APPENDIX 4.3:

STREAM A3 ASSESSMENT REPORT

CONCEPTUAL

FRAMEWORK FOR

NONFINANCIAL

INFORMATION

STANDARD

SETTING

February 2021

22

DISCLAIMER

This appendix forms part of a series of seven documents, comprising the report and its appendices prepared by the European

Lab Project Task Force on preparatory work for the elaboration of possible EU non-financial reporting standards (PTF-NFRS),

for submission to the European Commission in response to a mandate including a request for technical advice dated 25 June

2020.

The contents of the PTF-NFRS report and its appendices are the sole responsibility of the PTF-NFRS. The European Lab

Steering Group Chair has assessed that appropriate quality control and due process had been observed to the extent possible

within the context of the relevant mandate and the timeframe allowed, and has approved the publication of the PTF-NFRS

report and its appendices. The PTF-NFRS report and its appendices do not represent the ocial views of EFRAG and are not

subject to approval by the EFRAG governance bodies: EFRAG General Assembly and the EFRAG Board; or the European Lab

Steering Group.

As regards the views expressed in the PTF-NFRS report and its appendices the following observations and clarifications

should be noted:

• the PTF-NFRS report taken as a whole reflects a very large consensus;

• it is understood that members of the PTF-NFRS are not expected to endorse each and every one of the 54 detailed

proposals in the PTF-NFRS report and may have dierent views on some of them;

• in addition the views expressed may not reflect the views of the organisations or entities to which individual PTF-NFRS

members may belong;

• the assessment work for the dierent project focus areas, presented in Appendices 4.1 to 4.6 to the PTF-NFRS report,

was the result of separate sub-groups of the PTF-NFRS, for which only peer review within the PTF-NFRS was performed.

Links are included in the PTF-NFRS report and its appendices to facilitate readers accessing the reference or source material

mentioned. All such links were active and functioning at the time of publication.

Questions about the European Lab and its projects can be submitted to [email protected].

© 2021 European Financial Reporting Advisory Group.

33

1 Based on the workplan that was presented and adopted by the PTF during its kick-o meeting on September 11, 2020

Stream A3 focused on the following assessment objectives:

a) review existing (explicit or implicit) frameworks and standards and summarise possible technical qualities expected

from NFI standards,

b) consider the organisation of the current non-financial topics (Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) and Human

Rights matters) in light of the NFRD and its revision, and alignment with other EU legislative acts (environmental

objectives of the taxonomy for instance),

c) assess the scope of reporting of existing frameworks and standards and identify perspectives on reporting of impacts

of the whole value chain,

d) address the dierent materiality perspectives and identify approaches based on existing methodologies to assess

materiality,

e) consider NFI more forward-looking rather than retrospective, documentation of objectives and scenario to report on

the company’s transition towards sustainable business model,

f) consider a standard structure composed of generic, sector and company specific issues and metrics,

g) analyse the range of metrics between absolute values, performance indicators and intensity ratios,

h) consider linkage with global policy priorities.

2 The assessment of each objective is structured as follows:

a) Definition and relevance of the topic;

b) Analysis; and

c) Key considerations for a potential EU NF Reporting Standards.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

44

TABLE OF CONTENTS

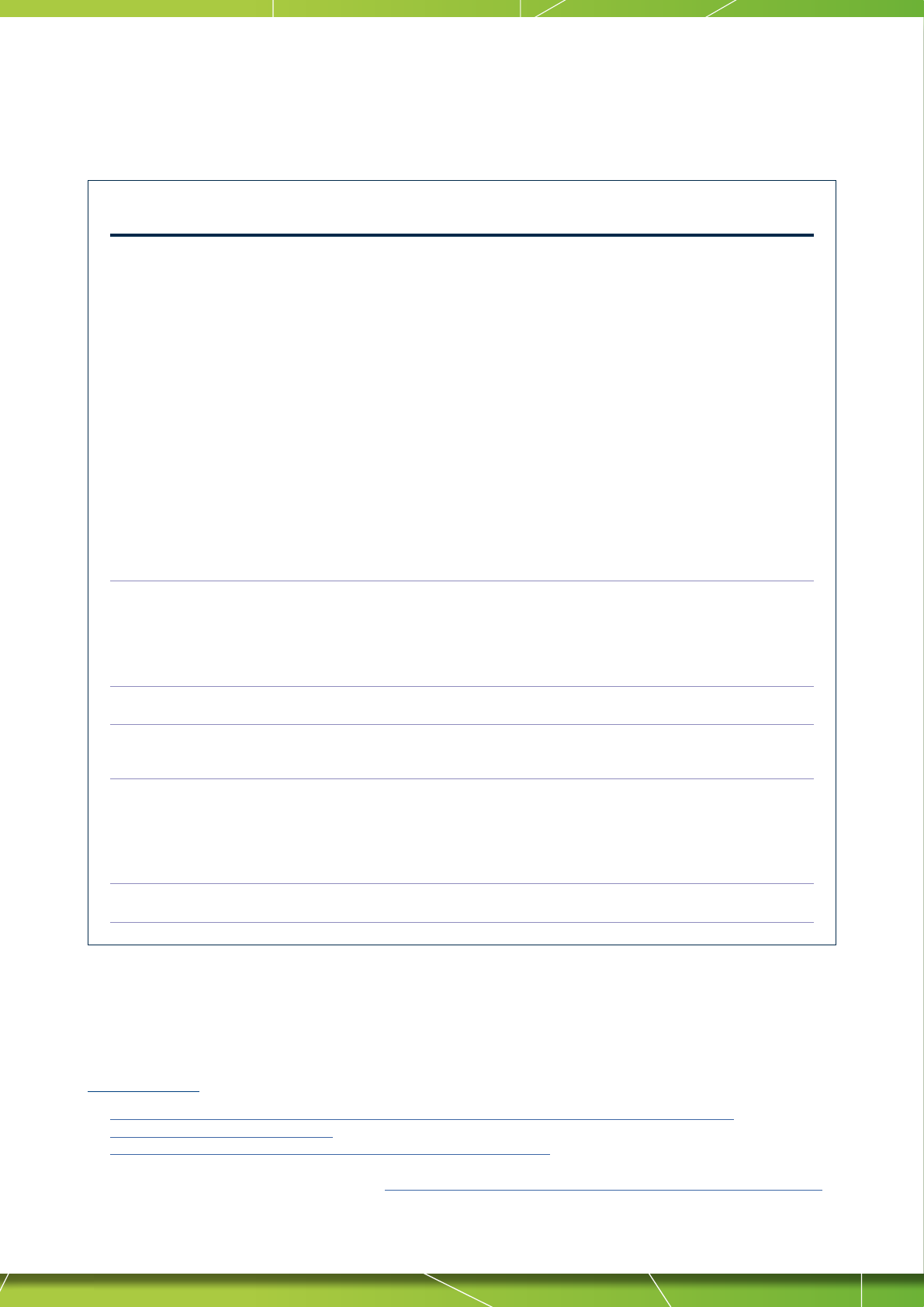

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES

DETAILED ANALYSIS OF THE CURRENT STATE OF PLAY

CATEGORISATION AND TAXONOMY

MATERIALITY

SCOPE OF REPORTING

FORWARDLOOKING INFORMATION AND TIME HORIZON

LEVEL OF APPLICATION

TYPES OF INFORMATION

REPORTING PRINCIPLES

LINK TO GLOBAL POLICY PRIORITIES

SALIENT ASSESSMENT POINTS

55

3 Based on the workplan that was presented and adopted by the PTF during its kick-o meeting on September 11, 2020

Stream A3 focused on the following assessment objectives:

a) review existing (explicit or implicit) frameworks and standards and summarise possible technical qualities expected

from NFI standards,

b) consider the organisation of the current non-financial topics (Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) and Human

Rights matters) in light of the NFRD and its revision, and alignment with other EU legislative acts (environmental

objectives of the taxonomy for instance),

c) assess the scope of reporting of existing frameworks and standards and identify perspectives on reporting of impacts

of the whole value chain,

d) address the dierent materiality perspectives and identify approaches based on existing methodologies to assess

materiality,

e) consider NFI more forward-looking rather than retrospective, documentation of objectives and scenario to report on

the company’s transition towards sustainable business model,

f) consider a standard structure composed of generic, sector and company specific issues and metrics,

g) analyse the range of metrics between absolute values, performance indicators and intensity ratios,

h) consider linkage with global policy priorities.

4 The assessment of each objective is structured as follows:

a) Definition and relevance of the topic;

b) Analysis; and

c) Key considerations for a potential EU NF Reporting Standards.

5 In the analysis phase, stream A3 developed questions that together paint a picture of the current state of play of non-

financial reporting related to the assessment objectives.

6 For each assessment objective, stream A3 assessed the NFRD and the following six existing frameworks and standards:

a) GRI Standards;

b) IIRC and the <IR> Framework;

c) SASB Standards;

d) United Nations Guiding Principles Reporting Framework;

e) EU Taxonomy; and

f) the TCFD recommendations.

7 These six frameworks and standards are considered by the European Commission (as evidenced by the reference in the

current NFRD itself and/or in the consultation document on its revision, as well as the mandate of the PTF) and the PTF

itself to be leading in non-financial reporting and are therefore included as core resources in the assessment.

INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES

66

8 Stream A3 has assessed additional frameworks, standards and guides when these resources deemed to be providing

additional insight in the specific question raised. For example, when addressing the assessment objective ‘linkage with

global policy priorities’, resources reflecting on these global policy priorities, such as the Sustainable Development

Goals (SDGs), were included in the assessment.

9 The additional resources assessed include, but are not limited to, the GHG Protocol, the Eco-Management and Audit

Scheme (EMAS), the Science Based Target initiative, the SDGs and the Future Fit Business Benchmark.

10 A summary of the key considerations for all the topics can be found at the end of the document as salient assessment

points.

77

CATEGORISATION AND TAXONOMY

Definition and relevance

11 Current non-financial information addresses a varied and (over time potentially) dynamic set of topics and sub-topics.

Certain categories of information may be prescribed per topic (e.g., policies, risks, targets, metrics).

12 The manner in which topics are defined and organised is relevant for how reporting entities structure and present

information and may influence how their materiality may be assessed in particular sectors and companies.

13 Article 19a) of the NFRD requires that non-financial statements contain information “relating to, as a minimum,

environmental, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery matters, including:

a) a brief description of the undertaking’s business model;

b) a description of the policies pursued by the undertaking in relation to those matters, including due diligence processes

implemented;

c) the outcome of those policies;

d) the principal risks related to those matters linked to the undertaking’s operations including, where relevant and

proportionate, its business relationships, products or services which are likely to cause adverse impacts in those

areas, and how the undertaking manages those risks;

e) non-financial key performance indicators relevant to the particular business.”

14 For each non-financial matter specified in the NFRD (i.e., environment, social and employee issues, human rights, anti-

corruption and bribery), the EC 2017 Non-Binding Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting explain what kind of relevant

information a company is expected to disclose.

15 In addition, for each category of non-financial information specified in the NFRD (i.e. business model, policies, outcomes,

risks and key performance indicators), the EC 2017 Non-Binding Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting provide

additional elements explaining what information companies should disclose.

16 The consultation on the NFRD revision asked whether companies should be required to disclose information about any

non-financial matters in addition to those already specified in the NFRD (i.e. environment, social and employee issues,

human rights, and anti-corruption and bribery). Approximately 50 dierent non-financial matters were mentioned. The

most frequent responses to this question were the Taxonomy Regulation, governance, and the supply chain; other

responses make reference to lobbying, animal welfare, and consumer matters, amongst many others

1

.

17 Given the demands of users following on from the NFRD consultation, there is a strong need for categorisation. Without

proper categorisation, a report containing the numerous non-financial matters identified may be unstructured and

dicult to read.

18 Some of the respondents such as users and preparers stressed the need for more concrete and detailed definitions of

what non-financial information should be disclosed. Some national standards setters even propose to make a description

of the content to be included in each category (environment, social and employee issues, human rights, anti-corruption

and bribery).

1 Summary Report of the Public Consultation on the Review of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (2020)

DETAILED ANALYSIS OF

THE CURRENT STATE OF PLAY

88

19 Moreover, some preparers state that governance matters could be treated more broadly, without being limited to bribery

and anti-corruption matters only. The scope of the governance matters could cover other topics relevant to business

ethics and business conduct.

20 In addition, the consultation asked if companies should be required to disclose information about additional categories of

non-financial information in addition to those already specified in the NFRD (i.e. business model, policies, outcomes, risks

and key performance indicators). Approximately 240 dierent categories were mentioned. The most frequent category

submitted by respondents is targets and companies’ progress towards them. Other frequently mentioned categories

were climate scenario analysis, forward-looking information, contribution to the UN Sustainable Development Goals,

sustainability strategy, materiality assessment, the link between board remuneration and sustainability performance,

and information aligned with the Taxonomy Regulation and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation.

21 However, some preparers are concerned about a possible expansion of non-financial reporting when additional topics

are included. They prefer not to expand the amount of requested information but to harmonise the existing requirements

among Member States and stop the fragmentation of dierent frameworks.

22 Key question in PTF’s analysis of the categorisation and taxonomy is: What are the dierent ways in which non-financial

information can be organised and categorised and how can this be captured in a conceptual framework?

Analysis

What high level categories do existing initiatives use and based on what rationale (if that is expressed)?

23 High-level categorisations (may be dubbed ‘themes’, ‘series’, ‘pillars’, ‘capitals’ etc.) are generally variations of E, S and

G (the broader concepts of sustainability) and are regularly expanded with areas that may well be part of ESG but are

often separately presented as main categorisations: such as climate change, human rights, strategy, business model,

tax, corruption, or general ‘economics’.

24 Some key standards/frameworks address one dimension of sustainability reporting (e.g. UNGP Reporting Framework

for human rights, EU Taxonomy for the environment, TCFD for climate) but still with category-specific subdivisions.

25 Within the main analysed frameworks and standards:

a) NFRD requires disclosure for each of the topics: Environmental, Social and employee matters, Respect for human

rights, Anti-corruption and bribery matters. In particular,

(i) Environmental matters should contain details of the current and foreseeable impacts of the undertaking’s

operations on the environment, and, as appropriate, on health and safety, the use of renewable and/or non-

renewable energy, greenhouse gas emissions, water use and air pollution;

(ii) As regards Social and employee-related matters, the information provided in the statement may concern

the actions taken to ensure gender equality, implementation of fundamental conventions of the ILO, working

conditions, social dialogue, respect for the right of workers to be informed and consulted, respect for trade

union rights, health and safety at work and dialogue with local communities, and/or the actions taken to ensure

protection and development of those communities;

(iii) Concerning Respect for human rights, non-financial statement could include information on the prevention of

human rights abuses;

(iv) With regards to Anti-corruption and bribery matters, non-financial statements could include a description of the

instruments in place to fight corruption and bribery.

99

b) The GRI Standards are divided into Topics, 200, 300, and 400 series

2

, which include numerous topic-specific

Standards, that guide companies in reporting information on impacts related to economic, environmental, and social

topics. However, to prepare a sustainability report in accordance with the GRI Standards, an organisation has to apply

also GRI 102: General Disclosures that require companies to disclose specific information about their business model,

strategy, governance and risk management.

c) The <IR> Framework

3

aims to provide insight about the resources and relationships used and aected by an

organisation – these are collectively referred to as the capitals. The capitals are stocks of value that are increased,

decreased or transformed through the activities and outputs of the organisation. They are categorised in this

Framework as: financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural capital, although

organisations preparing an integrated report are not required to adopt this categorisation or to structure their report

along the lines of the capitals. Concerning the definition of capitals:

(i) Financial capital is described as the pool of funds that is available to an organisation for use in the production

of goods and services, and obtained through financing (such as debt, equity or grants) or generated through

operations or investments.

(ii) Manufactured capital is the set of manufactured physical objects that are available to an organisation for use in

the production of goods and services (buildings, equipment, infrastructure).

(iii) Intellectual capital includes intellectual property and the so-called organisational capital.

(iv) Human capital is represented by people’s competencies, capabilities and experience, and their motivations to

innovate.

(v) Social and relationship capital is the set of institutions and relationships within and between communities, groups

of stakeholders and other networks, and the ability to share information to enhance individual and collective

well-being.

(vi) Natural capital represents all the environmental resources and processes that provide goods or services that

support the past, current or future prosperity of an organisation.

d) SASB sustainability topics

4

are organised under five broad sustainability dimensions: Environment, Social Capital,

Human Capital, Business Model and Innovation, Leadership and Governance.

(i) The Environment dimension includes environmental impacts.

(ii) The Social dimension relates to the expectation that a business will contribute to society in return for a social

license to operate.

(iii) The Human dimension addresses the management of a company’s human resources as key assets to delivering

long-term value.

(iv) The dimension of Business Model and Innovation addresses the integration of environmental, human, and social

issues in a company’s value-creation process.

(v) The dimension Leadership and Governance involves the management of issues that are inherent to the business

model or common practice in the industry and that are in potential conflict with the interest of broader stakeholder

groups, and therefore create a potential liability or a limitation or removal of a license to operate.

(vi) These 5 sustainability dimensions are divided into 30 General Issue Categories (that represent broad

sustainability-related business issues). General Issue Categories allow for cross-industry comparisons of closely

2 The GRI 200, 300 and 400 series include topic-specific standards. To prepare a sustainability report in accordance with the GRI Standards, an organisation

applies the Reporting Principles for defining report content from GRI 101: Foundation to identify its material economic, environmental, and/or social topics.

These material topics determine which topic-specific Standards the organisation uses to prepare its sustainability report (GRI 101: Foundation 2016)

3 IIRC, The International <IR> Framework (2013)

4 SASB Conceptual Framework (2017)

1010

related industry-specific Disclosure Topics. The disclosure topics included in SASB’s industry-specific standards

are a sub-set of this universe of sustainability issues, tailored to the industry’s specific context.

e) TCFD

5

addresses one dimension of sustainability reporting but does include category-specific subdivisions, which

are discussed in key question 2. At the moment, the EU Taxonomy also addresses one dimension, although in future

Regulatory Technical Standards, other ecological and social issues will be addressed.

Moreover, within the additional resources analysed:

f) The WEF IBC Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism Report (2020) tries to overcome fragmentation and to drive global

alignment, and guides companies to report in a consistent and more comparable way on key dimensions of sustainable

value. The initiative is divided into four pillars: Principles of Governance, Planet, People and Prosperity. Under each

one of the four pillars several main themes can be found, which include the core metrics and disclosures derived from

various existing frameworks;

g) ISO 26000 is divided in 7 core subjects: organisational governance, human rights, labour practices, environment, fair

operating practices, consumer issues and community involvement and development. Moreover subjects 2-7 include

in total 36 sub-issues

26 Most of the standards and frameworks require also specific key reporting elements (e.g. policy, outcomes, impacts, risks,

targets and progress against targets) per category.

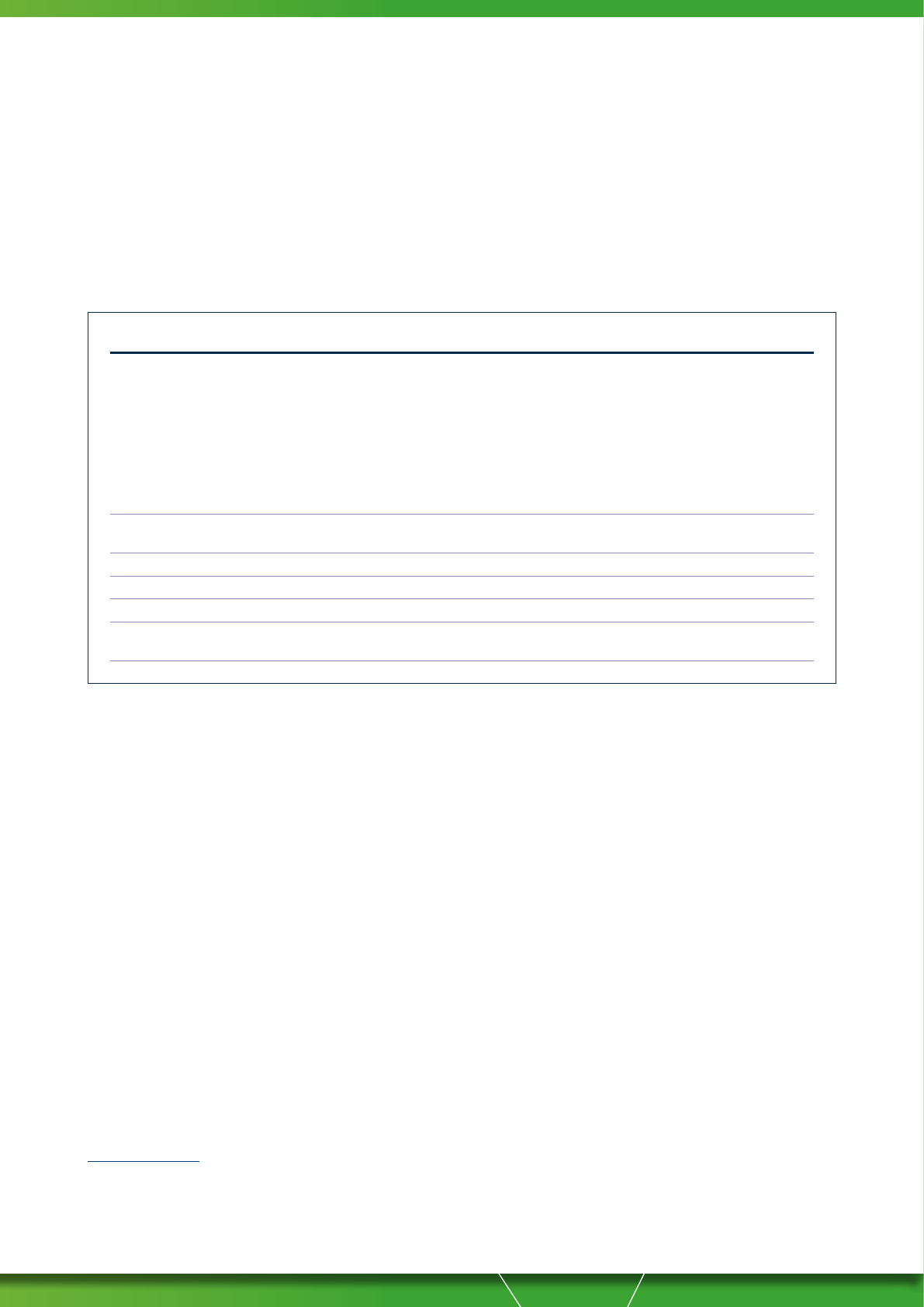

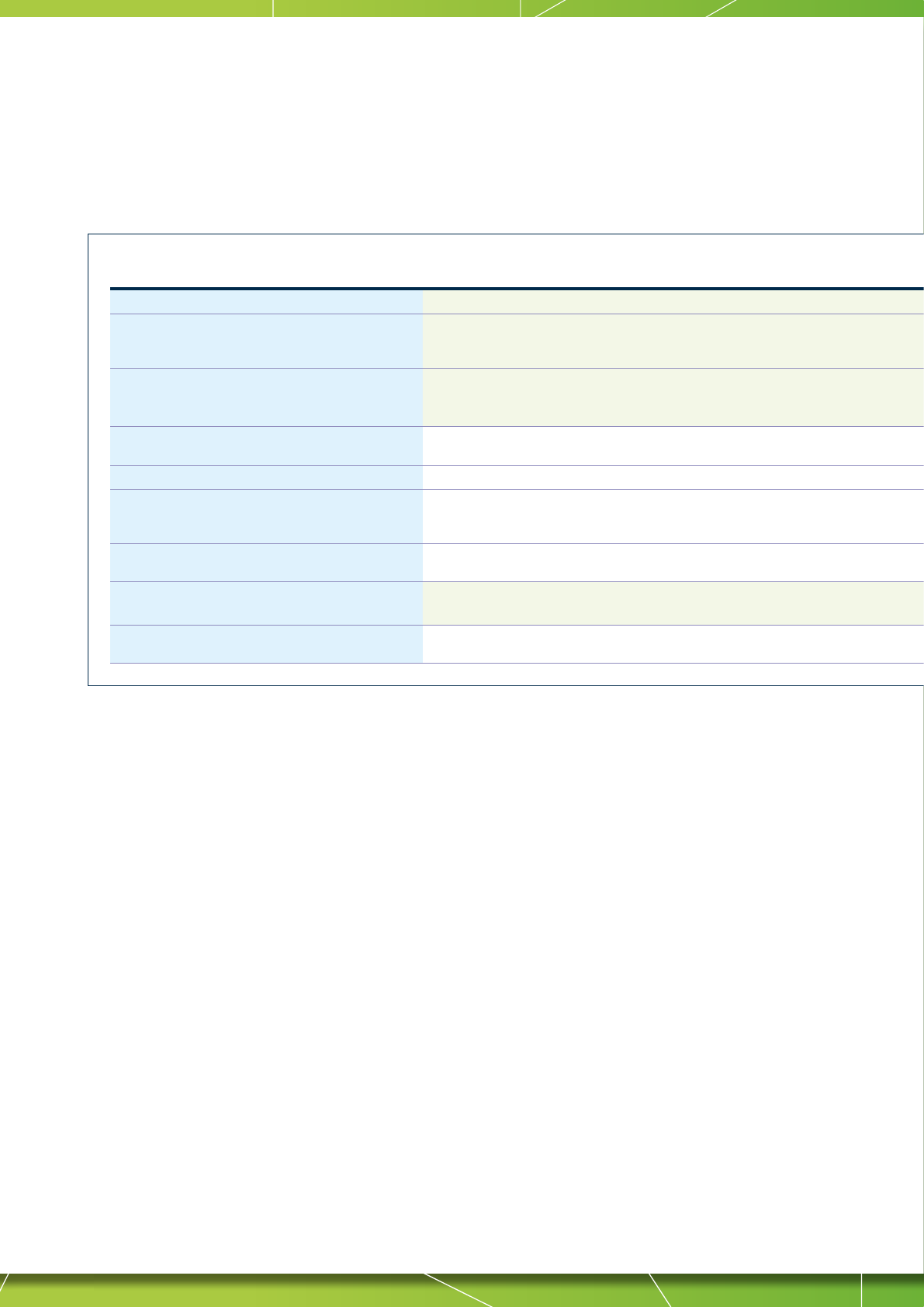

Framework/

standard

Sustainability dimensions mentioned

by the framework/standard Information required

Division

Environment

Social/ People

Governance

Economics

(including Profit)

Anti- corruption

Business model

Risks

Strategy/Policy

Performance

Main analysed frameworks/standards

GRI 3 Topics

6

IIRC 6 Capitals

7

SASB 5 Dimensions

8

UNGP RF

9

-

Taxonomy Regulation 6 objectives

10

TCFD

11

-

Additional resources considered

ISO 26000 7 core subjects

12

WEF IBC 4 Pillars

13

5 Final Report – Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (2017)

6 https://www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards/gri-standards-english-language/

7 IIRC, The International <IR> Framework (2013)

8 SASB Conceptual Framework (2017)

9 UN Guiding Principles Reporting Framework (2015)

10 Regulation (EU) 2020/852, article 9

11 Final Report – Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (2017)

12 ISO 26000:2010 Guidance on social responsibility

13 WEF “Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism: Towards Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation White Paper” (2020), p.12

1111

27 Rationale in terms of categorisation is generally not made explicit, most of the frameworks/standards adopt the

widespread categorisation that refers to the ESG dimensions but without a clear explanation of the reason behind this

choice. From the examples below it becomes clear the rationale usually covers the ‘why’ of sustainability reporting

rather than the rationale for specific categorisations within a standard or framework

28 Within the main analysed frameworks/standards:

a) GRI sees sustainability reporting as an organisation’s practice of reporting publicly on its economic, environmental, and/

or social impacts, and hence its contributions – positive or negative – towards the goal of sustainable development.

Through this process, an organisation identifies its significant impacts on the economy, the environment, and/or

society and discloses them in accordance with a globally accepted standard. The underlying question of sustainability

reporting is how an organisation contributes, or aims to contribute in the future, to the improvement or deterioration

of economic, environmental, and social conditions at the local, regional, or global level. Therefore, the aim is to

present the organisation’s performance in relation to broader concepts of sustainability. This involves examining its

performance in the context of the limits and demands placed on economic, environmental or social resources, at the

sectoral, local, regional, or global level. This concept is often articulated with respect to the environment, in terms of

global limits on resources and pollution levels. But it is also relevant with respect to social and economic objectives,

such as national or international socioeconomic and sustainable development goals.

b) IIRC, through Integrated Reporting, wants to promote a more cohesive and ecient approach to corporate reporting

and aims to improve the quality of information available to providers of financial capital to enable a more ecient and

productive allocation of capital. The primary purpose of an integrated report is to explain to providers of financial

capital how an organisation creates value over time. The primary reasons for including the capitals in this Framework

are to serve as part of the theoretical underpinning for the concept of value creation and as a guideline for ensuring

organisations consider all the forms of capital they use or aect

14

.

29 Moreover, within the additional resources analysed the following rationales are mentioned:

a) For WEF IBC Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism Report, pillars are aligned with essential elements of SDGs; themes

are derived from a review of existing standards and considered to be most important to society, planet and economy;

five criteria are used for metric prioritisation

15

.

b) German Sustainability Code is an entry point to sustainability reporting, its rational is to act as an easily implementable

and structured framework for NFRD and UNGP.

c) For EMAS, the rationale is to provide the public and other interested parties with information on compliance and

environmental performance and ensure relevance and comparability of reported data.

d) For the Sustainable Development Goals Disclosure (SDGD) Recommendations, no specific rationale is given, other

than convergence with existing standards and frameworks (the SDGD-recommendations attempt to take exiting

reporting along IR, GRI and TCFD-lines to the level of SDG risks and opportunities; for ease of application / adoption

it builds on existing reporting practices).

30 The connection of main categories to financial reporting is often left implicit (e.g. NFRD or GRI 100). The Economic series

of GRI is fairly general, with a focus on economic impact (inside-out perspective), and appears to have some diculty

positioning the information suggested compared to information in other reports (such as the management report, that

has an outside-in perspective, and is focus on financial implications).

14 The Background Paper for <IR> explain how financial and manufactured capitals are the ones organisations most commonly report on. IR takes a broader

view by also considering intellectual, social and relationship, and human capitals (all of which are linked to the activities of humans) and natural capital (which

provides the environment in which the other capitals sit).

15 The following criteria were used to filter and prioritise all themes and metrics: 1. Consistency with existing frameworks and standards 2. Materiality to long-

term value creation 3. Extent of actionability 4. Universality across industries and business models 5. Monitoring feasibility of reporting

1212

Where are sub issues/topics allocated within categories?

31 High-level categories are usually subdivided into more granular sub-topics, with varying degrees of granularity.

32 Frameworks can refer to other frameworks for a more granular subdivision, as in the case of IIRC that refers to GRI

Standards, or the SDGs Recommendations that assume the application of GRI, UNGC and the work of the Impact

Management Project.

16 GRI 101, Foundation, p. 3

17 Capitals Bankground paper for <IR>, p.17

18 SASB Conceptual Framework (2017), p.2-3

Framework/

standard Allocation of topics/sub-issues within categories

Main analysed frameworks/standards

GRI The GRI disclosures are divided into sub-topics under the main topics (Economic, Environment, Social)

with a high level of granularity of sub-topics.

• Economics – GRI 200 series. GRI 201: Economic Performance, GRI 202 Market presence, GRI 203

Indirect economic impact, GRI 204 Procurement practices, GRI 205 Anti-corruption, GRI 206 Anti-

competitive behaviour, GRI 207 TAX (new)

• Environment – GRI 301: Materials, GRI 302: Energy, GRI 303: Water and euents, GRI 304:

Biodiversity, GRI 305: Emissions, GRI 306: Waste, GRI 307: Environmental compliance, GRI 308:

Supplier environmental assessment

• Social – GRI 401: Employment, GRI 402 Labour management relations, GRI 403 Occupational health

and safety, GRI 404 Training and education, GRI 405 Diversity and equal opportunity, GRI 406 Non-

discrimination, GRI 407 Freedom of association and collective bargaining, GRI 408 Child labour, GRI

409 Forced or compulsory labour, GRI 410 Security practices, GRI 411 Rights of indigenous peoples,

GRI 412 Human rights assessment, GRI 413 Local communities, GRI 414 Supplier social assessment,

GRI 415 Public policy, GRI 416 Customer health and safety, GRI 417 Marketing and labelling, GRI 418

Customer privacy, GRI 419 Socioeconomic compliance

16

IIRC <IR> Framework does not foresee specific KPIs to disclose on the six capitals, but only provides their

content element. In the document “CAPITALS. Background paper for <IR>”, a correlation table is

present-ed crossing GRI sustainability topics with a selection of the <IR> Framework capitals (natural,

social and relationship, human).

17

SASB The 5 broad sustainability dimensions are divided into the following sub-topics (26 sustainability-

related business issues/general issue cate-gories):

• Environment. This dimension includes 6 general issue categories: GHG Emissions, Air Quality,

Energy Management, Water & Wastewater Management, Waste & Hazardous Materials

Management, Ecological Impacts.

• Social Capital. This dimension includes 7 general issue categories: Human Rights & Community

Relations, Data Security, Customer Privacy, Product Quality and Safety, Customer Welfare, Selling

Practices & Product Labelling.

• Human Capital. This dimension includes 3 general issue categories: Labour practices, Employee

Health and Safety, Employee En-gagement, Diversity & Inclusion

• Business Model and Innovation. This dimension includes 5 general issue categories: Product

Design & Lifecycle Management, Busi-ness Model Resilience, Supply Chain Management, Materials

Sourcing & Eciency, Physical Impacts of Climate Change.

• Leadership and Governance. This dimension includes 5 general issue categories: Business Ethics,

Competitive Behaviour, Management of Legal & Regulatory Environment, Critical Incident Risk

Management, Systemic Risk Management

18

1313

19 UN Guiding Principles Reporting Framework

20 Regulation (EU) 2020/852, article 9

21 www.nachhaltigkeitsrat.de/en/projects/the-sustainability-code

22 Greenhouse Gas Protocol, A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard Revised edition

23 Natural Capital Coalition, Nature Capital Protocol (2016)

24 Sustainable Development Goals Dislcosure (SDGD) Recommendations (2020)

Framework/

standard Allocation of topics/sub-issues within categories

UNGP RF The UN Guiding Principles Reporting Framework focuses companies’ reporting on their salient human

rights issues. Companies need to address 8 overarching questions and 4 information requirements

about the definition of the focus of the reporting (i.e. Statement of salient issues, Determination of

salient issues, Choice of focal geographies, Additional severe impacts) in order to meet the minimum

threshold to say that it has applied the UN Guiding Principles Reporting Framework.

Contents falls in three parts:

• Governance – policy commitment and embedding of respect of hu-man rights

• Defining the focus of reporting (salient issues/severe impacts)

• Management of salient human rights issues (specific policies, stakeholder engagement, assessing

impact, integrating findings and taking action, tracking performance, remediation)

19

Taxonomy

Regulation

The EU taxonomy identifies the following 6 environmental objectives on which needs to be reported

(article 9):

• climate change mitigation;

• climate change adaptation;

• the sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources;

• the transition to a circular economy;

• pollution prevention and control;

• the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems

For each objective, core reporting elements are turnover and CAPEX and OPEX (article 8).

The Taxonomy will be further developed to incorporate also Social objectives, in addition to

environmental objectives, to identify substantial contributions in addition to minimum safeguards.

20

Additional resources

German

Sustainability

Code

20 reporting criteria in four categories. Each of the 20 reporting criteria is supported by a checklist of

specific disclosures requirements, also including KPIs from GRI or EFFAS. For some criteria additional

(voluntarily applicable) disclosures that aim for compatibility with the NFRD and UNGP.

• Strategy: strategic analysis and action, materiality, objectives, depth of value chain;

• Process management: responsibility, rules and processes, control, incentive schemes, stakeholder

engagement, innovation and product management

• Environment: Usage of natural resources, resource management, climate-relevant emissions

• Society: employment rights, equal opportunities, qualifications, human rights, corporate citizenship,

political influence, compliance with regulations and policies

21

GHG Protocol GHG Protocol applies to greenhouse gas emissions which are usually attributed to the “E” pillar. GHG

emissions are attributed to 3 scopes (top categorisation level), and emissions within scope 3 are

attributed to 15 categories (8 for upstream sources and 7 for downstream sources). The categorisation

is one-dimensional.

22

Natural Capital

Protocol

Content is focused on natural capital, broadly defined as the stock of renewable and non-renewable

natural resources on earth (e.g., plants, animals, air, water, soils, minerals) that combine to yield a flow

of benefits or “services” to people. Impact drivers can be classified along the lines of main categories,

such as water use, ecosystem use, GHG emissions, pollutants, or waste. These categories are not

prescribed.

23

SDGD

Recommendations

Not specified. With regard to specific indicators etc. the SDGD recom-mendations assume application

of GRI, UNGC and the work of the Im-pact Management Project.

24

1414

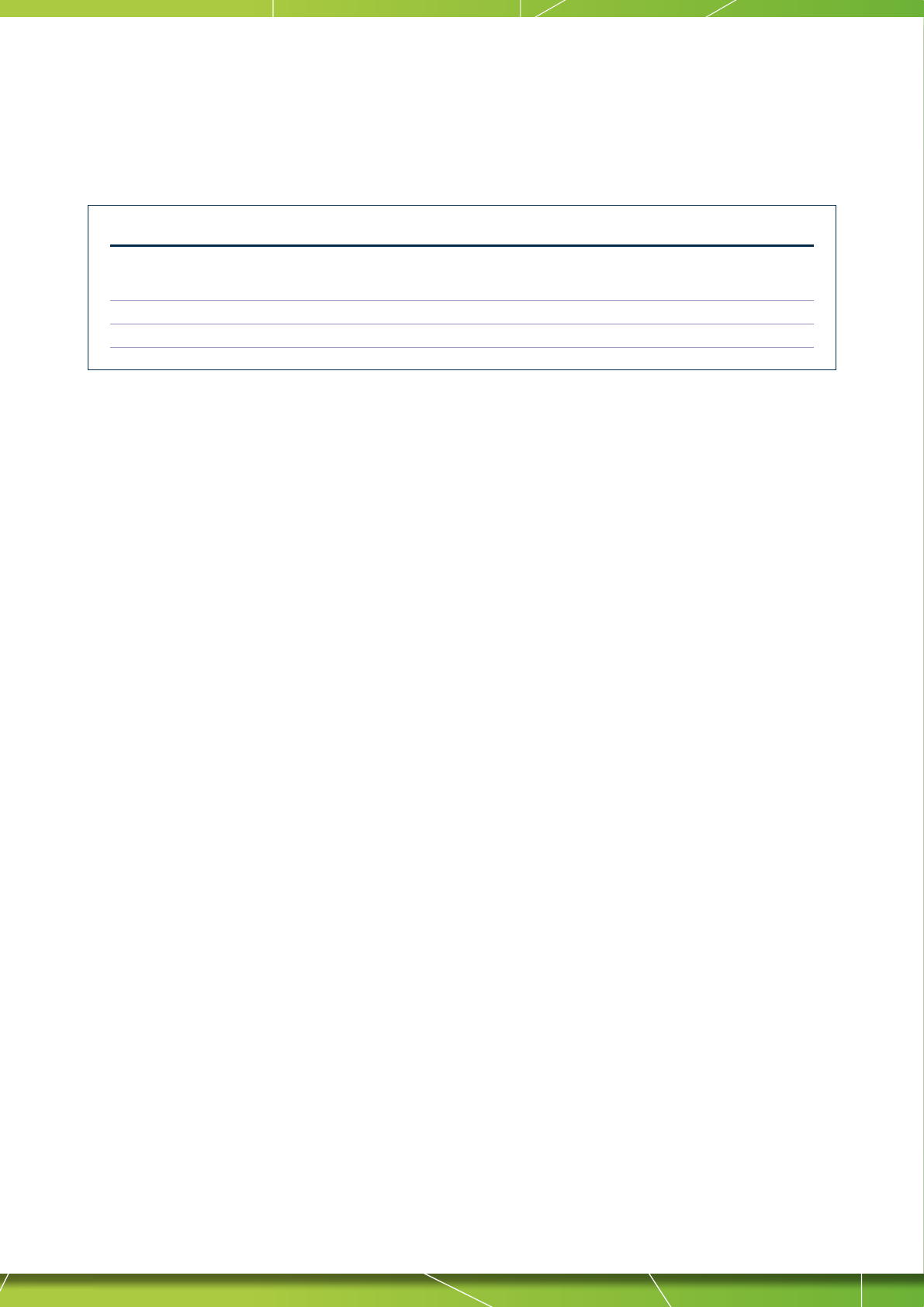

Summary of sub allocations:

First level Second level Third level

Main analysed frameworks/standards

GRI 3 Topics 34 Topic Specific Disclosures

IIRC 6 Capitals Reference to GRI

for 3 Capitals

-

SASB 5 Dimensions 26 Sustainability-Related

Business Issues

77 Industries with

specific metrics

UNGP Reporting

Framework

- 8 Overarching

Questions and 23

Supporting Questions

Suggestions for

relevant information

for each Question

Taxonomy Regulation - 6 Objectives 3 KPIs

Additional resources

German SC 4 Categories 20 Reporting Criteria Specific Disclosures

Requirements

GHG Protocol - 3 Scopes For Scope 3, 15 Categories

SDG - Reference to GRI

and UNGC

-

WEF 4 Pillars 21 Core Metrics

and 34 Expanded

Universal Metrics

-

33 Categorisation can be also divided in another dimension, based on the sector. Some frameworks/standards adopt both

dimensions (over-arching issues divided into a more granular subdivision and sector specific) while other consider only

one. Within the frameworks and standards analysed there is also the possibility of using a specific taxonomy for sector

specific reporting (NACE, SICS)

26

. Within the core analysed frameworks/standards:

a) SASB’s Sustainable Industry Classification System™ (SICS™) groups industries with similar business models and

sustainability impacts. The SASB focuses on 11 sectors divided to 77 industries).

25 WEF, Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism: Towards Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation White Paper (2020)

26 Other industry classifications that are available on the market are the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®) and the Industry Classification

Benchmark (ICB).

Framework/

standard Allocation of topics/sub-issues within categories

WEF IBC

Measuring

Stakeholder

Capitalism Report

(2020)

Up to seven sub-themes under each pillar, high granularity:

• Governance: purpose, governance body, stakeholder engage-ment, ethical behaviour, risk and

opportunity oversight

• Planet: climate change, nature loss, freshwater availability, air pollu-tion, water pollution, solid waste,

resource availability

• People: Dignity and equality, health and well-being, skills for the future

• Prosperity: employment and wealth generation, innovation for products and services, community

and social vitality

Two ambition levels: 21 core metrics and 34 expanded universal metrics

No dierentiation between content elements (strategy, risks, targets etc.) and ESG-related KPI

25

1515

b) Concerning the EU Taxonomy, the TEG recommendations are structured around the EU’s NACE

27

(Statistical

classification of economic activities in the European Community) industry classification system, and the TEG has

set technical screening criteria for economic activities within priority macro-sectors. This classification system was

selected for its compatibility with EU Member State and international statistical frameworks and for its broad coverage

of the economy.

34 Moreover, within additional resources analysed:

a) Organisations that comply with EMAS-requirements are publicly registered. Classification system used is NACE.

b) nFIS (Polish Non-Financial Information Standard) Annex 2 uses sector and macro sector classification used by the

Warsaw Stock Exchange, which is in turn a variation of NACE.

Key considerations for a potential EU Sustainable Standard

35 The categorisation, both in terms of high-level topics and of subdivisions, has the potential to be an important structuring

element, guiding how reporting entities structure and present information.

36 Reporting standard benefits from a clear structure, with a high-level definition of overarching categories able to cover

the broader sustainability themes. The high-level categorisation might, in fact, serve as an umbrella for a more granular

subdivision, where dierent topics can be allocated and, eventually, progressively updated in line with the evolving

scenario and the consequent emerging issues. A clear and well-defined structure can ease the application of a sectoral

approach and/or various types of information (e.g. strategy, risks, performance) to each category. Moreover, it can

support the future development of a data taxonomy for the necessary digitisation of sustainability information.

37 This current assessment tends to prove that common practice of E, S and G high-level categorisation could provide

a certain consensus, being recognised as a clear and eective division for some users and preparers. This type of

categorisation is often used by financial market participants, although it resembles the categorisation of people, planet,

profit, also often used for sustainability reporting. One potential drawback is that the ESG categorisation might be

too narrow and not able to include a wider range of cross-cutting issues (e.g., bribery, anti-corruption, tax, corporate

advocacy).

38 How to reflect the interrelation of dierent topics is a key item in order to obtain a relevant positioning of all topics. (i.e.,

categorisation should take into consideration the fact that some topics residing clearly within the broad sustainability

field are overarching and cannot be easily contained in one high-level area) For example, climate change issues are

clearly part of the environmental topic, but also have relevance for society, human rights and governance topics.

39 The analysis demonstrates that a clarification of labels or definitions used for each category is needed and on which

topics these categories are based. Changing the vocabulary can help facilitate a change in focus and priority.

40 Specifically, clarity is needed that human rights encompasses all forms of impacts on people that rise to the level of

undermining their basic dignity and equality. It includes categories such as health & safety and diversity & inclusion.

41 Much attention has to be brought to the key term social. The language of social tends to dehumanize by aggregating

issues into a broader category where attention to vulnerable people can be easily lost or traded o against benefits

for others. Often social is also used to reflect positive philanthropic contributions by the company to communities (e.g.,

donations or volunteering) to the exclusion of impacts on people. Comparative analysis between the terms social and

people is to be considered. In this context it is also relevant to note that GRI’s draft revised Universal Standards social

has been replaced by people.

42 From the analysis of the main frameworks/standards it also appears that the categorisations adopted by the frameworks

seem to lack a covering of economic aspects closely related to their impact on society and the planet (for example Tax

responsibility or avoidance, anti-corruption and bribery, public subsidies) and do not fully consider the interrelation

between financial information already provided by companies and sustainability information.

27 NACE stands for Nomenclature des Activités Économiques dans la Communauté Européenne

1616

43 For environmental issues, the EU taxonomy is commonly accepted and is a logical choice to structure environmental

subdivisions across the six environmental objectives identified.

MATERIALITY

Definition and relevance

44 The concept of materiality has been considered by the Workstream as the approach for inclusion and prioritisation of

specific information in financial, non-financial or sustainability reporting, considering the needs of and expectations from

the stakeholders of an organisation. The International Federation of Accountants observes that ‘materiality works as a

filter through which management sifts information.’ Materiality is therefore key for ensuring the relevance of reported

information, not only to direct report users but also to a broader set of stakeholders.

45 Art. 2 (16) of the Accounting Directive

28

defines materiality from a financial standpoint, that is the ‘status of information

where its omission or misstatement could reasonably be expected to influence decisions that users make on the basis

of the financial statements of the undertaking’.

46 Art. 19a (1) of the NFRD requires, ‘information to the extent necessary for an understanding of the undertaking’s

development, performance, position and impact of its activity […]’.

47 The 2019 Non-Binding Guidelines on non-financial reporting: Supplement on reporting climate-related information

highlight that, as indicated in the Commission’s 2017 Non-Binding Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting, the reference

to the ‘impact of [the company’s] activities’ introduced a new element to be taken into account when assessing the

materiality of non-financial information. In fact, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive has a ‘double materiality’

perspective:

a) The reference to the company’s ‘development, performance [and] position’ indicates financial materiality (inside-out),

in the broad sense of aecting the value of the company as it relates to ESG issues. This perspective is typically of

most interest to shareholder and other investors

29

.

b) the reference to ‘impact of [the company’s] activities’ indicates environmental and people materiality (outside-in, or

‘impact materiality’). This perspective is typically of most interest to those who are concerned with the impacts of

companies on environment, people and communities, including citizens, consumers, employees, business partners,

ethical investors, communities and civil society organisations

30

.

48 The materiality perspective of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive thus covers both ‘financial materiality’ and ‘impact

materiality’.

28 The Accounting Directive was amended by the NFRD, inserting article 19a).

29 Please note that there are many dierent categories of investors who have complex motivations (e.g. profitability, shareholders’ return, human rights and

environmental performance).

30 EC 2019 Non-Binding Guidelines on non-financial reporting: Supplement on reporting climate-related information, pages 4 and 5

1717

49 This double materiality perspective means that as it concerns the NFRD, stakeholders should be provided with

information on the outside-in and inside-out impacts.

50 The consultation on the NFRD revision shows that many respondents (e.g. preparers, financial authorities, national

standard setters) supported the concept of double materiality as introduced in the EC June 2019 non-binding guidelines

on climate-related non-financial information, however they considered that such a concept should be further clarified

and explicitly included in the revised NFRD.

51 A vast majority of respondents expect that any future standard should leads for report preparers to disclose more

information about the materiality assessment process and about the resulting material issues

31

.

52 Key question in the PTF’s analysis of the Materiality is: ‘How can the approach to materiality in the future European non-

financial reporting standard lead to reporting organisations disclosing more relevant non-financial information?’

Analysis

Concepts and definitions of materiality

53 Materiality is an important concept in most existing financial information and non-financial information reporting standards

and frameworks. However, definitions, perspectives and the level at which the materiality approach is applied dier

significantly.

54 The definition of materiality varies depending on the report users and objectives of the framework or standard. The

definitions for materiality or related concepts to include and/or prioritise report content are either based on:

a) the influence of the reported information on decision-making of the user (IFRS, SASB, GRI, Sustainable Development

Goals Disclosure (SDGD)), and/or

b) the organisation’s ability to create (or destroy) value (IIRC, WEF/IBC, SDGD); and/or

c) the relevance of impacts on people and environment (GRI, UNGP RF, EMAS).

55 Three dierent materiality perspectives are recognised amongst the existing frameworks and standards:

a) financial materiality;

b) environmental and people materiality or impact materiality; and

c) double materiality that covers both perspectives, recognising they in part overlap.

56 Materiality is often explicitly connected to risks and impacts (NFRD, IIRC, TCFD, UNGP RF). Depending on the

abovementioned perspectives, existing frameworks and standards either refer to risks and impacts of non-financial

issues on the organisation (outside-in) or the risks and impacts of the organisation on dierent non-financial issues

(inside-out). When a risk or actual impact surpasses a certain threshold, it may qualify to be relevant or important enough

to be included in the reported and hence classified as material information. For example, the NFRD explains that ‘a

number of factors may be taken into account when assessing the materiality of information.’ Among these ‘(...) principal

risks are relevant considerations’

32

. The IIRC Framework provides that ‘the process to determine materiality applies to

both positive and negative matters, including risks and opportunities and favourable and unfavourable performance or

prospects’

33

.

57 Determination of material topics and subtopics diers in existing frameworks and standards. Some leave it to the report

preparer to determine material topics and sub-topics (e.g. GRI); in other standards material topics are predefined (e.g.

SASB). The materiality assessment process (and its disclosure) has more importance in standards that leave more

31 Summary Report of the Public Consultation on the Review of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (2020)

32 European Commission Guidelines on non-financial reporting, 2017, p. 6

33 IIRC, The International <IR> Framework (2013), p. 18

1818

discretion to the report preparer because it will help the report user to comprehend the choices made by the preparer

(e.g. IIRC).

58 The definition of materiality included in the standards and frameworks (consisting of core frameworks and standards

analysed and additional sources), the objective, the user, the materiality approach and the level of prescription of

materiality information is reported in the following table:

34 Information provided by GRI in response to PTF questionnaire.

35 GRI 101 – Foundation (2016), p. 10

36 According to GRI, its standard, “focuses on environmental and social materiality, a sub-set of this information will also be financially material at any given

moment in time. GRI has always highlighted that all sustainability issues have the potential to become financially material – and the point in time when this

occurs for an individual entity depends on time horizon, business model, context. The GRI Standards center around the company’s conduct and activities,

and how these impact environment and society and eventually the company itself. The GRI Standards do not cover external risks to the company, which are

unrelated to the company’s conduct.” [Information provided by GRI in response to PTF questionnaire]

37 Information provided by IIRC in response to PTF questionnaire.

38 In the IIRC Framework, reference to the creation of value: a) includes instances when value is preserved and when it is diminished, and b) relates to value

creation over time (i.e., over the short, medium and long-term).

39 IIRC, The <IR> Framework (2013), p. 18

Core framework/

standard Mission/objective Audience Materiality definition

Materiality

perspective/

approach

Material topics

determined by

GRI “GRI envisions

a sustainable

future enabled by

transparency and open

dialogue about impacts.

This is a future in which

reporting on impacts is

common practice by all

organisations around

the world. As provider of

the world’s most widely

used sustainability

reporting standards,

we are a catalyst for

that change.”

34

All

stakeholders

“Relevant topics, which

potentially merit inclusion in

the report, are those that can

reasonably be considered

important for reflecting the

organisation’s economic,

environmental, and people

impacts, or influencing the

decisions of stakeholders”

35

People and

environmental/

Impact

materiality*

36

Reporting

Entity (based

on extensive

guidance)

IIRC “The IIRC’s purpose is

to promote prosperity

for all and to protect

our planet. The IIRC’s

mission is to establish

integrated reporting

and thinking within

mainstream business

practice as the norm

in the public and

private sectors.”

37

Financial

capital

providers

“An integrated report should

disclose information about

matters that substantively aect

the organisation’s ability to

create value

38

over the short,

medium and long-term.”

39

Financial

Materiality

Reporting

Entity (limited

guidance)

1919

40 Information provided by SASB in response to PTF questionnaire.

41 SASB Conceptual Framework, p. 9

42 SASB Exposure Draft on Conceptual Framework, p. 7

43 Information provided by Mazars Shift in response to PTF questionnaire

44 UN GP Reporting Framework, p. 22-24

45 EU Taxonomy Regulation 2020/852

46 Final Report – Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (2017)

Core framework/

standard Mission/objective Audience Materiality definition

Materiality

perspective/

approach

Material topics

determined by

SASB “The mission of the

SASB is to establish

and improve industry

specific disclosure

standards across

financially material

environmental, social

and governance

topics that facilitate

communication

between companies

and investors about

decision-useful

information.”

40

Financial

capital

providers

“Information is material if there is

a substantial likelihood that the

disclosure of the omitted fact

would have been viewed by the

reasonable investor as having

significantly altered the ‘total mix’

of information made available.”

41

“A topic is financially material

if omitting, misstating, or

obscuring it could reasonably

be expected to influence

investment or lending decisions

that users make on the basis

of their assessments of short-

, medium-, and long-term

financial performance and

enterprise value (new proposal

of definition included in the

SASB Exposure Draft on

Conceptual Framework)”

42

Financial

Materiality

Determined by

standard setter

on a sector

basis (based

on historical

evidence)

UN Guiding

Principles

Reporting

Framework

“Building a world

where business gets

done with respect for

people’s dignity”

43

All

stakeholders

Companies should report on

their salient human rights issues:

those human rights that stand

out because they are at risk of

the most severe negative impact

through the company’s activities

or business relationships.

44

People and

environmental/

Impact

materiality

Reporting

Entity (with

detailed

materiality

process

requirements)

Taxonomy

Regulation

Providing a classification

system to drive towards

environmental and

sustainability activities

45

Financial

capital

providers

People and

environmental/

Impact

materiality*

Level 2

legislation

TCFD Increase transparency

on material climate-

related business risks;

help organisations

assess whether climate-

risks are material for

their financial filings

46

Financial

capital

providers

Financial

Materiality

Standard setter

2020

47 EU Regulation No 1221/2009, Recital 17, p. 2

48 EU Regulation No 1221/2009, Art. 2 (Definitions), p. 4

49 https://futurefitbusiness.org/

50 https://www.nachhaltigkeitsrat.de/en/projects/the-sustainability-code

51 Information provided by German Council for Sustainable Development in response to PTF questionnaire.

52 Natural Capital Protocol, p. 2

53 Natural Capital Protocol, p. 43

Core framework/

standard Mission/objective Audience Materiality definition

Materiality

perspective/

approach

Material topics

determined by

Additional sources

EMAS Inform the “public”

and interested parties

of an organisation

of compliance with

environmental

legal requirements

and environmental

performance of an

organisation

47

All

stakeholders

environmental statement

shall include information

on an organisation’s

significant environmental

aspects and impacts

48

People and

environmental/

Impact

materiality*

Standard setter

Future Fit

Business

Benchmark

Strategic management

tool for companies

and investors to

assess, measure and

management the impact

of their activities

49

Financial

capital

providers

and other

stakeholders

Double

Materiality*

Standard setter

German

Sustainability

Code

Entry point to

sustainability

reporting, act as easy

implementable and

structured framework

for NFRD and UNGP

50

All

stakeholders

“Sustainability topics are

considered material if they

fall into one or more of the

following categories:

• Sustainability topics entailing

opportunities or risks for the

course of the business, the

annual financial statements

or the company’s situation

(outside-in perspective),

• Sustainability topics which

are either positively or

negatively aected by

the company’s business

activities, business relations

or products and services

(inside-out perspective);

• Sustainability topics which

are defined as material

by key stakeholders

(stakeholder perspective)”

51

Double

Materiality

Standard setter

Natural Capital

Protocol

Identify, measure, value

and disclose impact

and dependency

on natural capital to

include it in business

decision making

52

Undefined “An impact or dependency

on natural capital is material if

consideration of its value, as part

of the set of information used

for decision making, has the

potential to alter that decision”

53

Double

Materiality

Reporting

entity

2121

59 The table shows that there are dierent approaches to materiality in existing frameworks and standards. A considerable

number of standards prescribe material topics or specific metrics for reporting (e.g. SASB or German Sustainability

Code). For standards and frameworks that do not prescribe material topics, the materiality definition and guidance for its

application by reporting organisations has naturally more prominence and importance. The materiality perspectives and

determination applied or mandated by standards and frameworks are often closely connected to their target audience,

as well as their related missions and objectives.

Materiality assessment process

60 The materiality assessment process is most often presented as ‘guidance’ and involves the identification, evaluation and

prioritisation of topics and a decision on how and what to disclose for dierent sustainability topics or sub-topics.

61 In most cases, specific factors/criteria are provided (and usually not prescribed) that can be applied in the assessment

process. Inputs in assessing the factors and criteria can be quantitative (or even monetary) thresholds as well as

qualitative criteria (like stakeholder importance or severity of impact). Reporting standards/frameworks focused on a

single sustainability topic use comparable approaches to identify issues an organisation needs to act and report upon:

a) The UNGP Reporting Framework (UNGP RF) requires identification of ‘salient human rights issues,’ which reflect the

reporting entities’ connection to the most severe impacts on people’s human rights;

b) The EU Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS)

56

requires the identification of all direct and indirect environmental

aspects with a significant impact on the environment, assessing the potential to cause environmental harm, the fragility

of local/regional/global environment, the size, number, frequency and reversibility of the aspect/impact, the existence

and requirement of relevant environmental legislation and the importance to the stakeholders and employees of the

organisation.

62 Where material topics are prescribed, the materiality assessment processes are conducted by the standard setter

instead of the reporting entity. For example, SASB identifies sustainability issues that are likely to aect the financial

54 Sustainable Development Goals Disclosure Recommendations, p. 6

55 Sustainable Development Goals Disclosure Recommendations, p. 9

56 EMAS does not use the “materiality” but a comparable concept of “significance”. The environmental statement includes information on an organisation’s

significant environmental aspects and impacts. The environmental aspects are element of an organisation’s activities, products or services that has or can

have an impact on the environment” (inside-out perspective). The environmental impacts are changes to the environment, whether adverse or beneficial,

wholly or partially resulting from an organisation’s activities, products or services.

Core framework/

standard Mission/objective Audience Materiality definition

Materiality

perspective/

approach

Material topics

determined by

SDGD

Recommendations

“Identification of

material sustainable

development risks and

opportunities relevant to

long-term value creation

for organisations

and society”

54

Financial

capital

providers

and other

stakeholders

“Material sustainable

development information is any

information that is reasonably

capable of mak-ing a dierence

to the conclusions drawn by:

(a) stakeholders concerning

the positive and negative

impacts of the organisation

on global achievement

of the SDGs, and;

(b) providers of finance

concerning the ability of

the organisation to create

long-term value for the

organisation and society”.

55

Double

Materiality

Reporting

entity

* Materiality is not an explicit concept

2222

condition or operating performance of companies within an industry, and therefore are most important to investors.

Instead, GRI or IIRC do not prescribe material topics to disclose, leaving the reporting entity to conduct that process.

63 Some standards require reporting on the materiality assessment process for defining report content, notably GRI, UNGP

RF and EMAS and explicit stakeholder inclusion in the materiality assessment is common practice in sustainability

reporting (GRI, IIRC, UNGP RF, EMAS, German Sustainability Code, NFRD guidance).

64 GRI explains that a process of stakeholder engagement can serve as a tool for understanding the reasonable

expectations and interests of stakeholders, as well as their information needs. It is important for the organisation to

document its approach to identifying stakeholders; deciding which stakeholders to engage with, and how and when to

engage with them; and how engagement has influenced the report content.

65 According to IIRC, stakeholder engagement is needed to identify relevant matters, consider topics or issues that are

important to key stakeholders. IIRC explains also that an understanding of the perspectives of key stakeholders is critical

to identifying relevant matters.

66 The UN GP Reporting Framework explains that companies may use a “traditional” materiality process for their broader

annual, sustainability or integrated report that involves feedback from external stakeholders. If so, they can benefit

from that process to explain to stakeholders how they identified their salient human rights issues, including any inputs

from those who may be directly aected, and the conclusions they reached. They can then seek these stakeholders’

feedback on their conclusions and whether any key considerations have been overlooked. In the event that a company

applies a definition of materiality to its broader annual, sustainability or integrated report that sets narrower criteria for

the inclusion of issues, this may exclude certain salient human rights issues or certain information about how such issues

are managed. If so, the reporting company should provide a clear reference to where that additional information can be

found, for example, in a separate report or a specific location on its website.

Key considerations for a potential EU Sustainable Standard

67 Most non-financial reporting standards and frameworks oer definitions and concepts for materiality supported by

operational guidance. However, taken all together this has not led to suciently relevant information being disclosed

from a double materiality perspective. This is due in part to a number of challenges in the operational implementation of

double materiality, including:

a) that in practice the materiality assessment related to people and the environment is often carried out with an implicit

financial materiality lens, i.e. a focus on the risks to the company. In such cases, the applied methods do not accurately

ascertain the needs, expectations and priorities of key stakeholder groups, and limit an assessment related to the

(actual or potential) impacts that the reporting entity can have on people, communities and the environment;

b) there is a lack of clarity on how reporting entities should include perspectives of aected and other relevant

stakeholders in their assessment of impacts and prioritisation (for action and reporting);

c) the insucient alignment between what companies are expected to prioritise for reporting and what they are

expected to prioritise for action (this will become especially relevant in the context of new legislation on mandatory

human rights and environmental due diligence, at national and EU level).

68 Existing non-financial standards and frameworks (researched in this report) apply dierent approaches for identifying

material topics and information. What is material is in some cases defined by the standard setter, in others by the

reporting entity or in a third variant by a mix of both. While higher levels of prescription may help in some cases to the

comparability and reliability/assurability of information, it may come at the cost of becoming a tick-the-box exercise by

report preparers and failing to provide a comprehensive picture of a company’s development, performance and impact.

The NFRD revision and a future European reporting standard will need to find a smart mix of prescription and flexibility

for determining report content.

69 Where a NFRD revision would suggest any change in current established approaches, the above analysis suggests

that it will be critical for the ESS to consider why current guidance and approaches have not led to suciently relevant

2323

information being disclosed from a double materiality perspective and to consider what it would need to highlight

through the standards it sets and communicates to support and enable the necessary changes to happen..

SCOPE OF REPORTING

Definition and relevance

70 The ‘scope of reporting’ refers to the scope of what a company should report on regarding its activities, products and

services and associated risks and impacts (positive and negative). The scope of reporting is closely related to the topic

of materiality, as well as strategy and governance.

71 In financial reporting frameworks, the scope of the entity is defined based on the concept of control and dominant

influence (scope of consolidation). In non-financial reporting (NFR), however, the sustainability impacts, risks and

opportunities of the reporting entity typically extend beyond the legal scope of the reporting entity and may include:

a) suppliers and the supply chain (upstream);

b) customers, end users (downstream);

c) subsidiaries that are outside the scope of consolidation and/or group companies over which the reporting entity does

not have legal control (midstream).

72 In order to understand the impacts and risks, threats and opportunities of the reporting entity from a double materiality

perspective, it is necessary for NFR to extend beyond the entity’s ‘scope of control’

57

. Specifically, there is a need to

go beyond ‘company, group or control’ and extend non-financial information on topics considered material to impacts

concerning, for example, ‘business relationships’ (in this context, companies not fully consolidated) and the ‘value chain’,

where relevant. In any case, it is necessary to consult stakeholders about the impact of the ‘organisation’ in the relevant

areas.

73 The consultation on the NFRD revision shows that the supply chain is one of the most frequently mentioned non-

financial matters respondents would like companies to be required to report on, in addition to the non-financial matters

already specified in the NFRD.

58

74 The current NFRD does not include clear requirements about this topic. For example, the supply chain and the value

chain are only included insofar as it is deemed relevant and proportionate by the company when reporting on due

diligence processes and principal risks:

a) Recital 6 of the NFRD states that ‘The non-financial statement should also include information on the due diligence

processes implemented by the undertaking, also regarding, where relevant and proportionate, its supply and

subcontracting chains, in order to identify, prevent and mitigate existing and potential adverse impacts.’

b) Recital 8 of the NFRD indicates that The undertakings which are subject to this Directive should provide adequate

information in relation to matters that stand out as being most likely to bring about the dematerialisation of principal

risks of severe impacts, along with those that have already dematerialised. (…) The risks of adverse impact may stem

57 Article 2 of the Accounting Directive defines the following concepts:

• ‘parent undertaking’ means an undertaking which controls one or more subsidiary undertakings;

• ‘subsidiary undertaking’ means an undertaking controlled by a parent undertaking, including any subsidiary undertaking of an ultimate parent undertaking;

• ‘group’ means a parent undertaking and all its subsidiary undertakings;

• ‘aliated undertakings’ means any two or more undertakings within a group;

• ‘associated undertaking’ means an undertaking in which another undertaking has a participating interest, and over whose operating and financial policies

that other undertaking exercises significant influence. An undertaking is presumed to exercise a significant influence over another undertaking where it

has 20% or more of the shareholders’ or members’ voting rights in that other undertaking.

• Article 21 of the Accounting Directive explains the scope of consolidated financial statements and reports and article 22 provides the requirement to

prepare consolidated financial statements.

58 Summary Report of the Public Consultation on the Review of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (2020), p.9.

2424

from the undertaking’s own activities or may be linked to its operations, and, where relevant and proportionate, its

products, services and business relationships, including its supply and subcontracting chains.

c) Article 19a) of the NFRD provides that non-financial statement contains information including the principal risks related

to those matters linked to the undertaking’s operations including, where relevant and proportionate, its business

relationships, products or services which are likely to cause adverse impacts in those areas, and how the undertaking

manages those risks.

59

75 An expanded ‘scope of reporting’ beyond the scope of control of the reporting entity is referenced in the EC’s 2017 Non-

Binding Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting, specifically regarding materiality and the business model:

a) ‘Materiality is a concept already commonly used by preparers, auditors and users of financial information. A company’s

thorough understanding of the key components of its value chain helps identify key issues and assess what makes

information material.’

b) ‘A number of factors may be taken into account when assessing the materiality of information. These include:

(i) Business model, strategy and principal risks: a company’s goals, strategies, management approach and systems,

values, tangible and intangible assets, value chain and principal risks are relevant considerations.

(…)

(ii) Impact of the activities: companies are expected to consider the actual and potential severity and frequency

of impacts. This includes impacts of their products, services, and their business relationships (including supply

chain aspects).’

c) ‘The following items constitute a non-exhaustive list of thematic aspects that companies are expected to consider

when disclosing non-financial information:

(…)

(iii) Respect for human rights – Companies are expected to disclose material information on potential and actual

impacts of their operations on right-holders. … The information may explain whose rights the commitment

addresses, for instance … the rights of workers, including those working under temporary contracts, workers in

the supply chains or sub-contractors, migrant workers, and their families. Companies should consider making

material disclosures on human rights due diligence, and on processes and arrangements implemented to

prevent human rights abuses. This may include, for instance, how a company’s contracts with businesses in its

supply chain deal with human rights issues, and how a company mitigates potential negative impacts on human

rights and provides adequate remedy if human rights have been violated.

(…)

(iv) Others – Supply chains – Companies, where relevant and proportionate, are expected to disclose material

information on supply chain matters that have significant implications for their development, performance,

position or impact. This would include information needed for a general understanding of a company’s supply

chain and of how relevant non-financial matters are considered in managing the supply chain.’

d) ‘Key performance indicators – … Disclosing high quality, broadly recognised KPIs (for instance, metrics widely used in

a sector or for specific thematic issues) could also improve comparability, in particular for companies within the same

sector or value chain.’

60

59 Article 19a) (1)(d) of the Non-financial Reporting Directive.

60 EC 2017 Non-Binding Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting, p. 5, 6, 13, 16, 17.

2525

76 Furthermore, the value/supply chain and the life-cycle concept are referenced in the EC’s 2019 Non-Binding Guidelines

on Non-Financial Reporting: Supplement on reporting climate-related information:

a) ‘When assessing the materiality of climate-related information, companies should consider their whole value chain,

both upstream in the supply-chain and downstream.’

b) ‘Both of these kinds of risk – risks of negative impacts on the company and risks of negative impacts on the climate

– may arise from the companies own operations and may occur throughout the value chain, both upstream in the

supply-chain and downstream.’

c) ‘When reporting on their climate-related risks, dependencies and opportunities, companies should, where relevant

and proportionate, consider their whole value chain, both upstream and downstream. For companies involved in

manufacturing activities this means following a product life cycle approach that takes account of climate issues in the

supply chain and the sourcing of raw material, as well as during the use of the product and when the product reaches

end-of-life. Companies providing services, including financial services, will also need to consider the climate impacts

of the activities that they support or facilitate. When SMEs are part of the value chain, companies are encouraged to

support them in providing the required information.’

61

77 However, relatively few reporting entities report that they apply the NFRD reporting guidelines; the Alliance for Corporate

Transparency 2020 report indicates that only 5% of the top 1000 listed companies in the EU reference these guidelines

62

.

78 There is the concern among some that expanding the scope could lead to greater costs and administrative burdens,

including from preparers responding to the Commission’s 2020 consultation on the revision of the NFRD. They stressed

the need to ensure sucient time for collection and analyses of data from the supply chain companies as well as

subsidiaries and argued for a dierence between the deadline for financial and non-financial reports. Regarding the

expansion of the scope, it is necessary to focus on prioritisation in terms of impacts and risks.

63