Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 81

CHAPTER 10. CONVERTING SERVICE QUALITY RESEARCH

FINDINGS INTO TRANSIT AGENCY PERFORMANCE

MEASURES

10A. Introduction

The assessment of the determinants of transit service quality has so far focused on the analysis of the

survey that measures transit users' attitudes towards service and derives the implied priorities for transit

service improvements. This analysis has provided useful insights into the factors that make up transit

rider satisfaction which influence mode choice behavior and consequently the observed transit ridership.

The interpretation of the survey results by managerial staff in each of the three transit agencies further

underscores the importance and usefulness of developing and maintaining a market research program

that focuses on customer satisfaction. The robustness and resonance of the survey findings with

management's opinions about the service offered bring to focus the steps that are required to take action

to improve service.

In this chapter we build upon the existing analysis framework by structuring the discussion of

performance measurement from a transit agency's management perspective. Instead of focusing on the

quality of service perceived and expected by the customer, we shift to ways of measuring the quality of

service actually offered by the transit agency. The ability to accurately measure performance allows the

agency both to evaluate its service and to define realistic and measurable goals for service

improvements.

We first discuss the importance of linking transit riders' perspectives to objective disaggregate measures

of transit performance. The different types of analyses that can be conducted are discussed along with

the desired elements of an ongoing data collection plan that focuses on the greatest possible level of

detail.

The performance measures are then identified in a manner that is consistent with customers' experience

by breaking down a transit trip to its individual components and by defining customer expectations of

service. Each of the 46 transit service attributes that were evaluated in the survey is related to the

different components of the transit trip to identify service attributes that share common characteristics.

The 10 most important aspects of service that have been identified through the survey analysis for each

transit agency are then tabulated to identify service attributes that are common to rail and bus transit

systems in each of the three cities. For each of those service attributes we define customers'

expectations and discuss a range of mostly simple performance measures that can be used to measure

the ability of the transit agency to offer service that meets these expectations.

10B. A Transit Agency's Perspective to Transit Performance Measurement

The consumer-oriented approach to transportation service planning is rooted in the assumption that the

observed transit ridership and transit market share are the result of the mode choices made by each

individual commuter. The analysis framework presented in Figure G.1 of Appendix G highlights the

importance of transit level of service, individual traveler characteristics, and communication and

marketing channels on the formation of travelers' perceptions and consequently on their likelihood of

riding transit.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 82

The analysis of the transit rider survey has provided a way of evaluating the link between riders'

perceptions and their overall satisfaction with transit service. A better understanding of transit

customers' needs and wants would allow the transit agency to identify the strengths and weaknesses of

transit service against competing modes and the differences in service for individual routes within the

transit system.

Examples of successful customer-driven approaches to the design and marketing of transit service

quality are documented in a recent study of four European transit systems.

14

The common theme among

these case studies is the intent to demonstrate the transit agency's commitment to service quality and its

sensitivity to customer input by promising a standard of service. This allows customers to evaluate the

ability of the transit agency to provide the level of service to which it was committed.

Among the service improvements that were considered and implemented in the transit systems under

study were the provision of more frequent service, the improvement of reliability, purchase of new

equipment, improved customer relations, electronic payment facilities, and more convenient

connections. A similar review of 40 transit systems in the United States

15

identified increases in transit

ridership that system managers attributed to level of service adjustments, pricing changes, marketing

and information initiatives, enhancement of service coordination, and market segmentation.

Therefore, the next important step in the process from a transit agency perspective is to develop a

strategy of service improvements that is responsive to its customers' expressed needs and wants. In

particular, a transit agency needs to define the type and level of service improvements that need to be

implemented to address weaknesses in service for those service attributes considered most important by

its customers.

The collection of data reflecting riders' perceptions of transit service along with an ongoing program of

transit performance data collection at the transit line and route level by different times of day and days

of the week can be used by a transit agency to:

•

identify existing weaknesses of transit service as reflected in the responses provided by transit

riders and in the performance measures being monitored;

•

set priorities for service improvements by focusing on the aspects of transit service that need to

be addressed first and by identifying the service routes and segments of the market that will be

affected the most;

•

design and implement the identified improvements in transit service; and

•

design an information dissemination program that will properly communicate the improvements

to the riding public.

A recent Transit Cooperative Research Program study

16

approaches the subject of quality of transit

service by adopting a total quality management (TQM) framework for public transportation. To meet

the objectives of increased productivity, reduced costs, and higher ridership through improved rider

satisfaction the study focuses on controllable factors that influence public transit performance.

Recognizing the human service character of public transit, the study focuses on "putting customers first"

by responding to customer expectations and by translating market research into actionable procedures.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 83

An important consideration in the outlined approach is the ability to "manage by fact" and establish a

range of measures that can be used to monitor and evaluate performance. Among the criteria for

developing these performance measures that are included in the report are the:

•

validity of data that are sampled by credible unbiased methods;

•

completeness of data that cover a broad spectrum of aspects of service;

•

policy sensitivity of data that can be used to support managerial decisions;

•

timeliness of data that can be processed, analyzed and interpreted on time;

•

transparency of the data collection process;

•

inexpensive data that may already be collected for another purpose; and

•

ability to interpret data by developing measures that are easy to understand, compare,

and communicate to management and the public.

The ability to make the linkage between riders' statements and measures of transit performance is

therefore instrumental in providing transit management with the means of evaluating alternative service

improvements aimed at enhancing rider satisfaction and transit ridership. Such an evaluation can be

supported by an ongoing data collection effort that captures differences by transit route, time of day,

and day of the week and focuses on a comprehensive list of transit performance indicators. As a result,

the ongoing analysis of the transit performance measures can be used to:

•

provide transit management with a systemwide overview of transit operations for

different transit modes;

•

evaluate transit performance on a route-specific level of detail by focusing on individual

segments of the transit network;

•

monitor changes in transit service over time to identify deteriorating conditions or to

highlight improvements in service in response to service intervention;

•

identify the variation in transit level of transit service by collecting data specific to a

service area, time of day, or day of the week for the service attributes of interest; and

•

guide the development of marketing and communication strategies to inform transit

customers and potential customers of the desirable service features.

10C. Overview of Transit Performance Measures

The collection of transit performance data to support the monitoring, evaluation, and the implementation

of improvements in service presents a challenge to transit agencies. Although transit agencies might be

interested in collecting a wide array of information, the cost of collecting and analyzing a large amount

of transit performance and service quality data presents a constraint to transit agencies.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 84

As a result, the data collection and analysis activities should be concentrated on those aspects of transit

service that are both crucial to their operations and that more accurately reflect the needs and wants of

customers and potential customers. The objective is to match the most important perceptions to specific

aspects of transit service and to identify one or more corresponding service performance indicators.

These measures will differ by transit agency given the different priorities expressed by riders, the

differences in the nature of services offered, and the feasibility and cost of collecting the relevant data.

Travelers' need to travel reflects their need to participate in an activity that is located elsewhere. In this

context, travelers' choices of residential location, workplace, time-of-day of travel, and transportation

mode reflect their desire to minimize the disutility of travel. In the case of transit riders, the disutility of

travel encompasses the whole travel experience from the planning of a transit trip at their point of origin

through the walk egress portion of the trip to get to their final destination. To better understand and

measure the service that a transit rider receives, the total travel experience has been broken into the trip

components and service dimensions shown in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1

Correspondence Between Trip Components and Dimensions of Service

Prior to their trip, transit riders may need to seek information about the most convenient route, departure

time, transfers, and fare to get to his or her destination. Sources for such information include printed

transit route maps and schedules, information provided over the phone by individuals at a passenger

information center, and electronic versions of schedule and fare information. Although such information

is seldom needed for routine trips, it can be of great value to infrequent transit users and non-users who

are unfamiliar with the system.

The level of transit fares is another aspect of transit service that contributes to the disutility of travel and

affects riders' perceptions of transit's attractiveness. Although transit fares are often lower than the

corresponding operating, maintenance, and parking costs of private modes, fare levels can have an

adverse impact on the price-sensitive frequent traveler segment of the travel market. The availability of

different types of fares, such as monthly passes, ten-ride discount tickets, and electronic fare media with

value storage capabilities, and fare restrictions increase travelers' flexibility to choose an optimal

payment strategy that fits their own travel patterns.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 85

The travel components of a transit trip include:

•

the access to the transit station/bus stop,

•

the time spent waiting for transit service,

•

the in-vehicle experience of riding transit,

•

potential transfer(s) to different transit services, and

•

the egress to the final destination.

The access and egress walk components of the trip are only in part linked to the everyday operations of

a transit system. Although the number, location, and spacing of stations and stops and the adjacent land-

use development may affect transit service considerably, they are primarily linked to the original design

of the service. On the other hand, riders' perceptions of the accessibility of rail stations and bus stops

can be positively influenced by interventions such as kiss-and-ride facilities, availability of long-term

station parking, sidewalk maintenance, availability of well-lit access paths, and maintenance programs

for stairs, escalators, and elevators leading to platforms.

The time waiting at the station or stop, the in-vehicle component of the trip, and the transfer to another

transit route are all characterized by:

•

traditional measures of transit service such as wait time, travel time, and service

reliability;

•

the station/stop and vehicle environments that the transit riders experience; and

•

the availability and quality of information available to riders at rail stations, bus stops,

and en route.

Table 10.2 provides a link between the components of a transit trip, the dimensions of transit service,

and the 46 attributes of service that were used in the transit rider survey. These linkages illustrate both

the depth of the rider survey and the potential range of corresponding measures of performance. The list

of candidate performance measures can be extended even further considering that a variety of measures

can be defined for attributes like service reliability depending on the nature of service. A range of

surrogate measures may be needed to properly reflect riders' feelings of security at stations, stops, and

on-board transit vehicles.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 86

Table 10.2

Ratings of Service By Trip Component and Service Dimension

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 87

Table 10.2

Ratings of Service By Trip Component and Service Dimension

(continued)

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 88

In the remainder of this chapter, we focus on the 10 most important determinants of service for each of

the transit systems under study. Table 10.3 summarizes the findings and highlights the similarities and

differences across the three systems and the two CTA lines that were examined.

The two service attributes that emerged as the most important across all routes sampled were the

frequency and reliability of transit service, both of which reflect important policy-sensitive aspects of

transit service design. The third service attribute that was mentioned by riders in all three transit

systems but only in one of the CTA lines was the freedom from the nuisance behaviors of others, an

important but subtle and difficult to quantify service dimension. The remaining "top ten" service

attributes were split between those that were perceived as important by riders in Chicago and

Lynchburg and those that were mentioned by riders of the Sun Tran service who mostly focused on

frequency-related issues.

In sections 10D to 10M, we focus the discussion on the individual service dimensions and the

corresponding measures.

10D. Frequency of Transit Service

Based on the customer satisfaction surveys, frequency of transit service is among the most important

elements of transit service. Frequency was at the top of riders' lists for each of the three agencies where

transit riders were surveyed.

Frequency has two interpretations for transit riders. First, it refers to the hours of operation of transit

services. Many routes and services are available only during weekday peak periods, and sometimes

riders need to make trips served by the routes and services on weekends and on off-peak times of

weekdays. Limitations in transit service hours obviously affect travelers who need to travel during the

hours or days when there is no service. In addition, some potential transit riders choose not to use transit

services because the particular services are unavailable for their anticipated return trips or because they

cannot be certain about the time of their return trips and need to be certain that they do not get stranded.

Limitations in transit services and routes are almost always necessary for reasons of cost-effectiveness.

The low ridership levels that would be generated on many routes simply cannot justify the cost of

providing services at these times. However, from the customers' point of view, having service at all

hours and on all days is desirable. A straightforward customer-oriented measure of this aspect of service

frequency is the hours per day and days per week that transit service is available for each route.

The second interpretation that customers have of service frequency is how often buses and trains come

when the route is being operated. This can be measured most directly by the wait time that customers

experience. When service headways (the time between successive trains or buses) are relatively short,

wait time can be assumed to be one-half the headway. As headways get longer and people begin to

arrive for specific scheduled trains or buses, wait times level out. However, the general inconvenience

of having only a few buses or trains from which to choose continues to increase as headways are

increased. Since headways and wait times usually vary by time of day and between weekdays and

weekends, measuring them for customers' actual time of travel is likely to greatly improve the

relationship between customer ratings and the service measures. Therefore, bus and train headways can

be used as straightforward measures of service convenience reflecting the frequency of service by route,

time of day, and day of the week.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 89

Table 10.3

Similarities and Differences Across Transit Systems

In addition, customers making trips that require one or more transfers are likely to view the frequency

of the second and subsequent routes or services as especially important because those frequencies will

dictate the amount of time that the customers can expect to spend making transfers. Transfer time is

usually considered to be particularly onerous by transit riders. For this reason, it is recommended that

measures of the time spent transferring are developed at least for the most important origin-destination

pairs in the area served by transit.

The frequency of service is the primary determinant of actual customer wait times and one of the most

important determinants of their level of satisfaction with transit service delivery. Closely related to

service frequency (in customers' minds) is service reliability — the ability to stay on the expected

schedules. The next section discusses this aspect of service.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 90

10E. Reliability of Transit Service

The large number of transit agencies reporting measures of service reliability reflects the importance of

providing reliable and predictable service both from a transit operations and a transit rider's perspective.

Furthermore, the variety of definitions of on-time reliability reflects the different perspectives of transit

agencies in measuring this service attribute (Appendix G).

It is highly advantageous both to operators and customers to maintain consistent and predictable service

on transit routes and lines. For operators, a lack of regularity and uniformity leads to the inefficient use

of resources (with some vehicles overloaded while others are underutilized), increased costs, and lower

systemwide productivity. Two-thirds of transit operators view maintaining reliability as very important

element of transit service delivery.

17

For customers, non-uniform and inconsistent service increases the

level of uncertainty and uneasiness they feel at stops and stations, exacerbates crowding on vehicles and

at station and stop waiting areas, and makes transfers more difficult and time-consuming.

The reliability of transit service is most often measured by on-time performance, which reflects how

closely the delivery of transit service matches the published schedule. Specific measures of on-time

performance include:

•

percent of trains or buses reaching pre-specified points on time in different time periods,

where on time is defined as arriving in a pre-specified time window;

•

variance in travel times between two points;

•

average minutes of bus or train delay measured at specific locations; and

•

regularity of service (schedule adherence) at specific locations.

There are certain dimensions to on-time performance that make its measurement complicated. The

objective of a transit rider is to arrive at his/her destination on-time, regardless of any en-route schedule

variations. It is possible for trains or buses to be badly off schedule, and still get a passenger to the

destination at the desired time. At the same time, transit riders are interested in minimizing the time

spent waiting for vehicles since it is a component of travel time that is perceived as more onerous than

invehicle travel time. It is also possible for the on-time performance measures to poorly conform to

riders' experiences in this regard.

In analyzing on-time performance measures, it is often difficult to compare different types of services

and different types of routes. Most on-time performance measures will have disparate ranges for

different transit modes because the modes are affected by different exogenous factors. For instance, it is

quite difficult to meaningfully compare the on-time performance of a commuter rail line with that of an

urban bus because the bus is more vulnerable to weather problems and highway incidents. Riders

recognize the inherent reliability differences, and usually customer satisfaction levels will be based on

different levels of expectation.

Even within mode comparisons are difficult. To facilitate the assessment of on-time performance a

distinction needs to be made between frequent transit service that is offered in small regular intervals

and infrequent service that is provided according to a published schedule. In addition, the length of the

route is likely to skew on-time performance results.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 91

Because of these difficulties in comparing on-time performance for different services, it is also difficult

to develop meaningful systemwide on-time performance measures. The most effective measures are

obtained for specific services or small groups of services. They are best analyzed through comparisons

over time as opposed to comparisons with each other.

There are also a number of operations measures that can be used as a surrogate measure for transit

reliability. These measures are supply-driven and reflect the ability of the transit agency to provide the

required amount of service rather than the quality of service. These measures could be used as surrogate

indicators in cases where there is no option for additional data collection and analysis and include:

•

the frequency of service breakdowns which is usually expressed as the average number

of miles between breakdowns including a vehicle failure, road call, or service

interruption, and

•

vehicle availability which measures the number of vehicles that are available for service

suggesting that the likelihood that service will be delivered as scheduled decreases with

fewer available vehicles.

10F. Explanations and Announcement of Delays

For transit riders, one of the most difficult aspects of delays in service is the associated uncertainty

about what has happened and how long they will need to wait for a train or bus. Riders are much more

accommodating of delays when they are provided with information regarding the reasons for the delay

and the likely length of the delay. The information allows riders to better plan ahead, and at a broader

level, it helps to make riders feel like the transit system recognizes that the delays are a problem and

that the transit workers are actively working on the problems.

A number of transit systems try to provide delay information to riders through on-board and station

public address systems. In addition, some agencies have experimented with providing electronic map

information on-board vehicles, at stations, and at bus stops. Automated Vehicle Location (AVL)

systems allow operators to post real-time or close-to-real-time information for passengers.

In Europe, many transit agencies pride themselves on passenger amenities, especially the provision of

customer information.

18

In London, where uncertainty about delays is among the most common sources

of rider dissatisfaction, arrival time and destination information is beaconed to transit stops. In Stuttgart,

the transit agency makes use of their AVL-based transit fleet management system to provide traveler

information at terminal kiosks and through an in vehicle route guidance system.

19

In addition to the more high-tech communications devices, transit agencies also provide likely-delay

information to passengers through newsletters, flyers, and telephone customer service representatives.

A number of measures can be used to gauge how well delay information is being disseminated to riders,

including:

•

availability of on-board and station public address systems;

•

availability of other electronic real-time displays;

•

frequency and clarity of announcements and messages;

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 92

•

percentage of significant delays for which correct information was provided to

passengers on-board affected vehicles;

•

percentage of significant delays for which correct information was provided to

passengers waiting at affected stations or bus stops; and

•

percentage of foreseeable delays (construction, maintenance, weather-related) of which

customers are made aware.

Transit agencies also commonly measure the quality of their customer communications that are not

directly related to delays. Some agencies reported measures that are aimed at quantifying each of the

different communication efforts that transit agencies carry out. Examples of such measures include the

percentage of calls by the public answered within 90 seconds; the number of service requests received

by the public; and the number of calls received asking for transit-related information.

The number of complaints expressed by transit passengers is used by some agencies as a surrogate of

service performance and is often reported on a monthly basis. This measure presents an effort by the

transit agencies to be responsive to their clients' needs and wants. Agencies collect and analyze

complaints by type (e.g. facilities, operators) and by mode and normalize the frequency of complaints

by dividing by the number of transit riders or the number of transit service miles provided.

10G. Crowding On-board Trains and Buses

A common complaint about public transit systems in large cities is that trains and buses are often too

crowded. Generally, the most common reasons that vehicles get overcrowded is that there is a service

frequency or reliability problem, so the fact that crowding is of importance to survey respondents

reinforces the importance of measuring frequency and reliability.

The crowding on-board trains and buses is an easily quantifiable measure through the calculation of

various load factors. The load factors reflect the discrepancy between the available transit capacity and

the corresponding transit ridership. Load factors can be expressed as the number of passengers on a

vehicle divided by the vehicle's design capacity, the number of passengers divided by the crush capacity

of the vehicle, or the number of passengers on a vehicle divided by the number of available seats.

Passenger loading estimates are best obtained through direct observation of vehicles passing

prespecified points (usually the maximum loading points).

10H. Behavior of Other Riders

Security concerns are an important element of customer satisfaction. In the surveys, these concerns

manifested themselves as concerns about the behavior of other riders. If transit customers perceive that

the nuisance behavior of other riders is tolerated, then their level of concern about their personal

security will increase. Where there is a high level of so-called "quality-of-life" crimes and rules

violations, there is more of a feeling that there is no one in charge of the system.

One way to measure the level of nuisance behavior is to track police arrest and citation records. The

weakness of this approach is that it is confounded by changes in the level of effort by police to enforce

system rules and by the general presence of police within the system. The presence of police officers

within the system will tend to shift crimes and incidents to different places in the system, so measured

improvements may not accurately reflect riders' experiences.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 93

Some transit agencies have tried to obtain measurements on the amount of nuisance behavior by

discretely sending observers into the system to collect information on fare evasion and other minor

crimes and rules violations. OC Transpo in Ottawa has developed Transecure, a neighborhood watch

program within its system to allow police to locate and respond to bad behavior or suspicious activities.

Information from such a program is likely to be better than arrest or citation data because those

observing the bad behavior will not be recognized as police. If a system is able to spend enough

resources to obtain a statistically significant sample of time periods and locations, then changes over

time can be monitored and compared to survey results.

10I. Smoothness of the Ride

The smoothness of the ride and the stops is an indicator of rider comfort that is not easily quantified.

Smoothness can be measured on a subjective basis by having transit staff ride transit vehicles that are in

operation and to rate the ride quality. Alternatively, scientific instruments could be used to measure the

forces being experienced by riders as the vehicles traverse their routes.

These measures are more difficult to use and interpret than other measures discussed in this chapter. A

number of factors contribute to the relative smoothness of the transit ride, including:

•

the condition of the railroad track or the roadway;

•

the operating condition of the rail or bus vehicles;

•

the speed of the bus and the composition of the roadway traffic; and

•

the experience of the rail and bus operator.

Riders' dissatisfaction about the smoothness of the trip can be caused by problems related to any or all

of these factors. Therefore, developing direct measures to quantify smoothness will not necessarily help

a transit operator determine whether or how to make improvements to the system to improve customer

satisfaction. Given this problem, it is probably unlikely that smoothness measures would be helpful to

transit operators unless they were specifically designed to isolate the different factors that go into ride

smoothness.

10J. Cost Effectiveness, Affordability, and Value

The cost of travel by transit is almost always subsidized by local, state and/or national governments in

an effort to promote transit use, alleviate roadway congestion, and improve the mobility of the transit-

dependent segments of the population. However, in almost all cases the users are required to pay fares

to use transit systems. Fare levels affect customer satisfaction and ridership.

For any given customer, the measure that is directly related to the questions of cost effectiveness,

affordability, and value is the cost per transit ride. Because most systems offer some type of discounted

multi-ticket fare as an option to a one-way ticket, the cost per ride may be different depending on the

ticket type that individuals use. If monthly passes or another type of unlimited ride ticket types are

available, the cost per ride will also vary based on the amount of system usage.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 94

In most cases, the average cost per ride that individuals pay will vary by traveler market segment

because ticket type choice will vary by market segment. Developing separate measures for different

traveler market segments may be the best way to relate customer satisfaction with transit fare levels.

10K. Availability of Seats

Availability of seats is a special case of crowding on transit vehicles that is discussed above under

section 10G. One can measure the ratio of the number of people on a vehicle to the number of seats on a

vehicle to quantify the availability of seats.

10L. Frequency of Delays due to Repairs/Emergencies

The paramount importance of delays and reliability to transit passengers was discussed above under

section 10E. However, the analysis of the survey results suggests that riders do not consider all delays

equally. Delays that are due to breakdowns or accidents are particularly irksome to transit riders

because they are to some extent preventable. Weather-related delays, while certainly viewed negatively,

have a lesser impact than delays due to bus or train mechanical problems.

Transit agencies commonly quantify the reliability of transit vehicles with the measures mean distance

between failures (MDBF) or average failures per vehicle. Operations staff use these measures to detect

problems with vehicles of one type or another, so separate values are calculated for each vehicle type in

the system. The primary advantage of these measures is that most agencies collect this information on a

continuing basis anyway, so no additional data collection is necessary.

The primary disadvantage of these measures is that they are not collected for the purpose of measuring

the quality of customer service delivery. To relate the measure to particular riders' customer satisfaction,

it is sometimes necessary to obtain detailed information about the vehicle types being used on specific

routes and to calculate route-specific or service type-specific weighted averages of the mean distance

between failures. In addition, the type and circumstances of failures will have a large impact on

customers' perceptions and this information is not necessarily captured by the maintenance measures. It

would probably be quite useful to categorize the specific problems causing the breakdowns, whether or

not passengers were able to be rerouted once a vehicle broke down, and the response time to address the

incident.

The frequency of transit-related accidents was another category of measures cited by many agencies.

Some of the agencies normalize the number of accidents per miles of service while other agencies break

out accidents by type including passenger accidents, employee accidents, preventable accidents, vehicle

accidents, etc. Measures of accident incidence are usually reported on a monthly and a mode-specific

basis.

10M. Passenger Environment On-board Vehicles and at Stations/Stops

The general environment through which passengers travel on transit has a great deal to do with their

level of satisfaction. However, it is difficult to develop a consistent and objective approach to

measuring the quality of the passenger environment.

Some agencies employ professionals whose responsibilities include monitoring the system from the

customer's point-of-view. These individuals are trained to consistently rate stations and vehicles

according to specific objective measures or on qualitative pre-set scales. This information is then

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 95

aggregated and tracked over time to measure how the passenger environment changes. The information

is shared with the operations managers who are responsible for the specific elements being evaluated, so

that they are able to evaluate the quality of their departments' service delivery.

New York City Transit uses its passenger environment survey to obtain data on a wide range of subway

categories

20

, including:

Station

•

lighting at different locations within stations;

•

public address system clarity;

•

condition of escalators and elevators;

•

presence and readability of system maps in the stations;

•

amount of litter on the platforms and track bed;

•

amount of stains and spills on the platforms;

•

amount of graffiti in the station;

•

quality of the station signage;

•

condition of public phones;

•

condition of turnstiles, gates, token vending machines;

•

courtesy and appearance of token booth personnel;

•

availability of maps and system information in the station.

Subway Cars

•

exterior graffiti;

•

condition of doors;

•

lighting;

•

air conditioning, fans, car temperature;

•

clarity of station stop and safety announcements;

•

amount of litter, spills, and stains in the car and;

•

presence of graffitied, scratched, and cracked windows;

•

appearance of guards.

Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) performs a similar quarterly review of its facilities.

21

The BART

survey includes 31 specific measures that are organized around organizational areas of responsibility.

The BART measures include:

Facilities Management

•

Station Patio Cleanliness

•

Parking Lot Cleanliness

•

Landscape Appearance

Station Operations

•

Station Cleanliness

•

Station Graffiti

•

Restroom Cleanliness

•

Advertisements in Stations

•

Brochures in Kiosks

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 96

Station Agents

•

Agent Available or Sign in Place

•

Agent in Uniform

•

Agent wearing Name Badge

BART Police

•

BART Police Personnel in Stations

•

BART Police Personnel in Parking Lots/Garages

•

BART Police Personnel on Trains

Public Address Announcements

•

P.A. Arrival Announcements

•

P.A. Transfer Announcements

•

P.A. Destination Announcements

Rolling Stock

•

Train Exterior Graffiti

•

Train Doors Operative

•

Train Interior Graffiti

•

Train Interior Cleanliness

•

Train Window Etching

•

Temperature on Trains

•

Advertisements on Trains

Elevator/Escalator Availability

•

Station Elevator Availability

•

Escalator Availability - Street

•

Escalator Availability - Platform

Automatic Fare Collection Availability

•

Fare Gate Availability

•

Ticket vending Machine Availability

On-Time Performance

•

Train on Time

•

Customer on Time

A number of the passenger environment measures are subjective and qualitative. The careful training of

observers and tests to ensure that ratings are being made consistently are essential for the data collection

effort to be effective. However, despite the difficulty in establishing and monitoring the data collection

effort, passenger environment surveys are probably the best way for transit agencies to understand their

systems from customers' perspectives.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 97

ENDNOTES

14

European Conference of Ministers of Transport, Round Table 92:

Marketing and

Service Quality in Public Transport,

Organization for Economic Cooperation,

Paris, France, 1993.

15

Transit Cooperative Research Program, Research Results Digest, Number 4,

Transit Ridership Initiative

, Transportation Research Board, National Research

Council, Washington D.C., February 1995.

16

Transit Cooperative Research Program, Research Results Digest, Number 3,

Total

Quality Management in Public Transportation

, Transportation Research Board,

National Research Council, Washington D.C., October 1994.

17

National Cooperative Transit Research & Development Program, Synthesis 15,

Supervision Strategies for Improved Reliability of Bus Routes

, Transportation

Research Board, National Research Council, Washington D.C., September 1991.

18

Transit Cooperative Research Program, Research Results Digest, Number 22,

International Transit Studies Program - Report on 1996 Missions

, Transportation

Research Board, National Research Council, Washington D.C., October 1997.

19

Transit Cooperative Research Program, Research Results Digest, Number 20,

International Transit Studies Program - Report on the First Three Missions

,

Transportation Research Board, National Research Council, Washington D.C.,

May 1997.

20

Charles River Associates Incorporated,

Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Comprehensive Line Improvement Study,

March 1994.

21

Aaron Weinstein and Rhonda Albom,

Securing Objective and Reliable Data on

the Quality of the Passenger Environment — The Redesign of BART's Passenger

Environment Measurement System,

presented at the 77

th

Annual Meeting of the

Transportation Research Board (January 1998).

This page left intentionally blank.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 99

CHAPTER 11. AN OVERVIEW OF DATA COLLECTION AND

ANALYSIS METHODS

In this chapter we outline the broadly defined desirable features of a data collection and analysis plan.

The differences in the level of service offered and the nature of the markets served by each transit

system do not allow the development of a unique set of specific data collection and analysis procedures.

Furthermore, the identification of a different set of priorities for service improvements by riders of

different transit systems further stresses the need for a customized approach to data collection and

analysis.

The broadly defined principles guiding the data collection and analysis approach are presented in two

sections. We first outline the elements of a data collection plan that minimizes biases and aggregation

errors, provides data that are internally consistent and relevant from a passenger perspective, and

accounts for the statistical significance of the collected data at a reasonable cost. We conclude our

discussion by outlining different ways of analyzing the collected transit performance data and

summarizing the results.

11A. Principles of Data Collection

In order to gauge the quality of customer service by measuring specific service attributes, it is essential

that the transit agency consider the quality of the data that are being collected and the appropriateness of

the chosen data collection method(s). As noted in the previous chapter, data on different service

measures can be obtained by a variety of manual and automatic methods.

The manual methods include observation of service attributes by field inspectors, by field worker data

collection staff, and by "mystery riders," transit agency staff or contractors who ride the system as

customers would without letting transit workers know who they are or where they will be. In many

cases, inspectors assemble the data that would be used in evaluating service attributes for their own

purposes, thus the added cost of using this information for customer service evaluation is low. Special

data collection procedures by transit staff and mystery riders can be used to obtain the other service

measures.

Some transit service measures can be recorded automatically. For instance, systems that use buses

equipped with AVL systems can automatically collect data on vehicle headway, on-time performance,

and ridership allowing us to calculate a multitude of performance measures discussed in this report.

Furthermore, the implementation of an AVL system allows the development of passenger information

systems that can be used to provide estimated time of arrival to waiting passengers, display vehicles on

an electronic map at a bus stop or rail station, and provide en route information to transit passengers.

A review of the current status of AVL bus transit systems in the U.S. along with a detailed technical

review of different AVL architectures and technologies is presented in a recent TCRP report.

22

The

advantage of such a data collection mechanism is that a variety of accurate performance data can be

automatically collected at the route level by time of day and day of the week. At the same time, the

challenge with these data is the ability to properly sample, organize, and analyze the information that is

gathered in order to obtain the meaningful measures that are being sought.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 100

Planners need to be aware that there are several potential problems with any given measure that can

reduce its usefulness in analyzing service delivery. Among the potential problems are:

•

bias;

•

aggregation error;

•

inconsistency;

•

irrelevancy form the passenger perspective;

•

insignificance; and

•

cost to assemble and analyze data.

These issues are discussed below.

Bias.

In this context, bias refers to a set of systematic errors that tend to overstate or understate the

performance of the system for a specific measure. Performance measures should be as free from bias as

possible. Examples of biased measures include data from a non-representative sample of routes or

services and data assembled with methods that cause the observed situation to be different than that

experienced by riders. If an agency were to assess the reliability of its bus system by measuring on-time

performance only on routes of one type, say routes that serve major downtown stops, erroneous

conclusions about the system as a whole are likely. Similarly, if an agency were to evaluate aspects of

customer service by having uniformed inspectors observe transit employees' interactions with

customers, then it is likely the results of such an evaluation would not reflect conditions when

inspectors were not present.

Aggregation Error.

If service measures are collected at too gross a level, important nuances of

customer service delivery will be lost. For instance, if on-time performance was calculated on a

systemwide basis and was used to gauge customer satisfaction with on-time reliability, it is possible that

the measure is masking significant differences between different routes and lines. If a small number of

routes have significantly poorer performance than the system as a whole, their effect on the objective

service measures will understate the negative effect that they have on customer satisfaction.

Inconsistency.

Because the most effective way to analyze service measures is to analyze changes over

time and differences between different routes and services, the measures of service delivery and the

scales used to record them should be consistent over time, from location to location, and from one

evaluator to another. This is particularly important for the more subjective measures such as cleanliness.

If inspectors or members of the field staff are employed to rate stations or vehicles on cleanliness, each

one of them should have consistent ratings. In addition, the ratings should not vary with time. This is

sometimes difficult because changes in the level-of-acceptability of certain conditions are likely to occur

over time, particularly if a system invests in improvements in the specific aspect of service under study.

When agencies employ staff to make subjective measurements of service measures, the following steps

should be taken whenever possible:

•

develop objective measures whenever possible (e.g., use a thermometer to measure the

temperature on vehicles, rather than a field worker rating of temperature);

•

train the field workers extensively, employing actual field evaluations, to ensure that

different fieldworkers rate things consistently;

•

test inter-rater variations in ratings to ensure that raters remain consistent (sometimes the

best way to test this is to have raters have some overlapping responsibilities).

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 101

Irrelevancy to Customers.

Often, it is possible to use already-collected measures of performance to

evaluate service delivery to customers. Of course, whenever this is possible it is desirable from an

efficiency point-of-view. However, because these data are collected for purposes other than the

evaluation of customer service delivery, planners need to assess the relevancy of the measure to

customers. For example, information on on-time performance is commonly collected at train and bus

terminals. In many cases where ridership is highly directional or is skewed to be on only part of the

route or line, on-time performance at a particular terminal point may be largely irrelevant to customers.

If a morning peak train runs close to schedule going into the CBD but then is delayed after it has made

it past the CBD, the delay is irrelevant to the large majority of riders. In this case, a better on-time

performance measure would be one that was collected at a CBD station.

Insignificance.

In order to draw valid conclusions from the assessment of service measures, an agency

needs to ensure that enough data are sampled and assembled to make the conclusions statistically

significant. An agency should first define finite elements of its system, such as stations, buses in a

particular time period, or buses on a particular route. As a second step, statistical sampling methods

should be applied to determine how many of the elements need to be studied or observed in order to

make statistically valid conclusions. If information is assembled in an ad hoc way, it is possible that

variations in service quality will never be accurately observed.

Cost to Assemble Data.

Finally, as for any primary data collection effort, the costs of getting particular

types of data need to be considered and traded-off with the benefits of the data that would be collected.

In general, the errors introduced by the potential problems described above can be reduced somewhat

through more and better data collection efforts that almost always increase the cost of data collection.

Although it is difficult to determine the cost-effectiveness of data collection efforts, the agency should

set as a priority maintaining data on the measures associated with the three or four of the most important

aspects of service from the customer's point-of-view.

For those aspects of service that are perceived as less important, an agency should probably obtain data

through less rigorous methods, perhaps using less accurate measures that are already collected or are

easily collected. In developing cost estimates for service data collection, an agency should seriously

consider the added benefits of maintaining the data assembly over time, rather than on a one-time basis.

In addition, an agency should consider collecting detailed high-quality data for specific elements of the

system, rather than the system as a whole.

11B. Approaches to the Analysis of Performance Data

The ultimate objective of the analysis of the transit performance measures is to facilitate a focused and

accurate assessment of any existing weaknesses in service and the measures that need to be taken in

response to these performance problems. To provide transit management with a means of identifying

the strengths and weaknesses of transit service and supporting its evaluation the analysis should, as

stated earlier:

•

provide transit management with a systemwide overview of transit operations for different

transit modes;

•

evaluate transit performance on a route-specific level of detail by focusing on individual

segments of the transit network;

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 102

•

monitor changes in transit service over time to identify deteriorating conditions or to

highlight improvements in service in response to service intervention;

•

identify the variation in transit level of transit service by collecting data specific to a

service area, time of day, or day of the week for the service attributes of interest; and

•

guide the development of marketing and communication strategies to inform transit

customers and potential customers of the desirable service features.

To provide transit management with these insights, we demonstrate four different broadly defined ways

in which the collected transit performance data can be analyzed. We use as a hypothetical example a

measure of bus on-time reliability as reflected in the percentage of buses arriving late at the central

business district bus terminal. We have also assumed that comparable data on on-time performance are

available for four different points in time between 1979 and 1997. The figures that are presented and

discussed allow us to:

•

measure bus performance at a systemwide level and compare it with differences in

performance at the bus route level;

•

identify trends in systemwide and route-specific levels of bus performance over time;

•

assess differences in the perceptions of different market segments including bus riders and

nonusers, frequent and infrequent transit riders, riders using different routes, and riders

with different socioeconomic characteristics; and

•

compare riders' perceptions to measures of transit service to identify whether the strengths

and weaknesses perceived by riders actually reflect the level of transit service that is

currently provided.

These layers of analysis correspond to an ever-increasing level of complexity. It is therefore not

expected that all layers of analysis will be employed by each agency to study each of the important

aspects of service. Furthermore, the more complex analyses presented below also require a wealth of

data that may be maintained only for a few important measures of service.

I. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Transit Performance

The analysis of on-time transit reliability at a single point in time can provide a snapshot of transit

performance both at a systemwide and at a transit route level. Although the systemwide measure can be

a useful indicator of overall performance especially when monitored over time, it is also important to

focus on the performance over sections of the transit system to identify potential differences by line.

Figure 11.1 presents a hypothetical example where the aggregation at the bus system level without any

attention to the disaggregate route level of detail would mask important differences in performance by

bus route. As shown in Figure 11.1, the overall on-time performance for the transit bus system is

reflected on a satisfactory systemwide average of 87% of buses arriving within a specified time interval.

However, a more detailed analysis of on-time performance at the route level suggests that there are

considerable differences in route performance that would ordinarily be masked by focusing solely on

the systemwide average measure.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 103

Figure 11.1

Comparative Route Analysis

Therefore, on the basis of such a cross-sectional analysis of the bus system, the analysis would conclude

that:

•

the overall level of bus on-time performance is satisfactory, but

•

there are important differences by route which suggest that:

•

route E experiences a significant amount of buses that are late and should be

identified as a priority for service improvements;

•

route B operates at an acceptable better-than-average level but should be monitored to

prevent any deterioration in service; and

•

route A should be used as a benchmark of on-time performance for the whole

system.

II. Historical Analysis of Transit Performance

An additional layer of analysis can be provided by the study of systemwide and route specific on-time

performance over time. Such an analysis can be used to identify trends of progress and deterioration in

transit service that are not provided by the snapshot provided by the cross-sectional analysis.

A review of the hypothetical historical patterns of on-time performance for the same system shown in

Figure 11.2 uncovers some important trends that could help explain the differences in on-time reliability

across the system. In particular, it appears that the systemwide trend of deteriorating on-time

% of Trains Late

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 104

performance has been reversed in the past three years. However, there are some important underlying

differences among the three routes suggesting that:

•

the current poor on-time performance for route E is the result of an ongoing deterioration in

transit level of service and reflects problems that date back more than a decade and that

have gradually affected transit service;

•

route B has enjoyed improved on-time reliability over the past three years reflecting the

systemwide trend; and

•

route A has maintained an excellent level of service over time.

Thus, despite the improvement in systemwide service performance the identified route-specific patterns

of stability, progress, and deterioration in service performance over time can be used to support route-

specific interventions.

Figure 11.2

Performance Monitoring Over Time

III. Riders' Attitudes and Transit Performance

The third layer of analysis that supplements the cross-sectional and historical analysis of transit

performance data focuses on the joint analysis of transit riders' attitudes and transit performance. Two

general types of analysis can be accommodated within this context. First, an analysis of the differences

in attitudes across segments of the transit market can help identify opportunities for marketing to

different groups of riders. Second, a comparison of attitudes and transit performance can help identify

riders' misperceptions and identify opportunities for communicating service improvements to transit

riders.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 105

Figure 11.3 illustrates the differences in perceptions among users and nonusers as reflected on their

ratings of five different aspects of transit service. A rating scale of 0 to 10 was used with higher values

corresponding to more positive perceptions of transit service. As shown in Figure 11.3, current transit

riders rate all aspects of transit service, with the exception of safety while using the system, higher than

nonusers do. The pattern of differences in the respondents' ratings suggests that:

•

the transit agency needs to allocate resources to enhance riders' perception of feeling safe and

secure while riding the transit system;

•

the perception of safety and security among nonusers does not appear to be the primary

reason for not using the transit system;

•

the gap between users' and nonusers' perceptions is greater for "frequency of transit service"

and "transit on-time performance" which are perceived rather positively by current riders of

the transit system; and

•

there are considerable opportunities to improve nonusers' perceptions of transit service along

most of the dimensions of transit service as part of an effort to increase transit ridership.

Although the example of such an analysis is presented at the systemwide level for transit riders and

nonusers it can be further expanded along two additional dimensions. First, route-specific analyses can

be conducted for routes and groups of routes that are of greatest interest to the transit authority. Second,

comparisons of attitudes among market segments can be expanded to account for differences among

frequent and infrequent riders, male and female riders, and riders with different degrees of captivity to

transit. These analyses can provide insight into the appeal of different transit routes to distinct segments

of the market.

Finally, it is possible that the availability of transit performance and survey data at similar points in time

allow comparisons between riders' perceptions and transit performance measures. Such comparisons are

again most meaningful if they can be repeated over time and across different routes of the system. The

availability of such data supports a fourth layer of analysis that can be used to relate patterns of change

in transit performance to changes in riders' perceptions.

The comparisons that can be made allow us to identify cases where service improvements have a

positive impact on riders' perceptions and cases where despite improvements in transit service transit

riders' perceptions continue to remain rather low.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 106

Figure 11.3

Perceptions of Users and Nonusers for Route A

Figure 11.4 offers an example of comparisons that can be made using historical attitudinal data and

corresponding performance data at the route level to identify the extent to which there is a correlation

between traveler perceptions and transit performance.

The bar chart and the left hand axis illustrates the average ratings given by riders of routes A and E on a

scale of 0 to 10 with higher values corresponding to more positive perceptions of service. The line

graph and the right hand axis correspond to the on-time performance reflecting the percentage of buses

arriving late for the A and B routes at the three study years.

The comparisons that can be made suggest that:

•

riders' ratings for route E are consistently lower than those by riders of route A properly

reflecting the historically better on-time performance of route A;

•

route E riders' ratings of the transit service have dropped over time in a manner that is

consistent with the deteriorating performance of route E;

•

the gap between the ratings for route A and E has widened over time again properly

corresponding to the widening gap in the level of transit on-time performance offered by

each route; and

•

the drop over time in riders' ratings of route A is not consistent with the high level of on-

time performance for route A.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 107

These observations suggest that riders' evaluations are generally consistent with the level of service that

is provided. The need to improve the on-time performance along route E is supported both by the

existing low level of on-time reliability on that route as well as the low ratings provided by riders. It is

expected that the implementation of such service improvements will enhance route E riders' perceptions

and bring them closer to the ratings provided by riders on route A.

Finally, the apparent inconsistency between the historically high level of on-time reliability for route A

and the steady or decreasing ratings by route A riders suggests that other aspects of the performance for

this route need to be examined more closely. It is possible that due to deterioration in other service

characteristics for route A, riders provide ratings for on-time reliability that are lower than expected.

However, if there are no apparent weaknesses in other aspects of route A service, the implementation of

a marketing campaign aimed at riders of route A may be considered to stress the existing high level of

service.

Figure 11.4

Performance Measure versus Riders' Perceptions

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 108

ENDNOTES

22

Transit Cooperative Research Program, Synthesis 24,

AVL Systems for Bus Transit

,

Transportation Research Board, National Research Council, Washington D.C., 1997.

APPENDIX A

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality A-1

Appendix A

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION/DISSATISFACTION RESEARCH

— AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Consumer behavior as a distinct discipline dates only from the mid 1960s. Interest in understanding and

tracking specific consumer problems grew dramatically in the late 1970s under the broad label of

consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction (CS/D) research. Its growth coincided with (and was abetted by) a

growing interest on the part of both government regulators and leaders with the consumer movement in

making the policy formulation process more rational and systematic. Critics of past consumer policy

formulation had argued that it was too often influenced by chance events, letter-writing campaigns,

media publicity, and partisan political agendas. The earliest comprehensive CS/D studies were, in fact,

motivated by the policy planning needs of a public regulatory agency, the Federal Trade Commission

(Technical Advisory Research Program (TARP) 1979), and a private non-profit sector organization,

Ralph Nader's Center for Study of Responsive Law.

Pioneering studies by Handy and Pfaff in the mid 1970s developed raw and weighted indexes of

consumer satisfaction with food products across seven broad food categories. After that point, research

on the topic grew rapidly.

Since 1985, two different patterns have emerged. First, there has been a considerable drop in CS/D

research from a public policy perspective. At the same time, however, there has been substantial growth

in interest in the topic of consumer satisfaction research within the private sector. This has been driven

primarily by the growth of the service sector of the economy where managers have realized that

tracking satisfaction is crucial to success when intangibles such as personal attention and atmospheres

are the "product." A number of private satisfaction tracking services have emerged. Many of these

services have made extensive use of earlier methodological developments in social policy research.

Initial studies on CS/D sought to calibrate the amount and types of dissatisfaction in the marketplace as

a basis for policy planning. This body of research was largely descriptive (TARP 1979). Wide variation

was found across purchase categories. These studies differ widely in the basic measure of

dissatisfaction they used. Some focused on more or less objective measures of "problems," others on

subjective feelings of "dissatisfaction." Some counted any negative experience whatsoever, some only

"serious" dissatisfactions, and some only the most recent problem. Also, there was the issue of

opportunity for problems. Measures did not always control for frequency of purchase. Definitional

problems persist today.

Most of the early studies were based on survey data. An alternate approach was complaints data, data

on the extent to which consumers voluntarily speak up about their dissatisfactions. Such data have the

advantage of not requiring field surveys; however, they are typically biased in two important ways.

First, some types of problems in some types of industries are more likely to be voiced than others, and

some problems are less serious than others, and or less costly than others. Monopolies are often

relatively "immune" to complaining except from a small elite. Still other industries are more

encouraging of complaints. Finally, not all consumers complain. These problems have led researchers in

recent years to fall back on the more costly, but more objective, survey research methods.

Finally, most CS/D research from 1975 to 1985 was conducted within product and goods producing

industries. Only after 1980 were initial concepts and models developed to measure consumer

satisfaction/dissatisfaction within service industries.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality A-2

Appendix A

LITERATURE SEARCH SUMMARY FOR SERVICE QUALITY AND

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION MEASUREMENT —

OUTSIDE TRANSIT INDUSTRY

Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research

, A. Parasuraman,

Valerie A. Zeithaml, and Leonard L. Berry, Journal of Marketing, Fall 1985, Vol. 49, Number 4,

pp. 41-50.

Overview

The attainment of quality in products and services was a pivotal concern of the 1980s. While quality in

tangible goods has been described and measured by marketers, quality in services is largely undefined

and unresearched. The authors attempt to rectify this situation by reporting the insights obtained in an

extensive exploratory investigation of quality in four service businesses and by developing a model of

service quality. Propositions and recommendations to stimulate future research about service quality are

offered.

Quality and measurement are not easily articulated by consumers (Takeuchi and Quelch 1983).

Interpretation and measurement of quality also present problems for researchers. While the substance

and determinants of quality may be undefined, its contribution to increasing market share and return on

investment is unequivocal.

Existing Knowledge About Service Quality

Knowledge about goods quality is insufficient to understand service quality. Three well-documented

characteristics of services — intangibility, heterogeneity, and inseparability — must be acknowledged.

Because they are performances rather than objects, precise manufacturing specifications concerning

uniform quality can rarely be set. Because of intangibility, the firm may find it difficult to understand

how consumers perceive their services and evaluate service quality (Zeithaml 1981).

Second, services, especially those with high labor content, are heterogeneous: their performance often

varies from producer to producer, from customer to customer, and from day to day. Consistency of

behavior from service personnel (e.g., uniform quality) is difficult to ensure (Booms and Bitner 1981)

because what the firm intends to deliver may be entirely different from what the customer receives.

Third, production and consumption of many services are inseparable (Carmen and Langeard 1980,

Upah 1980). In labor intensive services, quality occurs during service delivery, usually in an interaction

between the client and front-line personnel.

Service quality literature traditionally agrees that service quality is a measure of how well the service

level delivered matches customer expectations. Delivering quality service means conforming to

customer expectations on a consistent basis. (Lewis and Booms 1983)

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality A-3

Appendix A

Insights from Exploratory Qualitative Investigation

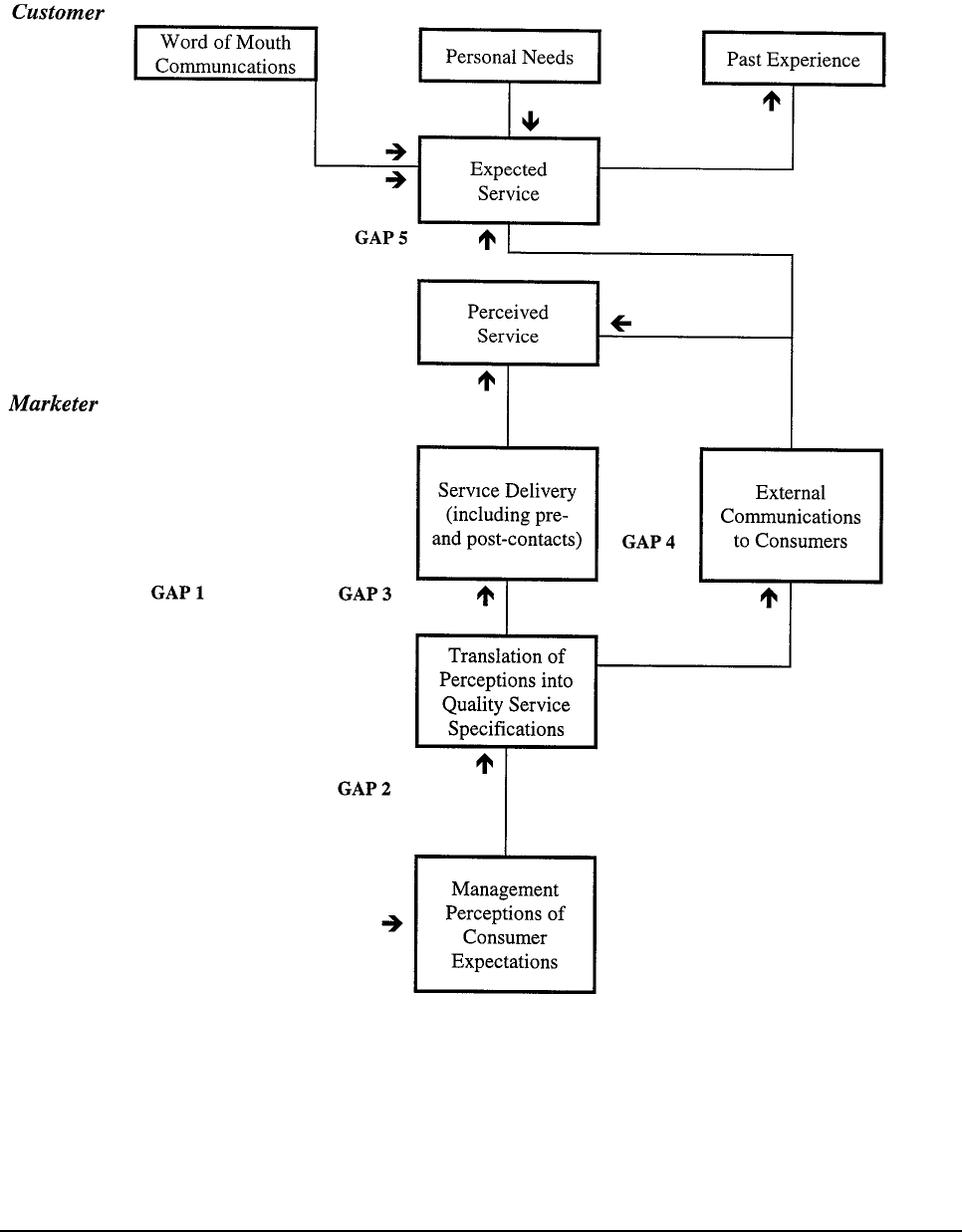

A set of discrepancies or gaps exists regarding executive perceptions of service quality and the tasks

associated with service delivery to consumers. These gaps can be major hurdles to attempting to deliver

a service which consumers would perceive as being high quality. Figure A.1 on the following page

shows the five gap areas identified.

These are:

GAP 1:

Consumer expectation — management perception gap

Discrepancies between executive perceptions and consumer expectations. Service

firm executives may not always understand what features denote high quality to

consumers in advance, what features a service must have in order to meet

consumer needs, and what levels of performance on those features are needed to

deliver high quality service.

GAP 2:

Management perception — service quality specifications

Constraints (resources, or market conditions) which prevent management from

delivering what the consumer expects, or the absence of total management

commitment to service quality.

GAP 3:

Service quality specifications — service delivery gap

Difficulty in standardizing employee performance even when guidelines exist for

performing services well and treating consumers correctly.

GAP 4:

Service delivery — external communications gap

Media advertising and other communications by a firm can affect consumer

expectations. Promising more than can be delivered will raise initial expectations

but lower perceptions of quality when the promises are not fulfilled. Also firms

can neglect to inform consumers of special efforts to ensure quality that are not

visible to consumers thereby affecting consumer perceptions of the delivered

service.

GAP 5:

Expected service — perceived service gap

How consumers perceive the actual service performance in the context of what

they expected. The quality that a consumer perceives in a service is a function of

the magnitude and direction of the gap between expected service and perceived

service.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality A-4

Appendix A

Figure A.1

Service Quality Model

A Quality Service Model

The foundation of the model is the set of gaps shown in Figure A.1. Service quality as perceived by a

consumer depends on the size and direction of GAP 5 that, in turn, depends on the nature of the gaps

associated with the design, marketing, and delivery of services. The gaps on the marketer side of the

equation can be favorable or unfavorable from a service quality perspective. That is, the magnitude and

direction of each gap will have an impact on service quality.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality A-5

Appendix A

The Perceived Service Quality Component

This exploratory investigation suggests that, regardless of the type of service, consumers used basically

similar criteria in evaluating service quality. These criteria seem to fall into 10 key categories that are

labeled "service quality determinants." These determinants are listed in Table A.2 below. Overlap

among the 10 determinants may exist.

Table A.2

Determinants of Service Quality

1 RELIABILITY involves consistency of performance and dependability.

2 RESPONSIVENESS concerns the willingness or readiness of employees to provide

service. It also involves timeliness of service.

3 COMPETENCE means possession of the required skills and knowledge to perform

the service.

4 ACCESS involves approachability and ease of contact.

5 COURTESY involves politeness, respect, consideration, and friendliness of contact

personnel.

6 COMMUNICATION means keeping customers informed in language they can