/*6&23*480'024)",04"/*6&23*480'024)",04"

$)0-"2-80..0/3$)0-"2-80..0/3

$$51"4*0/"-)&2"18"1340/&3 &1"24.&/40'$$51"4*0/"-)&2"18

)&4*-*480'."240.&&$)/0-0(87*4)*/$$51"4*0/"-)&4*-*480'."240.&&$)/0-0(87*4)*/$$51"4*0/"-

)&2"182"$4*$&)&2"182"$4*$&

8-*& "-4)&23

&33*&!*..&2

07%0&3"$$&33404)*3702,#&/&:4805&453,/07

0--074)*3"/%"%%*4*0/"-702,3"4)4413$0..0/35/%&%504(2"%

&$0..&/%&%*4"4*0/&$0..&/%&%*4"4*0/

"-4)&238-*&"/%!*..&2&33*&)&4*-*480'."240.&&$)/0-0(87*4)*/$$51"4*0/"-)&2"18

2"$4*$&

$$51"4*0/"-)&2"18"1340/&3

)4413$0..0/35/%&%504(2"%

)*3$)0-"2-820+&$4*3#205()440805'02'2&&"/%01&/"$$&33#84)&&1"24.&/40'$$51"4*0/"-)&2"18"4

$)0-"2-80..0/34)"3#&&/"$$&14&%'02*/$-53*0/*/$$51"4*0/"-)&2"18"1340/&3#8"/"54)02*9&%

"%.*/*342"4020'$)0-"2-80..0/302.02&*/'02."4*0/1-&"3&$0/4"$45/%$0..0/3-*#2"285/%&%5

The Utility of Smart Home Technology within Occupational Therapy Practice

by

Kylie Walthers, MOTS and Jessie Zimmer, MOTS

Advisor: Cherie Graves, PhD, OTR/L

Contributing: Marilyn G. Klug, PhD

An Independent Study

Submitted to the Occupational Therapy Department

of the

University of North Dakota

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of

Master’s of Occupational Therapy

Grand Forks, North Dakota

May, 2020

ii

Approval Page

This Independent Study paper, submitted by Kylie Walthers, MOTS and Jessie Zimmer,

MOTS in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Master of Occupational

Therapy from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Faculty Advisor

under whom the work has been done and is hereby approved.

_________________________

Faculty Advisor

April 16, 2020

Date

iii

PERMISSION

Title: The Utility of Smart Home Technology within Occupational Therapy

Practice

Department: Occupational Therapy

Degree: Master’s of Occupational Therapy

In presenting this Independent Study in partial fulfillment of the requirements for

a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, we agree that the Department of

Occupational Therapy shall make it freely available for inspection. We further agree that

permission for extensive copying for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor

who supervised our work or, in her absence, by the Chairperson of the Department. It is

understood that any copying or publication or other use of this Independent Study or part

thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without our written permission. It is also

understood that due recognition shall be given to us and the University of North Dakota

in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in our Independent Study

Report.

__________________________

Signature

_________________________

Date

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES…………………..................................................................................v

LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………...vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..............................................................................................viii

ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...ix

CHAPTER

I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………1

II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE…………………………………………………..5

III. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY.....................................................................31

IV. PRESENTATION & ANALYSIS OF DATA ...............................................45

V. DISCUSSION ..................................................................................................73

REFERENCES .................................................................................................................86

APPENDICES ..................................................................................................................92

Appendix A................................................................................................92

Appendix B................................................................................................97

Appendix C................................................................................................99

v

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE 1: Demographics ……………………………………………………………….48

TABLE 2: Amount of Education Received on SHT …………………..……….……….. 52

TABLE 3: Time Spent Researching SHT ………………………..…………….……….. 54

TABLE 4: Incorporation of SHT into Practice ……………...…………….….……….. 55

TABLE 5: Comfort and Perceived Effectiveness with Using SHT ……..……..……….. 57

TABLE 6: Supports for Using SHT ……………...…………………………………….. 58

TABLE 7: Level of Interest in Using SHT ………...……….………...………..……….. 59

TABLE 8: Perceived Knowledge of SHT …………………………………......……….. 60

TABLE 9: Time and Access to SHT ………………………………....………..……….. 61

TABLE 10: Employer Funding for SHT and Access to Other Funding Sources for

SHT……………………………………………………………………………………... 63

TABLE 11: Correlation between Availability and Degree of Support ………….…….. 65

TABLE 12: Correlation between Availability and Level of Interest ………….……….. 65

TABLE 13: Correlation between Availability and Funding ……………….....……….. 66

TABLE 14: Correlation between Degree of Support and Level of Interest ……..…….. 66

TABLE 15: Correlation between Degree of Support and Funding …………..……….. 67

TABLE 16: Correlation between Degree of Support and Use ……...….……..……….. 67

TABLE 17: Correlation between Sources of Support and Use ……...………..……….. 68

TABLE 18: Correlation between Education and Interest ……....………..……...…….. 68

TABLE 19: Correlation between Interest and Perceived Effectiveness…..…..……….. 69

TABLE 20: Correlation between Interest and Use …………….......................……….. 69

TABLE 21: Correlation between Perceived Knowledge and Comfort …………..…….. 70

TABLE 22: Correlation between Perceived Knowledge and Perceived Effectiveness… 70

vi

TABLE 23: Correlation between Perceived Knowledge and Use ………….………….. 71

TABLE 24: Correlation between Comfort and Perceived Effectiveness …………..….. 71

TABLE 25: Correlation between Funding and Use ………...………………...……….. 72

vii

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE 1: Where SHT Education was Obtained ……………..…………….……..….. 53

FIGURE 2: Hours per Week Spent Researching SHT ……………….……….….…….. 55

FIGURE 3: Percentage that Incorporate SHT into Practice ………..………..……….. 56

FIGURE 4: Perceived Effectiveness & Comfort Using SHT ……………...………..….. 57

FIGURE 5: Supports for Using SHT ……………...……….………...………..……….. 58

FIGURE 6: Interest in SHT ……………………………………………….......……….. 59

FIGURE 7: Perceived Knowledge of SHT ………………………......………..……….. 60

FIGURE 8: Availability to Implement SHT ……………...……..…...………..……….. 62

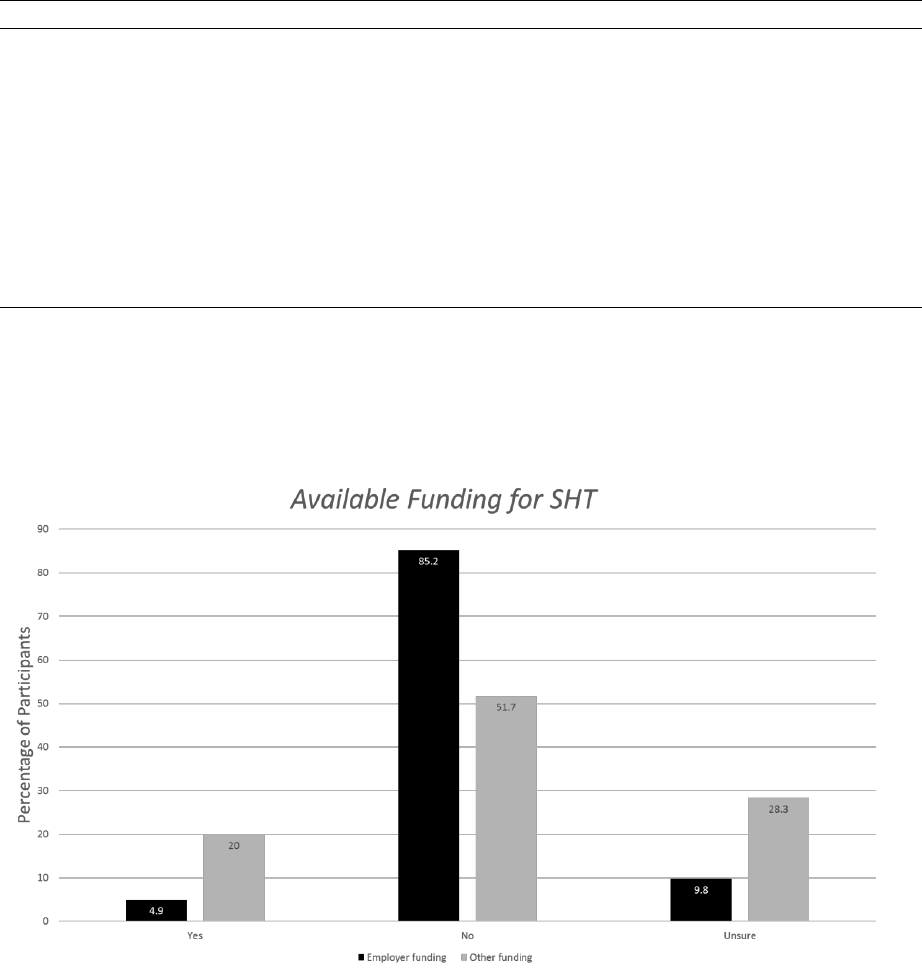

FIGURE 9: Available Funding for SHT ……………...………..…...……………...….. 63

viii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our deepest gratitude and appreciation to our advisor,

Dr. Cherie Graves, for her guidance, support, endless meetings (phone and us stopping by

unannounced to her office) and feedback throughout this process and completion of this

Independent Study. We would also like to thank Dr. Marilyn Klug for her assistance and

expertise in the research process. Lastly, we would like to thank our friends and family

for all their love, support, patience, and understanding throughout the duration of this

process as we could not have completed it without you all.

Kylie and Jessie

ix

ABSTRACT

Title: The Utility of Smart Home Technology within Occupational Therapy Practice

Kylie Walthers, MOTS, Jessie Zimmer, MOTS, & Cherie Graves, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA.

Department of Occupational Therapy, University of North Dakota School of

Medicine and Health Sciences, 1301 N Columbia Rd, Stop 9037, Grand Forks,

ND, 58202-9037

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to explore occupational therapist practitioners’

(OTPs) utility of smart home technology (SHT) in their practice, as well as to inquire into

the facilitators and barriers of utilization of smart home technology within the practice of

occupational therapy.

Methodology: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the

University of North Dakota (UND) in Grand Forks, ND. A quantitative, descriptive

research design utilizing survey methodology was used. Recruitment was conducted

through purposive and convenience sampling. A 30-question Qualtrics survey was

distributed to participants via social media and internet pages (OT4OT; AT4OT;

CommunOT; and UND OT Alumni page). There was minimal inclusion criteria for the

population recruited. Quantitative data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for

Social Sciences, version 26. The framework guiding this quantitative research study was

the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2) (Venkatesh,

Thong, & Xu, 2012).

Results: A total of 75 surveys were returned, both by occupational therapists (OTs) and

occupational therapy assistants (OTAs). Most of the respondents were female (91%,

n=68) and were OTs (85%, n=64). Most of the respondents practice in the United States

(61%, n=46) working in home health (33%, n=25) and outpatient settings (31%, n=23).

Overall, the respondents reported that they do not currently use SHT in practice (63%,

n=47), that they are somewhat interested in using SHT (34%, n=21), and that most of

their education on SHT is obtained from independent research or study (25%, n=16).

When considering availability, respondents stated that they do not have time (57%, n=43)

or access (36%, n=22) to incorporate SHT. Lastly, available funding and support are

limited as well, with respondents stating they do not have employer (85%, n=52) or other

funding (52%, n=31). Most non-financial support comes from co-workers (n=16) and

family (n=8). Spearman rho correlations were conducted, finding multiple strong

correlations between: the degree of support and who is providing the support (co-

workers, family, etc.); level of comfort with utilizing SHT and effectiveness when

utilizing SHT; types of funding sources available (private, insurance, etc.) and received

amount of funding currently; and received funding and use.

Conclusion: Occupational therapy practitioners are more likely to use SHT in practice if

they have support in a variety of forms, but especially from their co-workers. Interest is

also linked to increased support, increased access to funding, and increased availability.

However, interest was not the driving force for being effective when using SHT. It was

found that comfort with SHT was the driving force for practitioners to perceive they were

effective when using it as an intervention. The most substantial barriers to using SHT that

were identified include: lack of funding sources, lack of education, and lack of

x

availability to the devices. These factors do not need to remain barriers and in fact can

and should become supports to using SHT. Smart home technology should be used in

care and when a practitioner takes a moment to develop interest in the topic, thus

developing a better understanding and knowledge base, they will likely have an increase

in comfort and therefore, perceived effectiveness when using technologies as

interventions. All of these factors assist clients in the long run.

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Rationale

Smart home technology (SHT) is becoming a popular means to assist people in

their daily lives. Various populations may benefit from the use of SHT including

individuals living with disabilities, individuals that wish to age in place, as well as the

general population. Smart home technology can arguably fall into the category of

assistive technologies (Cook & Polgar, 2014) and therefore can be used by occupational

therapy practitioners (OTPs) for therapeutic interventions. There have been calls to action

for OTPs to be using SHT (Waite, 2015) and studies that look at the feasibility of OTPs

using SHT to assist client’s to live more independent and meaningful lives (Giger &

Markward, 2011; Liu, 2018). Despite this, little research has been done investigating

OTPs actual use of SHT and the barriers and supports that OTPs experience influencing

their use or non-use of SHT.

Theoretical Framework

The framework that was used to guide this quantitative research study was the

Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2) (Venkatesh, Thong,

& Xu, 2012). The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 is a theory

developed by information systems researchers (Venkatesh et al., 2012). This is an

expansion of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Liu et

al., 2015; Venkatesh et al., 2012). The UTAUT2 considers individual characteristics (age,

2

gender, and experience) and constructs (performance expectancy, effort expectancy,

social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic motivation, price value, and habit) when

assessing and observing the influence on the consumer’s behavioral intention and

behavioral use of technology (Venkatesh et al., 2012). This model has been used in the

past to study the acceptance of new technologies by rehabilitation therapists (Liu et al.,

2015). The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 is a well-suited

theory to utilize when examining the relationship of occupational therapy practitioners

and their integration of SHT into practice due to its extensive nature as it looks into

individual characteristics and constructs, and how these may influence the utilization of

technology in occupational therapy practice. The model was chosen when considering

previous literature that was available on the use and non-use of technology and was

determined by the researchers to be a good fit to guide the research process.

Statement of the Problem

Occupational therapists have the opportunity to assist individuals to live

independent and high quality lives through the use of SHT. To further explore the use of

smart home technology in occupational therapy practice, the researchers designed this

quantitative study. The overarching research question is, what is the utility of smart

home technology within occupational therapy practice? The researchers developed two

additional sub-questions:

• What relationships exist (if any) between factors identified and

reported with use of SHT?

• What relationships exist (if any) between factors identified and

reported with perceived effectiveness with SHT?

3

Assumption

Based on the literature review and personal experience, the researchers assumed

that there would be minimal use of SHT by practitioners. In addition, the researchers

assumed that there would be several factors that have influenced the use or non-use of

SHT by OTPs. Factors that were thought to influence use include but are not limited to

availability, funding, and support.

Scope and Delimitation

This study was granted approval by the University of North Dakota’s Institutional

Review Board. The data for this study was gathered via an online survey. Participants

were recruited via social media and online discussion boards. Inclusion criteria for

participants required the individuals to be occupational therapists or occupational therapy

assistants. The survey tool was open for five weeks before being closed for data

analysis.

Importance of the Study

Little research has been done looking at the actual use of SHT by occupational

therapy practitioners and potential facilitators and barriers of using this technology. This

study shows the importance of occupational therapy in this new realm of technologies. In

addition, this study provides objective information regarding why practitioners may not

be using SHT in practice. This information is relevant and important to occupational

therapy practitioners, occupational therapy programs, assistive technology companies,

SHT companies, and consumers of occupational therapy services.

Definition of Terms

The following terminology is used throughout the remainder of this scholarly project.

4

• Assistive technology: “A broad range of devices, services, strategies, and

practices that are conceived and applied to ameliorate the problems faced by

individuals who have disabilities” (Cook & Polgar, 2014, p.460).

• Occupational therapy practitioners: For the purposes of this study, occupational

therapy practitioners (OTPs) are defined as occupational therapists and

occupational therapy assistants.

• Smart home technology: “Any electronic device (including but not limited to

actuators, sensors, computer processors/software, and supporting structures) that

create an integrated system capable of monitoring and supporting individuals in

real-time” (Davenport, Mann, & Lutz, 2012, p. 169).

5

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Technology has become a part of our lives more now than ever before. It has

become embedded within the way people live and work, and even within people’s bodies

and what they choose to wear (Liu, 2018). There is a variety of different forms of

technology, ranging from robotics, the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence

(AI), 3-D printing, virtual reality, autonomous vehicles, smart home technology, and

much more (Liu, 2018). With the increase of technology in everyday life comes the

increase of opportunities that individuals can utilize technology in assisting with

healthcare. These technologies can be used to assist individuals with and without

disabilities in a variety of ways. According to Liu (2018), healthcare professionals,

including occupational and physical therapy practitioners, were initially slow to use

technology in the rehabilitation process. However, throughout the years, healthcare

practitioners have increased their overall use of technology when providing services for

clients.

When faced with the idea of implementing technologies into healthcare, many

individuals, practitioners and clients alike, quickly revert to the idea of assistive

technologies. Assistive technology encompasses devices, services, and systems that assist

individuals living with a disability to perform designated tasks throughout their everyday

lives (Cook & Polgar, 2014). Assistive technology falls into two categories, high assistive

technology and low assistive technology. High technology involves more complex

6

devices, such as augmentative and alternative communication devices, whereas low

assistive technology devices involve less moving parts, such as Velcro straps or built up

utensil handles.

A more recent form of technology, smart home technology (SHT), has added

greater opportunities for occupational therapy and other professions. While the promise

of smart home technology in rehabilitation fields is great, the complexity of use has

contributed to its slow rise in popularity and slower rate of implementation in practice. In

Sweden, researchers studied the SmartBo project, which utilizes solutions for elderly

with mobility and/or cognitive impairments. Solutions involve utilizing devices and

sensors that control the lighting, windows, doors, locks, water outlets, electrical power

and stove. In addition, visual and tactile signaling devices, Braille displays for the

visually impaired, and speech synthesizers were incorporated (Demiris et al., 2004).

These examples of technology demonstrate how technology can be utilized by healthcare

practitioners to enable a variety of clients to improve their overall functioning and well-

being in the home environment.

These technological advances have brought about opportunities that occupational

therapists can utilize to support client occupational performance and participation. To

have an impact in the realm of advancing technologies and in the future trends of client

care, the occupational therapy profession must understand the technology available and

how it can be used to support client occupational performance and participation. The

scope of technology is extensive and can include many different devices, terminologies,

and definitions. The focus of this inquiry is on the use of smart home technology in

occupational therapy practice.

7

What is Smart Technology

There are many definitions of smart technology. Davenport, Mann, and Lutz

(2012) define smart technology as “any electronic device (including but not limited to

actuators, sensors, computer processors/software, and supporting structures) that create

an integrated system capable of monitoring and supporting individuals in real-time” (p.

169). According to Dermody and Fritz (2019), smart home is a general term used in two

ways: “when referring to consumer-driven in-home smart products (e.g., Amazon’s®

Alexa), or when referring to technology that assists with in-home delivery of healthcare

aging-in-place technologies such as Life Alert®, AngelSense®, GPS Smart Sole®” (p.

2). Data collected from smart home technology can consist of many things, such as

dates, timestamps, sensor labels (e.g., bedroom, a door), sensor states (e.g., ON/OFF),

and activity labels (e.g., sleeping, grooming) (Dermody & Fritz, 2019). Within this paper,

smart technology and smart home technology will be used interchangeably.

Designing a Smart Home and Available Technology

Smart home technology uses two different approaches to provide services;

distributing direct sensing and infrastructure-mediated sensing (Chung, Demiris, &

Thompson, 2016). Distributed direct sensing uses installed sensors in the home for

indicators, whereas infrastructure-mediated sensing uses sensors that are already in place,

such as an air conditioner or electricity use, to sense activity levels within the home

(Chung et al., 2016). These approaches need to be taken into consideration when

designing a smart home system. A smart home system uses multiple smart technologies

within a home’s IoT system to assist an individual in their desired areas of services

indicated by the type of technologies introduced into the home.

8

To begin the design process of a smart home system, the home’s Wi-Fi needs to

have the capability to support the technology. More than one router may be needed

depending on the size of the home and the technologies being used. A mesh Wi-Fi system

uses multiple devices to provide Wi-Fi in all areas of the home, including near the

home’s parameters to allow Wi-Fi to work outside the home (McKeough, 2019). Once

the initial stages of setting up the system(s) have been addressed, there are several

options to control the smart home system. Individual devices can be controlled by

individual apps from a smartphone. Many companies have apps that allow controls to be

used across the company’s specific devices. A virtual assistant is also able to control

basic features, such as turning the lights on and off or controlling a thermostat

(McKeough, 2019). For a more comprehensive control system, a smart hub or bridge is

used. A hub and bridge offer the same services, which is to connect all smart

technologies in one place (Apple Inc., 2019; McKeough, 2019; Smart Home, 2019). This

allows for complete control from a single app. With a hub or bridge, an individual is able

to set up specific controls that can occur daily, such as low lighting when people arrive at

home in the evening or setting the sprinkler system to turn on at a certain time. In

essence, a hub or bridge allows an individual to easily access all of the abilities and

services technology has to offer from a single app. Hubs and bridges are able to connect

with voice assistants as well (Apple Inc., 2019; McKeough, 2019; Smart Home, 2019).

Voice assistants are likely one of the most popular smart devices that are currently

available. There are several prominent companies that make voice assistants that also

make other smart technologies, allowing for ease of interconnection between the

technologies. Voice assistants are able to play music, answer questions, and give

9

reminders, among other things (McKeough, 2019). Smart speakers can connect with a

central voice assistant to provide the services throughout the home (McKeough, 2019).

Smart home technology is able to address almost all aspects of the modern home,

from security, to lighting, to water leaks. Security systems use door sensors, door locks,

motion sensors, and video monitoring to notify an individual of any changes in the

environment as well as allow access to the home (Apple Inc., 2019; McKeough, 2019;

Smart Home, 2019). These devices can be used throughout the home, as well as outside.

For example, a smart doorbell can be used to monitor who enters the home or who is near

the front of the house (McKeough, 2019). Smart sprinkler systems are also available,

allowing a person to turn on the sprinklers at home from anywhere in the world (Apple

Inc., 2019; McKeough, 2019; Smart Home, 2019). Smart garage doors are a common

feature in smart homes as well (McKeough, 2019).

Inside the home there are a variety of technologies that can sense the air, turn on

the lights, and monitor for potential issues (Apple Inc., 2019; McKeough, 2019; Smart

Home, 2019). Smart lighting can be achieved by installing a bulb or a dimmer

(McKeough, 2019). Battery powered window shades are able to work with shades that

are already existing in the home (McKeough, 2019). Smart outlets are also available to

assist in turning on or off appliances that are plugged in, even those that are not

considered to be a smart device (Apple Inc., 2019; McKeough, 2019; Smart Home,

2019). Smart TVs connect to an online network to allow web access and network

channels without the need for cable or satellite. In the area of home safety and comfort,

the following smart devices are available: fans, thermostats, air purifiers, humidifiers,

smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, water leak detection, kitchen appliances, washing

10

machines, access control, and additional indoor sensors (Apple Inc., 2019; McKeough,

2019; Smart Home, 2019). For many of these devices, individuals, including

professionals and clients alike, forget that the devices are considered SHT.

Using Smart Home Technology to Enhance Quality of Life

Smart home technology is used globally by individuals with and without

disabilities. It is considered assistive technology if it is used specifically to assist an

individual with a disability to complete everyday tasks. For example, SHT can be used to

assist an individual who has a cognitive impairment to remember to take their

medications in the morning. A SHT system can be developed to enable an older adult to

age in place safely and negate the necessity of facility placement.

Currently, there are several companies that provide services targeting older adults

and their loved ones who wish to age in place. Aging in place services are made possible

by use of a variety of sensors, video monitoring, artificial intelligence, two way

communication systems, and voices assistants (Orlov, 2019). These technologies are able

to: detect falls, provide reminders, monitor for safety and security, provide

communication with healthcare professionals, call emergency services, communicate

with family, allow for family to check in with their loved ones, and even monitor

cognition (Orlov, 2019). These services may also be an option for individuals of any age,

with disabilities, to live more independent lives.

In addition to using SHT to age in place at home, smart technology is being made

available to use in facilities such as long term care and assisted living (WytCote

Technologies, 2019). Various sensors, wearable technology, and video monitoring can

11

detect movements and actions of residents and staff, fall detection, and facility

operations, such as moisture and water temperatures (WytCote Technologies, 2019).

This technology is able to provide services and support in many parts of home

life. Smart devices are able to assist individuals with all ability levels and needs, and can

provide huge advancements in care when implemented with rehabilitation services. Smart

home technology is likely to be more interconnected and an accepted part of society as it

becomes more advanced and popular, essentially in all aspects of our daily lives and

environments. Occupational therapy practitioners must follow the trend of technology

and the opportunities it can provide, such as promote client well-being and connect

clients to individuals or systems when needed most. There is a considerable amount of

literature that examines use and non-use of assistive technology devices, among users and

practitioners, but literature is lacking specifically related to use and non-use of smart

home technology. There is a need for further study on SHT and the factors influencing

the implementation of such devices among practitioners into client’s everyday lives.

The Occupational Therapy Process: Incorporating Technology

Technologies are influencing our future and will pose new ways for occupational

therapy practitioners to assess and provide intervention services to clients. With the

continued development and increased use of technology devices, it is likely that the role

of occupational therapy and other interdisciplinary team members in relation to

technology will also continue to grow (Verdonck, McCormack, & Chard, 2011).

Occupational therapy practitioners have many different ways they can incorporate

technologies to help clients, such as critically analyzing the details and skills needed to

use technology, choosing and implementing the appropriate technologies for use outside

12

of a clinical setting (ex. work, home), or being a part of a research team that researches

updated technologies (Cook & Polgar, 2014).

When examining an OTs role as part of a research team, Alex Mihailidis - the

Barbara G. Stymiest Research Chair in the rehabilitation technology center at the

University of Toronto and Toronto Rehab Institute - conducts research on pervasive

computing and intelligent systems used in healthcare. Along with one of his team

members, who is an occupational therapist, Alex states that “their primary role is making

sure that we understand the human roles for the technology, looking at the functionality

based on the needs and the skills that the particular client has - the OT really has that

lens” (Waite, 2015).

Ultimately, the goal of occupational therapy when working with clients who are

considering the implementation of home modifications and SHT is to help client’s be as

safe and independent as possible, allowing the client to engage in the activities and tasks

that are meaningful to them (Waite, 2015). The intent for many occupational therapists

when considering the implementation of technology is to meet individual’s needs and

desires to remain independent in their home environment, leading to the use of smart

home technology. With the increase in utilization of smart home technology in

healthcare, it is important to consider what the needs of the client are, which is obtained

through the occupational profile and occupational therapy evaluation, and the

expectations of the individual in regards to technology usage (Cook & Polgar, 2014). If

occupational therapy practitioners fail to take the needs of the client into consideration

while implementing the devices or systems, by only considering the direct features of the

13

technology, they risk adopting approaches that are associated with medical, bottom-up

approaches, and disempowering the client (Cook & Polgar, 2014).

There are many examples in the literature that support the occupational therapy

profession in helping clients who are using smart technology. Occupational therapy

practitioners have the ability to provide interventions in the area of smart technology for a

variety of clients in a wide array of contexts. The following are examples from the

literature of utilizing smart technology for interventions. Occupational therapists can use

compensatory strategies with censored eyewear for left inattention poststroke and use of

interactive games with older adults to understand the functions within a home or

community (Giger & Markward, 2011). There are also devices that assess levels of

engagement in clients who are nonverbal or unable to complete traditional assessments

that measure engagement and alerts on mobile devices for community citizens when a

person, such as an older adult with dementia, goes missing from or within a geographical

location (Giger & Markward, 2011). In regards to smart home technology and

occupational therapy, occupational therapists design smart homes to allow clients to

remain in their natural environments by utilizing universal design principles and

implement smart home monitors to assess client’s abilities to complete activities of daily

living (Giger & Markward, 2011). In addition, occupational therapists can recommend

SHT in the homes of individuals with serious mental illness or cognitive impairments to

assist caregivers in monitoring for safety and to assist these individuals in leading more

independent lives by providing reminders, safety alerts, and monitoring (Giger &

Markward, 2011).

14

With the increasing development and utilization of smart home technology in

healthcare, users currently experience challenges such as continuously developing and

maintaining their knowledge of options, implementation, and maintenance of this type of

technology (Verdonck et al., 2011). In addition, occupational therapists experience

challenges with maintaining a client-centered focus, limiting abandonment of the devices,

and keeping up to date with the emerging products (Verdonck et al., 2011). Occupational

therapists must be aware of and consider the way technologies have changed how basic

and instrumental activities of daily living are performed, making some OT assessments

obsolete (Liu, 2018). Occupational therapists delivering occupation-focused and person-

centered services while utilizing smart home technologies need to know what is available

and how to access and use the technologies with clients. Some common barriers, or

challenges, with implementing technology into OT care will be addressed within the next

sections.

Factors Influencing the Implementation of Smart Home Technology

Literature supports the use of SHT for improving the lives of clients (Davenport,

Mann, & Lutz, 2012), recognizing the impact technology can play in improving an

individual’s quality of life. With that said, the researchers of this study assert that

occupational therapist’s experience factors that influence the implementation of smart

home technology. A small-scale study conducted in Ireland explored occupational

therapist’s responses to a short, five-question survey related to their views on utilizing

technology, perceived competence in this area, and an understanding of whose role it is to

assess for and prescribe such technologies (Verdonck et al., 2011). The researchers found

benefits that occupational therapist’s identified when using advanced technologies in

15

client care. These benefits include improved client independence, increased client self-

esteem, increased participation in occupations, improved personal relationships,

increased safety, decreased level of assistance needed, and overall the technology saved

money for the client and the company (Verdonck et al., 2011).

Although there are benefits to utilizing SHT, there are identified factors that

influence the implementation of technology. Hoogerwerf et al. (2002) assert that high

technologies, such as SHT, is described by practitioners as inconsistent, uncoordinated,

fragmented, and difficult to access. Although Hoogerwerf et al. (2002) was published

almost two decades ago, the researchers assert that these descriptions by practitioners in

regards to technology likely remain similar today, even with the considerable advances in

technology. Additional factors have been identified in the literature as either supporting

or inhibiting the use of SHT. These variables include knowledge (Dicianno et al., 2019;

Hamblin, 2017; Jiancaro, Jaglal, & Mihailidis, 2017; Kumar et al., 2013; Proffitt,

Schwartz, Foreman, & Smith, 2019; Verdonck et al., 2011), personal interest (Verdonck

et al., 2011), workplace culture (Proffitt et al., 2019), and funding (Assistive Technology

Industry Association, 2019; Berridge, 2018; Dicianno et al., 2019; Hamblin, 2017;

Haymes, Storey, Maldonado, Post, & Montgomery, 2015; Verdonck et al., 2011). The

researchers assert that access and time are additional factors that support or inhibit the use

of SHT by healthcare professionals, although further research is needed to add to the

insight of how access and time affect occupational therapy practitioner’s use of SHT.

Knowledge

Knowledge is a necessary component when it comes to implementing any type of

intervention. In the case of SHT, there is conflicting literature regarding the knowledge

16

base that occupational therapy practitioners have when it comes to specialized

technologies. There is literature that supports the knowledge and skill set of occupational

therapy practitioners in the use of SHT in practice (Proffitt et al., 2019). Despite that,

additional literature suggests that occupational therapy practitioners have limited

knowledge in incorporating SHT into interventions and practice (Dicianno et al.,

2019). Proffitt et al. (2019) emphasized the importance of contributing to research and

development in disability-related technology designs. These contributions can be made

by occupational therapists. Occupational therapists have the skill set and knowledge in

the areas of research and universal design, which is a common approach that is

encouraged when engineers and designers are creating technologies. Universal design

requires the expertise of practitioners and professionals who understand all types of

disabilities and impairments, and how to represent individuals with these disabilities

when utilizing technologies for functional tasks (Proffitt et al., 2019).

Limitations of knowledge are also represented in the literature. Although there is

support for occupational therapists to be involved in disability-related technology designs

(Proffitt et al., 2019), there seems to be a lack of knowledge among other working

professionals when it comes to incorporating occupational therapists roles in technology

design. The lack of provider knowledge, whether it be about the technology or the

provision process itself, commonly arises (Dicianno et al., 2019). One barrier that

occupational therapists can encounter is a “language barrier”. Engineers and computer

scientists, as well as occupational therapists, all have their own jargon, creating

difficulties for professionals to communicate effectively about potential collaborations

when implementing technologies (Proffitt et al., 2019). Another barrier addressed in

17

current research is that consumers of the technology, such as occupational therapists and

other healthcare professionals, are not waiting for scientific approval before utilizing

these technology-based interventions (Kumar et al., 2013). This indicates a potential

misuse of technology, such as using tech when it is contraindicated for a client.

Jiancaro, Jaglal, and Mihailidis (2017) surveyed professionals within the fields of

occupational therapy, medicine, and psychology. According to the survey results, there

needs to be a larger role for clinical specialists (such as fields mentioned above) to

introduce and guide practice through models that may help frame and specify a situation

in which technological interventions would be appropriate. This can be done by

educating the clinical specialists. Participants in the survey also indicated that they would

be interested in becoming more educated in this area and could see potential value in

learning and utilizing technology-specific models (Jiancaro et al., 2017). According to

Verdonck et al. (2011), 84% of occupational therapists believed that he or she should be

able to assess for and prescribe higher technologies; however, only 34% were able to do

so. The researchers suggested that this difference may be attributed to lack of opportunity

to be involved during this aspect of care, and/or having little training and knowledge in

this area (Verdonck et al., 2011).

Personal Interest

Occupational therapy practitioners have a unique role in mainstreaming the use of

technologies into the delivery of client care. In addition, practitioners may take on the

role of supplying and maintaining the technologies, which may range from low tech to

high tech devices, including smart home technologies (Verdonck et al., 2011). In order

for an occupational therapy practitioner to build knowledge about SHT, some personal

18

interest in technology and incorporating it into practice is needed. Practitioners that are

more interested in the subject have a greater potential for incorporating the technology

into the intervention process (Verdonck et al., 2011). According to Verdonck,

McCormack, and Chard (2011), occupational therapists indicated that professionals that

provide specialized technologies are not exclusive to specialized practitioners, such as

assistive technology practitioners. Instead, the respondents indicated that they were

interested and capable of incorporating specialized technology (Verdonck et al., 2011).

Workplace Culture

When considering the occupational therapy profession, workplace culture can be

viewed as a factor that starts as far back as our educational programs. Students are shaped

by their educators, fieldwork instructors, and other OT students who have been in the

field (Proffitt et al., 2019). Proffitt, Schwartz, Foreman, and Smith (2019) suggests

students have experiences and opportunities to collaborate with other professionals that

may be implementing technologies with clients or creating designs for technologies, such

as engineering and design peers (Proffitt et al., 2019). Another recommendation provided

by Proffitt et al. (2019) is providing administrative leadership to support the role of

occupational therapy in technology research and development. There are special interest

groups among the American Occupational Therapy Association, webinars, articles, and

conferences held throughout the year on technology implementation (American

Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2019a). However, to advance the role of

occupational therapy in implementing technology, professionals must be leaders; leaders

through program directing, principal investigators, becoming a clinical administrator or

influencing an administrator in order to encourage, teach, inform, and facilitate the

19

participation of technology (Profitt et al., 2019). Additional research is needed to explore

the impact of workplace culture on the use of technology in healthcare.

Funding

Cost is an additional factor that often needs to be considered when implementing

technology with clients. According to a survey distributed to 161 occupational therapists,

the most commonly cited barrier was the intensive process of obtaining insurance

approval for the device, including the cost of the device, the availability of funding, and

the time it takes to obtain authorization and the equipment (Dicianno et al., 2019).

Another aspect reported by Hamblin (2017) is the issue with sustainability of cost and use

when using technologies with older adults. One researcher utilized smart technology at

the start of a study, providing a free service at the start of the fieldwork for one year

(Hamblin, 2017). At the end of the year, clients received a letter indicating that fees

would be introduced. This caused some clients to feel unsure whether they would

continue to use the service or not, stating funding to be the direct barrier (Hamblin,

2017). This prevented practitioners from suggesting and implementing smart home

technologies in the future with other older adults, knowing the potential for high cost

from their past experiences. A similar barrier arose with other professionals, as they came

across similar experiences during the assessment and installation of smart technology

(Hamblin, 2017). Professionals stated that their lack of knowledge on the charging policy

was a distinct barrier and some professionals indicated that they may have misadvised

their clients (Hamblin, 2017).

When private pay is not possible, insurance, both private and public, commonly

cover the cost for medical needs and medical equipment. In the United States, Medicare

20

is a commonly used public insurance that often covers medical equipment. Durable

medical equipment provides a therapeutic benefit for an individual with medical needs.

According to Medicare (2019), durable medical equipment is defined as medical

equipment that can withstand frequent use, is needed for a medical reason, is used in the

home, is typically not useful for an individual that is healthy, and lasts at least three

years. When considering SHT, some devices could fit within these parameters depending

on the individual client’s needs and context. Smart home technology may be deemed

medically necessary for some individuals and potentially be covered by insurance.

Several authors suggest that funding can be established through entities such as

Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, workers compensation,

TRICARE, state vocational rehabilitation centers, other federal and state programs, a

variety of organizations and nonprofits that offer grants, and private insurance (Assistive

Technology Industry Association, 2019; Berridge, 2018; Haymes et al., 2015).

Although the aforementioned funding sources may be available, it should be

understood that SHT is not commonly covered under medical insurance; as these smart

technologies are recently identified as an intervention in healthcare and not often deemed

medically necessary. When attempting to utilize funding sources, push back can occur

through many different sources and companies. In these instances, occupational therapists

need to utilize their advocacy skills to demonstrate a medical need for the technology and

the potential for improved quality of life for their client if the SHT is funded (J.

Loscheider, personal communication, September 6, 2019).

In Ireland and the United Kingdom, higher technologies, such as smart

technology, is funded through a variety of sources, such as charities and health,

21

employment, and educational services (Verdonck et al., 2011). Another possible funding

avenue is homeowner insurance. Coverage would not be for the upfront cost of the

device, but for protection. Many prominent home insurance companies are providing

coverage for SHT in home insurance plans (American Family Insurance, 2019; Golia,

2019; Kozak, 2018; Ochalla, 2018). The insurance industry is supporting the SHT trend

because of recognized benefits to the home (American Family Insurance, 2019; Golia,

2019; Kozak, 2018; Ochalla, 2018). For example, SHT may provide additional security

protection and more awareness of potential water damage, among other things (American

Family Insurance, 2019; Golia, 2019; Kozak, 2018; Ochalla, 2018). Some insurance

companies may even provide discounts to customers who incorporate smart technology

into their homes (American Family Insurance, 2019; Golia, 2019; Kozak, 2018; Ochalla,

2018).

Ethical Considerations

Ethics are a core part of a healthcare professional’s identity. Occupational therapy

practitioners have ethical responsibilities in relation to incorporating technology into

practice. There is a need to not only keep in mind staying up to date on technology, but

also the need to take specific client ethical concerns into consideration when considering

and implementing new technologies, such as those placed in the home environment. Due

to the dynamic nature of the profession, the evolving healthcare environment, and many

new emerging technologies that are utilized in the therapy setting and home environment,

there are potential ethical concerns in research, education, and practice that must be

considered (AOTA, 2015). According to the Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics

(AOTA, 2015), standard of conduct and principle one of beneficence states that

22

occupational therapy practitioners should “take steps (e.g., continuing education,

research, supervision, training) to ensure proficiency, use careful judgement, and weigh

the potential for harm when generally recognized standards do not exist in emerging

technology or areas of practice” (AOTA, 2015, p.3), such as implementing smart

technology.

Ethical Obligations of Occupational Therapy Practitioners

When examining the occupational therapy profession including the ethical

principles and core values, it is observed that the occupational therapy profession has a

duty to uphold when it comes to implementing technologies into practice (Proffitt et al.,

2019). The Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE)

mandates that occupational therapy practitioners must understand, demonstrate, use, and

teach the use of technology (ACOTE, 2018). Standard B.4.15 states that occupational

therapy practitioners must “demonstrate knowledge of the use of technology in practice,

which must include: electronic documentation systems, virtual environments, and

telehealth technology” (ACOTE, 2018, p. S31). Similarly, Standard B.4.11 states that

occupational therapists should “assess the need for and demonstrate the ability to design,

fabricate, apply, fit, and train in assistive technologies and devices (e.g., electronic aids to

daily living, seating and positioning systems) used to enhance occupational performance

and foster participation and well-being” (ACOTE, 2018, p. S30). Although this is specific

to assistive technologies, it relates to technologies generally, and should be considered

when designing, fabricating, applying, fittings, and training colleagues and clients with

smart technology devices.

Specific Ethical Considerations for Smart Home Technology

23

From an evolutionary perspective, the home is a natural place of comfort. Home

is a place for healing where a person can let down barriers and be themselves. Due to the

level of comfort and protection a home provides, caregivers and patients, tend to prefer

that healthcare and healing take place in the home whenever possible (Burrows, Cotle, &

Gooberman-Hill, 2018) and technologies can now assist people in their endeavor to

receive healthcare at home. The increased availability of technology in the homes has

spurred the need to further explore ethical considerations related to the implementation of

SHT and its impact in the daily life of consumers.

An ethnographic study conducted by Burrows, Cotle, and Gooberman-Hill (2018)

investigated the participant’s navigation of SHT data collection and their borders of

privacy and willingness to share their data. Smart home technology is likely to impede or

change borders of the home with data collection potentially encroaching on privacy,

blurring the lines between what is private information and public data (Burrows et al.,

2018). When data is intentionally being collected by healthcare providers, Burrows et al.

(2018) asserted that individuals may feel that they need to leave an impression when they

know that data is being collected and are likely to not act as they would in their natural

and relaxed state. Individuals participating in this study had a variety of SHT ranging

from health monitoring to energy consumption monitors to home security devices.

Participants in the study indicated that it mattered to them what specific data was shared.

For example, data about certain health practices being shared versus data about energy

consumption within the home being shared. Additionally, the personal contexts and

situations the participants were experiencing affected their willingness to be open and

share their data. Individuals living by themselves, who were also concerned about their

24

personal safety, were more willing to share their data compared to individuals living as a

couple that held the belief that they were able to keep safe because they had each other.

Regarding personal contexts and willingness to share data, there were two groups of

individuals that were more willing to be open to implementing SHT, those familiar with

SHT and individuals who had chronic health conditions that held the belief that sharing

their personal data would assist in better understanding their illness and potentially help

other people in the future (Burrows et al., 2018). Burrows et al. (2018) assert that

frameworks need to be put in place that allow individuals to control and interact with

their data. This will allow for people to maintain the boundaries, privacy, and natural

comfort of the home while sharing the necessary data to ensure they are receiving the full

benefits of their technology and assisting technology in becoming more effective.

Chung, Demiris, and Thompson (2016) completed the first integrative review of

ethics in regards to smart home technologies and older adults. Although their research

mainly applies to older adult use of SHT, it can be easily generalized in other contexts of

SHT use as well. In this study, Chung et al. (2016) reviewed 16 articles published

between 1990 and 2014, which used various research methodologies, although most were

qualitative in nature. The following ethical areas were analyzed by the authors: informed

consent, privacy, obtrusiveness, autonomy, usability, reduction in human touch, social

stigma, and equal access.

Informed consent is an important factor for many aspects when introducing SHT

(Chung et al., 2016), not only the research aspect, but also out of respect and

consideration of the client and potential caregivers, or other individuals that may be

living in the home. Informed consent includes: autonomy, doing no harm, and

25

beneficence. Informed consent is needed due to the nature of SHT collecting intimate,

and private data and information, in order to provide services to the client. Consent is

needed when considering SHT interventions, designing a SHT system, and installing

SHT. In the case of older adults, more care needs to be taken in the event of cognitive

decline or dementia. Caregivers need to be given all the information and facts of the risks

and benefits of introducing SHT systems. It is best if informed consent is obtained in all

steps of the implementation process to ensure that caregivers and clients are making the

best decisions for their circumstances.

Privacy is becoming even more important when considering the introduction of

new technologies into one’s life and home. Smart home technology is designed to collect

data and information of the client and their home in order to provide services and actions

that will assist the client in a variety of ways (Burrows et al., 2018). Due to the nature of

the SHT, there is a risk for privacy to be violated and for an individual to be taken

advantage of (Chung et al., 2016). Because of these circumstances, privacy was found to

be the core concern of older adults when considering introducing technology into their

home. Participants indicated that they did not want others to know, and potentially

criticize, their patterns or specific actions throughout the day. However, participants

indicated that they would be willing to give up some privacy if the SHT enabled them to

be more independent in their home (Chung et al., 2016).

Obtrusiveness of SHT impeding into the life and privacy of an older adult was

also identified when conducting the review (Chung et al., 2016). Elements of

obtrusiveness specifically included privacy, human interaction, usability, function,

sustainability, physical aspects, routine, and self-concept. Participants indicated that the

26

installation process was obtrusive as well as specific locations of the technology, such as

the bedroom. Additionally, noise and lighting of the technology was seen as an issue.

Participants were also against the installation of video monitoring systems into their

homes (Chung et al., 2016).

As SHT is introduced into the lives of individuals, caregivers and clients, they are

likely to become accustomed to the services the technology provides. The authors

considered participants autonomy and potential decrease in human touch for the client

after installation of SHT. In many cases, the SHT is introduced to reduce the cost of

care. Chung et al. (2016) assert that individuals, namely caregivers of older adults, may

become too dependent on technology; for example, only using remote monitoring of the

client. If this is the case, older adults may face an increase of technological interactions

and a decrease in human interactions and human touch. This may be a detriment to the

wellbeing of the older adult. Older adults indicated that they place a high value on human

touch and they did not want the possibility of technology replacing those experiences.

Participants imply being more accepting of a technology that initiates human contact

instead of reducing it. With this in mind, before the implementation of SHT, costs, all

aspects of care, and the use of SHT to assist in the care of an older adult should be

contemplated in order to maintain the best quality of life for the individual (Chung et al.,

2016).

Ethics are an important part of the practice of occupational therapy and should not

be put to the wayside when implementing SHT interventions. Ethical considerations

especially need to be made in the areas of keeping to the occupational therapy

professional standards, privacy, autonomy, usability, reliability, access, social stigma,

27

obtrusiveness, informed consent, and potential loss of human interactions (Chung et al.,

2016). The potential for blurring the lines between public and private data, as well as the

client’s personal comfort in their own home should also be considered (Burrows et al.,

2018). The client’s individual context, needs, abilities, and experiences should always be

kept in mind when looking at the ethical aspects of incorporating a SHT system.

Models: Connecting Models & Technology Together

Theoretical models, frames of reference, and frameworks are an essential part of

modern occupational therapy practice. These tools assist therapy practitioners with

thinking about multiple factors but also guides clinical reasoning and how he or she

views a client. This ensures a more client centered and holistic practice that meets the

client’s needs and wants. Though there are no specific models, frames of reference, or

frameworks targeted specifically to occupational therapy and SHT, there are existing

ones in and outside of OT practice that can guide a therapist in using SHT throughout the

OT process. The Human Activity Assistive Technology (HAAT) model has been used

since the mid-90s to aid occupational therapists and assistive technology practitioners in

matching clients with assistive technology that meets their wants and needs (Cook &

Hussey, 1995). The model emphasizes the client, in a chosen environment, and

participating in an activity. It is designed to highlight the client’s abilities and the

selection of technology to enable the needs and wants of the individual (Cook & Polgar,

2014). As a part of the human component of the HAAT model, professionals consider

client factors such as affect, cognition, motor ability, sensory ability, and experience of

using technology (Cook & Polgar, 2014). Parts of the context that are assessed include:

institutional, social, physical, and cultural (Cook & Polgar, 2014). The activity demands

28

that are considered include cognition, manipulation, and communication (Cook & Polgar,

2014). The HAAT model can be used by OTs to assess and recommend SHT that fits the

needs, wants, and goals of the client. This model is suited for this because of the

emphasis placed on the client and the activity. The client’s abilities are extensively

assessed as well as the context and activity that needs to be addressed. This directly

correlates with a smart home system as the systems are customizable to each individual,

perhaps even more individualized than the typically thought of assistive technology.

Another model, or design system, used by occupational therapists is universal

design. The goal of universal design is to meet the needs of the broadest population. It is

associated with lower cost overall and requires professionals to utilize their expertise in

understanding all types of impairments and how they present across all functional tasks

(Liu, 2018; Proffitt et al., 2019). Universal design should be at the forefront of the mind

when constructing a smart home for a client. Many spaces that utilize SHT are

constructed using universal design principles such as using SHT to track or assist

occupants in precise, non-intrusive ways (Liu, 2018).

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2), is a

theory developed by information systems researchers (Liu et al., 2015; Venkatesh,

Thong, & Xu, 2012). This is an expansion of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use

of Technology (UTAUT) (Liu et al., 2015; Venkatesh et al., 2012). The UTAUT2 takes

individual characteristics (age, gender, and experience) and constructs (performance

expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, hedonic

motivation, price value, and habit) when assessing and observing the influence of these

characteristics and constructs on the consumer’s behavioral intention and behavioral use

29

of technology (Venkatesh et al., 2012). Liu et al. (2015) used the UTAUT model to

examine factors that affect acceptance behavior and actual use of new technologies for

rehabilitation by therapists. Using the lens of this model, they found statistical support to

assert that rehabilitation professionals did not feel pressured from their co-workers to use

technologies, but ultimately utilized technologies because they were useful and/or helped

the clients (Liu et al., 2015). They also found that the expectation of having better patient

outcomes and increased job performance of the therapist, outweighs the hurdles of

learning to use new challenging technologies in practice (Liu et al., 2015). The Unified

Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 is a well suited theory to utilize when

examining the relationship of occupational therapy practitioners and their integration of

SHT into practice because of the extensive nature of the theory as it looks into individual

characteristics and constructs, and how these variables may influence the use of

technology.

Summary

As evidenced in the above pages, technology is ever-changing and will continue

to evolve in the future. Similarly, occupational therapy is a constant ever-changing

profession and leaders in the profession during this constant ever-changing era can and

should embrace the opportunities that technologies provide (Liu, 2018). As Liu (2018)

states “occupational therapists cannot be leaders in this new era unless we set aside our

fears and embrace the potential benefits of technologies” (p. 281). Occupational therapy

practitioners can bring many diverse, creative solutions to the table when implementing

technologies into client care, and can bring their expertise and understanding of the client

30

and human occupation into the discourse, design, and implementation of technologies

(Liu, 2018).

When occupational therapy practitioners show interest and see the benefits of

technology in care, they set the stage for the profession as a whole, as they are able to

offer more intervention strategies and see a wide range of clients with and without

disabilities. Although barriers to implementing technologies, such as access, time,

funding, workplace culture, personal interest, and knowledge, can deter occupational

therapy practitioners from using technologies, these same barriers can also be facilitators

if the practitioner seeks out these opportunities. Occupational therapy offers a unique

perspective to the smart technology industry and the profession, as they have the potential

to be gatekeepers, whether working directly with clients or assisting in the process of

developing technologies (Hayden, 2019). With the help of models of practice and guiding

Code of Ethics (AOTA, 2015), occupational therapists already have facilitators in place

to guide technology-based interventions with clients.

31

CHAPTER III

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The purpose of this study was to explore occupational therapy practitioners’

utility of smart home technology in their practice. Additionally, the student researchers

inquired into the factors that influence their use or non-use of this technology. Our

specific sub research questions are as follows:

• What relationships exist (if any) between factors identified and reported with use

of SHT?

• What relationships exist (if any) between factors identified and reported with

perceived effectiveness with SHT?

The results of this project provide an understanding of occupational therapy

practitioner’s perspectives on smart home technology (SHT), as well as facilitators and

barriers that commonly arise when using SHT. The research study followed a quantitative

research design utilizing survey methodology. A quantitative internet survey was chosen

because it is flexible and is the most common delivery method used to gather data on

healthcare professionals (Blessing, 2016). Three key advantages to using internet surveys

are (1) the sample size can be large and dispersed, (2) a large amount of data can be

collected, and (3) internet survey results can be downloaded to a database, eliminating

data entry and its associated errors, time, and costs for gathering data (Blessing, 2016). In

addition, a descriptive research design was used, more specifically a correlational

32

research design. This type of design is used to inquire about relationships between at least

two variables (Taylor & Kielhofner, 2017).

The framework utilized to guide this quantitative research study was the Unified

Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2) (Venkatesh, Thong, & Xu,

2012). The UTAUT2 is a theory developed by information systems researchers and

considers individual characteristics and constructs, of people and technology, when

evaluating the influence on the consumer’s behavioral intention and behavioral use of

technology (Venkatesh et al., 2012). The UTAUT2 was compatible to employ when the

researchers explored the relationship of occupational therapy practitioners and their

integration of SHT into practice, due to the fact that the theory’s extensive nature looks at

individuals and technology concurrently.

Locale of the Study

After gaining approval from the University of North Dakota’s Institutional

Review Board (IRB), the researchers sent out requests for survey participation virtually.

Specifically, social media was chosen to accommodate for participants all around the

world and for ease of access after work hours. A 30-question Qualtrics survey was

distributed to participants via social media pages, which included occupational therapy-

based Facebook pages that the researchers gained access to first before posting about the

survey. The sites included: OT4OT; AT4OT; and the University of North Dakota

Occupational Therapy Alumni page. A site that is not affiliated with Facebook that the

researchers also posted the survey on was CommunOT, which is an occupational therapy

blog site through the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). It is a place

for AOTA members to interact, engage, and share to build a professional online

33

community through asking questions and posing other discussion topics regarding current

care provided in the field (AOTA, 2019b). By using social media sites as an outlet, this

study was able to reach multiple participants of different geographic locations across the

globe, with possible differing cultural backgrounds.

Population/Sampling

There was minimal inclusion criteria for the population recruited; however, the

participants had to be occupational therapists or occupational therapy assistants who were

interested in providing their perceptions on smart technology by taking the online survey

tool. Participants did not have to be a certified Assistive Technology Practitioner (ATP),

and did not have to be currently utilizing smart technology in practice. Practitioners could

participate in the study regardless of gender, age, location in the world, area of practice or

population most treated, level of educational degree, years of experience in the

occupational therapy field, and experience with the use of technology, including smart

home technologies. Recruitment was conducted through purposive and convenience

sampling. Purposive sampling is done when the researcher seeks out potential

participants based on specific criteria (Porteny & Watkins, 2015). This was done in this

project and is represented in the fact that the researchers chose Facebook groups and

CommunOT because they were specific to OT practitioners, which is a part of the

inclusion criteria. Convenience sampling occurs when participants are recruited based on

availability (Porteny & Watkins, 2015). This is represented in this project because the

researchers reached out to potential participants via Facebook groups and CommunOT

and whoever was available to participate could, if they fit the inclusion criteria.

Survey Construction

34

When creating the survey tool, the researchers aimed to discover how often OT

practitioners were using SHT and what factors were identified as facilitators or barriers to

the use of technology. The questions were based on the fieldwork experiences of the

student researchers, personal educational experiences, and a thorough review of the

literature. The questions were not intended to be exhaustive. When conducting the

literature review the researchers found several variables that stood out to be either a

barrier or support for occupational therapy practitioners in their use of SHT. These

variables include knowledge (Dicianno et al., 2019; Hamblin, 2017; Jiancaro, Jaglal, &

Mihailidis, 2017; Kumar et al., 2013; Proffitt et al., 2019; Verdonck et al., 2011),

personal interest (Verdonck et al., 2011), workplace culture (Proffitt et al., 2019), and

funding (Assistive Technology Industry Association, 2019; Berridge, 2018; Dicianno et

al., 2019; Hamblin, 2017; Haymes, Storey, Maldonado, Post, & Montgomery, 2015;

Verdonck et al., 2011). In addition to the variables above, the researchers assert that

access and time are additional factors that support or inhibit the use of SHT by healthcare

professionals. The access and time variables were not mentioned in the literature that the

researchers reviewed. Because of this, the researchers made sure to add these factors to

the survey tool.

Several different question designs were used including multiple choice, checklist,

Likert, verbal frequency scales and open text entry. With checklist questions, the

participant was able to choose more than one answer that was provided. Likert scales are

of ordinal design and used to obtain participant’s thoughts on the question posed with

values for the answer choices (Blessing, 2016). Verbal frequency scales are similar to

Likert scales but may use more answer choices and do not include values (Blessing,

35

2016). The open text entry options allowed participants to provide additional relevant

options.

The survey tool included eleven demographic list response questions, both

multiple choice and checklist. The questions ranged from age, educational degree, and

country, to populations served and settings of practice. Next, three questions were

designed to analyze where participants learned about SHT, how much time they have

spent researching SHT, and if they have used SHT in their practice. A juxtaposed verbal

frequency scale was utilized to inquire about where participants learned about SHT.

Potential answers ranged from occupational therapy school, in-services, and conferences.

Multiple choice questions were used to find out about how much time researching SHT

was spent by the participant and if he or she used SHT in practice. If the participant

answered “no” to the use of SHT in practice, they were moved to the next block of

questions, in contrast, if they answered “yes”, there were several additional questions in

the block relating to the participant using SHT in practice. A verbal frequency scale was

used to find out how often the participant used SHT in practice and a multiple choice

question asked how many years he or she had been using the technology in practice.

Likert scales were used to ask about the participants comfort with using SHT and

perceived effectiveness with using SHT. Additionally, we utilized checklist questions to

inquire about funding sources the participant used to access SHT for his or her clients, as

well as supports the participant had for utilizing SHT with clients. In the next block of

questions, we wanted to learn about the participant’s interest in SHT and more specific

variables of barriers and supports. The researchers utilized a verbal frequency scale to

measure participants' interest in SHT. Verbal frequency scales were also used to measure

36

interest in researching SHT as well as the participants' perceived knowledge about SHT.

Next, multiple choice questions were used to ask about additional factors including: time

the participants had for researching SHT; how much access to SHT the respondent had; if

the respondent’s employer provided funding for the respondent to use SHT with clients;

and if the respondent had any additional funding sources. Lastly, a verbal frequency scale

was used to inquire about how much the respondent’s workplace supported the use of

SHT.

Instrumentation and Data Collection

The 30-question survey tool was built into Qualtrics survey software (see

Appendix A), which was chosen based on its confidentiality, dependability, and ease of

access to the researchers. When building the survey, the researchers examined the survey

through many lenses. The two student researchers, the research advisor, and an associate

professor in population health, who specializes in working with IBM Statistical Package

for the Social Sciences (SPSS), all analyzed and reviewed the survey for further edits

before submitting to the Institutional Review Board. Once approval was received from

the University of North Dakota’s Institutional Review Board (see Appendix B), the