0

1

Submission Date.

01/03/2024

Group members.

Benjamin David Murphy

Bianca Seong

Hannah Holoubek

Kamana Rai

Teachers.

Saadi Lahlou

Maximillian Heitmayer

2

Table of Contents

Case Background · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 3

1 Introduction · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 4

1.1 Rationale

2 Analysis · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 5

2.1 Stakeholder relations and motive · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 7

2.1.1 Festival Stakeholders

2.1.2 Stakeholder Key Motives

2.2 Festival timeline & Intervention opportunities · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 8

2.2.1 Timeline

2.2.2 Windows of opportunities

Window 1 - Planning phase

Window 2 - Pre-festival after ticket purchase

Window 3 - Operation and engagement

Window 4 - Evaluation

3 Solutions · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 13

3.1 Theoretical backgrounds · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 13

3.1.1 Gamification and Self-Determination Theory

3.1.2 Integrating Digital Channels into the festival experience

3.2 Solutions Overview · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 14

3.3 Breakdown · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 15

3.3.1 Window 1

3.3.2 Window 2

3.3.3 Window 3

3.3.4 Window 4

4 Conclusion · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 28

4.1 Limitations

5 References · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 31

6 Appendix · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 35

3

Case Background

Music festivals are an ever-present part of modern life; even during the global

financial crisis in 2008, notable ticketing site LiveNation suffered no slowdown

(Ashdown, 2010). With the UK falling into recession, there may be no better time

than now to focus on nurturing the growth of sustainable music festivals to prosper

both the industry and the planet (Ziady, 2024). Research highlights numerous

benefits of music festivals; engagement with music in a festival fosters a sense of

community, binds group members together as part of a shared culture, and creates

an environment to engage in social activities (Frith, 1996). On an individual level,

music festivals offer opportunities for attendees to be introspective by defining,

developing, and reflecting on personal understandings to cultivate new expressions

of self-identity (Karlsen & Brändström, 2008; Matheson, 2005).

Festivals are unique as they enforce a sense of community amongst attendees,

where one’s identity can be shared and celebrated (Karlsen & Brändström).

Additionally, they mark the passing of time and give people an opportunity to

strengthen their social network (Brennan et al., 2019). They also act as a platform to

spread political messages and preserve social capital, which serves as the

framework to facilitate the actions of individuals (Mair & Laing, 2012). Although

efforts have been made to promote the social pillar of sustainability, issues become

salient when attention is exclusively localised to portable communities, thus the

traditional evanescence of music festivals (Richardson, 2018). The neglect of the

local community is a gap in the literature, which the current paper aims to address.

Music festivals are often identified as the key drivers of local economies, either

through direct contribution or by enhancing a city’s image and appeal. It gives the

host city a sense of identity and self, a cultural imprint which is identified to be

essential in urban development and survival (Ashdown, 2010). Taylor Swift’s “Eras”

tour boosted the local economy of every host city, e.g. $97M in Cincinnati (Cain,

2023). Although the economy may be reaping the rewards, large-scale music

festivals are causing negative externalities that the planet cannot afford. Air New

Zealand was required to add 14 more flights to accommodate an extra 3,000

attendees travelling to the concert (Dolsak & Prakash, 2023.). Yard (2024) found

4

Taylor Swift to be the biggest polluter, with her annual CO

2

e being 1,184.8 times

more than the average person’s. Hence, it is apparent that the hedonistic

consumption encircling music festivals carries both negative and positive

consequences. To begin solving this Wicked problem, music festivals need to be

better understood (Voss et al., 2003; Lönngren & van Poeck, 2021).

Demand for sustainable music festivals is driven by attendees who have an

increased awareness of environmental sustainability and expect a certain level of

sustainability from the organisers (Mair & Laing, 2012). Consumers are increasingly

displaying pro-sustainable behaviours at music festivals; 62% of attendees are

pushing for improved recycling facilities (Strout, 2019). Although the industry is

thriving, attendees are vigilant of its contribution towards overconsumption of non-

renewable resources and air pollution (Wang et al., 2014). Instead, perceptions of a

festival’s green status is directly correlated with attendees’ intentions to behave

sustainably (Martinez-Vazquez & Bird, 2014).

1. Introduction

“Burning Man, in a burning world” encapsulates the present reality of music festivals

(Foster, 2023). Flash floods, extreme heat and bushfires are just some examples of

the devastations endured at music festivals as a result of anthropogenic climate

change; 75,000 attendees were trapped in mud in the Burning Man incident in 2023,

resulting in fatality (Deliso & Hutchinson, 2023). In the last decade, over a million

attendees gathered at music festivals in the UK, and with this came an immense

volume of waste and consumption. Research shows that a music festival of more

than 40,000 people will produce 2000 tons of CO

2

e, and in 2020 Reading Festival

hosted approximately 105,000 attendees (Ashdown, 2010; Walker, 2022). This

highlights a growing requisite for implementing sustainable measures to secure the

future of music festivals.

5

1.1 Rationale

Music festivals are, for visitors and locals, a temporary phenomenon, fast-paced and

short-term, exploiting natural built and sociocultural resources (Smith, 2012).

Conversely, sustainability is defined as development which meets the needs of today

without compromising the ability to meet the needs of the future generation; it is an

enduring and resilient form of development (International Institute for Sustainable

Development, 2024; Smith, 2012). It is imperative to note the juxtaposition of

sustainability and the transient nature of music festivals which becomes the basis of

the present study’s rationale. As such, these recommendations aim to redesign

music festivals to increase longevity through the triple-bottom-line framework (social,

economic, and environmental pillars). They also seek to analyse pain points (see

Appendix 1) and complex stakeholder relationships to identify where motives interact

along the festival journey and strengthen the social pillar through community-focused

interventions (Alhaddi, 2015). Analysis and interventions will be rooted in

psychological theories and frameworks such as Installation Theory (Lahlou, 2017),

Gamification (Pelling, 2011) and Systems Thinking (Meadows, 2008) to transform

music festivals into long-term and sustainable events which foster economic, social,

and environmental growth.

2 Analysis

Installation Theory and Problem Outline

The greater the disagreement and discrepancy in the understanding of stakeholders,

the more Wicked the problem becomes (Lönngren & van Poeck, 2021). Installation

Theory (see Table 1) and Activity Theory (see Table 2) are implemented (Lahlou,

2017) to identify where stakeholder motivations align and what reward or currency

can be exchanged between parties.

Installation theory has been successful in changing people's behaviour within

industries using its three components (affordances, embodied competencies, and

institutions). It is important to note how, in installation theory, behaviour change is

best targeted at the time and place where the activity is performed - the ‘point of

action’. This is where activity theory plays a crucial role. Activity theory divides a

behavioural sequence into segments, with each segment representing a task

completed in pursuit of a subgoal, with subgoals being driven by an overall motive. In

6

this case, activity sequences are developed for each stakeholder. At each step in the

activity sequence, the relevant installation is then considered. The use of activity

theory provides a robust framework for breaking up complex behaviour into

manageable units of analysis. Each stakeholder is considered, in turn, to manage

interrelating motives (both aligned and unaligned) and relevant power dynamics.

Installation theory is especially useful in understanding how social and environmental

structures channel cooperative behaviour, which is imperative in shaping

sustainability. Furthermore, installation theory’s flexibility and pragmatic focus make

it a strong analytical fit for understanding and changing behaviour in and around

music festivals.

Table 1. Problem analysis of installations (see Appendix 2 for full table)

Table 2. Example of Activity step analysis (Host Organisation)

Activity step

Motivation

Expected Contribution

Rewards

7

2.1 Stakeholder relations and motive

2.1.1 Festival Stakeholders

The foundation for connecting stakeholders is dependent on the outcome where the

benefits of collaborations will outweigh the costs (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). The

following stakeholders have been identified as central to a music festival's

operations: host organisations, government authorities, local communities, visitors,

volunteers, artists, sponsors, and staff (contractors).

2.1.2 Stakeholder Key Motives

Informal norms of reciprocity are involved where stakeholders contribute to gain

reward. This includes self-interested profit motives (e.g. host and staff) as well as

fostering social connections (e.g. volunteers and visitors) and broader non-

financial motivations. All stakeholders possess a varied group of motives for

involvement. For example, the local community may leverage the festival to

generate revenue, celebrate, socialise, and foster community pride (Yolal et al.,

2016). Accordingly, we have identified key stakeholder motives, including the

currency they value and exchange with, as well as their push and pull factors (see

Table 3).

Host

organisation

Authorities

Local

community

Visitors

Volunteers

Artists

Sponsor

Support and

loyalty,

standing out

in the

market

Opportunity for

political

communication

Cultural

celebration

and

exchange

Novel

experience,

Meeting

new people

Meeting

like-

minded

people

Interaction,

building

relationship

with future

fans

Building

customer

relation

All stakeholders are seeking economic or/and non-economic opportunities through connection

Table 3. Stakeholder motives

8

2.2 Festival timeline and intervention opportunities

2.2.1 Timeline

Re-formulating the festival timeline as a year-long process rather than a brief one-

time affair provides many intervention points. The festival timeline was produced

using activity theory to capitalise on this benefit. (see Figure 1)

2.2.2 Windows of opportunities

The respective stakeholder touchpoints and current platforms are further explored

through the stakeholder journey map (see Figure 2). A touchpoint refers to points

of interaction between multiple stakeholders, and a platform refers to a digital or

physical location/place which facilitates said interactions. Four windows of

opportunity were identified and informed by the activity timeline and journey

analysis. This was constructed considering differences in stakeholders’ interests,

contributions, and engagement throughout the festival timeline. Key actors

(stakeholders) and windows of opportunity are defined below; further analysis is

detailed in the solutions section.

9

Figure

1. Festival Timeline

10

Figure

2. Stakeholder Journey map

11

Window 1: Planning phase

Window 1 concerns the planning phase of the festival. This is the first stage of the

12-month process in which the fundamental aspects regarding festival operations

are decided, including budgeting, logistics and marketing (Eventbrite, 2023).

Concerns identified here include social and financial support for the host. As such,

for a successfully sustainable festival, it is essential to intervene during planning.

Further, to manage the risks and benefits and ensure the festival is an overall

positive for locals, engagement during planning is necessary. Getz & Jamal (1994)

highlight how getting cooperation from the local community is essential to running a

successful festival, and Mair & Laing (2012) identify the level of commitment of locals

to be integral in deciding the sustainability of a festival. Engaging early with locals

allows surplus time to organise the festival to meet their needs and ensure a

sustainable experience. We acknowledge interventions at this window do not

address the above-mentioned financial concerns for the host, but earning preliminary

social support from stakeholders may go a long way in mitigating these concerns,

presenting a scope for further research. Both limitations and directions for future

research will be discussed.

Window 2: Pre-festival after ticket purchase

This window consists of the ticket purchase stage, alongside the time between ticket

purchase and the festival. At ticket purchase, attendees have displayed high levels of

interest and are already engaged with the music festival. Despite this, there is a

stagnation in activity between ticket purchase and the festival date, thus a missed

opportunity to leverage this excitement. This period of stagnation can span as long

as seven months (Glastonbury Festival, 2023). Accordingly, this window is best

placed to design interventions to rectify this. Furthermore, this missed opportunity

signifies the transient nature of a festival reduced to three days as opposed to seven

months and beyond. Resources from other stakeholders such as artists, sponsors,

and locals remain to be leveraged to utilise this intermedial time. This point of action

represents optimistic avenues for shaping sustainable behaviour even before the

festival takes place (Lahlou, 2017).

12

Window 3: Operation and engagement

Window 3 is where the operation and engagement of the music festival takes place;

all stakeholders are engaged and involved during this stage. Interventions here are

on the event itself, rendering it significant and perhaps one of the most effective

windows in achieving sustainable goals. Accordingly, the bulk of the negative

externalities associated with the festival occur in window 3 (see Table 4). On the

other hand, the number of problems involved allows for a wide range of possible

Interventions.

Table 4. Problem Analysis for W3

Window 4: Evaluation

This window is where the evaluation of the music festival occurs; all stakeholders are

involved and will be corresponded with during this stage. The focus, however, will be

on the locals, visitors, and volunteers. Customer retention is a crucial interest of the

host at this stage, and this window seeks to tackle that alongside improving next

year’s sustainability. Interventions placed in this window will determine which

stakeholders will continue affiliation in the next year of the music festival, thus

directly determining longevity. Further, interventions should focus on leveraging the

momentum of the festival itself and focus on the restoration of the local environment

per the social pillar of sustainability. Festivals are often considered a temporary one-

day affair due to the fact there is no engagement or connection sustained once the

event is finished. Instead, successful evaluation and post-festival engagement allow

Problem for Visitors

Problem for Local

Community

Problem for all

Environmental

Environmental

conditions

Infrastructure, waste, resource

strain

Travel emissions,

energy use, water

use

Social

Drug misuse, spiking,

assault, crowd crushes,

accessibility,

dehydration

Noise, overcrowding, disorderly

behaviour, poor treatment of

employees/volunteers, lack of

access to space

lack of engagement

‘Responsibility

holiday’ behaviour

(Brennan et al.,

2019)

Economic

Ticket cost

Resource depreciation

13

attendees to consolidate the festival experience, whether it be sustainable learning

or socially enriching experiences (Brown et al., 2019). Designing interventions in the

evaluation stage may help overcome the unsustainability emerging from regard

festivals as a ‘one-day affair’ (Brennan et al., 2019).

3. Solutions

3.1 Theoretical backgrounds

3.1.1 Gamification and Self-Determination Theory

Gamification (Pelling, 2012) is growing increasingly prevalent to incentivise user

engagement through badges such as “top contributor” and rewards, both of which

are being employed in the proposed interventions (Easley & Ghosh, 2016). Reward-

based gamification has been useful in achieving short-term goals in environments

where participants have no personal connections or intrinsic motivations, but it does

not sustain long-term change; for this, intrinsic motivation is essential (Nicholson,

2015). Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2004) explains that intrinsic

motivation is associated with mastery, autonomy, and relatedness. Accordingly,

whilst the level two interventions of gamifying litter collection in exchange for rewards

elicit engagement, it is the level three interventions which will foster intrinsic

motivation for long-term change. The sustainability app aims to direct attendees on a

map on a pathway of their choosing (autonomy), where they will encounter

workshops teaching skills in gardening and water conservation (mastery), all of which

will be done with other people, whether old friends or new (relatedness) (Nicholson,

2014).

A successful implementation of this proposed intervention was at Mountain Music

Festival in West Virginia, where they hosted multiple workshops alongside the main

stage music. The workshops range from learning about plants native to the venue

and how to grow/ care for them at home, discovering plant remedies for common

festival wounds such as blisters and bug bites, Yoga class, painting rocks to take

home or leave as homage in festival site (Mountain Music Festival, 2024).

14

3.1.2 Integrating Digital Channels into the festival experience

Mobile applications (apps) can be effective in augmenting the on-site experiences of

multiple stakeholders. For attendees, it allows for the curation of convenient and

personalised information and provides avenues for gathering data insights for hosts.

Official festival apps have been widely used by numerous festivals in the UK and

globally (Glastonbury, Reading/Leeds, Parklife, etc) (see Figure 3). However,

developing and maintenance of these apps can be expensive, and hosts may have

to rely on sponsors for financial support. Additionally, issues of longevity persist as

festival apps have a shorter life span compared to others on the market. Thus,

interventions will explore methods of extending utility and engagement beyond the

festival period.

Figure 3. App screens from Glastonbury, Parklife and Wireless Festival

3.2 Solutions Overview

Solutions are stratified according to feasibility, in accordance with the trifecta of

innovation, with level 1 being high feasibility and level 2 being low (Orton, 2023).

Theories, particularly installation theory (Lahlou, 2017), have been utilised to inform

and facilitate the development of interventions.

Intervention

point

Key

Stakeholders

Solution

(Higher/Lower Feasible)

Rational/Theory/Concept

Window1

Host, Authorities,

Locals

“Proudlylocal”

communication

Self-determination theory

15

Table 5. Solutions overview

3.3 Breakdown

3.3.1 Window 1

Higher Feasibility: “ProudlyLocal” communication

Boosting local community spirit can be achieved through “Proudlylocal” branding of

the local community’s support. Suseno & Hidayat (2021) found positive effects of

local pride on the consumption of locally produced sneakers; this can be replicated

and applied to music festivals. For instance, this could be achieved by a

#proudlylocal campaign on social media, raising awareness of the local community’s

contribution and connection to the festival. Local businesses and suppliers can use

“proudly local” as a communication and marketing tool during the pre-festival period;

this can be through wearing #Proudlylocal badges and placing banners/labels at their

shopfronts. This intervention aims to engage multiple stakeholders, strengthen

Building Long-term

stakeholder partnerships

through commitment

Window2

Visitors

Sustainability

communication

Pre-festival social

platform

Window3

All stakeholders

Wayfinding system &

signage at the point of

action

Green currency

exchange

Gamification, Omni channel

customer experience

Themed routes and

programmes

“Festivity”: Integrated

Digital Journey

Window4

Visitors,

Volunteers,

Locals

Follow up

communication

Festival recap

Gamification

Social identity theory

Reward and re-

engagement

Restoration projects

16

community pride and boost both social and economic sustainability pillars. This

intervention aligns with self-determination theory, specifically relatedness. Humans

are inherently social beings who yearn for connection; fostering community spirit and

extending it beyond the festival period can have a crucial impact on its sustainability

(Nicholson, 2014). This can be achieved through a “brand story”, where a brand is

presented in a storytelling format (Woodside, 2010). This is supported by Cronon

(2013), who emphasises the significance of storytelling in the human experience

occurring at various levels of society. It should be noted that in the case below, the

storytelling aspect is more abstract, with some background given for visitors and

locals to construct their own story from.

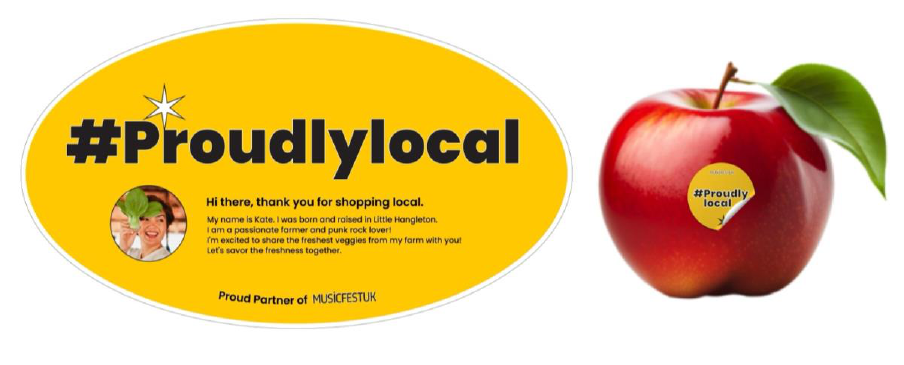

Design 1. #Produlylocal Stickers

Design 1 illustrates a mock design for a sticker distributed in the fictional community

of “Little Hangleton” created for this paper. The intention is for local businesses to

hand out #proudlylocal stickers alongside their goods with a short story about who is

behind it. An existing example of a similar initiative involves a multi-purpose venue in

Ballina/Killaloe, Ireland, where the area is repurposed as a market every Sunday.

Stalls include local farmers selling produce or craftspeople selling artisanry

creations. When a product is purchased, the customer receives a sticker stating, “I

love Ballina/Killaloe” as a token of gratitude, which doubles as an advertisement for

the local community (Lough Derg, 2014).

Additionally, it is crucial to invite the local community to the festival decision-making

process to warrant support and engagement from early on. We tackle this through a

local committee. This allows for open discussion with who is best informed about the

17

festival’s negative impact (noise pollution, litter, and resource constraints) and, thus,

how to mitigate them (Yolal et al., 2016). Further, locals should be consulted to

ensure that they get the most positive impact out of the festival – for example, by

discussing which local businesses to partner with.

Lower feasibility: Building permanency through infrastructures and legislation

This approach involves repurposing and reusing festival materials/resources to

benefit local communities. Viola (2022) outlined the importance of reusing materials

to mark community engagement and its benefit to stakeholders. This intervention,

therefore, proposes that long-term festival resources such as permanent toilets,

sewage systems, infrastructure or energy generators can be reused for future

festivals and events. This is a particular asset to the local community’s resources

and has been found to boost well-being and resilience (McCrea et al., 2015).

Although the limitation surrounding government mediation and financial support this

intervention demands is acknowledged, the long-term benefit of permanent and

reusable infrastructures benefits multiple stakeholders and consumes fewer

resources in the long run.

Permanent infrastructures can also build long-term partnerships between

stakeholders. For example, the host and local council may enter a ten-year long-term

contract for a festival site. This provides a broader economic incentive for the host to

invest in long-term resources. However, it is worth mentioning that short-term

contracts are often preferable for flexibility (Macho-Stadler et al., 2014).

Figure 4. Olympic Park, Seoul (Permanent venue from Olympic Legacy 1988)

18

3.3.2 Window 2

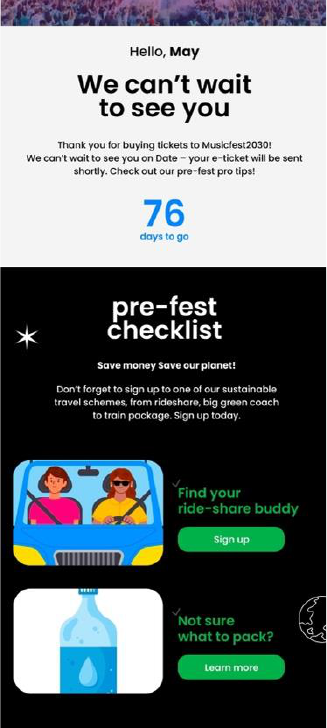

Higher feasibility: Sustainability communication

Sustainability communication can empower participants with the awareness and

tools to make sustainable decisions. This intervention includes targeting the

embodied cognition layer of the installation (Lahlou, 2017) by instilling attendees with

the knowledge required to be sustainable at festivals. Sustainability can be

communicated via existing social media and E-mail platforms in text or multi-media

format. Practical and informative tips can be circulated through email newsletters.

For example, taking your tent home with you, using correct bins, bringing your own

water bottles, consideration of travel or reducing plastic use (Shambala, 2018).

Social sustainability can also be promoted in this way; however, it goes without

saying that most socially unsustainable behaviours, such as spiking or harassment,

are not tolerated. Thus, an alternative approach could focus on perpetrators, i.e.

“don’t be a d*ck” or “treat people with respect” posters. A more engaging approach

includes the involvement of artists or celebrities to promote sustainable behaviours

(Perlman et al., 2013). Artists such as Coldplay are already attempting carbon-

negative tours and promoting them on social media (Bennett, 2023). This strategy

targets the social layer of the installation through the influence of somebody in a

position of admiration.

Lahlou (2017) suggests interventions are most effective at the point of action; thus,

targeting travel choices at the point of action, i.e. buying the ticket, would be most

effective. Another proposed intervention, therefore, is a “Rideshare sign-up” scheme

at the point of ticket purchase, which would promote experiential connection with

other visitors as well as cost savings as motives to sign up (Davidson et al., 2018).

Sign-up can also be available for the use of a ‘Big Green Coach’, endorsed by

Reading Festival, or rail tickets. This can help reduce visitor travel emissions, which

are generally the largest contributors to music festival emissions (Bottrill et al., 2010).

These interventions facilitate engagement with the festival during the stagnant period

between ticket purchase and festival, encouraging pre-planning for festivals and

instilling visitors with sustainable behaviours, promoting a sustainable festival

experience.

19

Design 2. Newsletter

There are, however, some limitations to these interventions. Social media posts

promoting festival sustainability could easily backfire by choosing artists who do not

‘walk the walk’ and act sustainably themselves. i.e. backlash against Taylor Swift

given her large carbon footprint, risking sending the wrong message (Voss et al.,

2003; Lönngren & van Poeck, 2021). Moreover, it is uncertain how effective these

messages will be as they do not fundamentally alter people’s values or goals, which

is necessary for effective systemic change within the systems thinking approach

(Abson et al., 2017). People need to be interested in sustainability for them to listen,

as it is likely that people may look to take a ‘responsibility holiday’ instead (Brennan

et al., 2019). Furthermore, people may forget advice that is only transmitted on social

media and e-mail due to the short interaction time.

20

Lower feasibility: Pre-festival Social platforms

Using activity theory (Lahlou, 2017), we identified a shared motive for connection

between visitors, which is currently overlooked within the stagnation period between

ticket purchase and festival (refer to figure 2). Therefore, the intervention includes an

online visitor connection where visitors are directed to download a festival app after

ticket purchase. Once downloaded, visitors are asked to select a few acts they are

excited to see performing and some stalls and sustainability schemes they are

especially excited about. The app then links like-minded visitors together for

discussion and networking.

Additionally, there are in-person visitor connection opportunities, which direct app

visitors to pre-festival meetups. Here, people can meet friends they have made

online or new festivalgoers. These events can be sponsored to help manage costs

and build sponsor involvement. Furthermore, these events can be paid to help fund

local artists and support the community. The social layer of installation theory is

utilised here, as sustainability is promoted through engagement with sustainably

minded individuals, establishing a social norm. By integrating paid events, this

intervention not only enhances the customer experience but also supports local

talent and sustainability initiatives.

This has a twofold effect. Firstly, it is predicted to help stimulate long-term well-being

by spreading festival values and socialisation factors across a longer timeframe (Tan

et al., 2020; Crompton & McKay, 1997). Secondly, engagement with other festival

goers can help promote sustainability either through discussion with like-minded

people or getting inspiration from others (i.e. how they are preparing for a

sustainable festival and what stalls they want to visit) (Manning, 2009; Lahlou, 2017).

However, there are some limitations, such as uncertainty of the extent to which

visitors are willing to pre-meet with others; there may well be only a small number

who wish to meet. Furthermore, organising pre-festival meetups and in-app social

functionality may be straining host finances and resources when festival preparation

is underway. To mitigate this, sponsors could be used to fund meetups in exchange

for brand exposure.

21

3.3.3 Window 3 – Operation and Engagement

Higher Feasibility A: Wayfinding system and signage at the point of action

Signs prompt people to access the relevant action representation that they already

possess and activate it at the right time, in the right context (Meis, J., & Kashima, Y,

2017). In this intervention, social-environmental signs are aimed to be displayed at

the point of action to signal participants of desired behaviours. Eco-labels and

signages may be strategically placed in high-traffic areas using visual cues and

icons.

Design 3. Eco-Station signage & Safe space posters

Also, targeted signs and posters that list actions against harassment can be placed

in the performer space. Safe space posters can be used to mark areas throughout

the festival venue to promote safe interactions, respect, and a safe festival culture. In

the neighbourhood, “Psst, thank you, visitors, for being quietly awesome!” using

illustrations of homes and people to remind personal relationships and kindness

rather than laws/regulations. Another intervention would include the notion of

“Greenway” wayfinding lanes to navigate participants to nearby recycling points,

water refill stations, and green venues/events (see Design 4). Through clearly

labelled waste sorting stations and displays, along with volunteer guides to facilitate

proper waste disposal, Greenway can encourage sustainable participation.

22

Design 4. Greenway

This would increase the chances of behaviour change by alerting people at the point

of action. Wayfinding systems are easy, cost-efficient methods of providing

information and gently guiding people to eco-friendly options. Furthermore, it also

enhances the festival experience of stakeholders as it provides attendees with a

clear direction and guide for decision-making, thus potentially reducing social

conflicts. The challenge posed by this intervention is that too much signage can be

confusing and risks cognitive overload- visitors may feel overwhelmed by the

responsibility of strictly being a sustainable citizen when initially they are seeking fun

(Fox et al., 2007).

Higher Feasibility B: Green currency exchange

This intervention is inspired by the Coachella Recycling store: 10-For-1-Water

(Coachella, 2024). This initiative encourages visitors to return bags of recyclables in

exchange for goods. For example, a small bag can earn fresh water, while a large

bag can be traded for festival merchandise and other items. This intervention

gamifies pro-sustainable behaviour through incentives (Easley & Ghosh, 2016).

Further on, badges or recognition boards can be introduced to label individuals as

"Green Ambassadors," reinforcing positive behaviour. Additionally, real-time displays

of green currency exchange activities and collections can be introduced to

encourage participation.

23

Design 5. Green Currency Exchange

Design 6. Green Ambassadors Badge

Lower Feasibility: Sustainability-themed programmes and connecting routes

This intervention is focused on the design and integration of sustainability

programmes into multiple themed routes, with touchpoints for different attendees to

meet, learn, and socialise. These themed routes inspire ideas for activities and

spaces to explore (see Design 4). The path will include local markets, workshops

(local arts, history, skills), NGO booths, new skills workshop (vegan cooking, grow

your vegetables), scheme sign-ups (sharing economy, time banks), space for

socialisation, and artists meetups (see design 4). All these ideas resonate with

degrowth literature, in encouraging the shift towards a communal sufficiency-based

24

economy (Cosme et al., 2017). In this sense, this intervention can embody visitors

with the competencies required for long-run sustainable living within degrowth

paradigms (Lahlou, 2017). Finally, a “People’s Day” is also suggested. This day

makes socialisation, learning, and the local community central to the experience, as

opposed to the artist line-up. This day would be especially inclusive of the local

community, who are invited to attend for reasons of empowerment and socialisation

through various festival-themed activities.

Festivity App

The design illustrates the integrated digital journey through an app we have named

“Festivity.” This intervention takes the form of a digital app featuring the

abovementioned routes and programmes with a focus on sustainability. It aims to

enhance the user experience and increase engagement and motivation through fun

on-offline interaction. Gamification strategies that align with stakeholder goals and

user interests are employed, such as a points system, badges, and quests. Festivity

could be a single app utilised by multiple festivals to share costs.

Design 7. Festivity App-Themed Routes

3.3.4 Window 4 - Evaluation

The interventions placed during this post-festival evaluation period will predominantly

focus on evaluation and retention to ensure longevity and, thus, the future of

sustainable music festivals. To approach this from an economic standpoint, retention

is more cost effective than acquisition, and although this notion is commonly applied

25

to customers only, it is applicable to all stakeholders previously identified (Kumar,

2022.)

Higher feasibility A: Follow-up communication

Personalised thank-you notes are a low-hanging fruit in the context of showing

gratitude to stakeholders and evaluating performance. For host organisations,

volunteers, the local community, artists, and sponsors in particular, post-even

communication can incorporate quantitative evidence of a profitable relationship

through a combination of personalised thank-you note, post-event reports, feedback

requests and debrief meetings. In-depth feedback can be sought from visitors, staff,

locals, and artists to improve the festival experience and sustainability next time.

Design 8. Follow-up Newsletter

Higher feasibility B: Recap

For stakeholders with experiential motives (visitors, local community members,

volunteers), their festival experience can be extended beyond the event date by

redelivering a curated presentation of their memories. This can be in the form of

26

hashtags and social media prompts to encourage engagement with content

purposefully timed with the early-bird release of tickets for the upcoming year. We

aim to leverage the nostalgia created by this engagement as motivation for

purchasing tickets (Schwarz, 2009).

Another intervention is an app feature which acts as a disposable camera minus the

waste. As you are unable to scrutinise the photo in the moment, it allows attendees

to be detached from technology and social media to fully immerse in the festival

experience (McKay, 2024). Advertently, this function fulfils the present study’s

rationale of strengthening the social pillar, as detachment from social media presents

the opportunity to foster and strengthen social connections organically (Herren

Wellness, 2021.)The time it takes for photos to finish ‘developing will be timed with

the early-bird release of tickets to encourage sales by leveraging nostalgia and, thus,

customer retention. This reflection could also further reinforce sustainable

information consumed, or activities participated in, encouraging long-term

sustainable behaviour outside of the festival (Brown et al., 2014). Photos taken on

the app will garner points, which will be explored below.

Design 9. SNS Recap Prompt

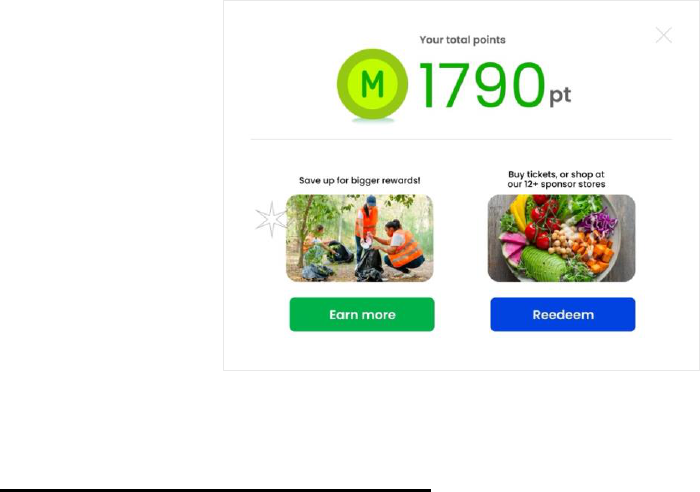

Lower feasibility A: Festival rewards and re-engagement events

As illustrated by Easley & Ghosh (2016), gamification can be used to incentivise user

engagement. This reward system has been successfully implemented by

27

McDonald’s, where the MyMcDonald’s app exchanges 100 points for every £1 spent,

which can either be donated to charity or spent on food items. Our intervention

adopts this to incentivise pro-sustainable behaviour to acquire points instead of

spending (see design 6). Building on this, excess points can be transferred onto the

next visit; this requires participants to return the following year to claim rewards,

ensuring customer retention. MyMcDonalds is a strong example of how effective

such schemes can be; 60% of sales are attributed to this digital channel, and it is

predicted to soon become the world’s largest loyalty programme (Valentine, 2022).

Design 10. Point redemption (Website)

Lower feasibility B: Project Restoration

The destructive contribution of music festivals to environmental and wildlife

degradation is by now alarmingly evident (Brennan & Collinson-Scott, 2019).

Accordingly, our proposed intervention suggests large-scale environment restoration

projects such as revegetation, habit enhancement and remediation, with community

engagement as a focal point (Vaughn et al., 2010).) Environmental Migration Portal

(2024) emphasises the importance of the community “to support ecosystem

restoration”. Integrating the local community in the restoration projects motivates

individuals in the same group (community) to work towards a common goal, which,

as informed by the Social Identity Theory, strengthens group cohesion and social

bonds (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). The restoration campaigns can be financed through a

partnership with Restore Our Planet (2024), which is a charity that invests in the

protection and restoration of natural habitats in the UK. Another suggestion for

financing is through corporate social responsibility from the host/sponsors or

28

subsidies from the government; both suggestions come with limitations, which will be

explored next.

Repercussions of anthropogenic climate change, which music festivals undoubtedly

contribute towards, are being experienced now and require immediate action (United

Nations, 2024). The suggested low-feasibility interventions, although valuable, are

costly and may require considerable time to be trialled, funded and launched.

Furthermore, the displacement of accountability from the government and

corporations to individuals, and the pursuit of capitalist profit, hinders access to the

charitable donations and subsidiaries required to finance our proposed interventions.

4. Conclusion

The lack of sustainability surrounding music festivals during this climate crisis is

severe and must be addressed. This redesign comes at a pressing time to shed light

on key areas which demanded reconstruction, with interventions formulated on the

framework of a thorough stakeholder analysis. Windows of opportunity have been

identified using Installation theory (Lahlou, 2017) where its’ respective interventions

are placed. Power differences amongst stakeholders have been assessed using the

power-interest stakeholder matrix (Mendelow,1991) to target solutions more

concretely. The triple bottom line, discussed as pillars, was employed to address all

aspects of the music festival, aiming to increase longevity. This paper highlights that

support from the local community is crucial in fostering a sustainable music festival,

albeit this is scarcely addressed by existing literature. The most tangible solutions

are present in Window 3 as it is concerned with the festival itself and, thus, holds the

greatest prospect of real-world application.

4.1 Limitations

Due to the scope of this paper, it was not successful in addressing all issues,

stakeholder motives, or interventions thought possible. Thus, we were unable to

develop each solution enough for real-world implementation, giving rise to feasibility

levels. This redesign intended to target the broad, unsustainable aspects of music

festivals, and not one. Future research may be wise to narrow focus and consider

specific factors unique to an area or case study. It has been difficult to find data and

29

literature as festivals are yet to adopt sustainable measures, which again

emphasises the need for future research in this area. This contributed to a general

level of uncertainty regarding the accuracy of our stakeholder analysis; future

research may wish to consult individuals in the industry to confirm or modify our

findings. Finally, our interventions have yet to be tested. Interventions in practice

change complex webs of interrelated activities and motives, and unintended and

unforeseen consequences are possible (Hayek, 1978). Lewin (1946) argues that to

understand a system, you need to try and change it, and without testing, this study’s

present interventions lack certainty in effectiveness. Considering this, it is again

necessary to emphasise the need for sustainable approaches to music festivals to

be implemented immediately.

30

31

5. References

Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., . . . Lang, D. J. (2017).

Alhaddi, H. (2015). Triple Bottom Line and Sustainability: A Literature Review. Business and

Management Studies, 1. https://doi.org/10.11114/bms.v1i2.752

Ashdown, H. (n.d.). The Sustainable Future of Music Festivals.

Aji Suseno, B., & Hidayat, A. (2021b). Local Pride Movement As A Local Sneaker Branding Strategy.

Journal of Indonesian Applied Economics, 9(2), 48–59.

https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jiae.009.02.6

Bennett, P. (2023, February 3). 10 musicians that are embracing sustainability. EcoWatch.

https://www.ecowatch.com/musicians-embracing-sustainability.html

Bottrill, C., Liverman, D., & Boykoff, M. (2010). Carbon soundings: greenhouse gas emissions of the

UK music industry. Environmental Research Letters, 5(1), 014019.

Brennan, M., Scott, J. C., Connelly, A., & Lawrence, G. (2019). Do music festival communities

address environmental sustainability and how? A Scottish case study. Popular Music, 38(2),

252–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261143019000035

Brown, P. C., Roediger III, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful

learning. Harvard University Press.

Cabrera, D., Colosi, L., & Lobdell, C. (2008). Systems thinking. Evaluation and Program Planning,

31(3), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.12.001

Cain, S. (n.d.). The Eras Tour film has already grossed more than $100m. The Taylor Swift economy

is unstoppable. Retrieved 17 February 2024, from

https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20231011-the-eras-tour-film-has-already-grossed-more-

than-100m-the-taylor-swift-economy-is-unstoppable

Clarke, A., & Jepson, A. (2011). Power and hegemony within a community festival. International

Journal of Event and Festival Management, 2(1), 7-19.

Coachella. (2024). Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival. Www.coachella.com.

https://www.coachella.com/recycling-store

Cosme, I., Santos, R., & O’Neill, D. W. (2017). Assessing the degrowth discourse: A review and

analysis of academic degrowth policy proposals. Journal of cleaner production, 149, 321-334.

Crompton, J. L., & McKay, S. L. (1997). Motives of visitors attending festival events. Annals of tourism

research, 24(2), 425-439.

Cronon, W. (2013). Storytelling. The American Historical Review, 118(1), 1–19.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/118.1.1

Davidson, A., Habibi, M. R., & Laroche, M. (2018). Materialism and the sharing economy: A cross-

cultural study of American and Indian consumers. Journal of Business Research, 82, 364–

372.

Deci, E. and Ryan, R. (2004). Handbook of Self-Determination Research. Rochester, NY: University

of Rochester Press.

Deliso, M., & Hutchinson, B. (n.d.). Authorities release name of man who died at Burning Man,

investigation into death ongoing. ABC News. Retrieved 1 March 2024, from

https://abcnews.go.com/US/burning-man-rains-mud/story?id=102886032

32

Donald Getz & Tazim B. Jamal. (1994). The environment‐community symbiosis: A case for

collaborative tourism planning, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2:3, 152-

173, DOI: 10.1080/09669589409510692

Easley, D., & Ghosh, A. (2016). Incentives, gamification, and game theory: an economic approach to

badge design. ACM Transactions on Economics and Computation (TEAC), 4(3), 1-26.

Environmental Migration Portal. (n.d.). It takes a community to support ecosystem restoration and... |

Environmental Migration Portal. Environmental Migration Portal. Retrieved 27 February 2024,

from https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/blogs/it-takes-community-support-ecosystem-

restoration-and-overcome-environmental-challenges-facing-world-today-european-action-

migrants-and-nature

Eventbrite. Want to know how to start a festival? follow this 10-step guide. Eventbrite Blog. (2023,

July 21). https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/blog/how-to-start-a-festival/

Foster, M. (n.d.). Burning Man in a burning world. The Chronicle. Retrieved 1 March 2024, from

https://www.dukechronicle.com/article/2023/09/091223-foster-burning-man-environment

Fox, J. R., Park, B., & Lang, A. (2007). When available resources become negative resources: The

effects of cognitive overload on memory sensitivity and criterion bias. Communication

Research, 34(3), 277-296.

Frith, S. (1996) Performing rites: on the value of popular music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Glastonbury Festival. Glastonbury Festival - 21st-25th June, 2023. (2023).

https://www.glastonburyfestivals.co.uk/information/tickets/

Grewatsch, S., Kennedy, S., & Tima) Bansal, P. (2021). Tackling wicked problems in strategic

management with systems thinking. Strategic Organization, 21(3), 147612702110386.

https://doi.org/10.1177/14761270211038635

Hayek, F. A. (1978). Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 2. University of Chicago Press.

Herren Wellness. (n.d.). 8 Benefits of Being Present in a Social Media World. Retrieved 27 February

2024, from https://herrenwellness.com/8-benefits-of-being-present-in-a-social-media-world/

International Institute for Sustainable Development. (n.d.). International Institute for Sustainable

Development. International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved 1 March 2024,

from https://www.iisd.org/

Just Plane Wrong: Celebs with the Worst Private Jet Co2 Emissions | Insights. (n.d.). Yard. Retrieved

17 February 2024, from https://weareyard.com/insights/worst-celebrity-private-jet-co2-

emission-offenders

Karlsen, S. & Brändström, S. (2008) 'Exploring the music festival as a music educational project',

International Journal of Music Education, 26 (4): 363-373.

Kumar, S. (n.d.). Council Post: Customer Retention Versus Customer Acquisition. Forbes. Retrieved

27 February 2024, from

https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2022/12/12/customer-retention-versus-

customer-acquisition/

Lahlou, S. (2017). Installation theory: The societal construction and regulation of behaviour.

Cambridge University Press.

Lewin, K. (1946). ‘Action research and minority problems’. In Lewin, G. W. (Ed.), Resolving Social

Conflict. London: Harper & Row.

Lough Derg. (2014, June 24). Killaloe Farmers Market. Discover Lough Derg.

https://discoverloughderg.ie/killaloe-farmers-

market/#:~:text=The%20bustling%20market%20is%20held

33

Lönngren, J., & van Poeck, K. (2021). Wicked problems: A mapping review of the literature.

International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 28(6), 481–502.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2020.1859415

Mair, J., & Laing, J. (2012). The greening of music festivals: Motivations, barriers and outcomes.

Applying the Mair and Jago model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism - J SUSTAIN TOUR, 20,

683–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.636819

Macho-Stadler, I., Pérez-Castrillo, D., & Porteiro, N. (2014b). Coexistence of long-term and short-term

contracts. Games and Economic Behavior, 86, 145–164.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2014.03.013

Manning, C. (2009). The psychology of sustainable behavior. Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, 5-

8.

Martinez-Vazquez, J., & Bird, R. (2014). Sustainable development requires a good tax system (pp. 1–

23). https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783474332.00006

Matheson, C.M. (2005) 'Festivity and sociability: a study of a Celtic music festival', Tourism Culture &

Communication, 5: 149-163.

McCrea, R., Walton, A., & Leonard, R. (2014). A conceptual framework for investigating community

wellbeing and resilience. Rural society, 23(3), 270-282.

McKay, P. (2024, February 13). Why Disposable Cameras Are Making a Comeback. Analogue

Wonderland. https://analoguewonderland.co.uk/blogs/film-photography-blog/why-disposable-

cameras-are-making-a-comeback

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. chelsea green publishing.

Meis, J., & Kashima, Y. (2017). Signage as a tool for behavioral change: Direct and indirect routes to

understanding the meaning of a sign. PLOS ONE, 12(8), e0182975.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182975

Mendelow, A. L. (1991) ‘Environmental Scanning: The Impact of the Stakeholder Concept’.

Proceedings From the Second International Conference on Information Systems 407-418.

Cambridge, MA.

Mountain Music Festival 2024. (n.d.). Mountain Music Festival. Retrieved 23 February 2024, from

https://mountainmusicfestwv.com/

Nicholson, S. (2015). A RECIPE for Meaningful Gamification. In T. Reiners & L. C. Wood (Eds.),

Gamification in Education and Business (pp. 1–20). Springer International Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_1

Pelling, N., 2011. The (short) prehistory of “gamification”…. Funding Startups (& other prehistory-

of-gamification/ [Accessed February 24, 2024].

Perlman, H., Usdin, S., & Button, J. (2013). Using popular culture for social change: Soul City videos

and a mobile clip for adolescents in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters, 21(41), 31-34.

Prakash, A., & Dolsak, N. (n.d.). Taylor Swift And Climate Change: Is The Youth ‘Shaking Off’ Or

Embracing Carbon-Intensive Lifestyles? Forbes. Retrieved 17 February 2024, from

https://www.forbes.com/sites/prakashdolsak/2023/08/02/taylor-swift-and-climate-change-is-

the-youth-shaking-off-or-embracing-carbon-intensive-lifestyles/

Restore Our Planet. (2024). Restore Our Planet. https://restoreourplanet.org/

Richardson, N. (2018). Entrepreneurial insights into sustainable marketing: A case study of U.K.

music festivals. Strategic Change, 27(6), 559–570. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2239

Safe, F. (2023, May 8). Sustainability. Festival Safe.

https://www.festivalsafe.com/information/sustainability

34

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and

task design. Administrative science quarterly, 224-253.

Schwarz O. (2009). Good young nostalgia: Camera phones and technologies of self among Israeli

youths. Journal of Consumer Culture, 9(3), 348–

376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509342045

Shambala. Drastic on Plastic. (2018) https://www.shambalafestival.org/wp-content/uploads/A4-

Festival-Goer-Guide-2018.pdf

Smith, A. (2012). Events and urban regeneration: The strategic use of events to revitalise cities.

Routledge.

Strout, A. (2019, June 23). Fans Want More Sustainable Festivals, Major Study From Ticketmaster

Finds. Live Nation Entertainment. https://www.livenationentertainment.com/2019/06/fans-

want-more-sustainable-festivals-major-study-from-ticketmaster-finds/

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In W. G. Austin & S.

Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of inter-group relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey, CA:

Brooks/Cole.

Tan, K. L., Sim, A. K., Chai, D., & Beck, L. (2020). Participant well-being and local festivals: the case

of the Miri country music festival, Malaysia. International Journal of Event and Festival

Management, 11(4), 433-451.

Thrane, C. Jazz festival visitors and their expenditures: Linking spending patterns to musical interest.

Journal of Travel Research, 40, 281–286. (2002)

Tiew, Fidella & Holmes, Kirsten & de Bussy, Nigel. (2015). Tourism Events and the Nature of

Stakeholder Power. Event Management. 19. 525-541.

10.3727/152599515X14465748512768.

United Nations. (n.d.). Climate Change. United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 27

February 2024, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/

Valentine, M. (2022, January 27). McDonald’s new loyalty scheme has ‘exceeded expectations’ as

digital sales jump. Marketing Week. https://www.marketingweek.com/mcdonalds-loyalty-

scheme-digital-sales/

Vaughn, K. J., Porensky, L. M., Wilkerson, M. L., Balachowski, J., Peffer, E., Riginos, C. & Young, T.

P. (2010) Restoration Ecology. Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):66

Viola, S. (2022). Built Heritage Repurposing and Communities Engagement: Symbiosis, Enabling

Processes, Key Challenges. Sustainability, 14(4), 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042320

Voss, K.E., Spangenberg, E.R., & Grohmann, B., Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of

consumer attitude: A generally applicable scale. Journal of Marketing Research, 40, 310–320.

(2003)

Walker, T. (2022, August 1). Reading Festival 2022 capacity and other facts. Berkshire Live.

https://www.getreading.co.uk/whats-on/whats-on-news/reading-festival-2022-capacity--

24641658

Wang, P., Liu, Q. and Qi, Y. (2014) Factors Influencing Sustainable Consumption Behaviors: A

Survey of the Rural Residents in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 63, 152-

165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.05.007

Woodside, A. (2010). Brand-Consumer Storytelling Theory and Research: Introduction to a

Psychology & Marketing Special Issue. Psychology and Marketing, 27, 531–540.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20342

35

Yolal, M., Özdemir, C., & Batmaz, B. (2019, January). Multidimensional scaling of spectators’

motivations to attend a film festival. In Journal of Convention & Event Tourism (Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 64-

83). Routledge.

Ziady, H. (2024, February 15). UK falls into recession, with worst GDP performance in 2023 in years |

CNN Business. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2024/02/15/economy/britain-falls-into-

recession/index.html

6. Appendix

Appendix 1. Pain points analysis per the triple bottom line.

Appendix 2. Problem analysis of installations - Window 1

Actor

Task

Motivation

Contribution

Rewards

Installation

Physical

Installation

Competence

Installation

Social

Host

Event

plannin

g &

organisi

ng:

Liaise

with

other

stakeho

lder

Stand out

in

competitio

n, Profit,

Earn

support

Festival

planning &

execution

knowledge

Support &

backing

Online/Wirel

ess

communicat

ion (email,

phone, fax),

Offline

planning

committee

meetings

Know logistics

about the event

(budget, timeline,

plans), Can

organise meetings

between planning

stakeholders, Can

communicate

verbally on-offline

Responsibility

/social

expectation

as a host,

Inclusion/safe

ty measures

and criteria,

previous

years'

feedback

Autho

rity

Meeting

with

host &

local to

discuss

logistics

of

festival

Public

Safety,

Political

communic

ation,

Cultural &

Econ

developme

nt

Moral

assistance /

Financial

contribution

Exhibition of

political

authority,

positive

public

acknowledg

ement

Online/Wirel

ess

communicat

ion (email,

phone, fax),

Offline

planning

committee

meetings

Know economic-

environment-

social goals,

Know how to

regulate/support,

Know where to

get resources,

Can communicate

using current

platforms (email,

mail, community

meetings)

Social

perception of

the

government,

Social

expectation of

government

participation

and

responsibility,

Social

Inclusion

36

Local

s

Learn

about

Event

detail,

Consult

& sort

out role

and

contribu

tion

Generate

revenue,

Sense of

community

, Cultural

celebration

Local

knowledge,

Support(fina

ncial,

service)

Social,

Economic,

Environment

al benefits

Online/Wirel

ess

communicat

ion (email,

phone, fax),

Offline

planning

committee

meetings,

Local

billboards

Knowledge about

local resources

and people, Can

communicate

needs and

contribution to

other

stakeholders, Can

examine loss and

benefits, Can

communicate

internally using

platforms

(billboard,

messenger), Have

role specific

knowledge(accom

modation, service

etc)

Social norms

& Local rules,

Power

dynamics,

Laws and

government

regulations

Appendix 3. Problem analysis of installations - Window 2

Acto

r

Task

Motivation

Physical

Competence

Social

Host

Ticket sale

& Promotion

-

Organising

with

different sta

keholders

Connect with all

other stakeholde

rs -> for

festival branding

and smooth oper

ation

E-mail platform, social

media use, navigating

fanbase,

ticket purchasing

platforms

including external

providers

(ticket master, live

nation)

Ticket

giveaways, communi

cating with

other stakeholders,

sending reminders to

previous attendees,

incentivize

social sharing

Coordination of

everyone involved,

organizing information

forums, FAQs,

Loc

als

Promotion

-

Setup

-

Community

Engagemen

t

Self actualisation

, wellbeing, utility

, exercise, ideolo

gy, altruism

Social media,

community, noticeboar

ds, email, other locals,

posters

-

Tables, chairs,

stage equipment,

social media platform,

messaging platform

-

Community,

workshops, community

centres, apps, social

media,

shops, communal

areas

Marketing and

persuasion skills,

economic sensibility

-

Ability to set up,

technical knowledge,

tech

savviness, views

towards volunteering

-

Ability to engage in

community activites,

will/need to

engage in activities,

communication skills,

empathy/sympathy

Social norms

around persuasion

and privacy

-

volunteering /

helping norms,

festival regulation

-

social norms

around helping,

local government rules

and reg, community

spirit

Volu

ntee

rs

Browse and

apply for

festival roles

-

Training

Connect

to other voluntee

rs, Connect

to locals

and visitors

Volunteer website,

Physical & digital ads

-

On/Offline space

for training, Booklets/P

df of the programme,

Badge-Uniform

Have role-specific

skills or knowledge

to share, Know

how to access to

volunteer portal

--

Read/listen

understand

the training, physical

ability(if needed)

Positive view(?)

towards volunteering,

Volunteer platform

system, Volunteer

group’s culture and

roles

-

Training guidelines

and plan, Festival

rules and guidelines,

Roles

and responsibilities,

Training programme

Visit

ors

Visitor

Purchases ti

cket

-

Visitor

prepares for

travel

Desire to

see artists, expe

rience events, so

cialise, strenghte

n relationships

Website, email

platform, bank card,

phone/tech, Social

Media Ads, online

shopping,

Physical ticket

package, Popup

events

-

Transportation

booking platform,

Tech savviness,

google search skills,

frugality, ability to

search for desired

items, shopping in

person, tactful use of

online queues

-

Can find and

arrange booking,

Can expect and

Host rules

and procedures,

festival rules and

regulation, ticket tout

rules /

ticketing platform rules

-

”green transportation”,

Parking, Booking

system policies

and regulations

37

Transportation(car, coa

ch, plane),

tents, accessories,

food and

drink, physical shop

plan what to pack,

Search for

the accommodation

Auth

ority

Enforcing re

gulations

& ensuring

safe operati

on on

all other sta

keholders

Boosting

local and

national econom

y

-

Adherence to re

gulations

-

Public safety

E-mail and other

platforms

for communication

with stakeholders,

laptop/devices,

Help

host organisation pro

mote ticket sales,

Regulation on re-

sell laws and

purchasing from

trusted

websites, marketing

tickets, GDPR on

customer details

Artis

ts

Announce (

PR)

-

Get

ready (rehe

arse..)

Connect

to potential/curre

nt

fans, Maybe Spo

nsors?

Social media platform,

phone/ tech, shopping

for prop, costumes and

set décor, camera, …

-

Studio, instrument,

recording technology,

transportation,

Tech

savviness, correspon

dance, adherence to

social norms

-

Can plan out

the performance

based on

event (time,

style etc),

awareness of visitor

desires,

commercial sensibilit

y, perform as expect

ed,

travel arrangements

Festival PR

Guide, Artist/Agency

branding or PR

guideline, marketing

laws, marketing trends

/ norms

-----------

Music and

performance trends,

Cultural awareness/ap

propriation

Spo

nsor

s

Announce s

ponsorship(

PR)

Connect

to new audience,

Media coverage

Social media,

Local/online newspape

r, Street ads, Product

Packaging

(if applicable),

Promotional vouchers

Know the marketing

strategy for the

target

audience group, Kn

ow festival

event details, Know

customer needs

Following the

market rules and

guidelines, Social

resistance towards ma

rketing/manipulation, S

ocial pressure to

be green

Appendix 4. Problem analysis of installations - Window 3

Actor

Task

Motivation

Physical

Competence

Social

Host

org

Smooth

execution

Profit, reputation,

corporate social

responsibility, bring

wellbeing to others,

USP

Pull factors: cost,

safety risks, rep risks,

logistics, attendance

Office/working space,

stages, music

equipment, audio

equipment, dance

floor, amenity stalls,

signs, directions,

merch, products on

sale (e.g. water

bottles), clothing

Organisation,

logistics, liaison

with various

stakeholders,

contract

negotiation,

visitor

expectations,

standard

practice for

festivals, health

and safety law,

land law, noise

pollution law,

contract law,

other law,

Locals

Set up /

staffing

-

Engage &

Experienc

e

Self actualisation, wellb

eing, utility, exercise, id

eology, altruism

Community areas,

infrastructure, stage,

dancefloor, stalls,

signs, local streets,

roads, cars, clothes

(high vis)

-

mobile phone, water

bottle, clothes,

accessories,

dancefloor, food stalls,

stage, speakers

physical ability,

festival knowledge,

specialist

knowledge,

economic

knowledge,

knowledge of

festival behaviour

from others, social

skills, food/drink

skills, following

instructions

-

letting go, phsyical

ability, how to pay,

where to go, what

to do, festival

layout/map, cultural

knowledge

visitor

expectations,

festival social

norms, volunteer

norms / practice

/ script,

government laws

and regulation,

food and drink

regulation

-

social norms,

government law,

drug law, festival

rules, festival

norms

38

Volunte

ers

Complete

training

-

Commit to

/ fulfil role

upskill, perform job

properly, rules and

regulation

-

social value, self

expression, altruism,

kindness, free ticket,

experience festival

Website, festival site,

off site / contractor

premises, email,

phone, social network,

post

-

mobile phone, clothing

(high vis), equipment

(walkie talkies), bar,

bar equipment, festival

site, stage, mixing desk

social skills, bar

skills,

resourcefulness,

general ability to

perform tasks,

physical strength,

kindness, specialist

knowledge

visitor

expectations,

festival social

norms, volunteer

norms / practice

/ script,

government laws

and regulation

Visitors

Travel to

-

Enter

-

Engage /

Interact

-

Explore

local area

-

Travel

home

socialisation, self

expression, self

actualisation /

realisation, cultural

exploration,

entertainment, see

music acts, alcohol

use, drug use, memory

making, experience,

camping, food/drink,

talks, intellectual

stimulation

-

Tourism, cultural value,

entertainment,

socialisation

Social media, Email,

Photos and videos

from the festival,

souvenirs

Can reflect and

evaluate goods and

bads, Can use

social media/email,

Know how to

connect and

communicate with

people/organisation

Role and

responsibilities

as a citizen, Any

applicable

contracts and

rules from host

organisation,

Individual/Social

ethics

Appendix 5. Problem analysis of installations - Window 4

Actor

Task

Motivation

Contribution

Rewards

Physical

Competence

Social

Host

Debrief

&

evaluate

the

event

Profit,

Customer

loyalty

and

reputation

Smooth

execution of the

festival, Foster

safe & inclusive

environment,

Bring attention to

social cause

Profit,

Customer

loyalty,

Reputation

In/external

meeting

(online,

offline),

Communicat

ion methods

(phone,

message,

email, mail),

SNS, Official

website,

Track/record

of the event

Know how to

measure

earned or

expected

values and

losses, Can

communicate

with other

stakeholders,

Know how to

communicate

with visitors

using social

platforms, Can

relect and learn

from the

mistake, Know

how to

archive(written,

video, photo)

the data

Responsibilit

y as an

event

organiser,

Inclusion/saf

ety

measures

and criteria,

Laws and

guidelines,

Expectation

and

pressure

from other

stakeholders

,

Competitors'

practice

Locals

Evaluat

e the

experien

ce &

loss and

gains

Generate

revenue,

Sense of

communit

y, Cultural

celebratio

n

Local

knowledge,

Providing

support (goods

and service)

Economic

developme

nt, Source

of income,

Togethern

ess / social

identity

empowerm

ent

In/external

meeting

(online,

offline),

Communicat

ion methods

(phone,

message,

email, mail),

SNS,

Community

billboards

Know how to

talk and gather

thoughts and

opinions, Can

calculate loss

and earns,

Know which

communication

platform to use,

Know

expectation/go

als and the

result,

Social

norms &

Local rules,

Role as a

organising

committee,

Power

dynamics,

Laws and

government

regulations,

Social

contracts

between

members or

with

outsiders

Visitors

Evaluat

e the

experien

ce

Social

motive

(connecti

on),

Novelty

seeking

Build

communities and

unique festival

culture, Brand

loyalty, promote

culture

Self-

expression

, Novel

experience

, Social

satisfaction

Social

media,

Official

website and

email,

Photos and

videos from

the festival,

Can reflect and

evaluate goods

and bads, Can

access photos

and videos of

the festivals,

Can use social

media/email

Role and

responsibiliti

es as a

citizen,

Individual/So

cial moral

standards

39

MDs/souven

iers

Volunte

er

Evaluat

e the

experien

ce

Social

value,

Identity

building,

Experienc

e

Quality festival

experience,

Education/Prom

otion, Industry

specific skills

and knowledge

Experience

, Network

& Career

developme

nt,

Financial

benefits

(tickets,

freebies)

Social

media,

Email,

Photos and

videos from

the festival,

souvenirs

Can reflect and

evaluate goods

and bads, Can

use social

media/email,