DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 359 493

CS 011 348

AUTHOR

Christmas, Jack

TITLE

Developing and Implementing a Plan To Improve the

Reading Achievement of Second Grade Students at

Woodbine Elementary School.

PUB DATE

Feb 93

NOTE

164p.; Ed.D. Major Applied Research Project,

Nova

University.

PUB TYPE

Dissertations/Theses

Undetermined (040)

EDRS PRICE

MF01/PC07 Plus Postage.

DESCRIPTORS

Elementary School Students; Grade 2; Parent

Participation; Primary Education; Program

Effectiveness; Program Implementation; Reading

Achievement; *Reading Aloud to Others; *Reading

Comprehension; *Reading Improvement; Rural Schools;

Socioeconomic Status; Vocabulary Development

IDENTIFIERS

Camden County School District GA

ABSTRACT

A program was designed to improve the reading

achievement of second grade students in

a rural Georgia school. An

analysis of the problem indicated that:

a higher percentage of second

grade students from low socioeconomic conditions

scored lower on

standardized reading achievement tests

than other second grade

students; students who scored lower owned fewer

books than those who

scored higher; and those who scored lower did

less recreational

reading than those who scored higher.

Interventions included a

program of daily oral reading in the classrooms by teachers

and

recruiting parents to enroll their children in

the Woodbine

(Elementary School) Read Aloud Club.

Parents who enrolled their

children in the club agreed to read

aloud to their children on a

daily basis and turn in simple reading

logs to the teachers each

month. As a reward for their parents' read

aloud efforts, the

children received free storybooks of their

choice each month. The

objectives were to improve the students'

reading comprehension, word

reading, and auditory vocabulary using

the Stanford Diagnostic

Reading Test to measure any changes in reading

ability. Test results

indicated a 38.5% increase in auditory

vocabulary, a 46.4% increase

in reading comprehension, and

a 43.6% increase in word reading for

the approximately 70 subjects. (Twenty-seven

tables of data are

included; 53 references, 2 appendixes

of data, a list of educational

objectives, the enrollment form,

a reading log, 2 sample newsletters,

2 newspaper articles, and

a site visitation team report are

attached.) (Author/RS)

***********************************************************************

Reproductions supplied by EDRS

are the best that can be made

*

from the original document.

***********************************************************************

CYZ

Developing and Implementing a Plan to Improve the

Reading Achievement of Second Grade Students at

Woodbine Elementary School

CvZ

;Ts4

by

Jack Christmas

Principal

Woodbine Elementary School

Camden County Schools

Woodbine, Georgia

A Major Applied Research Project Report

submitted in

partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of Doctor of Education

National Ed.D. Program for Educational Leaders

Nova University

$ DEPARTMENT

OF EDUCATION

Otke

DU

of Educatfonat

Research and

Improvement

EOUCATIONAL

RESOURCES

INFORMATION

CENTER (ERIC)

Tem document

has been

reproduced as

recewed from

the perSOn

Or 0,ganfratIOn

ongfnattng

C MfnOf changes

nave b

,e0roductton

qualftY

een made tO

fmCuOve

Po.nts of

',few°, oruntOnS

slated m rola

ocu-

ment do not

neceSsardy represent

OtttC..1

OERI Poston

or ootfcy

February 1961

2

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

*PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS

MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY

-%\c`(\-

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)."

Committee Signature Page

Major Applied Research Project (MARP)

Participant:

Jack Christmas

Cluster and Number:

Jacksonville V

As Major Applied Research Project Committee Chair,

I

affirm that

this report meets the expectations of thA National Ed.D. Program for

Educational Leaders as a representation of applied-field research

resulting in educational improvement.

Ken e

ush, Com ittee Chair

/

4' nature

Ace/

9

Date

As Major Applied Research Project Committee Reader,

I affirm that

this report meets the expectations of the National Ed.D. Program for

Educational Leaders af; a representation of applied-field research

resulting

in educational improvement.

Joan Mignerey, Committee Reader

As Major Applied Research Project University Representative,

I

affirm that this report meets the expectations of the National Ed.D.

Program for Educational Leaders as a representation of applied-field

research resulting in educational improvement.

Thrisha G. Shiver, Univer

y Representative

Signature

ii

93

Date

Permission Statement

As a participant in the National Ed.D. Program for Educational

Leaders,

I do give permission to Nova University to distribute copies

of the Major Applied Research Project report on request from

interested individuals.

It

is my understanding that Nova University

will not charge for this dissemination except to cover the costs of

microfiche reproduction, handling, and mailing of materials.

Participant signature

3/7 43

date

As editor of the Camden County Tribune, I do give permission to Nova

University to distribute copies of news articles printed in the

Camden County Tribune that are related to this Major Applied

Research Project.

It is my understanding that the news articles

from the Camden County Tribune will be used only for educational

purposes, and Nova University will not charge for the dissemination

except to cover the costs of microfiche reproduction, handling, and

mailing of materials.

347- q3

Signature

date

As editor of the Southeast Georgian, I do give permission to Nova

University to distribute copies of news articles printed in the

Southeast Georgian that are related to this Major Applied Research

Project.

It is my understanding that the news articles from the

Southeast Georgian will be used only for educational purposes, and

Nova University will not charge for the dissemination except to

cover the costs of microfiche reproduction, handling, and mailing of

mataria s.

7Lizr-/ (

iii

date

Abstract

Developing and Implementing a Plan to Improve the

Reading Achievement of Second Grade Students at Woodbine

Elementary School

This report describes a program designed to improve the reading

achievement of second grade students in a rural Georgia school.

An

analysis of the problem indicated that a higher percentage of second

grade students from iow socioeconomic conditions scored lower

on

standardized reading achievement tests than other second grade

students in the school. One of the probable causes for low reading

achievement was related to the number of books students owned.

Students who scored low on reading achievement tests owned fewer

books than students who scored higher.

Another probable cause was

related to the amount of recreational reading done by students.

Those students who scored low on reading achievement tests did

less recreational reading than those students who scored higher.

The search of the literature revealed that involving parents in

a read

aloud program with their children was one of the best

ways to

improve reading achievement.

Interventions included a program of

daily oral reading in the classrooms by the teachers and recruiting

parents to enroll their children in the Woodbine Read Aloud Club.

Parents who enrolled their children in the Woodbine Read Aloud Club

agreed to read aloud to their children on a daily basis and to turn in

simple reading logs to the teachers each month.

As a reward for

their parents' read aloud efforts, the children received free

storybooks of their choice from the principal each month.

The objectives were to improve the students' reading

comprehension, word reading, and auditory vocabulary using the

Stanford Diagnostic Reading Test to measure any changes in reading

ability.

Tests results indicated a 38.5% increase in auditory

vocabulary, a 46.4% increase in reading comprehension and a 43.6%

increase in word reading for the subjects in the study.

These

results were supportive of the project's effectiveness.

iv

Table of Contents

Page

Committee Signature Page

i i

Permission Statement

i i i

Abstract

i v

List of Tables

v i i

Chapter

1.

Problem and Problem Background

1

Statement and Primary Evidence of the Problem

1

Overview of the Problem Setting

1

Description of Surrounding Community

4

2.

Problem Definition and Evidence

9

Problem Background

9

Evidence of Problem Discrepancy

9

Probable Causes of Problem

3 2

3.

Problem Situation and Context

4 3

Written Policies, Procedures, and Commentaries

4 3

Norms for Behavior, Values, Traditions

4 7

Formal and Informal Influences of Individuals and Groups.

.

48

External Circumstances

5 0

4.

Problem Conceptualization, Outcomes and the Solution

Strategy

5 3

Bibliographic Research and Review of Literature

5 3

Data Gathered Through Consulting With Others

7 5

Practicum Outcomes

7 7

Proposal Solution Components

7 9

5.

Action Plan and Chronology

8 6

Original Action Plan

8 6

Chronology of Implerrizntation Activities

8 7

t;

6. Results

100

Overview of Problem and Setting

100

Results of Implementation

100

Summary of Accomplishments

109

Discussion

116

7.

Discussion

120

Recommendations

120

Implications

121

Dissemination

122

References

125

Appendices

130

Appendix

A.

Classroom Teachers by Grade and Year

131

B.

Second Grade QCC Objectives in Language Arts

133

C.

Changes in Teacher Assignments

137

D.

WRAC Enrollment Form

138

E

WRAC Reading Log

139

F.

WRAC Newsletter

140

G

Newspaper Articles

14 2

H.

School Bell Award Newspaper Article

146

I.

WRAC Site Visitation Team Report

147

vi

List of Tables

Table

Page

1.

Camden County Population

4

2.

Population of the Incorporated and Unincorporated

Areas of Camden County

5

3.

School System Attendance

7

4.

Student Enrollment for Camden County Schools

8

5.

Second Grade Reading Percentile Scores 1988-1990

10

6.

Second Grade P.dading ITBS Scores Camden County Schools

.1 1

7.

Second Grade Students Scoring Below the 50th and 25th

Percentiles on the ITBS

13

8.

Students on the Free or Reduced Lunch Program

14

9.

Retained Students

16

10.

Classroom Teachers by Grade and Year

17

11.

Days Absent for Classroom Teachers

19

12.

Teacher Experience and Certification

21

13.

Photocopying 1989-1990

22

14.

Second Grade ITBS Scores for Targeted Groups

23

15.

Age in Months of Second Grade Students Entering

Kindergarten

24

16.

Second Grade Students Who Were Retained

25

17.

Lunch Status of Second Grade Students

26

vii

18.

Average Number of Days Absent for Second

Grade Students

27

19.

ITBS Reading Analysis for Second Grade Students

28

20.

Books Read by Second Grade Students

29

21.

Books Owned by Students

30

22.

SDRT - May 1991

31

23.

SORT Auditory Vocabuiary for 2nd Grade Students

102

24.

SDRT Reading Comprehension for 2nd Grade Students

103

25.

SDRT Word Reading for 2nd Grade Students

10 5

26.

1991-1992 Home Read Aloud Percentages

106

27.

1992-1993 Home Read Aloud Percentages

108

viii

Chapter 1

Problem and Problem Background

Statement and Primary Evidence QI thl Problem

Second grade students who attended Woodbine Elementary School

during 1988, 1989, and 1990, did not achieve average percentile

ranks on the reading portion of the Iowa Tests of Basis Skills that

were above the Georgia statewide average percentile ranks in

reading nor above the average percentile ranks for reading for other

elementary schools in Camden County.

Overview of tbg Problem Setting

Woodbine Elementary School is located in the City of Woodbine,

which is in the southeast coastal area of Georgia. Woodbine is 20

miles south of Brunswick, Georgia, and approximately 50 miles north

of Jacksonville, Florida.

Students attending Woodbine Elementary

School come from the northern half of Camden County.

Woodbine Elementary School was the subject of the study. The

school had a population of 440 students in grades K-5 and 65 faculty

and staff members.

The faculty and staff consisted of a principal,

an assistant principal, a media specialist, a school counselor (1/2

time), four kindergarten teachers, four first grade teachers, three

second grade teachers, three third grade teachers, three fourth grade

teachers, three fifth grade teachers, two Chapter 1 teachers,

a

1

special education teacher, a music teacher, a physical education

teacher, a speech teacher (1/3 time), an office manager, a secretary,

a media clerk, a resource paraprofessional, twenty classroom

paraprofessionals, seven food service personnel, and four

custodians.

The ethnic composition of the students and the adults who

worked with the children at Woodbine Elementary School was quite

diverse.

The ethnic balance of the students was almost equal.

Fifty-three percent of the children were Black and 47% were

Caucasian. The adults working at the school had an ethnic ratio of

33% Black to 67% Caucasian.

However, this percentage was

somewhat misleading, since only 24% of the classroom teachers

were Black, while 76% of them were Caucasian.

An increase in the percentage of Blacks working directly with the

children occurred with the paraprofessionals, since 40% of them

were Black, aid 60% were Caucasian.

Both administrators were

Caucasian, as were the media specialist, school counselor, and part-

time speech teacher.

The office manager was Caucasian and the

secretary was Black.

The media clerk and the resource center

paraprofessional were Caucasian.

Three of the food service workers

were Black, and four were Caucasian.

All four of the custodians

were Black.

The socioeconomic level of the families in the attendance area

2

i

served by Woodbine Elementary School was quite low.

Two hundred

sixty (59%) of the children attending the school qualified for the

free or reduced lunch program. Two hundred sixteen (49%) of the

children qualified for the free lunch program, and 44 (10%) qualified

for the reduced cost meals.

The high percentage of children

qualifying for the free or reduced lunch program was an indication of

the low socioeconomic status of many of tha families who sent their

children to the school.

The school qualified for two Chapter I teachers because of the

high percentage of students who were below grade level in reading

or mathematics in second through fifth grades.

One hundred thirty-

nine (47%) of the children in grades two through five

were served by

the Chapter 1 program. One hundred eighteen of the children

were

served in Chapter 1 reading, and eighty were served in Chapter 1

mathematics.

Some children qualified for both Chapter 1 reading

and mathematics.

In kindergarten and first grade, a Special Instructional

Assistance (SIA) program was initiated in the 1989-1990 school

year to serve those children who were identified as having

developmental deficiency delays which could result in problems

preventing them from maintaining a level of performance consistent

with expectations for their age range.

For the 1990-1991 school

year, 32% of the students in kindergarten and first grade were

3

2

identified as having developmental delays and qualified for the SIA

program.

Description of Surrounding Community

Camden County is located on the southeast coast of Georgia.

It is

south of Brunswick, Georgia, and it borders Florida on the north.

There are three incorporated cities within the county: Kingsland; St.

Marys; and Woodbine. Kingsland and St. Marys are situated in the

southern portion of the county, while Woodbine is located in the

northern section of the county.

According to U.S. Census data, the population of Camden County

changed considerably during the 1980's (Table 1)_

Table 1

Camden County Population from

U.S. Census

Year

Population

1960

9975

1970

11334

1980

13371

1990

30167

As the Camden County population changed, so did the incorporated

and unincorporated areas of the county.

The following table (Table

2) reflects the changes in the population in the incorporated cities

4

and in the unincorporated area of the county:

Table 2

Population at thig. Incorporated and Unincorporated Areas s21 Camden,

County

Area

1980

1990

Kingsland

2008

4699

St. Marys

3696

8187

Woodbine

910

1212

Unincorporated

6857

16069

The change in the population in Camden County during the 1980's

had been, for the most part, due to the installation of the Kings Bay

Naval Submarine Base.

In 1979, construction was started on the

future site of the Naval Base, and in 1981, Kings Bay Naval

Submarine Base was officially opened for military service

personnel.

Kings Bay Naval Submarine Base is located adjacent to St. Marys,

in the southern portion of Camden County.

The population growth in

Camden County centered around the Naval Base. The growth of St.

Marys and Kingsland were more affected by the advent of the Naval

Base than Woodbine.

However, there was considerable growth

throughout the unincorporated area of the county.

The Kings Bay Naval Submarine Base greatly affected the growth

5

of the Camden County School System.

Since the construction of the

Naval Base started, two elementary schools and two middle school

were constructed in the Kings land-St. Marys area.

Other schools already in service during this construction boom

included three elementary schools and a high school.

The cities of

Kings land, St. Marys and Woodbine each had an elementary school.

One middle school was located in St. Marys, and the other middle

school was in Kings land.

The high school was located in St. Marys.

The new Woodbine Elementary School was opened for occupancy

during the 1991-1992 school year.

On January 2, 1992, the students,

faculty and staff moved into the new facility.

The new building

replaced the old structure originally built in 1926.

The old school

building was given to the Camden County Commissioners for their

use.

For the 1991-1992 school year, student

enrollment increased

at Woodbine Elementary School.

Additional teachers,

paraprofessionals and other staff members were employed to meet

the educational needs of the additional students who were enrolled

when the school opened.

The school population in Camden County had experienced an

increase each year since the announcement that Camden County

would have a Naval Submarine Base at Kings Bay. The following

table (Table 3) reflects the changes in the average daily attendance

in Camden County since 1978-1979:

6

Table 3

School System Attendance

Year

Students

1978-1979

2680

1979-1980

2804

1980-1981

2978

1981-1982

3078

1982-1983

3203

1983-1984

3262

1984-1985

3313

1985-1986

3723

1986-1987

3984

1987-1988

4288

1988-1989

4708

1989-1990

5222

1990-1991

5686

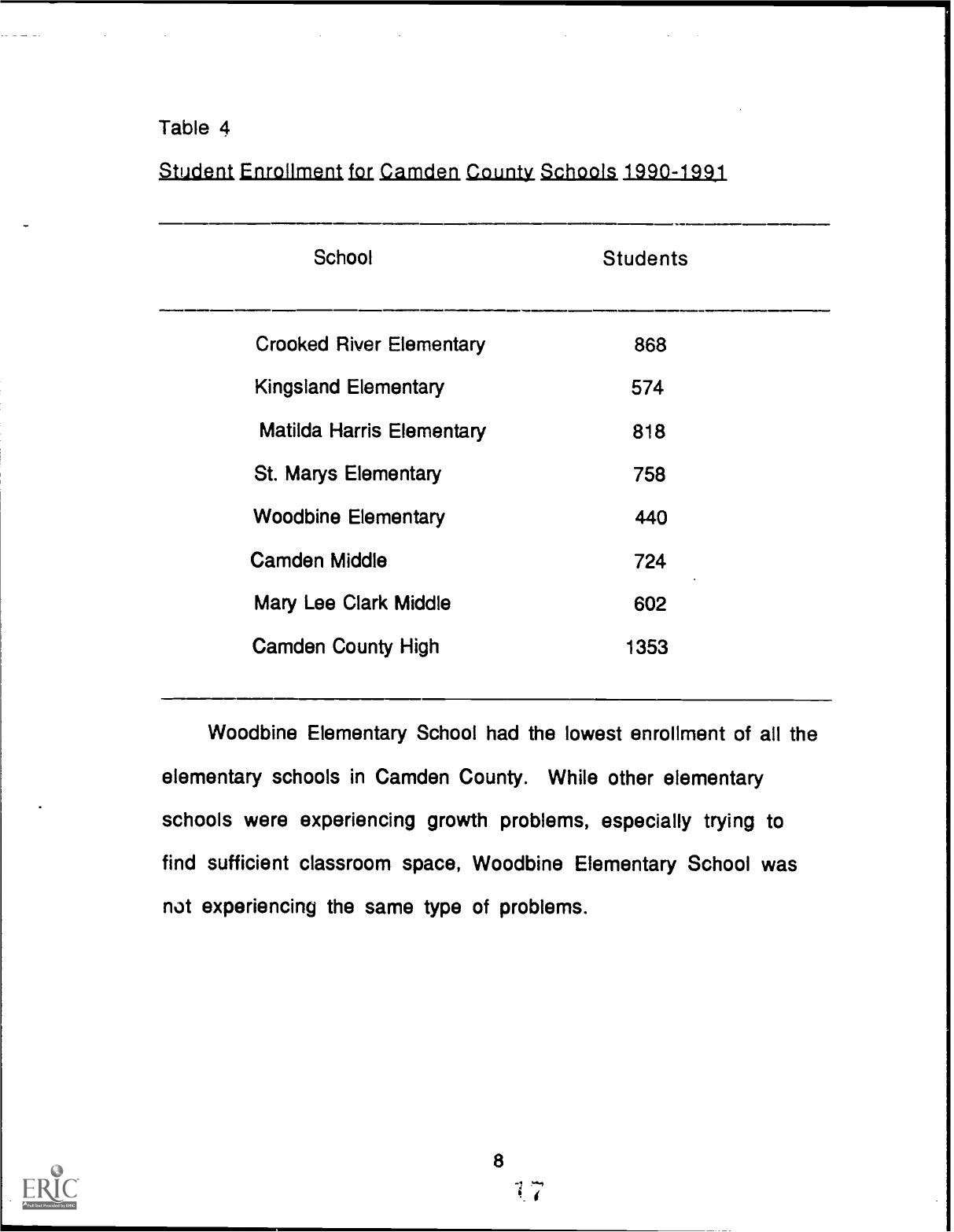

The total school enrollment for the 1990-1991 school year for

Camden County for the fifth month of school was 6,137.

The

percentage of attendance was 93, so the average daily attendance

was 5,686.

The following table reflects the attendance for each of

the schools in Camden County for the 1990-1991 school year:

7

Table 4

Student Enrollment fsu Camden County Schools 1990-1991

School

Students

Crooked River Elementary

868

Kingsland Elementary

574

Matilda Harris Elementary

818

St. Marys Elementary

758

Woodbine Elementary

440

Camden Middle

724

Mary Lee Clark Middle

602

Camden County High

1353

Woodbine Elementary School had the lowest enrollment of all the

elementary schools in Camden County.

While other elementary

schools were experiencing growth problems, especially trying to

find sufficient classroom space, Woodbine Elementary School was

not experiencing the same type of problems.

8

Chapter 2

Problem Definition and Evidence

Problem Background

In 1988, 1989, and 1990, second grade students who attended

Woodbine Elementary School received lower than anticipated scores

on the reading portion of the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills (ITBS).

The

reading scores for the second grade students at Woodbine

Elementary School during these three years showed that students

achieved lower average percentile ranks than the Georgia statewide

average percentile ranks and the national percentile ranks.

In

addition, second grade students at Woodbine Elementary School had

average reading percentile scores that were lower than any other

elementary school in the county.

Evidence Qf Problem Discrepancy,

The Georgia Quality Basic Education Act (QBE) required norm-

referenced tests to be administrated to students in grades two and

four.

Results of these tests were used in planning instructional

improvement activities and in various program evaluation efforts.

The 1988-1990 average percentile scores on the reading portion

of the ITBS for second grade students are given in the following

9

table (Table 5) for Woodbine Elementary School (WES), Camden

County and Georgia:

Table 5

Second Grade Reading Percentile Scores 1988-1990

Date

Grade

Average Reading Percentile Scores

WES

County State

3/88

2

50

60 62

3/89

2 42

57

6 3

3/90

2

37

61

6 6

From 1988 through 1990, the average reading percentile scores

of second grade students at Woodbine Elementary School decreased.

This indicated that there was a need for reading improvement in

second grade at the school, and a need to determine the causes of the

decline in reading scores.

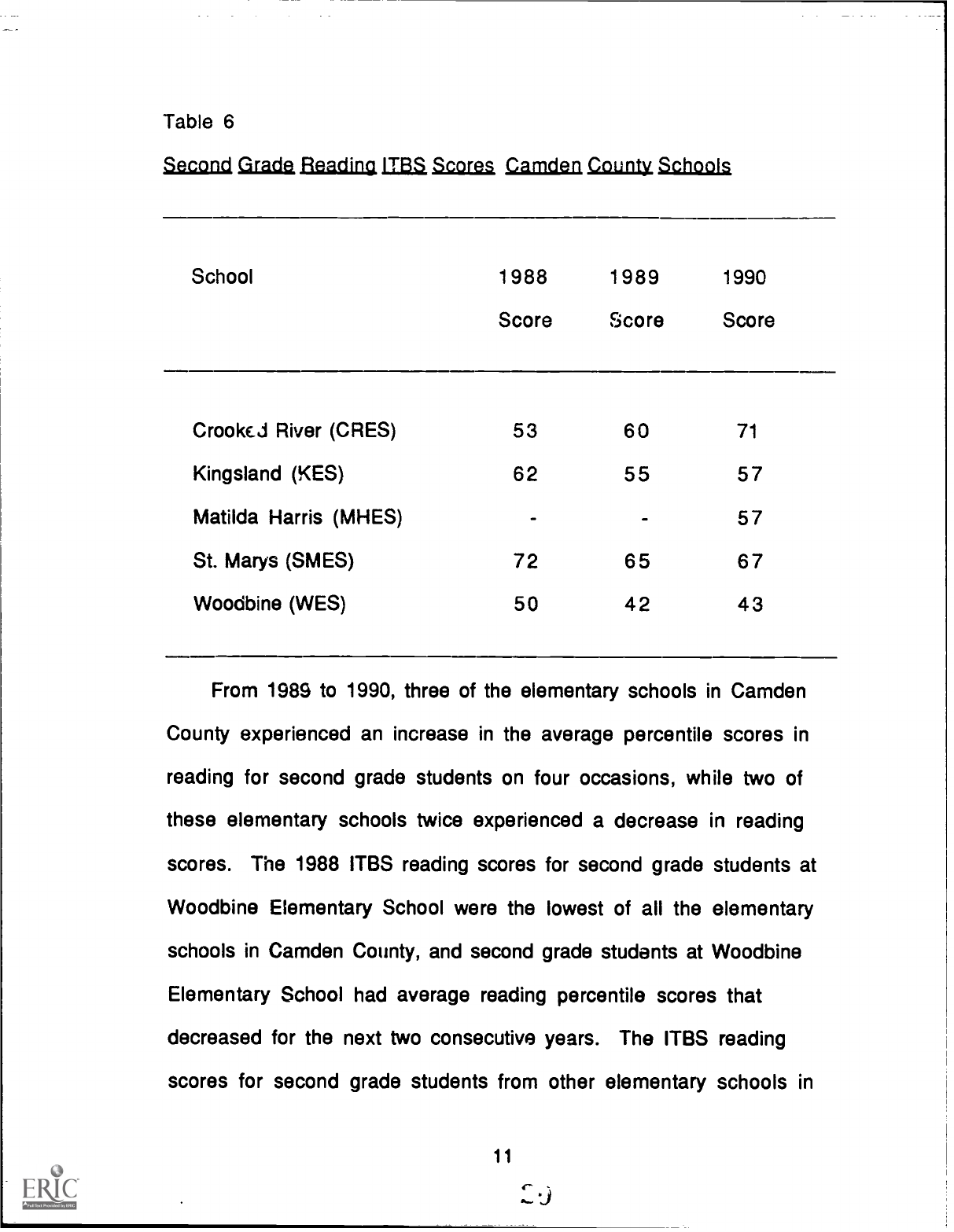

The 1988 through 1990 ITBS reading percentile scores for second

grade students from each of the five elementary schools in the

Camden County School System were examined and compared. The

following table (Table 6) gives the average ITBS reading percentile

scores for second grade students in each of the Camden County

elementary schools:

10

Table 6

Second Grade fleadina ITBS Scores Camden County Schools

School 1988 1989

1990

Score Score Score

Crooki River (CRES)

53 60

71

Kings land (KES)

6 2 55

57

Matilda Harris (MHES)

57

St. Marys (SMES) 72

65

67

Woodbine (WES)

50 42

43

From 1989 to 1990, three of the elementary schools in Camden

County experienced an increase in the average percentile scores in

reading for second grade students on four occasions, while two of

these elementary schools twice experienced a decrease in reading

scores. The 1988 ITBS reading scores for second grade students at

Woodbine Elementary School were the lowest of all the elementary

schools in Camden County, and second grade students at Woodbine

Elementary School had average reading percentile scores that

decreased for the next two consecutive years.

The ITBS reading

scores for second grade students from other elementary schools in

11

,..

Camden County during this period of time did not reflect the same

decrease in test scores.

There are not any 1988 and 1989 ITBS

reading scores reported for Matilda Harris Elementary School

because it did not receive students until the 1989

- 1990 school

year.

Matilda Harris Elementary School officially opened in August,

1989.

Students attending Matilda Harris Elementary School came

from the former attendance zones of Woodbine Elementary School

and Kings land Elementary School.

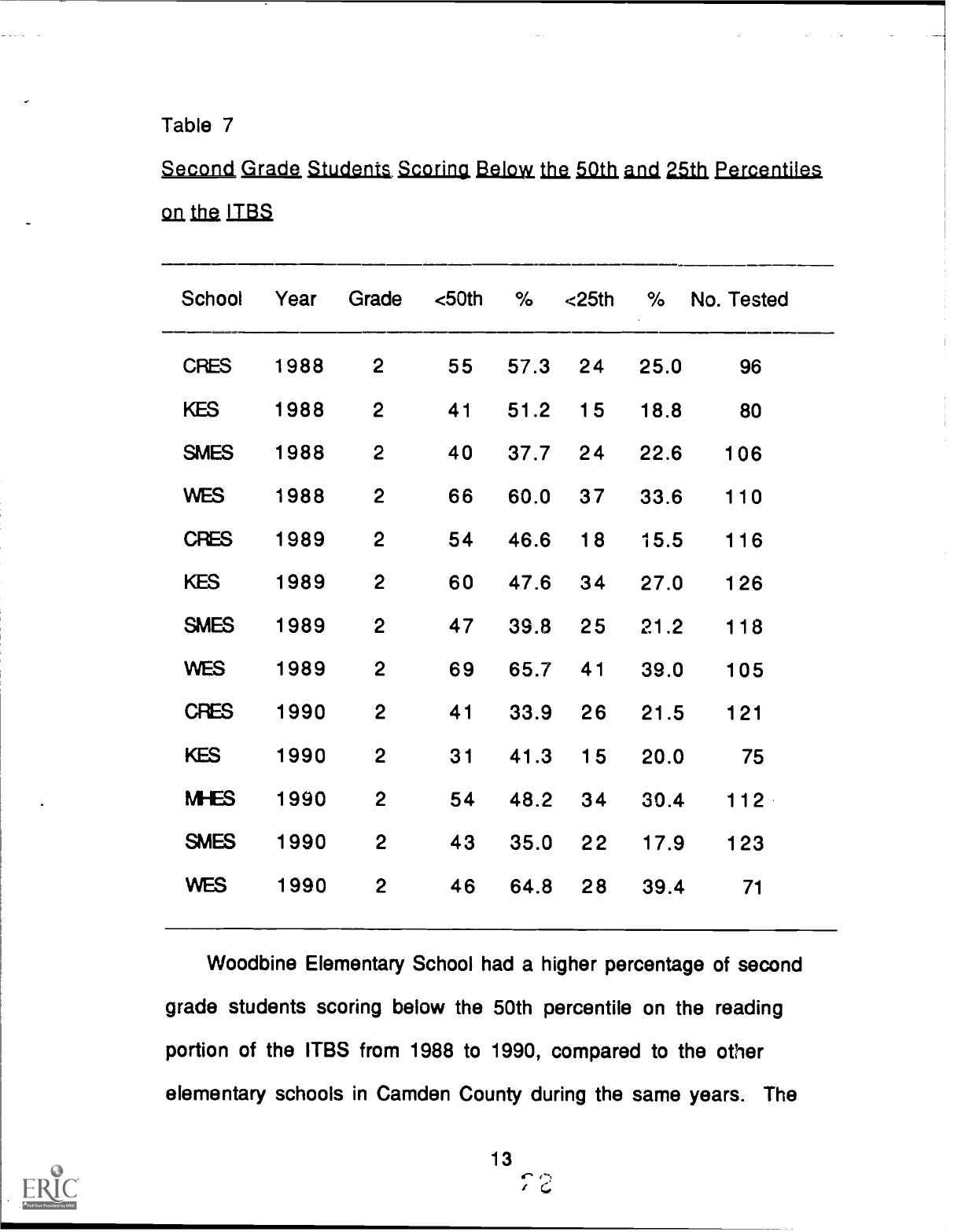

The ITBS test data were more conclusive when the number of

students scoring below a certain percentile was determined and that

number was reported as a percentage. The 50th and the 25th

percentiles were chosen as markers to distinguish levels of

achievement.

Above the 50th percentile was considered acceptable

reading achievement, and below the 25th percentile was considered

very low reading achievement for second grade students.

All

students who scored below the 25th percentile in reading would also

be reflected in the numbers of those students scoring below the

50th percentile.

The following table (Table 7) shows the number of

second grade students who scored below the 50th percentile and

below the 25th percentile on the reading portion of the ITBS from

1989-1990, for each of the elementary schools in Camden County.

It

also gives the number of students tested and the percent of students

scoring below the 50th and 25th percentiles:

12

'.1

Table 7

Second Grade Students. Scoring Beim t

50th and 25th Percentiles

g_ng ITBS

School Year Grade <50th % <25th

% No. Tested

ORES 1988 2

55 57.3 24

25.0 96

KES

1988

2 41

51.2 15

18.8

80

SMES 1988

2 40

37.7

24 22.6

106

WES 1988

2 66

60.0 37 33.6

110

CRES

1989

2

54 46.6

18 15.5

116

KES 1989 2

60 47.6

34 27.0

126

SMES 1989

2

47 39.8

25 21.2

118

WES 1989 2

69

65.7 41

39.0 105

ORES

1990

2

41

33.9 26

21.5 121

KES

1990 2

31

41.3 15

20.0

75

M-IES

1990 2

54 48.2 34

30.4 112

SMES

1990

2 43 35.0

22

17.9

123

WES

1990

2

46 64.8

28 39.4

71

Woodbine Elementary School had a higher percentage of second

grade students scoring below the 50th percentile on the reading

portion of the ITBS from 1988 to 1990, compared to the other

elementary schools in Camden County during the same years. The

percentage of second grade students scoring below the 25th

percentile on the reading portion of the ITBS was 18.7% higher

during the three year period than the average percentile for each of

the other elementary schools in Camden County.

The percentage of

second grade students scoring below the 25th percentile on reading

indicated that Woodbine Elementary School had a proportionally high

number of lower achieving reading students in second grade.

The Camden County School System participated in the free or

reduced price lunch program.

Table 8 shows the percentage of

students on free or reduced price lunches:

Table 8

Students oil the Free a Reduced Lunch Program

School

% Free

% Reduced

% Free & Reduced

ORES

11

15

26

KES

25 10

35

NI-ES 21

13

34

SMES

28

-7

35

WES 47

12

59

CMS 27

11

38

MLCMS

13

8

21

CCHS

11

5

16

COUNTY

20

10

30

14

Woodbine Elementary School had the highest percentage of

students on the free or reduced price lunch program in the Camden

County School System. The percentage of students at Woodbine

Elementary School receiving free lunches was over twice the

average percentage of students receiving free lunches at the other

elementary schools in Camden County.

This high percentage of

students receiving free lunches at Woodbine Elementary School was

an indicator of the low socioeconomic conditions of the families

from which many of the children come. These low socioeconomic

conditions of the children were reflected in their reading

achievements.

Children from low socioeconomic conditions in the

Woodbine area did not perform as well on standardized reading

achievement tests as did children who came from high

socioeconomic conditions.

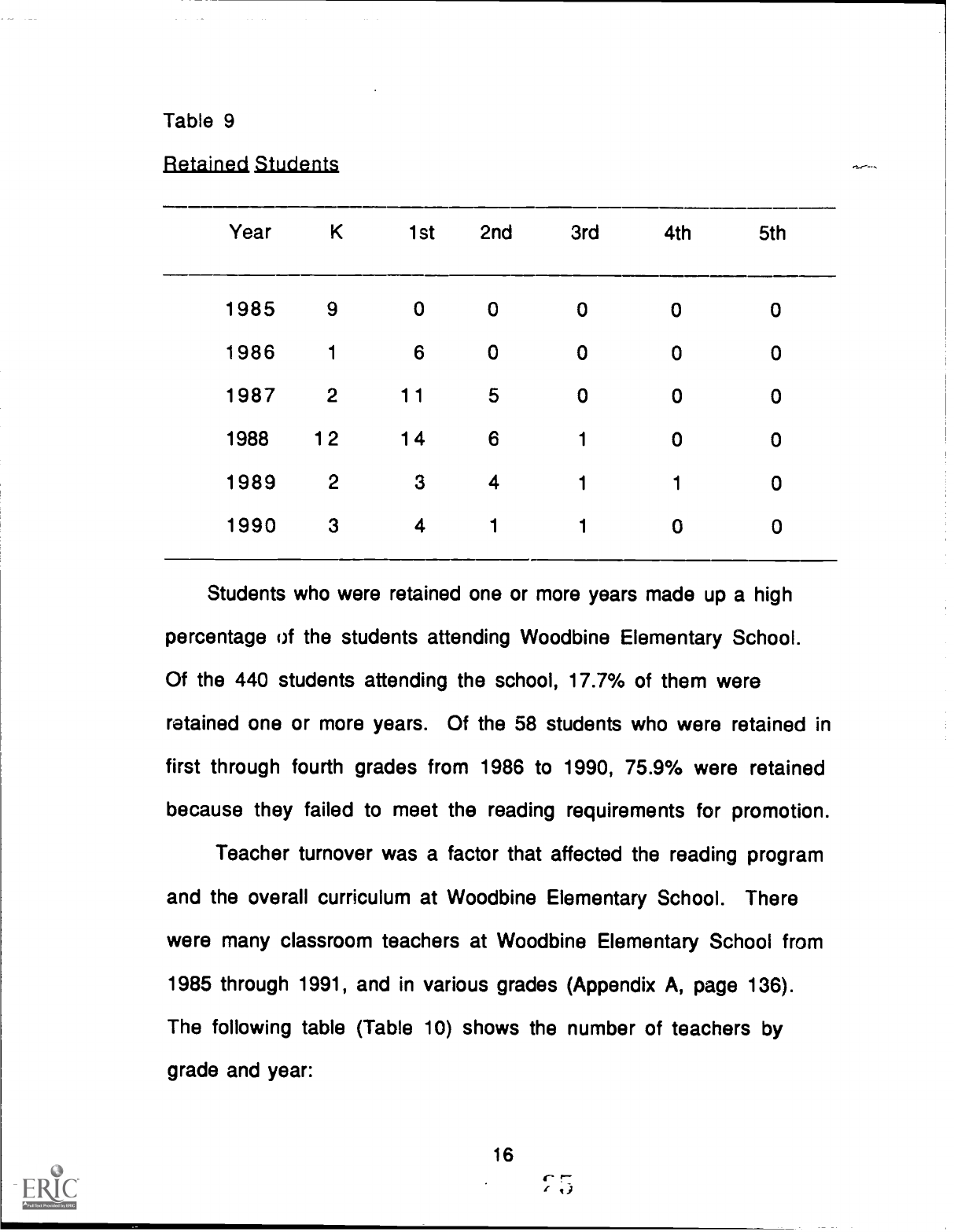

Each year at Woodbine Elementary School, students who did not

meet promotion criteria were retained at grade level.

The Camden

County Board of Education established promotion criteria for the

school system.

The promotion criteria for students in the

elementary schools included passing the required major subjects

with grar;es of 70 and above and meeting the reading requirements.

Reading requirements were established for each grade.

The

following table (Table 9) gives the year and grade retained for

students at Woodbine Elementary School:

15

Table 9

Retained Students

Year K

1st

2nd

3rd

4th 5th

1985 9

0 0

0

0 0

1986 1

6 0

0

0

0

1987 2 11 5

0 0

0

1988

12 14

6

1

0

0

1989 2

3

4

1 1

0

1990

3

4

1

1 0

0

Students who were retained one or more years made up a high

percentage of the students attending Woodbine Elementary School.

Of the 440 students attending the school, 17.7% of them were

retained one or more years.

Of the 58 students who were retained in

first through fourth grades from 1986 to 1990, 75.9% were retained

because they failed to meet the reading requirements for promotion.

Teacher turnover was a factor that affected the reading program

and the overall curriculum at Woodbine Elementary School.

There

were many classroom teachers at Woodbine Elementary School from

1985 through 1991, and in various grades (Appendix A, page 136).

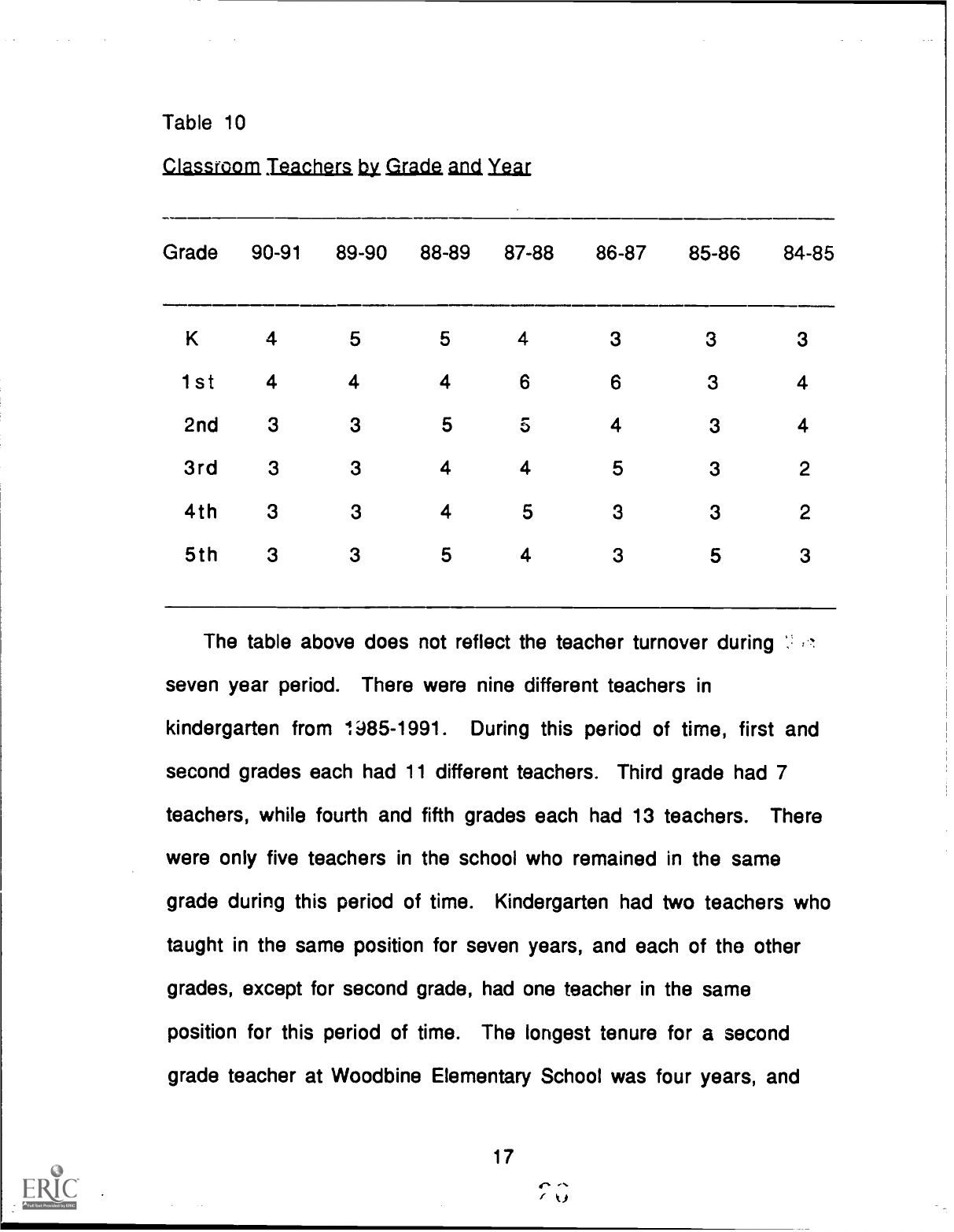

The following table (Table 10) shows the number of teachers by

grade and year:

16

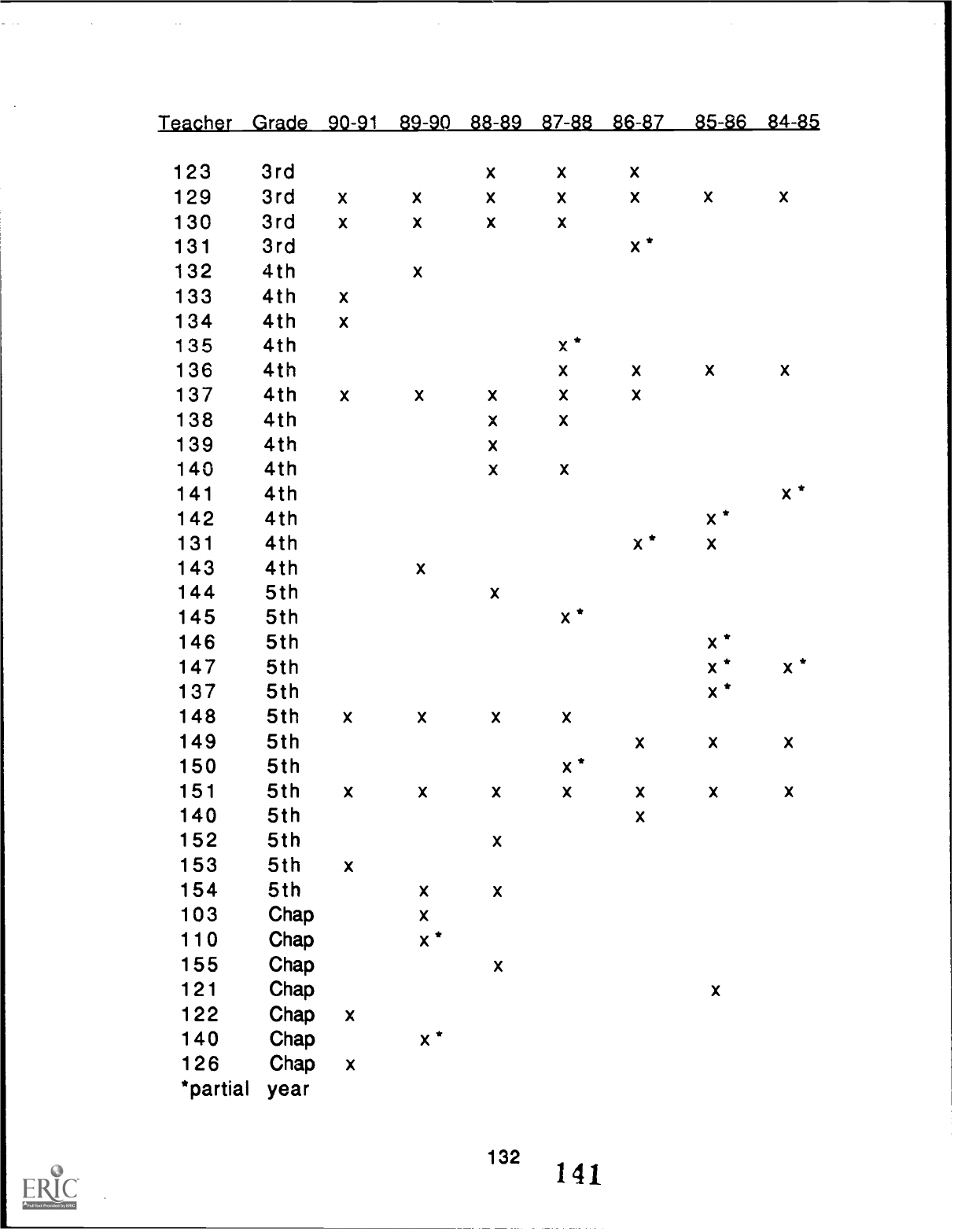

Table 10

Classroom Teachers la Grade and

Year

Grade 90-91

89-90 88-89 87-88

86-87 85-86 84-85

K 4 5 5 4

3 3

3

1st 4

4

4

6 6

3

4

2nd

3

3

5 5

4 3

4

3rd

3 3

4 4

5 3

2

4th

3 3

4 5

3

3

2

5th

3 3 5 4

3 5

3

The table above does not reflect the teacher turnover during

seven year period.

There were nine different teachers in

kindergarten from 1985-1991.

During this period of time, first and

second grades each had 11 different teachers.

Third grade had 7

teachers, while fourth and fifth grades each had 13 teachers.

There

were only five teachers in the school who remained in the same

grade during this period of time.

Kindergarten had two teachers who

taught in the same position for seven years, and each of the other

grades, except for second grade, had one teacher in the same

position for this period of time.

The longest tenure for a second

grade teacher at Woodbine Elementary School was four years, and

17

the average tenure in second grade was two and a-half years.

This data implied that whatever the reasons for teacher turnover,

Woodbine Elementary School had experienced a considerable turnover

at each grade level except for third grade during the seven years.

Personnel records indicated that the majority of teacher turnover

was related to the mobility of the instructional staff. The number of

teachers employed in second grade during this time and the brevity

of tenure indicated that consistency in the curriculum may have been

lacking.

In the Camden County School System, teachers earned 12 days of

sick leave each year.

Three of the 12 sick leave days could be used

as personal days upon advanced approval by the administration.

Sick

days and/or personal days that were not used could be accumulated

by the teacher. A maximum of 45 days of sick leave could be

accumulated by each teacher.

Accumulated sick leave up to 45 days

could be transferred by a teacher to another school in Camden County

or to another public school system in Georgia.

Sick leave earned

above 45 days not used by a teacher was lost.

The number of days

teachers were absent from classroom instruction at Woodbine

Elementary School was obtained from attendance records. The

following table (Table 11) gives the number of days absent for the

classroom teachers at Woodbine Elementary School from 1988

through 1990:

18

Table 11

Days Absent fa

Classroom Teachers

Teacher

Grade

1987-1988

1988-1989 1989-1990

101 K

0

102

K

3

11

12.5

104

K

8

16

20.5

106

K

8 10

13.5

107 K

3.5

108

K

9

8

7

110

1st

9

0

111

1st

11.5

9.5

112

1st

0

114

1st 1

6

116

1st

9

117

1st

3

8.5 1

118

1st

7

119

1st

7

7

15

101

2nd

3

MD

120

2nd

14.5

122

2nd

40

11.5

12.5

123

2nd

13.5

125

2nd

6

115

2nd

15

12

118

2nd

4

7

126

2nd

6 17.5

19

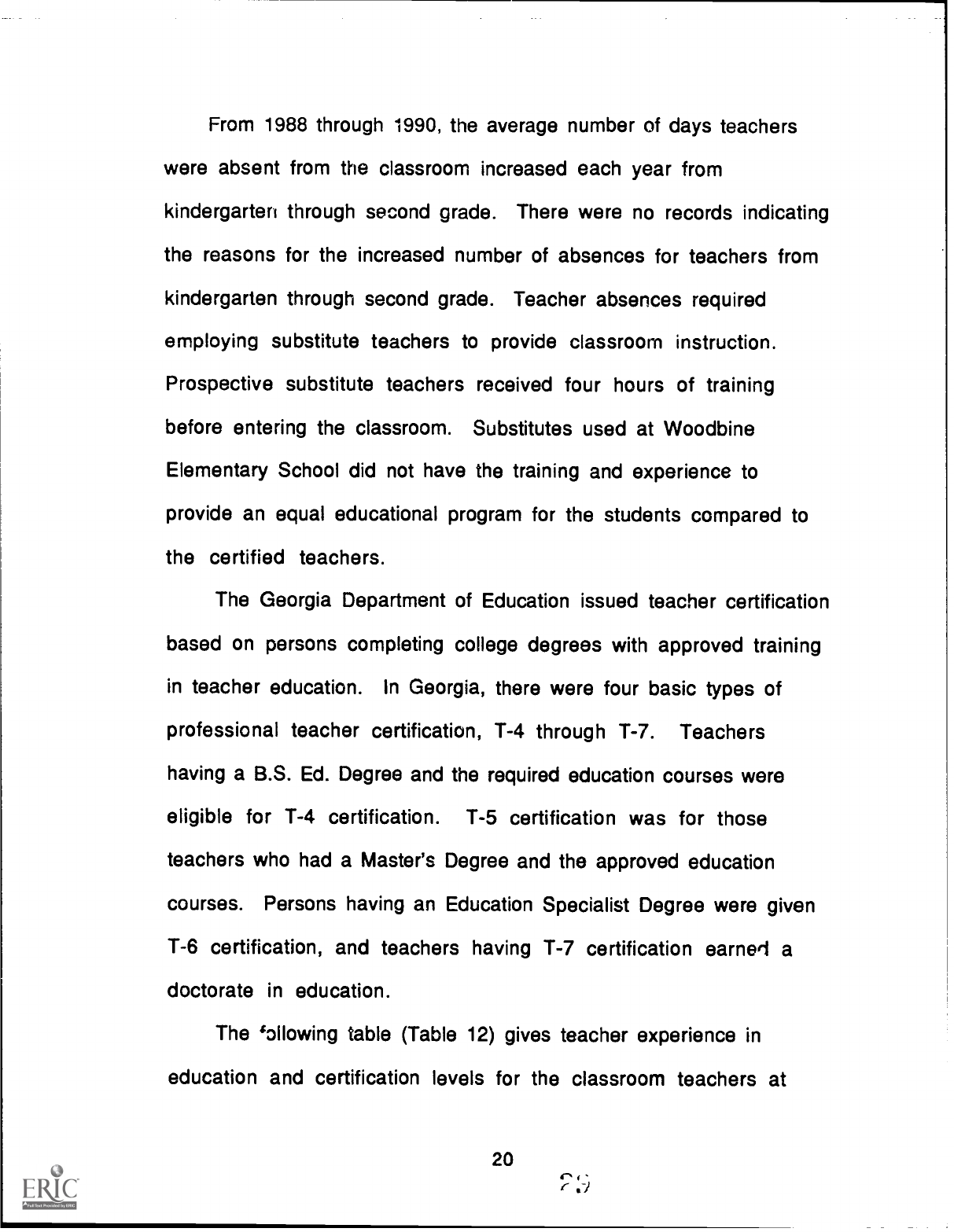

From 1988 through 1990, the average number of days teachers

were absent from the classroom increased each year from

kindergarten through second grade.

There were no records indicating

the reasons for the increased number of absences for teachers from

kindergarten through second grade.

Teacher absences required

employing substitute teachers to provide classroom instruction.

Prospective substitute teachers received four hours of training

before entering the classroom.

Substitutes used at Woodbine

Elementary School did not have the training and experience to

provide an equal educational program for the students compared to

the certified teachers.

The Georgia Department of Education issued teacher certification

based on persons completing college degrees with approved training

in teacher education.

In Georgia, there were four basic types of

professional teacher certification, T-4 through T-7.

Teachers

having a B.S. Ed. Degree and the required education courses were

eligible for T-4 certification.

T-5 certification was for those

teachers who had a Master's Degree and the approved education

courses.

Persons having an Education Specialist Degree were given

T-6 certification, and teachers having T-7 certification earned a

doctorate in education.

The $311owing table (Table 12) gives teacher experience in

education and certification levels for the classroom teachers at

20

Woodbine Elementary School for the 1990-1991 school year:

Table 12

Teacher Experience and Certification

Teacher

Grade Years Experience

Certification

103 K

2

T-4

104 K

18

T-4

107 K

1

T-4

108 K 11

T-4

109 1st

9

T-4

111

1st 17

T-6

117

1st 26

T-5

119

1st

9 T-4

123

2nd

16

T-4

106 2nd

6

T-4

118

2nd

21

T-5

128

3rd

12

T-4

129

3rd 35

T-4

130

3rd

8

T-4

133

3rd

15

T-5

134

4th

9

T-4

137

4th

15

T-4

148

5th 19

T-5

151

5th 18

T-5

153

5th 11

T-5

Although teacher certification and experience were not

necessarily part of the reading problem, apathy can be a problem.

Of

21

the 13 teachers in kindergarten through fifth grade who had T-4

certification, 7 of them were working toward Master's Degrees.

The

other six teachers who had T-4 certification each indicated that

they had no intention of ever going back to college for an advanced

degree.

Another factor considered in relationship to the reading problem

was the amount of worksheets teachers gave to students.

Table 13

gives the number of photocopied sheets for each teacher iri K-2

during 1989-1990:

Table 13

Photocopying 1989-1990

Teacher

Grade Sheets

Students

Copies/Student

Per/Day

102 K

15106

18

839 4.7

104

K

6592 18

366 2.0

106 K

8724 18

485 2.7

107 K

11675

17

687

3.8

108

K

5807 19

306

1.7

111

1st

7676 21

365 2.0

117

1st 17720

21

844

4.7

118

1st

14049

21

669

3.7

119

1st 13183

21

628

3.5

122

2nd 15065

27

558 3.1

123 2nd

19111

27

708 3.9

126

2nd

16694

21

795

4.4

22

The number of worksheets students received at the school was a

problem not only in reading but in other areas of the curriculum, too.

When students were completing worksheets, they were losing

teacher instructional time.

Each second grade teacher averaged

using approximately 17,000 photocopied sheets during the school

year.

The number of worksheets given to each second grade student

averaged 3.8 per day. The average number of worksheets used in the

classroom increased from kindergarten through second grade.

In order to make comparisons in reading achievement of second

grade students who had been enrolled at Woodbine Elementary School

from 1988 through 1990, two groups of ten second grade students

were chosen each year.

One group included those who scored lower

than acceptable on the reading portion of the ITBS. The second group

had scored the highest on the same test. The following table gives

the average reading percentile scores on the ITBS for the two groups

of second grade students from 1988 through 1990:

Table 14

Second Grade, ITBS Reading Scores la Targeted Groups.

Group A

Group B

Average ITBS Scores

Year

Average ITBS Scores

Year

18.5

1988

85.8

1988

7.9

1989

80.2

1989

8.8

1990

79.8

1990

23

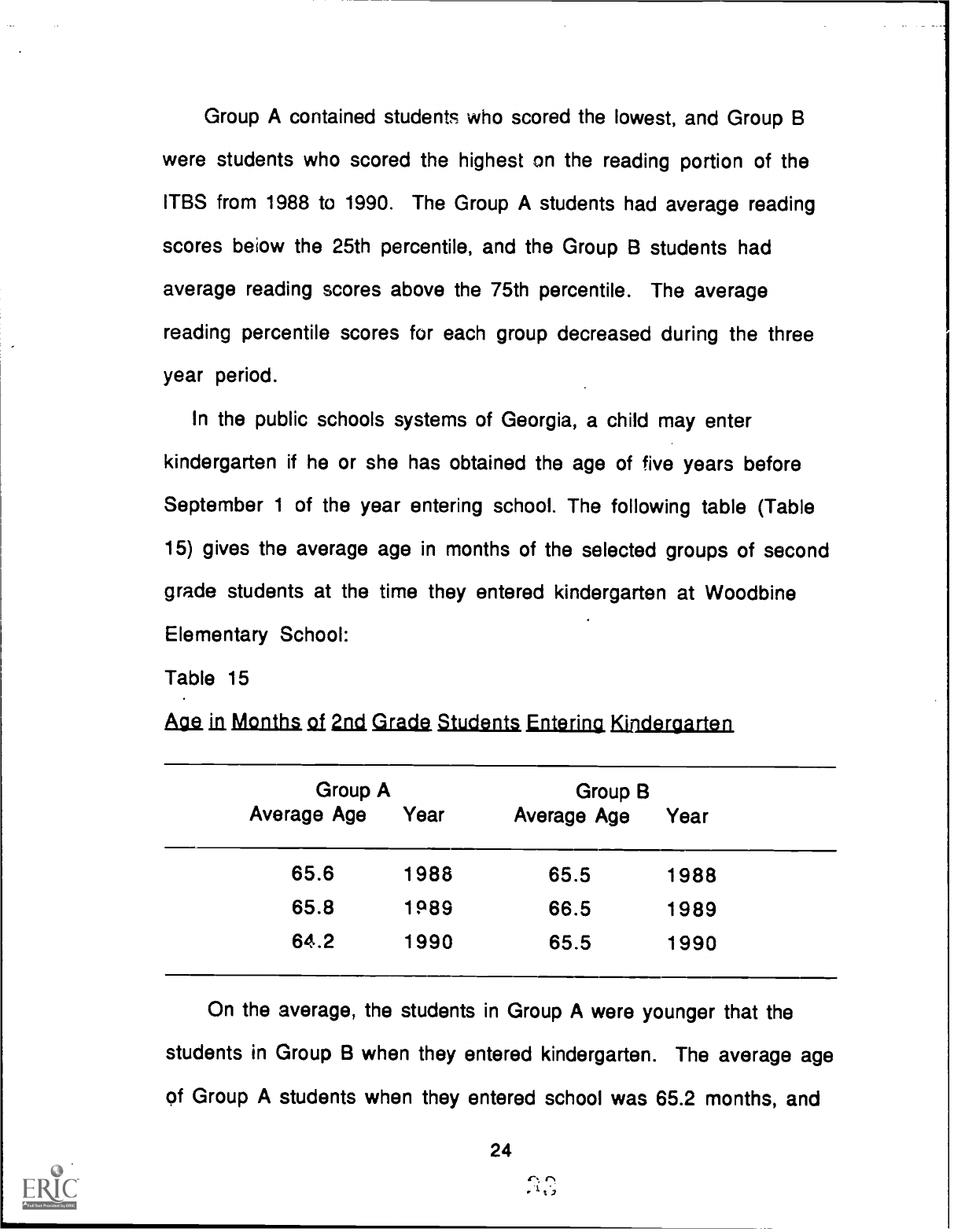

Group A contained students who scored the lowest, and Group B

were students who scored the highest on the reading portion of the

ITBS from 1988 to 1990. The Group A students had average reading

scores beiow the 25th percentile, and the Group B students had

average reading scores above the 75th percentile.

The average

reading percentile scores for each group decreased during the three

year period.

In the public schools systems of Georgia, a child may enter

kindergarten if he or she has obtained the age of five years before

September 1

of the year entering school. The following table (Table

15) gives the average age in months of the selected groups of second

grade students at the time they entered kindergarten at Woodbine

Elementary School:

Table 15

Age is Months Qf and

Grade Students Entering Kindergarten

Group A

Group B

Average Age

Year

Average Age

Year

65.6 1988

65.5 1988

65.8

1P89

66.5

1989

64.2

1990

65.5

1990

On the average, the students in Group A were younger that the

students in Group B when they entered kindergarten. The average age

of Group A students when they entered school was 65.2 months, and

24

the average age of the Group B students was 65.8 months. Those

students who were experiencing developmental delays when they

entered kindergarten tended to be younger that those students who

were more developmentally mature when they entered school.

The second grade student target population included a number of

students who were retained one or more years.

To be retained at

grade level, a student must have failed two or more major subjects

or failed the meet the reading requirements for the grade level.

The

major subjects were reading, English, science, social studies,

mathematics, and physical education.

Table 16 gives the retained

students and the grade retained:

Table 16

Second Grade Students Who Were Retained

Student Grade Retained Group

Student Grade Retained Group

0188

K

A 1089

K and 2nd A

0288 K

A

0690

2nd

A

0988

2nd

A

0890

1st A

1088

2nd

A 1188

1st

B

0289

1st

A

1589

2nd

B

0589 1st

A

1290

2nd B

0989 1st

A

Ten percent of the Group B students were retained during the

25

Ir 1, 7

first three grades compared to 33% for Group A students.

Seventy-

five

percent of the students retained in first and second grades

were retained because they did not meet reading promotion

requirements. The remaining 25% of the students were retained

because they failed two or more major subjects.

The lunch status of the second grade target population students

are listed in Table 17.

The number of students receiving free or

reduced lunches are given for each group.

Table 17

Lunch Status of Second Grade

Students.

Group A

Group B

Free

Reduced

Free

Reduced

17

5

5

4

Group A had the lowest reading scores and the highest percentage

of students qualifying for free lunches.

Group B had the highest

reading scores and the lowest number of students receiving free

lunches.

Group A had the highest percentage of students qualifying

for reduced price lunches compared to Group B students who

received reduced price lunches.

Seventy percent of the Group B

students did not qualify for either the free or reduced price lunches,

while only 27% of the Group A students did not qualify for the free

or reduced price lunch program.

It indicated that students who

26

-1. I)

scored lower in reading tended to come from family conditions of

lower socioeconomic status than those students who scored at the

highest levels in reading.

According to the policies of the Camden County School System, an

elementary student who has more than twenty days of unexcused

absences may not receive credit for a grade level.

A students who is

absent from school for any portion of a school day must provide the

appropriate school official with a written excuse from a parent,

guardian or physician.

The excuse must provide a reason for the

absence.

The average number of days absent from kindergarten through

second grade for the target groups of second grade students is given

in the following table:

Table 18

Average Number gi Days Absent la Second Grade Students

Group A

Year

Days Absent

Group B

Year

Days Absent

1988

8.6

1988

8.0

1989

7.4

1989

7.3

1990

4.6

1990

6.3

The average number of days absent for each group

was seven

days.

This indicated that the students had good attendance

no

27

matter what their academic standing.

It also indicated that because

of good student attendance, teachers had an opportunity to provide

maximum amounts of instructional time for all students.

The reading portion of the ITBS was analyzed to determine

specific areas of weakness by examining individual student

performance profiles.

The reading portion of the ITBS was

subdivided into three categories: facts; inferences and

generalizations.

Each of these categories was analyzed for each of

the target students.

The following table (Table 19) gives the

reading analysis for the target population of second grade students.

Table 19

Average FIBS Reading Scores Analysis fa Second, Grade Students

Year

NPR

Facts

Pupil % Correct

Inferences Generalizations

1988

18.5

50.8 36.4

51

National % Correct

67

69

62

1989

7.7

34.3

30.4

38

National % Correct

67

69

62

1990

8.8 40.7

32.5

45

National % Correct

70 71

79

This table indicated that second grade students at Woodbine

28

37.

Elementary School performed below national averages in three

subcategories on the reading portion of the ITBS.

It implied that

teachers must look more closely at their course content to insure

that they are teaching the concepts that will enable students to

master these three categories.

During the 1990-1991 school year at Woodbine Elementary

School, students in grades two through five kept library reading logs

for six months.

The following table (Table 20) shows the average

number of library books read by second grade students during this

time according to their ITBS reading percentile scores:

Table 20

Books Read by Second Grade Students

ITBS PRT

No. Students

Books Read

>75th

6

102

50th-75th

6

55

25th-49th 12

35

<25th

41

21

Sixty-five second grade students participated in

a recreational

reading program during the 1990-1991 school year.

Students

scoring above the 75th percentile on the reading portion of the ITBS

read an average of 102 library books. Those student who scored

between the 50th and the 75th percentile read an average of 55

29

3'8

books.

Students who scored below the 25th percentile read

an

average of 21 books.

This implied that students who scored higher in reading

on the

ITBS did much more recreational reading than those students who

scored lower in reading on the ITBS. The higher the ITBS reading

score, the greater the average number of books read for pleasure.

Students who could read, did read. Those students who had weak

reading skills did not read as much as students who had better

reading

skills.

During the 1988 - 1989 school year, teachers in kindergarten and

first grade questioned students individually to determine the number

of books each child personally owned.

The following table (Table 21)

gives the number of books owned by students:

Table 21

Books Owned by. Students

Grade

No. Students

<5

5-10

>10

K

68

29

19 20

1st

78

34

25

19

Teachers reported that students who owned the most books

were

those children who came from homes of higher socioeconomic

status.

These children made better grades and scored higher on

standardized tests than children who did not own books or who

owned few books. These children, on the average, performed poorly

in academic subjects.

This indicated that students who did not have

books of their own did not have as many opportunities to enrich their

lives through books.

The children questioned by the teachers would

be second graders during the implementation of the project.

In May, 1991, the Stanford Diagnostic Reading Test (SDRT) was

administered to the first and second grade students at Woodbine

Elementary School.

The following table gives the results of three of

the subtests of the SDRT:

Table 22

SDRT,

- May. 1991

Group

Subtest

N

M%ile Rank

1st Grade

Auditory Vocabulary

6 7

31.3

2nd Grade

Auditory Vocabulary

6 5

32.7

1st Grade

Word Reading

6 7

37.8

2nd Grade

Word Reading

6 5

29.6

1st Grade

Reading Comprehension

6 7

33.5

2nd Grade

Reading Comprehension

6 5

27.4

The Stanford Diagnostic Reading Test is a group administered

instrument that has been used as a screening device for children

experiencing reading difficulties.

The lowest level (Red) was

designed for first and second graders, and it was administered in

May, 1991, to both these grades at Woodbine Elementary School prior

to the start of the project.

Reading and reading related subtests of

the SDRT revealed a pattern of below average achievc;nent.

These

initial test results were compared to second grade SDRT scores

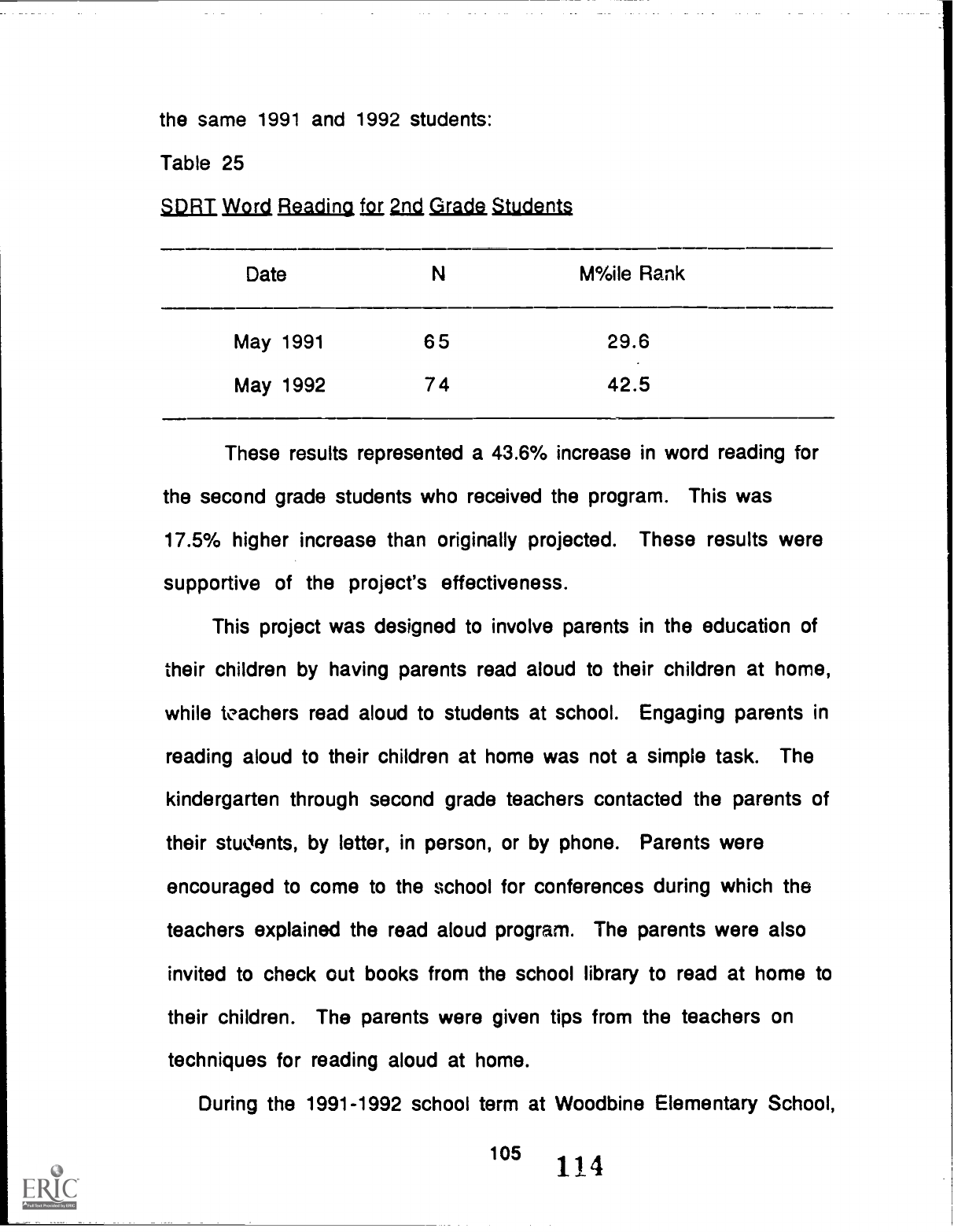

administered in May, 1992, as reported in Tables 23, 24, and 25.

Probable Causes githg Problem

From 1988-1990, the average reading percentile scores on the

ITBS for second grade students at Woodbine Elementary School were

below the Camden County average and the Georgia average. During

this time, Woodbine Elementary School also had the highest number

of children in the county who qualified for the free and reduced

lunch program.

The combination of these two factors indicated that

many of the children at Woodbine Elementary School were

disadvantaged and considered at-risk students.

Maeroff (1991) reported that there are many shortcomings

associated with norm-referenced tests.

It was speed and low cost

that enabled the norm-referenced test, with its multiple-choice

responses, to conquer the world of education and hold it in thrall.

Maeroff advocated alternative assessment for students.

However, he

recognized that students who score poorly on the much-maligned

norm-referenced tests with their multiple choice responses are not

necessarily going to perform better on the alternatives.

The second grade students at Woodbine Elementary School were

given the ITBS during the 1988-1990 school years.

ITBS testing was

conducted usually during late April or early May.

After the 1989-

1990 school year, the ITBS was no longer given to second grade

students.

Amspaugh (1990) stated that some standardized tests contained

test questions that were written in such a way that even the

teachers were not sure which were the right answers.

She said that

taking standardized tests took a lot of time, time that children

could have spent learning to read real books and enjoying practical

applications of mathematics and writing.

Means and Knapp (1991) stated that children who score lower

than their peers on standardized tests of reading tend to come from

poor backgrounds and/or from cultural or linguistic minorities.

They

also said that classroom studies document the fact that

disadvantaged students receive less exposure to print outside of

school and family support for education than do their more

advantaged peers.

Frymier (1990) reported that children who are retained in grade

were much more likely to drop out of schoo' than children who were

promoted, and their general achievement in the years ahead was

lower than that of students who were promoted.

The second part of

his statement was supported, in part, by the percentage of retained

students enrolled in second through fifth grades at Woodbine

Elementary School (Table 9) who were retained two or more times.

Ten percent of these retained students were retained for the second

or third time.

Of the students enrolled at the school for the 1990-1991 school

year, 17.7% of them were retained one or more times.

Of the

students retained during 1989 and 1990, 25% of these students were

second graders.

Smith and Shepard (1987) estimated the overall

rate of retention in the United States as being 15% to 19%. The

overall retention rate at Woodbine Elementary was consistent with

the national rates.

Table 10 shows the classroom teachers by grade at Woodbine

Elementary School from 1984 through 1990.

It gives the total

number of teachers per grade for each year.

There were many

teachers at the school during these years (Appendix A, page 131).

During this period of time, some teachers were moved frequently,

others taught in the same grade

,

and some teachers stayed at the

school for just a few years.

The turnover of teachers in

kindergarten through second grade was examined closely, and one of

the probable causes for lower reading achievement of second grade

students may have been due to the frequency of teacher turnover in

second grade.

From 1984 through 1990, at Woodbine Elementary School there

were 9 kindergarten teachers, 11 first grade teachers and 11 second

grade teachers.

The average tenure for kindergarten teachers was

2.9 years.

First grade teachers had an average tenure of 2.6 years.

Second grade teachers had the lowest tenure.

They averaged 2.4

years in second grade.

The lower tenure of second grade teachers

suggests that this may have been a probable cause for the low

reading achievement of second grade students.

The reading program was affected by frequent teacher turnover

because teachers new to the school had to become acquainted with

the basal reading program used at the school.

After the initial

adoption of a new basal reading series, very little staff development

was provided for new teachers on the basal reading program. The

lack of continuous staff development in the basal reading series for

new teachers suggests a probable cause of low reading achievement

of second grade students.

Teacher turnover will continue at Woodbine Elementary School as

more students move into the school attendance zone and as the

attendance zone for the school changes.

For the 1991-1992 school

year, approximately 60 additional students attended Woodbine

Elementary School.

The students who lived in the attendance zone of Woodbine

Elementary School moved into a new facility during the 1991-1992

school year.

The new school accommodated more students, and

additional teachers were added to the faculty for the 1991-1992

school year.

The number of days teachers were absent from class had a

negative effect on instruction.

Substitute teachers at the school

had little education beyond high school.

Everyday a teacher was out

of the class, the students lost valuable instructional time.

Second

grade teachers had the highest absenteeism of all the teachers in

the school, which suggests this as a probable cause for the low

reading achievement of second grade students.

For the 1990-1991 school year, a new leave policy was approved

by the Board of Education that had some effect on the number of days

teachers were absent from school.

Before the 1990-1991 school

year, teachers were allowed to accumulate up to 45 days of sick

leave.

Since this policy passed, teachers have been able to

accumulate an unlimited number of sick days.

This new leave policy

may have a positive effect on reducing teacher absenteeism.

It may

also maintain teacher instructional time.

Another factor of the second grade reading problem may have

been the number of worksheets that teachers gave to students each

year.

Table 13 gives the number of sheets photocopied for each

teacher in kindergarten through second grade for the 1989-1990

school year.

Although not all of the photocopied sheets were

necessarily student worksheets, the majority of them were.

For

these first three grades, the number of worksheets per student

per

day increased as the student moved up through the grades.

The reading curriculum was affected by the number of

worksheets completed.

When students were doing worksheets in

reading, they were losing reading instructional time.

A child cannot

learn to read by doing worksheets. One goal was to increase student

recreational and academic reading.

Smith (1992) expressed that children learn from the company

they keep, and there are two groups of people that ensure that

children learn to read.

The first group includes the people who read

to children: parents, siblings, friends, and teachers.

The second

group is composed of the authors of the books that children love to

read.

The authors help children to recognize written words, and the

more written words that children are able to understand, the easier

it

is for them to learn new words.

It was reported by Smith (1992) that four year-olds learn about

20 new words a day. When they enter school, they know around

10,000 words. When they leave school, they know at least 50,000

words, and perhaps more, depending on how much reading they do.

He also advocated reading to children. He said that reading to

children served many purposes.

It put children in the company of

people who read.

It showed them what can be done with reading, and

it sparked their interest in the consequences of reading.

The effectiveness of teachers in the classrooms was difficult to

determine.

Teacher evaluation forms were examined to determine

areas for improvement of individual teachers.

The problem with this

procedure was that on the Georgia Teacher Evaluation Instrument

(GTEI) used by administrators to evaluate classroom performance,

it

was easy for teachers to receive satisfactory ratings.

In addition,

the GTEI had only been in existence since 1988, and evaluation forms

prior to that time were nonexistent.

According to a paper by Uphoff and Gilmore (1985), when children

enter school before they were developmentally ready to cope with it,

their chances for failure increased dramatically.

The research

reviewed by Uphoff and Gilmore showed that children who were less

than five years three months of age when enrolled in kindergarten,

when compared to children entering kindergarten who were older

than five years three months, showed that older children were much

more likely to score in the above average range on standardized

achievement tests, and the younger children in a grade were far

more likely to have failed at least

one grade than older children.

The second grade students in Group A and Group B had similar

average ages upon entering kindergarten (Table 15). The slight

difference in the average ages of the two groups did not appear to

have an adverse impact on the problem of low reading achievement

of the second grade students.

The number of children who were retained in the two grades

varied considerably.

Ten children from Group A were retained one or

more times, while only three students from Group B were retained.

The majority of these students who were retained failed to meet the

reading requirements for promotion.

Woodbine Elementary School students who come from lower

socioeconomic conditions made up the largest percentage of

students who scored below the 50th and 25th percentiles on the

reading portion of the ITBS. One of the probable causes for low

reading achievement of second grade students was the low

socioeconomic conditions of the families from which many of the

lower achieving students came.

The number of days absent for the selected groups of students is

given in Table 18.

The average number of days absent for each group

was almost equal.

Attendance did not appear

be a probable cause

of the low reading achievement of second grade students.

Although heterogeneous grouping of students in the classroom

had occurred at Woodbine Elementary School from 1988 through

1990, students were grouped for reading according to their ability

Ability grouping in reading did not allow low reading achieving

students to experience reading modeling by their peers who were

better readers.

The Camden County Schools adopted a different basal reading

series for the 1991-1992 school year.

During the 1986-1987

school year, a reading policy requirement was added to the Board of

Education's policies for the Camden County Schools.

For promotion

of students, all reading policy requirements must have been met.

Each grade was assigned a minimum level to complete in the basal

reading series.

Another probable cause for low reading achievement by second

grade students was related to the number of books they read.

Students who did not read well did not read as many books as

children who were better readers.

Students who performed poorly

on reading tests tended to do little recreational reading compared to

students who were better readers.

Another probable cause for low reading achievement was related

to the number of books students personally owned. Over 43% of the

students in kindergarten and first grade owned fewer than five

books.

Students who owned books had greater opportunities to

improve their reading skills than children who did not own any

books.

It also implied that someone in the families of these

students were concerned enough about reading to have purchased

books for their children.

The probable causes of low reading achievement of second grade

students at Woodbine Elementary School were difficult to ascertain.

But the most prevalent causes were related to the low

socioeconomic status of many of the families from which the

majority of the children came.

Families of low socioeconomic

status were unable to provide books for their children; therefore,

these children did not have as many opportunities for improving

their reading skills as did children who came from families who

provided books for their children.

Other probable causes were

related to the placement of students in reading groups.

Children

from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were, many times, grouped

together and, therefore, did not have opportunities to associate with

students who were better readers.

Cuban (1989) reported that parents of children from poor

families and certain cultural backgrounds failed to prepare their

children for school and provided lithe support for them in school.

Parents of many of the children from Woodbine Elementary School

were not involved in the education of their sons and daughters, and

this could have been one of the causes of low reading achievement.

Another probable cause of low reading achievement by second

grade students was related to the reading instructional program

provided by teachers from kindergarten through second grade.

Teachers used much of the instructional time by having students

complete worksheets.

Worksheets were not necessarily the

problem, because there was a place for worksheets.

According to

second grade lesson plans, the completion of worksheets occupied

approximately 50% of reading instructional time.

The second grade

teachers said that their use of worksheets was related to the basal

reading series.

Interviews with second grade teachers implied that

students should do more reading.

The reading portion of the ITBS was analyzed for individual

students by examining performance profiles.

Reading was

subdivided on the ITBS into three categories: facts; interferences;

and generalizations.

The results of the analysis, along with teacher

interviews, indicated that second grade students did not do enough

reading.

4S1

Chapter 3

Problem Situation and Context

Written Policies, Procedures, and Commentaries

On July 1, 1986,

a comprehensive approach to improving

education in Georgia, the Quality Basic Education Act (QBE), became

effective.

The overriding purpose of QBE was to insure that:

each student was provided ample opportunity to develop

competencies necessary for lifelong learning, as well as the

competencies needed to maintain good physical and mental

health, to participate actively in governing process and

community activities, to protect the environment and conserve

public and private resources, and to be an effective worker and

responsible citizen. (p. 5).

QBE addressed a statewide basic curriculum framework, and it

was a helping influence in that each of the public schools in Georgia

was required to adhere to the Reform Act.

To insure the uniform

adherence to QBE by public schools in Georgia, the Georgia Board of

Education (GBOE) supervised a comprehensive evaluation of each

local school system and each public school on a periodic basis. One

component of the comprehensive evaluation system was the Public

School Standards program. The application

Standards assessed a

43

52

system's or a school's compliance with state law and GBOE policy

and rules.

The Public School Standards were a helping influence because the

Standards were indicators of legal adherence to the QBE Act, and

schools must function within state laws.

In the event that a school

did not meet a certain standard, the evaluation process allowed the

school to make adjustments to its program to meet the standard.

The Quality Core Curriculum (QCC) was part of QBE. The QCC

provided students opportunities to experience a continuum of

activities with appropriate emphasis in each instructional

area: fine

arts, foreign language, health, language arts, mathematics, physical

education, science, social studies, and vocational education.

The

QCC for language arts, which included reading, was

a helping

influence because all Georgia's public school children could expect

to be taught the same core content regardless of their geographic

location or the economic conditions of the school district.

The QCC

objectives in language arts for second grade were given to all the

second grade teachers (Appendix B, page 133).

One part of Standards that was a hindering influence

was the

standard dealing with curriculum guides.

The standard applying to

curriculum guides stated: "A locally approved curriculum guide

existed for each subject and/or course offered for which the system

earned FTE funding" (p. 66).

The system approved the state

44

53

curriculum guides to meet this standard.

The state curriculum guide

in language arts was published in 1984, and it has not been revised

since then.

The language arts curriculum guide that was used to

meet Standards was published before the QBE act was passed in

1986.

Another written policy that affected the reading program at

Woodbine Elementary School was the standard relating to remedial

education.

This standard stated: "A remedial education program for

eligible children in grades two through five and in grades nine

through twelve was established and implemented" (p. 83).

The

standard about remedial education was viewed as being both a

helping influence and a constraining influence in the reading

program

at Woodbine Elementary School.

Remedial education was available to second grade students

who, during the month of March of their experience in first grade,

scored below the 25th percentile on the reading portion of the

Georgia Criterion Referenced Tests.

A constraining factor was that

eligibility for remedial education in reading was determined by

student performance on a single test.

It was a helping influence in

identifying children who needed remediation in reading,. but it also

identified children for remediation who did not necessarily need it.

Anothur written policy that had an effect on the second grade

reading program was the Chapter 1 program.

Chapter 1 of the

34

Educational Consolidation and Improvement Act (ECIA) was a

federally funded program which was designed to meet the identified

needs of the educationally deprived children in eligible Chapter 1

schools.

Woodbine Elementary School was an eligible Chapter 1

school because of the high percentage of children who were below

grade level in reading and mathematics in second through fifth

grades.

Since Woodbine Elementary School was a Chapter 1 school,

an educational program in reading had to be designed to meet the

special needs of the children who qualified for Chapter 1

services.

This was a helping influence, in that the identified children in

reading received special help from a teacher who had been

designated to teach Chapter 1

reading.

The classes were small, with

a maximum of 12 students in each class, and the Chapter 1 teacher

was provided additional funds to purchase supplementary materials

for instruction.

The students stayed with the Chapter 1 teacher for

all components of language arts.

It was a hindering influence

because the children were homogeneously grouped.

A limiting factor was the county reading policy requirement.

This policy stated that for a child to be promoted to the next grade,

a minimum level in the HBJ Bookmark Reading Program must have

been met.

This was the policy that caused most of the children who

were retained each year, from first to fifth grades, to lepeat their

grade or attend summer school.

It was a hindering influence because

46

teachers set their expectations for their students based on this

policy.

The teachers used the minimum reading requirements as

their maximum expectations for the students in their classrooms.

Once a child completed the minimum reading requirements, that

child had met the teacher's expectations, and then the teacher

concentrated on helping other children who had not met the minimum

reading requirements.

Norms fsu Behavior, Values, Traditions

One tradition at Woodbine Elementary School that affected the

reading program was the grouping of students for reading.

Teachers

in all grades at the school had traditionally grouped students

according to their reading ability.

The homogeneous grouping of

students for reading started with the students who had been

identified as being qualified for Chapter 1 reading and/or the

Remedial Education Program (REP). Most of the students who

qualified for REP, which was state funded, also qualified for Chapter

1

reading, which was federally funded.

In second grade, one of the teachers was designated as the REP

teacher for the year.

This designation changed from year to year so

that, as tradition went, each teacher would have an opportunity to

work with the lowest group of readers.

During reading, students

who were REP/Chapter 1 either stayed with the REP teacher or

moved to the Chapter 1 teacher for the language arts instruction.

This movement of REP/Chapter 1

students created the formation of

two classes of language arts which had a reduced number of

students in each of them compared to the other second grade

classes.

The average number of students in

REP/Chapter 1 class

was 12 or 13.

The regular classes of second grade students usually

averaged over 26 students each.

Students in the other second grade

classes were grouped according to ability, with each teacher having

two or three groups.

Each teacher usually had high, average, and low

groups for reading.

Another factor regarding REP students was the number who were

eligible for REP reading.

In the 1989-1990 school year, there were

43 students who qualified for RE,' reading.

Not all of them returned

to Woodbine Elementary School for the 1990-1991 school year, but

the majority of them did.

The number of REP students exceeded the

number that could be placed with the REP teacher or Chapter 1

teacher during the block for language arts.

Therefore, the other

second grade teachers were required to provide reading remediation

for the REP students in their language arts classes.

Formal and.

Informal InfluenQaa of Individuals and Groups

One hindering factor in the improvement of the reading program

in second grade at Woodbine Elementary School was the

pressure

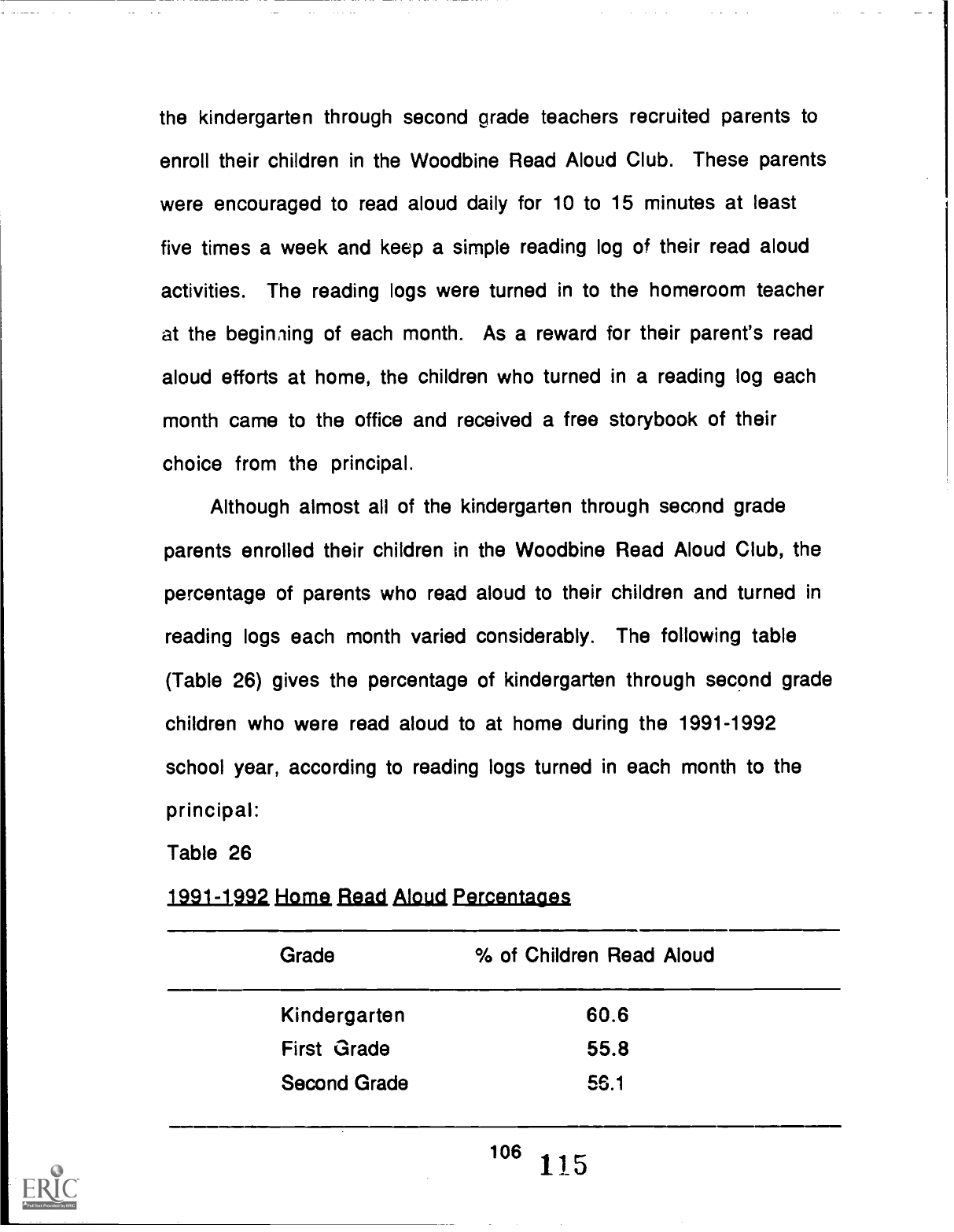

teachers felt to improve reading and mathematics scores of their