Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

David Arseneau is an assistant director and Skander Van den Heuvel an associate

director in the Federal Reserve Board’s Division of Financial Stability. Molly Mahar

is a senior associate director in the Board’s Division of Supervision and Regulation.

José Fillat is a senior economist and policy advisor in the Federal Reserve Bank

of Boston’s Research Department. Donald Morgan is a nancial research advisor

in the Federal Reserve Bank of Ne w York’s Research and Statistics Group. Emails:

david.m.arseneau@frb.gov, jose.[email protected].org, molly.e.maha[email protected]v,

don.morgan@ny.frb.org, skander.j.vandenheuve[email protected]v.

e views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reect

the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New Yor k, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston,

or the Federal Reserve System. To view the authors’ disclosure statements, visit https://

www.newyorkfed.org/research/epr/2022/epr_2022_MSLP_arseneau.html.

I

n March 2020, it became clear that the COVID-19

pandemic would cause widespread economic disruptions

that would harm many U.S. businesses and households.

Moreover, there was acute uncertainty about the duration

and ultimate severity of the economic and nancial harm.

Many businesses with the ability to draw down on their

existing credit lines did so—either to cover revenue shortfalls

or to boost cash holdings as a precautionary measure. At the

same time, banks appeared to be tightening the supply of

new credit in response to the resulting uncertainty.

ese conditions motivated the Federal Reserve and the

Department of the Treasury to create the Main Street

Lending Program (Main Street), rst announced at the end

of March 2020. As one of several credit facilities set up in

response to the pandemic, Main Street was intended in par-

ticular to help those businesses that were too small to benet

from the Federal Reserve’s corporate credit programs but too

large to qualify for the loans and grants available through the

Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). Filling that support gap

was uniquely challenging because the targeted rms depend

• The Main Street Lending

Program was created in 2020

to support credit to small and

medium-sized businesses

and nonprots harmed by the

COVID-19 pandemic, partic-

ularly those in the “missing

middle” in terms of size, which

were unsupported by other

pandemic-response programs.

• The facility marked the

Federal Reserve’s most direct

involvement in the business

loan market since the 1930s

and 1940s and operated by

buying 95 percent participa-

tions in loans from lenders

and sharing the credit risk

with them.

• Ultimately, Main Street

supported more than 2,400

borrowers and co-borrowers

across the U.S. with loans

totaling $17.5 billion, the most

of any Federal Reserve credit

purchase facility.

• This article describes the

facility’s goals and design, the

challenges and constraints it

faced, and the characteristics

of its borrowers and lenders. It

also offers lessons learned for

future policymakers and facility

designers.

OVERVIEW

T M S L

P

David Arseneau, José Fillat, Molly Mahar, Donald Morgan, and Skander

Van den Heuvel

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

primarily on bank loans (versus bonds) that are highly dierentiated (“bespoke”) and largely

untraded. Reaching that corner of credit markets required an entirely new type of credit facil-

ity built from the ground up. It was also, incidentally, the Federal Reserve’s most direct

intervention in the bank loan market since it lent directly to businesses briey in the 1930s and

1940s (Sablik 2013). Despite the challenges, Main Street wound up supporting more than 2,400

borrowers and co-borrowers across the United States with loans totaling $17.5 billion, the most

of any Federal Reserve credit purchase facility.

1

is article tells the story of Main Street so far. We rst revisit the credit conditions in

spring 2020 that motivated the decision by the Federal Reserve and the Treasury to embark on

such a program. Second, we describe how Main Street was designed to support credit supply by

purchasing loan participations from banks and other lenders and sharing credit risk with

them. ird, we analyze the reach of Main Street, including take-up, characteristics of borrow-

ers and lenders, and factors that likely limited its take-up, such as certain program features and

much weaker loan demand aer a surge in the spring. We conclude with some lessons learned

for future policy makers and facility designers. We caution that some of these lessons are pre-

liminary, since most Main Street loans are still outstanding.

. B C C S

A crucial goal of Main Street was to reach the “missing middle” of rms—those too large for

PPP support but too small to benet from the Federal Reserve’s support of the corporate bond

market.

2

Tens of thousands of U.S. rms have more than 500 employees (the PPP cuto) but

are not rated to issue bonds; these rms instead depend on banks (or other intermediaries) for

credit.

3

So, the story of Main Street begins with bank credit conditions in the spring of 2020. By

most indications, bank credit was tight, with rms demanding additional credit at the same

time that banks were contracting supply. And since the missing middle depends on banks, the

apparent crunch would likely aect them most.

e need for credit was suggested by the remarkable, if temporary, surge in bank business

lending in the spring (Chart 1). Commercial and industrial loans on banks’ books rose by over

a half a trillion dollars in the rst few months of the pandemic. e Federal Reserve’s Senior

Loan Ocers Survey (SLOOS) also indicated increasing demand for loans at the time. e

surge in demand was important in motivating Main Street, but the eventual reversal gures

later in how Main Street played out.

Much of this borrowing reected rms drawing against their credit lines with banks.

4

Most

large, corporate rms have committed lines from a bank for working capital and to back their

commercial paper. ose rms switch betweeen bank and public debt according to which is

cheaper; they are not very bank-dependent because they have alternatives. In contrast, more

detailed, firm-level data suggested at the time that some of the credit needs of smaller rms

might be going unmet, despite the surge in total credit. As shown in Chart 2, commitment bor-

rowing by rms with less than $5 billion in annual sales (the eventual revenue cuto at Main

Street) grew notably more slowly than for larger rms above that cutoff.

5

At the same time loan demand was increasing, banks appeared to be contracting supply. e

SLOOS revealed that banks raised risk premiums (Chart 3, le panel) and tightened standards for

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

3,500

C & I loans, all commercial banks (billions of dollars)

3,000

2,500

2,000

1,500

1,000

500

Sept. 8

2006 2009 2012 2015 2018 2021

C

Business Loans at Banks Surged in the Spring of 2020

Source: Federal Reserve H.8 Statistical Release, “Assets and Liabilities of Commercial Banks in the United

States.”

Notes: C&I is commercial and industrial. Shaded areas indicate periods designated as recessions by the

National Bureau of Economic Research.

Year-over-year quarterly change (percent)

80

60

20

40

0

–20

–40

–60

–80

2015 2017

More than $5 billion $1 billion to $5 billion

2019 2021

Q2

$500 million to $1 billion Less than $500 million

C

Lower Commitment Borrowing by Firms with Less Than $5 Billion in Revenues

Source: Federal Reserve Report FR-Y14Q, “Capital Assessments and Stress Testing.”

Notes: The chart shows growth in utilized commitments of commercial and industrial (C&I) loans to U.S.

nonnancial rms that report revenue (FR Y-9C category 4).

new loans (right panel) in the rst half of 2020. “Standards” includes the sorts of loan terms, such as

covenants and collateral requirements, that distinguish loans from less bespoke (“vanilla”) bonds.

While the net fraction of banks that reported tightening credit was about equal for rms of all

sizes, it is important to note that bank-dependent rms would be more aected than larger rms

with access to public debt markets, supported by the Federal Reserve’s corporate facilities.

6

e

SLOOS in the spring of 2020 also revealed that banks were tightening primarily because of the “less

favorable or more uncertain economic outlook” and “reduced tolerance for risk.” While not

surprising, that risk aversion and uncertainty informed the design of Main Street.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

2006 202120182015201220092006 20212018201520122009

Q2

Q2

Large and middle-market firms Small firms

Net percentage of banks raising risk premiums Net percentage of banks tightening standards

100

80

60

20

0

40

–20

–40

–60

–80

–100

80

100

60

20

0

40

–20

–40

–60

–80

–100

C

Banks Tightened Credit Supply in the Spring of 2020

Source: Federal Reserve, Senior Loan Ocer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices.

Notes: Large and middle-market rms are those with annual sales above $50 million. Shaded areas indicate

periods designated as recessions by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

It was this picture of surging demand and contracting supply in the spring of 2020 that led

the Federal Reserve to declare its intention to create a program to support credit to small and

medium-sized rms.

7

e actual program that emerged in the second half of 2020 is the topic

of the next section.

. T D M S

Designing Main Street was a complex undertaking. is section describes the overall objectives

of Main Street, the structure of the program, including key considerations that shaped its

design, and its implementation. As policymakers set out to design the program, they focused

on creating facilities that would make credit available to a suciently wide scope of rms

aected by the pandemic but, at the same time, limit risk to taxpayers. While a number of

policy, legal, and operational considerations shaped the program, the need to strike this careful

balance underpinned all key design decisions.

2.1 Program Objectives and Key Considerations

With Main Street, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury sought to provide credit support to

small and medium-sized businesses and nonprots impacted by the pandemic. e goal of

Main Street was to assist businesses and nonprots that faced credit constraints but were in

sound nancial condition prior to the pandemic and had good post-pandemic prospects, so

that they were in a position to benet from—and be able to repay—a loan. As already noted,

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

Main Street was intended to complement the Federal Reserve’s corporate credit and municipal

lending facilities that were launched to support larger businesses, states, and municipalities.

Several characteristics of the market for loans to small and medium-sized businesses high-

lighted above created challenges. ese loans are not traded like bonds or securitized like

mortgages; such markets (which tend to bring infrastructure, ratings, real-time prices, and a

degree of standardization) could otherwise have provided convenient on-ramps for program

design. Moreover, loans to small and medium-sized rms are some of the more individually

tailored (bespoke) nancial contracts—more bespoke than traded bonds or residential mort-

gages. Owing to the importance of relationship lending for these businesses, policymakers

were le without a readily available, standardized set of loan terms or credit metrics that could

easily be converted into a program term sheet and quickly scaled for thousands of businesses.

Additionally, while it was dicult to predict the scale and scope of demand for the program

from the outset, conditions in the spring of 2020 pointed to large potential demand. Although

the Federal Reserve is very experienced in credit analysis for its supervision and monetary

policy functions, it would have needed to hire a large number of loan ocers to directly origi-

nate and process loans to the thousands of companies that could potentially have qualied.

Hiring such personnel quickly and in sucient numbers from the banking sector, which was

itself facing unprecedented demand for loans, was impractical—thus necessitating a role for

private lenders. e swi onset of the pandemic and the fact that the Federal Reserve lacked

previous experience setting up a small and medium-sized business credit support program

also created design complications.

e program was authorized under Section 13(3), as amended, of the Federal Reserve Act

and was capitalized, in part, by funds appropriated under the CARES Act; each act inuenced

the specic design of the Main Street facilities. Section 13(3) provides lending authority but

prohibits loans to “insolvent” borrowers and requires that the lending Reserve Bank be

“indorsed or otherwise secured” to its satisfaction.

8

(See Box 1 for a brief history of Federal

Reserve credit policy directed specically to businesses under Section 13(3).) e application

of the CARES Act set forth eligible borrower criteria and placed limits on borrowers’ ability to

distribute capital or set compensation above given thresholds.

9

2.2 Program Design

With these economic, operational, and legal considerations as a backdrop, policymakers at the

Federal Reserve and the Treasury settled on a loan participation program to support the supply of

credit. Banks would be able to sell 95 percent stakes in eligible loans at par to the Main Street special

purpose vehicle (SPV), with the credit risk shared between the SPV and lenders pro rata.

e loan participation model was chosen for three reasons. First, it leveraged lenders’ exist-

ing infrastructure for originating, monitoring, and servicing loans as well as their expertise in

assessing and controlling risk—expertise that is oen local and specialized.

Second, because the participation model transferred the bulk of the loans and associated risks

from the lenders to the Main Street program, it helped mitigate the acute economic uncertainty

and risk aversion that was driving the tightening credit supply in the spring. As an added benet,

removing 95 percent of the loan amounts from banks’ balance sheets would also free up bank

capital to recognize losses and maintain lending outside the Main Street program.

10

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

B

The Federal Reserve’s Historical Experience with Direct Lending to Businesses

e Main Street program represented the rst time since World War II that the Federal Reserve ac-

tively pursued policies to direct bank lending to the nonnancial business sector. e origins of the

Fed’s previous experience with direct lending to businesses traces back to the addition of Section

13(3) to the Federal Reserve Act, which occurred during the Great Depression.

a

In January 1932, legislation was passed to create the Reconstruction Finance Corporation

(RFC), which was designed to make short-term loans to banks and other nancial institutions,

collateralized by real bills (short-term debt from businesses). e creation of the RFC was a means

of injecting capital into the weakened banking system; however, the RFC’s ability to extend loans

outside of the banking system was limited. Recognizing this, Congress passed a bill in the summer

of 1932 that added Section 13 paragraph 3 to the Federal Reserve Act.

Congress further expanded the lending authority of the Federal Reserve by adding Section

13(b) to the Federal Reserve Act in June 1934.

b

Section 13(b) allowed Reserve Banks to directly

extend loans to businesses within their districts for periods of up to ve years. It also gave the

Reserve Banks the ability to participate in loans with lending institutions, provided those lending

institutions retained 20 percent of the risk of the loan. In contrast with Main Street, no limitations

were placed on the size of an individual loan. is Great Depression–era facility was funded in

equal part by the surplus of the Reserve Banks as of mid-1934 and the Treasury. All told, nearly

$280 million ($5.4 billion in 2020 dollars) was made available for Reserve Bank lending, with each

of the twelve Districts being apportioned a partial amount of the total. Relative to the overall size

of the economy, this quantity of funding was about 0.5 percent of GDP in 1934. In comparison,

Main Street’s capacity as a share of 2020 GDP was about six times as large.

c

By May 1935, roughly a year aer the passage of Section 13(b), the Federal Reserve System

had approved 961 loans issued directly to businesses totaling $43.9 million ($847.9 million in

2020 dollars). Interestingly, as a share of contemporaneous GDP, this uptake is nearly identical to

Main Street’s. Because each Reserve Bank had access to funds, lending was, by design, dispersed

geographically across all twelve Districts. In addition, the loans went to a broad range of industries,

including construction, lodging, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and wholesale and retail

trade—many of the same industries that took Main Street loans.

d

All told, loan volume peaked at

about $60 million by the end of 1935 ($1.2 billion in 2020 dollars). With peak volume amounting

to more than 15 percent of the total funds available, utilization was much higher relative to Main

Street.

e

Main Street’s lower utilization likely reects that it operated for only about six months, and

also that the program designs diered notably.

e Federal Reserve’s lending activity to nonnancial businesses gradually declined aer 1935 as

expanded lending through the RFC made direct loans from the Federal Reserve less attractive.

(C )

a

For an extensive treatment of this history see Hackley (1973).

b

For useful summaries of the history of Section 13(b), see Fettig (2002) and Sablik (2013).

c

With Treasury’s equity commitment and the SPV’s leverage cap, up to $600 billion was potentially available

through Main Street, about 3 percent of the size of the $20.9 trillion U.S. economy in 2020.

d

See Sablik (2013) for more details on the industry composition of 13(b) loans as of mid-1935.

e

Main Street loan volume totaled $17.4 billion at the end of 2020, about 3 percent of the $600 billion in

total available funding.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

B (C)

Section 13(b) remained in place and, in fact, activity peaked again in 1942 when the Federal

Reserve was called upon to make industrial loans during World War II. e role of the Federal

Reserve in allocating credit to businesses remained a hotly debated issue throughout the 1950s, but

ultimately Section 13(b) was repealed in 1958. e 13(3) powers, however, remained part of the

Federal Reserve Act and played an important role in implementing Main Street in response to the

COVID-19 pandemic.

Third, the participation model allowed for an appropriate balance between reach and

risk. The substantial risk-bearing by the Federal Reserve promoted reach, while the resid-

ual bank risk-bearing maintained some economic incentives for lenders to control risk. To

complement these incentives and further minimize the risk of adverse selection—the pos-

sibility that banks would offload their worst new loans to Main Street—the Main Street

program also limited borrower leverage and imposed requirements for priority and

collateral.

e program was executed through an SPV set up by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

that was funded with a loss-absorbing tranche of Treasury equity (that is, CARES Act funds),

as well as loans from the Reserve Bank. Given the widespread uncertainty at launch, Main

Street was created with a sizable maximum capacity of up to $600 billion in participations, in

case that much support would be needed.

Main Street ocially began purchasing loan participations on July 6, 2020. It oered to pur-

chase participations in three distinct types of loans—new loans, priority loans, and expanded

loans—through three separate facilities: Main Street New Loan Facility (MSNLF), Main Street

Priority Loan Facility (MSPLF), and Main Street Expanded Loan Facility (MSELF), respec-

tively. While certain terms were common across all three loan types, there were also important

dierences, including loan size, permissible leverage levels, and collateralization requirements

to accommodate a range of borrower and lender circumstances. e term sheets were posted

for public feedback and were adjusted in response to such feedback several times, both before

and aer the start of operations, as discussed below. e nal loan terms for the for-profit facil-

ities are shown in Table 1.

Loan terms

While the terms for small and medium-sized business loans are generally tailored to the facts and

circumstances of the borrower, some Main Street loan terms were standardized to allow the

program to function while balancing reach and risk. For example, standardized interest rates and

loan maturities enabled Main Street to purchase participations at par without the need to develop

a complex loan pricing model. An interest rate of LIBOR plus 300 basis points with zero prepay-

ment penalty implemented the Regulation A requirement that Federal Reserve emergency

lending be extended at a suciently high rate of interest relative to non-stressed conditions to

provide an incentive for rapid repayment when conditions normalize. In keeping with the

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

objective of helping borrowers bridge the pandemic, Main Street loans were given an amortiza-

tion schedule that back-loaded loan repayment, deferral of interest and principal payments for

a year (principal payments were later deferred for two years), and a five-year loan term. e

deferral was intended to alleviate short-term nancial strain on Main Street borrowers.

Lenders had discretion over loan size up to a limit, either a nominal dollar limit or a lever-

age limit, whichever was smaller. e leverage limit, which turned out to be more binding, was

a primary mechanism for limiting risk to the program. When added to the borrower’s existing

debt, the Main Street loan could not exceed four (MSNLF) or six (MSPLF, MSELF) times the

borrower’s 2019 adjusted earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization

(EBITDA). In addition to limiting the size of Main Street loans for participants, these leverage

limits also had the eect of excluding some highly levered or unprotable rms altogether.

e choice to use 2019 EBITDA was motivated by the program’s goal to help borrowers that

were temporarily suering from the pandemic but that had been fundamentally solvent prior

to the onset of the pandemic.

In addition to the leverage limits and the lender’s risk retention, the tradeo between risk

and reach was also managed through security and priority requirements. All Main Street loans

were prohibited from being contractually subordinated to any existing borrower debt in terms

of priority in bankruptcy. While priority and expanded loans allowed higher leverage than new

loans, they were required to be senior to, or pari passu with, all existing borrower debt in terms

of collateral securing the loans, except for mortgage debt (as dened by the program). Lenders

were ultimately responsible for determining that borrowers were in sound condition prior to

the crisis and had strong post-pandemic prospects that would enable repayment of the Main

Street loan.

T

Key Main Street Loan Terms of Facilities for For-Prot Borrowers (Final Terms)

New Loan Facility Priority Loan Facility Expanded Loan Facility

Loan term 5 years

Principal payments

Principal deferred for two years.

Years 3-5: 15 percent, 15 percent, 70 percent, respectively

Interest payments Deferred for one year

Interest rate 1- or 3-month LIBOR + 3 percent

Loan size

$100,000 to

$35 million

$100,000 to

$50 million

$10 million to

$300 million

Maximum combined debt to adjusted

2019 EBITDA (including principal

amount of Main Street loan)

4 times 6 times 6 times

Lender participation rate 5 percent

Federal Reserve participation rate 95 percent

Prepayment allowed Yes, without penalty

Business size limits 15,000 employees or fewer, or 2019 revenues of $5 billion or less

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/

mainstreetlending.htm.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

Finally, the program allowed borrowers to renance existing debt, but only in a single facil-

ity, the MSPLF, and only debt owed to a dierent lender, to avoid the risk that lenders would

shi poorly performing debt on their own books to the program.

Borrowers

To target small and medium-sized businesses, the program limited eligibility to rms with

fewer than 15,000 employees or less than $5 billion in annual revenues (including aliates).

11

To help those businesses that lacked access to an alternative support program, these caps were

deliberately set above those used for the PPP (500 employees) or other Small Business Admin-

istration (SBA) lending (with size thresholds that vary by industry) but lower than the level at

which a company might generally have access to nancing in capital markets and thus be sup-

ported by the Federal Reserve’s corporate credit facilities. e aforementioned nominal loan

size limits, all well above the $10 million maximum for the PPP, played a similar role. In other

words, Main Street was intended to ll a gap in credit support for the “missing middle.”

In dening eligibility criteria, the Board also referenced the SBA’s exclusion of “ineligible

businesses”—a list of categories formulated especially to place reasonable limits on the types of

companies that could receive government-backed business lending.

12

is framework, particu-

larly the denition of ineligible business, was designed to mitigate fraud risk and limit evasion

of facility restrictions.

13

Further, Main Street program borrowers were subject to the require-

ments for participants in direct loan programs set forth in the CARES Act. In particular, a

borrower needed to commit to follow compensation, stock repurchase, and capital distribution

restrictions under Section 4003(c)(3)(A)(ii) of the Act. ese requirements would remain in

place until a year aer the Main Street loan was fully repaid.

Lenders

All Main Street facilities relied on private lenders and their existing underwriting infrastruc-

ture to apply appropriate expertise and enable the program to scale rapidly. In contrast to the

PPP, which allowed a broad set of eligible lenders to supply its forgivable loans, the Main

Street program limited eligible lenders to federally regulated and supervised organizations,

including banks and credit unions, to ensure that Main Street lenders’ underwriting stan-

dards and “know your customer”/anti-money laundering practices were subject to strong

and ongoing supervisory oversight.

14

While a wider set of eligible lenders might have

extended the reach of the program, the use of established and well-regulated banking orga-

nizations and credit unions was viewed as an important way to control potential taxpayer

risks in the program. As it turns out, virtually all of the participating lenders were commer-

cial banks (as we discuss later), so for brevity we will oen refer to eligible lenders simply

as “banks.”

Under the program terms, lenders were expected to underwrite Main Street loans using

their existing underwriting practices. Subsequent program guidance provided through FAQs

also claried supervisory expectations. Lenders were directed to underwrite Main Street loans

by looking at borrowers’ pre-pandemic nancial condition and post-pandemic prospects.

15

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

Lender incentives and the participation agreement

Several incentives for banks to participate were built into the program, since, to be successful,

Main Street required the active participation of lenders. First, as discussed above, the risk-sharing

with Main Street allowed banks to help existing and new customers without taking on much new

credit risk or needing to signicantly expand their own balance sheets. Second, to cover lenders’

loan origination and servicing costs and further boost incentives, lenders were able to benet

from fees: an origination fee of up to 1 percent (on the full principal) and an annual servicing fee

of 0.25 percent of the Main Street SPV’s loan share.

16

Given the banks’ limited initial investment,

these fees, together with banks’ 5 percent share in interest and principal repayments, in principle,

enabled a lender to receive reasonable returns even under the most adverse credit scenarios con-

sidered (discussed further below). at said, for loans with signicant origination or servicing

costs, the lender’s return would be lower. While data on origination and servicing costs are scant,

commercial and industrial (C&I) loan fees can be signicant, possibly suggesting that such costs

are also signicant. For example, in the market for syndicated term loans to businesses, upfront

fees (where observed) average about 80 basis points, with considerable variation around that

average (Berg, Saunders, and Steen 2016). In addition, lender incentives in the MSELF were

complicated due to interactions with the loan that was being expanded, including the possibility

that the collateral on the existing loan was diluted.

17

To operationalize the loan participation model, the Federal Reserve created a loan partici-

pation agreement based on market-standard models, with adjustments for certain features of

the program. e market-standard provisions were generally familiar to lenders that use par-

ticipations or engage in syndicated lending; this was intended to help smooth the on-ramp for

many potential lenders. While these documents were less familiar to the program’s smaller bor-

rowers, they played an important function in the program because their provisions were

generally viewed as facilitating a “true sale,” which (among other things) enabled lenders to

move 95 percent of the loan amounts o their balance sheets for purposes of bank capital

rules, thus promoting lender participation by freeing up regulatory capital.

In comment letters and outreach, lenders expressed concerns that the Federal Reserve

would “put back” nonperforming loans to the lenders by arguing that the loans were originated

imprudently. To alleviate such concerns and promote participation, the Federal Reserve added

a clause to the agreement preventing put-backs. e Federal Reserve also waived and dis-

claimed its rights to special priority in bankruptcy among unsecured lenders to enhance the

ecacy of the program and provide certainty to lenders and borrowers.

Income and loss projections during the design phase

Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act and the CARES Act required that the Federal

Reserve’s investment be appropriately secured and that taxpayers be protected. Accordingly,

when deciding on loan terms, risk-sharing arrangements, and fees, the Federal Reserve and

Treasury had to gauge the eect of these choices on the potential gains or losses from Main

Street’s operations. To do so, sta projected bounds for the SPV’s net income under various

credit risk scenarios and design choices, akin to a stress test. Multiple scenarios, with varying

degrees of adversity, were used, both to ensure that the statutory taxpayer-protection

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

requirement would be satised under a range of adverse conditions and because at the time

that the program was being designed the economic outlook was extremely uncertain. e

appendix describes the scenarios and projections in more detail.

e results of these projections also guided the decision to cap SPV “leverage” at 8-to-1.

Given Treasury’s planned $75 billion equity investment, the net leverage cap dictated a

maximum program size of $600 billion. With that cap, even under adverse scenarios, the

Federal Reserve was projected to incur zero losses.

Infrastructure

Once the design was generally decided on, the next step was to build, from the ground up,

the technological infrastructure and risk control mechanisms needed to operate the

program. e loans in which Main Street would be participating could not simply be pur-

chased “in the market” as with the corporate credit programs, so the Federal Reserve Bank of

Boston (which operates the program) had to create an electronic portal through which

banks could register and submit loans for participation. To address the risk of fraud or pro-

cessing mistakes, multi-step processes that would verify lender registrations and loan

documents had to be developed. All told, building this infrastructure from scratch was a

complicated task given the lack of an existing blueprint, and this complexity slowed the

launch relative to other credit facilities implemented by the Federal Reserve or loan pro-

grams in other countries that were built on existing infrastructure. (See Box 2 for more

details on how other central banks and governments facilitated the ow of credit to small

and medium-sized businesses).

When submitting a loan, lenders uploaded the loan agreements and other relevant loan

documents to the portal. Automated eligibility checks were augmented by a manual review for

adherence to certain core program requirements; the review was done by Federal Reserve

Bank of Boston sta and hired vendors, including the Main Street credit administrator and

external counsel. Importantly, the SPV did not re-underwrite Main Street loans.

Additional program adjustments

In an eort to respond to the credit needs of nonprot organizations and smaller borrowers, a

need that became increasingly apparent in summer and early fall 2020, Main Street was

amended to introduce two facilities for small and medium-sized nonprot organizations—the

Nonprot Organization New Loan Facility (NONLF) and the Nonprot Organization

Expanded Loan Facility (NOELF) —and to enable the facilities’ participation in smaller loans.

e nonprot sector was hit particularly hard by the social-distancing requirements put in

place to slow the pace of the pandemic. Demands for their services (for example, care for

COVID-19 patients, online learning, and social services) spiked at the same time key sources

of income (such as elective surgical procedures, tuition, and donations) declined or were at risk

of declining. Designing a program for this sector presented additional challenges, given that

many nonprots were designed to minimize rather than maximize earnings, making it dicult

to meet the program’s pre-pandemic leverage thresholds, and many had limited experience

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

B

Lending Programs to Support Nonfinancial Businesses During the Pandemic:

The International Experience

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant effect on small- to medium-sized businesses not

only in the United States but in countries throughout the world. Accordingly, an important

aspect of the policy response in many countries involved creating lending programs, some of

which were similar to Main Street, to support the flow of credit to households and nonfinan-

cial businesses.

e most similar international programs were the Bounce Back Loan Scheme (BBLS) and

the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS), both implemented in the United

Kingdom, and the Prêt Garanti par l’État (PGE), implemented in France. In the broadest sense,

the intent of these programs was to facilitate lending to nonnancial businesses that were hit

hard by the pandemic and that, absent support, could potentially be forced to reduce employ-

ment and economic activity.

a

One common feature of all three of these programs is that the

loans were either fully or partially backed by government guarantees of repayment in the event

that the borrower defaults. is feature signicantly reduces the amount of exposure a bank fac-

es and, as a result, makes participation more attractive. In contrast, the strong desire to protect

taxpayers by not guaranteeing loans made the Main Street program dierent from the BBLS, the

CBILS, and the PGE.

Beyond these lending programs, many central banks acted unilaterally (that is, not in con-

junction with the country’s Treasury or the Ministry of Finance) to promote credit to certain

segments of the credit market. In this regard, the most common policy response was to establish

a funding-for-lending scheme, whereby the central bank provides low-cost funding to banks

that then use those funds to extend loans to a targeted set of borrowers (small and medi-

um-sized enterprises, or SMEs).

b

Examples of targeted funding-for-lending programs intro-

duced by foreign central banks include those implemented by the Bank of England (the Term

Funding Scheme with Additional Incentives for SMEs), the Bank of Japan (the New Fund-Provi-

sioning Measure to Support Financing Mainly of Small and Medium-Sized Firms), the European

Central Bank (the modied Targeted Longer-Term Renancing Operations III), the Reserve

Bank of Australia (the Term Funding Facility), and the Sveriges Riksbank (Loans to Banks for

Onward Lending to Companies).

e Main Street Lending Program is very dierent from a funding-for-lending scheme. In the

simplest terms, the dierence boils down to what creates the incentive for a participating bank to

increase lending to a targeted set of borrowers. Under a funding-for-lending scheme this incentive

comes from low-cost funding provided by the central bank, while under Main Street it comes from

the opportunity to originate a loan and sell a large portion of the risk to the Federal Reserve while

still retaining the servicing rights.

a

See Briggs and Walker (2020) for a fuller discussion.

b

See Cantu et. al., (2021) and Cavallino and DeFiore (2021).

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

managing longer-term debt. e terms of the nonprot facilities sought to balance these chal-

lenges by setting out dierent and additional eligibility requirements to capture those for

which a loan product would be most beneficial.

18

Similarly, policymakers received repeated feedback during the life of the program that some

small businesses and nonprots would benet from a loan smaller than the minimum size per-

mitted originally. In response, the program was adjusted to allow for loans as low as $100,000

in the MSNLF, MSPLF, and NONLF. e program fees were also adjusted upward for the

smallest loans, in order to compensate lenders for the proportionally larger potential cost asso-

ciated with originating small loans.

. M S A

Over its six-month run, Main Street purchased 1,830 loans with a combined principal amount

of $17.5 billion, more than any of the Federal Reserve’s other debt-purchase programs. Its

volume, although small relative to capacity, was a meaningful addition to the ow of credit—

roughly comparable, for example, to the amount of lending by the largest banks (those with

consolidated assets greater than $100 billion) over the second half of 2020 to borrowers with

similar characteristics, that is, within the eligibility parameters but outside the Main Street

program. is section describes in detail Main’s Street activity and its limits, including loan,

lender, and borrower characteristics.

A look at the portfolio yields the following high-level observations. e average loan was

$9.5 million, substantially larger than the average PPP loan, suggesting the program supported

rms too large for PPP loans. Loan size was oen dictated by the program’s leverage limits

dened above (of four and six times EBITDA). e lenders were nearly all commercial banks.

Most active lenders were in the $250 million to $10 billion asset-size range, although the

largest banks (those with assets of more than $1 trillion) also participated to some extent. e

program’s reach was wide, with borrowers from nearly all states, and state-level activity tended

to correlate positively with COVID-19 cases and increases in a state’s unemployment rate. Bor-

rowers were, on average, somewhat riskier than the typical borrower found in the portfolios of

the largest banks, possibly reecting dierences between the types of borrowers that seek loans

from the largest banks and those that seek loans from other banks (that is, those with assets of

less than $1 trillion).

4.1 Overall Activity

e program began accepting participations on July 6, 2020, and ended on January 8, 2021.

Activity grew modestly but steadily until early December, when it surged in advance of the

December 14 deadline for submitting new participations (see Chart 4, le panel). Roughly

half of the overall volume of the program occurred in the nal month of the program.

19

All

told, the late surge in loan purchases pushed Main Street’s volume above that of any debt

purchase (versus liquidity) facility created by the Federal Reserve during the pandemic

(right panel).

20

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

Main Street loans also constituted a meaningful addition to the overall ow of credit during

the program’s active phase. As shown by Bräuning and Paligorova (2021), the cumulative

volume of Main Street lending was about 60 percent of the volume of term loans originated

during the same time span by large banks (FR Y-14Q lers) to borrowers of similar size and

leverage (that is, borrowers with less than $5 billion in annual revenues and leverage below six

times EBITDA). Moreover, when considering smaller rms (those with less than $50 million in

EBITDA), Main Street lending substantially exceeded the supply of credit by the largest banks

to borrowers of comparable size. When also imposing the six times EBITDA leverage limit in

the Y-14Q data, Main Street lending was about twice as large as lending by the largest banks to

comparable borrowers.

21

At the same time, Main Street volumes were low when compared with the surge in C&I

lending from credit line drawdowns in March 2020, or when compared with the maximum

capacity of the program, as noted. In part, this reected much weaker loan demand aer the

launch of the program in July 2020, as discussed in Section 2. Reach was likely also constrained

by certain program features, a theme we return to below.

Table 2 summarizes the Main Street purchases by loan type and size. e bottom line shows that

priority loans and new loans turned out to be more in demand than expanded loans. e 1,173 pri-

ority loans accounted for nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of total volume while the 616 new loans

made up 15.5 percent. e 26 expanded loans accounted for the balance. As stated above, expanded

loans entailed modifying existing credit agreements, which may have reduced demand for these

loans. e Nonprot New Loan Facility (NONLF) was very small both in the number and volume

of loans, and the Nonprot Extended Loan Facility (NOELF) was not used at all.

Table 3 summarizes the size distribution of loans made across the dierent facilities. Most

loans were in the range of $1 million to $50 million, with an average of $9.5 million and

median of about $4 million. In comparison, the average PPP loan was just $101,000, suggest-

ing that Main Street succeeded in targeting rms that were too large for the PPP but too

small to access the bond market. At the program’s inception, the minimum loan size was

0

5

10

15

20

MSELF NONLFMSPLF MSNLF

–5

0

5

10

15

20

25

Main Street

Corporate bonds

Municipal bonds

Commercial paper

TALF II

2020 2021

Sep 14

Aug 17

Jul 20

Billions of dollars

Total Volume of Accepted MSLP

Submissions by Facility

Asset Purchases at Federal Reserve

Credit Facilities

Billions of dollars

Nov 9 Dec 7

Oct 12

C

Loan Purchases at Main Street and Other Credit Facilities

Sources: MSLP data; Federal Reserve, H.4.1 Statistical Release, “Factors Aecting Reserve Balances.”

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

$250,000, but this threshold was lowered to $100,000 for certain facilities on October 30 to

better target support for small businesses. ere were, however, only 22 loans smaller than or

equal to $250,000 at the end of the program. On the other end of the size distribution, there

were a small number of loans made through the MSELF that were larger than $50 million,

together totaling $1.5 billion—almost 10 percent of the overall Main Street volume. e

largest loan made through this facility was $300 million, the maximum loan size for

expanded loans.

4.2 Borrower Characteristics

Altogether, 2,453 borrowers and co-borrowers took out a total of 1,830 loans.

22

Table 4 proles

borrowers in terms of revenue, leverage, and assets as of 2019. e average revenue was

T

Loan Volume (in Millions) and Count, by Loan Type and Size

Expanded Loans New Loans Priority Loans Nonprot Loans Total

Loan Size

(Dollars)

Volume Count Volume Count Volume Count Volume Count Volume Count

≤250K 4 19 0.3 2 0.2 1 5 22

250-500K 26 68 12 28 0.9 2 39 98

500K-1M 95 118 65 82 1 2 161 202

1-10M 20 2 1,221 350 3,034 671 40 10 4,314 1,033

10-35M 238 10 1,349 61 5,809 304 7,396 375

35-50M 81 2 3,997 86 4,078 88

>50M 1,466 12 0 0 1,466 12

All loans 1,805 26 2,695 616 12,917 1,173 42 15 17,459 1,830

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

Note: Entries may not sum to total due to rounding.

T

Main Street Loan Size Distribution, by Type

Loan Size (in Millions)

Mean Min p10 p25 p50 p75 p90 Max

Expanded loans 69.4 10.0 11.0 22.0 40.5 90.0 148.0 300.0

New loans 4.4 0.1 0.4 0.8 2.0 4.5 10.0 35.0

Priority loans 11.0 0.1 1.1 2.4 6.0 14.8 30.0 50.0

Nonprot loans 2.8 0.2 0.4 0.6 2.5 5.0 5.0 8.5

All facilities 9.5 0.1 0.7 1.5 4.0 10.6 25.0 300.0

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

T

Main Street Borrower Financial Characteristics

Metric Mean p25 p50 p75 Count

2019 Revenue (millions of dollars) 33.9 3.9 11.5 31.8 1,830

2019 Leverage (multiple of EBITDA) 1.1 0.0 0.6 1.8 1,830

Assets (millions of dollars) 26.2 1.5 6.3 21.6 1,830

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

$33.9 million. e pre-pandemic levels of leverage were relatively low, with the average being

just above one multiple of EBITDA. Borrowers’ average asset size was $26.2 million, consistent

with the program’s target of reaching medium-sized rms. Moreover, Main Street borrowers

saw an average revenue decline of about $7 million during the rst two quarters of the pan-

demic, relative to their most recent pre-pandemic reporting in 2019. is illustrates that Main

Street helped many borrowers that were hit hard by the pandemic but were solvent and viable

businesses before the crisis started.

Main Street supported borrowers across a diverse range of industries (see Table 5). e top

industries by loan volume were accommodation and food services; manufacturing; real estate

and rental and leasing; mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction; and transportation and

warehousing. By loan count, professional services was second to accommodation and food ser-

vices, with manufacturing third and construction rms fourth. e least active industries in

terms of both loan volume and counts were utilities, agriculture and forestry, and public

administration.

The geographic reach of Main Street borrowers was also wide, with borrowers in nearly

every state. The most active states by volume were Texas ($3.1 billion), Florida

($2.1 billion), California ($2.1 billion), Ne w Yor k ($700 million), and Missouri

($700 million).

23

It is also useful to look at loan volumes relative to state GDP, as shown in

Exhibit 1. Using this normalization, the top five states were Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri,

Florida, and Texas.

Chart 5 provides further evidence suggesting that Main Street reached borrowers in indus-

tries and regions that were hit hard by the pandemic. e le panel shows that 72 percent of

total Main Street lending went to COVID-affected industries.

24

e right panel shows that

state-level Main Street borrowing in any month was positively correlated with the previ-

ous month’s COVID-19 positivity rate in the borrower’s state, controlling for state GDP per

capita and time xed effects.

25

4.3 Lender Characteristics

A total of 643 lenders successfully registered to participate in the Main Street Program, all but

27 of which were commercial banks. at represents about 1 in 7 of all FDIC-insured banks, a

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

meaningful share for a six-month program. About half of these banks (316) sold loans to Main

Street, while 327 did not actively participate despite being registered.

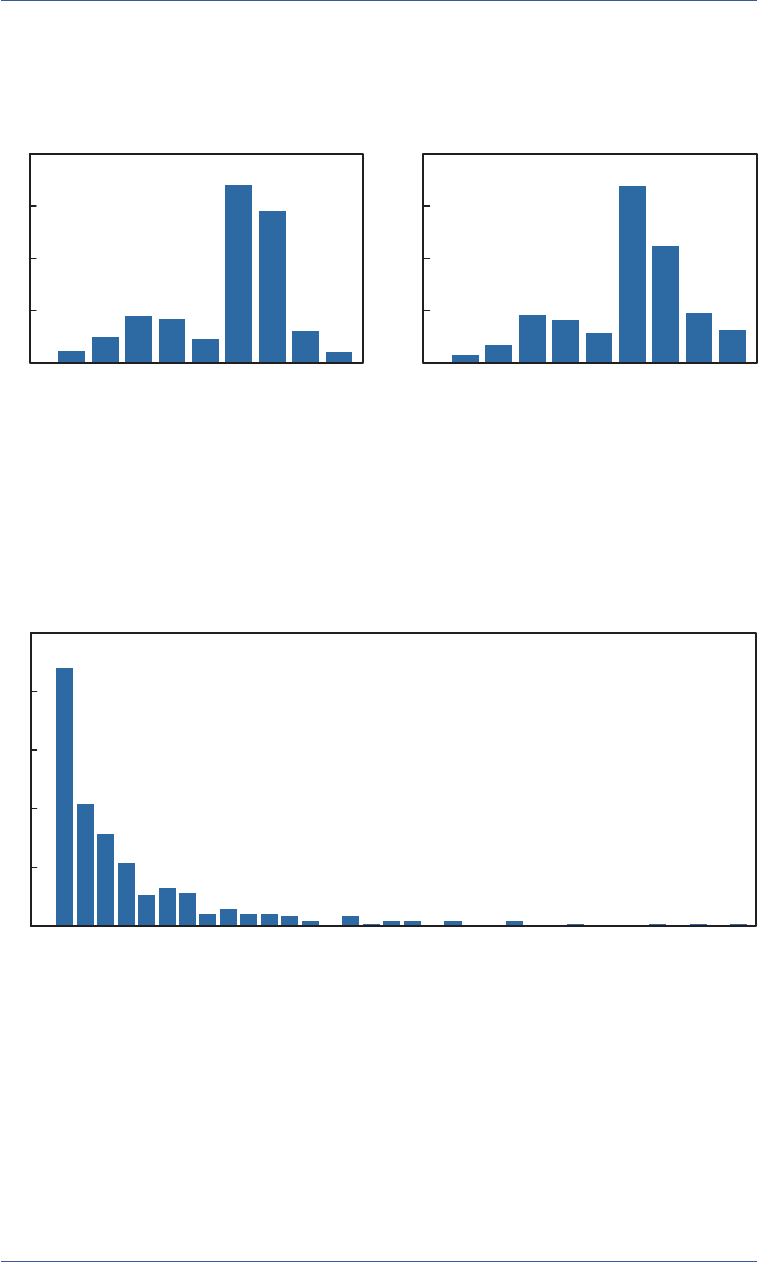

Chart 6 shows that Main Street lending activity was dominated by banks that were small to

medium-sized in terms of total assets. Most active banks were in the $250 million to

$750 million range or the $1 billion to $50 billion size range (le panel). e share of registered

lenders increases with each size group (right panel, blue and gold portions of the bars). Very

small banks (less than $250 million in assets) were underrepresented.

Chart 7 shows lending intensity by bank asset size. Banks in the $1 billion to $10 billion

asset-size category account for 34 percent of the total number of loans and 34 percent of the

total volume of loans; banks in the $10 billion to $50 billion asset-size group account for

29 percent of loans and 21 percent of volume; and banks in the $250 million to $500 million

and $500 million to $750 million size groups together account for 17 percent of loans and

volume. While the volume of Main Street loans issued by banks with assets of $1 billion or

T

Main Street Borrowers by Industry

Industry

Volume

(Millions of Dollars)

Percentage of

Volume

Loan

Count

Percentage of

Loan Count

Accommodation and food services 2,182 12.5 268 14.6

Manufacturing 1,711 9.8 169 9.2

Real estate 1,659 9.5 141 7.7

Mining, oil and gas extraction 1,468 8.4 90 4.9

Transportation 1,397 8.0 107 5.8

Arts and recreation 1,242 7.1 117 6.4

Professional services 1,159 6.6 171 9.3

Construction 1,132 6.5 166 9.1

Wholesale trade 961 5.5 112 6.1

Information 907 5.2 92 5.0

Health and social care 837 4.8 71 3.9

Administrative support services 796 4.6 60 3.3

Retail trade 618 3.5 92 5.0

Other services 352 2.0 64 3.5

Educational services 307 1.8 26 1.4

Finance and insurance 237 1.4 49 2.7

Management 230 1.3 18 1.0

Utilities 186 1.1 8 0.4

Agriculture and forestry 76 0.4 8 0.4

Public administration 1 0.01 1 0.1

Total 17,459 100 1,830 100

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

Note: Entries may not sum to total due to rounding.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

more account for 55 percent of the total Main Street lending, these banks’ total assets represent

95 percent of the U.S. banking system’s assets.

Most banks active in the program sold just one or two loan participations (Chart 8). e

banks that sold multiple participations tended to sell fewer than 10, though several lenders

sold more than 20, and there were a few extremely active participants that sold more than 30

loans, suggesting once a lender had experience with the loan process, scale was possible.

Registered banks tended to have a higher concentration in C&I lending than nonregistered

banks, regardless of their size. e le panel of Chart 9 shows that dierences in C&I concen-

tration between registered and nonregistered lenders are signicant for any size bin. Moreover,

the panel on the right shows that the intensive margin is positively correlated with the concen-

tration. Banks that were more active in the Main Street program tended to have a higher

concentration in C&I lending measured before the pandemic.

4.4 Program Features and Take-up

Many of Main Street’s features were chosen to balance the tradeo between the reach of the

program and the riskiness of the loans made to borrowers. is section takes a very prelimi-

nary look at how the program performed in terms of striking that balance—preliminary since

the ultimate credit performance of the Main Street loans is not yet known.

Regarding determinants of reach, Table 6 shows that loan size was more oen limited by

the leverage cap than by the nominal maximum loan size. About 30 percent of borrowers were

within 5 percent of the relevant leverage limit. In addition, on the extensive margin, the

1

2

3

GDP−normalized

volume

Exhibit 1

Main Street Loan Volume Divided by State GDP

Source: MSLP data.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

0

20

40

60

80

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

100

Billions of dollars

Share Monthly (log) total MSLP uptake

Share to highly affected industries (right scale)

Total biweekly flows (left scale)

6

5

4

2

3

0

02468101214161820

Relationship Between State-Level COVID-19

Positivity Rate and Main Street Uptake

Lagged (one-month) COVID-19

testing positivity

Jul 27

Aug 10

Jul 13

Aug 24

Sep

7

Sep 21

Oct

5

Oct 19

Nov 2

Nov 16

Nov 30

Dec 14

C

Main Street Credit Reached Highly Affected Industries and States

Sources: Authors’ calculation using MSLP data (left panel). Authors' calculation using MSLP data, Bureau of

Economic Analysis, and Opportunity Insights data (right panel).

Notes: COVID-aected industries include entertainment and recreation, oil and gas, real estate, retail, and

transportation services. Data in right panel are orthogonalized with respect to calendar month and state GDP

per capita. Each dot represents a U.S. state.

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

Fraction of banks in each status group

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

Fraction of banks in each status group

Registered active Registered inactive

Not registered

<100M

100-250M

250-500M

500-750M

750M-1B

1-10B

10-50B

50B-1T

>1T

<100M

100-250M

250-500M

500-750M

750M-1B

1-10B

10-50B

50B-1T

>1T

Banks by asset size (dollars) Banks by asset size (dollars)

C

Lenders Size Distribution by Registration Status

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

Notes: Registered active banks are those with accepted special-purpose vehicle (SPV) loans. Registered

inactive banks have either zero or rejected submissions to the SPV.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

leverage limits also completely excluded some potential borrowers with high leverage. Con-

versely, less than 4 percent of borrowers were within 5 percent of the loan size upper limit, also

across all three facilities.

Although it is still too early to fully assess the riskiness of loans made through the Main

Street program, it is nonetheless informative to compare the characteristics of Main Street

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

Fraction of total loans Fraction of total loans

Loan Count Loan Value

<100M

100-250M

250-500M

500-750M

750M-1B

1-10B

10-50B

50B-1T

>1T

<100M

100-250M

250-500M

500-750M

750M-1B

1-10B

10-50B

50B-1T

>1T

Banks by asset size (dollars) Banks by asset size (dollars)

C

Main Street Lending Activity by Lender Size

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

0

25

50

75

100

125

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34

Number of loans

Number of banks

C

Number of Loans Sold per Bank

Source: MSLP data.

Note: Selected banks were excluded for legibility.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

0

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

0.35

5

10

15

20

25

<100M

100-250M

250-500M

500-750M

750M-1B

1-10B

10-50B

50B-1T

>1T

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350

Banks by asset size (dollars)

MSLP volume (millions of dollars)

Weighted average ratio Percent

C&I/RWA among Active Banks

Nonregistered lenders

Registered lenders

C&I/RWA by Bank Size and

Registration Status

C

C&I Loan Concentration by Lender Registration and Activity

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

Notes: Left panel: Ratios as of 2019:Q4 are weighted by risk-weighted assets (RWA). * denotes statistically

signicant dierence in mean of registered versus unregistered lenders, by asset size, at the 95 percent

condence level. Right panel: Selected banks were excluded for legibility.

loans with those of a set of similar loans made outside the program. For loans made outside

the program, we use loan-level data from the Federal Reserve’s Y-14Q (Y-14) data covering the

largest banks that were subject to stress tests over the same time period as the Main Street

program.

26

Chart 10 (le panel) shows that Main Street borrowers tended to be smaller and more lev-

eraged than a large bank’s typical C&I borrower.

27

About half of Main Street loans went to

rms with total assets in the range of $5 million to $100 million, very comparable to the frac-

tion of large bank C&I lending to rms of that size. However, 25 percent of large bank C&I

loan volume went to borrowers with total assets exceeding $100 million, whereas Main Street

borrowers of that size represent only 4.3 percent of the loan volume. e right panel shows that

Main Street borrowers also tended to be more leveraged. Almost half of Y-14 borrowers had

leverage between zero times and two times EBITDA. In contrast, almost 90 percent of Main

Street loans went to borrowers with leverage between two times and six times EBITDA. While

most large-bank borrowers tended to have leverage within program limits, the fraction with

leverage exceeding those limits (that is, exceeding six times EBITDA, or with zero or negative

EBITDA) was still signicant (16.9 percent).

For a deeper analysis, we name-matched Main Street borrowers to those also present in the

Y-14 to come up with a set of 149 borrowers that have a loan both in the Y-14 (as of the fourth

quarter of 2019) and through the Main Street program. is matched dataset, though small,

provides a more detailed understanding of the borrower risk prole and terms for loans made

through Main Street compared with loans made outside of Main Street but to the

same borrower.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

Chart 11 compares internal bank ratings for our matched sample of Main Street borrowers

that are also found in the Y-14 (green bars) and borrowers from the Y-14 more generally (blue

bars).

28

e le panel shows that the distribution of ratings for the two groups was roughly

similar before the pandemic. e panel on the right shows that during the pandemic, the distri-

bution of ratings for Main Street borrowers was considerably skewed toward worse credit quality

relative to Y-14 borrowers more generally. Moreover, Chart 12 shows the evolution of ratings aer

origination for Main Street-matched borrowers compared with the rest of Y-14 borrowers. Main

Street borrowers show a signicantly faster deterioration of credit quality according to the banks’

own internal rating systems. As a caveat, note that the internal rating given by the Y-14 bank may

not coincide with the Main Street lender’s rating of that same borrower.

Because the Y-14 has data on loan spreads, we can compare the pricing of loans made

outside Main Street to the uniform pricing (LIBOR + 300) on all Main Street loans.

Table 7 shows (unsurprisingly) that smaller, more leveraged Y-14 rms paid higher spreads

on average prior to the onset of the pandemic, with an interquartile range of 150 to

255 basis points over LIBOR. Spreads were slightly higher in the second quarter of 2020,

when restrictive health policy measures were in eect. Before the pandemic, 13.5 percent of

the bank loans paid a spread over LIBOR higher than 300 basis points, rising to 16.5 percent

in the second quarter of 2020. is rise occurred despite tighter (non-price) lending stan-

dards and the shi to safer borrowers by banks during the spring and summer, as noted

previously. Most Y-14 borrowers were able to secure lending below 300 basis points even

during the crisis, which may explain the initial slow pace of uptake in the Main Street facili-

ties by companies that already had banking relationships with large nancial institutions

(Y-14 lenders). However, the lack of comparable data from smaller lenders that do not le

Y-14 data and the lack of data indicating the number of loan requests denied by lenders

make it dicult to draw conclusions about the impact of Main Street pricing on

program demand.

e prole so far suggests that Main Street borrowers were, on average, riskier than compa-

rable Y-14 borrowers. is is not entirely surprising, as higher-quality borrowers were probably

able to secure credit at a lower rate through their already established relationship with a Y-14

lender. ese conclusions also need to be taken with caution, as the matched sample represents

a small fraction of all Main Street borrowers and a tiny fraction of Y-14 borrowers overall. e

T

Share of Loans by Distance from the Leverage and (Nominal) Loan Size Limits

Leverage Limit Loan Size Limit

Facility At Limit Within 1% Within 5% At Limit Within 1% Within 5%

Expanded loans

3.8 11.5 26.9 3.8 3.8 3.8

New loans 5.7 21.6 31.7 2.1 2.1 2.1

Priority loans 5.9 18.6 29.2 3.8 4.1 4.4

Nonprot loans 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

All facilities 5.8 19.5 30.0 3.2 3.4 3.6

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

Percentage of loans

Borrower asset size (dollars) Borrower leverage (debt-to-EBITDA ratio)

4–62–40–2 <0 or >65–100M2.5–5M1–2.5M<1M >100M

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Percentage of loans

MSLP Y-14Q

C

Main Street and 14Q Borrower Size and Leverage

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and FR Y-14Q (H.1) data.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

AAA AA A BBB BB B CCC CC C D NR AAA AA A BBB BB B CCC CC C D NR

Internal bank rating

Internal bank rating

Percentage of total firms

MSLP borrowers in Y-14

All Y-14 borrowers

Rating as of 2019:Q4 Rating as of 2020:Q3

Percentage of total firms

C

Ratings of MLSP Borrowers in the Y-14 and All Y-14 Borrowers

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and FR Y-14Q (H.1) data .

dierences noted may also reect dierences between the types of borrowers at small and

medium-sized banks (that were most active in Main Street) relative to the types of borrowers

at the large banks covered in the Y-14.

In sum, Main Street borrowers historically paid higher spreads for bank loans and experi-

enced more severe rating downgrades than a comparable reference group (Y-14). Additionally,

the fact that riskier borrowers were able to obtain credit from Main Street facilities can be inter-

preted as consistent with program objectives, since the goal of Main Street was to share risk with

banks during the severe economic downturn caused by the pandemic. In the initial months, bor-

rowing was driven by more highly levered rms, but the scope of lending increased over time to

reach less levered rms. However, leverage ended up being the binding constraint for most of the

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

0

0.1

–0.1

–0.2

–0.3

–0.4

–0.5

0.2

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Quarters since new origination

Average net change in rating

All Y-14 borrowers

MSLP borrowers in Y-14

C

Changes in Credit Risk Ratings for Main Street Borrowers in the Y-14

and All Y-14 Borrowers

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and FR Y-14Q (H.1) data.

borrowers, and this was true across all industries. Finally, the program reached industries and

geographies that were most aected by the economic eects of the pandemic.

4.5 Capital Channel

Main Street loans allowed banks to preserve capital buers, since banks are required to

maintain capital against only their retained (5 percent) share. An implication is that, apart from

risk-sharing, Main Street might have also supported lending through a capital channel whereby

banks benet from originating loans but do not pay the full capital cost of carrying those loans

on their balance sheets.

Chart 13 shows that registered banks tended to have lower capital ratios than nonregistered

banks across all but the smallest size category. ese dierences are statistically signicant for

all but the smallest size groups. Moreover, there is a signicant dierence in capital ratios

between banks that actively participated and those that did not register or registered but were

not active. To investigate the capital channel further, we calculated the aggregate reduction in

required capital facilitated by the Main Street program for all active banks and found it to be a

modest 0.24 percent.

29

e median capital savings across banks is 1.1 percent, the average is

10.2 percent (reecting outliers), and the interquartile range is 0.23 to 6.8 percent. Looking

across bank size groups, the largest percentage reductions in required capital were at smaller

banks. For example, the 43 active banks in the $100 million to $250 million size group save

53 percent on average, with a median saving of 12.8 percent. For the largest banks (more than

$50 billion), the reductions are insignificant.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

T

Loan Spreads Relative to LIBOR on Newly Originated Y-14 Term Loans, by Date and Size-Eligible Borrower Characteristics

2019:Q4 2020:Q2

Percent of

Total Loans

>300 BPS

Percent of

Total Volume

>300 BPS

Percent of

Total Loans

>300 BPS

Percent of

Total Volume

>300 BPSMean Median p25 p75 Mean Median p25 p75

Panel A: Total Assets

Less than $1M 2.47 2.25 1.75 2.78

17.4% 10.5%

2.09 2.14 1.27 2.63

4.3% 3.4%

Between $1M and $2.5M 2.38 2.20 1.75 2.75

11.3% 5.1%

2.75 2.30 2.01 2.93

8.3% 1.3%

Between $2.5M and $5M 2.43 2.27 1.75 2.86

14.1% 15.0%

2.62 2.45 2.00 3.00

23.1% 17.5%

Between $5M and $100M 2.26 2.00 1.64 2.75

15.2% 18.8%

2.44 2.20 1.50 2.75 18.2%

26.6%

Greater than $100M 1.96 1.63 1.36 2.25

9.5% 11.2%

2.22 1.85 1.50 2.50

15.8% 14.3%

Total (Size of Assets) 2.21 2.00 1.50 2.55

13.5% 13.8%

2.35 2.00 1.58 2.75

16.5% 16.4%

Panel B: Leverage

Between 0 and 2 2.16 2.00 1.50 2.60

12.4% 11.3%

2.15 2.00 1.52 2.50

10.8% 13.0%

Between 2 and 4 2.11 1.97 1.50 2.50

10.5% 15.1%

2.48 2.25 1.83 2.98

13.5% 19.0%

Between 4 and 6 2.29 2.25 1.59 2.50

13.6% 10.2%

2.20 1.75 1.50 2.50

17.9% 5.6%

Less than 0 or greater than 6 2.38 2.00 1.60 2.75

19.7% 17.7%

2.57 1.88 1.25 3.50

31.6% 31.2%

Total (Leverage) 2.20 2.00 1.50 2.54

13.4% 13.4%

2.32 2.00 1.50 2.75

16.5% 16.9%

Total (Aggregate) 2.21 2.00 1.50 2.57

13.8% 14.2%

2.30 2.00 1.56 2.61

15.6% 15.9%

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

Note: Size-eligible borrowers are rms with annual revenue up to $5 billion.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

All told, the evidence presented here supports the capital channel. For the largest banks, the

capital channel may have provided an incentive to actively participate, but, in practice, capital

savings were likely modest. In contrast, the capital savings for smaller banks that used the program

more intensely were estimated to be more substantial. Minoiu et al. (2021) also nd evidence in

favor of the capital channel using a more sophisticated multivariate regression framework.

. L L C

With most Main Street loans still outstanding, it is too early to discuss denitive lessons. In

particular, the credit performance of the loans is not yet known. However, now that Main

Street has stopped purchasing loan participations, we attempt to outline a few conclusions and

preliminary lessons learned.

e program helped many borrowers hit hard by the pandemic.

Main Street facilitated more than 1,800 loans to businesses across the nation, representing a

wide range of industries. Volume, at about $17 billion in total, was modest relative to the

maximum size of the program, but it represented a meaningful addition to the ow of bank

credit while the program was in operation, leading Main Street to become the largest credit

0.25

0.20

0.15

0.10

0.05

0

0.30

CET1 capital ratio

Banks by asset size (dollars)

Registered lendersNonregistered lenders

*

*

*

*

*

<100M

100-250M

250-500M

500-750M

750M-1B

1-10B

10-50B

50B-1T

>1T

C

Capital Ratios by Registration Status and Lender Size

Source: Authors’ calculation using MSLP and Call Reports data.

Notes: CET1 is common equity tier 1. Ratios are weighted by riskweighted assets. * denotes statistically

signicant dierence in mean of registered versus unregistered lenders, by asset size, at the 95 percent

condence level.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Economic Policy Review 28, no. 1, June 2022

T M S L P

purchase facility operated by the Federal Reserve.

30

Moreover, many Main Street borrowers

were hit hard by the pandemic, and lenders indicated that they made loans they would not oth-

erwise have made, in line with the goals of the program.

Speed is essential, but setting up a novel loan purchase program takes months.

Loan demand was most pronounced in the spring of 2020, before Main Street was opera-

tional. Looking at the experience across PPP and similar programs abroad, about half to

three-fourths of the uptake occurred by the end of the second quarter of 2020.

31

is pattern

suggests that, in a crisis, speed of execution may need to be prioritized to ensure that support is

available when needed. With Main Street, about four months passed between its announce-

ment and the rst loan purchase, longer than other emergency lending programs of the Federal

Reserve (Morgan and Clampitt 2021).

e length of the rollout time reected the unprecedented nature of the program: e

Federal Reserve had not operated a credit program for small and medium-sized businesses

since the 1940s, and it had never deployed a program to purchase loan participations. So there

was no blueprint, as there was for most other emergency programs rolled out by the Federal

Reserve in response to the pandemic. In addition, the program was operationally complex,

reecting the bespoke nature of the C&I loan market for small and medium-sized businesses,

and necessitated development of many legal agreements and roughly 100 pages of FAQs in

coordination with the Treasury. e program also required the development of

information-technology, credit-risk, and accounting systems to execute the purchase of loan

participations, all of which took time to build. Even with this experience, any future loan par-

ticipation program (or direct lending program) would likely require more time to

operationalize than other market-based emergency lending programs. Finally, policymakers

made several adjustments along the way to rene the program in response to feedback and

evolving conditions. ese changes meant lenders had to incorporate new aspects of the

program in their origination process, which created some delays in underwriting. e changes

also introduced new operational elements that required time to incorporate.