School Leadership Review School Leadership Review

Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 4

2013

Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public

Schools Schools

Gary Bigham

West Texas A&M University

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr

Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, and the Elementary and Middle and Secondary

Education Administration Commons

Tell us how this article helped you.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Bigham, Gary (2013) "Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public Schools,"

School

Leadership Review

: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 4.

Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted

for inclusion in School Leadership Review by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information,

please contact [email protected].

5

Framework for Understanding the

Legal Structure of Texas Public Schools

Gary Bigham

i

West Texas A&M University

“Politics is a fact of life in all organizations, and schools are no exception” (Ramsey,

2006, p. 79). By their very nature, public schools cannot help but have a strong political

dimension. Schools operate under a legal structure where policy is adopted by the school

board whose membership is elected by the registered voters residing within the school

district boundaries. The development of school district policies and associated decisions

therein are largely impacted by federal and state laws. Those in power in the executive,

legislative, and judicial branches of federal and state governments were either elected to

their respective positions by the general voting public or appointed by elected officials.

Many of their actions ranging from the drafting and enactment of bills into law to

decisions rendered through judicial processes, affect school district policies, either

directly or indirectly, and consequently have an impact on the structure and operation of

Texas public schools.

Ramsey (2006) said, “Wherever there are leaders and followers, there is politics” (p. 79).

Elected and appointed officials at the federal, state, and local levels pass laws and adopt

policies shaping the legal structure and thus impacting the behaviors and actions of the

roughly 4.8 million students and 660,000 faculty and staff in Texas public schools (TEA,

2010). In accordance with Ramsey’s (2006) observation, the presence of politics is

glaringly obvious.

Problem

Texas public school stakeholders consist primarily of students, parents, faculty and staff,

administrators, school board members, business leaders, community members, and

taxpayers. While each of these stakeholders has a vested interest in the local school

district, many fail to understand how public schools came into existence and the legal

rationale upon which they operate. The problem lies in the structural complexity of

schools, which is prohibitive to a complete understanding by its entire constituency.

While the multiple layers of politics and numerous laws and policies that define the

Texas public school structure may be necessary for proper operation, the intricacy further

exacerbates the ability of many to fully comprehend it. The purpose of this study was to

create a framework for understanding the legal structure of Texas public schools to

facilitate a more complete understanding by all constituents.

i

Dr. Gary Bigham may be reached at gbi[email protected].

1

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013

6

Legal Perspective

The framework developed in this study examined the Texas public school structure from

a legal perspective. The legal perspective is grounded in the sources of law, which were

ultimately used as variables for analysis. Sources of law may be viewed categorically as

constitutional, statutory, administrative, and judicial law (Walsh, Kemmerer, & Maniotis,

2005). Moreover, these four sources of law exist at the federal and state levels with the

addition of administrative law which is also found at the local level (Hoyle, Bjork,

Collier, & Glass, 2005; Walsh, Kemmerer, & Maniotis, 2005).

The first source of law referenced in this study is constitutional law and it exists at both

the federal and state levels. Constitutional law is derived from the Constitution of the

United States and, in this Texas specific study, the Texas Constitution of 1876. For

purposes of hierarchical layering, constitutional law trumps all other sources of law and

state constitutional law is subordinate to federal constitutional law.

By definition, “a statute is a law enacted by a legislative body” (Walsh, Kemmerer, &

Maniotis, 2005, p. 2), and statutory law is the second source of law in this study. With

respect to statutory law, the legislative bodies of interest in this study are the U.S.

Congress and the Texas Legislature. Statutory law is the product of the actions of the

U.S. Congress and the Texas Legislature in passing bills into law at the federal and state

levels respectively.

The third source, administrative law, “consists of the rules, regulations, and decisions that

are issued by administrative bodies to implement state and federal statutory laws”

(Walsh, Kemmerer, & Maniotis, 2005, p. 3). Those administrative bodies are present at

the federal, state, and local levels. Examples of these administrative bodies include, at the

federal level, the United States Department of Education; at the state level, the State

Board of Education (SBOE), the Texas Education Agency (TEA), and the Texas

Commissioner of Education; and at the local level, the Board of Trustees of a school

district.

Judicial law serves as the final source of law in this study. Judicial law develops from

decisions yielded by state and federal courts. As a result of disputes arising under

constitutions, statutes, and administrative laws, the courts have the final say. Decisions

handed down from the judicial system sometimes have associated school district policy

implications (Walsh, Kemmerer, & Maniotis, 2005).

Review of Literature

With this study purporting to analyze the legal structure of Texas public schools, the

appropriate focus of the literature review is on their legal and structural aspects. Given

that Texas public schools are governmental agencies directed by elected officials

(Vornberg & Harris, 2010) adopting policies in response to state and federal laws enacted

2

School Leadership Review, Vol. 8 [2013], Iss. 1, Art. 4

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

7

by elected members of the U.S. Congress and Texas Legislature, the political aspects

must be intermingled into the discussion. Alexander and Alexander (2009) eloquently

said,

Because a public school is a governmental agency, its conduct is

circumscribed by precedents of public administrative law supplemented by

those legal and historical traditions surrounding an educational organization

that is state established, yet locally administered. In this setting, legal and

educational structural issues that define the powers to operate, control, and

manage the schools must be considered. (pp. 1-2)

The fundamental principles of legal control for the establishment and structure of Texas

public schools are prescribed by the constitutional system from which the basic organic

law emanates: the U.S. Constitution of 1787 and the Texas Constitution of 1876

(Alexander & Alexander, 2009; Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005). “Constitutions at

both levels of government are basic because the positive power to create public

educational systems is assumed by state constitutions, and provisions of both the state

and federal constitutions serve as restraints to protect the people from the unwarranted

denial of basic constitutional rights and freedoms” (Alexander & Alexander, 2009, p. 2).

The power of operation of the public educational system, therefore, originates with a

constitutional delegation to the legislature to provide for a system of education. With

legislative enactments providing the basis for public school law, it then becomes the role

of the courts, through litigation, to interpret the will of the legislature. (Alexander &

Alexander, 2009, p. 2)

Thus, the combination of constitutions, statutes, administrative law, and judicial

law forms the primary legal foundation upon which the public schools are based

(Alexander and Alexander, 2009; Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005).

“In legal theory, public schools exist not only to confer benefits on the individual but

also, just as importantly, to advance civil society, for which they are necessary, indeed

essential” (Alexander & Alexander, 2009, p. 27). This explains the extensive

involvement of all levels of government in developing, implementing, and enforcing

laws, policies, rules, and regulations that shape the Texas public school structure.

“During the 1760s and 1770s, the idea developed that there should be a free system of

education that would provide for a general diffusion of knowledge, cultivate new

learning, and nurture the democratic ideals of government” (Alexander & Alexander,

2009, p. 23). Following the long struggle for public schools in the nineteenth century, “it

became clear that the states must require rather than permit localities to establish free

schools. Local control of education gradually became limited by state constitutions and

by actions of state legislatures.” (Alexander & Alexander, 2009, p. 27).

3

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013

8

Today, Texas public school districts may be viewed as extensions of state government.

Whereas the U.S. Constitution, through the Tenth Amendment, reserves education as a

state function, the Texas Constitution authorizes the Legislature to enact a system of

public education. As such, the state of Texas has assumed the responsibility for the

structure and operation of the public school system to ensure the education of all students

in the state (Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005). This results in extensive federal, state,

and local political processes impacting the structure of Texas public schools through a

legal avenue.

Method

Considering the historical nature of the laws that have shaped the structure of Texas

public schools, i.e., the U.S. Constitution of 1787 (U.S. Const.) and the Texas

Constitution of 1876 (Tex. Const.), the historic research methodology was employed.

“Historical research helps educators understand the present condition of education by

shedding light on the past” (Gall, Borg, & Gall, 1996, p. 643). More specifically,

quantitative methods of content analysis were used in the data collection process because

it is “a research technique for the objective, systematic, and quantitative description of

the manifest content of communication” (Berelson, 1952, p. 18).

The primary data for this study were legal documents and administrative agency literature

and materials that were directly related to the structure of Texas public schools. These

documents included the Constitutions of the United States and Texas; statutory laws

related to education as codified in the United States Code and the Texas Education Code;

administrative laws as reflected in such documents as Attorney General opinions, rules

and regulations of the United States Department of Education as outlined in documents

such as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and No Child Left Behind policies,

Texas education rules as compiled in the Texas Administrative Code, and school district

policies as assembled in the Texas Association of School Boards (TASB) Policy On-Line

structure. While the document review was not exhaustive, in terms of compiling all laws

related to the Texas public school structure, it served as an overall comprehensive review

of the major levels of legal authority as categorized by the four major sources of law.

The data organizational scheme was both categorical and hierarchical. The categorical

organization separated the findings into the four sources of law—constitutional, statutory,

administrative, and judicial. The hierarchical organization distributed the four categories

of legal findings into the federal, state, and local levels of authority. The desired outcome

was a display of data in columns by sources of law and in rows by levels of authority.

This resulted in a table to serve as a framework for understanding the structure of Texas

public schools from a legal perspective.

4

School Leadership Review, Vol. 8 [2013], Iss. 1, Art. 4

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

9

Results

Through detailed narrative description, the findings revealed the federal, state, and local

levels of the Texas public school structure as categorized by the four identified sources of

law. The narrative descriptions ultimately led to the development of a table for a concise

presentation of the findings in an easily understandable format.

Constitutional Law

Constitutional law, as it relates to the structure of Texas public schools, originates from

two sources, those being the U.S. Constitution and the Texas Constitution. Both

Constitutions are documents of delegated powers which are responsible for laying the

legal foundation upon which the structure of Texas public schools was built.

U.S. Constitution. The U.S. Constitution is organized into seven Articles and twenty-

seven Amendments. Although education is not specifically mentioned anywhere in the

U.S. Constitution, the authority for public schools across the nation is rooted in the

plenary power granted in the Tenth Amendment. The Tenth Amendment states, “the

powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the

States, are reserved to the States respectively or to the people” (U.S. Const. amend.10).

The education literature is replete with references verifying that the Tenth Amendment is

the foundational legal basis for the nation’s current structure of education (Alexander &

Alexander, 2009; Barron Ausbrooks, 2010a; Brimley & Garfield, 2008; Walsh, Kemerer,

& Maniotis, 2005).

Texas Constitution. The Tenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution granted the power

over schools to the state governments (Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005). “Acting

under the interpretation of the Tenth Amendment, all of the states through their

constitutions have taken on education as a state function” (Barron Ausbrooks, 2008, p. 5).

The Texas Constitution is organized into seventeen Articles with Article 7 pertaining

directly to education. Article 7 of the Texas Constitution is further divided into twenty

sections (Tex. Const., art. 7). The legal basis for the current structure of Texas public

schools may be found in Article VII, § 1 of the Texas Constitution of 1876, which reads,

A general diffusion of knowledge being essential to the preservation of the

liberties and rights of the people, it shall be the duty of the Legislature of

the State to establish and make suitable provisions for the support and

maintenance of an efficient system of public free schools. (Tex. Const., art.

7, § 1)

Thus, the U.S. Constitution, through the Tenth Amendment, reserves education as a state

function and in turn, the Texas Constitution authorized the state Legislature to enact a

system of public education.

5

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013

10

Statutory Law

“The public schools of the United States are governed by statutes enacted by state

legislatures. The schools have no inherent powers, and the authority to operate them must

be found in either the express or implied terms of statutes” (Alexander & Alexander,

2009, p. 3). Statutory law, otherwise known as legislative law (Barron Ausbrooks,

2010a), as it applies to the structure of Texas public schools, may be found at both the

federal and state levels.

Statutes, in our American form of government, are the most viable and

effective means of making new law or changing old law. Statutes enacted at

the state or federal level may either follow custom or forge ahead and

establish new laws that shape the future. (Alexander & Alexander, 2009, p.

2)

Federal statute. Federal statutory laws are enacted by the U.S. Congress. The

Congressional Record contains the full text of federal statutes, which are codified and

published in the United States Code (Barron Ausbrooks, 2010b). “The Congressional

Record is the official record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress

and is published daily when Congress is in session” (GPO Access, 2010a).

The United States Code is the codification by subject matter of the general

and permanent laws of the United States based on what is printed in the

Statutes at Large. The United States Code (USC) is divided by broad

subjects into 50 titles and published by the Office of the Law Revision

Counsel of the U.S. House of Representatives. (GPO Access, 2010c)

Title 20 of the USC contains all of the education-related federal statutes. As of

February 1, 2010, Title 20 contained 78 chapters beginning with § 1 and ending

with § 9882 (Cornell University Law School, 2010).

State statute. “The Texas Legislature, acting pursuant to the Tenth Amendment to the

U.S. Constitution and Article VII of the Texas Constitution, is responsible for the

structure and operation of the Texas public system” (Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005,

p. 13). In fact, Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis (2005) went so far as to say that the

Legislature is the “biggest player in Texas education” (p. 13).

Most of the state statutory laws directly relating to education, passed by the Texas

Legislature, are codified in the Texas Education Code (TEC). Walsh, Kemerer, &

Maniotis (2005) said, “The Code is an important source of law because it applies to the

daily operation of schools, detailing the responsibilities and duties of the State Board of

Education (SBOE), the Texas Education Agency (TEA), and school boards, charter

schools, and school personnel” (p. 4).

6

School Leadership Review, Vol. 8 [2013], Iss. 1, Art. 4

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

11

The Texas Education Code is comprised of six titles and nine subtitles. Title 1 contains

the general provisions of the code that apply to all educational institutions receiving state

tax funds. Public education is addressed in Title 2, followed by higher education in Title

3. The focus of Title 4 is on educational compacts. Title 5 is reserved for “other

education,” which, as of the date of this study, pertained to driver and traffic safety

education. Lastly, Title 6 centers on benefits consortiums for certain private educational

institutions (TEC §§ 1.001 – 2000.004).

Specific to the state-level statutory legal structure under which Texas public schools

operate is Title 2 of the Texas Education Code, titled “Public Education.” Title 2 is

divided into subtitles A through I that contain §§ 4 - 46. The major topics of the subtitles

are (a) General Provisions, (b) State and Regional Organization and Governance, (c)

Local Organization and Governance, (d) Educators and School District Employees and

Volunteers, (e) Students and Parents, (f) Curriculum, Programs, and Services, (g) Safe

Schools, (h) Public School System Accountability, and (i) School Finance and Fiscal

Management.

Administrative Law

Administrative law, sometimes coined executive law (Barron Ausbrooks, 2010a),

consists of the rules, regulations, procedures, guidelines, and decisions, developed and

issued by government agencies and associated administrative bodies to implement federal

and state statutory laws as well as the rules and regulations that federal, state, and local

agencies establish to carry out their responsibilities. The regulations designed by the

implementing agencies applying laws to the realities of day-to-day schooling are

typically quite detailed to the point that their length often exceeds that of the statute itself

(Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005). Administrative law is present at the federal, state,

and local levels.

Administrative law in the Texas education structure assumes both quasi-legislative and

quasi-judicial roles. The Texas Commissioner of Education and the State Board of

Education enact state-level rules that are codified in the Texas Administrative Code, thus

operating in a quasi-legislative capacity. Similarly, boards of education for local school

districts adopt policies, as authorized in state statute, representing the law of the school

district. To exhaust all remedies before going to court, local school districts have policies

and procedures in place for administrators and the school board to hear grievances from

complainants. Likewise, procedures are in place for appeals to be heard by the

Commissioner of Education. These local- and state-level hearing processes serve as

examples of the quasi-judicial character assumed by administrative law (Walsh, Kemerer,

& Maniotis, 2005).

7

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013

12

Federal administrative law. Education-related federal administrative law may be found

in the form of presidential proclamations and executive orders, U.S. Attorney General

opinions, and federal-level regulatory agency policies, rules, and regulations. While the

actions of various federal agencies may impact education, the largest player in this arena

is logically the U.S. Department of Education. Short descriptions of these three major

administrative law making bodies follow.

At the upper-most level of the executive branch of the federal government, the President

of the United States is granted the authority and responsibility for developing rules,

regulations, guidelines, procedures, etc., for implementing federally sponsored and

financed programs. Furthermore, the President is authorized to issue proclamations and

executive orders to gain compliance with the U.S. Constitution and federal laws.

Presidential proclamations and executive orders are documented in the Federal Register

(Barron Ausbrooks, 2010a) and accessible at the Presidential Actions Briefing Room

online at http://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions.

Pursuant to the Judiciary Act of 1789, the U.S. Attorney General renders opinions on

questions of law at the request of the President and the heads of Executive Branch

departments (USDOJ, 2010). Moreover, the U.S. Attorney General functions as a legal

adviser to the President and delegates to the Office of Legal Counsel the responsibility of

reviewing all executive orders and proclamations issued by the President (USDOJ, 2010).

While presidential proclamations and executive orders and U.S. Attorney General

opinions may not usually directly address education, the potential is always present, thus

warranting attention as presented in this section of the study.

“The U.S. Department of Education is a cabinet-level agency of the federal government

that establishes policy for, administers, and coordinates many of the educational

programs created and funded by Congress” (Barron Ausbrooks, 2010a, p. 9). The U.S.

Department of Education

assists the President in executing national policies and implementing laws

enacted by Congress. The officials of the Department of Education also

have the authority and responsibility, as do the officials of other cabinets

and agencies of the federal government, for drafting regulations, guidelines,

and procedures to implement federal laws that create and fund federal

programs. Once drafted, the regulations are submitted to the appropriate

congressional committees for approval and are then published in the

Federal Register. They are eventually inserted into the Federal

Administrative Code and carry the weight of administrative law.

(Ausbrooks, 2010b, p. 102)

The U.S. Department of Education is led by the Education Secretary who is advised by

multiple offices hierarchically placed beneath the Office of the Secretary. The

8

School Leadership Review, Vol. 8 [2013], Iss. 1, Art. 4

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

13

organizational structure of the U.S. Department of Education displayed at

http://www2.ed.gov/about /offices/or/index.html. Codified U.S. Department of Education

policies, rules, and guidelines are located in the Code of Federal Regulations (GPO

Access, 2010b) and are posted the Department of Education website at

http://www2.ed.gov/policy/landing.html.

State administrative law. Education-related state administrative law may be found in the

form of governor’s proclamations and executive orders, Texas Attorney General

opinions, and state-level regulatory agency policies, rules, and regulations. Major state-

level boards, agencies, and individuals include the State Board of Education, the Texas

Education Agency, and the Texas Commissioner of Education. Descriptions of these

major administrative law making bodies follow.

In a similar fashion to the powers of the President at the federal level, the Texas governor

is authorized to issue proclamations and executive orders (Barron Ausbrooks, 2010a),

some of which can and do directly affect education. These proclamations and executive

orders are recorded in the Texas Register (Tex. Reg., 2010) and are accessible for

viewing on the Texas Governor’s website at http://governor.state.tx.us/news/.

The Texas Attorney General renders legal opinions that sometimes impact education in

the state, and is another source of state-level administrative law.

State agencies or their officials can request an attorney general’s advisory

opinion whenever they are confronted with novel or unusually difficult

legal questions. Although the attorney general’s opinions are not legally

binding either on the governmental officials, agencies requesting them, or

on the courts, they carry a great deal of influence, especially in those

situations in which there is no authoritative interpretation or decision by the

courts. (Barron Ausbrooks, 2010a, p. 11)

As extensions of the state, school districts “may request the assistance of the attorney

general on any legal matter” (TEC § 11.151(e)). In requesting such opinions, requesters

do so knowing that “an Attorney General Opinion is a written interpretation of existing

law” (Attorney General, 2010). Moreover,

Attorney General Opinions clarify the meaning of existing laws. They do

not address matters of fact, and they are neither legislative nor judicial in

nature. That is to say, they cannot create new provisions in the law or

correct unintended, undesirable effects of the law. Opinions interpret legal

issues that are ambiguous, obscure, or otherwise unclear. Attorney General

Opinions do not reflect the AG’s opinion in the ordinary sense of

expressing his personal views. Nor does he in any way “rule” on what the

law should say.

9

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013

14

Unless or until an opinion is modified or overruled by statute, judicial

decision, or subsequent Attorney General Opinion, an Attorney General

Opinion is presumed to correctly state the law. Accordingly, courts have

stated that Attorney General Opinions are highly persuasive and are entitled

to great weight. Ultimate determination of a law’s applicability, meaning or

constitutionality is left to the courts. (Attorney General, 2010)

Texas Attorney General Opinions are recorded in the Texas Register (Tex. Reg., 2010)

and are accessible for viewing on the Texas Attorney General’s website at

https://www.oag.state.tx.us/opin/.

The State Board of Education (SBOE) is an elected body of fifteen members (TEC §

7.101(a)) who perform school district- or regional education service center-related duties

as assigned by the Texas Constitution or the Legislature (TEC § 7.102(a)). Prior to 1995,

the SBOE was the policy-making body of the TEA, however, the Texas Legislature

separated them from the TEA at that time and reduced their role in the state’s public

education system (Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005). Nonetheless, the SBOE remains a

powerful entity in the state’s education structure engaging in administrative law

processes. Statutorily, the SBOE is assigned a list of thirty-four specific powers and

duties to be carried out with the advice and assistance of the Texas Commissioner of

Education (TEC § 7.102(b-c)). Actions of the SBOE are recorded in the Texas Register

and rules and adoptions are codified in the Texas Administrative Code.

The Texas Education Agency (TEA) is comprised of the Commissioner of Education and

agency staff (TEC § 7.002(a)).

This hierarchical administrative governmental structure is authorized to

implement, administer, and regulate the state-mandated educational

function in the local school districts of the state. An important part of its

responsibility is to make rules and regulations governing education in the

state, which are compiled in the official state publication, Title 19

Education, Texas Administrative Code. (Barron Ausbrooks, 2010a, p. 23)

Statutorily, the TEA is assigned a list of fourteen specific educational functions (TEC §

7.021(b)). Additionally, the TEA is authorized to enter into agreements with federal

agencies regarding such activities as school lunches and school construction (TEC §

7.021(c)), and the TEA administers the capital investment fund (TEC § 7.024). Adopted

rules of the TEA are codified in the Texas Administrative Code.

The Texas Commissioner of Education is appointed, and may be removed, by the

governor with the advice and consent of the Texas Senate (TEC §§ 7.051, 7.053). The

commissioner, whose only statutory qualification for office is to be a U.S. citizen (TEC §

10

School Leadership Review, Vol. 8 [2013], Iss. 1, Art. 4

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

15

7.054), serves a four year term commensurate with the governor (TEC § 7.052) as the

educational leader of the state (TEC § 7.055(b)(1)). Additionally, the commissioner

serves as executive officer of the agency and executive secretary of the SBOE (TEC §

7.055(b)(2)). Touted as the most powerful state-level player other than the Texas

Legislature (Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005), the commissioner has forty-one powers

and duties assigned in state statute (TEC § 7.055). Other sections of the code assign

additional duties with regard to accountability and low-performing schools (TEC §§

39.151-39.152).

When authorized to develop and implement rules, which is a quasi-legislative function of

administrative law, the Commissioner of Education engages in such activity and those

rules governing Texas education are recorded in the Texas Register and codified in the

Texas Administrative Code. As a quasi-judicial act, the Commissioner of Education

renders decisions to appeals in accordance with provisions outlined in TEC §7.057 that

become administrative law. These decisions are catalogued and searchable by docket

number, petitioner, and respondent or hearing officer on the TEA website at

http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/commissioner/.

Local administrative law. The governmental unit at the local school district level is the

elected board of trustees. School districts function as legal extensions of the state, thus

making them quasi-municipal corporations, and “their boards of trustees are considered

state officials with specific administrative duties, responsibilities, and functions mandated

by law” (Barron Ausbrooks, 2010a, p. 23). While many of the policies adopted by local

school boards may be in direct response to actions of the legislature, judicial law

decisions, etc., the desire of the Texas Legislature was for the school board to maintain a

level of power, as is revealed in the language used in TEC §7.003, which states, “An

educational function not specifically delegated to the agency or the board [SBOE] under

this code is reserved to and shall be performed by school districts or open enrollment

charter schools.”

Although school board members have no power as individuals, as a body corporate,

convened in a legally called meeting, their power, under the auspices of administrative

law, is quite evident. TEC §11.151(b) states:

The trustees as a body corporate have the exclusive power and duty to

govern and oversee the management of the public schools of the district.

All powers and duties not specifically delegated by statute to the agency or

to the State Board of Education are reserved for the trustees, and the agency

may not substitute its judgment for the lawful exercise of those powers and

duties by the trustees.

In general, in the name of the school district, the board of trustees, as a body corporate,

may “acquire and hold real and personal property, sue and be sued, and receive bequests

11

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013

16

and donations or other moneys or funds coming legally into their hands” TEC

§11.151(a). Specific powers and duties of boards of trustees of independent school

districts are listed in TEC §11.1511(b) by way of a list of fifteen items of what the board

shall do, and in TEC §11.1511(c) by way of a list of four items of what the board may do.

Regarding the administrative law function of school boards, Walsh, Kemerer, and

Maniotis (2005) said, “The policy manuals and handbooks developed by local school

districts are excellent close-to-home examples of administrative law” (p. 4). Furthermore,

TEC §11.151(d) states, “The trustees may adopt rules and bylaws necessary to carry out

the [their] powers and duties”—an obvious administrative law capacity.

The school district administrators are responsible for implementing the policies adopted

by the board of trustees. Ausbrooks (2010a) said, “the district superintendent and campus

principals function as extensions of the local school board through the general duties and

authority granted to them through TEC §11.201 and §11.202” (p. 23).

“The superintendent is the educational leader and the chief executive officer of the

school district” (TEC §11.201(a)) with a list of fifteen statutorily assigned duties

outlined in TEC §11.201(d). “The school principal is the frontline administrator,

with statutory responsibility under the direction of the superintendent for

administering the day-to-day activities of the school” (Walsh, Kemerer, &

Maniotis, 2005, p. 27). TEC §11.202(a) identifies the principal as the instructional

leader of the school, and TEC §11.202(b) lists seven statutory duties of the

principal. School administrators implement policies adopted by the school board

through rules, regulations, and directives. These methods of policy implementation

represent the law of the district, thus serving in the capacity of administrative law

(Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005).

Lastly, each Texas school district and campus is required to have district- and campus-

level planning and decision-making committees (TEC §11.251(b)), commonly referred to

as site-based decision making committees. These committees are involved in the

development of the district- and campus-level improvement plans (TEC §§ 11.252(a);

11.253(c)). The campus-level committees are statutorily directed to be involved in the

areas of planning, budgeting, curriculum, staffing patterns, staff development, and school

organization (TEC § 11.253(e)). While their role is mostly advisory in nature, the

campus-level decision making committee has statutory approval power over the staff

development portion of the improvement plan (TEC § 11.253(e)), thus qualifying them

for involvement in this legal structure discussion.

Judicial Law

“When disputes arise under constitutions, statutes, and administrative law, some authority

must have final say. The courts serve this function” (Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005,

p. 6). The judicial court systems are present at both the federal and state levels. In most

12

School Leadership Review, Vol. 8 [2013], Iss. 1, Art. 4

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

17

instances, until all administrative remedies have been exhausted, the courts refuse to

become involved (Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005). When such involvement is

inevitable,

The courts have traditionally maintained and enforced the concept of

“separation of powers” when confronted with cases involving education.

They do not usually question the judgment of either the administrative

agencies of the executive branch or the legislative branch. (Alexander &

Alexander, 2009, p. 3)

“The courts presume that legislative or administrative actions were enacted

conscientiously with due deliberation and are not arbitrary or capricious” (Alexander &

Alexander, 2009, p. 4).

In the big picture, both judiciary systems begin at a district court level and offer avenues

for an initial appeal at an appellate court level and a final appeal at a supreme court level.

The final level of appeal is at the U.S. Supreme Court whose final ruling serves as the

law of the land.

Federal judicial law. Disputes involving federal provisions of the U.S. Constitution,

federal statutes, or federal treaties may be tried in the federal judicial court system. For

questions on federal law, once all administrative remedies have been exhausted, the

dispute may enter the federal judicial system at the U.S. District Court level.

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the federal court

system. Within limits set by Congress and the Constitution, the district

courts have jurisdiction to hear nearly all categories of federal cases,

including both civil and criminal matters. (U.S. Courts, 2010a)

“There are 94 federal judicial districts, including at least one district in each state, the

District of Columbia and Puerto Rico” (U.S. Courts., 2010a).

Four of those 94 U.S. District Courts are located in Texas. Texas was divided into four

regions—Northern, Southern, Eastern, and Western—to prescribe their respective

geographic jurisdiction areas across the state. Decisions of U.S. District Courts are

appealable to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals within its geographical region.

Geographically across the United States of America,

The 94 U.S. judicial districts are organized into 12 regional circuits, each of

which has a United States court of appeals. A court of appeals hears appeals

from the district courts located within its circuit, as well as appeals from

decisions of federal administrative agencies. (U.S. Courts, 2010b)

13

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013

18

Cases appealed from one of the four U.S. District Courts in Texas go to the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals which has jurisdiction in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. The Fifth

Circuit Court has seventeen authorized judgeships and is physically located in New

Orleans, LA (Structure of the U.S. Government, 2010).

While decisions of a U.S. Court of Appeals are appealable to the United States Supreme

Court, such appeals are rarely granted (Barron Ausbrooks, 2010), as “the U.S. Supreme

Court has the authority to decide which cases it wishes to hear” (Walsh, Kemerer, &

Maniotis, 2005, p. 8).

The United States Supreme Court consists of the Chief Justice of the United

States and eight associate justices. At its discretion, and within certain

guidelines established by Congress, the Supreme Court each year hears a

limited number of the cases it is asked to decide. Those cases may begin in

the federal or state courts, and they usually involve important questions

about the Constitution or federal law. (U.S. Courts, 2010c)

Nonetheless, “education in the United States has, of course, been materially shaped by

many Supreme Court decisions that emanate from individual rights recognized in the

Constitution” (Alexander & Alexander, 2009, p. 103).

The typical path by which a Texas-based federal case would reach the U.S. Supreme

Court would be by beginning in one of the four Texas-located U.S. District Courts, being

appealed to the 5

th

Circuit Court of Appeals, and being appealed to and accepted by the

U.S. Supreme Court. In some instances, cases with federal questions heard in the Texas

Supreme Court may be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

State judicial law. The Texas judiciary consists of multiple layers that permit entry at

one of three levels depending on the nature and origination of the dispute. The first level

of the Texas judiciary involves justice and municipal courts, the second level involves the

county court, and the third level represents the state district court. While smaller-level

disputes involving matters of education may originate at a justice, municipal, or county

court, “district courts are the major trial courts in the state judicial system, having

jurisdiction over major criminal and civil matters” (Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005,

pp. 7-8). Moreover, Walsh, Kemerer, and Maniotis (2005) claimed that

Regardless of whether litigation is filed initially in a state district court or

as an appeal from a decision of the commissioner, the state court system

plays an important role in the resolution of educational disputes. Therefore,

it is important to review the composition of the Texas judiciary. (p. 7)

14

School Leadership Review, Vol. 8 [2013], Iss. 1, Art. 4

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

19

Since the State District Court is a logical starting point for litigation in most educational

disputes beyond levels of administrative law, the ensuing discussion of movement

through the state court system will begin at the district court level.

The district courts are the trial courts of general jurisdiction of Texas. The

geographical area served by each court is established by the Legislature, but

each county must be served by at least one district court. In sparsely

populated areas of the State, several counties may be served by a single

district court, while an urban county may be served by many district courts.

District courts have original jurisdiction in all felony criminal cases,

divorce cases, cases involving title to land, election contest cases, civil

matters in which the amount in controversy (the amount of money or

damages involved) is $200 or more, and any matters in which jurisdiction is

not placed in another trial court. While most district courts try both criminal

and civil cases, in the more densely populated counties the courts may

specialize in civil, criminal, juvenile, or family law matters. (Office of

Court Administration, 2009)

While the number of state district courts in Texas is too numerous to list, a map of their

locations is available at http://www.courts.state.tx.us/courts/pdf/sdc2009.pdf.

Decisions rendered by the district courts are appealable to one of the state’s fourteen

Courts of Appeal. The locations of the appeals courts by district are 1. Houston, 2. Fort

Worth, 3. Austin, 4. San Antonio, 5. Dallas, 6. Texarkana, 7. Amarillo, 8. El Paso, 9.

Beaumont, 10. Waco, 11. Eastland, 12. Tyler, 13. Corpus Christi and Edinburg, and 14.

Houston. These fourteen appeals courts are manned with eighty justices.

In essence, Texas has two supreme courts—one for civil matters and the other for

criminal matters (Walsh, Kemerer, & Maniotis, 2005). At the top of the Texas judiciary

hierarchy, the Texas Supreme Court, comprised of nine justices, serves as the final

appellate jurisdiction for all state-level civil and juvenile cases. The final state-level

appellate jurisdiction for all criminal cases is the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, which

is comprised of nine judges (Texas Courts Online, 2011).

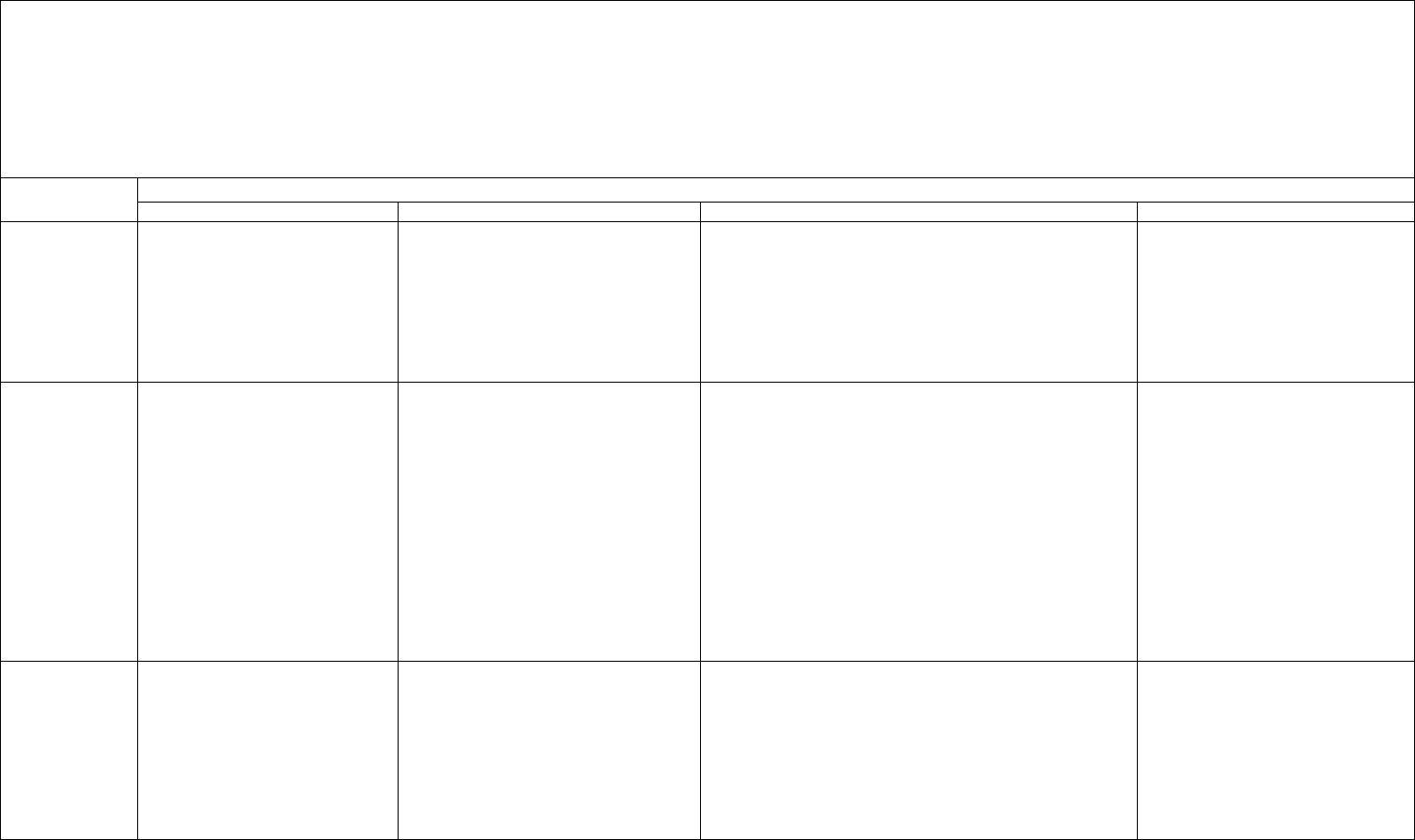

The goal at the outset of this study was to capture all of the information that has been

presented in this findings section and compile it into a one-page summary. In pulling key

information reported in the narrative and diagrammatical data reported in this section of

this study, a celled table was created to capture the entire legal structure of Texas public

education onto a single page. The data reflected in the rows and columns of Table 1 refer

to the structure upon which Texas public schools were developed and currently operate.

The data in each cell of Table 1 reveal the type of law and its documented location. For

example, rules developed by the Texas Education Agency in response to statutes enacted

by the Texas Legislature are compiled in the Texas Administrative Code. The Texas

15

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013

20

Education Agency (TEA) rules are appropriately categorized as administrative law and

hierarchically are a state-level function. Thus, the information provided in the cell reveals

that TEA rules are documented in the Texas Administrative Code and that cell is located

at the intersection of the administrative law column and the state-level of authority row.

Each cell in Table 1 provides pertinent information specific to the intersection of its level

of authority and source of law.

Discussion

The framework developed in this study has educational implications applicable to a wide

range of Texas public school stakeholders. The stakeholders of particular interest to

whom the framework should prove valuable include school board members, faculty and

staff, parents, taxpayers, and the business community. Of those stakeholders, probably

the group who most needs to understand the findings presented in this study is the board

of trustees. As the body corporate elected to oversee the management of the school

district, an understanding of the legal framework under which the school structure is

defined becomes essential. The framework developed in this study could serve as a model

for board training as school board members seek to meet state-mandated professional

development requirements. With the exception of administrators, most faculty and staff

have little or no training in school governance, and thus may have a void in their

knowledge base about the structure of Texas public schools. In a manner similar to that

mentioned for school board members, the framework could serve as a basis for

professional development of the faculty and staff employed in Texas public schools.

When parents sometimes question the decisions made by the school, administrators could

use the model as a tool in explaining why certain rules and procedures are in place in

relation to laws and policies. In a similar sense, when taxpayers question the reasons for

expenditures, the framework could prove useful in showing how certain legal

requirements necessitate particular expenditures. With regard to the business community,

sometimes something as simple as making a donation to the school can be difficult due to

laws and policies that were developed to protect the school and its employees. Again, the

framework could serve as a tool in assisting the business community to understand the

purpose of certain policies and the legal path by which they came into existence. Other

audiences that could benefit from the framework might include politicians at federal,

state, and local levels, and students of school law would certainly benefit as well. The

much needed framework developed in this study concisely organizes the legal structure

of Texas public schools and should prove to be useful in a variety of settings.

16

School Leadership Review, Vol. 8 [2013], Iss. 1, Art. 4

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

Table 1. Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public Schools.

Levels of

Authority

Sources of Law

Constitutional Law

Statutory Law

Administrative Law

Judicial Law

Federal

Authority for public education

reserved to the states as

determined by the framers of the

U.S. Constitution and specified

in the Tenth Amendment.

Education-related federal statutes

enacted by U.S. Congress are

recorded in the Congressional Record

and codified in the United States

Code.

Proclamations & executive orders issued by the President

are recorded in the Federal Register.

U.S. Attorney General Opinions rendered by the Office of

Legal Counsel are recorded in the Federal Register and

published in West Law and LEXIS.

United States Dept. of Education policies, rules, and

regulations are recorded in the Federal Register and

codified in the Code of Federal Regulations.

Sources of federal court decisions

specific to Texas include:

U.S. District Court

*Northern, Southern, Eastern,

Western districts (in Texas)

U.S. Court of Appeals

*5

th

Circuit, New Orleans, LA

U.S. Supreme Court

State

Authorization for the Legislature

to enact a system of public

education as established by the

framers of the Texas

Constitution and specified in

Article 7 § 1.

Education-related state statutes

enacted by the Texas Legislature are

recorded in the Texas Register and

codified in the Texas Education Code.

Proclamations & executive orders issued by the Governor

are recorded in the Texas Register.

Texas Attorney General Opinions are recorded in the Texas

Register.

State Board of Education Rules are recorded in the Texas

Register and codified in the Texas Administrative Code.

Texas Education Agency Rules and Regulations are

recorded in the Texas Register and codified in the Texas

Administrative Code.

Commissioner’s Rules are recorded in the Texas Register

and codified in the Texas Administrative Code.

Commissioner’s Hearing Decisions are recorded and

accessible from the TEA website at

http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/commissioner/.

Sources of state court decisions

specific to Texas include:

Justice & Municipal Courts

County Courts

State District Courts

State Intermediate Appellate

Courts (14 districts)

Supreme Court (civil) and Court

of Criminal Appeals (criminal)

Local

School Board Policies adopted by the Board of Trustees

are recorded in the school board minutes and codified in

Local School Board Policy.

Local School Administrative rules, regulations, and

directives are developed and implemented by, or under the

direction and supervision of the school administration.

Site Base Management approval of staff development

needs on the improvement plan are documented in the

SBM minutes.

Framework for Understanding the Legal

Structure of Texas Public Schools

Developed by Dr. Gary Bigham

17

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013

22

References

Alexander, K. and Alexander, M. D. (2009). American Public School Law (7

th

ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Attorney General of Texas (2010). About Attorney General Opinions. Retrieved

from https://www.oag.state.tx.us/opin/

Barron Ausbrooks, C. Y. (2008). Organizational structure and the role of

government in Texas public education. In J. A. Vornberg & L. M. Garrett

(Eds.), Texas public school organization and administration: 2008 (11

th

ed.,

pp. 3-35). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt.

Barron Ausbrooks, C. Y. (2010a). The organizational structure of government and

its role in Texas public education. In J. A. Vornberg & L. M. Garrett (Eds.),

Texas public school organization and administration: 2010 (12

th

ed., pp. 3-

45). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt.

Barron Ausbrooks, C. Y. (2010b). Federal government involvement in education.

In J. A. Vornberg & L. M. Garrett (Eds.), Texas public school organization

and administration: 2010 (12

th

ed., pp. 3-45). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt.

Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Glencoe, IL:

Free Press.

Brimley, V., and Garfield, R. R. (2008). Financing education in a climate of

change (10

th

ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Cornell University Law School (2010). U.S. Code. Retrieved from

http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/20/usc_sup_01_20.html

GPO Access (2010a). Congressional Record: Main Page. Retrieved from

http://www.gpoaccess.gov/crecord/index.html

GPO Access (2010b). Code of Federal Regulations (CFR): Main Page. Retrieved

from http://www.gpoaccess.gov/cfr/

GPO Access (2010c). United States Code: About. Retrieved from

http://www.gpoaccess.gov/uscode/about.html

Gall, M. D., Borg, W. R., and Gall, J. P. (1996). Educational research: An

introduction. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Hoyle, J. R., Björk, L. G., Collier, V., & Glass, T. (2005). The superintendent as

CEO: Standards-based performance. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Office of Court Administration (2009). The Texas Judicial System. Austin, TX.

Retrieved from www.courts.state.tx.us

Ramsey, R.D. (2006). Lead, follow, or get out of the way: How to be a more

effective leader in today’s schools (2

nd

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Structure of the United States Government (2010). U.S. Courts of Appeals.

Retrieved from http://www.theusgov.com/courtsofappeals.htm

TEC §§ 1.001 – 2000.004.

18

School Leadership Review, Vol. 8 [2013], Iss. 1, Art. 4

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/slr/vol8/iss1/4

23

Texas Courts Online (2011). Welcome to Texas Courts Online. Retrieved from

http://www.courts.state.tx.us/

Texas Education Agency. (2010). 2009-10 State Performance Report. Austin, TX:

TEA Division of Performance Reporting. Retrieved from

http://ritter.tea.state.tx.us/perfreport/aeis/2010/state.html

Texas Register (2010). Vol. 35, No. 48, pp. 10363-10560, Nov. 26, 2010.

Retrieved from http://www.sos.state.tx.us/texreg/pdf/currview/1126is.pdf

Tex. Const.

Tex. Const., art. 7.

Tex. Const., art. 7, § 1.

United States Department of Justice (2010). Opinions. Retrieved from

http://www.justice.gov/olc/opinions.htm

United States Courts (2010a). Court of Appeals. Retrieved from

http://www.uscourts.gov/FederalCourts/UnderstandingtheFederalCourts/Cou

rtofAppeals.aspx

United States Courts (2010b). District Courts. Retrieved from

http://www.uscourts.gov/FederalCourts/UnderstandingtheFederalCourts/Dist

rictCourts.aspx

United States Courts (2010c). Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved from

http://www.uscourts.gov/FederalCourts/UnderstandingtheFederalCourts/Supr

emeCourt.aspx

U.S. Const.

U.S. Const., amend. 10.

Vornberg, C., and Harris, S. (2010). The changing local school district. In J. A.

Vornberg & L. M. Garrett (Eds.), Texas public school organization and

administration: 2010 (12

th

ed., pp. 27-45). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt.

Walsh, J., Kemerer, F., and Maniotis, L. (2005). The educator’s guide to Texas

school law (6

th

ed.). Austin, TX: University Press.

Walsh, J., Kemerer, F., and Maniotis, L. (2010). The educator’s guide to Texas

school law (7

th

ed.). Austin, TX: University Press.

19

Bigham: Framework for Understanding the Legal Structure of Texas Public S

Published by SFA ScholarWorks, 2013