December 2022

Jail Charge Data Analysis and Jail Reduction Strategies for

Douglas County, Kansas

Bea Halbach-Singh, Sarah Minion, Jennifer Peirce, Sandhya Kajeepeta, Jason Q. Ng

and Jasmine Heiss

Table of Contents

– Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………2

– Background & data sources………………………………………………………………………………………4

– Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………………….5

– Glossary…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6

– Key findings……………………………………………………………………………………………………………7

1. Demographics of people admitted to jail…………………………………………………………7

2. Pretrial incarceration…………………………………………………………………………………..11

3. Jail admissions for court system failures and municipal charges…………………….24

4. Systemic issues driving multiple bookings into the jail…………………………………..33

5. Admissions for people serving county and state sentences……………………………..35

– Key takeaways and policy recommendations…………………………..……………………………….37

– Summary of recommendations by decision point…………………………..…………………………52

– Data collection & evaluation recommendations…………………………..……………………………56

– Appendix: methodology…………………………..…………………………………………………………….59

1

Executive Summary

Like many counties across the country, Douglas County, Kansas has experienced a dramatic

increase in its jail population over the past several decades, with the per capita jail incarceration

rate growing over 70 percent between 1990 and its peak in 2018. In response to concerns about

this continued growth, its costs to taxpayers, and its effect on the community, Douglas County

stakeholders sought the assistance of the Vera Institute of Justice (Vera) in analyzing the local

drivers of jail incarceration and developing strategies to reverse this trend and advance public

safety. Since 2019, Vera has used publicly available data to provide research and policy guidance

to various Douglas County stakeholders. For this report, Vera used data that is publicly available

from the Douglas County “Bookings and Offenses Dashboard” and from the Douglas County

Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC). The data in this report include people released

from the jail between January 1, 2017 - December 31, 2021 – just over 10,000 people in total.

Key Findings

● Most bookings into jail are for minor, nonviolent charges, including charges related to

substance use, supervision violations, and poverty.

● The Douglas County jail population is primarily driven by pretrial incarceration.

● Failures to appear (FTA), probation violations, remands and municipal charges are

significant drivers of the Douglas County jail population, together accounting for just

over half of all jail admissions and bed-days from 2017 to 2021.

○ FTAs were the most common top charge for overall admissions: they made up 21

percent of total admissions and accounted for 12 percent of bed-days. Overall, 40

percent of admissions in which FTA was the top charge were classified as traffic

cases from either municipal or district court–and in over a third of those cases,

the people jailed lived in another county.

○ Probation violations are the second-highest contributor to jail bed-days and the

fifth-most-common top charge.

○ Almost a third of admissions with only municipal charges were classified as

traffic cases.

● Overall, violent charges contributed to 21 percent of pretrial jail bookings.

○ Domestic violence (DV) charges represent a majority of admissions with a violent

top charge. 45 percent of admissions with a DV top charge were dismissed by a

judge or not filed by a prosecutor.

● The majority of admissions for drug-related charges were for drug possession rather

than drug manufacture or delivery, and a substantial portion were facing low-level

charges.

● DUI is a strong driver of pretrial jail admissions but has less of an impact on bed-days.

● About 40 percent of people were admitted two or more times; these individuals made up

70 percent of admissions and 78 percent of bed-days.

● Black people represent just 6 percent of the county population aged 15 or older, but 23

percent of jail bed-days and 18 percent of jail admissions.

2

Recommendations

● To alleviate jail bookings for low-level offenses, the county should standardize and

monitor implementation of alternatives to traditional arrest and booking, such as

citations in lieu of arrest, co-response and/or civilian response teams, and a review of the

municipal code.

● To reduce pretrial lengths of stay and a system where those who can afford bail are

released and those who cannot stay in jail, the courts should expand the use of

non-monetary conditions of release at the earliest point possible and eliminate the use of

a bail schedule. This may also mitigate some of the racially disparate impacts of

detention.

● To reduce the number of people who cycle in and out of jail on substance use charges, the

county should enact a public health approach that recognizes the reality of relapse and

takes an evidence-based harm reduction approach, investing in a range of necessary

services.

● To reduce the number of DUI admissions and lessen the rate of drunk driving in the

community, the county should expand accessible public transportation options and

divert first-time DUI arrests to a sobering center with referrals to services.

● To address high rates of incarceration for FTAs, the county should develop additional

court resources that help increase appearance and reduce bookings for nonappearance in

court by enabling officers to reschedule people with FTAs for new court dates on the spot

using either a mobile phone app or filling out a brief rescheduling form.

● To prevent the criminalization of poverty, the county should eliminate the use of

financial sanctions, eliminate incarceration as a response to non-payment, and conduct

indigency hearings at the earliest stage possible so that court debt may be waived.

● To preserve Due Process, the county should ensure all individuals in both municipal and

district court have access to adequate counsel at the earliest stage possible.

● To reduce the number of people booked on probation violations, the county should

prohibit incarceration for technical violations (e.g. a missed appointment, a positive

urinalysis, missed payment of fees, etc).

● To repair harm done to victims and hold individuals accountable, the county should

establish or expand a diversion policy that directs prosecutors to divert people to

community-based restorative justice programs when both parties agree to participate.

Implementation

There is immense opportunity for Douglas County agencies to expand on the COVID-era jail

population reductions by implementing some of the evidence-based reforms recommended in

this report. To manage implementation, the CJCC coordinator should lead individual working

groups that define parameters and track implementation over time for each commitment that

has generated alignment. These working groups should be composed of local government actors,

agency representatives, community members, and the senior data analyst.

3

Background & Data Sources

The Vera Institute of Justice (Vera) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research and policy

organization focusing on criminal legal system issues. Since 2019, Vera has used publicly

available data to provide research and policy guidance to various Douglas County stakeholders

on ways to reduce jail incarceration. In 2022, Vera presented preliminary analysis of county data

and policy recommendations on several occasions to the Racial Justice Working Group

Subcommittee of the Douglas County Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee (CJCC), as well

as to several system actors and community groups.

This memo presents findings from an analysis of data from Douglas County Correctional

Facility’s jail management system. Vera used data that is publicly available from the Douglas

County “Bookings and Offenses Dashboard” and from the Douglas County CJCC. The data in

this report include people released from the jail between January 1, 2017 - December 31, 2021 –

just over 10,000 people in total.

One limitation of the current jail bookings database, which underlies the dashboard, is

that it lists the charges noted in a person’s file at booking, but does not specify which charge is

the most serious and is thus likely the primary factor determining a person’s arrest, status in jail,

and subsequent trajectory in the system. This is often called the “top charge” or “controlling

charge,” based on the relative severity of the charges associated with each booking. Looking at

top charges separately from all charges that people in jail are facing can provide a clearer picture

of the behaviors and enforcement priorities that are contributing to jail admissions and lengths

of stay in jail. For example, less serious charges (like trespassing) may be among the most

common charges for people booked into the jail, but they are less frequently the most serious

charge on a booking. So, the “top charges” list is a subset of the overall charges list. This report

uses a methodology based on Kansas law and local practice to determine which charge is the

top/controlling charge in a booking with multiple charges. For further details on this method

please see the methodology appendix at the end of this memo.

A further limitation of the analysis is that the originating charge is not available in the

jail management system for people who were admitted for a number of charges that do not

typically, by themselves, constitute new criminal charges–including failures to appear,

probation and parole violations, bond failures, remands, and warrants or detainers. Throughout

this document, we refer to these types of charges as “administrative charges.” Generally, we

assumed that if one of these charges was accompanied by a new criminal, municipal or traffic

charge on a booking, that the new charge was driving the arrest rather than the administrative

charge. If the administrative charge was listed alone, or only accompanied by other

administrative charges, it was considered to be the most serious charge–and the person was

considered to be booked for an administrative charge alone. This limitation affects the top

charge classification in that, for people admitted on administrative charges, we are not able to

assess the severity of their originating charges–for example, to distinguish between someone

who was admitted for a failure to appear on a previous felony charge versus a previous traffic

charge. However, this limitation is somewhat mitigated by the fact that the booking with the

originating charge would presumably still be represented in the analysis the first time they were

booked.

4

Using the top charge analysis, this report focuses on the types of charges underlying both

jail admissions and longer stays. It also presents breakdowns of charge types and length of stay

by demographic traits (race, ethnicity, gender), legal status (pretrial, sentenced, probation or

parole violation), court type (district, municipal), case type (criminal, traffic, other) and other

categories. It provides deeper analysis of the charge types that show up most frequently as top

charges, such as failure to appear, violent charges, and driving under the influence, and on

several types of charges for which potential policy changes are within the purview of local actors,

such as municipal ordinance violations, probation violations, and drug possession.

This analysis is based on data about all people who were released from the Douglas

County jail during the five-year period from 2017 to 2021, meaning only bookings that have been

completed. By focusing on bookings for which both admission and release dates are known, we

ensure the analysis is based on complete information about length of stay and release reasons.

More information about the dataset, its limitations, and how the data was cleaned and prepared

for analysis can be found in the methodology appendix at the bottom of this report. The second

part of the report provides recommendations for future data collection and management (to

enable ongoing analysis along these lines) and for policy changes that could help to reduce the

use of the jail.

Acknowledgements

Vera is grateful to Dr. Matt Cravens, Senior Data Analyst for the CJCC, for providing the

data used in this analysis with permission from the Sheriff’s Office, and for his generosity in

answering questions about the jail management system. Vera would also like to thank the

Douglas County Racial and Ethnic Disparities Working Group for inviting us to participate in a

series of work sessions where many of the policies outlined in this memo were developed.

Specifically, we’d like to thank Pam Weigand, Chuck Epp, Jill Jolicoeur, Jolene Anderson,

LeRonda Roome, Gary Bunting, Tamara Cash, Shaye Downing, and Bryce Hirschman. We’d also

like to thank Sheriff Jay Armbrister, Chief Rick Lockhart, District Attorney Suzanne Valdez and

Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Josh Seiden, County Commissioner Shannon Portillo, County

Commissioner Shannon Reid, City Commissioner Amber Sellars, City Commissioner Bart

Littlejohn, City Commissioner Brad Finkeldei, Mayor Courtney Shipley, Craig Owens, Sam

Alison-Natale, Shannon Young, Municipal Prosecuting Attorney Beth Hafoka and Vicki Stanwix

for sitting down with us to talk about current practice and helping us better understand the

aspects of the system that data alone cannot capture. We’d also like to thank the members of the

Justice Matters Criminal Justice Reform Working Group for their tireless work to ensure efforts

to make Douglas County a safer and more just community continue moving forward.

5

Glossary of Key Terms

The following key terms are used frequently throughout this report:

Jail admissions: the number of individual bookings into jail within the time period covered by

this analysis.

Jail bed-day: each day that a person spends in jail, or a fraction of a day for people who are

released the same day as they are booked into jail. The number of bed-days is summed across all

the individuals that were booked into the jail during the time period covered by this analysis to

analyze which types of admission contribute to shorter/longer jail stays.

Judicial status: the court status of each charge on a booking at the time a person was admitted

to jail–for instance, “pretrial,” which means an individual is legally innocent and has not been

convicted or taken a plea, or “sentenced to county time,” which means an individual has either

been convicted of or plead guilty to the charge and are serving a custodial sentence in the jail.

Court type: whether each charge originated in district or municipal court. Douglas County has

one district court and three municipal courts—one each for Baldwin City, Eudora, and Lawrence.

District court is divided into 8 divisions that each handle different types of criminal, civil, and

juvenile cases, while the municipal courts primarily handle violations of city ordinances,

including parking and traffic violations.

Case type: whether the case was classified as criminal, traffic, or other, based on top charge.

Top charge: the most serious charge among the charges listed on a person’s booking (see the

methodology appendix for more details). Note that this represents the charge listed at booking,

which may differ from what a person is ultimately charged with by the District Attorney and

potentially convicted of.

6

Key Findings

1. Demographics of people admitted to jail

People were released from the Douglas County jail over 21,000 times from 2017 to

2021.

1

This number represents 10,376 unique individuals–some of whom were sent to jail

multiple times. Of those, at least 6,264 individuals (60 percent) were Douglas County residents

at the time of their arrest.

2

Excluding the college-age population, police booked 1 out of 11

Douglas County residents aged 25 to 54 (prime working age) between 2017 and 2021.

3

Almost 1

in 3 prime-working-age Black men, and almost 1 in 6 prime-working-age Latino men, were

booked into jail.

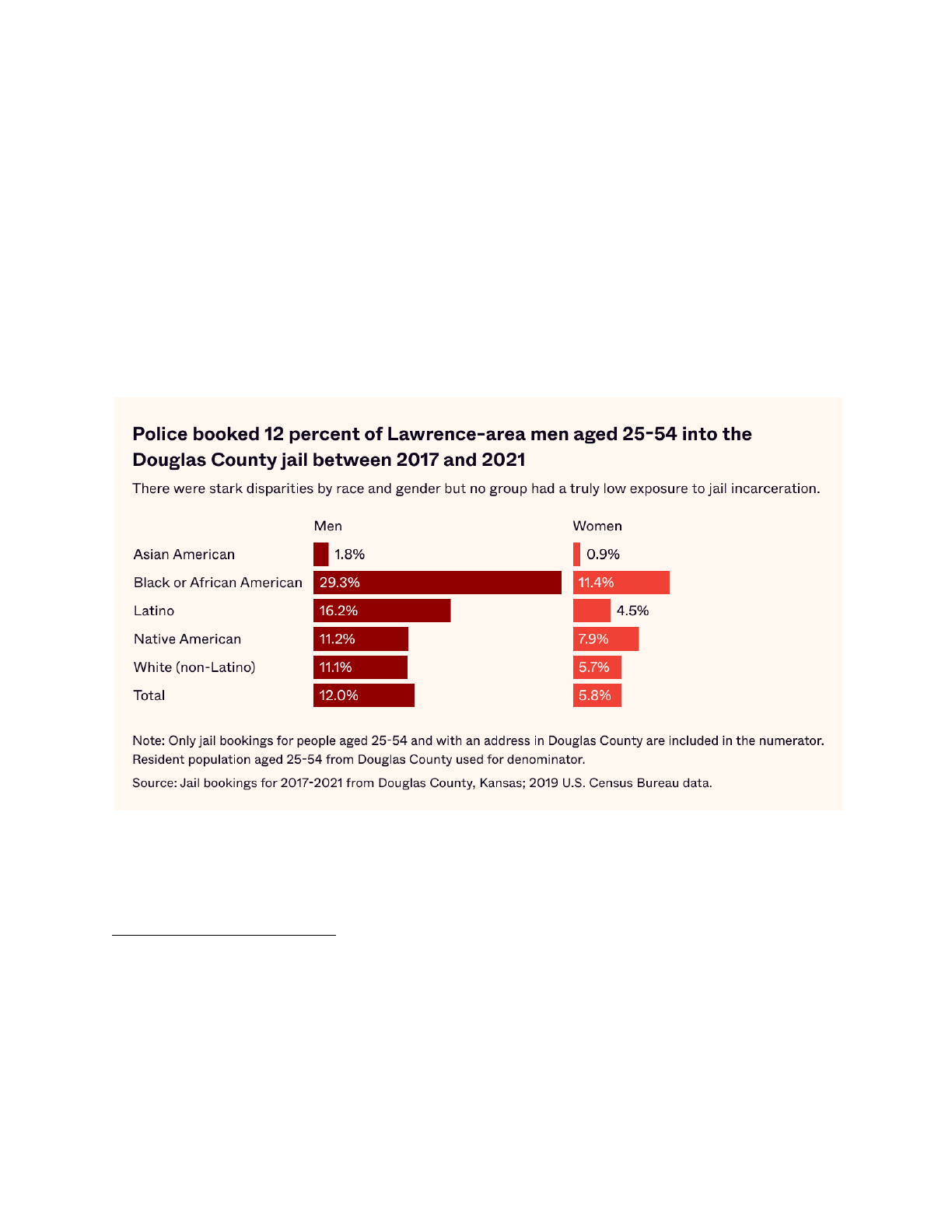

Figure 1

White people made up the majority of jail admissions and jail-bed days, which reflects the

demographic makeup of the resident population in Douglas County. However, as shown in

Figure 2, Black people represent just 6 percent of the county population aged 15 or

older, but 23 percent of jail bed-days and 18 percent of jail admissions. The

3

To account for the fact that Douglas County is home to the University of Kansas and many students have

a shorter residency period, the college-age population is excluded from these statistics, which use county

residents aged 25 to 54 as the denominator. Percentage of Douglas county population is based on data

from the U.S. Census Bureau Annual County and Resident Population Estimates by Age, Sex, Race, and

Hispanic Origin: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019. See United States Census Bureau, County Population by

Characteristics: 2010-2019 (Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau, 2021).

2

This count excludes 302 people who had missing info for residence and who are most likely homeless

people in Douglas County.

1

The dataset is based on a cohort of people who were released during 2017-2021, some of who may have

been admitted prior to 2017.

7

disparities in jail admissions suggest that law enforcement officers are more heavily policing

and/or more frequently deciding to make arrests when interacting with Black people relative to

the general population.

4

Figure 2

The fact that the disparities are even sharper for the proportion of bed-days than the proportion

of admissions indicates that Black people are staying in jail longer than white people. This could

be the result of money bail being set more frequently, higher bail amounts and/or greater

difficulty affording money bail. Black people could also be spending more time in jail on

supervision revocations or serving longer sentences.

5

The data also suggests that Latino and

5

Several studies have found that people of color are treated more harshly than white people at each stage

during the pretrial process, beginning with the initial release decision, followed by the decision to set

financial or non-financial conditions, and then if financial conditions are set, in the bail amount. These

biases result in a 10-25 percent higher likelihood of pretrial detention for Black and Latinx people than

white, and higher median bond amounts. Controlling for other factors, a Black person accused of a crime

is more likely to have bail set, and on average, it is set in an amount $10,000 or higher than that of a white

person. See Wendy Sawyer, “How race impacts who is detained pretrial,” Prison Policy Initiative, October

9, 2019, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/10/09/pretrial_race/; and one study found that Black

people accused of drug offenses were 80 percent less likely to receive a recognizance bond than white

4

Studies show that racial disparities in the criminal legal system begin at the first point of officer

interaction. “Pretextual stops,” or a stop that an officer makes for one reason (e.g. broken tail light) during

which they look for evidence of additional crimes (e.g. possession of a controlled substance), are a key

driver of inequity. See Vera Institute of Justice, Motion for Justice, accessed October, 2022

https://motionforjustice.vera.org/.

8

Native American people are disproportionately admitted to the jail compared to the resident

population. However, common misclassification and smaller numbers make it more difficult to

accurately measure disparities for these groups of people, as well as for people who identify with

multiple races and ethnicities.

6

Women made up 27 percent of admissions to the jail from 2017 to 2021. From 2000

to 2019, the women’s incarceration rate in Douglas County almost tripled, from 29 to 84 women

in jail for every 100,000 working-age residents.

7

Most women were admitted to jail for low-level,

nonviolent offenses: 35 percent of women’s admissions from 2017 to 2021 had an administrative

charge as the top charge, and 27 percent had a nonperson, nonviolent misdemeanor as the top

charge.

8

Nationally, women detained on unaffordable bail pretrial have a median annual income

of $11,071, making even comparatively “low” bond amounts just as out of reach as higher

bonds.

9

Many women held on bail are the primary caregivers of minor children, which can

create additional pressure to take a guilty plea just to be released from jail in order to care for

their families.

10

Douglas county residents aged 25 to 54 (the prime working-age population) made

up 71 percent of jail admissions and 78 percent of jail bed-days. The fact that

working-age people make up such a large portion of the local jail population raises questions

about how local incarceration may be creating barriers to employment and economic mobility

and further exacerbating existing racial disparities in income and economic outcomes. Pretrial

detention has been shown to have negative impacts on labor market outcomes, including a

decreased likelihood of formal sector employment and increased likelihood of receiving

10

Although recent national data on this subject is not available, a study using data from a 2002 Survey of

Inmates in Local Jails conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that ⅔ of women who were

unable to meet bail conditions were mothers of minor children. For a discussion of this analysis see

Wendy Sawyer, How does unaffordable money bail affect families? (Northampton, MA: Prison Policy

Initiative, 2018).

9

Bernadette Rabuy and Daniel Kopf, Detaining the Poor: How money bail perpetuates an endless cycle

of poverty and jail time (Northampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative, 2016).

8

Administrative charges are those that do not typically, by themselves, constitute new criminal charges.

The most frequently recorded charges in this category were failure to appear and violations of probation

and parole. Generally, we assumed that unless an administrative charge was accompanied by a new

criminal or municipal charge, it was a technical violation such as missing a meeting with a probation

officer, a positive drug test, or non-payment of court fines and fees. However, it is possible that a person’s

supervision would be revoked after being charged with a new offense, but the offense may not be filed

until later, which would make it appear like a technical violation in the data. In other cases, a person

might be arrested on a new charge that the prosecutor later decides not to file.In some cases, this might be

because the person would spend roughly the same amount of time incarcerated on a technical violation,

but the prosecutor would not need to prove the violation beyond a reasonable doubt.

7

Vera Institute of Justice, Incarceration Trends, accessed December 2021,

https://trends.vera.org/state/KS/county/douglas_county.

6

For a comparison of how Hispanic people are represented in criminal justice data across U.S. states, see

Sarah Eppler-Epstein, Annie Gurvis, and Ryan King, The Alarming Lack of Data on Latinos in the

Criminal Justice System, (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, December 2016).

people. See Tina L. Freiburger, Catherine D. Marcum and Mari Pierce, “The Impact of Race on the Pretrial

Decision,” American Journal of Criminal Justice 35, no. 1: 76-86.

9

employment- and tax-related government benefits compared to people in similar circumstances

who are initially released.

11

Douglas County residents between the ages of 18 to 24 made up 23 percent of

admissions and 15 percent of bed-days.

12

Lawrence is home to the University of Kansas, a

campus with an enrollment of 22,500 students in Fall 2021.

13

Students represent a large share of

the county population, although not all the people in the 18-24 age group are attending the

university. When arrested, most people in this age group were booked for low-level, nonviolent

charges: 31 percent of admissions for this age group from 2017 to 2021 had a nonviolent

misdemeanor as the top charge (primarily driving under the influence), and 28 percent had an

administrative charge as the top charge (most commonly failure to appear).

Figure 3

13

We looked at enrollment data by physical campus, see The University of Kansas - Analytics,

Institutional Research & Effectiveness, “Enrollment Dashboard: Fall Enrollment,”

https://aire.ku.edu/enrollment.

12

Numbers differ from those presented in figure 3, which presents admissions and bed-days for groups

that match age groupings provided in the U.S. Census Bureau data.

11

Will Dobbie, Jacob Goldin, and Crystal S. Yang, “The Effects of Pretrial Detention on Conviction, Future

Crime, and Employment: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Judges,” American Economic Review 108

no. 2 (2018): 201-40.

10

2. Pretrial incarceration

The Douglas County jail population is primarily driven by pretrial incarceration.

Pretrial admissions (including for pending charges and for charges not ultimately filed)

accounted for 74 percent of admissions and 44 percent of bed-days, the largest portion of total

bed days.

14

Figure 4

14

Charges with a status of “pending referral to prosecutor” and “charge not filed by prosecutor” are also

considered to be pretrial in this analysis. According to discussions with an employee in the Douglas

County Sheriff’s Office conducted in Spring 2022, when a person is arrested on a new charge, the charge is

initially labeled in the jail management system as “pending referral to prosecutor.” The status is later

changed to “pretrial” if the prosecutor decides to pursue the charge, or “charge not filed by prosecutor” if

not. 54.2 percent of charges were labeled pretrial, 14.8 percent were pending referral, and 5.4 percent

were not filed by the prosecutor.

11

What is driving pretrial jail admissions?

The majority of people admitted to the jail pretrial (79 percent) had a nonviolent top charge, and

73 percent were facing a misdemeanor or failure to appear top charge.

15

Figure 5 shows the

breakdown of pretrial admissions and bed-days by charge class. Although felony charges only

made up 21 percent of pretrial admissions, they accounted for 62 percent of bed-days. By

comparison, misdemeanors accounted for a far greater share of pretrial admissions (49 percent)

and only 17 percent of bed-days. This finding is not surprising, given that people who are facing

more serious charges tend to have higher bail amounts set and stay in jail longer, whereas

people facing less serious charges might be able to come up with bail more quickly. Research

from other places has shown that despite decreasing admissions, increasing lengths of stay have

kept jail populations high, and a small number of people tend to account for the greatest portion

of bed-days.

16

A comprehensive strategy to reduce jail populations must include strategies to

both reduce jail admissions and address long lengths of stay.

Figure 5

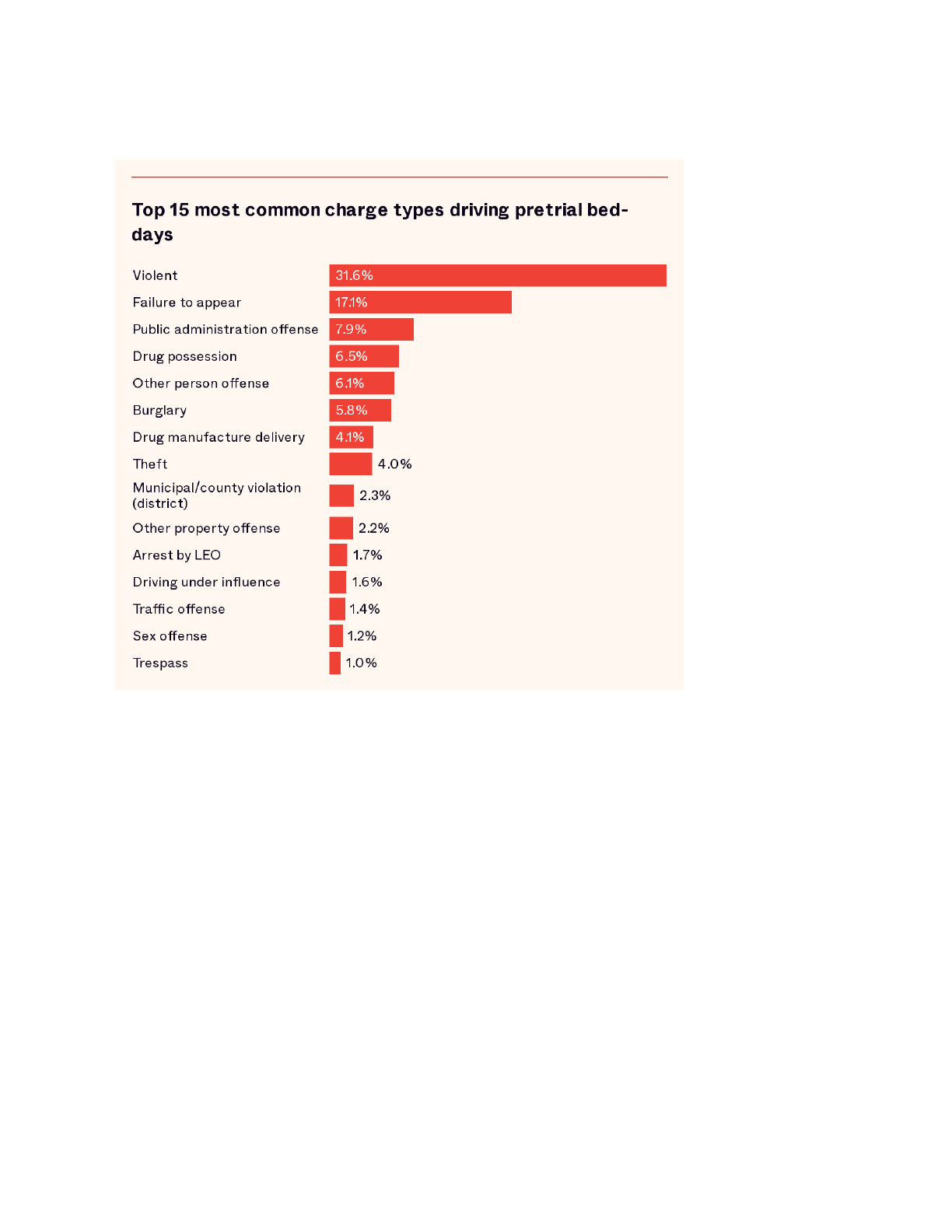

Figure 6 shows the top 15 most common charges driving pretrial admissions into the jail.

Together, failures to appear (FTAs), public administration charges (a group of charges related to

tampering or interfering with the work of government officers, including law enforcement and

corrections staff), drug possession, theft, other property offenses, trespass, and traffic offenses

(excluding vehicular homicide) made up almost half (47 percent) of pretrial jail admissions.

16

See Jake Horowitz and Tracy Velázquez, Why Hasn’t the Number of People in U.S. Jails Dropped,

(Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, March 27, 2020); and Melanie Close, Olive Lu, Shannon

Tomascak, Preeti Chauhan, Erica Bond, Understanding Trends in Jail Populations, 2014-2019: A

Multi-Site Analysis, (Data Collaborative for Justice at John Jay College, December 2021).

15

In this analysis, charges are categorized as “violent” when they involve force or threat of force resulting

in bodily injury or death, a definition that is based on the FBI’s definition of violent crime under the

Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program. This includes charges such as murder and non-negligient

manslaughter, rape, robbery, assault, battery, and kidnapping. Involuntary manslaughter and vehicular

homicide are categorized separately under “other person offenses.”

12

Figure 6

Top charge type #1: Failure to appear

Almost a quarter of pretrial jail admissions were due solely to failure to appear for a court

hearing (FTA). See section 2 of this report for more detailed information about FTA bookings.

Top charge type #2: Violent charges

Violent top charges made up 21 percent of pretrial admissions and 32 percent of pretrial

bed-days. Within the category of pretrial admissions with a violent top charge, 65 percent of

pretrial admissions were for domestic violence charges for which arrest is mandatory in

Kansas.

17

Looking specifically at pretrial admissions, domestic violence charges accounted for 61

percent of the top charges classified as violent on which men are booked into jail and 72 percent

of the top charges classified as violent on which women are booked into jail. Notably, 45 percent

of the total number of people booked into jail and 46 percent of the people booked pretrial with

a domestic violence top charge were ultimately released due to the charge(s) being dismissed.

18

Research suggests that while mandatory arrest policies are meant to protect survivors of

domestic violence, they can have unintended negative consequences, including higher arrest

18

For men, 38 percent of domestic battery admissions were dismissed, and for women, 59 percent of

domestic battery admissions were dismissed.

17

This may be an undercount of overall domestic violence-related charges, since the data may not always

note whether or not a violent charge was domestic in nature. See KS Stat § 22-2307 (2021).

13

rates for survivors of domestic violence, unwanted involvement of child protective services, and

increased risk of retaliation.

19

After domestic violence charges, the next six most common types of charges classified as violent

were misdemeanor battery (7 percent of violent pretrial admissions), felony aggravated battery

(7 percent), felony aggravated assault (7 percent), misdemeanor battery on a law enforcement

officer (3 percent), misdemeanor assault (2 percent), and felony aggravated robbery (1 percent).

As shown in figure 7, people charged with misdemeanor battery or misdemeanor assault charges

were released on their own recognizance more than half of the time. Misdemeanor assault and

felony aggravated assault charges were the most likely to be dismissed or not filed–33 and 20

percent of the time, respectively.

Figure 7

Top charge type #3: DUI charges

Driving under the influence (DUI) as a top charge made up 19 percent of pretrial admissions but

less than 2 percent of pretrial bed-days. DUI charges–91 percent of which were

misdemeanors–also require arrest in Kansas.

20

However, the median length of stay for people

admitted pretrial on DUI charges was less than one day. People with multiple DUI convictions

and/or a habitual violator charge may be an exception; these “enhanced DUI” cases make up

only 17 percent of DUI-related pretrial bookings but account for 69 percent of DUI-related

pretrial bed-days. DUI convictions also have mandatory jail stays, with penalties ranging from

48 hours to 6 months upon a first conviction up to 90 days to a year for a fourth or subsequent

conviction.

21

Habitual violator convictions, which occur when people have been convicted of a

21

KS Stat § 8-1567 (2021).

20

KS Stat § 8-2104 (2021).

19

Victoria Frye, Mary Haviland, and Valli Rajah, “Dual Arrest and Other Unintended Consequences of

Mandatory Arrest in New York City: A Brief Report,” Journal of Family Violence 22, no. 6 (2007),

397-405; and Mimi E. Kim, “From Carceral Feminism to Transformative Justice: Women of-Color

Feminism and Alternatives to Incarceration,” Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work 27,

no. 3 (2018), 1-15.

14

number of motor vehicle-related charges three or more times in the last five years, also come

with a 90-day minimum mandatory jail penalty.

22

While DUI charges may not be a significant

driver of pretrial bed-days, the high number of DUI admissions likely account for a substantial

amount of law enforcement time processing arrests, bookings, and releases. In addition, people

between the ages of 18 and 25 accounted for a disproportionate 37 percent of admissions with a

DUI top charge, compared to 28 percent of admissions due to all other charges.

Top charge type #4: Public administration charges

Public administration charges are a group of charges related to tampering or interfering with the

work of government officers, including law enforcement and corrections staff. The most

common top charge within this group was misdemeanor “interference with law enforcement

officer” (40 percent of pretrial public administration charges), a charge that most commonly

refers to obstructing or resisting arrest in the data, but can also be more serious allegations such

as tampering with evidence or making a false report. Misdemeanor violation of a protective

order made up 29 percent of pretrial admissions where a public administration charge was the

top charge. Other types of charges in this category include (but are not limited to) unlawful

tampering with electronic monitoring equipment, intimidation of a witness/victim, and

violating the offender registration act.

Top charge type #5: Drug possession charges

This category refers to simple drug possession charges, excluding any drug possession charges

that include an intent to sell or distribute (which are included in the category “drug

manufacture/delivery”). Admissions where a drug possession charge was the top charge made

up 5 percent of pretrial admissions and 7 percent of pretrial bed-days. More than half of pretrial

drug possession admissions (53 percent) were for possession of an opiate, opium, narcotic or

stimulant, which is a felony charge in Kansas.

23

Of the pretrial admissions where drug

possession was the top charge, 40 percent were for misdemeanors—primarily possession of a

hallucinogenic drug, followed by drug paraphernalia charges.

Top charge type #6: Theft

Admissions where a theft-related charge was the top charge accounted for 4 percent of pretrial

admissions and 4 percent of pretrial bed-days. Almost half (43 percent) of pretrial theft

admissions were for misdemeanor charges that are likely to be related to poverty–the majority

for theft of property or services worth less than $1,500, followed by criminal use of a financial

card of less than $1,000 and criminal deprivation of property.

24

Of the pretrial theft admissions

where the top charge was a felony, 10 percent were for identity theft, a level 8 nonperson felony

in Kansas except in cases where the monetary loss is greater than $100,000.

25

Overall, 44

percent of pretrial theft admissions had a level 9 nonperson felony as the top charge–the least

severe type of felony related to theft–but the specific details of these charges are unclear from

the data. Based on Kansas statute, these charges could be one of three types of theft of property

25

KS Stat § 21-6107 (2021).

24

KS Stat § 21-5801 (2021) for theft of property or services; KS Stat §21-5828 (2021) for criminal use of a

financial card; and KS Stat § 21-5803 (2021) for criminal deprivation of property.

23

KS Stat § 21-5706 (2021).

22

KS Stat § 8-286 (2021); and KS Stat § 8-287 (2021).

15

or services that are classified as level 9 nonperson felonies in Kansas: (1) theft of property or

services between $1,500 and $25,000; (2) theft of property worth less than $1,500 from three

separate establishments within a period of 72 hours; and (3) theft of property worth between

$50 and $1,500 committed by a person with at least two prior theft convictions in the previous

five years.

Top charge type #7: Other property charges

The group “other property offenses” primarily includes criminal property damage charges.

Within people admitted pretrial with criminal property damage as a top charge, 74 percent were

misdemeanors and 24 percent were felonies.

What is driving pretrial bed-days?

In addition to pretrial admissions, we also look at pretrial bed-days–that is, the sum of days

spent in jail across persons admitted pretrial–to understand not just which types of charges are

contributing the greatest number of admissions, but which types of charges are responsible for

both high admissions and long jail stays, and thus impacting the size of the jail.

Figure 7 shows the top 15 most common charges driving pretrial bed-days. Compared to the

types of charges that drive pretrial admissions, violent charges, burglary charges, drug

manufacture and delivery charges, other person offenses, and sex offenses are stronger drivers

of pretrial bed-days. This is expected, as there are fewer people admitted to jail on these more

serious charges, but they spend longer in jail, likely either because they have been remanded

without bail, or are unable to pay the higher monetary bail amount set on more serious felony

cases. While the top or controlling charge is generally thought of as the charge that is keeping

someone in jail, there may also be cases in which someone is pending trial on a charge and

would be released–save for a probation violation related to another charge that is keeping them

in jail pending a hearing. During the time period covered by this analysis, people in this

situation were not eligible to be released, even if their bond was paid; however, according to the

CJCC, people with probation violations were made eligible for pretrial release with pretrial

services in March, 2022. Additional analysis should be undertaken to see whether people

charged with probation violations are being released more quickly and/or at higher rates as a

result of this policy change.

16

Figure 7

FTA as a top charge accounted for almost one in five pretrial bed-days (17 percent). This is due

to the high number of admissions for these charges, rather than longer jail stays. The median

length of stay is 0.8 days for people admitted pretrial with FTA as a top charge. Unfortunately,

the absence of an originating charge in the jail management system does not allow us to identify

the portion of admissions with FTA as a top charge that have a serious or violent felony

originating charge. Nevertheless, the high volume of short jail stays for these types of charges

raises serious questions about the public safety rationale of booking people into jail–especially

given that better alternatives exist to ensure peoples’ appearance at court. It is also impossible to

distinguish between failures to appear that reflect intentional efforts to evade justice as opposed

to missed court dates that stem from conflicts, challenges, forgetting, or a misunderstanding of

the judicial process. As discussed further in Section 3, available evidence suggests that the

majority of FTA charges are in the latter category. If most or all bookings in this category were to

be eliminated, the county would likely realize cost savings, reduce jail staff administrative time

spent processing bookings and releases, and prevent the unnecessary trauma and destabilization

people experience in jails.

Admissions where a public administration charge was a top charge accounted for 8 percent of

pretrial bed-days–again, mainly due to the high number of admissions for these charges, rather

17

than long jail stays. The median length of stay was less than 1 day for people admitted pretrial

with this top charge.

Admissions where a simple drug possession charge was the top charge accounted for 7 percent

of pretrial bed-days, and admissions where a drug manufacture or delivery charge was the top

charge accounted for 4 percent of pretrial bed-days. Similar to FTAs and public administration

charges, these charges factor in the top 10 types of charges driving pretrial bed-days due to the

high number of admissions for these charges, rather than long lengths of stay. The median

length of stay is 0.4 days (almost half a day) for people admitted pretrial on simple drug

possession charges and 0.8 days for those admitted pretrial on drug manufacture or delivery

charges. Again, this raises questions about opportunities to avoid jail bookings altogether,

particularly given the well-documented negative consequences of incarceration for people who

use drugs.

The category “other person offense” includes charges that are classified as person crimes in the

Kansas sentencing guidelines, but are not included in the list of violent charges or other

categories delineated in this report. Person charges generally refer to offenses that inflict, or

could inflict, harm to another person. People charged with other person offenses made up 2

percent of pretrial admissions and 6 percent of pretrial bed-days. The majority (78 percent) of

pretrial admissions for other person offenses were for attempted or actual criminal threat, for

which the median pretrial length of stay was 1.5 days.

Admissions where burglary was the top charge accounted for less than 2 percent of pretrial

admissions and 6 percent of pretrial bed-days. The median pretrial length of stay for people

admitted on burglary charges was 2.5 days, and 3.5 days for aggravated burglary cases.

The category “municipal/county violation” is used as an “other” category when officers don’t

know or didn’t list the charge on a booking. This charge has been less frequently used in more

recent years.

The category “other property offense” includes charges that are classified as property crimes in

the Kansas sentencing guidelines, but that fall outside of the other categories. The majority (88

percent) of pretrial admissions in this category were for criminal damage to property, for which

the median pretrial length of stay was 0.1 days.

Pretrial admissions resulting from arrest warrants (denoted as “Arrest by LEO”) accounted for 2

percent of pretrial bed-days and 1 percent of pretrial admissions.

26

People admitted to jail

pretrial with an arrest warrant as the top charge had a relatively high median length of stay–8.7

days. The lack of originating charge in the data means we do not know what these warrants were

for; however, for the majority of these cases, the warrant is likely an outstanding warrant for a

past action or missed hearing. Out of a total of 478 pretrial admissions in which the person

booked into jail had a warrant listed one or more times on the booking, 30 percent had no other

type of charge listed, and 21 percent were only accompanied by an administrative charge. In 13

26

The relevant statute for this charge states that it can occur when there is a warrant out for a person’s

arrest or when an officer has probable cause to believe that a person is committing or has committed a

crime; however, in all instances where this charge appears in the dataset, the charge is denoted as a

warrant arrest, either local or for another state or jurisdiction. See KS Stat § 22-2401 (2021).

18

percent of pretrial admissions with an arrest warrant, the warrant was only accompanied by a

misdemeanor or unknown charge and no felony–most commonly domestic battery, driving

while suspended, DUI and interference with a law enforcement officer (which includes resisting

or obstructing arrest). In 36 percent of pretrial admissions with an arrest warrant, the warrant

was accompanied by one or more felony charges–most commonly interference with a law

enforcement officer, followed by possession of stolen property and drug paraphernalia charges.

Whether or not an arrest was made pursuant to a warrant may not be uniformly or reliably

recorded in the jail management system, given the relatively small number of admissions and

lack of overlap with, for example, FTA bookings. Instead, it is likely that this is only recorded in

a subset of situations.

How long did people being held pretrial stay in jail?

The majority of people admitted pretrial (64 percent) were booked and released within 24

hours, and the median length of stay overall for people held pretrial was half a day. However,

Black and Native American people were less likely than white people, Latino people, or people of

Asian descent to be released the same day, and more likely to have longer pretrial lengths of

stay. Figure 8 shows pretrial lengths of stay by race/ethnic group. Fifty-seven percent of Black

people and 60 percent of Native American people were released the same day they were booked,

compared to 65 percent of white people, 71 percent of Latino people, and 73 percent of Asian

people. Black people were more likely to be held pretrial for at least one week than people of any

other race or ethnicity.

27

Figure 8

27

This does not control for the severity of the charges, though it is well-documented that Black people are

treated more harshly at every stage of the criminal legal system.

19

What is driving pretrial releases?

Given the well-documented harms of pretrial detention for individuals and their families, we

look at the release reasons for people who were held pretrial in order to better understand how

frequently people are able to avoid lengthy pretrial detention by paying cash or surety bonds

versus by being released without any financial conditions, and how this differs based on peoples’

most serious charge. Looking at release reasons also gives us insight into how frequently people

are released because the charge or charges against them are dismissed by a judge or not filed by

a prosecutor.

Figure 9 shows release reasons and median length of stay for people who were admitted pretrial.

Of the total number of people admitted pretrial, 38 percent were released on their own

recognizance (OR) and 30 percent were released after they or someone else paid a cash or surety

bond.

28

In 13 percent of pretrial admissions, people were released because the charge or charges

against them were dismissed or not filed. Notably, 36 percent of pretrial admissions with a

violent top charge–primarily misdemeanor domestic battery charges–were dismissed by a judge

or not filed by the prosecutor. Violent charges were the most likely category of charges to be

dismissed or not filed in the dataset. Other types of charges that are commonly dismissed or not

filed in pretrial cases include child endangerment, burglary, arson, theft or possession of stolen

property, and criminal threat.

Figure 9

28

Release on one’s own recognizance, or OR, is a court decision to allow a person charged with a crime to

remain out of custody while they await their trial. In Kansas, OR release is sometimes given without

conditions or collateral, and sometimes involves a cash deposit of 10 percent of the bond amount.

Cash bonds require an individual to pay the court the full amount of a person’s bail in cash to secure

pretrial release, while surety bonds involve paying 10 percent or more of the bond amount plus fees to a

bail bond company.

20

A small number of people (260 pretrial bookings or about 2 percent of pretrial admissions) were

admitted to jail pretrial and then released for “time served.” This category is likely made up of

people who were held on unaffordable bond and pleaded to time served. More than half of

admissions in this category were people held pretrial on an FTA top charge with a median length

of stay of 10 days.

Figure 10 shows the percentage of pretrial bookings by release reason for charges grouped by

severity. People who were booked pretrial on an FTA top charge were the most likely to be

released with cash, surety, or credit card bond, followed by those with nonperson, nonviolent

felonies.

29

This may reflect a belief that posting monetary bond compels future court appearance

or reflect the assignment of a risk level based on previous non-appearance. All available

evidence shows, however, that non-monetary conditions of release are just as effective in

ensuring court appearance, and that pretrial detention prior to posting a bond can actually

reduce appearance rates.

30

People booked pretrial on an FTA top charge were also the most

likely to be released on “judge’s authority”–likely because such a large share of people booked on

FTAs have municipal court FTAs. A person can be released at a judge’s discretion in a range of

situations, such as if the judge eliminates a person’s bond. This might be analogous to being

released on one’s recognizance, but is recorded differently.

Overall, violent charges were the most frequent to be dismissed or not filed. Almost 70 percent

of admissions for nonperson, nonviolent misdemeanors were released on their own

recognizance.

30

Michael R. Jones, Unsecured Bonds: The As Effective and Most Efficient Pretrial Release Option

(Washington, DC: Pretrial Justice Institute, 2013); and Christopher Lowenkamp, Marie VanNostrand,

and Alexander Holsinger, The Hidden Costs of Pretrial Detention (Houston, TX: Laura and John Arnold

Foundation, 2013).

29

Kansas is a “right to bail” state, meaning that anyone arrested on a non-capital offense is entitled to the

right to freedom pending trial, and that any bond amount that is higher than necessary to ensure that the

individual does not evade justice nor pose a threat to public safety is considered excessive.

21

Figure 10

Taking a closer look at people who were released with cash, surety or credit card bonds, figure 11

groups these admissions by severity and type of charge. Approximately three quarters of those

released with cash or surety bond had a misdemeanor or FTA as their most severe charge. Over

a quarter of these individuals were admitted for nonperson, nonviolent misdemeanor charges.

The most common of these charges was DUI (16 percent). Other types of nonviolent

misdemeanor charges frequently released with financial bond include criminal damage to

property, driving on a suspended license, violating a protection order, interference with a law

enforcement officer, and drug possession charges.

22

Figure 11

23

3. Jail admissions for court system failures and municipal charges

Failures to appear, probation violations, remands and municipal charges are

significant drivers of the Douglas County jail population, together accounting for

just over half of all jail admissions and bed-days from 2017 to 2021.

31

Figure 12 shows

the portion of total admissions for failures to appear, probation violations, and remands

compared to admissions for all other charges from 2017 to 2021. More details about how failures

to appear, probation violations, and remands figure in municipal court charges is provided in

the later section “Admissions where a municipal charge is the sole or top charge.”

Figure 12

In recent years, efforts to reduce the Douglas County jail population have had some impact on

reducing admissions for FTA, probation violations and municipal charges, indicating

momentum toward continued reforms. Annual jail admissions declined by almost half from

2017 to 2020, from 5,297 to 2,838, before increasing again to 3,230 in 2021. Almost 20 percent

of that drop occurred from 2017 to 2019, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, during

which time the court system, district attorney’s office and sheriff’s office adopted protocols to

31

Municipal charges are defined as those originating from Douglas County’s three municipal courts - one

each for Baldwin City, Eudora, and Lawrence, including failures to appear, probation violations, and

remands originating from municipal court.

24

reduce the jail population.

32

From 2017 to 2021, FTAs as a portion of total admissions declined

from 23 to 17 percent, probation violations declined from 7 to 6 percent of total admissions, and

municipal charges declined from 35 to 28 percent of admissions. Remands increased from 2 to 8

percent of admissions.

Failures to appear

FTAs were the most common top charge for overall admissions: they made up 21

percent of total admissions and accounted for 12 percent of bed-days. They were also

the most common top charge for pretrial admissions, and for admissions from municipal court.

Although FTA top charges as a portion of overall admissions declined slightly from 2017 to 2021,

the median length of stay for FTA admissions doubled from less than 1 day to almost 2 days.

Of the admissions with FTA as top charge, 45 percent were released on cash or surety bond; only

17 percent were released on their own recognizance, and another 14 percent were released on

“judge’s authority.”

33

About half were released the same day, and half were released after having

been in jail for 24 hours or more–staying in jail a median of 5 days. It is notable that a large

portion of people are facing jail stays and posting money bail to secure their release for a missed

court appearance–a charge with a number of effective alternative responses.

34

Even people

booked into jail and released on the same day generate costs associated with the intake and

release process, can strain limited jail resources and contribute to capacity challenges.

Overall, 31 percent of all admissions from 2017 to 2021 had one or more FTAs among the

charges listed on the booking. Figure 13 shows the most common types of accompanying charges

for admissions where one or more FTAs were present on booking. Among these admissions,

FTAs were the only type of charge on the booking 65 percent of the time. In 15 percent of cases,

FTAs were accompanied by at least one felony-level charge. In 10 percent of cases, FTAs were

accompanied only by misdemeanor-level or unknown charges and no felony charge, and in 9

percent of cases, FTAs were accompanied only by a probation violation, remand or arrest

warrant and no other charges. Issuing and strictly enforcing warrants for people who miss court

appearances is often justified as the only way to manage court dockets. Evidence shows,

however, that most people do not fail to appear in court because they are willfully evading

prosecution, but because they are facing barriers such as a lack of transportation, childcare or an

inability to take time off of work. Others forget their court dates or don’t understand the

consequences of not appearing, particularly when longer periods of time elapse between charges

and hearings.

35

35

B.H. Bornstein et al., “Reducing Courts’ Failure-to-Appear Rate by Written Reminders,” Psychology,

Public Policy, and Law 19, no. 1 (2013): 70-80; and Brice Cooke, Binta Zahra Diop, Alissa Fishbane,

34

Evelyn F. McCoy, Azhar Gulaid, Nkechi Arondu, and Janeen Buck Wilson, Removing Barriers to

Pretrial Appearance, (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, 2021).

33

A person can be released based on a judge’s discretion in a range of situations, such as if the judge

eliminates a person’s bond. Ninety percent of these “judge’s authority” releases for FTA admissions were

out of Lawrence Municipal Court.

32

“Covid-19 Impact on Jail Population and Criminal Justice Processing,” Presentation to Criminal Justice

Coordinating Council, (Douglas County, KS: June 9, 2020)

https://www.douglascountyks.org/sites/default/files/docs/county-news/pdf/june92020covidandcrimina

ljustice-jailpresentedtocriminaljusticecoordinatingcouncil.pdf.

25

Figure 13

Overall, 40 percent of admissions in which FTA was the top charge were classified

as traffic cases from either municipal or district court–and in over a third of those

cases, the people jailed lived in another county. Of the traffic-related FTA cases, 58

percent were from municipal court (all but 1 case were from Lawrence), and 42 percent were

from district court–primarily from the pro tem division, which handles criminal first

appearances, small claims, and traffic offenses. Thirty-five percent of traffic-related admissions

with an FTA top charge were for people with an address outside of Douglas County

(non-residents), mainly district court cases. The data suggests that a large number of failure to

appear warrants are being issued when people fail to appear in court following a traffic or

parking-related offense, and that this situation frequently leads to a subsequent arrest. This

raises questions about underlying misaligned incentives that may be fueling this practice. The

practice of using traffic enforcement and resulting warrants to collect court costs and “pay to

stay” jail fees is well-documented. Also called a “backdoor tax,” this is a mechanism increasingly

used by municipal governments to fund their operations without raising taxes.

36

For example,

the high-profile investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice into the Ferguson, MO Police

Department found that law enforcement practices were “shaped by the City’s focus on revenue

rather than by public safety needs,” raising constitutional concerns and compromising the role

of the municipal court.

37

Scrutiny practice of jailing poor people in connection with generating

revenue has not been confined to Ferguson, however and has resulted in lawsuits in multiple

states on grounds that it violates the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

38

38

“See for example, “Litigation: Cain v. New Orleans,” Fines and Fees Justice Center, August 23, 2019,

https://finesandfeesjusticecenter.org/articles/cain-v-new-orleans/; and “Wilkins v. Aberdeen

Enterprises,” Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse, November 2, 2017,

https://clearinghouse.net/case/17700/.

37

United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division, Investigation of the Ferguson Police

Department, (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Justice, 2015)

https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachments/2015/03/04/ferguson_polic

e_department_report.pdf.

36

Tony Messenger, Profit and Punishment: How America Criminalizes the Poor in the Name of Justice

(New York, NY, St. Martin's Press, 2021).

Jonathan Hayes, Aurelie Ouss, Anuj Shah, Using Behavioral Science to Improve Criminal Justice

Outcomes (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Crime Lab, 2018).

26

Economic research has also suggested a revenue-generating incentive for traffic enforcement,

showing a significant increase in tickets after revenue declines.

39

Probation violations

Probation violations were the fifth most common top charge for overall admissions and the

second-highest contributor to jail bed-days–accounting for over 49,000 bed-days from 2017 to

2021.

40

Probation violations were also the fourth most common top charge for admissions from

district court and the second most common top charge for out-of-county admissions. Probation

violations were also prevalent in municipal court, which only handles misdemeanors and

infractions, but they were less frequently the top charge. The portion of overall admissions with

a probation violation as the top charge declined slightly from 2017 to 2021, but the median

length of stay for probation violation admissions increased from 8 to 12 days.

Of the bookings with a probation violation as a top charge, 28 percent were released on cash or

surety bond. Only 13 percent were released on their own recognizance. An additional 21 percent

of people were released to a probation/parole agency, to house arrest, or to some other agency;

19 percent were released for time served; 7 percent were released under “judge’s authority”; and

5 percent were released to the DOC. More than 78 percent of bookings with a probation

violation as the top charge were released after 24 hours or more–staying in jail a median of 18.5

days.

41

According to discussions with the Lawrence Prosecuting Attorney in April 2022, the

Lawrence Municipal Court commonly jails people who have not been able to complete probation

requirements–such as the payment of court fines and fees or attendance at a court-mandated

program–and sets the bond at the same amount the person already owes the court. The

municipal court rationale is that, upon payment, a person’s outstanding court debt will be

settled. However, a person who could not pay a financial sanction prior to detention is unlikely

to be able to pay that same amount while detained, which could contribute to longer lengths of

stay. If a person is ultimately forced to pay the private bail industry a non-refundable percentage

of the bond to secure their release, it only deepens financial precarity and makes them more

vulnerable to future incarceration for nonpayment of costs, fees and fines. This practice opens

the county up to potential legal liabilities. Rutherford County, Tennessee was the subject of a

2015 class action lawsuit for its practice of jailing people for failing to pay probation fees, which

resulted in a monetary settlement and permanent injunction prohibiting an individual from

being "held in jail for nonpayment of fines, fees, costs or a pre-probation revocation money bond

imposed by a court without a determination, following a meaningful inquiry into the individual's

ability to pay, that the the individual has the ability to pay such that any nonpayment is

41

For this analysis, probation violations were separated out from pretrial admissions and sentenced

admissions. See figure 4 for details.

40

Unfortunately the data do not allow us to identify the nature of the probation violation, nor the original

charge for which the person was put on probation. However, we are able to differentiate technical

violations from more serious ones, because the more serious ones show up as other charges listed on a

booking–and these would outrank the probation violation as the “top charge” on a booking.

39

Thomas A. Garrett, Thomas A., and Gary A. Wagner. “Red ink in the rearview mirror: Local fiscal

conditions and the issuance of traffic tickets.” The Journal of Law and Economics 52, no. 1 (2009): 71-90;

Min Su. “Taxation by citation? Exploring local governments’ revenue motive for traffic fines.” Public

Administration Review 80, no. 1 (2020): 36-45.

27

willful.”

42

This practice has also been challenged in other jurisdictions. It also raises good

governance questions from a fiscal perspective, given that the county is paying to incarcerate

someone who is further impoverished by their jail stay. Previous Vera research has shown that

counties pay more to incarcerate people for nonpayment than they are able to generate in fines,

fees and costs.

43

Overall, 10 percent of all admissions from 2017 to 2021 had one or more probation violations

among the charges listed on the booking (even if a probation violation was not the top charge).

Figure 14 shows the most common types of accompanying charges for these bookings. Among

these admissions, probation violations were the only type of charge on the booking 45 percent of

the time. In 35 percent of cases, probation violations were accompanied only by

misdemeanor-level or unknown charges, failures to appear, supervision violations, remands, or

warrants but no new charges. In 20 percent of cases, probation violations were accompanied by

at least 1 felony charge.

Figure 14

Remands

Remands were the eighth most common top charge for overall admissions: they made up 3

percent of total admissions and accounted for 4 percent of bed-days. Remand refers to

court-ordered detention without bail, and was historically reserved for people charged with

capital offenses. However, in the data, remands are often listed without an accompanying charge

and with no indication of the originating charge, so it is somewhat difficult to assess how

remand is currently being used in Douglas County. We know that the use of remand has

increased in recent years, and the data suggests it is frequently used for less serious offenses.

From 2017 to 2021, the total number of admissions with remand as the top or sole charge

increased from 130 to 269 (+107 percent). The portion of admissions with remand top charges

43

Mathilde Laisne, Jon Wool, Christian Henrichson, Past Due: Examining the Costs and Consequences of

Charging for Justice in New Orleans (New Orleans: Vera Institute of Justice, 2017).

42

Rodriguez v. Providence Community Corrections, Inc., No. 3:15-cv-01048 (U.S. District Court for the

Middle District of Tennessee, 2018); Case Summary, Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse, accessed

October 5, 2022, https://clearinghouse.net/case/15160/.

28

increased from 3 percent to 8 percent, and the median length of stay for people with a remand

top charge was cut in half–from 5 days to 2. Of admissions with remand as top charge, the

majority came from district court (65 percent), and most had “sentenced county time” listed as

the judicial status. Further investigation is needed to understand how and why people are being

remanded in Douglas County, and the degree to which it reflects detention after the violation of

some of the conditions of release or supervision.

Overall, 51 percent of remand top charge admissions were classified as traffic

cases from either municipal or district court. Fifty-one percent of traffic-related remand

cases were from Lawrence municipal court, and 49 percent were from district court. Although

the data do not allow us to identify the exact originating charge leading to remand, this seems to

indicate that remand is being frequently used in practice to jail people for less serious

traffic-related charges, most of which are presumably low-level–particularly those originating

from municipal court.

44

Overall, 5 percent of all admissions from 2017 to 2021 had one or more remands among the

charges listed on the booking (even if remand was not the top charge). Among these admissions,

remands were the only type of charge on the booking 64 percent of the time. In 18 percent of

cases, remands were accompanied only by misdemeanor-level or less severe charges, failures to

appear, supervision violations, or warrants, and no other charges. In another 18 percent of

cases, remands were accompanied by one or more felony-level charges.

Admissions where a municipal charge is the only type of charge

Bookings where a municipal court charge was the only type of charge someone was facing

accounted for 30 percent of overall admissions and 8 percent of bed-days from 2017 to 2021.

45

This is an under-representation of bookings resulting from municipal court charges as it does

not include bookings with a mix of charges from district and municipal court, or those where a

municipal court charge is accompanied by an out-of-county charge. Figure 15 shows the

proportion of admissions by court type over the previous five years. The fact that a quarter to a

third of admissions to the jail over the past five years were due solely to municipal court

charges–which are generally low-level charges–signifies there is significant opportunity to

reduce the use of the jail for people charged with municipal offenses. This would also have a

positive impact on the City of Lawrences finances: according to data provided to Vera by local

government officials, Douglas County charges the City of Lawrence a daily fee to hold people

exclusively facing Lawrence Municipal Court cases. In 2023, the daily rate will be $226.

45

Municipal charges are those originating from Douglas County’s three municipal courts - one each for

Baldwin City, Eudora, and Lawrence - which primarily handle violations of city ordinances including

traffic and parking violations. This includes failures to appear, probation violations, and remands

originating from municipal court.

44

It is also important to note that almost all DUI charges from municipal court are categorized as “other”

cases and not “traffic” cases, and thus are not included in the traffic-related cases driving remands.

29

Overall, roughly 70 percent of people admitted only on one or more municipal charges were held

pretrial.

46

The majority were quickly released from jail; 60 percent of people admitted for

municipal charges were released the same day; those that stayed for 24 hours or more spent a

median of 3 days in jail.

Almost a third of admissions with only municipal charges were classified as traffic

cases. Of these admissions for traffic-related municipal charges, about 45 percent had an FTA

top charge, 41 percent had a “municipal/county violation” top charge (indicating the charge was

not listed or not known), 9 percent had a remand top charge, and 5 percent had a probation

violation top charge. People admitted on municipal traffic related charges spent a median of 2

days in jail; 33 percent were released for time served, 26 percent were released after posting

cash, surety or credit card bond, 14 percent were released to house arrest, 12 percent were

released per a judge’s authority, 9 percent had an unknown release reason, and only 3 percent

were released on their own recognizance.

Figure 15

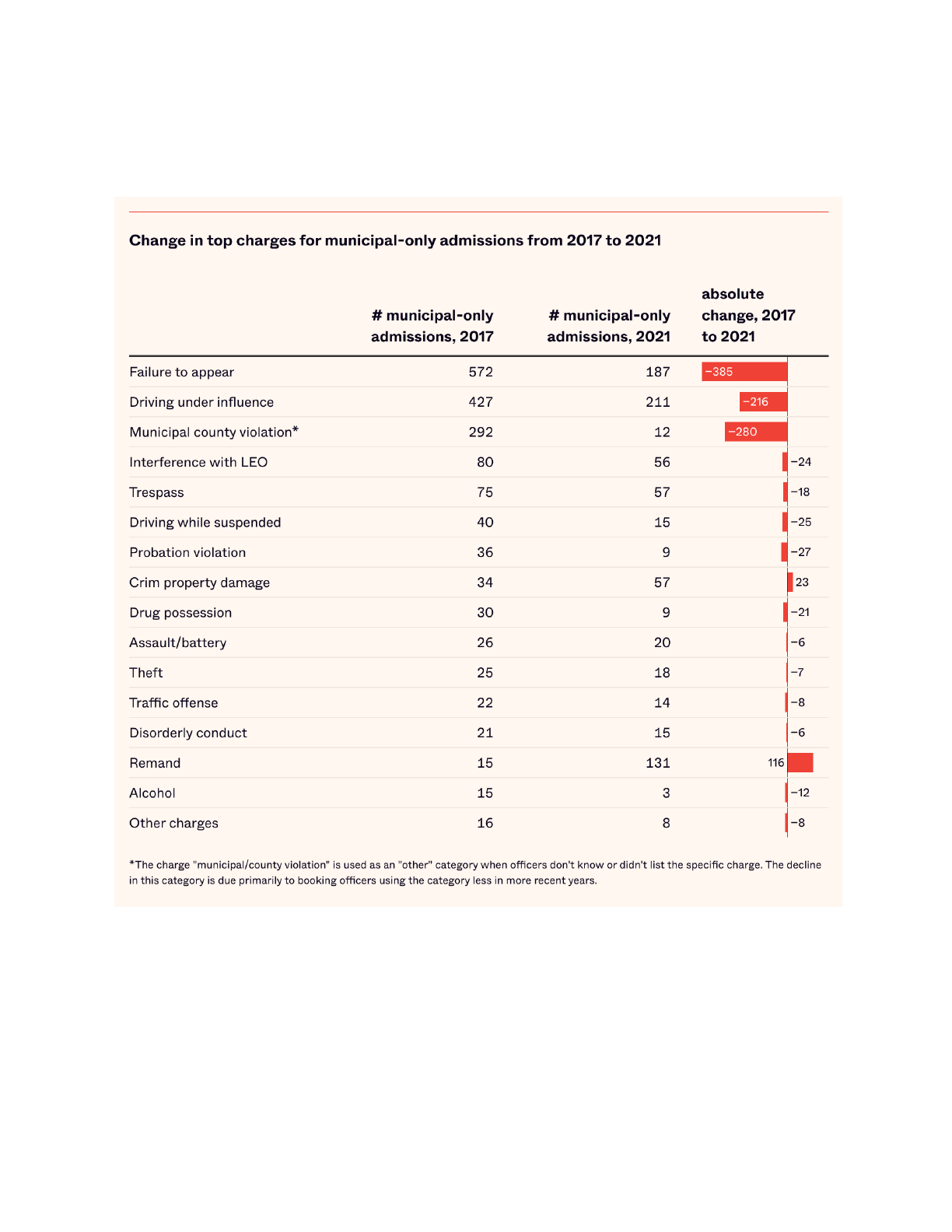

As noted above, bookings on municipal charges alone declined from 2018 to 2020, but then

increased from 2020 to 2021. Despite this slight downward trajectory, more is left to be done.

Figure 16 shows the change in the number of admissions for the top 10 most common top

46

The “pretrial” label may be inaccurate in a small number of municipal court cases. Some people’s

judicial status may be labeled as “pretrial” even though they are technically serving a sentence. Although it

is impossible to identify in the data how many people may have an inaccurate pretrial label, jail staff

indicate that this is likely a small number of people and that data practices have reduced this problem in

recent years.

30

municipal charges from 2017 and 2021, in order from most to least common type of charge in

2017.

Figure 16

Municipal-only admissions with a top charge of failure to appear or DUI declined during this

time. Municipal-only admissions with a top charge of probation violation, driving while

suspended, interference with a law enforcement officer, drug possession, and trespass also

declined moderately. These reductions likely reflect specific practice changes made by the

municipal court judges, such as creating warrant clinics. However, the number of

municipal-only admissions with remand as the top charge increased from 15 to 131 (+773

percent). As noted previously in this report, it is difficult to assess how remands are being used

in Douglas County due to data limitations. However, 98 percent of municipal-only admissions

31

with a top charge of remand originated in Lawrence municipal court, and about three-quarters

were classified as traffic-related cases. As noted above, this suggests that remand is being used

by the municipal court primarily to jail people in connection with low-level traffic-related

charges. Municipal-only admissions with criminal damage to property as a top charge also

increased from 34 to 57 (+68 percent).

To hone in on the most pressing issues to address in municipal court, figure 17 shows the

percentage of municipal-only admissions and bed-days for the top 10 most frequent types of

municipal charges in 2021–the most recent year of data included in this analysis. Failures to

appear and remands accounted for significant portions of municipal-only admissions and

bed-days, while driving under the influence charges made up a quarter of municipal-only

admissions and only 1 percent of bed-days. Nonviolent, nonperson charges including criminal

property damage, criminal trespass, interference with a law enforcement officer, theft, driving

while suspended, and disorderly conduct, combined, accounted for a quarter of municipal-only

admissions and 15 percent of municipal-only bed-days.

Figure 17

32

4. Systemic issues driving multiple bookings into the jail

As shown in figure 18, the majority of people (61 percent) were admitted to the jail once from

2017 to 2021. However, people with one jail stay only made up about a third of admissions and

22 percent of bed-days. About 40 percent of people were admitted two or more times;

these individuals made up 70 percent of admissions and 78 percent of bed-days.

Figure 18

People with multiple bookings were more likely to be admitted and to spend longer in jail for

administrative charges than people who were admitted only once. Figure 19 shows admissions

and bed-days by top charge type for people with one booking versus people with multiple

bookings from 2017 to 2021. People with multiple bookings were more likely to be admitted for

a failure to appear, probation violation, remand, or parole violation than people with one

booking. This indicates that violations of probation and/or other forms of supervision are a

significant driver of recurring jail admissions: once people have more than one jail booking, they

likely become more entangled in the various system and supervision requirements and assorted

penalties for non-compliance. Evidence also suggests that people on probation have markedly

higher rates of behavioral health challenges than the general population, making compliance

with complicated and/or strict conditions of release even more challenging to navigate.

47

47

Alex Roth, Sandhya Kajeepeta, Alex Boldin, The Perils of Probation: How Supervision Contributes to

Jail Populations. (New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2021), 9.

33

Figure 19

A subset of people–581 individuals–were admitted to the jail six or more times from 2017 to

2021. This group of people accounted for almost a quarter of all admissions and 35 percent of

bed-days. About 43 percent of admissions for this group of people were due to administrative

charges such as failures to appear, probation violations, remands, parole violations, and arrest

warrants. Another 31 percent of these admissions were due to nonperson, nonviolent charges,

and 16 percent were due to violent, person, or weapons-related charges–most commonly for

charges related to domestic violence, although these were slightly less prevalent than for overall

admissions. Of the admissions for nonperson, nonviolent charges, the most common top