THE CLEARWATER STORY

A History of the Clearwater National Forest

By

Ralph S. Space

Clearwater National Forest Supervisor, 1954-1963

1981

Forest Service

U.S. Department of Agriculture

The Clearwater Historical Society, Orofino, Idaho

Northern Region-79-03

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Chapters

1. Lewis and Clark West

2. Lewis and Clark East

3. The Lewis and Clark Grove

4. John Work

5. Captain John Mullan, U.S. Army

6. Wellington Bird and Major Truax

7. The Carlin Party

8. Maps

9. Boundaries

10. Railroad Surveys

11. June 11 Claims

12. Working and Living Conditions

13. Roads and Trails

14. Timber Management

15. Grazing

16. Fire Control

17. Wildlife

18. Mining

19. Trapping

20. Mountain Tragedies

21. Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness

22. Wilderness Gateway or Boulder Flat

23. Emergency Work Programs

24. The Ridgerunner

25. Bernard DeVoto

26. Some Long Hikes

27. Packing

28. Miscellaneous Events

Appendix A - Forest Personnel

Appendix B - Geographic Names

FOREWORD

Most Forest Service employees become very familiar with the various areas where they are

stationed. Ralph Space had the fortunate experience of finishing out his career in the area where

he was reared. So in addition to the usual interest any new employee would bring to the

Clearwater, Ralph brought a keen interest in its people and history which he had developed as a

youth and nurtured as he pursued his Forest Service career.

The story of the Clearwater country is written in the lives of individual people. Ralph gives us a

glimpse into some of these lives. He has preserved a look at life as it was in the early-day Forest

Service and reminds us of some of the triumphs and tribulations of Indians, explorers, miners,

homesteaders and others who preceded the Forest Service by many years.

This work will be a great help to the student of local history and will be a good historical

reference for Forest Service land managers. It will also help give new forest employees an

understanding of the forest's heritage and will bring back many good memories for retired

personnel.

We in the Northern Region praise Ralph for his fine work and thank him for preserving this

collection of Clearwater "color."

Regional Forester

Northern Region

Clearwater National Forest

Location Map

The Lolo Trail

PREFACE

In 1959 Regional Forester Charlie Tebbe and I were discussing some of the events that had taken

place on the Clearwater National Forest. It was during this discussion that we agreed it was

unfortunate that the Forest did not have a written history. Charlie then suggested that I write it.

He further remarked that if I didn't do it, he doubted anyone else would.

I was a busy man, but worked on the history at odd times over the next three years. Most of it I

dictated. Much of my dictation was not transcribed until after I retired in 1963. "The Clearwater

Story" was printed in 1964, but the history of the Forest concluded as of 1960.

It was well received by the Forest Service and the general public. There have been several

thousand copies given to interested persons by the Forest Service. However, I was not satisfied

with it. It was not a complete history and it contained a number of errors. Some of the errors

were factual, but most of them were in the spelling of names. Some dates were wrong.

Several people have urged me to rewrite the "Clearwater Story." This second book is an effort to

present a more complete, accurate, and up-to-date history of the Clearwater National Forest as of

the late 1970's.

Ralph S. Space

Ralph S. Space

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I was raised in the Clearwater country near Weippe, so I have heard tales of the Clearwater since

I was a small boy. I worked on the Clearwater while going to college and I was Forest

Supervisor for nine years. I have known every Supervisor of the Clearwater back to and

including Major Fenn. I have always been interested in history so I collected historical facts as I

went along. This book is a product of what history I have been able to learn by a lot of digging in

records and talking to people during a life of nearly 80 years.

Many people have furnished information for this book. Those outside of the Forest Service who

have passed away include my father, C.W. Space, my brothers, Allen and Roy, Ernest Hansen,

Cully Mooers, Harry Wheeler, Henry Holleman, William and Jimmy Parsons, Ed Gaffney,

Walter Sewell, and others.

Those outside the Forest Service and still living include Mr. and Mrs. Bill Harris, Frank

Altmiller, Angus Wilson, Warren Bohn, and others.

Forest Service retirees still living are Louis Hartig, LaVaughn Beeman, Bud Moore, Rollo

Perkins, Del Cox, Marvin Riley, Ralph Hand, and Morton Roark.

Retirees that have passed away include Albert Cochrell, Clayton Crocker, James Urquhart, Paul

Wohlen, James Girard, Adolph Weholt, Jack Godwin, and W.W. White.

I had wonderful help and cooperation from the Forest Service. On the Clearwater Forest I was

helped by Art Johnson (now retired), Robert Spencer (retired), Robert Adams, Ed Russell, Don

Jenni, and especially Andy Arvish (also retired). The graphics were prepared by Cheri Ziebart.

In the Regional Office Judd Moore, Peyton Moncure and Beverly Ayers were very helpful.

As might be supposed, most of my information came from the files of the Forest Service. I have

also taken information from the following: Journals of Lewis and Clark; General Howard's

Report on the Nez Perce War; McWhorter's book, Yellow Wolf; articles by Elers Koch; John B.

Leiberg's report on the Bitter Root Forest Reserve; Dean Shattuck's report of 1910; the story of

the Carlin Party as told in their book, In the Heart of the Bitterroot; Sister Alfreda's, History of

Idaho County; Albert Cochrell's, Nezperce Story: Early Days of the Forest Service; information

to be included in Hartig's history of the Lochsa District; articles from The Lewiston Morning

Tribune; and a number of old maps and letters.

To all this I have added by intimate knowledge of the Clearwater country and its people. I thank

everyone for their assistance.

Chapter 1

Lewis & Clark West

In this chapter and the one that follows I will trace the westward and

eastward journeys of Lewis and Clark across the Clearwater National

Forest. In doing so, I will quote Thwaite's journal. I will add my

comments either in parenthesis or after each day's journey. Dotted lines will designate omissions

from the journal, and to make easier reading I will use modern spelling.

Starting at Lolo Hot Springs on Highway 12 in Montana.

Sept. 13 (1805 Clark) ".....We proceeded over a mountain and at a place 6 miles from where I

nooned it, (on Lolo Creek) we fell on a small creek (Pack) from the left, which passed through

open glades, (Packer Meadows) some of which were one half mile wide.

"We proceeded down this creek about two miles to where the mountains close on either side and

encamped. I shot four pheasants of the common kind except the tail was black. Shields killed a

blacktail deer."

Comment: The party is now in Idaho and camped at the lower end of Packer Meadows. The

pheasants were Franklin Grouse or foolhens. The deer was a mule deer.

Sept. 14 (1805 Whitehouse).

"A cloudy morning. We eat the last of our meat." (Clark) "We crossed a high mountain on the

right of the creek for six miles to the forks of the Glade Creek, the right hand fork which falls in

is about the size of the other. We crossed to the left side of the forks and cross a very high

mountain for nine miles to a large fork from the left which appears to head in the snow topped

mountains south and S.E."

"We cross Glade Creek above the mouth at a place where the Flathead Indians have made a weir

to catch salmon and have but lately left the place. I could see no fish and the grass entirely eaten

out by the horses, we proceed on two miles and encamped opposite a small island at the mouth

of a small branch on the right side of the river, which is at this place 80 yards wide, swift and

stoney."

"Here we were compelled to kill a colt for our men and selves to eat for want of meat, and we

named the south fork Colt Killed Creek (White Sand) and this we call the Koos Koos Ke. Turned

our horses on the island."

"Rained, snowed, and hailed the greater part of the day. All wet and cold."

Comment: The party left Packer Meadows and went over the ridge between Crooked Fork and

Pack Creek to where Brushy Creek joins Crooked Fork Creek. They then crossed Brushy Creek

and went over the ridge between Crooked Creek and Cabin Creek to where White Sand and

Crooked Fork Creek join to make the Lochsa River, they crossed to the north bank of the Lochsa

and after traveling two miles camped at the present site of the Powell Ranger Station.

The island is now so heavily timbered that it would not furnish grass enough for one horse. The

Powell camp is well marked.

Northern Pacific survey pack train crossing Packer Meadows in 1909. Lewis and Clark

arrived here Sept. 13, 1805. They camped at the lower end of the meadows.

1938 photo at Powell Ranger Station, sites of the

Lewis and Clark Expedition's Sept. 14, 1805 camp.

Sept. 15 (1805 Clark) "We set out early, the morning cloudy, and proceeded on down the right

side of the river, over steep points, rocky and brushy as usual, for four miles to an old Indian

fishing place. Here the road leaves the river to the left and ascends a mountain, winding in every

direction to get up the steep ascents and to pass the immense quantity of fallen timber which has

fallen from different causes, i.e. fire and wind, and has deprived the greater part of the south

sides of this mountain of its timber. Four miles up the mountain I found a spring and halted for

the rear to come up and let our horses rest and feed. In about two hours the rear of the party came

up, much fatigued, and horses more so. Several horses slipped and rolled down the steep hills,

which hurt them very much. The one which carried my desk and small trunk turned over and

rolled down a mountain for 40 yards and lodged against a tree, broke the desk. The horse

escaped and appeared but little hurt. From this point I observed a range of mountains covered

with snow from S.E. to S.W., with their tops bald or devoid of timber. After two hours of delay,

we proceeded on up the mountain. When we arrived at the top, we conceived we would find no

water and concluded to camp and make use of snow we found on top to cook the remains of our

colt and make soup. Two of our horses gave out, poor and too much hurt to proceed, and left in

the rear. Nothing killed today except two pheasants" (ruffed grouse).

Comment: The party went down the north bank of the Lochsa to the ridge between Wendover

and Cold Storage Creeks. The fishing place was just above the mouth of Wendover Creek. I

found Indian artifacts there, proving that this was an old Indian campground.

Whitehouse mentions passing a pond. This pond is now called Whitehouse pond, as is the

campground across Highway 12. (The author suggested this name for the pond.)

The party went up Wendover Ridge, which was burned at that time but now has a beautiful stand

of mature timber, and camped on top of an unnamed mountain. The Forest Service has a sign

marking the place the old trail crosses the present Lolo Motorway.

The high snowy mountains were the Bitterroot Mountains south of Lolo pass.

Sept. 16 (1805 Clark)

"Began to snow about three hours before day and continued all day. The snow in the morning

four inches deep on the old snow, and by night we find it six to eight inches deep. I walked in

front to keep the road and found great difficulty in keeping it, as in many places the snow had

entirely filled the track and obliged me to hunt several minutes for it. At 12 o'clock we halted on

top of the mountain to warm and dry ourselves a little, as well as to let our horses rest and graze

a little on some grass which I observed. The knobs, steep hillsides, and fallen timber continue

today, and a thick, timbered country of eight different kinds of pine, which are so covered with

snow that in passing through them we are continually covered with snow. I have never been wet

and as cold in every part as I ever was in my life; indeed, I was at one time fearful my feet would

freeze in the thin moccasins I wore. After a short delay in the middle of the day, I took one man

and proceeded as fast as I could about six miles to a small branch crossing to the right, halted and

built fires for the party that arrived at dusk, very cold and much fatigued. We camped on this

branch in a small timbered bottom, which was scarcely large enough for us to lie level. Men all

cold and hungry. Killed a second colt, which we all supped heartily on and thought it fine meat.

"I saw four deer today before we set out, which came up the mountain, and what is singular,

snapped seven times at a large buck. My gun has a steel fuzee and never snapped seven times

before. In examining it, found the flint loose."

Whitehouse says ".....We descended the mountain down to a lonesome cove on a creek, where

we camped in a thicket of spruce, pine, and balsam fir timber." Whitehouse also says "Cap. Clark

shot at a deer but missed it."

Comment: Hunting stories are often known to disagree but in either case it was a keen

disappointment to the hungry party.

The place Lewis and Clark camped on Sept. 16 has been much disputed. It is my belief that they

ate lunch at Spring Hill. The distance checks and there is an abundance of grass there.

The Lonesome Cove Camp is almost due north of the Indian Post Office rock cairns. The old

trail, parts of which can be still found by careful searching, turned back or switch backed at the

rock cairns and dropped off on the north side and came close to a small timbered flat with a

small creek. This is where I believe they camped.

The eight species of the pine family Clark observed were likely alpine fir, grand fir, Englemen

spruce, mountain hemlock, Douglas fir, western white pine and white barked pine.

View to the north from the divide which separates the Lochsa and North Fork of the

Clearwater River drainages. The party travelled along this ridge Sept. 16 after having

climbed out of the Lochsa River canyon the previous day.

The author standing by rock cairns at Indian Post Office. The Expedition camped

near there the night of Sept. 16.

Indian Post Office Lake, immediately south of the rock cairns.

Sept. 17. 1805. Whitehouse: "Cold and cloudy. We went out to hunt our horses, but found them

much scattered. The mare which owned the colt which we killed went back and led four more

horses back to where we took dinner yesterday. The most of the other horses found scattered on

the mountain, but we did not find all until noon, at which time we set out and proceeded on. The

snow lay heavy on the timber. Passed along a rough road up and down the mountains. Descended

down a steep part of the mountain. The afternoon clear and warm. The snow melted so that the

water stood in the trail over our moccasins in some places. Very slippery, and bad traveling for

our horses. We ascend very high and rocky mountains; some bald places on the top of the

mountains, high rocks standing up and high precipices. Crossed several creeks or spring runs in

the course of the day. Camped at a small branch on the mountain near a round sink hole full of

water. We, being hungry, obliged us to kill the other sucking colt to eat. One of the hunters

chased a bear, but killed nothing. We expect that there is game near; we hear wolves howl and

saw some deer sign."

Clark states, "We camped at a run passing to the left."

Comment: The trail that Lewis and Clark followed did not stay on the main divide but dropped

down into Moon Creek, crossed Howard Creek, and down to the forks of Gravey and Serpent

Creeks, thence up the ridge between these creeks to the main divide. The eastern trip diaries are

more descriptive of this route.

The party killed the last of their colts at this camp, and apparently Lewis and Clark got together

on a plan of action that night, to decide what should be done about the emergency situation.

Sept. 18, 1805. Clark: "A fair cold morning. I proceeded on in advance with six hunters to try

and find deer or something to kill and send back to the party. The want of provisions, together

with the difficulty of passing the mountains, dampened the spirits of the party, which induced us

to resort to some plan of reviving their spirits. I determined to take a party of the hunters and

proceed on in advance to some level country where there was some game, kill some meat, and

send it back."

"We passed over a country similar to the one of yesterday. More fallen timber. Passed several

runs and springs passing to the right. From the top of a high mountain (Sherman Peak) at twenty

miles, I had a view of an immense plain and level country to the S.W. and W. At a great distance

a high mountain beyond the plain. Saw but little sign of deer and nothing else. Made 32 miles

and encamped on a bold running creek passing to the left, which I call Hungery (sic) Creek, as at

that place we had nothing to eat. I halted only one hour to let our horses feed on a grassy hillside

and rest. Drewyer shot at a deer but didn't get it."

Comment: Clark is now in the lead with six men.

The high mountain from which Clark saw the extensive plain is Sherman Peak. The plain they

saw was the open grass country extending northwest from Grangeville and is today called the

Camas and Nez Perce prairies. The high mountain beyond was likely Cottonwood Butte.

Hungery Creek became Obia Creek, and so it appears on old maps. At my suggestion, its name

has been changed back to Hungery Creek. Obia Creek is now a branch of Hungery Creek.

Sept. 18, 1805. Lewis: (Whitehouse and Gass were with Lewis.) "Clark set out this morning to

go ahead with six hunters. There being no game in these mountains we concluded it would be

better for one of us to take the hunters and provide some provisions, while the others remained

with and brought up the party. The latter was my part."

"Accordingly, I directed the horses be gotten up early, being determined to force my march as

much as the abilities of the horses would permit. The negligence of one of the party (Willard),

who had a spare horse, in not attending to him and bringing him up last evening, was the cause

of our detention this morning until 8:30 A.M., when we set out. I sent Willard back to search for

his horse and proceeded on with the party. At 4 P.M. he overtook us without the horse."

"We marched 18 miles this day and camped on the side of a steep mountain. We suffered for

water today, passing one rivulet only. We were fortunate in finding water in a deep ravine about

one-half mile from camp."

"This morning we finished the last of our colt. We supped on a scant portion of portable soup, a

few containers of which, a little bears oil, and about 20 pounds of candles, form our stock of

provisions, our only resources being our guns and horses. This is but a poor dependence where

there is nothing upon earth but ourselves, a few pheasants, small grey squirrels, and a blue bird

of the vulture kind about the size of a turtle dove or jay bird. Used snow for cooking."

Comment: The water the party crossed was at Indian Grave. The old trail went above the water at

Bald Mountain. The blue bird was a Steller's jay. Lewis' camp of Sept. 18 is about three miles

west of Bald Mountain and is marked with a Forest Service sign.

Sept. 19, 1805. Clark: "Set out early. Proceeded up Hungery Creek, passing through a small

glade at 6 miles, at which place we found a horse. I directed him killed and hung up for the party

after taking breakfast off for ourselves, which we thought fine."

"After breakfast proceeded on up the creek two miles and left it to our right. Passed over a

mountain and the head of a branch of Hungery Creek (Fish Creek), two high mountains, ridges

and through much fallen timber (which caused our road of today to be double the direct distance

of our course). Struck a large creek passing to our left which I kept down for four miles and left

to our left and passed over a mountain, bad fallen timber, to a small creek passing to our left and

encamped. I killed two pheasants (ruffed grouse) but few birds to be seen. As we descended the

mountain the heat becomes more perceptible every mile."

Comment: The glade where the horse was killed is on Hungery Creek about one quarter of a mile

from Windy Saddle. The party crossed to the head of Fish Creek then over the divide and down a

ridge to Eldorado Creek, down Eldorado Creek two miles, over a ridge to Cedar Creek and

camped.

The campground on Cedar Creek is marked by a Forest Service sign. There is also a splendid

grove of large western red cedar there called the "Lewis and Clark Grove." (See Chapter 3)

The author stands at the site of the Expedition's Sept. 17 campsite "near a

round sink hole full of water".

Interpretive sign at Lewis and Clark Grove, site of the Sept. 19 camp for

Clark's advance party.

The Lolo Motorway near Saddle Camp. Person in photo is standing on the location of the

Lolo Trail.

Sept. 19, 1805. Lewis: "Set out this morning a little after sunrise and continued our route about

the same course as yesterday for six miles, when the ridge terminated and we, to our

inexpressible joy, discovered a large tract of prairie country lying to the S.W. and widening as it

appeared to extend to the west. Through that plain, the Indian (Toby, their Shoshone guide)

informed us, the Columbia River of which we are in search runs. This plain appears to be about

60 miles distant (actually about 40), but our guide assured us we should reach its border by

tomorrow. The appearance of this country, our only hope of subsistence, greatly revived the

spirits of the party, already reduced and much weakened for want of food."

"After leaving the ridge, we ascended and descended several steep mountains, in the distance of

six miles further struck a creek (Hungery) about 15 yards wide, our course along this creek

upwards, passing two of its branches which flowed in from the north. First at the place we struck

the creek (Doubt Creek) and the other three miles further. (Bowl Creek)

"The road excessively dangerous along this creek, being a narrow, rocky path generally on the

side of a precipice. The course upward due west. We camped on the star side in a little ravine

having traveled 18 miles. We took a small amount of portable soup and retired much fatigued.

Several men are unwell of dysentary, breaking out or eruptions of the skin."

Comment: The mountain from which Lewis saw the plain was Sherman Peak. The joy of seeing

the open country to the S.W. is best expressed by Gass who wrote, "When this discovery was

made there was as much joy and rejoicing among the corps, as happens among passengers at sea,

who have experienced a dangerous protracted voyage, when they first discover land on the long

looked for coast."

Whitehouse states that after seeing the plains they "descended three miles, then ascended another

mountain as bad as any we have been up before. It made the sweat run off our horses and

ourselves." This is a vivid description of the trip from Sherman Peak into Sherman Saddle and to

the top of the mountain to the west.

The party reached Hungery Creek at the mouth of Doubt Creek; the second is Bowl Creek. The

little creek on which they camped is unnamed and unmarked except for a metal stake. It rises

near Green Saddle. I have suggested that it be named Soup Creek.

Sept. 20, 1805. Clark: "I set our early and proceeded on through a country as rugged as usual.

Passed over a low mountain into the forks of a large creek (Lolo and Eldorado), which I kept

down two miles, and ascended a high, steep mountain, leaving the creek to our left hand. Passed

the head of several drains on a dividing ridge and at 12 miles descended the mountain to a level

pine country. Proceeded on through a beautiful country for three miles to a small plain in which I

found many Indian lodges. At a distance of one mile from the lodges I met three Indian boys.

When they saw me, they ran and hid themselves in the grass. I dismounted, gave my gun and

horse to one of the men, searched and found two of the boys, gave them small pieces of ribbon

and sent them forward to the village. Soon after a man came out to meet me, with great caution,

and conducted me to a large spacious lodge, which he told me by signs was the lodge of his great

chief, who had set out three days previous with all the warriors of the nation to war on a

southwest direction, and would return in 15 to 18 days. The few men who were left in the

village, and great numbers of women, gathered around me with much apparent signs of fear, and

appeared pleased. They gave us a small piece of buffalo meat, and dried salmon, berries and

roots in different states, some round and some like an onion, which they call pash-she-co. Of this

they make bread and soup. They also gave us the bread made of this root, all of which we ate

heartily. I gave them a few small articles as presents, and proceeded on with a chief to his village

2 miles in the same plain, where we were treated kindly in their way, and continued with them all

night."

"These two villages consist of about 30 double lodges, but few men, a number of women and

children. They call themselves Chopunnish or pierced noses. Their dialect appears to be very

different from the Flatheads I have seen, dress similar, with more white and blue beads, brass

and copper in different forms, shells, and wear their hair in the same way. They are large portly

men, small women, and handsome featured."

"Immense quantity of the Quamash (camas) or passheco root gathered in piles about the plain.

The roots much like an onion in marshy places. The seeds are in triangular shells on the stalk.

They sweat them in the following manner, i.e., dig a hole three feet deep, cover the bottom with

split wood, on top of which they lay small stones about three or four inches thick, a second layer

of split wood, and set the whole on fire, which heats the stones. After the fire is extinguished,

they lay grass and mud mixed on the stones, on that dry grass which supports and passheco root

a thin coat of grass is laid on top. A small fire is kept, when necessary, in the center of the kiln."

"I find myself very unwell all of the evening from eating the fish and roots. Sent out hunters.

They kill nothing, but saw some signs of deer."

Comment: Clark left Cedar Creek, at Lewis and Clark Grove, and climbed the low ridge between

Cedar and Lolo Creeks. He then went down this ridge to the forks of Lolo and Eldorado Creeks;

crossed Lolo Creek and down it about one mile. From this point he climbed to Crane Meadows.

From there he went over the shoulder of Brown Ridge and down Miles Creek to Weippe Prairie.

He came upon three boys near Eric Larson's ranch. The first village was near Opresik's buildings.

The second camp was on the arm of the meadow southwest of Weippe. The first road to Weippe

came to this arm of the meadow, as did the trail from Weippe to Orofino. There are no markers

at either of these camp sites.

The name Weippe is of Nez Perce origin and is so old it has lost its meaning. Even in 1891 when

my father asked some of the old Indians what it meant, they had no answer except that it was the

name of a place. The English pronunciation is We-ipe (long i) but the Nez Perce pronounced it

Oy-yipe. It is a meadow where the Indians gathered camas, raced horses and played games.

Lewis and Clark called the Nez Perce, "Cho-pun-nish," which they said meant pierced noses.

Kate McBeth in her book The Nez Perces Since Lewis and Clark says, "Lewis and Clark called

these Indians the "Cho-po-nish." This was not correct, the word being Chup-nit-pa-lu, or people

of the pierced noses. William Parsons says the correct spelling is Chop-nit-pa-lu, the o is long.

The Nez Perces actually called themselves Ne-me-Poo or a slight variation of this word. Alice

Fletcher, who spent four years with the Nez Perces says: "Their native name 'Nim-e-poo'

signified 'the men or the real people', an appellation commonly used by tribes to distinguish

themselves from other peoples." The French called them the Nez Perce (Ney-per-say) but this

name has been anglicized to Nez Perce or Nezperce. It means pierced noses.

Passheco is a Shoshone word for camas. Later Lewis and Clark called it quamash. The Nez Perce

word is close to khamas from which comes the English word camas.

According to Nez Perce legend the Nez Perce considered massacring the party of Clark at

Weippe but were persuaded by one of their women named Wat-ku-ese, who had been befriended

by white people when a captive among Indians to the east, to treat them kindly. Captain Clark

knew of no such incident, but he did say that he met an Indian woman who had been as far east

as the Mandan Village. This statement strongly supports the Indian story.

Sept. 20, 1805, Lewis: Lewis first describes some birds which I take to be the flicker, Steller's

jay, camp robber or Canadian jay and three species of grouse common in the Bitterroot

Mountains. Then he states "We were detained until 10 A.M. in consequence of not being able to

collect our horses. We proceeded about two miles when we found the greater part of a horse,

which Captain Clark had met with and killed for us. He informed me by note that he would

proceed as fast as he could to the level country which lay to the S.W. of us.....to hunt until our

arrival. At one o'clock we halted on a small branch running to the left and made a hearty meal of

our horsebeef, much to the comfort of our hungry stomachs. Here I learned that one of the pack

horses with his load, was missing and immediately dispatched Baptiest LaPage, who was in

charge of him, to search for him. He returned at 3 P.M. without the horse. The load of the horse

was of considerable value, consisting of merchandise and all my stock of winter clothing. I,

therefore, dispatched two of my best woodsmen to search for him, and proceeded on with the

party."

"Our route lay through a thick forest of large pine, the general course being S 25 W about 15

miles. We camped on a ridge where there was but little grass for our horses and at a distance

from water. However, we obtained as much as served our purpose and supped on our beef."

Comment: Captain Lewis went up Hungery Creek and crossed over into the Fish Creek drainage

where he cooked lunch. He then went over the Lochsa Divide and camped on the ridge between

Dollar and Sixbit Creeks. This camp is not marked and, so far as I know, has never been located.

Sept. 21, 1805. Lewis: "We were detained this morning until 11 A.M. in consequence of not

being able to collect our horses. We set out and proceeded along the ridge on which we

encamped, leaving it at one and a half miles we passed a large creek (Eldorado) running to the

left just above its junction with another (Dollar) which runs parallel with and on the left of our

road before we struck the creek."

"Through the level, wide and heavily timbered bottom of this creek (Eldorado) we proceeded for

about two and a half miles, when bearing to the right, we passed a broken country heavily

timbered, great quantities of which had fallen, and so osbstructed our road that it was almost

impractical to proceed in many places."

"Through these hills we proceeded about five miles, when we passed a small creek (Cedar

Creek) where Capt. Clark had camped on the 19th. Passing this creek, we continued our route 5

miles through a similar country, when we struck a large creek (Lolo) at its forks."

"Passed the north branch (Lolo) and continued down it on the west side one mile and camped in

a small open bottom, where there was tolerable feed for our horses. I directed the horses be

hobbled to prevent delay in the morning, being determined to make an forced march tomorrow in

order to reach, if possible, the open country."

"We killed a few pheasants; I killed a prairie wolf (coyote), which together with our horsebeef

and some crawfish which we obtained in the creek, enabled us to make one more hearty meal,

not knowing where the next would be found."

Comment: Captain Lewis and party went down the ridge between Dollar and Sixbit Creeks,

crossed Eldorado Creek and went down it two miles. Clark gave a longer distance but Lewis

appears correct. Then they crossed over the ridge to Cedar Creek. From there they went to the

top of the ridge between Cedar Creek and Lolo Creeks. This ridge they followed to the mouth of

Eldorado Creek. Here they crossed Lolo Creek by a sign which designates it as "Wolf Camp".

The next day Lewis made it to Weippe Prairie.

Chapter 2

Lewis & Clark East

Starting at Weippe Prairie.

June 11, 1805. Clark: "Collected our horses early with intentions of

making an early start. Some hard showers detained us until 10 A.M. at which time we took our

final departure from the Quamash Flats (Weippe) and proceeded with much difficulty, due to the

slippery road. At nine miles we passed a small prairie (Crane Meadows) in which was quamash.

At two miles further we are at the camp of Fields and Willard on Collins Creek (Lolo). They

arrived at this creek last evening and killed another deer near the creek."

"Here we let our horses graze in a small glade and ate dinner. (This is the so-called Wolf Camp

on Lolo Creek.) After detaining about two hours, we proceeded on, passing the creek three times

and passing over some rugged hills and spurs, passing the creek on which I camped Sept. 17

(Cedar Creek). (Clark is in error. This should be Sept. 19.) Came to a small glade of about ten

acres thickly covered with grass and quamash near a creek (Eldorado) and encamped."

"We passed through bad fallen timber and a high mountain this evening. From the top of this

mountain I had an extensive view of the Rocky Mountains to the south and the Columbia Plains

for a great extent. Also in the southwest a range of high mountains which divides the Lewis and

Clark Rivers covered with snow."

Comment: Apparently the ridge between Cedar and Eldorado Creeks had been burned over,

because Clark complained of windfalls and was able to view the surrounding country much

better than you can do from this point today.

The Columbia Plains that he wrote about are, of course, the Nez Perce and Camas Prairies. The

high mountains between the Snake and Salmon Rivers are the Seven Devils.

June 16, 1806. Lewis: "We collected our horses very early this morning, took breakfast and set

out at 6 A.M. Proceed up the creek (Eldorado) about two miles through some handsome

meadows of fine grass, abounding with quamash. Here we passed the creek (Eldorado) and

ascended a ridge which led us to the N.E. about seven miles, when we arrived at a small branch

of Hungery Creek (actually a branch of Fish Creek). The difficulty we met with fallen timber

detained us so much we arrived at 11 A.M.

"Here is a handsome little glade in which we found some grass for our horses. We, therefore,

halted to let them graze and took dinner, knowing there was no other place suitable for that

purpose short of the glades on Hungery Creek, where we intended to camp.

"Before we reached this little branch on which we dined, we saw in the hollows and north

hillsides large quantities of snow, in some places two feet deep.....However, we determined to

proceed. Accordingly after taking a hearty meal, we continued our route through a thick wood

with much fallen timber and intersected by many small ravines and high hills."

"The snow increased in quantity so much that the greater part of our route this evening was over

snow, which has become sufficiently firm to bear our horses. Otherwise it would have been

impossible to pass, as it lay in masses, in some place 8 to 10 feet deep. We had much difficulty

in pursuing the road, as it was so frequently covered with snow."

"We arrived early at the place that Capt. Clark had killed and left the horse for us last September.

Here is a small glade in which there is some grass. Not a sufficiency for our horses, but we

thought it most advisable to remain here all night, as we anticipate if we proceed further we

should find less grass.....We came 15 miles today."

Comment: The party proceeded up Eldorado Creek, crossed it and then up the ridge between

Dollar and Sixbit Creeks, over the main divide into the drainage of Fish Creek, where they found

a small meadow and lunched. They then went over another divide into Hungery Creek and

camped at a small meadow. This meadow is unmarked and not on the maps but it is just below

Windy Saddle on the road to Boundary Peak.

June 17, 1806. Clark: "We collected our horses and set out early. We proceeded down Hungery

Creek about seven miles, passing it twice. We found it difficult and dangerous to pass the creek

in consequence of its depth and rapidity. We avoided two passes of the creek by ascending a

steep, rocky difficult hill."

"Beyond the creek the road ascends the mountains to the height of the main ridges, which divides

the waters of the Kooskooske (Lochsa) and Chopunnish (North Fork) Rivers. This morning we

ascended about 3 miles, when we found ourselves enveloped in snow from 8 to 12 feet deep,

even on the south side of the mountains."

"I was in front and could only pursue the direction of the road by the trees which had been peeled

by the natives for the inner bark, which they scrape and eat. As these trees were scattered, I with

great difficulty, pursued the direction of the road one mile further to the top of the mountain,

where I found snow from 12 to 15 feet deep. Here it was winter with all its rigors. The air was

cold and my hands felt benumbed."

"We knew it would require 4 days to reach the fish weir at the entrance of Colt Killed Creek

(White Sand), provided we were so fortunate as to be able to follow the proper ridge of

mountains to lead us there. Of this all of our most expert woodsmen and experienced guides

were extremely doubtful. Short of that point, we could not hope for any food for our horses."

"If we proceeded and should get bewildered in these mountains, the certainty was that we would

lose all our horses and consequently our baggage, instruments, perhaps our papers, and then

eventually risk the loss of our discoveries which we had already made, if we should be so

fortunate to escape with life.....Under these circumstances we decided it madness in this stage of

the expedition to proceed without a guide."

"We, therefore, came to the resolution to return with our horses while they were yet strong and in

good order, and endeavor to keep them so until we could procure an Indian to conduct us over

the snowy mountains. Having came to this resolution, we ordered the party to make a deposit of

our baggage which we did not have an immediate use for; also the roots, bread or cowis which

they had, except an allowance for a few days to enable them to return to a place at which we

could subsist by hunting until we obtained a guide."

"Our baggage being on scaffolds and well covered, we began our retrograde march at 1 P.M.,

having remained about three hours on the snowy mountain. We returned by the route we

advanced from Hungery Creek which we ascended about two miles and camped.....The party was

a great deal dejected, though not as much as I anticipated."

Comment: The mountain on which the baggage was deposited is just west of Sherman Saddle

and although it is unnamed on the map it is locally known as Willow Ridge. Their camp that

night was on the south side of Hungery Creek. It is marked on the ground with an iron post.

June 18, 1806. Clark: "This morning we had considerable trouble in collecting our horses, they

having straggled off to a considerable distance in search of food on the sides of the mountain in

thick timber. At 9 o'clock we collected them all except two, one of which was Shield's and one

Drewyers. We set out leaving Shields and LePage to collect the two horses and follow us.

"We dispatched Drewyer and Shannon to the Chopunnish Indians in the plains beyond the

Kooskooske in order to hasten the arrival of the Indians who promised to accompany us, or to

procure a guide at all events, and rejoin us as soon as possible. We sent by them a rifle, which we

offered as a reward to any of them who would engage to conduct us to Clark's (Bitterroot) River

at the entrance of Travelers Rest (Lolo) Creek. We also directed them, if they found difficulty in

inducing any of them to accompany us, to offer the reward of two other guns to be given to them

immediately, and ten horses at the falls of the Missouri (Great Falls, Montana)."

We had not proceeded far this morning before J. Potts cut his leg very badly with one of the large

knives. He cut one of the large veins on the inner side of the leg."

"Colter's horse fell with him in crossing Hungery Creek. He and his horse were carried down the

creek a considerable distance, rolling over each other among the rocks. He fortunately escaped

without much injury or the loss of his gun. He lost his blanket."

"At 1 P.M. we arrived at the glade where we dined on the 16th. Here again halted and dined. As

there were some appearance of deer about this place, we left J. and R. Fields with directions to

hunt this evening and tomorrow morning at this place and join us tomorrow evening at the

meadows on Collins (Lolo) Creek, where we intend to stay tomorrow to rest and hunt."

"After dinner we proceeded on to the fork of Collins Creek (Eldorado) and camped in a pleasant

situation at the upper part of the meadows about two miles above our encampment of June 15.

We sent out several hunters, but they returned without killing anything. They saw a number of

large fish in the creek and shot at them several times without success. We ordered Gibson and

Colter to prepare giggs in the morning to take some of the fish. The hunters saw much fresh

appearance of bear, but very little deer sign. We hope by means of the fish and what deer and

bear we kill to subsist until our guide arrives, without the necessity of returning to the Quamash

Flat (Weippe). There is an abundance of food here to sustain our horses. . . . Mosquitoes

troublesome."

Comment: The party retraced its route to Eldorado Creek and camped at the mouth of Dollar

Creek. The present Forest Service road crosses Eldorado Creek at this point.

The mosquitoes at Eldorado Meadows come after you in swarms in the spring of the year. I don't

see how they endured them.

June 19 and 20, 1806: The party stayed at Eldorado Meadows hunting, fishing, and fighting

mosquitoes. Hunting was poor so they decided to return to Weippe Prairie. The lost horses were

not found.

June 21, 1806. Lewis: The party returned to Weippe and "found ourselves at our old

encampment". They met two Indians enroute who had part of their lost stock, which included a

mule.

June 22 and 23 were spent at Weippe hunting with very good success. At 3 P.M. of the 23rd

Shannon and Drewyer returned with three Chopunnish guides.

June 24, 1806. Lewis: "We collected our horses early this morning and set out, accompanied by

our three guides .....we nooned it at Collins Creek .....After dinner we continued our route to Fish

(Eldorado) Creek, a branch of Collins Creek where we had lain on the 19th and 20th. We had

fine grass for our horses this evening."

Comment: With food, good horses and three expert Nez Perce guides, they were ready to make a

second assault on their much feared foe, the Bitterroot Mountains. Notice in the next few days

that these guides never miss. They waste no time looking for the trail and camp at horse feed

every night. It is unfortunate that none of those who kept diaries gave the names of their Nez

Perce guides. Some Indians say one the guides was a son of Twisted Hair and another the son of

Red Grizzly.

On their trip east in 1806 Lewis and Clark camped at Eldorado Meadows for

two days of hunting, fishing, and fighting, "troublesome mosquitoes."

The Lolo or Lewis and Clark Trail is still visible today atop the ridge which

divides the Kooskooskee (Lochsa) and Chopunnish (North Fork of the

Clearwater) Rivers.

June 25, 1806. Lewis: "Last evening the Indians entertained us by setting the fir trees on fire.

They placed a great number of dried limbs near the trunk, which when set on fire creates a very

sudden and immense blaze from bottom to top of these tall trees. They are beautiful in this

situation at night. This exhibition reminded me of a display of fireworks. The natives told us that

their object in setting the trees on fire was to bring fair weather for our journey."

"We collected our horses at an early hour this morning. One of our guides complained of being

unwell, a symptom I did not much like, as such complaints with an Indian is generally the

prelude to his abandoning any enterprise with which he is not well pleased. We left them at our

encampment and they promised to pursue us in a few hours."

"At 11 A.M. we arrived at the branch of Hungery Creek, where we found R. and J. Fields. They

had not killed anything. Here we halted and dined and our guides overtook us. (This is the third

time that they nooned it here.) After dinner we continued our route to Hungery Creek and

encamped about one and a half miles below our camp of June 16.

"The Indians continue with us and I believe are disposed to be faithful to their engagements. I

gave the sick Indian a buffalo robe, he having no other covering except his mocassins and a

dressed elk skin without the hair."

"Drewer and Shields were sent on this morning to Hungery Creek in search of their horses,

which they fortunately recovered."

Comment: Being a retired forester and a firefighter I cannot help wondering how far the fires that

were set spread during the following summer.

June 26, 1806. Lewis: "This morning we collected our horses and set out after an early breakfast,

or at 6 A.M. We passed by the same route we had traveled on the 17th to our deposit on the top

of the snowy mountain to the N.E. of Hungery Creek. Here we halted two hours to arrange our

baggage and prepare our loads. We cooked and ate a hasty meal of boiled venison and cowis."

"The snow has subsided near four feet since the 17th. We now measure it accurately and found

from a mark we had made on a tree when we were last here on the 17th that it was then 10 feet

10 inches, which appeared to be about the common depth, though it is deeper still in some

places. It is now generally about 7 feet."

"On our way up this mountain we killed two of the small black pheasants (fool hens or Franklin

grouse) and a male of the larger dominecker or speckled pheasant (blue grouse).....The Indians

inform us that neither of these species drum. They appear to be very silent birds, for I have never

heard any of them make a noise in any situation."

"The Indians hasten to be off and informed us that it was a considerable distance to the place

which they wished to reach this evening, where there was grass for our horses. Accordingly we

sent out with our guides, who led us over and along the steep sides of tremendous mountains

entirely covered with snow except about the roots of trees, where the snow had sometimes

melted and exposed a few square feet of earth."

"We ascended and descended several lofty heights, but keeping on the dividing ridge between

the Kooskooske and Chopunnish Rivers, we passed no stream of water. Late in the evening,

much to our satisfaction and the comfort of the horses, we arrived at the desired spot and

encamped on the steep side of a mountain convenient to a good spring. There we found an

abundance of fine grass for our horses. This situation was the side of an untimbered mountain

with a southern aspect, where the snows, from appearance had been dissolved about 10 days. The

grass was young and tender, of course, and had much the appearance of a lawn."

Comment: The Indians were correct; neither the Franklin or blue grouse drum. But they do make

noises. During the mating season the male blue grouse makes a grunting sound, or ump—ump—

ump. The foolhen makes a snapping noise while strutting. The female of both species call their

young by clucking sounds.

The party camped at Bald Mountain, which has been a favorite camping ground for parties

traveling the Lolo Trail due to its abundant grass.

June 27, 1806. Lewis: "We collected our horses and set out. The road still continues on the

heights of the same dividing ridge on which we traveled yesterday for 9 miles to our camp of

Sept. 17. About one mile short of this camp, on an elevated point, we halted by the request of the

Indians a few minutes to smoke the pipe."

"On this point the natives have raised a conic mound of stones of six or eight feet high, and on its

summit erected a pine pole 15 feet long. From thence, they inform us, that passing over with

their families some of the men were usually sent on foot by the fishery at the entrance of Colt

Killed Creek (White Sand) in order to take fish and again meet the main party at the Quamash

Glade (Packer Meadows) at the head of the Kooskooske River."

"From this place we had an extensive view of the stupendous mountains, principally covered

with snow like that on which we stood. We were entirely surrounded by these mountains, from

which, to one unacquainted with them, it would seemed impossible ever to have escaped. In

short, without the service of our guides, I doubt much whether we, who once passed them, could

find our way to Traveler's Rest Creek (Lolo, Montana). These fellows are most remarkable

pilots. We find the road wherever the snow has disappeared, though it be only for a few paces."

"After smoking the pipe and contemplating this scene we continued our march, and at the

distance of three miles, descended a steep mountain and passed two small branches of the

Chopunnish River just above their forks, and again ascended the ridge on which we passed

several miles, and at a distance of seven miles arrived at our encampment of Sept. 16, near which

we passed three small branches of the Chopunnish River and again ascended the dividing ridge,

on which we continue 9 miles, when the ridge becoming lower and we arrived at a station very

similar to our encampment of last evening, though the ridge was somewhat higher and the snow

had not been so long dissolved. Of course, there was little grass. Here we encamped for the

night, having traveled 28 miles over these mountains without relieving our horses from their

packs or their having food."

"The Indians inform us that there are, in the mountains to our left, an abundance of mountain

sheep, or what they call white buffalo (mountain goats in the Blacklead area). We saw three mule

deer this evening but were unable to get a shot at them. We also saw several tracks of these

animals in the snow."

"The Indians inform us that there is a great abundance of elk in the valley about the fishery of the

Kooskooske River."

"Our meat being exhausted, we issued a pint of bears oil to a man, which with their boiled roots,

made an agreeable dish."

"Pott's leg which had been swollen and inflamed for several days, is much better this evening and

gives him but little pain."

Comments: The rock mound on which the Indians stopped to smoke is located on the first high

point west of Indian Grave. It is off the Lolo Motorway but on the old Lolo Trail. There is a

small rock mound there now, much smaller than the one Lewis and Clark described. It could be

the same mound much settled, or it may be that another one was erected. There are a number of

old rock cairns along the Lolo Trail. They camped at Spring Hill called Red Mountain by the

Nez Perce for the dock on it which turns red in the fall.

June 28, 1806. Clark: "This morning we collected our horses and set out early as usual, after an

early breakfast. We continued our route along the dividing ridge over knobs and deep hollows.

Passed our camp of Sept. 14 last near the forks of the road, leaving the road on which we had

come, one leading to the fishery on our right immediately on the dividing ridge."

"At 12 o'clock we arrived at an untimbered hillside of a mountain with a southern aspect just

above the fishery. Here we found an abundance of grass for our horses, as our guide informed us.

As our horses were hungry and much fatigued and from our information no other place where we

could obtain grass for them within the reach of this evening's travel, we decided to remain at this

place all night, having come 13 miles only."

Comment: Gass adds that they saw numerous elk tracks at this camp ground. This is the only

time elk tracks are mentioned in the Clearwater Valley.

The party has taken a shorter route than that taken westward and have arrived at Powell Junction

near the place where the road goes to Rocky Point Lookout.

June 29, 1806. Clark: "We collected our horses early and set out, having previously dispatched

Drewyer and R. Fields to warm springs (Lolo Hot Springs) to hunt. We pursued the heights of

the ridge on which we have been passing for several days. It terminated at the distance of five

miles from our camp and we descended to and passed the main branch of the Kooskooske

(Crooked Creek) one and a half miles above the entrance of Glade (Brushy) Creek, which falls in

on the N.E. side. When we descended from the ridge we bid adieu to the snow."

"Near the river we found a deer which the hunters had killed and left us. This was a fortunate

supply, as our oil was now exhausted and we were reduced to roots alone, without salt. The

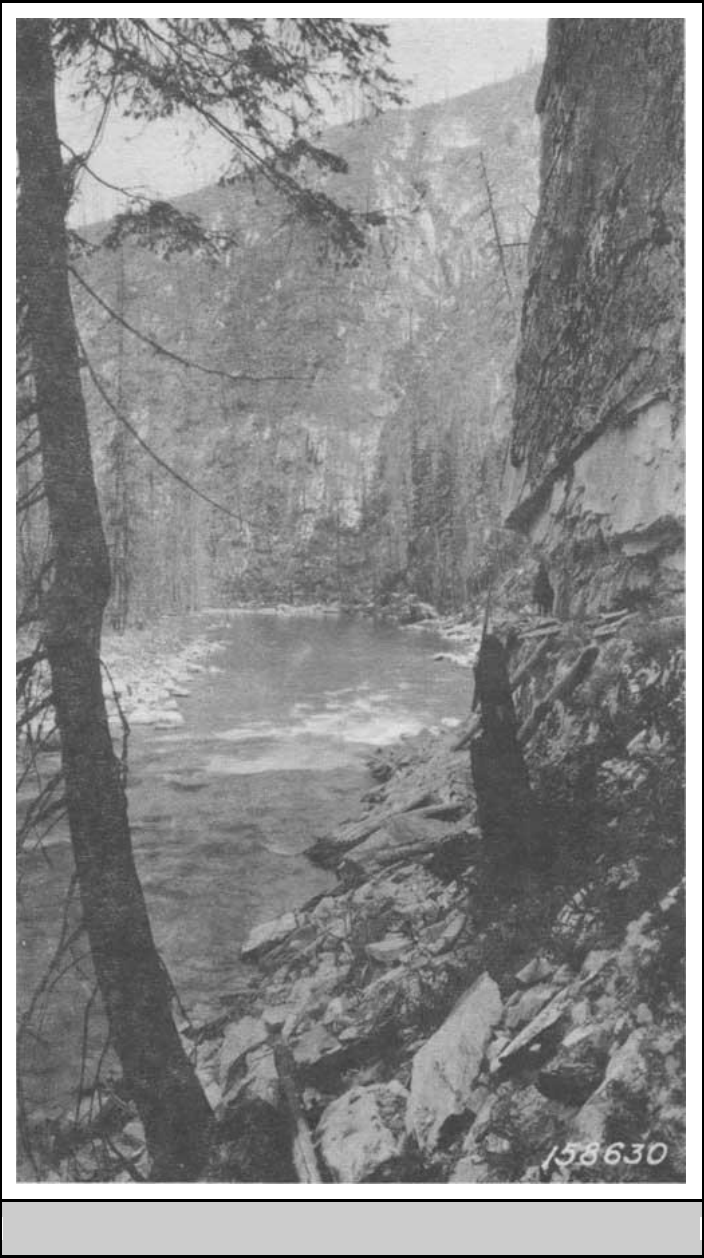

Kooskooske at this place is about 30 yards wide and runs with great velocity. The bed, as of all

the mountain streams, is composed of smooth stones."

"Beyond the river we ascended a very steep mountain about two miles, and arrive at the summit,

where we found the old trail by which we passed when we went west, coming in from the right.

The road was now much plainer and more beaten, which we were informed happened from

Ootshashoots (Flatheads or Salish) visiting the fishery frequently from the valley of the Clark's

(Bitterroot) River, though there was no appearance of their having been there this spring."

"At noon we arrived at the quamash flats and halted to graze our horses and dine, having traveled

12 miles. We passed our camp of Sept. 13 at 10 miles. We halted at a pretty plain of about 50

acres plentifully stocked with quamash and from appearances this forms one of the principal

stages or encampments of Indians who pass the mountains on this road."

After dinner we continued our march 7 miles to the warm springs where we arrived early in the

evening and sent out several hunters." (Here the warm springs are described. The party,

including the guides, bathe in the warm water.)

Comment: The ridge they were following ended at Rocky Point and they descended to and

crossed Crooked Fork Creek. They then climbed the ridge to the southeast and came to their old

trail, which they followed to Packer Meadows, lunching at the eastern edge. They then went to

Lolo Hot Springs and camped.

Chapter 3

The Lewis & Clark Grove

In 1954, I was at a logging operation in the Musselshell area when

Axeb Kludt, a logging contractor, asked me if I had ever seen the tree

in that locality that had Lewis and Clark's names carved on it. At first I

thought he was kidding, but he said no, that he had seen the tree when he was a teenaged youth

in a hunting party. I asked him for more particulars as to where it was, the kind of tree, etc., but

he could give no details.

This story seemed so unlikely that I passed if off as a wild dream and all but forgot it. I went to

Browns Creek Lookout a month or so later. The lookout that year was a lady from Weippe who

taught school in the winter and served as a lookout during the summer. She had been doing this

since the war when a shortage of men made it necessary for the Forest Service to hire women as

lookouts. (Today, most Forest Service lookouts are female.) While there, much to my surprise,

she mentioned the tree with Lewis and Clark's names on it. One person knowing about such a

tree could be disregarded, but when two people seemed to know about it there must, I concluded,

be something to the report. She had not seen the tree, nor could she recall who told her about it,

but she understood it was on the ridge between Eldorado and Lolo Creeks.

Since Lewis and Clark camped on Lolo Creek and went up this ridge a few miles, I decided I

would search this area for the tree. Accordingly, my teenaged son, Jim, and I went to the forks of

Lolo and Eldorado Creeks one Saturday and by a slow process of careful observation found

pieces of the old trail. We would follow each part as far as I could identify it and when it became

too dim to follow Jim would stand at the last point found while I would look ahead for further

clues. When I located another section of the trail we would move ahead again. When we came

near a large tree we would examine it. There were a number of large pine trees on this ridge, but

no Lewis and Clark tree.

Slowly we worked our way up this ridge and then down to where the old trail crossed Cedar

Creek, which is where Captain Clark camped. There was a grove of large trees here, but again,

no luck. We gave up the search.

I told the ranger at Pierce about looking for the Lewis and Clark tree. A few days later he sent

me a note saying that he had talked with Bob Richel of Pierce who told him Blayne Snyder knew

where the tree was. Now, Blayne Snyder was a retired Forest Service employee and had spent

many years in the Musselshell country, so my hopes were revived. I wrote to Blayne asking him

about this tree. He didn't answer my letter but came to my office. He said that he was ashamed

that he had been a party to such a deception and regretted that he had caused me so much trouble

for he had carved the names of Lewis and Clark on a tree as a joke. He told me where the tree

was, but I have never looked for it.

Two years later a timber sale and a road were planned for the Cedar Creek drainage. I went with

the ranger and a staff man to look it over before it was finally advertised for sale. We walked up

the road location and I found that the proposed road was well above the grove of trees where

Clark camped. We stopped to look at it and I explained to them what had happened there and

stated that I felt that this area should be reserved from any cutting. Jack Alley, the ranger, said,

"OK, you walk around the area you want excluded from the sale. I have a paint gun and I will

follow you and mark the area to be reserved" While marking the boundary we referred to the

area as "Clark's Camp". We also came upon a huge white pine tree which we called "Clark's

Tree". When the boundary was marked I got to thinking and told the ranger that Lewis did not

camp here, but since Lewis and Clark did everything as partners it would be better to call the

area the "Lewis and Clark Grove". This name was adopted for the grove, but Clark's name is still

applied to the big pine tree.

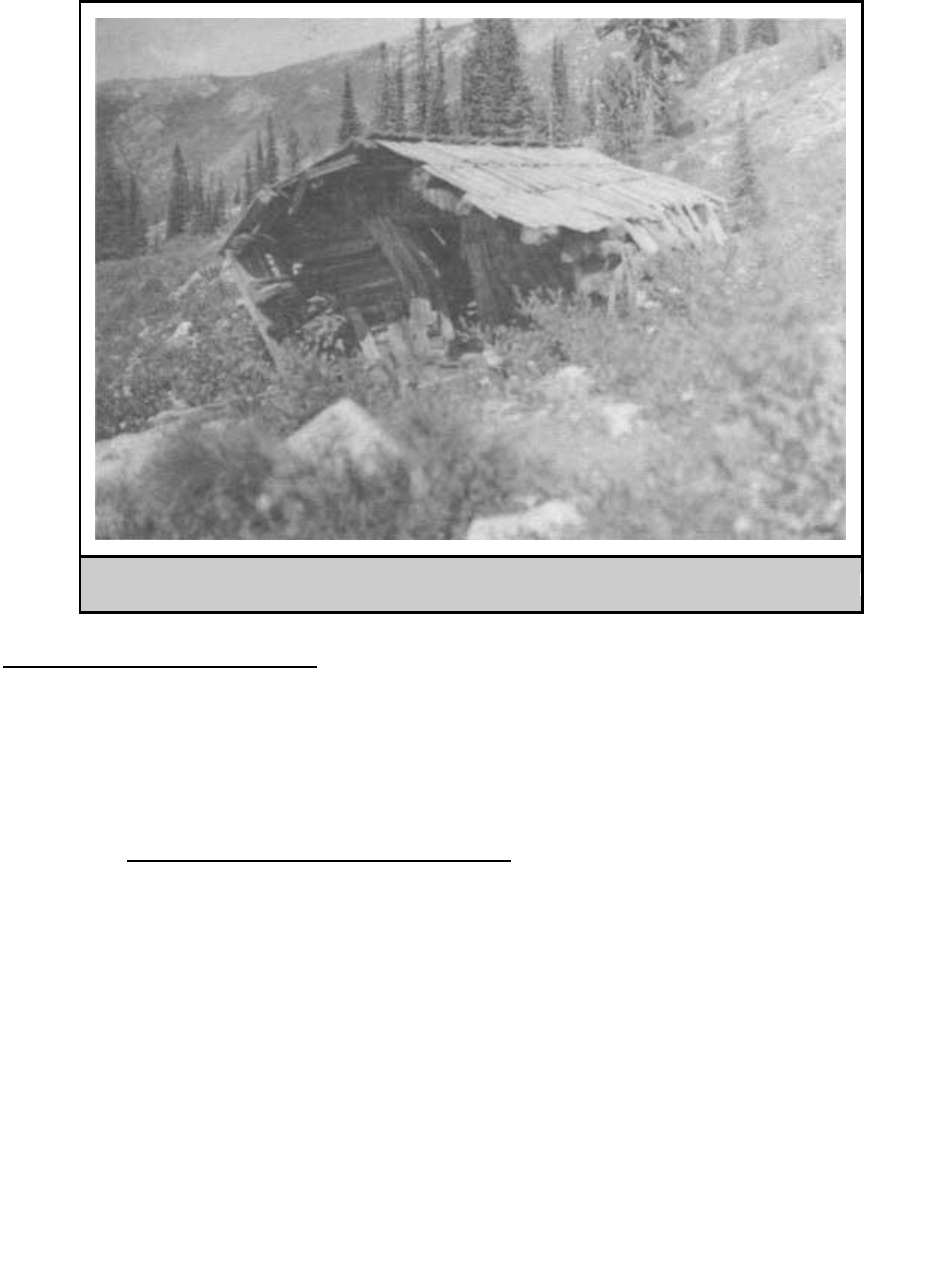

A few years after this grove was established a young forester (not in the Forest Service)

examined it and wrote a memorandum criticizing the action taken as wasteful and costly. He

pointed out that the huge pine trees are overmature and will die from one cause or another in the

not too distant future. He estimated the volume of white pine at about sixty thousand board feet,

which appears to be about right. The Clark tree alone is estimated to have a volume of about

thirteen thousand board feet. No doubt he is right about the pine trees. They are very old and one

by one they will die. They may live longer than we think. Twenty years have already passed and

they are still there. Before they die they will give many people the opportunity to look at a small

spot of virgin timber when such areas are all but gone forever. Furthermore, I can think of no

finer tribute to pay to the great explorers than having a grove of trees set aside in their honor.

My designation of the Lewis and Clark Grove was an administrative action within the authority

of the Forest Supervisor. It could have been revoked by the same action. However, the area was

soon withdrawn from mineral entry. Then when the Nez Perce National Historical Park came

into being this grove became one of the units to be administered jointly by the National Park and

Forest Services. It then became a National Historical Site and so it will remain.

Chapter 4

John Work

By 1831 the competition between the Hudsons Bay Company and the

American fur trappers for the fur trade had become quite keen. This

was especially true in Montana, Wyoming and South Idaho. To

challenge the fur traders in this area and to discourage further United States expansion westward,

John Work or Wark, left the Hudsons Bay post at Vancouver, across the Columbia River from

present Portland, in the fall of 1831. His party of between 35 and 60 men, women, and children,

including his wife and three daughters, reached Weippe on Sept. 26, 1831. There were Indians at

Weippe and they attempted to trade with them but they found the Nez Perce not interested in

beaver trapping and hard bargainers when it came to trading horses.

Sept. 30, 1831. They moved to a little valley the country there had been burned and was pretty

bare of wood. This, in my opinion, was Browns Creek, although some consider it Musselshell.

My opinion is based on the age of the timber. The trees at Musselshell before harvest in the

1950s were over 200 years old; those at Browns Creek about 130.

October 1, 1831. According to the log of the journey "It began to snow in the night and snowed

all day." It is very unusual for snow on October 1 at this elevation, but not for the Lolo Trail.

October 2. The party started over the Lolo Trail and made 24 miles "over very steep hills and

thick woods" and "encamped in a deep valley." Here there was no grass and the horses ate

"bramble and briars. We have now fallen on the great road."

Some say that this camp was at Deep Saddle and the description would fit except for the

statement that they had reached the "great road". This would have to be the trail as followed by

Lewis and Clark and that makes it Sherman Saddle, since the trail followed by Lewis and Clark

turned down into Hungery Creek on the ridge west of Sherman Saddle. There are no clues as to

where the trail followed by Work ran, but apparently it was close to the Lolo Trail as established

by Bird in 1866.

October 3. The party made 17 miles through 9 inches of snow and camped by grass. This puts

them at Bald Mountain.

October 4. Storms prevented travel. The day was spent looking for missing horses.

October 5. More snow fell. The party moved 15 miles, which put them at Camp Howard. There

was grass covered with snow, "so the starving horses could not get it."

October 6. The snow continued and more horses were lost. One horse died, another "gave up."

The location of their camp is uncertain, but it appears to have been at Cayuse Junction.

October 7. Stragglers catching up with the main party report six feet of snow on the higher

elevations to the west. This would be Indian Post Office and Spring Hill. Less than a foot of

snow at the camp site. There is no horsefeed at Cayuse Junction.

October 8. The snow turned to rain as they move to a lower elevation. They made 15 miles and

camped on Crooked Creek. Again, no horsefeed.

October 9. Eight miles further and they reached Packer Meadows. "There is a good deal of good

grass for the horses, of which they are in much need." Here they camped for three days to rest

and give the horses an opportunity to feed on good grass.

October 13. They move to "a small plain at a hot spring." This is Lolo Hot Springs.

Thus the second known white party crossed the Lolo Trail. They found it just as difficult as their

predecessors, Lewis and Clark. They returned to Vancouver by way of South Idaho.

Chapter 5

Captain John Mullan, U.S. Army

Captain Mullan was directed to explore the possibilities of constructing

a military road from Walla Walla, Washington to Fort Benton, now in

Montana. His field examination started in 1853 and was completed in

1854. He first interviewed the Indians, hunters and priests who had traveled the country. He soon

learned that a route from Fort Benton to Missoula was not difficult and in March, 1854, he

brought a wagon over this part of the route, reaching Missoula locality on March 31. This

narrowed his explorations down to finding a route from Missoula to Walla Walla, which was not

easy.

He explored all possible routes, going over the Lolo Trail in September, 1854. The following is

quoted from this report of 1863:

"In September, 1854, my party having been ordered in from the field, I decided to proceed to the

coast by a new route, and the only one left unexplored, namely, via the Lo—Lo Fork Pass; not

that I felt or believed it to be practical for wagons, but more with a view to arm my judgement

with such facts as would not leave a shadow of a doubt behind which would cause us to error in

the final conclusion in so important a matter. This route I found the most difficult of all

examined. After eleven days of severe struggle with climate and country we emerged into the

more open region where "Oro Fino" now stands, glad to leave behind us so difficult a bed of

mountains. After examining all these passes my judgement was finally decided in favor of the

line, via the Coeur d'Alene Pass, as a proper connection for a road leading from the head of

navigation on the Columbia to that on the Missouri, and the result was so reported to Governor

Stevens, under whose direction I was then acting".

The three principal routes examined by Captain Mullan were the Clarks Fork, St. Regis-Coeur d'

Alene, and Lolo Pass. The Burlington Northern and Highway 10 follow the two northern routes

and Highway 12 the Lolo Pass. Considering the road building equipment of the time, no doubt

Mullan picked the most practical route.

Notice that the name Lo—Lo was well established in 1854. The Oro Fino of 1863 was not the

Orofino of today, but a mining town close to the present town of Pierce.

Chapter 6

Wellington Bird & Major Truax

Gold was discovered in Pierce late in the year 1860 and a rush to the

gold fields of the Clearwater took place in 1861. At first Walla Walla

was the base of operations, but a town was soon established at Lewiston

and it served as the taking off point and center of supplies. Gold was soon found at Elk City and

Florence and then in 1863 the big find was made at Alder Gulch in what is now Montana.

The base of supplies for the towns on Alder Gulch, the largest of which was Virginia City, was

Salt Lake City, Utah. Lewiston tried to get in on the trade and some men, such as Magruder, took

supplies to Virginia City by pack train, going over the Nez Perce Trail. But Salt Lake had a

distinct advantage over Lewiston because freight could be hauled from there by wagon. So the

merchants of Lewiston promoted a wagon road east by way of Lolo Pass. There was a road to

Pierce and they reasoned that it would be practical to make a shorter route to Montana by

building a road through the mountains to Missoula. Some citizens of Lewiston even formed a

corporation to build a toll road but they never got started.

Pressure was brought on Congress to build such a road and in 1865 Congress, always in favor of

promoting development of the West, appropriated $50,000 to construct a road through Lolo Pass.

Little did anyone realize the difficulties involved. It was 74 years before this dream was fulfilled.

Although the appropriation was made in 1865, the Secretary of the Interior could not find an

engineer who would undertake the job. The pay was $2,000 a year, a fair sum at that time in the

East but not much in Idaho Territory in 1865, where prices and wages were much higher.

Mr. Wellington Bird was hired as the Chief of Party in 1866 and George B. Nicholson his

assistant. Professor Oliver Marcy, a botanist and zoologist from Northwestern University, was to

accompany the party, but he made a quick trip over the Lolo Trail while the snow was melting in

the spring and missed an opportunity to make a worthwhile contribution to science.

Bird's original plan was to assemble an outfit in the East and move it to Lewiston but after

consultation with the Secretary of Interior he discarded this idea and took passage on March 10,

1866 by boat to Portland. Here Bird and his aids bought some road building equipment. They

then moved to Lewiston arriving May 1, 1866. At Lewiston, Bird spent considerable time talking

to people about the geography of the country and making final preparations for an assault on the

Lolo Trail.

The party left Lewiston on May 24. It was a sizable outfit consisting of Wellington Bird, George

Nicholson, Oliver Marcy, Major Sewell Truax, one time commander of Fort Lapwai, William

Craig, cooks, teamsters, blacksmiths, etc. They were well equipped with a plow, shovels, axes,

wagons, tents, stoves, medicine chest, mess outfits, blankets and food for 60 men for six months.

All this cost about $20,000 leaving about $30,000 to be spent on the job.

They took the road to Weippe, going through Lapwai and over the Nez Perce Prairie, crossing

the Clearwater River at Schultz's Ferry, now Greer. In the meantime Bird had gone ahead and

scouted the area. The prospects for a road were anything but bright. There was six feet of snow

in the mountains and the country was covered with a dense forest with heavy underbrush and

plenty of windfalls. It was a dismal prospect but Bird could not find any route that was better.

Bird then notified the Department of Interior that it was not possible to build a road through the

mountains for $50,000. He said he would survey a route for a road and then attempt to build a

trail on that location that could later be developed into a road. In the meantime, the Lewiston

sponsors of the road would probably be less demanding.

Even a survey was difficult. The forest and brush were so dense that axemen were required to

open a line of sight. The country was steep and camping sites few and far between. The survey

took a month. Bird arrived at the mouth of Lolo Creek in Montana on July 7 and his party was

utterly exhausted.

Bird then returned to his construction crew over the Lolo Trail. He had sent his assistant, George

Nicholson, Major Truax, and Tahtutash over the Southern Nez Perce Trail. They made the trip

from Fort Owen to Elk City in eight days, which was something of a record for that time.

Nicholson reported that the Lolo Trail was the better route. Sometimes we see statements that the

Southern Nez Perce Trail was an easier route than the Northern route, the Lolo Trail. Actually

both routes were very difficult and either way a traveler went he would likely wish he had taken

the other. One thing that may have confused people is that the Forest Service completely

relocated and rebuilt the Southern Nez Perce Trail. Still later they replaced this trail with a

motorway. Many people mistake segments of the Forest Service Trail as parts of the Old

Southern Nez Perce Trail.

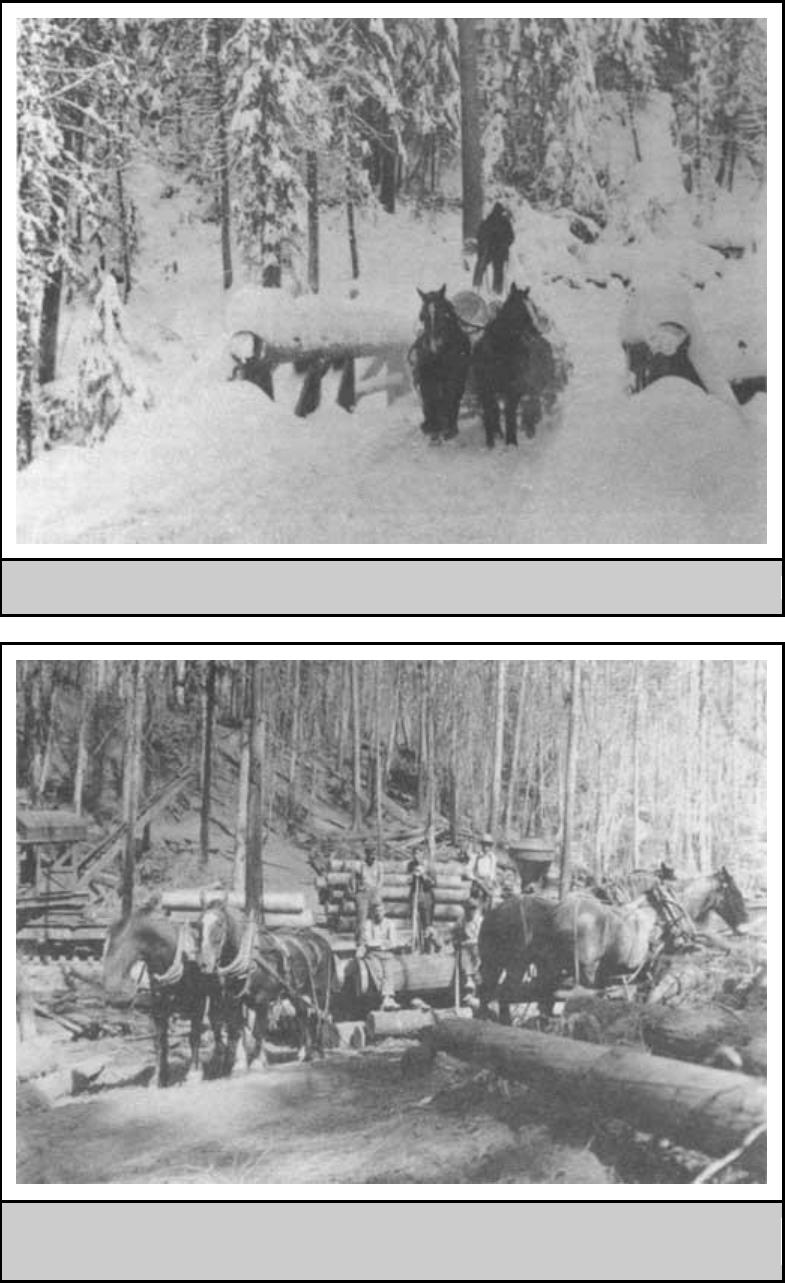

While Bird and his surveyors were locating a trail across the mountains the crew widened the

trail from Weippe to Musselshell into a road and moved to Musselshell. A large part of this road

was on the same location as the road today.

The party spent the months of August and September in building the Lolo Trail. Several

important changes were made in the trail as followed by Lewis and Clark. Bird changed the trail

from Indian Post Office to Indian Grave Lookout, following along the main divide. He also

changed the trail from Sherman Saddle to Weippe. Instead of dropping into and climbing out of

Hungery Creek he rerouted the trail along the main divide to Snowy Summit, thence to

Musselshell, Browns Creek and Weippe. He graded from saddle to saddle, thus eliminating many

steep sections and generally easing the grade.

Bird built a very good trail. Trees did fall across it and since no one was responsible for keeping

it open it became clogged with windfalls. But its route remained practically unchanged from

1866 until it was replaced by a motorway in 1934, a period of 68 years. So the money was well

spent.

In September, Bird realized that winter was near in the mountains. There remained $8,000 of the

appropriation. So Bird turned everything over to Major Truax and went to Washington. The

Secretary of the Interior, knowing little about local conditions, was displeased that the project

had been suspended and that Bird had taken it upon himself to appoint his successor.

The Idaho Territorial Legislature asked Congress for $60,000 to continue the project, but

Congress would not appropriate the money so the project came to an abrupt end.

Apparently the Bird construction crew named several features along the Lolo Trail. Snowy

Summit, Rocky Ridge, Sherman Peak, Sherman Creek, and Indian Post Office are all names that

were probably first used by Bird's Crew.

CHIEF JOSEPH and GENERAL HOWARD

The next well-known trip over the Lolo Trail came several years later during the so-called Nez

Perce War. After the engagement between General Howard and Chief Joseph near Stites, the

Indians retreated to Weippe. They arrived July 15, 1877. At that time there were only a few

ranches in the Weippe vicinity, belonging to Martin Mauli, Wellington (Duke) Landon,

"Grasshopper" Jim Clark and John Reed. These people fled to Pierce where a makeshift

fortification was put together.

The Indians burned the ranchers' buildings and, having lost a greater part of their food supplies at

Stites, they proceeded to kill the ranchers' cattle and dry the meat.

At Weippe, the Indians held a war council. They had to make a tough decision. Some of the

Indians, including Joseph, wanted to negotiate a peace treaty. Others, particularly those who

thought they and their friends might be hanged for murder, wanted to continue the war. All the

chiefs were convinced that they could not whip General Howard without assistance. They were

faced with deciding whether they should negotiate a peace, flee to Canada, or seek aid from the

Flathead or Crows who had always been their friends. Finally they decided to go to the Crow

country and, if need be, later go to Canada. The Nez Perce, particularly Looking Glass, had

always been on the friendliest terms with the white people in Montana and the Crows and had

every reason to believe they would experience no difficulty there; a hope that led to bitter