T

RANSIT

C

OOPERATIVE

R

ESEARCH

P

ROGRAM

SPONSORED BY

The Federal Transit Administration

TCRP

Report 47

A Handbook for Measuring Customer

Satisfaction and Service Quality

Transportation Research Board

National Research Council

TCRP OVERSIGHT AND PROJECT

SELECTION

COMMITTEE

CHAIR

ROBERT G. LINGWOOD

BC Transit

MEMBERS

GORDON AOYAGI

Montgomery County Government

J. BARRY BARKER

Transit Authority of River City

LEE BARNES

Barwood, Inc.

RONALD L. BARNES

Central Ohio Transit Authority

GERALD L. BLAIR

Indiana County Transit Authority

ROD J. DIRIDON

IISTPS

SANDRA DRAGGOO

CATA

CONSTANCE GARBER

York County Community Action Corp.

DELON HAMPTON

Delon Hampton & Associates

KATHARINE HUNTER-ZAWORSKI

Oregon State University

JOYCE H. JOHNSON

North Carolina A&T State University

ALAN F. KIEPPER

Parsons Brinckerhoff, Inc.

PAUL LARROUSSE

Madison Metro Transit System

EVA LERNER-LAM

The Palisades Consulting Group, Inc.

GORDON J. LINTON

FTA

DON S. MONROE

Pierce Transit

PATRICIA S. NETTLESHIP

The Nettleship Group, Inc.

JAMES P. REICHERT

Reichert Management Services

RICHARD J. SIMONETTA

MARTA

PAUL P. SKOUTELAS

Port Authority of Allegheny County

PAUL TOLIVER

King County DOT/Metro

MICHAEL S. TOWNES

Peninsula Transportation Dist. Comm.

LINDA S. WATSON

Corpus Christi RTA

EX OFFICIO MEMBERS

WILLIAM W. MILLAR

APTA

KENNETH R. WYKLE

FHWA

JOHN C. HORSLEY

AASHTO

ROBERT E. SKINNER, JR.

TRB

TDC EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

LOUIS F. SANDERS

APTA

SECRETARY

ROBERT J. REILLY

TRB

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 1999

OFFICERS

Chair:

Wayne Shackelford, Commissioner, Georgia DOT

Vice Chair:

Martin Wachs, Director, Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California at

Berkeley

Executive Director:

Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board

MEMBERS

SHARON D. BANKS,

General Manager, AC Transit

(Past Chairwoman, 1998)

THOMAS F. BARRY, JR.,

Secretary of Transportation, Florida DOT

BRIAN J. L. BERRY,

Lloyd Viel Berkner Regental Professor, University of Texas at Dallas

SARAH C. CAMPBELL,

President, TransManagement, Inc., Washington, DC

ANNE P. CANBY,

Secretary of Transportation, Delaware DOT

E. DEAN CARLSON,

Secretary, Kansas DOT

JOANNE F. CASEY,

President, Intermodal Association of North America, Greenbelt, MD

JOHN W. FISHER,

Joseph T. Stuart Professor of Civil Engineering and Director, ATLSS

Engineering Research Center, Lehigh University

GORMAN GILBERT,

Director, Institute for Transportation Research and Education, North

Carolina State University

DELON HAMPTON,

Chair and CEO, Delon Hampton & Associates, Washington, DC

LESTER A. HOEL,

Hamilton Professor, Civil Engineering, University of Virginia

JAMES L. LAMMIE,

Director, Parsons Brinckerhoff, Inc., New York, NY

THOMAS F. LARWIN,

General Manager, San Diego Metropolitan Transit Development Board

BRADLEY L. MALLORY,

Secretary of Transportation, Pennsylvania DOT

JEFFREY J. McCAIG,

President and CEO, Trimac Corporation, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

JOSEPH A. MICKES,

Missouri DOT

MARSHALL W. MOORE,

Director, North Dakota DOT

JEFFREY R. MORELAND,

Senior VP, Burlington Northern Santa Fe Corporation

SID MORRISON,

Secretary of Transportation, Washington State DOT

JOHN P. POORMAN,

Staff Director, Capital District Transportation Committee

ANDREA RINIKER,

Executive Director, Port of Tacoma, Tacoma, WA

JOHN M. SAMUELS,

VP—Operations Planning & Budget, Norfolk Southern Corporation, Norfolk, VA

JAMES A. WILDING,

President and CEO, Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority

CURTIS A. WILEY,

Commissioner, Indiana DOT

DAVID N. WORMLEY,

Dean of Engineering, Pennsylvania State University

EX OFFICIO MEMBERS

MIKE ACOTT,

President, National Asphalt Pavement Association

JOE N. BALLARD,

Chief of Engineers and Commander, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

KELLEY S. COYNER,

Administrator, Research and Special Programs, U.S.DOT

MORTIMER L. DOWNEY,

Deputy Secretary, Office of the Secretary, U.S.DOT

DAVID GARDINER,

Assistant Administrator, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

JANE F. GARVEY,

Administrator, Federal Aviation Administration, U.S.DOT

EDWARD R. HAMBERGER,

President and CEO, Association of American Railroads

CLYDE J. HART, JR.,

Maritime Administrator, U.S.DOT

JOHN C. HORSLEY,

Executive Director, American Association of State Highway and

Transportation Officials

GORDON J. LINTON,

Federal Transit Administrator, U.S.DOT

RICARDO MARTINEZ,

National Highway Traffic Safety Administrator, U.S.DOT

WILLIAM W. MILLAR,

President, American Public Transit Association

JOLENE M. MOLITORIS,

Federal Railroad Administrator, U.S.DOT

VALENTIN J. RIVA,

President, American Concrete Pavement Association

ASHISH K. SEN,

Director, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S.DOT

GEORGE D. WARRINGTON,

President and CEO, National Railroad Passenger Corporation

KENNETH R. WYKLE,

Federal Highway Administrator, U.S.DOT

TRANSIT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM

Transportation Research Board Executive Committee Subcommittee for TCRP

WAYNE SHACKELFORD,

Georgia DOT

(Chair)

SHARON D. BANKS,

AC Transit

LESTER A. HOEL,

University of Virginia

THOMAS F. LARWIN,

San Diego Metropolitan Transit Development Board

GORDON J. LINTON,

FTA U.S.DOT

WILLIAM W. MILLAR,

American Public Transit Administration

ROBERT E. SKINNER, JR.,

Transportation Research Board

MARTIN WACHS,

Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California at Berkeley

T RANSIT C OOPERATIVE R ESEARCH P ROGRAM

Report 47

A Handbook for Measuring Customer

Satisfaction and Service Quality

MORPACE INTERNATIONAL, INC.

Farmington Hills, MI

in association with

CAMBRIDGE SYSTEMATICS, INC.

Cambridge, MA

Subject Areas

Public Transit

Research Sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration in

Cooperation with the Transit Development Corporation

T

RANSPORTATION

R

ESEARCH

B

OARD

N

ATIONAL

R

ESEARCH

C

OUNCIL

NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS

Washington, D.C. 1999

TRANSIT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM

The nation's growth and the need to meet mobility,

environmental, and energy objectives place demands on public

transit systems. Current systems, some of which are old and in need

of upgrading, must expand service area, increase service frequency,

and improve efficiency to serve these demands. Research is

necessary to solve operating problems, to adapt appropriate new

technologies from other industries, and to introduce innovations

into the transit industry. The Transit Cooperative Research Program

(TCRP) serves as one of the principal means by which the transit

industry can develop innovative near-term solutions to meet

demands placed on it.

The need for TCRP was originally identified in

TRB Special

Report 213—Research for Public Transit: New Directions,

published in 1987 and based on a study sponsored by the Urban

Mass Transportation Administration—now the Federal Transit

Administration (FTA). A report by the American Public Transit

Association (APTA),

Transportation 2000

, also recognized the

need for local, problem-solving research. TCRP, modeled after the

longstanding and successful National Cooperative Highway

Research Program, undertakes research and other technical

activities in response to the needs of transit service providers. The

scope of TCRP includes a variety of transit research fields

including planning, service configuration, equipment, facilities,

operations, human resources, maintenance, policy, and

administrative practices.

TCRP was established under FTA sponsorship in July 1992.

Proposed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, TCRP was

authorized as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation

Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA). On May 13, 1992, a

memorandum agreement outlining TCRP operating procedures was

executed by the three cooperating organizations: FTA, the National

Academy of Sciences, acting through the Transportation Research

Board (TRB); and the Transit Development Corporation, Inc.

(TDC), a nonprofit educational and research organization

established by APTA. TDC is responsible for forming the

independent governing board, designated as the TCRP Oversight

and Project Selection (TOPS) Committee.

Research problem statements for TCRP are solicited periodically

but may be submitted to TRB by anyone at any time. It is the

responsibility of the TOPS Committee to formulate the research

program by identifying the highest priority projects. As part of the

evaluation, the TOPS Committee defines funding levels and

expected products.

Once selected, each project is assigned to an expert panel,

appointed by the Transportation Research Board. The panels

prepare project statements (requests for proposals), select

contractors, and provide technical guidance and counsel throughout

the life of the project. The process for developing research problem

statements and selecting research agencies has been used by TRB

in managing cooperative research programs since 1962. As in other

TRB activities, TCRP project panels serve voluntarily without

compensation.

Because research cannot have the desired impact if products fail

to reach the intended audience, special emphasis is placed on

disseminating TCRP results to the intended end users of the

research: transit agencies, service providers, and suppliers. TRB

provides a series of research reports, syntheses of transit practice,

and other supporting material developed by TCRP research. APTA

will arrange for workshops, training aids, field visits, and other

activities to ensure that results are implemented by urban and rural

transit industry practitioners.

The TCRP provides a forum where transit agencies can

cooperatively address common operational problems. The TCRP

results support and complement other ongoing transit research and

training programs.

TCRP REPORT 47

Project B-11 FY'95

ISSN 1073-4872

ISBN 0-309-06323-X

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 99-71030

© 1999 Transportation Research Board

Price $53.00

NOTICE

The project that is the subject of this report was a part of the Transit

Cooperative Research Program conducted by the Transportation

Research Board with the approval of the Governing Board of the

National Research Council. Such approval reflects the Governing

Board's judgment that the project concerned is appropriate with respect

to both the purposes and resources of the National Research Council.

The members of the technical advisory panel selected to monitor this

project and to review this report were chosen for recognized scholarly

competence and with due consideration for the balance of disciplines

appropriate to the project. The opinions and conclusions expressed or

implied are those of the research agency that performed the research,

and while they have been accepted as appropriate by the technical

panel, they are not necessarily those of the Transportation Research

Board, the National Research Council, the Transit Development

Corporation, or the Federal Transit Administration of the U.S.

Department of Transportation.

Each report is reviewed and accepted for publication by the technical

panel according to procedures established and monitored by the

Transportation Research Board Executive Committee and the

Governing Board of the National Research Council.

To save time and money in disseminating the research findings, the

report is essentially the original text as submitted by the research

agency. This report has not been edited by TRB.

Special Notice

The Transportation Research Board, the National Research Council, the

Transit Development Corporation, and the Federal Transit

Administration (sponsor of the Transit Cooperative Research Program)

do not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers'

names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the

clarity and completeness of the project reporting.

Published reports of the

TRANSIT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM

are available from:

Transportation Research Board

National Research Council

2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20418

and can be ordered through the Internet at

http://www.nas.edu/trb/index.html

Printed in the United States of America

FOREWORD

By Staff

Transportation Research

Board

This handbook focuses on how to measure customer satisfaction and how to

develop transit agency performance measures. It will be of interest to transit managers,

market research and customer service personnel, transit planners, and others who need

to know about measuring customer satisfaction and developing transit agency

performance measures. The handbook provides methods on how to identify,

implement, and evaluate customer satisfaction and customer-defined quality service.

Transit agencies are concerned with delivering quality service to customers, which

is often defined by on-time performance, comfort, safety, and convenience. Transit

agencies continually strive to define quality service, yet a problem exists—definitions

of such service often evolve from management's perceptions of what constitutes

quality. These management definitions may vary significantly from what current and

potential customers perceive to be quality service.

Consumer definitions of quality service could prove helpful to the transit industry.

Under TCRP Project B-11,

Customer-Defined Transit Service Quality,

research was

undertaken by MORPACE International, Inc., to develop a methodology to assist

transit agencies in identifying, implementing, and evaluating customer-defined service

quality and in defining performance indicators that include customer-defined quality

service measures for fixed-route transit. This research includes rural, suburban, and

urban markets.

To achieve the project objective of producing a handbook, the researchers

conducted a review of current literature related to customer-defined transit service

quality measures, customer satisfaction measurement techniques within transit and

other industries, and transit performance measures and indicators. Next, the research

team developed a comprehensive list of service-quality measures from the customer's

perspective, ensuring that each measure was specific and clearly defined. A survey

was administered to customers to arrive at a ranking of service-quality measures, in

order of their impact on overall customer satisfaction. The survey instrument was

developed and refined based on the results of pretests. Alternative methods for ranking

servicequality measures were explored and evaluated, and a new approach was

introduced. Finally, the list of service-quality measures was compared with the list of

agency performance indicators, and the performance measures were revised to reflect

customerdefined service. Using the research findings from the field test, the

methodology was refined and a preliminary method for assessing transit operations

was developed. Methods for benchmarking and tracking information are also

identified.

COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAMS STAFF

ROBERT J. REILLY,

Director, Cooperative Research Programs

STEPHEN J. ANDRLE,

Manager, Transit Cooperative Research Program

GWEN CHISHOLM,

Senior Program Officer

EILEEN P. DELANEY,

Managing Editor

JAMIE M. FEAR,

Associate Editor

PROJECT PANEL B-11

GWENDOLYN A. MITCHELL,

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority

(Chair)

JEFFREY ARNDT,

Metropolitan Transit Authority, Houston, TX

KATHRYN COFFEL,

Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District, Portland, OR

RONALD E. COOK,

Chicago Transit Authority

FRANK T. MARTIN,

Miami Dade Transit Agency

JAMES E. RICKS,

Southeast Missouri State University

GLENNA WATSON,

Central Ohio Transit Authority

GERALD A. WEISS,

Minnesota DOT

YVONNE V. GRIFFIN,

FTA Liaison Representative

PETER SHAW,

TRB Liaison Representative

CONTENTS

1 CHAPTER 1 Introduction

1A. The Goals of Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality Measurement, 1

1B. How to Use This Handbook, 3

1C. Key Words, 4

5 CHAPTER 2 Goals for Transit Industry Service Quality Measurement

2A. Benefits and Requirements of Service Quality Measurement for Transit, 5

2B. Brief History of Customer Satisfaction Measurement, 6

2C. Defining Service Quality Measurement, 6

11 CHAPTER 3 Identifying Determinants of Service Quality

15 CHAPTER 4 Quantitative Analytical Techniques

4A. Overview, 15

4B. Problems with the Factor Analysis Approach, 16

4C. Uses of Quadrant Analysis, 17

4D. Regional and Industry Response Bias, 17

4E. Customer Loyalty and Establishing Customer Satisfaction Indices, 18

4F. Market Segmentation of Customer Satisfaction Findings, 20

4G. Linking Customer Satisfaction to Performance Measures, 20

23 CHAPTER 5 Impact Score Technique: An Explanation of the Method

27 CHAPTER 6 Impact Scores as Tracking Measures

29 CHAPTER 7 Quantitative Research Design

7A. Overview, 29

7B. Questionnaire Development, 30

7C. Response Rates and Sampling Error Estimates, 30

7D. Customer Satisfaction Benchmark Survey Instrument, 31

33 CHAPTER 8 An Illustration of Comparative Quantitative Results—

Using Alternative Analytical Techniques

8A. CTA Red Line – Computation of Impact Scores, 33

8B. CTA Red Line – Comparison with Quadrant Analysis, 34

8C. CTA Red Line – Translation of Impact Scores to a Report Card, 35

8D. CTA Red Line – Comparison with Factor Analysis, 39

8E. CTA Blue Line – Computation of Impact Scores, 41

8F. CTA Blue Line – Comparison with Quadrant Analysis, 41

8G. CTA Blue Line – Translation of Impact Scores to a Report Card, 42

8H. CTA Blue Line – Comparison with Factor Analysis, 46

8I. Combined CTA Rail – Computation of Impact Scores, 48

8J. Combined CTA Rail – Comparison with Quadrant Analysis, 49

8K. Market Segmentation of CTA Rail Customer Satisfaction Findings, 53

8L. Sun Tran – Computation of Impact Scores, 57

8M. Sun Tran – Comparison with Quadrant Analysis, 57

8N. Sun Tran – Translation of Impact Scores to a Report Card, 58

8O. Sun Tran – Comparison with Factor Analysis, 62

8P. Market Segmentation of Sun Tran Satisfaction Findings, 63

8Q. GLTC – Computation of Impact Scores, 67

8R. GLTC – Translation of Impact Scores to a Report Card, 68

71 CHAPTER 9 Agency Review of Customer Satisfaction Survey Findings

9A. General Reactions to Results, 71

9B. Usefulness of Survey Procedures and Application of Findings, 72

9C. Reactions to Findings Relevant to Specific Attributes, 72

81 CHAPTER 10 Converting Service Quality Research Findings into Transit

Agency Performance Measures

10A. Introduction, 81

10B. A Transit Agency's Perspective to Transit Performance Measurement, 81

10C. Overview of Transit Performance Measures, 83

10D. Frequency of Transit Service, 88

10E. Reliability of Transit Service, 90

10F. Explanations and Announcement of Delays, 91

10G. Crowding On-board Trains and Buses, 92

10H. Behavior of Other Riders, 92

10I. Smoothness of the Ride, 93

10J. Cost Effectiveness, Affordability, and Value, 93

10K. Availability of Seats, 94

10L. Frequency of Delays due to Repairs/Emergencies, 94

10M. Passenger Environment On-board Vehicles and at Stations/Stops, 94

99 CHAPTER 11 An Overview of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

11A. Principles of Data Collection, 99

11B. Approaches to the Analysis of Performance Data, 101

A-1 APPENDIX A

Customer Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction Research – An Historical Perspective, A-1

Literature Search Summary for Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction

Measurement – Outside Transit Industry, A-2

A-19 APPENDIX B Moderator's Guide

A-27 APPENDIX C Development and Refining of Customer Measures

A-37 APPENDIX D Sampling Plan for the TCRP B-11 Project Field Test

A-43 APPENDIX E Sample On-board Survey

A-45 APPENDIX F Customer-Defined Transit Service Quality Measures Survey

A-57 APPENDIX G The Relationship of Performance Measures to Customer-

Defined Service Attributes

A-88 REFERENCES

A-89 REFERENCES - APPENDIX

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality

1

A Handbook for Measuring Customer Satisfaction

and Service Quality

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

1A. The Goals of Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality Measurement

For transit agencies, as in other service industries, increases in customer satisfaction translate into

retained markets, increased use of the system, newly attracted customers, and a more positive public

image. To accomplish these ends, public transit needs reliable and efficient methods for identifying the

determinants of service quality from the customers' perspective.

The primary focus of this handbook is how to measure customer satisfaction and how to develop transit

agency performance measures in response to research findings. These are key elements of an ongoing

customer satisfaction monitoring process. However, before proceeding with these tasks, it is helpful to

consider the framework implied when customer feedback becomes the driver of agency service

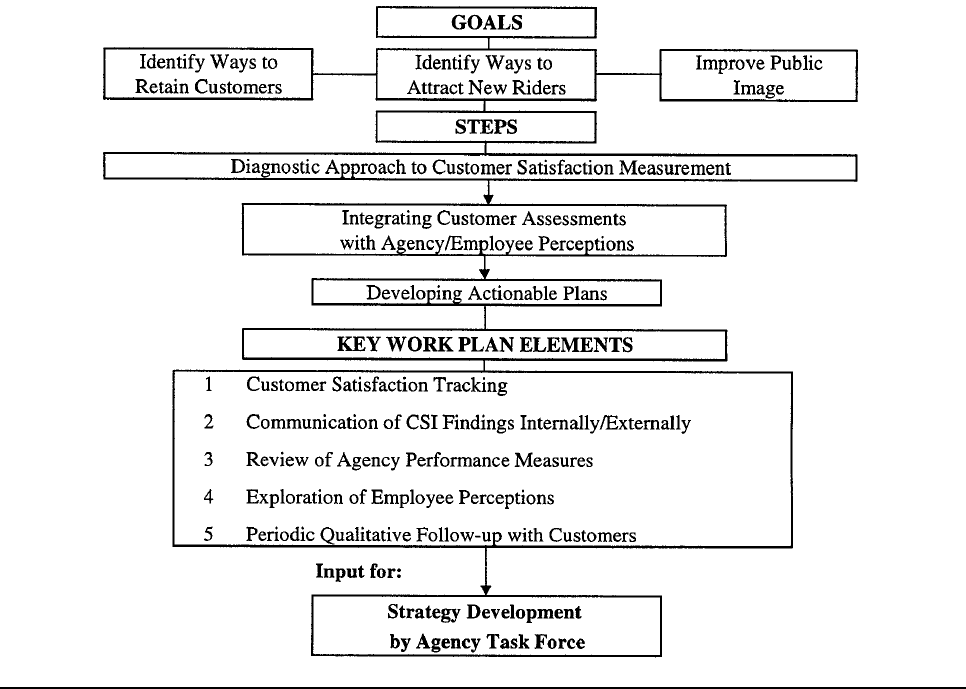

improvement actions. Chart 1.1 below sets forth the goals, steps, and key work plan elements of a

successful customer satisfaction management plan.

Chart 1.1

Overall Customer Satisfaction Management Plan

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality

2

The results of a customer satisfaction measurement program cannot be expected to drive transit agency

service improvement plans unless the findings correlate with agency-based performance measures, i.e.

that data which the agency collects on a regular basis to document service performance. Customer

perspectives must also be validated or understood by frontline transit agency employees if corrective

action plans are to translate into successful implementation.

Hence, the customers' perspective, as measured, must be effectively communicated to agency personnel.

This communication should facilitate management's use of customer feedback in determining which

service improvements require immediate attention, which require further monitoring, and which

indicate a need for educating customers about service parameters. For while customers must always be

first, customers may not always be right. A fully diagnostic approach to customer satisfaction

measurement is essential, rather than reliance on ratings and ranking of service attributes alone.

Customer satisfaction indices, or CSIs, are determined from benchmark and tracking customer surveys.

These indices rely on measuring the impact of customers' ratings of individual service attributes on

overall satisfaction with service.

Several quantitative survey analysis techniques for this measurement are in use within transit and other

service industries. These include quadrant and gap analysis, factor analysis and multiple regression

analysis, and scattergrams. Of these, only factor and regression analysis can provide quantitative

benchmarks for continuous tracking, but problems are inherent. These include the need for large sample

sizes, the complications of explaining variability and weights, and reduction of potentially rich

individual service attribute findings into results for aggregated dimensions — with less relevancy for

specific transit improvements and performance measures.

This handbook proposes a new, simpler "impact score" or problems encountered approach. This

approach determines the relative impact of service attributes on overall satisfaction, when a recent

problem with the attribute is reported. Since the primary way transit agencies can improve customers'

overall satisfaction with service is to reduce customers' problematic experiences, the goal is to identify

those attributes which have the greatest negative impact on overall satisfaction and the greatest number

of customers encountering a problem. These "driver attributes" can be identified and prioritized in a

threestep process. Large sample and subsample sizes, and multivariate analysis techniques, are not

required.

Another advantage of the impact score approach is that while more demanding telephone benchmark

surveys are recommended to establish baselines, periodic (annual or biannual) updates and tracking of

impact scores can be accomplished via on-board rider surveys only. These tracking updates can focus

on problem occurrence and those measures of service quality found in the baseline survey to have the

greatest impact on overall satisfaction.

For those transit agencies currently conducting customer satisfaction research using other methods,

adding the impact score approach will require only the following minor addition to the questionnaire.

After asking customers for their satisfaction rating on each individual service attribute (a series of

questions almost always included), the follow-up question, "Have you experienced a problem with this

service attribute within the last 30 days?"

(1: "Yes", 2: "No")

will be asked.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality

3

Unquestionably, all customer satisfaction analytical methods can be used in combination to fully

explore underlying relationships in customer perceptions, with the overall, diagnostic goal of

determining what elements of service need improvement. In combination with other approaches, or

alone, impact scores provide a straightforward method with results that are easy to explain, do not

require large sample sizes, and that streamline procedures for measuring — and improving — customer

satisfaction over time.

The TCRP B-11 project comparatively field-tested the impact score and other customer satisfaction

measurement approaches at three transit agency sites:

•

an urban rail system, the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) Red Line and CTA Blue Line in

Chicago, Illinois,

•

a suburban bus system, Sun Tran in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and

•

a small city bus system, Greater Lynchburg Transit Company (GLTC) in Lynchburg, Virginia.

1B. How to Use This Handbook

This handbook is organized for the "new ideas" and "comprehensive" customer satisfaction measurement

reader.

If you are interested in:

1. How to Measure and Compute Impact Scores GO TO CHAPTERS 5 AND 6

2. Benefits, Requirements, and a Brief History of GO TO CHAPTER 2 AND

Customer Satisfaction Measurement APPENDIX A

3. Identifying the Determinants of Service Quality GO TO CHAPTER 3 AND

from a Qualitative Perspective APPENDICES B AND C

Example List of Transit Service Quality Measures Page 13

4. A Review of Quantitative Customer Satisfaction

Measurement Techniques

GO TO CHAPTERS 4 AND 8

5. Customer Satisfaction Research Design and Data GO TO CHAPTER 7 AND

Collection Methods APPENDICES D, E, AND F

Customer Satisfaction Benchmark Survey

Instrument

APPENDIX F

6. The Development of Agency Performance GO TO CHAPTERS 9, 10,

Measures AND 11 AND APPENDIX G

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality

4

1C. Key Words

Customer satisfaction measurement or indexing, or customer-defined service quality

— determining the

relevant impact of customers' ratings of individual service attributes on overall satisfaction with service.

Impact score or things gone wrong approach

— a new approach to customer satisfaction measurement

used extensively within automotive research and described herein.

Drivers of overall satisfaction

— those service attributes with the greatest impact on overall satisfaction

with service.

Attribute impact scores

— scores that indicate the relevant position of a service attribute in terms of its

impact on overall customer satisfaction and rate of customer reported problem occurrence.

Problem occurrence

— the percent of customers experiencing a problem with a service attribute within

the past 30 days.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality

5

CHAPTER 2. GOALS FOR TRANSIT INDUSTRY SERVICE QUALITY

MEASUREMENT

2A. Benefits and Requirements of Service Quality Measurement for Transit

Although empirical evidence is limited, increases in customer satisfaction are generally believed to:

•

shift the demand curve upward and/or make the slope of the curve steeper (i.e., lower price

elasticity, higher margins)

•

reduce marketing costs (customer acquisition requires more effort)

•

reduce customer turnover

•

lower employee turnover (satisfied customers affect the satisfaction of front-line personnel)

•

enhance reputation and public image (positive customer word-of-mouth)

•

reduce failure costs (handling customer complaints).

1

For transit agencies, an increase in customer satisfaction translates into retained riders, increased use of

the system, newly attracted customers, and an improved public image.

The requirements for a transit industry service quality measurement process are:

•

to derive the determinants of service quality from the customers;

•

to benefit from best practices established for service quality measurement within other

industries;

•

to take into account the complexities and unique aspects of public transit service;

•

to consider the differences inherent in urban, suburban, and rural systems – including modal

differences; and

•

to develop methods that are reasonably easy to describe and to implement so that cost and time

allocations are efficient.

Within the transit industry, only limited survey based customer satisfaction indexing research has been

conducted. The 1993 IDEA study

2

, based on small sample sizes within three urban transit systems, the

1995 Northwest Research Chicago Transit Authority Customer Satisfaction Report

3

, and customer

satisfaction studies conducted by BART in San Francisco

4

, TRI-MET in Portland, Oregon, and

MARTA in Atlanta are notable among the studies that have been published.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality

6

2B. Brief History of Customer Satisfaction Measurement

Appendix A provides a thorough literature review summary as to historical and methodological

perspectives of customer satisfaction research.

Consumer behavior as a distinct discipline dates only from the mid 1960s. Interest in understanding and

tracking specific consumer problems grew dramatically in the late 1970s under the broad label of

consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction (CS/D) research. Its growth coincided with a growing interest on

the part of government regulators and consumer advocates in making policy formulation more rational

and systematic. The earliest comprehensive CS/D studies were, in fact, motivated by the policy

planning needs of a public regulatory agency, the Federal Trade Commission (Technical Advisory

Research Program 1979), and a private non-profit sector organization, Ralph Nader's Center for Study

of Responsive Law. Most CS/D research from 1975 to 1985 was conducted within product and goods

industries. Only after 1980 were initial concepts and models developed to measure consumer

satisfaction/dissatisfaction within service industries.

Since 1985, two different patterns have emerged. First, there has been a considerable drop in CS/D

research from a public policy perspective. At the same time, however, there has been substantial growth

in interest in the topic of consumer satisfaction research in the private sector. This has been driven

primarily by the growth of the service sector of the economy where managers have realized that

tracking satisfaction is crucial to success when intangibles such as personal attention and atmospheres

are the "product". A number of private sector satisfaction tracking services have emerged. Many of

these services have made extensive use of earlier methodological developments in social policy

research.

Most of the early studies were based on survey data. An alternative approach was complaints data, data

on the extent to which consumers voluntarily speak up about their dissatisfactions. Such data have the

advantage of not requiring field surveys; however, they are typically biased in two important ways.

First, some types of problems in some types of industries are more likely to be voiced than others, and

some problems are less serious than others, and/or less costly than others. Monopolies, such as some

transit systems, are often relatively "immune" to complaining except from a small elite. Finally, not all

consumers complain. These problems have led researchers in recent years to fall back on the more

costly, but more objective, survey research methods.

Initial survey research studies on CS/D sought to calibrate the amount and types of dissatisfaction in the

marketplace as a basis for policy planning. This body of research was largely descriptive. Wide

variation was found across purchase categories. These studies differ widely in the basic measure of

dissatisfaction they used. Some focused on more or less objective measures of "problems", others on

subjective feelings of "dissatisfaction." Some counted any negative experience whatsoever, some only

"serious" dissatisfactions, and some only the most recent problem. Also, there was the issue of

opportunity for problems. Definitional problems persist today.

2C. Defining Service Quality Measurement

Customer satisfaction research literature traditionally agrees that service quality is a measure of how

well the service level delivered matches customer expectations. Delivering quality service means

conforming to customer expectations on a consistent basis.

5

However, clearly, the fact that expectations

are confirmed is not always sufficient for satisfaction.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality

7

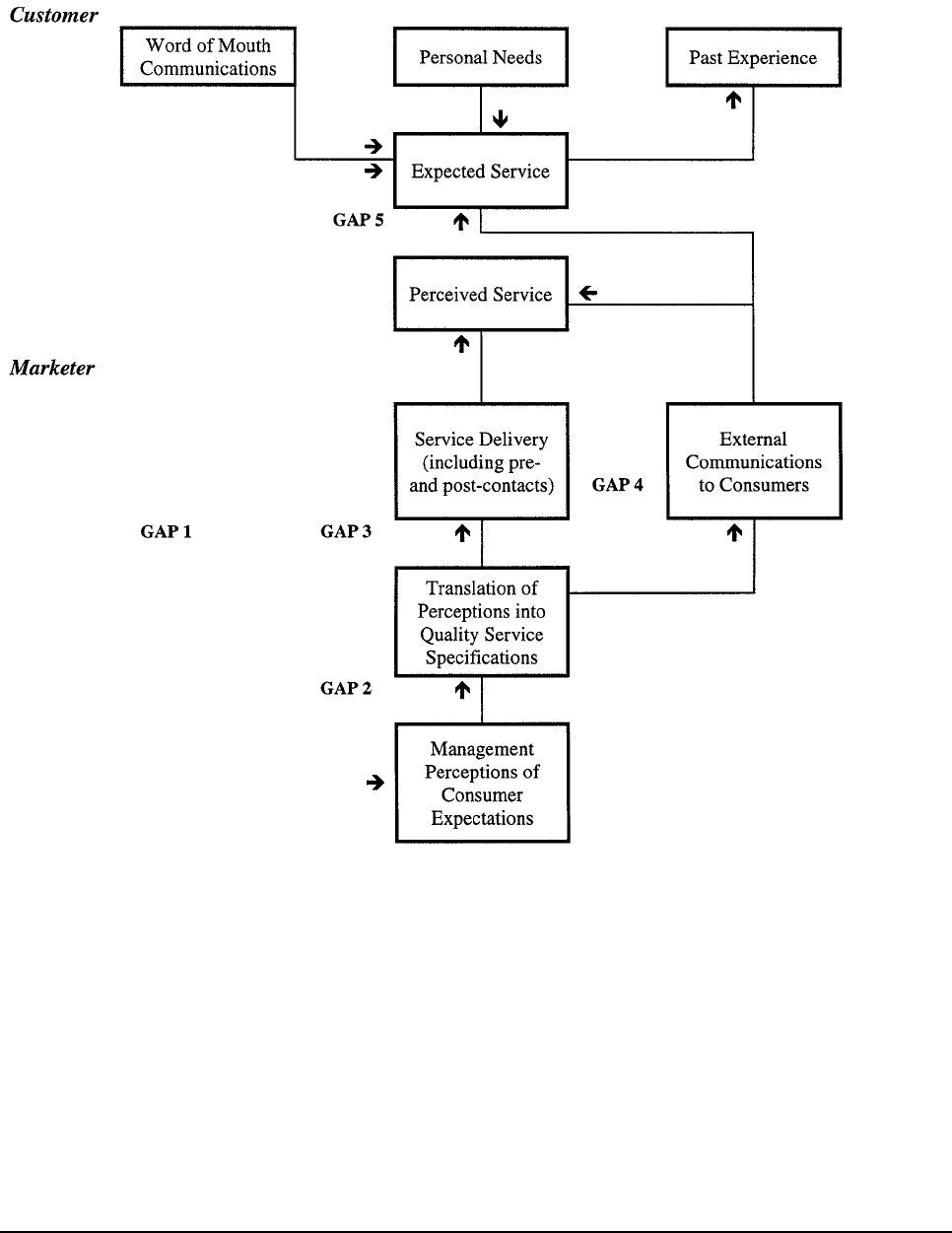

Generally, a set of discrepancies or gaps exists regarding organizational perceptions of service quality

and the tasks associated with service delivery to consumers. These gaps can be major hurdles to

attempting to deliver a service that consumers would perceive as being high quality. Chart 2.1 on the

following page shows the five gap areas identified.

These are:

GAP 1: Consumer expectation — management perception gap

These are discrepancies between executive perceptions and consumer expectations.

Transit agency executives may not always understand what features connote high

quality to consumers in advance, what features a service must have in order to meet

consumer needs, and what levels of performance on those features are needed to

deliver high quality service.

GAP 2: Management perception — service quality specifications

There may be constraints (resources, or market conditions) which prevent

management from delivering what the consumer expects, or there may be an absence

of total management commitment to service quality.

GAP 3: Service quality specifications — service delivery gap

There may be difficulty in standardizing employee performance even when

guidelines exist for performing services well and treating consumers correctly.

GAP 4: Service delivery — external communications gap

Media advertising and other communications by an agency can affect consumer

expectations. Promising more than can be delivered will raise initial expectations but

lower perceptions of quality when the promises are not fulfilled. Also, transit

agencies can neglect to inform consumers of special efforts to assure quality that are

not visible to consumers, thereby affecting consumer perceptions of the delivered

service.

GAP 5: Expected service — perceived service gap

This is how consumers perceive the actual service performance in the context of what

they expected. The quality that a consumer perceives in a service is a function of the

magnitude and direction of the gap between expected service and perceived service.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality

8

Chart 2.1

Service Quality Model

Service quality, as perceived by a consumer, depends on the size and direction of GAP 5 which, in turn,

depends on the nature of the gaps associated with the design, marketing, and delivery of services. That

is, the magnitude and direction of each gap will have an impact on service quality.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality

9

ENDNOTES

1

Fornell, Claes, "

A National Customer Satisfaction Barometer: The Swedish

Experience",

Journal of Marketing, January 1992, Volume 56, Number 1, pp. 6-

21.

2

IDEA Program Final Report, Customer Satisfaction for the Mass Transit Industry,

Contract: TRANSIT-1, Transportation Research Board, prepared by: Tri-County

Metropolitan Transportation District of Oregon, August, 1995.

3

Customer Satisfaction Survey of Chicago Transit Authority Riders, Northwest

Research Group, Inc., December, 1995.

4

Passenger Environment Survey Report, BART Customer and Performance

Research, January - March 1997.

5

Lewis, Robert C. and Bernard H. Booms (1983), "The Marketing Aspects of

Service Quality" in

Emerging Perspectives on Services Marketing,

L. Berry, G.

Shostack, and G. Upah, eds., Chicago: American Marketing, pp. 99-107.

This page left intentionally blank.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 11

CHAPTER 3. IDENTIFYING DETERMINANTS OF SERVICE

QUALITY

Exploratory investigation suggests that, within most service industries, consumers use basically similar

criteria in evaluating service quality.

6

These criteria seem to fall into 10 key categories labeled "service

quality determinants". These determinants are listed below. Overlap among the 10 determinants may

exist.

Determinants of Service Quality

1 RELIABILITY involves consistency of performance and dependability.

2 RESPONSIVENESS concerns the willingness or readiness of employees to provide

service. It also involves timeliness of service.

3 COMPETENCE means possession of the required skills and knowledge to perform the

service.

4 ACCESS involves approachability and ease of contact.

5 COURTESY involves politeness, respect, consideration, and friendliness of contact

personnel.

6 COMMUNICATION means keeping customers informed in language they can

understand and listening to them. It may mean that the company has to adjust its

language for different consumers — increasing the level of sophistication with a well-

educated customer and speaking simply and plainly with a novice.

7 CREDIBILITY involves trustworthiness, believability, and honesty. It involves having

the customer's best interests at heart.

8 SECURITY is the freedom from danger, risk, or doubt.

9 UNDERSTANDING/KNOWING THE CUSTOMER involves making the effort to

understand the customer's needs.

10 TANGIBLES includes the physical environment and representations of the service.

Research in other service industries indicates consumers "group" a wide array of attributes of service

under one of the 10 dimensions noted when judging service quality. However, this research is

preliminary and also suggests that it is advisable to determine, within the industry of study, whether

identifiable service quality segments exist — and whether, and in what ways, consumer expectations

differ across industry segments. Investigating how transit customers aggregate attributes of service into

collapsed quality dimensions is important to understanding how customer satisfaction should be

measured within an industry.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 12

Regardless of what eventual quantitative analytical approaches are used, the process must begin with

acquiring a list of service attributes

from the customers

, through an exhaustive "listening to the voice of

the customer" process. This qualitative research is usually conducted through a series of focus groups.

Customers are requested to describe the ideal service or product in all of its feature details. Then

customers are asked to list their basic service or product requirements, starting with primary

requirements and continuing through the secondary and tertiary components of each of these

requirements. The moderator proceeds until the group has exhausted all the possible attributes of

service quality they would consider.

This process is repeated at multiple geographic and customer segment sites and the results are combined

and itemized into a full and complete attribute listing. The wording of the attributes is refined for clarity

and linkage with expected results. For example, "frequent service so that wait times are short". (Or if

further quantification is desirable: "frequent service so that wait times do not exceed 15 minutes".) This

process usually results in a listing of 40 to 55 defined attributes of transit service that can be rated by

customers (see Table 3.1, as an example).

A prototype moderator's guide for focus group sessions conducted to extract and prioritize customer

service quality requirements can be found in Appendix B. Appendix C contains a more detailed

description of the qualitative focus group explorations conducted as a part of the field test for this study,

at each of the three demonstration transit agency sites. The same format was used at each site and for

each transit mode. Recruitment of customers for the focus group sessions was accomplished through

distribution and collection of an on-board, or at-station, questionnaire to passengers. Basic demographic

and trip pattern data were requested, in addition to telephone numbers for the recruitment process.

Once the customer-defined service quality attribute list is developed for a locality, exhaustive

qualitative research with customers does not need to be repeated for several years (every four to seven

years is usually recommended). An open-ended question on the quantitative survey format which asks

respondents to name the one change they would make to improve service, or to name any additional

attributes or factors that have not been mentioned that affect their ratings of service quality, is usually

sufficient to update service quality attribute listings for subsequent tracking research.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 13

Table 3.1

Example List of Transit Service Quality Measures

1 Absence of graffiti

2 Absence of offensive odors

3 Accessibility of trains/buses to handicapped

4 Availability of handrails or grab bars on trains/buses

5 Availability of monthly discount passes

6 Availability of schedule information by phone/mail

7 Availability of schedules/maps at stations/stops

8 Availability of seats on train/bus

9 Availability of shelter and benches at stations/stops

10 Cleanliness of interior, seats, windows

11 Cleanliness of stations/stops

12 Cleanliness of train/bus exterior

13 Clear and timely announcements of stops

14 Comfort of seats on train/bus

15 Connecting bus service to stations/main bus stops

16 Cost effectiveness, affordability, and value

17 Cost of making transfers

18 Displaying of customer service/complaint number

19 Ease of opening doors when getting on/off train/bus

20 Ease of paying fare, purchasing tokens

21 Explanations and announcement of delays

22 Fairness/consistency of fare structure

23 Freedom from nuisance behaviors of other riders

24 Frequency of delays for repairs/emergencies

25 Frequency of service on Saturdays and Sundays

26 Frequent service so that wait times are short

27 Friendly, courteous, quick service from personnel

28 Having station/stop near destination

29 Having station/stop near my home

30 Hours of service during weekdays

31 Number of transfer points outside downtown

32 Physical condition of stations/stops

33 Physical condition of vehicles and infrastructure

34 Posted minutes to next train/bus at stations/stops

35 Quietness of the vehicles and system

36 Reliable trains/buses that come on schedule

37 Route/direction information visible on trains/buses

38 Safe and competent drivers/conductors

39 Safety from crime at stations/stops

40 Safety from crime on trains/buses

41 Short wait time for transfers

42 Signs/information in Spanish as well as English

43 Smoothness of ride and stops

44 Station/stop names visible from train/bus

45 Temperature on train/bus — not hot/cold

46 The train/bus traveling at a safe speed

47 Trains/buses that are not overcrowded

48 Transit personnel who know system

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 14

ENDNOTES

6

A. Parasuraman, Valerie A. Zeithaml, and Leonard L. Berry, Journal of Marketing,

Fall 1985, Vol. 49, Number 4, pp. 41-50.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 15

CHAPTER 4. QUANTITATIVE ANALYTICAL TECHNIQUES

4A. Overview

In a typical quantitative customer satisfaction study, respondents evaluate overall satisfaction, then rate

each individual service attribute that customers have defined. A key question for researchers is which

attributes are the drivers of overall satisfaction (since not all attributes have equal impact)? When there

are 40 to 50 attributes that can impact customer satisfaction, and transit agency resources are limited,

how can it be determined which limited number of attributes should be targeted for problem occurrence

reduction, in order to produce the greatest possible increase in overall customer satisfaction with transit

service?

Researchers have suggested many procedures for dealing with this problem. Several are considered by

Green and Tull (1975)

7

and reviewed in

The Maritz Marketing Research Report

(1993).

8

Work

continues in this area; no true "answer" for all applications has emerged. However,

derived importance

measures

are usually preferred over

stated importance measures.

Stated importance measures

ask respondents to explicitly state their perception of the importance of

each attribute, usually using a 10-point scale. The results of this method can be straightforwardly

interpreted; however, results can be few, if any, statistical differences among attributes, so the aim of

the method — to prioritize attributes — is thwarted. For example, if 600 customers are asked to rate the

transit service on 46 attributes, each on a scale of one to ten, the mean ratings for 8 to 10 of the

attributes may range from 7.3 to 7.5, making the differences among their means statistically

insignificant, using a

t-test of significance.

This makes quadrant analysis unreliable since

differentiations among attributes by their mean importance or mean satisfaction ratings may not be

statistically significant, at least without very large sample sizes. The statistical significance challenge is

compounded when the results of a new tracking survey are compared with benchmark results.

Additionally, the approach does not take into account, or provide a reliable means, for measuring the

relative impact of service attributes on overall satisfaction.

Derived importance methods

rely on the statistical association between individual ratings (predictors)

and an overall satisfaction rating. The importance of an attribute is statistically determined from this

relationship. These measures can be generally described as follows:

1.

Bivariate (Pearson) Correlation:

This measure separately tests the strength of the relationship of each independent variable

(attribute) with the dependent variable (overall satisfaction). It has the advantages of

familiarity and relative simplicity. However, joint effects with other attributes go

undiscovered, and often many attributes are similarly correlated with overall satisfaction.

2.

Multiple Regression Analysis:

This approach allows the inclusion of additional independent variables (attributes) when

testing the relationship with the dependent variable (overall satisfaction). However, an

important consideration is that it is common in customer satisfaction research for

attributes to be correlated — sometimes highly — with each other. This multicolinearity

makes it difficult to measure the separate effects of the individual attributes on overall

satisfaction using the multiple regression approach.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 16

3.

Factor Analysis:

Factor analysis is a statistical technique that is used for many purposes including:

•

revealing patterns of intercorrelationships among variables, and

•

reducing a large number of variables to a smaller number of statistically independent

variables (dimensions) that are each linearly related to the original variables.

4.

Combining Factor Analysis and Multiple Regression Analysis

When multicolinearity is encountered in multiple regression modeling, factor analysis

can be used to first transform the independent variables to a smaller set of dimensions or

artificial variables that are uncorrelated among themselves. Then multiple regression

modeling is performed to predict the relative impact of the newly constructed

dimensions on the dependent variable (overall satisfaction).

To date, factor analysis combined with multiple regression analysis has been the most prevalent

analytical technique applied in customer satisfaction research within the transit industry.

4B. Problems with the Factor Analysis Approach

The

first

inherent problem is that a lot of the richness of the data is lost through factor analysis.

Individual attributes that, in isolation, have a high impact on overall satisfaction may not get targeted

because the factor analysis placed them within a dimension that did not prove crucial. For example, the

attribute of "freedom from the nuisance behaviors of others" may, in isolation, be highly correlated with

overall satisfaction. However, as a result of the factor analysis, this attribute can get placed within the

dimension of "travel environment" or "appearance", a newly constructed dimension which is not found

to have a strong impact on overall satisfaction.

The

second

is that factor analysis and multiple regression modeling, since they are highly complex, are

not easy to describe to transit managers and operations personnel. Empirical data indicates that its use in

other service industries limits "buy-in" by the very personnel who most need to be committed to the

translation of customer expectations into agency performance measures.

The

third

and an important consideration is that it is not a good idea to build complex models if the data

sets or subsample sets are small and the list of independent variables (attributes) you want to measure is

extensive. Large sample sizes are required. This is particularly problematic for the transit industry

where measures are needed for subsample groups such as by transit mode, transit dependent rider versus

non-transit dependent rider, secure customer versus vulnerable or at-risk customer, or by geographic

region of a city, or city vs. suburbs.

As a general rule, the minimum is to have at least five times as many observations as there are variables

to be analyzed, and the more acceptable range would be a ten-to-one ratio. Some researchers even

propose a minimum of 20 cases for each variable. (If 40 service attributes are being measured, the

sample size or sampling strata should be a minimum of 800). "One must remember that with 30

variables, for example, there are 435 correlations in the factor analysis. At a .05 significance level,

perhaps even 20 of those correlations would be deemed significant and appear in the factor analysis just

by chance. The researcher should always try to obtain the highest cases-per-variable ratio to minimize

the chances of "overfitting" the data,.. deriving factors that are sample specific with little generizability."

9

The

fourth

consideration is a cautionary one that, while more sophisticated and elegant analytical methods

have an appeal, it is risky to proceed when simpler and less demanding approaches will work as well.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 17

The results of the Northwest Research 1995 report for the "Customer Satisfaction Survey of Chicago

Transit Authority Riders" indicate that problems of multicolinearity may exist with the factor analysis

approach to customer satisfaction measurement within the transit industry.

10

(MORPACE International,

Inc. does not have the primary factor analysis data results for the previous "IDEA Project" conducted by

J. D. Powers in 1993; however, the sample sizes for this pilot study were so small that a serious

question arises about the validity of the factor analysis results.)

The 1995 CTA Customer Satisfaction Report gives the correlation data results for the dimensions of

both bus travel and rail travel (sample sizes less than 600 each). The report acknowledges that: "It

should be noted that in some cases, variables (attributes) are highly correlated with dimensions that are

different than might be expected — for example, smoothness of ride correlates with driver attributes

rather than with comfort of the ride as might be expected. This would suggest that riders think about

attributes and combine attributes for evaluations in a way that is different from the traditional

performance indicators used by transit (and, we would note, different from the way in which attributes

are traditionally assembled by customers in other industries)."

In Chapter 8 of this report, we provide the results of our factor/regression analysis based on field test

results. The usefulness and reliability of results will be compared with those provided by our proposed

impact score approach.

4C. Uses of Quadrant Analysis

Quadrant analyses of customer satisfaction measures are often used to provide an underlying

understanding of ratings. Thus, for example, "strengths" are shown in one quadrant of the graphs as

those attributes that are above the median in customer importance and also above the median in

customer satisfaction. (Sometimes, as in a Gap Analysis, importances are derived by a bivariate

correlation of attribute satisfaction with overall satisfaction). Likewise, the "weaknesses" or

"opportunity" quadrant contains those attributes above the median in importance, but below the median

in satisfaction. Those attributes below the median in importance, but above the median in satisfaction

can be labeled the "maintenance of effort" quadrant; while the last "non-critical" quadrant contains

those attributes low in importance on which satisfaction is also judged to be low.

The disadvantages of this approach are that the divisions by quadrant are somewhat arbitrary and the

magnitude of the differences between attribute ratings is not usually taken into account. This approach,

while giving a general overview of the relationship between attribute importance and satisfaction

ratings, does not provide a stable quantitative measure of the impact of attributes on overall customer

satisfaction. There are no established numbers for each attribute that provide the benchmarks against

which future similarly collected customer satisfaction attribute measures can be tested — for

statistically significant changes in customer perception.

4D. Regional and Industry Response Bias

Customer measurements are often contaminated by a culture-induced scale bias that may invalidate

crossnational or regional comparisons. The bias reveals itself as a tendency for some customers to give

consistently higher or lower ratings of performance (even when actual performance levels are identical

and expectations are controlled). For example, people from the New England region of the U.S. exhibit

a temperament and follow norms quite unlike those found in Texas ... they are clearly working from

different frames of reference which can color their evaluations.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 18

The following discussion of this problem is excerpted from a 1996 copyright article by Symmetrics

Marketing Corporation, entitled "Measuring Cross-National and Within-Country Response Bias Using

the International Scale Bias Index (ISBI)".

"While methods exist for estimating scale bias, all require that additional information be

obtained from customers. Some of these methods are rather elaborate and tedious (e.g.,

conjoint-based) and/or are difficult to explain to customers (e.g., magnitude estimation). A

(proprietary)

technique developed by Symmetrics (Crosby, 1994; Crosby, 1992) makes it

possible to reliably estimate the magnitude of the scale bias by asking customers

additional questions that are a part of the International Scale Bias Index (ISBI). The index

is formed averaging the ratings of composite items. The items are statements of

performance categorized into six life domains: suppliers, sports, arts, education, science,

and services. Differences between regions/countries in their mean index scores are mainly

reflective of culture induced scale bias, i.e., a generalized tendency to be a harder or easier

grader of performance. The index scores can be used to make adjustments in the customer

measurements from each region/country in order to facilitate "apples-to-apples"

comparisons."

Current methods for correcting cross-regional bias in customer satisfaction measures are proprietary and

costly to incorporate. We point out their existence as a caution against comparing transit service quality

measures across regions and transit agencies.

An additional concern is the comparison of transit customer measures with those measures found within

other industries. In Sweden, the Customer Satisfaction Barometer (CSB) for more than 30 industries

and more than 100 corporations found that CSB scores are significantly higher for products than for

services, and that service monopolies score lower than competitive services (Fornell, 1993). Staple

foods and automobiles score at the top of the CSB; the police force and television broadcasting are at

the bottom (transportation services were not measured as a part of the Sweden CSB).

Thus, given present research methods, it is not advisable to set expected "target zones" for customer

satisfaction within transit, or to compare these measures directly by region, or with measures derived

for other industries. The best use of quantitative service quality measures is as internal benchmarks for

an agency against which future progress can be measured. Additionally, the research must determine

which measures, if targeted, will yield the greatest increase in overall customer satisfaction with service.

4E. Customer Loyalty and Establishing Customer Satisfaction Indices

Most major conceptual and measurement models of customer satisfaction explicitly include elements

related to customer value and customer loyalty. Satisfaction is a necessary, but not a sufficient,

condition of customer loyalty (D. Randall Brandt, 1996).

11

Customer loyalty is not repeat users or

transit dependent riders. Many repeat customers may be choosing transit because of necessity,

convenience, or habit. For these customers, if an alternative becomes available, they may quickly switch

to that service or mode. Instead, customer loyalty is reflected by a combination of attitudes and

behaviors. It usually is driven by customer satisfaction, yet also involves a commitment on the part of

the customer to make a sustained investment in an ongoing relationship with transit service. Attitudes

and behaviors that go with customer loyalty include:

•

an intention to use transit service again

•

a willingness (often an eagerness) to recommend transit service to friends, associates, and

other persons

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 19

•

commitment to, and even identification with, transit service

•

disinterest in and/or a general resistance to alternative means of transportation, when

these are available.

One measure of customer loyalty is the Secure Customer Index (D. Randall Brandt, 1996). A secure

customer is one who says that he or she is:

•

very satisfied with the service

•

definitely will continue to use the service in the future

•

definitely would recommend the service to others

The definition is illustrated in the diagram below:

Chart 4.1

Secure Customer Index

Responses to the three items — overall satisfaction, likelihood to continue using the service, and

likelihood to recommend — can be combined to create multiple classifications or segments based on

the degree of customer security. For example:

Secure Customers = % very satisfied/definitely would repeat/definitely would

recommend

Favorable Customers = % giving at least "second best" response on all three

measures of satisfaction and loyalty

Vulnerable Customers = % somewhat satisfied/might or might not repeat/might or

might not recommend

At Risk Customers = % somewhat satisfied or dissatisfied/probably or

definitely would not repeat/probably or definitely would

not recommend

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 20

The capacity to establish linkages between customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and business results

should be part of the architecture of any organization's customer satisfaction measurement process.

4F. Market Segmentation of Customer Satisfaction Findings

An important advantage of the impact score approach, as will be illustrated in Chapter 8, is that once

segments such as secure and vulnerable customers are identified, impact benchmark and tracking scores

can be easily computed, ordered, and compared by customer loyalty segments.

Modest sample sizes will allow the full impact score analysis to be performed by transit mode segment,

as well as by transit dependent status and such segments as commuters versus non-commuters, and

frequency of use categories.

Chapter 5, which follows, presents a thorough explanation of the Impact Score Approach.

4G. Linking Customer Satisfaction to Performance Measures

The process of linking goals to performance through measuring Customer Satisfaction (CS) is

exploratory and preliminary for even the most forward-thinking companies. First, companies must

formalize and quantify the relationship between CS and firm or agency performance. By determining

how CS improves performance or what specific CS components correlate with different improvements,

corporations can focus on only the most effective endeavors, allowing them to become more efficient in

implementation.

Delivering CS is at an early evolutionary state in most U.S. firms. Most firms are not focused on

satisfying customers, even though research now correlates CS with improved performance. A firm's CS

implementation process must reflect the needs of individual customer segments, and the overall

program must be flexible enough to allow each business unit to develop measures and processes that fit

its management needs.

Properly implemented and managed, the performance measures process ensures that customer input

drives an organization's efforts to improve and innovate, and that the impact of these efforts can be

assessed. The key question is how does the "voice of the customer" data compare with the "voice of the

process" data? Customer expectations must be translated to, and linked with, performance measures for

the agency.

The whole relationship of transit agency performance measures to customer-defined measures is the

topic of Chapters 9, 10, and 11 of this report.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 21

ENDNOTES

7

Green, Paul E. and Tull, Donald S., Research for Marketing Decisions; 3rd edition;

Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1975 (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey), pp. 478-484.

8

Maritz Marketing Report

, 1993.

9

Hair, Anderson, Tatham, Black, Multivariate Data Analysis, pp.373-374, Prentice

Hall, New Jersey.

10

Customer Satisfaction Survey of Chicago Transit Authority Riders, Northwest

Research Group, Inc., December, 1995.

11

"Customer Satisfaction Indexing" D. Randall Brandt, Conference Paper, American

Marketing Association, 1996.

This page left intentionally blank.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 23

CHAPTER 5. IMPACT SCORE TECHNIQUE: AN EXPLANATION OF

THE METHOD

To address the impasse that often occurs in customer satisfaction measurement within the transit

industry, MORPACE International, Inc. has developed a non-proprietary method for deriving customer

satisfaction measures. The approach has an implicit logic that is easily understood and applied.

Variations of this method have been used by MORPACE in major customer satisfaction studies within

the automotive and health care industries.

12

Within the automotive industry this approach is known as

the "Things Gone Wrong" approach.

The Impact Score approach determines the relative impact of attributes on overall satisfaction, by

measuring customers' relative decreases in overall satisfaction, when a recent problem with an attribute

is reported. This makes sense because, within the delivery of quality service framework, the primary

way transit agencies can improve customers' overall satisfaction with service is to reduce customers'

problematic experience with those attributes which have the greatest negative impact on overall

satisfaction. These driver attributes can be identified and prioritized in a three-step process.

Step One

is to determine which attributes have the most impact on

overall

customer

satisfaction. For each attribute, the sample is divided into those respondents who have had

a recent problem with the attribute and those respondents who have not recently

experienced a problem with the attribute. (Those who have not experienced the attribute

within the past 30 days are grouped with those who have, but have not had a problem.)

The mean overall satisfaction ratings of the two groups are compared. The difference

between the two mean overall satisfaction ratings is called the "gap score". Gap scores are

computed and the attributes are then ordered by the size of their gap scores. A

t-test

can be

used to determine where statistical significance lies among gap scores.

The magnitude of an attribute's gap score should not change significantly over time. The

relationship between a service quality attribute and overall satisfaction with transit service

can be assumed to be structural. That is, once it is determined that an attribute is a driver

of customer satisfaction it will probably remain so, unless significant societal changes

occur, i.e., graffiti comes to be viewed as an art form.

Step Two

lists the attribute problem incidence rate for each attribute in a column next to

its gap score. (The percent of customers who experienced a problem with the service

attribute within the past 30 days). It will be important to take into account the rate at

which a problem with an attribute occurs within the customer base. It may be that a

particular attribute has a large gap score (and thereby a significant impact on overall

satisfaction), but the percent of customers reporting a problem with the attribute is

relatively small. In this case, it probably is not worth a transit agency's time and expense

to attempt to further lower the problem occurrence rate for the attribute. On the other

hand, if an attribute's gap score (impact on overall satisfaction) is moderately low, while

the rate at which customers experience a problem with the attribute is high, the effect of

the attribute on overall satisfaction is magnified and will require attention. Whether future

increases or decreases in problem incidence rates are statistically significant can be

validated by statistical tests (e.g.,

chi-square test, z-test of proportions,

etc.).

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 24

Step Three

creates a composite index by multiplying the attribute's overall satisfaction

gap score by the attribute's problem incidence rate. The result is an attribute "impact

score". The attributes are then placed in descending order of their impact scores. The top

attributes are the drivers of customer satisfaction.

To summarize, impact scores are computed as shown in the following example:

Table 5.1

Impact Score Approach

* within the past 30 days

** percent of customers experiencing a problem with the service attribute within the past 30 days

The impact score data analysis can be implemented using just a spreadsheet program. The spreadsheet

can be structured so that the relevant inputs reside in one worksheet, the data analysis is conducted in a

second worksheet, and the results summarized in a third worksheet. Inputs from the survey can be fed

into simple formulas to determine mean ratings by group, gap values, percentages of respondents who

had a problem with transit service, impact scores and

t-tests

to determine the statistical significance of

identified differences. If this data analysis system is constructed in the benchmark year, transit agencies

can input their own tracking data (from on-board surveys) during subsequent years.

This analytical approach is easy to describe to transit managers, the logic is implicit, and the method

can be implemented without using advanced statistical analysis techniques, and with smaller sample and

subsample sizes. The impact scores serve as statistically valid benchmarks for future customer

satisfaction monitoring.

The appropriateness of the formula of multiplying the gap score by the problem incidence rate can be

validated through a quadrant analysis of gap scores against problem incidence rates. What is the relative

impact score of an attribute with a high gap score but a low incidence rate, or a low gap score but high

incidence rate? Does the impact score prioritizing make sense when compared within a quadrant

analysis? If not, weighting schemes for problem incidence rates can be considered.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 25

ENDNOTES

12

Proprietary studies conducted by MORPACE International, Inc. for Ford Motor

Company and Aetna Health Plans during the 1990s.

This page left intentionally blank.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 27

CHAPTER 6. IMPACT SCORES AS TRACKING MEASURES

As previously indicated, gap scores will not change significantly over time. It is problem occurrence

rates that can fluctuate and which can be reduced by transit agency actions. Future increases or

decreases in problem occurrence rates can be measured and validated with a

t-test or chi-square

test.

This makes it possible to limit tracking surveys to a re-measure of overall satisfaction and problem

occurrence rates for each service attribute. With these data, impact scores can be recomputed and

updated. Beyond the benchmark survey, short-form questionnaires can be administered on-board,

greatly reducing continuing research costs for an ongoing customer satisfaction measurement program.

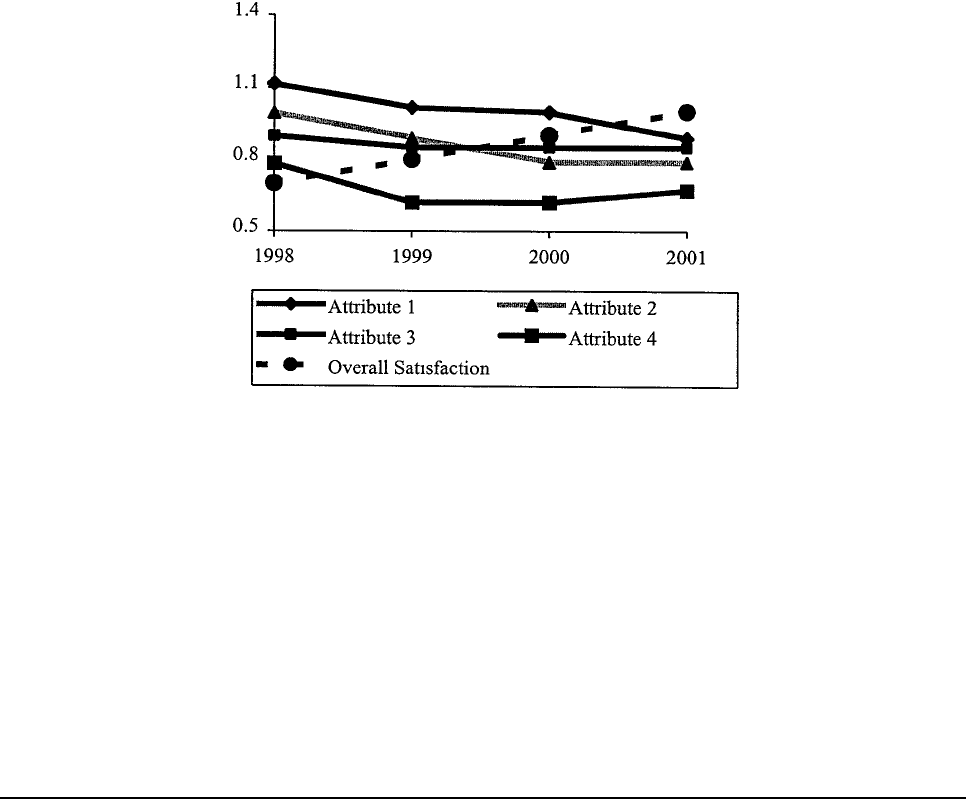

The end result is service quality attribute tracking from the customer's perspective, as shown in Chart

6.1. This tracking information is crucial for developing appropriate, and sufficiently targeted, transit

agency performance measures. It also provides a means for evaluating the specific impacts of planned

agency actions over time.

Chart 6.1

Example

Overall Satisfaction and Attribute Impact Score Tracking

This page left intentionally blank.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality 29

CHAPTER 7. QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH DESIGN

7A. Overview

There are two primary requisites of any market research process:

1. As we have discussed, the analytical plan must be sufficiently powerful to produce

results that are both useful and statistically valid and, concomitantly,

2. Sampling plans and data collection procedures must assure the reliability of the input

data.

The 1996 two-part

Travel Survey Manual

prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. (with Barton

Aschman Associates) for the U.S. Department of Transportation and the U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency is a primary source and reference document for research methods as they apply to transit

customer surveys.

In relation to prerequisite #1 above, as we have explained, both quadrant analysis and factor analysis

combined with multiple regression analysis, can be unreliable in producing results that are sufficient

foundations for transit agency actions. Depending on final collected sample sizes, these approaches can

also end up being statistically unreliable for transit subgroup markets. Other industries such as

automotive, health care, and financial services have learned from hard experience that these

multivariate analysis approaches are often best used as added value analytical explorations, which may

add benefit to predictable findings.

Prerequisite #2 stipulates that, for the analytical results to be both useful and valid, the data on which it

is based must have been collected in a way that minimizes both sampling errors and non-sampling

errors and biases. (For a full discussion of these issues the reader is referred to Section 5.0 of the above

referenced

Travel Survey Manual.

) Essentially, increasing sample size is the primary means of reducing

sampling error; while non-sampling error is reduced by ensuring that the sample collected is fully

representative of the population of transit riders.

A major problem for most initial Customer Satisfaction/Service Quality Benchmark Surveys (and our