FINANCIAL RISKS DUE TO

LONG-TERM CARE

August 15, 2016

Constantijn W.A. Panis, PhD

Advanced Analytical Consulting Group, Inc.

213-784-6400

Michael J. Brien, PhD

Deloitte Transaction and Business Analytics LLP

202-378-5096

i

SUMMARY

This report characterizes the current landscape and outlook of long-term care

utilization, its costs, and its financing through out-of-pocket payments, private

insurance, and public insurance. We draw on academic and trade literature and

present new statistics based on primary research. In particular, we analyze cost

reports of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), Form 5500 Annual Return/Report of

Employee Benefit Plan (“Form 5500”) filings, and the Health and Retirement Study

(HRS).

Approximately one-half of Baby Boomers are projected to require paid, formal long-

term care in the home, an adult day care center, an assisted living facility, or a

nursing home. Paying for care out of pocket will rapidly exhaust retirement savings

of many Americans, forcing them to eventually rely on Medicaid. Indeed, more than

one-half of nursing home patients who have been resident for five years or longer

are Medicaid beneficiaries. The size of the Baby Boom generation is expected to drive

up demand for and prices of long-term care, creating a troublesome outlook for the

elderly’s personal finances and the Medicaid program.

In light of the strained finances of Medicaid and other public payors, potential

solutions will likely involve expanded private insurance. At present, only about 7

million Americans are covered by long-term care insurance. We discuss several

options for reducing risks for insurers and consumers alike, public-private

partnerships which incentivize private insurance, and policy options to promote long-

term care insurance benefits in the workplace. However, fundamental economic

interactions between private insurance and the Medicaid program pose a challenge to

simultaneously preserving a safety net for low-income Americans and ensuring fiscal

sustainability of the Medicaid program.

ii

CONTENTS

Abbreviations ................................................................................................ ii

1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 3

2. Literature and External Statistics on Utilization and Costs ....................... 3

3. Cost Reports of Skilled Nursing Facilities ................................................. 9

4. Long-Term Care Insurance ..................................................................... 11

State Medicaid Partnership Programs .......................................................... 15

Employer-Provided Long-Term Care Benefits ................................................ 16

5. Analysis of Health and Retirement Study Data ....................................... 18

6. Policy Implications ................................................................................. 26

References .................................................................................................. 28

Appendix A. Median Prices of Long-Term Care Services, by State (2015) ... 31

Appendix B. Sample Long-Term Care Insurance policy ............................... 33

Disclaimer ................................................................................................... 37

ABBREVIATIONS

AALTCI American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance

ADL Activity of Daily Living

BLS Bureau of Labor Statistics

CBO Congressional Budget Office

CMS Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

HIPAA Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

HCRIS Healthcare Cost Report Information System

HRS Health and Retirement Study

IADL Instrumental Activity of Daily Living

LTC Long-term care

LTCI Long-term care insurance

LTSS Long-term services and support

NAIC National Association of Insurance Commissioners

NCHS National Center for Health Statistics

SNF Skilled Nursing Facility

3

1. INTRODUCTION

Caring for the elderly and the disabled in the United States is posing increasingly

large financial risks for patients, their family, and the Medicaid and Medicare

programs. Medical costs have outpaced general inflation over the past four decades

(BLS 2016) and retiring Baby Boomers are expected to increase demand for long-

term care (LTC) services.

This report documents long-term care utilization, costs, and financing mechanisms,

and reviews policy options for addressing long-term care’s financial risks. We draw

on a variety of sources including external literature and primary analyses of the cost

reports of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), Form 5500 Annual Return/Report of

Employee Benefit Plan (“Form 5500”) filings, and the Health and Retirement Study

(HRS).

Mirroring the gradual increase in need for assistance as the body ages, long-term

care encompasses a range of services. Much of it is non-medical in nature, such as

assistance with cleaning, shopping, bathing, dressing, or eating. Services may be

provided in the home by relatives or friends, homemakers, or home health aides; at

adult day care centers; at assisted living facilities; at hospices, or at nursing homes.

1

Given the wide range of services, some authors refer to long-term care as long-term

services and support (LTSS). This document uses the two terms interchangeably.

The remainder of this report is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes academic

and trade literature and provides external national statistics on long-term care

utilization and costs. Section 3 adds to these statistics from our own analysis of

annual cost reports that skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) submit to the Medicare

program of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Section 4

discusses trends in long-term care insurance (LTCI) and its typical features. It also

includes our analysis of Form 5500 filings to shed a light on employer-sponsored

long-term care insurance. Section 5 presents our analysis of HRS data with respect

to long-term care utilization and its financial consequences. Section 6 concludes with

a discussion of policy implications.

2. LITERATURE AND EXTERNAL STATISTICS ON

UTILIZATION AND COSTS

In the United States, long-term care services are provided informally, by family and

friends, and formally, by about 12,200 home health agencies, 4,800 adult day

services centers, 22,200 assisted living and similar residential care communities,

15,700 nursing homes, and 3,700 hospices (NCHS 2013). On a typical day in 2011

or 2012 (NCHS 2013), approximately:

1

This document uses the terms Skilled Nursing Facility and nursing home

interchangeably. Some authors make a distinction, where SNFs are certified and

covered by Medicare and offer skilled medical and rehabilitative services, whereas

nursing homes offer custodial care. Typically, facilities offer both types of services.

4

4.7 million patients received services from home health agencies,

273,000 participants were enrolled in adult day services centers,

713,000 residents were living in residential care communities,

1.4 million residents were living in nursing homes, and

1.2 million patients received services from hospices.

Demand for LTC services in the United States is expected to grow substantially in the

coming decades, largely due to the aging of the population and increased prevalence

of disability among middle-aged populations. These factors increase the share of the

population that has functional limitations and may require assistance performing

everyday activities. The baby-boom generation, a cohort of 75 million individuals,

was born between 1946 and 1964. In 2016 the oldest baby-boomers are turning 70

years old, and by 2031, they will turn 85 years old. The aging of this generation is

causing significant shifts in the age distribution of the population (CBO 2013). In

2000, the share of the U.S. population that was 65 or older was 12%, but by 2050

that share is expected to exceed 20%. Over the same time period, the share of the

population age 85 or older is expected to grow from 1.5% to 4.1%. Functional

limitations and disability tend to increase with age. For example, from 2000 to 2010,

18% of 65-74 year olds living in the community reported difficulty performing

Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs),

while 54% of those aged 85 or older reported difficulties performing at least one of

these (CBO 2013).

2

Similarly, the Census Bureau (2012) found that, excluding those

in nursing homes, the fraction of people reporting needing assistance with activities

of daily living increased with age from 7% among 65-69 year-olds to 30% among

people age 80 or older (Table 1). As noted in their report, the magnitude of disability

estimates would likely be higher if the nursing home population were included.

Table 1. Disability Prevalence and the Need for Assistance among the Non-

Institutionalized Population by Age, 2010

2

ADLs include bathing, dressing, eating, walking, transferring out of a bed or a

chair, and using the toilet; IADLs include preparing meals, shopping, using the

telephone, managing money, and taking medications.

Age

Any

disability

Severe

disability

Needs

assistance

Under 15 8.4% 4.2% 0.5%

15 to 24 10.2% 5.3% 1.4%

25 to 44 11.0% 7.3% 2.0%

45 to 54 19.7% 13.8% 3.6%

55 to 64 28.7% 20.4% 6.0%

65 to 69 35.0% 24.7% 6.9%

70 to 74 42.6% 29.6% 10.8%

75 to 79 53.6% 37.5% 15.4%

80 and over 70.5% 55.8% 30.2%

Source: Census Bureau (2012). "Any disability"

indicates difficulty to perform ADLs/IADLs or similar

activities, and "severe disability" indicates inability

to perform such activities. For details see Figure 1 in

Census Bureau (2012).

5

While a general consensus has formed that the health of the elderly improved on

several measures throughout the 1980s and 1990s, there has been a surge in

disability among younger generations, in particular those under 50 years old

(Lakdawalla et al., 2003). While the root causes have not been fully investigated,

there is some evidence that obesity and such chronic illnesses as asthma and

diabetes may be part of the problem.

3

This will likely contribute to an even greater

increase in disability rates and institutionalization in a SNF in the coming decades

than as suggested by projected aging of the population. When analyzing cohorts

aged 65 and older in the late 1990s, Lakdawalla et al. (2004) forecast that the

younger cohorts will likely have a higher rate of disability at older ages than the

older cohorts did. This evidence aligns with increasing levels of disability among 50-

to 59-year olds between 1984 and 1996.

4

The aging of the population and the growth in disability among the middle-aged is

likely to lead to increased future demand for both informal and formal LTC services.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO 2013) estimated that in 2011 the economic

value of informal and formal LTC services for elderly people in the United States was

$426 billion, of which $234 billion (55%) was in the form of informal care.

5

The

remaining $192 billion was spent on institutional care (31% of total) and community-

based care (14% of total).

6

While 31% of the total economic value was in

institutional care, it related to only 18% of elderly people who were receiving LTC

services in 2010. This reflects the high cost of institutional nursing care relative to

community-based care; see Table 4 below. Four-out-of-five (80%) of elderly people

who received LTC services lived in private homes, receiving informal care or

community-based care in the form of home health aides, visits to adult day care

facilities, and other non-institutional care.

Based on a microsimulation of people from around age 65 in 2015 to the end of their

lives, Favreault and Dey (2016) forecast the ADL limitations of future elderly and

their need for long-term care services. The goal of this exercise was to better

understand the near-term future trends in this area and to forecast the average level

of spending required. Specifically, the authors focused on the need for long-term

services and support because of a disability that meets the criteria set in the 1996

3

Other explanations include changes in disability insurance laws (greater incentives

to report disabilities that otherwise went unreported) and technological advances in

medicine (new treatments can delay death for those who are chronically frail and

otherwise would have died at a younger age).

4

The forecasts of Lakdawalla et al. (2003) are not without some controversy.

Manton (2003) argued that the use of certain data and assumptions in Lakdawalla et

al. (2003) resulted in an incorrect conclusion. He expected nursing home use will

continue to decline.

5

The CBO calculated this figure by multiplying the average wage earned by a home

health aide ($21 per hour) by the 11.2 billion hours of donated care extrapolated

from responses to the HRS. It did not account for forgone earnings of the caregiver

in excess of $21 per hour.

6

The CBO defines the economic value of institutional care as the cost of stays,

including room and board as well as assistive services, in skilled nursing facilities,

nursing homes, and nursing facilities housed inside continuing care retirement

communities. It defines the economic value of community-based care as the cost of

assistive services provided in all other settings, including private homes, adult day

care facilities, and facilities that are not nursing homes.

6

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), namely a need for

assistance with at least two ADLs that is expected to last at least 90 days or a need

for substantial supervision for health and safety threats due to severe cognitive

impairment. The study found that 52% of people who turn 65 years old in 2015-

2019 will at some time in their lives need (informal or formal) long-term services and

support because of such a disability. Excluding informal care by relatives or friends,

47% will need formal long-term services and support, including 23% who will need it

for less than one year and 6% who will need it for five years or more (see Table 2).

Including elderly who will not need any formal care, this cohort will need formal

assistance for one year on average. Women are more likely to need assistance than

men (52% versus 42%), people with lower incomes are somewhat more likely to

need assistance than those with higher incomes, and the need for assistance is, as

expected, greater for those in poor health than those in good health at age 65.

Table 2. Projected Use of Paid LTSS for Persons Turning 65 in 2015-2019, by

Gender, Income Quintile and Self-Reported Health Status at Age 65

Favreault and Dey (2016) further projected that formal long-term services and

support will cost an average of $138,100 per person turning 65 in 2015-2019,

expressed in 2015 dollars. This average translates into $266,000 per user of formal

care. Of this amount, community-based care will cost 53% and care at nursing

facilities 47%. Assuming current finance mechanisms, the majority (52%) of formal

long-term services and support is expected to be paid out of pocket. The authors

expect Medicare to pay 10%, Medicaid 34%, and private insurance 3%.

Distribution for all

None <1 year

1.00-

1.99

years

2.00-

4.99

years

>5

years

Gender

Men 0.7 42.0 58.0 22.2 8.5 8.0 3.4

Women 1.3 52.1 47.9 23.1 9.5 11.2 8.3

Income Quintile at Age 65

Lowest 1.2 49.0 51.0 20.7 9.1 11.2 8.1

Second 1.2 48.1 52.0 21.1 8.7 11.0 7.3

Middle 1.1 48.7 51.3 22.5 9.7 9.6 6.8

Fourth 0.9 45.2 54.8 22.7 8.4 8.7 5.4

Highest 0.8 46.3 53.7 24.9 9.2 8.8 3.5

Health Status at Age 65

Excellent 1.0 46.8 53.2 24.0 7.6 9.9 5.4

Very good 0.9 46.1 53.9 23.1 8.7 9.5 4.8

Good 1.1 47.1 52.9 22.1 8.4 10.0 6.6

Fair/poor 1.1 49.0 51.0 22.0 10.8 9.4 6.7

Marital Status at Age 65

Married 0.9 45.8 54.2 23.2 8.6 8.9 5.1

Unmarried 1.2 50.0 50.0 21.5 9.9 11.2 7.5

Total 1.0 47.2 52.8 22.7 9.0 9.7 5.9

Source: Favreault and Dey (2016).

Average

years of

formal LTSS

use

Percent

with any

formal LTSS

use

7

While different sources suggest different payor mixes, financing long-term care at

nursing homes is largely through government-funded Medicaid and Medicare

programs.

7

According to a study by The Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid was the

primary payor for 63% of nursing facility residents in 2011, 14% were primarily

covered by Medicare, and 22% were private payors (Kaiser Family Foundation 2013).

The Kaiser study was based on the Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting

(OSCAR) system, a database that contains detailed information on Medicaid and

Medicare certified nursing facilities. Our own analysis of a different but related data

source, SNF cost reports, suggests that Medicaid was the primary payor for 53% of

resident-days in 2014, Medicare for 13%, and private payors for 34% (see Section

3), with only minor changes in this distribution since 2011.

The daily reimbursement of SNFs by Medicare tends to be higher than that by

Medicaid. Mostly depending on a patient’s care needs, Medicare payments range

from approximately $195 to $803 per day in 2016 (CMS 2015). Medicaid payments

vary by state and are typically a flat rate per day, irrespective of care needs, with

limited adjustments for cost differences across geographies. For example, in Florida

in 2015, the 10

th

and 90

th

percentiles of daily reimbursements were approximately

$203 and $257, respectively (authors’ calculations based on Florida AHCA 2015).

For formal care as a whole, CBO (2013) found that out of the $192 billion in

payments for formal care in 2011, $68 billion was paid through Medicare, $60 billion

through Medicaid, $39 billion was paid out of pocket (including beneficiaries’ cost

sharing for Medicare and Medicaid), and $12 billion was covered through private

insurance. The remaining $12 billion were from such other sources as the

Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and charitable

donations. See Table 3, which also shows the expenditures for community-based and

institutional settings (defined in footnote 6).

Table 3. Expenditures for Long-Term Care Services for Elderly People (2011)

Payors differ in their length of coverage. For example, Medicare and private health

insurance offer short-term coverage for post-acute care rehabilitative services in the

form of nursing home stays and home health visits (about three months coverage or

less). Medicaid and private LTC insurance offer much longer coverage periods (three-

7

Medicare offers limited coverage for skilled nursing care in a SNF. Among other

restrictions, the stay must be preceded by an acute-care hospital stay. If eligibility

conditions are met, Medicare generally pays the full cost for up to 20 days and

requires co-insurance payments of $161 per day (in 2016) for days 21-100. It does

not cover stays beyond 100 days.

Source of payment

Community-Based

($ bn)

Institutional

($ bn)

Total Care

($bn)

Medicare 31 37 68

Medicaid 20 40 60

Out of Pocket 3 36 39

Private Insurance 2 10 12

Other 1 11 12

Total 58 134 192

Source: CBO (2013).

8

to five-year terms) and will cover without a previous acute health episode.

According

to the CBO (2013), the distribution of LTC insurance and Medicaid coverage for the

elderly population living in the community varies by level of disability. Those with

three or more functional limitations are five times more likely to be covered by

Medicaid (24%, on average, from 2000 to 2010) than those with no functional

limitations (5%). While only 5% of those with no functional limitations were Medicaid

beneficiaries, 15% were covered by LTC insurance.

As shown in Table 4, the costs of long-term care can be substantial. The nationwide

median cost of in-home assistance by a homemaker or home health aide was $20

per hour in 2015 (Genworth 2015). Assuming four hours of assistance per day, five

days a week, this amounts to $20,800 annually.

8

The median rate for adult day care

was $69 per day ($17,940 per year at five days per week). An intermediate level of

personal care and health services, less extensive than in a nursing home, is offered

by assisted living facilities, which charge a median of $3,600 per month ($43,200 per

year). Finally, the median cost of nursing homes was $220 per day ($80,300 per

year) for a semi-private room and $250 per day ($91,250 per year) for a private

room. These rates reflect prices that are payable out of pocket or with private

insurance and may differ from those reimbursed by public programs.

Table 4. Nationwide Median Prices of Long-Term Care Services (2015)

According to Genworth (2015), the costs for institutionalized long-term care have

outpaced those for in-home care. From 2010 to 2015, nursing home costs increased

by 3.5%-4.0% annually, compared with 1.0%-1.6% annually for homemakers and

home health aides. Similarly, CBO (2013) reported annual nursing home cost

increases of 4.0%-4.5% between 2002 and 2012, compared with 1.6% annually for

home health aides.

Table 4 displays national median costs, but LTC costs vary widely across states.

Alaska tends to have the highest costs, with the statewide median cost of a private

room in a nursing home exceeding the national median by 208%. Other states with

very high costs include Connecticut (+74%), Massachusetts (+53%), New York

(+50%), and Hawaii (+48%), while relatively low-cost states include Oklahoma

(-34%), Missouri (-33%), Louisiana (-32%), Kansas (-28%), and Arkansas (-28%).

See Appendix A for a list of median LTC prices by state.

8

Home health care is typically provided on a part-time basis. MetLife (2012), which

compiled similar price data as Genworth (2015), assumed four hours per day, five

days per week, 52 weeks per year to annualize its figures.

Rate Annual

Nursing home, private room $250 per day $91,250

Nursing home, semi-private room $220 per day $80,300

Assisted living facility $3,600 per month $43,200

Adult day care $69 per day $17,940

Home health aid care $20 per hour $20,800

Source: Genworth (2015).

Annual rates for home care are based on 4 hours per day,

5 days per week; annual rates for adult day services are

based on 5 days per week.

9

3. COST REPORTS OF SKILLED NURSING FACILITIES

SNFs that participate in the Medicare program are required to annually submit a cost

report to CMS. Among many other items, these cost reports list the number of

resident-days primarily paid for by Medicare, Medicaid, and all other payors

combined (mostly LTC insurance and self-payments). Hospital-based SNFs report on

the cost report of the hospital; freestanding SNFs report on a separate report.

9

Figure 1 shows the number of resident-days reported by all freestanding SNFs in the

United States that participate in the Medicare program. The number of resident-days

is converted into resident-years to show the average number of people who are

resident at SNFs during the year. The number has been fairly stable at approximately

1.35 million from 2008 through 2014.

Figure 1. Number of Resident-Years Reported by Freestanding SNFs, by

Primary Payor and Year

The payor mix has also been fairly stable over this period. Approximately 13% of

resident-days are primarily paid by Medicare, 53% by Medicaid, and 34% by other

payors (Figure 2). These figures relate to resident-days. In terms of dollar

expenditures, CBO (2013) found Medicare paid for 28% of institutional care services,

9

Medicare cost reports are stored in the Healthcare Cost Report Information System

(HCRIS), available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-

Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/Cost-Reports.

Medicare

Medicaid

Other

0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

1.2

1.5

0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

1.2

1.5

Number of resident-years (millions)

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Source: CMS Healthcare Cost Report Information System.

10

Medicaid for 30%, and other sources for 43% (see the second column of Table 3

above).

Figure 2. Distribution of Primary Payor of Resident-Years Reported by

Freestanding SNFs, by Year

Figure 3 shows the average length of stay as reported by freestanding SNFs on their

Medicare cost reports.

10

As expected given Medicare’s coverage of at most 100 days,

the average length of resident stays that were primarily paid by Medicare was

shorter (39 days in 2014) than that of stays primarily paid by Medicaid (460 days in

2014). SNFs are not required to report the average length of stays that were

primarily paid for by private payors. Instead, only the average length of stay across

all primary payors is reported (165 days in 2014). Figure 3 also shows that average

lengths of stay have generally decreased somewhat since 2000.

10

Some SNFs reported implausibly short or long average lengths of stay. We

excluded the bottom and top deciles of average lengths of stay in our calculations.

The averages are weighted by reported number of resident-days.

Medicare

Medicaid

Other

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

200020012002200320042005200620072008200920102011201220132014

Source: CMS Healthcare Cost Report Information System.

11

Figure 3. Average Length of Stay Reported by Freestanding SNFs, by Payor

and Year

4. LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE

As documented above, the cost of long-term care can be substantial. The average

cost for those who are projected to use formal care, $266,000 (Favreault and Dey,

2016), can exhaust the lifetime savings of many retirees. People at the high end of

the income or wealth distributions may be able to self-insure against the financial

risks of long-term care, whereas those at the low end may expect Medicaid to cover

the costs. For Americans in between, private long-term care insurance may provide a

solution.

Currently sold LTCI policies typically offer both home care and nursing home

benefits, but that was not the case for older policies. For example, 63% of policies

sold in 1990 offered nursing home benefits only and 37% offered both home care

and nursing home benefits (Cohen 2016). In 2015, 99% of policies sold offered both

types of benefits. Coverage limits are often anchored on a daily or monthly

maximum for nursing home stays and a lifetime maximum benefit, with maximums

for care outside nursing homes expressed as a percentage of the nursing home

benefit. Appendix B shows key pages from a sample policy published by Genworth.

In that example, the nursing home maximum is $4,000 per month, the residential

care facility benefit maximum is 75% or 100% of $4,000 per month,

11

and the home

11

The policy defines a residential care facility as a state-licensed Residential Care

Facility for the Elderly or similar. Such facilities provide 24-hour care to support

Medicare

Medicaid

Medicare, Medicaid, and Other

0

100

200

300

400

500

Average length of stay (days)

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Source: CMS Healthcare Cost Report Information System.

Average length of stay excluding reports in the bottom and top deciles.

12

and community care benefit maximum is 50% or 100% of $4,000 per month,

12

depending on the generosity of the policy purchased. The total benefit payments are

subject to a lifetime cap of $240,000. Benefit maximums may or may not be

increased over time to protect against inflation. The sample policy shows benefit

increases of 5% per year. Policies are also often subject to an elimination period,

also known as a deductible period. For example, an elimination period of 90 days can

imply that benefits are paid only after 90 days following a first covered expense

while chronically ill.

LTCI policies can be in force for decades. Most policyholders (54%) applied when

they were 55-64 years old, well before they expected to need benefits (AALTCI

2015). Policies are typically guaranteed renewable at an annual premium that is

designed to be constant for the duration of the policy contract, even with annual

benefit increases and even if a claim was made. However, while designed to be

constant for the duration of the contract, the premium may be changed for a variety

of reasons, including actual or estimated experiences of all holders of a particular

policy form. It is our understanding that premium changes require the approval of

state insurance regulators.

Premiums on individual policies may change and indeed they have changed. Most

insurers’ LTCI policies issued before the mid-2000s have seen adverse experience

when compared to their original pricing assumptions. Rising claims, low mortality

and lower than expected lapses have led to higher prices often unaffordable to a

large segment of the affected population (Karapiperis and Nordman, 2016).

According to the chief executive of Genworth Financial, which has a long-term care

insurance market share of roughly 35%, average premium increases of 50% were

needed to break even on policies issued before 2002 (Carrns 2014). State regulators

appear to have been generally receptive to proposed rate increases.

The Federal Long Term Care Insurance Program (FLTCIP) offers voluntary private

LTCI to Federal employees, who are responsible for the full premiums. It, too,

appears to have underestimated the costs of providing benefits. In November 2016,

FLTCIP premiums are scheduled to increase by an average of 83% (Davidson 2016).

Cohen (2016) documented that policies sold in 2015 offered an average daily benefit

amount for nursing homes of $159 and for home care of $152. The lifetime cap

supported, on average 3.8 years of nursing home care. Three-out-of-four policies

featured annual benefit increases to protect against inflation. The average deductible

period was 93 days. The average annual premium was $2,772. The policies generally

appear less generous than those sold during the 1990s. For example, the lifetime

cap in 1990 supported on average 5.6 years of nursing home care, the average

deductible period was 20 days, and the average premium $1,071 (about $1,942 in

2015 dollars).

needs resulting from impairment in ADLs or in cognitive ability, provide three meals

per day, have agreements to ensure that residents receive the medical care services

of a physician or nurse in case of emergency, and meet certain other criteria.

12

Under the sample policy, home and community benefit care benefits include adult

day care, nurse and therapist services, home health care, personal care services,

and homemaker services.

13

Table 5 shows average annual premiums for basic LTC insurance, by age of the

insured at the time the policy was purchased (NAIC 2013). Premiums increase with

age, roughly tripling from $4,349 for people age 50 to $13,500 for those buying at

age 75 for inflation-protected policies with a 4-year maximum benefit period.

Table 5. Average Annual Premium for Basic Long-Term Insurance, $200

Daily Benefit (2013)

Most claimants of LTC benefits are at least in their 80s when they start using covered

services. About 2% are under age 60, 9% are in their 60s, 25% in their 70s, and

64% age 80 or older (AALTCI 2015; see Table 6).

Table 6. Age of Claimant for New Claims Opened (2012)

About one-half of new claimants receive in-home care, one-in-five receive benefits

for assisted living, and about 31% moved into a nursing home (AALTCI 2015; see

Table 7).

Table 7. Newly Opened Long-Term Care Insurance Claims Paid For

According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC 2015), 7.2

million people were covered by LTC insurance in 2014, and the American Association

for Long-Term Care Insurance (AALTCI 2015) estimated that 8.1 million Americans

4 Years of Benefits 6 Years of Benefits Lifetime Benefits

50 $4,349 $5,083 $7,347

60 $5,331 $6,269 $8,927

70 $9,206 $10,549 $15,070

75 $13,500 $15,157 $20,930

4 Years of Benefits 6 Years of Benefits Lifetime Benefits

50 $1,294 $1,514 $1,997

60 $2,057 $2,426 $3,307

70 $4,914 $5,834 $7,777

75 $8,146 $8,291 $12,337

Source: NAIC (2013).

Age When

Buy

With Inflation Protection 5% Compounded Per Year

With No Inflation Protection—Benefit Stays at $200 per Day

Age Percent

Under 50 0.3%

50 to 59 1.9%

60 to 69 8.7%

70 to 79 25.4%

80 and over 63.7%

Source: AALTCI (2015).

Service Percent

Home Care 51.0%

Assisted Living 18.5%

Nursing Home 30.5%

Source: AALTCI (2015).

14

were insured for long-term care in 2014. About 255,000 policyholders were receiving

benefits in 2014 (NAIC 2015).

Perhaps in response to unexpected losses to insurance companies and unexpected

rate increases to consumers, the market landscape for long-term care insurance has

shifted dramatically over the past decade. There is a trend toward smaller daily

benefits, shorter benefit periods (i.e., lower lifetime benefit caps), and less inflation

protection. Many smaller carriers have exited the market (Gleckman 2013, 2015)

and sales of individual LTCI policies plummeted from a high of 754,000 in 2002 to

just 129,000 in 2014 (Cohen 2016). That said, so-called combination or hybrid

products have gained popularity. These products combine LTC benefits with either

life insurance or an annuity. In combination with life insurance, if LTC is needed, the

death benefit is accelerated. In combination with an annuity, if LTC is not needed,

there is an annuity payout. Sales of combination products rose from 273,000 in 2009

to 535,000 in 2013 (Cohen 2016).

In a series of essays, Brown and Finkelstein (2007, 2008, 2009, 2011) addressed the

relatively small size of the market for private LTCI. They pointed out that 35%-50%

of 65 year-olds will use a nursing home at some point in their remaining lives and

that, of those who use a nursing home, 10%-20% will live there more than five

years. At current median prices, five years of nursing home residency cost in excess

of $400,000 (see Table 4 above). Despite a sizable risk of large future expenditures,

private LTCI pays for only 6% of LTC expenses, whereas out-of-pocket payments

account for 20% (see Table 3 above). Brown and Finkelstein evaluated supply and

demand side factors to explain the small role of private LTCI.

Supply side issues are reflected in premiums that far exceed expected benefits and

typical benefits that only partially cover costs. On average, the present value of

benefits is only one-half of the present value of lifetime premiums (Brown and

Finkelstein 2011). Further, while pricing is unisex, men are less likely to incur LTC

expenses than women—men receive benefits of only about 34 cents per premium

dollar, compared with 64 cents received by women. The authors suggest several

supply-side factors that may be responsible for the high premiums and less-than-full

coverage. Among these are transaction and administration costs, lack of a

competitive market, adverse selection and moral hazard, and contracting issues.

Finkelstein and McGarry (2006) found that adverse selection (disproportionate

enrollment by high-risk individuals) and moral hazard (disproportionate utilization by

insured individuals) are offset by a strong taste for insurance among low-risk

individuals. (Our Table 17 below is consistent with that conclusion.) Because of the

very long-term nature of LTCI policies, contracting issues may be particularly

troublesome. While contractually adjustable, premiums are intended to be fixed in

nominal terms for the duration of the policy—typically several decades—even when

benefits are inflated annually. The insurance company may go bankrupt, creating a

risk for the policyholder that benefits may never materialize. Also, the insurance

company may not be able to pool certain risks, such as the risk that prices for long-

term care rise faster than expected or that returns on invested premiums are below

expectations.

However, even if supply side issues could be resolved and premiums would be

actuarially fair, demand side issues likely stand in the way of widespread LTC

insurance. Brown and Finkelstein (2009) cite several demand side issues. First,

consumers may underestimate the risks and costs of long-term care. Second, they

may value consumption when institutionalized less highly than when not, thus

15

reducing the incentive to smooth out consumption through insurance. Third, they

may take into account imperfect but less expensive alternatives to private insurance,

such as care provided by a spouse or other family members, financial transfers from

adult children, or Medicaid. In particular, two aspects of the structure of Medicaid

reduce demand for private LTCI: means-testing and Medicaid being the secondary

payer. Means testing implies that every dollar in private benefits postpones Medicaid

eligibility, and Medicaid being the secondary payer implies that it is not available to

top up private LTCI benefits, which typically cover only part of the costs. Brown and

Finkelstein (2008) calculated the “implicit tax” of Medicaid—the part of the LTCI

premium that goes to pay for benefits that end up duplicating benefits that Medicaid

would have paid for in the absence of a private policy—at 60% for a man at the

median of the wealth distribution. In other words, 60 cents out of every dollar of

private benefits simply serve to replace benefits that Medicaid would have provided.

For women, they estimated the implicit tax rate at 75%.

In short, Brown and Finkelstein argue that supply side issues lift premiums to levels

far above expected benefits and that demand side issues sharply reduce the net

benefits that private insurance will provide.

StateMedicaidPartnershipPrograms

In recent years many states have implemented so-called Partnership Programs

between Medicaid and private insurance companies. These programs are designed to

encourage middle-income Americans to purchase long-term care insurance. To

qualify for basic Medicaid, one generally needs to spend down assets. However,

holders of LTCI policies that meet Partnership criteria may qualify for Medicaid after

their long-term care benefits run out while preserving assets. For example, if a

policyholder needs long-term care after exhausting his lifetime maximum benefit of,

say, $300,000, he may qualify for Medicaid while retaining $300,000 in assets

beyond the usual Medicaid criteria. The California Partnership Program describes the

asset protection aspect as follows (California DHCS 2010; emphasis in original):

Medi-Cal [California’s Medicaid program] Asset Protection is available in

Partnership policies through an alliance between the State of California and

select private insurers who agree to market high-quality long-term care

insurance policies. Asset Protection guarantees you get to keep a dollar's

worth of assets for each dollar your Partnership insurance policy pays out for

long-term care services. If you use up your long-term care insurance

coverage and still need long-term care, you may apply for Medi-Cal. When

qualifying for Medi-Cal, you are entitled to keep assets Medi-Cal normally

allows, plus assets equal to the amount the Partnership policy has paid out in

benefits. This means you can purchase a Partnership policy equal to the

amount of assets you wish to protect. The State of California will also

disregard these protected assets when making a claim through Medi-Cal

Estate Recovery.

As of March 2014, 44 states and the District of Columbia had implemented a

Partnership Program. State requirements for policies to meet Partnership standards

vary, but most require inflation protection through benefits that increase

automatically over time. With the exception of California, Partnership states allow

reciprocity, i.e., they grant asset exemptions based on Partnership policies that were

16

purchased under another state’s Partnership Program (New York SPLTC 2016,

AALTCI 2016a).

By 2015, Partnership policies accounted for slightly more than two-in-five new

policies sold (Cohen 2016).

Employer‐ProvidedLong‐TermCareBenefits

Long-term care insurance coverage may be obtained through individual policies or

through employer-sponsored group policies. NAIC (2015) documented that by the

end of 2014, 7.2 million lives were covered by LTCI. Of these, 5.0 million (69%)

were individual policies and 2.2 million (31%) were certificates under group plans.

13

The National Compensation Survey indicates that 18% of civilian workers had access

to long-term care insurance through their employer (NCS 2014). In other words, the

employers of 18% of civilian workers sponsored a long-term care insurance benefit.

Although sponsored by the employer, benefits are typically fully paid for by the

employee. From the employee’s point of view, the main advantages of an employer-

sponsored plan are potential group discounts and, for larger groups, often simplified

medical underwriting (such as without a medical examination). After separating from

their employer, the policy certificate stays with the employee.

Take-up rates are very low, with different sources reporting estimates from 5%-7%

of eligible employees taking up long-term care insurance (CIPR 2016; Pincus et al.,

2013).

We conducted an analysis of Form 5500 filings to gain insights into the prevalence of

employer-sponsored long-term care coverage. The Employee Retirement Income

Security Act (ERISA) requires any administrator or sponsor of an employee benefit

plan subject to ERISA to annually report details on such plans unless exempt from

filing pursuant to regulations issued by the DOL. Welfare plans with fewer than 100

participants are generally exempt, except if they operate a trust. For the purpose of

this report, only plans with 100 or more participants are included. Non-ERISA plans,

such as governmental plans and church plans, do not need to file a Form 5500 and

are not covered by the analysis in this section.

The Form 5500 does not ask specifically about long-term care benefits. Line 8b on

the main Form asks for the plan’s benefit types, but there is no code for long-term

care benefits. Details about underlying insurance contracts, if any, are reported on

Schedules A. Line 8 of the Schedule A asks for the benefit type of the insurance

contract, but, again, there is no checkbox for long-term care benefits. However,

plans may check “Other” and write in the appropriate benefit type. We searched

these free-form text boxes for such phrases as “long-term care” and “LTC”. In recent

years roughly 2,000 plans annually indicated offering LTC benefits; see Table 8.

14

13

Technically, most employer-sponsored plans are not group plans but multi-life

policies, i.e., individual long-term care insurance policies bundled together with a

group discount (AALTCI 2016b).

14

Since these figures originate from Schedules A, they exclude long-term care

benefits offered by employers that self-insure those benefits. We are unaware of the

prevalence of self-insured long-term care benefits.

17

Table 8. Employer-Provided Long-Term Care Coverage and Annual Premiums

Table 8 suggests that the number of plans that offer LTC benefits has increased over

time, but it is unclear to what extent the increase is due to more-complete reporting.

The number of “covered persons” under the reported insurance contracts has been

between approximately 950,000 and 980,000 in 2011-2014, which corresponds to

1.3%-1.4% of all welfare plan participants.

15

As noted earlier in this section, the

number of group LTCI certificates is about 2.2 million (NAIC 2015), suggesting that

employer-sponsored long-term care insurance benefits are underreported on Form

5500 filings.

Table 8 also shows the average and median annual premium that the employer

reported paying for LTC benefits. The average annual premium in 2014 was $883

and the median was $661. These figures are well below average premiums in the

individual market (see Table 5), possibly in part because of the age composition of

plan participants, because of coverage limits, or because of discontinuation rates

upon job separation.

15

The number of covered persons is taken from Line 1e of Schedule A and the

number of welfare plan participants from Line 6d on the main Form. Some

companies file a single Form 5500 for all their welfare benefits, whereas others file

multiple Forms 5500. To prevent double counting of welfare plan participants, we

included only a single welfare plan filing per employer (as identified by Employer

Identification Number, EIN), namely the plan with the greatest number of

participants.

Year

Number of

plans

Number of

covered plan

participants

Percent of all

welfare plan

participants

Average annual

premium per

person covered

Median annual

premium per

person covered

2000 315 419,843 0.90% $575 $401

2001 523 466,378 0.72% $572 $399

2002 634 516,516 0.78% $726 $405

2003 735 618,056 0.95% $788 $430

2004 957 692,110 1.02% $631 $461

2005 1,112 735,044 1.06% $690 $497

2006 1,286 859,595 1.20% $769 $521

2007 1,409 863,228 1.18% $662 $553

2008 1,568 924,364 1.25% $665 $541

2009 1,693 829,086 1.19% $838 $597

2010 1,826 922,303 1.30% $787 $626

2011 1,918 949,141 1.33% $802 $603

2012 2,019 975,785 1.35% $858 $632

2013 2,029 982,826 1.36% $851 $638

2014 2,037 954,836 1.30% $883 $661

Source: Form 5500 filings for welfare plans with 100 or more participants.

18

5. ANALYSIS OF HEALTH AND RETIREMENT STUDY

DATA

For an analysis of the financial consequences of long-term care, we turn to the HRS.

The HRS is a longitudinal survey of Americans over the age of 50, and their spouses.

It collects information about health, certain types of health care utilization (including

home health care and nursing home stays), informal care by relatives, insurance

coverage, out-of-pocket medical expenses, assets, and income. The HRS sample is

drawn from the non-institutionalized population, but respondents are followed even if

they move into a nursing home or other health care facility.

16

Since most

respondents enter the survey when they are 51 to 61 years old, the exclusion of

institutionalized individuals from its sampling frame is presumably not a major

limitation.

The HRS started in 1992 with a sample of individuals aged 51-61, and their spouses.

Insofar possible, they have been re-interviewed every other year. In 1993, a cohort

of individuals age 70 and older, and their spouses, was added to the HRS. Insofar

possible, they were re-interviewed in 1995, 1998, and every other year thereafter.

In 1998, 2004, and 2010 new cohorts of individuals aged 51-61, and their spouses,

were added. Therefore, the age distribution was unusual in the early years of the

HRS, but the sample became more representative of the older population in later

years. To mitigate effects of an incomplete age distribution, we present results based

on the 1998 and later waves only. Our analysis incorporates HRS waves through

2012. The sample size is approximately 17,000-22,000 respondents (12,000-15,000

households) per wave.

Table 9 shows the distribution of HRS respondents by age and sex, for the eight

waves from 1998 to 2012. Approximately 59% of respondents are women. Most

respondents are in their 50s or 60s, but 20% are in their 70s, 11% in their 80s, and

2% are age 90 or older.

Table 9. Distribution of Respondents by Age and Sex

16

The HRS uses the following definition: “A nursing home or other health facility

provides all of the following services for its residents: dispensing of medication, 24-

hour nursing assistance and supervision, personal assistance, and room & meals”

(see Section A of HRS questionnaires, such as the 2012 version at

http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/2012/core/qnaire/online/01hr12A.pdf).

Female Male Total

Age Freq. Percent Freq. Percent Freq. Percent

<50 4,128 0.1% 1,060 0.0% 5,188 0.1%

50-59 23,302 33.8% 16,304 36.8% 39,606 35.1%

60-69 27,409 29.6% 21,353 32.4% 48,762 30.9%

70-79 22,107 21.3% 17,616 20.4% 39,723 20.9%

80-89 12,371 12.6% 7,744 9.1% 20,115 11.0%

90+ 2,963 2.7% 1,174 1.3% 4,137 2.1%

Total 92,280 100.0% 65,251 100.0% 157,531 100.0%

Source: 1998-2012 HRS.

Note: Percentages are weighted.

19

Table 10 tabulates utilization of home health care and nursing homes during the two

years between survey interviews, by year. In this table and subsequent HRS-based

tables, frequency counts reflect the raw number of respondents (possibly in multiple

interview waves) and percentages are weighted by respondent weights.

17

Roughly

7%-8% of respondents had utilized home health care and 4% had stayed at least

one night in a nursing home. In addition, the last two columns show that roughly 2%

of respondents were resident at a nursing home at the time of the survey.

Table 10. Utilization of Home Health Care and Nursing Homes in the Past 2

Years, Nursing Home Residency at the Time of the HRS Interview, by Year

Similar to Table 10, Table 11 tabulates utilization of home health care and nursing

homes during the two years between survey interviews, but by age of the

respondent rather than by year. As expected, use of LTC services increased with age.

Table 11. Utilization of Home Health Care and Nursing Homes in the Past 2

Years, Nursing Home Residency at the Time of the HRS Interview, by Age

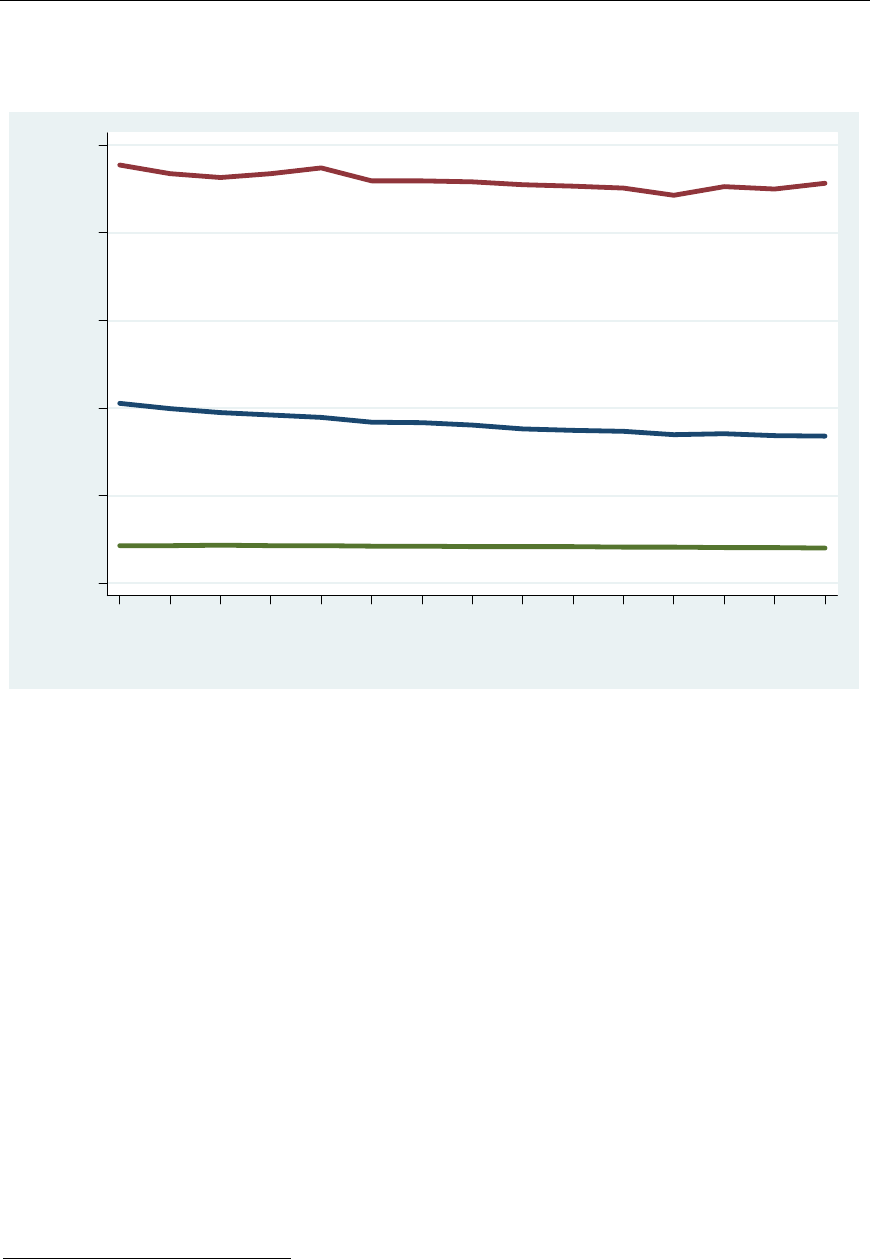

Figure 4 and Table 12 show the prevalence of LTC insurance among HRS

respondents aged 51-69. LTC insurance coverage has remained approximately

unchanged at about 9%-10% since 2002. A small fraction of policies cover in-home

17

Regular respondent weights are zero for institutionalized respondents. From 2000-

2010, the HRS provided respondent weights for institutionalized respondents. Where

available, we used such institutional weights. Where unavailable, we imputed

weights based on respondent weights in prior or subsequent interview waves.

Year

Utilized Home

Health Care

Stayed in

Nursing Home

Institutionalized

at Interview

1998 7.1% 3.0% 1.8%

2000 6.5% 3.7% 2.5%

2002 6.8% 4.4% 2.4%

2004 5.9% 3.4% 1.9%

2006 7.1% 4.0% 1.9%

2008 7.5% 4.0% 1.9%

2010 7.9% 3.7% 1.4%

2012 7.9% 4.2% 1.8%

Total 7.1% 3.8% 1.9%

Source: 1998-2012 HRS.

Age

Utilized Home

Health Care

Stayed in

Nursing Home

Institutionalized

at Interview

<50 1.0% 1.1% 0.0%

50-59 3.2% 0.6% 0.1%

60-69 5.4% 1.6% 0.6%

70-79 9.6% 4.6% 1.9%

80-89 16.6% 13.5% 7.5%

90+ 29.3% 31.3% 22.5%

Total 7.1% 3.8% 1.9%

Source: 1998-2012 HRS.

20

care or nursing home care only, but most cover both. This is consistent with Cohen

(2016).

Figure 4. Prevalence and Type of Long-Term Care Insurance

(Respondents Aged 51-69 in 1998-2012)

Table 12. Prevalence and Type of Long-Term Care Insurance

(Respondents Aged 51-69 in 1998-2012)

As documented by Cohen (2016) and discussed on page 11 above, currently sold

policies tend to cover both in-home and nursing home care, but older policies were

more restrictive. Recognizing that older policies tend to be held by older birth

cohorts, Table 13 shows benefit types by age of the HRS respondent. About 87%

(9.8%/11.2%) of policies held by 60-69 year-olds covered both in-home and nursing

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012

Source: HRS respondents age 51-69

Other

In-home care only

Nursing home care only

Both

Year

Nursing Home

and Home Care

Nursing Home

Care Only

Home

Care Only Other Total

1998 6.0% 1.1% 0.8% 0.1% 8.0%

2000 6.6% 0.7% 0.6% 0.0% 7.9%

2002 8.1% 0.9% 0.3% 0.2% 9.5%

2004 8.6% 0.7% 0.4% 0.1% 9.9%

2006 8.7% 0.6% 0.3% 0.0% 9.6%

2008 9.5% 0.7% 0.3% 0.1% 10.6%

2010 8.9% 0.6% 0.3% 0.1% 9.8%

2012 8.8% 0.6% 0.4% 0.0% 9.8%

Source: HRS Respondents aged 51-69.

21

home care. That fraction decreases with age to 81% among 70-79 year-olds, 69%

among 80-89 year-olds, and 57% among respondents age 90 or older.

Table 13. Prevalence and Type of Long-Term Care Insurance, by Age (1998-

2012)

Table 14 and Table 15 show the distribution of cumulative number of days spent in a

nursing home, by age of the respondent.

18

The days may have been spent

consecutively or over multiple nursing home stays. Table 14 shows the distribution

for the individual respondent. Most people never stayed in a nursing home, but the

fraction who did increases, as expected, with age. Among respondents who are age

90 or older, 11% had stayed 1-30 days, 6% 31-100 days, 6% 101 days to one year,

5% more than one year but less than two years, 10% two to four years, and 2% five

years or longer. Table 15 is similar to Table 14 but accounts for nursing home stays

of both the respondent and his or her partner.

Table 14. Cumulative Duration Spent in a Nursing Home, by Age

18

Cumulative number of days insofar reported in the HRS. Any stays prior to

entering the HRS sample are excluded. However, since most HRS respondents are in

their 50s when they enter the HRS, we believe this limitation to be mild. The tables

uses eight HRS waves (1998-2012), i.e., individual respondents can contribute

multiple times to the tables.

Age

Nursing Home

and Home Care

Nursing Home

Care Only

Home

Care Only Other Total

<50 2.5% 0.0% 1.0% 0.0% 3.5%

50-59 6.9% 0.5% 0.4% 0.1% 7.9%

60-69 9.8% 1.0% 0.4% 0.0% 11.2%

70-79 10.9% 1.9% 0.5% 0.1% 13.4%

80-89 7.8% 2.6% 0.8% 0.1% 11.3%

90+ 4.1% 2.4% 0.5% 0.1% 7.1%

Source: 1998-2012 HRS.

Age

Duration <50 50-59 60-69 70-79 80-89 90+ All

Zero days 98.9% 99.2% 97.3% 92.8% 80.5% 60.3% 94.4%

1-30 days 0.0% 0.5% 1.5% 3.9% 8.4% 11.0% 2.6%

31-100 days 1.1% 0.1% 0.4% 1.3% 3.4% 5.6% 0.9%

101-364 days 0.0% 0.1% 0.3% 0.7% 2.4% 5.9% 0.7%

1 year 0.0% 0.0% 0.1% 0.5% 2.0% 4.8% 0.5%

2-4 years 0.0% 0.0% 0.2% 0.7% 2.8% 10.2% 0.8%

5+ years 0.0%0.0%0.1%0.1%0.5%2.3%0.2%

Source: 1998-2012 HRS.

22

Table 15. Cumulative Duration Spent in a Nursing Home by Self or Partner,

by Respondent Age

Table 16 shows the fraction of individuals who reported Medicaid enrollment, by

duration spent in a nursing home. As expected, the longer someone was a resident

at a nursing home, the more likely he or she was receiving Medicaid benefits. More

than one-half (56%) of respondents who had spent five years or longer in a nursing

home reported Medicaid enrollment, compared with only 8% among those who had

never stayed in a nursing home. A likely explanation is that private assets and other

sources of payment become sufficiently depleted for a respondent to become eligible

for Medicaid.

Table 16. Medicaid Enrollment by Cumulative Duration Spent in Nursing

Home

Table 17 shows utilization of long-term care by age and by long-term care insurance

status. Table 11 above already showed that use of services increases with age; Table

17 documents that utilization among people with insurance is generally lower that

among their uninsured counterparts. Theoretically, adverse selection and moral

hazard could lead to the opposite pattern: people who expect to need long-term care

are more likely to purchase insurance protection, and people with insurance

coverage are more likely to use services because the net cost is lower for them.

However, for long-term care utilization those forces are outweighed by such other

factors as better health among LTCI policyholders. This finding is consistent with

Finkelstein and McGarry (2006), who concluded that in the market for long-term care

insurance individuals with a strong taste for purchasing insurance tend to be low-risk

and outnumber individuals with private information that they are high-risk.

Age

Duration <50 50-59 60-69 70-79 80-89 90+ All

Zero days 98.3% 98.6% 95.7% 89.0% 74.3% 54.8% 92.1%

1-30 days 0.0% 0.9% 2.4% 5.9% 11.0% 12.6% 3.8%

31-100 days 1.3% 0.2% 0.7% 2.0% 4.7% 6.7% 1.4%

101-364 days 0.4% 0.2% 0.5% 1.2% 3.3% 6.8% 1.0%

1 year 0.0% 0.0% 0.2% 0.6% 2.4% 5.2% 0.6%

2-4 years 0.0% 0.1% 0.4% 1.1% 3.7% 11.3% 1.0%

5+ years 0.0%0.0%0.1%0.2%0.6%2.7%0.2%

Source: 1998-2012 HRS.

Durat ion

Medicaid

Enrollment

Zero days 7.6%

1-30 days 11.7%

31-100 days 14.8%

101-364 days 26.1%

1 year 30.9%

2-4 years 37.4%

5+ years 55.9%

Total 8.7%

Source: 1998-2012 HRS.

23

Table 17. Utilization of Long-Term Care, by Age and LTC Insurance Status

The HRS does not ask about out-of-pocket expenses related to nursing home stays.

In an attempt to gauge the financial consequences of nursing home stays, Table 18

captures asset depletion between HRS interviews for households with and without

nursing home stays. The unit of analysis is a household interview that was preceded

by another interview. The analysis excludes households with any wage earnings. It

shows the distribution of financial assets (top panel) and net worth (bottom panel)

for households whose members never stayed in a nursing home throughout the time

that they were in the HRS and for households who reported at least one overnight

stay by either partner.

19

The latter group is further distinguished between

households who did or did not report a stay during the past two years. The

hypothesis is that the assets of households who reported a stay in the past two years

are more likely to deplete than those of other groups. Indeed the mean change in

assets is negative, but the magnitude of the average change would typically pay for

only a short nursing home stay.

19

Financial assets include checking accounts, savings accounts, stock holdings,

bonds, mutual funds, investment trusts, certificates of deposit, other savings (money

owed by others, a valuable collection for investment purposes, an annuity, or rights

in a trust or estate), and IRA holdings. Net worth further includes housing and other

real estate equity (net of mortgages) and the value of vehicles. Neither metric

includes defined contribution pension balances.

Used Home Health

Care in the Past 2

Years

Stayed in Nursing

Home in the Past 2

Years

In nursing home at

time of interview

LTC insurance at

interview?

LTC insurance at

interview?

LTC insurance at

interview?

AgeNoYes NoYes NoYes

<50 1.1% 0.0% 1.1% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0%

50-59 3.1% 4.0% 0.5% 0.6% 0.1% 0.1%

60-69 5.4% 4.8% 1.7% 1.3% 0.6% 0.4%

70-79 10.0% 7.2% 4.8% 3.1% 2.0% 0.9%

80-89 16.8% 14.5% 13.8% 10.1% 7.7% 4.8%

90+ 28.9% 31.9% 30.9% 30.7% 22.4% 17.8%

Total 7.1% 6.7% 3.8% 3.1% 2.0% 1.2%

Source: 1998-2012 HRS.

24

Table 18. Distribution of Change in Financial Assets, Total Assets in Past

Two Years

We turn to a mutivariate analysis of wealth changes between HRS interviews to

measure the financial impact of nursing home stays net of public or private insurance

coverage. As in the previous table, the analysis excludes households with any wage

earnings. It also excludes households with Medicaid beneficiaries, since their out-of-

pocket expenses are likely low. We distinguish between short stays (up to 30 days)

and long stays (more than 30 days), because short stays are often associated with

hospital stays and likely covered by Medicare or private health insurance. Our

hypothesis is that long stays pose the greatest financial risks, and that those risks

are mitigated if (either partner in) a household has private long-term care insurance.

See Table 19.

We are interested in wealth changes. However, wealth levels and their changes vary

widely across households, and outliers may drive results. We therefore measure

wealth through an inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. The inverse hyperbolic

sine is similar to a logarithmic transformation, but allows negative values.

20

Table 19

presents two specifications, for financial assets and net worth.

20

Formally, sinh

√

1. The inverse hyperbolic sine is point-

symmetric around the origin: sinh

sinh

.For positive wealth values w that

are not close to zero, sinh

2

, and for negative values not close to zero,

sinh

2

. For wealth levels that are both positive or both negative in the

current and prior interview, changes in the inverse hyperbolic sine may be

interpreted similar to changes in logarithms, i.e., as relative changes.

Change in Financial Assets (Incl. IRAs)

Subsample

25th

Percentile Median

75th

Percentile

Mean (excl. top

and bottom

deciles)

Never in Nursing Home -26,000 0 41,000 7,045

Ever in Nursing Home -28,000 0 37,000 5,159

Not in Past Two Years -21,326 500 45,000 11,302

During Past Two Years -36,000 -50 29,500 -1,113

Change in Net Worth

25th

Percentile Median

75th

Percentile

Mean (excl. top

and bottom

deciles)

Never in Nursing Home -52,400 4,682 91,000 18,505

Ever in Nursing Home -51,100 1,000 68,000 8,421

Not in Past Two Years -35,800 5,500 84,700 23,265

During Past Two Years -71,000 -1,000 56,500 -7,186

Source: 1998-2012 HRS.

25

Table 19. Wealth Change between HRS Surveys as a Function of Nursing

Home Stays and Insurance Coverage

(Outcome variable: Difference between waves of inverse hyperbolic sine of

wealth)

Consistent with our hypothesis, short nursing home stays did not have a statistically

significant effect on changes in wealth before and after the stay. However, stays in

excess of 30 days had a negative effect, except if the household had long-term care

insurance coverage. Not shown in the table is that the parameter estimates were

sensitive to the model specification, sample selection, and treatment of negative

wealth values. In other words, while the results are consistent with expectations,

direct measurement of out-of-pocket expenses may be preferable to measurement of

wealth changes. Unfortunately, the HRS currently does not offer such direct

measurement.

Finally, Table 20 shows probit regression results of the likelihood of Medicaid

enrollment. The unit of observation is a household interview and the outcome is an

indicator for whether (either partner in) a household reported being covered by

Medicaid. As expected, net worth is strongly negatively related to Medicaid

enrollment. In contrast to Table 19, nursing home stays are measured cumulatively,

with indicators for whether all nursing home stays by either partner prior to the

interview summed to 1-30 days or longer. Both short and long stays increased the

likelihood of Medicaid enrollment, but the effect of long stays was much greater.

Being covered by long-term care insurance reduced the chances of Medicaid

enrollment, presumably because of its association with sufficient means to pay for

such insurance. Contrary to our expectations, the effect of long stays was not

mitigated by long-term care insurance coverage.

Change in inverse hyperbolic sine of:

Financial Assets Net Worth

Short stay (<=30 days) -0.085 -0.085

(0.231) (0.142)

Long stay (>30 days) -0.674 ** -0.491 ***

(0.293) (0.180)

LTC insurance coverage -0.028 -0.048

(0.103) (0.064)

Long stay * LTC insurance 1.198 * 0.955 **

(0.675) (0.415)

Constant 0.054 0.053 *

(0.045) (0.027)

Number of observations 16,485 16,485

Standard errors in parentheses.

Significance: ***=1%, **=5%, *=10%.

Analysis sample excludes households with Medicaid beneficiaries.

26

Table 20. Household Medicaid Coverage as a Function of Cumulative Nursing

Home Stays

6. POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Approximately one-half of Baby Boomers are projected to require paid, formal long-

term care in the home, an adult day care center, an assisted living facility, or a

nursing home (Favreault and Dey, 2016). Paying for care out of pocket could rapidly

exhaust retirement savings of many Americans, prompting them to eventually rely

on Medicaid. Indeed, Medicaid enrollment is about 8% among HRS respondents who

have never stayed in a nursing home and rises to 26% after 101-364 days in a

nursing home and 56% after five years in a nursing home (see Table 16 above). The

size of the Baby Boom generation is expected to drive up demand for and prices of

long-term care, creating a troublesome outlook for the elderly’s personal finances

and the Medicaid program.

Given the high cost of long-term care, workable solutions could involve risk pooling

through public or private insurance. Only about 7 million people are currently

covered by private long-term care insurance, which suggests room for growth.

However, as argued by Brown and Finkelstein (2007, 2008, 2009, 2011) and

summarized above, both insurance companies and consumers face impediments to

more widespread adoption of private LTCI. Among these are uncertainty over the

adequacy of coverage and uncertainty over future premiums. Indeed, the insurance

is designed to be in force for several decades, and past experience shows costs that

outpaced general inflation and substantial premium increases on policies that were

issued prior to the mid-2000s. The uncertainties affect consumers and insurance

companies alike. Some options that may alleviate the uncertainties of both

consumers and the industry are:

Insurance products in which benefits and premiums adjust in tandem with

inflation. Inflation tends to affect the cost of care, wages, and nominal

investment returns in the same direction, so incorporating a link between

benefit levels and premiums should greatly reduce inflation uncertainty. Many

current products offer automatic benefit increases of 3% or 5% annually, but

Probit

Net worth -0.078 ***

(inverse hyperbolic sine)

(0.003)

Short stay(s) 0.164 **

(0<cumulative SNF nights<=30)

(0.066)

Long stay(s) 0.757 ***

(Cumulative SNF nights>30)

(0.057)

LTC insurance coverage -0.502 ***

(0.049)

Long stay(s) * LTC insurance 0.027

(0.147)

Constant -0.489 ***

(0.036)

Number of observations 26,797

Standard errors in parentheses.

Significance: ***=1%, **=5%, *=10%.

27

those increases may be too low or too high. Most products are designed to

charge the same annual premium for the life of the policy, which makes them

relatively expensive early on. Expecting income to keep pace with inflation,

prospective policyholders may be receptive to lower initial premiums that

escalate over time.

Products that combine long-term-care insurance with life insurance and/or

annuities. Longevity risks affect individual products differently, but a

combination product may be easier to price, require less complex

underwriting standards, and offer more comprehensive protection against

financial risks in old age.

State-based reinsurance pools designed to alleviate individual insurers’ risks

and boost consumer confidence that their policies will eventually pay out, if

needed.

Consumers may hesitate to purchase private insurance because some of the

premiums pay for benefits that Medicaid would provide in the absence of private

insurance. Two Medicaid features, in particular, create an implicit tax on private

insurance: (1) private benefits postpone the time at which the asset test for Medicaid

eligibility is met, and (2) Medicaid is secondary payor, i.e., pays only for services

that other insurance do not cover. Public-private partnerships may offer solutions,

such as expansion of state Medicaid Partnership Programs (see Section 4 above).

State Medicaid Partnership Programs make it easier to qualify for Medicaid for

people with high-quality long-term care insurance. Should all benefits under

private long-term care insurance become exhausted, the policyholder may

retain assets equal to benefits paid and still qualify for Medicaid. This modified

asset test addresses the first Medicaid feature responsible for an implicit tax

on private insurance. Under State Medicaid Partnership Programs, the

Medicaid program faces reduced expenditures on long-term care and

consumers can maintain a higher consumption level or leave a bequest.

Similarly, a solution may lie in high-deductible, catastrophic LTCI with private

front-end expense coverage for a set period (1-2 years), and public back-end

coverage paid for the remainder of the LTC need. This would address the

second Medicaid feature responsible for an implicit tax.

While State Medicaid Partnership Programs and high-deductible LTCI policies each

address Medicaid features responsible for an implicit tax on private insurance, few if

any options appear available that fully eliminate the tax while simultaneously

preserving a safety net for low-income Americans and ensuring fiscal sustainability of

the Medicaid program.

Finally, incentives to expand private insurance could be introduced in the workplace.

Allow withdrawals from employer-sponsored retirement plans for LTC

expenses or the purchase of LTCI without early-distribution penalties.

Promote employer-sponsored long-term insurance by allowing plans to be

tax-qualified, so that premiums can be paid through pre-tax payroll

deductions.

To alleviate fiduciary liability and other employer concerns, an alternative

may be to create a publicly run marketplace in which private insurers offer

long-term care insurance that workers may purchase through payroll

deductions. Such an initiative could be modeled on recent state initiatives

with respect to auto-enrollment IRAs.

28

REFERENCES

AALTCI. 2015. “Long-Term Care Insurance Facts – Statistics.” American Association

for Long-Term Care Insurance. Available at http://www.aaltci.org/long-term-

care-insurance/learning-center/fast-facts.php.

AALTCI. 2016a. “Long Term Care Insurance Partnership Plans.” American Association

for Long-Term Care Insurance. Available at http://www.aaltci.org/long-term-

care-insurance/learning-center/long-term-care-insurance-partnership-plans.php.

AALTCI. 2016b. “Types of Group Long-Term Care Insurance Coverage.” American

Association for Long-Term Care Insurance. Available at

http://www.aaltci.org/group-long-term-care-insurance-plans/true-group-ltc.php.

AARP. 2012. “Long-Term Care Insurance: 2012 Update.” AARP Public Policy Institute,

Fact Sheet 261, June 2012. Available at

http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/ltc/2012

/ltc-insurance-2012-update-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf.

BLS. 2016. Consumer Price Index, All Urban Consumers, series CUUR0000SA0 (All

Items) and CUUR0000SAM (Medical Care). Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available

at http://www.bls.gov/data/#prices.

Brown, Jeffrey R. and Amy Finkelstein. 2007. “Why is the Market for Long-Term Care

Insurance So Small?” Working Paper, National Bureau of Economic Research.

http://users.nber.org/~afinkels/papers/Brown_Finkelstein_Small_Feb07.pdf.

Brown, Jeffrey R. and Amy Finkelstein. 2008. “The Interaction of Public and Private

Insurance: Medicaid and the Long-Term Care Insurance Market.” American

Economic Review 98(3): 1083–1102.

Brown, Jeffrey R. and Amy Finkelstein. 2009. “The Private Market for Long-Term

Care Insurance in the United States: A Review of the Evidence.” Journal of Risk

and Insurance, 76(1): 5-29.

Brown, Jeffrey R. and Amy Finkelstein. 2011. “Insuring Long-Term Care in the United

States.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Volume 25(4): 119–142.

California DHCS. 2010. “Asset protection: A Special Benefit Created for Californians.”

California Department of Health Care Services. Available at http://www.dhcs.ca.

gov/services/ltc/Documents/CPLTC%20Print%20Locks/Asset_2010.pdf.

Carrns, Ann. 2014. “Premiums Rise for Long-Term Care Insurance. Keep It or Drop

It?” New York Times, March 21, 2014.

CBO. 2013. “Rising Demand for Long-Term Services and Supports for Elderly

People.” Congressional Budget Office, June 2013. Available at

https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-

2014/reports/44363-LTC.pdf.

Census Bureau. 2012. “Americans with Disabilities: 2010.” U.S. Census Bureau,

Household Economic Studies. July 2012. Available at

http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/p70-131.pdf.

CIPR. 2016. “The State of Long-Term Care Insurance: The Market, Challenges and

Future Innovations.” Eric Nordman (ed). National Association of Insurance

Commissioners and The Center for Insurance Policy and Research, May 2016.

29

Available at http://www.naic.org/documents/cipr_current_study_160519_

ltc_insurance.pdf.

CMS. 2015. Final Rule, Prospective Payment System and Consolidated Billing for

Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) for FY 2016. August 4, 2015. Federal Register

Vol. 80, No. 149, pages 46390-46477.

Cohen, Marc. 2016. “The State of the Long-Term Care Insurance Market.” Included

in CIPR (2016).

Davidson, Joe. 2016. “Costs Skyrocket for Feds’ Long-Term-Care Insurance.” The

Washington Post, July 21, 2016.

Favreault, Melissa and Judith Dey. 2016. “Long-Term Services and Supports for

Older Americans: Risks and Financing.” U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of