Alexander Shalom (021162004)

Jeanne LoCicero (024052000)

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

OF NEW JERSEY FOUNDATION

570 Broad Street, 11th Floor

P.O. Box 32159

Newark, NJ 07102

(973) 854-1714

ashalom@aclu-nj.org

Attorneys for Charles Kratovil

CHARLES KRATOVIL

Plaintiff,

v.

CITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK, and

ANTHONY A. CAPUTO, in his

capacity as Director of Police.

SUPERIOR COURT OF

NEW JERSEY

LAW DIVISION

MIDDLESEX COUNTY

Docket No.:

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF’S

ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE

WITH TEMPORARY RESTRAINTS

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................................................................... iv

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ....................................................................... 1

FACTUAL ALLEGATIONS ........................................................................... 4

A. New Jersey’s version of Daniel’s Law .......................................... 4

B. The Daniel’s Law warning to Plaintiff .......................................... 6

ARGUMENT ..................................................................................................15

I. Plaintiff is likely to succeed on the merits of his free speech

and free press claim. ....................................................................16

A. The Daily Mail principle forbids the state from

punishing the publication of lawfully obtained

information, absent a need of the highest order. .................16

1. First Amendment prohibitions against prior

restraint.....................................................................16

2. The State Constitution’s broader reach. ....................17

3. The Daily Mail principle. ..........................................19

a) Cox Broad. Corp. v. Cohn. .............................19

b) Neb. Press Ass’n v. Stuart. .............................21

c) Okla. Publ’g Co. v. Dist. Ct. ..........................22

d) Landmark Commc’ns, Inc. v. Virginia. ............22

e) Smith v. Daily Mail Publ’g Co. .......................23

f) The Fla. Star v. B.J.F. .....................................24

g) Bartnicki v. Vopper. ........................................27

h) The New Jersey Supreme Court’s

recognition of the Daily Mail Principle. ..........29

iii

B. The Daily Mail principle applies to Daniel’s Law

under the New Jersey Constitution. ....................................30

1. In some instances, homes addresses are

matters of public concern. .........................................31

2. The Daily Mail principle applies whether

information is obtained through a public record

or through traditional reporting techniques. ..............33

3. Daniel’s Law is not narrowly tailored to achieve

its laudable goals. .....................................................34

4. Although Daniel’s Law serves a laudable

interest, it does not amount to a need of the

highest order. ............................................................36

II. Plaintiff easily meets the remaining standards for granting

temporary restraints. ....................................................................37

A. Absent interim relief, plaintiff will continue to suffer

harm because the only sufficient remedy for his

ongoing injury is an injunction. ..........................................37

B. The balance of the equities, including the public

interest, favors the issuance of an immediate

injunction ......................................................................... .38

C. The restraint does not alter the status quo ante. ..................39

CONCLUSION ...............................................................................................40

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

44 Liquormart, Inc. v. Rhode Island, 517 U.S. 484 (1996) ..............................16

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58 (1963) ........................................17

Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514 (2001) ................................................ passim

Brennan v. Bergen Cnty. Prosecutor’s Off., 233 N.J. 330 (2018) ..................... 9

Burnett v. Cnty of Bergen, 198 N.J. 408 (2009) ............................................... 9

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940) ................................................16

Cox Broad. Corp. v. Cohn, 420 U.S. 469 (1975) ........................... 19, 20, 26, 36

Crowe v. De Gioia, 90 N.J. 126 (1982) ..................................................... 15, 37

Davis v. N.J. Dep’t of L. & Pub. Safety, Div. of State Police,

327 N.J. Super. 59 (Law. Div. 1999) ......................................................37

Donrey Media Grp. v. Ikeda, 959 F. Supp. 1280 (D. Haw. 1996) ...................35

Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347 (1976) ...............................................................37

G.D. v. Kenny, 205 N.J. 275 (2011)............................................... 29, 30, 36, 39

Hamilton Amusement Ctr. v. Verniero, 156 N.J. 254 (1998) ...........................17

Landmark Commc’ns, Inc. v. Virginia, 435 U.S. 829 (1978) ............... 22, 23, 37

Maressa v. N.J. Monthly, 89 N.J. 176, 192 cert. denied,

459 U.S. 907 (1982) ..............................................................................18

N.J. Coal. Against War in the Middle East v. J.M.B. Realty Corp.,

138 N.J. 326 (1994) ...............................................................................18

N.Y. Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971) ................... 16, 17, 36–37

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931) ............................................. 16, 17, 36

Nebraska Press Ass’n v. Stuart, 427 U.S. 539 (1976) ............................... 21, 37

Oklahoma Publ’g Co. v. Dist. Ct., 430 U.S. 308 (1977) ............................ 22, 36

Org. for a Better Austin v. Keefe, 402 U.S. 415 (1971) ...................................17

v

Sisler v. Gannett Co., 104 N.J. 256 (1986) ................................................ 18, 19

Smith v. Daily Mail Publ’g Co., 443 U.S. 97 (1979) ................................ passim

State v. Schmid, 84 N.J. 535 (1980), app. dism. sub nom. Princeton

Univ. v. Schmid, 455 U.S. 100 (1982) ...................................................18

The Florida Star v. B.J.F., 491 U.S. 524 (1989) ....................................... passim

Waste Mgmt. of N.J., Inc. v. Union Cnty. Utils. Auth., 399

N.J. Super. 508 (App. Div. 2008) ..........................................................38

Yakus v. United States, 321 U.S. 414 (1944) ...................................................38

Constitutions

N.J. Const. art. I, ¶ 6 .......................................................................................17

U.S. Const. amend. I .......................................................................................16

U.S. Const. amend. XIV, § 1 ...........................................................................16

Statutes

N.J.S.A. 2A:84A-21 ........................................................................................18

N.J.S.A. 2C:20-31.1(c) .................................................................................... 5

N.J.S.A. 2C:20-31.1(d) .................................................................................... 6

N.J.S.A. 47:1B-3 ....................................................................................... 33, 34

N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(a)(1) ................................................................................ 5

N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(a)(2) ................................................................................ 5

N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(c) ..................................................................................... 5

N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(e) ..................................................................................... 5

N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(f) ..................................................................................... 5

Other Authorities

Abbie VanSickle, Justice Thomas Failed to Report Real Estate Deal With

Texas Billionaire, N.Y. Times (Apr. 13, 2023),

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/13/us/politics/clarence-thomas-

harlan-crow-real-estate.html ..................................................................31

vi

Mikenzie Frost, Residency questions continue for BPD’s Acting Commissioner

Worley, Fox45News (June 13, 2023),

https://foxbaltimore.com/news/local/residency-questions-continue-for-

bpds-acting-commissioner-worley .........................................................31

N.J. Dep’t of Community Affairs, Daniel’s Law,

https://danielslaw.nj.gov/Default.aspx?ReturnUrl=%2f

(last visited July

6, 2023) .................................................................................................. 5

Stephen Koranda, Kansas Rep. Steve Watkins Charged With Felonies Over

Voter Registration At UPS Store, NPR, (July 14, 2020),

https://www.npr.org/2020/07/14/891242761/kansas-rep-steve-watkins-

charged-with-felonies-over-voter-registration-at-ups-st .........................32

1

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

The New Jersey Supreme Court has adopted a principle articulated at

least seven times by the United States Supreme Court: if the media lawfully

obtains truthful information about a matter of public significance, then despite

an existing statute, “state officials may not constitutionally punish publication

of that information, absent a need of the highest order[.]” The state laws

challenged in the U.S. Supreme Court cases each had important statutory

purposes: they were meant to protect the names of rape victims or juvenile

offenders, classified national security information, wiretapped conversations,

or information about judicial discipline. Yet, in what became known as “the

Daily Mail

1

principle,” the Supreme Court ruled that free speech and free press

principles demand a strict scrutiny test and that each of these statutes failed to

show a “need of the highest order.”

New Jersey’s version of Daniel’s Law—which allows for redaction of

certain personal information such as home addresses from public records—is

certainly another important statute, designed to protect public servants such as

judges and law enforcement from the potential of bodily harm from criminal

elements. But as applied to journalists who would report on an issue related to

1

Smith v. Daily Mail Publ’g Co., 443 U.S. 97 (1979).

2

the actual residency of a protected official, the statute similarly punishes

publication of lawfully obtained, truthful information about an important

public issue and fails to show a need of the highest order.

In this Order to Show Cause, Plaintiff Charles Kratovil, the editor of a

local online publication called New Brunswick Today, seeks to have this Court

simply apply the State Constitution to the facts in this matter, which are on all

fours with more than one of these seven U.S. Supreme Court cases,

recognized by the New Jersey Supreme Court.

Mr. Kratovil learned in the course of his reporting that Anthony A.

Caputo, New Brunswick’s Director of Police and member of the City’s

Parking Authority, resides in and registered to vote in a municipality that is

more than a two-hour drive from his employer. He obtained the information

legally through an Open Public Records Act (“OPRA”) request to the Cape

May Board of Elections.

While attempting to raise questions about this issue with the City

Council at a public meeting, he mentioned the street name (but not the house

number) of Director Caputo’s residence in Cape May; he simultaneously

provided the City Council with copies of Director Caputo’s Voter Profile that

he received through the OPRA request, which did contain the house number.

3

Mr. Kratovil was then served with a Cease-and-Desist Notice pursuant to

Daniel’s Law by Director Caputo on official city letterhead, which essentially

warned that that Mr. Kratovil faced criminal and civil penalties if he repeated

the disclosure of such information and did not remove the information from

the Internet or wherever it had been made available.

What Mr. Kratovil did—and what he hopes to do by writing a news story

about what he found—is at the core of what is protected by Article I,

Paragraph 6 of the New Jersey Constitution: speech about the activities of

local government. As the U.S. Supreme Court said in Daily Mail: “state action

to punish the publication of truthful information seldom can satisfy

constitutional standards.” By threatening criminal and civil sanctions for

reporting on truthful, legally obtained information, the City and its Director of

Police have chilled, and are chilling, Mr. Kratovil’s free speech and free press

rights and unconstitutionally violated the Daily Mail principle protected by

the New Jersey Constitution. Thus, this Court should issue appropriate

restraints on enforcement of this statute as applied.

4

FACTUAL ALLEGATIONS

A. New Jersey’s version of Daniel’s Law.

Daniel’s Law was enacted by the New Jersey Legislature and signed by

Governor Philip Murphy in November 2020 in response to the tragic murder of

Daniel Anderl, the son of U.S. District Court Judge Esther Salas and her

husband, Mark Anderl. In that case, law enforcement identified the primary

suspect as an aggrieved attorney who had been litigating a case before Judge

Salas who later killed himself.

2

The law—with criminal and civil provisions—prohibits disclosure of the

residential addresses of certain persons covered by the law (“Covered

Persons”) on websites controlled by state, county, and local government

agencies. Covered Persons include former, active, and retired judicial officers,

prosecutors, and members of law enforcement and their immediate family

members residing in the same household. The state created a website to

provide details of the law:

2

President Biden signed into law the similarly-intentioned Daniel Anderl

Judicial Security and Privacy Act on December 23, 2022, which aims to

improve the safety and security of federal judges and their immediate family

members by requiring government agencies, persons, businesses, and

associations to remove the personal information of judges from public view

within 72 hours of receiving a request for removal. It also authorizes grants to

state and local governments to create programs that prevent the release of

personal information of judicial officers.

5

With respect to Internet postings other than those on

New Jersey state, county, and municipal government

websites, an authorized person, as defined by law,

seeking to prohibit the disclosure of the home address

or unpublished home telephone number of any covered

person shall provide written notice to the entity or

person advising that they are an authorized person and

that they are requesting that the entity or person cease

the disclosure of the information and remove the

protected information from the Internet or where it is

otherwise made available. See, N.J.S.A. 2C:20-31.1(c)

and N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(a)(2).

[N.J. Dep’t of Cmty. Affs., Daniel’s Law,

https://danielslaw.nj.gov/Default.aspx?ReturnUrl=%2f

(last visited July 6, 2023)]

But then the law goes much further, specifically providing that upon

notice, a person shall not disclose the home address or unpublished telephone

number of a covered person. N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(a)(1). The law explains how

a Covered Person provides notice. N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(a)(2). It then provides

for significant civil damages including $1,000 per violation, punitive damages,

and attorney’s fees. N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(c). Although the law lists some

exceptions to the general prohibition on disclosure of voter records, namely

that certain persons and entities may disclose the information consistent with

the purposes for which they received it, but only for those purposes, it is not at

all clear how that would apply to the news media. N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(e) (but

see N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(f) (not requiring media to remove previously printed

newspapers containing the home address of a Covered Person)). In addition to

6

the significant civil liability, the law sets forth almost identical statutory

language making a violation punishable as a criminal sanction: a “reckless

violation of [Daniel’s Law] is a crime of the fourth degree. A purposeful

violation of [the law] is a crime of the third degree.” N.J.S.A. 2C:20-31.1(d).

B. The Daniel’s Law warning to Plaintiff

Charles Kratovil (“Kratovil” or “Plaintiff”) is a journalist, activist, and

editor of New Brunswick Today (“NBT”), an independent, print and digital

newspaper founded in 2011 with the mission to improve the level of civic

discourse in the City of New Brunswick by accurately covering local

government and demanding transparency and accountability from those in

authority. Verified Complaint (“Compl.”) ¶7. Since its inception, NBT has

received several prestigious journalism awards from organizations including

the New Jersey Society of Professional Journalists and the New Jersey Press

Association, and numerous other acknowledgments of its investigative work

and coverage of major public issues, including public safety and corruption. Id.

NBT has written extensively on the city police department and its

civilian Police Director, Defendant Anthony Caputo (“Director Caputo” or

“Vice Chair Caputo”). Compl. ¶10. Director Caputo was a city policeman and

then police director before he retired in 2010 with a $115,000 annual pension.

7

Id. Sixteen months later, he was rehired at a salary of $120,000 to be Police

Director again (in addition to receiving his pension). Id.

Since being rehired, Director Caputo has, upon information and belief,

not attended a single City Council meeting, and remains the only city

department head who does not routinely attend at least some of the Council’s

public meetings. Compl. ¶10. Director Caputo also does not typically host or

attend community meetings, town halls, press conferences, or other public

events. Id. During the course of his reporting, Plaintiff learned that Director

Caputo actually lived in Cape May, New Jersey, more than a two-hour drive

from New Brunswick. Id.

Since at least 2010, Director Caputo served as a mayor-appointed board

member of the New Brunswick Parking Authority (“NBPA”) Board of

Commissioners, an autonomous local government agency with significant

political power. Compl. ¶11. The NBPA is among the state’s largest municipal

parking authorities, and Director Caputo is currently the Vice Chair of the

NBPA’s Board. Id. Although the NBPA Board has consistently met in-person,

even throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Vice Chair Caputo has not attended

any board meetings in-person since August 4, 2021. Id. When he does

participate, it is only via telephone. Id. He is the only board member who does

8

not make regular appearances at meetings, and he is the only member who

does not live in New Brunswick. Id.

NBT’s coverage of the city government has drawn the enmity of many

New Brunswick officials, including Director Caputo, toward NBT and Mr.

Kratovil over the years. Compl. ¶12. Under Director Caputo’s leadership, the

NBPD has lacked transparency and violated public disclosure laws. Id. On

several occasions, Plaintiff has successfully brought affirmative litigation

against the city government related to its lack of compliance with OPRA,

N.J.S.A. 47: 1A-1, et seq., and these cases often involved police matters. Id.

Between 2013 and 2017, Director Caputo acquired at least two

properties in Cape May City, at a combined cost of $1.2 million. Compl. ¶13.

According to his financial disclosure statements, he used at least one of the

properties to produce significant rental income each year since 2014. Id. In

January 2021, Caputo promoted Joseph “JT” Miller (“Deputy Director Miller”)

to the rank of Deputy Director. Compl. ¶14. That same month, Deputy Director

Miller purchased a Cape May property for $695,000. Id. The property is

located in the same small condominium complex as one of Director Caputo’s

homes. Id.

In the course of researching this news story on Director Caputo’s

residency in March 2023, Mr. Kratovil filed an OPRA request with the Cape

9

May County Board of Elections Records Custodian seeking Director Caputo’s

Voter Profile (“the Voter Profile”). Compl. ¶15. On March 20, 2023, he

received a heavily redacted version of the Voter Profile after the records

custodian claimed in an email that full disclosure would “interfere with his

[Director Caputo’s] reasonable expectation of privacy,” under Burnett v.

County of Bergen, 198 N.J. 408 (2009). Id.

In a subsequent email exchange with the Records Custodian, Mr.

Kratovil pointed out that the New Jersey Supreme Court’s decision in Brennan

v. Bergen County Prosecutor’s Office, 233 N.J. 330 (2018) overruled Burnett,

and the Court determined there was no expectation of privacy for home

addresses. Compl. ¶16. Finally, on April 17, 2023, he received a far less

redacted version of the Voter Profile, with only Director Caputo’s date of birth

redacted. Id.

The lawfully obtained Voter Profile reveals that as of November 30,

2022, Director Caputo had changed his registered voting address to an address

in Cape May, N.J. after having voted regularly in New Brunswick since at

least 1998. Compl. ¶17.

On March 14, 2023, Plaintiff asked Director Caputo via email if he still

lived in New Brunswick and Deputy Director Miller responded on his behalf:

10

“The public release of a law enforcement officer’s place of residence is

protected under Daniel’s Law.” Compl. ¶18.

On March 22, 2023, Plaintiff attended the NBPA Board of

Commissioners meeting and asked Vice Chair Caputo (who participated via

telephone) if he still resided in New Brunswick. Compl. ¶19. Vice Chair

Caputo responded: “Thank you for your comment.” Id. Plaintiff then shared

with the Board the heavily redacted Voter Profile he had lawfully obtained at

that point, stated that it showed Director Caputo had registered to vote in a

different county, and asked whether there was a residency requirement for

NBPA Commissioners. Id. The commissioners responded collectively that they

could not answer the question, but they promised a response in the future. Id.

Plaintiff has found that it is virtually impossible for him to get direct,

on-the-record responses from City Council members outside of their meetings,

so he asks many of his most important questions during the public portion of

the meetings. Compl. ¶20.

On April 5, 2023, Plaintiff attended the New Brunswick City Council

regular public meeting and, during the public participation portion, he asked

whether Anthony Caputo was still a New Brunswick resident. Compl. ¶21. One

member of the Council said she believed Director Caputo was still a resident,

while another said he believed Director Caputo had moved out of town. Id.

11

The Council President said she would look into the question and report back.

Id. Plaintiff also asked if there was a residency requirement to serve on the

NBPA Board, whether Director Caputo was a full-time employee, and how

many hours he was “putting in from Cape May.” Id. No answer was received

at or after the meeting. Id.

On May 3, 2023, Plaintiff again attended the New Brunswick City

Council meeting, where he spoke briefly during the public portion of the

meeting about Director Caputo’s official change of residence, the fact that the

residence was two hours or more from his duties in New Brunswick, and that

Director Caputo continued to serve on the NBPA Board as a non-resident.

Compl. ¶22.

During his speaking time at that May 3 meeting, Plaintiff publicly stated

the street where Director Caputo was registered to vote, but not the house

number. Compl. ¶23. Upon information and belief, there are more than 60

addresses on the street that he mentioned and the house numbers run to three

digits. Id. Plaintiff did, however, provide Council members with copies of the

less redacted Voter Profile he received through the later OPRA request, which

contained the exact street address. Id. He also made a digital video recording

of the meeting. Id.

12

The issue of the residency of a Police Director and appointed member of

the Parking Authority, who has largely absented himself from the City of New

Brunswick, is indisputably a matter of public concern and an issue related to

news coverage of government, which is a central tenant of the First

Amendment.

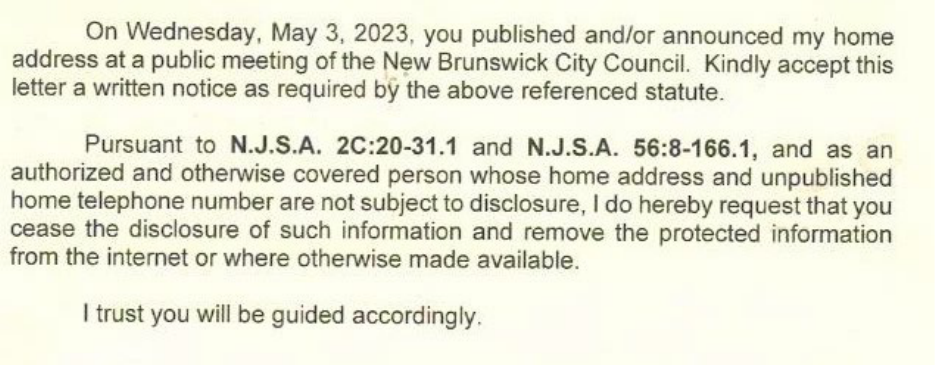

On May 15, 2023, Plaintiff received a letter via both certified mail and

United States Mail on the letterhead of the New Brunswick Police Department

dated May 4, 2023, which purportedly constituted “NOTICE pursuant to

N.J.S.A. 2C:20-31.1 & N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1[.]” Compl. ¶25. Two days later he

received the same letter from Deputy Director Miller via email. The letter

read:

As noted above, both statutes cited in the letter require the Cease-and-

Desist Notice, after which a violation would be subject to criminal (a third- or

fourth-degree crime) and civil penalties. Compl. ¶27. Plaintiff continued to

13

prepare to write a story about the residency issue. Compl. ¶29. He made an

OPRA request of the City’s Records Custodian, seeking the unedited and

unredacted video recording of the May 3, 2023, City Council meeting. Id. He

also asked during the public portion of a subsequent City Council meeting why

the City’s video still had not been posted to the internet in a timely fashion. Id.

The City’s public information officer told Plaintiff that “there was some

content . . . that required some redaction.” Id.

On May 26, 2023, the Records Custodian provided the following OPRA

response to Plaintiff, containing a Vimeo link:

Your Opra Request is asking for an unedited and

completed video footage of the May 3, 2023 Council

meeting. Please click the link below and be advised, the

complete video provided is an edited version with an

audio redaction. The unedited version contained

personal identifying information, such as a home

address, of a covered person. The redaction has been

made in accordance to Daniel’s Law.

https://vimeo.com/cityofnewbrunswick/may3?share=c

opy

[Compl. ¶30.]

The video shows that during the public portion of the May 3, 2023,

meeting, beginning at 1:12:19, Plaintiff asked a series of questions about

various issues of public concern in the City for which the City Council has

responsibilities. Compl. ¶31. At about the 1:15:59 mark of the video, Plaintiff

14

began to disclose what he learned about Director Caputo living in Cape May.

Id. He handed out copies of the Voter Profile to the City Clerk and the video

depicts the clerk providing the copies Plaintiff brought with him to the

Council. Id. Plaintiff continued to discuss the issue for more than a minute

until 1:17:23. Id.

In the version of the video provided under OPRA, the City unlawfully

redacted much of Plaintiff’s public participation. This redaction went beyond

mere mention of any address: the City redacted any discussion of the Director

living outside New Brunswick. In the version of the video provided under

OPRA, the portion containing Plaintiff’s public participation was improperly

redacted, even beyond mention of any address, to redact any discussion of the

Director living outside New Brunswick. Compl. ¶32. In fact, the recording

provided by the city mutes the audio of Plaintiff’s entire statement about the

residency issue, not simply the second or two where he stated Director

Caputo’s actual street of residence. Id.

The Records Custodian stated that the City made the “redaction”

pursuant to Daniel’s Law. Compl. ¶33.

15

ARGUMENT

To be entitled to interim relief pursuant to R. 4:52-1, a party must show

(a) that the restraint is necessary to prevent irreparable harm, i.e., that the

injury suffered cannot be adequately addressed by money damages, which may

be inadequate because of the nature of the right affected; (b) that the party

seeking the injunction has a likelihood of success on the merits; (c) that the

equities favor the party seeking the restraint; and (d) that the restraint does not

alter the status quo ante. Crowe v. De Gioia, 90 N.J. 126, 132–36 (1982).

Plaintiff easily satisfies these requirements.

Whether the City’s Police Director and vice chair of a powerful local

government board should live so far from New Brunswick is a matter of public

concern that Plaintiff has every intention to write and speak about as a

journalist. The voting address of the Police Director, and the addresses of other

real estate owned by the Director, or of other business ventures or sources of

income that he may have, are all integral parts of the news story. Compl. ¶34.

Plaintiff has these materials in his possession and is prepared to write a

news story describing the residency issue. The existence of Daniel’s Law and

the pendency of the Warning Notice act as an unconstitutional prior restraint

on freedom of speech and the press and/or unconstitutional application of a

state statute.

16

I. Plaintiff is likely to succeed on the merits of his free speech

and free press claim.

A. The Daily Mail principle forbids the state from

punishing the publication of lawfully obtained

information, absent a need of the highest order.

1. First Amendment prohibitions against prior

restraint.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that

“Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech. . . .” U.S.

Const. amend. I. The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

made the First Amendment restriction on governmental interference with free

speech applicable to the states. U.S. Const. amend. XIV, § 1; 44 Liquormart,

Inc. v. Rhode Island, 517 U.S. 484, 516 (1996); Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310

U.S. 296, 303 (1940).

Since at least Near v. Minnesota, the U.S. Supreme Court has applied the

Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause to the First Amendment to protect

the press against prior restraint from state action. 283 U.S. 697, 722-23 (1931).

Forty years later, in the famed Pentagon Papers case, New York Times Co. v.

United States, the government obtained injunctions against the New York

Times and Washington Post for publishing parts of a classified study on the

history of the Vietnam War that, while having been stolen from a government

vendor, were received legally by the two newspapers. 403 U.S. 713, 714

17

(1971) (plurality). The Supreme Court issued a brief per curiam opinion

dissolving the injunctions and reaffirming the high bar for justification for

such restraints. Id. The brief decision (every Justice wrote their own as well)

set forth the almost impossibly high bar the government would need to meet to

curtail publication of the Pentagon Papers:

“Any system of prior restraints of expression comes to

this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its

constitutional validity.” Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan,

372 U.S. 58, 70 (1963); see also Near v. Minnesota, 283

U.S. 697 (1931). The Government “thus carries a heavy

burden of showing justification for the imposition of

such a restraint.” Organization for a Better Austin v.

Keefe, 402 U.S. 415, 419 (1971).

[Id.]

2. The State Constitution’s broader reach.

Article I, Paragraph 6 of the New Jersey Constitution provides: “Every

person may freely speak, write and publish his sentiments on all subjects,

being responsible for the abuse of that right. No law shall be passed to restrain

or abridge the liberty of speech or of the press.” N.J. Const. art. I, ¶ 6. In

Hamilton Amusement Center. v. Verniero, the New Jersey Supreme Court

explained that it ordinarily interprets the State Constitution’s free speech

clause to be no more restrictive than the federal free speech clause. 156 N.J.

254, 264–65 (1998). Two exceptions to this general rule cited by the Court,

which are not involved here, are political expressions at privately-owned-and-

18

operated shopping malls, N.J. Coal. Against War in the Middle East v. J.M.B.

Realty Corp., 138 N.J. 326, 366–70 (1994), and defamation, Sisler v. Gannett

Co., 104 N.J. 256, 271 (1986).

There are no decisions under the New Jersey Constitution specifically

adopting a broader prohibition on prior restraint than the already strict

standard adopted under the First Amendment. But in Sisler, an early

defamation case involving imposition of actual malice on a private individual

through operation of the fair comment privilege, the New Jersey Supreme

Court described much stronger state constitutional protections in making plain

that “[o]ur constitution and common law have traditionally offered scrupulous

protection for speech on matters of public concern.” 104 N.J. at 271.

“The entire thrust of Art. I, § 6 is protection of speech.”

Maressa v. New Jersey Monthly, 89 N.J. 176, 192 cert.

denied, 459 U.S. 907…(1982). This provision, more

sweeping in scope than the language of the First

Amendment, has supported broader free speech rights

than its federal counterpart. E.g., State v. Schmid, 84

N.J. 535 (1980), app. dism. sub nom. Princeton Univ.

v. Schmid, 455 U.S. 100…(1982) (right of free speech

on private university campus). Legislative enactments

echo the Constitution, evincing a paramount concern

for freedom of speech and press. N.J.S.A. 2A:84A-21

(Shield Law); Maressa v. New Jersey Monthly, …89

N.J. 176 (1982). Thus, our decisions, pronounced in the

benevolent light of New Jersey’s constitutional

commitment to free speech, have stressed the vigor

with which New Jersey fosters and nurtures speech on

matters of public concern.

19

[Id.]

Thus, while there are no analogous prior restraint cases in New Jersey,

the State Constitution should be applied in such a fashion as to foster and

nurture free speech on public concern in this matter.

3. The Daily Mail principle.

The basic principle that the government may not prevent reporting on

matters of public significance, using lawfully obtained material, absent

extraordinary need, has been developed and reaffirmed in a series of cases over

the last half century.

a) Cox Broad. Corp. v. Cohn.

In 1972, Martin Cohn filed an action against media entities for revealing

the identity of his 17-year-old daughter during a newscast covering guilty

pleas by six youths who were indicted for her rape and murder, in violation of

a Georgia law meant to protect the privacy of rape victims. Cox Broad. Corp.

v. Cohn, 420 U.S. 469, 471–72 (1975). The reporter learned the name of the

victim from the indictments available for his inspection in the courtroom,

which were public records. Id.

After noting the news media’s important role in reporting governmental

proceedings, the Court weighed the privacy interests of the victim against the

First Amendment interests at stake and found it not to be a close contest:

20

even the prevailing law of invasion of privacy generally

recognizes that the interests in privacy fade when the

information involved already appears on the public

record. The conclusion is compelling when viewed in

terms of the First and Fourteenth Amendments and in

light of the public interest in a vigorous press. The

Georgia cause of action for invasion of privacy through

public disclosure of the name of a rape victim imposes

sanctions on pure expression—the content of a

publication—and not conduct or a combination of

speech and nonspeech elements that might otherwise be

open to regulation or prohibition.

[Id. at 494–95.]

Further, the Court noted that because the records were public, any

attempt to impose sanctions would be unconstitutional:

By placing the information in the public domain on

official court records, the State must be presumed to

have concluded that the public interest was thereby

being served. Public records by their very nature are of

interest to those concerned with the administration of

government, and a public benefit is performed by the

reporting of the true contents of the records by the

media. The freedom of the press to publish that

information appears to us to be of critical importance

to our type of government in which the citizenry is the

final judge of the proper conduct of public business. In

preserving that form of government the First and

Fourteenth Amendments command nothing less than

that the States may not impose sanctions on the

publication of truthful information contained in official

court records open to public inspection.

[Id. at 495 (emphasis added).]

21

Similar to a prior restraint, the law prevented the media from reporting

truthful information that it had in its possession. The Court essentially declared

the law unconstitutional as applied.

b) Neb. Press Ass’n v. Stuart.

In Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, the Court held unconstitutional

an order prohibiting the press from publishing certain information they came

to learn during an open public hearing, declaring that the order “plainly

violated settled principles.” 427 U.S. 539, 568 (1976). The Nebraska Supreme

Court previously allowed, as modified, an order that precluded the news media

from publishing certain details of a high-profile murder case—like the

existence of a confession—in order to protect the accused’s right to an

impartial jury. Id. at 545. The United States Supreme Court agreed that the

state courts had “acted responsibly, out of a legitimate concern, in an effort to

protect the defendant’s right to a fair trial.” Id. at 555. The Court also agreed

“that there would be intense and pervasive pre-trial publicity concerning this

case” that might impact the defendant’s ability to have a fair trial. Id. at 562–

63. Still, the Court held that the state court was not justified in imposing a

restraint on reporting on what had been a hearing open to the public. Id. at 568.

The Court reaffirmed that “the barriers to prior restraint remain high and the

presumption against its use continues intact.” Id. at 570.

22

c) Okla. Publ’g Co. v. Dist. Ct.

The following year, in Oklahoma Publishing Company v. District Court,

a newspaper challenged application of a state statute providing for closed

juvenile proceedings unless specifically open to the public when the press had

been allowed into a hearing without an order and had photographed a juvenile

defendant. 430 U.S. 308, 308–09 (1977). The newspaper did not seek to have

the statute declared unconstitutional, only to have the Court declare that a trial

court’s injunction against the press was unconstitutional. Id. at 310. The Court

agreed, ruling that the state cannot prohibit the publication of widely

disseminated information obtained at court proceedings, which were, in fact,

open to the public. Id. Like Cox Broadcasting, the Court said, the name of the

party protected by the statute “was placed in the public domain.” Id. at 311.

d) Landmark Commc’ns, Inc. v. Virginia.

In Landmark Communications, Inc. v. Virginia, the Court considered a

state criminal statute protecting the confidentiality of complaints about a

judge’s disability or misconduct. 435 U.S. 829, 830 (1978). The Virginian

Pilot wrote a story about a pending inquiry into a judge’s fitness, and a grand

jury indicted the newspaper, which was fined $500 plus costs, a conviction that

was upheld in the state courts. Id. at 831–34. Like the cases before it, the Court

found the interests protected by the law insufficient when balanced against the

23

First Amendment. The Court was especially dismissive of protecting judicial

reputations or even administration of judicial discipline outside of the

Commission itself:

We conclude that the publication Virginia seeks to

punish under its statute lies near the core of the First

Amendment, and the Commonwealth’s interests

advanced by the imposition of criminal sanctions are

insufficient to justify the actual and potential

encroachments on freedom of speech and of the press

which follow therefrom.

[Id. at 838.]

e) Smith v. Daily Mail Publ’g Co.

West Virginia’s statute protecting the anonymity of juvenile offenders

required written approval of the court before a juvenile offender’s name could

be published in a newspaper. In its 1979 Daily Mail decision, the U.S.

Supreme Court reviewed and reaffirmed each of its previous decisions on the

issue in declaring that whether a statute acts as a prior restraint or penal

sanction, “it must nevertheless demonstrate that its punitive action was

necessary to further the state interests asserted.” 443 U.S. at 102. And while

the Court refused to declare a categorial approach to this rule, it was no less

definite about how the statute could not be enforced in view of the First

Amendment considerations:

None of these opinions directly controls this case;

however, all suggest strongly that if a newspaper

24

lawfully obtains truthful information about a matter of

public significance[,] then state officials may not

constitutionally punish publication of the information,

absent a need to further a state interest of the highest

order. These cases involved situations where the

government itself provided or made possible press

access to the information. That factor is not controlling.

Here respondents relied upon routine newspaper

reporting techniques to ascertain the identity of the

alleged assailant.

[Id. at 103.]

In addition, while the Court said that the reasons for protecting the

anonymity of juvenile defendants was important, there was no evidence to

demonstrate that the imposition of criminal penalties was necessary. Id. at 105.

The Court also pointed out that while the statute applied to newspapers, it was

underinclusive because it did not apply to other forms of media and therefore

did not accomplish its stated purpose. Id. at 104–05.

f) The Fla. Star v. B.J.F.

Ten years later, in The Florida Star v. B.J.F., the Court was again faced

with a statute making it unlawful to “‘print, publish or broadcast . . . in any

instrument of mass communication’” the name of the victim of a sexual

offense. 491 U.S. 524 (1989). A Florida newspaper, The Florida Star, copied

the name from a police report subsequently included in a police blotter

column. Id. at 527. Ironically, the release was not only against police

25

regulations but also against the newspaper’s own internal policy, neither of

which affected the Court’s determination. Id. at 528.

Again, there was no dispute the newspaper had lawfully obtained the

information and that the story as a whole was a matter of “paramount public

import[,]” and the Court concluded once more that “[i]mposing liability on the

Star does not serve ‘a need to further a state interest of the highest order.’” Id.

at 525, 537.

The Court explained that because “government retains ample means of

safeguarding significant interests upon which publication may impinge,

including protecting a rape victim’s anonymity, . . . [w]here information is

entrusted to the government, a less drastic means than punishing truthful

publication almost always exists for guarding against the dissemination of

private facts.” Id. at 534.

Secondly, the Court said that punishing the press for its dissemination of

information which is already publicly available “is relatively unlikely to

advance the interests in the service of which the State seeks to act. It is not, of

course, always the case that information lawfully acquired by the press is

known, or accessible, to others.” Id. at 535. “But where the government has

made certain information publicly available,” the Court said, “it is highly

anomalous to sanction persons other than the source of its release.” Id.

26

Third, the Court explained that allowing the media to be censored in this

fashion would result in “timidity and self-censorship.” Id. (quoting Cox

Broad., 420 U.S. at 496).

Florida authorities argued to the Supreme Court that among the most

important reasons for the statute were the privacy of victims of sexual

offenses; the physical safety of such victims, who may be targeted for

retaliation if their names become known to their assailants; and the goal of

encouraging victims of such crimes to report these offenses without fear of

exposure, all of which the Court acknowledged as “highly significant

interests[.]” Id. at 537. However, for several reasons, the Court determined that

those reasons were not of the highest order.

For example, the government failed to police itself in disseminating

information. Thus “it is clear under Cox Broadcasting, Oklahoma Publishing,

and Landmark Communications that the imposition of damages against the

press for its subsequent publication can hardly be said to be a narrowly tailored

means of safeguarding anonymity.” Id. at 538. Once the government places

information in the public domain, “reliance must rest upon the judgment of

those who decide what to publish or broadcast,” Id. (citing Cox Broad., 420

U.S. at 496).

In addition, the Florida Star Court, just as in the Daily Mail case, cited

27

the underinclusiveness of the Florida statute. Although that statute prohibited

the publication of identifying information only if this information appears in

an “instrument of mass communication,” a term the statute does not define, it

left open the opportunity for those who would “maliciously spreads word of

the identity of a rape victim . . . despite the fact that the communication of

such information to persons who live near, or work with, the victim may have

consequences as devastating as the exposure of her name to large numbers of

strangers.” Id. at 540.

g) Bartnicki v. Vopper.

The final case in this series came 12 years later in Bartnicki v. Vopper,

which involved a radio host broadcasting a recording of an intercepted

telephone conversation between a teachers’ union president and a union

negotiator, who were involved in contentious negotiations with a school board

in Pennsylvania. 532 U.S. 514, 518–19 (2001). The recording, which was

intercepted by unknown persons, and brought by a union opponent to be

played on a local radio show, was clearly obtained in violation of the federal

wiretapping act for the interceptor, the intermediary, and those who played the

recording. Id. at 521. The Court accepted the fact that the recordings were

made intentionally and both the radio host and the person who provided the

tape “had reason to know” it was unlawful to do so. Id. at 524–25. The only

28

question before the Court was whether the application of the wiretap laws in

such circumstances violated the First Amendment. Id. at 521.

The Court noted that (1) the “respondents played no part in the illegal

interception[,]” found out about the interception only after it occurred, and

never learned the identity of the interceptor; (2) “access to the information on

the tapes was obtained lawfully, even though the information itself was

intercepted unlawfully by someone else[;]” and (3) “the subject matter of the

conversation was a matter of public concern.” Id. at 525.

The Court acknowledged the government’s arguments that the interests

served by the statute—removing an incentive for parties to intercept private

conversations, minimizing the harm to persons whose conversations have been

illegally intercepted, and even the need to avoid chilling expression of those

who fear their conversations may be intercepted—were adequate to justify the

law. Id. at 529, 533. But the Court quickly held that “it by no means follows

that punishing disclosures of lawfully obtained information of public interest

by one not involved in the initial illegality is an acceptable means of serving

those ends.” Id. at 529–30.

“Although there are some rare occasions in which a law suppressing one

party’s speech may be justified by an interest in deterring criminal conduct by

another . . .” the Court held, “this is not such a case.” Id. at 530.

29

In other words, the outcome of these cases does not turn

on whether [the wiretapping statute] may be enforced

with respect to most violations of the statute without

offending the First Amendment. The enforcement of

that provision in these cases, however, implicates the

core purposes of the First Amendment because it

imposes sanctions on the publication of truthful

information of public concern.

[Id. at 533–34.]

Importantly, the Supreme Court also applied the Daily Mail protections

to a non-journalist, Jack Yocum, the head of a local taxpayer organization who

testified he found the tape recording of the call in his mailbox, recognized the

voices, played it for some members of the school board, and later delivered it

to the radio host. Id. at 519.

h) The New Jersey Supreme Court’s recognition of the

Daily Mail Principle.

In G.D. v. Kenny, the New Jersey Supreme Court tackled a similar issue.

205 N.J. 275 (2011). There, the plaintiff sought damages for a political

campaign’s revelation of his expunged criminal record. Id. at 282. The

expungement statute prohibited disclosure of expunged records with some

exceptions. Id. at 294–96. Plaintiff argued that because his criminal record had

been expunged, his conviction—as a matter of law—was deemed not to have

occurred and a campaign flyer’s description of the conviction was a violation

of his privacy rights. Id. at 290. The Court, in affirming dismissal, went right

30

to the heart of the high standard required to punish publication of truthful

information:

The publication of truthful information lawfully

obtained is protected from criminal prosecution by the

First Amendment except in the rarest of circumstances.

Florida Star v. B.J.F.,; Near v. Minnesota, (“No one

would question but that a government might prevent

actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the

publication of the sailing dates of transports or the

number and location of troops.”). In Smith v. Daily Mail

Publishing Co., two newspapers published the names of

juvenile offenders in violation of a state statute that

prohibited the publication of such information. The

United States Supreme Court held that, consistent with

the First Amendment, a state could not “punish the

truthful publication of an alleged juvenile delinquent’s

name lawfully obtained by a newspaper.” (“We hold

only that where a newspaper publishes truthful

information which it has lawfully obtained, punishment

may lawfully be imposed, if at all, only when narrowly

tailored to a state interest of the highest order. . . .”).

[Id. at 299–300 (citations omitted).]

This passage reaffirms our State Supreme Court’s commitment to the

Daily Mail principle.

B. The Daily Mail principle applies to Daniel’s Law

under the New Jersey Constitution.

Because Plaintiff obtained the address information lawfully and it is

undisputedly a matter of public concern, Daniel’s Law cannot be applied as a

sanction to him or any other journalist whether they receive the address

information via public access or through traditional reporting. None of the

31

Supreme Court cases cited above declared any of the sanctioning statutes

unconstitutional, but every one of them found their application a violation of

the First Amendment because they sanctioned an individual for repeating or

reporting information of public concern that the statute was created to protect.

So too here.

1. In some instances, homes addresses are matters of

public concern.

News reporters should not be threatened by the government with

prosecution or civil liability if they write a news story or share information

about something questionable going on with a public servant’s address. There

are countless instances where a public servant’s home address is a matter of

significant public concern. Here, the government employee lives so far out of

town that a daily appearance at work is unlikely, but the street address of a

Covered Person might be newsworthy for other reasons too: a suspicious real

estate transaction;

3

noncompliance with a residency requirement;

4

illegally

3

See, e.g., Abbie VanSickle, Justice Thomas Failed to Report Real Estate Deal

With Texas Billionaire, N.Y. Times (Apr. 13, 2023),

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/13/us/politics/clarence-thomas-harlan-crow-

real-estate.html (describing questionable land deal engaged in by United States

Supreme Court Justice and a billionaire).

4

See, e.g., Mikenzie Frost, Residency questions continue for BPD’s Acting

Commissioner Worley, Fox45News (June 13, 2023),

https://foxbaltimore.com/news/local/residency-questions-continue-for-bpds-

acting-commissioner-worley (reporting on Baltimore police commissioner who

lives outside city in violation of city charter).

32

voting in the wrong jurisdiction;

5

or other issues. This is not to say that news

media could not use their own discretion in attempting to disguise actual street

numbers or figure out other ways to tell the story, but that would be a

voluntary act rather than a legal requirement, just as most news organizations

agree not to use youthful defendants’ names or the names of rape victims.

Daniel’s Law already makes it even more difficult for journalists to

ascertain home addresses for public servants, and, as applied in this

circumstance, at least, it creates a chilling fear of criminal and civil

prosecution. Having received written Notice required under Daniel’s Law,

Plaintiff has reasonable grounds to fear that he would be a target for an

enforcement action that would seek to criminalize his investigative journalism

work. Because of the potential for criminal and civil penalties, Plaintiff seeks

declaratory relief from this Court asking no more than to recognize the free

speech and free press rights set forth in the above cases.

5

See, e.g., Stephen Koranda, Kansas Rep. Steve Watkins Charged With

Felonies Over Voter Registration At UPS Store, NPR, (July 14, 2020),

https://www.npr.org/2020/07/14/891242761/kansas-rep-steve-watkins-charged-

with-felonies-over-voter-registration-at-ups-st (describing criminal charges

flowing from member of U.S. House of Representatives registering to vote in a

district where he did not live)

.

33

2. The Daily Mail principle applies whether

information is obtained through a public record or

through traditional reporting techniques.

In this case, Plaintiff obtained Director Caputo’s address through an

OPRA request, which placed it in the public domain. But even if Plaintiff had

obtained it through other reporting channels, the analysis would remain the

same, as Director Caputo’s address is likely known to many on his street or his

social circles, which also places it into the public domain. “A free press cannot

be made to rely solely upon the sufferance of government to supply it with

information.” Daily Mail, 443 U.S. at 104.

Daniel’s Law provides that voter records should be made available only

as redacted except for use in political campaigns – by the chairpersons of

county or municipal committees, challengers, candidates, and vendors working

for Boards of Election. N.J.S.A. 47:1B-3. Thus, if Director Caputo had timely

provided notice to Cape May that he was a Covered Person, the Cape May

Records Custodian arguably provided more information than permitted under

Daniel’s Law. But this case does not concern what information should be

disclosed by government, rather what journalists may do with information they

obtain through lawful means. As the U.S. Supreme Court explained in The

Florida Star v. B.J.F, the fact that a government agency failed to redact or

34

withhold information does not make a journalist’s “ensuing receipt of this

information unlawful.” 491 U.S. at 536.

Indeed, when journalists obtain information through ordinary sources,

they may generally publish that information, even when their source illegally

obtained the information. Bartnicki, 532 U.S. at 535 (“a stranger’s illegal

conduct does not suffice to remove the First Amendment shield from speech

about a matter of public concern.”).

3. Daniel’s Law is not narrowly tailored to achieve its

laudable goals.

In Daily Mail, the United States Supreme Court reminded government

entities that even where important interests (there, the identity of juvenile

defendants) are at stake, the government also must demonstrate that the

associated prohibitions and penalties are necessary to achieve that interest. 443

U.S. at 105–06. In that case, the statute applied to newspapers but not to other

forms of media. Id. at 104–05. The underinclusiveness of that statute

undermined any assertion of narrow tailoring. Id.

Similarly, Daniel’s Law at N.J.S.A. 47:1B-3 provides that non-redacted

voter records can be made available only for use in political campaigns—by

the chairpersons of county or municipal committees, challengers, candidates,

and vendors working for Boards of Election. This widespread, yet calculated

dissemination of the same information to established political parties,

35

undermines any claim of narrow tailoring and undermines the constitutionality

of the prohibition, as applied to journalists like Plaintiff. See, e.g., Donrey

Media Grp. v. Ikeda, 959 F. Supp. 1280, 1286 (D. Haw. 1996) (an individual

who is a reporter as well as a member of a certain political party could very

well gain access to the voter registration records because of her status as a

member of a political party, eliminating any legitimate state interest in voter

privacy served by the statute).

In addition to the underinclusiveness of Daniel’s Law, it also appears to

be overinclusive in an unrealistic manner when it states “a person, business, or

association shall not disclose or re-disclose on the Internet or otherwise make

available, the home address or unpublished home telephone number of any

covered person….” N.J.S.A. 56:8-166.1(a). The law, in a vague and

ambiguous way, appears to bind every person to silence, not just journalists.

As written, a person could not tell a story about an annoying neighbor (if the

neighbor were a Covered Person) nor could a person give directions to a

mutual friend that referenced a Covered Person’s home (e.g., “to get to the

park, pass Bob’s house, go a block, and turn right”). Moreover, the statute is

vague in that it does not explain whether it refers to the exact street address

(123 Main Street), the street (Main Street), the town, or the county within

which the Covered Person resides.

36

4. Although Daniel’s Law serves a laudable interest, it

does not amount to a need of the highest order.

None of the cases that have established or reaffirmed the Daily Mail

principle adopted a categorical rule. But all of the cases have made clear that

the circumstances under which the government may prohibit the publication of

truthful information on important topics are exceedingly rare. See, e.g., G.D. v.

Kenny, 205 N.J. at 299–300 (citing Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. at 716, for the

proposition that “[n]o one would question but that a government might prevent

actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of the sailing

dates of transports or the number and location of troops.”).

The publication of Director Caputo’s address as part of reporting about

areas of certain public significance, lies near the core of the State

Constitution’s protection of free speech and free press; and the State’s

interests, however altruistic, are insufficient to justify the actual and potential

encroachments on freedom of speech and the press that flow from Daniel’s

Law’s prohibition on Plaintiff’s truthful reporting. As described above, courts

have previously found that protecting the names of rape victims (Cox Broad.,

420 U.S. at 496; Fla. Star, 491 U.S. at 541), juvenile offenders (Okla. Publ’g

Co., 430 U.S. at 311–12; Daily Mail, 443 U.S. at 106), or people who

benefited from expungements (G.D., 205 N.J. at 300), or preventing

publication of classified national security information (N.Y. Times Co., 403

37

U.S. at 714), wiretapped conversations (Bartnicki, 532 U.S. at 535), highly

prejudicial pretrial publicity (Neb. Press Ass’n, 427 U.S. at 570), or

information about judicial discipline (Landmark Commc’ns, 435 U.S. at 845)

do not constitute a “need of the highest order[.]”

II. Plaintiff easily meets the remaining standards for

granting temporary restraints.

Crowe v. De Gioia requires additional showings in order to obtain

interim relief: the risk of irreparable injury, the balance of the equities, and

maintenance of the status quo ante. 90 N.J. at 132–36. Plaintiff can

demonstrate all of them.

A. Absent interim relief, plaintiff will continue to

suffer harm because the only sufficient remedy for

his ongoing injury is an injunction.

“The loss of First Amendment freedoms, for even minimal periods of

time, unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury.” Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S.

347, 373 (1976) (plurality). When free speech rights are “‘either threatened or

in fact being impaired’” injunctions are the only method to prevent ongoing

injuries. Davis v. N.J. Dep’t of L. & Pub. Safety, Div. of State Police, 327 N.J.

Super. 59, 69 (Law. Div. 1999) (quoting Elrod, 427 U.S. at 373).

Moreover, because Daniel’s Law affects significant constitutional

interests, the harms at stake will be suffered not only by the Plaintiff, but by

any journalist seeking to report on issues of public concern related to a

38

Covered Person’s home address. Accordingly, absent preliminary relief,

immediate irreparable harm exists here for Plaintiff and others.

B. The balance of the equities, including the public

interest, favors the issuance of an immediate

injunction.

The Court should grant immediate temporary restraints because the

Defendants will not suffer injury from an injunction allowing Plaintiff to

report on truthful information about Director Caputo’s residence far from New

Brunswick. If the case is adjudicated in the normal course, it is uncertain how

long the Plaintiff will be prevented from reporting on an issue of public

significance. Plaintiff will either have to not report the story or risk significant

civil and criminal penalties.

A preliminary injunction also serves the public interest. When the public

interest is at stake, “courts, in the exercise of their equitable powers, ‘may, and

frequently do, go much farther both to give and withhold relief . . . than they

are accustomed to go when only private interests are involved.’” Waste Mgmt.

of N.J., Inc. v. Union Cnty. Utils. Auth., 399 N.J. Super. 508, 520–21 (App.

Div. 2008) (quoting Yakus v. United States, 321 U.S. 414, 441 (1944)). In this

case, there is a significant public interest in protecting free press and free

speech.

39

C. The restraint does not alter the status quo ante.

Issuing an injunction maintains the status quo. For years, Plaintiff and

other investigative journalists were free to engage in reporting on issues of

public concern, even if that reporting revealed the home address of a public

official. Daniel’s Law, at least as applied to Plaintiff in these circumstances,

seeks to change that status quo. More than a decade ago, in G.D. v. Kenny, the

New Jersey Supreme Court could not “conceive that the Legislature intended

to punish, under our Criminal Code, persons who have spoken truthfully about

lawfully acquired information long contained in public records . . . .” 205 N.J.

at 300. An injunction maintains the state of the law for journalists that existed

for decades prior to the passage of Daniel’s Law.

40

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, Daniel’s Law is unconstitutional as

applied to Plaintiff, and Defendants must be enjoined from using the law to

prevent Plaintiff’s reporting on a truthful, lawfully obtained matter of public

concern.

Respectfully submitted,

____________________________

Alexander Shalom (021162004)

Jeanne LoCicero

American Civil Liberties Union

of New Jersey Foundation

570 Broad Street, 11th Floor

P.O. Box 32159

Newark, New Jersey 07102

(973) 854-1714

ashalom@aclu-nj.org

DATED: July 12, 2023