April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

1

HP-2023-09

Updated National Survey Trends in Telehealth

Utilization and Modality (2021-2022)

Telehealth utilization rapidly expanded during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

and continues to provide critical access to health care services. Updated trends show

a steady use of telehealth with a slightly higher proportion of video-based versus

audio-only services by March 2022; however, disparities persist in populations and

across insurance types.

Euny C. Lee, Violanda Grigorescu, Idia Enogieru, Scott R. Smith, Lok Wong Samson, Ann B. Conmy,

and Nancy De Lew

KEY POINTS

• Telehealth utilization has changed since the steep increase from the early stages of the COVID-19

pandemic. This report updates prior findings on national trends of telehealth use through an analysis

using the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey data from April 2021 through August 2022.

Understanding patterns and factors associated with telehealth use are important to inform policy

decisions.

1-4

• Compared to earlier periods in the pandemic, telehealth utilization was lower during the study

period (April 14, 2021 through August 8, 2022), but continued to remain above pre-pandemic

levels.

5

• Telehealth use rates varied throughout the study period between 20.5% and 24.2%, with an average

of 22.0% of adults reporting use of telehealth in the last four weeks.

• Telehealth use rates were lowest among people who are uninsured (9.4%), young adults ages 18 to

24 (17.6%), and residents of the Midwest (18.7%).

• The highest rates of telehealth visits were among those covered by Medicaid (28.3%) and Medicare

(26.8%), individuals who are Black (26.1%), and those earning less than $25,000 (26.4%).

• Individuals who are Hispanic or Latino, Black, and Asian were more likely to use telehealth,

specifically audio-only telehealth, than individuals who are White; however, they were less likely to

use video telehealth services than individuals who are White. There were significant disparities

among subgroups in terms of audio-only versus video-based telehealth use.

• Persistent disparities in accessing video telehealth services requires further study on patient

preferences and how broadband programs, technology resources, and technology literacy training

programs can improve patient access to video telehealth services.

April 19, 2023

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

2

BACKGROUND

Telehealth use in the United States grew significantly within the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic

(January – March 2020), providing access to critical health services, enabling communication between health

care providers and patients, and remote monitoring of conditions through the use of synchronous, real-time

modalities via audio-only or internet-based video on mobile phones and digital devices as well as

asynchronous methods (e.g., store and forward and patient portals).

5, 6

Telehealth use in the last half of 2020 remained high, accounting for 30.2% of all health center visits during

June – November 2020, according to one study.

7

By April 2021, the national telehealth utilization rate among

adults ages 18 years and older was at 27%, which is lower than early pandemic telehealth use, but then

declined to 22% by mid-late 2021 based on an earlier ASPE study.

1

Analyses of commercial claims have shown

that telehealth services were mostly rendered by social workers and primary care and psychiatry/psychology

clinicians, with more than a quarter (26%) of claims for psychotherapy delivered through telehealth.

8

However,

while evidence on patient preferences regarding modality and the impact of telehealth on quality of care and

patient outcomes is still being explored, equitable access to telehealth services – particularly synchronous,

real-time video telehealth – remains a significant concern and potential barrier to health care during the

pandemic.

9

The expected end of the public health emergency on May 11, 2023 may impact telehealth flexibilities

introduced during the pandemic for various state Medicaid programs and private payers.

4

In addition, recent

legislation extended telehealth flexibilities for Medicare until December 31, 2024 to further understand

ongoing patterns of telehealth utilization and disparities which are critical to informed policy-making.

10

This report provides an update to an earlier ASPE Issue Brief that analyzed telehealth utilization using the

Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS) from April 14, 2021 to October 11, 2021.

1

Specifically, in this

study, national trends in telehealth utilization were analyzed from April 14, 2021 through August 8, 2022 with

results that are similar to the previous analysis. In addition, descriptive and multivariable regression analyses

were performed to better understand telehealth use and more specifically video-enabled telehealth among

different populations.

METHODS

Data Sources

We used the Household Pulse Survey (HPS) data. This is an online survey, administered by the Census Bureau

to measure U.S. households’ experiences and impact of emerging issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. The

HPS response rate ranges from 1.3% to 10.3% and varies across survey cycles.

11

Respondents must be adults ages 18 and older and they are asked to answer questions on use of telehealth for

both themselves and children in their household.

*

_______________________

*

The survey telehealth questions included the following: “At any time in the last 4 weeks, did you have an appointment with a doctor,

nurse, or other health professional by video or by phone? Please only include appointments for yourself and not others in your

household.” “At any time in the last 4 weeks, did any children in the household have an appointment with a doctor, nurse, or other

health professional by video or by phone?” For those who selected Yes: “Did the appointment(s) take place over the phone without

video or did the appointment(s) use video?”

† We grouped respondents based on their answers to health insurance coverage into five mutually exclusive categories: 1) Medicare; 2)

Medicaid; 3) Private; 4) Other Health Insurance, and 5) Uninsured.

‡ Biological sex and gender identity were excluded from the overall telehealth analysis, due to a change in the definition of gender in

the survey as of July 21, 2021.

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

3

Data on overall telehealth use was available for the weeks between April 14, 2021 through August 8, 2022, our

study period. Information on telehealth service by modality (audio-only vs. video telehealth) was available only

for the weeks from July 21, 2021 to August 8, 2022.

12

Data Analysis

Overall telehealth use was evaluated from April 14, 2021, to August 8, 2022, for adult telehealth users

(N=265,367). Analysis by telehealth modality (video vs. audio-only) was performed on a secondary cohort* (N=

143,462 respondents from July 21, 2021 through August 8,2022)) representing a subset of the first cohort of

overall telehealth users.

The data were weighted using person-level weights and replicate weights to account for sampling and

response bias.

11

Descriptive statistics followed by bivariate analysis (stratification and crosstabulations) and

multivariable logistic regression modeling were conducted for both cohorts to identify predictors of telehealth

use. Independent variables in the multivariable model included race and ethnicity, age, gender, education,

income, insurance, and region. We repeated our multivariable analysis with the sample stratified by insurance

type. A p-value below .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses used survey weights to mitigate

non-response bias and Taylor Series Expansion/Linearization for variance estimation.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Telehealth Users

Among the 1,180,248 adults who answered the

telehealth question, 22.5% reported having utilized

telehealth services (audio-only or video) within the

last four weeks. Among 367,887 adults with a child in

the household, 18.1% reported that a child in the

household had used telehealth services in the prior

four weeks.

Figure 1 shows trends in the percentage of adults and

children that had used telehealth services in the prior

four weeks. There was a slight decline in overall

telehealth use in July 2021 that persisted until June

of 2022 before climbing again slightly; however,

telehealth use among adults remained above 20% throughout the study period. Rates for children were slightly

lower, and the gap compared to adults has gradually widened over time. While other studies have found that

overall rates of telehealth use have remained fairly stable for adults, rates for children have gradually declined

in 2022.

13

In one study, telehealth use among pediatric patients varied by subspecialty ranging from 6% to 73%

of total visits with a preference for in-person visits among those having non-English language preference.

14, 15

Telehealth use consistently

remained above 20% from

2021-2022 and for all

population groups.

Disparities persisted in video

utilization from July 2021 to

August 2022.

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

4

Figure 1. Percentage of Adults and Children* Who Used Telehealth Services, April 14, 2021 – August 8, 2022

Figure 2 illustrates the share of adults with telehealth visits who utilized audio-only versus video telehealth.

More than half of telehealth users reported use of video telehealth during each wave of the survey from July

2021 to August, 2022, but decreased during June 1, 2022 through August 8, 2022, for reasons that are not yet

well understood.

Note: *Reflects telehealth use reported by adult respondents for any child in the household over the

previous 4 weeks. Note that the survey is typically on a bi-weekly basis, although some weeks were

not surveyed, such as weeks in November of 2021.

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

5

Figure 2. Percentage of Adults Who Used Audio-only vs. Video Telehealth Services, July 21, 2021 – August 8,

2022

Demographic Characteristics of Overall and Audio-only vs. Video Adult Telehealth Use

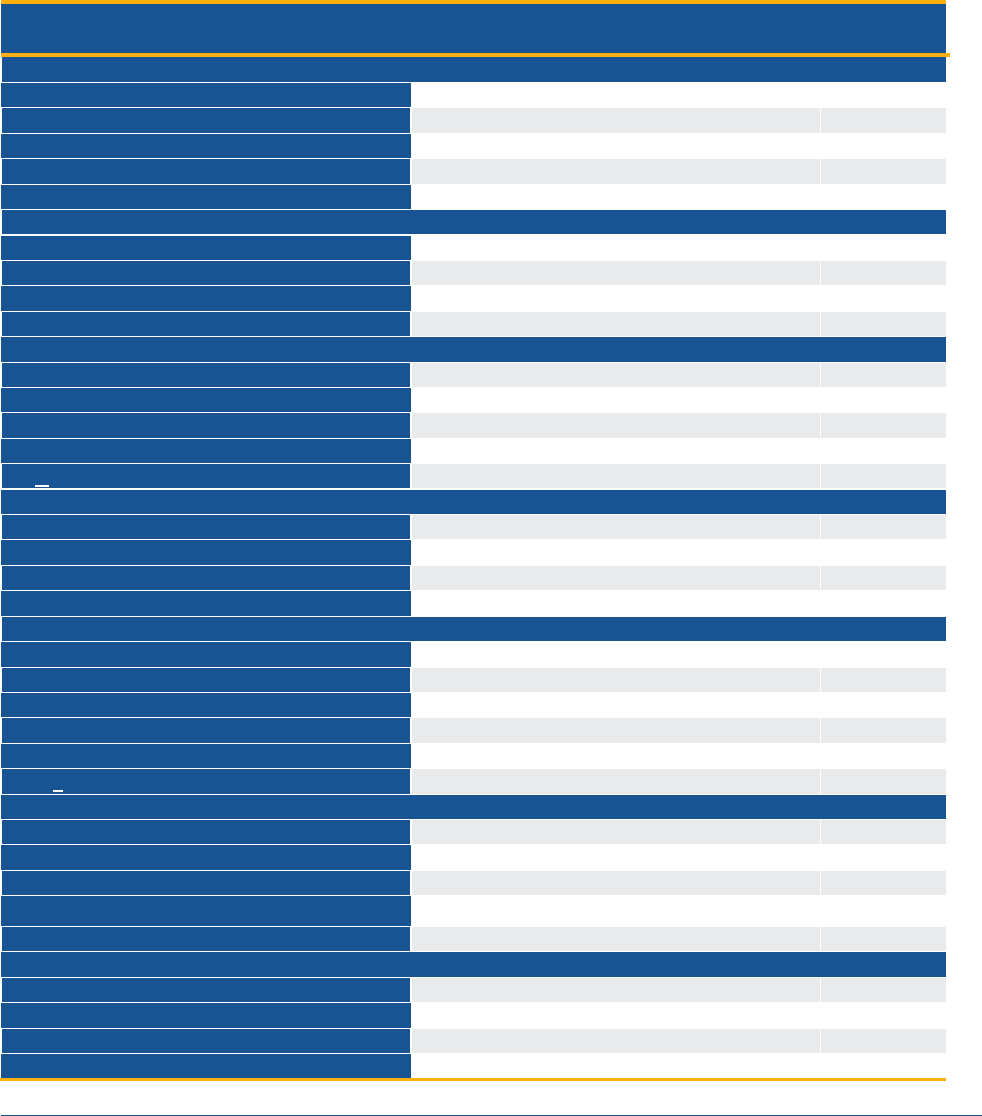

Table 1 presents the findings by demographic categories for each of the two cohorts analyzed: overall

telehealth users (first cohort) and the proportion of survey respondents who reported the modality of

telehealth visit in the prior four weeks from July 2021-August 2022 (second cohort).

Among survey respondents (first cohort), telehealth utilization was lowest among people who were uninsured

(9.4%), individuals ages 18-24 (17.6%), and those residing in the Midwest (18.7%). Telehealth use was highest

among those with Medicaid (28.3%) and Medicare (26.8%), Black respondents (26.1%), and those earning less

than $25,000 (26.4%).

Subgroup analysis comparing audio-only vs. video telehealth among telehealth users was conducted for the

second cohort* surveyed between July and August 2021. Although we acknowledge differences in the two

cohorts that make them not comparable, we noted that the characteristics of those reporting higher

proportion of video services (second cohort) were similar with those having a lower overall telehealth use (first

cohort). Among these respondents (second cohort), higher proportion of video visits compared to audio-only

visits were observed in those having lower overall rates of telehealth use. For example, White respondents

reported having an overall telehealth use of 19.6% but had a higher proportion of their telehealth visits using

video (61.3%) compared to audio-only (38.7%). This pattern remained consistent among telehealth users who

were between 18 and 24 years of age (72.5%), and private health insurance enrollees (65.3%). Audio-only

telehealth use was highest among those with less than a high school education (64.2%) and adults ages 65 and

58 58

57

58

60

58

57

56

58

60 60

57

55

54

53

42 42

43

42

40

42

43

44

42

40 40

43

45

46

47

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Percentage (%) of audio vs. video telehealth use

Week Survey was Administered

(HPS weeks 34-48)

Audio vs. Video Telehealth Use

Video Telehealth

Audio Telehealth

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

6

older (56.5%). These results are similar to the findings from our previous analysis of Census HPS data through

October 11, 2021.

1

* Note: The telehealth modality question was included in the Household Pulse Survey (HPS) starting July 21,

2021.

Table 1. Rates of Telehealth Use and Audio-only vs. Video Modality, by Demographic Categories, April 14,

2021 – August 8, 2022

% with a

Telehealth Visit

in Previous Four

Weeks

April 14, 2021 to

August 8, 2022

Second Cohort* (July 21, 2021 to August 8, 2022)

% with a

Telehealth Visit in

Previous Four

Weeks

% of Telehealth

Visits by Video in

Previous Four

Weeks

% of Telehealth

Visits by Audio-

only in Previous

Four Weeks

Race and Ethnicity

Hispanic or Latino

23.9

22.7

49.7

50.3

White alone, not Latino

20.7

19.6

61.3

38.7

Black alone, not Latino

26.1

25.0

50.1

49.9

Asian alone, not Latino

21.7

20.8

49.5

50.5

Two or more races + Other

25.5

24.2

59.8

40.2

Age

18-24 years

17.6

16.0

72.5

27.5

25-39 years

20.7

18.6

69.3

30.7

40-54 years

22.7

20.9

60.9

39.1

55-64 years

23.6

21.1

52.1

47.9

> 65 years

24.6

22.0

43.5

56.5

Education

Less than high school

24.5

24.0

35.8

64.2

High school or GED

20.7

19.7

46.5

53.5

Some college/Associate’s

degree

22.8

21.6

58.3

41.7

Bachelor’s degree or higher

22.4

21.3

66.7

33.3

Household Income

Less than $25,000

26.4

25.3

47.6

52.4

$25,000 - $34,999

23.3

21.9

48.9

51.1

$35,000 - $49,999

21.8

20.6

53.3

46.7

$50,000 - $74,999

21.0

19.9

56.9

43.1

$75,000 - $99,999

20.2

19.2

62.0

38.0

> $100,000

20.4

19.4

67.9

32.1

Insurance

Medicare

26.8

25.5

46.1

53.9

Medicaid

28.3

26.8

53.4

46.6

Private

20.2

19.2

65.3

34.7

Other Health Insurance

24.4

23.1

53.8

46.2

Uninsured

9.4

9.0

46.9

53.1

Census Region

Northeast

23.3

22.3

59.6

40.4

South

21.3

20.1

58.0

42.0

Midwest

18.7

17.7

57.7

42.3

West

24.9

23.9

54.1

45.9

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

7

Figure 3 illustrates disparities in video telehealth use by race and ethnicity; video telehealth as a share of all

telehealth use was lower among Hispanic or Latino (49.7%), Asian (49.5%), and Black (50.1%) survey

respondents.

Figure 3. Telehealth Modality (Video vs. Audio-only) Among Telehealth Users, By Race/Ethnicity, July 21,

2021 – August 8, 2022

Demographic Predictors Associated with Telehealth Use (Multivariable Model: First Cohort)

Table 2 shows the demographic factors that were predictors of recent telehealth use after multivariable

adjustment (first cohort). Those who were Hispanic or Latino, Black, or reported two or more races or other

race had higher odds of using telehealth in the last 4 weeks than White non-Latino respondents. In addition,

telehealth use was highest among those with lower incomes and declined as income rises. Individuals with

Medicare, Medicaid, or Other insurance

†

were more likely to use telehealth than those with Private Insurance,

while people without any health insurance were the least likely to use telehealth.

_______________________

†

Other insurance includes: TRICARE or other military health care, Veteran’s Administration (VA) Health Care, Indian Health Service

(IHS), and Other health insurance.

49.7

61.3

50.1

49.5

59.8

50.3

38.7

49.9

50.5

40.2

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Hispanic or

Latino

White Black Asian Two or more

races + Other

% of utilization by telehealth users

Telehealth Use by Modality

% video telehealth % audio telehealth

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

8

Table 2: Adjusted Odds of Telehealth Utilization by Respondent Demographics, April 14, 2021 – August 8,

2022

Demographics

Odds Ratios

(95% Confidence Interval)

P-value

Race and Ethnicity

Hispanic or Latino

1.27 (1.22, 1.33)

<.0001

Black alone, not Latino

1.36 (1.30, 1.42)

<.0001

Asian alone, not Latino

1.02 (0.96, 1.08)

0.6085

Two or more races + Other Races, not Latino

1.27 (1.20, 1.35)

<.0001

White alone, not Latino

Ref*

Ref*

Age

18-24 years

1.06 (0.96, 1.16)

0.2701

25-39 years

1.19 (1.12, 1.26)

<.0001

40-54 years

1.35 (1.28, 1.43)

<.0001

55-64 years

1.39 (1.32, 1.46)

<.0001

> 65 years

Ref*

Ref*

Education

Less than high school

0.91 (0.78, 1.05)

0.1988

High school or GED

0.77 (0.74, 0.80)

<.0001

Some college/Associate’s degree

0.95 (0.92, 0.97)

<.0001

Bachelor’s degree or higher

Ref*

Ref*

Household Income

Less than $25,000

1.41 (1.34, 1.48)

<.0001

$25,000 - $34,999

1.27 (1.21, 1.34)

<.0001

$35,000 - $49,999

1.15 (1.10, 1.21)

<.0001

$50,000 - $74,999

1.06 (1.03, 1.10)

0.0011

$75,000 - $99,999

1.03 (0.99, 1.07)

0.1532

> $100,000

Ref*

Ref*

Insurance

Medicare

1.70 (1.62, 1.79)

<.0001

Medicaid

1.36 (1.30, 1.44)

<.0001

Private

Ref*

Ref*

Other Health Insurance

1.24 (1.13, 1.35)

<.0001

Uninsured

0.35 (0.32, 0.38)

<.0001

Census Region

Northeast

0.91 (0.88, 0.95)

<.0001

South

0.82 (0.79, 0.85)

<.0001

Midwest

0.70 (0.67, 0.72)

<.0001

West

Ref*

Ref*

†Telehealth modalities were unavailable until HPS week 34 conducted on July 21, 2021.

‡ Insurance categories were coded to be mutually exclusive.

* Reference value/control group for calculation of odds ratios intervals.

Table 3 shows the demographic predictors of video telehealth among telehealth users after multivariable

adjustment (second cohort). Age was the strongest predictor of video telehealth use, with young adults having

an odds ratio of 4.55 compared to adults 65 and older and a declining rate of video telehealth use for each

older age group. Compared to females, males were less likely to use video telehealth, whereas transgender

individuals were 3.12 times more likely to use video telehealth.

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

9

Video telehealth use was less likely among lower income households and those with lower educational

attainment compared to those who had a household income of ≥ $100,000 and a bachelor’s degree or higher.

The rates of video telehealth use rose steadily as household income or educational attainment increased.

Black, Hispanic or Latino, and Asian individuals were less likely to use video telehealth than White respondents,

with Asians having the lowest odds ratio of 0.55. Respondents who were insured by Medicare were 1.23 times

more likely to use video telehealth compared to those who were insured by a private payer. Lastly, those

residing in the Midwest region were less likely to use video telehealth compared to those residing in the West.

Table 3: Predictors of Video Telehealth Utilization Among Telehealth Users, July 21, 2021 – August 8, 2022

Demographics

Odds Ratios

(95% Confidence Interval)

P-value

Race and Ethnicity

Hispanic or Latino

0.74 (0.66, 0.83)

<.0001

Black alone, not Latino

0.85 (0.76, 0.96)

0.0077

Asian alone, not Latino

0.55 (0.47, 0.64)

<.0001

Two or more races + Other, not Latino

0.98 (0.84, 1.14)

0.7527

White alone, not Latino

Ref*

Ref*

Gender Identity

Male

0.929 (0.87, 1.00)

0.038

Female

Ref*

Ref*

Transgender

3.12 (1.72, 5.68)

0.0002

Other

1.10 (0.83,1.46)

0.4998

Age

18-24 years

4.55 (3.51, 5.91)

<.0001

25-39 years

4.12 (3.60, 4.71)

<.0001

40-54 years

2.73 (2.42, 3.08)

<.0001

55-64 years

1.92 (1.70, 2.16)

<.0001

> 65 years

Ref*

Ref*

Education

Less than high school

0.50 (0.347 0.709)

0.0001

High school or GED

0.60 (0.541 0.657)

<.0001

Some college/associate’s degree

0.81 (0.753 0.864)

<.0001

Bachelor’s degree or higher

Ref*

Ref*

Household Income

Less than $25,000

0.61 (0.54, 0.69)

<.0001

$25,000 - $34,999

0.61 (0.54, 0.70)

<.0001

$35,000 - $49,999

0.69 (0.61, 0.78)

<.0001

$50,000 - $74,999

0.76 (0.69, 0.84)

<.0001

$75,000 - $99,999

0.82 (0.74, 0.91)

0.0002

> $100,000

Ref*

Ref*

Insurance

Medicare

1.23 (1.09, 1.38)

0.0005

Medicaid

0.99 (0.87, 1.13)

0.8709

Private

Ref*

Ref*

Other Health Insurance

0.97 (0.78, 1.22)

0.8145

Uninsured

0.73 (0.57, 0.94)

0.0137

Census Region

Northeast

1.07 (0.96, 1.19)

0.2474

South

1.05 (0.96, 1.14)

0.2648

Midwest

0.86 (0.78, 0.94)

0.0015

West

Ref*

Ref*

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

10

†Telehealth modalities were unavailable until HPS week 34 conducted on July 21, 2021.

‡ Insurance categories were coded to be mutually exclusive.

*Reference value/control group for calculation of odds ratios intervals.

Table 4 shows demographic predictors of video telehealth use by individuals, stratified by different insurance

types. Disparities in access to video telehealth were observed in most insurance types similar to the overall

telehealth users. Generally, younger adults, those with higher incomes, and those with more education were

more likely to use video telehealth across insurance types. One notable exception is the absence of disparities

among Black and Latino respondents compared to White respondents covered by Medicare; however,

disparities in video telehealth access were greater among Asian respondents. These findings suggest Medicare

may provide more equitable access to video telehealth services compared to other payers but can improve its

access for Asians.

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

11

Table 4: Predictors of Video Telehealth Utilization Among Telehealth Users, Stratified by Insurance Type, July 21, 2021 – August 8, 2022

* Significant – p-value below 0.05

**Reference value/control group for calculation of odds ratios intervals.

Demographics

Medicare

OR (95% CI) P-value

Medicaid

OR (95% CI) P-value

Private

OR (95% CI) P-value

Other Health Insurance

OR (95% CI) P-value

Uninsured

OR (95% CI) P-value

Race and Ethnicity

Hispanic or Latino

0.88 (0.71, 1.11)

0.286

0.57 (0.43, 0.77)

0.0002*

0.76 (0.66, 0.88)

0.0003*

1.08 (0.61, 1.91)

0.787

0.50 (0.28, 0.89)

0.017*

Black alone, not Latino

1.08 (0.89, 1.31)

0.453

0.62 (0.46, 0.83)

0.001*

0.83 (0.70, 0.99)

0.037*

0.57 (0.31, 1.03)

0.060

0.99 (0.49, 1.99)

0.969

Asian alone, not Latino

0.49 (0.34, 0.70)

0.0001*

0.42 (0.23, 0.76)

0.004*

0.59 (0.49, 0.71)

<.0001*

1.51 (0.52, 4.32)

0.447

0.24 (0.09, 0.66)

0.006*

Two+ races / Other, not Latino

0.98 (0.73, 1.33)

0.915

0.76 (0.52, 1.10)

0.142

1.01 (0.82, 1.23)

0.952

1.62 (0.75, 3.48)

0.221

0.78 (0.25, 2.41)

0.659

White alone, not Latino

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Gender Identity

Male

0.92 (0.82, 1.04)

0.171

0.97 (0.76, 1.25)

0.833

0.96 (0.88, 1.05)

0.387

0.97 (0.65, 1.45)

0.863

0.50 (0.31, 0.79)

0.003*

Female

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Transgender

4.37 (0.92,

20.75)

0.063

3.18 (1.26, 8.04)

0.015*

2.21 (1.02, 4.76)

0.044*

755.88, (19.52,

>999.99)

0.0004*

2.26 (0.2, 25.34)

0.510

Other

1.01 (0.59, 1.73)

0.987

1.2 (0.63, 2.3)

0.575

1.15 (0.77, 1.71)

0.495

0.75 (0.21, 2.66)

0.652

0.83 (0.18, 3.94)

0.814

Age

18-24 years

9.92 (3.57, 27.6)

<.0001*

3.14 (1.30, 7.56)

0.011*

5.04 (3.63, 7.00)

<.0001*

3.49 (1.03, 11.75)

0.044*

2.26 (0.48,

10.77)

0.305

25-39 years

4.02 (2.67, 6.05)

<.0001*

3.85 (1.92, 7.73)

0.0001*

4.34 (3.60, 5.24)

<.0001*

2.37 (1.17, 4.83)

0.017*

2.2 (0.67, 7.26)

0.197

40-54 years

2.31 (1.88, 2.83)

<.0001*

2.26 (1.13, 4.51)

0.021*

3.13 (2.61, 3.76)

<.0001*

1.44 (0.73, 2.85)

0.290

1.41 (0.43, 4.69)

0.571

55-64 years

2.25 (1.90, 2.67)

<.0001*

1.69 (0.83, 3.46)

0.151

1.97 (1.63, 2.37)

<.0001*

0.99 (0.53, 1.84)

0.967

1.07 (0.32, 3.62)

0.914

> 65 years

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Education

Less than high school

0.51 (0.28, 0.94)

0.030*

0.50 (0.24, 1.04)

0.062*

0.34 (0.17, 0.67)

0.002*

0.03 (0.00, 0.32)

0.004*

1.51 (0.50, 4.59)

0.466

High school or GED

0.67 (0.58, 0.79)

<.0001*

0.57 (0.43, 0.75)

<.0001*

0.59 (0.51, 0.68)

<.0001*

0.53 (0.29, 0.95)

0.033*

0.70 (0.41, 1.19)

0.187

Some college/associate’s degree

0.84 (0.75, 0.94)

0.002*

0.87 (0.69, 1.10)

0.240

0.76 (0.69, 0.84)

<.0001*

1.14 (0.76, 1.70)

0.537

1.04 (0.64, 1.68)

0.882

Bachelor’s degree or higher

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Household Income

Less than $25,000

0.50 (0.41, 0.61)

<.0001*

0.66 (0.42, 1.04)

0.073

0.61 (0.49, 0.78)

<.0001**

1.04 (0.52, 2.09)

0.906

0.97 (0.43, 2.18)

0.938

$25,000 - $34,999

0.57 (0.46, 0.7)

<.0001*

0.62 (0.38, 1.00)

0.050*

0.65 (0.53, 0.79)

<.0001*

0.69 (0.35, 1.34)

0.268

0.7 (0.29, 1.71)

0.429

$35,000 - $49,999

0.72 (0.59, 0.88)

0.001*

0.62 (0.37, 1.03)

0.065

0.69 (0.57, 0.82)

<.0001*

0.77 (0.4, 1.47)

0.423

0.94 (0.37, 2.37)

0.895

$50,000 - $74,999

0.71 (0.59, 0.85)

0.0002*

0.79 (0.46, 1.35)

0.386

0.79 (0.70, 0.90)

0.0002*

0.71 (0.36, 1.42)

0.336

1.13 (0.48, 2.64)

0.777

$75,000 - $99,999

0.86 (0.71, 1.04)

0.125

0.91 (0.44, 1.91)

0.810

0.81 (0.72, 0.92)

0.001*

0.78 (0.38, 1.6)

0.498

0.9 (0.32, 2.58)

0.850

> $100,000

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Ref**

Census Region

Northeast

0.85 (0.7, 1.02)

0.086

1.03 (0.76, 1.39)

0.866

1.24 (1.07, 1.42)

0.003*

1.42 (0.64, 3.17)

0.387

0.91 (0.39, 2.14)

0.825

South

0.66 (0.56, 0.77)

<.0001*

0.87 (0.66, 1.15)

0.325

0.98 (0.86, 1.11)

0.712

1.2 (0.65, 2.19)

0.563

0.85 (0.42, 1.71)

0.643

Midwest

0.80 (0.7, 0.93)

0.003*

1.12 (0.86, 1.45)

0.421

1.18 (1.06, 1.33)

0.003*

1.56 (0.96, 2.52)

0.073

0.79 (0.46, 1.37)

0.401

West

Ref

Ref

Ref

Ref

Ref

Ref

Ref

Ref

Ref

Ref

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

12

DISCUSSION

Overall, 22.0% of adults reported using telehealth in the last four weeks of the study period (from April 2021 to

August 2022), which is comparable to ASPE’s previous analysis.

1

It should be noted that the Census Pulse data

on telehealth use reported in this paper is markedly lower, most likely due to the shorter reference period of

telehealth use (four weeks only), compared to higher rates of telehealth use by adults (37.0%) in twelve

months that was reported using the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) administered by CDC.

16-18

The methodology is different as well. The NHIS is a long running nationally-representative health survey that

tracks a number of health care metrics. The HPS, launched in 2020, was designed as an experimental data

collection initiative to provide near real-time national estimates based on weighting procedures and

administered as a 20-minute online survey to adults 18 years and older. Another difference to note is that the

HPS included questions on modality, (video, and audio-only), while this information cannot be obtained using

the NHIS because no questions related to telehealth modality were included in the survey.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth has emerged as an important modality for many, especially

those in underserved communities where it has resulted in a reduction of no-show rates.

19,20

Despite the

enhanced access to health care, disparities in video telehealth access continue to persist among older

patients, people of color, and those with low technology literacy.

21, 22

In addition, factors such as inadequate

infrastructure (e.g., internet connection, technology access, workflows) may impact a provider’s ability to

offer video telehealth.

23

One study found that providers in small practices from communities with high

social vulnerability

‡

were almost twice as likely as providers in communities with low social vulnerability to

use telephones as their primary telehealth modality.

24, 25

Emerging evidence suggests patient satisfaction is higher with video telehealth visits compared to audio-only

telehealth.

26, 27

Studies have also shown that consults via video telehealth are preferred by patients,

28

with

evidence of improved patient outcomes

29

and being less likely to have emergency department (ED) visits, in-

person, and hospital visits compared to those who did not use video telehealth.

30

However, there is conflicting

evidence on whether there are disparities in patient satisfaction with telehealth services among Asian

patients.

31

More evidence is needed on patient preferences of telehealth modalities (e.g., video vs. audio

telehealth) compared to each other and to usual care (in-person visits).

32

In addition, it is important to expand

on smaller studies

33

and studies outside of the U.S.

34

to assess whether there are any differences in these

preferences and patient perceptions of their care across populations in the U.S.

Our subgroup analysis found disparities in video telehealth use across payers. For example, Black, Hispanic or

Latino, and Asian individuals covered by Medicaid and private insurance were less likely to use video

telehealth; however, our model showed that only Asians were less likely to use video telehealth among those

covered by Medicare while both Hispanic or Latinos and Asians were less likely to use video telehealth among

individuals who are uninsured.

Those covered by Medicaid had the highest rate of telehealth utilization compared to individuals with other

sources of coverage, comparable to findings from a previous ASPE analysis.

1

However, based on an ASPE report

from January 2022, the status of state Medicaid telehealth flexibilities varied widely and continued to change

frequently throughout the pandemic.

4

Some states expanded the use of telehealth permanently, others

rescinded all or some of their telehealth flexibilities making some permanent through state legislation, while

others were maintained pending the expiration of their state or federal PHE declaration. Variations in state

_______________________

‡

The CDC defines social vulnerability as “the potential negative effects on communities caused by external stresses on human health.

Such stresses include natural or human-caused disasters, or disease outbreaks. Reducing social vulnerability can decrease both human

suffering and economic loss.”

23

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

13

Medicaid telehealth policies may impact patients’ and providers’ understanding of what types of visits will be

covered and how services should be billed. There are also numerous equity implications in a telehealth

landscape that is constantly shifting. When both federal and state PHEs expire and Medicaid redeterminations

resume starting on April 1, 2023, millions of those insured by Medicaid will be impacted through changes in

health insurance coverage and may experience changes in their access to health care services, including those

provided by telehealth.

10

The findings of our study suggest those insured by Medicare as being more likely to use telehealth and video

telehealth. These findings are consistent with our previous HPS analysis

1

and Medicare FFS claims analyses

conducted by ASPE which showed significant increases in use of telehealth by those insured by Medicare

during the pandemic.

2

However, those responding to the HPS survey may have higher digital literacy or

internet access given its administration as an online survey. Another study found individuals covered by

Medicare are less likely to use video telehealth. This study also noted that a potential reason for an overall

decrease in telehealth use among older patients may be related to their demographic and geographic

distribution, such as a higher share of older adults living in rural areas and lower rates of internet access.

35

Our study also found respondents reporting as Hispanic or Latino, Black, two or more races and other races

had higher overall telehealth use than White or Asian respondents. Despite higher odds of overall telehealth

use, Hispanic or Latino, Black, and Asian respondents were significantly less likely to use video telehealth—

particularly among those with Medicaid or private coverage—compared to their White counterparts. Video

telehealth use rates increased with higher income and education levels and younger age. These results are

somewhat counter to a study based on an analysis of the American Life Panel survey, which showed that video

telehealth use was highest in early 2021 among Black adults, and among those who were younger, had less

than high school education, and had lower income. In addition, the study reported respondents’ desire to use

video telehealth had increased from pre-pandemic estimates.

36

Our results are, however, similar to other studies finding disparities in video access to telehealth. For instance,

in a study of neurology patients, demographic predictors of those less likely to use video telehealth compared

to audio-only telehealth use included patients who were low-income, Black, and those insured by Medicare or

Medicaid.

30

Other studies have also shown lower success in initiating video telehealth visits among Hispanic or Latino

patients, those who had low socioeconomic status (SES), and individuals insured by Medicare or Medicaid.

21, 37,

38

Potential reasons for unsuccessful initiation of video telehealth visits may be potential technology barriers,

as evidenced in one study including those who did not activate their patient portal prior to the visit.

39

Another

study compared video telehealth utilization pre and post COVID-19 PHE and found lower video telehealth rates

among males, Asian, Black, American Indian / Alaska Native patients, patients who had limited English

proficiency, and those who were insured by Medicaid or Medicare.

40

Younger patients had a preference for

video telehealth compared to older adults.

41

In general, these patterns of disparities likely reflect structural barriers to video telehealth, such as access to

technology, devices, broadband internet, technology literacy, and structural racism.

40

Additional research is

needed on which health conditions and health services are clinically appropriate to be delivered via telehealth

as well as whether video or audio may be a clinically preferred telehealth modality. For example, video

telehealth visits may be more appropriate than audio visits for certain clinical conditions and health services

requiring visual clues and examination (e.g., dermatology and surgical wound care).

42

However, if health

services cannot be accessed in the modality (in-person, video or audio telehealth) associated with the

strongest evidence, patient populations may be limited in accessing higher quality care which may affect

health outcomes.

43

Further assessment of telehealth’s impact on health outcomes will also require

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

14

standardized measures such as the Health Care Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality

performance measures.

44

Limitations

This analysis has several limitations including the survey’s response rate that ranges from 1.3 percent to 10.3

percent, depending on the week. Despite applying weights to mitigate non-response bias, the inherent nature

of internet-based surveys can produce a bias based on the respondents’ internet accessibility and level of

comfort and familiarity with technology. Those who have access to technology and higher levels of health

literacy in general, as well as digital literacy, are more likely to respond to online surveys such as the HPS,

which can limit its generalizability to other populations. Our analysis was not able to control for baseline

differences in overall rates of health care use. Groups reporting higher telehealth use in the last four weeks

may simply reflect groups that are more likely to use health care services. Finally, the HPS did not include data

to distinguish rural and urban geographic areas; therefore, a comparison could not be made.

Policy Implications

Recent studies showed that video telehealth utilization is associated with a clinical provider’s perception of its

quality and comparability to in-person visits,

45

as well as whether available technologies are functional and

user-friendly in supporting video telehealth.

46

Furthermore, limited technology and health literacy continue to

pose challenges for accessing telehealth services among patients with limited English proficiency (LEP). New

evidence suggests prior video visit experience may help overcome barriers to video telehealth use.

47

However,

the current state of technology and user-friendliness of remote monitoring devices that link to telehealth visits

vary, as well as its acceptance among patients, especially those requiring assistance from others initiating

telehealth visits and interventions.

48

A resource that has been studied to enhance accessibility of telehealth has been the use of patient navigators

and community health workers to support patients in a telehealth visit. In addition to improving access to

video visits, one study demonstrated a return on investment (ROI) through increased adherence to clinic visits

that offset implementation costs.

49

This suggests additional policies may be considered for patient navigators

and community health workers to assist patients with telehealth visits.

While video telehealth may be more comparable to in-person visits, audio-only telehealth continues to be

important as it provides critical health care access for marginalized populations who lack access to technology,

broadband or ability to navigate a video telehealth visit. More work needs to be done to enable equitable

access to video telehealth by addressing disparities that are further exacerbated by lack of broadband access

or limitations in high-speed access impacting those residing in rural areas the most.

50

The challenge with

adequate broadband access are being addressed through programs and grants offered by the Federal

Communications Commission (FCC) and the U.S. Department of Commerce National Telecommunications and

Information Administration (NTIA) with appropriations from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

(IIJA).

51,52,53

In the future, new alternative models for telehealth expansion may need to consider potential

access issues

54

especially among individuals who are uninsured.

19

CONCLUSION

Our study describes recent trends in the use of telehealth during the pandemic that may have implications for

policymakers as they consider whether to continue policies and flexibilities that enable access to telehealth

services. In addition, our study suggests the importance of reducing disparities in accessing telehealth services,

especially video, and highlights the need to improve access by providing more focused outreach to

communities who have lower levels of video telehealth utilization.

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

15

REFERENCES

1. Karimi M, Lee EC, Couture SJ, Gonzales AB, Grigorescu V, Smith SR, De Lew N, Sommers BD. National Trends in

Telehealth Use in 2021: Disparities in Utilization and Audio vs. Video Services. (Research Report No. HP-2022-04). Office

of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U. S. Department of Health andHuman Services. Research Report.

February 2022. Accessed August 2, 2022.

https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/4e1853c0b4885112b2994680a58af9ed/telehealth-hps-ib.pdf

2. Samson L, Tarazi W, Turrini G, Sheingold S. Medicare Beneficiaries’ Use of Telehealth in 2020: Trends by Beneficiary

Characteristics and Location. (Issue Brief No. HP-2021-27). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. December

2021. Accessed August 2, 2022.

https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/a1d5d810fe3433e18b192be42dbf2351/medicare-telehealth-

report.pdf

3. Chu R, Peters C, De Lew, N, and Sommers BD. State Medicaid Telehealth Policies Before and During the COVID-19 Public

Health Emergency. (Issue Brief No. HP-2021-17). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. July 2021. Accessed

August 2, 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/eb9e147935a2663441a9488e36eea6cb/medicaid-

telehealth-brief.pdf

4. Rudich J, Conmy AB, Chu R, Peters C, De Lew N, Sommers BD. State Medicaid Telehealth Policies Before and During the

COVID-19 Public Health Emergency: 2022 Update. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services. November 2022. Accessed February 21, 2023.

https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/190b4b132f984db14924cbad00d19cce/Medicaid-Telehealth-IB-

Update-Final.pdf

5. Koonin LM, Hoots B, Tsang CA, et al. Trends in the Use of Telehealth During the Emergence of the COVID-19 Pandemic -

United States, January-March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Oct 30 2020;69(43):1595-1599.

doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a3

6. HRSA. What is telehealth? Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed June 9, 2021.

https://telehealth.hhs.gov/patients/understanding-telehealth/

7. Demeke HB, Merali S, Marks S, et al. Trends in Use of Telehealth Among Health Centers During the COVID-19 Pandemic

— United States, June 26–November 6, 2020. Vol. 70.240–244. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021. February 19, 2021

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7007a3.htm

8. FAIR HEALTH. Telehealth Utilization Fell Nearly Four Percent Nationally in June 2022. CISION PR Newswire; 2022.

September 12, 2022. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/telehealth-utilization-fell-nearly-four-percent-

nationally-in-june-2022-301621770.html

9. White-Williams C, Liu X, Shang D, Santiago J. Use of Telehealth Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups in the United

States Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Health Rep. Sep 16 2022:333549221123575.

doi:10.1177/00333549221123575

10. Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs.Fact Sheet: COVID-19 Public Health

Emergency Transition Roadmap. HHS Press Office; February 9, 2023, Accessed February 21, 2023.

https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/02/09/fact-sheet-covid-19-public-health-emergency-transition-roadmap.html

11. United States Census Bureau. Household Pulse Survey Technical Documentation. Updated February 17, 2023. Accessed

March 16, 2023, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/technical-documentation.html

12. U.S. Census Bureau. Data from: Measuring Household Experiences during the Coronavirus Pandemic. 2022.

https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html.

13. Rabbani N, Chen JH. National Trends in Pediatric Ambulatory Telehealth Utilization and Follow-Up Care. Telemed J E

Health. Jan 2023;29(1):137-140. doi:10.1089/tmj.2022.0137

14. Ortega P, Shin TM, Martínez GA. Rethinking the Term "Limited English Proficiency" to Improve Language-Appropriate

Healthcare for All. J Immigr Minor Health. Jun 2022;24(3):799-805. doi:10.1007/s10903-021-01257-w

15. Uscher-Pines L, McCullough C, Dworsky MS, et al. Use of Telehealth Across Pediatric Subspecialties Before and During

the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. Mar 1 2022;5(3):e224759. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.4759

16. Lucas JW, Villarroel MA. Telemedicine use among adults: United States, 2021. Vol. no. 445. National Center for Health

Statistics. NCHS Data Brief. October 2022. Accessed January 9, 2023.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db445.htm

17. Villarroel MA, Lucas JW. QuickStats: Percentage of Persons Who Used Telemedicine During the Past 12 Months, by Age

Group — National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2021. Vol. 72.132. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023.

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

16

February 3, 2023. Accessed March 16, 2023.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7205a2.htm#suggestedcitation

18. Lucas JW, Villarroel MA, Cohen R. QuickStats: Percentage of Adults Aged 18–64 Years Who Used Telemedicine in the

Past 12 Months, by Sex and Health Insurance Coverage — National Health Interview Survey, United States 2021. Vol.

72.244. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. March 3, 2023. Accessed March 16, 2023.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7209a5.htm?s_cid=mm7209a5_w

19. Khairat S, Yao Y, Coleman C, McDaniel P, Edson B, Shea CM. Changes in Patient Characteristics and Practice Outcomes of

a Tele-Urgent Care Clinic Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Telehealth Policy Expansions. Perspect Health Inf Manag. Spring

2022;19(Spring):1k.

20. Sun CA, Perrin N, Maruthur N, Renda S, Levin S, Han HR. Predictors of Follow-Up Appointment No-Shows Before and

During COVID Among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Telemed J E Health. Nov 4 2022;doi:10.1089/tmj.2022.0377

21. Cousins MM, Van Til M, Steppe E, et al. Age, race, insurance type, and digital divide index are associated with video visit

completion for patients seen for oncologic care in a large hospital system during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One.

2022;17(11):e0277617. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0277617

22. Lau KHV, Anand P, Ramirez A, Phicil S. Disparities in Telehealth use During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Immigr Minor

Health. Dec 2022;24(6):1590-1593. doi:10.1007/s10903-022-01381-1

23. Ranganathan C, Balaji S. Key Factors Affecting the Adoption of Telemedicine by Ambulatory Clinics: Insights from a

Statewide Survey. Telemed J E Health. Feb 2020;26(2):218-225. doi:10.1089/tmj.2018.0114

24. Chang JE, Lai AY, Gupta A, Nguyen AM, Berry CA, Shelley DR. Rapid Transition to Telehealth and the Digital Divide:

Implications for Primary Care Access and Equity in a Post-COVID Era. Milbank Q. Jun 2021;99(2):340-368.

doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12509

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index. Updated November 16, 2022.

Accessed March 14, 2023, 2023. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html

26. Chen K, Lodaria K, Jackson HB. Patient satisfaction with telehealth versus in-person visits during COVID-19 at a large,

public healthcare system. J Eval Clin Pract. Sep 22 2022;doi:10.1111/jep.13770

27. Hays RD, Skootsky SA. Patient Experience with In-Person and Telehealth Visits Before and During the COVID-19

Pandemic at a Large Integrated Health System in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. Mar 2022;37(4):847-852.

doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07196-4

28. Srinivasulu S, Manze MG, Jones HE. "I totally didn't need to be there in person": New York women's preferences for

telehealth consultations for sexual and reproductive healthcare in primary care. Fam Pract. Sep 19

2022;doi:10.1093/fampra/cmac102

29. Graetz I, Huang J, Muelly ER, Hsueh L, Gopalan A, Reed ME. Video Telehealth Access and Changes in HbA1c Among

People With Diabetes. Am J Prev Med. May 2022;62(5):782-785. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2021.10.012

30. Kummer BR, Agarwal P, Sweetnam C, et al. Trends in the Utilization of Teleneurology and Other Healthcare Resources

Prior to and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in an Urban, Tertiary Health System. Front Neurol. 2022;13:834708.

doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.834708

31. Acoba JD, Yin C, Meno M, et al. Racial Disparities in Patient-Provider Communication During Telehealth Visits Versus

Face-to-face Visits Among Asian and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander Patients With Cancer: Cross-sectional

Analysis. JMIR Cancer. Dec 9 2022;8(4):e37272. doi:10.2196/37272

32. Huang J, Graetz I, Millman A, et al. Primary care telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: patient's choice of video

versus telephone visit. JAMIA Open. Apr 2022;5(1):ooac002. doi:10.1093/jamiaopen/ooac002

33. Knaus ME, Kersey K, Ahmad H, et al. Both sides of the screen: Provider and patient perspective on telemedicine in

pediatric surgery. J Pediatr Surg. Aug 2022;57(8):1614-1621. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2022.03.015

34. Rasmussen B, Perry R, Hickey M, et al. Patient preferences using telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic in four

Victorian tertiary hospital services. Intern Med J. May 2022;52(5):763-769. doi:10.1111/imj.15726

35. Ng BP, Park C, Silverman CL, Eckhoff DO, Guest JC, Díaz DA. Accessibility and utilisation of telehealth services among

older adults during COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Soc Care Community. Sep 2022;30(5):e2657-e2669.

doi:10.1111/hsc.13709

36. Fischer SH, Predmore Z, Roth E, Uscher-Pines L, Baird M, Breslau J. Use Of And Willingness To Use Video Telehealth

Through The COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). Nov 2022;41(11):1645-1651. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00118

37. Odukoya EJ, Andino J, Ng S, Steppe E, Ellimoottil C. Predictors of Video versus Audio-Only Telehealth Use among

Urological Patients. Urol Pract. May 2022;9(3):198-204. doi:10.1097/upj.0000000000000301

38. Webber EC, McMillen BD, Willis DR. Health Care Disparities and Access to Video Visits Before and After the COVID-19

Pandemic: Findings from a Patient Survey in Primary Care. Telemed J E Health. Aug 27 2021;doi:10.1089/tmj.2021.0126

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

17

39. Shee K, Liu AW, Yarbrough C, Branagan L, Pierce L, Odisho AY. Identifying Barriers to Successful Completion of Video

Telemedicine Visits in Urology. Urology. Nov 2022;169:17-22. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.07.054

40. Sachs JW, Graven P, Gold JA, Kassakian SZ. Disparities in telephone and video telehealth engagement during the COVID-

19 pandemic. JAMIA Open. Jul 2021;4(3):ooab056. doi:10.1093/jamiaopen/ooab056

41. Pasquinelli MM, Patel D, Nguyen R, et al. Age-based disparities in telehealth use in an urban, underserved population in

cancer and pulmonary clinics: A need for policy change. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. May 1 2022;34(5):731-737.

doi:10.1097/jxx.0000000000000708

42. Chen J, Li KY, Andino J, et al. Predictors of Audio-Only Versus Video Telehealth Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J

Gen Intern Med. Apr 2022;37(5):1138-1144. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07172-y

43. Lori Uscher-Pines LS. Rethinking The Impact Of Audio-Only Visits On Health Equity. Health Affairs Forefront. DECEMBER

17, 2021 2021;doi:10.1377/forefront.20211215.549778

44. Baughman DJ, Jabbarpour Y, Westfall JM, et al. Comparison of Quality Performance Measures for Patients Receiving In-

Person vs Telemedicine Primary Care in a Large Integrated Health System. JAMA Netw Open. Sep 1 2022;5(9):e2233267.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.33267

45. Gately ME, Quach ED, Shirk SD, Trudeau SA. Understanding Variation in Adoption of Video Telehealth and Implications

for Health Care Systems. Med Res Arch. Jun 1 2022;10(5)doi:10.18103/mra.v10i5.2751

46. Connolly SL, Miller CJ, Gifford AL, Charness ME. Perceptions and Use of Telehealth Among Mental Health, Primary, and

Specialty Care Clinicians During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. Jun 1 2022;5(6):e2216401.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16401

47. Hsueh L, Huang J, Millman AK, et al. Disparities in Use of Video Telemedicine Among Patients With Limited English

Proficiency During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. Nov 1 2021;4(11):e2133129.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.33129

48. Marsh Z, Teegala Y, Cotter V. Improving diabetes care of community-dwelling underserved older adults. J Am Assoc

Nurse Pract. Oct 1 2022;34(10):1156-1166. doi:10.1097/jxx.0000000000000773

49. Mechanic OJ, Lee EM, Sheehan HM, et al. Evaluation of Telehealth Visit Attendance After Implementation of a Patient

Navigator Program. JAMA Netw Open. Dec 1 2022;5(12):e2245615. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.45615

50. O'Shea AMJ, Baum A, Haraldsson B, et al. Association of Adequacy of Broadband Internet Service With Access to Primary

Care in the Veterans Health Administration Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. Oct 3

2022;5(10):e2236524. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.36524

51. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Public Law 117-58 (Rep. DeFazio PA 2021). November 15, 2021. Accessed

October 12, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3684

52. National Telecommunications and Information Administration. NTIA’s Role in Implementing the Broadband Provisions of

the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Accessed October 12, 2022,

https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/news/latest-news/ntias-role-implementing-broadband-provisions-2021-

infrastructure-investment-and

53. National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Grants: Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

Overview. Accessed November 6, 2022, https://www.ntia.doc.gov/category/grants

54. Tang M, Chernew ME, Mehrotra A. How Emerging Telehealth Models Challenge Policymaking. Milbank Q. Sep 28

2022;doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12584

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

18

APPENDIX

Appendix exhibit 1. Table of telehealth utilization percentage (%) from each HPS survey period weeks 28-48 (April

2021 – August 2022)

DATES

Adults

Children

Apr 14 – Apr 26, 2021

26.9

24.1

Apr 28 – May 10, 2021

26.1

23.4

May 12 – May 24, 2021

25.9

23.2

May 26 – Jun 7, 2021

25.3

22.7

Jun 9 – Jun 21, 2021

24.5

22.6

Jun 23 – Jul 5, 2021

24.6

22.1

Jul 21 – Aug 2, 2021

20.6

16.2

Aug 4 – Aug 16, 2021

20.2

15.3

Aug 18 – Aug 30, 2021

20.5

15.8

Sep 1 – Sep 13, 2021

20.6

16.5

Sept 15 – Sep 27, 2021

20.9

16.5

Sep 29 – Oct 11, 2021

20.9

16.8

Dec 1 – Dec 13, 2021

19.7

15.8

Dec 29 – Jan 10, 2022

20.2

16.2

Jan 26 – Feb 7, 2022

22.0

16.4

Mar 2 – Mar 14, 2022

21.2

15.9

Mar 30 – Apr 11, 2022

20.7

15.2

Apr 27 - May 9, 2022

20.5

15.1

Jun 1 - Jun 13, 2022

24.1

16.7

Jun 29 - Jul 11, 2022

24.2

16.0

Jul 27 - Aug 8, 2022

22.8

15.5

April 2023

ISSUE BRIEF

19

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

200 Independence Avenue SW, Mailstop 447D

Washington, D.C. 20201

For more ASPE briefs and other publications, visit:

aspe.hhs.gov/reports

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Euny C. Lee is a Social Science Analyst in the Office of Health Policy at ASPE.

Violanda Grigorescu is a Senior Health Scientist in the Office of Health Policy at ASPE.

Idia Enogieru is an ORISE Fellow in the Office of Health Policy at ASPE.

Scott R. Smith is the Division Director in the Office of Health Policy at ASPE.

Lok Wong Samson is a Health Policy Analyst in the Office of Health Policy at ASPE.

Ann B. Conmy is a Social Science Analyst in the Office of Health Policy at ASPE.

Nancy De Lew is the Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary, Health Policy, at ASPE.

SUGGESTED CITATION

Lee, E.C., Grigorescu, V., Enogieru, I., Smith, S.R., Samson, L.W., Conmy, A., De Lew,

N. Updated National Survey Trends in Telehealth Utilization and Modality: 2021-

2022 (Issue Brief No. HP-2023-09). Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning

and Evaluation, U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. April 2023.

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain

and may be reproduced or copied without permission;

citation as to source, however, is appreciated.

DISCLOSURE

This communication was printed, published, or produced and

disseminated at U.S. taxpayer expense.

___________________________________

Subscribe to ASPE mailing list to receive

email updates on new publications:

https://list.nih.gov/cgi-bin/wa.exe?SUBED1=ASPE-HEALTH-POLICY&A=1

For general questions or general

information about ASPE:

aspe.hhs.gov/about

HP-2023-09