This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau

of Economic Research

Volume Title: Monetary Policy Rules

Volume Author/Editor: John B. Taylor, editor

Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Volume ISBN: 0-226-79124-6

Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/tayl99-1

Publication Date: January 1999

Chapter Title: A Historical Analysis of Monetary Policy Rules

Chapter Author: John B. Taylor

Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c7419

Chapter pages in book: (p. 319 - 348)

7

A Historical Analysis

of

Monetary Policy Rules

John

B.

Taylor

This paper examines several eras and episodes of

U.S.

monetary history from

the perspective of recent research on monetary policy rules.’ It explores the

timing and the political economic reasons for changes in monetary policy from

one policy rule to another, and it examines the effects of different monetary

policy rules on the economy. The paper also defines-using current infonna-

tion and the vantage point

of

history-a quantitative measure of the size of

past mistakes in monetary policy. And it examines the effects that these mis-

takes may have had on the economy. The history of these changes and mistakes

is relevant for monetary policy today because it provides evidence about the

effectiveness of different monetary policy rules.

The

Rationale for a Historical Approach

Studying monetary history

is,

of

course, not the only way to evaluate mone-

tary policy. Another approach is to build structural models of the economy and

then simulate the models stochastically with different monetary policy rules.

John B. Taylor is the Mary and Robert Raymond Professor of Economics at Stanford University

and a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The author thanks Lawrence Christiano, Richard Clarida, Milton Friedman, conference partici-

pants, and participants in seminars at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Lehigh University,

and Wayne State University for

very

helpful comments.

1.

In this paper a monetary policy

rule

is defined as a description-expressed algebraically,

numerically, graphically-of how the

instruments

of policy, such as the monetary base or the

federal funds rate, change in response to economic variables. Thus a constant growth rate rule for

the

monetary base

is an example of a policy rule, as is a contingency plan for the monetary base.

A description of how the

federal funds rate

is adjusted in response to inflation or real

GDP

is

another example

of

a policy rule. A policy rule can be normative or descriptive. According to this

definition, a policy rule can be the outcome of many different institutional arrangements for mone-

tary policy, including gold standard arrangements in which there is no central bank. The term

regime

is usually used more broadly than the specific definition of a policy rule used in this paper.

E.g., the term “policy regime”

is

used by Bordo and Schwartz

(1999)

to mean people’s expecta-

tions as well as the institutional arrangements.

319

320

John

B.

Taylor

A model economy provides information about how the actual economy would

operate with different policies. One monetary policy rule is better than another

monetary policy rule if it results in better economic performance according to

some criterion such as inflation or the variability of inflation and output.* This

model-based approach has led to practical proposals for monetary policy rules

(see Taylor 1993a), and the same approach is now leading to new or refined

proposals. The model-based approach has benefited greatly from advances in

computers, solution algorithms, and economic theories

of

how people forecast

the future and how market prices and wages adjust to changing circumstances

over time.

Despite these advances, the model-based approach cannot be the sole

grounds for making policy decisions.

No

monetary theory is a completely reli-

able guide to the future, and certain aspects of the current models are novel,

especially the incorporation of rational expectations with wage and price rigid-

ities. Hence, the historical approach to monetary policy evaluation is a neces-

sary complement to the model-based approach. By focusing on particular epi-

sodes or case studies one may get a better sense about how a policy rule might

work in practice. Big historical changes in policy rules-even if they evolve

slowly-allow one to separate policy effects from other influences on the

economy. Because models, even simple ones, are viewed as black boxes, the

historical approach may be more convincing to

policy maker^.^

Moreover, case

studies are useful for judging how much discretion is appropriate when a pol-

icy rule

is

being used as a guideline for central bank decisions.

Overview

I

begin the analysis with a description of the framework

I

use to examine

the history of monetary policy rules.

I

focus entirely on interest rate rules in

which the short-term interest rate instrument of the central bank is adjusted in

response to the state of the economy. When analyzing monetary policy using

the concept

of

a policy rule, one must be careful to distinguish between instru-

ment changes due to “shifts” in the policy rule and instrument changes due

to

“movements along” the policy rule. To make this distinction,

I

assume a partic-

ular functional form for the policy rule. The functional form

is

the one

I

sug-

gested several years ago as a normative recommendation for the Federal Re-

serve (Taylor 1993a). According to this policy rule, the federal funds rate is

adjusted by specific numerical amounts in response to changes in inflation and

2.

Examples of this approach include the econometric policy evaluation research in Taylor

(1979, 1993b), McCallum (1988), Bryant, Hooper, and Mann (1993), Sims and Zha (1995),

Ber-

nanke,

Gertler,

and Watson (1997), Brayton et al. (1997), and many of the papers in this confer-

ence volume.

3. In fact, the historical approach is frequently used in practice by policymakers, although the

time periods are

so

short

that it may seem like real-time learning. If policymakers were using a

particular type of policy and found that it led to an increase in inflation,

or

a recession,

or

a

slowdown in growth, then they probably would, at the next opportunity, change the policy, learning

from the unfavorable experience.

321

A

Historical Analysis

of

Monetary Policy

Rules

real

GDP.

This functional form with these numerical responses describes the

actual policy actions of the Federal Reserve fairly accurately in recent years,

but in this paper

I

look at earlier periods when the numerical responses were

different and examine whether economic performance of the economy was any

different.

I examine several long time periods in

U.S.

monetary history, one around

the end of the nineteenth century and the others closer to the end of the twenti-

eth century. The earlier period from

1879

to

1914

is the classical international

gold standard era; it includes

11

business cycles, a long deflation, and a long

inflation. The later period from

1955

to

1997

encompasses the fixed exchange

rate era of Bretton Woods and the modem flexible exchange rate era, including

7

business cycles, an inflation, a sharp disinflation, and the recent 15-year

stretch of relatively low inflation and macroeconomic stability. The change in

the policy rule over these periods has been dramatic. The type of policy rule

that describes Federal Reserve policy actions in the past

10

or

15

years is far

different from the ones implied by the gold standard, by Bretton Woods, or by

the early part of the flexible exchange rate era.

It turns out that macroeconomic performance-in particular, the volatility

of inflation and real output-was also quite different with the different policy

rules. Moreover, the historical comparison gives a clear ranking of the pol-

icy rules in terms of economic performance.

To

ensure that this ranking is

not spurious-reflecting reverse causation, for example-I

try

to examine the

reasons for the policy changes.

I

think these changes are best understood as

the result of an evolutionary learning process in which the Federal Reserve-

from the day it began operations in

1914

to today-has searched for policy

rules to guide monetary policy decisions and has changed policy rules as it

has learned.

I then consider three specific episodes when “policy mistakes” were made.

I

define policy mistakes as big departures from two

baseline

monetary policy

rules that both this historical analysis and earlier models-based analysis sug-

gest would have been good policy rules. According to this definition, policy

mistakes include

(1)

excessive monetary tightness in the early

1960s,

(2)

ex-

cessive monetary ease and the resulting inflation of the late

1960s

and

1970s,

and

(3)

excessive monetary tightness of the early

1980s.

I

contrast these three

episodes with the more recent period of low inflation and macroeconomic sta-

bility during which monetary policy has followed the baseline policy rule more

closely.

I

think the analysis of these three episodes and the study of the gradual

evolution of the parameters of monetary policy rules from one monetary era to

the next gives evidence in favor of the view that a monetary policy that stays

close to the baseline policy rules would be a good p01icy.~

4.

Judd and Trehan (1995) first brought attention to

the

difference between the interest rates

implied by the policy rule

I

suggested in Taylor (1993a) and actual interest rates in

the

late 1960s

and 1970s during the Great Inflation.

322

John

B.

Taylor

7.1

From the Quantity Equation

of

Money to a Monetary Policy Rule

The quantity equation of money

(MV

=

PY)

provided the analytical frame-

work with which Friedman and Schwartz (1963) studied monetary history in

their comprehensive study of the United States from the Civil War to 1960.

As

they state in the first sentence of their study, “This book is about the stock

of

money in the United States.”

A

higher stock of money

(M)

would lead to a

higher price level

(P)

other things-namely, real output

(Y)

and velocity

(V)-

equal, as they showed by careful study of episode after episode. In each epi-

sode they demonstrated why the money stock increased (gold discoveries

in

the nineteenth century, for example)

or

decreased (policy mistakes by the Fed-

eral Reserve in the twentieth century, for example), and they focused on the

roles of particular individuals such as William Jennings Bryan and Benjamin

Strong. But the quantity equation of money transcended any individual or insti-

tution: with the right interpretation it was useful both for the gold standard and

the greenback period and whether a central bank existed or not.

The idea in this paper is to try to step back from the debates about current

policy, as Friedman and Schwartz (1963) did, and examine the history of mon-

etary policy via an analytical framework. However,

I

want to focus on the

short-term interest rate side of monetary policy rather than on the money stock

side. Hence,

I

need a different equation. Instead of the quantity equation

I

use

an equation-called a monetary policy rule-in which the short-term inter-

est rate is a function of the inflation rate and real

GDP.5

The policy rule is, of

course, quite different from the quantity equation of money, but it is closely

connected to the quantity equation. In fact, it can be easily derived from the

quantity equation.

To

a person thinking about current policy, the quantity equa-

tion might seem like

an

indirect route to a interest rate rule for monetary policy,

but it is a useful route for the study of monetary history.

7.1.1

Deriving a Monetary Policy Rule from the Quantity Equation

First imagine that the money supply is either fixed or growing at a constant

rate. We know that velocity depends on the interest rate

(r)

and on real output

or income

(Y).

Substituting for

V

in the quantity equation one thus gets a rela-

tionship between the interest rate

(r),

the price level

(P),

and real output

(Y).

If we isolate the interest rate

(r)

on the left-hand side of this relationship, we

see a function of two variables: the interest rate as a function of the price level

5.

Two

useful

recent studies have looked at monetary history

from

the vantage point

of

a mone-

tary policy

rule

stated in terms

of

the interest rate instrument rather than a money instrument.

These are Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (1998), who look at several other countries in addition to

the United States, and Judd and Rudebusch (1998), who contrast U.S. monetary policies under

Greenspan, Volker, and Bums. Clarida et al. (1998) show that British participation in the European

Monetary System while Germany was tightening monetary policy led to a suboptimal shift of the

baseline policy

rule

for

the United Kingdom.

Wo

earlier influential studies using the Friedman

and Schwartz (1963) approach to monetary history and policy evaluation are Sargent (1986) and

Romer and Romer (1989).

323

A

Historical

Analysis

of

Monetary

Policy

Rules

and real output. Shifts in this function would occur when either velocity growth

or money growth

shifts.

Note also that such a function relating the interest rate

to the price level and real output will still emerge if the money stock is not

growing at a fixed rate, but rather responds in a systematic way to the interest

rate or to real output; the response

of

money will simply change the parameters

of the relationship.

The functional form of the relationship depends on many factors including

the functional form of the relationship between velocity and the interest rate

and the adjustment time between changes in the interest rate and changes in

velocity. The functional form

I

use is linear in the interest rate and in the loga-

rithms of the price level and real output. I make the latter two variables station-

ary by considering the deviation of real output from a possibly stochastic trend

and by considering the first difference of the log of the price level-or the

inflation rate.

I

also abstract from lags in the response of velocity to interest

rates or income. These assumptions result in the following linear equation:

(1)

r

=

IT

+

gy

+

h(n

-

IT*)

+

rf,

where the variables are

r

=

the short-term interest rate,

IT

=

the inflation rate

(percentage change in

P),

and

y

=

the percentage deviation of real output

(Y)

from trend and the constants are

g,

h,

IT*,

and

rf.

Note that the slope coefficient

on inflation in equation

(1)

is

1

+

h;

thus the two key response coefficients are

g

and

1

+

h.

Note also that the intercept term is

rf

-

hv*.

An interpretation of

the parameters and a rationale for this notation is given below.

7.1.2

Interpreting the Monetary Policy Rule

Focusing now on the functional form for the policy rule in equation

(1),

our

objective is to determine whether the parameters in the policy rule vary across

time periods and to look for differences in economic performance that might

be related to any such variations across time periods. Note how this historical

policy evaluation method is analogous to model-based policy evaluation re-

search in which policy rules (like eq.

[l])

with various parameter values are

placed in a model and simulations

of

the model are examined to see if the

variations in the parameter values make any difference for economic perfor-

mance. Equation

(1)

is useful for this historical analogue of the model-based

approach because it can describe monetary policy in different historical time

periods when there were many different policy regimes. In each regime the

response parameters

g

and

1

+

h

would be expected to differ, though in most

regimes they would be positive. To see this, consider several types of regimes.

Constant

Money

Growth.

We have already seen that the quantity equation with

fixed money growth implies a relationship like equation

(1).

To see that the

parameters

g

and

1

+

h

are positive with fixed money growth consider the

demand for money in which real balances depend negatively on the interest

rate and positively on real output. Then, in the case of fixed money growth, an

324

John

B.

Taylor

increase in inflation would lower

real

money balances and cause the interest

rate to rise: thus higher inflation leads to a higher interest rate.6 Or suppose

that real income rises thus increasing the demand for money; then, with no

adjustment in the supply of money, the interest rate must

rise.

In other words,

the monetary policy rule with positive values for

g

and

1

+

h

provides a good

description of monetary policy in a fixed money growth regime. However, the

monetary policy rule also provides a useful framework in many other situa-

tions.

International Gold Standard.

Important for our historical purposes is that such

a relationship also exists in the case of an international gold standard. The

short-run response

(1

+

h) of the interest rate to the inflation rate in the case

of a gold standard is most easily explained by the specie flow mechanism of

David Hume. If inflation began to rise in the United States compared with

other countries, then a balance-of-payments deficit would occur because

U.S.

goods would become less competitive. Gold would flow out of the United

States to finance the trade deficit; high-powered money growth would decline

and the reduction in the supply of money compared with the demand for

money would put upward pressure on U.S. interest rates. The higher interest

rates and the reduction in demand for U.S. exports would put downward pres-

sure on inflation in the United States.’ Similarly, a reduction in inflation in the

United States would lead to a trade surplus, a gold inflow, an increase in the

money supply, and downward pressure on

U.S.

interest rates.

Fluctuations in real output would also cause interest rates to adjust. Suppose

that there were an increase in real output. The increased demand for money

would put upward pressure on interest rates if the money supply were un-

changed. Amplifying this effect under a gold standard would be an increase

in the trade deficit, which would lead to a gold outflow and a decline in the

money supply.

These interest rate responses would occur with or without a central bank. If

there were a central bank, it could increase the size of the response coefficients

if it played by the gold standard‘s “rules of the game.” Interest rates would be

even more responsive, because a higher price level at home would then bring

about an increase in the “bank rate” as the central bank acted to help alleviate

the price discrepancies. The U.S. Treasury did perform some of the functions

of a central bank during the gold standard period; it even provided liquidity

during some periods of financial panic, though not with much regularity or

predictability. However, there is little evidence that the U.S. Treasury per-

6.

Note that this effect of inflation on the interest rate is a short-term “liquidity effect” rather

than a longer term “Fisherian” or “expected inflation” effect. The expected inflation effect would

occur if

the growth rate of the money supply increased

or

if

7~*

(the target inflation rate in the

policy rule) increased.

7.

Short-term capital flows would of course limit the size of such interest rate changes. One

reason why

U.S.

short-term interest rates did not move by very much in response

to

US.

inflation

fluctuations (as shown below) may have been the mobility

of

capital.

325

A

Historical Analysis

of

Monetary Policy

Rules

formed “rules of the game” functions as the Bank of England did during the

gold standard era.

Leaning against the

Wind. The most straightforward application of equation

(1)

is to situations where the Fed sets short-term interest rates in response to

events in the economy. Then equation

(1)

is a central bank interest rate reaction

function describing how the Federal Reserve takes actions in the money market

that cause the interest rate to change in response

to

changes in inflation and

real GDP. For example, if the Fed “leaned against the wind,” easing money

market conditions in response to lower inflation or declines in production and

tightening money market conditions in response to higher inflation or increases

in production, then one would expect

g

and

1

+

h

in equation

(1)

to be positive.

However, “leaning against the wind” policies have not usually been stated

quantitatively; thus the size of the parameters could be very small or very large

and would not necessarily lead to good economic performance.

Monetary Policy Rule as a Guideline

or

Explicit

Formula.

Finally, equation

(1)

could represent a guideline, or even a strict formula, for the central bank to

follow when making monetary policy decisions.

As

in the previous paragraph,

decisions would be cast in terms of whether the Fed would raise or lower the

short-term interest rate. But equation

(1)

would serve as a normative guide to

these decisions, not simply a description

of

them after the fact.

If

the policy

rule called for increasing the interest rate, for example, then the Federal Open

Market Committee (FOMC) would instruct the trading desk to make open mar-

ket sales and thereby adjust the money supply appropriately to bring about this

increase. In this case, the parameters of equation

(1)

have a natural interpreta-

tion:

T*

is the central bank‘s target inflation rate,

rf

is the central bank’s esti-

mate of the equilibrium real rate of interest, and

h

is the amount by which the

Fed raises the ex post real interest rate

(I

-

T)

in response to

an

increase in

inflation. In the case that

g

=

0.5,

h

=

0.5,

T*

=

2,

and

rf

=

2,

equation

(1)

is

precisely the form of the policy rule I suggested in Taylor (1993a). Others have

suggested that

g

should be larger, perhaps closer

to

one (see Brayton et al.

1997). Thus an alternative baseline rule considered below sets

g

=

1.

These

are the parameter values that define the baseline policy rules for historical com-

parisons in this paper.

7.1.3

To

summarize, a constant growth rate of the money stock, an international

gold standard, an informal policy of leaning against the wind, and an explicit

quantitative policy of interest rate setting all will tend to generate positive re-

sponses

of

the interest rate to changes in inflation or real output, as described

by equation (I). And we expect that

g

and

1

+

h

in equation

(1)

would be

greater than zero in all these situations. However, the magnitude of these

co-

efficients will differ depending on how monetary policy is run.

In the case of the gold standard or a fixed money growth policy, the size of

The Importance of the Size of the Coefficients

326 John

B.

Taylor

the coefficients depends on many features of the economy. Under a gold stan-

dard, the size of the response of the interest rate to an increase in inflation will

depend on the sensitivity of trade flows to international price differences. It

will also depend on the size of the money multiplier, which translates a change

in high-powered money due to a gold outflow into a change in the money

supply. The interest rate elasticity of the demand for money is also a factor.

With a policy that keeps the growth rate of the money stock constant, the

response of the interest rate to an increase in real output will depend on both

the income elasticity of money demand and the interest rate elasticity of money

demand. The higher the interest rate elasticity of money demand (or velocity),

the smaller would be the response of interest rates to an increase

in

output or

inflation.

The size of these coefficients makes a big difference for the effects of policy.

Simulations of economic models indicate, for example, that the coefficient

h

should not be negative; otherwise

1

+

h

will be less than one and the real

interest rate would fall rather than rise when inflation rose. As a result inflation

could be highly volatile. As I show below there is evidence that

h

was negative

during the late

1960s

and

1970s

when inflation rose in the United States.

Hence, policymakers need to be concerned about the size of these coefficients.

A recent example of this concern demonstrates the usefulness of thinking

about monetary history from the perspective of equation

(1).

Consider Alan

Greenspan’s

(1997)

recent analysis of the size of the interest rate response to

real output with a constant money growth rate. In commenting

on

a money

growth strategy, Greenspan reasoned: “Because the velocity of such an aggre-

gate

[Ml]

varies substantially in response to small changes in interest rates,

target ranges for

MI

growth in [the

FOMC’s]

judgement no longer were reli-

able guides for outcomes in nominal spending and inflation. In response to an

unanticipated movement in spending and hence the quantity of money de-

manded, a small variation in interest rates would be sufficient to bring money

back to path but not to correct the deviation in spending”

(1997,4-5).

In

other

words, in Greenspan’s view the interest rate elasticity of velocity is

so

large

that the interest rate would respond by too small an amount to an increase

in output. In terms of equation

(1)

the parameter

g

is too small, according to

Greenspan’s analysis, under a policy that targets the growth rate of

M1.

7.2

The Evolution

of

Monetary Policy Rules in the United States:

From the International Gold Standard to the

1990s

Figures

7.1

and

7.2

illustrate the historical relation between the variables in

equation

(1).

They show the interest rate

(r),

the inflation rate

(n),

and real

GDP

deviations

(y)

during two different time periods:

1880-1914

versus

1955-97.

The upper part of each figure shows real output,

an

estimate of the

trend in real output, and the percentage deviation

of

real output from this trend.

Our focus is on the deviations

of

real output from trend rather than on the

327

A

Historical Analysis

of

Monetary Policy Rules

r

250

80

85

90

95

00

05

10

Fig.

7.1

The

1880-1914

period: short-term interest rate, inflation,

and real output

Source;

Quarterly data

on

real

GNP,

the

GNP

deflator, and the commercial paper rate are from

Balke and Gordon

(1986).

Real output data are measured in billions

of

1972

dollars and the trend

is

created with the Hodrick-F’rescott filter.

average output growth rate in the two periods. The lower part

of

each figure

shows a short-term interest rate (the commercial paper rate in the earlier period

and the federal funds rate in the later period) and the inflation rate (a four-

quarter average

of

the percentage change in the

GDP

deflator). Recall that the

earlier period coincides with the classical international gold standard, starting

with the end of the greenback era when the United States restored gold convert-

ibility and ending with the suspension

of

convertibility by many countries at

the start

of

World War

I.

7.2.1 Changes in Cyclical Stability

The contrast between the display of the data in figure

7.1

and figure

7.2

is

striking. First, note that business cycles occur much more frequently in the

earlier period (fig.

7.1)

than in the later period (fig.

7.2),

and the size

of

the

328 John

B.

Taylor

Trend

GDP

(HP

Fil

55

60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95

I

15

I

I

!!i

!

Federal

Funds

Rate

10

-

01

I I

I

I I

I

I

55 60 65

70

75

80 85 90 95

Fig. 7.2 The 1955-97 period: short-term interest rate, inflation, and real output

Source:

Quarterly data

are

from the DRI data bank. Real output is measured

in

billions

of 1992

dollars and the trend

is

created with the Hodrick-Prescott filter.

fluctuations of inflation and real output is much greater. From

1880

to

1897

there was deflation on average. From

1897

to

1914

prices rose on average. But

throughout the whole period there were large fluctuations around these aver-

ages. The later period is not of course uniform in its macroeconomic perfor-

mance. The late

1960s

and

1970s

saw

a

large and persistent swing in inflation,

while the years since the

mid-1980s

have seen much greater macroeconomic

stability.

One way to highlight the greater macroeconomic turbulence in the earlier

years is to consider the period from

1890

to

1897,

which saw three recessions.

These years were

so

bad that they were called the “Disturbed Years” by Fried-

man and Schwartz

(1963).

One cannot avoid the temptation to contrast

1890-

97

with

1990-97.

If we had the same business cycle experience in the later years,

we would have had a recession in

1990-91

slightly longer than the one we

actually had. But we would have

also

had another recession starting in January

1993

just as President Clinton started in office and yet another recession start-

329

A Historical Analysis

of

Monetary

Policy

Rules

ing in 1995. The trough of that third recession of the 1990s would have occured

in

June of 1997. Even allowing for measurement error due to overemphasis of

goods versus services in the earlier period, it appears that the earlier period

was less stable.8 To be sure, if one ignores the long swing of average deflation

and then inflation, the fluctuations in inflation were much less persistent during

the gold standard period, as emphasized in a comparison by McKinnon and

Ohno

(1997, 164-71). But this long-term deflation and inflation should count

as part of the sub-par inflation performance during this period.

7.2.2 Changes in Interest Rate Responses

A

second, and even more striking, contrast between the two periods is the

response of the short-term interest rate to inflation and output. While the short-

term interest rate is procyclical during both the earlier period and the later

period, the elasticity of its response to output is clearly much less in the earlier

period than in the later period. Cagan (1971) first pointed out the increased

cyclical sensitivity of the interest rate to real output fluctuations, and it is more

evident now than ever. The short-term interest rate is also much less responsive

to fluctuations in the inflation rate in the earlier period. It appears that the gold

standard did lead to a positive response of interest rates to real output and

inflation, but this response is much less than for the monetary policy in the

post-World War I1 period.

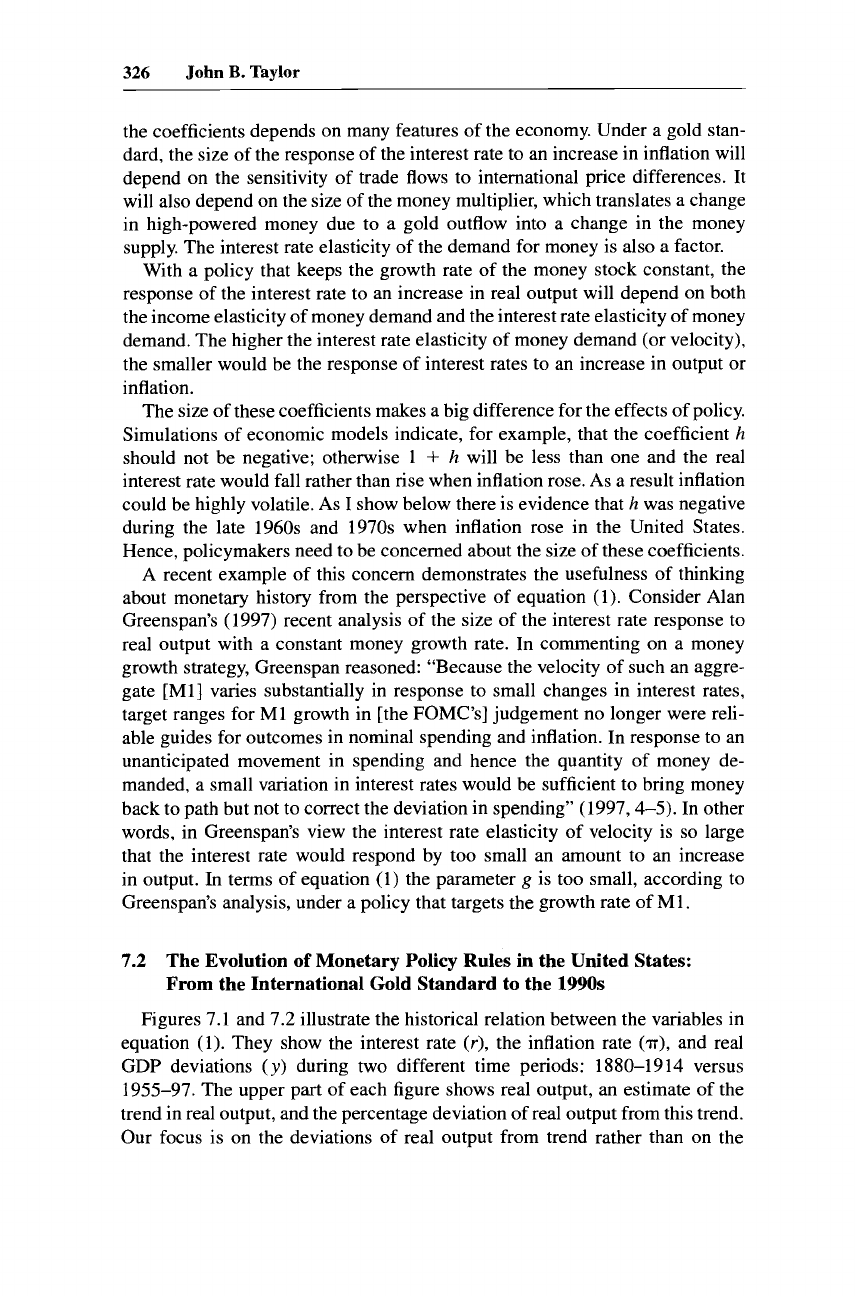

The huge size of these differences is readily visible in figures 7.1 and 7.2.

But

to

see how the responses changed during the post-World War I1 period it

is necessary to

go

beyond these time-series charts. Some numerical informa-

tion about the size of these differences is provided in table 7.

l.

The table shows

least squares estimates of the coefficients on real output (the parameter

g

in

eq.

[

11)

and the inflation rate (the parameter 1

+

h

in eq.

[

11)

for different

time

period^.^

The far right-hand column shows the results for each of the two full periods.

Observe that the estimated values of

g

and 1

+

h

are about

10

times larger in

the Bretton Woods and post-Bretton Woods eras than in the international gold

standard era. It is clear that the gold standard implied much smaller response

coefficients for the interest rate than Federal Reserve policy has implied in

later periods.

8.

Romer

(1986)

demonstrated that biases in the pre-World War

I

data tend

to

overestimate the

volatility in comparison with later periods.

9.

As

explained above this equation is actually a reduced form

of

several structural equations,

especially in

the

gold standard and Bretton Woods periods.

I

have purposely tried to keep the

statistical equations as simple as the theoretical policy rule in

eq.

(1).

No

attempt has been made

to correct the estimates for serial correlation

of

the errors in the equation.

I

want to allow for the

possibility that monetary policy mistakes are serially correlated in ways not necessarily described

by simple time-series models. In fact, this serial correlation is very large, especially in the gold

standard period when

the

equations fit very poorly. Hence, the “t-statistics” in parentheses are not

useful

for hypothesis testing.

See

Christiano, Eichenbaum, and Evans (1997) for a comprehensive

analysis of estimation and identification issues in the case of reaction functions.

330

John

B.

Taylor

Table

7.1

Monetary Policy Rules: Descriptive Statistics

International Gold Standard Era

1879:l-91:4 1897: 1-1914:4 1879: 1-1914:4

Variable Coefficient Coefficient Coefficient

Constant 6.458 (70.5) 5.519 (47.3) 5.984 (75.0)

71

0.019 (1.01) 0.034 (1.03) 0.006 (0.32)

Y

0.059 (2.28) 0.038 (1.89) 0.034

(1.52)

R2

0.15 0.07 0.02

Bretton Woods and Post-Bretton Woods

Eras

1960:l-79:4 1987:l-97:3 1954: 1-97:3

Coefficient Coefficient Coefficient

Constant 2.045 (6.34) 1.174 (2.35) 1.721 (5.15)

7r

0.813 (12.9)

1.533 (9.71) 1.101 (15.1)

V

0.252 (4.93) 0.765 (8.22) 0.329 (3.16)

R2

0.70 0.83 0.58

Note;

These are ordinary least squares estimates of the coefficients of the variables in eq. (I).

The

left-hand-side variable

(r)

is measured by the commercial paper rate for the years 1879-1914 and

by the federal funds rate for the years 1954-97. The variable

T

is measured by the average inflation

rate over four quarters, and the variable

y

is

measured by

the

percentage deviation of real output

from

a

trend. Numbers in parentheses are ratios of coefficients to standard errors. See

figs.

7.1 and

7.2 for data sources.

Note also that the size of these coefficients has increased gradually over

time. Compared with the

1960s

and

1970s

the coefficients on real output tri-

pled in size by the

1987-97

period while the coefficient on inflation doubled

in size. They are now close to the values of the rule

I

suggested in Taylor

(1993a).

Hence, when viewed over the past century we have seen an evolution

of

the monetary policy rule as

I

have defined and characterized it empirically

here. The monetary policy rule had very low interest rate responses during the

gold standard era. It had higher responses during the

1960s

and the

1970s,

and

it had still higher responses in the late

1980s

and

1990s.

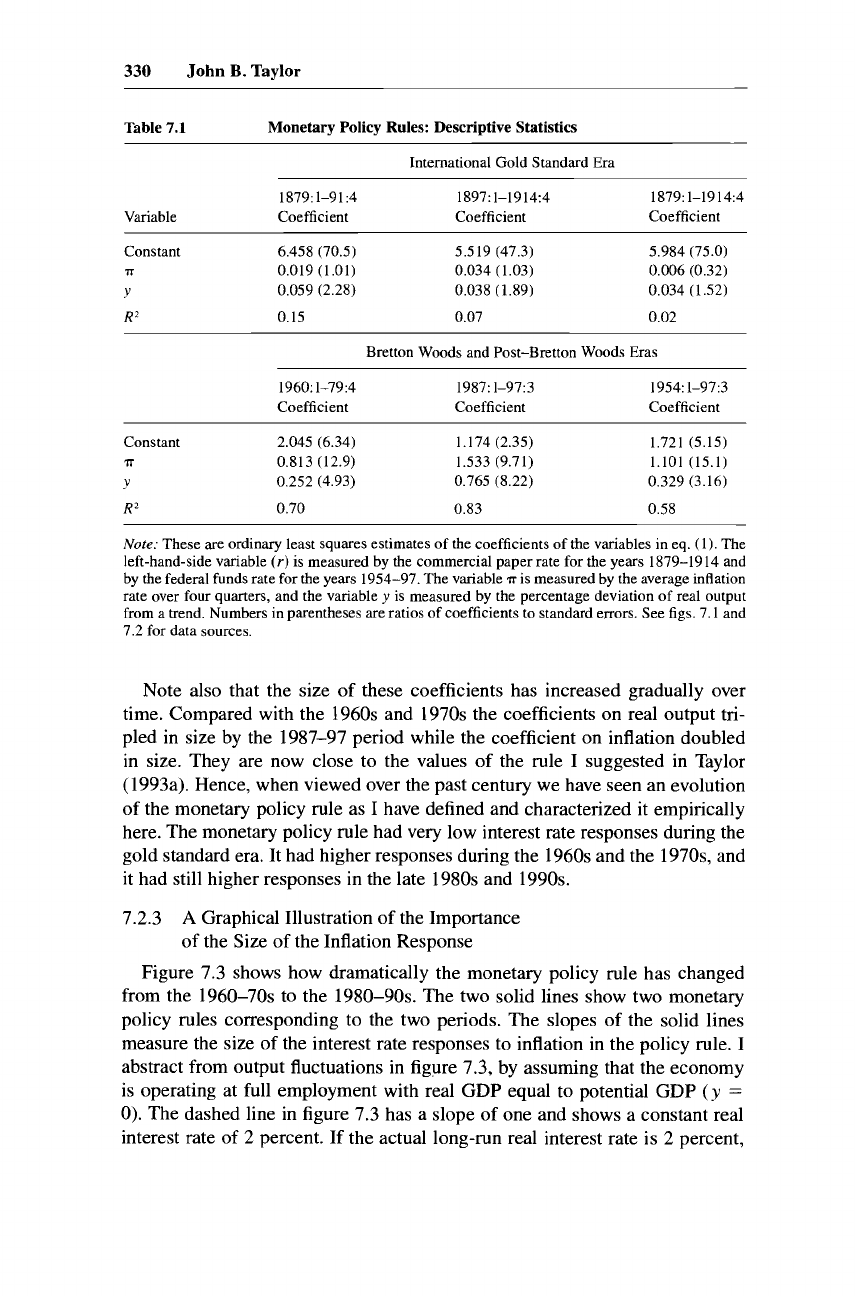

7.2.3

A

Graphical Illustration of the Importance

of the Size

of

the Inflation Response

Figure

7.3

shows how dramatically the monetary policy rule has changed

from the

1960-70s

to the

1980-90s.

The two solid lines show two monetary

policy rules corresponding to the two periods. The slopes of the solid lines

measure the size of the interest rate responses to inflation in the policy rule.

I

abstract from output fluctuations in figure

7.3,

by assuming that the economy

is operating at full employment with real

GDP

equal to potential GDP

(y

=

0).

The dashed line in figure

7.3

has a slope of one and shows a constant real

interest rate

of

2

percent.

If

the actual long-run real interest rate is

2

percent,

331

A Historical Analysis

of

Monetary

Policy

Rules

5

Interest Rate

4

3

2

1

0

Monetary Policy

Rule

(1

987-1 997)

\

/

//-

Real rate equals interest

two

percent

Monetary Policy

Rule

(1

960-1

979)

/

I

I

I

1

I

I

1

2

3

4

5

Inflation Rate

Fig.

7.3

Two

estimated monetary policy

rules:

1960-79 versus 1987-97

then the intersection of the dashed line and the policy rule line gives the long-

run average inflation rate.

Observe that the slope of the policy rule has gone from below one to above

one.

A

slope below one would lead to poor economic performance according

to

variety of models. With the slope less than one, an increase in inflation

would bring about a

decrease

in the real interest rate. This would increase de-

mand and add to upward pressures on inflation. This is exactly the wrong pol-

icy response to an increase in inflation because it would lead to ever increasing

inflation. In contrast, if the slope

of

the policy rule were greater than one, an

increase in inflation would bring about an

increase

in the real interest rate,

which would be stabilizing.

These theoretical arguments are illustrated in figure 7.3. For a long-run equi-

librium, we must be at the intersection of the policy rule line and the dashed

line representing the long-run equilibrium real interest rate. If the slope of the

policy rule line is greater than one, higher inflation leads to higher real interest

rates and the inflation rate converges to an equilibrium at the intersection of

the policy rule line and the dashed real interest rate line. For example, if the

equilibrium real interest rate is

2

percent as in figure 7.3, the equilibrium infla-

tion rate is about

1.5

percent for the recent, more steeply sloped, monetary

policy rule in figure 7.3. However, if the slope

of

the policy rule line is less

332

John

B.

Taylor

than one, higher inflation leads to a lower real interest rate, which leads to even

higher inflation; the inflation rate is unstable and would not converge to an

equilibrium. In sum, figure 7.3 shows why the inflation rate would be more

stable

in

the 1987-97 period than in the 1960-79 period.

7.3

Effects

of

the Different Policy Rules

on

Macroeconomic Stability

Can one draw a connection between the different policy rules and the eco-

nomic performance with those policy rules? In particular, within the range

of

policy rules we have seen, is it true that more responsive policy rules lead to

greater economic stability? Making such a connection is complicated by other

factors, such as oil shocks and fiscal shocks, but it is at least instructive to try.

7.3.1

Three Monetary Eras

As

the analysis summarized in table 7.1 indicates, three eras of

U.S.

mone-

tary history can be clearly distinguished by big differences in the degree of

responsiveness of short-term interest rates in the monetary policy rule.

First, during the period from about 1879 to about 1914 short-term interest

rates were very unresponsive to fluctuations in inflation and real output. Sec-

ond, during the period from about 1960 to 1979 short-term interest rates were

more responsive, but still small in the sense that the response of the nominal

interest rate to changes in inflation was less than one. Third, during the period

from about 1986 to 1997 the nominal interest rate was much more responsive

to both inflation and real output fluctuations.

These three eras can also be distinguished in terms of overall economic sta-

bility. Of the three, there is no question that the third had the greatest degree

of economic stability. Figure 7.1 shows that both inflation and real output had

smaller fluctuations during this period. The period contains both the first and

second longest peacetime expansions in

U.S.

history. Moreover, inflation was

low and stable. And, of course, this is the period in which the monetary policy

rule had the largest reaction coefficients, giving support to model-based re-

search that this was a better policy rule than those implied by the two earlier

periods.

The relative ranking of the first and second periods is more ambiguous. Real

output and inflation fluctuations were larger in the earlier period. But while

inflation was more variable, there was much less persistence of inflation during

the gold standard than in the late 1960s and 1970s. However, the different

exchange rate regimes are another monetary factor that must be taken into

account.

It

was the gold standard that kept the long-run inflation rate

so

stable

in the earlier period. Bretton Woods may have provided a similar constraint on

inflation during the early 1960s, but as

U.S.

monetary policy mistakenly be-

came too easy, it was not inflation that collapsed, it was the Bretton Woods

system. And after the end

of

Bretton Woods this external constraint on inflation

was removed. With the double whammy of the loss of an external constraint

333

A

Historical Analysis

of

Monetary Policy Rules

and an inadequately responsive monetary policy rule in place, the inevitable

result was the Great Inflation.

If one properly controls for the beneficial external influences of the gold

standard on long-run inflation during the 1879-1914 period, one obtains an un-

ambiguous correlation between monetary policy rule and macroeconomic sta-

bility. The most economically stable period was the one with the most respon-

sive policy rule. The least economically stable (again adjusting for the gold

standard effects) was the one with the least responsive policy rule. The late

1960s and 1970s

also

rank lower than the most recent period in terms of eco-

nomic stability and had a less responsive monetary policy rule.

7.3.2

In any correlation analysis between economic policy and economic out-

comes there is the possibility of reverse causation. Could the lower respon-

siveness of interest rates in the two earlier periods compared with the later

period have been caused by the greater volatility of inflation and real output?

If one examines the history of changes in the monetary policy rule I think it

becomes clear that the answer is no. The evolution of the monetary policy rule

is best understood as a gradual process

of

the Federal Reserve learning how to

conduct monetary policy. This learning occurred through research by the staff

at the Fed, through the criticism of monetary economists outside the Fed,

through observation of central bank behavior in other countries, and through

direct personal experience of members of the FOMC. And, of course, there

were steps backward as well as fonvard.'O

This learning process occurred as the United States moved further and fur-

ther away from the classical international gold standard. Under the gold stan-

dard, increases and decreases in short-term interest rates were explained by the

interaction of the quantity of money supplied (determined by high-powered

money through the inflow and outflow of gold) and the quantity of money

demanded (which rose and fell as inflation and output rose and fell). A greater

response of the short-term interest rate to rising or falling price levels and to

rising or falling output would probably have reduced the shorter run variability

of inflation and output. For example, lower interest rates during the start of the

deflation period may have prevented the deflation. But because of the fixed

exchange rate feature of the gold standard, the

U.S.

inflation rate was con-

strained to be close to the inflation rates of other gold standard countries; the

degree

of

closeness depended on the size and the duration

of

deviations from

purchasing power parity.

The Federal Reserve started operations at the same time as the classical gold

standard ended: 1914. From the

start

there was therefore uncertainty and dis-

Explaining the Changes in the Policy Rules

10.

If

economists' research on the existence of a long-run trade-off between inflation and unem-

ployment helped lead to the Great Inflation in the 1970s, then this research should be counted as

a step backward.

The

effect of economic research and other factors that may have led to the Great

Inflation

are

discussed in De Long (1997) and in

my

comment on De Long's paper.

334

John

B.

Taylor

agreement about how monetary policy should be conducted without the con-

straints of the gold standard and fixed exchange rates. The Federal Reserve Act

indicated that currency-best interpreted now as the monetary base

or

high-

powered money-was to be elastically provided. But how was the Fed to deter-

mine the degree of this elasticity?

The original idea was that two factors-each pulling in an opposite direc-

tion-were to be balanced out. One was the gold standard itself; with a gold

reserve requirement limiting the amount of Federal Reserve liabilities, the sup-

ply of money was limited. This was a long-run constraint

on

the supply of

money; it worked through gold inflows and gold outflows and the gradual ad-

justment of the

U.S.

price level compared with foreign price levels. The other

factor, which worked more quickly, was “real bills” or “needs of trade” doc-

trine under which the supply of money was to be created in sufficient amounts

to meet the demand for money. Clearly, the needs-of-trade criterion was not

effective on its own because it did not put a limit

on

the amount of money

creation. Therefore, with the suspension of the gold standard and with the real

bills criterion ineffective in determining the supply of money, the Federal Re-

serve began operations with no criteria for determining the appropriate amount

of money to supply. Hence, ever since this uncertain beginning, the Fed has

been searching for such criteria. From the perspective of this paper, we can

think of the Fed as searching for a good monetary policy rule.

This search is evident in many Federal Reserve reports. Early on, the idea

of “leaning against the wind” was discussed as a counterbalance to the needs-

of-trade criterion. For example, the Fed’s annual report for 1923 stated that “it

is the business of the [Federal] Reserve system to work against extremes either

of deflation or inflation and not merely to adapt itself passively to the ups and

downs of business” (quoted in Friedman and Schwartz 1963, 253). But there

was

no

agreement about how much leaning against the wind there should be.

As

discussed above, leaning against the wind would result in a policy rule of

the type in equation

(1),

but the parameters of the policy rule could be far from

optimal. That the Fed was unable throughout the interwar period to find an

effective policy rule for conducting monetary policy is evidenced by the disas-

trous economic performance during the Great Depression when money growth

fell dramatically.

The search for a monetary policy rule was postponed during World War

I1

and in the postwar period by the overriding objective of keeping Treasury

borrowing costs down. (Effectively the Fed set

g

=

0

and

h

=

-1

so

that

r

was a constant stipulated by the

US.

Treasury.) However, after the 1951 Trea-

sury-Federal Reserve Accord, the Fed once again needed a policy rule for

conducting monetary policy. Leaning against the wind-now articulated by

William McChesney Martin-again became a guideline for short-run deci-

sions about changes in the money stock. But the idea was still very vague. As

stated by Friedman and Schwartz (1963) in discussing the mid-1950s when

William McChesney Martin was chairman, “There was essentially no discus-

335

A

Historical Analysis

of

Monetary

Policy

Rules

sion of how to determine which way the relevant wind was blowing.

.

.

.

Nei-

ther was there any discussion of when to start leaning against the wind.

.

. .

There was more comment, but hardly any of it specific about how hard to lean

against the wind”

(63 1-32).

The experience

of

new board member Sherman Maisel indicates that the

search was still going on

10

years later in the

mid-1960s.

According to Maisel

in

his candid memoirs, “After being on the Board for eight months and at-

tending twelve open market meetings,

I

began to realize how far

I

was from

understanding the theory the Fed used to make monetary policy.

.

.

.

Nowhere

did

I

find an account of how monetary policy was made or how it operated”

(1973, 77).

Maisel was particularly concerned about various money market

conditions indexes such as free reserves that came up in Fed deliberations,

because of the difficulty of measuring the impact of these changes on the econ-

omy. He states, “Money market conditions cannot measure the degree to which

markets should be tightened or for how long restraint should be retained”

(82).

And when referring to a decision to raise the short-term interest rate in

1965,

he states, “It became increasingly clear that an inflationary boom was getting

underway and that monetary policy should have been working to curb it”

(81).

However, he argued that the actions taken to raise interest rates were insuffi-

cient to curb the inflation. In retrospect he was correct. Interest rates did not

go

high enough. With no quantitative measure of how high interest rates should

go,

the chance of not raising them high enough was great.

The increased emphasis on money growth in the

1970s

played a very useful

role in clarifying the serious problems

of

interest rate setting without any quan-

titative guidelines. And money growth targets had a very useful role in the

disinflation of the

1979-81

period because it was clear that interest rates would

have to rise by large amounts as the Fed lowered the growth rate of the money

supply. But after the disinflation was over, money growth targets again receded

to being a longer run consideration in Federal Reserve operations as the de-

mand for money appeared to be less stable. Moreover, as noted earlier, ac-

cording to Greenspan’s

(1 997)

analysis, keeping money growth constant does

not give sufficient response of interest rates to inflation or real output when the

aim is to keep inflation low and steady.

The importance

of

having a policy rule to guide policy became even more

important when the Bretton Woods system fell apart in the early

1970s.

Until

then the long-run constraints on monetary policy were similar to those of the

international gold standard.

If

the Fed did not lean hard enough against the

wind, the higher inflation rate would start to put pressure on the exchange rate

and the Fed would have to raise interest rates to defend the dollar. But without

the dollar to defend, this constraint on monetary policy was lost. After Bretton

Woods ended there was an even greater need for the Fed to develop a monetary

policy rule that was sufficient to contain inflation without the external con-

straint. This need was one of the catalysts for the rational expectations econo-

metric policy evaluation research in the

1970s

and

1980s.

336

John

B.

Taylor

This brief review of the evolution of policy indicates that macroeconomic

events, economic research, and policymakers at the Fed have gradually

brought forth changes in the monetary policy rule in the United States.

I

think

this gradual evolution makes it clear that the causation underlying the negative

correlation between the size of the policy response of interest rates to output

or inflation and the volatility of output or inflation goes from policy to out-

come, not the other way around.

If we apply this learning hypothesis to the changes in the estimated policy

rule described above, it suggests that the Federal Reserve learned over time to

have higher response coefficients in a policy rule like equation

(1).

What led

the Fed to change its policy in such a way that the parameter

h

changed from

a negative number to a positive number? Experience with the Great Inflation

of the

1970s

that resulted from a negative value for

h

may be one explanation.

Academic research on the Phillips curve trade-off and the effects of different

policy rules resulting from the rational expectations revolution may be an-

other.

‘‘

7.4

“Policy Mistakes”: Big Deviations

from

Baseline Policy Rules

The historical analysis thus far in this paper has not assumed that any partic-

ular policy rule was better than the others. However, that was the conclusion

of the analysis: a comparison of policy rules and economic outcomes points to

the rule the Fed has been using in recent years as a better way to run monetary

policy than the way it was run in earlier years. That conclusion of the historical

analysis bolsters the very similar conclusion

of

the model-based research sum-

marized in the introduction to this paper.

Once one has focused on a particular policy rule, however, there is another

way to use history to check whether the policy rule would work well. With a

preferred policy rule in hand, one can look at episodes in the past when the

instrument of policy-the federal funds rate in this case-deviated from the

settings given by the preferred policy rule. We can characterize such deviations

as “policy mistakes” and see if the economy was adversely affected as a result

of

these mistakes.I2

Figures

7.4,

7.5,

and

7.6

summarize the results of this historical “policy

mistake” analysis. They show the actual federal funds rate and the value of the

federal funds rate implied by two policy rules. The gap between the actual

11.

Chari, Christiano, and Eichenbaum

(1998)

argue that the Fed was

too

accommodative to

inflation

(h

was too low) in the

1970s

because high expectations of inflation raised the costs

of

disinflation, rather than because the Fed still had something to learn about the Phillips curve trade-

off

or

about the effects of different policy rules.

I

find

the

learning argument more plausible in

part

because it explains the end of the inflation and the change in the policy

rule.

12.

We

are,

of course, looking at these past episodes with the benefit

of

later research and

experience. The term “mistake” does not necessarily mean that policymakers of the past had the

information to do things differently.

337

A

Historical Analysis

of

Monetary Policy

Rules

Percent

l6

1

Fig.

7.4

Federal funds rate: too high in the early

1960s;

too

low

in the late

1960s

Note:

Rules

1

and

2

are given

by

the monetary policy rule in eq.

(1) with

g

=

0.5

and

1.0,

respec-

tively.

Percent

2o

1

..................................................

75 76 77

78

79

80 81

82

83 84 85 86

Fig.

7.5

Federal funds rate: too

low

in the

1970s;

on track in

1979-81;

too high

in

1982-84

Note:

See note to fig.

7.4.

federal funds rate and the policy rules is a measure

of

the policy mistake. One

of

the monetary policy rules

I

use is the one

I

suggested in Taylor (1993a),

which

is

equation

(1)

with the parameters

g

and

h

equal to

0.5.

This is rule

1

in figures

7.4,7.5,

and 7.6.

As

mentioned above, more recent research has sug-

gested that

g

should be closer to

1.0,

giving a more procyclical interest rate.

This variant is rule

2

in the figures.

338 John

B.

Taylor

l2

1

Rule

2

Percent

\

87

88 89

90

91

92

93 94

95

96

97

Fig.

7.6

Federal funds rate: on track in the late

1980s

and

1990s

Nore:

See

note to

fig. 7.4.

The gap between the actual federal funds rate and the policy rule is particu-

larly large in three episodes shown in figures 7.4 and 7.5, especially

in

compar-

ison with the relatively small gap in the late 1980s and 1990s shown in

fig-

ure 7.6.

The first episode occurred in the early 1960s when the mistake was making

monetary policy too tight. Regardless of whether

g

is 0.5 or 1.0 the actual

federal funds rate is well above the policy rule. The gap between the funds rate

and the baseline policy was between

2

and 3 percentage points and this gap

lasted for about three and a half years.I3

It is interesting to note that Friedman and Schwartz (1963, 617) also con-

cluded that monetary policy was overly restrictive during this period. They cite

several reasons why policy may have been too tight. First, the Fed was con-

cerned about the balance

of

payments and an outflow of gold. Second, in look-

ing back at the previous recovery, it appeared to the Fed that policy had eased

too soon after the recession. What was the result of this policy mistake? The

recovery from the 1960-61 recession was weak and the eventual expansion

was slow for several years from about 1962 to 1965.

In

fact, the economy did

not appear to catch up to its potential until 1965. The New Economics intro-

duced by President Kennedy and his economic advisers was addressed at this

prolonged period with real output below potential.

The second episode started in the late 1960s and continued throughout the

1970s-a mistake with

so

much serial correlation it would pass a unit root test!

In this case the monetary policy mistake was being way too easy.

As

shown in

figures 7.4 and

7.5,

the gap between the funds rate and the baseline policy

13.

With its high output response, rule

2

brings the interest rate below zero

for

several quarters,

so

the interest rate is set to

a

small positive number in the chart.

339

A

Historical Analysis

of

Monetary

Policy

Rules

started growing in the late 1960s. It grew as large as 6 percentage points and

persisted in the 4 to 6 percentage point range until the late 1970s when Paul

Volcker took over as Fed chairman. The excessive ease in policy began well

before the oil price shocks of the 1970s, thus raising doubts that these shocks

were the cause of the 1970s Great Inflation.

What caused this monetary policy mistake? Economic research of the

1960s

suggested that there was a long-run trade-off between inflation and unemploy-

ment; this research probably reduced some of the aversion to inflation by the

Federal Reserve. At the least the belief by some in a long-run Phillips curve

made defending low inflation more difficult at the Fed. Note that the mistake

began well before the Friedman-Phelps hypothesis was put forward. Moreover,

as the quotes from Maisel’s memoirs above make clear, the Fed‘s use of money

market conditions caused them to understate the degree of tightness. De

Long

(1997) argues that the overly expansionary policy was due to a great fear of

unemployment carried over from the Great Depression, though he does not

attempt to explain why this mistake occurred when it did. While the causes of

this mistake may be uncertain, there is little doubt that it was responsible for

bringing on the Great Inflation of the 1970s. In my view this mistake is the

second most serious monetary policy mistake in twentieth-century

US.

his-

tory, the most serious being the Great Depression.

If

a policy closer to the

baseline were followed, the rise in inflation may have been avoided.

The third episode occurred after the disinflation of the early 1980s. The in-

crease in interest rates in 1979 and 1980 was about the right magnitude ac-

cording to either of the policy rules. But both rule 1 and rule 2 indicate that

the funds rate should have been lowered more than it was in the 1982-84 pe-

riod. During this period the interest rate was well above the value implied by

the two policy rules. However, it should be emphasized that this period oc-

curred right after the end of the 1970s inflation, and interest rates higher than

recommended by the policy rules may have been necessary to keep expecta-

tions of inflation from rising and to help establish the credibility of the Fed.

In

effect the Fed was in a transition between policy rules. In my view this period

has less claim to being a “policy mistake” than the other two periods.

7.5

Conclusions

The main conclusions of this paper can be summarized as follows. First,

a

monetary policy rule for the interest rate provides a useful framework with

which to examine

U.S.

monetary history.

It

complements the framework pro-

vided by the quantity equation of money so usefully employed by Friedman

and Schwartz (1963). Second, a monetary policy rule in which the interest rate

responds to inflation and real output is an implication

of

many different mone-

tary systems. Third, the monetary policy rule has changed dramatically over

time in the United States, and these changes are associated with equally dra-

340

John

B.

Taylor

matic changes in economic stability. Fourth,

an

examination of the underlying

reasons for the monetary policy changes indicates that they have caused the

changes in economic outcomes, rather than the reverse. Fifth, a monetary pol-

icy rule in which the interest rate responds to inflation and real output more

aggressively than during the 1960s and 1970s

or

than during the international

gold standard-and more like the late 1980s and 1990s-is a good policy rule.

Sixth, if one defines policy mistakes as deviations from such a good policy

rule, then such mistakes have been associated with either high and prolonged

inflation or drawn-out periods

of

low capacity utilization, much as simple mon-

etary theory would predict.

Overall the results of the historical approach in this paper are quite consis-

tent with the results of the model-based approach to monetary policy evalua-

tion. But in an important sense this paper has only touched the surface; many

other issues could be explored with a historical approach. For example, two

difficult problems with monetary policy rules such as equation (1) have been

mentioned by Alan Greenspan (1997): both potential GDP and the real rate

of

interest are uncertain. Uncertainty about the level

of

potential GDP (and the

natural rate of unemployment) is a problem faced by monetary policymakers

today regardless of whether they use a policy rule for guidance. Looking back

at previous episodes and seeing the results of mismeasuring either potential

GDP or the real rate of interest might help reduce the probability

of

making

the next monetary policy mistake.

References

Balke, Nathan

S.,

and Robert J. Gordon. 1986. Appendix B: Historical data.

In

The

American business cycle: Continuity and change,

ed. Robert

J.

Gordon. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Bernanke, Ben, Mark Gertler, and Mark Watson. 1997. Systematic monetary policy and

the effects

of

oil price shocks.

Brookings Papers

on

EconomicActivity,

no.

1:91-157.

Bordo, Michael

D.,

and Anna J. Schwartz. 1999. Monetary policy regimes and eco-

nomic performance: The historical record.

In

Handbook

of

macroeconomics,

ed.

John B. Taylor and Michael Woodford. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Brayton, Flint, Andrew Levin, Ralph Tryon, and John Williams. 1997. The evolution

of

macro models at the Federal Reserve Board.

Curnegie-Rochester Conference Series

on

Public Policy

47:43-81.

Bryant, Ralph, Peter Hooper, and Catherine Mann. 1993.

Evaluating policy regimes:

New

empirical research in empirical macroeconomics.

Washington, D.C.: Brook-

ings Institution.

Cagan, Phillip. 1971. Changes

in

the cyclical behavior of interest rates.

In

Essays on

interest rates,

ed. Jack M. Guttentag. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chari,

V.

V.,

Lawrence Christiano, and Martin Eichenbaum. 1998. Expectation traps

and discretion.

Journal

of

Economic Theory

81

(2): 462-98.

Christiano, Lawrence J., Martin Eichenbaum, and Charles L. Evans. 1997. Monetary

policy shocks: What have we learned and to what end?

In

Handbook

of

macroeco-

nomics,

ed. John B. Taylor and Michael Woodford. Amsterdam: North Holland.

341

A Historical Analysis

of

Monetary Policy Rules

Clarida, Richard, Jordi Gali, and Mark Gertler. 1998. Monetary policy rules in practice:

Some international evidence.

European Economic Review

42: 1033-67.

De Long,

J. Bradford. 1997. America’s peacetime inflation: The 1970s. In

Reducing

injlation: Motivation and strategy,

ed. Christina D. Romer and David

H.

Romer. Chi-

cago: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, Milton, and Anna Schwartz. 1963.

A monetary history

of

the United States,

1867-1960.

Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Greenspan, Alan. 1997. Remarks at the 15th anniversary conference of the Center for

Economic Policy Research. Stanford University,

5

September.

Judd, John F., and Glenn D. Rudebusch. 1998. Taylor’s rule and the Fed: 1970-1997.

Federal Reserve Bank

of

Sun Francisco Economic Review,

no. 3:3-16.

Judd, John F., and Bharat Trehan. 1995. Has the Fed gotten tougher on inflation?

Fed-

eral Reserve Bank

of

San

Francisco Weekly Letter;

no. 95-13.

Maisel, Sherman J. 1973.

Managing the dollar.

New York: Norton.

McCallum, Bennett. 1988. Robustness properties of a rule

for

monetary policy.

Carne-

gie-Rochester Conference Series

on

Public Policy

29:

173-203.

McKinnon, Ronald I., and Kenichi Ohno. 1997.

Dollar and yen.

Cambridge, Mass.:

MIT Press.

Romer, Christina D. 1986. Is the stabilization of the postwar economy a figment

of

the

data?

American Economic Review

76:3 14-34.

Romer, Christina D., and David Romer. 1989. Does monetary policy matter? A new

test in the spirit of Friedman and Schwartz. In

NBER macroeconomics annual

1989,

ed.

0.

J. Blanchard and

S.

Fischer. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Sargent, Thomas. 1986. The end

of

four big inflations. In

Rational expectations and

inflation,

ed. Thomas Sargent, 40-109. New York: Harper and Row.

Sims, Christopher, and Tao Zha. 1995. Does monetary policy generate recessions? At-

lanta: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Working paper.

Taylor, John B. 1979. Estimation and control of a macroeconomic model with rational

expectations.

Econometrica

47

(5):

1267-86.

.

1993a. Discretion versus policy rules in practice.

Carnegie-Rochester Confer-

ence Series

on

Public Policy

39:195-214.

.

1993b.

Macroeconomic policy in a world economy: From econometric design

to practical application.

New York: Norton.

Comment

Richard H. Clarida

It is a pleasure to discuss this paper by John Taylor. In it, he proposes to use

the Taylor rule as an analytical framework for the interpretation

of

monetary

history, much as Friedman and Schwartz employed the quantity equation.

I

agree with the approach that he is trying to promote,

I

concur in general with

the inferences he draws from it, and

I

believe that this way of interpreting

monetary history can be, and in my work with Jordi Gali and Mark Gertler

(1998a, 1998b) has already been, applied in fruitful ways that complement the

application emphasized in this paper.

Richard

H.

Clarida is professor

of

economics and international affairs and chairman

of

the

Department of Economics, Columbia University.

342

John

B.

Taylor

The basic idea is straightforward, and much of the paper is devoted to justi-

fying its application. A baseline, or reference, time path of the short-term (fed-

eral funds) interest rate is constructed using a Taylor (1993) rule of the form

r,

=

rf

+

rr*

+

h(q

-

TT*)

+

gy,,

where

ri

is the long-run equilibrium real interest rate,

TT*

is the long-run equi-

librium rate of inflation, and

y,

is the output gap. After the baseline is con-

structed, the actual time path of the short-term interest rate is compared to the

baseline path. Episodes (i.e., sequences of observations) in which the funds

rate is persistently higher than the baseline path are interpreted as episodes of

excessively “tight” monetary policy, while episodes in which the funds rate is

consistently below the baseline are interpreted as episodes in which monetary

policy is too “easy.” Although Taylor provides some qualification in footnote

12,

he is explicit in his interpretation of these episodes of “easy” and “tight”

policy as representing policy mistakes.

Now if, as we have learned from the central bankers present at this confer-

ence, the Taylor rule can be and is used as a benchmark for assessing the cur-

rent stance of actual monetary policies, then certainly it can also be used as

part of a framework to interpret monetary history. But certainly the caveats that