WP/14/118

Deposit Insurance Database

Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, Edward Kane, and Luc Laeven

© 2014 International Monetary Fund

WP/14/118

IMF Working Paper

Research Department

Deposit Insurance Database

Prepared by Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, Edward Kane, and Luc Laeven

1

Authorized for distribution by Stijn Claessens

July 2014

Abstract

This paper provides a comprehensive, global database of deposit insurance arrangements

as of 2013. We extend our earlier dataset by including recent adopters of deposit insurance

and information on the use of government guarantees on banks’ assets and liabilities,

including during the recent global financial crisis. We also create a Safety Net Index

capturing the generosity of the deposit insurance scheme and government guarantees on

banks’ balance sheets. The data show that deposit insurance has become more widespread

and more extensive in coverage since the global financial crisis, which also triggered a

temporary increase in the government protection of non-deposit liabilities and bank assets.

In most cases, these guarantees have since been formally removed but coverage of deposit

insurance remains above pre-crisis levels, raising concerns about implicit coverage and

moral hazard going forward.

JEL Classification Numbers: G20

Keywords: Deposit insurance; Financial institutions; Financial crises

1

We would like to thank Belen Bazano and Lindsay Mollineaux for excellent research assistance, and IMF

colleagues for their useful comments and help in checking the accuracy of the database. The views expressed here

are our own and not those of the IMF or IMF Board.

This Working Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF.

The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

represent those of the IMF or IMF policy. Working Papers describe research in progress by the

author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate.

2

CONTENTS PAGE

I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................3

II. The Database .........................................................................................................................4

A. Variable Definitions ..................................................................................................4

III. Main Features of Deposit Insurance Schemes Around the World .....................................11

IV. Depositor Protection During the Global Financial Crisis ..................................................14

V. Concluding Remarks ...........................................................................................................18

References ................................................................................................................................20

Figures

Figure 1. Explicit Deposit Insurance by Income Group, 2013 ................................................23

Figure 2. Explicit Deposit Insurance by Region, 2013 ............................................................23

Figure 3. Type of DI Scheme, 2013 .........................................................................................24

Figure 4. Objective of the DI Scheme, 2013 ...........................................................................24

Figure 5. Organization of the DI Scheme, 2013 ......................................................................25

Figure 6. Administration of the DI Scheme, 2013 ...................................................................25

Figure 7. Funding of the DI Scheme, 2013 ..............................................................................26

Figure 8. Coverage Increased During Crisis and Remains Above Pre-Crisis Levels ..............26

Figure 9. Decline of Coinsurance, 2003−2013 ........................................................................27

Figure 10. Risk Adjustment of DI Premiums, 2013 ................................................................27

Figure 11. Government Support of DI Schemes, 2013 ............................................................28

Figure 12. Increase in Depositor Protection, 2007−2013 ........................................................28

Figure 13. Potential Deposit Liabilities and Ability to Pay by the DIS Fund, end-2010 ........29

Figure 14. Total Deposits and Ability to Pay by the Government, end-2010 .........................29

Figure 15. Size of DIS Fund Relative to Covered Deposits and Government Indebtedness...30

Figure 16. Safety Net Index, 2013 ...........................................................................................31

Tables

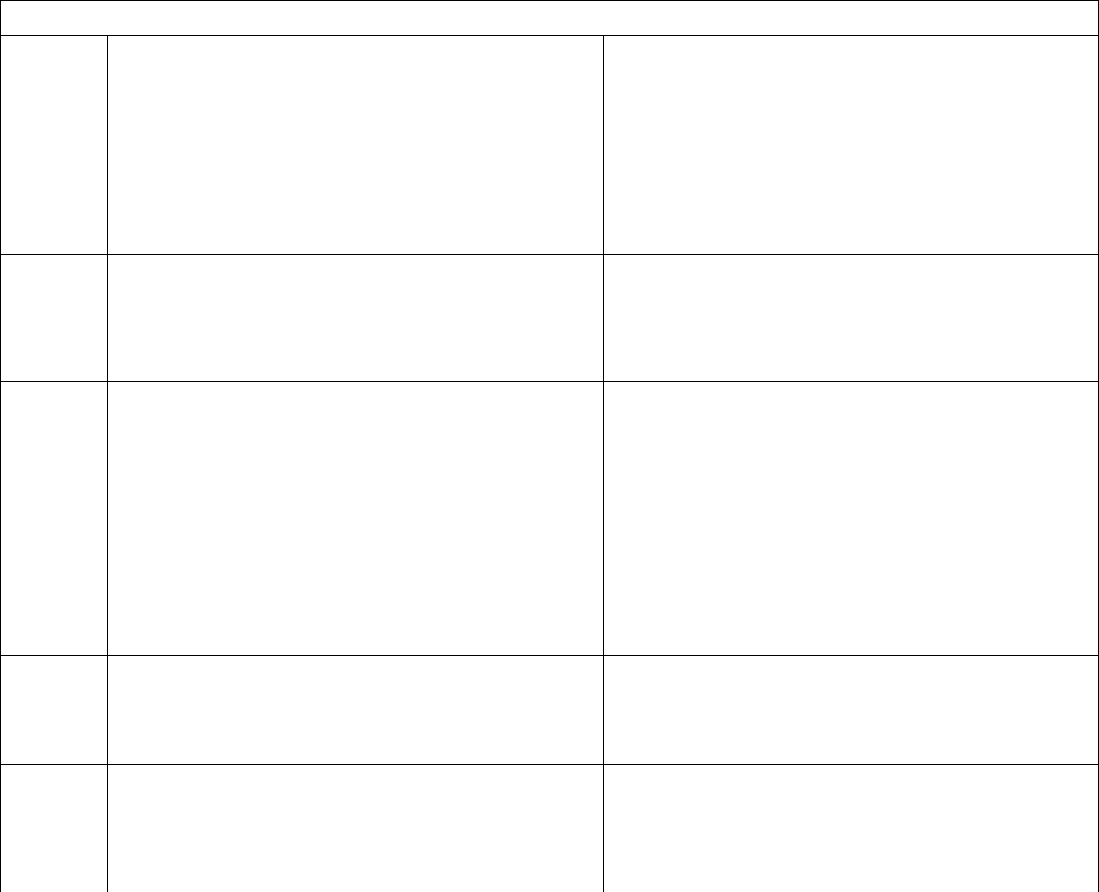

Table 1. Explicit Deposit Insurance Schemes Around the World, end-2013 ..........................32

Table 2. Coverage of Explicit Deposit Insurance Schemes Around the World, end-2013 .....34

Table 3. Design of Explicit Deposit Insurance Schemes Around the World, end-2013 .........37

Table 4. Recent Changes to Depositor Protection, 2007−2013 ...............................................40

Table 5. Fund Size and Coverage of Existing DIS, 2010 ........................................................43

3

I. INTRODUCTION

The recent global crisis tested and tried deposit insurance schemes (DIS), and their ability to

protect household savings in banks. Country authorities and financial regulators reacted to the

extraordinary circumstances of the crisis by expanding the coverage offered in existing deposit

insurance arrangements or adopting deposit insurance where it was not already in place. This

pattern of policy response exposed the adverse distributional effects of generous schemes and

underscored the strengths and weaknesses of different DIS features.

This paper presents a comprehensive database of deposit insurance arrangements through the end

of 2013, covering the IMF membership of 188 countries plus Liechtenstein. For countries with

an explicit deposit insurance scheme, information is provided on the characteristics of the DIS

(such as type, management, coverage, funding, and payouts). For recent years, we add

information on deposit coverage increases, government guarantees on deposits and non-deposit

liabilities, as well as whether a country experienced a significant nationalization of banks. To

assess a country’s ability to honor its deposit insurance (and other safety net) obligations, we

supplement these data with information on the size of potential deposit liabilities, the amount of

DIS funds, and government indebtedness.

While it is too early to draw definitive conclusions about the adequacy of DIS during the recent

global financial crisis, our preliminary assessment is that, by and large, DIS fulfilled its foremost

purpose of preventing open runs on bank deposits. In the face of large shocks to the global

financial system, as well as concerted and protracted concerns about the solvency of practically

every large financial institution in the world, we did not observe widespread bank runs. There

were some notable exceptions (such as Northern Rock in the UK) and there were protracted

withdrawals by uninsured depositors, but the world did not experience systemic bank runs by

insured depositors. From this perspective, DIS delivered on its narrow objective. However, as we

look to what we hope are many post-crisis years, the expansion of the financial safety net (both

through an extended coverage of deposit insurance and increased reliance on government

guarantees and demonstrated rescue propensities to support the financial sector) is something to

worry about. The expansion of national safety nets raises questions about (i) whether government

finances are adequate to support the promises of existing DIS in future periods of stress (the

more so given that governments will likely face renewed pressures to further increase DIS

promises in future crises) and (ii) how to balance the objective of preventing bank runs with the

potentially negative effects of DIS in the form of moral hazard and the threat to financial stability

from incentives for aggressive risk-taking.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the main database, with a

description of each variable included. Section 3 surveys the current state of DIS worldwide.

Section 4 reviews policies undertaken during the financial crisis period to protect depositors

against the loss of value of their deposit savings. Section 5 concludes.

4

II. THE DATABASE

The database builds upon earlier work by Demirgüç-Kunt, Karacaovali, and Laeven (2005). The

original dataset covered deposit insurance schemes through 2003. It was constructed through a

combination of country sources, as well as earlier studies by Garcia (1999), Kyei (1995), and

Talley and Mas (1990), among others.

This version updates the earlier database and extends it to 2013. Whenever possible, we relied on

official sources. Our starting point was a comprehensive survey on financial sector regulations

conducted by the World Bank in 2010. This survey asked national officials for information on

capital requirements, ownership and governance, activity restrictions, bank supervision, as well

as on the specifics of their deposit insurance arrangements. These data were combined with the

deposit insurance surveys conducted by the International Association of Deposit Insurers in

2008, 2010, and 2011, and in the case of European countries with detailed information on deposit

insurance arrangements obtained from the European Commission (2011). Discrepancies and data

gaps were checked against national sources, including deposit insurance laws and regulations,

and IMF staff reports. Information on government actions undertaken during the financial crisis

was collected from Laeven and Valencia (2012), FSB (2010, 2012), Schich (2008, 2009), Schich

and Kim (2011), and IMF staff reports.

Our focus is on deposit insurance for commercial banks. For countries with multiple DIS, the

data provided relate only to the national statutory scheme. This means that stated coverage levels

may understate actual coverage. For example, the complex voluntary DIS for commercial banks

in Germany provides insurance of up to 30 percent of bank capital per depositor, essentially

offering unlimited coverage for most depositors.

The full database, including information on arrangements other than the national statutory

scheme, is available in spreadsheet format as an online Appendix to this paper. The source of the

data is indicated in the appendix. The following section describes the variables used in the

remainder of the paper.

A. Variable Definitions

Type of deposit insurance

We follow Demirgüç-Kunt, Kane, and Laeven (2006) in arguing that a country may be assumed

to offer implicit deposit insurance, given the strength of governmental pressures to provide relief

in the event of a widespread banking insolvency, unless the country has passed formal legislation

or regulation outlining explicit deposit coverage. Indeed, implicit coverage always exists,

regardless of the level of explicit coverage. Countries may have an explicit deposit insurance

scheme without specifying an institution or fund to carry out powers laid out in statutes or

regulation, but the issuance of temporary blanket guarantees by the government is not sufficient

to qualify as having explicit deposit insurance. Hence, we assume that any country that lacks an

5

explicit deposit insurance scheme has implicit deposit insurance. Explicit takes a value of one if

the country has explicit deposit insurance, and zero if implicit. Table 1 lists all countries with

explicit deposit insurance.

Coverage

Explicit deposit insurance schemes typically insure deposits up to a statutory coverage limit.

Particularly during banking crises, countries often issue guarantees on top of pre-announced,

statutory limits. We provide information on both the statutory limits, and the limits taking into

account additional government guarantees. Coverage is the coverage limit in local currency. It

takes on a numerical value or “unlimited” if a full guarantee is in place. Coverage / GDP per

Capita is the ratio of the coverage limit to per capita GDP, expressed as a percentage, and based

on the statutory coverage limit. Table 2 reports these coverage limits both in reported (typically

local) currency and translated in US dollars (using end-of-year exchange rates). Data on GDP per

capita is taken from the April 2014 IMF WEO database, unless otherwise noted. Footnotes

accompanying Table 2 specify the coverage limits for individual countries. For countries with

coinsurance, coinsurance rules are also described.

Organization and administration

The organizational and administrative structures of DIS vary markedly, and this can have an

important bearing on its independence and efficacy. DIS can be organized as a separate legal

entity, or may be placed within a country’s supervisory structure or under the jurisdiction of the

national central bank, or other government ministry such as the Ministry of Finance or

Department of Treasury. These categories are mutually exclusive – any DIS must be legally

separate or located within the central bank, banking supervisor, or government ministry. Some

DIS are organized as separate legal entities but are hosted within and supported by the central

bank. We code such DIS as legally separate. . The variable Type is coded one if the DIS is

legally separate, and two if it is contained within the central bank, banking supervisor, or

government ministry.

Countries may choose an explicit DIS that is administered privately, publicly, or jointly through

some combination of the two. For example, Germany’s two statutory guarantee schemes have a

mixed private/public component where they are privately administered but established in law and

with public elements such as delegated public policy functions and oversight by the supervisory

agency. This choice is often based on country-specific experience with historical banking

failures and on whether private actors exist to potentially administer an explicit DIS (such as, for

example, bankers’ associations in Switzerland). Administration is coded one if the DIS is

administered privately, two if it is administered publicly, and three if it is administered jointly.

These categories are mutually exclusive.

6

Role

While all explicit DIS must include a “paybox” function that provides payout to depositors in the

event of bank failure, countries may also decide to combine the DIS function with resolution

functions or that of banking supervisor or macro-prudential regulator, referred to as “paybox

plus.” Countries may also direct the DIS to minimize losses to the taxpayer, and provide it with

the legal means to do so by granting DIS managers authority to create bridge banks, replace

negligent bank managements, etc. Because the precise role of DIS schemes varies greatly

worldwide, we classify DIS as paybox only or alternatively as a “paybox plus”, including loss or

risk minimizer. These categories are mutually exclusive – DIS can either have a strict paybox

role or have responsibilities beyond the paybox function. Role is coded one if the role of the DIS

is paybox only, and two if it is a paybox plus, loss or risk minimizer.

Multiple systems

Some countries have multiple statutory deposit insurance schemes for different types of financial

institutions. These can be of a public or private nature, and in some cases mean that effective

coverage exceeds that stipulated under the national scheme. Multiple is coded one if multiple

schemes exist within a country, and zero if otherwise. The footnotes to Table 3 provide details on

the names of DIS active in the country, as well the institutions they cover when available. Our

focus is the remainder of the paper is on the main statutory scheme in the country applying to

private commercial banks.

Participation

In a world where finance has become increasingly globalized, differences in coverage among

domestic banks and foreign bank entities operating in the same country have become

increasingly important. For example, during the crisis in Iceland, deposits in foreign branches of

Icelandic banks, which according to EC Directive were to be covered by the Icelandic DIS up to

the statutory minimum of Euro 20,000, were initially not honored by Iceland. Domestic banks

are generally covered by the DIS, but country schemes vary as to whether the locally-chartered

subsidiaries or locally-domiciled branches of foreign banks are covered by the domestic DIS.

Domestic banks equals one if domestic banks are covered, and zero otherwise. For some

countries, such as the United States, the DIS does not base coverage on the home country of the

foreign institution. Elsewhere, such as in EEA (European Economic Area) countries, the DIS

extends coverage also to other countries but only within the EEA, with deposits in foreign

branches being covered by the home-country deposit protection scheme of the bank and deposits

in foreign subsidiaries being covered by the host-country deposit protection scheme. Deposits in

branches of non-EEA banks are generally not covered by the EEA schemes. The variables

Foreign subsidiaries and Foreign branches equal one if the local subsidiaries or, respectively,

local branches of any foreign banks are covered, and zero otherwise.

7

Types of deposits

The DIS typically does not extend the same coverage to all types of deposits. The variable

Foreign currency deposits takes the value one if the DIS covers deposits denominated in any

other currency than the official domestic currency, and zero otherwise. For some countries, this

may include all other currencies, while for others, a limited number of foreign currencies may be

covered. For example, while the DIS within the EU cover deposits in any of the currencies of EU

member states, not all cover deposits in currencies of non-EU member states. For example, the

DIS in Austria, Belgium, Germany, Lithuania, and Malta do not cover deposits in non-EU

currencies. Countries also may set different coverage limits for deposits in domestic or foreign

currencies. In most cases, payments on foreign currency bank deposits, if covered, are made in

local currency.

Coverage of interbank deposits is less common than that of retail deposits, as it is often assumed

that financial institutions are better equipped to monitor the riskiness of the institutions in which

they place deposits than small retail depositors. However, in times of financial market stress,

interbank deposits may be guaranteed to encourage the free flow of liquidity across banks. The

variable Interbank deposits is one if interbank deposits are covered, and zero otherwise.

2

Funding

The primary function of a DIS is to prevent systemic bank runs. In order to do so, the DIS must

be able to credibly claim that it can and will pay depositors in the event of bank failure.

Countries can choose to fund potential payouts either ex ante or ex post. Most DIS with ex ante

funding collect premiums on a scheduled basis, while ex post schemes collect funds from

surviving institutions only when a covered bank fails and the available funds to cover depositors

prove insufficient. These categories are mutually exclusive. Funding equals one if funding is ex

ante and two if funding is ex post.

In addition to choosing between ex ante or ex post funding, DIS can also be funded by the

government, privately by covered institutions, or jointly between the government and private

actors. These categories are mutually exclusive. Countries such as Portugal with DIS primarily

funded by participating banks that have had government funding provided are classified as

funded jointly. Funding source is coded one if funding is by government, two if done privately,

and three if done jointly. Government funding refers both to start-up and ongoing funding. In the

case of ex post schemes, funding source refers to who pays the contributions to cover depositor

payouts (typically the surviving banks). Backstop funding is considered separately in what

follows. Depending upon a government’s ability to collect taxes or issue new debt, government-

funded schemes may credibly promise to address bank failures in a timely fashion, but they may

2

In some countries, coverage could also exclude legal entities and central and local governments. We do not

consider these exceptions.

8

face internal pressure to avoid paying out taxpayer funds in the event of a large failure. Privately-

funded schemes may encourage peer monitoring among institutions, but may more easily run

short of available funds to credibly pay out depositors in the event of systemic failures.

Government support

While the primary funding mechanism of a DIS may not be the government, some countries

provide contingency plans in the case of a shortfall of funds to cover deposits that include

government support. For some countries, this takes the form of pre-approved credit lines from

the Department of Treasury. For others, the DIS can issue bonds or receive loans guaranteed by

the government. Backstop is coded one if in legislation or regulation any such form of

government support in case of a shortfall of funds explicitly exists, and zero otherwise.

Government support includes only support from the central government, not support from the

central bank.

Risk-adjusted premiums

In addition to raising funds to cover future payouts, some DIS use differential premiums to curb

risk-taking by financial institutions. Procedures for assessing risk vary across countries. For

example, in Italy, banks are first grouped into six risk categories using four indicators of bank

risk and performance. Then, these risk categories are mapped into six different levels of risk-

adjusted premiums. In Greece, starting in January 2009, annual premiums are adjusted by a risk

coefficient that ranges between 0.9 and 1.1, as dictated by the bank’s placement into one of three

risk categories by the Bank of Greece. Risk assessment is based on measures of the bank’s

solvency, liquidity, and the efficiency of its internal control systems. Risk-adjusted premiums is

coded one if premiums are adjusted for risk, and zero otherwise.

Assessment

Countries can choose to assess premiums on a variety of balance-sheet items. Assessment base

denotes the base over which premiums are assessed. We classify the assessment base of

premiums into four mutually exclusive categories – covered deposits, eligible deposits, total

deposits, and total liabilities. Eligible deposits refers to deposits repayable by the deposit

insurance scheme, before the level of coverage is applied, while covered deposits are obtained

from eligible deposits when applying the level of coverage. The footnotes to Table 3 provide

greater detail on the assessment base. For example, as stipulated by the Dodd-Frank Act the US

FDIC changed the assessment base from total domestic deposits to average total assets minus

tangible equity (i.e., Tier 1 capital), as a way to shift the balance of the cost of deposit insurance

away from small banks to large banks that rely more on non-deposit wholesale funding.

Payouts

The most common form of DIS coverage is coverage at the “per depositor per institution” level.

However, some countries cover deposits per depositor, or per depositor account. Coverage per

9

depositor account is more generous than coverage per depositor per institution because it allows

depositors to increase their effective coverage by opening multiple accounts within the same

institution, while coverage per depositor per institution is more generous than coverage per

depositor because it allows depositors to increase their effective coverage by placing deposits in

multiple institutions. Some countries, such as the United States, have coverage per depositor per

institution for individuals, but treat joint accounts separately from individual accounts, such that

individual depositors with joint accounts can double their effective coverage (relative to the

statutory limit) within the same institution. Payouts to depositors is coded one if the coverage is

per depositor account, two if per depositor per institution, and three if per depositor. Table

footnotes provide further details for countries with a more complicated structure.

Sometimes DIS have insufficient funds or otherwise impose losses on depositors (in nominal

terms). We identify only three cases where substantial losses were imposed on insured deposits

(including losses in nominal terms) despite the existence of explicit deposit insurance –Argentina

(1989 and 2001), and Iceland (2008).

3

Deposit losses is coded one for these countries, and zero

otherwise. Further details about each episode are provided in the footnotes to Table 3.

Banking crises

We also collect information on whether the country experienced a banking crisis between 2007

and 2012. Banking crisis date denotes the year that the country experienced a banking crisis.

Banking crisis dates for the period 2007-2011 are according to Laeven and Valencia (2012).

Cyprus is added to this list as of 2012.

Introduction of deposit guarantee scheme

During the financial crisis period, several countries introduced explicit deposit insurance

schemes (e.g., Australia and Singapore), or transitioned from unlimited government guarantees

already in place before the onset of the crisis into an explicit DIS with capped coverage limits

(e.g., Thailand). Introduction is coded one if the country introduced an explicit deposit insurance

scheme during the period 2008-2013, and zero otherwise.

Increase in statutory deposit coverage

Many countries raised coverage limits during the crisis. For some, raising coverage was a result

of ex ante decisions to index coverage limits to inflation-adjusted units, currency pegs, or

measures of income such as a multiple of the minimum wage. For other countries, coverage

limits were raised to discourage deposit outflows from the banking system. Within the EU in

particular, policies emphasizing convergence and harmonization in deposit insurance coverage

3

We do not consider losses on uninsured deposits, including eligible deposits above the coverage limit. For

example, in March 2013, Cyprus imposed substantial haircuts on uninsured depositors in the country’s two largest

banks, which were assessed to be insolvent, and one of which was subsequently wound down.

10

limits across countries resulted in large coverage increases. Other countries expanded the range

of accounts covered to include foreign currency or interbank deposits. Increase in coverage is

coded one if there was increase in coverage limits during the period 2008-2013, and zero

otherwise. Table 4 specifies all countries that introduced temporary increases in coverage during

the recent financial crisis.

Abolishment of co-insurance

In the pre-crisis period, co-insurance had gained popularity in some countries as a way to

preserve the financial stability benefits of an explicit DIS, while preserving some of the

monitoring incentives inherent in a system without formal coverage of deposits. With co-

insurance, depositors are insured for only a pre-specified portion of their funds (i.e., less than

100 percent of their insured deposits).For example, in a country with 20 percent co-insurance and

a maximum coverage limit of $100, depositors with less than $125 would receive 80 percent of

the money within their account. Depositors with any amount greater than $125 (where 80 percent

is the maximum of $100) would receive only $100. During the crisis, this disciplining

mechanism proved politically difficult to maintain. Sixteen countries had co-insurance in 2003 –

by 2010, only three remained. Coinsurance is coded one if co-insurance was abolished during

the period 2008-2013, and zero otherwise.

Government guarantee on deposits

Alongside increases in the statutory coverage of deposits, several countries instituted a

temporary unlimited guarantee on deposits. Government guarantee on deposits is coded one if a

(partial or full) government guarantee on deposits was put in place during the period 2008-2013,

and zero otherwise. Further details on specific deposit guarantees are provided in the footnotes to

Table 5.

We distinguish between whether the deposit guarantee covered only some deposits (Limited) or

all deposits (Full), and indicate the year when the guarantee was introduced (In place) and when

the guarantee expired (Expired).

Government guarantee on non-deposit liabilities

In addition to providing extended coverage for deposit accounts, many countries that

experienced a systemic banking crisis during the global financial crisis extended guarantees on

the non-deposit liabilities of financial institutions. For some countries, the guarantees were

limited to a small number of major institutions (Ireland). Other countries guaranteed specific

debt classes, or only new debt issuances (Republic of Korea, United States), while others

provided unlimited guarantees (Australia). Further details on the types of non-deposit guarantees

are provided in the footnotes to Table 5. Guarantee on non-deposit liabilities is coded one if

there were government guarantees applied to non-deposit liabilities during the period 2008-2013,

and zero otherwise.

11

Government guarantee on bank assets

In addition to guaranteeing bank deposits and other bank liabilities, some governments also

resorted to guaranteeing particular asset classes of banks’ balance sheets. For example, the

governments of the Netherlands and Switzerland guaranteed the asset values of some hard-to-

value assets on the balance sheets of ING and UBS, respectively. Guarantee on bank assets is

coded one if there were government guarantees on banking assets during the period 2008-2013,

and zero otherwise.

Significant nationalizations of banks

Government intervention during the financial crisis also included the government taking control

over financial institutions through nationalizations. Significant nationalization of banks is

coded one if there was significant nationalization of banks and other financial institutions since

2008. Nationalizations are defined broadly to include explicit nationalizations as well as cases

where the government takes control over financial firms through the acquisition of a majority

ownership stake or by placing government-sponsored enterprises into receivership.

4

We identify

17 countries where a significant portion of the financial system was nationalized since 2008

(including, for example, Belgium, Iceland, Ireland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and

the United States). While coverage limits may not have explicitly increased, nationalization

implies an implicit government backstop of all deposits within these institutions (and a reduction

in counterparty risk to these institutions for the rest of the financial system), as well as a

contingent future liability for these national governments.

III. MAIN FEATURES OF DEPOSIT INSURANCE SCHEMES AROUND THE WORLD

The number of countries with explicit deposit insurance schemes has continued to increase. Out

of 189 countries covered, 112 countries (or 59 percent) had explicit deposit insurance by year-

end 2013, having increased from 84 countries (or 44 percent) in 2003. The 2008 global financial

crisis contributed to this trend, with 5 countries adopting deposit insurance in the year 2008

alone. Australia, long an advocate of implicit deposit insurance, was a notable example among

those countries that joined the ranks of those with explicit deposit insurance in 2008. Another

force has been the EU-driven harmonization process of deposit insurance, which spurred the

adoption of explicit deposit insurance throughout Central and Eastern Europe.

Deposit insurance is particularly widespread among high income countries. About 84 percent of

countries with high incomes had explicit deposit insurance by year-end 2013. Israel and San

Marino are notable exceptions among high income countries with implicit deposit insurance.

4

For example, nationalizations of financial institutions in the United States include putting Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac into receivership and the government acquiring a majority stake in AIG.

12

Explicit deposit insurance is less widespread among low income countries, at about 32 percent of

countries (see Figure 1).

Similarly, there is regional variation in the existence of explicit deposit insurance. In Europe,

almost all countries (or 96 percent of countries) have deposit insurance (the only two exceptions

are Israel and San Marino). Explicit deposit insurance is less widespread in other parts of the

world, with only 24 percent of countries in Africa having explicit deposit insurance (see Figure

2).

Deposit insurance schemes also vary markedly in how they are designed. Table 3 lists the main

features of existing deposit insurance schemes, with countries listed alphabetically.

Most explicit deposit insurance schemes are pre-funded, an arrangement that is commonly

described as an ex ante scheme, and contrasted with an ex post scheme. Ex ante schemes

maintain a fund that typically receives and accumulates contributions from covered banks. Ex

post schemes, on the other hand, collect premiums from surviving banks only if payouts from the

scheme occur, i.e., if a bank is declared insolvent and depositors need to be reimbursed. Of all

countries with explicit deposit insurance, 88 percent have an ex ante scheme (Figure 3). Ex post

schemes exist in about one-fourth of high income countries but are altogether absent in low

income and lower middle income countries. Notable examples are Austria, Chile, Italy, the

Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK.

5

The purpose of many deposit insurance funds is simply to reimburse insured depositors in the

event of bank insolvency. Such a fund is known as a paybox. Other funds have additional

responsibilities, varying from licensing of banks, supervisory authority, and ability to collect

information from banks. About 43 percent of all deposit insurance funds in ex ante schemes are a

paybox, while the remaining 57 percent of funds have extended powers or responsibilities,

including a responsibility to minimize losses or risks to the fund (Figure 4).

The majority of explicit schemes are legally separate from the central bank, banking supervisory

agency, or ministry of finance, even though they may be “housed” within such institutions; only

a minority of 14 percent of schemes is not legally separate from these government institutions

(Figure 5). This number varies by income level, and is slightly higher in low income countries

(27 percent).

Most deposit insurance schemes are administered publicly (about 66 percent of all schemes) but

there is wide variation across countries’ income levels. In low income countries, 82 percent of all

schemes are administered publicly. In high income countries, on the other hand, only 44 percent

5

In 2011, the Netherlands adopted a plan to transform its ex post DIS into an ex ante funded scheme with risk-based

contributions. This transformation is scheduled to come into effect on July 1, 2015.

13

of schemes are administered publicly, while 21 percent of schemes are administered privately

(by covered banks), while the remaining 35 percent of schemes are administered jointly between

the public and private sectors (Figure 6).

Funding of deposit insurance schemes derives primarily from contributions from the insured

banks, although some schemes are funded in part or in whole by their government. Joint funding

typically consists of start-up capital provided by the government with ongoing contributions

from participating banks. 77 percent of all schemes are funded privately, while 2 percent of

schemes are funded exclusively by the government, and the remaining 21 percent of schemes are

funded jointly. However, there is substantial variation across countries, with 91 percent of

schemes in high income countries being funded by the private sector (Figure 7).

Coverage limits also vary markedly across countries, both in absolute level and relative to per

capita income, especially when other government guarantees are accounted for (see Table 2 and

Figure 8). For example, statutory coverage limits range from a low of US$460 in Moldova to

highs of US$250,000 in the United States, US$327,172 in Norway, US$1,523,322 in Thailand

(where a blanket guarantee on deposits is being phased out), and full guarantees on deposits in

Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Figure 8 shows that coverage increased sharply during the recent financial crisis (in part

reflecting the announcement of government guarantees on deposits) and was subsequently

reduced, although coverage levels on average remain above pre-crisis levels. By end-2013,

coverage limits on average amount to 5.3 times per capita income in high income countries, 6.3

times per capita income in upper middle income countries, 11.3 times per capital income in

lower middle income countries, and 5.0 times per capita income in low income countries.

Co-insurance, while relatively common prior to the recent financial crisis, has almost

disappeared as a feature of deposit insurance schemes, despite its loss-sharing appeal. The reason

is that co-insurance rules were not enforced during the crisis to avoid imposing any losses on

small depositors. It was feared that such losses might jeopardize depositor confidence and

financial stability generally. Once the crisis abated, these co-insurance rules – having lost

credibility – have not been reintroduced. While in 2003 a total of 16 deposit insurance schemes

had co-insurance, this number dwindled to 3 by the end of 2013 (Figure 9). The only three

remaining schemes with coinsurance are those of Bahrain, Chile, and Libya.

Adjusting deposit insurance premiums for risk, on the other hand, has been on the rise. By end-

2013, 31 percent of schemes adjusted premium contributions for risk (Figure 10). There is not

much variation across income levels in the use of risk adjustments. Risk assessment methods

varied widely across countries, though.

Many deposit insurance schemes (about 38 percent of all schemes) enjoy government backstops

in case of a shortfall in funds, mostly in the form of credit lines or guarantees on debt issuances

14

from the Treasury (Figure 11). The presence of such backstops is slightly higher in high income

countries that tend to be in a better position to afford such guarantees (although this depends on

the size of the financial sector in these countries).

IV. DEPOSITOR PROTECTION DURING THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS

In an effort to contain the fallout from the global financial crisis, many countries expanded their

financial safety net, both by increasing coverage of deposit insurance and by extending

government guarantees to non-deposit liabilities (and in some cases on bank assets).

Figure 12 summarizes the increase in deposit protection since 2008, reporting the percentage of

countries that either introduced an explicit deposit insurance scheme or expanded deposit

protection in one of six ways: (a) increasing statutory coverage; (b) abolishing co-insurance; (c)

introducing a government guarantee on deposits (either limited or full); (d) introducing a

government guarantee on non-deposit liabilities; (e) introducing a government guarantee on bank

assets; or (f) undertaking significant nationalizations of banks. We report these actions separately

for crisis and non-crisis countries.

The expansion of the safety net was substantial, especially for crisis countries, and extended

beyond traditional deposit insurance. Fourteen countries introduced explicit deposit insurance

since 2008, and almost all countries with explicit deposit insurance that experienced a banking

crisis over this period increased the statutory coverage limit in their deposit insurance scheme

(96 percent of countries to be precise). Government guarantees on deposits were introduced in 32

percent of countries with deposit insurance and experiencing a banking crisis. 38 percent of these

deposit guarantees were blanket guarantees, guaranteeing deposits in full. Government

guarantees on bank liabilities were particularly widespread, especially among countries with

deposit insurance experiencing a banking crisis (72 percent of these countries extended

guarantees on bank liabilities). These guarantees varied from extending guarantees on debt

issuances to blanket guarantees on all debt liabilities. Government guarantees on bank assets

were used in 36 percent of countries with deposit insurance experiencing a banking crisis. Bank

nationalizations were also widespread, occurring in 64 percent of countries with deposit

insurance experiencing a banking crisis.

A number of insights can be gained from the crisis experience.

Together with central bank action in the form of extensive liquidity support and monetary easing,

deposit insurance schemes contributed to preventing open bank runs. For example, extensive

liquidity support to banks from the Federal Reserve combined with a credible fiscal backstop

from the US Treasury to the FDIC prevented a generalized run from FDIC-insured bank deposits

into currency. Federally uninsured savings in money market funds with reported a stable $1 net

asset value had a very different experience. Accounts in these funds became federally insured

temporarily when the crisis intensified in September 2008. Money market funds experienced

massive outflows (mainly into US banks) once it became publicly known (on September 16,

15

2008) that the Reserve Primary Fund was in trouble. And in Europe, despite diverging

macroeconomic fundamentals between the core and the periphery of the eurozone countries,

insured bank deposits remained remarkably stable in most countries, with the exception of (1)

isolated bank runs (Northern Rock in the UK and DSB Bank in the Netherlands) that were

quickly contained, (2) a slow moving “run” on deposits in Greece on the back of growing fears

of a euro breakup (total deposits declined by about 20 percent between 2010 and 2012), and (3) a

generalized run in Cyprus where authorities had declared that a tax on insured deposits could be

imposed (although this eventually did not materialize).

However, runs on uninsured deposits and non-deposit liabilities were widespread. For example,

there was a significant run on wholesale deposits and a repo run on broker dealers in the US.

These runs created severe stress in bank funding markets that had come to increasingly rely on

short-term wholesale funding. This interconnectivity between banks and markets implies that

funding shocks in capital markets can quickly spill over to banks and funding shocks to banks

can spill over into capital markets, threatening the stability of the financial system and the real

economy. The systemic risk that spillovers pose underscores the dangers of insuring wholesale

deposits and deposit-like instruments and extending the perimeter of the financial safety net to

nonbanks.

At the same time, many DIS were inadequately designed to stem the buildup of risk in the

banking system either by nurturing market discipline or by seeking compensation for the risks

being transferred to them. Co-insurance, a way to introduce market discipline, was largely

phased out by most countries prior to the crisis. Nor did DIS premiums adequately reflect tail

risk, effectively subsidizing potentially ruinous risk taking by banks.

6

For example, about 97

percent of banks were assigned the lowest risk category in the US and were being charged a zero

percent explicit premium for deposit insurance during the run-up to the crisis. And the majority

of ex ante funds was small relative to the amount of insured deposits and was well below their

target sizes.

To maintain public confidence in the banking system during the crisis, many countries raised

deposit insurance coverage and introduced government guarantees on additional bank assets and

liabilities. These measures generally seem to have had the intended beneficial short-run effect,

although questions surfaced about the ability of some governments to honor their expanding

obligations. For example, within the EU, national deposit insurance schemes nominally cover a

minimum coverage limit determined at the EU level. Growing uncertainty emerged about the

ability of peripheral European countries with sovereign debt problems to honor these obligations,

causing some deposit flight to banks in countries with stronger sovereigns, such as Germany.

6

The failure of DIS premiums to reflect tail risks does not necessarily reflect an inadequate design of DIS. It could

also simply be a result of a general failure to assess financial sector risks.

16

The issue is much broader though than that faced in these troubled economies. Many DIS appear

underfunded, especially in countries with large financial systems. Table 5 highlights the

imbalances between the ability to pay and potential liabilities from deposit insurance. The table

contrasts the amount of coverage promised with the amounts of funds available (from bank

contributions) and the government debt-to-GDP ratio, which we use as an inverse proxy for the

ability of a government to expand its debt to backstop the DIS fund in individual countries. The

size of the DIS fund seldom exceeds the percentage of deposits covered by DIS, leading one to

wonder whether sufficient funds would be available to pay off depositors quickly in a large

failed bank without resorting to additional public funding (see also Figure 13). More generally,

the sizeable amounts of bank deposits relative to GDP combined with high levels of government

indebtedness in some countries raise doubts about the ability of governments in these countries

to backstop the financial safety net (Figure 14).

An additional complication that came to the fore during the crisis is the potentially different

treatment of foreign and domestic depositors. For example, Iceland chose not to honor its deposit

insurance obligations to foreign depositors when faced with a banking crisis at home. And in

Europe, there are growing concerns especially among large corporate depositors about being

“bailed in” during bank rescues.

To measure the generosity of the deposit insurance scheme and the existence of government

guarantees on bank assets and liabilities, we create a safety net index, similar to the moral hazard

index in Demirgüç-Kunt and Detragiache (2002).

The safety net index is computed using principal component analysis of standardized design

feature variables that each are increasing in moral hazard. Specifically, we use the following

design features: Coverage limit / GDP per capita and dummy variables for unlimited government

guarantees in place, coverage of foreign currency deposits, coverage of interbank deposits, no

co-insurance, payouts to depositors (per deposit account=2; per depositor per institution=1; per

depositor=0), no risk-adjusted premiums, ex ante fund, funded by government, backstop from

government, no losses imposed on uninsured deposits, government guarantees on bank deposits

(limited or full), government guarantees on non-deposit liabilities since 2008, and government

guarantees on bank assets since 2008. Each of these variables is constructed such that higher

values denote more generosity or greater government support and imply more moral hazard. This

set expands the set of deposit insurance variables used by Demirgüç-Kunt and Detragiache

(2002) by including information on government guarantees in the financial sector. As such, the

index captures moral hazard generated by the financial safety net at large, not deposit insurance

in a strict sense. The safety net index (SNI) is the sum of the first six principal components for

which the eigenvalues exceed 1.

Figure 16 reports the values of our SNI index, with higher values denoting more generosity, and

consequently more moral hazard. We observe much country variation in the SNI index. It ranges

from lows of -11.9 in Argentina and -10.5 in Iceland (which both have imposed losses on insured

17

depositors) to highs of 4.6 in Ireland and the United States (both of which issued temporary

guarantees on deposits and non-deposit liabilities during the recent crisis) and 4.5 in

Turkmenistan and 7.8 in Uzbekistan (both of which have blanket guarantees). Some of these

countries will be able to fund such generous safety nets promises, but the fairness and efficiency

of imposing such a burden on households and nonfinancial firms is questionable. And the moral

hazard it creates is hard to contain as evidenced in the difficulty of eliminating the too big to fail

problem.

Going forward, important questions remain about how to restore market discipline. The problem

is the perverse incentives generated by expectations that in future crises authorities will adopt the

same policies of increasing coverage and creatively expand the financial safety net even further.

Expectations that bailouts will again be the tool of choice in future crises complicate the role and

effectiveness of deposit insurance limitations.

Academic research prior to the crisis generally advocated a limited role for deposit insurance,

underscoring the moral hazard incentives associated with overly generous coverage. Concerns

about moral hazard led to policy recommendations for low coverage-to-income limits, co-

insurance schemes, and the exclusion of wholesale deposits (e.g., Demirgüç-Kunt and

Detragiache, 2002, and Demirgüç-Kunt and Huizinga, 2004).

Using data on deposit insurance design features before the recent global financial crisis, Anginer,

Demirgüç-Kunt, and Min (2014) examine the relation between deposit insurance, bank risk, and

systemic fragility across a large number of countries in the years leading to and during the crisis.

They show that generous financial safety nets increase bank risk and systemic fragility in the

years leading up to the crisis (the moral hazard effect), however during the crisis, bank risk is

lower and systemic stability is greater in countries with deposit insurance coverage (the

stabilization effect). Consistent with the earlier literature, they find that the overall effect of

deposit insurance over the full sample remains negative, suggesting that the destabilizing effect

due to moral hazard is greater in magnitude compared to its stabilizing effect during periods of

financial turbulence.

However, less attention was paid to the political economy problems that plague deposit insurance

at times of a crisis.

7

When faced with a crisis, governments quickly rewrote existing statutes so

that DIS managers worldwide could increase coverage limits, abolish coinsurance, and extend

guarantees on non-deposit liabilities. Because this kind of support is funded as a contingent

liability, neither the DIS nor the national governments felt an immediate fiscal repercussion.

These actions could be performed easily and quickly in the name of financial stability. None of

these increases in potential liabilities passed through official government budgets. And because

7

What Kane (1989) calls the “proliferation of hopelessly insolvent zombie institutions simultaneously gambling for

resurrection.”

18

they were not accompanied by increased premiums or other measures to rein in risk-taking by

the insured (such as ex post levies on banks), the banks being rescued did not complain either.

The problem is that these political economy considerations are not symmetric. Once in place, it

is politically very hard to unwind guarantees and especially difficult to decrease DIS coverage,

when and as a crisis abates. And while premiums can be gradually increased on banks to recoup

part of the subsidy passed through the financial safety net from the bailout policies, the problem

is that it is never easy to recoup these costs only from surviving banks who often have even more

political clout than before the crisis occurred. Their clout helps to persuade authorities to hold

post-crisis premiums below actuarially fair levels, not only to lower the burden on the banks, but

to support credit growth and macroeconomic recovery.

Some would argue that a gradual move to bail-in policies to replace the bail-out of senior

uninsured debtholders and uninsured depositors would protect against contingent liabilities for

governments arising from the financial safety net. Indeed, several countries have made steps in

this direction by adopting rules that would impose losses on such private creditors in the event of

a bank failure. The problem with these rules is that they are time inconsistent: the temptation to

renege on bail-in policies in the midst of a systemic crisis, when creditor panic and contagion

risk rises to dangerous levels, will be too high for many governments.

The evidence also implies that it is difficult to use a DIS as a source of monitoring and market

discipline during a systemic banking crisis. In the years leading up to the financial crisis, many

countries had chosen prudently low levels of deposit coverage and/or introduced explicit

coinsurance in an attempt to encourage monitoring of financial institutions by retail depositors

and by one another. In 2003, many countries had co-insurance, but by 2013, only three countries

did. The evidence indicates that the explicit coverage limits that are set in normal times are not

time-consistent. This is particularly problematic in environments with weak frameworks for

resolving the affairs of insolvent financial firms. In such countries, regulators and supervisors

cannot readily ignore budgetary and political pressures to intervene in distressed banks. It is

therefore important for governments to monitor, assess, and report fiscal risks related to DSI.

Following the crisis both the size of explicit government contingent liabilities related to DSI and

the probability of these contingent liabilities materializing have increased. This calls for reforms

to contain and mitigate these contingent liability risks.

V. CONCLUDING REMARKS

Deposit insurance, long a topic for narrow specialists, became a hot policy topic during the

global financial crisis. Countries that could afford to do so broadened deposit insurance coverage

and enlarged their financial safety net to restore confidence in their financial system. Only a few

less fortunate countries broke their promises on insured deposits (as in the case of Iceland) or

imposed substantial losses on uninsured depositors (as in the case of Cyprus).

19

This paper presents a comprehensive database of features of existing deposit insurance

arrangements and government guarantees on bank assets and liabilities, together with a

preliminary analysis of the effectiveness of these arrangements during the global financial crises.

This analysis suggests that deposit insurance arrangements were largely effective in preventing

large-scale depositor runs, but have never correctly priced risk. This underpricing of deposit

insurance is at least as likely to encourage potentially ruinous risk taking by banks in the future

as it has in the past. The expansion of the safety net during the crisis intensifies questions about

the ability of countries to honor their obligations and about moral hazard going forward.

At the same time, the increasing reliance on short-term wholesale funding for banks and their

links to securities, futures, and derivatives markets raise doubts about whether the government

should also protect deposit-like instruments to prevent runs on wholesale funding to spill over to

traditional banking markets. A generous safety net raises deep problems that must not be

ignored: concerns about moral hazard, distributional fairness, and ability to pay. These concerns

are apt to be particularly pressing in countries whose financial systems are large relative to the

size of their economy.

A gradual move to bail-in policies of uninsured depositors and debtholders would help ensure

that governments are able to honor payments out of generous DIS, though contagion concerns,

too big to fail considerations, and other political economy constraints may get in the way of

efforts to bail in such creditors during a systemic crisis.

A more comprehensive analysis of these issues is needed and we hope that publishing this

database will facilitate such research.

20

REFERENCES

Anginer, D., A. Demirgüç-Kunt, and M. Zhu, 2014, “How Does Deposit Insurance Affect Bank

Risk? Evidence from the Recent Crisis,” Journal of Banking and Finance; also World

Bank Policy Research Paper, WPS6289.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and International Association of Deposit

Insurers (IADI), 2009, “Core Principles for Effective Deposit Insurance Systems,”

https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs156.pdf

Blinder, A.S., and R.F. Wescott, 2001, “Reform of Deposit Insurance: A Report to the FDIC,”

FDIC and Princeton University. Mimeo.

http://www.fdic.gov/deposit/insurance/initiative/reform.html

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., and E. Detragiache, 2002, “Does Deposit Insurance Increase Banking

System Stability? An Empirical Investigation,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 49,

No. 7, pp. 1373-1406.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., and H. Huizinga, 2004, “Market Discipline and Deposit Insurance,” Journal

of Monetary Economics, Vol. 51, No. 2, pp.375-399.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., B. Karacaovali, and L. Laeven, 2005, “Deposit Insurance around the World:

A Comprehensive Database,” Policy Research Working Paper No. 3628 (Washington,

DC: World Bank).

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., E.J. Kane, and L. Laeven, 2008a, “Determinants of Deposit-Insurance

Adoption and Design,” Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 407-438.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., E.J. Kane, and L. Laeven (Eds.), 2008b, Deposit Insurance around the

World: Issues of Design and Implementation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

European Commission, 2004, Report on minimum guarantee level of Deposit Guarantee

Schemes Directive 94/19/EC,

http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/guarantee/report_en.pdf. Annex available

from: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/guarantee/annexes_en.pdf

European Commission, 2010, Impact Assessment for Proposal on Deposit Guarantee Schemes,

http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/guarantee/20100712_ia_en.pdf. Annex II

available from: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/guarantee/jrc-

annex2_en.pdf

European Commission, 2011, JRC Report under Article 12 of Directive 94/19/EEC,

http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/guarantee/jrc-rep_en.pdf. Annex I and II

21

available from: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/guarantee/jrc-

annex1_en.pdf and http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/guarantee/jrc-

annex2_en.pdf.

European Federation of Deposit Insurance, 2006, Deposit Guarantee Systems: EFDI’s First

Report,

http://efdi.eu/fileadmin/user/publications/EFDI%20publications/Deposit%20Guarantee%

20Systems%20EFDIs%20First%20Report%20%28Manuela%20De%20Cesare%202006

%29.pdf

Financial Stability Board, 2012, Thematic Review on Deposit Insurance Systems,

http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_120208.pdf

Financial Stability Board, 2010, Update on Unwinding Temporary Deposit Insurance

Arrangements, http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_1006.pdf

Garcia, G., 2000, Deposit Insurance: Actual and Good Practices, IMF Occasional Paper No. 197

(Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

International Association of Deposit Insurance, 2008, 2008 Annual Survey Results of Deposit

Insurance, http://www.iadi.org/Research.aspx?id=58

International Association of Deposit Insurance, 2010, 2010 Annual Survey Results of Deposit

Insurance, http://www.iadi.org/Research.aspx?id=58

International Association of Deposit Insurance, 2011, 2011 Annual Survey Results of Deposit

Insurance, http://www.iadi.org/Research.aspx?id=58

Kane, E.J., 1989, The S&L Insurance Mess: How Did it Happen? (Washington, DC: The Urban

Institute Press).

Laeven, L., 2013, European Union: Publication of Financial Sector Assessment Program

Documentation—Technical Note on Deposit Insurance, IMF Country Report No. 13/66

(Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2013/cr1366.pdf

Laeven, L., and F. Valencia, 2012, “Systemic Banking Crises Database: An Update,” IMF

Working Paper no. 12/163 (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12163.pdf

22

Schich, S., 2008, “Financial Crisis: Deposit Insurance and Related Safety Net Aspects,”

Financial Market Trends, OECD. http://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-

markets/41894959.pdf

Schich, S., 2009, “Expanded Guarantees for Banks: Benefits, Costs, and Exit Issues,” Financial

Market Trends, OECD. http://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-markets/42779438.pdf

Schich, S., and B.-H. Kim, 2011, Guarantee Arrangements for Financial Promises: How Widely

Should the Safety Net Be Cast? Financial Market Trends, OECD.

http://www.oecd.org/finance/financial-markets/48297609.pdf

World Bank, 2003, Survey of Banking Supervision and Regulation,

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTRES/Resources/469232-

1107449512766/Caprio_2003_banking_regulation_database.xls

World Bank, 2011, Survey of Banking Supervision and Regulation,

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTGLOBALFINREPORT/Resources/8816096-

1346865433023/8827078-1347152290218/Bank_Regulation.xlsx

23

Figure 1. Explicit Deposit Insurance by Income Group, 2013

Figure 2. Explicit Deposit Insurance by Region, 2013

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

High

income

Upper

middle

income

Lower

middle

income

Low income

Implicit (%)

Explicit since 2003 (%)

Explicit (%)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Africa

Asia-Pacific

Europe

Middle East

and Central

Asia

Western

Hemisphere

Implicit (%)

Explicit since 2003 (%)

Explicit (%)

24

Figure 3. Type of DI Scheme, 2013

Figure 4. Objective of the DI Scheme, 2013

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

High income

Upper middle

income

Lower middle

income

Low income

ex-post scheme

ex-ante fund

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

High

income

Upper

middle

income

Lower

middle

income

Low income

paybox with extended

powers, or loss or risk

minimizer

paybox

25

Figure 5. Organization of the DI Scheme, 2013

Figure 6. Administration of the DI Scheme, 2013

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

High

income

Upper

middle

income

Lower

middle

income

Low

income

organization of scheme:

central bank, supervisor,

or ministry

organization of scheme:

legally separate

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

High

income

Upper

middle

income

Lower

middle

income

Low

income

administration of scheme:

administered jointly

administration of scheme:

administered publicly

administration of scheme:

administered privately

26

Figure 7. Funding of the DI Scheme, 2013

Figure 8. Coverage Increased During Crisis and Remains Above Pre-Crisis Levels

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

High

income

Upper

middle

income

Lower

middle

income

Low

income

funded jointly

funded by government

funded privately

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

High

income

Upper

middle

income

Lower

middle

income

Low income

Coverage limit / GDP per

capita, 2003

Coverage limit / GDP per

capita, 2010

Coverage limit / GDP per

capita, 2013

27

Figure 9. Decline of Coinsurance, 2003−2013

Figure 10. Risk Adjustment of DI Premiums, 2013

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

High income

Upper middle

income

Lower middle

income

Low income

Number of DIS with coinsurance

2003

2013

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

High

income

Upper

middle

income

Lower

middle

income

Low

income

no risk-adjusted

premiums

risk-adjusted premiums

28

Figure 11. Government Support of DI Schemes, 2013

Figure 12. Increase in Depositor Protection, 2007−2013

% of countries with explicit DIS

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

High income

Upper

middle

income

Lower

middle

income

Low income

no backstop from

government

backstop from

government

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Banking crisis

between 2007

- 2013

No banking

crisis between

2007 - 2013

29

Figure 13. Potential Deposit Liabilities and Ability to Pay by the DIS Fund, end-2010 1/

1/ Middle income includes lower and upper middle income countries. Insufficient data to report figures on low

income countries.

Figure 14. Total Deposits and Ability to Pay by the Government, end-2010 1/

1/ Middle income includes lower and upper middle income countries. Insufficient data to report figures on low

income countries.

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

High income

Middle income

Size of DIS Fund /

Covered Deposits (%)

0

50

100

150

200

250

High income

Middle income

Total Deposits / GDP (%)

Public Debt / GDP (%)

30

Figure 15. Size of DIS Fund Relative to Covered Deposits and Government Indebtedness

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

0 50 100 150 200 250

Size of Fund/Covered Deposits, %

Public Debt/GDP, %

31

Figure 16. Safety Net Index, 2013 1/

Notes: The safety net index is a principal components index of DI design and other safety net features that is increasing in the generosity of the safety net.

1/ Countries with safety net index (SNI) values between -1 and +1 are excluded from the chart.

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

Argentina

Iceland

Ecuador

Bahrain

Bangladesh

Nicaragua

Libya

Liechtenstein

Gibraltar

Lebanon

Tanzania

Oman

Morocco

Bahamas, The

Japan

Colombia

Nepal

El Salvador

Sudan

Philippines

Norway

Malaysia

Brazil

Uganda

Chile

United Kingdom

Australia

Indonesia

Singapore

Romania

France

Latvia

Portugal

Jordan

Hungary

Hong Kong

Mongolia

Kenya

Belgium

Belarus

Thailand

Slovak Republic

Austria

Germany

Denmark

Turkmenistan

Ireland

United States

Uzbekistan

32

Table 1. Explicit Deposit Insurance Schemes Around the World, end-2013

As of 2013

Cameroon (2011) 7/ Angola Ghana Rwanda

Central African Rep. (2011) 7/ Benin Guinea São Tomé and Príncipe

Chad (2011) 7/ Botswana Guinea-Bissau Senegal

Congo, Rep. (2011) 7/ Burkina Faso Lesotho Seychelles

Equatorial Guinea (2011) 7/ Burundi Liberia Sierra Leone

Gabon (2011) 7/ Cape Verde Madagascar Somalia

Kenya Comoros Malawi South Africa

Nigeria Congo, Democratic Rep. Mali Swaziland

Tanzania Côte d'Ivoire Mauritius Togo

Uganda Eritrea Mozambique Zambia

Zimbabwe Ethiopia Namibia

Gambia, The Niger

Australia (2008) 1/ Korea, Rep. of Philippines Bhutan New Zealand 4/ Tuvalu

Bangladesh Laos Singapore (2006) 1/ Cambodia Palau Vanuatu

Brunei Darussalam (2011) 1/ Malaysia (2005) /1 Sri Lanka (2012) 8/ China Papua New Guinea

Hong Kong (2004) 1/ Marshall Islands 2/ Thailand (2008) 1/ Fiji Samoa

India Micronesia 2/ Vietnam Kiribati Solomon Islands

Indonesia (2004) 1/ Mongolia (2013) 1/ Maldives Timor-Leste

Japan Nepal (2010) 1/ Myanmar 3/ Tonga

Albania Greece Norway Israel

Austria Hungary Poland San Marino

Belarus Iceland Portugal

Belgium Ireland Romania

Bosnia & Herzegovina Italy Russian Federation

Bulgaria Kosovo (2012) 1/ Serbia

Croatia Latvia Slovak Republic

Cyprus Liechtenstein Slovenia

Czech Republic Lithuania Spain

Denmark Luxembourg Sweden

Estonia Macedonia, FYR Switzerland

Finland Malta Turkey

France Moldova (2004) 1/ Ukraine

Germany Montenegro (2010) United Kingdom

Gibraltar Netherlands

Afghanistan (2009) Kazakhstan Oman Djibouti Pakistan

Algeria Kyrgyz Republic (2008) 1/ Sudan Egypt Qatar

Armenia (2005) 1/ Lebanon Tajikistan (2004) 1/ Georgia Saudi Arabia

Azerbaijan (2007) 1/ Libya (2010) Turkmenistan Iran Syrian Arab Republic

Bahrain Mauritania (2008) 1/ 10/ Uzbekistan Iraq Tunisia

Jordan Morocco Yemen (2008) 1/ Kuwait United Arab Emirates

Argentina Ecuador Paraguay Antigua and Barbuda Guyana

Bahamas, The El Salvador Peru Belize Haiti

Barbados (2007) 1/ Guatemala Trinidad and Tobago Bolivia 5/ Panama

Brazil Honduras United States Costa Rica St. Kitts and Nevis

Canada Jamaica Uruguay Dominica St. Lucia

Chile Mexico Venezuela Dominican Republic 6/ St. Vincent and the Grenadines

Colombia Nicaragua Grenada Suriname

Western

Hemisphere

Africa

Countries with Explicit Deposit Insurance Schemes

Countries Without Explicit Deposit Insurance Schemes

Europe

Asia-Pacific 9/

Middle East and

Central Asia

33

Notes:

1/ Explicit deposit insurance scheme introduced since previous release of the deposit insurance database in 2004.

2/ Covered by the deposit insurance scheme of the United States (FDIC).

3/ Insurance product tailored to small retail depositors provided to private banks by a state-run insurance company. Several large banks, including Kanbawza and Co-operative Bank, have participated as

of 2011.

4/ New Zealand introduced an opt-in retail deposit guarantee scheme in October 2008 and closed it in December 2010. Deposits held in New Zealand branches of Australian branches were covered

under the Australian deposit insurance scheme from 2008 - 2010, but current legislation will limit coverage to Australian dollar-denominated deposits only.

5/ Bolivia has a bank resolution fund with funding provided by member banks, but no explicit deposit insurance.

6/ The Dominican Republic has no deposit insurance for commercial banks, but there is a scheme (established in 1962) insuring the savings and term deposits in savings and loan associations. In the

past, the Central Bank has guaranteed deposits at Bancomercio (1996) and Baninter (2003) when these large banks failed.

7/ In 2009, Cameroon, Central African Rep., Chad, Congo (Rep), Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, which share a regional central bank, established the Fonds de Garantie des Depots en Afrique Centrale

(FOGADAC), a regional deposit insurance scheme that became operational in 2011.

8/ The Sri Lanka Deposit Insurance Scheme (SLDIS) became effective on January 1, 2012, although member banks and finance companies participating in this scheme already started contributing on a

mandatory basis starting on October 1, 2010.

9/ Taiwan (ROC) has deposit insurance but is not an IMF member.

10/ A deposit guarantee fund (Fonds de Garantie des Dépôts) exists on the basis of the deposit guarantee law of 2008 but has not become operational yet as of end-2013.

Sources: World Bank Survey, IADI, Laeven and Valencia (2012), FSB (2010, 2012), IMF staff reports, and national deposit insurance agencies.

34

Table 2. Coverage of Explicit Deposit Insurance Schemes Around the World, end-2013

Country

2003 2010 2013 2003 2010 2013 2003 2010 2013 2003 2010 2013

Afghanistan

n.a, AF100,000 AF100,000

n.a. 2222 1767 n.a. 2222 1767 n.a. 412 260

Albania

100% of first LEK350,000; 85% of

next LEK411,765 (up to maximum of

LEK700,000)

LEK2,500,000 LEK2,500,000 5796 24032 24498 5796 24032 24498 319 586 531

Algeria

DIN600,000

DIN600,000 DIN600,000 7752 8066 7678 7752 8066 7678 364 180 141

Argentina

ARG30,000 ARG120,000 ARG120,000 10345 30769 18209 10345 30769 18209 303 336 155

Armenia n.a. AMD4,000,000 AMD4,000,000 n.a. 10705 9877 n.a. 10705 9877 n.a. 377 308

Australia

n.a.

AUD1,000,000 AUD250,000 n.a. 917431 221625 n.a. UNLIMITED 1/ 221625 n.a. 1628 342

Austria EUR20,000 7/ EUR100,000 EUR100,000 22727 133333 137830 22727 133333 137830 73 296 282

Azerbaijan, Rep. of n.a. AZN30,000 AZN30,000 n.a. 37500 38217 n.a. 37500 38217 n.a. 638 484

Bahamas, The BAH50,000 BAH50,000 BAH50,000 50000 50000 50000 50000 50000 50000 223 218 213

Bahrain

75% of first BHD20,000 (up to

maximum of BHD15,000)

75% of first BHD20,000 (up to maximum

of BHD15,000)

75% of first BHD20,000 (up to maximum

of BHD15,000)

39474 39474 39894 39474 39474 39894 262 170 145

Bangladesh

TAK60,000 TAK100,000 TAK100,000 1032 1425 1287 1032 1425 1287 271 203 142

Barbados n.a. USD12,500 USD12,500 n.a. 12500 12500 n.a. 12500 12500 n.a. 78 81

Belarus USD1,000 EUR5,000 EUR5,000 1000 6667 6892 1000 UNLIMITED 8/ UNLIMITED 55 115 91

Belgium EUR20,000 EUR100,000 EUR100,000 22727 133333 137830 22727 133333 137830 76 306 304

Bosnia-Herzegovina BAM5,000 BAM35,000 BAM35,000 2890 23649 24700 2890 23649 24700 131 547 537

Brazil BRR20,000 BRR70,000 BRR250,000 6536 39773 106211 6536 39773 106211 215 359 939

Brunei Darussalam n.a. BND50,000 BND50,000 n.a. 36765 39392 n.a. 36765 39392 n.a. 115 99

Bulgaria BGN15,000 BGN196,000 BGN196,000 8671 132432 137063 8671 132432 137063 328 2078 1870

Cameroon n.a. n.a. XAF5,000,000 n.a. n.a. 10480 n.a. n.a. 10480 n.a. n.a. 1031

Canada CAD60,000 CAD100,000 CAD100,000 42857 97087 93985 42857 97087 93985 157 8799 7394