Benchmarking E-government:

A Global Perspective

Assessing the Progress of the UN Member States

United Nations

Division for Public Economics and

Public Administration

American Society for

Public Administration

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

i

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements iv

About the Project v

Section page number

Section 1: The 2001 Global E-government Landscape 1

1.1 Executive Summary 1

1.2 E-government Profile of the UN Member States 1

1.3 The E-government Index 2

1.4 Important Global Trends in 2001 3

1.5 The Information Decade 4

Section 2: Benchmarking E-government 8

2.1 Services are the Public Face of Government 8

2.2 Current Benchmarking Practices 10

2.3 The Stages of E-government 11

2.4 Country Progress 13

Section 3: Analysis of Stages 15

3.1 Overview 15

3.2 Emerging Presence 16

3.3 Enhanced Presence 17

3.4 Interactive Presence 17

3.5 Transactional Presence 19

3.6 Website Evaluation as a Benchmarking Tool 21

Section 4: The E-government Index 22

4.1 Ensuring an Enabling Environment 22

4.2 Compiling the E-gov Index 24

4.3 Global Overview 27

4.4 Change: The Essential Process of the E-gov Universe 28

Section 5: Geographic Regional Analysis 34

5.1 North America 35

5.2 Europe 37

5.3 South America 40

5.4 The Middle East 41

5.5 Asia / Oceania 42

5.6 Central America 44

5.7 The Caribbean 45

5.8 Africa 45

Section 6: Public Administration and E-government 48

6.1 E-administration: 48

Challenges of Governing in the Information Age

6.2 Administrative Issues in 2001 50

6.3 E-Governance 53

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

ii

Conclusion 56

Appendix 1: Member States’ E-government Index By Region 57

Appendix 2: Best Practices Developed by Firstgov.gov 63

Appendix 3: Sample Questionnaire 64

Appendix 4: Website Evaluation Form 67

Selected Online Resources 69

References 71

Endnotes 74

Boxes

Box 1: Online Profile of UN Member States 1

Box 2: The Stages of E-Government 2

Box 3: National governments roles in an information society 4

Box 4: The Principles of E-Government 6

Box 5: The Stages of e-Government 10

Box 6: Single Entry Portals Are Standard 18

Box 7: Single Entry Portals: Several Excellent Examples 18

Box 8: Online Tax Transactions 19

Box 9: September 11, 2001 21

Box 10: Factors Impeding an Enabling E-gov Environment

in Developing Countries 22

Box 11: Global Online Population 23

Box 12: Indexing South America 26

Box 13: E-Government Program Development 50

Box 14: The Framework of E-Governance 54

Charts

Chart 1: Country Stages for 2001 12

Chart 2: E-Gov Index by Geographic Regions 34

Chart 3: Percentage of Population Online By Region in 2001 40

Chart 4: Information Access Measure by regions 42

Chart 5: Telephone lines and mobile phones / 100 inhabitants

by region in 2001 47

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

iii

Tables

Table 1: 2001 Global E-gov Leaders 3

Table 2: The 2001 E-Government Index 7

Table 3: Global Online Population 23

Table 4: Global Leaders 24

Table 5: Indices for South America 26

Table 6: 2001 Global E-Government Indexes 30

Table 7: Geographical Regional Comparison of Indicators 34

Table 8: Index – North America 35

Table 9: Index – Europe 37

Table 10: Index – South America 40

Table 11: Index – Middle East 41

Table 12: Index – Asia / Oceania 43

Table 13: Index – Central America 44

Table 14: Index – Caribbean 45

Table 15: Index – Africa 46

Table 16: Barriers to E-government 49

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

iv

A

CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Benchmarking E-government: Assessing the United Nations Member States was made

possible through a collaboration between the American Society for Public Administration

(ASPA) and the United Nations Division for Public Economics and Public Administration

(UNDPEPA) of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA).

There are several individuals we wish to acknowledge for their cooperation, assistance

and guidance in the research and preparation of this report. We would like to thank

Ms. Mary Hamilton, Ph.d, Executive Director, ASPA, who made available the

organization’s membership and staff. We would also like to thank Prof. Marc Holzer,

Rutgers University, Newark, New Jersey, Director, Ph. D. Program in Public Administration

and founder of the E-Governance Institute at Rutgers University --- Newark whose

expertise in the area of performance measurement proved of great value.

We would also like to express our deepest appreciation to the members of the Office of

the E-Envoy of the United Kingdom; the E-government Project Team, Department of the

Taoiseach, Government of the Republic of Ireland and the members of the United States

Government’s Firstgov.gov team and the United States General Services Administration,

in allowing access to their respective units and who were extremely generous with their

knowledge, ideas and time.

We would further like to thank the following individuals who provided an invaluable

service in conducting research: Dr. Jafar M. Jafarov, UNDP; Laura Forlano, Ph.d

candidate, Columbia University, Sylvie Angelou, New York University, and especially

Dana Curran of Columbia U. for her country analysis and Jesse Catral of Rutgers

University for his insightful assistance and statistical analysis in developing the

e-government index.

Finally, we would like to express our deepest appreciation and heart felt thanks to

Mr. Guido Bertucci, Director, UN Division for Public Economics and Public Administration,

for without his vision and support, this study would have remained a proposal.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

v

A

BOUT THE

P

ROJECT

In an effort to gain an appreciation of the global e-government landscape in 2001, the

United Nations Division for Public Economics and Public Administration (UNDPEPA) and

the American Society for Public Administration (ASPA) undertook a research study

analyzing the approach, progress and commitment on the part of the 190 UN Member

States.

The study’s primary goal was to objectively present facts and conclusions that define a

country’s e-government environment and demonstrate its capacity to sustain online

development. This was accomplished by a comparative analysis of fundamental

information and communication technology (ICT) indicators and critical human capital

measures for each UN Member State. The final measure or E-government Index could be

useful tool for policy-planners as an annual benchmark.

In determining what defines an enabling environment, this report analyzed critical factors

by benchmarking the core areas endemic to national e-government programs. The final

measure or E-government Index attempts to objectively quantify these factors, and

establish a “reference point” for which a country can measure future progress.

The E-government Index presents a more inclusive and less subjective measure of a

country’s e-government environment. It incorporates a country’s official online presence,

evaluates its telecommunications infrastructure and assesses its human development

capacity.

The website research was conducted during two intervals from May to July and October

to December, 2001 in order to measure progress and ensure accuracy. Each Member

State was examined using sites available on the world wide web during these periods.

E-government development can be swift and continuous, yet inchoate. Change and

improvement must be a permanent part of the process if a country is to achieve the

stated goals within its strategic framework and to offer the most inclusive citizen-centric

approach. Unquestionably, many of the UN Member States will have a different look six,

even three months from the release of this report.

Progressive governments are upgrading their sites regularly; expanding the types and

quality of their online services and improving their content daily in an effort to achieve

the highest measure of user satisfaction, administrative efficiency and cost effectiveness.

The research and analysis conducted for this research is an appraisal taken at a

particular period in time --- a digital photo of the global e-gov landscape during 2001.

Stephen A. Ronaghan

Project Coordinator and

author of the final report

New York

May, 2002

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

vi

Stephen A. Ronaghan has been employed by the United Nations as a policy analyst and

project coordinator since 1994. He has worked on several information and

communications technology (ICT), public sector management and governance projects

and has contributed to numerous research studies and policy analyses. Mr. Ronaghan

has also worked in the area of UN project and program evaluation and performance

measurement. He received an M.P.A. from New York University’s Robert F. Wagner

Graduate School of Public Service in 1993.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

1

S

ECTION

1:

T

HE

2001G

LOBAL

E-

GOVERNMENT

L

ANDSCAPE

1.1. Executive Summary

Since the mid -1990s governments

around the world have been executing

major initiatives in order to tap the vast

potential of the internet for the distinct

purpose of improving and perfecting the

governing process. Like the personal

computer, the internet has become an

indispensable tool in the day-to-day

administration of government. In an

effort to gain an appreciation of the

global e-government landscape in 2001,

the American Society for Public

Administration (ASPA) and the United

Nations Division for Public Economics

and Public Administration (UNDPEPA)

undertook a research study analyzing

the approach, progress and

commitment on the part of the 190 UN

Member States.

Broadly defined, e-government can

include virtually all information and

communication technology (ICT)

platforms and applications in use by the

public sector. For the purpose of this

report however, e-government is

defined as:

utilizing the internet and the

world-wide-web for delivering

government information and services to

citizens.

In order to maximize e-government’s

effectiveness and realize its vast

potential, several fundamental

conditions must exist in order to

facilitate an enabling environment. The

study’s primary goal was to objectively

present facts and conclusions that

define a country’s e-government

environment and demonstrate its

capacity (or lack of) to sustain online

development. This was accomplished by

a comparative analysis of fundamental

information technology (IT) indicators

and critical human capital measures for

each UN Member State.

Two methodologies were used in the

research. First, national government

websites were analyzed for the content

and services available that the average

citizen would most likely use. The

presence, or absence of specific

features contributed to determining a

country’s level of progress. The stages

present a straightforward benchmark

which objectively assesses a country’s

online sophistication. Second, a

statistical analysis was done comparing

the information and communication

technology infrastructure and human

capital capacity for 144 UN Member

States. The final measure or

E-Government Index could be useful

tool for policy-planners as an annual

benchmark.

1.2. E-government Profile of the UN

Member States

National e-government program

development among the UN Member

States advanced dramatically in 2001.

Box 1: Online Profile of UN Member States

UN Member States: 190

with a government website presence: 169

with a National Government Website: 84

with single entry portals: 36

with sub-national govt websites: 84

with online transaction capacity: 17

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

2

Countries whose web presence in

previous years consisted of one or two

static government web pages began

offering content rich, well-designed,

citizen-centric sites. But despite creative

initiatives, national e-government

program development remains

overwhelmingly at the information

provision stage. The level of

sophistication in which countries are

using the internet to deliver quality

information does, however, vary

considerably.

Full-fledged commitment to

e-government implies that a country’s

leadership recognizes the fact

information has become a social and

economic asset just as important and

valuable as traditional commodities and

natural resources. Information benefits

the most the individuals and industries

which have unimpeded access to its

acquisition, and the self-determination

to convert essential data into

knowledge. The theme of this report,

therefore, is “facilitating information

access for enhanced citizen

participation through e-government”.

In 2001, of the 190 UN Member States,

169 (88.9%), of their national

governments used the internet in some

capacity to deliver information and

services. For 16.8% of these

governments, their presence on the

internet was just emerging. The official

information offered in these countries

was often static in content and limited

to only a few independent websites.

Countries with an enhanced internet

presence --- where users can access an

increasing number of official websites

that provide advanced features and

dynamic information ---- represented

34.2%, the highest number among the

Member States. Thirty percent of the

countries surveyed offered interactive

online services where users have access

to regularly updated content and,

among other things, can download

documents and e-mail government

officials. The capacity to conduct

transactions online, where citizens can

actually use the internet to pay for a

national government service, fee or tax

obligation, was offered by 17 national

governments, or only nine percent of the

UN Member States.

A country's social, political and

economic composition most definitely

correlates closely with its e-government

program development. However there

were exceptions, as evidenced by

several developing and transitioning

economies. Key factors such as the

state of a country’s telecommunications

infrastructure, the strength of its human

capital, the political will and

commitment of the national leadership

and shifting policy and administrative

priorities play important roles. Each of

these factors influence how decision

makers, policy planners and public

sector managers elect to approach,

develop and implement e-government

programs.

1.3. The E-government Index

In determining what defines an enabling

environment, this report analyses the

above issues by benchmarking the core

areas endemic to national

e-government programs. The final

measure or E-government Index

attempts to: 1) objectively quantify

Box 2: The Stages of E-Government

Emerging: An official government online presence

is established.

Enhanced: Government sites increase; information

becomes more dynamic.

Interactive: Users can download forms, e-mail

officials and interact through the web.

Transactional: Users can actually pay for services and

other transactions online.

Seamless: Full integration of e-services across

administrative boundaries.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

3

these critical factors and 2) establish a

“reference point” for which a country

can measure future progress.

The E-gov Index presents a more

inclusive and less subjective measure of

a country’s e-government environment.

It incorporates a country’s official online

presence, evaluates its

telecommunications infrastructure and

assesses its human development

capacity.

The Index identifies, underscores and

weighs the importance of the requisite

conditions which enable a country to

sustain an e-government environment

which ensures that every segment of its

population has unconstrained access to

timely, useful and relevant information

and services.

Not surprisingly, the results of the E-gov

Index tend to reflect a country’s

economic, social and democratic level

of development. Industrialized nations,

whose citizens enjoy the benefits of

abundant resources, superior access to

information and a more participatory

relationship with their governments, rank

well above the mean E-Gov Global

Index of 1.62.

Geographically by region, North

America (2.60), Europe (2.01), South

America (1.79) and the Middle East

(1.76) all registered an index above the

global mean. Asia (1.38), the Caribbean

(1.34) Central America (1.28) and Africa

(0.84) fell below the global index.

Among individual countries, the United

States (3.11

) is the current global leader

and was the only country to register an

index above 3.00. By geographic region

the leaders in 2001 were: North

America: United States; Europe: Norway

(2.55); South America: Brazil (2.24);

Middle East: Israel (2.26

); Asia /

Oceania: Australia (2.60

); Africa: South

Africa (1.56); Caribbean: the Bahamas

(1.79

); Central America: Costa Rica

(1.42

).

1.4. Important Global Trends in 2001

E-government can offer numerous

possibilities for improving how a nation’s

public sector responds to the basic

needs of its citizens. There is however a

wide variance as to the process in which

governments choose to realize such

potential.

Throughout the course

of researching this

report,

we were able to gain

access to a

considerable number

of high level policy and

decision makers,

dedicated public

sector managers,

administrators and civil

servants working on

their country’s national

e-government

programs. Onsite visits were made to

several countries, while in-depth

interviews were conducted by

telephone and e-mail. A questionnaire

(see appendix 3)was also sent to

selected individuals. Many generously

shared their expertise, knowledge and

thoughts with us. Below are some of their

most important insights.

► A country’s overall progress in

e-government closely correlates

with its social, political or

economic composition. The

more effective programs

prioritize development to reflect

ICT, human resources and user

capacities.

► National E-government program

development remains desultory

and unsynchronized. A

compelling lack of coordination

exists across administrative and

policy boundaries. Ultimately this

may compromise program

effectiveness and performance

efficiency.

USA 3.11

Australia 2.60

New Zealand 2.59

Singapore 2.58

Norway 2.55

Canada 2.52

UK 2.52

Netherlands 2.51

Denmark 2.47

Germany 2.46

Table 1:

2001 Global E-

g

ov Leaders

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

4

► Online service delivery should be

thought of as complementary

rather than accepting the more

popular view that it will ultimately

replace many traditional

channels for service delivery.

► Increased access to the world

wide web does not automatically

transform into increased use of

e-government as user interest

has been low and indifferent.

► There exists a significant digital

divide within national public

administrations.

► Single Entry Portals are an

accepted and important

standard.

► Prioritizing online service delivery

to the business community is a

implementation strategy in

several emerging economies at

the expense of citizen-centric

service delivery.

► National E-gov management

teams in 2001 were the

exception rather than the rule.

► There is a considerable lack of

public awareness campaigns

informing citizens that national

governments are offering online

service delivery.

► Cost Effectiveness: The belief

that online service delivery is less

costly than other channels is not

wholly unfounded. However

there exists little empirical

evidence to support this

assertion.

► With few exceptions funding

e-government is tied directly to

the level of commitment on the

part of the political leadership.

Perhaps the most compelling finding of

the survey, however is: for a large

majority of countries, national

e-government program development is

occurring in a swift and dynamic

manner and for now change is the only

constant.

1.5. The Information Decade

Over the past ten years the dramatic

advances made in information and

communications technology (ICT) have

transformed much of the world into a

digitally interconnected community that

is increasingly functioning on a “365 / 24

/ 7” basis. Throughout this period,

especially the past five years, the

predominant drivers of change have

been the internet and the world wide

web. Both have added a new, and

arguably indispensable "e" dimension to

academia, commerce, and now

government.

Considerable resources, both human

and financial, are being committed to

launching and perfecting programs

which deliver government information

and services online. Such initiatives are

intended to improve administrative

operations and enhance government

efficiency while realizing the residual

effect of deeper citizen involvement in

the governing process. From

Armenia

to

Box 3: National governments play four

distinct roles in an information society

►

Determine the policies and

regulatory structures

►

Deliver the programs and services

of government to the citizen

►

Use the information infrastructures

to enhance the internal

administrative practices

►

Interface with citizens in the

democratic process of

government.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

5

Zambia the concept of e-government is

being openly embraced.

For most of the UN Member States,

electronic service delivery, or

e-government, is still a new and

challenging medium. To be precise,

e-government encompasses many

applications and incorporates virtually

all ICT platforms. However, it is the

internet that is the most widely

recognized and identifiable component

driving e-government. A major indicator

of a society’s openness is access to the

information available on the internet.

Restrictive states have sought ways to

contain or manage information and

access, ultimately compromising an

enabling e-government environment

1

.

The year 2001 saw a greater expansion

in government online presence than the

previous five years combined. Website

content and online applications

progressed from static, public affairs

“e-brochures” to virtual information

centers where the interaction between

citizen users and the public sector is

continuous. Last year also saw an

increase in the online transaction of

business with government.

In 2001, it was estimated that globally

there were well over 50,000 official

government web-sites (22,000 sites in the

US Federal government alone) with

more coming online daily.

∗

In 1996 less

than 50 official government homepages

could be found on the world-wide-web.

Of the 190 UN Member States, 169 were

providing some degree of information

and services online. Based on the

available resources, policy priorities and

political commitment, however, the

scope and content of national

∗

See Worldwide Governments on the World Wide

Web: http://www.gksoft.com/govt/en/world.html

e-government programs contrast

substantially. Namibia's Ministry of Health

and Social Services

(www.healthforall.net/grnmhss/) for

example, maintains an effective

information gateway despite extremely

inadequate resources, while the

Republic of Korea’s National Tax Service

( www.nta.go.kr/

) is indicative of what

can be done with unabridged

commitment and support.

E-government development is constant

and conspicuous. It has received

considerable attention through a steady

stream of events at the national and

international levels. In March 2001, for

example, the Third Global Forum on

Reinventing Government

(

www.globalforum.org

) chose for its

theme: “Fostering Development

through E-government”. Participants

from 122 nations, which far exceeded

the combined official representation of

the first two Global Forums,

met in

Naples, Italy to share best practices,

information and ideas.

The Third Global Forum articulated the

following key points:

► E-government can consistently

improve the quality of life for citizens

and can create a sharp reduction of

costs and time.

► E-government will eventually

transform the processes and structures of

government to create a public

administration less hierarchical,

empowering civil servants to serve

citizens better and to be more

responsive to their needs.

► E-government must be given

serious consideration also in the

developing countries not only for its

potential for stronger institutional

capacity building, for better service

delivery to citizens and business (thus

increasing local social and economic

development), for reducing corruption

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

6

by increasing transparency and social

control, but also for “showing the way”

to the civil society and business

community.

Wide-ranging e-government programs

remain at, or near, the top of most

countries’ policy agendas. For many

nations, digitizing service deliveries like

filing personal income taxes online or

paying VATs electronically represents a

marked departure from the traditional

paper-based way of doing business. For

some countries, such departures have

culminated in success. For others the

challenge is formidable, but not

insurmountable.

When asked to describe the ultimate

benefit of e-government, the most

consistent response given by decision-

makers and public sector professionals

interviewed for this report was that it

transforms governance like no previous

reform or reinvention imitative.

E-government potentially empowers

individual citizens’ by providing them

with an alternative channel for

accessing information and services and

interacting with government.

It also gives the individual citizen another

choice: whether to become an active

participate in the governing process or

remain a passive observer.

Providing citizens with new choices is a

goal that resonates throughout many of

the national e-government strategic

plans. Both the intended and the

residual outcomes of this objective are

considerable: open communication,

enhanced transparency, increased

social inclusion and citizen participation,

democratic enrichment and superior

governance. These outcomes however,

tend to be more potential then extant,

and objectively quantifying a

potentiality is in itself a test. This study ---

the first global effort at benchmarking

e-government --- is in itself a challenge

as it attempts to balance both the

abstract and the tangible in order to

enlighten.

But perhaps what e-government is

ultimately about is opportunity.

Opportunity to transform a public sector

organization’s commitment so it can

function as truly citizen-centric.

Opportunity to provide cost effective

services to the private sector

contributing to the development of

business and promoting long-term

economic growth. Opportunity to

enhance governance through improved

access to accurate information and

transparent, responsive and democratic

institutions. The types of services that can

be delivered over the internet are still

being conceived, developed and

improved by both the public and

private sectors. Over the next few years

expect to see a increased

experimentation, innovation and

organizational learning in an effort to

perfect e-government.

Box 4: The Principles of E-Government

► Build services around citizens’ choices

► Make government and its services

more accessible

► Facilitate social inclusion

► Provide information responsibly

► Use government resources effectively

and efficiently

UK Government White Paper

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

7

Table 2:

The 2001 E-Government Index

Global Index: 1.62

High E-gov Capacity

Medium E-gov Capacity

Minimal E-gov Capacity

Deficient E-gov Capacity

2.00 - 3.25

1.60 - 1.99 1.00 - 1.59 Below 1.00

USA 3.11 Poland 1.96 Armenia 1.59 Cameroon 0.99

Australia 2.60 Venezuela 1.92

Brunei 1.59 Cent African Rep. 0.98

New Zealand 2.59 Russian Fed. 1.89 South Africa 1.56 Ghana 0.98

Singapore 2.58 Colombia 1.88 Paraguay 1.50 Nepal 0.94

Norway 2.55 Latvia 1.88 Cuba 1.49 Thailand 0.94

Canada 2.52 Saudi Arabia 1.86 Philippines 1.44 Congo 0.94

UK 2.52 Turkey 1.83 Costa Rica 1.42 Maldives 0.93

Netherlands 2.51 Qatar 1.81 Panama 1.38 Sri Lanka 0.92

Denmark 2.47 Lithuania 1.81 Nicaragua 1.35 Mauritania 0.91

Germany 2.46 Ukraine 1.80 Djibouti 1.35 Bangladesh 0.90

Sweden 2.45 Bahamas 1.79 Dominican Rep. 1.34 Kenya 0.90

Belgium 2.39 Hungary 1.79 Trinidad & Tobago 1.34 Laos 0.88

Finland 2.33 Greece 1.77 Indonesia 1.34 Angola 0.85

France 2.33 Jordan 1.75 Jamaica 1.31 Haiti 0.84

Rep of Korea 2.30 Bolivia 1.73 Iran 1.31 Mauritius 0.84

Spain 2.30 Egypt 1.73 Azerbaijan 1.30 Tanzania 0.83

Israel 2.26 Slovakia 1.71 India 1.29 Senegal 0.80

Brazil 2.24 Slovenia 1.66 Kazakhstan 1.28 Madagascar 0.79

Italy 2.21 Mongolia 1.64 Belize 1.26 Zimbabwe 0.76

Luxembourg 2.20 Oman 1.64 Barbados 1.25 Burkina Faso 0.75

Unit. Arab Emir. 2.17 Ecuador 1.63 Guyana 1.22 Zambia 0.75

Mexico 2.16 Suriname 1.63 Honduras 1.20 Mozambique 0.71

Ireland 2.16 Malaysia 1.63 El Salvador 1.19 Sierra Leone 0.68

Portugal 2.15 Romania 1.63 Guatemala 1.17 Cambodia 0.67

Austria 2.14 Belarus 1.62 Gabon 1.17 Comoros 0.65

Kuwait 2.12 Peru 1.60 Turkmenistan 1.15 Guinea 0.65

Japan 2.12 Uzbekistan 1.10 Namibia 0.65

Malta 2.11 Vietnam 1.10 Togo 0.65

Iceland 2.10 Samoa (Western) 1.09 Gambia 0.64

Czech Republic 2.09 Cote d'lvoire 1.05 Malawi 0.64

Argentina 2.09 China 1.04 Mali 0.62

Estonia 2.05 Pakistan 1.04 Ethiopia 0.57

Bahrain 2.04 Nigeria 1.02 Chad 0.55

Uruguay 2.03 Kyrgyzstan 1.01 Niger 0.53

Chile 2.03 Botswana 1.01 Uganda 0.46

Lebanon 2.00

Tajikistan 1.00

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

8

S

ECTION

2:

B

ENCHMARKING

E-

GOVERNMENT

2.1. Services are the Public Face of

Government

Virtually all government services can be

classified under one of three

fundamental categories: informational,

interactive and transactional. The first,

informational, is by far the most

significant. Information is at the heart of

every policy decision, response, activity,

initiative, interaction and transaction

between government and citizens,

government and businesses and among

governments themselves. How

information is collected, processed,

analyzed, packaged and disseminated

is in itself a specialized industry.

2

Successful citizen-centric e-government

programs emphasize the indispensable

nature of information while balancing its

often limited shelf-life and considerable

inflationary component. In the

information and knowledge age, there is

no institution that produces raw data

and new information with more

regularity than government.

Since services are the public face of

government, the primary objective of all

e-government initiatives is to provide the

citizen user with an efficient alternative

medium for interacting with public

sector service providers. This is generally

accomplished by improving the flow of

information both externally and

internally. Information is government’s

most fundamental output

3

and

consequently, transforming ministries,

departments, agencies, units and staff

to make them “e”-ready is an intense

and challenging process.

Eighty-eight percent of the UN Member

States have made at a legitimate effort

to commit to some form of

e-government; that is 169 countries have

an established online presence with

official government websites. However,

in 2001, for over 25% of the countries, the

content of official websites consisted of

static and insufficient information often

of a public relations nature and

consistently with strong political

overtones. Such sites can hardly be

described as service delivery or

considered citizen-centric since they are

not a medium to elicit useful feedback.

This trend is predominant in a several

emerging countries in Asia, the

Caribbean and throughout Sub-Sahara

Africa where countries like Zimbabwe

(www.gta.gov.zw/

) exploit the web for

very singular purposes.

The industrialized countries have taken a

less desultory approach in developing

their programs and the types of services

they are providing. This is particularly

evident throughout Europe, North and

South America as nearly all the countries

in both regions have highly dynamic

and interactive official government

websites, where content is accurate,

specialized and regularly updated.

The capacity to conduct transactions

online at the national government level

in 2001 was available in 17 countries.

There was also considerable activity at

the sub-national level, which would

suggest that in countries where

e-government is evolving autonomously

or without a coordinated national

strategic program, transactional service

delivery will occur irregularly with, in

many cases, local governments

demonstrating such a capacity before

the national government.

Although online transactions are one of

the primary features that justify a wide-

ranging e-government initiative, it is

worth noting, that despite the benefits of

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

9

technological and the impact of

globalization, the national economies of

over 75% of the countries indexed are

substantially cashed based.

4

In the

majority of these societies, credit-card

use is still reserved for a select and

privileged minority. Consequently, the

necessity for online transactions in such

countries may not be as great as the

need for reliable information.

Credible information is sine qua non for

maintaining a balanced and open

dialogue between decision-makers and

the civil society. The policy participation

process is one example.

A higher level of participation that goes

beyond just providing feedback and

comment is the participation of citizens

in the processes of policy development

and decision making of government.

Traditionally this has been practiced

through the use of voting and referenda

and again mostly at community and

local levels. It goes beyond simply

providing feedback; rather it is a process

of discussions and negotiations which

often involves personal interaction.

5

E-government potentially increases

citizen involvement in the process of

governance at all levels by introducing

new voices to the dialogue through

online discussion groups, thus expanding

outreach and influence while

enhancing the rapid development and

effectiveness of interest groups.

6

In the United States for example, there is

concern among academics, activists,

and elected officials that government

websites might focus more on providing

services, and less on facilitating civic

involvement. This type of service

orientation, they argue, treats citizens as

consumers rather than partners in

government, and thus inhibits public

engagement with the nation’s political

environment.

7

While users are certainly taking

advantage of all the services and

information made available on

government sites, a smaller portion are

active in using the Internet to monitor

public affairs. In 2001, an estimated 42

million Americans (24% of those with

access) used government Web sites to

research public policy issues; 23 million

(13% with access) used the Internet to

send comments to public officials about

policy choices; and 13 million (7.5% with

access) participated in online lobbying

campaigns.

∗

Despite the incredible advances made

in information technology, digitizing

government is, and will continue to be

into the foreseeable future, a complex

and constant process. Countries vary

radically in their approach, level of

development and overall commitment

to e-government. Critical endemic

factors like available resources, political

leadership, economic capacity and the

character of the civil society deeply

impact on the scope and breadth of a

government's e-gov policy. How a

nation ultimately shapes its

e-government commitment ideally

should consider these factors and

respect the citizen-centric approach

rather than being influenced by short-

lived trends or what outcomes may be

politically expedient.

For countries, like the United Kingdom

(

www.ukonline.uk.gov

) launching an

e-government program is an extensive,

meticulously planned exercise with

ambitious goals and targets. The UK also

enjoys the advantages of unabridged

political support. For other nations,

especially those in Sub-Sahara Africa,

just going online can be a frenetic leap

from the past into the future with little

time to absorb the present.

E-government is a new and for the most

part a nascent activity. Program success

∗

Source: Pew Internet & American Life Project

Government Web Sites Survey, September 5-27,

2001 N=815. Margin of error is ±4%.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

10

is not necessarily measured by the

increase in the number of government

websites, the number of daily “hits” or

user visits to each site, or by the number

of officials who can be accessed by

e-mail. (Though for many countries

producing a fully interactive, service

oriented website is a task not to be

taken lightly.) Successes are kept in

perspective, and setbacks are to be

expected. Despite the highly visible and

multi-functional sites, many governments

continue to "flight test" their programs in

an attempt to find the right combination

of services, features, content and entry

points that are efficient, cost-effective

and truly citizen-centric. However, time

in cyberspace does not allow

governments to celebrate very long

their accomplishments, nor mull over

their setbacks.

2.2. Current Benchmarking Practices

Benchmarking is an essential and

valuable exercise since the practice

allows individuals to mark a specific

policy or program’s progress and

chronicle successes and setbacks over a

given period of time. This provides policy

developers, decision makers and public

sector managers with vital information in

order to make mid-course adjustments,

improve program efficiency and ensure

that the tax-payers are getting a return

on their ‘investment’. Several countries,

international organizations and private

sector consulting firms have developed

useful tools in an attempt to measure e-

government progress through a series of

targets that mark a specific stage of

development.

The primary research conducted for this

report was gathered for two purposes:

first, to gain an appreciation and

understanding of the global

e-government landscape and; second,

to quantify data so to develop and test

a new and impartial benchmarking

practice. The research sought to assess

how governments have approached,

developed and implemented online

service delivery. The research also

sought to maintain objectivity, yet to be

as inclusive as possible in determining all

UN Members’ level of development

based on the available data.

A practice currently in use by

governments, international organizations

and private sector firms charts progress

through a series of levels or stages

marked by the presence (or absence) of

fundamental online applications and

basic features. The primary research for

this report has benchmarked a country’s

progress using the tools and methods

being practiced by the European Union

(www.eu.org), the United Kingdom’s

Office of E-Envoy; the United States

Government’s General Services

Administration; and Ireland’s national

e-government program.

Box 5: The Stages of e-Government

Emerging: A government web

presence is established

through a few

independent official

sites. Information is

limited, basic and static.

Enhanced: Content and information

is updated with greater

regularity.

Interactive: Users can download

forms, contact officials,

and make appointments

and requests.

Transactional: Users can actually pay

for services or conduct

financial transactions

online.

Seamless: Total integration of e-

functions and services

across administrative

and departmental

boundaries.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

11

Using the world wide web, all 190 UN

Member States were accessed and over

1900 national government websites

examined in order to analyze and chart

each country’s level of progress. The

citizen-centric approach was the basis

for our analysis. That is sites

(predominately cabinet ministries and

departments) and sectors considered to

be most representative of services that

the majority of citizens were likely to seek

were evaluated. The primary or target

sectors were: health, education, labor or

employment; social welfare and

services, and finance. Countries were

also evaluated for a capacity to

conduct transactions online.

∗

Countries were assessed by the following

criteria:

► An official government web

presence must exist.

► The type of service delivery

available: basic or informational,

interactive, transactional.

► The presence and of services in

five critical sectors: education,

health, labor/employment,

welfare/social services and

financial services.

► Use of single entry portals; and

de facto portals (official national

government websites).

► To a lesser degree, fidelity to

strategic plans, use of e-gov

teams.

2.3. The Stages of E-government

Development

National (and for that matter, regional

and local) government strategic

planning, characterizes e-government

∗

Here we took a broader approach to the

research, not restricting the transactional capacity

to the targeted sectors.

development as a linear progression,

with service providers moving through

four, five or even six levels or stages

before achieving the stated program

objectives.

8

This type of benchmarking is

a based primarily on analyzing website

content; any interactive features

(e-mail), quality and timeliness of

information and the capacity to

conduct online transactions. It provides

a convenient reference point for

developed and emerging nations, but it

presupposes a definitive level of

technical sophistication.

Prior to this study, developing countries

were omitted from much of the research

completed using this practice. We have

included a stage that reflects the

progress of developing countries.

In order to quantify the results, a

numerical scale ranging from 1 – 5 with

one representing an Emerging Presence

and five, Seamless or fully integrated,

was used. Each stage was furthered

analyzed for the presence of specific

features and content and measured by

intervals of .25.

The stages are a method for quantifying

progress. They are representative of the

government’s level of development

based primarily on the content and

deliverable services available through

official websites. This is not to suggest,

however, that in order to achieve

immediate success, a country must

follow this linear path, but rather reflects

the type of analysis and standards used

in 2001.

E-government programs are subjected

to a number of internal and external

factors. Technology and trained staff

obviously play a vital role in e-gov

development and influence how a

government will implement its program.

But it is the availability of resources that

dictate the goals of a particular

government. Ramping up from level one

to level two, level three, etc is, for now, a

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

12

consequence of the patterns of

contemporary program evolution. This

does allow policy planners a degree of

flexibility and creativity in program

development while still following the

game plan. Based on the availability of

a governments’ resources, an effective

program can be designed and

launched with the intent of being fully

transactional before ever going online.

Ramping up also allows the luxury of

utilizing a cost-effective practice of

testing through pilot programs.

The website research was conducted

during a three month period from May

to July and repeated from October to

December, 2001 in order to measure

progress and ensure accuracy. Each

Member State was examined using sites

available on the world wide web during

these periods. As stated earlier,

e-government development can be

swift and continuous, yet inchoate.

Change and improvement must be a

permanent part of the process if a

country is to achieve the stated goals

within its strategic framework and to

offer the most inclusive citizen-centric

approach. Unquestionably, many of the

UN Member States will have a different

look six, even three months from the

release of this report.

Progressive governments are upgrading

their sites regularly. Expanding the types

and quality of their online services and

improving their content daily in an

attempt to achieve the highest measure

of user satisfaction, administrative

efficiency and cost effectiveness. The

website analysis conducted as part of

this research is an appraisal taken at a

particular period in time --- a digital

photo of the global e-gov landscape

during 2001. (The stages of development

are however an important variable in

compiling the E-gov Index: Section 4)

For the purpose of the UN/ASPA survey,

a country’s online presence can be

categorized by one of five stages:

emerging; enhanced, interactive;

transactional; and fully integrated or

seamless.

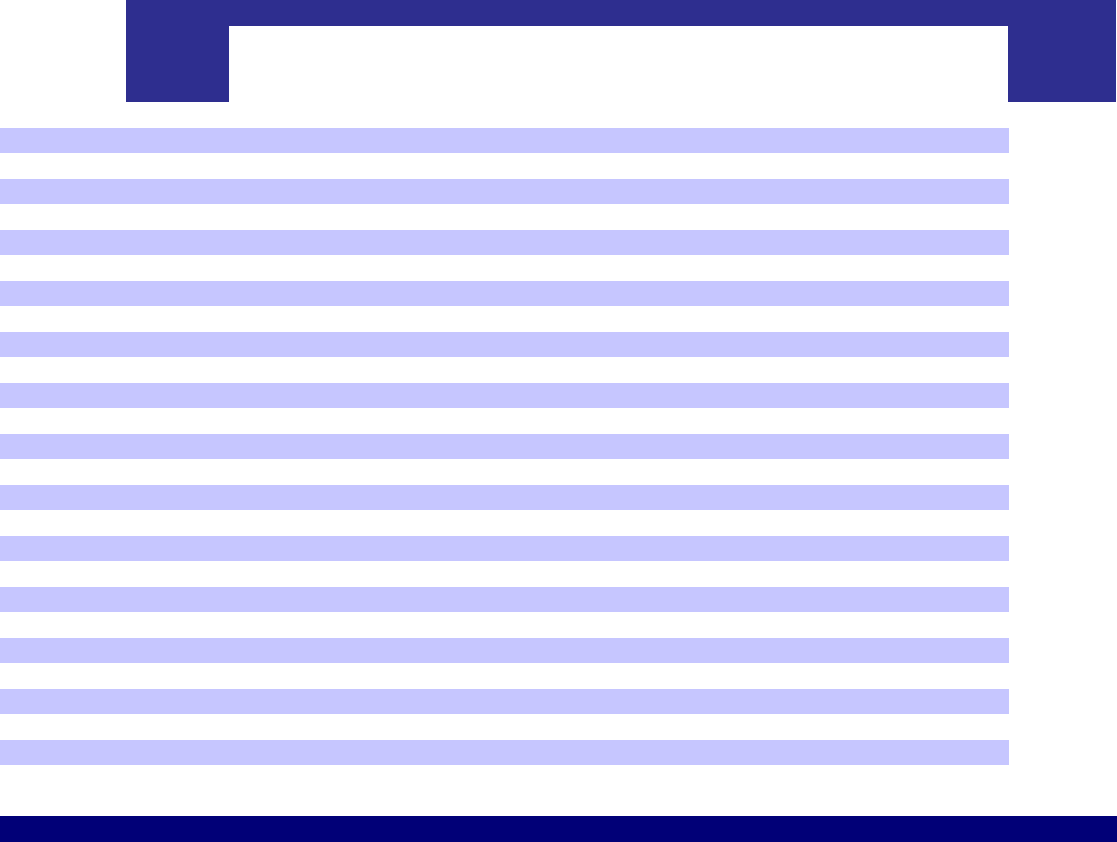

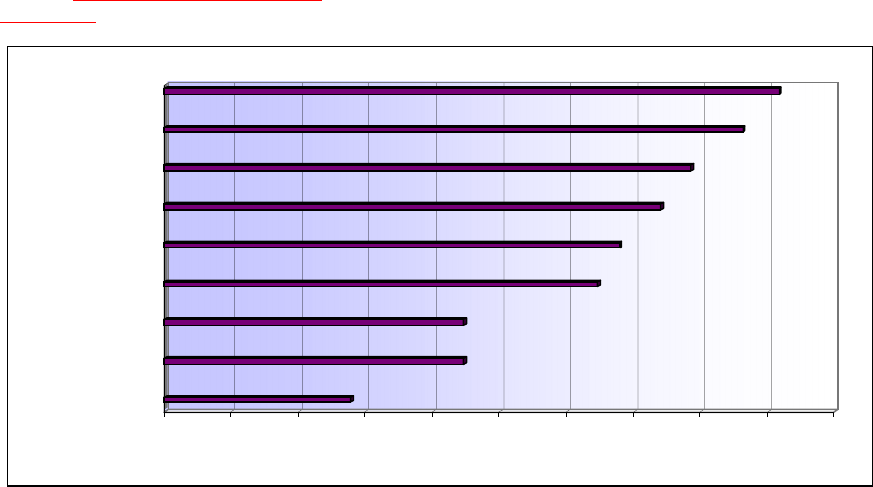

Chart 1: Country Stages for 2001

32

65

55

17

0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Emerging Enhanced Interactive Transactional Seamless

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

13

2.4. Country Progress

Emerging Presence:

A country commits to becoming an e-gov player. A formal but

limited web presence is established through a few independent government websites

which provide users with static organizational or political information. Sites may include

contact information (i.e telephone numbers and addresses of public officials). In rare

cases, special features like FAQs may be found.

Angola

Antigua & Barbuda

Botswana

Burundi

Cape Verde

Central African Rep.

Cyprus

Ethiopia

Fiji

Gabon

Gambia

Grenada

Guinea

Haiti

Lao PDR

Lesotho

Liberia

Madagascar

Malawi

Mali

Marshall Islands

Moldova

Myanmar

Niger

Qatar

St. Vincent & Gren.

Seychelles

Solomon Islands

Syria

Togo

Tonga

Yemen

Enhanced Presence:

A country’s online presence begins to expand as its number of

official websites increase. Content will consist more of dynamic and specialized

information that is frequently updated; sites will link to other official pages. Government

publications, legislation, newsletters are available. Search features, and e-mail addresses

are available. A site for the national or ruling government may also be present that links

the user to ministries or departments.

Albania

Algeria

Andora

Armenia

Azerbaijan

Bahamas

Bangladesh

Barbados

Belarus

Belieze

Benin

Bosnia / Herz.

Burhino Faso

Cambodia

Cameroon

Cote d’Ivoire

Croatia

Cuba

Dominica

Domincan Rep.

Ecuador

El Salvador

Georgia

Ghana

Guatemala

Guyana

Honduras

Indonesia

Iran

Iraq

Kazakhstan

Kenya

Kyrgystan

Liechtenstein

Macedonia

Maldives

Mauratania

Micronesia

Monaco

Mongolia

Mozambique

Namibia

Nepal

Nigeria

Oman

Papaua New Guinea

Rwanda

St. Kitts & Nevis

St. Lucia

Samoa

San Marino

Senegal

Sierre Leone

Swaziland

Tajikistan

Tanzania

Trinidad & Tobago

Turkmenistan

Uganda

Uzbekistan

Vanuatu

Viet Nam

Zambia

Zimbabwe

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

14

Interactive Presence: A country’s presence on the internet expands dramatically with

access to a wide range of government institutions and services. More sophisticated level

of formal interactions between citizens and service providers is present like e-mail and

post comments area. The capacity to search specialized databases and download

forms and applications or submit them is also available. The content and information is

regularly updated.

Argentina

Austria

Belgium

Bahrain

Bolivia

Brunei

Bulgaria

Chile

China

Colombia

Costa Rica

Czech Rep.

Denmark

Egypt

Estonia

Greece

Hungary

Iceland

India

Israel

Italy

Jamicia

Japan

Jordan

Kuwait

Latvia

Lebanon

Lithuania

Luxembourg

Malaysia

Malta

Mauritius

Morocco

Netherlands

Nicaragua

Pakistan

Panama

Paraguay

Peru

Phillippines

Poland

Portugal

Romania

Russian Federation

Saudi Arabia

Slovakia

Slovenia

South Africa

Sri Lanka

Sweden

Thailand

Turkey

Ukraine

United Arab Emirates

Uruguay

Venezuela

Yugoslavia

Transactional Presence:

Complete and secure transactions like obtaining visas,

passports, birth and death records, licenses, permits where a user can actually pay

online for a services pay parking fines, automobile registration fees, utility bills and taxes.

Digital signatures may be recognized in an effort to facilitate procurement and doing

business with the government. Secure sites and user passwords are also present.

Australia

Brazil

Canada

Finland

France

Germany

Ireland

Italy

Mexico

New Zealand

Norway

Portugal

Rep. Of Korea

Singapore

Spain

United Kingdom

United Statees

Seamless or fully integrated:

Capacity to instantly access any service in a "unified

package”. Ministerial/departmental/agency lines of demarcation are removed in

cyberspace. Services will be clustered along common needs.

No country surveyed has achieved this stage.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

15

S

ECTION

3:

A

NALYSIS OF

S

TAGES

3.1. Overview

Much of the current performance analysis

recognizes e-government development as

a linear progression, with countries moving

through four, five or even six levels or

stages of advancement. This form of

benchmarking is a based primarily on

analyzing website content, special

features, the quality and type of

information offered and the capacity to

conduct online transactions. It provides a

convenient reference point for developed

and emerging nations, but it presupposes

a certain level of sophistication.

Developing countries have, for the most

part, been omitted from many of the

studies completed using such a

benchmark. Our research recognizes the

efforts of least developed countries as

well. Therefore a stage that reflects their

efforts and progress was included.

However in practice, there exists three

functional levels of online service delivery

--- basic or publish, interactive and

transactional.

For most countries, gradually ramping up

to a more advanced level or stage of

development is a sound strategic

approach. Factors like technological

improvements, financial and human

resources, political commitment and

citizen participation, all contribute to how

quickly an e-government program

progresses.

There are, however, other factors that

should be noted as well. In certain

developing and emerging nations current

cultural and economic conditions may

justify e-gov programs that reflect the

immediate needs and technical capacity

of these societies. In such cases, attaining

level three or even level two may be a

realistic strategic development goal and a

sufficient online response. Consequently,

some programs may seem modest in

comparison to progressive or industrial

nations. It should be emphasized that the

primary objective of any e-government

program is to address the needs of

citizens. For a number of countries

attaining the enhanced or interactive

level may successfully fulfill this objective.

There are a finite number of services that

citizens and businesses can transact online

with national governments. Transactional

services vary depending upon the type of

political system. Highly centralized

governments will retain jurisdiction over

many transactions that decentralized and

federal systems will devolve to sub-

national levels. Driver’s license is one

example.

As noted in Section 2, the research

procedure selected for analyzing the

government websites was based on a

practices currently in use by national

governments, international organizations

and to a lesser degree, private sector

consulting firms.

The citizen-centric approach was the basis

for our analysis, therefore official websites

addressing sectors that were considered

to be most representative of services that

average citizens were most likely to seek

were evaluated. Five primary or target

sectors were analyzed: health, education,

labor or employment; social welfare and

services, and finance.

We further sought to Identify those aspects

of agency websites that are most

important for effective delivery of public

information and services. It is envisioned

that the results of this research will lead to

the development of a set of objective

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

16

performance measures for determining

the degree to which an agency website

effectively fulfills its mission of providing

information and services to the public.

Once accepted, these measures can be

tested and refined. Eventually a concise

set of internationally recognized

procedures that describe how these

performance measures can be refined

and ultimately applied could be

developed.

National government websites were

analyzed for their content and the type of

services available. The presence or

absence of specific features and

information factored into a country’s level

or official presence. The stages present a

straightforward and functional benchmark

of a national government’s online

presence and the sophistication of its

e-government program. Below is a brief

analysis of each stage.

3.2. Emerging Presence

Nearly all 32 countries, (16.8 of those

surveyed) at the

Emerging Presence Level,

are among the world’s least developed

nations with over half (18) in Sub-Sahara

Africa. Countries at this level averaged 3.9

official websites per government (in 2001,

the United States had over 31,000 Federal,

State and local sites) with content

consisting of predominately static and

insufficient information that is updated

infrequently, if at all. Most programs are in

their embryonic stage, providing few

interactive features like e-mail or

downloading forms. Actual online

services, as of this writing, are non-existent

for the countries at this level, and no

country offered an official website for any

of the five target sectors. Official

information for many of these countries is

predominately of a highly partisan,

political nature, i.e. bios and predictable

spin on the prime minister or the party in

power. The number of sites

disproportionately favor the political

parties over the service-provision or

administrative sites. There is little or no

information that would assist an individual

in accessing a specific public service. For

the most part, content could hardly be

described as citizen-centric.

Sectors with sites that are funded by

international organizations or outside

groups, or those promoting foreign

investment and tourism tend to be more

highly developed as a result of the

political and economic weight placed on

such issues. Some island nations, whose

primary source of economic activity is

tourism, have one or two sites promoting

the advantages of visiting or investing in

their country. Seychelles and Trinidad and

Tobago are such examples.

Obviously many of these countries are

among the poorest in the world, whose

limited resources are stretched well

beyond their finite capacities. National

priorities focus on basic survival issues.

However some countries have displayed

an intrinsic capacity for progress. Gabon’s

national government site

www.gabon.gov.ga

is an example of a

‘de facto’ single entry portal and allows

users to access 14 official national

government sites. Guiana and Botswana

are on the verge of ramping up to the

next level.

Most government sites do not have links to

all of the ministries and agencies, and

many have not been updated. The sites

typically are not used for administrative

purposes. For the countries at the

Emerging Presence level, e-government

program development is erratic and

disparate. There is little evidence of any

coordination or strategic planning within

ministries or departments, let alone,

national governments. However, this

condition may be reflective more of the

prioritization of needs rather than

organizational or political indifference.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

17

3.3. Enhanced Presence

Of the 65 countries (34.2%of the Member

States) with an

Enhanced Presence,

58%

are emerging or newly industrialized

economies, and, with the exception of

North America, are found in all

geographic regions. The average number

of sites for countries at this level is 18. There

are several cases of developing countries

like Cote’d Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Ghana

who are quickly succeeding in their

e-government programs as evidenced by

their commitment to content

improvement. There is still, however, very

little if any online representation of

ministries or departments dealing and with

social welfare, education or health issues.

The potential for more advanced

development in e-government is

apparent from some areas of Ghana's

site, however. Administrative guidelines

and regulations for obtaining a license to

export cocoa are clearly outlined in

extensive detail. Although the sites do not

allow the user to download the necessary

forms and applications, the information is

easily accessible and thorough. The

majority of CIS states including Georgia,

Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan are at the

Enhanced Presence level.

Presently, Nigeria's government web sites

are primarily for public affairs issues, with

very little dynamic information to the

citizens of Africa’s most populous nation.

Political agendas of the party in power are

obvious and appear on the forefront of

the site. In Nigeria's case, the unofficial

government web site is the Presidency.

Quotes about combating corruption and

allegiance to the presidency appear on

the page. The site itself does not provide

direct access to all ministries and legisla-

tive or judicial issues, including laws and

regulations or court decisions. This is not

uncommon among the countries at this

level, particularly those in Africa.

Nigeria has no ministries online, and

instead provides links to an array of

agencies and departments concerning

export regulations, ports authority, public

enterprises, corporate affairs, and

investment promotions. The focus is

clearly on promoting investment and

enhancing economic growth and

development. However, all sites or

information relating to education, social

services, health care or women and

children specifically are conspicuously

absent. This pattern of unbalanced

implementation is common at this level

and among developing countries.

Several Central American countries, such

as El Salvador, the Dominican Republic

and Guatemala, despite persistent

program obstacles (i.e. technological,

financial and human resources), are on

the verge of ramping up to the next level

of development. The Principalities of

Monaco and Liechtenstein each have

technically advanced websites, but their

content provides general information of a

public affairs nature promoting the

benefits of their countries.

The majority of nations at the Enhanced

Level show a greater degree of diversity in

their online content and the quality of

information. Although the content on most

official sites is predominantly political or

public affairs in nature, more than half the

countries (34), are developing a citizen-

centric approach with sites for at least one

of the targeted sectors. Forty-two

countries are upgrading their information

on a regular basis (at least once every two

weeks).

3.4. Interactive Presence

The Interactive Presence clearly

embodies the citizen-centric approach as

content, information and services

become what the people should expect

rather then what governments prefer to

offer.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

18

The delivery of information and services is

aimed at maximizing the importance of

the consumer by ensuring that ease of use

is priority. Portals are the preferred point of

entry; content is critically managed and

information is well balanced. Security and

privacy features are prominent among

sites.

At this stage, perhaps the most varied

profile of the Member States in terms of

national economic, political and social

conditions can be found. Of the 55

countries who offer interactive services,

20% are developing nations. The

remaining 80% are evenly divided

between newly emerging economies and

industrialized countries. Virtually all the

governments have demonstrated a strong

national commitment to a citizen-centric

e-government program and are well

advanced technically in their programs.

Only ten countries did not have websites

for all five target sectors. Each of the ten,

did however have a minimum of three

target sectors online.

Twelve countries (24%) at this stage

employ official single entry portals. Thirty-

one countries (62%) have official national

government sites which serve as de facto

portals, each linking the user with most

ministries, agencies departments as well as

government and elected officials. Of the

31 countries with official national

government sites, 24 link to the ministries of

the five targeted sectors: health,

education, labor, social welfare and

finance. Communicating with government

or elected officials is available through

e-mail and post comments features for

each of the 55 countries.

Information and content take on a

greater significance at this level and are

continuously updated. The sites are also

upgraded on a regular basis. Although

there is always a degree of political

information present in the content, it does

not dominate a country’s official

government web presence. In all 55

countries, users have the capacity to

download and request either documents

or forms from a specific ministry,

department, agency or unit. For a

number of countries like the Netherlands,

Sweden, Japan, ramping up to the

transactional level is only a matter of time,

Box 7: Single Entry Portals:

Several Excellent Examples

Australia www.fed.gov.au/KSP

Brazil . www.redegoverno.gov.br

Canada www.canada.gc.ca

Finland www.eduskunta.fi

France www.service-public.fr

Germany www.bundesregierung.de

Ireland www.irlgov.ie

Mexico www.precisa.gob.mx

New Zealand www.govt.nz

Norway www.norge.no

Rep. Of Korea www.kois.go.kr

Singapore www.gov.sg

Spain www.la-moncloa.es

United Kingdom www.ukonline.gov.uk

United States www.first

g

ov.

g

ov

Box 6: Single Entry Portals Are Standard

As a gateway or single point of entry to

government services, portals are

becoming the standard. In 2001, 36

countries provided easy access through

single entry portals. At the regional or

state level the number is much higher. All

26 of Brasil's states use this approach, as

do Germany's Landers, the majority of

Mexico's states and all 50 of the US states.

Serving as much more than a simple

gateway, however, a portal offers an

opportunity to reorient services around

the needs of citizens while consolidating

back office responsibilities. The United

States (www.firstgov.gov

) and the United

Kingdom (www.ukonline.gov

) are

excellent examples.

Eighty-four countries have an official

national government web page. These

sites can serve as de facto single entry

portals. National government websites

offer most of the features and links that

would be found on single entry portals.

Benchmarking E-government: A Global Perspective --- Assessing the UN Member States

United Nations - DPEPA ASPA

19

and several may have already achieved

the capacity by the release of this report.

Although online transactions are one of

the primary services that demonstrate

e-government’s utility, the point must be

reiterated, that despite daily advances in

information technologies and the

inescapable impact of globalization the

national economies for the large majority

of UN Member States are predominately

cashed based. Credit-cards, online

banking and other paperless forms of

e-commerce are, for the present,

available to those who have the means to

access such services. The necessity for

online transactions in many of these

societies may not be as great as the need

for reliable and practical information.

3.5. Transactional Presence

At the Transactional Presence level, a

country has fully demonstrated the

capacity for users to interact with the

government by purchasing publications or

other item, or utilizing a service like

obtaining a passport and paying for it

online with either a credit card, bank

debit or by some other electronic means.

At the completion of our online research,

17 countries offered complete

transactions online. (In should be

emphasized that in the case of online

transactions, the empirical evidence

sought required a closer examination of

national government websites. In some

cases transactional activity at the local

level has preceded national

governments.) Each of these countries is

a member of the OECD. All 17 use single

entry portals with the UK and Singapore

adopting the personal user ID approach.

All have very sophisticated citizen-centric

sites that offer the user access to

government organizations whose

existence most citizens may hardly be

aware of. The sites are undergoing

frequent revision and improvement to

achieve the maximum level of user

satisfaction. Content is regularly updated

to reflect the constant demand for current

and accurate information.

Box 8: Online Tax Transactions

Perhaps the most often cited example of e-

government’s utility is the capacity to pay

taxes online. Many countries now offer

electronic filing. Spain, has one of the most

sophisticated online taxation programs in

Europe.

But paying online is a different matter. France

has had an electronic payment program for

years and has successfully transitioned the

service to the web. But the program itself

requires several steps include gaining

permission to participate and securing an

electronic credit from the government and

the bank selected for payment and has yet

to achieve popularity with the French

citizens. Mexico has a similar program. But of

the 91 million people only 3.7 million have

access to the web. Payment of VAT,

personal and business taxes are at varying

stages of development.

From January 1 to April 15 the Internal

Revenue Service Website receives three

times as many hits as any other official US

government website. However the number

of taxpayers e-filing is disproportionately low.

There are a number of explanations, but the

most common is that despite the relative

ease and convenience, US taxpayers have

yet to gain a sense of trust for the process.

The IRS has projected that 45 million US

citizens will file electronically in 2002an

increase of 16 percent from 2001. The

remaining 95 million US taxpayers, however,

will continue to use the traditional approach

Online filing is gaining popularity among

South American countries. Collecting

payment however, is still in the pilot stage.

Chile for a example since instituting the