WORLD

DRUG

REPORT

2018

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

CONCLUSIONS AND

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

1

9 789211 483048

ISBN 978-92-1-148304-8

© United Nations, June 2018. All rights reserved worldwide.

ISBN: 978-92-1-148304-8

eISBN: 978-92-1-045058-4

United Nations publication, Sales No. E.18.XI.9

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form

for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from

the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) would appreciate

receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source.

Suggested citation:

World Drug Report 2018 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.18.XI.9).

No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial

purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNODC.

Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the

reproduction, should be addressed to the Research and Trend Analysis Branch of UNODC.

DISCLAIMER

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or

policies of UNODC or contributory organizations, nor does it imply any endorsement.

Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to:

Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

PO Box 500

1400 Vienna

Austria

Tel: (+43) 1 26060 0

Fax: (+43) 1 26060 5827

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018

1

Drug treatment and health services continue to fall

short: the number of people suffering from drug use

disorders who are receiving treatment has remained

low, just one in six. Some 450,000 people died in

2015 as a result of drug use. Of those deaths,

167,750 were a direct result of drug use disorders,

in most cases involving opioids.

These threats to health and well-being, as well as to

security, safety and sustainable development,

demand an urgent response.

The outcome document of the special session of the

General Assembly on the world drug problem held

in 2016 contains more than 100 recommendations

on promoting evidence-based prevention, care and

other measures to address both supply and demand.

We need to do more to advance this consensus,

increasing support to countries that need it most

and improving international cooperation and law

enforcement capacities to dismantle organized crimi-

nal groups and stop drug trafficking.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

(UNODC) continues to work closely with its

United Nations partners to assist countries in imple-

menting the recommendations contained in the

outcome document of the special session, in line

with the international drug control conventions,

human rights instruments and the 2030 Agenda for

Sustainable Development.

In close cooperation with the World Health Organi-

zation, we are supporting the implementation of

the International Standards on Drug Use Prevention

and the international standards for the treatment of

drug use disorders, as well as the guidelines on treat-

ment and care for people with drug use disorders in

contact with the criminal justice system.

The World Drug Report 2018 highlights the impor-

tance of gender- and age-sensitive drug policies,

exploring the particular needs and challenges of

women and young people. Moreover, it looks into

Both the range of drugs and drug markets are

expanding and diversifying as never before. The

findings of this year’s World Drug Report make clear

that the international community needs to step up

its responses to cope with these challenges.

We are facing a potential supply-driven expansion

of drug markets, with production of opium and

manufacture of cocaine at the highest levels ever

recorded. Markets for cocaine and methampheta-

mine are extending beyond their usual regions and,

while drug trafficking online using the darknet con-

tinues to represent only a fraction of drug trafficking

as a whole, it continues to grow rapidly, despite

successes in shutting down popular trading

platforms.

Non-medical use of prescription drugs has reached

epidemic proportions in parts of the world. The

opioid crisis in North America is rightly getting

attention, and the international community has

taken action. In March 2018, the Commission on

Narcotic Drugs scheduled six analogues of fentanyl,

including carfentanil, which are contributing to the

deadly toll. This builds on the decision by the

Commission at its sixtieth session, in 2017, to place

two precursor chemicals used in the manufacture

of fentanyl and an analogue under international

control.

However, as this World Drug Report shows, the prob-

lems go far beyond the headlines. We need to raise

the alarm about addiction to tramadol, rates of

which are soaring in parts of Africa. Non-medical

use of this opioid painkiller, which is not under

international control, is also expanding in Asia. The

impact on vulnerable populations is cause for seri-

ous concern, putting pressure on already strained

health-care systems.

At the same time, more new psychoactive substances

are being synthesized and more are available than

ever, with increasing reports of associated harm and

fatalities.

PREFACE

2

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

Next year, the Commission on Narcotic Drugs will

host a high-level ministerial segment on the 2019

target date of the 2009 Political Declaration and

Plan of Action on International Cooperation

towards an Integrated and Balanced Strategy to

Counter the World Drug Problem. Preparations are

under way. I urge the international community to

take this opportunity to reinforce cooperation and

agree upon effective solutions.

Yury Fedotov

Executive Director

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

increased drug use among older people, a develop-

ment requiring specific treatment and care.

UNODC is also working on the ground to promote

balanced, comprehensive approaches. The Office

has further enhanced its integrated support to

Afghanistan and neighbouring regions to tackle

record levels of opiate production and related secu-

rity risks. We are supporting the Government of

Colombia and the peace process with the Revolu-

tionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) through

alternative development to provide licit livelihoods

free from coca cultivation.

Furthermore, our Office continues to support efforts

to improve the availability of controlled substances

for medical and scientific purposes, while prevent-

ing misuse and diversion – a critical challenge if we

want to help countries in Africa and other regions

come to grips with the tramadol crisis.

3

CONTENTS

PREFACE ...................................................................................................... 1

EXPLANATORY NOTES .................................................................................5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................7

Latest trends .....................................................................................................................................8

Market developments .....................................................................................................................10

Vulnerabilities of particular groups .................................................................................................15

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS .............................................. 23

GLOSSARY ................................................................................................. 29

REGIONAL GROUPINGS ............................................................................. 31

BOOKLET 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY — CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

BOOKLET 2

GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF DRUG DEMAND AND SUPPLY

Latest trends, cross-cutting issues

BOOKLET 3

ANALYSIS OF DRUG MARKETS

Opioids, cocaine, cannabis, synthetic drugs

BOOKLET 4

DRUGS AND AGE

Drugs and associated issues among young people and older people

BOOKLET 5

WOMEN AND DRUGS

Drug use, drug supply and their consequences

4

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

Acknowledgements

The World Drug Report 2018 was prepared by the Research and Trend Analysis Branch, Division for

Policy Analysis and Public Affairs, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, under the supervision

of Jean-Luc Lemahieu, Director of the Division, and Angela Me, Chief of the Research and Trend

Analysis Branch.

General coordination and content overview

Chloé Carpentier

Angela Me

Analysis and drafting

Pablo Carvacho

Conor Crean

Philip Davis

Catalina Droppelmann

Diana Fishbein

Natascha Eichinger

Susan Ifeagwu

Theodore Leggett

Sabrina Levissianos

Kamran Niaz

José Luis Pardo Veiras

Thomas Pietschmann

Fifa Rahman

Martin Raithelhuber

Alejandra Sánchez Inzunza

Claudia Stoicescu

Justice Tettey

Amalia Valdés

Data management and estimates production

Enrico Bisogno

Coen Bussink

Hernan Epstein

Jesus Maria Garcia Calleja (WHO)

Riku Lehtovuori

Tun Nay Soe

Andrea Oterová

Umidjon Rakhmonberdiev

Ali Saadeddin

Keith Sabin (UNAIDS)

Antoine Vella

Editing

Joseph Boyle

Jonathan Gibbons

Graphic design and production

Anja Korenblik

Suzanne Kunnen

Kristina Kuttnig

Coordination

Francesca Massanello

Data support

Diana Camerini

Chung Kai Chan

Sarika Dewan

Smriti Ganapathi

Administrative support

Anja Held

Iulia Lazar

Paul Griffiths

Marya Hynes

Vicknasingam B. Kasinather

Letizia Paoli

Charles Parry

Peter Reuter

Francisco Thoumi

Alison Ritter

In memoriam

Brice de Ruyver

Review and comments

The World Drug Report 2018 benefited from the expertise of and invaluable contributions from

UNODC colleagues in all divisions.

The Research and Trend Analysis Branch acknowledges the invaluable contributions and advice

provided by the World Drug Report Scientific Advisory Committee:

The research and production of the joint UNODC/UNAIDS/WHO/World Bank estimates of

the number of people who inject drugs were partly funded by the HIV/AIDS Section of the Drug

Prevention and Health Branch of the Division for Operations of UNODC.

The research for booklets 4 and 5 was made possible by the generous contribution of Germany

(German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ)).

5

EXPLANATORY NOTES

The boundaries and names shown and the designa-

tions used on maps do not imply official endorsement

or acceptance by the United Nations. A dotted line

represents approximately the line of control in

Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Paki-

stan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has

not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Disputed

boundaries (China/India) are represented by cross-

hatch owing to the difficulty of showing sufficient

detail.

The designations employed and the presentation of

the material in the World Drug Report do not imply

the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the

part of the Secretariat of the United Nations con-

cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city

or area, or of its authorities or concerning the delimi-

tation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Countries and areas are referred to by the names

that were in official use at the time the relevant data

were collected.

All references to Kosovo in the World Drug Report,

if any, should be understood to be in compliance

with Security Council resolution 1244 (1999).

Since there is some scientific and legal ambiguity

about the distinctions between “drug use”, “drug

misuse” and “drug abuse”, the neutral terms “drug

use” and “drug consumption” are used in the World

Drug Report. The term “misuse” is used only to

denote the non-medical use of prescription drugs.

All uses of the word “drug” in the World Drug Report

refer to substances controlled under the international

drug control conventions.

All analysis contained in the World Drug Report is

based on the official data submitted by Member

States to the United Nations Office on Drugs and

Crime through the annual report questionnaire

unless indicated otherwise.

The data on population used in the World Drug

Report are taken from: World Population Prospects:

The 2017 Revision (United Nations, Department of

Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division).

References to dollars ($) are to United States dollars,

unless otherwise stated.

References to tons are to metric tons, unless other-

wise stated.

The following abbreviations have been used in the

present booklet:

GHB gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid

ha hectares

LSD Lysergic acid diethylamide

MDMA 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine

NPS new psychoactive substances

PWID people who inject drugs

UNODC

United Nations Office on Drugs

and Crime

WHO World Health Organization

7

Opioids continued to cause the most harm, account-

ing for 76 per cent of deaths where drug use disorders

were implicated. PWID — some 10.6 million world-

wide in 2016 — endure the greatest health risks. More

than half of them live with hepatitis C, and one in

eight live with HIV.

The headline figures for drug users have changed

little in recent years, but this stability masks the

striking ongoing changes in drug markets. Drugs

such as heroin and cocaine that have been available

for a long time increasingly coexist with NPS and

there has been an increase in the non-medical use

of prescription drugs (either diverted from licit chan-

nels or illicitly manufactured).The use of substances

of unclear origin supplied through illicit channels

that are sold as purported medicines but are destined

for non-medical use is also on the increase. The

range of substances and combinations available to

users has never been wider.

About 275 million people worldwide, which is

roughly 5.6 per cent of the global population aged

15–64 years, used drugs at least once during 2016.

Some 31 million of people who use drugs suffer from

drug use disorders, meaning that their drug use is

harmful to the point where they may need treatment.

Initial estimations suggest that, globally, 13.8 million

young people aged 15–16 years used cannabis in the

past year, equivalent to a rate of 5.6 per cent.

Roughly 450,000 people died as a result of drug use

in 2015, according to WHO. Of those deaths,

167,750 were directly associated with drug use dis-

orders (mainly overdoses). The rest were indirectly

attributable to drug use and included deaths related

to HIV and hepatitis C acquired through unsafe

injecting practices.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

cannabis opioids

opiates

Number of past-year users in 2016

cocaine

amphetamines and

prescription stimulants

“ecstasy”

192

million

34

million

34

million

21

million

18

million

19

million

8

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

seized globally reached a record high of 91 tons in

2016. Most opiates were seized near the manufac-

turing hubs in Afghanistan.

A notable increase has been seen in cocaine

production

Global cocaine manufacture in 2016 reached its

highest level ever: an estimated 1,410 tons. After

falling during the period 2005–2013, global cocaine

manufacture rose by 56 per cent during the period

2013–2016. The increase from 2015 to 2016 was

25 per cent.

LATEST TRENDS

Record levels of plant-based drug

production have been reached

Afghan opium poppy cultivation drives

record opiate production

Total global opium production jumped by 65 per

cent from 2016 to 2017, to 10,500 tons, easily the

highest estimate recorded by UNODC since it

started monitoring global opium production at the

beginning of the twenty-first century.

A marked increase in opium poppy cultivation and

a gradual increase in opium poppy yields in

Afghanistan resulted in opium production in the

country reaching 9,000 tons in 2017, an increase

of 87 per cent from the previous year. Among the

drivers of that increase were political instability, lack

of government control and reduced economic

opportunities for rural communities, which may

have left the rural population vulnerable to the

influence of groups involved in the drug trade.

The surge in opium poppy cultivation in Afghani-

stan meant that the total area under opium poppy

cultivation worldwide increased by 37 per cent from

2016 to 2017, to almost 420,000 ha. More than 75

per cent of that area is in Afghanistan.

Overall seizures of opiates rose by almost 50 per

cent from 2015 to 2016. The quantity of heroin

Global coca bush cultivation and cocaine

manufacture, 2006–2016

Sources: UNODC, coca cultivation surveys in Bolivia (Plurina-

tional State of), Colombia and Peru, 2014 and previous years.

Opium poppy cultivation and production of opium, 2006-2017

a

Sources: UNODC, calculations are based on UNODC illicit crop monitoring surveys and the responses to the annual report

questionnaire.

a

Data for 2017 are still preliminary.

0

40,000

80,000

120,000

160,000

200,000

240,000

280,000

320,000

360,000

400,000

440,000

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

10,000

11,000

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

Culvaon (hectares)

Producon (tons)

Total area under culvaon

Producon in Afghanistan

Producon in Myanmar

Producon in the

Lao People's Democrac Republic

Producon in Mexico

Producon in other countries

0

300

600

900

1,200

1,500

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

Potential manufacture of cocaine in tons

(at 100 per cent purity)

Hectares under coca cultivation

Bolivia (Plurinational State of) (ha)

Peru (ha)

Colo mbia (ha)

Global cocaine manufacture ('new' conversion ratio)

9

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Asia, which had previously accounted for more than

half of global seizures, reported just 7 per cent of

the global total in 2016.

The rise in seizures of pharmaceutical opioids in

Africa is mostly due to the worldwide popularity of

tramadol, an opioid used to treat moderate and

moderate-to-severe pain that is widely trafficked for

non-medical use in the region. Tramadol is smug-

gled to various markets in West and Central Africa

and North Africa, from where some of it is trafficked

onwards to countries in the Near and Middle East.

Countries in those subregions have reported the

rapid expansion of the non-medical use of tramadol,

in particular among some vulnerable populations.

The drug is not yet under international control and

is perceived by recreational users as a way of boost-

ing energy and improving mood. However, tramadol

can produce physical dependence, with WHO stud-

ies showing that this dependence may occur when

it is used daily for more than a few weeks.

While some tramadol is diverted from licit channels,

most of the tramadol seized worldwide in the period

2012–2016 appears to have originated in clandes-

tine laboratories in Asia.

Non-medical use of pharmaceutical

opioids reaches epidemic proportions in

North America

In 2015 and 2016, for the first time in half a cen-

tury, life expectancy in the United States of America

Most of the world’s cocaine comes from Colombia,

which boosted its manufacture by more than one

third from 2015 to 2016, to some 866 tons. The

total area under coca bush cultivation worldwide in

2016 was 213,000 ha, almost 69 per cent of which

was in Colombia.

The dramatic resurgence of coca bush cultivation

in Colombia — which had almost halved from 2000

to 2013 — came about for a number of reasons

related to market dynamics, the strategies of traf-

ficking organizations and expectations in some

communities of receiving compensation for replac-

ing coca bush cultivation, as well as a reduction in

alternative development interventions and in eradi-

cation. In 2006, more than 213,000 ha were

eradicated. Ten years later, the figure was less than

18,000 ha.

The result has been a perceived decrease in the risk

of coca bush cultivation and a dramatic scaling-up

of manufacture. Colombia has seen massive rises in

both the number of cocaine laboratories dismantled

and the amount of cocaine seized.

Non-medical use of prescription

drugs is becoming a major threat

around the world

The non-medical use of pharmaceutical opioids is

of increasing concern for both law enforcement

authorities and public health professionals. Differ-

ent pharmaceutical opioids are misused in different

regions. In North America, illicitly sourced fentanyl,

mixed with heroin or other drugs, is driving the

unprecedented number of overdose deaths. In

Europe, the main opioid of concern remains heroin,

but the non-medical use of methadone, buprenor-

phine and fentanyl has also been reported. In

countries in West and North Africa and the Near

and Middle East, the non-medical use of tramadol,

a pharmaceutical opioid that is not under interna-

tional control, is emerging as a substance of

concern.

Non-medical use of and trafficking in

tramadol are becoming the main drug

threat in parts of Africa

The focus for global seizures of pharmaceutical opi-

oids is now firmly on countries in West and Central

Africa and North Africa, which accounted for 87

per cent of the global total in 2016. Countries in

n

o

n

-

m

e

d

i

c

a

l

u

s

e

o

f

p

r

e

s

c

r

i

p

t

i

o

n

d

r

u

g

s

N

o

r

t

h

A

m

e

r

i

c

a

A

f

r

i

c

a

a

n

d

N

e

a

r

a

n

d

M

i

d

d

l

e

E

a

s

t

tramadol

fentanyl and

its analogues

Fast emerging public health

threats

6

0

c

o

u

n

t

r

i

e

s

benzodiazepines

10

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

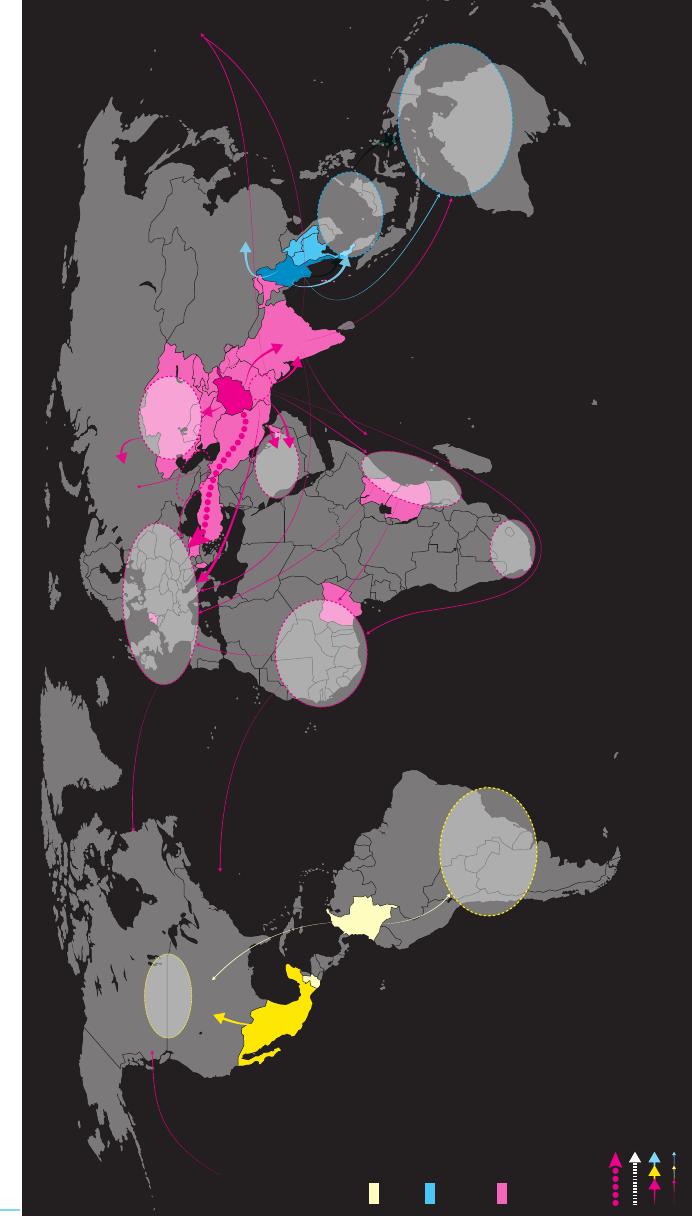

Main heroin trafficking flows, 2012–2016

Sources: UNODC, responses to the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database.

Notes: The size of the trafficking flow lines is based on the amount of heroin seized in a subregion and the number of mentions of countries from where the heroin has departed (including reports of

"origin" and "transit") to a specific subregion over the period 2012–2016. A darker shade indicates that the country represents more than 50 per cent of heroin production in the region. The trafficking

flows are determined on the basis of country of origin/departure, transit and destination of seized drugs as reported by Member States in the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure

database: as such, they need to be considered as broadly indicative of existing trafficking routes while several secondary flows may not be reflected. Flow arrows represent the direction of trafficking:

origins of the arrows indicate either the area of manufacture or the one of last provenance, end points of arrows indicate either the area of consumption or the one of next destination of trafficking.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately

the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the

Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern

Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

Lorem ipsum

Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database.

Notes: The size of the trafficking flow lines is based on the amount of heroin seized in a subregion and the number of mentions of countries from where the heroin has departed (including reports of ‘origin’ and transit”) to a specific subregion over the 2012-2016 period. A darker shade indicates that the

country represents more than 50 percent of heroin production in the region. The trafficking flows are determined on the basis of country of origin/departure, transit and destination of seized drugs as reported by Member States in the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database: as

such, they need to be considered as broadly indicative of existing trafficking routes while several secondary flows may not be reflected. Flow arrows represent the direction of trafficking: origins of the arrows indicate either the area of manufacture or the one of last provenance, end points of arrows indicate

either the area of consumption or the one of next destination of trafficking.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu

and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning

sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

Most frequently mentioned

provenance/transit countries of seized

opiates produced in Latin America

Most frequently mentioned

provenance/transit countries of seized

opiates produced in Myanmar/Lao

People’s Democratic Republic

Most frequently mentioned

provenance/transit countries of seized

opiates produced in Afghanistan

Global heroin trafficking flows by size of

flows estimated on the basis of reported

seizures, 2012-2016:

CENTRAL

ASIA

SOUTH-EAST

ASIA

WESTERN, CENTRAL AND

SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE

GULF AREA

&

MIDDLE EAST

SOUTH

AMERICA

WEST

AFRICA

EAST

AFRICA

OCEANIA

SOUTHERN

AFRICA

Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database.

Notes: The size of the trafficking flow lines is based on the amount of heroin seized in a subregion and the number of mentions of countries from where the heroin has departed (including reports of ‘origin’ and transit”) to a specific subregion over the 2012-2016 period. A darker shade indicates that the

country represents more than 50 percent of heroin production in the region. The trafficking flows are determined on the basis of country of origin/departure, transit and destination of seized drugs as reported by Member States in the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database: as

such, they need to be considered as broadly indicative of existing trafficking routes while several secondary flows may not be reflected. Flow arrows represent the direction of trafficking: origins of the arrows indicate either the area of manufacture or the one of last provenance, end points of arrows indicate

either the area of consumption or the one of next destination of trafficking.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu

and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning

sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

Most frequently mentioned

provenance/transit countries of seized

opiates produced in Latin America

Most frequently mentioned

provenance/transit countries of seized

opiates produced in Myanmar/Lao

People’s Democratic Republic

Most frequently mentioned

provenance/transit countries of seized

opiates produced in Afghanistan

PAKISTAN

AFGHANISTAN

ISLAMIC

REPUBLIC

OF IRAN

TURKEY

MYANMAR

CHINA

RUSSIAN

FEDERATION

MEXICO

PAKISTAN,

INDIA

COLOMBIA

UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA

CANADA

CANADA

LAO PDR

INDIA

CAUCASUS

TANZANIA

(UNITED

REPUBLIC OF)

GUATEMALA

NIGERIA

KENYA

NETHERLANDS

THAILAND

KAZAKHSTAN

UZBEKISTAN

TURKMENISTAN

KYRGYZSTAN

TAJIKISTAN

BULGARIA

ALBANIA

NORTH

AMERICA

11

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A market for non-controlled benzodiazepine-type

substances, used alone or in combination with con-

trolled benzodiazepines, is emerging in some

Western countries. These substances are marketed

legally as tranquillizers and are sold under names

such as “legal benzodiazepines” or “designer benzo-

diazepines”. In specific cases, a large proportion of

drug-related deaths is related to benzodiazepine-type

NPS.

Kratom, a plant-based substance

used as traditional medicine in some

parts of Asia, is emerging as a popular

plant-based new psychoactive

substance

Kratom products are derived from the leaf of the

kratom tree, which is used in South-East Asia as a

traditional remedy for minor ailments and for non-

medical purposes. Few countries have placed kratom

under national legal control, making it relatively

easy to buy.

There are now numerous products around the world

advertised as containing kratom, which usually come

mixed with other substances. People who use opi-

oids in the United States have reported using kratom

products for the self-management of withdrawal

symptoms. Some 500 tons of kratom were inter-

cepted during 2016, triple the amount of the

previous year, suggesting a boom in its popularity.

MARKET DEVELOPMENTS

Cannabis remains the world’s most

commonly used drug

Cannabis was the most commonly used drug in 2016,

with 192 million people using it at least once in the

past year. The global number of cannabis users con-

tinues to rise and appears to have increased by roughly

16 per cent in the decade ending 2016, which is in

line with the increase in the world population.

The quantities of cannabis herb seized globally

declined by 27 per cent, to 4,386 tons, in 2016. The

decline was particularly marked in North America,

where the availability of medical cannabis in many

jusrisdictions and the legalization of cannabis for rec-

reational use in several states of the United States may

have played a role.

declined for two consecutive years. A key factor was

the increase in unintentional injuries, which includes

overdose deaths.

In 2016, 63,632 people died from a drug overdose

in the United States, the highest number on record

and a 21 per cent increase from the previous year.

This was largely due to a rise in deaths associated

with pharmaceutical opioids, including fentanyl and

fentanyl analogues. This group of opioids, exclud-

ing methadone, was implicated in 19,413 deaths in

the country, more than double the number in 2015.

Evidence suggests that Canada is also affected, with

a large number of overdose deaths involving fentanyl

and its analogues in 2016.

Illicit fentanyl and its analogues are reportedly mixed

into heroin and other drugs, such as cocaine and

MDMA, or “ecstasy”, or sold as counterfeit prescrip-

tion opioids. Users are often unaware of the contents

of the substance they are taking, which inevitably

leads to a great number of fatal overdoses.

Outside North America, the impact of fentanyl and

its analogues is relatively low. In Europe, for exam-

ple, opiates such as heroin and morphine continue

to predominate, although some deaths involving

fentanyl analogues have started to emerge in the

region. A notable exception is Estonia, where fen-

tanyl has long been regarded as the most frequently

misused opioid. The downward trend in opiate use

since the late 1990s observed in Western and Cen-

tral Europe appears to have come to an end in 2013.

In that subregion as a whole, 12 countries reported

stable trends in heroin use in 2016, two reported a

decline and three an increase.

Misuse of sedatives and stimulants brings

growing risks

Many countries are now reporting the

non-medical use of benzodiazepines as

one of the main drug use problems

Non-medical use of the common sedative/hypnotic

benzodiazepines and similar substances is now one

of the main drug use problems in some 60

countries.

The misuse of benzodiazepines carries serious risks,

not least an increased risk of overdose when used in

combination with heroin. Benzodiazepines are fre-

quently reported in fatal overdose cases involving

opioids such as methadone.

12

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

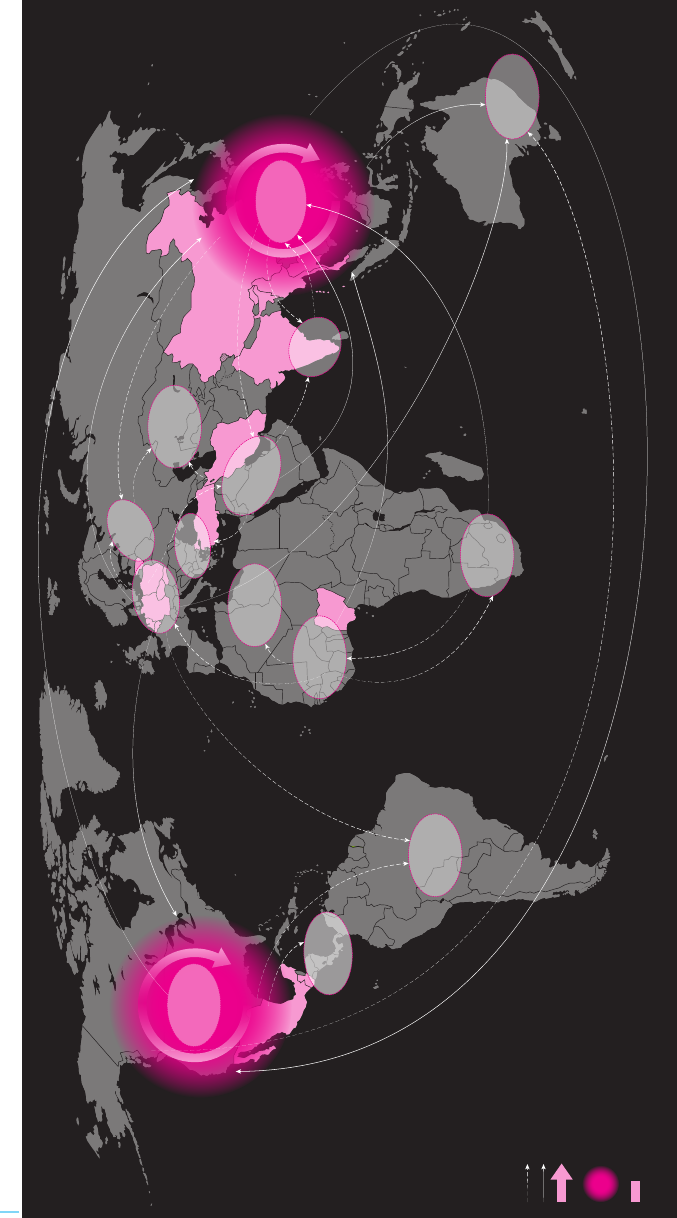

Main cocaine trafficking flows, 2012–2016

Sources: UNODC, responses to the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database.

Notes: The size of the trafficking flow lines is based on the amount of cocaine seized in a subregion and the number of mentions of countries from where the cocaine has departed (including reports of

"origin" and "transit") to a specific subregion over the period 2012–2016. The trafficking flows are determined on the basis of country of origin/departure, transit and destination of seized drugs as

reported by Member States in the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database: as such, they need to be considered as broadly indicative of existing trafficking routes while several

secondary flows may not be reflected. Flow arrows represent the direction of trafficking: origins of the arrows indicate either the area of manufacture or the one of last provenance, end points of

arrows indicate either the area of consumption or the one of next destination of trafficking.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately

the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the

Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern

Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

Most frequently mentioned countries

of provenance as reported by countries

where cocaine seizures took place

Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database.

Notes: The size of the trafficking flow lines is based on the amount of cocaine seized in a subregion and the number of mentions of countries from where the cocaine has departed (including reports of ‘origin’ and transit”) to a specific subregion over the 2012-2016 period. The trafficking flows are determined on the basis

of country of origin/departure, transit and destination of seized drugs as reported by Member States in the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database: as such, they need to be considered as broadly indicative of existing trafficking routes while several secondary flows may not be reflected. Flow arrows

represent the direction of trafficking: origins of the arrows indicate either the area of manufacture or the one of last provenance, end points of arrows indicate either the area of consumption or the one of next destination of trafficking.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has

not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands

(Malvinas).

Global cocaine trafficking flows by size of

flows estimated on the basis of reported

seizures, 2012-2016:

NORTH

AMERICA

SOUTH

AMERICA

WESTERN

AND CENTRAL

EUROPE

WEST

AFRICA

CENTRAL

AMERICA

CARIBBEAN

SOUTH-EAST

ASIA

SOUTH

ASIA

NEAR AND

MIDDLE EAST

SOUTHERN

AFRICA

EAST AND

SOUTH-EAST

ASIA

OCEANIA

SOUTH-EAST ASIA,

OCEANIA

OCEANIA

SOUTH-EAST

EUROPE

ANDEAN

COUNTRIES

SOUTH

AFRICA

MEXICO

BOLIVIA

(PLUR STATE OF)

BRAZIL

PERU

COLOMBIA

VENEZUELA

(BOL. REP. OF)

CHILE

PARAGUAY

SPAIN

ECUADOR

PORTUGAL

ARGENTINA

NIGERIA

NETHERLANDS

UNITED

ARAB

EMIRATES

PANAMA

GUATEMALA

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

TRINIDAD AND

TOBAGO

BELGIUM

HONDURAS

French Guiana

(FRANCE)

13

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

for non-medical use through pharmacies began, as

did the sale of the drug through a network of 16

pharmacies.

Effect of the crackdown on darknet

drug dealers is not yet clear

In July 2017, police forces from several countries

worked together to take down the largest drug-trad-

ing platform on the darknet, the part of the “deep

web” containing information that is only accessible

using special web browsers. Before it was closed,

AlphaBay had featured more than 250,000 listings

for illegal drugs and chemicals. It had had over

200,000 users and 40,000 vendors during its exist-

ence. The authorities also succeeded in taking down

the trading platform Hansa, described as the third

largest criminal marketplace on the dark web.

It is not yet clear what effect the closures will have.

According to an online survey in January 2018, 15

per cent of those who had used darknet sites for

purchasing drugs said that they had used such mar-

kets less frequently since the closures, and 9 per cent

said they had completely stopped. However, more

than half did not consider themselves to have been

affected by the closures.

Although the scale of drug trafficking on the dark-

net remains limited, it has shown signs of rapid

growth. Authorities in Europe estimated that drug

sales on the darknet from 22 November 2011 to 16

February 2015 amounted to roughly $44 million

per year. However, a later study estimated that, in

early 2016, drug sales on the darknet were between

$14 million and $25 million per month, equivalent

to between $170 million and $300 million per year.

Africa and Asia have emerged as

cocaine trafficking and consumption

hubs

Most indicators from North America suggest that

cocaine use rose between 2013 and 2016. In 2013,

there were fewer than 5,000 cocaine-related deaths

in the United States, but by 2016 the figure was

more than 10,000. Although many of those deaths

also involved synthetic opioids and cannot be attrib-

uted exclusively to higher levels of cocaine

consumption, the increase is nonetheless a strong

indicator of increasing levels of harmful cocaine use.

Too early to determine the impact

of latest developments in recreational

cannabis regulations

Since 2017, the non-medical use of cannabis has

been allowed in eight state-level jurisdictions in the

United States, in addition to the District of Colum-

bia. Colorado was one of the first states to adopt

measures to allow the non-medical use of cannabis

in the United States. Cannabis use has increased

significantly among the population aged 18–25 years

and older in Colorado since legalization, while it

has remained relatively stable among those aged

17–18 years. However, there has been a significant

increase in cannabis-related emergency room visits,

hospital admissions and traffic deaths, as well as

instances of people driving under the influence of

cannabis in the State of Colorado.

In Uruguay, up to 480 grams per person per year of

cannabis can now be obtained through pharmacies,

cannabis clubs or individual cultivation. Cannabis

regulation in the country allows for the availability

of cannabis products with a tetrahydrocannabinol

content of up to 9 per cent and a minimum can-

nabidiol content of 3 per cent. In mid-2017, the

registration of those who choose to obtain cannabis

1,129

tons

158

tons

70

tons

22

tons

87

tons

156

tons

658

tons

6,313

tons

14

tons

opium

heroin and morphine pharmaceutical opioids

cocainecannabis (herb/resin)

“ecstasy”amphetamine

methamphetamine

synthetic NPS

Quantities of drugs

seized in 2016

14

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

Main methamphetamine trafficking flows, 2012–2016

Sources: UNODC, responses to the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database.

Notes: The size of the trafficking flow lines is based on the amount of methamphetamine seized in a subregion and the number of mentions of countries from where the methamphetamine has

departed (including reports of "origin" and "transit") to a specific subregion over the period 2012–2016. The trafficking flows are determined on the basis of country of origin/departure, transit and

destination of seized drugs as reported by Member States in the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database: as such, they need to be considered as broadly indicative of existing

trafficking routes while several secondary flows may not be reflected. Flow arrows represent the direction of trafficking: origins of the arrows indicate either the area of manufacture or the one of last

provenance, end points of arrows indicate either the area of consumption or the one of next destination of trafficking.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately

the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the

Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ire-

land concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

Frequently mentioned countries of provenance as reported

by countries where methamphetamine seizures took place

Principal flows

Main markets

NORTH

AMERICA

EASTERN

EUROPE

SOUTH-EAST

EUROPE

WEST

AFRICA

CENTRAL

AMERICA

SOUTH

ASIA

NEAR AND

MIDDLE EAST

SOUTHERN

AFRICA

EAST AND

SOUTH-EAST

ASIA

AUSTRALIA

AND

NEW ZEALAND

Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database.

Notes: The size of the trafficking flow lines is based on the amount of methamphetamine seized in a subregion and the number of mentions of countries from where the methamphetamine has departed (including reports of ‘origin’ and transit”) to a specific subregion over the 2012-2016 period.

The trafficking flows are determined on the basis of country of origin/departure, transit and destination of seized drugs as reported by Member States in the annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database: as such, they need to be considered as broadly indicative of existing trafficking routes while several secondary

flows may not be reflected. Flow arrows represent the direction of trafficking: origins of the arrows indicate either the area of manufacture or the one of last provenance, end points of arrows indicate either the area of consumption or the one of next destination of trafficking.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet

been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

NORTH

AFRICA

CENTRAL ASIA

AND

TRANSCAUCASIA

WESTERN

AND CENTRAL

EUROPE

SOUTH

AMERICA

CARIBBEAN

ISLAMIC

REPUBLIC

OF IRAN

TURKEY

CHINA

MEXICO

NIGERIA

NETHERLANDS

GUATEMALA

BELGIUM

INDIA

THAILAND

MYANMAR

POLAND

GERMANY

CZECHIA

LITHUANIA

Global methamphetamine

trafficking flows by size of

flows estimated on the basis

of reported seizures,

2012-2016:

15

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

market for methamphetamine in East and South-

East Asia and Oceania, where the use of crystalline

methamphetamine in particular has become a key

concern.

For many years, amphetamine dominated synthetic

drug markets in the Near and Middle East and West-

ern and Central Europe, but recent increases in the

quantities seized in North Africa and North America

point to growing activity in other subregions. While

the reasons for the spike in the quantity of ampheta-

mine seized in North Africa are not entirely clear,

it may be related to the trafficking of amphetamine

destined for the large market in the neighbouring

subregion of the Near and Middle East.

Growth in the complexity and diver-

sity of the synthetic drug market is

leading to an increase in related harm

In recent years, hundreds of NPS have been

synthesized and added to the established synthetic

drug market for amphetamine-type substances.

Grouped according to their main pharmacological

effect, the largest portion of NPS reported since

UNODC began monitoring are stimulants, followed

The biggest growth in cocaine seizures in 2016 took

place in Asia and Africa, reflecting the ongoing

spread of cocaine trafficking and consumption to

emerging markets. Although starting from a much

lower level than North America, the quantity of

cocaine seized in Asia tripled from 2015 to 2016;

in South Asia, it increased tenfold. The quantity of

cocaine seized in Africa doubled in 2016, with coun-

tries in North Africa seeing a sixfold increase and

accounting for 69 per cent of all the cocaine seized

in the region in 2016. This was in contrast to previ

-

ous years, when cocaine tended to be seized mainly

in West and Central Africa.

Trafficking in and use of synthetic

drugs expands beyond established

markets, and major markets for

methamphetamine continue to grow

East and South-East Asia and North America remain

the two main subregions for methamphetamine traf-

ficking worldwide. In North America, the availability

of methamphetamine was reported to have increased

between 2013 and 2016, and, in 2016, the drug

was reported to be the second greatest drug threat

in the United States, after heroin.

Based on qualitative assessments, increases in

consumption and manufacturing capacity and

increases in the amounts seized point to a growing

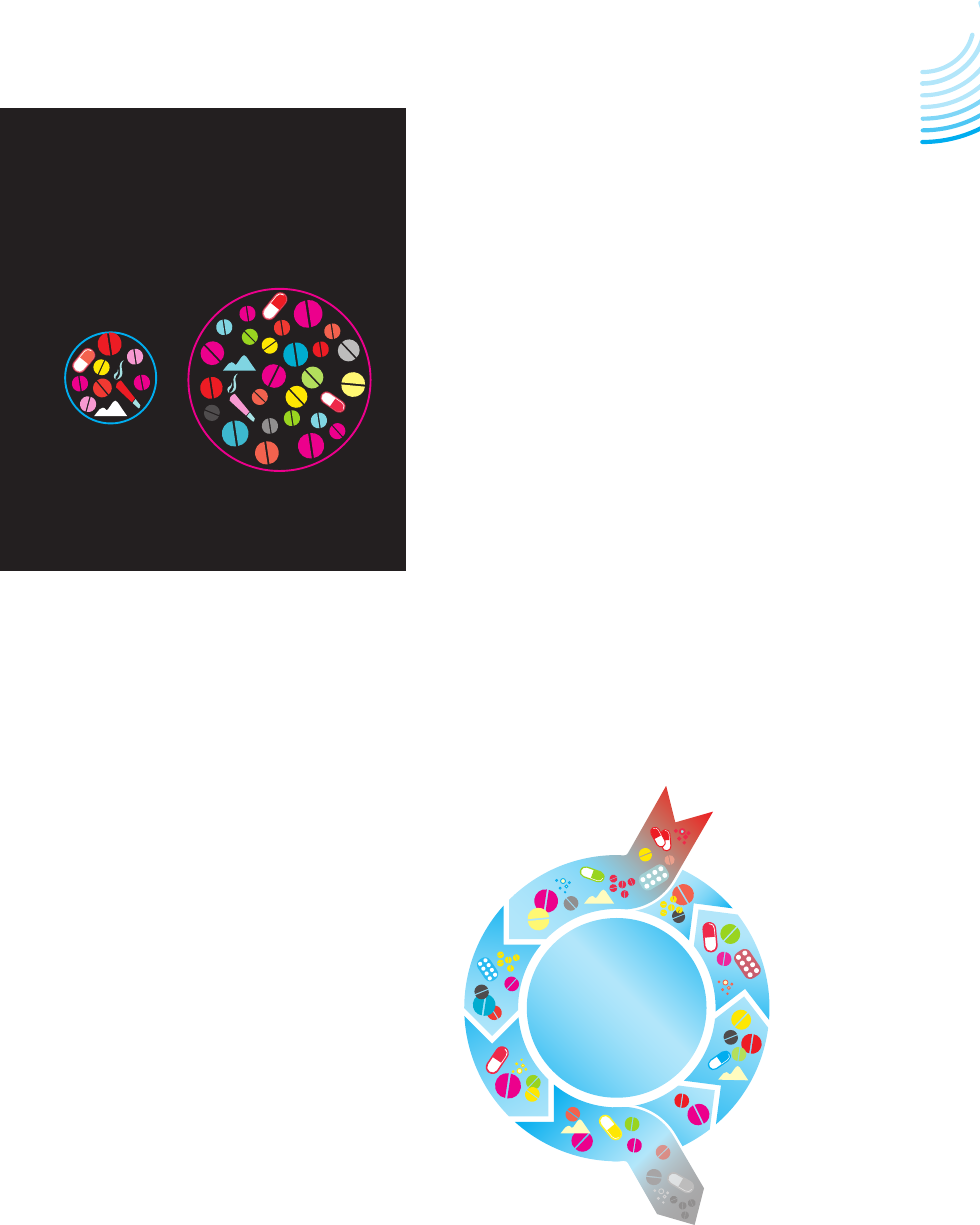

Range of

new psychoactive substances

continues to grow

reported in

2012

reported in

2016

2

6

9

N

P

S

4

7

9

N

P

S

The market

for NPS is in

a constant state

of flux

60 NPS

have disappeared from

the market since 2013

479 different

NPS on the

market in 2016

72 newly

emerging NPS

in 2016

16

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

programmes. There was no information on the avail-

ability of antiretroviral therapy for 162 countries.

Drug use and the associated harm are

highest among young people

Surveys on drug use among the general population

show that the extent of drug use among young

people remains higher than that among older people,

although there are some exceptions associated with

the traditional use of drugs such as opium or khat.

Most research suggests that early (12–14 years old)

to late (15–17 years old) adolescence is a critical risk

period for the initiation of substance use and that

substance use may peak among young people aged

18–25 years.

Cannabis is a common drug of choice

for young people

There is evidence from Western countries that the

perceived easy availability of cannabis, coupled with

by cannabinoid receptor agonists and classic

hallucinogens.

A total of 803 NPS were reported in the period

2009–2017. However, while the global NPS market

remains widely diversified, with the exception of a

few substances, NPS do not seem to have established

themselves on drug markets or replaced traditional

drugs on a larger scale.

Although the overall quantity of NPS seized fell in

2016, an increasing number of countries have been

reporting NPS seizures, and concerns have been

growing over the harm caused by the use of NPS.

In several countries, an increasing number of NPS

with opioid effects emerging on the market have

been associated with fatalities. The injecting use of

stimulant NPS also remains a concern, in particular

because of reported associated high-risk injecting

practices. NPS use in prisons and among people on

probation remains an issue of concern in some coun-

tries in Europe, North America and Oceania.

VULNERABILITIES OF

PARTICULAR GROUPS

Many countries still fail to provide

adequate drug treatment and health

services to reduce the harm caused by

drugs

One in six people suffering from drug use disorders

received treatment for those disorders during 2016,

which is a relatively low proportion that has

remained constant in recent years.

Some of the most adverse health consequences of

drug use are experienced by PWID. A global review

of services aimed at reducing adverse health

consequences among PWID has suggested that only

79 countries have implemented both needle and

syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy.

Only four countries were classified as having high

levels of coverage of both of those types of

interventions.

Information on the availability of HIV testing and

counselling and antiretroviral therapy remains

sparse: only 34 countries could confirm the avail-

ability of HIV-testing programmes for PWID, and

17 countries confirmed that they had no such

Distribution of needle-syringes per PWID per year

>

200

100-200

High coverage

Moderate coverage

<

100

Low coverage

33

needle-syringes

distributed

per PWID globally

High coverage

Moderate coverage

Low coverage

>

40

20-40

<

20

16

OST clients

per 100 PWID

globally

Opioid substitution therapy (OST) clients per 100 PWID

Global targets for the distribution of needle-syringes

and opium substitution therapy missed

17

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

perceptions of a low risk of harm, makes the drug

among the most common substances whose use is

initiated in adolescence. Cannabis is often used in

conjunction with other substances and the use of

other drugs is typically preceded by cannabis use.

Two extreme typologies of drug use

among young people: club drugs in

nightlife settings; and inhalants

among street children

Drug use among young people differs from country

to country and depends on the social and economic

circumstances of those involved.

Two contrasting settings illustrate the wide range of

circumstances that drive drug use among young

people. On the one hand, drugs are used in recrea-

tional settings to add excitement and enhance the

experience; on the other hand, young people living

in extreme conditions use drugs to cope with their

difficult circumstances.

The typologies of drugs used in these two different

settings are quite different. Club drugs such as

“ecstasy”, methamphetamine, cocaine, ketamine,

LSD and GHB are used in high-income countries,

originally in isolated “rave” scenes but later in set-

tings ranging from college bars and house parties to

concerts. The use of such substances is reportedly

much higher among young people. Among young

people living on the street, the most commonly used

drugs are likely to be inhalants, which can include

paint thinner, petrol, paint, correction fluid and

glue.

Many street children are exposed to physical and

sexual abuse, and substance use is part of their

coping mechanism in the harsh environment they

are exposed to on the streets. The substances they

use are frequently selected for their low price, legal

and widespread availability and ability to rapidly

induce a sense of euphoria.

Young people’s path to harmful

substance use is complex

The path from initiation to harmful use of sub-

stances among young people is influenced by factors

that are often out of their control. Factors at the

personal level (including behavioural and mental

health, neurological developments and gene varia-

tions resulting from social influences), the micro

level (parental and family functioning, schools and

peer influences) and the macro level (socioeconomic

and physical environment) can render adolescents

vulnerable to substance use. These factors vary

between individuals and not all young people are

equally vulnerable to substance use. No factor alone

is sufficient to lead to the use of substances and, in

many instances, these influences change over time.

Overall, it is the critical combination of the risk

Substance use

initiation

Positive physical, social

and mental health

Harmful use

of substances

P

r

o

t

e

c

t

i

v

e

f

a

c

t

o

r

s

R

i

s

k

f

a

c

t

o

r

s

• Trauma and childhood

adversity

- child abuse and neglect

• Mental health problems

• Poverty

• Peer substance use and

drug availability

• Negative school climate

• Sensation seeking

Protective factors and risk factors for substance use

• Caregiver involvement

and monitoring

• Health and neurological

development:

- coping skills

- emotional regulation

• Physical safety and

social inclusion

• Safe neighbourhoods

• Quality school environment

Substance

use disorders

18

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

Drug use among older people requires

attention

Increases in rates of drug use among older

people are partly explained by ageing

cohorts of drug users

Drug use among the older generation (aged 40 years

and older) has been increasing at a faster rate than

among those who are younger, according to the lim-

ited data available, which are mainly from Western

countries.

People who went through adolescence at a time

when drugs were popular and widely available are

more likely to have tried drugs and, possibly, to have

continued using them, according to a study in the

United States. This pattern fits in particular the so-

called “baby boomer” generation in Western Europe

and North America. Born between 1946 and 1964,

baby boomers had higher rates of substance use

during their youth than previous cohorts; a signifi-

cant proportion continued to use drugs and, now

that they are over 50, this use is reflected in the data.

In Europe, another cohort effect can be gleaned

from data on those seeking treatment for opioid use.

Although the number of opioid users entering treat-

ment is declining, the proportion who were aged

over 40 increased from one in five in 2006 to one

in three in 2013. Overdose deaths reflect a similar

trend: they increased between 2006 and 2013 for

those aged 40 and older but declined for those aged

under 40. The evidence points to a large cohort of

ageing opioid users who started injecting heroin

during the heroin “epidemics” of the 1980s and

1990s.

Older people who use drugs require tai-

lored services, but few treatment pro-

grammes address their specific needs

Older drug users may often have multiple physical

and mental health problems, making effective drug

treatment more challenging, yet little attention has

been paid to drug use disorders among older people.

There were no explicit references to older drug users

in the drug strategies of countries in Europe in 2010

and specialized treatment and care programmes for

older drug users are rare in the region; most initia-

tives are directed towards younger people.

factors that are present and the protective factors

that are absent at a particular stage in a young per-

son’s life that makes the difference in their

susceptibility to drug use. Early mental and behav-

ioural health problems, poverty, lack of opportunities,

isolation, lack of parental involvement and social

support, negative peer influences and poorly

equipped schools are more common among those

who develop problems with substance use than

among those who do not.

Harmful substance use has multiple direct effects

on adolescents. The likelihood of unemployment,

physical health problems, dysfunctional social rela-

tionships, suicidal tendencies, mental illness and

even lower life expectancy is increased by substance

use in adolescence. In the most serious cases, harm-

ful drug use can lead to a cycle in which damaged

socioeconomic standing and ability to develop rela-

tionships feed substance use.

Poverty and a lack of opportunities for

social and economic advancement can

lead young people to become involved in

the drug supply chain

Young people are also known to be involved in the

cultivation, manufacturing and production of and

trafficking in drugs. In the absence of social and

economic opportunities, young people may deal

drugs to earn money or to supplement meagre

wages. Young people affected by poverty or in other

vulnerable groups, such as immigrants, may be

recruited by organized crime groups and coerced

into working in drug cultivation, production, traf-

ficking and local-level dealing. In some

environments, young people become involved in

drug supply networks because they are looking for

excitement and a means to identify with local groups

or gangs. Organized crime groups and gangs may

prefer to recruit children and young adults for drug

trafficking for two reasons: the first is the reckless-

ness associated with younger age groups, even when

faced with the police or rival gangs; the second is

their obedience. Young people involved in the illicit

drug trade in international markets are often part

of large organized crime groups and are used mainly

as “mules”, to smuggle illegal substances across

borders.

19

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

suffer from externalizing behaviour problems such

as conduct disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity

disorder and anti-social personality disorder. Women

with substance use disorders are reported to have

high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder and may

also have experienced childhood adversity such as

physical neglect, abuse or sexual abuse. Women who

use drugs may also have responsibilities as caregiv-

ers, and their drug use adversely affects their families,

in particular children. Such adverse childhood expe-

riences can be transgenerational and impart the risks

of substance use to the children of women with drug

use disorders.

Post-traumatic stress disorder among women is most

commonly considered to have derived from a his-

tory of repetitive childhood physical and sexual

abuse. Childhood adversity seems to have a different

impact on males and females. Research has shown

that boys who have experienced childhood adversity

use drugs as a means of social defiance. On the other

hand, girls who have experienced adversity are more

likely to internalize it as anxiety, depression and

social withdrawal and are more likely to use sub-

stances for self-medication.

Older drug users account for an increasing

share of deaths directly caused by drug

use

Globally, deaths directly caused by drug use increased

by 60 per cent from 2000 to 2015. People over the

age of 50 accounted for 39 per cent of the deaths

related to drug use disorders in 2015. However, the

proportion of older people reflected in the statistics

has been rising: in 2000, older people accounted for

just 27 per cent of deaths from drug use disorders.

About 75 per cent of deaths from drug use disorders

among those aged 50 and older are linked to the

use of opioids. The use of cocaine and the use of

amphetamines each account for about 6 per cent;

the use of other drugs makes up the remaining 13

per cent.

Women’s drug use differs greatly from

men’s

Non-medical use of tranquillizers and

opioids is common

The prevalence of the non-medical use of opioids

and tranquillizers by women remains at a compa-

rable level to that of men, if not actually higher. On

the other hand, men are far more likely than women

to use cannabis, cocaine and opiates. Women con-

tinue to account for only one in five people in

treatment. The proportion of females in treatment

tends to be higher for tranquillizers and sedatives

than for other substances.

While women who use drugs typically begin using

substances later than men, once they have initiated

substance use, women tend to increase their rate of

consumption of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and opi-

oids more rapidly than men. This has been

consistently reported among women who use those

substances and is known as “telescoping”. Another

difference is that women are more likely to associate

their drug use with an intimate partner, while men

are more likely to use drugs with male friends.

Women who have experienced childhood

adversity internalize behaviours and may

use drugs to self-medicate

Internalizing problems such as depression and anxi-

ety are much more common among women than

among men. Men are more likely than women to

d

r

u

g

u

s

e

r

s

drug use

disorders

More men than women initiate drug use

but after initiation women move faster

than men towards drug use disorders

d

r

u

g

u

s

e

r

s

“telescoping”

20

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2018

that some drug trafficking organizations may be

more likely to use women as “mules”.

Another narrative has emerged critiquing this

approach and arguing that women might be empow-

ered key actors in the drug world economy. Cases

have also been documented in which women are

key actors in drug trafficking, by choice. Neither

explanation provides a complete picture of women’s

involvement in the drug supply chain — some are

victims, others make their own decisions. Involve-

ment in the illicit drug trade can offer women the

chance to earn money and achieve social mobility,

but it can also exacerbate gender inequalities because

they may still be expected to perform the traditional

gender roles of mothers, housekeepers and wives.

Overall, although a multiplicity of factors are behind

the participation of women in the drug trade, it has

been shown to be shaped by socioeconomic vulner-

ability, violence, intimate relationships and economic

considerations.

Prisoners, in particular women, are at

higher risk for infectious diseases but

are poorly served

People in prisons and other closed settings are at a

much greater risk of contracting infections such as

Women are at a higher risk for infectious

diseases than men

Women make up one third of drug users globally

and account for one fifth of the global estimated

number of PWID.

Women have a greater vulnerabil-

ity than men to HIV, hepatitis C and other

blood-borne infections. Many studies have reported

female gender as an independent predictor of

HIV and/or hepatitis C among PWID, particu-

larly among young women and those who have

recently initiated drug injection.

The relationship between

women and the drug trade is

not well understood

Women may not only be victims

but also active participants in the

drug trade

Women play important roles throughout the drug

supply chain. Criminal convictions of women who

presided over international drug trafficking organi

-

zations — particularly in Latin America, but also

in Africa — attest to this. Women’s involvement in

opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan and coca

cultivation in Colombia is well documented, as is

the role that women play in trafficking drugs, as

drug mules.

However, there is a lack of consistent data from

Governments to enable a deeper understanding of

those roles: 98 countries provided sex-disaggregated

drug-related crime data to UNODC for the period

2012–2016. Of the people arrested for drug-related

offences in those countries during that period, some

10 per cent were women.

As suggested in several studies, women may become

involved in drug trafficking to sustain their own

drug consumption; however, as shown in other stud-

ies, some women involved in trafficking in drugs

are victims of trafficking in persons, including traf-

ficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation.

Women’s participation in the drug supply chain can

often be attributed to vulnerability and oppression,

where they are forced to act out of fear. Moreover,

women may accept lower pay than men: some

researchers have noted that women may feel com-

pelled to accept lower rates of payment than men

to carry out drug trafficking activities, which means

Women

with drug use

disorders

H

I

V

a

n

d

h

e

p

a

t

i

t

i

s

C

c

h

i

l

d

h

o

o

d

a

d

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

a

n

d

a

b

u

s

e

g

e

n

d

e

r

-

b

a

s

e

d

v

i

o

l

e

n

c

e

p

o

s

t

-

t

r

a

u

m

a

t

i

c

s

t

r

e

s

s

d

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

s

t

i

g

m

a

a

n

d

d

i

s

c

r

i

m

i

n

a

t

i

o

n

s

o

c

i

a

l

i

n

e

q

u

a

l

i

t

i

e

s

i

n

c

a

r

c

e

r

a

t

i

o

n

d

y

s

f

u

n

c

t

i

o

n

a

l

f

a

m

i

l

y

Causes and consequences of drug use

disorders among women

21

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

tuberculosis, HIV and hepatitis C than the general

population, but access to treatment and prevention

programmes is often lacking. Even where such pro-

grammes are available, they are not necessarily of

the same standard as those provided in the com-

munity. The lack of access to prevention measures

in many prisons can result in the rapid spread of

HIV and other infections.

People who use heroin are exposed to a severe risk

of death from overdose after release from prison,

especially in the first two weeks. Such deaths are

related to a lowered tolerance to the effects of heroin

use developed after periods of relative abstinence,

including during incarceration. However, released

prisoners are rarely able to access overdose

management interventions, including prevention

medications such as naloxone, or treatment for

substance dependence, including methadone.

Women who are incarcerated have even less access

than their male counterparts to health-care services

to address their drug use, other health conditions

and sexual and reproductive health needs. In addi-

tion, fewer women than men generally receive

enough preparation and support for their return to

their family or to the community in general. Upon

release, women face the combined stigma of their

gender and their status as ex-offenders and face chal

-

lenges, including discrimination, in accessing

health-care and social services.

714,000 female prisoners

9,6 million male prisoners

35% drug offences 19% drug offences

A higher proportion of women than men are in prison

for drug-related offences

Almost 11 million people inject drugs

1.3 million people who inject drugs

are living with HIV

5.5 million are living with hepatitis C

1.0 million are living with both

hepatitis C and HIV

Source: Based on Roy Walmsley, “World prison population list”, 11th ed. (Institute for Criminal Policy Research, 2016)

and Roy Walmsley, “World female imprisonment list”, 4th ed. (Institute for Criminal Policy Research, 2017).

Share of prisoners for drug offences based on 50 Member States (UNODC, Special data collections on persons held in

prisons (2010-2014), United Nations Surveys on Crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Systems (UN-CTS).

23

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The information presented in the World Drug Report

2018 illustrates the unprecedented magnitude and

complexity of the global drug markets. The adverse

health consequences caused by drug use remain sig-

nificant, drug-related deaths are on the rise and there

are ongoing, concentrated opioid epidemics.

This situation calls for renewed efforts to support

the prevention and treatment of drug use and the

delivery of services aimed at reducing the adverse

health consequences of drug use, in line with targets

3.5 and 3.3 of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Young people need to be made aware not only of

the medical but also of the socioeconomic harm

associated with drug use. Efforts to support the pre-

vention and treatment of drug use also include

providing people who use drugs with the necessary

knowledge and skills to prevent overdoses, includ-

ing through the administration of naloxone;

providing continuity of health-care services for those

in prison and upon their release; and scaling up core

interventions, as outlined in the WHO, UNODC,

UNAIDS Technical Guide for Countries to Set Targets

for Universal Access to HIV Prevention, Treatment and

Care for Injecting Drug Users

, to help prevent the

spread of HIV and hepatitis C among PWID.

These efforts can only be effective if they are based

on scientific evidence and respect for human rights

and if the stigma associated with drug use is removed.

Such stigma can be overcome by increasing under-

standing of drug use disorders as complex,

multifaceted and relapsing chronic conditions that

require continuing care and interventions from

many disciplines.

There are emerging trends that have the potential

to trigger a supply-driven expansion of the illicit

markets for heroin, prescription opioids and cocaine.