Public Opinion about Foreign Policy

Joshua D. Kertzer

1

Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, Third Edition, Eds. Leonie Huddy, David Sears, Jack

Levy, and Jennifer Jerit.

September 21, 2021

This chapter explores psychological approaches to the study of public opinion in foreign

policy. Traditionally the study of public opinion in IR was disconnected from work in

political psychology, but more recent work has sought to bridge the divide, at the same

time that work in IR and foreign policy is increasingly interested in microfoundations

more broadly. Topics covered include competing psychological models about the struc-

ture of foreign policy attitudes, the dynamics of public opinion towards the use of force

(including the democratic peace, audience cost models, rally around the flag effects,

against type models, and public attitudes towards nuclear weapons), and the origins of

public opinion on foreign economic issues like trade.

1 Introduction

Public opinion about foreign policy occupies a unique place in the study of political psychology.

Traditionally, the assumption was that public couldn’t be trusted to handle foreign policy: the pub-

lic was seen as being too uninformed and disconnected (Lippmann, 1955; Rosenau, 1961), moralistic

(Morgenthau, 1948; Kennan, 1951), and mercurial (Almond, 1950) to form well-structured views

about the world around it. If the public opinion occupied a marginal place in the study of inter-

national relations, it was because of a conventional wisdom that argued both that public opinion

didn’t shape foreign policy, and that public opinion shouldn’t shape foreign policy. Although more

optimistic readings of the public’s ability to respond meaningfully and systematically to world events

emerged — especially after the Vietnam and Gulf Wars (Mueller, 1973; Jentleson, 1992; Page and

Shapiro, 1992), it remained largely insulated from theoretical frameworks from political psychol-

ogy (Kertzer and Tingley, 2018). The study of political psychology in foreign policy was therefore

largely the study of political elites: their operational codes (Leites, 1951; George, 1969), belief sys-

tems (Holsti and Rosenau, 1979; Larson, 1985), personality traits and leadership styles (Greenstein,

1969; Etheredge, 1978; Hermann, 1980), perceptions and misperceptions (Jervis, 1976; Levy, 1983;

Stein, 1988), and so on. This is also reflected in how psychological approaches to the study of in-

ternational relations were incorporated into previous editions of the Oxford Handbook of Political

1

http:/people.fas.harvard.edu/˜jkertzer/

1

Psychology: the domain of elite decision-making, rather than mass political behavior (e.g. Levy,

2013; Herrmann, 2013; Stein, 2013).

Gradually, however, that conventional wisdom has shifted. Today there is a large and robust

literature on public opinion in foreign policy, increasingly influenced by the study of political psy-

chology. This shift has been driven by two trends: one theoretical, and another methodological.

The first is an increase in the number of theories in international relations that place the mass

public at the fore. Starting in the 1980s, IR scholars became increasingly interested in the extent to

which democracies conducted their foreign policies systematically differently than non-democracies

(Rummel, 1983; Doyle, 1986), in areas ranging from conflict (Maoz and Russett, 1993; Lake, 1992;

Gelpi and Griesdorf, 2001; Reiter and Stam, 2002), to cooperation (Martin, 2000; Jensen, 2003;

Milner and Kubota, 2005). One frequently posited explanation for democratic distinctiveness, espe-

cially in regard to war and crisis bargaining, had to do with the constraining effects of public opinion

(Fearon, 1994; Baum and Potter, 2015; Gelpi, 2017).

2

This turn to public opinion to provide mi-

crofoundations for our theoretical models in IR (Kertzer, 2017) has led to an increased demand for

scholarship seeking to better articulate the linkage between public opinion and foreign policy (Foyle,

1999; Oktay, 2018; Tomz, Weeks and Yarhi-Milo, 2020) and better understand how the public forms

judgments in foreign affairs.

This increase in demand as a result of theoretical changes in the discipline was also met by an

increase in supply as a result of methodological changes in the kinds of data available to test these

theoretical frameworks. Although notions of public opinion predate the development of large-scale

survey methods, for much of the second half of the twentieth century the latter came to represent the

former (Geer, 1996; Sanders, 1999; Igo, 2007). Since large-scale face-to-face and telephone surveys

of nationally representative samples were prohibitively costly, however, scholars of public opinion

on foreign policy often had to rely on secondary data — either polls fielded by polling firms like

Gallup or Pew, or large scale dedicated studies of public opinion towards foreign policy such as that

fielded by the then Chicago Council on Foreign Relations beginning in 1974, which were designed

more to provide a snapshot of public attitudes towards current events rather than test psychological

frameworks.

3

The rise of survey experiments administered to large-scale samples – first through

2

Though see Weeks (2014); Hyde and Saunders (2020).

3

There is also a rich tradition of lab experiments in foreign policy, but which originally tended to use mass samples

to model elite behavior, rather than being interested in the dynamics of public opinion about foreign policy in its own

right (e.g. Mintz and Geva, 1993; Beer et al., 1995; Herrmann et al., 1997; McDermott and Cowden, 2001; see Hyde

2015 for a review).

2

computer assisted telephone interviews (Sniderman, 2011), then multi-investigator online studies,

and finally diverse online samples at relatively low cost (Berinsky, Huber and Lenz, 2012) thus not

only reduced researchers’ barriers to entry, but also allowed scholars to incorporate longer batteries

of individual differences and dispositional traits into studies that were explicitly intended to test

psychological theories on large and diverse samples.

The literature on public opinion about foreign policy is now so vast that it is impossible to do

it justice in the confines of a short review essay, but the discussion that follows has three parts.

4

It begins with the puzzle of how the public expresses such strong views about foreign policy issues

even if they know relatively little about international politics, which political scientists have tried to

answer in two different ways, each of which borrows from a different quadrant of political psychology:

top-down models of public opinion, which understand the public as taking cues from political elites,

and bottom-up models of public opinion, which point to the role of individual differences such

as ideological orientations, core values, and images. Second, it turns to a series of attempts to

provide psychological microfoundations for a number of theoretical models in international security,

including the democratic peace, audience cost theory, rally around the flag effects, against type

models, and nuclear weapons. Third it turns to an area where there has traditionally been less work

in political psychology: public opinion towards foreign economic issues like trade, where researchers

have gradually discovered that material economic interests may play less of a role than classic

theories in political economy once assumed. It concludes by discussing directions for future research,

encouraging scholars to do more work to broaden the geographic scope of the evidence we use to

build and test our theories of public opinion in foreign policy.

4

Among the topics I lack the space to cover in any reasonable detail and thus sidestep here include: the evolving

role of the media in foreign policy (Nacos, Shapiro and Isernia, 2000; Robinson, 2001; Berinsky and Kinder, 2006;

Warren, 2014; Baum and Potter, 2019), the relationship between military casualties and public opinion (Mueller, 1971;

Gartner and Segura, 1998; Larson, 2000; Boettcher and Cobb, 2006; Voeten and Brewer, 2006; Gartner, 2008; Gelpi,

Feaver and Reifler, 2009; Kertzer, 2016), the relationship between public opinion and terrorism or political violence

(Kam and Kinder, 2007; Berrebi and Klor, 2008; Merolla and Zechmeister, 2009; Zeitzoff, 2014; Balcells and Torrats-

Espinosa, 2018; Huff and Kertzer, 2018; Littman, 2018; Nair and Vollhardt, 2019; Tellez, 2019; Gilbert, 2020), public

opinion about foreign policy as it relates to international law and cooperation (Brutger and Strezhnev, 2018; Kim,

2019; Lee and Prather, 2020; Dill and Schubiger, 2021; De Vries, Hobolt and Walter, 2021; Morse and Pratt, 2021),

and public opinion about a broader range of issues in foreign economic policy, such as aid, investment, globalization,

or climate cooperation (Milner and Tingley, 2013; Chilton, Milner and Tingley, 2020; Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters,

2018; Carnegie and Dolan, 2020; Naoi, 2020; Tingley and Tomz, 2020; Ferry and O’Brien-Udry, 2021; Mahajan, Kline

and Tingley, 2021).

3

2 The puzzle of foreign policy attitudes

Much of the study of public opinion about foreign policy is driven by a puzzle. On the one hand,

most members of the public are “rationally ignorant” about politics in general (Lupia and McCub-

bins, 1998), especially international politics, which is far removed from many citizens’ daily lives

(Guisinger, 2009). On the other hand, despite this lack of knowledge, the public has relatively strong

views on many foreign policy issues; Americans are routinely willing to send troops to countries they

cannot otherwise place on a map (Dropp, Kertzer and Zeitzoff, 2014). Against the skepticism of

postwar cynics (Almond, 1950; Kennan, 1951), the mass public’s foreign policy attitudes show con-

siderable structure, and are in fact better organized “than a bowl of cornflakes” (McGuire, 1989,

50). The question is where this structure comes from. Political psychologists have pointed to two

different families of explanations to account for these findings: top-down models pointing the impor-

tance of elite cues, and bottom-up models emphasizing the role of foreign policy orientations, core

values, and images.

2.1 Top-down models: elite cues

One class of theoretical models points to the role of elite cues, arguing that the public is largely

ignorant about foreign policy, such that it makes up its mind by listening to the recommendations

of trusted partisan elites (Berinsky, 2009; Guisinger and Saunders, 2017). Although elite cue-taking

models are popular in the study of domestic political behavior as well (e.g. Zaller, 1992; Lenz, 2013),

they are seen as particularly relevant in the study of public opinion about foreign policy given the

extent to which many international events are seen as being relatively far removed from ordinary

citizens’ lives (Rosenau, 1961). Foreign economic policy issues like trade are typically understood as a

“hard” rather than an “easy” issue (Carmines and Stimson, 1980), with the nuances of trade theories

like Stolper-Samuelson or Ricardo-Viner too technical for many citizens to understand (Hiscox, 2006;

Guisinger, 2017; Rho and Tomz, 2017). At least in the United States, foreign security policy issues

typically involve events taking place on the other side of the globe, about which citizens are often

unaware and do not directly experience themselves (Kertzer, 2013). According to top-down models of

public opinion in foreign policy, citizens therefore form judgments by listening to what their preferred

partisan political elites have to say: when Democratic and Republican leaders in Washington are

united on foreign policy issues – as the two parties traditionally were during the period of Cold War

4

consensus when both parties largely stood behind liberal internationalism (Schlesinger Jr., 1949;

Gowa, 1998) — Democrats and Republicans in the public will be united as well. When partisan

elites are divided — as they were during the Iraq War (Berinsky, 2009; Baum and Groeling, 2009b),

these divisions will be mirrored at the public level as well.

Top-down models rely on important sets of psychological microfoundations. The Zaller (1992)

receive-accept-sample (RAS) model, in which individuals’ political attitudes are a function of i)

what information they are exposed to, ii) whether they resist or accept the information they do

receive, and iii) which of these considerations most easily come to mind when answering survey

questions, builds on earlier work in psychology differentiating between on-line and memory-based

processing, for example (Hastie and Park, 1986; Lodge, McGraw and Stroh, 1989). Similarly, much

of the explanatory power of the role of partisanship in politics hinges on partisanship as a social

identity, tying elite-driven theories into a broader literature on the psychology of intergroup relations

(Huddy, 2001; Mason, 2018). Yet top-down theories of public opinion in foreign policy can also be

relatively psychologically sparse and privilege structure over agency – focusing more on the political

information environment that citizens are embedded in rather than the cognitive properties of the

citizens themselves.

Of course, partisan elites aren’t the only sources individuals can get information from in foreign

policy, and subsequent work has focused on the extent to which individuals also take cues in foreign

policy from social peers and interpersonal discussion (Radziszewski, 2013; Kertzer and Zeitzoff,

2017), which becomes particularly important with the rise of social media, which is altering how

citizens receive political information (Settle, 2018). They can also turn to foreign voices (Hayes and

Guardino, 2011; Murray, 2014; Leep and Pressman, 2019), particularly those offered by international

institutions like the United Nations or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which

provide citizens in member states uncertain about the merits of a given military intervention a

chance to “get a second opinion” (Thompson, 2009; Chapman, 2011; Grieco et al., 2011; Walter et al.,

2018; Greenhill, 2020). The powerful effect of the endorsements of international institutions is one

reason why powerful countries like the United States often choose to conduct military interventions

multilaterally rather than go it alone, even though doing so means accepting constraints imposed by

allies who might not be bringing as many military resources to the table: by securing the blessing

of other members of the international community, it helps bring reluctant members of their publics

on board.

5

Since the chief causal force in top-down theories of public opinion is the broader information

environment, these theories tend to be very good at explaining longitudinal changes in public opinion

over time. For example, top-down theories are well suited to explain the extent to which the

partisan split in American attitudes towards Russia reversed itself from 2015-2017, or to which

Republicans soured on immigration and embraced protectionism when Donald Trump entered office

(Kertzer, Brooks and Brooks, 2021). However, these theories also face a number of challenges. For

example, they have difficulty explaining the presence of strong attitudes in the absence of elite cues

(Kertzer and Zeitzoff, 2017), the many political issues in which public and elite opinion diverge

(Page and Bouton, 2007, though see Kertzer, 2020), or why left and right-wing political parties

across western democracies in very different contexts nonetheless feature similar ideological divides

on many foreign policy issues (Rathbun, 2004). Looking cross-nationally, for example, why does

support for economic redistribution tend to be positively correlated with support for fighting climate

change, but negatively correlated with support for military spending? (Enke, Rodr´ıguez-Padilla and

Zimmerman, 2020) These crossnational similarities raise the possibility that there is something

substantive about how people think about political issues themselves: rather than publics’ political

attitudes being entirely orchestrated by opportunistic elites from above, it suggests that certain

types of policy preferences can also congeal from below.

2.2 Bottom-up models: orientations, values, and images

In contrast to top-down models that emphasize the role of political elites and the mass media in

shaping how people think about foreign policy issues, bottom-up models build on the psychological

literature on ideology, values, stereotypes, and schema to explain why foreign policy attitudes often

cluster together in systematic and meaningful ways (Kertzer and Zeitzoff, 2017). This work does

not deny the importance of political elites in placing issues on the political agenda or mobilizing

their supporters, but also points out that political issues often have a number of intrinsic properties

of their own that affect how people think about them. Work in this tradition tends to focus on one

of two types of models (Kertzer and Powers, Forthcoming).

The first are horizontal models that show how foreign policy attitudes tend to cluster along

a small number of ideological orientations. The central intuition behind many of these models

is that foreign policy attitudes aren’t random, but they aren’t unidimensional either. Although

we sometimes situate foreign policy preferences on a single isolationist-internationalist continuum,

6

the former reflecting a desire for one’s country to focus more on its own problems, and the latter

indicating a desire to play an active role in world politics (e.g. Klingberg, 1952; Kertzer, 2013),

horizontal models suggest this intuition is too simple, since there are multiple ways individuals can

want their countries to be involved in or engaged with international politics (Bardes and Oldendick,

1978; Holsti, 1979).

The most popular horizontal model of foreign policy attitudes maps foreign policy preferences

onto two dimensions, which Wittkopf (1990), Holsti (2004) and others refer to as militant inter-

nationalism (MI), which measures individuals’ beliefs about the desirability and efficacy of the use

of force, and cooperative internationalism (CI), which measures the extent to which individuals are

multilateralists interested in working with other members of the international community and in-

ternational institutions like the United Nations to solve global problems.

5

Both individuals high

in MI and individuals high in CI are internationalists, neither of whom want their country to turn

inwards and focus less on the world’s problems and more on their own, but their internationalism

takes different forms. For militant internationalists, international engagement is crucial to deter-

ring your country’s adversaries and protecting your country’s national security interests, whereas

for cooperative internationalists, solving global problems is necessary to make the world a better

place. These two dimensions are orthogonal to one another, such that individuals can be hawks

(high in MI but low in CI, like former Donald Trump-era national security advisor John Bolton),

doves (high in CI and low in MI, like former US president Jimmy Carter), internationalists high in

both dimensions (such as former Clinton-era secretary of state, Madeleine Albright), or isolationists

low in both (such as US senator Rand Paul).

Although developed in the American mass public context, subsequent support for this two-

dimensional structure has been obtained in a range of countries, including Sweden (Bjereld and

Ekengren, 1999), Britain (Reifler, Scotto and Clarke, 2011), India (Ganguly, Hellwig and Thompson,

2017), and France (Gravelle, Reifler and Scotto, 2017), as well as elite policy-makers (Wittkopf,

1987; Rathbun, 2007). And, although the MI/CI framework was developed by political scientists,

psychologists have recently argued in favor of a similar two-dimensional model (Bizumic et al.,

2013), largely developed independently of this prior work. Constructs like militant internationalism

or cooperative internationalism are what public opinion scholars call orientations or postures, in

5

Isolationism is also sometimes identified as an additional, third dimension (e.g. Chittick, Billingsley and Travis,

1995.

7

that they are general tendencies on which individuals tend to systematically differ from one another,

and which are relatively stable through time. It is true, for example, that in times of external

threat, individuals tend to express more hawkish views than in non-threatening contexts (Gadarian,

2010). Yet it is also true that individuals who were relatively hawkish in one time period tend to

be relatively hawkish in others: Murray (1996), for example, shows that individuals high in militant

internationalism before the Berlin Wall fell were no less hawkish after the Cold War ended; their

threat perceptions had just shifted from the Soviets to other potential targets.

One challenge with purely horizontal models of foreign policy attitudes, however, is that they

were largely inductively derived by researchers sifting through public opinion data using factor

analysis, and lack an overarching theoretical framework. These models tell us that some people are

systematically more acceptant of the use of force than others, for example, but don’t seek to explain

this variation theoretically, or with reference to overarching psychological theories. They tell us that

some people are more hawkish than others, but don’t tell us why.

Seeking to meet these challenges are vertical or hierarchical models of foreign policy preferences.

Hierarchical models understand foreign policy attitudes as being organized between constructs ex-

isting at different levels of generality, with the most specific policy attitudes at the bottom of the

hierarchy, foreign policy orientations like MI or CI in the middle of the hierarchy, and general values

at the top. Thus, hierarchical models show not just that these general foreign policy orientations

predict foreign policy preferences on more specific issues (individuals who were supportive of the

United States remaining in Afghanistan tend to be high in MI more generally), but that these for-

eign policy postures are themselves predicted by deeper values or orientations (Hurwitz and Peffley,

1987). Crucially, these values or orientations can transcend or come from outside of the domain of

foreign policy, like moral values (Kertzer et al., 2014; Kreps and Maxey, 2018) or personal values

(Rathbun et al., 2016). People who care about retribution in general, for example, are more likely

to support punitive wars (Liberman, 2006) and oppose financial bailouts that let borrowers off the

hook unconditionally (Rathbun, Powers and Anders, 2019); people who conceptualize fairness in

terms of the proportionality between effort and rewards are averse to free-riding in alliances (Pow-

ers et al., 2021); individuals who emphasize the value of self-transcendence are more supportive of

cosmopolitan foreign policies associated with cooperative internationalism (Bayram, 2015), and less

supportive of military campaigns associated with militant internationalism (O’Dwyer and C¸ oymak,

2020).

8

Other vertical models root foreign policy preferences in other ideological orientations, such as

right-wing authoritarianism (RWA), which tends to be associated with hawkish or hardline policy

preferences against both state and non-state actors (Doty et al., 1997; Cohrs and Moschner, 2002;

McFarland, 2005; Albuyeh and Paradis, 2018), or social dominance orientation (SDO) (Mutz and

Kim, 2017), although the relationship here is less straightforward (Henry et al., 2005). Rathbun

(2020) integrates horizontal and vertical models of foreign policy into a dual process model of foreign

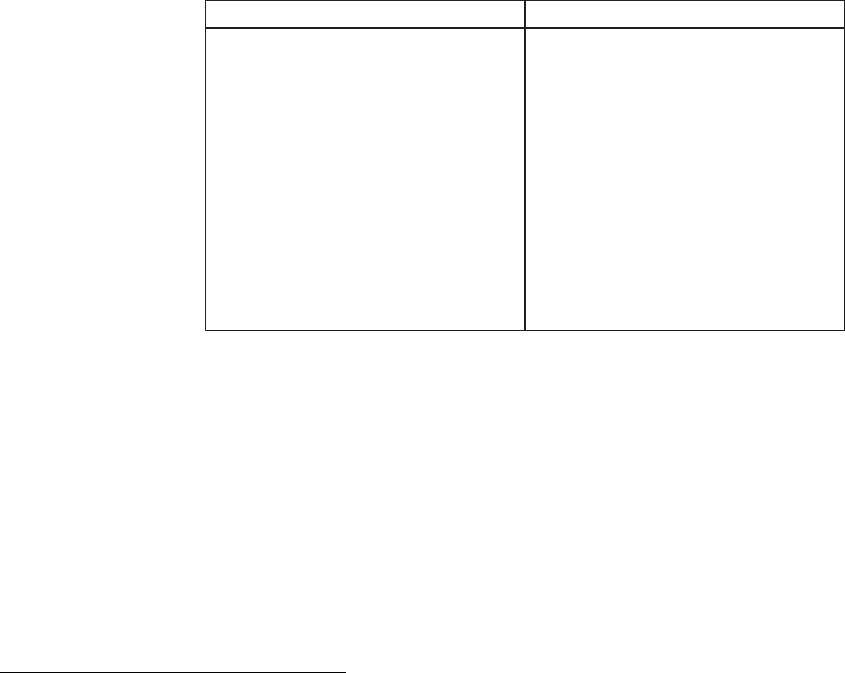

policy preferences illustrated in Figure 1, linking CI to motivational goals of equality and taking care

of others (and thus, core values such as harm/care, fairness/reciprocity, and self-transcendence), and

MI to motivational goals of protecting the ingroup from physical threats (and thus, core values of

conformity and tradition, authority and loyalty).

6

Figure 1: Linking foreign policy orientations to other frameworks in political psychology

Militant internationalism (MI) Cooperative internationalism (CI)

Using threats and force to deter adversaries

and protect allies

Working with the international community

to solve global problems (fighting climate

change, global poverty, etc.)

Foreign policy

preferences

Motivational goal

(Janoff-Bulman 2009)

To protect the ingroup from danger To provide for the well-being of others

Moral foundations

(Graham et al 2009)

Binding values: authority and loyalty Individualizing values: harm/care and

fairness/reciprocity

Personal values

(Schwartz et al 1992)

Conservation Self-transcendence

Worldview and ideology

(Duckitt et al 2002)

Dangerous world beliefs

Right-wing authoritarianism (RWA)

Competitive jungle beliefs (-)

Social dominance orientation (SDO) (-)

Modified from Rathbun’s (2020) dual process model of foreign policy orientations, which illustrates how the two basic

orientations that structure foreign policy attitudes are themselves rooted in distinct motivational goals, values, and

worldviews.

The Big 5 personality traits have similarly been found to systematically predict foreign pol-

icy attitudes (Schoen, 2007; Nielsen, 2016; Gravelle, Reifler and Scotto, 2020). Individuals high in

openness to experience and agreeableness, for example, tend to be more supportive of redistributive

global justice. Since a substantial portion of these core values, ideological orientations, and person-

ality traits are formed prior to members of the public entering a given foreign policy situation, the

6

On motivational goals underlying political ideology, see Janoff-Bulman (2009); on moral and personal values,

see Graham, Haidt and Nosek (2009); Schwartz (1992); on the relationship between worldviews and ideological

orientations, see Duckitt et al. (2002).

9

takeaway of this literature has been to show how an important part of foreign policy attitudes are

prepolitical, shaped by the same psychological and ideological predispositions that guide our choices

and behaviors in everyday life. These predispositions offer an alternative route to opinion forma-

tion in the absence of elite cues: even individuals who lack the political sophistication necessary

to think ideologically about international politics can rely on their core values to form judgments

about foreign policy questions (Rathbun et al., 2016).

2.3 Image theory

Another body of literature examines the structure of foreign policy attitudes from a different per-

spective, focusing not on the policies we want our countries to carry out, but on the images or

perceptions we have of other states on the world stage (Boulding, 1959; Holsti, 1967; Cottam, 1994;

Herrmann and Fischerkeller, 1995; Herrmann, 2013; Castano, Bonacossa and Gries, 2016). Citizens

in democratic countries generally have fairly strong feelings about which countries are their friends,

and which are not (Gries et al., 2020): image theory provides one way of understanding how these

feelings come about.

Image theory can best be understood as an interactionist middle ground between nomothetic

structural theorizing and idiographic thick description. To one side, the study of images is a coun-

terpoint to structural or rationalist theories that reduce behavior to the environments actors find

themselves in (e.g. Waltz, 1979; Lake and Powell, 1999): image theory argues that perceptions, rather

than structure, determines behavior, since actors can define the situations they face in myriad ways.

However, this emphasis on unit-level attributes does not necessarily mean forgoing nomothetic the-

orizing, particularly if the content of actors’ perceptions share underlying structures. Image theory,

then, can also be distinguished from purely ideographic accounts, which emphasize the uniqueness

of actors and their relationships without striving to achieve a generalizable framework about how

those relationships are structured.

In the most influential contemporary incarnation of image theory (Herrmann, 2013), both lead-

ers’ and ordinary citizens’ perceptions of other countries are understood as a schematic judgment

structured along three dimensions illustrated in Figure 2: relative power, the degree of perceived

threat or opportunity, and perceived status or cultural sophistication. Observers can classify coun-

tries in three different ways along each of these dimensions. Along the first dimension, an actor

can be evaluated as less powerful, equally powerful, or more powerful than the observer; along the

10

second dimension, an actor can be considered to pose a threat, a chance for mutual gain, or an

opportunity for exploitation; along the third, the actor can be perceived as of lower status, equal

status, or higher status. Although 27 different combinations of evaluations are possible (e.g. O’Reilly

(2007) argues that the “rogue state” is a combination of an enemy image and a degenerate image),

in practice, the framework focuses upon the five combinations that appear particularly frequently.

First is the enemy image, which refers to an actor of comparable power and equal cultural status

that is seen as posing a threat (e.g. US views of the Soviet Union during the Cold War). Second

is the ally image, which is given to actors of comparable power and equal cultural status that are

seen as posing opportunities for cooperation (e.g. US views of NATO allies during the Cold War).

Third are imperialist images, which are given to actors of superior power and equal cultural status

that are seen as posing a threat (e.g. Iranian views of the United States during the 1980s). The

final two types of images, degenerate and colony images, are both given to actors perceived as being

of inferior cultural status. Of those, degenerate images are given to actors of comparable capability

but who are seen as being in cultural decay and thus who offer an opportunity for exploitation (e.g.

Iraqi views of Iran in the 1980s), while colony images are given to actors with inferior capabilities

and an opportunity for exploitation (e.g. US views of the South Vietnamese in the 1960s).

Three considerations here are relevant. First, images are stereotypes about other countries, and

although image theory was developed independently of work on stereotypes in social psychology, it

is striking the extent to which it reaches similar conclusions as popular psychological approaches

to the study of stereotypes such as Fiske et al.’s stereotype content model (SCM), which posits

that stereotypic content can be understood on two dimensions: warmth and competence, mapping

onto perceived intentions, and perceived capabilities, respectively. Moreover, in the SCM warmth is

determined by the presence or absence of competition (further relating to goal compatibility in the

traditional image framework), while competence is determined by the group’s power within society

(analogous to capability). In this sense, images in international politics are inherently relational:

the images we have about other countries are functions of what we think they can do for us — or,

to us.

Second, images are sticky. Once they become embedded, they are resistant to change, and

affects how subsequent information is interpreted. This serves as a challenge both to models of

reassurance in international relations that argue that actors can overcome distrust by engaging in

costly signals (Kertzer, Rathbun and Rathbun, 2020), and to theories of public diplomacy (Goldsmith

11

Figure 2: Images of other countries

Imperialist

Superior Comparable Inferior

Relative Capability

Exploitation

Cooperation

Threat

Perceived

Opportunity

Enemy

Superior

Equal

Inferior

Cultural

Status

Degenerate

Ally

Colony

Modified from Herrmann and Fischerkeller (1995), who argued that images of other countries are structured along

three dimensions: relative capabilities, perceived threat, and perceived status. Although 27 (3

3

) different combinations

are possible, in practice the framework tends to focus on five combinatorial constructs in particular: the enemy image

(equal in power and cultural status, but with threatening intentions), ally image (comparable in power and cultural

status, but who pose an opportunity for cooperation), imperialist image (greater in power, equal in cultural status,

and who pose a threat), degenerate image (comparable in power, inferior in status, and who offer an opportunity for

exploitation), and colony image (weaker in power, inferior in status, and who offer an opportunity for exploitation.

12

and Horiuchi, 2009; Schatz and Levine, 2010), which posit that actors can use foreign visits, state

broadcasting, and so on to win over hearts and minds of foreign publics. It is not that images

make persuasion impossible, but rather, that they act as prisms through which we interpret even

the grandest of gestures: in response to costly signals, for example, the individuals who update the

most are often those who are already convinced (Kertzer, Rathbun and Rathbun, 2020).

Third, images are integrated schemas (Castano, Bonacossa and Gries, 2016): because these are

holistic judgments, when individuals are primed with one component of an image they can fill in the

blanks (Herrmann et al., 1997). Knowing a target is inferior in capability and lower in cultural status,

for example, primes individuals to adopt a colony image and perceive the target as as representing

a perceived opportunity for exploitation. One of the striking tendencies in foreign policy is the

extent to which these schemas recur both across space and across time: for example, the narratives

many Americans offered in the early phases of the war in Afghanistan (of a local population in

need of protection from an oppressive regime, requiring outside intervention) is similar to the same

narratives offered in earlier interventions in Vietnam, and similar to narratives European imperial

powers frequently adopted in their own interventions. In this sense, what makes images powerful

is the extent to which they are also linked to strategic scripts (Herrmann and Fischerkeller, 1995),

implicating specific action tendencies: the stereotypes we have about other actors tells us how

we should treat them. As the dehumanization literature reminds us, when we develop images of

adversaries that deny their human qualities, we are able to morally disengage with them, permitting

us to use violence against them (Haslam and Loughnan, 2014; Bruneau and Kteily, 2017). In this

way, as with core values, images offer another bottom-up solution for individuals in the mass public

who may lack knowledge about individual countries to nonetheless espouse policy preferences about

them.

3 Public opinion in international security

As noted above, one reason why the public opinion about foreign policy literature has flourished in

recent years is because international relations itself has become increasingly interested in domestic

politics more generally. This is especially the case in the study of international security and conflict,

which has emphasized the role of public opinion in a variety of different contexts. Much of the

research in this space adopts a microfoundational approach (Kertzer, 2017), showing that even the

13

grandest of macro-level theories in IR often rest on a set of causal mechanisms operating at the

individual level, such as the beliefs, preferences, and reactions of members of the public in response

to external events. This scholarship seeks to test empirically whether these micro-level assumptions

are true, and often borrows explicitly from psychological theoretical frameworks in the process. I

discuss four such examples below.

3.1 The democratic peace

The first of these concerns what international relations scholars refer to as the democratic peace: the

observation that while democracies often go to war with non-democratic regimes, they do not fight

one another (Doyle, 1986; Oneal and Russett, 1991). While this claim is not without its critics —

from unease about how democracies are coded, to questions about whether democracy’s purported

effects are confounded with other factors (Layne, 1994; Oren, 1995; Farber and Gowa, 1997) — it

nonetheless is relatively widely established, such that Levy (1988, 662) famously characterizes the

democratic peace “as close as anything we have to an empirical law in international relations.”

There are a number of different theoretical reasons why we might expect democracies not to

fight one another, ranging from shared liberal values, to democratic leaders avoiding costly foreign

policies because they are subject to greater institutional constraints (Owen, 1994; Maoz and Russett,

1993). One important class of explanations, however, relates specifically to the political incentives

of democratic leaders who want to remain in office (Schultz, 1999; Bueno de Mesquita and Morrow,

1999). If the reason democracies readily fight non-democracies but don’t fight each other is due to

democratic leaders being constrained by public opinion, this implies that democratic publics have a

particular aversion to fighting democracies — a pattern that should manifest itself in lab and survey

experiments, in which researchers present respondents with a hypothetical military intervention,

manipulate the regime type of the target, and test how it affects support for the use of force.

7

As

a result, a number of political scientists began testing these propositions directly, often drawing on

psychological mechanisms in the process (Mintz and Geva, 1993; Johns and Davies, 2012; Lacina and

Lee, 2013). Tomz and Weeks (2013) find that the central mechanism driving the democratic peace

in the context of public opinion are moral judgments: democratic citizens perceive fighting other

7

Note that if leaders were merely constrained by democratic publics being more war averse in general, the demo-

cratic piece should be monadic (that is, democracies should fight less more generally), but most treatments of the

democratic peace find it to be dyadic instead (democracies don’t fight one another, but are just as likely to fight

non-democratic states).

14

democracies to be fundamentally morally wrong – another instance of the important role that moral

considerations play in shaping public opinion in foreign policy (e.g. Herrmann and Shannon, 2001;

Kertzer et al., 2014; Kreps and Maxey, 2018; Rathbun, Powers and Anders, 2019) . In subsequent

work, they show that these moral judgments are core to public opinion about alliances, which may

help explain why democratic allies are more reliable (Tomz and Weeks, 2021).

Another potential set of psychological mechanisms underlying the democratic peace concerns

democracy as a social identity. According to this argument, democracies don’t fight one another

because they perceive each other to be part of a common ingroup (Risse-Kappen, 1995; Hayes, 2016);

we might use violence to resolve disputes with outsiders, but not with those who we perceive are like

us. While some of this work focuses on these identity-based mechanisms at the elite level (Hermann

and Kegley, 1995; Schafer and Walker, 2006), Hayes (2012) shows it extends to publics writ large:

Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger failed to “securitize” India because the American public saw

India as a fellow democracy, and thus as inherently unthreatening. Rousseau and Garcia-Retamero

(2007) uses survey experiments to demonstrate a similar mechanism, showing that threat perception

in the context of public opinion in foreign policy is a function of perceptions of shared social identity,

not just military power as realists might predict.

Most of public opinion research on the democratic peace have focused on public opinion in

democratic contexts. One exception is Bell and Quek (2018), who obtain similar findings in mass

publics in an authoritarian regime, raising interesting questions about how to think about the causal

mechanisms at work. This also raises a broader point about the evidentiary base we use to test our

theories of public opinion in foreign policy, a point to which I return in the conclusion.

3.2 Audience costs

Democratic distinctiveness in foreign policy doesn’t just extend to who democracies go to war with,

but also how they conduct themselves in crises more generally (Schultz, 2001). As a result, another

established literature in international relations involves domestic audience costs (Fearon, 1994). The

intuition behind the audience cost model is simple: if leaders face domestic constituencies who dislike

it when leaders issue threats but fail to follow through on them — whether because they reveal the

leader to be incompetent, or sully the national honor — then leaders who face these constraints

should only issue threats when they truly intend to follow through (Guisinger and Smith, 2002).

Threats should therefore be more credible when issued in public (though see McManus and Yarhi-

15

Milo, 2017; Katagiri and Min, 2019). In this manner, audience cost models also implicate the

democratic peace: if democratic threats are seen as more credible than non-democratic ones because

democratic audiences have institutionalized mechanisms of punishing leaders whose conduct they

find wanting, this provides another potential explanation for why democracies are less likely to fight

one another, since democracies should be better able to signal their resolve than their non-democratic

counterparts.

8

Both audience cost theory and theories emphasizing the greater credibility of democratic threats

more generally are not without their critics (e.g. Snyder and Borghard, 2011; Downes and Sechser,

2012), much of which focuses on observational data. But, although audience cost theory is of-

ten studied using observational data (e.g. Partell and Palmer, 1999; Kurizaki and Whang, 2015;

Schlesinger and Levy, 2021), given the challenges of strategic selection and the extent to which the

key microfoundations of the theory reside at the individual-level, it is also fruitfully studied using

survey experiments, which have perhaps become the dominant approach through which they have

been investigated in the past decade. These experimental studies test audience cost theory’s micro-

foundations by probing the extent to which respondents dislike leaders who issue empty threats more

than they do those who pledged to stay out in the first place (e.g. Tomz, 2007; Trager and Vavreck,

2011; Levendusky and Horowitz, 2012; Levy et al., 2015; Kertzer and Brutger, 2016; Lin-Greenberg,

2019; Nomikos and Sambanis, 2019; Schwartz and Blair, 2020). Much of this work focuses more

on varying situational features rather than probing psychological mechanisms. One exception is

Trager and Vavreck (2011) and Levendusky and Horowitz (2012), who focus on how partisanship

complicates audience cost theory. Another is Kertzer and Brutger (2016), who incorporate a se-

ries of dispositional characteristics from political psychology, showing that different segments of the

public punish empty threats for different reasons. Hawks, high in militant internationalism (MI),

for example, punish leaders for failing to follow through on the intervention, whereas doves dislike

empty threats because they dislike threats in general. Similarly, individuals low in international

trust care more about their country maintaining a reputation for resolve so as not to be exploited

by others, and therefore more likely to punish leaders for showing weakness, whereas individuals

high in international trust punish leaders for threatening to use force. More recently, Schwartz and

Blair (2020) examine how gender stereotypes complicate audience cost models, showing that female

8

Of course, even if democracies are better able to signal their resolve, it may also be the case that democracies

who end up in a crisis with one another would also find it more difficult to back down – which should also reduce the

likelihood of these crises occurring. I’m grateful to Jack Levy for this point.

16

leaders pay steeper costs for backing down on empty threats, as do male leaders who back down

against female rivals.

Although public reactions to leader behavior constitute an important microfoundation for au-

dience cost models, another key assumption involves the role of the mass media, since a free press

better allows citizens to monitor their leaders’ foreign policy behavior (Slantchev, 2006). Potter and

Baum (2014) show that countries that feature greater media access — particularly in multiparty

democracies, where opposition parties have incentives to draw attention to leaders’ foreign policy

missteps — are less likely to have their threats reciprocated in international crises. This also points

to the relationship between public opinion and intra-elite bargaining; if leaders co-opt key regime

insiders — advisers, cabinet members, and so on — foreign policy failures are more likely to escape

the public’s notice (Saunders, 2015). Yet it is not that elite politics necessarily trump mass politics,

since it is elites’ ability to loop in the public that provides a key source of their power.

3.3 Rally around the flag effects

If audience cost models focus on how publics react to empty threats issued by their leaders, another

class of theoretical models in IR focus on how publics react to the international threat environment

more broadly, and the tendency for public support for leaders and their policies in times of increased

threat (Mueller, 1973; Lee, 1977; Baum, 2002). These surges in public support can come in response

to one’s country coming under attack: for example, public opinion polls suggest that public support

for Jimmy Carter soared by 26% following the onset of the Iranian Hostage Crisis in 1979 (Callaghan

and Virtanen, 1993), while George W. Bush’s popularity soared by 35% the week of the September

11th attacks (Hetherington and Nelson, 2003). They can also occur when leaders decide to go war

or commit troops – as was the case in both the 1991 Gulf War and the 2003 Iraq war in the United

States, or in the Falklands War in the United Kingdom (Lai and Reiter, 2005), and has been detected

in experimental studies in non-Western contexts as well (e.g. Kobayashi and Katagiri, 2018).

Explanations for rally effects focus on two different classes of mechanisms: information-based

theories, and affective theories. Information-based theories of rally effects, like top-down theories

of public opinion in foreign policy more generally, focus on the unique nature of the information

environment during times of crisis. Some of these theories argue that in times of crisis, the public

comes together because opposition criticism of the executive – especially in Congress – subsides,

thereby bringing partisan opponents of the President on board (Brody, 1991). Others point to

17

the nature of media coverage during times of crisis, noting that the “marketplace of ideas” often

fails (Kauffmann, 2004), or that journalistic incentives means that the media is always more likely

to cover opposition praise than cross-party criticism (Groeling and Baum, 2008). Another infor-

mational argument is advanced by Colaresi (2007), who notes that national security issues feature

marked informational asymmetries between the public and the executive, and that the public is more

likely to rally in circumstances where leaders are likely to be punished if a mission is against the

public interest. A related informational argument comes from Haynes (2017), who, building on an

earlier literature on how leaders launch risky foreign policies in order to “gamble for resurrection”

(Downs and Rocke, 1994), argues that leaders often initiate force against powerful targets in order

to demonstrate competence to their constituents.

9

In contrast with these cognitive theories, affective accounts of rally effects emphasize the role

of emotions in political behavior (Marcus, 2000; Huddy et al., 2005; Mercer, 2010). These include

patriotism-based explanations, which argue that international crises cause citizens to gravitate to-

wards leaders as symbols of national unity (Mueller, 1973; Lee, 1977), a classic conflict-cohesion

theory in which external threat causes internal divisions to be set aside as members of the ingroup

band together (Coser, 1956; Stein, 1976; but see Myrick, 2021). Another class of emotion-based

theories focus on the distinct role of anxiety, which ground accounts of rallies in psychological the-

ories of threat and emotional appraisal, arguing that it is specifically threat-induced anger (rather

than, say, anxiety) that produces rally effects (Lambert et al., 2010). These affective-based theories

argue that information-based explanations of rally effects suffer from endogeneity, in that a lack of

opposition criticism may be better seen as a consequence of rally effects rather than a cause of them

(Hetherington and Nelson, 2003). In contrast, information-based theories argue that affective-based

explanations of rally effects are underspecified, in that they cannot explain why rally effects vary in

magnitude (Baum, 2002) and duration (Kam and Ramos, 2008).

Whatever their cause, the presence of rally effects has important implications for the domestic

politics of foreign policy. Rally effects often serve as a microfoundations for a broader research

agenda on diversionary war, which explores the extent to which leaders have incentives to enter into

foreign policy crises in order to redirect domestic discontent and increase their regime’s popularity at

9

Of course, this raises interesting questions about why foreign policy aggressiveness signals competence – suggesting

the limits of juxtaposing a “psychological rally effect” with “increased perceptions of leader competence” (Haynes,

2017, 340), since it is arguably difficult to understand the latter without the former. On the centrality of competence

in public opinion about foreign policy, see Friedman (2021).

18

home (e.g. Lian and Oneal, 1993; Fordham, 1998; Theiler, 2018). Leaders may also have incentives

to fight in order to satisfy their public’s desire for status (Powers and Renshon, 2021), or respond to

humiliation (Barnhart, 2017; Masterson, 2021). Yet even setting aside other critiques of diversionary

war theories (Levy, 1989), one potential challenge is that rallies typically consist of a sudden surge of

support followed by a gradual decay as the public “loses heart” (Fletcher, Bastedo and Hove, 2009).

By themselves, then, they are thus unlikely to be able to sustain lengthy military interventions,

particularly those that don’t show immediate signs of success (Eichenberg, 2005; Gelpi, Feaver

and Reifler, 2009), or for left-wing governments whose domestic constituencies are typically less

enthusiastic about the use of force (Koch and Sullivan, 2010).

3.4 Against type models

Like audience costs, another class of theoretical models in IR also focuses on credibility, but from a

different angle. Whereas audience cost models focus on how leaders make threats more credible by

making them in public, against type models focus on how leaders make their policy proposals more

credible by acting out of character. Although the logic of against type models was formalized in the

context of models of legislative bargaining in American politics (Krehbiel, 1991), in IR it is often

understood specifically in the greater ability of hawks to deliver the olive branch, as in the notion

that only Nixon could go to China (e.g. Cukierman and Tommasi, 1998; Schultz, 2005; Fehrs, 2014;

Kane and Norpoth, 2017).

The intuition behind against type models is relatively straightforward: an audience is uncertain

about the quality of a policy being proposed by a leader, so it uses knowledge it has about the leader’s

predispositions (either based on her previous behavior, or the political party she represents) to

evaluate the proposal’s credibility or merit. Biased signalers can therefore send the most informative

signals (Calvert, 1985): if a leader with a reputation for hawkishness supports a peace deal, it is

seen as more credible than if a leader with a reputation for dovishness does the same, just as it is

more credible when Fox News criticizes Republicans than when MSNBC does (Baum and Groeling,

2009a). This same logic is also implicated in scholarship on the informative value of cues from

international institutions: if voters know that the United Nations is opposed to international conflict

more generally but the UN Security Council nonetheless endorses a given international intervention,

its endorsement should send a more informative signal (Thompson, 2009; Chapman, 2011)

As with the other theoretical models described above, against type models rely on a number

19

of microfoundations in public opinion that are conducive to being tested empirically using survey

experiments. Saunders (2018) shows that the public is more likely to oppose the use of force when ad-

visers with reputations for hawkishness endorse it. Trager and Vavreck (2011) finds that Democrats

derive more political rewards from going to war than Republicans do. Mattes and Weeks (2019b)

find that hawks face fewer domestic costs to pursuing rapprochment than doves do – making it easier

for hawks to deliver the olive branch. Yet other work suggests against type models have some impor-

tant limitations. Mattes and Weeks (2019a) shows that even while domestic audiences respond more

favorably to cooperative attempts when they come from hawks rather than doves, foreign audiences

find hawkish reconciliation efforts to be less sincere. And, while much of the against type literature

presumes that audiences infer leaders’ types from their political party (with left-leaning parties be-

ing having reputations for dovishness, and right-leaning parties having reputations for hawkishness),

Kertzer, Brooks and Brooks (2021) build on psychological research on stereotypes to show that in

the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties have much weaker and less distinct types

in foreign policy issues than domestic political ones, suggesting that against type effects in foreign

policy may be weaker than these models assume.

3.5 Nuclear weapons

One recent area of growth in public opinion research in foreign policy concerns public opinion about

nuclear weapons use. In an influential article, Tannenwald (1999) argued that the United States has

not used nuclear weapons in combat since 1945 due to the emergence of an anti-nuclear norm that

rendered the tactical use of nuclear weapons taboo. As with other theories in international security,

this argument rests on particular individual-level microfoundations: assumptions about how people

understand and form preferences about nuclear weapons. The result is a rapidly growing literature

using survey experiments to examine public opinion about nuclear weapons.

10

Some of this literature

focuses specifically on the question of the nuclear taboo, comparing how public attitudes towards

the use of force vary between nuclear attacks versus their conventional counterparts (e.g. Press,

Sagan and Valentino, 2013; Carpenter and Montgomery, 2020; Rathbun and Stein, 2020; Koch and

Wells, 2021; Smetana and Wunderlich, 2021). Others turn to nuclear acquisition rather than use,

exploring the depth of nuclear forbearance on questions ranging from the breadth of public support

10

There is also a related literature exploring public attitudes towards other types of emerging technologies, such as

drones and satellites (Kreps, 2014; Lin-Greenberg and Milonopoulos, 2021), killer robots (Horowitz, 2016; Young and

Carpenter, 2018), and cyber (Gomez and Whyte, 2021; Kostyuk and Wayne, 2021; Shandler et al., 2021).

20

in Japan for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) (Baron, Gibbons and

Herzog, 2020), to the effects of extended deterrence and security guarantees on support for nuclear

weapons acquisition in South Korea (Ko, 2019; Sukin, 2020).

The precise observable implications of nuclear taboo arguments in survey or experimental con-

texts are sometimes ambiguous. For example, should nuclear taboos be manifest in public opinion,

elite opinion, or both (Pauly, 2018)? Most pressingly, what patterns of public support for nuclear

weapons would affirm or challenge the existence of a nuclear taboo? Is the relevant quantity of

interest the absolute level of support for nuclear weapons use? (If so, what proportion of the public

supporting nuclear weapons use would indicate the absence of a taboo?) Or is it about whether

support for nuclear weapons use increases as nuclear weapons become more instrumentally useful,

under the presumption that taboo reasoning prohibits instrumentalized tradeoff calculations? Or

is it a difference-in-difference, in which researchers compare the elasticity of demand for nuclear

weapons at different levels of instrumental value with the elasticity of demand for other types of

weapons? Given the extent to which a robust psychological literature exists on sacred values and

taboo tradeoffs more generally (e.g. Fiske and Tetlock, 1997; Tetlock, 2003; McGraw, Tetlock and

Kristel, 2003; Ginges and Atran, 2013), further research putting the nuclear taboo in comparative

context with other types of taboos, or borrowing research designs or theoretical frameworks from

this related literature, could be valuable in further increasing our understanding of how nuclear

taboos work in practice, and how we know one when we see one.

11

4 Public opinion about international political economy

Much as in the study of international security and conflict, research on international political econ-

omy (IPE) has also become increasingly interested in the role of public opinion. Work in this

research tradition typically relies on an Open Economy Politics (OEP) framework, in which actors

are understood as having preferences over outcomes, which are then aggregated through domestic

institutions to shape state behavior (Milner, 1997; Lake, 2009). Crucially, actors’ preferences are

traditionally assumed to be based on their economic interests: those who stand to materially gain

from an economic policy should support it, while those who stand to materially lose from it should

not. For example, immigration attitudes should be driven by concerns about labor market compe-

11

This also applies to other taboo arguments, such as the chemical weapons taboo (Price, 1995) or water taboo

(Grech-Madin, 2021).

21

tition, such that citizens should oppose immigration from immigrants with similar skill levels, but

support it from immigrants with different skill levels (Hainmueller and Hiscox, 2010), since they

should be competing over jobs with the former but not the latter. Attitudes towards offshoring

should reflect its distributional consequences on different types of jobs, with workers whose occupa-

tions are highly susceptible to offshoring (computer programmers and telemarketers, for example)

opposing it more than workers in occupations whose occupations are less likely to be offsourced

(e.g. watch repairers and postal service mail sorters) (Blinder, 2009; Mansfield and Mutz, 2013).

Attitudes towards foreign direct investment (FDI) should reflect its expected income effects, with

skilled labor in recipient countries supporting it in particular (Pandya, 2010), since they represent

the segment of society in recipient countries who will gain the most from it. In this sense, public

opinion research in IPE has traditionally been less closely tied to political psychology than public

opinion research in international security (Kertzer and Tingley, 2018), since it was largely content

to ground its microfoundations in economic models rather than psychological ones. This has begun

to change.

This is particularly the case in the study of public opinion about international trade. Economic

frameworks like Hecksher-Ohlin and Ricardo-Viner make clear predictions about who the winners

and losers from free trade should be. The Heckscher-Ohlin model suggests that free trade should

benefit the owners of factors of production in which countries are abundantly endowed relative to

the rest of the world (e.g. in industrialized countries like the United States, skilled labor), and harm

the owners of factors of production that are relatively scarce. Highly skilled workers should thus

be more supportive of trade than low skilled workers. The Ricardo-Viner model predicts that trade

preferences will depend on the specific industries that individuals work in: individuals working in

sectors in which their country has a comparative advantage will be more supportive of free trade

than those in sectors that are disadvantaged (Scheve and Slaughter, 2001).

An earlier generation of work found evidence consistent with these models, but often using

somewhat indirect measures of economic interests, using education as a measure of skill, for example

(Scheve and Slaughter, 2001; O’Rourke et al., 2001; Mayda and Rodrik, 2005). While education

may serve as a reasonable proxy for an individual’s skill level, it also serves as a reasonable proxy

for a number of other quantities: the likelihood of being exposed to cues from political elites (Zaller,

1992), exposure to basic economic principles (Hainmueller and Hiscox, 2006), political knowledge

(Delli Carpini and Keeter, 1996), and cosmopolitanism and attitudes towards outgroups more gen-

22

erally (Coenders and Scheepers, 2003).

As a result, a later wave of work employing more fine-grained measures of economic interests has

tended to find weaker relationships with material economic interests, and stronger relationships with

more psychological constructs – consistent with the political behavior literature more broadly, which

tends to find relatively little support for personal pocketbook-based models of political behavior (e.g.

Sears et al., 1980; Feldman, 1982; Kinder, Adams and Gronke, 1989. Herrmann and Shannon (2001)

show trade attitudes are shaped by neorealist and Rawlsian ideas, while Wolfe and Mendelsohn

(2005) point to the role of values and ideology. Mansfield and Mutz (2009) suggest that trade

attitudes are sociotropic (implicating beliefs about trade’s effects on the country as a whole) rather

than egotropic (implicating beliefs about its effects on one’s own pocketbook), consistent with Ellison,

Lusk and Briggeman (2010) and Naoi and Kume (2011), who point to the centrality of altruism and

sympathy, respectively. Along these lines, Margalit (2012) points to cultural factors, Kaltenthaler

and Miller (2013) to the role of social trust, Johnston (2013) to cognitive style, Rathbun (2016) to

beliefs about liberty, Wu (2019) to beliefs about the government’s role in the economy, Jedinger and

Burger (2020) to authoritarianism and social dominance orientation, Brutger and Rathbun (2021)

about fairness, and so on. Similar patterns have been detected in attitudes towards other types of

foreign economic policies as well, such as immigration (e.g. Hainmueller and Hiscox, 2010; Newman,

Hartman and Taber, 2014; Bloom, Arikan and Courtemanche, 2015; Dinesen, Klemmensen and

Nørgaard, 2016; Kustov, 2021).

IPE scholars have sought to explain these findings in three ways. One is to point to the challenges

involved in measuring self-interest, particularly when our measures of self-interest in these studies

are often less fine-grained than the measures of dispositional characteristics (Owen and Walter, 2017;

Owen and Johnston, 2017), and where the relevant economic interests might be at the community-

level rather than the individual-level (Broz, Frieden and Weymouth, 2021). Another is to flip the

causal arrow around, and show that the dispositional characteristics that seem to powerfully predict

political behavior are themselves shaped by material economic forces. Ballard-Rosa et al. (2020),

for example, show that individuals living in areas of Great Britain highly affected by economic

shocks from increased import competition from China displayed higher levels of authoritarianism.

Colantone and Stanig (2018) use a similar identification strategy to show that import competition

in Western Europe causes increases in supports for nationalist, isolationist, and radical-right parties.

Margalit and Shayo (2020) find that randomly assigning individuals to invest in the stock market

23

causes rightward shifts in their socioeconomic values.

A third is to point to the role of the information environment. The most prominent cases where

political attitudes do map onto personal self-interest — smokers opposing smoking bans (Citrin et al.,

1997), voters supporting opioid treatment funding as long as the clinics aren’t located near their

home (De Benedictis-Kessner and Hankinson, 2019) — are those where the issues are highly salient,

and where pocketbook calculations are relatively straightforward. Foreign economic policy issues

like trade, on the other hand, are more complex and often less salient. It is harder for a recently

unemployed individual to attribute their job loss to increased import competition as a result of lower

tariff rates than it is a smoker to attribute an increase in cigarette prices to government anti-smoking

policy (Guisinger, 2017). If less than 40% of Americans can define what free trade is (Delli Carpini

and Keeter, 1996, 70), it is also likely that how they think about trade may be more shaped by

questions of ethnocentrism and perceptions of national relative gains (Mutz and Kim, 2017) than

the nuances of Stolper-Samuelson.

Political scientists have therefore turned to experimental methods to study how information

causally shapes trade preferences. Guisinger (2017) find that citizens have misperceptions about

trade (e.g. who America’s most important trading partner is), and that once these misperceptions

are corrected, support for free trade grows (though see Flynn, Horiuchi and Zhang, 2020). Bearce and

Tuxhorn (2017) show that individuals’ monetary preferences become more aligned with their material

interests once they are taught how monetary policy operates. Rho and Tomz (2017) and Jamal

and Milner (2019) show that respondents are more likely to espouse trade preferences consistent

with their material interests if they are presented with information about trade’s distributional

effects, while Bearce and Moya (2020) find that providing respondents with information about

trade’s employment effects is more effective in bolstering support for free trade than providing

information about trade’s benefits for consumers. Schaffer and Spilker (2019) find that randomly

assigning individuals to receive information about how trade affects them personally has a larger

effect than assigning individuals to receive information about how trade affects their country.

These developments in the IPE literature reinforce the importance of incorporating theories of

the media into our understanding of public opinion in foreign policy issues, since the media represents

an important source through which individuals receive information about policy issues. At the same

time, however, they also raise broader philosophical questions about the underlying data-generating

processes in the real world that the experiments are simulating. Studying what public attitudes

24

would look under fully informed public opinion is valuable for normative reasons (Althaus, 1998),

but these studies are perhaps better understood as telling us what public opinion about trade would

be like in a world where citizens were all taught the precepts of trade theories, rather than probing

the origins of trade preferences themselves. Moreover, the psychological traits noted above that

shape trade preferences seem to operate equally strongly among more and less informed individuals,

such that it is not the case that information makes the effects of dispositional traits go away (Kertzer

et al., 2021). Further engagement with theoretical frameworks from political psychology will thus

likely enrich our understanding of the microfoundations of public opinion about foreign economic

issues, similar to how it has enriched our understanding in public opinion about security issues.

5 Future directions

For both substantive and methodological reasons, the public opinion literature in foreign policy lit-

erature continues to grow at a remarkable rate. This has been reflected in a surge of research on

the areas identified above: the structure of foreign policy attitudes, the domestic politics of interna-

tional security (including the democratic peace, audience costs, rally around the flag effects, against

type models, and public opinion about nuclear weapons), and the microfoundations of international

political economy issues like trade.

Despite this growth, there remain a number of areas in particular where more work is sorely

needed, three of which I discuss here. First, much of the existing research on public opinion in

foreign policy relies on evidence from a relatively small number of western industrialized democracies

(Narang and Staniland, 2018). There’s been far less work understanding public opinion in foreign

policy in non-democratic, hybrid, or transitional regimes (Fair, Kaltenthaler and Miller, 2013; Huang,

2015; Bell and Quek, 2018; Quek and Johnston, 2018; Weiss and Dafoe, 2019; Clary, Lalwani and

Siddiqui, 2021). This asymmetry is partially due to matters of data availability, and partially to the

presumption that public opinion is most worth studying in the contexts where it has the ability to

more directly influence policy outcomes. Yet recent research on authoritarian accountability suggests

that non-democratic governments are far more sensitive to public sentiment than political scientists

once presumed (e.g. Truex, 2016; Meng, Pan and Ping, 2017), suggesting the merit of studying

public opinion in non-democratic contexts as well.

Moreover, there are a variety of theoretical reasons to suppose that public opinion dynamics

25

may operate differently outside of the narrow set of western industrialized contexts that constitute

a plurality of the data sources utilized in many of our discipline’s top journals (Colgan, 2019; Levin

and Trager, 2019). Not only are the institutional contexts different (Narang and Staniland, 2018),

but so too are many of the assumptions we might have about the nature of public opinion itself.

For example, since much of the research on public opinion in foreign policy uses evidence from

the United States, political scientists tend to think of foreign policy as relatively less salient than

domestic political issues. In countries embroiled in territorial conflicts, however, the opposite is

true, and foreign policy issues often constitute the central political axis: in Israel, for example,

attitudes towards the Arab-Israeli conflict are as highly correlated with partisanship as partisanship

is with left-right political ideology in the United States (Yarhi-Milo, Kertzer and Renshon, 2018).

Similarly, Kleinberg and Fordham (2010, 691), note that tests of the Stolper-Samuelson theorem in

public opinion about trade tends to perform better in industrialized countries than in developing

ones. More generally, in countries that are highly dependent on trade, the dynamics of public opinion

about foreign economic policy may likely be quite different than in countries where trade makes up

a relatively small proportion of GDP, and trade may be more distant from citizens’ daily lives (e.g.

Kim and Cha, 2021).

Second, this curtailed geographic focus has also led to an asymmetric focus on public opinion

in sender states rather than in recipient states. We know much more about the microfoundations

of foreign aid donors’ preferences (Milner and Tingley, 2013; Dietrich, Hyde and Winters, 2019),

rather than foreign aid recipients’ preferences (Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood, 2014; Findley et al.,

2017; Alrababa’h, Myrick and Webb, 2020), or natives’ attitudes towards immigrants (Hainmueller

and Hopkins, 2015; Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux, 2017) rather than immigrants’ attitudes to-

wards the countries to which they’re migrating (Holland and Peters, 2020). There’s a considerable

amount of work on public opinion towards military interventions, but it largely focuses on domestic

support within the intervening country (e.g. Mueller, 1971; Larson, 2000; Gelpi, Feaver and Reifler,

2009) rather than of the targets of the intervention itself (Hirose, Imai and Lyall, 2017; Bush and

Prather, 2018; Dill, 2019; Mikulaschek, Pant and Tesfaye, 2020). This asymmetry means the public

opinion literature sometimes paints an image of the public as spectators watching foreign policy

uninterestedly from the sidelines, rather than as the players in the field, but this perhaps better

portrays the American experience than it does the dynamics of public opinion about foreign policy

writ large. Broadening the geographic scope of the public opinion literature in foreign policy can

26

help rectify this imbalance; there is more to public opinion about foreign policy than is dreamt of

by Americanists.

Third, a rich literature exists on the role of gender in public opinion about foreign policy. Much

of it focuses on better understanding the nature of the “gender gap” between men and women in

their support for the use of force (e.g. Conover and Sapiro, 1993; Togeby, 1994; Wilcox, Hewitt

and Allsop, 1996; McDermott and Cowden, 2001; Brooks and Valentino, 2011; Eichenberg, 2016;

Crawford, Lawrence and Lebovic, 2017); similar efforts have also been made to understand why

women in the United States are significantly less supportive of free trade than men are (Burgoon

and Hiscox, 2004; Mansfield, Mutz and Silver, 2015; Kleinberg and Fordham, 2018; Brutger and

Guisinger, 2021). Others focus on double standards in how male and female leaders (Croco and

Gartner, 2014; Post and Sen, 2020; Schwartz and Blair, 2020) or combat fatalities (Gartner, 2008;

Cohen, Huff and Schub, 2021) are treated. This literature is shedding new light on important

dynamics in public opinion, and should continue to be developed further. In comparison to the

robust literature on gender, however, there is relatively little research on the role of race in public

opinion about foreign policy – and the literature that does exist is predominantly (though not

exclusively) focused on race as it relates to the attitudes of majority-group members (e.g. Gartner

and Segura, 2000; Baker, 2015; Mutz, Mansfield and Kim, 2020), rather than the foreign policy

preferences of minority group members themselves (Green-Riley and Leber, 2021). As international