NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

DONALD TRUMP'S WORDS

Nikita Savin

Daniel Treisman

Working Paper 32665

http://www.nber.org/papers/w32665

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

July 2024

The authors have no sources of funding or financial relationships relevant to this project. The

views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the

National Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been

peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies

official NBER publications.

© 2024 by Nikita Savin and Daniel Treisman. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to

exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit,

including © notice, is given to the source.

Donald Trump's words

Nikita Savin and Daniel Treisman

NBER Working Paper No. 32665

July 2024

JEL No. P0

ABSTRACT

Donald Trump’s campaign speeches have impressed some and outraged others. Yet relatively

little is known about how his rhetoric has changed over time and how it compares to that of other

politicians, both in the US and abroad. We analyze a monthly series of Trump’s public addresses

in 2015-24, comparing them to speeches by other U.S. presidential candidates and various world

leaders, past and present. We find that Trump’s use of violent vocabulary has increased over time

—reflecting increasing attention to wars but even more to crime—and now surpasses that of all

other democratic politicians we studied. Simultaneously, Trump’s use of words related to

economic performance has declined, matching a general trend among presidential candidates.

Finally, although containing populist elements, Trump’s rhetoric diverges from the populist

stereotype in notable ways, particularly in his relatively infrequent references to “the people.” He

increasingly exemplifies a negative populism, concentrated on denigrating out-groups.

Nikita Savin

Department of Political Science

UCLA

4289 Bunche Hall

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1472

USA

Daniel Treisman

Department of Political Science

UCLA

4289 Bunche Hall

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1472

and NBER

A data appendix is available at http://www.nber.org/data-appendix/w32665

1

1 Introduction

In reshaping the Republican Party and unsettling American politics, Donald Trump has used one

surprisingly effective weapon: his own words. Without political experience, a record to run on, or a team

of policy professionals, he managed to project an image that won him the nomination and presidency in

2016 and threatens to do the same in 2024. How he did so remains a topic of debate. But there is no doubt

that the content of his public speeches played an important part.

How does Trump’s use of words compare to that of other candidates and incumbents, past and present?

To his rival, President Joe Biden, Trump’s vituperative style seemed unprecedented. “No president has

ever spoken like that before,” Biden asserted during the June 27, 2024, debate. Is he right that Trump is

unique or is the former president just an extreme example of tendencies observable in the discourse of

other politicians, driven perhaps by recent cultural or political trends? How has Trump’s vocabulary

changed over time? These questions are as important for gauging future possibilities as for interpreting

the past.

Scholars have documented various features of Trump’s political speech. Expressed in simple language, rich

in derogatory rhetoric and name-calling, his pronouncements are less analytical and exhibit less cognitive

complexity than those of other recent presidents (Conway III & Zubrod, 2022; Jamieson & Taussig, 2017;

Jordan et al., 2019). As of 2016, they showed stronger markers of populism than those of any other

presidential candidate except Bernie Sanders (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018) and rated high for

grandiosity (Ahmadian et al., 2017). They repeatedly exploited six common rhetorical tricks (Mercieca,

2020).

Building on this previous work, we use computerized text analysis to study a monthly series of Trump's

2

addresses delivered to large general audiences from the start of his 2015 campaign to the present. We

compare these to speeches by all the US main party presidential candidates since 2008 and to those of a

variety of world leaders, past and present, from both democracies and dictatorships.

Three key points emerge. First, the frequency of violent vocabulary in Trump’s addresses has trended

upward since 2015 and is now higher than that of any other democratic politician we examined. The rise

is driven in part by increasing talk of war and military battles but to a greater extent reflects a growing

focus on crime. Second, a main assumption of decades of work on US electoral politics is that incumbents

are rewarded or punished for the quality of economic performance on their watch and their success in

providing public services. Thus, we might expect politicians to speak about these, either to attack their

opponents’ economic stewardship and policies or to champion their own. We show that Trump’s use of

economics-related vocabulary has consistently decreased over time, fitting into a broader trend visible

among both parties’ presidential candidates since at least 2012. Trump’s use of words related to public

service provision has always been low.

Finally, right populists such as Trump are thought to identify with “the people” in opposition to “elites,”

accentuating shared national culture, and promoting a discourse of “us” against “them” (Mudde, 2007).

The more inclusive version of populism emphasizes a positive common identity (“us”), while a more

xenophobic strain focuses on a threatening other (“them”). We show that, in some ways, Trump’s rhetoric

diverges from this pattern. On average, he refers to “the people” more rarely than almost any other recent

candidate, and his use of “we” and its variants is not unusually high. Where Trump takes the lead is in

markers of negative populism—a much higher use of “they” (as in “they treat us like garbage,”

1

or

1

“Republican Leadership Summit, Donald Trump,” April 18, 2015, CSPAN, https://www.c-

span.org/video/?325374-10/republican-leadership-summit-donald-trump.

3

“they’re… poisoning our country”

2

) and—in certain periods—of terms denoting elites (e.g., “the corrupt

globalist establishment”

3

). That said, Trump’s rhetoric has varied significantly over time. During the

course of his first presidential campaign in 2015-16, his vocabulary evolved rapidly towards a relatively

inclusive style: his uses of “we,” and “the people,” surged, while his references to “them” and even his

use of swear words fell. These indicators then reversed course during his presidency. Since his 2020

campaign, references to elites and to “them” and his use of swear words have all rebounded while uses of

“we” and “the people” have remained low.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section discusses previous work on speech analysis of

American politicians, and, in particular, Trump. Section 3 describes our data and methods. Section 4

presents results. Section 5 concludes.

2 Previous literature

A variety of studies by political scientists, psychologists, and linguists have used text analysis to examine

the public speeches of recent politicians. Some have focused on their semantic content. For instance,

certain works analyze the range of topics covered (Calvo-González et al., 2023) or how particular topics

are framed (Card et al., 2022). Others have considered whether the arguments are informed by ideologies

such as liberalism (Maerz & Schneider, 2020), conservatism (Prothro, 1956), nationalism (Bonikowski et

al., 2021; Jenne et al., 2021), or populism (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018) and, if so, how the

2

“Former President Trump Speaks at America First Policy Institute Summit,” July 26, 2022, CSPAN,

https://www.c-span.org/video/?521940-1/president-trump-speaks-america-policy-institute-summit.

3

“Former President Trump Speaks in New Hampshire,” April 27, 2023, CSPAN, https://www.c-

span.org/video/?527693-1/president-trump-speaks-hampshire.

4

speaker’s ideology correlates with the style of speech (McDonnell & Ondelli, 2022).

Another line of research focuses on the vocabulary used. Some use the connotations of words to measure

the emotional valence of speeches (Gennaro & Ash, 2021; Osnabrügge et al., 2021; Whissell, 2021;

Windsor et al., 2018) and to detect incivility (Brooks & Geer, 2007). Others seek to characterize the

personalities of presidential candidates by studying their linguistic styles (Jamieson & Taussig, 2017;

Slatcher et al., 2007). An additional focus has been on what the word usage reveals about the speaker’s

cognitive processes. Studies have measured the degree of integrative complexity and analytic thinking in

the public addresses of US politicians and documented long term declines in both of these (Conway III &

Zubrod, 2022; Jordan et al., 2019).

Finally, certain papers concentrate specifically on the political speech of Donald Trump. Some examine

how his rhetoric appeals to working class voters (Lamont et al., 2017), politicizes immigration

(Eshbaugh-Soha & Barnes, 2021), uses populist tropes (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2018), or exhibits

Richard Hofstadter’s “paranoid style” in American discourse (Hart, 2022). In cognitive style, he is lower

in analytic thinking and integrative complexity than almost any previous American president since at least

the 1960s (Conway III & Zubrod, 2022; Jordan et al., 2019). His campaign speeches in 2016 were more

negative than Hillary Clinton’s (Liu & Lei, 2018) and exhibited high levels of grandiosity (Ahmadian et

al., 2017). To our knowledge, no study has yet provided a comprehensive measure of the frequency of

violent rhetoric in Trump’s speeches over the full period of his high profile political activity, compared

the violence of his addresses to the levels of other politicians, and mapped the trends in his rhetoric over

5

time.

4

While many works—like our own—aim to describe and classify the content of political speeches, others

explore the effects of political rhetoric. These studies suggest a range of consequences. At the micro level,

uncivil or violent language can stimulate feelings of hostility and aggressive thoughts (Anderson et al.,

2003; Gervais, 2017, 2019) or weaken taboos against hateful speech (Newman et al., 2021). Some

evidence suggests that such language can even provoke violent actions (Gubler et al., 2015). Violent

rhetoric does not have to be direct and literal to have an effect. Even relatively mild violent metaphors—

e.g., references to “fighting” for justice and opportunity—have been shown to boost support for political

violence among experimental subjects with aggressive personalities (Kalmoe, 2014). Such subjects were

more likely to justify “throwing bricks through windows” or “using bullets to solve political problems”

after priming with such metaphors. The same metaphors may also motivate aggressive individuals to vote

while discouraging less aggressive ones from doing so (Kalmoe, 2019).

Besides tracing micro consequences of leaders’ speech, research also suggests various macro effects. In

democracies, politicians’ rhetoric may affect their approval ratings (Druckman & Holmes, 2004; Frimer

& Skitka, 2018) and electoral success (Selb & Munzert, 2018; Vavreck, 2009). Greater optimism in

campaign speeches has been found to predict—although not necessarily cause—victory in senatorial and

presidential races (Zullow et al., 1988). Some research has linked politicians’ violent language to violent

actions by their supporters. For instance, Trump’s Islamophobic Tweets have been found to increase

attacks on minorities (Müller & Schwarz, 2023). Counties where Trump held campaign rallies in 2016

saw a rise in hate crimes in the following months (Feinberg et al., 2022). In authoritarian regimes, the

4

Besides the analysis of public speeches by politicians, a growing parallel literature analyzes politicians’ comments

on social media, often using similar text analysis tools (for a few examples, see Barberá et al., 2019; Van Vliet et al.,

2020; Wilkerson & Casas, 2017).

6

inflammatory rhetoric of politicians, transmitted by the media, has been linked to ethnic violence from

Nazi Germany to Rwanda (Adena et al., 2015; Yanagizawa-Drott, 2014). Politicians’ speech may even

contain clues about the stability of their regimes (Windsor et al., 2018). Of course, elite rhetoric is only

one of many factors explaining political behavior, and tracing the causal impact of particular

pronouncements is extremely hard. Still, the accumulation of such evidence to date suggests the value of

carefully studying what politicians say.

3 Data and methods

We analyzed the transcripts of 99 speeches delivered by Donald Trump between April 2015, at the start of

his first presidential campaign, and June 2024.

5

The goal was to include one speech from each month. To

increase comparability, we used the last one in each month that fit certain requirements (except in

November of presidential election years, when we used the last appropriate speech before the election).

Throughout his time in office, Trump continued to stage “Make America Great Again” rallies around the

country that were similar to his campaign events. To focus on political rallies and mass meetings aimed at

the general public, we excluded press conferences, meetings with members of Congress, remarks made

from the White House, video statements, commencement addresses, speeches in churches, speeches made

outside the US, speeches to troops, law enforcement agents, particular ethnic and religious communities,

or political action committees (e.g., AIPAC), and speeches billed as focused on specific policy areas such

as national security. However, we did include speeches to political parties, political conferences, and

labor unions.

5

Although he officially announced his candidacy on June 16, 2015, he was already hinting strongly at this decision,

for instance, in his speech to the Republican Leadership Summit on April 18.

7

Since we could find no comprehensive list of all Trump’s appearances, we used a variety of sources to

identify the last appropriate speech in each month and obtain a transcript. These sources included

CSPAN’s video library, the Rev.com transcription service, the White House website and online archives,

and the American Presidency Project at UC Santa Barbara.

6

We found at least one appropriate speech in

all but 12 of the 111 months between April 2015 and June 2024. Besides the 99 Trump speeches, we also

analyzed 127 speeches delivered by the other major party candidates in the 20 pre-election months in each

US presidential election cycle from 2008 to 2024, selected in the same way. In almost all cases, a

transcript was available on one of the four websites; occasionally, we used a transcript from some other

source such as a newspaper.

We prepared the transcripts by removing all parts not spoken by the individual in question (e.g.,

“[Applause.]”, “Audience: Boo!”). If an introductory address was followed by questions, we included

only the introductory address. The quality of transcripts was generally high, but some of the CSPAN texts

were compiled from TV closed captioning and therefore contained more mistakes and missed words.

Where possible, we corrected these with reference to the corresponding videos. To check that the source

of transcript does not distort the results, we regressed the level of Trump’s violent rhetoric on dummy

variables for the source, along with year dummies. None of the sources differed significantly from the

others in the frequency of violent words recorded for Trump. (The nonsignificant differences may be

caused by the selection of speeches by different media. Figure A1 in the appendix shows the original

violence score and a version adjusted by the averaged deviation of each other source from CSPAN.)

The main dictionary we used was compiled by Guriev and Treisman (2019) (GT) to study differences in

6

See https://www.c-span.org/, https://www.rev.com/about-rev, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/,

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/, and https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/.

8

rhetoric among the leaders of different types of political regimes. GT focused on words related to three

subjects—violence, economic performance, and public service provision. They formed initial lists for

each concept by examining the speeches of a number of historical leaders in both democracies and

autocracies; they then removed any words where further inspection of the speeches revealed two or more

uses in a second meaning unrelated to the target concept. The GT dictionary includes 142 word stems

related to violence (e.g., death*, massacre*, war*, blood*, prison*), 112 word stems related to economic

performance, and 28 word stems related to public service provision. To validate the dictionary, they used

it to analyze sample texts known to be high in words related to one of the three concepts—prosecutors’

closing arguments in war crimes and terrorist trials for violence, IMF reports for economic performance,

and the budget speeches of finance ministers for public service provision. The dictionary was able to

classify these sources into the three bundles with high accuracy (see Figure A5).

To check the robustness of analysis using this dictionary, we also tried replacing it with several others.

For violence, we used two dictionaries compiled by Boyd et al. (2022) and included in the latest version

of their Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC-22) package that aimed to capture words related to

“conflict” and to “death.” The patterns in Trump speeches that these identified were less pronounced but

similar to those captured by the GT violence list (see Figure A2). Scores for Trump speeches using the

GT dictionary correlated highly with those generated by the “conflict” dictionary (r = .71) and by the

“death” list (r = .62). Finally, we obtain very similar results using a dictionary derived by asking

ChatGPT to list the most common words related to violence (r = .82; see Figure A3).

Violence occurs in various contexts. For instance, politicians might be expected to speak about both wars

and domestic crime. While some words apply to both wars and crime roughly equally (e.g., death, blood),

others are more closely linked to either war (e.g., invasion) or crime (e.g., prosecution). To separate these

9

out, we constructed crime and war sub-dictionaries by selecting words from the GT dictionary that related

primarily to one or the other. This yielded a crime sub-dictionary of 13 word stems (such as murder*,

prison*, arrest*, prosecut*) and a war sub-dictionary of 40 words (such as army, invasion, soldier*,

conquer*). Again, to check the results using these dictionaries, we constructed backup dictionaries by

asking ChatGPT for the most common 100 words about “crime” and about “war.”

To check for markers of populist discourse, we used several additional dictionaries. First, populists claim

to represent “the people” against “the elite,” embracing a discourse of “us” against “them.” We created a

simple dictionary to pick up references to the people, containing just four terms: “the people of…,” “the

American people,” “Americans,” and “patriots.” From reviewing a few speeches, it became clear that the

simple phrase “the people” often appeared with meanings quite different from the ones we sought to

target (e.g., “the people from China,” “the people negotiating”). However, we found that “the people of”

was almost always used in phrases such as “the people of Alabama,” “the people of this great country,”

and “the people of America.”

7

To identify references to “us” and “them” along with their variants, we

used dictionaries incorporated in LIWC-22 (Boyd et al., 2022). For terms denoting the elite, we again

created a new dictionary. We began by reading four of Trump’s speeches—three from 2016, one from

2024—and two speeches by each of the other main party candidates in all presidential elections between

2008 and 2024—that were not included in our main corpus (i.e., ones that were not the last in a given

month) and selecting words and phrases used in pejorative statements about political elites. This produced

a list of 45 word stems and phrases (e.g., corrupt*, crooked, deep state, and drain the swamp). Finally, we

also used the LIWC-22 dictionary for swear words to check for the kind of coarsening of language that

7

In practice, including all references to “the people” produces an almost identical trend in Trump speeches, just a

little higher than the version including only “the people of…”.

10

commentators have attributed to Trump.

8

To execute the text analysis, we used the program Linguistic

Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC-22) (Boyd et al., 2022), which has been employed in hundreds of

previous studies.

4 Results

4.1 Violent vocabulary

Figure 1 shows the percentage of violence-related words in the speeches of recent US presidential

candidates. In each case, the dotted line connects the individual monthly values, and the solid line shows a

centered, 9-month moving average. The frequency of violence-related words in Trump speeches has,

indeed, increased substantially, from around 0.6 percent in 2015 to a peak of 1.6 percent in July 2022 and

again in April 2024.

9

The content varies from month to month, but the trend of rising waves is clear.

Biden’s use of violent vocabulary was lower than Trump’s in 2019-20 and has fallen short by an even

larger margin so far in 2023-24. By contrast, Hillary Clinton’s speeches in 2015-16 used violent words

slightly more frequently than Trump’s at that time. One Clinton rally in Cincinnati in October 2016 was

an outlier: at this event, former Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, who had been seriously injured in an

assassination attempt, appeared with Clinton, who used the occasion to denounce the “epidemic of gun

violence.” But even before then, Clinton’s campaign speeches—which often advocated gun control and6

deplored racist attacks on African Americans—contained more violent vocabulary than Trump’s.

Running to be the first female president, Clinton may have felt the need to show toughness. There was

8

All non-LIWC dictionaries are provided in Table A2.

9

For reference, in Trump’s speeches since 2015, the frequency of the word “the” was 3.72%.

11

little violent rhetoric in the speeches of Obama and Romney. John McCain’s speeches started at a high

level—the former war hero had much to say about the ongoing war in Iraq—but the average intensity fell

during his campaign.

How does the frequency of violent words in Trump’s political speeches compare to that of other leaders,

past and present? Table 1 shows some more comparisons, drawing on both our own speech collections

and those of GT. To anchor expectations, we show the frequency of such words in the closing arguments

of the prosecutors at several trials for war crimes and terrorist attacks that were used by GT to validate

their violence dictionary—in each, at least 2.5 percent of words had violent connotations. Trump’s

12

average use of violent vocabulary in the 2023-4 campaign, at 1.06 percent, exceeds that of any other

politician in a democracy that we studied and falls just a little below the level in a selection of Fidel

Castro’s May Day speeches. A selection of speeches by Senator Bernie Sanders, who sought but did not

secure the Democratic Party nomination in 2020, scored almost as high in 2019-20, but that was largely

because of his denunciations of Trump’s policies. Senator John McCain’s average in 2007-8 was .90,

reflecting the attention he paid to the ongoing Iraq war. Most other democratic politicians scored much

lower.

Table 1: Average percentage of words in assorted speeches and documents

1. Violence

2. Specific to

crime

3. Specific to

war

Prosecutor’s closing argument in Boston bombing trial

4.75

0.99

0.03

Prosecutor’s closing argument in Nuremberg trial

3.19

0.71

1.19

Prosecutor’s closing argument in Radovan Karadzic trial

2.50

0.83

0.51

Stalin, two pre-election speeches, 1937, 1946

2.39

0.03

1.76

Hitler, four radio speeches, 1933-8

1.82

0.06

0.73

Vladimir Putin, 2023 annual address

1.61

0.08

0.63

Kim Jong-Un, New Year's speeches, 2013-16

1.30

0.01

0.71

Fidel Castro, various May Day speeches, 1966-2006

1.15

0.16

0.32

Trump rallies, 2023-24

1.06

0.21

0.29

Sanders campaign, 2019-20

0.97

0.29

0.15

McCain campaign, 2007-8

0.90

0.08

0.34

Trump rallies, 2019-20

0.77

0.14

0.18

Nicolas Sarkozy, New Year's Greetings, 2009-13

0.75

0.05

0.11

Clinton campaign, 2015-16

0.68

0.08

0.08

Trump rallies, 2015-16

0.55

0.07

0.13

Biden campaign, 2019-20

0.53

0.03

0.15

Obama campaign, 2007-8

0.51

0.02

0.21

Biden campaign, 2023-24

0.43

0.02

0.11

Obama campaign, 2011-12

0.39

0.01

0.13

Vladimir Putin, 2012 annual address

0.38

0.05

0.16

FDR “Fireside Chats,” 1933-8

0.31

0.00

0.10

Romney campaign, 2011-12

0.29

0.01

0.11

David Cameron, various speeches, 2014-15

0.23

0.05

0.07

Sources: See Table A1 for recent US speeches; lines 1-5, 7-8, 13, 21, 23 from Guriev and Treisman (2019). Putin annual

addresses from www.kremlin.ru.

13

We caution that our method captures only one type of violent rhetoric—that which employs distinctively

violent words. Thus, it complements other approaches that focus on incivility, incitement, dehumanizing

language, or hate speech, each of which can be expressed using combinations of neutral words. At the

same time, the use of violent words does not necessarily involve calls for violence; these are extremely

rare in campaign speeches, and when they occur they tend to be ambiguously or euphemistically phrased.

Trump’s January 6

th

, 2021, speech does not score particularly high for violent words (0.64 percent),

which did not stop some listeners from hearing in it a demand to storm the Capitol. Violent words can

also be used to criticize violent behavior, as when Hillary Clinton and others called in their speeches for

stricter gun controls. In light of this, the trend we document in Trump’s word usage suggests a growing

focus on violent subjects, described in explicit terms, that is not matched by the other major party

candidates.

Within the lexicon of violence used by presidential candidates, some words are associated more with wars

and external military conflict (e.g., army, invasion), others with domestic crime (e.g., prosecution,

prison), while still others are more general and context-neutral (e.g., death, fight). The candidates differ in

the relative balance among these. Since 2019-20, Trump has used specifically crime-related violent words

far more frequently than any other recent major party candidate, and he exceeded most others in the use

of specifically war-related ones (Table 1, columns 2 and 3). His use of both has been rising (Figures 2 and

3). But in 2007-8, both McCain and Obama had even higher levels of violent war-related references in

their speeches, reflecting the attention then paid to the ongoing war in Iraq.

10

10

Looking beyond the major party candidates, Bernie Sanders had an even higher average level of references to

crime (0.29) in 2019-20 than Trump has reached so far in 2023-4. But while Trump’s talk of crime involved

denouncing his own “communist show trial” and warning of murders and muggings in New York, Sanders’

references were mostly about the need for criminal justice reform.

14

15

4.2 Economic performance and public service provision

Incumbents are more popular in both democracies and autocracies when their economies boom and public

services are generously provided (e.g., Gandhi, 2008; Guriev & Treisman, 2020; Przeworski et al., 2000).

Thus, we might expect politicians to seek to convince the public that they are effective economic

managers and public servants. Figure 4 shows how frequently the top US presidential candidates have

used words related to economic performance. The striking trend that emerges is the steady decline in talk

of economic conditions since 2012 among candidates of both parties. Trump fits squarely into this trend,

with a sharp fall in economic talk during the 2020 campaign. The period from 2008 to 2012 saw an

apparent increase in the salience of economic performance, not surprisingly given the unfolding of the

global financial crisis.

16

The trend in references to public service provision is less clear (Figure 5). But with the exception of a few

months of Biden speeches in 2023, the Democrats have consistently mentioned this more than the

Republicans. Trump was particularly sparing in talk of public service provision with little variation over

time.

4.3 Markers of populist discourse

If candidates are speaking less about the traditional foci of domestic governance—economic performance

and public services—they must be appealing to voters in other ways. We have already noted Trump’s

increasing attention to violence, and in particular crime. He is viewed by many as the prototype of an

“authoritarian populist” (Mounk, 2021), so it made sense to check for the frequency in his speeches of

familiar markers of populist discourse.

17

In fact, Trump’s speeches contain relatively few allusions to “the people” (Table 2). The champion in this

was actually Romney in 2011-12, followed by Obama in 2007-8. Trump uses “we” and its variants more

frequently than Biden, Clinton, Romney, or McCain, but not than Obama (of the slogan “Yes we can!”).

Trump also uses a great deal of anti-elite vocabulary at times. However, McCain and Obama in 2007-8

(although not 2011-12, when Obama was an incumbent) had comparable levels.

Table 2. Elements of populist discourse

“The people”

“We”

“They”

“Elites”

Trump rallies 2023-24

.09

3.22

2.64

.46

Trump rallies 2019-20

.19

3.76

2.50

.25

Trump rallies 2015-16

.13

3.27

2.47

.37

Biden campaign 2023-24

.20

3.14

1.08

.13

Biden campaign 2019-20

.28

3.04

1.34

.15

Clinton campaign 2015-16

.23

3.07

1.33

.14

Obama 2011-12

.26

4.06

1.19

.18

Obama 2007-08

.47

3.69

1.36

.45

Romney 2011-12

.50

2.98

1.29

.07

McCain 2007-8

.40

2.99

1.09

.32

Sources: See Table A1 for sources of speeches.

Where Trump is most distinctive is in his frequent use of the third person plural. Of course, “they” can be

employed in multiple ways. Still, social psychologists have attributed significance to elevated usage of

this part of speech. The frequency of “they” and its variants has been found to be higher than typical

among supporters of extremist groups (Pennebaker et al., 2008; Torregrosa et al., 2019) and among

opponents of immigration (Grover et al., 2019). It is the pronoun of choice when invoking a dangerous

“other.” “If worried about communists, right-wing radio hosts, or bureaucrats, words such as they and

them will be more frequent than average” (Pennebaker, 2013, p. 292).

11

11

For what it’s worth, high usage of third person pronouns is also found among guilty criminal defendants and

people who are angry (Pennebaker, 2013, pp. 153–154, 107).

18

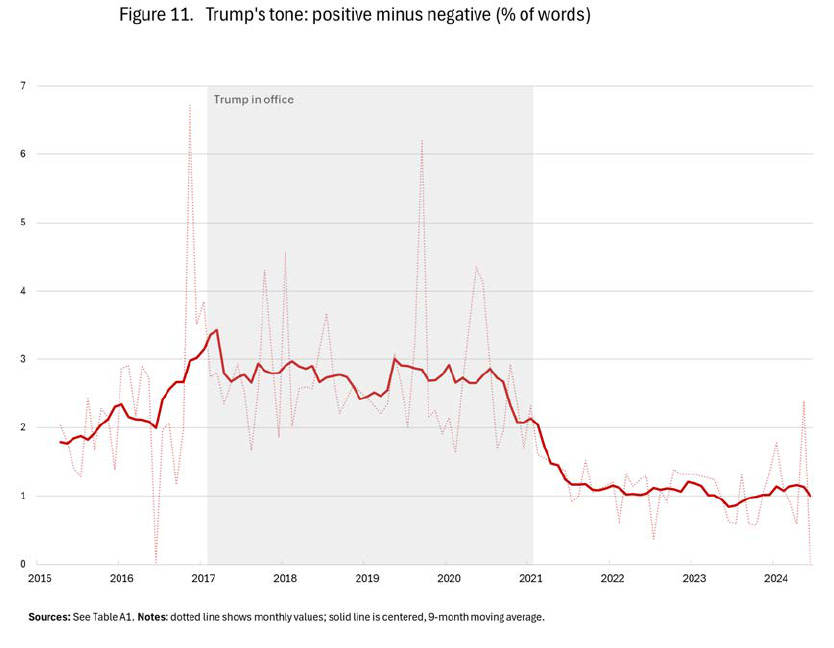

As interesting as cross-sectional differences between Trump and other candidates is the marked variation

over time in his vocabulary. His first presidential campaign in 2015-16 saw rapid stylistic change. During

those months, his language became more inclusive, with a surge in the uses of “we,” and “the people,”

alongside a decline in references to “them” and even in his use of swear words (Figures 6-10) . His tone,

as measured by LIWC-22, became more positive (Figure 11). With Trump in the White House, these

indicators reversed course. Since then, his uses of “we” and of “the people” have decreased, while his

uses of “they” and of swear words have recovered. All in all, this looks like a concerted effort to project

an inclusive populist image during his first campaign, followed by a reversion to his previous persona.

His tone remained relatively positive and his attacks on elites less frequent during his presidency, but both

deteriorated sharply after he lost the White House in 2020. He began the 2024 campaign with an angry,

exclusionary version of populism.

19

20

6

21

5 Conclusion

This paper has explored the evolution of Donald Trump’s public speeches from the onset of his political

career in 2015 to his most recent rallies in 2024. Using computerized text analysis, we identified key

trends in Trump’s word usage and compared these to the speech patterns of other major political figures.

We derived three main results.

First, the frequency of violent words in Trump’s speeches has trended upward since 2015, eventually

surpassing that of all other democratic politicians we examined. This reflects both escalating references to

war and military battles and—even more strongly—an intensified focus on crime. The growing violence

of Trump’s language suggests a strategy aimed at spreading anxiety in order to boost demand for a strong

22

leader who can combat the threats he invokes. These results systematically confirm the observations of

political journalists (Homans, 2024) and speak to recent debates about the state of American democracy.

Levitsky and Ziblatt (2023), for instance, argue that the rhetoric of Republican politicians has become

more divisive and confrontational, in a way that may erode democratic norms. We show that the most

influential Republican these days is, indeed, using increasingly aggressive language. Various studies have

noted upticks in uncivil behavior and political violence during the Trump presidency, including threats to

members of Congress, crimes against minorities, and killings (e.g., Nacos et al., 2024). Some have linked

the incidence of hate crimes to Trump’s campaign rallies and Tweets (Feinberg et al., 2022; Müller &

Schwarz, 2023). Given the troubling evolution of his vocabulary, more research along these lines is

clearly warranted.

Second, we show that Trump’s use of words related to economic performance has decreased over time,

aligning with a broader trend in the speech of the candidates of both major parties since at least 2012.

This may reflect an underlying change in the effectiveness of economic appeals. As Vavreck (2009)

showed, all insurgent candidates since 1952 who ran on the economy lost their elections. Trump, running

as an insurgent in 2016, made far fewer economic references than his predecessor, the unsuccessful

Republican candidate Mitt Romney—and won. Identity issues now often take the place once occupied by

economic considerations (Sides et al., 2018). To the extent voters still decide based on economic

performance, their beliefs about that performance are highly distorted by partisan bias. In this

environment, Trump—and other politicians—may correctly see partisan, identity-based appeals as a

better bet.

Third, analyzing Donald Trump’s rhetoric offers lessons about the flexible nature of populism. Populism

is often described as a “thin-centered ideology” because it can be combined with more substantive

philosophies of left or right (e.g., Mudde, 2007). Others see it more as a style than a set of ideas. We

found that Trump’s approach both conforms to and diverges from the expected populist pattern. Most

23

populist politicians extoll and claim to represent “the people,” imagined as a homogeneous unity. Trump

invokes “the people” relatively rarely. He excels in what we called “negative populism,” focused on

identifying outgroups and framing them as enemies or threats. In such antagonistic variants, frequent

references to “they” may constitute a “we” as a byproduct (Laclau, 2005). Trump uses populist elements

selectively, adjusting their political coloration as the situation dictates.

One question often debated concerns the degree to which Trump is unique or merely the latest instance of

a pre-existing trend. We showed that some aspects of his language usage fit into broader patterns. His

declining attention to economic performance appears to reflect a system-wide phenomenon, visible

among candidates of both parties. Previous work showed that the simplicity and self-confidence of

Trump’s speech aligns with a centuries-long trend in US politics (Jordan et al., 2019). However, in some

ways, Trump seems more distinctive. We do not observe any general trend towards more violent

vocabulary among other presidential candidates. And trends in the markers of populism are certainly not

universal.

Our study has certain clear limitations. First, we make no causal claims about determinants or

consequences of Trump’s speeches. Although we cite some relevant research, we provide no evidence

about why Trump’s speeches have varied over time or what difference that makes. While there is a wide

consensus among political scientists that what politicians say in public matters (e.g., Vavreck, 2009;

Zaller, 1992), there are many avenues through which words can influence citizens. The possible effects of

Trump’s increasingly violent vocabulary obviously merit further study. Second, dictionary-based text

analysis simply measures the frequency of words without delving deeper into meanings and contexts.

While it can reveal important patterns, it leaves many nuances unexplored. As van Dijk (1997) noted,

context matters greatly in political speeches. Future research could usefully incorporate contextual

analysis to investigate the patterns in Trump’s speeches that we identify. Third, we compare Trump’s

speech to a somewhat limited sample of other US presidential candidates and world leaders. Extending

24

this sample both temporally and to broader categories of public figures might suggest additional

comparative insights.

25

References

Adena, M., Enikolopov, R., Petrova, M., Santarosa, V., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2015). Radio and the Rise of

the Nazis in Prewar Germany. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(4), 1885–1939.

Ahmadian, S., Azarshahi, S., & Paulhus, D. L. (2017). Explaining Donald Trump via communication

style: Grandiosity, informality, and dynamism. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 49–

53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.018

Anderson, C. A., Carnagey, N. L., & Eubanks, J. (2003). Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs

with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 84(5), 960.

Barberá, P., Casas, A., Nagler, J., Egan, P. J., Bonneau, R., Jost, J. T., & Tucker, J. A. (2019). Who leads?

Who follows? Measuring issue attention and agenda setting by legislators and the mass public

using social media data. American Political Science Review, 113(4), 883–901.

Bonikowski, B., Feinstein, Y., & Bock, S. (2021). The partisan sorting of “America”: How nationalist

cleavages shaped the 2016 US presidential election. American Journal of Sociology, 127(2), 492–

561.

Boyd, R. L., Ashokkumar, A., Seraj, S., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2022). The development and psychometric

properties of LIWC-22. Austin, TX: University of Texas at Austin, 1–47.

Brooks, D. J., & Geer, J. G. (2007). Beyond negativity: The effects of incivility on the electorate.

American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 1–16.

Calvo-González, O., Eizmendi, A., & Reyes, G. (2023). The Shifting Attention of Political Leaders:

Evidence from Two Centuries of Presidential Speeches.

Card, D., Chang, S., Becker, C., Mendelsohn, J., Voigt, R., Boustan, L., Abramitzky, R., & Jurafsky, D.

(2022). Computational analysis of 140 years of US political speeches reveals more positive but

increasingly polarized framing of immigration. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences, 119(31), e2120510119.

26

Conway III, L. G., & Zubrod, A. (2022). Are US Presidents becoming less rhetorically complex?

Evaluating the integrative complexity of Joe Biden and Donald Trump in historical context.

Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 41(5), 613–625.

Druckman, J. N., & Holmes, J. W. (2004). Does Presidential Rhetoric Matter? Priming and Presidential

Approval. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 34(4), 755–778. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27552635

Eshbaugh-Soha, M., & Barnes, K. (2021). The immigration rhetoric of Donald Trump. Presidential

Studies Quarterly, 51(4), 781–801.

Feinberg, A., Branton, R., & Martinez-Ebers, V. (2022). The Trump effect: How 2016 campaign rallies

explain spikes in hate. PS: Political Science & Politics, 55(2), 257–265.

Frimer, J. A., & Skitka, L. J. (2018). The Montagu Principle: Incivility decreases politicians’ public

approval, even with their political base. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(5),

845.

Gandhi, J. (2008). Political Institutions under Dictatorship. Cambridge University Press.

Gennaro, G., & Ash, E. (2021). Emotion and Reason in Political Language. The Economic Journal,

132(643), 1037–1059. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueab104

Gervais, B. T. (2017). More than mimicry? The role of anger in uncivil reactions to elite political

incivility. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 29(3), 384–405.

Gervais, B. T. (2019). Rousing the partisan combatant: Elite incivility, anger, and antideliberative

attitudes. Political Psychology, 40(3), 637–655.

Grover, T., Bayraktaroglu, E., Mark, G., & Rho, E. H. R. (2019). Moral and affective differences in us

immigration policy debate on twitter. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 28(3),

317–355.

Gubler, J. R., Kalmoe, N. P., & Wood, D. A. (2015). Them’s fightin’words: The effects of violent

rhetoric on ethical decision making in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 130, 705–716.

27

Guriev, S., & Treisman, D. (2019). Informational autocrats. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4),

100–127.

Guriev, S., & Treisman, D. (2020). The popularity of authoritarian leaders: A cross-national investigation.

World Politics, 72(4), 601–638.

Hart, R. P. (2022). Why Trump lost and how? A rhetorical explanation. American Behavioral Scientist,

66(1), 7–27.

Hawkins, K. A., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Measuring populist discourse in the United States and

beyond. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 241–242.

Homans, C. (2024, April 27). Donald Trump Has Never Sounded Like This. New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/27/magazine/trump-rallies-rhetoric.html

Jamieson, K. H., & Taussig, D. (2017). Disruption, demonization, deliverance, and norm destruction: The

rhetorical signature of Donald J. Trump. Political Science Quarterly, 132(4), 619–650.

Jenne, E. K., Hawkins, K. A., & Silva, B. C. (2021). Mapping populism and nationalism in leader rhetoric

across North America and Europe. Studies in Comparative International Development, 56(2),

170–196.

Jordan, K. N., Sterling, J., Pennebaker, J. W., & Boyd, R. L. (2019). Examining long-term trends in

politics and culture through language of political leaders and cultural institutions. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences, 116(9), 3476–3481.

Kalmoe, N. P. (2014). Fueling the fire: Violent metaphors, trait aggression, and support for political

violence. Political Communication, 31(4), 545–563.

Kalmoe, N. P. (2019). Mobilizing voters with aggressive metaphors. Political Science Research and

Methods, 7(3), 411–429.

Laclau, E. (2005). On Populist Reason. Verso.

Lamont, M., Park, B. Y., & Ayala-Hurtado, E. (2017). Trump’s electoral speeches and his appeal to the

28

American white working class. The British Journal of Sociology, 68, S153–S180.

Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2023). Tyranny of the Minority: Why American Democracy Reached the

Breaking Point. Crown.

Liu, D., & Lei, L. (2018). The appeal to political sentiment: An analysis of Donald Trump’s and Hillary

Clinton’s speech themes and discourse strategies in the 2016 US presidential election. Discourse,

Context & Media, 25, 143–152.

Maerz, S. F., & Schneider, C. Q. (2020). Comparing public communication in democracies and

autocracies: Automated text analyses of speeches by heads of government. Quality & Quantity,

54(2), 517–545.

McDonnell, D., & Ondelli, S. (2022). The Language of Right-Wing Populist Leaders: Not So Simple.

Perspectives on Politics, 20(3), 828–841. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720002418

Mercieca, J. (2020). A field guide to Trump’s dangerous rhetoric. The Conversation, 19.

Mounk, Y. (2021, January 14). After Trump, Is American Democracy Doomed by Populism? Council on

Foreign Relations.

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Müller, K., & Schwarz, C. (2023a). From hashtag to hate crime: Twitter and antiminority sentiment.

American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 15(3), 270–312.

Müller, K., & Schwarz, C. (2023b). From hashtag to hate crime: Twitter and antiminority sentiment.

American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 15(3), 270–312.

Nacos, B., Bloch-Elkon, Y., & Shapiro, R. (2024). Hate Speech and Political Violence: Far-Right

Rhetoric from the Tea Party to the Insurrection. Columbia University Press.

Newman, B., Merolla, J. L., Shah, S., Lemi, D. C., Collingwood, L., & Ramakrishnan, S. K. (2021). The

Trump effect: An experimental investigation of the emboldening effect of racially inflammatory

elite communication. British Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 1138–1159.

29

Osnabrügge, M., Hobolt, S. B., & Rodon, T. (2021). Playing to the Gallery: Emotive Rhetoric in

Parliaments. American Political Science Review, 115(3), 885–899.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000356

Pennebaker, J. W. (2013). The Secret Life of Pronouns: What Our Words Say About Us. Bloomsbury

Publishing USA.

Pennebaker, J. W., Chung, C. K., Krippendorf, K., & Bock, M. (2008). Computerized text analysis of Al-

Qaeda transcripts. A Content Analysis Reader, 453465.

Prothro, J. W. (1956). Verbal shifts in the American presidency: A content analysis. American Political

Science Review, 50(3), 726–739.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., & Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and Development:

Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990. Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804946

Selb, P., & Munzert, S. (2018). Examining a Most Likely Case for Strong Campaign Effects: Hitler’s

Speeches and the Rise of the Nazi Party, 1927–1933. American Political Science Review, 112(4),

1050–1066. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000424

Sides, J., Tesler, M., & Vavreck, L. (2018). Identity crisis: The 2016 presidential campaign and the battle

for the meaning of America. Princeton University Press.

Slatcher, R. B., Chung, C. K., Pennebaker, J. W., & Stone, L. D. (2007). Winning words: Individual

differences in linguistic style among U.S. presidential and vice presidential candidates. Journal of

Research in Personality, 41(1), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.01.006

Torregrosa, J., Thorburn, J., Lara-Cabrera, R., Camacho, D., & Trujillo, H. (2019). Linguistic analysis of

pro-ISIS users on Twitter. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 12 (3):

171–185.

Van Dijk, T.A. (Ed.). (1997). Discourse studies: A multidisciplinary introduction. Sage.

30

Van Vliet, L., Törnberg, P., & Uitermark, J. (2020). The Twitter parliamentarian database: Analyzing

Twitter politics across 26 countries. PLoS One, 15(9), e0237073.

Vavreck, L. (2009). The message matters: The economy and presidential campaigns. Princeton University

Press.

Whissell, C. (2021). Pumping Up the Base: Deployment of Strong Emotion and Simple Language in

Presidential Nomination Acceptance Speeches. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 729751.

Wilkerson, J., & Casas, A. (2017). Large-scale computerized text analysis in political science:

Opportunities and challenges. Annual Review of Political Science, 20, 529–544.

Windsor, L., Dowell, N., Windsor, A., & Kaltner, J. (2018). Leader language and political survival

strategies. International Interactions, 44(2), 321–336.

Yanagizawa-Drott, D. (2014). Propaganda and conflict: Evidence from the Rwandan genocide. The

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), 1947–1994.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge University Press.

Zullow, H. M., Oettingen, G., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (1988). Pessimistic explanatory style in

the historical record: CAVing LBJ, presidential candidates, and East versus West Berlin.

American Psychologist, 43(9), 673.