457

Approach to the Emergency Patient

Chapter 32

APPROACH TO THE EMERGENCY

PATIENT

TRESS GOODWIN, MD*; KATHERINE ELLIS, MD

†

; CRAIG GOOLSBY, MD, ME

‡

INTRODUCTION

WHY EMERGENCY MEDICINE IS DIFFERENT

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CONCEPTS AND PROCEDURES

Prehospital Arrivals

The Initial Assessment

Sick Versus “Not Sick”

The Safety Net

The Emergency Department Workup

PATIENT ISSUES AND CHALLENGES SPECIFIC TO THE EMERGENCY

DEPARTMENT

CHALLENGES IN DEPLOYED EMERGENCY MEDICINE

SPECIFIC CHIEF COMPLAINTS AND RED FLAGS

Abdominal Pain

Chest Pain

Headache

Trauma

Shock

Poisoning

Cardiac Arrest

Case-Based Approach Summary

DISPOSITION

SUMMARY

*

†

‡

-

458

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

INTRODUCTION

Military medical providers (MMPs) face numerous

challenges in both stateside and deployed medical

practice. One of the most daunting and time-sensitive

challenges is managing a patient with an acute life-

threatening illness or injury. Patients with anaphylaxis,

severe hemorrhage, unstable cardiac dysrhythmias,

or intractable seizures need the .

Many practitioners do not encounter these types of

patients in their normal practice, and therefore lack

a conceptual framework and organized approach to

handle an unexpected emergency. Regardless of their

medical background, a practitioner can apply funda-

of high-pressure situations. For students and providers

of all levels, this chapter will provide the approach of

a specialty-trained emergency physician (EP) to the

fundamentals of assessing and treating severely ill

and injured patients.

1

This chapter will introduce readers to the concepts

of simultaneous diagnosis and treatment, working

with imperfect or limited information, and operating

in resource-constrained environments. This approach

is critically important to the MMP who confronts the

challenges of a deployed environment with limited

access to specialty consultants, including EPs. The

chapter also touches on a variety of core emergency

patient presentations. While it is not intended to be

managing these patients.

Beyond the normal challenges of civilian emergency

medical practice, in which patients are primarily treated

in designated emergency departments (EDs), military

with scarce resources. Mental preparation for emer-

WHY EMERGENCY MEDICINE IS DIFFERENT

. When a

patient presents to an outpatient orthopedics de-

partment, for example, the patient’s issue is often

focused and within a limited subset of diagnoses,

such as fractures or joint pain. The same applies to

problems are often diagnoses rather than .

For example, a patient visits their primary care doctor

for diabetes management, and the goals of the visit

and expected outcomes are anticipated and often

predictable. Emergency patients typically present

with symptoms or a chief complaint. These symptoms

could represent a benign or life-threatening condi-

this distinction. Thus, practitioners must shift their

mindset to “complaint-based” or “symptom-driven”

evaluations of patients. Not all evaluations will lead

patient with “chest pain” or “abdominal pain” after

having excluded life-threatening conditions during

their workup process.

2

. There have been

numerous poorly informed popular media reports

about patients using EDs for non-urgent issues and

EDs primarily serving the uninsured. However, mul-

tiple studies have shown that nonacute issues do not

constitute the majority of ED visits, and that many

ED users are indeed insured and have a primary

care provider.

3–6

When a patient presents to the ED,

they are concerned enough about their symptoms

to seek emergency care, and their complaints are

often high risk. Emergency patients often believe

their symptoms are life threatening or warrant im-

mediate evaluation. An emergency practitioner must

recognize and acknowledge this worry. Sometimes

patients only need reassurance and education, and

then they can be safely discharged to their home or

returned to duty. It is important to remember that

even patients with benign conditions require respect

and a thorough evaluation of their complaint by an

experienced provider.

. EPs

face the need to form an immediate rapport with

patients, with whom they have no prior patient-

doctor relationships, in a high-stress environment.

The EP must rapidly earn the patient’s trust so he

or she will feel comfortable disclosing personal

details. In a deployed setting, EPs also care for

unique populations, such as local nationals and

enemy prisoners of war, which makes establishing

rapid rapport and an effective treatment relation-

ship even more complex.

. Test

results are often not available in time to make crucial

treatment information. Patients can arrive obtunded

and unable to provide a history. EPs often cannot fol-

low up with patients after discharge. These are just a

few examples of uncertainty emergency providers will

face. These situations can be uncomfortable, but mental

preparation for these realities can help non-emergency

specialists succeed.

459

Approach to the Emergency Patient

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CONCEPTS AND PROCEDURES

Prehospital Arrivals

Few non-EPs interact routinely with prehospital

providers. Prehospital crews transport most emer-

gently ill or injured patients, whether deployed or

stateside, for emergency care. In the United States,

patient transport is done by a combination of

paramedics and emergency medical technicians in

transport is done by military medics with varying

skill sets and in a multitude of platforms, such as heli-

copters, armored vehicles, or vehicles of opportunity.

Depending on the training and equipment of these

providers, the arriving patient may already have

had interventions and diagnostics performed, such

as venous access, an electrocardiogram, or a blood

glucose measurement. Most often, the prehospital

providers will call and report to the EP, allowing

the ED to prepare for the patient’s arrival. For ex-

ample, if an urgent surgical patient is inbound, the

EP can prepare and gather all necessary equipment,

have blood prepared to transfuse, and summon any

needed help or consultants prior to the patient’s ar-

rival. Preparation is even more important in mass

casualty events when a large number of patients

arrive at the same time.

The Initial Assessment

MMPs caring for emergency patients should hone

their ability to perform a “doorway assessment” for

a quick evaluation of the patient’s condition. Simple

observations by a well-trained eye are crucial to gath-

ering information and starting rapid treatment. Here

are questions to consider when evaluating a patient

on arrival:

• Did the patient arrive via ambulance or come

into the waiting room?

• Did the patient walk into the room or arrive

via wheelchair or stretcher?

• Does the patient walk without assistance?

With a steady gait?

• What is the patient doing? Writhing in pain?

Lying motionless? Talking on a cell phone?

• What is the patient’s work of breathing? Are

they gasping for air, wheezing, or breathing

comfortably?

• What is the patient’s level of pain? Are they

holding a particular area, grimacing, or moan-

ing?

• Is the patient actively vomiting?

• What is the patient’s mental status? Do they

acknowledge you walking in the room and

make appropriate eye contact, or is their

mental status altered?

• Is the patient morbidly obese, normal, or ca-

chectic?

• What about the skin: does the patient appear

pale, mottled, cyanotic, jaundiced, burned, or

covered in a rash? Do you see hemodialysis

access in their arm?

• What is the patient’s hygiene? Clean? Dishev-

eled? Neglected?

• What does the room smell like? Alcohol?

Gangrene?

• Is family, battle buddy, or a caretaker at the

bedside, or did the patient arrive alone?

All the above questions, and many more, can be

answered in seconds. Practitioners should be mindful

of all available information when seeing emergently ill

or injured patients. This review, combined with vital

signs, and very brief historical information can yield

important information needed to begin an emergency

assessment and stabilization.

Sick Versus “Not Sick”

EPs use the term “sick” to refer to seriously ill or

injured patients. While the vast majority of ED patients

have some degree of illness or injury, most will not

be critically ill. Determining “sick” from “not sick”

sounds simple, but is in reality a challenging skill that

must be developed by anyone providing emergency

care. Some patients’ situations are fairly obvious—in

clear respiratory distress, unconscious, or with hem-

orrhaging wounds. These conditions should be im-

mediately stabilized. The more challenging patients

are the ones who are not overtly sick, but have char-

acteristics that make them high risk and more likely

to decompensate.

A blunt trauma patient (eg, someone who had a

signs of trauma, a fairly benign exam, and stable

vitals. However, they may decompensate as internal

injuries, such as a lacerated spleen, worsen. Know-

ing that this patient has a high-risk history should

prompt the emergency practitioner to continue to

monitor and reevaluate the patient (see below for

“sick” patients).

460

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

The Safety Net

EPs use the term “safety net” in one of two ways. A

civilian ED is the safety net of the medical community.

An ED is the only medical facility open 24 hours a

day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. When a patient’s

not have a primary care doctor or are visiting from

out of town, the emergency room may be the only

option. The ED may be the only option for the unin-

sured, under-insured, homeless, and mentally ill. In a

policy statement, the American College of Emergency

Physicians wrote:

Having the only universal mandate for providing

health care—the Emergency Medical Treatment

and Labor Act (EMTALA)—the nation’s more than

4,000 hospital emergency departments are a portal

for as many of three out of four uninsured patients

admitted to US hospitals, making them a vital,

although often unrecognized, component of the

safety net.

3

The safety net concept also refers to an initial

series of steps designed to stabilize patients. Once

must rapidly establish the safety net. While most

emergency patients will not rapidly decompensate

during their initial ED course, sick patients might. A

mantra often cited by medics and EPs alike is, “IV,

O

2

, monitor, advanced airway equipment.” These

procedures—establishing intravenous (IV) access,

placing the patient on oxygen and a cardiac monitor,

and ensuring advanced airway equipment is readily

available at the bedside—are the foundation of the

safety net.

The safety net should be started immediately.

On entering the room of a sick patient, emergency

providers should order the team to initiate safety

net procedures while rapidly anticipating next steps.

Should antibiotics be started? Does the patient require

intubation or additional venous or intraosseous access?

The key to establishing the safety net is preparedness,

and becoming comfortable starting treatment while

performing diagnostic studies. An elderly, hypoten-

sive, tachycardic patient with altered mental status is

sick. If the provider waits for all imaging and lab tests

to return, the patient may not survive. Additionally,

antibiotics, or cardioversion prior to performance of

any labs or additional diagnostic testing. These rapid

steps may be uncomfortable for many MMPs but may

save an emergency patient’s life.

The Emergency Department Workup

The focus of an emergency patient’s workup and

care is based on the chief complaint. Patients may

have many ongoing medical issues at a given time

and present with multiple complaints. However,

one acute issue typically prompts the ED visit, and it

should be the focus of the provider’s history, physi-

cal exam, and diagnostic testing. As in other areas of

medicine, patient history and physical examination

provide most of the needed information to drive any

necessary testing to diagnose and indicate appropri-

ate disposition the patient.

Unlike in some other areas of medicine, emergency

providers need to think in a mentality.

Medical students are typically trained to take a history

diagnosis, and then consider which diagnosis is most

likely. Emergency providers follow these steps as well;

however, instead of considering which diagnosis is

most likely, they must consider which is most lethal—

for emergency care often have emergency problems

and are at higher risk than those seen in outpatient

clinics. This does not mean that all patients require

exhaustive testing to exclude emergency diagnoses;

rather, it is imperative that an emergency provider

these diagnoses and exclude them by history,

physical examination, or testing if indicated.

For example, when a 30-year-old asthmatic patient

presents to an ED with a chief complaint of “shortness

of breath,” the diagnosis is most likely an asthma ex-

acerbation. However, a pulmonary embolus is a more

lethal diagnosis. If the provider does not consider

and at least mentally address this possibility, he or

she might miss an important emergency condition.

Knowing the potentially fatal diagnoses for each

patient complaint and focusing a workup to exclude

them are key knowledge and skills for emergency

providers.

Again, testing should be focused on the patient’s

chief complaint. MMPs should consider available re-

sources and choose tests that will management

of their patient. An example of a widely available test

that can rapidly change management is a pregnancy

test in a woman of childbearing age with an abdominal

or pelvic complaint. This one simple qualitative answer

can drastically change the direction of diagnostics and

treatment. On the other hand, an example of an often

unnecessary test is a rib x-ray series. For a patient with

mild chest trauma who is suspected of having either

a rib fracture or rib contusion, rib x-rays are usually

not indicated. Rib fractures and contusions are treated

461

Approach to the Emergency Patient

in the treatment. A chest x-ray may be indicated to

exclude pneumothorax or another abnormality, but

emergency management or patient disposition or

follow-up. Management is the same—pain manage-

ment and prevention of atelectasis or pneumonia with

incentive spirometry.

PATIENT ISSUES AND CHALLENGES SPECIFIC TO THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

Most EDs have individual patients who frequently

use the ED for care. Sometimes derogatorily called

and often for similar presentations. They are usually

older, have chronic medical conditions such as coro-

nary artery disease or asthma, and can be a source of

use the ED as their only source of care, but studies have

shown that they are also likely to utilize outpatient

clinics and have high rates of hospital admission.

4–6

As with other patients, the challenge is to know when

their issues are acute and life threatening. They must

be evaluated during each encounter with the same

thoughtful approach as any other patient. Additional

resources, such as social worker consultations, should

also be considered to help address other factors of their

frequent ED utilization.

EPs play a crucial role in detecting signs of abuse

in patients—ranging from infant/child abuse, to

intimate partner violence, to elder abuse and ne-

glect.

7

Patients presenting with multiple visits and

various injuries, along with stories inconsistent with

addition, concern should be raised if the patient

seems evasive or inappropriately frightened, or if

an overbearing and perhaps defensive partner or

family member is in the room.

8

In children, bruises

in various stages of healing as well as fractures or

injuries not consistent with their age or mobility

9

Often the ED may

having reasonable suspicion with at-risk patients

with concerning injuries could be the intervention

that saves their life.

CHALLENGES IN DEPLOYED EMERGENCY MEDICINE

Deployed MMPs face additional challenges in the

personal safety can be a concern. During deployment,

MMPs are far from loved ones and may have limited

ability to communicate with them. Additionally, prac-

titioners may be working outside their normal comfort

zone in their patient care duties. Several challenges for

emergency providers follow.

. MMPs will almost

certainly care for more than American troops when

deployed. They may treat contractors, local nationals,

third-country nationals, enemy prisoners of war, and

a host of other individuals. Caring for these popula-

tions may involve certain rules and unique challenges,

but the basic principle remains that MMPs provide

a baseline standard of care to every patient, regard-

less of background. Department of Defense Directive

2310.01E, which covers the Defense detainee program,

mandates “humane treatment,” which includes “ap-

detainee’s condition, to the extent practicable.”

10

As in

caring for diverse patients stateside, this may require

a language interpreter and adaptation to cultural

concerns. It is important that each MMP is aware of

resources available to help care for these patients, and

. Military emergency providers

in scope than those typically seen during stateside

duty. This book covers mass casualty in a separate

chapter (Chapter 34, Mass Casualty Preparedness and

Response), but it is important for emergency providers

to develop or understand their facility’s contingency

plan during a mass casualty event.

. The resources

available will vary dramatically depending upon the

practice environment. Section II of this book, Op-

erational Health Service Support, covers this topic in

more detail. The military designates various levels of

care based on availability of resources, ranging from

-

patients or perform advanced diagnostics. Those at a

Role 3 facility, such as an Air Force theater hospital,

will likely have computed tomography (CT) scanners,

a host of medications, and access to operative care

with surgical subspecialists. While MMPs should still

consider tests that would change patient management,

practicing at home.

462

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

SPECIFIC CHIEF COMPLAINTS AND RED FLAGS

This section consists of case scenarios focusing on

several common patient complaints. It is not meant to

be a complete list of chief complaints seen in the ED;

rather, it is designed to help MMPs learn the process

of evaluating a patient from an emergency medicine

perspective. The scenarios and workups described

include some repetition, partly because emergency

medicine providers approach many patients in a

similar way. As discussed previously, the EP will ask,

“is the patient sick or not sick?” and then proceed to

a more thorough history and exam as appropriate.

-

thing the patient reports in the history, a physical

study. Some may seem obvious, such as a patient who

is unconscious, but others are subtler. The scenarios

that follow also take into account some of the unique

challenges of military medicine: austere locations,

limited resources, long transport times, and a diverse

patient population.

Abdominal Pain

-

°

Abdominal pain can be a complex and frustrating

chief complaint for the EP. A recent study showed

that 6.5% of ED patients have abdominal pain as

their presenting complaint, and of these, 21% were

-

nal pain.”

11

A focused history and physical exam can

those patients who need further testing.

Even before the EP sees the patient, her vital signs

indicate she has tachycardia and borderline hypoten-

sion, and is potentially sick. The patient should be

asked more history about her abdominal pain: When

or worse? Are there associated symptoms such as nau-

sea, vomiting, changes in bowel movements, changes

in urination, anorexia, or vaginal bleeding? Does she

have a history of chronic abdominal problems such

bowel disease? Has she had prior abdominal surger-

ies? When was her last menstrual period?

All women and girls of childbearing age, even in the

A pregnancy test is the most important test to order

for this patient because the results will direct further

imaging studies and disposition. A pelvic exam can

be considered if there is concern for pelvic pathology.

Abnormal vital signs must be addressed. If the patient

If she is in pain, she may need either PO or IV pain

medication. Most abdominal pain patients should

initially be kept NPO (nil per os, or nothing by mouth)

until a surgical emergency is excluded.

-

This patient must be worked up for ectopic preg-

nancy, a potentially life-threatening condition in which

the fetus implants outside of the uterus, usually in the

ovarian tube. The patient should be kept NPO. Appro-

priate labs to consider include complete blood count

to evaluate for anemia given her history of vaginal

bleeding, basic metabolic panel, quantitative human

chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), and blood type and

IV pain medications. A pelvic ultrasound should be

performed, which can be used not only to identify an

ectopic pregnancy, but also to evaluate other serious

causes of abdominal pain such as an ovarian torsion or

tuboovarian abscess (Exhibit 32-1). A skilled EP may

be able to perform this test at the bedside. Depending

on the facility’s resources, ultrasound technicians and

radiologists may be available to perform and interpret

the study.

463

Approach to the Emergency Patient

EXHIBIT 32-1

ABDOMINAL PAIN:

CAN’T-MISS DIAGNOSES

• perforated ulcer

• cholecystitis

• pancreatitis

• ischemic bowel

• diverticulitis

• appendicitis

• pyelonephritis

• ectopic pregnancy

• ovarian torsion

• testicular torsion

• tuboovarian abscess

• pelvic inflammatory disease

• myocardial infarction

• bowel obstruction

• volvulus

• gastrointestinal bleed

• abdominal aortic aneurysm

This exam is concerning for a ruptured ectopic preg-

nancy: a surgical emergency. The patient may be losing

bedside FAST (focused abdominal sonographic study

the abdomen (Figure 32-1). A FAST exam is a rapid,

bedside test that can be used to evaluate for the pres-

Figure 32-1. Ultrasound showing ruptured ectopic preg-

nancy.

the capability, the patient should go to the operating

room with a gynecologist for surgical repair. If those

resources are not available, she should be immediately

transferred to the nearest facility with surgical capabil-

ity, which may include transfer to a general surgeon

if a gynecologist is unavailable.

The presence of abnormal vital signs, and especially

worsening vital signs throughout a patient’s visit,

should warn the EP there might be a life-threatening

problem. Rebound and guarding on physical exam

are concerning for a ruptured viscus. In this case, the

-

ent clinical scenario, rebound tenderness may be a sign

of appendicitis, cholecystitis, diverticulitis, perforated

peptic ulcer, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm,

or other serious conditions. These patients all need

prompt surgical consultation.

problems, acidosis, and severe anemia may also

prompt admission or transfer. Stable abdominal pain

patients with normal vital signs and reassuring physi-

and with non-concerning labs and imaging studies (as

indicated), may possibly be safely discharged to quar-

ters or full duty. Discharged patients with abdominal

pain should have a repeat abdominal exam in 24 to 48

-

tions to return sooner for worsening or concerning

symptoms. These return precautions may include

worsening pain, persistent vomiting, high fevers, or

other new concerns. If the patient is unable to follow

up with their primary care physician, it is reasonable

to have them return to the ED.

Chest Pain

°

Chest pain accounts for 3% of ED visits and can

range from common active duty problems such as

muscle strains, costochondritis, and viral syndromes

to truly life-threatening etiologies.

12

Six life-threatening

causes of chest pain a provider should consider in

every chest pain patient are acute coronary syndrome,

464

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

pulmonary embolus, aortic dissection, hemothorax,

pneumothorax, esophageal rupture, and pneumonia

(Exhibit 32-2). Before any chest pain patient can leave

the ED, these diagnoses should be ruled out, either by

history and physical exam or with diagnostic testing.

The patient should be asked to describe his chest

pain: when did it start? What does it feel like? What

-

toms such as shortness of breath, nausea, diaphoresis,

or cough? He should be questioned about his risk

factors for acute coronary syndrome, such as smok-

ing, family history, hypertension, hyperlipidemia,

and diabetes. He should also be questioned about

risk factors for a pulmonary embolus: smoking, pro-

longed immobility, leg swelling, family history, and

known hypercoaguable disorder. In any chest pain

patient, it is important to conduct a thorough review

of systems and inquire about recent fevers, coughing,

or other illness, as well as recent cardiac or esophageal

procedures.

Physical exam should focus on cardiopulmonary

and abdominal exams, as well as assessing the extremi-

ties for peripheral edema and distal pulses, and the

neck for jugular venous distension. All chest pain pa-

tients should quickly have an electrocardiogram (ECG)

performed and interpreted by an EP. The American

College of Emergency Physicians and the American

College of Cardiology recommend that an ECG be

performed within 10 minutes of arrival for all patients

with chest pain.

12

Most EDs have quality standards

that require an ECG to be performed and interpreted

by an EP within 10 to 15 minutes of a patient’s arrival.

EXHIBIT 32-2

CHEST PAIN:

CAN’T-MISS DIAGNOSES

• acute coronary syndrome

o unstable angina

o ST elevation myocardial infarction

o non-ST elevation myocardial infarction

• aortic dissection

• pulmonary embolism

• pneumothorax

• hemothorax

• pneumonia

• esophageal rupture

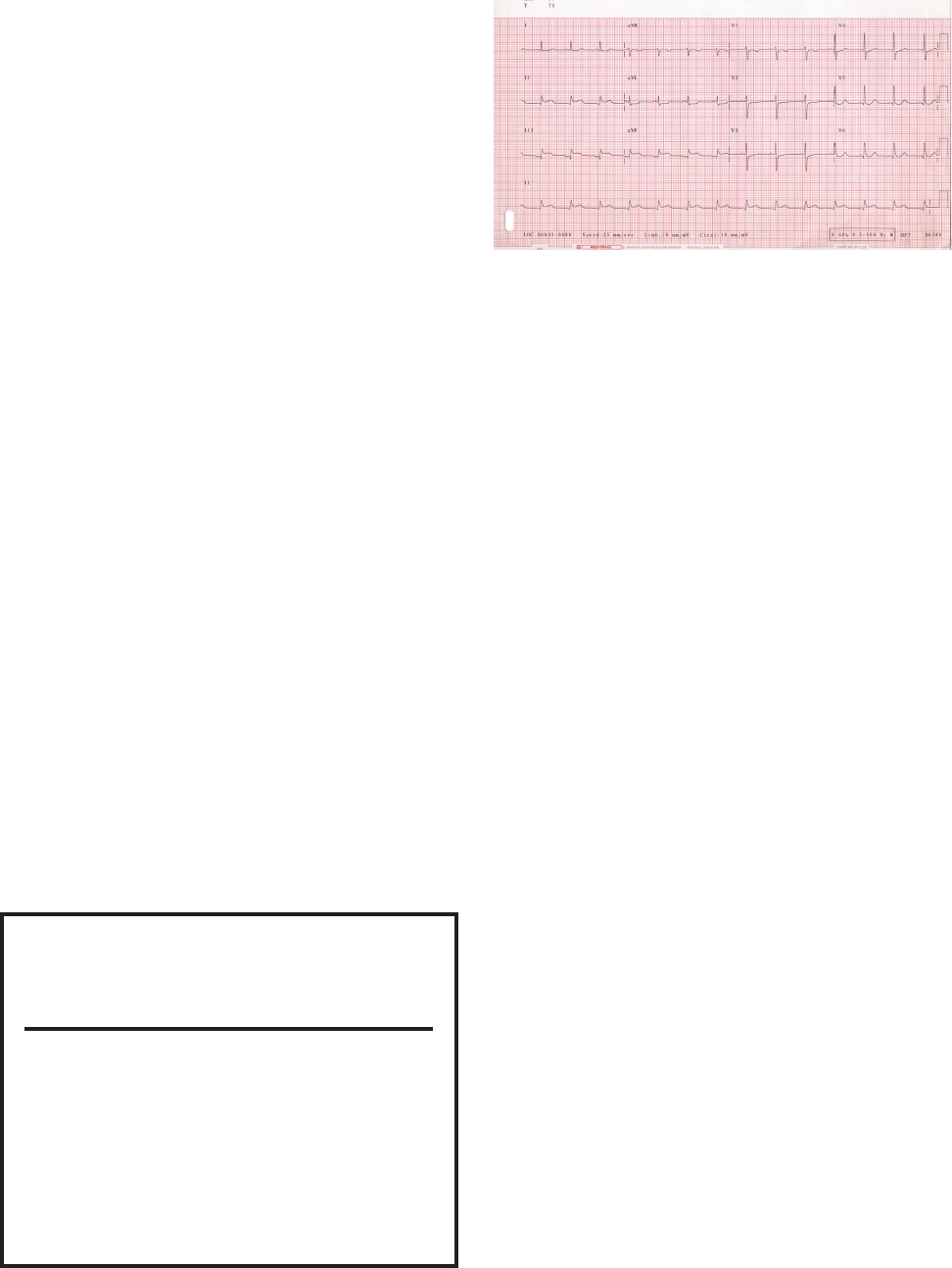

The ECG shows an ST-elevation myocardial

infarction (STEMI)—a true cardiac emergency. ST

elevation on ECG indicates that damage (infarction)

is occurring throughout all layers of the heart muscle.

A thrombus (clot) has occluded blood supply to part

of the heart, and heart muscle tissue is dying.

13

Once

this is diagnosed, the EP must immediately initiate

treatment, potentially before a full history or physical

exam can be obtained. The patient should be placed

on oxygen and should receive aspirin. He should

receive nitroglycerin for ongoing pain. However,

nitroglycerin can drop a patient’s blood pressure and

should be used judiciously once IV access has been

becomes hypotensive).

In many stateside military and civilian facilities,

STEMI patients are taken immediately to the cardiac

catheterization lab to undergo an invasive procedure

this resource is usually not available. Instead, patients

can be given thrombolytics, which are IV medications

that help break up the clot. These medications all

carry risks of bleeding complications, and the patient

After receiving thrombolytics, the patient will likely

require transport to a higher level of care for cardiol-

ogy consultation and intensive care management. In

this case, the STEMI seen on ECG makes the patient’s

disposition easy for the EP. But what if his ECG had

There are many other life-threatening causes of

chest pain that can present with a normal or nonspe-

Figure 32-2. Twelve-lead electrocardiogram with ST seg-

ment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF for an inferior acute

myocardial infarction. April 12, 2005.

Reproduced from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

465

Approach to the Emergency Patient

work and imaging performed. A chest x-ray can be

-

mothorax or pneumonia. If there is a high suspicion for

an aortic dissection or pulmonary embolus, a CT of the

chest with IV contrast should be obtained, because they

are not readily diagnosed with a standard chest x-ray.

Elevated cardiac enzymes may clinch the diagnosis of

MI in a patient with a borderline ECG.

Many patients who present to the ED with chest

who are older and have risk factors for acute coronary

threatening causes of chest pain without a period of

observation. Patients with potential cardiac risk factors

and no etiology of their chest pain found in the ED

require observation, repeat exams, repeat ECGs, and

serial cardiac enzyme screens in addition to some form

of stress test. According to the resources at a facility,

this process may be done in the ED, a chest pain obser-

vation unit, or an inpatient ward, or via a coordinated

outpatient approach. All patients who are discharged

with a diagnosis of chest pain should have close follow-

up with their primary care physician or appropriate

specialist and should be given clear return precautions.

Headache

Three-quarters of Americans experience a head-

ache each year, and headaches account for 2 million

ED visits.

14

Most of these patients have a primary

headache disorder such as migraines, cluster head-

aches, or tension-type headaches, and can be treated

symptomatically and discharged. However, a subset

have a “secondary” headache: a pathologic process

such as a tumor or vascular event in which head pain

is the presenting symptom. To help distinguish be-

tween a regular migraine headache and a headache

with a potentially more serious cause (Exhibit 32-3),

the patient should be asked additional questions.

How did the pain start? What does it feel like? Does

located? What time of day is it worse? What medica-

tions are you taking? Are there associated symptoms

such as fever, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, or

EXHIBIT 32-3

HEADACHE:

CAN’T-MISS DIAGNOSES

• intracranial hemorrhage

• meningitis

• intracranial mass

• cerebrovascular accident

• acute angle closure glaucoma

• hypertensive encephalopathy

is concerning for meningitis, a life-threatening infec-

Many medications such as nitroglycerin, calcium

of headache, and many recreational drugs can cause

headaches as well. If the patient has recently decreased

headache. Multiple members of a family with new

headaches, especially in the winter months, should

raise suspicion for carbon monoxide poisoning.

14

New headaches that worsen over a period of weeks,

especially headaches that are worse in the morning,

are concerning for elevated intracranial pressure from

a mass lesion or neoplasm.

-

Pain that is abrupt and maximal at onset is concerning

for a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

14

The patient will need

IV access, a careful neurological exam, and immediate

non-contrast head CT. Except for glaucoma patients,

virtually all patients presenting with headache should

receive analgesia and should be kept in a quiet, dark

area.

All patients with headaches also require a thorough

neurological exam. Tenderness over the sinuses or

purulent drainage from the nose could indicate sinus-

itis. In elderly patients, the temporal arteries should

be palpated to evaluate for temporal arteritis. Acute

angle closure glaucoma can present with headache in

addition to visual changes, conjunctival injection, and

pupillary changes. If this diagnosis is suspected, pa-

tients should have their intraocular pressures checked.

for further imaging. Patients with altered mental status

or new onset seizures also require further imaging.

466

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

. What are your

The patient’s CT scan shows a subarachnoid hemor-

rhage—a neurosurgical emergency. In the ED, the ini-

tial management involves resuscitation, reversal of any

coagulopathies, and stabilization. The patient should

carefully monitored. She will need frequent neurologi-

cal exams, and if her neurological status deteriorates

further, she will require intubation for airway protec-

tion. She will require neurosurgical consultation and

to be monitored for additional bleeding, vasospasm,

-

tory drugs, aspirin, and other blood-thinners should

be avoided when treating her pain.

In managing headaches, special care should be giv-

en to certain populations. The elderly are unlikely to

develop new onset migraines, and are at much higher

risk for chronic subdural hematomas that can present

with only mild headaches. Physicians should have a

low threshold to order a CT scan on elderly patients

with new onset headaches.

14

In pregnant patients,

untreated, this condition can progress to eclampsia,

cerebral hemorrhage, or both. Most headache patients

with stable vital signs, a normal neurological exam,

Figure 32-3. Computed tomography head scan showing

subarachnoid hemorrhage.

-

diagnosis.

Trauma

-

According to the Joint Theater Trauma Registry

(JTTR), most combat-related injuries in Operation

Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom

occurred as a result of injury from explosions (78%),

usually IEDs. Due to improvements in body armor,

there was a low rate of thoracic injuries. The highest

rate of injury was to the extremities (54%), followed

by the abdomen, face, and head. JTTR statistics show

that hemorrhage is the leading cause of potentially

preventable combat-related death. Tactical Combat

Casualty Care (TCCC) principles and practice have

greatly reduced mortality from hemorrhage, along

with damage control resuscitation and surgery, rapid

patient evacuation, and sophisticated patient transport

mechanisms.

15

Initial stabilization of trauma patients in the de-

lifesaver or combat medic. Most medics and physicians

(discussed in Chapter 33, Tactical Medicine), and the

EP will likely also have been trained in Advanced

Trauma Life Support. Both of these courses provide a

standard, algorithmic approach to managing trauma

that focuses on immediate stabilization of the patient’s

life-threatening injuries. The pneumonic “XABCDE”

can be used to remember the sequence of care in a

then move on to airway, breathing, and circulation,

followed by disability and exposure. When a threat

to survival is found, it must be rapidly addressed and

-

467

Approach to the Emergency Patient

This collection of vital signs and physical exam

respiratory emergency and form of obstructive shock.

to hypoxia and hypotension from decreased venous

return and pressure on the heart. The patient should

undergo immediate needle decompression with a

14-gauge needle followed by chest tube insertion.

Circulation can be assessed quickly by palpating

pulses. A palpable radial pulse indicates a systolic BP

of at least 80, and a palpable femoral or carotid pulse

indicates a BP of at least 60. Tachycardia and hypo-

tension can be signs of shock, but it is important to

in a healthy, active duty population. Certain trauma

patients, such as the elderly, those in neurogenic shock,

and those taking beta-blocker medications, may not

be able to mount a tachycardic response. In any case,

hemorrhagic shock should be treated aggressively

The patient should have a quick evaluation of his

mental status (D for disability). This can be performed

using the pneumonic “AVPU”: alert/awake, verbal,

painful, or unresponsive (Exhibit 32-4). Is the patient

fully awake? Does he only respond to voice? Does he

only respond to painful stimuli, or is he completely

unresponsive? Also, he should be exposed from head

to toe to evaluate for any additional injuries.

At this point in evaluation, additional studies are

often performed as adjuncts to the primary survey.

A positive FAST exam in an unstable patient is an

indication for operative intervention. Trauma x-rays

(usually with portable chest x-ray and portable pelvis

EXHIBIT 32-4

“AVPU” SCALE FOR CONSCIOUSNESS

ASSESSMENT

• Alert. The patient is alert and awake.

• Verbal. The patient responds to verbal stimuli.

• Pain. The patient responds to painful stimuli.

• Unresponsive. The patient is unresponsive.

x-ray devices) are also performed at this point. A CT

injuries (Exhibit 32-5).

Once the XABCDEs have been performed and im-

mediate life threats addressed, the patient should be

asked additional history and should undergo a head-

to-toe secondary survey. A pneumonic to guide the

additional history is “AMPLE”: allergies, medications,

past illnesses, last meal, and events involved in the

trauma. The secondary survey consists of a systematic

assessment of the patient, inspecting and palpating all

body parts for injuries while also performing a more

thorough neurological exam. As these steps are per-

formed, a nurse or tech should send a panel of blood

work to the lab. Depending on the nature and severity

of the trauma, these may include a type and cross for

blood, complete blood count, basic metabolic panel,

lactate, coagulation panel, urinalysis, alcohol level,

and drug screen. After these steps are completed, ad-

ditional imaging can be ordered based on the results of

the secondary survey and suspected injuries. This may

include extremity x-rays, a retrograde urethrogram

or cystogram, and CT scans of the head, spine, chest,

abdomen, and pelvis.

16

-

EXHIBIT 32-5

TRAUMA:

CAN’T-MISS DIAGNOSES

• shock

• airway compromise

• tension pneumothorax

• massive hemothorax

• open pneumothorax

• flail chest

• cardiac tamponade

• brain herniation

• aortic disruption

• spinal injuries

• pelvic ring disruption

• hemoperitoneum

468

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

Figure 32-4. Chest x-ray showing right-sided pneumothorax.

Figure 32-5. Computed tomography head scan showing

subdural hematoma.

The patient’s subdural hematoma will require ur-

gent neurosurgical evaluation and possible surgery

if his neurological status deteriorates. This is a case

in which the deployed environment provides unique

challenges. The patient presented to the ED at a multi-

national hospital, where a neurosurgeon is likely avail-

able. If he had presented further forward, he would

have required evacuation, possibly by a critical care air

transport (CCATT) or tactical critical care evacuation

(TCCET) team, to get him to neurosurgical care in an

-

agement of his chest tube, neurosurgical evaluation

of his subdural hematoma, and orthopedics, trauma,

and/or vascular evaluation of his amputation. Once

these conditions have stabilized to the point where he

of theater by a CCATT team.

Shock

-

-

Shock refers to a state of hypoperfusion in which

oxygen delivery to the tissues is inadequate to meet the

metabolic demands of the body. Broadly speaking, it is

and supply that results in cellular death.

17

If shock is

not rapidly treated, it leads to end-organ failure and

death. There are four broad categories of shock: hy-

povolemic, cardiogenic, distributive, and obstructive

(Table 32-1).

17

Hypovolemic shock is the most common, especially

circulatory volume, most commonly from hemorrhage

or dehydration. Treatment focuses on volume expan-

sion with blood, crystalloid, or both as indicated.

18

Cardiogenic shock is caused by cardiac dysfunction,

usually from an MI, and the heart pump is unable to

meet the demands of the body’s tissues. Treatment

support, and reperfusion therapy for MI. Obstructive

shock involves some blockage of blood leading into

or out of the heart, either from a physical blockage

such as a massive pulmonary embolus, or a pressure-

gradient blockage caused by a tension pneumothorax

or cardiac tamponade. The causes of obstructive shock

may all present as pulseless electrical activity (PEA)

and should all be considered when working through

the “H”s and “T”s during a code (see the Cardiac Ar-

rest section below). Lastly, distributive shock results in

469

Approach to the Emergency Patient

TABLE 32-1

CATEGORIES AND CAUSES OF SHOCK

Category Causes

Hypovolemic Trauma

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Severe dehydration (gastroenteritis,

burns)

Cardiogenic Acute myocardial infarction

Rate problems: bradycardia or tachycardia

Toxins

Cardiomyopathy

Distributive Sepsis

Anaphylaxis

Neurogenic

Toxins

Obstructive Pericardial tamponade

Pulmonary embolism

Tension pneumothorax

mediators and cytokines, which leads to a decrease

in systemic vascular resistance and a compensatory

increase in cardiac output. Sepsis is the most common

cause, but anaphylaxis, neurological injuries, and cer-

tain toxins can also cause this presentation.

17

Patients with shock require the EP’s immediate

-

taneously with the history and exam, and before

diagnosing the shock state’s etiology. The EP should

rapidly assess the patient’s general appearance and

vital signs. Patients in shock will often be hypoten-

sive, tachycardic, and tachypneic. If the patient has

respiratory distress or is unable to protect his airway

secondary to confusion, he may require intubation.

Supplemental oxygen should be considered for all

Patients in septic shock in particular may require

-

sure does not improve after 1 to 2 L of crystalloid,

or if the patient is unable to tolerate large volumes

heart failure), vasoactive medications, such as norepi-

nephrine or dopamine, may be required to increase

blood pressure and improve tissue perfusion. All

patients presumed to be in septic shock should have

labs ordered to look for the source of infection (blood

tests, etc) and be started on early, broad-spectrum

antibiotic therapy. As the patient is stabilized, the EP

can obtain a more detailed history and perform a full

physical exam.

In this case, a more thorough history and exam

points to a clear etiology for the patient’s symptoms:

distributive shock secondary to anaphylaxis from a

bee sting. The mainstay of treatment for anaphylaxis is

-

teract vasodilation and bronchospasm. Epinephrine is

typically given subcutaneously initially, but may also

be given via an IV route.

18

-

Patients with this type of shock may sometimes be

discharged from the ED. Patients with anaphylaxis

who are asymptomatic after one dose of epinephrine

can be observed for 4 to 6 hours and, if they remain

asymptomatic, safely discharged. Observation is

necessary because some patients may require a

repeat dose of epinephrine. Nearly all other patients

who present in shock will require admission, often

to the ICU, for continued fluid resuscitation and

patients in shock are stabilized and then transported

out of theater by CCATT, whose staff are able to

continue treatment with vasoactive medications, blood

level of care. Indicators that shock has resolved include

normalization of vital signs, improved urine output,

down-trending lactate, and normal volume status.

18

It is important to remember that certain special

most common causes of shock are dehydration second-

ary to infectious gastroenteritis and hemorrhagic shock

secondary to trauma.

17

Pediatric patients are able to

compensate for a large amount of volume loss with

minimal change in vital signs. Thus, they can appear

470

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

well even in the early stages in shock. When these

compensatory mechanisms fail, they will deteriorate

rapidly, and the EP must be ready to intervene. In

contrast, the elderly have limited reserves and are often

unable to tolerate the hemodynamic changes of shock.

The elderly are more susceptible to infectious diseases

and are also more likely to present with cardiogenic

shock. Underlying comorbidities such as cardiac or

renal disease may make them unable to tolerate ag-

them closely for the development of complications

such as pulmonary edema.

Poisoning

-

Poisonings, whether from an accidental or inten-

of toxicology is a subspecialty of emergency medicine.

It is estimated that at least 5 million poisonings occur in

the United States each year, although the actual num-

ber may be even higher due to underreporting.

19

The

poisoned ED patient can present in conditions rang-

ing from completely awake, alert, and asymptomatic

to completely obtunded with unstable vital signs. As

with any ED patient, assessment begins as soon as the

EP looks at the patient and continues with the ABCs.

Initial priorities are securing the patient’s airway

and treating potentially reversible causes of her altered

mental status. These treatments, often referred to as the

“coma cocktail,” include 100% oxygen to treat hypoxia,

(followed by the administration of dextrose if glucose

is low), and naloxone to reverse an opioid overdose. If

chronic alcoholism is suspected, thiamine can be given

before glucose. If the patient is obtunded, the airway

should be secured with intubation. Many toxins can

rate, salicylates can increase the respiratory rate and

cause pulmonary edema, and various inhalants may

cause bronchospasm. As the ABCs are addressed and

concerning conditions stabilized, the EP must also re-

member to place the patient on “suicide watch” with

20

If the patient is able to talk, or if there are others

who can provide the history, it is important to ask the

following questions: What was ingested? How much

was ingested? When did this occur? Why? (Was it an

accidental or intentional overdose?) A head-to-toe

physical exam should be performed on all patients,

-

tus, pupils, skin, and presence of track marks or other

evidence of drug use. Some poisonings cause common,

recognizable “toxidromes,” described in Exhibit 32-6.

20

-

-

Although additional history has helped identify the

patient’s likely ingestion, she should still undergo a

broad workup to look for complications of her inges-

tion and to identify any possible co-ingestions. Most

acutely poisoned patients are worked up with cardiac

EXHIBIT 32-6

POISONING “TOXIDROMES”

Anticholinergic

• mad as a hatter (altered mental status)

• blind as a bat (mydriasis)

• hot as Hades

• red as a beet

• dry as a bone

Cholinergic

• salivation

• lacrimation

• urination

• defecation

• gastrointestinal upset

• excessive bradycardia

Sympathomimetic

• tachycardia

• hypertension

• mydriasis

• diaphoresis

• hyperthermia

• agitation

Opioid

• miosis

• apnea

• hypoxia

• flash pulmonary edema (rare)

471

Approach to the Emergency Patient

monitoring; an ECG; complete blood count; compre-

hensive metabolic panel, acetaminophen, salicylate,

and ethanol levels; urinalysis; and urine or serum drug

screen. Females of childbearing age should be tested

for pregnancy. If the patient has metabolic acidosis,

a serum osmolality may help further narrow the dif-

ferential. Other than acetaminophen, salicylates, and

are usually sent to a lab, but results take several days.

The EP must treat presumptively based on the history,

In treating the poisoned patient, the EP must

consider methods of preventing absorption or aid-

ing elimination of the toxin. These include activated

charcoal, whole bowel irrigation, and gastric lavage.

Activated charcoal is given PO or via nasogastric tube

to absorb toxins still in the gastrointestinal tract. It is

but is occasionally given later for extended-release

toxins or potentially lethal ingestions.

21

It does not bind

metals, alcohols, or hydrocarbons and should be used

cautiously in patients with altered mental status, who

are at increased risk for aspiration.

Whole bowel irrigation is infrequently utilized and

involves giving the patient polyethylene glycol solu-

tion (eg, GoLytely [Braintree Laboratories; Braintree,

of a toxin. It is occasionally used for patients who have

ingested extended-release preparations and patients

with illicit drug packet ingestions (“body packers”).

Gastric lavage is seldom performed due to a high risk

patient presents immediately after a lethal ingestion,

pill fragments from the stomach.

19

Acetaminophen is one of the most common and

most dangerous ingestions seen in the ED. Because

an acute ingestion will often have minimal symp-

toms, and because the potential for long-term liver

damage is high, the EP should consider checking

acetaminophen levels for every poisoned patient. In

overdose, acetaminophen is metabolized to N-acetyl-

p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), which causes liver

nomogram. A level of 150 or greater at 4 hours is con-

sidered toxic. Patients with a toxic ingestion should

be started on the antidote, N-acetylcysteine. Starting

this antidote promptly after ingestion can prevent liver

damage and death.

N

often to the ICU, for close cardiopulmonary monitor-

ing. If a poisoned patient is asymptomatic after several

hours of observation in the ED, they may possibly be

safe for discharge after psychiatric evaluation. Con-

sultation with a poison control center, if available, is

present with an intentional ingestion as a suicide at-

tempt will likely need to be removed from theater and

transported back to the United States for psychiatric

treatment.

Cardiac Arrest

An estimated 250,000 Americans die each year from

unexpected cardiac arrest. Many of these cases occur

outside of a hospital, and most occur in men aged 50 to

75 who have underlying heart disease.

22

In a way, the

cardiac arrest patient is the quintessential emergency

medicine patient: obviously sick and in need of rapid

assessment and interventions that, if performed cor-

Managing a cardiac arrest and its aftermath can be an

intellectually stimulating yet emotionally draining

experience for the EP. In an arrest, the EP will end up

treating not only the patient, but also his or her family,

who will require extensive explanation and support,

whatever the outcome.

The initial goals in managing a cardiac arrest

include the principles of BLS: to “support or restore

return of spontaneous circulation or until ACLS [ad-

vanced cardiac life support] interventions can be initi-

ated.”

23

chest compressions. The old pneumonic “ABC” has

been altered to “CAB” for these patients to shift focus

-

ers should check for a carotid pulse for no more than

10 seconds. If no pulse is present, responders should

472

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

start cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), pushing

hard and fast, 100 to 120 compressions per minute,

and allowing full chest recoil between compressions.

The patient should receive two rescue breaths with a

pocket mask or bag valve mask between compressions.

The airway should be opened with a head tilt, chin

patient should be shocked as recommended by the

23

As more advanced practitioners arrive on scene,

and once the patient arrives in the ED, more advanced

resuscitation techniques can be started. The ACLS pro-

also includes advanced airway techniques, such as in-

tubation, and IV medications such as epinephrine and

amiodarone. End-tidal capnography can be a useful

and the correct placement of the endotracheal tube.

Cardiac arrest from a primary cardiac disorder often

presents with this rhythm or with pulseless ventricular

tachycardia, which is treated in the same manner. In

patients return to their baseline neurological status.

23

and IV amiodarone. IV access should be obtained as

quickly as possible, and if IV access is not immedi-

ately available, an interosseous line should be placed

instead. Many ACLS medications can also be given

via the endotracheal tube, but given the widespread

availability of interosseous lines and their ease of in-

sertion, the endotracheal tube method is being used

be rapidly obtained because hypoglycemia can be a

rapidly reversible cause of altered mental status and

cardiac arrest.

associated mechanical pumping.

23

Successful resuscita-

tion of a patient in PEA should be focused on rapidly

identifying and treating the cause. The EP may think

of the “H”s and “T”s (Exhibit 32-7) to remember all the

potential causes of PEA. All patients in PEA should be

treated with oxygen and ideally intubated to correct for

-

cose screen can rapidly identify hypoglycemia. Blood

that is rapidly run through an i-STAT machine (Ab-

hypokalemia or hyperkalemia and acidosis. Patients

in PEA should be kept warm. A bedside ultrasound

can be performed to evaluate for cardiac tamponade

and to evaluate the right side of the heart for changes

consistent with a large pulmonary embolus. Based

on the clinical scenario, the patient may require an

emergent pericardiocentesis to treat a tamponade,

Figure 32-6. Rhythm strip showing ventricular fibrillation.

Reproduced from: https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/

ECGpedia).png.

Figure 32-7. Rhythm strip showing pulseless electrical

activity.

Reproduced from: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/

EXHIBIT 32-7

CARDIAC ARREST “H”S AND “T”s

• hypovolemia

• hypoxia

• hydrogen ion (acidosis)

• hyper/hypokalemia

• hypoglycemia

• hypothermia

• toxins

• tamponade (cardiac)

• tension pneumothorax

• thrombosis (acute coronary syndrome and pul-

monary embolism)

473

Approach to the Emergency Patient

needle decompression for tension pneumothorax, or

IV thrombolytics for suspected pulmonary embolus

or MI. The patient should continue to receive high-

quality CPR and IV epinephrine every 3 to 5 minutes.

If a reversible cause of PEA is not rapidly discovered

and corrected, the patient’s prognosis is extremely

poor. Only 1% to 4% of patients with PEA survive to

hospital discharge

24

(see Exhibit 32-7).

-

Asystole has a very poor prognosis because even

minutes without oxygen to the brain portends very

poor functional outcomes. For patients in asystole,

treatment should still be focused on restoring perfu-

sion with high-quality CPR and identifying a reversible

cause. After 20 minutes of combined BLS and ACLS,

resuscitation is unlikely to be successful. Bedside ultra-

sound can be a useful adjunct in evaluating for cardiac

activity. If the patient has been in asystole for 20 min-

utes and shows no cardiac activity on ultrasound, it

then ensure that the patient’s family is updated and

their questions are answered. If possible, the patient’s

primary care doctor should be contacted as well.

Only a small percentage of resuscitated cardiac

arrest patients survive to hospital discharge, and of

Figure 32-8. Rhythm strip showing asystole.

Reproduced from: https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/

injury. If the patient regains a pulse but does not

regain consciousness, the EP should initiate targeted

temperature management. Randomized control trials

versus targeted temperature management. Maintain-

ing a constant temperature between 32° and 36°C

for at least 24 hours postarrest is the current recom-

mendation, and this has been shown to improve both

survival rates to hospital discharge and neurological

outcomes.

24

The procedure is usually started in the ED

If acute coronary syndrome is suspected, the postarrest

patient should be strongly considered for emergent

cardiac catheterization.

Case-Based Approach Summary

The above cases are only a sample of the life-

threatening chief complaints an EP may encounter.

They are meant to emphasize the common processes

in the approach to the emergency medicine patient,

regardless of initial patient complaint. In these cases,

the EP must quickly determine whether the patient is

“sick or not sick.” Another key skill is the ability of the

EP to simultaneously obtain history and diagnoses,

while starting to treat the patient. Unlike the orderly,

thorough approach to the patient history taught in

medical schools, the EP must quickly obtain basic his-

tory while simultaneously relaying orders to nurses

and technicians and rapidly thinking through a list

of “can’t miss/worst case scenario” diagnoses. This is

often done with incomplete records and potentially

no help from the patient themselves if they are in

extremis. These cases also emphasize the challenges

in diagnosis and treatment based on the EP’s practice

environment: forward deployed location, theater hos-

pital, or stateside medical facility. Once initial patient

stabilization is complete, the EP can focus on the next

phase of patient care: disposition.

DISPOSITION

Potential dispositions from the ED include admis-

sion to the hospital for observation, additional workup,

facility with a higher level of care; discharge home or

to self-care; and of course, unfortunately, transfer to

the morgue. The EP must consider numerous factors to

determine the most appropriate place for disposition.

For example, considering a terminal patient whose

primary issue is managing pain and maintaining qual-

ity of life, sending them home may be the best course.

Their terminal disease will not be cured by a hospital

admission, and admission can in fact be detrimental

(the hospital can expose patients to numerous noso-

comial infections and be less comfortable). Discharge

home is appropriate as long as pain medications can

be administered at home.

The decision to admit or discharge a patient is

one of the unique challenges of emergency medicine.

The EP must make this decision in a timely manner,

often with an incomplete history of present illness,

minimal to no knowledge of the patient’s past medi-

cal history, and equivocal testing. Although this can

474

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

with a patient. Performing serial examinations and

discussing the case with a consultant can help the

EP decide.

When collaborating with consultants, it is essen-

tial that the EP remain an advocate for the patient.

Consultants generally prefer brief presentations

previous chest pain patient, a consulting cardiolo-

gist might expect to hear, “I have a 55-year-old man

with multiple cardiac risk factors who presents with

a STEMI on ECG. We have treated him with aspirin,

nitroglycerin, and heparin, and would like him to go

to the cath lab. Could you come evaluate him in the

ED? Are there any other treatments you would like us

to start?” Depending on the case and resources at the

facility, a consultant may evaluate the patient in the

ED and ultimately discharge him, admit the patient

primarily, or manage the patient alongside another

service (usually internal medicine). When possible, it

them in person rather than providing advice over

the phone. In many EDs, and especially in austere or

Specialist consultants may be in other parts of the

country or region, or stateside. In these cases, sending

pictures of ECGs and other images to the consultant

may be the next best course of action. Some hospitals

have telemedicine services, in which a consultant

(often a neurologist for a stroke patient), can evaluate

the patient via a video monitoring system.

When patients require admission, the EP must de-

or if they require a transfer. In the stateside military

-

fer to a higher level of care; many stateside military

hospitals do not provide neurosurgical capabilities.

The patient presenting with a subarachnoid hemor-

rhage might require transfer to a civilian facility for

an even larger challenge. The deployed patient pre-

senting with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy would

certainly require transfer to a higher level of care for

surgical treatment.

If transfer is required, the EP’s next question is

how to most safely transport the patient: by air or by

ground. This decision will rely on a multitude of fac-

tors including the stability of the patient, the resources

of the facility, weather conditions, and the location

of the accepting hospital. This decision will often be

made in consultation with the accepting provider at

the next level of care.

EP may need to write admission orders for the inpa-

tient unit. These should be done in consultation with

may require phone calls to multiple consultants to

coordinate care.

Many patients can be safely discharged from the

ED. However, the decision to discharge can produce

anxiety for the EP and for the patient, especially if the

patient is being discharged without a clear diagnosis.

As discussed throughout the chapter, the purpose of

an evaluation in an ED is to recognize and stabilize

life-threatening conditions. Often, a skilled EP is able

to determine that there is no life-threatening condi-

tion present and no reason for admission, but the

cause of the patient’s chest pain, abdominal pain, or

other symptom, is still unclear. In these circumstanc-

es, the EP must have a discussion with the patient

about what has been done in the ED, what the next

steps should be (primary care follow-up, outpatient

follow-up with a specialist, further testing as an out-

patient, trial of medication, etc), and any reasons to

return to the ED.

Patients should be told what they should do to

improve their condition, for example, ice, rest, eleva-

sprain. What the patient is NOT allowed to do should

seizure may be stable for discharge with outpatient

neurology follow-up, but should be counseled not

to drive or engage in other high-risk activities. In the

patients with mild traumatic brain injury/concussion

may be in a condition to be discharged, but should be

counseled to avoid all strenuous physical activity until

headache and other symptoms completely resolve and

they have been cleared by their primary care doctor

or neurologist.

Patients should be told when and where to follow

up. For high-risk patients such as infants, pregnant

women, and the elderly, and for high-risk complaints

such as abdominal pain and chest pain, it is preferable

patient to follow up, ideally in 24 to 48 hours, for a

repeat evaluation. If this is not possible and the EP is

truly concerned for the patient, the best option may be

to have the patient return to the ED in 24 to 48 hours

for a recheck. This procedure has often been used for

has not been ruled out.

475

Approach to the Emergency Patient

SUMMARY

The approach to the emergency medicine patient,

involve fundamentals of emergency care during

evaluation and treatment of acute conditions. Perform

rapid “doorway” assessments, determine whether

the patient is sick or not sick, establish a safety net,

diagnostics and treatment. Utilizing lessons in this

chapter can help non-emergency MMPs provide bet-

ter patient care.

REFERENCES

1. Schneider SM, Hamilton GC, Moyer P, Stapczynski JS. Definition of emergency medicine. . 1998;5:348–

351.

2. Mahadevan SV, Garmel GM. A. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press; 2005.

3. American College of Emergency Physicians. The uninsured: Access to medical care. ACEP website. https://www.acep.

org/News-Media-top-banner/The-Uninsured--Access-To-Medical-Care/. Published 2016. Accessed February 12, 2017.

4. Sun BC, Burstin HR, Brennan TA. Predictors and outcomes of frequent emergency department users.

2003;10:320–328.

5. Vinton DT, Capp R, Rooks SP, Abbott JT, Ginde AA. Frequent users of US emergency departments: Characteristics

and opportunities for intervention. . 2014;31(7):526–532. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-202407.

6. Ku BS, Fields JM, Santana A, Wasserman D, Borman L, Scott KC . The urban homeless: super-users of the emergency

department. . 2014;17:366–371. doi:10.1089/pop.2013.0118.

7. Clarke ME, Pierson W. Management of elder abuse in the emergency department. .

1999;17:631–644,vi.

8. McCloskey LA, Lichter E, Ganz ML, et al. Intimate partner violence and patient screening across medical specialties.

2005;12:712–722.

9. Jain AM. Emergency department evaluation of child abuse. . 1999;17:575–593,v.

10. Work RO. . Washington, DC: DoD; August 19, 2014. DoD Directive 2310.01E.

11. Hastings RS, Powers RD. Abdominal pain in the ED: A 35 year retrospective. . 2011;29(7):711–716.

12. American Heart Association. Recommendations for criteria for STEMI systems of care. http://www.heart.org/

HEARTORG/Professional/MissionLifelineHomePage/EMS/Recommendations-for-Criteria-for-STEMI-Systems-of-

13. Antman E. ST-elevation myocardial infarction. In: Fuster V, ed. .

Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009: 55.

14. Lynch KM, Brett F. Headaches that kill: a retrospective study of incidence, etiology and clinical features in cases of

sudden death. . 2012;32:972–798.

15. Beekley AC, Bohman H, Schindler D. Modern warfare. In: Savitsky E, Eastridge B, eds.

. Ft Detrick, MD: Borden Institute; 2012: chap 1. http://www.cs.amedd.army.mil/borden/

book/ccc/UCLAchp1.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Kman NE. Trauma. Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine (CDEM) curriculum. http://www.cdemcurriculum.

. Accessed March 17, 2017.

476

Fundamentals of Military Medicine

17. Oker E. Shock. In: Hamilton H, ed. 2nd ed. Philadelphia,

PA: WB Saunders; 2003: 60–74.

18. Avegno J. Shock. Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine (CDEM) curriculum. http://www.cdemcurriculum.org/

. Updated 2008. Accessed March 17, 2017.

19. Wilson R, Wolf L. The poisoned patient. In: Hamilton H, ed. -

ing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2003: 259–285.

20. Thibodeau L. Poisoning. Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine (CDEM) curriculum. https://cdemcurriculum.

com/poisonings/. Updated 2008. Accessed October 10, 2017.

21. Charcoal, activated. Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/charcoal-activated.html. Accessed January 25,

2018.

22. Lawson L. Cardiac arrest. Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine (CDEM) curriculum. https://cdemcurriculum.

com/cardiac-arrest/. Updated 2008. Accessed October 10, 2017.

23. Leschke R. Cardiopulmonary and cerebral resuscitation. In: Mahadevan S, Garmel G, eds.

. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2005: 47–62.

24. Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines

update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. 2015;132(18 suppl 2):315–367.