Patient-Centered Education in Wound Management:

Improving Outcomes and Adherence

Lynelle F. Callender, DNP, RN, Vice Chair, Nursing Online, Advent Health University, Orlando, Florida

Arlene L. Johnson, DNP, RN, Coordinator, Nurse Practitioner Program, Advent Health University, Orlando, Florida

Rose M. Pignataro, PhD, DPT, PT, CWS, CHES, Associate Professor, Assistant Director, Physical Therapy Program, Emory & Henry College, Marion, Virginia

CME

1 AMA PRA

Category 1 Credit

TM

ANCC

2.5 Contact Hours

GENERAL PURPOSE: To educate wound care practitioners about methods of communication that can help promote patient adherence

to wound healing recommendations.

TARGET AUDIENCE: This continuing education activity is intended for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses

with an interest in skin and wound care.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES/OUTCOMES: After participating in this educational activity, the participant will:

1. Distinguish the use of theoretical frameworks to promote patient adherence to prescribed wound healing recommendations.

2. Synthesize the principles of motivational interviewing to best encourage patients to adhere to prescribed wound healing

recommendations.

3. Select the appropriate self-care strategies for patients who have nonhealing wounds.

ABSTRACT

Patients with chronic wounds make daily decisions that affect

healing and treatment outcomes. Patient-centered education

for effective self-management decreases episodes of care

and reduces health expenditures while promoting

independence. Theoretical frameworks, including the Health

Belief Model, Theory of Planned Behavior, Social Cognitive

Theory, and Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change, can

assist healthcare providers in identifying strategies that

enhance adherence. These strategies include the use of

motivational interviewing, a communication technique

designed to elicit patients’ perspectives regarding treatment

goals, outcome expectations, anticipated barriers, and

intentions to follow provider recommendations.

KEYWORDS: barriers, chronic wounds, education,

health behavior theory, patient outcomes,

wound management, wound healing

ADV SKIN WOUND CARE 2021;34:403–10.

DOI: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000753256.29578.6c

INTRODUCTION

Patients’ daily decisions and activities have a significant

impact on wound healing outcomes independent of the

healthcare provider.

1

Therefore, patient-centered educa-

tion for effective self-management is an essential compo-

nent of the plan of care.

2

Instrumental self-management

skills include wound cleansing, dressing changes, and

recognizing signs and symptoms of infection.

3

An under-

standing of theoretical frameworks and evidence-based

approaches to patient-centered education can assist wound

care practitioners in promoting patient adherence. The

World Health Organization defines adherence as “the extent

to which a person’sbehavior—taking medication, following

a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes—corresponds

with agreed recommendations from the healthcare pro-

vider.”

4

It is important to note that adherence is not the

same as compliance. The term “adherence ” implies col-

laboration, in which patients actively choose to follow

the provider’s advice based on shared responsibility

for health outcomes, as opposed to “compliance,” which

connotes submission to provider directives.

5

Effective education and enhanced adherence decrease

episodes of car e, reduce health expenditur es, and prevent

serious complications.

3,6

Impediments to adherence en-

compass provider characteristics as well as patient character-

istics. Among providers, barriers include anticipated patient

nonadherence, perceived lack of education ef f ec t iv en es s,

The authors, faculty, staff, and planners in any position to control the content of this CME/NCPD activity have disclosed that they have no financial relationships with, or financial

interests in, any commercial companies relevant to this educational activity. To earn CME credit, you must read the CME article and complete the quiz online, answering at least 7 of

the 10 questions correctly. This continuing educational activity will expire for physicians on July 31, 2023, and for nurses June 7, 2024. All tests are now online only; take the test at

http://cme.lww.com for physicians and http://www.NursingCenter.com/CE/ASWC for nurses. Complete NCPD/CME information is on the last page of this article.

Clinical Management Extra

WWW.ASWCJOURNAL.COM 403 ADVANCES IN SKIN & WOUND CARE • AUGUST 2021

Copyright © 2021 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

insufficient training in patient-centered education tech-

niques,

1,7

and time constraints within the clinical envi-

ronment.

1

Many providers are also hesitant to discuss

patients’ personal behaviors for fear of provoking defen-

siveness or damaging rapport.

2,7

Application of theoretical

frameworks assists providers in selecting communica-

tion techniques that incorporate patie nts ’ perspectives

to ove rcome barr iers to quality wound care.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS FOR PATIENT-CENTERED

EDUCATION

Health Belief Model

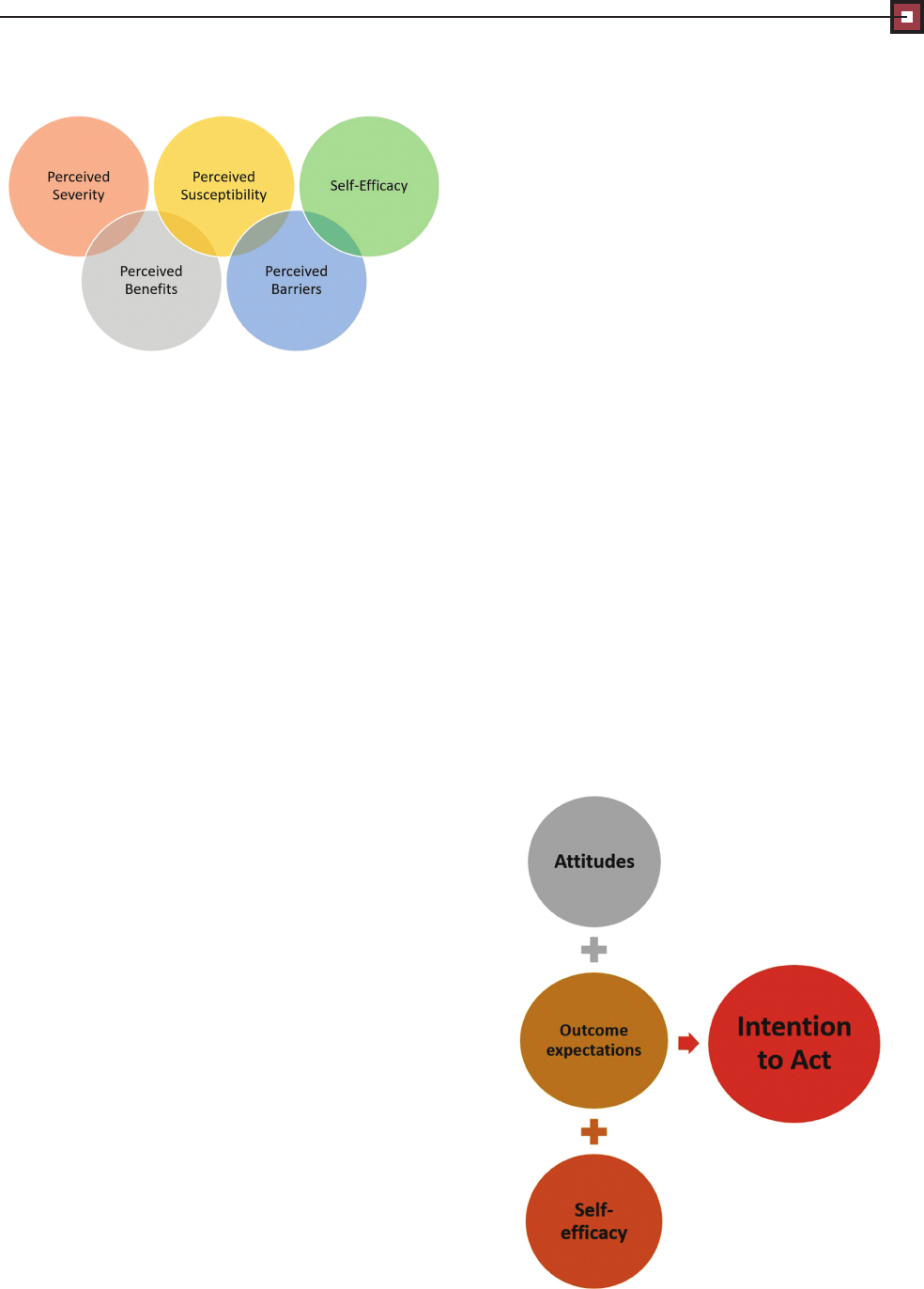

The Health Belief Model (HBM) describes factors that in-

fluence patient adherence, such as perceptions of health

risk severity, negative health outcomes, and the benefits

of recommended health behaviors.

2

The HBM also in-

corporates self-efficacy, or patient belief in their ability

to successfully enact provider recommendations and

achieve intended goals. Providers can apply the HBM

to discuss patients’ personal risks and benefits of action.

Using the HBM also helps providers understand patient

barriers to enacting treatment recommendations, includ-

ing patients’ confidence in their ability to self-manage

their condition (Figure 1).

Theory of Planned Behavior

According to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), ad-

herence is primarily determined by behavioral inten-

tions. Factors that shape intentions include patients’

attitudes toward provider recommendations, as well as

outcome expectations, or the a nticipated results o f

adherence.

8

Like the HBM, the TPB also includes

self-efficacy.

2

Low self-efficacy diminishes adherence even

when patients strongly value the outcome.

8

Providers

can apply the TPB to investigate and address factors that

influence self-efficacy and outcome expectations. These

factors include personality, age, gender, education level,

health literacy, socioeconomic status, and learning pref-

erences

8

(Figure 2).

Social Cognitive Theory

Like the HBM and TPB, Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

stresses the importance of self-efficacy. Wound care pro-

viders can apply SCT to build self-efficacy and match the

benefits of treatment recommendations with the patient’s

personal goals.

2

Long-term adherence also requires that

the patient have knowledge, skills, and the ability to

self-assess and respond to changes in their condition.

9

These changes may include signs of infection, delayed

healing, and the need for further consultation.

Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM)

2

describes patients’

readiness to engage in health behaviors:

(1) Precontemplation is when patients are not consid-

ering change. This may be attributable to a lack of

awareness, low perceived importance, or low desire to

engage in recommended health behaviors.

(2) Contemplation occurs when patients begin thinking

about adherence, or recommitment to adherence, if a

lapse in behavior has occurred.

(3) Preparation is when patients are taking steps toward

initiating adherence within the next 2 weeks.

(4) Action is when the person has initiated and is engaged

in adherence.

(5) Maintenance occurs when adherence is sustained for

at least 6 months.

Patients do not always progress through the stages of

change in a linear, predictable pattern. Some may lapse

Figure 1. HEALTH BELIEF MODEL

Figure 2. THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR

ADVANCES IN SKIN & WOUND CARE • AUGUST 2021 404 WWW.ASWCJOURNAL.COM

Copyright © 2021 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

into earlier stages when met with challenges. Even after

maintenance, relapse can occur despite temporary suc-

cess.

2

Provid ers can promote adherence by tailoring educa-

tion interventions to match patients’ readiness to change

(Figure 3).

PATIENT-CENTERED COMMUNICATION TECHNIQUES

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a patient-centered

communication technique designed to help patients rec-

ognize discrepancies between nonadherence and desired

treatment outcomes.

10

Providers can use this technique

to encourage patients to prioritize outcomes based on their

personal values. Further, MI enables providers and pa-

tients to collaboratively decide which recommendations

work best given patients’ lifestyle, prefer ences, and avail-

able resources.

11

During MI, providers ask open-ended

questions to gain insight into patient intentions, abilities,

and willingness to adhere to treatment recommenda-

tions.

12

Then, providers use these insights to create individu-

alized goals and tailored wound management strategies.

Wound care providers can also promote adherence by

tracking goals and acknowledging patients’ accomplish-

ments.

2

Setting small, incremental goals promotes

gradual increases in patient self-efficacy.

13

These g oals

should be SMART (specific, measurable, achievable,

relevant, and timely); otherwise, lack of attainment

can discourage adherence.

2

In addition, it is important for

patients and providers to discuss potential challenges and

collaboratively identify strategies to pr event behavioral

lapses.

2

Scheduled follow-ups help affirm positive results

and provide an opportunity to review any unexpected bar-

riers to adherence.

13

Discussing barriers helps patients

maintain positive health behaviors, strengthen commit-

ment, and identify new strategies when necessary.

13

There are two basic phases in MI: (1) eliciting “change

talk,” that is, desire, reasons, and ability to change; and

(2) p romoting commitm ent to new beh aviors.

10

The

mnemonic OARS (open-ended questions, affirmations,

reflective listening, and summarization) describes com-

munication techniques commonly used in MI. Open-

ended questions inspire introspection regarding the pros

and cons of provider recommendations and facilitate

adherence. Affirmations foster confidence in patient

ability t o engage in effective self-care and achieve

positive outcomes. Reflective listening clarifies pa-

tients’ intentions and meaning and allows providers

to emphasize positive decisional balance, including

the patients’ expressed need for adherence, potential

benefits, and ability to succeed. Summarization is a tech-

nique providers can use to wrap up the conversation or

transition to a new topic by reviewing important points

and confirming patients’ understanding and agreement

with the recommendations.

14

Frameworks to assist providers in implementing MI

include the “5As” and “5Rs.”

1

During initial conversa-

tions with patients, providers can apply the “5As:”

1

(1) Ask patients about self-care.

(2) Advise patients about the risks of nonadherence.

(3) Assess patient readiness to follow recommendations.

(4) Assist patients in creating goals and plans to imple-

ment recommendations.

(5) Arrange for follow-up support.

If patients are not yet ready to engage in recommended

health behaviors, providers can use the “5Rs:”

1

(1) Discuss the relevance of the recommendations within

the context of patient goals.

(2) Guide patients to consider risks of nonadherence.

(3) Suggest possible rewards or positive outcomes.

(4)Invite patients to share anticipated roadblocks or bar-

riers to adherence.

(5) Repetition: revisit topics during future conversations

to negotiate a healthy course of action.

When using MI, providers should respect patient auton-

omy. Acknowledging patients’ right to self-determination

reduces the likelihood of resistance and defensiveness. By

expressing empathy toward patient challenges and invit-

ing opposing viewpoints, providers can promote patient

ownership and control of their own health.

10

Time constraints are one of the greatest barriers to ap-

plying MI within clinical settings.

15

The pressures of a

busy schedule can restrict provider ability to engage in

detailed conversations with patients. Although tradi-

tional MI requires 30 to 60 minutes, brief MI can take

as little as 5 to 10 minutes.

10

Brief MI focuses on a single

goal. Once the patient and provider select this goal, the

provider can use MI techniques to guide the conversa-

tion toward specific steps designed to achieve the desired

outcomes. Conversations should focus on the following

Figure 3. TRANSTHEORETICAL MODEL OF BEHAVIOR CHANGE

WWW.ASWCJOURNAL.COM 405 ADVANCES IN SKIN & WOUND CARE • AUGUST 2021

Copyright © 2021 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

aspects: what actions patients should perform and what

is an acceptable degree of adherence (eg, how often or

how much adherence is required).

Communication throughout the course of treatment allows

providers to continue to reinforce patients’ motivations. For

patients who are not ready to follow recommendations, fur-

ther discussion of their concerns and perceived barriers

may be necessary. Often, past failures and challenges can de-

crease patient confidence and ability to engage in appropriate

self-care. Providers can help patients reframe failed attempts

as opportunities to learn about ineffective approaches to

adherence while identifying suitable alternatives.

Once an agreement has been reached, a written action

plan promotes adherence. As part of the plan, providers

should encourage patients to discuss feasibility and use-

fulness of the treatment recommendations.

15

The plan

should also include scheduled follow-ups in person, by

phone, and/or electronic communication.

16

Finally, providers must remember that nonadherence

can be intentional or unintentional.

17

Reasons for inten-

tional nonadherence include pain and patients’ percep-

tions regarding the feasibility and effectiveness of treatment

recommendations, as well as insufficient explanations

from clinicians regarding the rationale supporting recom-

mendations.

17

PATIENT EDUCATION

Effective patient education involves three essential com-

ponents: self-care skills, how to recognize and respond

to problems, and preventive management. Patients’ un-

derstanding of the healing process may also greatly im-

prove wound outcomes.

18

For example, patients may

not understand that wounds should heal from the base

to the surface. It is also important that patients can distinguish

“good” versus “bad” tissue. Pictures may help patients iden-

tify how “good” tissue should look as their wound begins to

heal. Healthy granulation tissue has a red, glossy appearance.

In contrast, necrotic tissue is tan, yellow, or black.

18

Providers

should also advise patients that drainage should decrease

as healing progresses

18

and “normal” drainage de-

pends on the color, consistency, amount, and odor.

Other essential self-care skills include proper hand-

washing, wound cleansing, and dressing changes. Pro-

viders should discuss appropriate cleansing solutions

and caution patients to avoid irritating or cytotoxic sub-

stances. Using the wrong cleanser may delay healing.

18

Further, many people believe that a dry wound prevents

infection; providers should proactively educate patients

and caregivers about moist wound healing. Providers

should encourage patients to seek follow-up if the wound

becomes too dry so that they can discuss the need for a

different type of dressing.

Patients and caregivers also need education on how and

when to replace dressings.

18

During each dressing change,

wounds should be cleaned and assessed.

18

Providers should

review signs and symptoms of infection so that patients and

caregiver s can seek timely medical attention.

18

Adverse

changes include increased pain or tenderness, increased exu-

date, changes in the type of exudate (eg, pus versus serous

drainage), swelling, heat, periwound discoloration, and foul

odor.

18

Patients and caregivers should also be aware of sys-

temic symptoms of infection, such as fever , chills, nausea,

and malaise.

18

Pain may interfere with patient ability and

willingness to clean wounds and change dressings.

3

There-

fore, providers may initiate patient and caregiver train-

ing in analgesic interventions, such as topical agents

and/or nonadherent dressings.

3

Ideally, providers should supplement verbal instruc-

tion with written material and demonstration.

3

Consis-

tent with theoretical frameworks for health behavior

change, providers should tailor instruction to match pa-

tients’ health literacy, language, culture, and specific

concerns. Treatment outcomes are improved when pro-

viders emphasize the relevance of the information based

on patient goals. Personalized education enhances ad-

herence, patient satisfaction, and wound healing.

3

Providers should also consider patient perceptions

that pose potential challenges to adherence. Important

factors include:

18

(1) What are patients’ beliefs regarding the cause of the

wound?

(2) What are the effects of the wound on quality of life,

ability to perform activities of daily living, and so on?

(3) What is the perceived severity of the wound? How

long do patients think it will take for their wound to

heal?

(4) How do patients think their wounds should be treated?

(5) What are the most important treatment results pa-

tients hope to achieve?

(6) What fears do patients have regard ing wound treatment?

Nutrition

Education concerning specialized nutrition requirements

is particularly important for patients with underlying

comorbidities, such as diabetes, renal disease, anemia,

or difficulty eating.

19

Dietary advice and information

concerning the use of supplements can enhance patients’

sense of control over the wound healing process.

Nutritional impediments to healing include inadequate

protein and carbohydrate intake.

19

Supplements, such

as vitamins A, C, D, and E, and minerals, such as zinc,

copper, selenium, and folic acid, may also be prescribed.

19

Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Injuries

Patients with mobility and/or sensory impairments have

an elevated risk of pressure injuries (PIs). Patient educa-

tion on skin protection, t urning and positioning, and

notifying caregivers about tender and painf ul areas

ADVANCES IN SKIN & WOUND CARE • AUGUST 2021 406 WWW.ASWCJOURNAL.COM

Copyright © 2021 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

increases autonomy by enabling patients to self-advocate

and supervise appropriate treatment interventions, even

when caregiver assistance is required to carry out provider

recommendations.

20

Patients and caregivers should be

aware of common PI locations (heels, sacrum, ischium,

and greater tuberosity), as well as intrinsic and extrinsic

factors that increase vulnerability and delayed healing,

such as incontinence and localized skin trauma.

21,22

Pa-

tients can decrease their vulnerability to tissue damage

using specialized support surfaces and strategies for po-

sitioning and pressure redistribution.

21,22

These strate-

gies should include keeping the head of the bed at or

below 30° whenever possible to decrease friction and

shear.

21

Depending on their physical abilities, patients

may be taught how to use assistive devices, such as an

overhead trapeze and/or grab bars, to perform reposi-

tioning.

23

Information regarding the characteristics of

an ideal support surface also helps equip patients to en-

sure optimal prevention and treatment.

23

Providers should also educate patients on skin assess-

ment and signs of impending damage. Even if patients

are reliant on caregivers to examine their skin, the ability

to recognize problems and seek appropriate treatment

fosters independence.

23

In addition, patients and care-

giversoftenrequireinstructionregardingproperhygiene

and skin care.

23

As with other types of chronic wo u nds ,

patients with PIs benefit from education regar ding behav-

ioral risks, such as tobacco use, nutrition, hydration, ex-

ercise, and medication adherence.

23

Peripheral Arterial Disease and Treatment of Arterial Ulcers

Patients with peripheral arterial disease often underesti-

mate their risk of serious complications.

24

This may stem

from lack of knowledge or denial about the impact of

nonadherence.

24

Providers can address these issues by

reviewing factors that mitigate risks, such as tobacco cessa-

tion, exercise, and proper diet.

25

Further, providers should en-

courage patients to engage in proper self-management of

common comorbidities, such as hypertension and type

2diabetes.

25

Adherence and self-care can be enhanced

by teaching patients how to interpret their own test re-

sults (eg, total cholesterol and total triglycerides).

25

Depending on the severity of circulatory insufficiency,

it may be best to keep arterial wounds dry pending re-

vascularization. This is an exception to typical patient

education regarding moist wound healing. Providers

should explain that ischemic ulcers often involve thick,

black, leathery eschar so that patients are not tempted

to soak the wound.

25

Prevention and Treatment of Venous Leg Ulcers

One of the most damaging aspects of venous insufficiency

is venous hypertension and lower extremity swelling.

Therefore, patient education should be directed toward

strategies that promote venous return and reduce edema.

These strategies often include the use of compression stock-

ings, which patients should don immediately upon waking

when limb volume is at its lowest. Applying stockings before

placing the legs in a dependent position tends to be the most

beneficial.

18

As part of self-management, patients should

avoid crossing their legs or keeping their legs in a dependent

position for prolonged periods. Instead, patients should ele-

vate their legs above the level of the heart at various intervals

througho ut the day.

18

Because most lower extremity venous return results

from muscle activity, exercises, such as walking and an-

kle pumps, are very helpful.

18

Providers should tailor

exercise recommendations to patients’ individual fitness

levels and any physical impairments. In addition, exercise

may assist patients with weight management,

18

because

obesity also impedes venous return.

Patients with venous insufficiency often need advice

about strategies to protect against inadvertent lower

extremity trauma, dermatitis, and ulceration.

26

Effective

prevention includes the use of appropriate footwear,

18

skin cleansers, and topical agents.

26

Additional steps that

patients can take to prevent or reduce venous insufficiency

and risk of ulceration include tobacco cessation.

26

Prevention and Treatment of Diabetic/Neuropathic Foot Ulcers

In patients with peripheral neuropathy, the loss of pro-

tective sensation is a primary risk factor for wounds

and delayed healing. Therefore, protective interventions

are critical. Patients should be empowered to perform

proper foot care, including choosing socks and shoes

that prevent compression, friction, and shear.

18

Through-

out the day, patients should remove their shoes and socks

to inspect the skin for any signs of redness or irritation.

18

Timing for self-checks should be based on individual

risks. When “break ing in” new shoes, self-checks should

occur at least every 2 hours.

18

Because most neuropathic ulcers occur on the plantar

aspect of the foot, treatment for existing wounds often

includes the use of offloading devices to redistribute

pressure. Providers and patients should discuss barriers

to adherence, including low perceived susceptibility and

severity. This is exacerbated by sensory deficits that re-

sult in low or absent pain signals despite the presence

of significant integumentary damage. Wearing shoes or

slippers with closed backs and nonskid soles, even when

ambulating short distances within the home, reduces the

likelihood of inadvertent trauma. If an offloading device

is used, it must be donned whenever the patient is weight-

bearing, even if the patient is only going from the bed to

the bathroom in the middle of the night.

Treatment outcomes for neuropathic ulcers are also

heavily dependent on patients’ adherence to nutrition

recommendations, blood glucose monitoring, physical

WWW.ASWCJOURNAL.COM 407 ADVANCES IN SKIN & WOUND CARE • AUGUST 2021

Copyright © 2021 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

activity, and weight management.

27

Patient education

that includes explicit steps for diet and exercise is more

likely to achieve success than generic recommendations.

27

Self-management is influenced by patients’ cognitive

understanding, motivation level, and ability to trouble-

shoot problems and barriers.

27

In patients with diabetes,

low perceived severity of illness and its consequences may

be influenced by family history and assumptions that dia-

betesisanaturalpartofgeneticsand/oraging.

27

These as-

sumptions can reduce outcome expectations and

self-efficacy by creating the impression that diabetes and

its consequences are unavoidable.

27

Patients and pro-

viders should discuss these perceptions and promote

skills that enhance self-care, including the ability to trou-

bleshoot unanticipated problems and barriers.

27

Other

barriers to adherence may include the lack of measur-

able results for patients who are adherent yet still expe-

rience disease progression.

27

These barriers can be

mitigated by social-environmental support from family,

friends, and community resources.

28

From a cognitive perspective, the ability to record and

interpret glucose measurements, calculate medication

doses, and read nutrition labels requires a certain level of lit-

eracy and mathematical skill.

27

Providers should also assist

patients in understanding the differ ence between test results

that show immediate glycemic control (plasma glucose

level) versus long-range control (hemoglobin A

1c

;Table1).

27

CASE REPORT

Mrs H. (fictional patient) is a 60-year-old catering chef re-

ferred for outpatient wound management secondary to

a nonhealing ulcer on the plantar aspect of her left foot.

The wound has been present for more than 19 weeks

and has increased in depth since onset. Clinical presentation

includes peripheral neuropathy with loss of protective

sensation, poor glycemic management, and a history of

tobacco use and sedentary lifestyle.

The patient is experiencing barriers to performing prior

recommendations for wound cleansing, use of a hydrogel

dressing, and left non-weight-bearing using a knee scooter.

The following represents a dialogue between Mrs H. and

her doctor of physical therapy (DPT)/certified wound

management specialist. The conversation exemplifies the

use of MI techniques and theoretical frameworks.

DPT: Mrs H., thank you for agreeing to meet with me

to discuss your plan of care. I understand that you are

concerned about the lack of healing in your foot. I agree

that we need to talk about what we can change to make

sure that your wound improves.

Mrs H.:Ijustdon’t see the point in coming here. This

wound keeps getting bigger no matter what I do.

DPT: I am sure that must be very frustrating for you. I

see that you are not using the knee scooter today. Are

you having trouble with it?

Mrs H.: It makes my other leg very tired, and my back

gets sore.

DPT: Thank you for telling me. We certainly don’twant

to cause any other problems for you. We can definitely

talk about some other ideas besides the scooter. First,

can you tell me about some of the things you have been

doing at home in between visits?

Mrs H.: Well, my husband helps me take the ban-

dage off so that I can soak my foot every night. I make

sure I dry it really well, and then we put a new piece

of gauze on it.

DPT: What type of shoes have you been wearing?

Mrs H.: I usually wear these plastic clogs because they

are easy to slip on and off.

DPT: Because this wound is on the bottom of your

foot, one of the things that could help it heal is to take

some of the pressure off the area with a special walking

boot. Is that something you might be interested in?

Mrs H.: Well, it w ould d epend on how hard it is to

get the boot on by myself. My husband leaves for work

before I get dressed in the morning, and it’shardforme

to bend.

DPT: Well, the type of boot I am thinking of slides on

and closes with Velcro. Can we try one on to see what

you think? [produces walking boot]

Mrs H.: Oh man, that thing looks bulky and heavy.

DPT: It is kind of bulky, but I think you have enough

strength and balance to move around using the boot. It

may not be as heavy as you think. [Hands Mrs H. the walk-

ing boot]

Mrs H.: [makes a face and shakes her head] I think I

would rather stick with my clogs.

DPT: Would it be all right if I explained a little more

about why I think the walking boot will be so helpful?

Table 1. ESSENTIAL SELF-MANAGEMENT KNOWLEDGE

AND SKILLS

• Cause of the wound and contributing factors

• Anticipated healing time

• Moist wound healing principles (assuming there is adequate blood

supply for healing)

• Characteristics of a healthy wound bed

• Wound cleansing techniques and timing

• How and when to change wound dressing

• Signs and symptoms that indicate need for urgent medical attention

• Guidelines and techniques for treating the wound cause (eg, turning,

positioning, and pressure redistribution for pressure injuries)

• Activity modifications and rationales

• How to monitor and manage comorbidities

• Medication dosing and reason for each medication

• Nutrition recommendations, including proper hydration

ADVANCES IN SKIN & WOUND CARE • AUGUST 2021 408 WWW.ASWCJOURNAL.COM

Copyright © 2021 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

If you still don’t agree, I will respect your decision. I just

want you to have all the necessary information to make

good choices.

Mrs H.: [sighs] OK, I am listening.

DPT: Imagine you cut your finger here on the knuckle

while you were working in the kitchen. Every time you bend

your finger , it puts strain on that cut and stops it from healing.

What’s happening now with your foot is that every time you

stand or walk, it puts the same type of strain on the wound

and makes it harder for the body to repair it.

Mrs H.: That makes sense, but I can’t sit around and

put my feet up. I need to stand and walk to do my job,

and we can’t afford to have me out of work.

DPT: I understand that would be very difficult. In-

stead of having you stay out of work, this walking boot

would help redistribute the pressure on the bottom of

your foot while the wound is healing. You could use it

to stand and move around the kitchen while you are fill-

ing your catering orders.

Mrs H.: OK, I am willing to try it.

DPT: Great! There are several dif ferent options for

redistributingthepressure.Thisisthetypeofbootweuse

with most of our patients, but if it isn’tcomfortable,oryou

have trouble putting it on or taking it off by yourself, I want

you to let us know so that we can work together to find

something else that will work for you. How does that sound?

Mrs H.: That sounds reasonable.

The conversation continues after a brief session of gait

training using the walking device/pressure redistribu-

tion boot:

DPT: What do you think of the boot now that we have

tried it out?

Mrs H.: It’s OK, but it looks ugly.

DPT: I agree, I don’t think we will be starting any fash-

ion trends with this one! On a serious note, how impor-

tant is the look of this boot compared with your ability to

continue to work while your foot heals? Do you think

you can make that compromise?

Mrs H.: Of course—I mean, we aren’t really dressing

for looks while we are working in the kitchen.

DPT: OK, great. For this to work, it will be important

for you to put it on whenever you are on your feet, even

if you are just going from the bed to the bathroom in the

morning when you first wake up. Aside from the ap-

pearance, is there anything else that might make it diffi-

cult for you to wear the walking boot?

Mrs H.: Well, I do feel a little uneven when I walk in

this thing, like one leg is longer than the other.

DPT: Good point; one leg is essentially longer than the

other because of the height difference between your clog

and the walking boot. Let’s have you put on the sneakers

you brought in when you came for your last visit. We

should be able to place a small lift inside your other shoe

to help make the height a little more even.

Mrs H.: I think that would really help. Is there any-

thing else we can do to help this stupid foot heal faster?

I am really getting tired of this.

DPT: Yes, there are definitely other changes we can

talk about. Because you are coming back in 2 days, let’s

see how the walking boot works for you first. Then, if you are

open to it, my recommendation would be for us to start

thinking about how you can improve your blood sugar

levels, which is another common barrier to healing.

Mrs H.: You’re not going to lecture me about losing

weight, are you?

DPT: I am not a big fan of lecturing another adult, but

it is something I would like to discuss. Just like every-

thing else we talk about, please let me know if you feel

like I am crossing the line, and I will back off.

Mrs H.: I really appreciate how you give me a say in

things. Thank you.

DPT: Thank you for trusting me and telling me what

you really think! If we are going to get this wound to

close, it’s very important that you and I work together

as a team. I will see you in a couple of days. Please call

if you have any questions in the meantime.

CONCLUSIONS

Providers can become frustrated by patient nonad-

herence and its effects on chronic wound outcomes.

Reexamining reasons for nonadherence enables providers

to respond productively.

18

Patients may feel overwhelmed

by the physical and psychological changes caused by

chronic wounds. Self-management can also feel over-

whelming because of the number and complexity of

treatment recommendations.

5

The likelihood of adherence is improved when clinicians

link recommendations to individual outcome expectations

and goals.

17

Despite patient willingness to follow recom-

mendations, unintentional nonadherence may still occur,

particularly if provider instructions are not clear.

18

Collab-

orative communication strategies, such as MI, can help

providers detect and address problems with comprehen-

sion or other unforeseen barriers. Providers should also

consider patient readiness to change. Successful wound

management often takes time, patience, and effort to de-

velop a deeper rapport before patients can adhere to

provider recommendations.

18

PRACTICE PEARLS

• Patient education on wound management skills,

such as cleansing, dressing changes, and recognizing

infection, can significantly improve treatment outcomes.

• A collaborative approach to wound prevention and

management also optimizes treatment outcomes.

• Theory-based assessment helps providers work with

patients to determine the patient’s readiness to change,

need for information, and perceived barriers to adherence.

WWW.ASWCJOURNAL.COM 409 ADVANCES IN SKIN & WOUND CARE • AUGUST 2021

Copyright © 2021 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

• Asking open-ended questions, such as in MI, allows

providers to better understand patient perspectives.

• Important questions to ask include: What caused this

wound?Howdoesthiswoundaffectyourday-to-day

life? How long do you think it will take for your wound

to heal? How do you think this wound should be

treated? What are the most important results

you hope to achieve with treatment? What fears

or concerns do you have about your treatment?

•

REFERENCES

1. Krist A, Tong S, Aycock R, Longo D. Engaging patients in decision-making and behavior change to

promote prevention. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017;240:284-302.

2. Allen C. Supporting effective lifestyle behavior change interventions. Nurs Stand 2014;28(24):51-8.

3. Chen Y, Wang Y, Chen W, Smith M, Huang H, Huang L. The effectiveness of a health education

intervention on self-care of traumatic wounds. J Clin Nurs 2013;22(17-18):2499-508.

4. World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. 2003. www.who.

int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf. Last accessed April 28, 2021.

5. Price P. How can we improve adherence? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016;32(Suppl 1):201-5.

6. Chan L, Lai C. The effect of patient education with telephone follow-up on wound healing in adult

patients with clean wounds: a randomized controlled trial. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;

41(4):345-55.

7. Chisolm A, Hart J, Lam V, Peters S. Current challenges of behavior change talk for medical

professionals and trainees. Patient Educ Couns 2012;87(3):398-94.

8. Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior : reactio ns and reflections. Psychol Healt h 2011;

26(9):1113-27.

9. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav 2004;31(2):143-64.

10. Pignataro R, Huddleston J. The use of motivational interviewing in physical therapy education and

practice: empowering patients through effective self-management. J Phys Ther Educ 2015;29(2):62-71.

11. Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY:

Guilford Press; 2013.

12. Fisher L, Polonsky W, Hessler D, Potter M. A practical framework for encouraging and supporting

positive behavior change in diabetes. Diabet Med 2017;34(12):1658-66.

13. Greene J, Hibbard J, Alvarez C, Overton V. Supporting patient behavior change: approaches used by

primary care physicians whose patients have an increase in activation levels. Ann Fam Med 2016;

14(2):148-54.

14. Welch J. Building a foundation for brief motivational interviewing: communication to promote health

literacy and behavior change. J Contin Educ Nurs 2014;45(12):566-72.

15. Jerant A, Lichte M, Kravitz R, et al. Physician training in self-efficacy enhancing interviewing

techniques (SEE-IT): effects on patient psychological health behavior change mediators. Patient Educ

Couns 2016;99(11):1865-72.

16. Kivela K, Elo S, Kaariainen M. The effects of health coaching on adult patients with chronic diseases:

a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2014;97(2):147-57.

17. Moffatt C, Murray S, Keeley V, Aubeeluck A. Non-adherence to treatment of chronic wounds: patient

versus professional perspectives. Int Wound J 2017;14(6):1305-12.

18. London F. Teaching patients about wound care. Home Healthc Nurse 2007;25(8):497-500.

19. Green L, Ratcliffe D, Masters K, Story L. Educational intervention for nutrition education in patients

attending an outpatient wound care clinic: a feasibility study. J wound Ostomy Continence Nurs

2016;43(4):365-68.

20. Robineau S, Nicolas B, Mathieu L, et al. Assessing the impact of a patient education

programme on pressure ulcer prevention in patients with spinal cord injuries. J Tissue Viability

2019;28(4):167-72.

21. Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society—Wound Guidelines Task Force. WOCN 2016

guideline for prevention and management of pressure injuries (ulcers): an executive summary.

J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(3):241-6.

22. Latimer S, Chaboyer W, Gillespie B. Patient participation in pressure injury prevention: giving patient’s

a voice. Scand J Caring Sci 2014;28(4):648-56.

23. McInnes E, Chaboyer W, Murray E, Allen T, Jones P. The role of patients in pressure injury

prevention: a survey of acute care patients. BMC Nurs 2014;13(1):41.

24. McDermott M, Mandapat A, Moates A, et al. Knowledge and attitudes regarding cardiovascular

disease risk and prevention in patients with coronary or peripheral arterial disease. Arch Intern Med

2003;163(18):2157-62.

25. Bonham P, Flemister B, Droste L, et al. 2014 guideline for management of wounds in patients with

lower-extremity arterial disease (LEAD): an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs

2016;43(1):23-31.

26. Kelechi T, Johnson J, WOCN Society. Guideline for the management of wounds in patients with

lower-extremity venous disease: an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012;

39(6):598-606.

27. Aweko J, De Man J, Absetz P, et al. Patient and provider dilemmas of type 2 diabetes

self-management: a qualitative study in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities in Stocklolm.

Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15(9):1810.

28. King D, Glasgow R, Toobert D, et al. Self-efficacy, problem solving, and social-environmental support

are associated with diabetes self-management behaviors. Diabetes Care 2010;33(4):751-3.

For more th an 158 additional continuing professional development articles related to Skin and Wound Care topics,

go to NursingCenter.com/CE.

CME

Nursin

g

Continuin

g

Professional Develo

p

men

t

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION INFORMATION FOR PHYSICIANS

Lippincott Continuing Medical Education Institute, Inc., is accredited by the

Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide

continuing medical education for physicians.

Lippincott Continuing Medical Education Institute, Inc., designates

this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category

1Credit

TM

. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with

the extent of their participation in the activity.

PROVIDER ACCREDITATION INFORMATION FOR NURSES

Lippincott Professional Development will award 2.5 contact hours for this

continuing nursing education activity.

LPD is accredite d as a pro vider of nurs ing continui ng prof essional dev elopment

by the American Nurses Crede ntialing Center's Commission on A ccredit ation.

This activity is also provider approv ed by the California Board of Registered

Nursing, Provider Number CEP 11749 for 2.5 contact hours . LPD is also an

appro v ed provider of continuing nursing education by the District of Columbia,

Georgia, and Florida CE Brok er #50-1223. Your certificate is valid in all states.

OTHER HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

This activity provides ANCC credit for nurses and AMA PRA Category 1

Credit

TM

for MDs and DOs only. All other healthcare professionals

participating in this activity will receive a certificate of participation that

may be useful to your individual profession's CE requirements.

CONTINUING EDUCATION INSTRUCTIONS

• Read the article beginning on page 403. For nurses who wish to take the

test for NCPD contact hours, visit www.NursingCenter.com/ce/ASWC. For

physicians who wish to take the test for CME credit, visit http://cme.lww.

com. Under the Journal option, select Advances in Skin and Wound Care

and click on the title of the CE activity.

• You will need to register your personal CE Planner account before taking

online tests. Your planner will keep track of all your Lippincott Professional

Development online NCPD activities for you.

• There is only one correct answer for each question. A passing score for

this test is 7 correct answers. If you pass, you can print your certificate of

earned contact hours or credit and access the answer key. Nurses who fail

have the option of taking the test again at no additional cost. Only the first

entry sent by physicians will be accepted for credit.

Registration Deadline: July 31, 2023 (physicians); June 7, 2024 (nurses).

PAYMENT

The registration fee for this CE activity is $24.95 for nurses; $22.00 for

physicians.

ADVANCES IN SKIN & WOUND CARE • AUGUST 2021 410 WWW.ASWCJOURNAL.COM

Copyright © 2021 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.