tempered

Cold War animosities between West and East and became a focal point for dissident

groups in the Soviet Union and its satellite nations that many believe were an

important cause of the fall of the Soviet Union, were nonbinding.

90

Recent examples

of important nonbinding high-level agreements include a multilateral agreement

known as the Artemis Accords that concerns the conditions for the safe and peaceful

exploration of space,

91

the OECD/G20 agreement on global tax reform,

92

and the

nonbinding agreement with the Taliban calling for the United States to withdraw all

forces by the end of May 1, 2021 (later extended to August 31).

93

This latter

agreement underscores the practical importance of nonbinding agreements even

though they are not enforceable under international law. President Biden explained

that the agreement protected U.S. persons during the withdrawal and emphasized that

if the United States missed the August 31 deadline, the Taliban likely would have

carried out attacks on U.S. troops.

94

90

See Daniel C. Thomas, The Helsinki Accords and Political Change in Eastern Europe, in

THE POWER OF HUMAN RIGHTS: INTERNATIONAL NORMS AND DOMESTIC CHANGE 205 (Thomas Risse

et al. eds., 1999). Relatedly, the Organization for Security and Co-operation (“OSCE”) in Europe,

“the world’s largest regional security organization,” grew out of the Helsinki Accords and is

constituted by nonbinding agreements. Who We Are, ORG. FOR SEC. AND COOP. IN EUR.,

https://www.osce.org/who-we-are (last visited July 31, 2021).

91

See The Artemis Accords (adopted Oct. 13, 2020), at https://www.nasa.gov/specials/

artemis-accords/img/Artemis-Accords-signed-13Oct2020.pdf.

92

Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the

Digitalisation of the Economy (July 1, 2021), https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-on-a-two-

pillar-solution-to-address-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-july-

2021.htm.

93

See Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan

Between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan Which is Not Recognized by the United States as a State

and is Known as the Taliban and the United States of America (Feb. 29, 2020), at

https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Agreement-For-Bringing-Peace-to-Afghanistan-

02.29.20.pdf.

94

Remarks by President Biden on the End of the War in Afghanistan, The White House

(Aug. 31, 2021), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/08/31/remarks-

by-president-biden-on-the-end-of-the-war-in-afghanistan/.

1-Feb-22] The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements

23

Two high-level agreements concluded during the Obama administration—the

Iran nuclear deal and the emissions reduction pledge in the Paris Agreement on

climate change—generated controversy.

95

These agreements provoked controversy

in part because of the novel mechanisms the executive branch used to circumvent the

need for congressional consent. Many commentators argued that both agreements

required congressional approval because they were so consequential and because

they could not be fully justified by prior congressional authorization. Congressional

consent was a high hurdle to the deals, however, because there was significant

opposition in Congress.

96

The agreements posed additional challenges because both

made pledges that required domestic implementation. The United States in the Paris

Agreement agreed to undertake economy-wide emission reduction targets, and in the

Iran deal it agreed to eliminate certain sanctions against Iran.

The Obama administration took two innovative steps in concluding these

agreements. First, it made the Iran deal and the emissions pledge in the Paris

Agreement nonbinding. This allowed the administration to conclude the agreements

without seeking congressional approval. Second, it changed domestic law to meet

the commitments in these agreements by invoking pre-existing authority delegated

from Congress. For the Iran deal, the administration exercised the power that

Congress had given it to waive the sanctions in accordance with the national

interest.

97

And for the Paris Agreement, it made new regulations pursuant to

authority granted earlier in several domestic statutes.

98

95

The Paris Agreement itself was a binding agreement that was likely made pursuant to a

prior treaty—the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). See Curtis

A. Bradley & Jack L. Goldsmith, Presidential Control Over International Law, 131 HARV. L. REV.

1201, 1267-69 (2018). However, while the UNFCCC plausibly authorized most portions of the Paris

Agreement, it likely did not authorize the president to pledge binding emissions targets. Id. at 1268-

69. The Obama administration insisted that the emissions reduction targets in Article 4.4 of the Paris

Agreement be made nonbinding, which avoided the need for congressional or Senatorial approval. Id.

at 1251 & n. 232, 1268-69.

96

Majorities in both houses of Congress voted against approval of the Iran deal but were

unable to stop the agreement from taking effect under the terms of the Iran Nuclear Agreement

Review Act. See Jennifer Steinhauer, Democrats Hand Victory to Obama on Pact with Iran, N.Y.

TIMES, Sept. 11, 2015, at A1. For evidence of congressional opposition to the Paris Agreement, see

David M. Herszenhorn, Votes in Congress Move to Undercut Climate Pledge, N.Y. TIMES (Dec. 1,

2015).

97

See Kenneth Katzman, Cong. Research Serv., Iran Sanctions (2021). In addition, the

agreement was the basis for, and incorporated by reference into, a U.N. Security Council resolution

that terminated the international sanctions against Iran. See U.S.S.C. Resolution 2231 (20 July 2015).

98

For an overview of the domestic regulations that supported the nonbinding commitment in

the Paris Agreement, see Cass R. Sunstein, Changing Climate Change, 2009–2016, 42 HARV. ENVT’L

L. REV. 231 (2018).

The Rise of Nonbinding International Agreements [1-Feb-22

24

2. Joint Statements and Communiques. A second category of nonbinding

agreements are statements issued following high-level international meetings or

conferences that memorialize what the national representatives agreed to, their

intended subsequent courses of action on matters of mutual concern, or their

common positions growing out of the meeting. We will refer to these statements as

“joint statements and communiques.”

99

We define this category as follows: Often after a meeting or conference, the

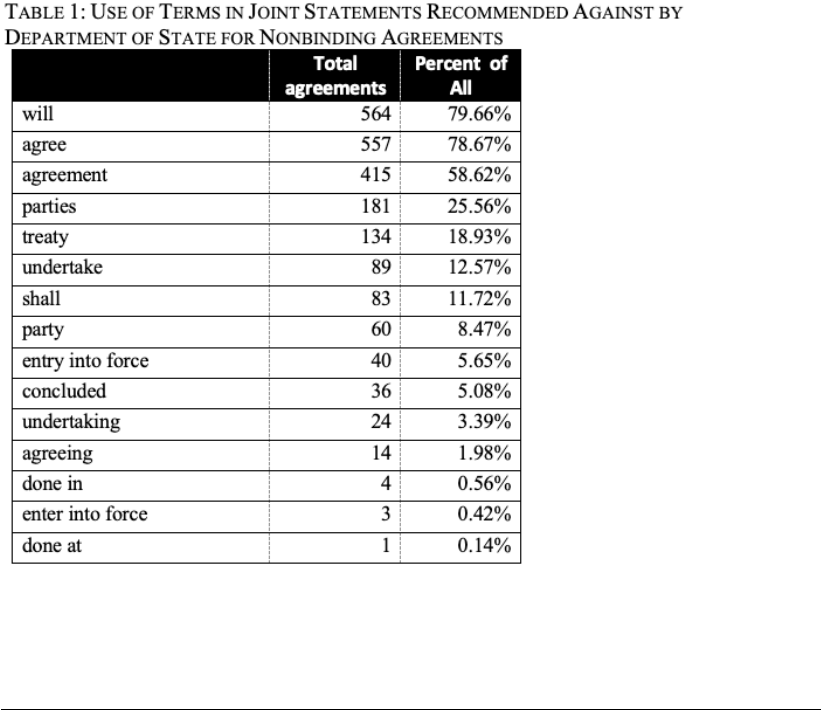

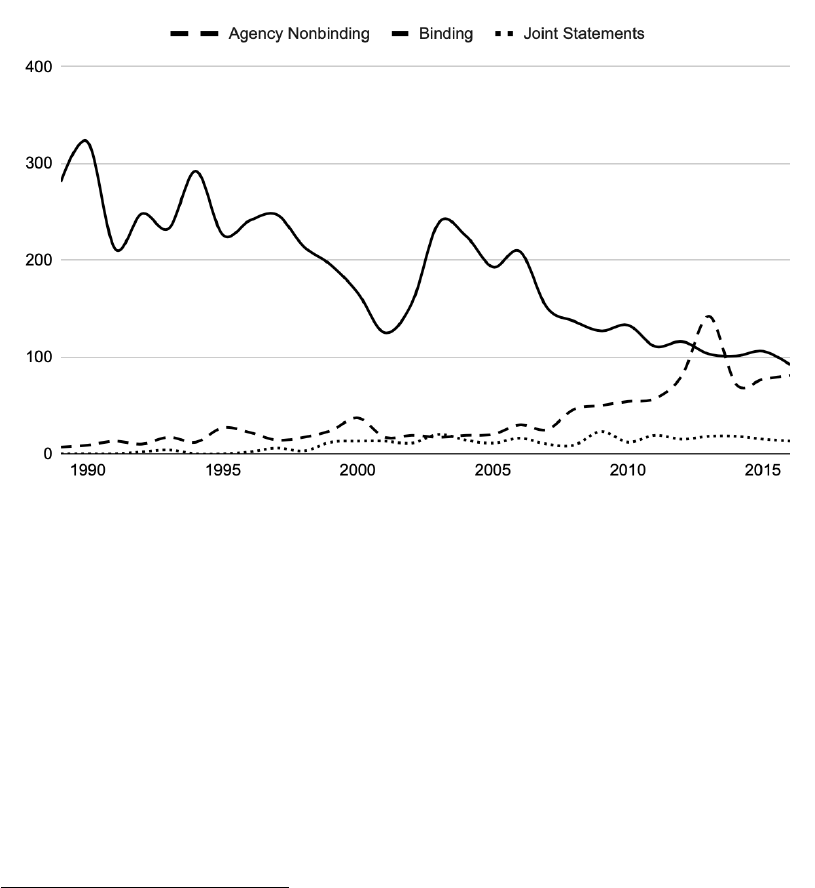

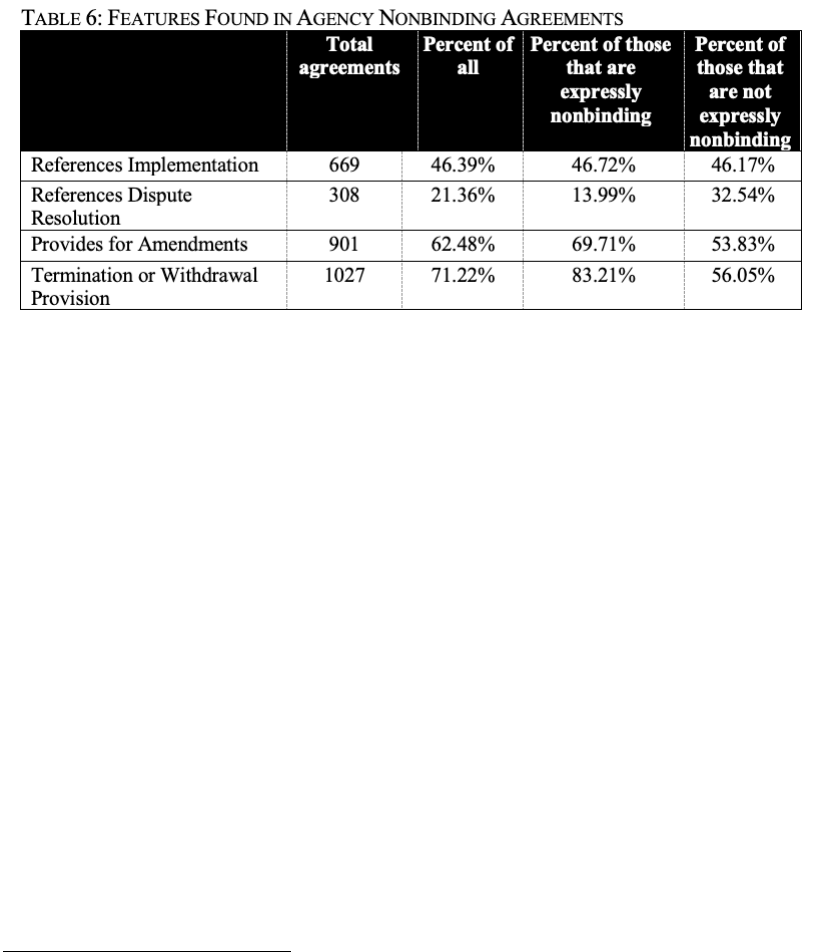

representatives of at least two sovereign states issue a joint text (that text may be