<PAHO DOCUMENT IDENTIFICATION No>

Caribbean

Pharmaceutical Policy

Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy

OC

Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy

Washington, D.C., 2013

PAHO HQ Library Cataloguing-in-PublicaƟ on Data

************************************************************************

Pan American Health OrganizaƟ on. Caribbean Community.

Caribbean PharmaceuƟ cal Policy. Washington, DC : PAHO, 2013.

1. Drug and NarcoƟ c Control. 2. Health Policy, Planning and Management. 3. NaƟ onal Drug Policy.

4. Caribbean. I. Title. II. CARICOM.

ISBN 978-92-75-11807-8 (NLM classifi caƟ on: QV55)

The Pan American Health OrganizaƟ on welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or trans-

late its publicaƟ ons, in part or in full. ApplicaƟ ons and inquiries should be addressed to the Department

of Knowledge Management and CommunicaƟ ons (KMC), Pan American Health OrganizaƟ on, Washington,

D.C., U.S.A. ([email protected]g). The Department of Health Systems and Services (HSS) will be glad to

provide the latest informaƟ on on any changes made to the text, plans for new ediƟ ons, and reprints and

translaƟ ons already available.

© Pan American Health OrganizaƟ on, 2013. All rights reserved.

PublicaƟ ons of the Pan American Health OrganizaƟ on enjoy copyright protecƟ on in accordance

with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright ConvenƟ on. All rights are reserved.

The designaƟ ons employed and the presentaƟ on of the material in this publicaƟ on do not imply

the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Pan American Health Orga-

nizaƟ on concerning the status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authoriƟ es, or concerning the

delimitaƟ on of its fronƟ ers or boundaries.

The menƟ on of specifi c companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they

are endorsed or recommended by the Pan American Health OrganizaƟ on in preference to others of a simi-

lar nature that are not menƟ oned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are

disƟ nguished by iniƟ al capital leƩ ers.

All reasonable precauƟ ons have been taken by the Pan American Health OrganizaƟ on to verify the

informaƟ on contained in this publicaƟ on. However, the published material is being distributed without

warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpreta

Ɵ on and use of the

material lies with the reader. In no event shall the Pan American Health OrganizaƟ on be liable for damages

arising from its use.

iii

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................... v

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................................................... vii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. ix

1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................1

1.1 Background and context ...................................................................................................1

1.2 Health and the pharmaceutical situation in the Caribbean ...............................................3

1.3 Proposal for a model national medicines policy and technical advisory group .................4

1.4 Overview of the pharmaceutical situation .........................................................................6

2. GOAL, PRINCIPLES AND VALUES OF THE POLICY...........................................................11

2.1. Goal of the policy ........................................................................................................... 11

2.2. Principles and values of the policy ................................................................................ 11

3. OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES .........................................................................................13

3.1. Objectives ......................................................................................................................13

3.1.1. Pharmaceutical policy scope ................................................................................13

3.1.2. Regulatory framework ...........................................................................................13

3.1.3. Access ..................................................................................................................13

3.1.4. Rational use of medicines .....................................................................................14

3.2. Strategies ......................................................................................................................14

3.2.1. Pharmaceutical policy scope ................................................................................14

3.2.2. Regulatory framework ...........................................................................................15

3.2.3. Access ..................................................................................................................16

3.2.4. Rational use of medicines .....................................................................................17

4. MECHANISMS FOR IMPLEMENTATION, MONITORING AND EVALUATION .....................19

4.1. Responsibility and oversight structure ...........................................................................19

4.2. Strategies for implementation ........................................................................................20

4.3. Reporting mechanism ....................................................................................................20

4.4. Financing .......................................................................................................................20

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS ....................................................................................................21

REFERENCES ...........................................................................................................................23

iv

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

ANNEX I. Former Technical Advisory Group on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights .....23

ANNEX II. Executive Summary - CARICOM Regional Assessment of Drug Registration and

Regulatory Systems ...................................................................................................................25

ANNEX III. Executive Summary - Assessment of Patent and Related Issues and

Access to Medicines in CARICOM and the Dominican Republic - HERA Final Report –

31 December 2009 .....................................................................................................................35

ANNEX IV. Glossary of Terms ....................................................................................................43

ANNEX V. Development of the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy .............................................49

ANNEX VI. Outline of the Implementation Plan for the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy ........51

ANNEX VII. Terms of Reference - CARICOM Expanded Technical Advisory Committee on

Pharmaceutical Policiy (TECHPHARM) .....................................................................................53

ANNEX VIII. Roadmap for Development of the Pharmaceutical Policy .....................................59

v

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The development of this document was made possible through the invaluable contributions of a

number of individuals and organisations.

The process was coordinated by the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Technical Advisory

Group (TAG) on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights. The draft Caribbean Pharmaceutical

Policy (CPP) was presented in July 2010 at a workshop on Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policies

held at the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) Offi ce of

Caribbean Program Coordination OCPC) in Barbados. The following TAG members contributed

to the draft policy:

Adriana Mitsue Ivama Brummell, Sub-Regional Advisor, Medicines and Health

Technologies, PAHO/WHO);

Francis Burnett, Managing Director, Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

Pharmaceutical Procurement Service;

Lucette C. M. Cargill, Head of Unit, Caribbean Public Health Agency Drug Testing

Laboratory (formerly the Caribbean Regional Drug Testing Laboratory);

Rudolph Cummings, Programme Manager, Health Sector Development, CARICOM Secretariat;

Maryam J. Hinds, Director, Barbados Drug Service;

Miriam A. Naarendorp, Pharmacy Policy Coordinator, Ministry of Health, Suriname; and

Princess Thomas Osbourne, Director of Standards and Regulation; Ministry of Health

(MOH), Jamaica.

The following persons also participated:

Anthony K. Cyrus, Pharmacy Inspector, Ministry of Health, Grenada;

Damian Cohall, Lecturer in Pharmacology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of the

West Indies (UWI);

David L. Crawford, Drug Inspector, Barbados Drug Service;

Elizabeth M-R Ferdinand, Chief Medical Offi cer (acting), Ministry of Health, Barbados;

Eugenie Brown-Myrie, Dean, College of Health Sciences, University of Technology,

Jamaica;

Evelyn B. Davis, Pharmacy Educator, T.A. Marryshow Community College, Grenada;

Gracia A. Wheatley, Chief of Drugs and Pharmaceutical Services, Ministry of Health and

Social Development, British Virgin Islands;

Lesia Proverbs, Pharmacy Educator, Division of Health Science, Barbados Community

College;

Louisa Stuwe, Intern, PAHO/WHO;

Marthelise G. Eersel, Director of Health, Ministry of Health, Suriname;

Pamela E. Payne-Wilson, Assistant Director, Barbados Drug Service;

Patrick Martin, Chief Medical Offi cer, Ministry of Health, Saint Kitts and Nevis;

Rian M Extavour, Chair, Education Committee, Caribbean Association of Pharmacists;

St Clair A. Thomas, Chief Medical Offi cer, Ministry of Health, Saint Vincent and the

Grenadines; and

Robert C. Verhage, Consultant, Evaluation, Health Research for Action European

Community/African Caribbean and Pacifi c States/World Health Organization Partnership

on Pharmaceutical Policies.

Based on the workshop’s recommendations, the CPP was reviewed and edited by A. Ivama

Brummell, Nelly Marin (former PAHO/WHO advisor on pharmaceutical policies) and Rian M.

Extavour, with the collaboration of Maryam J. Hinds, Patrick Martin, Damian Cohall, M. Valdes

(PAHO/WHO), Murilo Freitas (PAHO/WHO), Irad Potter and Gracia A. Wheatley.

This document has been produced with the fi nancial assistance of the European Union and the technical support of the Pan

American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). The views expressed herein are those of the authors

and can therefore in no way be taken to refl ect the offi cial opinion of the European Union or the PAHO/WHO.

vii

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ACP African, Caribbean and Pacifi c Group of States

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

CARICOM Caribbean Community

CARIFORUM Caribbean Forum of African, Caribbean and Pacifi c States

CARIPROSUM Caribbean Regional Network of Pharmaceutical

Procurement and Supply Management Authorities

CARPHA Caribbean Public Health Agency

CCH III Caribbean Cooperation in Health Initiative, Phase III

CMOs Chief Medical Offi cers

COHSOD Council for Human and Social Development

CPP Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy

CRDTL Caribbean Regional Drug Testing Laboratory

CSME CARICOM Single Market and Economy

DR-CAFTA Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement

DTL Drug Testing Laboratory

EMA European Medicines Agency

EML Essential medicines list

EPA Economic Partnership Agreement

EU European Union

GMP Good manufacturing practices

HERA Health Research for Action

HIV/AIDS Human immunodefi ciency virus/acquired immunodefi ciency

syndrome

IPRs Intellectual property rights

MOH Ministry of Health

MRA Medicines regulatory authority

NCDs Non-communicable diseases

NMP National medicines policy

NRA National Regulatory Authority

OCPC Offi ce of Caribbean Program Coordination

OECS Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

PAHO Pan American Health Organization

PANCAP Pan Caribbean Partnership against HIV and AIDS

PANDRH Pan American Network for Drug Regulatory Harmonization

PPS Pharmaceutical Procurement Service

SADC Southern African Development Community

STGs Standard treatment guidelines

TAG Technical Advisory Group

TECHPHARM CARICOM Expanded Technical Advisory Committee on

Pharmaceutical Policy

viii

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

TRIPS Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

WHO World Health Organization

WTO World Trade Organization

ix

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Every human being is entitled to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health

conducive to living in dignity. Access to health care, which includes access to essential medicines,

is a prerequisite for realising that right. National medicines expenditures, as a proportion of total

health expenditures, currently range from 7% to 66% worldwide.

In the Caribbean, the implementation of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas and the

establishment of the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME) provide a favourable

environment for regional integration. However, there are challenges in the area of health, given the

health situation, geography, limited human resources and continued migration. At the same time,

the tourism sector is being challenged by poor sanitation, untreated sewage that may damage

beaches, food-borne disease outbreaks in public places, the threat of natural disasters and the

need to mount an effective, rapid response to manage and control epidemics. There is a need to

focus on achieving a strong, comprehensive and integrated public health response through health

environment strategies that address these priority areas.

Recognising the challenge of ensuring sustained access to adequate quality medicines at

affordable prices, the CARICOM Ministers of Health, at the Tenth Meeting of the Council for

Human and Social Development (COHSOD) (April 2003), mandated the establishment of a

Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). TAG,

by means of a regional assessment of drug regulatory and registration systems and a regional

assessment of patent and related issues and access to medicines in CARICOM countries and the

Dominican Republic, sought to assess the current situation and to propose solutions for improving

the situation with respect to medicines. Complementary to these studies, PAHO/WHO published

a report on the pharmaceutical situation in the Caribbean in 2007, with the participation of 13

Caribbean countries.

At the Eighteenth Meeting of the Caucus of CARICOM Health Ministers, held in 2009 in

Washington, D.C., the ministers supported an accelerated approach to a series of projects related

to improving quality of life, establishing partnerships in pharmaceutical policies, addressing

intellectual property rights, and strengthening the functions of the health sector, among others.

The Caucus also urged that there be coordinated collaboration among the Chief Medical Offi cers

(CMOs), the CARICOM Health Desk and PAHO on the issue.

x

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

Based on the fi ndings of the above-mentioned studies and within the framework of the

Caribbean Cooperation in Health Initiative, Phase III (CCH III), the development of a Caribbean

Pharmaceutical Policy (CPP) was proposed. Earlier, in 1999, a draft Model National Medicines

Policy had been developed after a series of steps in that direction. Although the document was

updated in 2001, it was never offi cially adopted. This draft served as the main starting point for

developing the current CPP proposal. At a workshop convened in Barbados on 5–6 July 2010, a

proposal prepared by TAG was discussed with participation from the main regional and national

stakeholders, including representatives of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS),

the former Caribbean Regional Drug Testing Laboratory (CRDTL; now the Caribbean Public

Health Agency Drug Testing Laboratory [CARPHA/DTL]) and Caribbean Ministries of Health and

universities.

The proposal for the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy was presented at the Eighteenth

Meeting of Chief Medical Offi cers (CMOs) on 19 May 2010 and at the Nineteenth Meeting of the

Caucus of CARICOM Health Ministers in September 2010. The ministers agreed that a decision

should be taken on this matter at the next COHSOD meeting, to be held in April 2011, when the

policy was fi nally approved.

The goal of the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy is to guide Caribbean countries in ensuring:

• Access: equitable access to, availability of and affordability of essential medicines;

• Quality: quality, safety and effi cacy of all medicines; and

• Rational use: therapeutically sound and cost-effective use of medicines by health

professionals and consumers.

The regional pharmaceutical policy is guided by the main principle of access to medicines

as a human right. Additionally, it is guided by the values and principles of public health, with an

emphasis on the renewed Primary Health Care strategy.

The policy has four main areas, namely:

• Pharmacy policy scope;

• Regulatory framework;

• Access; and

• Rational use of medicines.

The CPP encompasses pharmaceutical products and services and related issues, with

objectives as follows.

Pharmaceutical policy scope

• Support collaboration mechanisms and develop regional guidelines in key areas of

implementation of the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy.

• Promote the development and management of human resources in the areas of

the pharmaceutical policy.

xi

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

• Promote the use of evidence in decision-making for the development, implementation

and assessment of pharmaceutical policies, both at the sub-regional and national

levels.

Regulatory framework

• Develop a sub-regional regulatory framework for medicines and strengthen

the collaboration among Caribbean countries to ensure the performance of the

essential components of medicines regulation.

Access

• Strengthen the collaboration among the national pharmaceutical systems and

promote and support the development and implementation mechanisms for joint

negotiation of medicines procurement.

• Develop a sub-regional mechanism to strengthen patent examination systems with

a “pro–public health” approach and support the countries’ efforts to promote and

protect public health and access to medicines, in order to take advantage of Trade-

Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) fl exibilities in conformity

with the Doha Declaration on Public Health.

Rational use of medicines

• Develop a sub-regional strategy and work plan for strengthening the rational use

of medicines in the Caribbean as part of the pharmaceutical policy.

Mechanisms for implementation, monitoring and evaluation

An implementation plan with indicators for monitoring and evaluation will be

developed. The proposed mechanism, with responsibility for overseeing policy

implementation, includes the establishment of the Expanded Technical Advisory Group

on Pharmaceutical Policy (TECHPHARM). The policy establishes TECHPHARM and

its responsibilities for overseeing the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of

the CPP. These responsibilities are shared with the national health authorities and

stakeholders from the Caribbean, with technical and fi nancial support from the

CARICOM Secretariat and PAHO/WHO.

TECHPHARM will assess the progress of the implementation of the policy in an

annual report to the Ministers of Health, embedded in the reporting mechanisms of

the CMOs regarding CCH III implementation. It is necessary to establish a sustainable

fi nancing mechanism for the proposed policy, which provides guidelines for regional

donors’ support in a synergistic way.

The CPP will be an integral part of policies developed by Caribbean states and,

to the extent possible, will be incorporated into other policies related to public health.

1

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

1. INTRODUCTION

Health is a fundamental human right indispensable for the exercise of other human rights. Every

human being is entitled to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health conducive

to living a life in dignity. The realisation of the right to health may be pursued through numerous,

complementary approaches, such as the formulation of health policies, the implementation of

health programmes, or the adoption of specifi c legal instruments. Moreover, the right to health

includes certain components which are legally enforceable (1).

Access to health care, which includes access to essential medicines, is a prerequisite for

realising that right. It is part of the governance and steering role of the state to ensure the fulfi lment

of

the right to health. National medicines expenditures, as a proportion of total health expenditures,

currently range from 7% to 66% worldwide, and proportions are higher in developing countries

(24%–66%) than in developed countries (7%–30%) (2).

In accord with the mandates of the Tenth Meeting of COHSOD and the Eighteenth Meeting of

the Caucus of CARICOM Health Ministers, a Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy (CPP) has been

proposed and approved in order to promote a sub-regional policy framework and to support and

facilitate the development of individual pharmaceutical policies in the Caribbean countries. It aims

to support the sustainability of the progress achieved, to date, and to address remaining gaps as

well as new challenges.

1.1 Background and context

The Caribbean includes countries and territories with different political structures and status,

as follows:

• Republics: Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Suriname;

• Republics within the Commonwealth of Nations: Dominica, Guyana, Trinidad and

Tobago;

• Independent countries that are part of the Commonwealth: Antigua and Barbuda,

the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, Saint

Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines;

• UK Overseas Territories: Anguilla, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman

Islands, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands;

• Entities of the Kingdom of the Netherlands: Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Sint Maarten,

Special Municipalities of the Netherlands;

• French Overseas Territories of the Americas: Guadeloupe, Guyana, Martinique,

Saint Martin; and

2

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

• United States (US) Overseas Territories: Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, US Virgin

Islands.

Not only is there diversity in political status and language, Caribbean countries also have

different legal systems: most English-speaking territories operate under a common law legal

system, while the other territories tend to operate under a civil law system. Most territories are

considered small developing states, due to their geographic size and population size as well as

the scale of their respective economies.

Caribbean countries have been aligned to a number of regional integration mechanisms and

associations. In this context, sub-regional collaboration is crucial to respond to a set of persistent

challenges, including the need for state reforms as well as increased pressure due to globalisation

and the economic recession. These challenges are refl ected in the establishment of the Caribbean

Community (CARICOM)

1

and the steps taken towards the implementation of the Revised Treaty

of Chaguaramas, establishing the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME) (2001). Article

6 of CSME outlines a set of objectives that include improved standards of living and work, more

effi cient operation of common services and activities, full employment of labour and other factors of

production, and accelerated, coordinated and sustained economic development and convergence.

Article 17 addresses the promotion of human and social development and the development of

coordinated policies and programmes to improve the living and working conditions of workers. In

the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, allowances also have been made for new issues such as

e-commerce, government procurement, trade in goods from free zones, free circulation of goods

and the right of free movement of persons (3).

The 15 CARICOM countries and the Dominican Republic make up the Caribbean Forum of

African, Caribbean and Pacifi c States (CARIFORUM). These countries, together with countries

of Africa and the Pacifi c, constitute the ACP (African, Caribbean and Pacifi c Group of States)

countries that negotiated an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with the European Union

(EU) in April 2004.

2

The framework for ACP-EU relations is centred on economic development,

reductions in and eventual eradication of poverty and the smooth and gradual integration of ACP

states into the global economy (4).

In addition to CARIFORUM, Caribbean countries participate in several other sub-regional

integration or strategic development groups, including the Association of Caribbean States, the

Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), the Rio Group, the Union of South American

Nations, the Central American Integration System and the Association of Small Island States.

These collaborations lead to opportunities for cooperation among the countries in areas related

to health and development.

1

a) CARICOM Member States: Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica,

Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago; and

b) CARICOM associate members: Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands and Turks and Caicos Islands.

2

The countries are as follows: Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana,

Haiti, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago. The

EPA was signed on 15 October 2008 by each of these countries with the exception of Guyana (which signed on 20 October

2008) and Haiti (which signed on 11 December 2009).

3

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

1.2 Health and the pharmaceutical situation in the Caribbean

According to PAHO/WHO (5):

“given the health situation, the geography, the lack of human resources and continued

migration, health challenges in the Caribbean require reviews of the incomplete agendas

with regard to malaria, TB, leprosy, as well as the epidemic of non-communicable diseases.

At the same time, the tourism sector is being challenged by poor sanitation, untreated

sewage that may damage beaches, food borne disease outbreaks in public places, the

threat of natural disasters, and inadequate capacity to mount an effective, rapid response

to manage and control epidemics. As such, there is the need for the Caribbean to focus on

achieving a strong, comprehensive and integrated public health response through Health

Promotion Strategies that address these priority needs”.

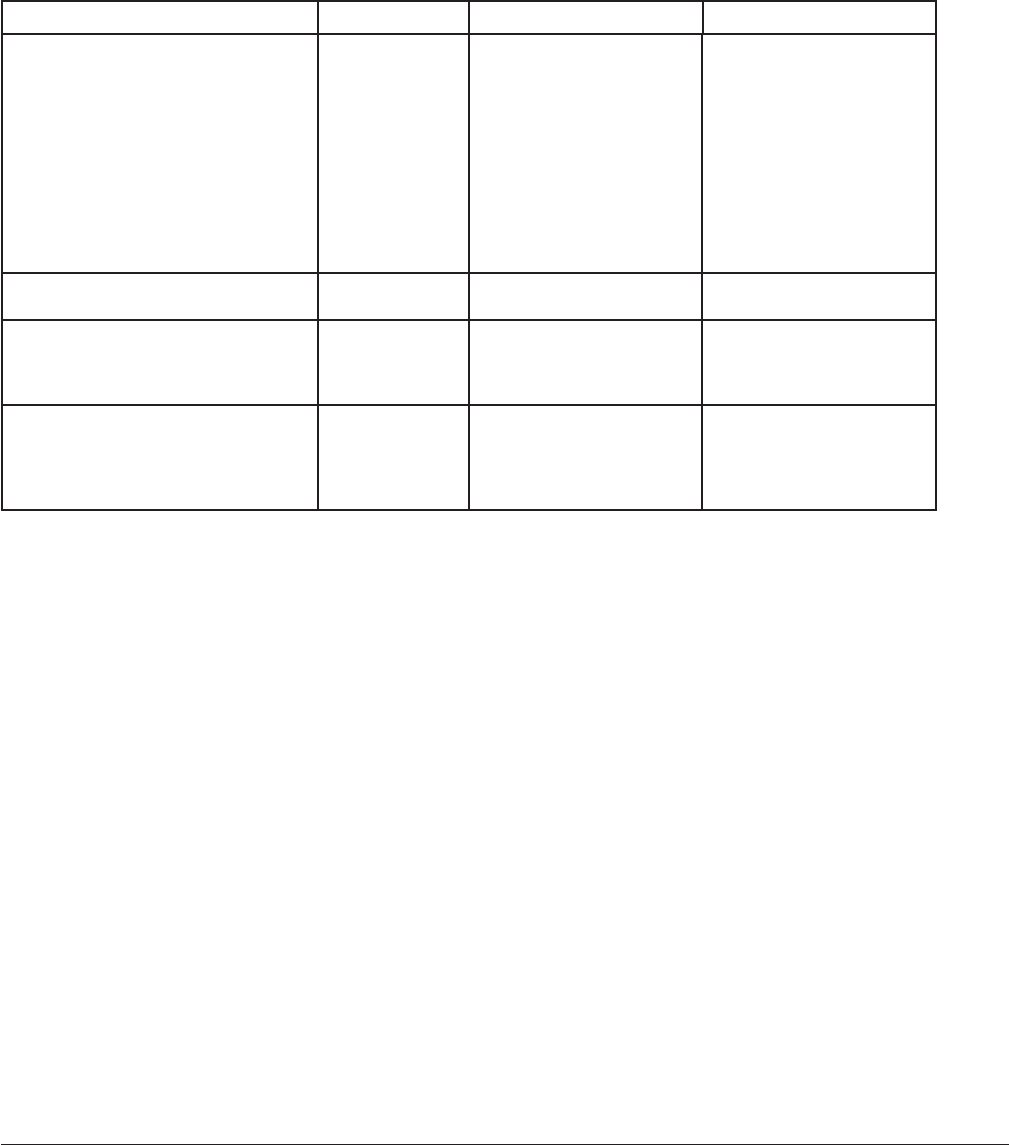

Figure 1. Leading causes of mortality in the Caribbean (2006)

Source: PAHO/WHO (6)

Over the past few decades, death rates in the Caribbean sub-region have been gradually

decreasing. Figure 1 shows that the French Departments of the Americas have the lowest mortality

rates, whereas Haiti has the highest. The other countries are similar in their mortality profi les.

Between 1980 and 2000, the leading cause of mortality across all ages in the English-speaking

Caribbean was ischemic heart disease, followed by cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus,

other heart diseases and hypertension. These conditions accounted for 47% of deaths in 1980

and 51% in 2000. Approximately 15%–20% of adults have diabetes, and about 20%–30% have

hypertension. Problems related to these major non-communicable diseases (NCDs) represent

the largest expenditures in national medicines budgets. The situation is similar in the non-English-

speaking countries.

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

The Caribbean

French Departments

Larger Islands

Barbados and OECS

Mainland

HaiƟ

Rates per 100,000 pop.

CommDisease

Neoplasms

Circulatory

Ext. Causes

Other

4

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

Overall, NCDs are the leading cause of death. They share common underlying risk factors,

namely unhealthy eating habits, physical inactivity, obesity, tobacco and alcohol use and inadequate

utilisation of preventive health services. This situation suggests that providing medicines alone is

not enough; a different and more comprehensive approach is required.

During the period 2004–2010, the WHO/EU/ACP Partnership on Pharmaceutical Policies was

an important source of fi nancing for the technical cooperation of CARICOM countries and the

Dominican Republic

3

through PAHO/WHO.

1.3 Proposal Model National Medicines Policy and Technical Advisory

Group

In 1999, a draft Model National Medicines Policy was developed following a series of steps in

that direction. First, a consultative workshop took place in May 1999 in Jamaica under the auspices

of the CARICOM Secretariat. As stated in the Introduction, the model policy resulted from the

pooling of opinions of key role players, primarily chief pharmacists of the CARICOM countries as

well as representatives of the Eastern Caribbean Drug Service (ECDS) (since renamed the OECS

Pharmaceutical Procurement Service [OECS/PPS]), the CARICOM Secretariat and PAHO/WHO.

4

Although the document was updated in 2001, it was never offi cially adopted. The draft model

served as the main starting point for developing the proposal for the Caribbean Pharmaceutical

Policy. Recognising the challenge of ensuring sustained access to adequate quality medicines

at affordable prices, the CARICOM Ministers of Health, at the Tenth Meeting of COHSOD in

April 2003, mandated the establishment of a Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Trade-Related

Intellectual Property Rights (see Annex I). TAG, by means of a CARICOM regional assessment of

drug regulatory and registration systems (7) and an assessment of patent and related issues and

access to medicines in CARICOM and the Dominican Republic (8), sought to assess the current

situation with respect to medicines and to propose improvements for the situation.

The two above-mentioned assessments were part of the TAG mandate. Annexes II and III,

respectively, present executive summaries of these two studies, which were commissioned by the

CARICOM Secretariat, conducted by Health Research for Action (HERA), technically supported

by PAHO/WHO and fi nanced by the Pan Caribbean Partnership against HIV and AIDS (PANCAP)

and the World Bank.

Complementary to these studies, PAHO/WHO published a report in 2010 on the pharmaceutical

situation in the Caribbean, with the participation of 13 Caribbean countries (9).

3

The agreement for this project was signed on 7 March 2004. In the Caribbean, technical cooperation is provided by PAHO/WHO

through its Offi ce of Caribbean Program Coordination (OCPC). The original duration of the project was fi ve years (until

September 2009), but a “non-cost extension” was received and the project continued until September 2010. In addition to the

mandates from PAHO/WHO, project activities were guided by sub-regional mandates and country priorities.

4

The CARICOM Draft Model National Medicines Policy (2001 version) is an unpublished document.

5

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

At the Eighteenth Meeting of the Caucus of CARICOM Health Ministers, held in September

2009 in Washington, D.C., the ministers, with respect to PAHO’s Regional Strategic Framework,

supported an accelerated approach to a series of projects related to improving quality of life,

establishing partnerships in pharmaceutical policies, developing a pro–public health approach to

intellectual property rights, and strengthening the functions of the health sector, among others.

The Caucus also urged that there be coordinated collaboration among the CMOs, the CARICOM

Health Desk and PAHO on the issue. The proposal for the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy was

presented on 19 May 2010, at the Eighteenth Meeting of Chief Medical Offi cers, and in September

2010 at the Nineteenth Meeting of the Caucus of CARICOM Health Ministers in Washington, D.C.

The ministers agreed that a decision would be taken at the Twenty-First Meeting of COHSOD in

April 2011; at that meeting, the policy was approved.

There have also been efforts to contribute to and achieve the goals established by the

Declaration of Port of Spain (2007), one of which is that, by 2012, 80% of people with NCDs would

receive quality care and have access to preventive education based on regional guidelines (10).

Therefore, it is necessary to guarantee access to high-quality and safe medicines and to promote

their rational use.

In 2009, the Caribbean Cooperation in Health Initiative, Phase III (CCH III), Investing in Health

for Sustainable Development, was adopted by the Ministers of Health. According to the CCH

III, one of the expected results related to the strategic objective of ensuring that health services

respond effectively to the needs of the Caribbean people is improvements in access to safe,

affordable and effi cacious medicines (11).

One of the areas for joint collaborative action is to support the design and implementation of

a Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy and mechanisms to enhance access, quality and rational use

of medicines in the Region. In the same way, one expected result at the national level would be

improving access to safe, affordable and effective medicines and their rational use. This document

represents the mandate for developing the pharmaceutical policy and its components at both the

sub-regional and national levels (11).

The Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA) was established by a CARICOM

intergovernmental agreement in June 2011, with the following objectives:

a) to promote the physical and mental health and wellness of people within the Caribbean;

b) to provide strategic direction in analysing, defi ning and responding to public health priorities

of the Caribbean Community;

c) to promote and develop measures for the prevention of disease in the Caribbean;

d) to support the Caribbean Community in preparing for, and responding to public health

emergencies;

e) to support solidarity in health, as one of the principal pillars of functional cooperation in the

Caribbean Community; and

6

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

f) to support the relevant objectives of the CCH as approved by the Council. The Caribbean

Regional Drug Testing Laboratory (CRDTL)

5

will become part of CARPHA.

1.4 Overview of the pharmaceutical situation

A variety of sources have been used to present the information in this section, including a

PAHO/WHO assessment of the pharmaceutical situation in Caribbean countries (9), based on the

responses of 13 countries to a WHO questionnaire; a regional assessment of drug registration

and regulatory systems in CARICOM Member States and the Dominican Republic (7); and a

regional assessment of patent and related issues and access to medicines in CARICOM Member

States and the Dominican Republic (8).

6

The results show that progress has been made in six

areas:

• National Medicines Policy;

• Regulatory System;

• Medicines Supply System,

• Medicines Financing;

• Production and Trade; and

• Essential Medicines and Rational Use.

The main results in each of these areas related to CARICOM members and the Dominican

Republic are highlighted in this document.

According to PAHO/WHO, the number of countries with a national medicines policy (NMP)

increased from three in 2003—with only two of them offi cially adopted—to seven in 2007, with

four offi cially adopted. In the 2009 assessments commissioned by CARICOM, seven of the 16

countries included had an NMP, but only three of them had been offi cially adopted. In addition,

only two countries declared that intellectual property and access to medicines were covered in

their respective NMPs. Of the two countries reporting that they had a written policy on intellectual

property rights (IPRs), neither reported having a policy on pharmaceutical innovation. The data

suggest that special attention has to be given to:

1) the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the existing policies; and

2) the development of a sub-regional pharmaceutical policy.

At the same time, these policies need to address aspects related to access to medicines,

IPRs and innovation and adopt a clear position on access to pharmaceuticals.

5

The Caribbean Regional Drug Testing Laboratory was established through an intergovernmental agreement among members of the

Caribbean Community; since the establishment of CARPHA, the laboratory has been renamed the Drug Testing Laboratory

(DTL).

6

The two regional surveys commissioned by the CARICOM Secretariat and conducted by Health Research for Action (HERA) were

part of the mandate of the Technical Advisory Group for Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TAG/TRIPS), which included

the 15 CARICOM Member States and the Dominican Republic. The executive summaries of the two CARICOM/HERA studies

are presented in Annexes II and III of this document.

7

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

According to PAHO/WHO (9), in 2003, only four countries reported that they had legal

provisions for the establishment of a medicines regulatory authority (MRA). By 2007, this number

had increased to 11. According to the CARICOM report (7), none of the existing legislation is

fully comprehensive. Even though progress can be observed with regard to several individual

components of the regulatory structure, it is a priority to strengthen the institutional capacity of

MRAs and, in particular, their technical capacity. This is important to ensure the performance

of several essential functions of medicines regulation, such as registration or marketing

authorisation, inspection and licensing of facilities and personnel, and marketing surveillance

and pharmacovigilance. In this regard, there is a need for a sub-regional regulatory framework

and a network among the MRAs to improve harmonisation and integration efforts as well as

collaboration.

According to the CARICOM report (7), seven of the countries studied have privately owned

pharmaceutical manufacturing plants that produce multi-source (generic) products only; four of

these countries have export capacity. Private sector pharmaceutical importers and/or wholesalers

are operating in 14 of the 16 countries, while all of the countries have private retail pharmacies

(ranging from one pharmacy in Montserrat to 2,812 in the Dominican Republic). In view of this

multitude of stakeholders and actors, it is necessary to establish a comprehensive regulatory

framework.

In the PAHO/WHO assessment (9), all participating Caribbean countries reported having

public sector procurement pooled at the national level. In 2003, in all seven responding countries,

one of the functions of the Ministry of Health was procurement of medicines. In 2007, this was the

case in 12 of the 13 responding countries (92%). The distribution function was performed by the

Ministry of Health in fi ve countries in 2003 and in seven countries in 2007. Three countries used

more than one procurement mechanism in both 2003 and 2007; one of them was through OECS/

PPS. The median total expenditure on medicines in the public sector in the Americas region (US$

34,087,493) was considerably higher than the expenditure in participating Caribbean countries

(US$ 4,000,000), but the median per capita/per year public expenditure was nearly twice as high

in the participating Caribbean countries (US$ 20.90) as in the Region of the Americas as a whole

(US$ 11.50). Factors to consider in conducting a comparative analysis include a country’s size

and, consequently, its scope of pharmaceutical marketing, the complexity of its health systems

and the effectiveness of its procurement mechanisms and negotiating capacity, including the use

of brand or generic medicines and levels of government subsidies for medicines.

The CARICOM report (7) stated that establishing an effective regional negotiation platform

for medicines requires that needs and benefi ts are clearly defi ned, political will is present and

a regional body can be established. With respect to these areas, it is necessary to strengthen

medicines procurement and supply systems, thereby ensuring sustainability and cost containment.

It is also important to strengthen collaborative mechanisms, such as the Caribbean Regional

Network of Pharmaceutical Procurement and Supply Management Authorities (CARIPROSUM),

and to work towards a sub-regional mechanism for pooled negotiations. Additional studies should

be conducted with regard to price and expenditure of medicines for supporting these proposed

activities.

Although the issue of implementation of TRIPS fl exibilities had been under discussion for

several years, only one country had included TRIPS fl exibility provisions in its legislation as of

2007. “Compulsory licensing” was under debate in four countries (57%) in 2003 and in 2007, but

8

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

only two countries (50%) had adopted this legal provision. In 2003, three countries reported that

they had discussed incorporating Bolar exceptions; none of the countries, however, reported

having such legal provisions in 2007. In 2007, the number of countries that had changed their

national legislation to implement the TRIPS Agreement and its fl exibilities was still minimal (9).

In 2009, according to the CARICOM assessment (8), all 16 countries under study had patent

acts. In seven of these countries, however, the acts were considered outdated, and in nine of

them the legislation was being reformed so that it would be TRIPS compliant. Hence, the study

considered that TRIPS fl exibilities were not well implemented in the region. Only three countries

permitted international exhaustion of IP rights and thus allowed parallel import” from the world

market. The other 13 countries permitted regional or national exhaustion, reducing their options

to purchase more affordable brands elsewhere in the world. No country, at that time, had enacted

the “30 August decision” or the “Article 31bis amendment”. Both could become relevant with

respect to the import and regional distribution of multi-source products in the future.

According to the study, the Dominican Republic was the only country that prohibited new use

or second use patents, whereas three countries explicitly allowed this so-called evergreening of

patents. Nine countries allowed experimental use, but only the Dominican Republic had an early

working or Bolar clause (allowing manufacturers of multi-source products to apply for medicine

registration before patent expiry). Seven countries permitted de minimis exceptions, which allow

travellers to import small amounts of patented medicines. The situation was better regarding

compulsory licensing, which is allowed in 12 countries and authorised in draft laws in two other

countries. However, seemingly these clauses have never been used for medicines. Additionally,

although all 16 Caribbean countries under study reported that they had a patent offi ce, only 10

reported that they processed patent applications and only two indicated that they carried out

substantive examinations of patent applications. Special attention should be given to this area, in

particular, to implement the Global Strategy on Intellectual Property Rights in the Caribbean and

to support Member States in implementing TRIPS fl exibilities (8).

The availability and utilisation of essential medicines lists (EMLs) and standard treatment

guidelines (STGs) increased in the Caribbean between 2003 and 2007. It would be useful to

obtain additional information regarding the utilisation of these tools and their impact on rational

use of medicines and, in this regard, to conduct more specifi c studies such as household surveys.

However, not enough progress has been achieved regarding the introduction of concepts related

to rational use of medicines in the curricula of health professions programmes in the Caribbean.

It is proposed that support be provided for the development of a sub-regional strategy for the

rational use of medicines (9).

The progress observed in 2007 was compared with the 2003 baseline data in the different

components of the Caribbean pharmaceutical sector (9). There is still a signifi cant amount of work

to be done to improve performance in these areas. The CARICOM report posits that a Regional

Medicines Policy needs to be developed, taking into account the ‘Model’ National Medicines

Policy developed by CARICOM in 1999 (8). The formulation of a regional quality assurance policy

(regulatory framework) is considered a critical part of the regional pharmaceutical policy to be

adopted by Member States. A secretariat should be established, as well as a strategic work plan

with funds secured for its implementation.

9

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

The second CARICOM study sheds light on the need to implement TRIPS intellectual property

fl exibilities related to public health and to study the possibility of establishing a model wherein

patent rights are granted and enforced for each designated country. This would allow each country

to retain fl exibilities and exceptions in order to protect public health and consumer interests.

Special attention is given to aspects of human resources, mainly due to current shortages and

high levels of rotation, the need to strengthen regulation of medicines and, possibly, the need to

establish a pool negotiation mechanism for procurement. All of these areas should be within the

framework of a regional pharmaceutical policy (8).

Based on the fi ndings of the above-mentioned studies and within the framework of CCH III,

the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy (CPP) has been developed with participation from the

main regional and national stakeholders, including representatives of OECS, CRDTL (now the

CARPHA Drug Testing Laboratory [CARPHA/DTL]) (12), and Caribbean Ministries of Health and

universities.

Considering the context of the work that has been conducted by TAG, in cooperation with the

PAHO/WHO Offi ce of Caribbean Program Coordination (OCPC) and funded by the WHO/EU/ACP

Partnership on Pharmaceutical Policies project, this document cannot cover the varied integration

mechanisms of all Caribbean countries. Hence, the document covers CARICOM Member States

and the Dominican Republic.

Annex IV of this document presents a glossary of terms related to the CPP, and Annex V describes

the development of the policy.

11

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

2. GOAL, PRINCIPLES AND VALUES OF THE

POLICY

2.1. Goal of the policy

The goal of the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy (CPP) is to guide Caribbean countries in

ensuring:

2.2. Principles and values of the policy

The sub-regional pharmaceutical policy is guided by the main principle that access to medicines

is a human right (1). Additionally, it is guided by the values and principles of public health, with an

emphasis on the renewed Primary Health Care strategy (13).

The pharmaceutical policy has to be integrated into national (health) policies or plans.

Pharmaceutical policies are part of the governance and steering role of the state and are among

the essential public health functions, including the six building blocks of well-functioning health

care systems identifi ed by WHO: a service delivery health workforce; information; medical

products, vaccines and technology; fi nancing; and leadership and governance (12). The

Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy will also be guided by sub-regional mandates, with particular

attention to the CCH III (11), the Declaration of Port of Spain (10) and the PAHO/WHO Sub-

regional Cooperation Strategy for the Caribbean (5).

To guide Caribbean countries to ensure:

• Access: equitable access, availability and affordability of essential medicines

• Quality: quality, safety and effi cacy of all medicines

• Rational use: therapeutically sound and cost-effective use of medicines by health

professionals and consumers

13

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

3. OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES

The priority areas, objectives and strategies related to the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy

have been identifi ed based on the fi ndings of the existing surveys, the recommendations of the

Eighteenth Meeting of the Caucus of CARICOM Health Ministers (held in Washington, D.C., in

September 2009) and the Eighteenth Meeting of Chief Medical Offi cers (held in Trinidad and

Tobago in March 2010), and discussions held during the sub-regional technical workshops.

3.1. Objectives

The CPP comprises four main areas, namely:

• Pharmaceutical policy scope;

• Regulatory framework;

• Access; and

• Rational use of medicines.

The policy encompasses pharmaceutical products and services and related issues, with

objectives as follows.

3.1.1. Pharmaceutical policy scope

• Support the strengthening of collaboration mechanisms and develop regional guidelines

in key areas of implementation of the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy.

• Promote the development and management of human resources in the areas related to

the pharmaceutical policy.

• Promote the use of evidence in decision-making for the development, implementation and

assessment of pharmaceutical policies both at the sub-regional and national levels.

3.1.2. Regulatory framework

• Develop a sub-regional regulatory framework for medicines and strengthen the collaboration

among Caribbean countries to ensure the performance of the essential components of

medicines regulation.

3.1.3. Access

• Strengthen the collaboration among the national pharmaceutical systems and promote

and support the development and implementation mechanisms for joint negotiation of

medicines procurement.

• Develop sub-regional mechanisms for strengthening patent examination systems with a

“pro–public health” approach and support the countries’ efforts to promote public health

and access to medicines in order to take advantage of TRIPS fl exibilities in conformity with

the Doha Declaration on Public Health.

14

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

3.1.4. Rational use of medicines:

• Develop a sub-regional strategy and work plan for strengthening the rational use of

medicines in the Caribbean as part of the pharmaceutical policy.

3.2. Strategies

The strategies are presented according to the same approach as the CCH III, as national-

level strategies and as areas for joint collaboration.

3.2.1. Pharmaceutical policy scope

Objective: Support the strengthening of collaboration mechanisms and develop regional

guidelines in key areas of implementation of the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy.

Areas for joint collaborative action

• Develop an implementation plan for the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy, including

collaboration and communication mechanisms among the national health authorities and

establishment of regional structures for policy oversight;

• Strengthen pharmaceutical services within the network of health services, emphasising

the renewed Primary Health Care concept;

• Develop a sub-regional legal framework and model legislation related to medicines and

pharmaceutical services (with provisions for language and cultural idiosyncrasies);

• Develop sub-regional policies related to medicines pricing and generic medicines;

• Develop strategies for promoting the appropriate use of traditional and complementary

medicines in the Caribbean; and

• Support countries in the planning and negotiation of international and inter-governmental

agreements related to pharmaceutical policies.

At the national level

• Strengthen policy and regulation of pharmaceutical products and services as part of the

steering role of the state to ensure essential public health functions;

• Update, monitor and evaluate the existing policies and the development of new national

pharmaceutical policies; and

• Support the updating of the national legal framework related to medicines and

pharmaceutical services.

Objective: Promote the development and management of human resources in the areas

related to the pharmaceutical policy.

Areas for joint collaborative action

• Provide support for the Caribbean Network on Pharmacy Education and the rationalisation

and harmonisation of pharmacy education programmes;

15

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

• Support capacity-building in all related areas, in collaboration with Caribbean tertiary-level

educational institutions;

• Develop a strategic plan for human resource development, identifying needs and

opportunities for training institutions;

• Support the development of a mechanism for accreditation of pharmacy programmes and

the licensing of all categories of pharmacy professionals within the CSME;

• Collaborate with the Caribbean Accreditation Authority for Education in Medicine and other

Health Professions to facilitate the accreditation of pharmacy programmes in the Region.

Objective: Promote the use of evidence in decision-making for the development, implementation

and assessment of pharmaceutical policies both at the sub-regional and national levels.

Areas for joint collaborative action

• Develop the Pharmaceutical Observatory as a resource for evidence-based decision-

making;

• Support the strengthening of the information systems; and

• Support the development of operational research in strategic areas of pharmaceutical

policy.

3.2.2. Regulatory framework

Objective: Develop a sub-regional regulatory framework for medicines and strengthen the

collaboration among Caribbean countries to ensure the performance of the essential components

of medicines regulation.

Areas for joint collaborative action

• Develop a sub-regional platform for regulation of medicines, integrated with the regulation

of other health technologies;

• Develop draft legislation for the Caribbean and the participating countries for the

development of essential regulatory functions;

• Strengthen collaboration among the national authorities and establish a Caribbean

Network of Medicines Regulation, including the existing Pharmacovigilance Network of

the Caribbean, working in close collaboration with the Pan American Network for Drug

Regulatory Harmonization (PANDRH);

• Strengthen the Caribbean Regional Drug Testing Laboratory (CRDTL)

7

and support its

incorporation into CARPHA; and

• Develop guidelines for a code of ethics for pharmacists, model codes of conduct for

health professionals involved with issues related to the pharmaceutical policy and ethics

guidelines for committees and advisory bodies to avoid confl icts of interest.

7

Currently, Caribbean Public Health Agency/Drug Testing Laboratory (CARPHA/DTL).

16

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

At the national level

• Strengthen the existing national regulatory authorities to perform essential regulatory

functions with the updating of national institutional arrangements and national legislation;

• Strengthen regulatory enforcement mechanisms and enhance the quality assurance of

pharmaceutical products and services, in both public and the private sectors;

• Strengthen existing national laboratories for quality control of medicines and support the

development of laboratories, when pertinent, integrated into the Pan-American Network

of NLQCM.

3.2.3. Access

Objective: Strengthen the collaboration among the national pharmaceutical systems and

promote and support the development and implementation mechanisms for joint negotiation of

medicines procurement.

Areas for joint collaborative action

• Strengthen the Caribbean Regional Network of Pharmaceutical Procurement and Supply

Management Authorities (CARIPROSUM) and the harmonisation of medicines supply

systems in the Caribbean;

• Promote the development of a sub-regional platform for pooled negotiations; and

• Develop a sub-regional policy framework for cost-containment strategies, including use

of generic medicines, sustainability of fi nancing mechanisms and price regulation and

monitoring.

At the national level

• Strengthen national medicines supply systems, including public procurement and supply

management agencies, by ensuring sustainability and cost containment; and

• Develop and implement cost-containment strategies, including use of generic medicines,

sustainable fi nancing mechanisms and price regulation and monitoring.

Objective: Develop sub-regional mechanisms for strengthening patent examination systems

with a “pro–public health” approach and support the countries’ efforts to promote and protect public

health and access to medicines in order to take advantage of TRIPS fl exibilities in conformity with

the Doha Declaration on Public Health.

Areas for joint collaborative action

• Develop a work plan for implementing the Global Strategy on Intellectual Property Rights in

the Caribbean as part of the pharmaceutical policy, including the development of strategic

alliances;

• Develop and harmonise procedures for patent analysis with a pro–public health approach

and support national patent offi ces in improving their procedures for analysis within this

approach; and

• Support CARICOM Member States in adopting TRIPS fl exibilities.

17

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

At the national level

• Promote legislative changes to adopt TRIPS fl exibilities; and

• Strengthen collaboration between health and trade agencies and improve procedures for

analysis of pharmaceutical patents with a pro–public health approach.

3.2.4. Rational use of medicines

Objective: Develop a sub-regional strategy and work plan for strengthening the rational use of

medicines in the Caribbean as part of the pharmaceutical policy.

Areas for joint collaborative action

• Develop a model sub-regional EML and formulary;

• Develop and promote harmonised regional STGs; and

• Develop a regional medicines information centre in close collaboration with poisoning

information centres, working as a network with national medicines information centres

and in partnership with the Latin American and Caribbean Medicines Information Network.

At the national level

• Support countries in strengthening selection and use of medicines;

• Promote advocacy for strengthening access and rational use of medicines in the

community; and

• Support the integration of the existing national medicines information centres into a

regional scheme.

19

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

4. MECHANISMS FOR IMPLEMENTATION,

MONITORING AND EVALUATION

4.1. Responsibility and oversight structure

The implementation of the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy is a shared responsibility of the

national health authorities and stakeholders from the Caribbean institutions, with technical and

fi nancial support provided by the CARICOM Secretariat and PAHO/WHO. Establishment of the

Expanded Technical Advisory Committee on Pharmaceutical Policy (TECHPHARM) will be part of

the oversight mechanism. This committee will be responsible for facilitating the implementation,

follow-up and assessment of the policy (see Annex VI). The secretariat for policy implementation

will work under CARPHA. In the transition period for the establishment of CARPHA, PAHO/WHO,

through OCPC, will provide support to the secretariat in close collaboration with the CARICOM

Member States and associate members, as well as the CARICOM Secretariat and the CARPHA

implementation team.

It is proposed that TECHPHARM be an advisory body. With respect to its operational

procedures, a simple majority has been proposed for its quorum and for voting purposes.

TECHPHARM should meet twice a year and, if necessary, schedule additional meetings and

solicit the support of small working groups. In the meantime, members should make use of virtual

collaborative mechanisms.

TECHPHARM will assess the progress of the implementation of the policy in an annual report

to the CARICOM Ministers of Health, convening as COHSOD, that will be embedded in the

reporting mechanisms of the CMOs regarding CCH III implementation. A set of core members

and rotating country representatives will be present, as well as sub-groups and observers. The

rotating portion of TECHPHARM should not exceed one third of its membership, to ensure the

continuity of its work. Furthermore, in order to take informed decisions based on expertise, it is

important to have senior representation in TECHPHARM.

A declaration of confl ict of interest and impartiality should be signed by its members, and a

code of conduct should be established and adhered to. The tenure for TECHPHARM members

is set at three years.

TECHPHARM will support and oversee the proposed collaborative activities and mechanisms

and integrate different related initiatives of, for example, the Caribbean network of pharmacy

schools. TECHPHARM will also be responsible for identifying sources of fi nancial support and

submitting proposals for fi nancing sub-regional structures.

Annex VII of this document outlines the proposed terms of reference for TECHPHARM at its

inception.

20

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

4.2. Strategies for implementation

An implementation plan with performance indicators will be developed as part of the

implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy. An outline of

the implementation plan is presented in Annex VI of this document, and a roadmap for the plan is

provided in Annex VIII. The plan will be developed once the policy has been approved.

The strategic implementation plan will be created as part of a

participative process. A proposal

has been made to organise the implementation plan within a matrix based on the six building

blocks of well-functioning health care systems:

• governance and stewardship;

• management;

• service delivery, fi nancing and accountability;

• human resources;

• knowledge management and information systems; and

• monitoring and evaluation.

All of these elements fi t within the four above-mentioned areas of policy scope, regulatory

framework, access and rational use of medicines.

4.3. Reporting mechanism

TECHPHARM will assess the progress of the implementation of the policy and will submit an

annual report to the CARICOM Ministers of Health, embedded in the reporting mechanisms of the

CMOs relating to CCH III implementation.

4.4. Financing

It is necessary to establish a sustainable fi nancing mechanism for the policy, including

TECHPHARM with respect to policy oversight. The policy document provides guidelines for

regional donors’ support to the community in a synergistic way, setting the priorities for the Region.

Furthermore, it is necessary to cooperate with an increased set of donors in order to speed up the

process and to establish mechanisms through which governments can participate in fi nancing the

strengthening of the public pharmaceutical sector.

21

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The establishment of the Caribbean Pharmaceutical Policy and the creation of national

pharmaceutical policies are urgent priorities. For this purpose, the countries are urged to gradually

incorporate the provisions of the policy into their respective national legal systems and to take

the necessary steps to establish and participate in the proposed collaborative network approach.

23

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

REFERENCES

1. United Nations, Social and Development Council. The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard

of Health: 08/11/2000. E/C.12/2000/4 (General Comments). Available at: http://www.unhchr.

ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(symbol)/E.C.12.2000.4.En#1

2. World Health Organization. Global Comparative Pharmaceutical Expenditures: With Related

Reference Information (Health Economics and Drugs EDM Series No. 3, Document EDM/

PAR/2000.2). Geneva: WHO, 2000.

3. Caribbean Community Secretariat. The Revised Treaty. Available at: http://www.caricom.org/

jsp/community/community_index.jsp?menu=community

4. Caribbean Community Secretariat, Offi ce on Trade Negotiations. CARIFORUM Economic

Partnership Agreement (EPA) Negotiations. Available at: http://www.crnm.org/index.

php?option=com_content&view=article&id=276&Itemid=76

5. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. PAHO/WHO Sub-regional

Cooperation Strategy—Caribbean 2010–2015 [approved by the Caucus of CARICOM Health

Ministers, 2010]. Bridgetown Barbados: PAHO/WHO, 2010.

6. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Health Situation in the

Americas: Basic Indicators, 2006. Available at: http://www2.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2009/

BI_2006_ENG.pdf

7. Health Research for Action/Caribbean Community. Regional Assessment of Drug Registration

and Regulatory Systems in CARICOM Member States and the Dominican Republic.

Georgetown, Guyana: CARICOM, 2009.

8. Health Research for Action/Caribbean Community. Regional Assessment of Patent and

Related Issues and Access to Medicines in CARICOM Member States and the Dominican

Republic. Georgetown, Guyana: CARICOM, 2009.

9. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Pharmaceutical Situation in

the Caribbean: Factbook on Level I Monitoring Indicators—2007. Available at: http://www.

paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=20839&Itemid=&lan

g=en

10. Caribbean Community. Declaration of Port of Spain (2007): Uniting to Stop the Epidemic

of Chronic NCDs. Available at: http://www.caricom.org/jsp/communications/meetings_

statements/declaration_port_of_spain_chronic_ncds.jsp

11. Caribbean Community. Caribbean Cooperation in Health Phase III (CCH III): Investing in

Health for Sustainable Development 2010–2015. Georgetown, Guyana: CARICOM, 2010.

12. World Health Organization. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve

Health Outcomes. WHO’s Framework for Action. Geneva: WHO, 2007.

13. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Renewing Primary Health

Care in the Americas: A Position Paper of the Pan American Health Organization/World Health

Organization (PAHO/WHO). Washington, D.C.: PAHO/WHO, 2007.

25

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

ANNEX I. Former Technical Advisory Group on Trade-Related Intellectual Property

Rights (TAG)

1

Princess Thomas-Osbourne Head of the Standards and Regulation Division,

Ministry of Health, Jamaica

Maryam Hinds Director, Barbados Drug Service

Ministry of Health, Barbados

Miriam Naarendorp Pharmacy Policy Coordinator

Ministry of Health, Suriname

Richard Aching Intellectual Property Offi ce, Ministry of Legal Affairs,

Trinidad and Tobago

Lucette C.M Cargill Director, Caribbean Regional Drug Testing

Laboratory

Francis Burnett Managing Director, Pharmaceutical Procurement

Services, Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

Adriana Mitsue Ivama Brummell Sub-Regional Advisor on Medicines and

Health Technologies, Pan American Health

Organization/World Health Organization

Offi ce of Caribbean Program Coordination

Malcolm Spence Technical Advisor, Offi ce of Trade Negotiations,

CARICOM Secretariat

Rudolph Cummings Programme Manager, Health Sector Development,

CARICOM Secretariat

Rhonda Wilson Deputy Programme Manager, External

Economic and Trade Relations, CARICOM

Secretariat

1

TAG was responsible for the development of the CPP as well as for the consultation process leading to its approval.

26

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

27

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

Annex II. Executive Summary - CARICOM Regional Assessment of Drug Registration and

Regulatory Systems

1

CARICOM countries are faced with an increasing burden of chronic non-communicable

diseases for which treatment and care need to be ensured. This, in addition to scaling up treatment

of HIV/AIDS, requires sustained access to adequate quality medicines at affordable prices.

In this context the Technical Advisory Group, established at the 10th CARICOM Council

of Human and Social Development, recommended that a study be conducted on regulatory

systems for existing medicines in CARICOM countries with a view to establishing their adequacy

for ensuring the timely supply of safe, effective and quality medicines. Realising that market,

human and fi nancial constraints might pose a potential barrier to effective and effi cient medicines

regulation in individual Member Countries, the study was also tasked with establishing strategies

and an action plan for the development of a harmonised medicines regulation system for the

Region.

Study Implementation

The 15 CARICOM Member States (Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize,

Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint

Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago) were included in the study.

The Dominican Republic had been identifi ed as an additional benefi ciary of the study in the Pan

Caribbean Partnership against HIV/AIDS (PANCAP)/World Bank agreement.

The study was conducted in two main phases, i.e., a data collection phase and a consolidation

phase. Data collection for the regulatory systems assessment in countries was based on the Guide

for Data Collection to Assess Drug Regulatory Performance, developed by WHO and amended to

suit the specifi c purposes of this study. Both the data collection instruments and implementation

work plan were approved by the CARICOM Secretariat and the Technical Advisory Group.

Based on the WHO assessment instrument, stakeholder interviews were conducted in

Barbados, the Dominican Republic, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, Suriname and Trinidad and

Tobago during the period 18 January to 15 February 2009. During the same period, questionnaires

for self-completion were sent out to the remaining study countries. These countries were supported

in person by HERA team members of the CARICOM Study on Intellectual Property Rights, TRIPS

and Access to Medicines that was conducted in parallel and through telephonic follow-up by the

study team leader.

During the consolidation phase, responses collected in countries were analysed and

documented in specifi c reports for each study country (Volume 2), and summarised for the main

report. In addition, study countries’ medicines legislation was assessed.

Study fi ndings and resulting recommendations for medicines regulatory harmonisation

strategies presented in the draft report were discussed with the Technical Advisory Group. This

Final Report includes the results of these discussions.

1

For further information, please see the complete report: Regional Assessment of Drug Registration and Regulatory Systems in

CARICOM Member States and the Dominican Republic (July 2009).

28

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

Medicines Regulation

Medicines are a crucial input to improving and maintaining the health of the population, and

considerable funds are dedicated by governments and individuals to the purchase of medicines.

In order to be benefi cial, medicines need to be safe, effective and of adequate quality—otherwise

funds will be wasted, and the populations’ health will be put at risk. However, neither the consumer

nor the prescriber has the information and expertise needed to establish whether a particular

product complies with these requirements. It is thus in the interest of public health that government

intervenes in the medicines market through regulation.

According to international consensus, medicines regulation encompasses the following critical

functions that need to be provided for in the national medicines legislation:

• Licensing (registration) of pharmaceutical products;

• Licensing of pharmaceutical premises (manufacturers, importers, distributors);

• Inspection of distribution channels and goods manufacturing facilities;

• Quality control laboratory testing;

• Adverse drug reaction monitoring;

• Control of advertising and promotion; and

• Control of clinical trials.

The National Regulatory Authority (NRA) is the authority empowered by law to carry out

regulatory functions pertaining to medicines and to ensure compliance with the legal requirements.

Study Findings

Pharmaceutical sector characteristics defi ne to a great extent the context within which medicines

regulatory systems operate. National Medicines Policies provide guidance on governments’ goals

related to the public and private pharmaceutical sectors, including the commitment to ensure

quality, safety and effi cacy of the medicines marketed. Of the 16 study countries, seven have a

National Medicines Policy, and of these three have been offi cially adopted by the government.

Seven of the study countries have privately owned pharmaceutical manufacturing plants

producing multi-source (generic) products only, with production also for export in four countries.

Private sector pharmaceutical importers and/or wholesalers are operating in 14 of the 16 countries,

while all of the study countries have private retail pharmacies (ranging from 1 in Montserrat to

2,812 in the Dominican Republic).

Legislative provisions

All study countries have some type of medicines legislation, including specifi c acts providing

for the control of narcotics and psychotropic substances. However, none of the existing legislation

is fully comprehensive. Provisions frequently missing include:

• control of clinical trials;

• adverse drug reaction monitoring;

29

CARIBBEAN PHARMACEUTICAL POLICY

• control of product promotion and advertisement; and

• specifi c prohibition of counterfeit medicines.

Registration of pharmaceutical products is a requirement by law in seven of the 16 study

countries.

Challenges identifi ed include:

• legislation that is not being updated;