Sheep Diseases

The Farmers’ Guide

Original version developed by Emily Litzow for Department of Primary Industries and Regions,

Biosecurity SA Animal Health.

Updated in 2022 by Red Meat and Wool Growth Program with contributions from Dr Elise Spark,

Dr Jeremy Rogers, Dr Celia Dickason and Chris Van-Dissel for Department of Primary Industries

and Regions, Biosecurity SA Animal Health.

Funded by SA Sheep Industry Fund, Biosecurity SA and the Red Meat and Wool Growth Program.

Use of the information and advice in this guide is at your own risk. The Department of Primary

Industries and Regions and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the

use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy,

reliability, currency or otherwise. The entire risk of the implementation of the information and advice

which has been provided to you is assumed by you. All liability or responsibility to any person using

the information and advice is expressly disclaimed by the Department of Primary Industries and

Regions and its employees.

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

2

Contents

How to use this guide 4

Reporting serious or unusual animal disease signs 5

Funding for disease investigations 6

Key to disease diagnoses by signs and symptoms 7

Key to disease diagnoses by season 9

Key to poisoning or toxicity by plant 10

Exotic diseases 11

Exotic diseases 12

Learn how to recognise emergency animal diseases 13

Anthrax 14

Bluetongue 15

Foot and mouth disease (FMD) 16

Sheep diseases & conditions 17

Acidosis (grain overload) 18

Annual ryegrass toxicity (ARGT) 19

Arthritis 20

Botulism 21

Cheesy gland (CLA) 22

Cobalt deficiency 23

Coccidiosis 24

Copper deficiency 25

Copper poisoning 26

Dermatophilosis and dermatitis (‘dermo’, lumpy wool) 27

Exposure losses 28

Foot abscess 29

Footrot 30

Grass tetany (hypomagnesaemia) 31

Large lungworm 32

Listeriosis (circling disease) 33

Lupinosis 34

Mastitis 35

Milk fever (hypocalcaemia) 36

Nitrate poisoning 37

Ovine brucellosis (Brucella ovis) 38

Ovine Johne’s disease (OJD) 39

Oxalate poisoning 40

Perennial ryegrass staggers 41

Phalaris poisoning 42

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

3

Phalaris staggers 43

Photosensitisation 44

Pinkeye 45

Pneumonia 46

Polioencephalomalacia (PEM, star gazing disease) 47

Pregnancy toxaemia (twin lamb disease) 48

Pulpy kidney (enterotoxaemia) 49

Pyrrolizidine alkaloid poisoning 50

Scabby mouth 51

Selenium deficiency (white muscle disease) 52

Tapeworm cysts (bladder worm, sheep measles, hydatids) 53

Tetanus (lockjaw) 54

Vibriosis (Campylobacteriosis) 55

Other conditions 56

Sheep lice 57

Sheep worms 58

Flystrike 59

Management guides 60

Good biosecurity 61

One Biosecurity 62

Vaccination 63

Grain introduction 64

NLIS obligations 65

Fit to load 66

Humane destruction 67

Acknowledgments & further reading 68

Useful contacts and online resources back cover

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

4

How to use this guide

This guide has been designed as a quick-reference tool to

help farmers take action when faced with a broad range of

sheep diseases on the farm. It will help you assess signs

and symptoms and identify possible causes and provides

information on diagnosis, treatment options, prevention

and general sheep health management.

Printed and digital resources are referenced throughout to

assist you with further, more detailed reading on a number

of sheep diseases, conditions and best practice guidelines.

You will also find a list of useful contacts and websites on

the back of this guide.

Photo credit: Animal Health Australia

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

5

Always keep an eye out for serious or unusual signs and

symptoms in livestock including:

• unexplained deaths

• sores or ulcers on feet or inside mouth (this may result

in a reluctance to eat or move)

• excessive salivation (drooling should always be treated

suspiciously)

• reduction in milk yield from cows and eggs from chickens

• diarrhoea, especially if it has blood in it

• excessive nasal discharge (unless you know what has

caused it)

• staggering, head drooping or severe lameness, especially

if more than one animal at the same time.

Serious animal diseases must be reported. Early reporting

provides the best chance to contain and manage an outbreak

before it spreads. If you notice any serious or unusual signs

or symptoms with your animals, you can:

• call the 24-hour Emergency Animal Disease Hotline

on 1800 675 888

• contact your local Department of Primary Industries and

Regions (PIRSA) Animal Health office (see back cover for

phone numbers)

• contact your local veterinarian.

Reporting serious or unusual

animal disease signs

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

6

Funding for disease investigations

Subsidies are available to support private veterinary

investigations into animal diseases where an infectious

agent is a potential cause. This is to help producers

maintain and demonstrate South Australia’s highly

regarded animal health status.

The program covers all livestock species, companion

animals, and wildlife (including feral animals) and is aimed

primarily at early detection and diagnosis of emergency

animal diseases.

For further information, contact your local veterinarian,

who may access these funds through PIRSA.

Scan QR code to learn more

about disease surveillance

or visit www.pir.sa.gov.au/

livestock-disease-surveillance

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

7

Abscess

• Cheesy gland

• Foot abscess

Abortion/stillbirth

• Ovine brucellosis

• Listeriosis

• Vibriosis

Anaemia

• Oxalate poisoning

• Worms

Blindness

• Pinkeye

• Polioencephalomalacia

Convulsions

• Annual ryegrass toxicity

• Grass tetany

• Phalaris poisoning

• Phalaris staggers

• Polioencephalomalacia

• Pulpy kidney

• Perennial ryegrass

staggers

• Tetanus

Coughing

• Lungworm

• Pneumonia

Downer sheep

• Annual ryegrass toxicity

• Botulism

• Exposure losses

• Grass tetany

• Lungworm

• Milk fever

• Oxalate poisoning

• Phalaris poisoning

• Phalaris staggers

• Polioencephalomalacia

• Pregnancy toxaemia

• Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

poisoning

Infected wound

• Malignant oedema

Infertility

• Ovine brucellosis

Ill thrift

• Cobalt deficiency

• Coccidiosis

• Copper deficiency

• Copper poisoning

• Lungworm

• Lupinosis

• Nitrate poisoning

• Ovine Johne’s disease

• Oxalate poisoning

• Polioencephalomalacia

• Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

poisoning

• Selenium deficiency

• Worms

Jaundice

• Copper poisoning

• Lupinosis

• Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

poisoning

Key to disease diagnoses by signs and symptoms

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

8

Lameness

• Acidosis

• Arthritis

• Foot abscess

• Footrot

Leg paddling

• Annual ryegrass toxicity

• Grass tetany

• Listeriosis

• Oxalate poisoning

• Phalaris poisoning

• Polioencephalomalacia

Nervous/neurological

signs

• Annual ryegrass toxicity

• Botulism

• Copper deficiency

• Grass tetany

• Listeriosis

• Lupinosis

• Milk fever

• Oxalate poisoning

• Perennial ryegrass

staggers

• Phalaris poisoning

• Phalaris staggers

• Pulpy kidney

• Tetanus

Salivation/frothing

at mouth

• Botulism

• Grass tetany

• Listeriosis

• Phalaris poisoning

Scabs

• Cobalt deficiency

• Dermatophilosis

• Lupinosis

• Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

poisoning

• Scabby mouth

Scours

• Acidosis

• Coccidiosis

• Copper poisoning

• Nitrate poisoning

• Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

poisoning

• Worms

Sudden death

• Acidosis

• Annual ryegrass toxicity

• Copper poisoning

• Exposure

• Flystrike

• Grass tetany

• Listeriosis

• Milk fever

• Oxalate poisoning

• Phalaris poisoning

• Polioencephalomalacia

• Pregnancy toxaemia

• Pulpy kidney

• Ryegrass staggers

• Tetanus

• Worms

Wool abnormalities

• Copper deficiency

• Dermatophilosis

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

9

Key to disease diagnoses by season

Spring

Sept/Oct/Nov

• Annual ryegrass toxicity

• Cobalt deficiency

• Foot abscess

• Lupinosis

• Oxalate poisoning

• Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

poisoning

• Selenium deficiency

Summer

Dec/Jan/Feb

• Annual ryegrass toxicity

• Cobalt deficiency

• Lupinosis

• Pneumonia

• Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

• Poisoning

• Perennial ryegrass

staggers

• Selenium deficiency

Autumn

March/April/May

• Lungworm

• Lupinosis

• Phalaris poisoning

• Phalaris staggers

• Pneumonia

• Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

poisoning

• Perennial ryegrass

staggers

Winter

June/July/August

• Exposure losses

after shearing

• Foot abscess

• Lungworm

• Nitrate poisoning

• Oxalate poisoning

• Phalaris poisoning

• Phalaris staggers

• Pneumonia

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

10

Key to poisoning or toxicity by plant

Annual ryegrass toxicity

• Annual ryegrass

(Lolium rigidum)

Lupinosis

• Lupin stubble

(Lupinus species)

• Lupin hay

(Lupinus species)

• Lupin grain

(Lupinus species)

Nitrate poisoning

• Capeweed

(Arctotheca calendula)

• Oats (Avena sativa)

• Canola (Brassica napus)

• Wild turnip (Brassica rapa)

Oxalate poisoning

• Soursob

(Oxalis pes-caprae)

• Sorrel (Acetosella vulgaris)

Phalaris poisoning

• Phalaris

(Phalaris aquatica)

Phalaris staggers

• Phalaris

(Phalaris aquatica)

Photosensitisation

• Salvation Jane/

Paterson’s curse

(Echium plantagineum)

• Heliotrope/potato weed

(Heliotropium europaeum)

• Caltrop (Tribulus terrestris)

• St John’s Wort

(Hypericum perforatum)

• Buckwheat (Polygonum

fagopyrum)

• Hairy panic (Panicum

effusum)

• Sweet grass (Panicum

laevifolium)

• Lantana (Lantana camara)

• Fungus of facial eczema

(Pithomyces chartarum)

• Fungus of lupinosis

(Phomopsis

leptostromiformis)

• Blue-green algae

(Anacystis cyanea)

Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

poisoning

• Salvation Jane/

Paterson’s curse

(Echium plantagineum)

• Heliotrope/potato weed

(Heliotropium europaeum)

• Caltrop (Tribulus terrestris)

Perennial ryegrass

staggers

• Perennial ryegrass

(Lolium perenne)

Exotic diseases

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

12

Exotic diseases

This sheep has barbers pole (Haemonchus).

These sheep have lice.

This sheep has bluetongue, an exotic disease.

This sheep has scrapie, an exotic disease.

Exotic diseases don’t always look spectacular. They often look the same as common diseases seen every

day on South Australian farms.

Help protect the future of our livestock industry by seeking veterinary assistance as soon as you notice a

problem and report your concerns to the Emergency Animal Disease Hotline on 1800 675 888.

Source: National Animal Disease Information Service (NADIS)

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

13

Use the new app to learn how to identify signs of emergency

animal disease (EAD) in sheep.

Download to your mobile phone by searching ‘Sheep EAD AR’

in the app store.

The tool generates a flock of augmented reality sheep providing

an opportunity for the user to identify the sick animal by looking

for signs and symptoms.

The diseases included in the tool are:

• foot and mouth disease

• bluetongue

• scrapie

• sheep pox

Learn how to recognise

emergency animal diseases

Scan QR code

to watch the

demonstration

video.

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

14

Problem

Anthrax has not been diagnosed in SA

for many years, but occasional detections

have occurred in NSW and as well as

isolated outbreaks in WA and QLD.

Anthrax is caused by a bacteria that

affects cattle, sheep, goats and humans.

The bacterium produces spores when

exposed to air that persist in soil for many

years. The disease is spread by contact

with infected animals or by feed and water

that have been contaminated. An outbreak

could be a possible cause of unexplained

sudden death in livestock and can

affect trading opportunities locally and

internationally. More common in summer

but can occur all year round.

Humans can contract anthrax by handling

infected animals, carcasses, animal

products and wool. Take care if handling

animals suspected of dying from anthrax

and contact your medical practitioner

immediately if you have been exposed.

Signs and symptoms

• Sudden death usually first sign,

preceded by rapidly worsening

weakness and staggering.

• Bloody or tarry discharge from mouth,

nose or anus of dead animals.

• Sudden drop in milk production,

red-stained milk or urine.

Diagnosis

• If unexplained sudden death occurs

and anthrax is suspected do not open

or move the carcass. Seek advice

from your local veterinarian or call

your PIRSA animal health office for

assistance diagnosing anthrax with

a ‘penside’ test.

• Diagnosis is most likely in animals

that have recently moved from eastern

states.

• A lack of rigor mortis, with rapid

decomposition of carcass. Pulpy

kidney is often assumed to be the

cause.

Treatment

• Treatment is rarely possible as affected

animals die quickly.

• High doses of penicillin may be

effective in early cases, however may

interfere with anthrax vaccine.

Prevention

• Vaccination is effective, full protection

takes 10-14 days to develop after

administration.

• Vaccination may only occur with the

approval of SA’s Chief Veterinary

Officer (Chief Inspector of Stock).

Emergency animal disease, notiable and zoonotic

Anthrax

If you suspect your stock have

anthrax contact your local PIRSA

Animal Health office immediately

or report to the Emergency Animal

Disease Hotline on 1800 675 888.

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

15

Problem

Bluetongue virus (BTV) is spread by

biting insects such as Culicoides midges,

resulting in production losses and high

death rates (up to 70% in sheep).

Many BTV strains that cause severe

disease are exotic to Australia. Some

BTV strains are present in northern and

north-eastern parts of Australia, but SA is

a transmission free area.

SA’s reputation for high health status

livestock plays a key role in accessing

livestock export trade markets and

provides significant economic benefits

to rural communities. Some countries

only source livestock from areas free of

BTV, highlighting the importance of SA

maintaining its BTV-free status.

Signs and symptoms

• Fever (40 to 41°C), nasal discharge,

breathing difficulty.

• Lameness and reddening around the

coronary band (top of the hoof).

• Swelling of the lips, tongue and head.

• Some animals have a swollen, blue-

coloured tongue, but this isn’t always

seen and is not a reliable sign.

• Rapid weight loss and drop in

production.

• Death rates of 20 to 40% common.

Diagnosis

• If unexplained sudden death occurs

and bluetongue is suspected do not

open or move the carcass.

• To prevent spread of disease it is

critically important to seek advice

from your local veterinarian or call

Emergency Animal Disease Hotline

on 1800 675 888 immediately.

Treatment

• No effective treatment for bluetongue.

Prevention

• Isolation - if an outbreak occurs,

infected animals should be isolated.

• Insecticide - can be applied to reduce

insect numbers and minimise further

spread.

• Good hygiene - minimise the spread of

BTV by not sharing needles between

animals when injecting and thoroughly

washing and decontaminating other

equipment between animals.

Bluetongue

Emergency animal disease, notiable

If you suspect your stock have

bluetongue contact your local

PIRSA Animal Health office

immediately or report to the

Emergency Animal Disease Hotline

on 1800 675 888.

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

16

Foot and mouth disease (FMD)

Problem

Australia is free of foot and mouth disease

(FMD). It is a highly contagious animal

disease that affects cattle, sheep, goats,

pigs, deer and camelids (all cloven-hoofed

animals). An incursion of the virus would

have severe consequences for Australia’s

animal health and livestock trade.

FMD is carried by live animals and in meat

and dairy products, as well as in soil,

bones, untreated hides, and vehicles and

equipment used with infected animals. It

can also be carried on people’s clothing

and footwear.

Signs and symptoms

The most overt sign in sheep may be

lameness. This will appear similar to

endemic disease causes of lameness

like footrot. Close inspection is required

to see some of the other signs of FMD.

Affected sheep may:

• seem depressed

• develop sudden lameness

• be reluctant to stand

• form blisters around top of foot and

between claws

• have lesions on tongue and dental pad

(hard to detect)

• result in significant deaths in lambs.

Diagnosis

• Report these signs immediately to your

veterinarian or the Emergency Animal

Disease Hotline on 1800 675 888.

• Samples will be collected from your

animals and will be sent urgently to

an appropriate animal health laboratory

for diagnostic testing.

Treatment

• No effective treatment for FMD.

• Australia has detailed, well-rehearsed

FMD response plans and arrangements

in place should an outbreak occur.

Prevention

• Farm biosecurity - practice good farm

biosecurity at all times to prevent the

introduction and spread of FMD.

• Buying animals - only buy from

properties with good biosecurity and

disease control practices in place.

• Isolating animals - quarantine new

animals before introducing into existing

flocks.

• Traceability - keep National Livestock

Identification System (NLIS) and

property identification code (PIC)

records up to date.

• Report signs immediately to the

Emergency Animal Disease Hotline

on 1800 675 888.

Emergency animal disease, notiable

If you suspect your stock have

foot and mouth disease contact

your local PIRSA Animal Health

office immediately or report to the

Emergency Animal Disease Hotline

on 1800 675 888.

Scan QR code to learn

more about FMD or visit

www.pir.sa.gov.au/fmd

Sheep diseases & conditions

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

18

Problem

Sheep consume too much high-risk grain

such as wheat or barley which damages

their gut microflora. Some affected sheep

die, others recover slowly but are often

chronically lame.

Signs and symptoms

• Signs occur within 24-36 hours of

changing to a grain rich diet.

• Mildly affected sheep may have

diarrhoea but continue to eat.

• Severely affected sheep may stop

eating, be tender-footed, get up and

down frequently, lie down for extended

periods and grind their teeth.

Diagnosis

• History of eating high risk grain without

being acclimatised and clinical signs.

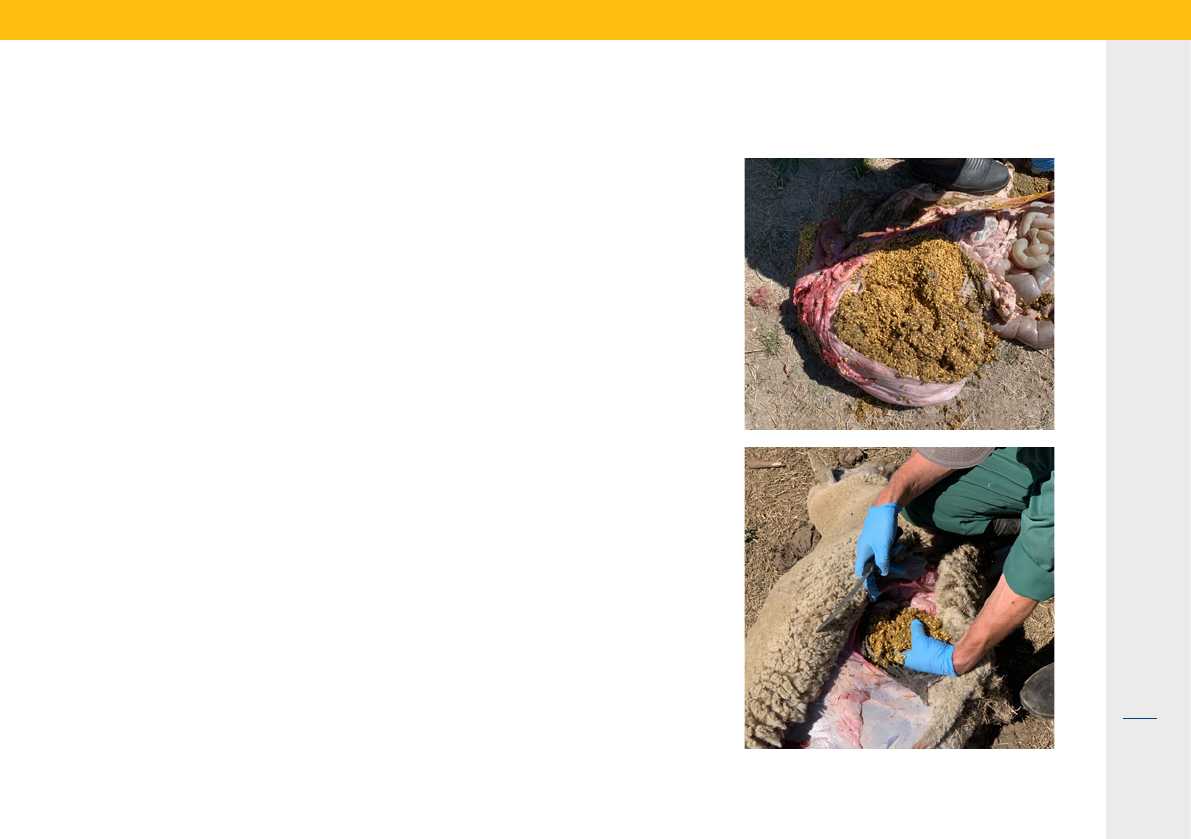

• On post mortem - damage to the

rumen wall and large amount of whole

grain in first stomach.

Treatment

• Diet - remove animals from grain, feed

good quality hay and provide access

to water.

• Consult veterinarian for a treatment

plan – fluids and sodium bicarbonate

(bicarb soda) can be helpful if given

quickly after overconsumption.

• Antibiotics - often recommended for

surviving sheep that have suffered

rumen damage.

Prevention

• Diet - high risk grains should be

gradually introduced. Avoid sudden

ration change, including grain type and

include grain buffering pellets with the

grain. A provision of extra calcium is

very important (see page 65).

• Access - take care when allowing

sheep to graze newly harvested

paddocks. Prevent sudden access to

unharvested paddocks or spilled grain

(e.g. around silos).

Acidosis (grain overload)

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

19

Annual ryegrass toxicity (ARGT)

Problem

Sheep graze annual ryegrass infested with

a nematode carrying a toxin-producing

bacterium. Severely affected sheep may

die within hours to a week after symptoms

show. Most deaths occur between

October and December when infected

plants have maximum toxicity.

Signs and symptoms

• Signs become obvious when a mob are

driven 100-200 metres, affected sheep

are unable to keep up and have a high-

stepping gait.

• Sheep may go down for minutes

or hours, then return to the mob

appearing normal.

• Severely affected sheep lose

coordination of hind limbs, fall over

with convulsions.

• Arched neck, stiff legs or paddling

legs sweeping the ground.

Diagnosis

• Signs develop four days to several

weeks after sheep graze infected

paddock or are fed infected hay.

• History of eating annual ryegrass

(including toxic hay) and clinical signs.

• On post mortem - rumen, pasture,

hay and grain can be tested for toxic

bacteria.

• Blood test analysis of liver and brain

can confirm the disease.

Treatment

• Access - remove animals from infected

paddock as quietly as possible.

• Humane destruction - sheep unable

to get up within 12 hours should be

humanely euthanised (see page 67).

Prevention

• Plant management - reduce number

of annual ryegrass plants by heavy

grazing in late winter and early spring,

with herbicide treatment and cutting

hay before plants become toxic.

• Introduced feed - all bought feed

should be accompanied by a vendor

declaration.

• Stock monitoring - monitor stock daily

during high-risk months in known

ARGT areas. Early detection will

minimise losses.

Mature annual ryegrass. Photo credit: Andrew Storrie

Annual ryegrass. Photo credit: DPIRD

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

20

Problem

Inflammatory condition of one or more

joints causing pain, lameness and

reduced animal productivity. Can affect

carcass quality leading to trimming and

condemnation.

Signs and symptoms

• First signs are heat and swelling around

one or more joints, commonly knee and

hock joints.

• Restricted and painful movement

of affected joints, mild lameness

developing to permanent lameness.

Diagnosis

• Mostly seen in lambs prior to weaning

due to bacteria entering through broken

skin (e.g. the umbilicus at birth, marking

or mulesing wounds).

• Examining the joints for swelling and

heat.

• On post mortem - bone changes in the

joints, thickened joint fluid and tissue

around the joint.

Treatment

• Consult veterinarian for a treatment

plan - if detected early, antibiotic

treatment can reduce the extent of

damage.

Prevention

• Vaccination - given to ewes before

lambing and lambs at marking to

prevent one of the most common

causes of arthritis, Erysipelothrix.

• Stress - keep stress to a minimum at

lamb marking by avoiding extremes

in temperature, keep droving to a

minimum before and after marking

and allow lambs to mother up as soon

as possible.

• Good hygiene - at marking, avoid

overcrowding or extended holding in

yards and place lambs on their feet

when releasing from the cradle.

Arthritis

Scan QR code to learn

more on VR carcass

feedback tool

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

21

Problem

Sheep ingest a toxin produced by

Clostridium botulinum causing gradual

onset of paralysis and sometimes death.

Most common in pastoral areas in

association with phosphorus deficiency

as stock chew old bones for phosphorus.

Can also occur when sheep ingest

contaminated feed (e.g. rotting vegetable

or animal matter).

Signs and symptoms

• Early signs are staggering, loss of

appetite, drooling, mild excitability,

nervous twitching and jaw champing.

• As the disease progresses sheep

become dull, respiration becomes

laboured and flaccid paralysis of limbs

sets in.

• Affected sheep will go down and die

quietly, generally within two to three

days of initial signs.

Diagnosis

• Based on flock history and clinical

signs.

Treatment

• Humane destruction – severely

affected animals should be humanely

euthanised (see page 67).

• Diet - provide food and water while the

toxin runs its course.

Prevention

• Vaccination - vaccinate at risk sheep

on properties where phosphorus

deficiency or botulism is known to

be a problem. Two doses of botulism

vaccine one year apart provides lifelong

prevention (see page 63).

• Nutrition - address nutritional

deficiencies to prevent bone chewing.

Botulism

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

22

Treatment

• No effective treatment.

Prevention

• Vaccination - in combination with

clostridial vaccine, ensure annual

boosters are given one to six months

before shearing (see page 63).

• Shearing - shear in age groups,

youngest to oldest. Keep yard time to

a minimum for recently shorn sheep.

• Dipping - wait until cuts have healed

(two to four weeks post shearing),

dip oldest animals last, use disinfectant

in the dip.

• Good hygiene - if an abscess is

ruptured at shearing or crutching,

disinfect the handpiece, floor and

anything else contaminated.

Problem

Sheep affected with a bacterial infection

that causes abscesses in the lymph nodes

and lungs. Can affect wool production

and occasionally cause ill-thrift and

wasting. Affects carcass quality leading to

trimming and condemnation.

Signs and symptoms

• Often no obvious signs, but readily

detected in the carcass at slaughter.

• Recently formed abscesses containing

creamy, greenish pus that hardens into

layers, commonly found in lymph nodes

on the shoulder point, groin and lungs.

Diagnosis

• Burst abscesses may be seen at

shearing or CLA is detected in the

carcass at slaughter. Occasionally

abscesses can be found in the brain.

Cheesy gland (CLA)

Scan QR code to learn

more on VR carcass

feedback tool

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

23

Problem

Most common in young sheep during

spring and summer on properties with

sandy, coastal soils. Affected sheep

become deficient in vitamin B12, leading

to reduced energy metabolism, ill-thrift

and anaemia.

Signs and symptoms

• Reduced appetite, ill-thrift (poor doers),

anaemic, sometimes scaley ears and

nose.

• Sheep may have weepy eyes and

photosensitisation (page 44).

Diagnosis

• A blood test can detect vitamin

B12 deficiency.

Treatment

• Vitamin B12 injections, cobalt bullets

and grinders, cobalt supplements in

water or feed.

Prevention

• Vitamin B12 injections - in cobalt

deficient areas, lambs should be

injected at marking, and again two

months later (often in conjunction with

a clostridial vaccine, see page 63).

• Cobalt bullet - weaners remaining on

cobalt deficient pastures can be given

a cobalt bullet at three months old.

Cobalt deciency

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

24

Problem

Most common in lambs before and after

weaning and following transport stress

or overcrowding. Caused by protozoan

parasites that damage the intestinal wall,

leading to severe dehydration, weight loss

and death.

Can affect ewes from pastoral country

relocated to higher rainfall areas and

occasionally sheep in confinement

feeding situations.

Signs and symptoms

• Loss of appetite and weight loss.

• Scouring - often a dark brown liquid

containing flecks of blood or shreds of

intestinal lining.

• Severely affected lambs are obviously

weak, if driven will fall behind the mob

and may go down.

Diagnosis

• Clinical signs.

• Faecal worm testing can detect

coccidiosis but won’t indicate the

extent of damage to intestinal lining.

• On post mortem - examination of the

intestines, particularly large intestine.

Treatment

• Sulphadimidine - given by injection or

drench, two doses are recommended

three days apart. Contact your local

veterinarian.

• Hydration - acutely scouring animals

will benefit from electrolyte therapy to

replace fluids.

• Off label treatment (e.g. Baycox) - can

be used under veterinary prescription.

Prevention

• Diet - feed weaners well with a high

protein diet. Late lambs should not

graze on pastures used by earlier

lambs. Other treatments added

to formulated rations could be

considered.

• Stress - minimise stressful conditions.

• Good hygiene - cocciodiosis is

commonly associated with unhygienic

living conditions.

• Disease management - control

concurrent disease problems,

especially worms.

Coccidiosis

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

25

Problem

Occurs when sheep have insufficient

copper in their diet over a period of

weeks, most common on coastal sandy

soils, sandy loams and swamp land.

Leads to ataxia (uncoordinated

movement) in young animals, steely wool,

abnormal bone formation, ill-thrift and

scours in severe cases.

Signs and symptoms

• Wool abnormalities, ‘steely wool’ - loss

of crimp, hard feel to fleece, reduced

tensile strength and elasticity,

depigmentation of black fleece.

• Diarrhoea, anaemia, sway back and

uncoordinated staggery gait

• Fragile bones that may fracture easily

in young sheep, affected bones are thin

but not deformed.

Diagnosis

• A blood test or tissue analysis -

liver is the best sample to test.

• Pasture analysis.

Treatment

• Supplementation - options include

copper oxide capsules, copper

glycinate injections (e.g. Multimin) and

in-water treatments.

• Pasture or fertilizer treatments.

• Sheep should not be treated with

copper unless deficiency is confirmed

– excess copper can be toxic. Consult

your veterinarian.

Prevention

• Diet - copper absorption is

compromised by a diet high in other

competing minerals.

• Pasture - where concentration of

copper is low, top dress with copper.

• Copper oxide capsules or copper

glycinate injection - can be used in

areas where copper deficiency is

known.

Copper deciency

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

26

Diagnosis

• Based on flock history and clinical

signs.

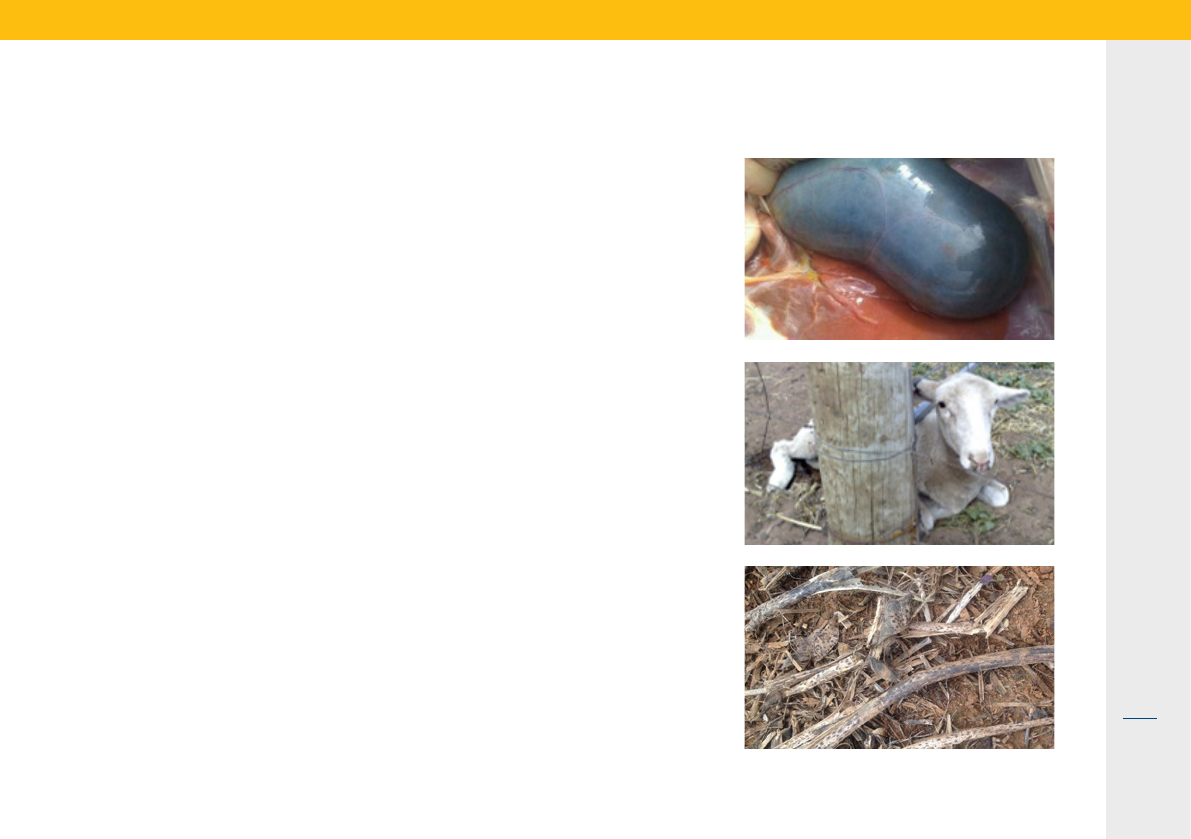

• On post mortem analysis of liver

samples.

Treatment

• Contact your local veterinarian for

acute cases – treatment is possible

but unlikely to be available in time.

• No effective treatment for chronic

copper poisoning.

• Reduce copper absorption - salt lick

blocks containing molybdenum may

reduce further copper absorption in

the gut.

Prevention

• Diet - avoid feedstuffs and

supplements with extra copper

unless animal has confirmed copper

deficiency.

• Stress - minimise stressful conditions

when handling animals.

Copper poisoning

Problem

Occurs when toxic levels of copper

accumulate in the liver, with sudden death

often the first indication, any survivors

develop jaundice. The three types of

copper toxicity include:

1. Acute copper poisoning - caused by

supplementing sheep that already have

normal to high copper reserves.

2. Chronic copper poisoning - occurs

when excessive copper accumulates

in the liver over a period of several

months.

3. Pyrrolizidine alkaloid poisoning -

certain plants such as heliotrope and

Salvation Jane can cause copper to

accumulate in the liver.

Signs and symptoms

• Acute copper poisoning - severe

diarrhoea (often bluish in colour), red-

brown urine, dehydration, death within

two days of recumbency.

• Chronic copper poisoning - sheep are

disinterested in surroundings, stand

apart from the mob, stop eating, red-

brown urine, jaundice. Death occurs

between three to five weeks after early

signs.

Salvation Jane

Heliotrope. Photo credit: DPIRD

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

27

Treatment

• Usually self-curing.

• Antibiotics - can speed recovery and

minimise risk of flystrike. Contact your

local veterinarian.

• Zinc - in some cases, zinc sulphate

washes can be effective after shearing

Prevention

• Wet sheep - minimise contact between

wet sheep and don’t keep wet sheep in

the yards any longer than necessary.

• Carrier sheep - sheep with mild lesions

are the main source of infection,

spreading the condition when fleece

becomes wet for extended periods.

• Shearing - shear affected sheep last

when dermatitis present to prevent

significant spread via the hand piece

comb.

Problem

A common skin infection caused by

Dermatophilus congolensis bacterium,

mainly in weaners and hoggets (especially

Merinos). Causes elevated body

temperature, hard scabs on skin under the

wool and can lead to occasional deaths.

Can make shearing difficult and result in

flystrike and wool damage. Occurs mostly

in medium to high rainfall areas.

Signs and symptoms

• On non-woollen areas including face

and ears - thin, flat scabs usually

shorter than 1 cm.

• On wool producing skin - a thick

discharge mats wool fibres together at

the base of the staple and dries into a

scab.

• Severely affected sheep have hard

plates of scabs across their back.

Diagnosis

• Examining affected sheep.

• Laboratory confirmation is necessary

for a definitive diagnosis.

• High protein feed may be a factor.

• Unusually wet or humid weather

Dermatophilosis and dermatitis (‘dermo’, lumpy wool)

Photo credit: Dr Will Berry

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

28

Problem

Sheep experience body heat loss

too quickly to maintain normal body

temperature, resulting in collapse,

becoming comatose and then death.

Most common within two weeks of

shearing, especially with extreme cold,

rain and windy conditions.

Signs and symptoms

• Sheep will seek shelter nearby and be

reluctant to move.

• If body heat loss continues sheep will

collapse, become comatose and die

within hours.

Diagnosis

• Consider factors including time

since shearing, available shelter,

current weather, sheep size and

body condition.

Treatment

• Shelter - protect stock from cold

conditions and draughts. Move stock

that have collapsed into a shed.

• Body temperature - if animal is down,

provide body insulation and warmth.

Prevention

• Shelter - recognise high risk weather

and move recently shorn animals to

shelter as early as possible.

Exposure losses

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

29

Diagnosis

• Based on foot examination of lame

sheep - abscess contains light brown

or green pus that will build up over time

and then burst.

• Can be confirmed by laboratory

analysis.

Treatment

• Hoof paring - toe abscesses respond

well to hoof paring which provides

drainage for the pus.

• Antibiotics - heel abscesses are

generally deeper and may require

antibiotic treatment. Contact your local

veterinarian.

• Natural healing - once the abscess

bursts, healing occurs without further

treatment.

Prevention

• Muddy paddocks - keep susceptible

sheep out of muddy paddocks where

possible.

Problem

Bacteria infects the toe or heel after a

foot injury, resulting in severe lameness,

reluctance to stand or move and

sometimes damage to foot joints.

Common in heavier sheep, rams, and

pregnant ewes.

Signs and symptoms

• Usually only one foot is affected -

becoming hot and swollen.

• Toe abscess in front foot - normal

infection site is a crack in the hoof.

• Heel abscess - more common in heavy

adult sheep, starts as a skin infection

between the toes and extends to the

heel.

• Sheep are very lame and lose condition

until the abscess bursts and pus drains

out.

• Distinguishable from footrot due to the

presence of swelling and pus and often

lesions that burst above the coronet.

Foot abscess

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

30

Footrot

Problem

A highly contagious bacterial disease of

one or more feet, resulting in reduced

growth, ewe fertility, growth rates and

productivity.

Flock outbreaks can cause significant

economic loss and incur high costs

associated with controlling and

eradicating the disease.

Signs and symptoms

• Inflamed, red, moist skin and pasty

scum between the digits.

• Chronic and severe lesions with

foul smell.

• Loss of appetite, raised body

temperature, extreme pain.

Diagnosis

• Based on examination of affected feet -

consult your local PIRSA Animal Health

office or veterinarian.

• Laboratory analysis - virulence test on

bacterial swab.

Treatment

A treatment or eradication program for

footrot involves three phases:

1. Control - footbathing or vaccination

during the spread period to reduce

level of infection in the flock to until

eradication becomes feasible.

2. Eradication - remove all infected sheep

during the non-spread period.

3. Surveillance - closely observe the flock

to make sure the disease has been

eradicated and to prevent reinfection.

Notiable disease

If you suspect your stock have

footrot contact your local PIRSA

Animal Health office or report to the

Emergency Animal Disease Hotline

on 1800 675 888.

Scan QR Code to learn more

about ‘Footrot’ or visit

www.sheepconnectsa.com.au/

management/health/foot

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

31

Treatment

• Supplementation - ewes respond

quickly to magnesium injections.

Treated sheep will get up and walk

away within minutes.

• Supplementation - as grass tetany

is often seen in conjunction with

low calcium, a solution containing

both calcium and magnesium is

recommended - this is readily available

from most rural stores.

• Timing - treatment must be given as

soon as possible after initial signs to

be effective.

Prevention

• Stress management - ewes with young

lambs should be handled as little as

possible as physical stress can bring

on grass tetany.

• Supplementation - magnesium

supplements should be available,

usually combined with calcium

supplements during periods of greatest

risk. Magnesium oxide can also be

sprayed on to hay if needed.

• Diet - providing hay when there is lush,

rapid pasture growth can reduce the

risk of disease.

Problem

Sheep develop low blood levels of

magnesium and or calcium, leading to

a stiff gait, paddling convulsions and

sudden death. Most common in prime

lamb mothers within six weeks of lambing.

Can be caused by pasture application

of excessive nitrogenous dressings and

potassium fertilizers.

Signs and symptoms

• Excitable and uncoordinated sheep,

throwing head about, grinding teeth

and shaking with muscle tremors.

• Affected sheep will collapse within

three hours, paddle their feet and froth

at the mouth.

• Violent convulsions and death

occurring four to six hours after

initial signs.

Diagnosis

• Based on flock history, signs shown by

affected sheep and the rapid response

to treatment.

• On post mortem - fluids from inside the

eye tested for magnesium levels.

Grass tetany (hypomagnesaemia)

Photo credit: Dr Bruce Watts

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

32

Problem

A parasitic worm that irritates the airway

causing weight loss and in severe cases

leads to pneumonia and death. Most

common in cooler, wetter areas, in

autumn or winter.

Lambs between four and six months

are most at risk, but sheep of all ages

can be affected.

Signs and symptoms

• Sheep affected by a moderate

infestation will experience coughing,

lethargy and weight loss.

• Severe infestation may cause breathing

difficulty, nasal discharge, ill thrift,

pneumonia, suffocation and death.

Diagnosis

• Lungworms identified in faecal egg

count and culture.

• On post mortem - lungworms found

in the airway and lungs.

Treatment

• Drenching - many sheep drenches are

registered for lungworm treatment.

Prevention

• Drenching - a regular drenching

program can prevent infestation.

Large lungworm

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

33

Listeriosis (circling disease)

Problem

A bacterial infection, causing encephalitis.

Can lead to high death rate including

abortion, stillbirth and neonatal death.

Mostly associated with sheep feeding

on mouldy silage or spoiled hay but can

be sporadic, with no obvious cause.

Listeriosis can present health risks to

humans.

Signs and symptoms

• First signs include depression,

anorexia, disorientation, head tilt and

circling. Animals usually die within a

few days.

• Abortion in ewes in late pregnancy.

• Facial paralysis (often one-sided)

causing droopy ear and eyelid, muzzle

pulling to one side and lack of muscle

tone in lip of the affected side.

• Profuse salivation.

Diagnosis

• Based on clinical signs.

• On post mortem - analysis of the brain

and spinal cord with tissue cultures.

Treatment

• Antibiotics - recovery depends on

early intervention with high doses of

antibiotics, however death can occur

despite treatment in severe cases.

Contact your local veterinarian.

• Diet- remove suspect feed

(e.g. spoiled silage).

• Isolation - separate ill sheep to prevent

spreading the disease between animals.

Prevention

• Diet - take care to avoid feeding

livestock spoiled silage.

• Pasture - avoid boggy pastures and

areas where soil has a high pH level.

Notiable disease

If you suspect your stock has

listeriosis contact your local PIRSA

Animal Health office or report to the

Emergency Animal Disease Hotline

on 1800 675 888.

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

34

Problem

Liver disease caused by eating lupin

stubbles or lupin grain infected with a

fungal toxin – any lupin stubble exposed

to rain following harvest is potentially

dangerous. Can lead to anorexia, collapse

and many deaths.

Sheep that recover will have chronic

liver damage and do poorly for months,

ewes can be predisposed to pregnancy

toxaemia the following season. Most

common in summer and autumn.

Signs and symptoms

• Affected sheep will stop eating, stand

apart or lag behind the mob and

become staggery when driven.

• Membranes and skin become

jaundiced and may shows signs of

photosensitisation (page 44).

• Some animals die within three days of

eating contaminated lupins, others will

slowly waste away over several weeks.

Diagnosis

• Based on a history of grazing lupin

stubble or eating lupin grain and

clinical signs.

• On post mortem - the animal will be

jaundiced with yellowing fat, skin and liver.

Treatment

• No effective treatment - follow steps

to minimise number of sheep affected

and severity.

• Hydration and shelter - remove the

mob from lupin stubble and grain

and give access to good quality water

and shelter.

• Diet - feed affected sheep a low protein

diet of hay and low protein grains.

Prevention

• Monitoring - check sheep daily when

grazing lupin stubble, drive the mob

for 500 metres to identify any animals

lagging behind.

• Rain - if rain occurs or there is a heavy

dew, remove sheep from lupin stubble.

• Timing - graze lupin stubbles as soon

as possible after harvest and remove

stock once all the grain has been eaten.

• History - avoid grazing sheep with a

history of liver damage.

• Quality and testing - feed sheep good

quality lupin grain. Hay, grain and stubble

can be tested to detect toxin levels at any

livestock feed testing service.

Lupinosis

Photo credit: Dr Belinda Edmonstone

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

35

Diagnosis

• History of ewes grazing in long

stubbles, sometime long grass.

• Scabby mouth infection has been

recorded as a cause.

Treatment

• Antibiotics - condition sometimes

responds to antibiotic injections if

detected early, but generally ewes with

hard, lumpy udders will not return to

function, and should be culled.

Prevention

• Weaning - if older lambs are suckling

ewes, earlier weaning may assist in

reducing cases.

Problem

Inflammation and infection of the udder

causing heat, swelling and lumps leading

to milk supply shutting down.

A common problem in ewes, usually

sporadic, but in some years seems to

affect more ewes than other times.

Signs and symptoms

• Heat and swelling of udder, usually

when lambs are more than four weeks

old, often twins, before weaning.

• Hard and lumpy udder, may be swollen,

painful and hot in early stages

• Milk supply shut down.

Mastitis

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

36

Treatment

• Supplementation - ewes respond

quickly to calcium injections - treated

sheep will get up and walk away

within minutes.

• Supplementation - as milk fever is

often seen in conjunction with low

magnesium, a solution containing

both calcium and magnesium is

recommended – this is readily available

from most rural stores.

• Timing - treatment must be given as

soon as possible after initial signs to

be effective. Consult your veterinarian.

Prevention

• Stress - ewes in last month of

pregnancy or with young lambs should

be handled as little as possible to avoid

physical stress.

• Diet - avoid grazing late pregnant or

lactating ewes on excessively lush

pasture or cereal crops.

• Supplementation - supply a mix of two

parts stock salt to one part stock lime

throughout pregnancy and lactation.

If ewes have been in confinement

consuming over 50% grain-based diet,

stock lime or calcium supplements

should be continuously available.

Problem

Very low levels of blood calcium, most

common in late pregnancy or the first few

weeks after lambing.

Can quickly lead to paralysis and death.

Often seen in conjunction with low blood

magnesium (hypomagnesaemia or grass

tetany). Confusion between milk fever and

pregnancy toxaemia is common.

Signs and symptoms

• Early signs include staggery gait,

muscle tremors, sheep move or

struggle when approached.

• Affected sheep go down in a sitting

position with head turned around to

their flank or may appear very weak

and unable to stand.

• Death will occur within 24-36 hours

of initial signs.

Diagnosis

• Based on flock history, clinical signs

and rapid response to treatment.

Milk fever (hypocalcaemia)

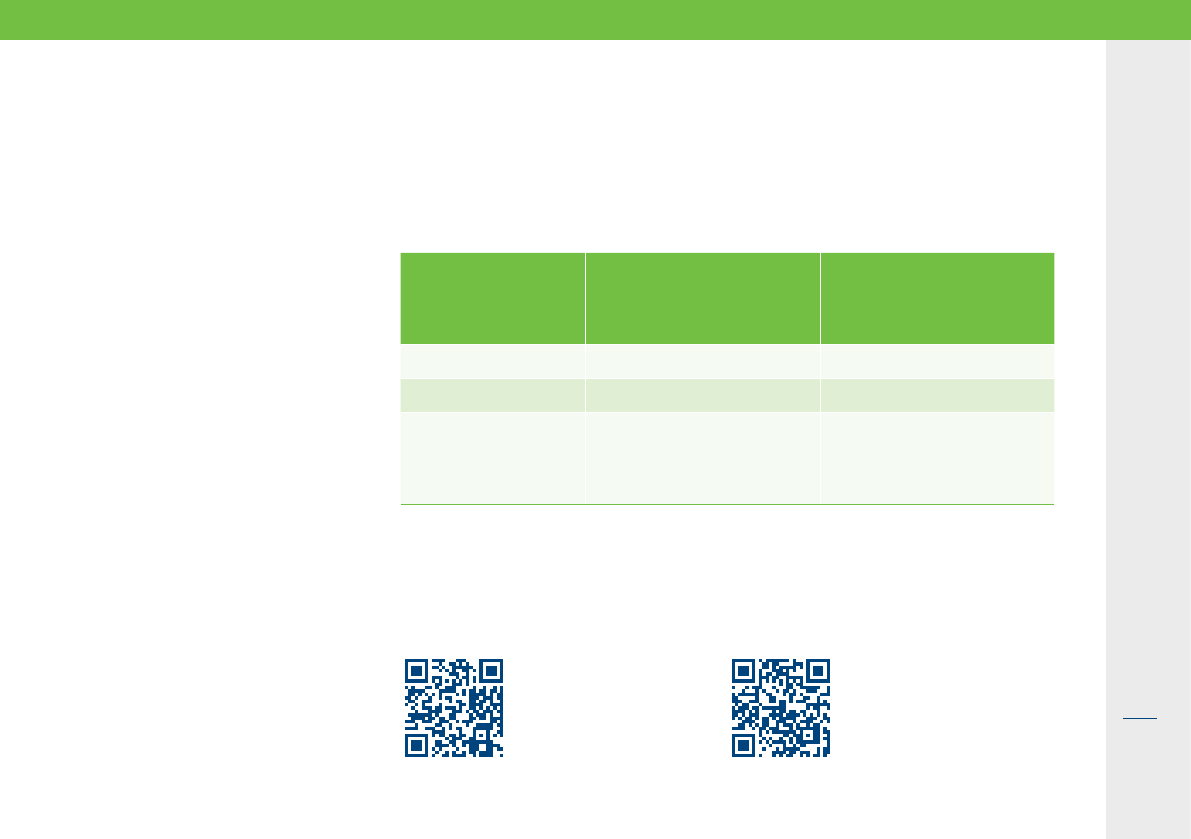

Difference between pregnancy

toxaemia and hypocalcaemia

Pregnancy

toxaemia

Hypocalcaemia

(milk fever)

Gradual onset Sudden onset

Sheep appear dull Sheep appear

alert but may

stagger or

convulse

Sheep are

unresponsive

when approached

Sheep move or

struggle when

approached

Death occurs

within 5-7 days

Death occurs

within 24 hours

Poor response

to treatment

Good response

to treatment

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

37

Problem

Sheep consume plants containing high

nitrate levels, leading to gut inflammation,

reduced oxygen in the blood and death.

Most common when sheep graze lush

pastures containing plants such as

capeweed, oats, canola and wild turnip.

Nitrate concentrations are usually higher

in young plants and following the break of

a drought in the first week after rain.

Signs and symptoms

• Main symptom of affected sheep is

scouring that does not respond to

worm drenches.

• Severely affected sheep may have

brownish or dark discolouration of

mucous membranes (e.g. gums).

• Breathing difficulty, due to changes in

the blood’s oxygen carrying capacity.

Diagnosis

• Based on a history of grazing plants

with a high nitrate level.

• On post mortem - fluids in the eye may

be seen.

Treatment

• No effective treatment.

• Diet - remove animals from high nitrate

feed to stop the scouring.

Prevention

• Diet - avoid grazing pastures

dominated by plants high in nitrate.

Green feed stock blocks are a viable

option on risky pastures.

• Reduce poisoning - provide access

to well dried cereal hay to prevent

further poisoning.

• Supplementation - supplement with

high starch grain (seek expert advice).

Nitrate poisoning

Wild turnip

Capeweed

Canola

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

38

Diagnosis

• Feeling the testicles - a lump can often

be felt in the epididymis (however

not all rams with brucellosis will have

palpable lumps and lumps can be from

other causes).

• A blood test can detect brucellosis two

to three weeks after becoming infected.

Treatment

• No effective treatment in individual

rams.

• Flock control by test and slaughter

program - contact your local

veterinarian for more information.

Prevention

• Buying rams - take care when selecting

rams, check testicles for lumps

and only buy from accredited ovine

brucellosis-free flocks.

• Ram sharing - don’t borrow, lend or

share rams. Maintain secure boundary

fences and check your own rams

before mating.

Problem

Rams develop bacterial venereal infection

leading to infertility and lowered lambing

percentage due to abortions, stillbirths

and birthing of small, weak lambs.

Most common in meat breed rams, less

common in Merinos. Can lead to extended

lambing periods.

Signs and symptoms

Rams:

• Soft, painful swelling of the epididymis

(the duct carrying the sperm from the

testicles).

• Duct doubles in size and hardens,

causing a blockage so no sperm can

be released.

Ewes:

• No obvious signs of ill health.

Ovine brucellosis (Brucella ovis)

InfectedNormal

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

39

Ovine Johne’s disease (OJD)

Problem

Incurable wasting disease with a very long

incubation period, often resulting in death.

Sheep can be infected at any age by

consuming pasture or water contaminated

with faeces.

Infected animals may carry and spread

the disease without ever showing

obvious clinical signs. Factors including

age, breed, stress and the presence of

other diseases can make sheep more

susceptible to OJD.

Signs and symptoms

• The disease has a long incubation

period - most infected sheep show no

signs of illness before two years of age.

• Severe wasting, leading to death within

six to 12 weeks from onset. Sheep

continue to eat and drink normally until

they are too weak to graze.

• Affected sheep will not respond to

drenching (appear wormy).

• Chronic scouring may sometimes be

seen but is not a common symptom.

• Classic symptom of the disease in

a mob is a distinct ‘tail’ with sheep

ranging in condition from good to very

poor.

Diagnosis

• Faecal sampling - a pooled faecal

sample from a selection of sheep

over two years old. Contact your local

veterinarian or PIRSA officer.

• On post mortem - affected animals will

have thickened intestines and enlarged

lymph nodes.

Treatment

• No effective treatment.

Prevention

• Purchase low risk stock - look for

SheepMAP accredited properties,

low-rainfall areas, approved vaccinate

status.

• Vaccination - consider vaccinating your

flock with Gudair

®

(see page 63).

Notiable disease

If you suspect your stock have OJD

report to the Emergency Animal

Disease Hotline on 1800 675 888.

• Mandatory requirements - completed

National Vendor Declarations

(NVD) and National Sheep Health

Declarations (NSHD) are mandatory for

all sheep entering and moving within

South Australia.

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

40

Chronic oxalate poisoning:

• Affected sheep are generally poor doers

and are anaemic with pale membranes.

• Sporadic death occurs within an

affected mob.

Diagnosis

• Based on a history of sheep grazing

high oxalate plants and clinical signs.

• On post mortem - examining the kidney,

pale white streaks may be seen, kidney

may feel gritty when cutting and fluids

in the eye.

Treatment

• Supplementation - can sometimes be

treated with calcium solution (as for

hypocalcaemia, page 36) but usually

ineffective.

• No effective treatment for chronic

poisoning.

Prevention

• Access - prevent hungry sheep

accessing paddocks with large amounts

of soursob or sorrel (e.g. around

shearing sheds).

• Sheep yards - clear sheep yards of

high oxalate plants before allowing

sheep to enter.

Problem

Sheep consume plants with a high

concentration of oxalates (e.g. soursob

and sorrel), resulting in muscle tremors

and a staggered gait, followed by

exhaustion, coma and death.

Often seen from March to June in SA

when soursobs are the only green feed

available before the break of the season.

A common cause of sudden death during

this period.

Signs and symptoms

Acute oxalate poisoning:

• First signs occur within one to three

hours of sheep eating high oxalate

plants.

• Affected sheep have muscle tremors

and a staggery gait, they go down but

will be alert and struggle when handled.

Leg paddling may occur.

• Within hours sheep become exhausted,

stop struggling, sink into a coma and

die soon after. Sheep will often be

found dead without signs of struggling.

Oxalate poisoning

Soursob

Sorrel

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

41

Diagnosis

• Based on a history of sheep grazing

toxic perennial ryegrass and clinical

signs.

Treatment

• Diet - remove sheep from toxic pasture.

Most animals will recover within four

days once removed.

• Stress - avoid disturbing affected

animals and move as quietly as

possible.

Prevention

• Sheep yards - plant cultivars that are

inoculated with non-toxic endophytes.

• Diet - monitor sheep on suspect

pasture and remove quickly if

symptoms develop.

Problem

Sheep consume perennial ryegrass plants

contaminated with a toxin producing

fungus, causing a staggery gait and

leading to productivity losses.

Outbreaks most common during late

summer and autumn months.

Signs and symptoms

• Signs develop slowly over days and

severity greatly varies.

• Mildly affected sheep show trembling

head, shoulder and flank muscles

after exercise.

• Moderately affected sheep stop with

muscle tremors, head shaking and

a staggery, uncoordinated gait after

being driven for 20-100 metres.

• Severely affected sheep will go down

with convulsions and acute muscle

spasms when disturbed.

Perennial ryegrass staggers

Perennial ryegrass

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

42

Diagnosis

• Based on a history of sheep grazing

rapidly growing phalaris pasture and

clinical signs.

Treatment

• No effective treatment for phalaris

poisoning.

Prevention

• Sheep yards - learn to recognise

rapidly growing phalaris and prevent

sheep from grazing on it.

• Access - remove sheep from affected

paddocks immediately and keep off

for two to three weeks (during the

fast-growing phase when plant is most

toxic).

Problem

Sheep consume new growth phalaris

which contains a toxin, causing heart

failure and sudden death.

Most commonly seen after the autumn

break.

Signs and symptoms

• Sudden death, often with convulsions,

within hours of sheep entering a

paddock of young phalaris.

• Affected sheep collapse on their side,

arching neck, paddling legs, champing

jaw, with dilated pupils and profuse

salivation.

Phalaris poisoning

Phalaris

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

43

Diagnosis

• Based on history of sheep grazing

phalaris pasture for prolonged periods

and clinical signs.

• On post mortem - by examining the

brain under microscope.

Treatment

• No effective treatment - affected sheep

should be culled from the mob.

Prevention

• Cobalt bullet - can be used to prevent

phalaris staggers by stimulating

production of toxin-fighting bacteria in

the rumen.

• Vitamin B12 injections - are ineffective

at preventing phalaris staggers.

• Pasture, crop and water supplements -

may not be effective, and may be more

costly.

Problem

Sheep graze phalaris pastures that are

cobalt deficient, causing difficulty eating

leading to significant weight loss.

Most sheep will survive but never fully

recover.

Signs and symptoms

• Affected sheep are uncoordinated with

head nodding, muscle tremors and a

stiff gait.

• If driven, sheep will go down with

convulsions but will get up and walk

away soon after.

• Some sheep can die while having

convulsions, others may die from

accidents caused by staggering.

Phalaris staggers

Phalaris

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

44

Diagnosis

• Based on examining affected sheep.

Treatment

• Identify cause - first step is to address

the underlying cause of the condition.

• Shelter - protect affected animals from

direct sunlight.

• Nursing - confine to shearing shed

while recovery takes place and provide

good quality hay.

• Medication - affected animals

may benefit from antibiotic, anti-

inflammatory or antihistamine

injections. Consult your veterinarian.

Prevention

• Grazing - avoid long term or repeated

grazing of pastures or stubbles

containing toxic plants such as potato

weed, which cause chronic liver

damage.

• Diet - allow access to hay or straw

when introducing sheep to immature,

lush, green pastures. If symptoms seen,

remove sheep immediately from this

pasture.

Problem

Photosensitisation is a symptom of

several diseases such as, liver damage

and plant toxicity. Sheep consume

immature forage causing Phylloerythrin

production that results in skin that is

overly sensitive to sunlight, impacting

wool quality and growth rates.

Most common in spring, on fast growing

lush pasture and sometimes associated

with aphid infestations. Cases can be

mild and recover quickly or severe,

resulting in death.

Signs and symptoms

• Early signs include restlessness,

seeking shade, shaking their head and

rubbing eyes and ears.

• Later signs range from mild to severe

sunburn, loss of appetite, jaundice

and death.

• Areas of skin not covered by fleece

are most affected, such as face, ears

and vulva.

• Fluid can build up under the skin

causing swelling of the face - swollen

eyelids with tears dribbling down the

cheeks and swollen ears may droop

and be covered in fine scabs.

Photosensitisation

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

45

Diagnosis

• Based on examining the eye

of affected sheep.

Treatment

• Most cases recover without treatment

in two to three weeks.

• Inspection - inspect eye for irritants

and remove if possible.

• Antibiotic spray or powder - two

doses are recommended, 48 hours

apart. Antibiotic spray or powder is

readily available.

• Antibiotic ointment and injections -

can be more effective than spray or

powder, especially in severe cases,

but must be used under veterinary

advice.

Prevention

• Yarding - avoid yarding sheep as

dust and flies can make the infection

spread through the mob.

• Flies - manage flies in yards if

possible.

Problem

A common and painful bacterial eye

infection that can cause blindness and

affect weight gain.

Sheep are most at risk when exposed

to hot and dusty conditions and flies.

Signs and symptoms

• Early signs include inflammation

of eye membranes and clear tears

running down the cheek.

• Cornea (clear eye surface) develops a

blue haze, becoming cloudy and white

over three to four days. Shallow ulcers

may develop on cornea.

• Disturbed vision - if the disease

spreads to both eyes, affected sheep

will become blind and begin to lose

weight.

• As the eye heals, blood vessels grow

onto the cornea making the eye

appear pink.

Pinkeye

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

46

Diagnosis

• Based on history and clinical signs.

• On post mortem - very dark and

consolidated lungs.

Treatment

• Antibiotics - treatment can aid

recovery. Contact your local

veterinarian.

Prevention

• Driving - drive sheep slowly and allow

sheep to walk slowly back to paddock

after yarding.

• Yarding - avoid overcrowding and

prolonged yarding. Avoid hot, dry and

dusty conditions. If unavoidable, work

early in the morning and hose yards to

reduce dust.

• Stress - avoid mixing mobs and sudden

diet changes. Provide shelter, good

nutrition, appropriate vaccinations,

drenching and supplements.

• Off label vaccination programs - cattle

vaccines can be useful in some cases -

consult your local veterinarian.

• Drenching - be careful not to lift a

sheep’s head too high and avoid plunge

dipping thirsty sheep.

Problem

Inflammation of the lungs, causing

breathing difficulties, leading to

productions losses and sometimes death.

Caused by bacteria and viruses in sheep

with compromised immunity (weaners are

most susceptible).

Most common during summer through

autumn, particularly in hot, dry and dusty

conditions.

Signs and symptoms

• Affected sheep may show signs of

cough, nasal discharge and lag behind

the mob.

• Mild cases can go unnoticed, but

growth rates are affected.

• A large proportion of the mob can

be affected with only a few deaths -

feedlot conditions will often see higher

number of deaths, very quickly.

• Signs may subside after four to six

weeks, but lasting adhesions in the

lungs and chest (pleurisy) are often

detected at the abattoir and trimmed

from the carcass.

Pneumonia

Scan QR code to learn

more on VR carcass

feedback tool

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

47

Diagnosis

• Based on clinical signs and response

to treatment in cases found early.

• On post mortem - by examining the

brain.

Treatment

• Supplementation - sheep respond

immediately to thiamine or vitamin B1

injections, available from most rural

stores or veterinarians. Some sheep

may require follow up treatment. Giving

thiamine powder orally in water solution

is also effective but slower.

• Humane destruction - sheep that are

down and do not respond to treatment

may have irreversible brain damage

and should be humanely euthanised

(see page 67).

Prevention

• Supplementation - thiamine powder

should be added to drinking water in

high-risk situations, or if cases occur.

Contact your local PIRSA Animal

Health office or veterinarian for advice.

Problem

A nervous disease of the brain, caused by

thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, resulting

in ear twitching, apparent blindness, star

gazing and sometimes, death.

May occur in sheep on a high grain diet

and diets including high thiaminases

plants (such as, bracken). Most common

in lambs in feedlots.

Signs and symptoms

• Early signs include listlessness and

loss of appetite. Sheep will separate

from the mob, appear blind and wander

aimlessly, stand still, or be found up

against a fence.

• Affected sheep will keep head lowered

to the ground or appear to be ‘star

gazing’ with a fixed stare into the sky

over the horizon, or have front legs

stretched out and head arched back.

• Severely affected sheep will go down

and if startled, start galloping leg

movements and have convulsions.

• If left untreated, sheep will get weaker,

sink into a coma and die quickly.

Polioencephalomalacia (PEM, star gazing disease)

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

48

Diagnosis

• Based on flock history, clinical signs

and eye fluid examination.

• On post mortem - liver will be pale

yellow, greasy and soft, carcass will

have plenty of fat, usually full-term twin

lambs inside.

Treatment

• Timing - treatment must be given as

soon as possible after initial signs to be

beneficial. Persistent and appropriate

treatment may save some ewes, but

success diminishes the longer they are

left untreated and recumbent. Consult

your veterinarian for treatment and

management of an outbreak.

• Glucose and hydration - treatment

can include glucose and rehydration

solutions, such as Vytrate and Ketol

(propylene glycol) administered orally

– readily available from most rural

stores. Repeated treatments may be

necessary.

• Humane destruction - if recumbent

ewes do not respond with three

hours of treatment, euthanasia is

recommended.

Problem

Very low blood sugar in ewes due to

inadequate energy in feed and high energy

demands of pregnancy, leading to lethargy,

weight loss and often death.

Most common during last six weeks of

pregnancy or immediately after lambing. If

energy requirements are not met by feed

intake, the ewe will break down her own

body tissues - a rapid breakdown of tissue

results in an accumulation of toxins.

Older ewes carrying multiples are most at

risk, particularly if overfat or feed intake is

suddenly interrupted in late pregnancy (e.g.

by yarding). Often combined with calcium

deficiency (hypocalcaemia) (see page 36).

Signs and symptoms

• In affected flocks, the disease usually

appears as a continuing outbreak over

two to three weeks.

• Early signs include dullness, loss of

appetite and lagging behind the mob

when driven.

• As the disease progresses, affected

ewes will stand alone, appear dopey and

not move when approached. If driven, will

appear blind, stumble and collapse.

• Eventually, affected ewes will become

comatose and die

Pregnancy toxaemia (twin lamb disease)

Prevention

• Diet - give pregnant ewes best paddock

feed available during month prior to

lambing. Provide supplementary feed

during last few weeks if needed (take

care if introducing grain, see page 64).

• Condition score - in flocks where multiple

births are expected, ewes should be

a minimum condition score 3, and no

more than condition score 4. Consider

scanning and segregating twins, singles

and empties for better feeding outcomes.

• Stress - minimise physical stress by

avoiding unnecessary mustering, yarding

or time off feed.

Difference between pregnancy

toxaemia and hypocalcaemia

Pregnancy

toxaemia

Hypocalcaemia

(milk fever)

Gradual onset Sudden onset

Sheep appear dull Sheep appear

alert but may

stagger or

convulse

Sheep are

unresponsive

when approached

Sheep move or

struggle when

approached

Death occurs

within 5-7 days

Death occurs

within 24 hours

Poor response

to treatment

Good response

to treatment

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

49

Diagnosis

• Based on a history of sudden death

while on a high-risk diet.

• On post mortem - by examining

intestine contents and isolating the

toxin brain and urine.

• Pulpy kidney is commonly assumed

cause of sudden death in sheep

where no investigation is conducted.

Unexplained sudden deaths can also

be caused by other diseases, including

anthrax (see page 14).

Treatment

• No effective treatment.

Prevention

• Vaccination - effective in preventing

pulpy kidney (see page 63). Vaccinate

sheep at least 10 days prior to heavy

grain feeding or introducing to a

feedlot. Vaccination can be effective in

the face of an outbreak.

• Diet - avoid sudden diet changes,

ensure grain is introduced correctly

(see page 64).

Problem

A clostridial (bacterial) disease that

mostly affect lambs grazing lush

feed, causing sheep to go down with

convulsions and leading to rapid death.

Can also occur in sheep of all ages,

especially if consuming grain.

Most common in flocks with an

inadequate vaccination program.

Signs and symptoms

• Affected sheep are usually found dead

due to rapid onset of the disease.

• Death can occur within hours of initial

signs - sheep will not survive longer

than 24 hours.

• Initial signs include dullness followed

by sheep going down with convulsions

and frothing at the mouth.

Pulpy kidney (enterotoxaemia)

Sheep Diseases | The Farmers’ Guide | 4th edition | November 2022

50

Diagnosis

• Based on a history of grazing the toxic

plants and clinical signs.

• On post mortem - in cases of chronic

copper poisoning, fat and skin of the

carcass will be severely jaundiced.

• On post mortem - in cases of chronic

ill-thrift and photosensitisation, the liver

will be darker and harder with blunt or

lumpy edges.

Treatment

• No effective treatment.

• Humane destruction - sheep that

survive a severe poisoning incident

will have irreversible liver damage