Swedish American Genealogist Swedish American Genealogist

Volume 36 Number 2 Article 10

6-1-2016

A journey across the Atlantic in 1908 A journey across the Atlantic in 1908

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag

Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

(2016) "A journey across the Atlantic in 1908,"

Swedish American Genealogist

: Vol. 36 : No. 2 , Article 10.

Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol36/iss2/10

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center at

Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized

editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected].

14

Swedish American Genealogist 2016:2

I arrived in Gothenburg on the morn-

ing of 9 April (1908) and was met at

the station by an agent for the

Scandinavia America Line from

whom I had ordered a ticket. He

escorted me to a hotel and said I

should come to his office.

On the way to the hotel I asked

the agent if there were many who

traveled over now. He shook his head

and said no, and he said there were

a couple of big reasons why people

did not travel now. First of all, the

bad times, “and now they begin to do

so much in this country so that people

will not travel.”

In the line’s office I could pay for

my ticket, but could not receive it

until we reached Christiania, be-

cause I only had a testimony of

conduct (frejdebetyg) and not a

moving-out certificate. The shipping

lines are always helpful in cases like

that.

To Christiania

In the evening we received train

tickets and were escorted by the

agent to the train. Upon arrival at

Christiania at 7 o’clock in the morn-

ing on April 10 there was nobody

there to meet us. We found the way

therefore to the line’s office, and on

the road we are overtaken by a valet

who should have met us, but had

overslept. He took us to Nielsen’s

Hotel on Skippergaden. It was a hotel

of about the 7th grade. We got a room

where we would stay that day. We

were four: my brother, a man from

Västerbotten, and a man from Bo-

huslän. The room was filthy and

unpleasant. On the floor in the

commode was vomit from someone

who had apparently been seasick

before the trip started. The maid

pretended not to notice anything, but

began to set up food for us on the ta-

ble. Then I showed it to her and asked

her if it was not possible to clean it

up and also remove the dirty slop

bucket that stood there. She looked

at me as if she wanted to say that I

had more demands than what they

were accustomed to. She cleaned the

floor, but we got to keep the slop

bucket. Even the tablecloth was poor,

in tatters and dirty.

At 10:30 a.m. we were to go to the

office and get our tickets. When we

entered we were told to stand in line

and go in to the doctor. When we

came in to him, we had in turn to sit

down, and so began the investigation.

The doctor said, “Show your hands,”

and so he looked at the inside of the

hands. Then he said, “Open your

mouth! say ‘A’, ”as he looked on the

inside of the eyelid, and so it was

done. When we came back to the of-

fice, we were asked to come at 2

o’clock to get our tickets. We did so,

and at 4 p.m. we were finally allowed

to board. The steamer Oscar II had

come to Christiania already at 9

o’clock in the morning and was now

loading bundles of wood pulp. It

looked like to be the principal load

from Christiania.

Finally onboard

When we came onboard, the quarter-

master met us, looked at our tickets,

and the waiters took our suitcases

and guided us down to our cabins. I

got my berth in the cabin No. 50. It

was for 4 people, but we were only 3

in it.

In Christiania about 200 people

boarded the ship, including many

Swedes. In addition, many Swedes

had boarded before, those who had

boarded in Copenhagen. A year ago,

they used to send twice as many

passengers from Christiania, said the

office there.

Exactly at 9 in the evening of 10

April, we left Christiania. There was

then a little rain and a light mist.

On April 11, between 8 and 9 a.m.

we anchored outside Kristiansand to

board passengers there. We got about

100 new passengers. At around noon

we left Kristiansand, and so began

the actual voyage.

A journey across the Atlantic in 1908

A story from the 1907 – 1914 Swedish Emigration Survey

T

RANSLATED BY ELISABETH THORSELL

AND CHRISTOPHER OLSSON

15

Swedish American Genealogist 2016:2

The menu for the journey looked like this:

The 11

th

. Breakfast: meat and potatoes, bread and butter and coffee. The

bread, abundant, like everything else, was always good. It consisted of

fresh wheat bread and coarse, soft bread. Loaves reminiscent in

appearance of the Swedish “ankarstockar”. Dinner: soup (some sort of

meat soup), bread and butter, meat and potatoes, and a small dry pas-

try for dessert. At 3 coffee with wheat flour buns. Supper: meat and

potatoes and bread and butter and tea.

The 12

th

. The same as the 11th except for dinner when the dessert consisted

of apples.

The 13

th

. The same as the 11

th

.

The 14

th

. Breakfast: meat sausages; the remainder being like the 11th.

Dinner: sweet soup, meat and potatoes, and for dessert apples. Supper

as the 11

th

.

The 15

th

. Breakfast: raw herring and potatoes, butter, bread, and coffee.

Dinner: cabbage soup, fish stew (potato and fish stewed together) and

as well the dry pastry. Supper: meat, cabbage and potatoes, tea.

The 16

th

. The same as the 12

th

.

The 17

th

. Breakfast: fishballs and potatoes. Dinner: sweet soup, meat and

potatoes, and apples. Supper: beef stew and potatoes.

The 18

th

. Breakfast: meat sausages and potatoes as well; for those who so

desired, porridge of oatmeal. The milk to it was poor. At dinner we were

given the best of the whole trip, consisting of rice pudding with cinnamon

and sugar and beer in a glass. After some discussions we were given a

fraction of the bad milk instead of beers. Also, fish and potatoes; pastry.

Supper: fish stew and potato, tea.

The 19

th

. Breakfast: two eggs and hot oatmeal, served with the bad milk.

Dinner: broth with dumplings, meat, potatoes, and for dessert an orange.

Supper: meat, potatoes, and stewed pickles.

The 20

th

. Breakfast: meat and potatoes, coffee. Dinner: sweet soup, meat

and potatoes; pastry. Supper: lapskojs [a stew of potatoes and salted

meat, bayleaf, a little pepper and butter], tea.

The 21

st

. Breakfast: potato and beef stew; coffee. Dinner: peas, pork and

browned cabbage; pastry. Supper: potato, meat, and pickles concocted.

Some of us found it hard to eat.

The food containers were dirty. I gave

our waiter 2 kr. That had a good

effect. When the coffee was served at

3 p.m. he first had just as many cups

as was enough for everyone at our

table except for my brother and me.

He went after two additional cups,

and these got an extra thorough

drying. This was repeated often.

The meal times onboard were:

breakfast at 8 a.m., dinner at 12,

coffee at 3 p.m., and supper at 6 p.m.

On the “tween” deck there were

four different dining rooms. In the

dining room where families and

unmarried women ate, the tables

were quite nice. But where we should

eat it was dirty. The oilcloths were

poor and often poorly dried. The

towel, which the waiter had, was

used for almost everything. With

them I saw that they both wiped the

bench which we were sitting on, the

table cloth, and if you made comment

about it, also the food vessels. And

behind me was a large metal box for

refuse. It stood uncovered even

during meals. When the meals were

finished and tables cleared, we used

to sit there to read, write, or play. It

was the only place we had to be at.

But when they came with the tubs of

washing water and poured it out in

a corner of the dining room, the

smelly splashing water made it at

times almost impossible to be down

there. The food was almost always

the same.

The food on board is approxi-

mately equal to what you get on the

English lines, though it was better

served on Ivernia, the Cunard Line’s

old boat, which I traveled with in

1905, despite the fact that they had

so many emigrants that they had to

set the table completely four times

for every meal.

The trip became quite lengthy

because the boat is so slow. There was

a map in our dining room and in one

in the families’ dining rooms. It was

shown every day how many miles the

steamer had passed from noon on one

day to noon on the second day.

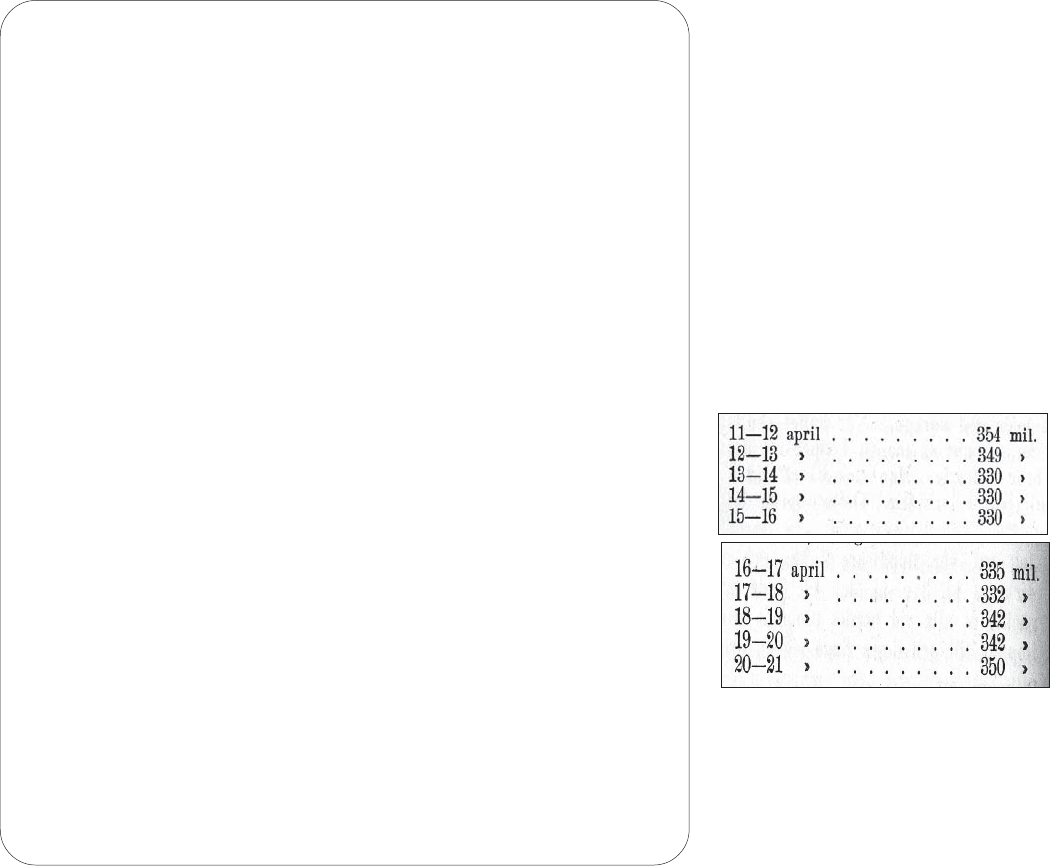

Here are the figures from our map

in English miles:

In New York Again

Upon our arrival in New York, the

Cunard Line’s new steamer Maure-

tania left for Liverpool. She has done

this journey (as fast) as 579 miles in

(24 hours).

In general, there was pronounced

dissatisfaction with the Danish boat

because it was so slow. We figured out

that you can make the journey across

England and then on to America in

less time this way than by taking the

“direct” route.

I spoke with some returning Swed-

ish-Americans of conditions in Swe-

den and America. One day I said that,

within a few years, we will have our

own Swedish line that will go directly

to New York.

“Not in 1,000 years,” said Mr.

Swanson from New York. “Why not?”

I asked. “They are too slow at home.

I think I have seen in the papers a

discussion of such a thing, but I do

not think it will be more than a love-

ly thought.

“How happy we Swedish-Ameri-

cans would be if it were successful.

16

Swedish American Genealogist 2016:2

If Sweden could have, say, three boats

of about 15,000 tons each, modern

and fast, with only a Swedish crew,

so that everyone could travel on this

line. Even if the boats went just every

three weeks, they would wait and

travel with it. How much Sweden

needs this line! Aside from that we

rarely see the Swedish flag in New

York harbor. How much cheaper

would things be that are now taken

over via England, Hamburg, or Co-

penhagen! I have traveled for many

years for a major U.S. export com-

pany which exports, in particular,

fruit and cheese to England.

“Once when I took a shipment over

to England I was promised by the

company to take three weeks for

myself to travel to Stockholm and vis-

it. When I got there I was, of course,

interested to see how things were

done in that business, a business that

I understood. I went and looked a-

round. Imagine my surprise when I

found my fruit boxes there. I asked

where they were purchased. I was

told, England or Hamburg. They were

considerably overpriced by these in-

termediaries. I have spoken to sev-

eral others since then and they have

said the same thing.”

Views on shipping lines

Among my tablemates on the boat

was a tall, stately Swedish former

noncommissioned officer of a Guards

regiment. He was traveling now for

the thirteenth time across the ocean.

He had been in Scandinavia and Fin-

land and sold farms in New York

State. He had traveled on the Oscar

II three times before, but always as a

1

st

or 2

nd

class passenger. One day

when we sat down to table, the cap-

tain was on board and went through

the dining room. He sees the Swede,

goes up to him and greets him, and

calls him by name.

According to what the Swede him-

self said, the captain asked him why

the Swedes were beginning to aban-

don the line. The Swede replied that

it was largely due to the Danes openly

siding with the Norwegians in 1905

[Ed:s note: at the dissolution of the

union between Sweden and Norway.

].

And that, he said, was something we

Swedes will not easily forget.

However, many Swedes still trav-

el with the Scandinavia-America

Line. I asked one day at the office

where they get most of their passen-

gers? The clerk said that Norway

came in first place, Sweden in second,

and Denmark third. Despite this,

they have only Danish waiters. It is

impossible for many Swedes to un-

derstand what they say. So the ad-

vantage they had of a Scandinavian

crew that spoke “Scandinavian,” was

minimal. It works out nearly as well

on the English lines because there

are now so many Swedish-Americans

who travel back and forth that you

can always get someone to translate.

Why go on a slow boat?

I asked many, including Mr. Swanson

from New York, why he had not

traveled with a large, rapid English

boat. “Well, you see,” he said, “I have

my family with me and it is both for

me and my family more convenient

to travel by this line. When you board

you need not switch ships until you

have arrived.”

The Scandinavia America Line’s

big trump card is that it runs directly.

That was the reason all the Swedes I

spoke with went by it. But still, there

were many who said that, rather

than lying on the ocean for twelve

days, they will travel with a faster

boat via England.

The boat’s office told me that the

journey usually takes about eleven

days.

To Ellis Island

We received a pilot on board at 11

p.m. and at 1 o’clock at night dropped

anchor at Staten Island, the quar-

antine location. At 5 o’clock in the

morning we were told to go up on

deck to be examined by the doctor

who was just then expected on board.

A moment later an old man came on

board. We had to stand in line and

march past him in double rows. He

just looked at us. Many who did not

notice him when they passed him

asked when the examination would

begin.

The exam over, the boat began to

move and at 8 o’clock in the morning

we were at the dock in Hoboken.

There we could leave the boat after

being on board for almost twelve

days. When our trunks were taken

ashore, we were called by the cus-

toms officers, who were always kind.

At about 11 o’clock we were taken on

board a boat to be transported to El-

lis Island, the last station.

When we got there, we had to

stand on the boat for close to an hour

before we were allowed to go ashore.

Then we were ordered to take our

suitcases and go to the building

where the last test would be admin-

istered. We stood in line on the stairs

and, with hat in hand, marched on.

We went down a wide aisle where two

men looked in the eyes of every one.

At the end of narrow passages,

each numbered 1 through 12, was an

interpreter and a man with lots of

paper. They only asked me how long

I had been in America previously, if

my brother would travel with me,

and how much money we had. It was

not even necessary to show our cash.

I was going to stay and see and hear

how the others did, but I was not

allowed, so we went to the waiting

room that said “To New York” to await

the ferry for Battery Park.

Down in the waiting room I met

several who said that there seemed

to be fairly many who seemed to have

difficulties getting admitted into the

country. It was said that the exami-

nation was very strict.

Conditions onboard

Our trip had been favored by good

weather. On only one evening was

there storm. The cabin we had was

pretty good. The iron bedstead con-

sisted of a mattress of an approx. 4"

thick cushion. The pillow was similar

to the cushions on a Swedish second

class railroad carriage. The fabric of

both the mattress and the pillow

were of coarse, blue fabric, as was the

blanket.

On the first night on board, it was

so cold that we froze, but we got a

blanket the next day. The next night

was so hot that it was almost im-

17

Swedish American Genealogist 2016:2

possible to sleep. At about 6 in the

morning a boy came with a wet cloth

and went over the floor. A little later

a woman came who filled our water

carafe and dried our wash basin.

Then the boy returned and emptied

the wash water. It was similar on the

Cunard Line, only if I remember

right, we also got towels. Here we

didn’t get any.

Comparison with other

shipping lines

On board the Oscar II it appeared

that they had better cabins than on

the English lines I had traveled

before. I saw no large bunks divided

by sackcloth like I saw on the Iver-

nia. How it is on the big boats, I do

not know, but I would like to travel

home on the Cunard Line’s new sis-

ter ships Mauretania or Lusitania.

The difference in price between a 2

nd

class cabin for travel between New

York and Stockholm on the Maure-

tania vs. Oscar II is about 22 dollars.

The Mauretania costs $84.60; Oscar

II costs approx. $62.50. But I could

then do a better comparison. The

treatment on the Oscar II was like

that on other boats. They listened to

our wishes, shrugged their shoulders

– nothing more. Our view was that

Danes were favored. I had a cabin

without daylight and when I asked a

steward for a change I was told there

were no cabins available.

One day I saw a memo that an-

nounced that Mr. Mickelsen would

speak on “My travels through Amer-

ica and Europe, especially Russia.”

The man, a Dane, had lived in Amer-

ica for forty-two years. He began by

describing his home in Southern Ca-

lifornia and spoke about what a para-

dise it was, and how he thought it was

a shame that people “at home in Den-

mark” must have snow and ice and

cold when (in California) you could

go out to a pasture and pick the most

delightful flowers. He lamented that

the press and leading figures in the

old country spoke so poorly and

falsely about America, etc. I went up

to him after he stopped and asked if

it was easy to get land in California

and if it was cheap.

“No,” he answered, ”it is taken.

Land now costs $200 to $250 an acre.”

“That is something for the poor

immigrants there” I said. He just

tossed his shoulders and smiled. He

claimed in his speech that there is

enough space for half the European

population today. One day I met the

man as he was going to his cabin. I

asked to follow him and see how he

lived. He had a light, nice four-man

cabin alone, the best I had seen on

the boat. It was just below the stairs

to the second class.

[The writer is anonymous, and just

known by his signature K. H–n.

[His purpose for travel to America

was for his own business, but he was

traveling on a emigrant ticket, so he

could report on the conditions for the

emigrants back to the Emigration

Survey (Emigrationsutredningen, a

Swedish state survey).]

Ellis Island – main entrance.

The Great Hall in Ellis Island’s main building, which was, in the old days, filled with

immigrants, awaiting their examination.

Ellis Island opened in 1892 as a federal immigration station, a purpose it served

for more than 60 years (it closed in 1954). Millions of newly arrived immigrants passed

through the station during that time – in fact, it has been estimated that close to 40

percent of all current U.S. citizens can trace at least one of their ancestors to Ellis

Island.