MARKETING SCIENCE

Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23

http://pubsonline.informs.org/journal/mksc/ ISSN 0732-2399 (print), ISSN 1526-548X (online)

Match Your Own Price? Self-Matching as a

Retailer’s Multichannel Pricing Strategy

Pavel Kireyev,

a

Vineet Kumar,

b

Elie Ofek

a

a

Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts 02163;

b

Yale School of Management, Yale University, New Haven,

Connecticut 06520

Contact:

Received: July 22, 2015

Revised: June 9, 2016

Accepted: August 9, 2016

Published Online in Articles in Advance:

August 3, 2017

https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2017.1035

Copyright: © 2017 INFORMS

Abstract. Multichannel retailing has created several new strategic choices for retailers.

With respect to pricing, an important decision is whether to offer a “self-matching policy,”

which allows a multichannel retailer to offer the lowest of its online and store prices to con-

sumers. In practice, we observe considerable heterogeneity in self-matching policies: There

are retailers who offer to self-match and retailers who explicitly state that they will not

match prices across channels. Using a game-theoretic model, we investigate the strategic

forces behind the adoption (or non-adoption) of self-matching across a range of compet-

itive scenarios, including a monopolist, two competing multichannel retailers, as well as

a mixed duopoly. Though self-matching can negatively impact a retailer when consumers

pay the lower price, we uncover two novel mechanisms that can make self-matching prof-

itable in a duopoly setting. Specifically, self-matching can dampen competition online

and enable price discrimination in-store. Its effectiveness in these respects depends on

the decision-making stage of consumers and the heterogeneity of their preference for the

online versus store channels. Surprisingly, self-matching strategies can also be profitable

when consumers use “smart” devices to discover online prices in stores. Our findings

provide insights for managers on how and when self-matching can be an effective pricing

strategy.

History:

Preyas Desai served as the editor-in-chief and Dmitri Kuksov served as associate editor for

this article.

Supplemental Material:

The online appendix is available at https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2017.1035.

Keywords:

price self-matching

•

multichannel retailing

•

pricing strategy

•

online shopping

•

omnichannel

•

price discrimination

1. Introduction

Many, if not most, major retailers today use a mul-

tichannel business model, i.e., they offer products in

physical stores and online. These channels tend to

attract different consumer segments and allow retailers

to cater to distinct buying behaviors and preferences.

Consumers are also becoming more savvy in using

the various channels during the buying process, i.e.,

researching products, evaluating fit, comparing prices,

and purchasing (Neslin et al. 2006, Grewal et al. 2010,

Verhoef et al. 2015).

Retailers must attend to all elements of the market-

ing mix as they strive to maximize profits. Not surpris-

ingly, pricing has always been an important strategic

variable for t hem to “get right.” When retailers were

predominantly brick-and-mortar, they had to deter-

mine the most effective store price to set for their mer-

chandise. However, having embraced a multichannel

selling format, pricing decisions have become much

more complex for these retailers to navigate. Not only

do they need to price the products in their physical

stores, they also need to set prices for products in their

online outlets and consider how the prices across the

various channels should relate to one another. This

complexity in devising a comprehensive multichan-

nel pricing strategy is front and center for retailers

today, as evidenced by the myriad commentaries in

the retail trade press. As Forrester Research reports

(Mulpuru 2012), “It is imperative for eBusiness profes-

sionals in retail to adopt cross-channel best practices

including ...pricing.”

Formulating an effective multichannel pricing strat-

egy can be challenging. A recent survey of lead-

ing retailers (eMarketer 2013) revealed that their top

two pricing challenges are: (1) increased price sen-

sitivity of consumers, and (2) pricing aggressiveness

from competitors. In a world where many consumers

buy online or conduct research online before enter-

ing a store, these findings suggest that the need to

manage the heightened price sensitivity and combat

intense competition are becoming even more impor-

tant. Interestingly, the above study did not find the

item “need to provide consistency in price across

channels” to be among the top few challenges these

retailers face, underscoring that they feel they have

flexibility in customizing their price to the specific

1

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

2 Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS

channel and customer mix that chooses to shop there.

Indeed, according to Gartner’s Kevin Sterneckert (Reda

2012, p. 6), “Using a single-channel, consistent pric-

ing strategy misses important opportunities in the

marketplace ...” Consistent with these survey obser-

vations, we specifically investigate how retailers can

leverage self-matching across channels to set prices

flexibly to diminish intense price competition.

With a self-matching policy, the retailer commits to

charging consumers the lower of its online and store

prices for the same product when consumers furnish

appropriate evidence of a price difference. Note that

even though self-matching can provide some degree

of price consistency, it is fundamentally different from

committing to consistent prices and setting exactly

the same prices across all channels, as will be clear

in our analysis in Section 4. Commonly, this policy

features store to online self-matching, allowing con-

sumers to pay the typically lower online prices for store

purchases.

1

This policy is a novel marketing instru-

ment t hat is uniquely available to multichannel retail-

ers and not relevant in the single-channel case. The

primary objective of our paper is to understand the

strategic consequences of such self-matching policies.

We note that competitive price-matching policies have

been extensively studied by contrast (and are reviewed

in Section 2).

Examining a number of retail markets, there are two

distinct self-matching patterns that come to our atten-

tion. First, we observe considerable heterogeneity in the

adoption of self-matching policies across retailers in the

United States, including those competing for the same

market. For example, Best Buy, Sears, Staples, Office

Depot, Toys “R” Us, and PetSmart price match their

online channels in-store, whereas JCPenney, Macy’s,

Urban Outfitters, and Petco explicitly state that they

will not match their prices across channels.

2

Second, we

observe heterogeneity in self-matching across industries.

In consumer electronics and home improvement, major

players offer self-matching, whereas in low-end depart-

ment stores and clothing, most or all retailers tend not

to adopt self-matching.

We aim to develop insights on when to expect dif-

ferent self-matching patterns for multichannel retailers

in a given category, i.e., all self-match, some self-match

while others do not, and none self-match. To this end,

we examine the use of a self-matching pricing policy

by multichannel retailers across a variety of compet-

itive settings, including a monopoly, a duopoly with

two competing multichannel retailers, and a mixed

duopoly in which a multichannel retailer competes

with an e-tailer. More specifically, we address the fol-

lowing research questions:

(1) What strategic mechanisms underpin the deci-

sion to implement a self-matching pricing policy?

(2) When do multichannel retailers choose to self-

match in equilibrium? How do customer and product

characteristics, and the nature of competition, influ-

ence a retailer’s decision to self-match?

(3) How does self-matching affect the prices charged

online and in-store?

(4) Are retailers better or worse off having access to

self-matching as a strategic tool?

To investigate these questions, we develop a model

that allows us to capture the effects of self-matching

on consumer and retailer decisions. We allow for con-

sumer heterogeneity along a number of important

dimensions. These dimensions include consumers’

channel preferences, their stage in the decision-making

process (DMP), and their preference across retailers.

As to channel preferences, we allow for “store-only”

consumers who have a strong preference to purchase

in-store where they can “touch and feel” merchandise

and instantly obtain the product. By contrast, “channel-

agnostic consumers” do not have a strong preference

for any channel from which they purchase. We also

distinguish between consumers who know the exact

product they want to purchase (“Decided”) and con-

sumers who only recognize the need to purchase from

a category and require a store visit to shop around and

find the specific version or model that best fits their

needs (“Undecided”). Finally, consumers have hori-

zontal taste (or brand) preferences across retailers.

Retailers offer unique products of similar value

and are at the ends of a Hotelling linear city, wit h

consumer location on the line indicating retailer pref-

erence. Retailers first choose a self-matching pricing

policy and subsequently and simultaneously set price

levels for store and online channels. We analyze the

subgame perfect equilibria of the game.

Our analysis reveals several underlying mechanisms

that affect the profitability of self-matching in equilib-

rium. The first effect, termed channel arbitrage, is neg-

ative and reduces profits, whereas the other effects

termed decision-stage discrimination and online competi-

tion dampening increase profits. Thus, the overall profit

implications of implementing a self-matching pricing

policy depend on the existence and magnitude of these

effects.

Consider the pricing incentives faced by a mul-

tichannel retailer absent self-matching. In the store

channel, it faces two types of consumers; those who

researched the product online before choosing a store

(decided consumers) and t hose who visit their pre-

ferred store first to identify the product that best

matches their needs (undecided consumers). Retailers

may want to charge a higher price to the latter type,

but are unable to do so because both types purchase in

the store channel. Furthermore, consumers who shop

online tend to be informed of the online prices at both

retailers, which leads to more competitive pricing in

the online channel than in-store.

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS 3

Now, consider the strategic impact of self-matching

policies. With self-matching, consumers who research

the product online but purchase in-store can redeem

the lower online price; we refer to this profit-reducing

effect as channel arbitrage. However, consumers who

visit their preferred store first without searching online

are unable to obtain evidence of a lower price for their

desired product before arriving at the store. These con-

sumers pay the store price even when a self-matching

policy is in effect, leading to the decision-stage discrim-

ination effect, thus allowing a self-matching retailer to

charge different prices to store consumers based on

their decision stage, which can increase profits.

If only one retailer self-matches, decided consumers

can redeem the lower online price at the self-matching

retailer’s store but only have access to the store price at

the rival. This induces the self-matching retailer to set

a higher online price to mitigate the negative impact of

channel arbitrage. The rival follows suit due to strate-

gic complementarity of prices and sets a higher online

price as well, thus softening online competition. We

refer to this profit-increasing mechanism as the online

competition dampening effect, with self-matching serving

as a commitment device to increase online prices from

the purely competitive level. It emerges only when one

of the retailers offers to self-match: If both retailers self-

match, decided consumers have access to the online

prices at both stores, and intense competition in the

online channel ensues.

We also investigate the equilibrium profitability of

the self-matching policy. Our analysis shows that self-

matching is not necessarily harmful. In fact, both re-

tailers can be better off by offering to self-match when the

positive online competition dampening and/or deci-

sion-stage discrimination effects dominate the negative

channel arbitrage effect.

We investigate several model extensions in Section 5.

First, we examine how the presence of consumers

equipped with “smart” devices, who can retrieve

online price information when in the store, affects

retailers’ incentives to implement a self-matching pol-

icy. Intuitively, when more consumers can retrieve the

lower online price, the negative channel arbitrage effect

is more pronounced. However, we find that the pres-

ence of “smart” consumers can allow retailers to ben-

efit even more from online competition dampening by

charging higher online prices. In another extension,

we examine the effects of self-matching in a mixed

duopoly, in which a multichannel retailer competes

with an online-only retailer (i.e., a pure e-tailer). We

find that competition is dampened in the online chan-

nel when the multichannel retailer chooses to self-

match, allowing both retailers to benefit.

Finally, we conducted a consumer survey that allows

us to evaluate how customer and market characteris-

tics pertain to our model setup and findings. We find

evidence of significant consumer heterogeneity on the

dimensions modeled. Mapping the equilibrium pre-

dictions of the model to observed self-matching poli-

cies chosen by firms is suggestive of the relevance of

our approach.

Next, we review the literature (Section 2), describe

the model (Section 3), and analyze equilibrium strate-

gies and outcomes (Section 4). We then consider sev-

eral extensions of the model (Section 5) and conclude

by discussing managerial and empirical implications

as well as future research opportunities (Section 6).

2. Literature Review

We draw from two separate streams of past research.

The first is focused on multichannel retailing, and

the second on competitive price-matching in a sin-

gle channel. Research in multichannel retailing has

typically assumed that retailers set the same or dif-

ferent prices across channels, without examining the

incentives to adopt a self-matching policy. Liu et al.

(2006), for example, study a brick-and-mortar retailer’s

decision to open an online arm, assuming price con-

sistency, or different prices across channels. Zhang

(2009) considers separate prices per channel and stud-

ies the retailer’s decision to operate an online arm and

advertise store prices. Ofek et al. (2011) study retail-

ers’ incentives to offer store sales assistance when also

operating an online channel, allowing for identical or

different pricing across channels. Aside from ignoring

self-matching pricing policies, this literature has not

considered or modeled heterogeneity in consumers’

DMPs, which plays an important role in their channel

choice in practice.

The key theoretical mechanisms modeling sales and

service were developed by Shin (2007) and investigated

further in the literature (e.g. Mehra et al. 2013). While

"price-matching has been suggested as a strategy to

combat showrooming, to our knowledge, t here has not

been a careful modeling and evaluation of whether and

when such policies can be effective, particularly in a

competitive context.”

Competitive price-matching is an area that has been

well studied. This literature has generally focused on

a retailer’s incentives to match competitors’ prices in

a single channel setting, typically brick-and-mortar

stores. Salop (1986) argued that when retailers price

match each other, this leads to higher prices than oth-

erwise, as they no longer have an incentive to engage

in price competition, thus implying a form of tacit

collusion (Zhang 1995). However, competitive price-

matching has also been found to intensify competition

because it encourages consumer search (Chen et al.

2001). Other research in competitive price-matching

has explored its role as a signaling mechanism for cer-

tain aspects of a retailer’s product or service (Moorthy

and Winter 2006, Moorthy and Zhang 2006), the impact

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

4 Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS

of hassle costs (Hviid and Shaffer 1999), interaction

with product assortment decisions (Coughlan and

Shaffer 2009), and the impact of product availability

(Nalca et al. 2010).

By contrast, self-matching pricing policies represent a

phenomenon relevant only for multichannel retailers;

recent retailing trends make self-matching an impor-

tant issue to study. First, the nature of competition

is evolving in many categories, from retailers carry-

ing similar products from multiple brands to manu-

facturers who establish their own retail stores, e.g.,

Apple, Microsoft, and Samsung. Second, many retail-

ers are moving towards establishing strong private

label brands or building exclusive product lines to

avoid direct price wars wit h competitors (Bustillo and

Lawton 2009, Mattioli 2011). For instance, 50% or more

of products sold by retailers such as JCPenney or health

supply retailer GNC are exclusive or private label;

electronics retailers such as Brookstone and Best Buy

are also increasingly focused on private label prod-

ucts.

3

These trends accentuate the relevance of self-

matching relative to competitive price-matching as

the product assortments retailers carry become more

differentiated.

The mechanisms underlying self-matching are also

connected to the broad literature on price discrimina-

tion. Cooper (1986) examines pricing in a two-period

model, where retailers commit to giving consumers

who purchase in the first period the difference between

the first and second period prices if the latter price

is lower (a form of intertemporal self-matching). The

author shows t hat this policy may increase retailer prof-

its as it reduces the incentive to lower prices in the sec-

ond period for both retailers. This effect is similar to

the online competition dampening effect we identify,

whereby a retailer reduces its own incentive to price

lower online by inducing channel arbitrage through

self-matching. However, whereas both retailers can

offer and benefit from a “most-favored-customer” pol-

icy in the intertemporal setting, the online competition

dampening effect can exist only if one retailer offers

to self-match. If both retailers self-match, they reignite

competition in the online market and nullify the effect.

Cross-channel price-matching is thus driven by differ-

ent strategic incentives.

Thisse and Vives (1988), Holmes (1989), and Corts

(1998) consider cases wherein price discrimination may

lead to lower profits for competing retailers in equi-

librium. Similarly, retailers may be compelled to self-

match in equilibrium even though they would have

been better off had self-matching not been an option.

In our context, on one hand, a self-matching policy

acts as a commitment not to price discriminate decided

consumers across channels, which can lead to greater

profits for both retailers because this creates an incen-

tive to increase the online price to mitigate the arbi-

trage effect. On the other hand, a self-matching policy

enables price discrimination between undecided and

decided consumers who shop in-store. Depending on

the relative sizes of these segments, self-matching poli-

cies may emerge in equilibrium and lead to greater or

lower profits for both retailers.

Desai and Purohit (2004) consider a competitive set-

ting where consumers may haggle over price with

retailers. Some form of haggling may occur in the self-

matching setting if retailers are not explicit about their

policies and consumers must wrangle with managers

to obtain a self-match. This interaction may induce

additional costs for consumers and for retailers when

processing a self-matching policy. In our analysis, we

focus on the case of retailers explicitly announcing

their self-matching policies and illustrate how self-

matching emerges in equilibrium in the absence of con-

sumer haggling or hassle costs. In an extension, we

consider the implications of retailer processing costs

when a consumer redeems a self-match.

3. Model

3.1. Retailers

Two competing retailers in the same category are

situated at the endpoints of a unit consumer inter-

val, or linear city, i.e., x ⇤ 0 and x ⇤ 1 (Hotelling

1929). The retailers offer unique and non-overlapping

sets of products. Because they carry different prod-

ucts, they do not have the option of offering competi-

tive price-matching guarantees. For example, Gap and

Aeropostale sell apparel and operate in the same cate-

gories, but the items themselves are not the same and

reflect the dedicated designs and logos of each of these

retailers.

We model a two-stage game in which the retailers

must first decide on self-matching policies and then

on prices in each channel. We denote by SM

i

⇤ 0 t he

decision of retailer i not to self-match and by SM

i

⇤ 1

the decision to self-match, leading to four possible sub-

games, i.e., (0, 0), (1, 1), (1, 0), and (0, 1) representing

(SM

1

, SM

2

). In each subgame, p

k

j

denotes t he price set

by retailer j 2{1, 2} in channel k 2{on, s}, where on

stands for the online or Internet channel and s stands

for the physical store channel. With self-matching, con-

sumers who retrieve the match pay the lowest of the

two channel prices. In the equilibrium analysis that

follows, we find that retailers never set lower prices in-

store than online. Hence, the only relevant matching

policy to focus on is the store-to-online self-match. All

retailer costs are assumed to be zero.

3.2. Consumers

To capture important features of the shopping process

in multichannel environments, we model consumers as

being heterogeneous along multiple dimensions.

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS 5

Retailer Brand Preferences: Consumers vary in their

preferences for a retailer’s product, e.g., a consumer

might prefer Macy’s clothing lines to those offered at

JCPenney. We capture this aspect of heterogeneity by

allowing consumers to be distributed uniformly along

a unit line segment in the preference space, x ⇠ U[0, 1].

A consumer at preference location x incurs a “mis-

fit cost” ✓x when purchasing from retailer 1 and a

cost ✓ (1 x) when purchasing from retailer 2. Note

that the parameter ✓ does not involve transportation

costs, rather it represents horizontal retailer-consumer

“misfit” costs, which are the same across the online

and store channels. Misfit costs reflect heterogeneity in

taste over differentiated products of similar value, e.g.,

the collection of suits at Banana Republic compared to

those at J. Crew.

Channel Preferences: Channel-agnostic (A) consumers

do not have an inherent preference for either channel

and, for a given retailer, would buy from whichever

channel has the lower price for the product they pur-

chase. On the other hand, Store-only (S) consumers find

the online channel insufficient, e.g., due to waiting

times for online purchases, risks associated with online

purchases (such as product defects), etc. These con-

sumers purchase only in the store, alt hough they might

research products online and obtain online price infor-

mation for the product they plan to buy. We assume

that channel-agnostic consumers form a fraction of

size ⌘ of the market while store-only consumers form

a fraction of size 1 ⌘.

Decision Stage: Consumers can differ in their deci-

sion stage, a particularly important aspect of multi-

channel shopping (Neslin et al. 2006, Mulpuru 2010,

Mohammed 2013). Undecided (U) consumers of propor-

tion (0 <<1) need to go to the store because t hey

do not have a clear idea of the product they wish to

purchase. Decided (D) consumers of proportion 1

are certain about the product they wish to buy and

can thus costlessly search for price information from

home. Undecided consumers first visit a retailer’s store,

selecting the store closest to their preference location,

to find an appropriate product that fits their needs.

After determining fit, they may purchase the product

in-store or return home to purchase online, depending

on their channel preference. Consumers obtain a value

v from purchasing their selected product.

Categories such as apparel, fashion, furniture, and

sporting goods are likely to feature more undecided

consumers, as styles and sizes of products are impor-

tant factors that frequently change. Because undecided

consumers do not know which product they want

before visiting a store, they do not have at their dis-

posal all prices while at the store, since keeping track

of a large number of products, models, and versions

even within a category would be impractical. Unde-

cided consumers in the model are unaware of the

Table 1. Consumer Segments and Proportions

Decision stage

Channel preference Undecided (U) Decided (D)

Store (S) (SU): (1 ⌘) (SD): (1 ⌘)(1 )

Agnostic (A) (AU): ⌘ (AD): ⌘(1 )

exact product they wish to purchase beforehand (they

have limited ability to infer prices under different self-

matching configurations before visiting the store).

4

We set the travel cost for a consumer’s first shopping

trip to zero and assume that additional trips are suf-

ficiently costly. Note that if consumers have no cost to

visit multiple stores in person, then we obtain a trivial

specification wherein there is no distinction between

decided and undecided consumers who shop in-store.

Throughout the paper, we focus on the more interest-

ing case wherein additional shopping trips are costly

enough so that store-only undecided consumers do

not shop across multiple physical stores (see proofs of

Propositions 2 and 4 in the appendix for formal condi-

tions on the travel cost). However, in all cases, decided

consumers research products and prices in advance.

5

Table 1 depicts the different consumer segments in-

cluded in the model. We denote the four segments

of consumers as SU, AU, SD, and AD, depending on

their channel preference and decision stage; the size of

each segment is indicated in the corresponding cell of

the table. Each of the four segments is uniformly dis-

tributed on a Hotelling linear city of unit length, such

that consumer location on the line determines retailer

preference. In the online appendix, we present exam-

ples to illustrate the buying process of a consumer

from each segment. Table 2 details the notation used

throughout the paper.

3.3. Sequence of Events

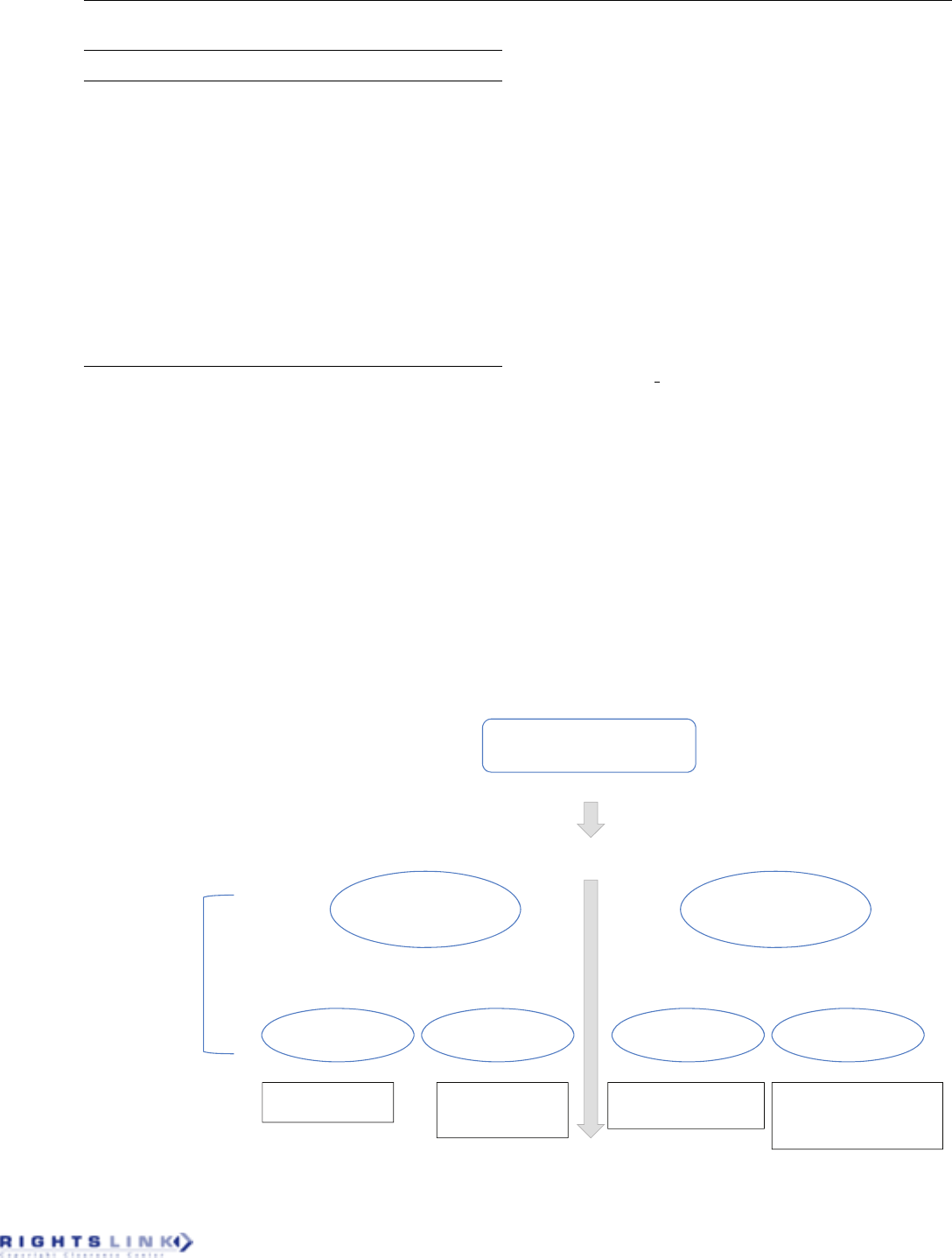

Figure 1 details the sequence of events. First, retailers

simultaneously decide on a self-matching pricing strat-

egy. Then, after observing each other’s self-matching

decisions, they determine the price levels in each chan-

nel. Consumers, depending on their type (decided or

undecided, store or channel-agnostic, and horizontal

preference), decide on which channel and retailer at

which to shop. Decided consumers, who know the

online price before visiting the store, can ask for a

price match if the online price is lower and the retailer

has chosen to self-match. Finally, consumers make pur-

chase decisions and retailer profits are realized.

3.4. Consumer Utility

We now specify the utility consumers derive under

different self-matching scenarios. Recall that store-

decided (SD) consumers know all prices across both

retailers and channels before they make a purchase

decision. Channel-agnostic undecided (AU) consumers

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

6 Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS

Table 2. Summary of Notation

Notation Definition

p

s

j

In-store price for retailer j

p

on

j

Online price for retailer j

SM

j

Retailer j’s self-matching decision

⇧

SM

i

, SM

j

j

Retailer j’s total profit in subgame (SM

i

, SM

j

)

Consumer

v Consumer valuation of the product

✓ Retailer differentiation

1 Fraction of decided segment of consumers

Fraction of undecided segment of consumers

⌘ Fraction of channel-agnostic consumers

1 ⌘ Fraction of store-only consumers

✓ · x for x 2[0 , 1] Measure of retailer preference for consumer

at location x

u

k

j

Utility for purchasing from retailer j

in channel k

have t he option of visiting a store to learn what they

want and then returning home to make an online pur-

chase, whereas store undecided (SU) consumers pur-

chase in the store they first visit or make no purchase.

Consumers obtain zero utility when they do not make

a purchase.

Consider the case when neither retailer self-matches,

i.e., (SM

1

, SM

2

) ⇤ (0, 0). For a consumer who knows

the product she wishes to purchase, the utility for each

retailer and channel option is as follows:

u

on

1

⇤ v p

on

1

✓x, u

s

1

⇤ v p

s

1

✓x,

u

on

2

⇤ v p

on

2

✓(1 x), u

s

2

⇤ v p

s

2

✓(1 x),

(1)

Figure 1. (Color online) Sequence of Events in t he Model

Consumers make purchase decisions

Simultaneously decide on self-matching policies

Obtain product and price information from all

channel and retailer options

Visit store of retailer with closer match to

preferences to learn about products

Decided consumers Undecided consumers

Channel agnostic Store only Channel agnostic Store only

Retailers R1 and R2

Store: R1 and R2

Obtain self-match if

retailer offers policy

Choice set at purchase time

(channel and retailer)

Store: R1 and R2

Online: R1 and R2

Observing policies, simultaneously

set prices in each channel

Consumers

gather

product and

price

information

1

–

2

Store: R1 if x <

Online: R1 and R2

Does not obtain price-match

even if retailer offers policy

Store: R1 if x <

R2 o/w

1

–

2

R2 o/w

,

,

Note. o/w, otherwise.

where v is the value of the product, p

k

1

and p

k

2

(k ⇤ on or

k ⇤ s) are the prices set by retailers 1 and 2, respectively,

✓ measures the degree of consumer preferences for

retailers, and x 2[0, 1] is the consumer’s location (in

the preference space) relative to retailer 1.

Whereas t hese utilities apply to all consumers, not all

segments have access to all purchase options. Figure 1

details the choice set available to each segment. For

example, the channel-agnostic decided (AD) consumer

has access to all four options, whereas the store-only

undecided (SU) consumer only has the option of pur-

chasing from his preferred store (e.g., retailer 1). Thus,

consumer heterogeneity results in different choice sets

available to each segment.

Undecided consumers (both SU and AU), who do

not know which specific product they need, first visit

the retailer closer to their preference location (i.e., visit

retailer 1 if x <

1

2

and retailer 2, otherwise). After their

shopping trip, the store-only undecided (SU) segment

must decide whet her to buy the product that fits their

needs at the store or make no purchase; hence only

the corresponding u

s

-expression in (1) is relevant for

such a consumer. Channel-agnostic undecided (AU)

consumers can purchase in the store they first visit and

pay the store price, or return home and make an online

purchase from either retailer; the utility expressions

u

s

1

, u

on

1

, u

on

2

are thus relevant for AU consumers who

prefer retailer 1, and u

s

2

, u

on

1

, u

on

2

are relevant for AU

consumers who prefer retailer 2.

The Impact of Self-Matching Prices. We now examine

how self-matching practices by retailers impact con-

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS 7

sumer utilities. Decided consumers know all prices for

the specific product they want, and if they shop at

the store offering self-matching, they can come armed

with the online price and request a price match. Thus,

decided consumers can obtain a price match in-store

whereas undecided consumers cannot.

When both retailers offer a self-matching pricing pol-

icy, i.e., under (SM

1

, SM

2

) ⇤ (1, 1), a consumer at x 2

[0, 1] who can obtain a self-match faces the following

utilities:

u

on

1

⇤ v p

on

1

✓x, u

s

1

⇤ v min(p

s

1

, p

on

1

)✓x

u

on

2

⇤ v p

on

2

✓(1 x),

u

s

2

⇤ v min(p

s

2

, p

on

2

)✓(1 x).

(2)

Consumers who cannot obtain a price self-match

(i.e., undecided consumers) continue to face the cor-

responding utilities specified in Equation (1). Note

that although the utility expressions remain the same,

retailers may set different prices under different self-

matching scenarios. Hence, the equilibrium utilities

experienced by consumers will typically differ depend-

ing on retailer self-matching policies.

Next, consider consumers’ channel preferences.

Channel-agnostic decided (AD) consumers have no

particular preference for any channel and would

choose the lower-priced channel option. Store decided

(SD) consumers choose one of the stores based on their

preferences and prices. However, they can obtain the

lower online price if the retailer offers a self-matching

policy. Thus, the expressions for u

s

j

for j ⇤ 1, 2 are dif-

ferent in (2) compared to (1). Undecided (AU and SU)

consumers do not know which product they want until

they visit the store. They face the same utilities under

(1, 1) as under (0, 0) since they cannot redeem match-

ing policies when they visit a retailer’s store without

making an additional costly set of trips, i.e., back home

to determine online prices and then back to a store to

make the purchase.

Utilities in the asymmetric subgame (1, 0), where

only retailer 1 offers to self-match prices, are defined

similar to the (0, 0) case, with only u

s

1

changing for

decided consumers, who can obtain a self-match only

from retailer 1 but not retailer 2:

6

u

s

1

⇤ v min(p

s

1

, p

on

1

)✓x.

4. Analysis

We begin our analysis by considering the benchmark

monopoly case, then the multichannel duopoly setting.

All proofs are in the appendix along with the defined

threshold values and constants. Note that in all cases,

we derive conditions for the market to be covered in

the proof; our text discussion will focus on the region

of coverage in equilibrium.

7

4.1. Benchmark Monopoly: A Single Entity Owns

Both Retailers

Consider a monopolist that jointly maximizes the prof-

its of two multichannel retailers at the endpoints of a

unit segment by choosing a self-matching policy and

setting prices.

8

The following holds:

Proposition 1. A monopolist cannot increase profits by

self-matching prices across channels.

The monopolist will price to extract the great-

est surplus from each channel. Because undecided

and decided consumers are present in both chan-

nels, the prices charged will be the same in both and

equal to the monopoly price of (v ✓/2), regardless of

whether the monopolist offers a self-matching policy.

The monopolist thus obtains no additional profit when

offering the policy and will not offer it when it entails

a minimal implementation cost.

4.2. Multichannel Duopoly

We now consider the case of two competing multi-

channel retailers who make decisions according to the

timeline in Figure 1. We examine each of the possi-

ble self-matching policy subgames and conclude with

a result highlighting the conditions under which self-

matching emerges in equilibrium.

For notational convenience, we define the function

(p

k

1

, p

k

2

; ✓) :⇤

1

2

+ (p

k

2

p

k

1

)/(2✓) to represent t he propor-

tion of demand obtained by retailer 1 from a specific

segment of consumers who face prices p

k

1

and p

k

2

from

the two retailers.

No Self-Matching—(0, 0). In the (0, 0) subgame wherein

neither retailer self-matches, store-only consumers (SD

and SU segments) purchase from the store channel

and pay the store price. Channel-agnostic (AD and

AU) consumers can also purchase from either retailer’s

online channel. AD consumers will begin their search

process online, whereas AU consumers will first visit

their preferred retailer to browse products, then return

home to purchase online after they discover the specific

product they wish to purchase. Retailers compete for

these two consumer segments in the online channel.

SU consumers visit the retailer closest in preference

to them to learn about products. Recall that these con-

sumers do not purchase online and do not switch stores

because of travel costs associated with multiple store

visits. Each retailer effectively has a subset (/2) of such

consumers.

On the other hand, SD consumers know the prod-

uct they want and are informed of all prices. They

purchase in-store, given their channel preference, but

make a decision on which store to visit after factoring

in their retailer preferences and prices. Thus, there is

intense competition among retailers for this segment,

since by reducing store price, a retailer can attract more

SD consumers.

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

8 Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS

The profit functions of retailers 1 and 2 can be writ-

ten as

⇧

0, 0

1

⇤ ⌘(p

on

1

, p

on

2

)p

on

1

| {z }

Channel-Agnostic Decided and Undecided

+ (1 ⌘)

(1 )(p

s

1

, p

s

2

)

| {z }

Store-Only Decided

+ /2

|{z}

Store-Only Undecided

p

s

1

,

⇧

0, 0

2

⇤ ⌘(1 (p

on

1

, p

on

2

))p

on

2

+ (1 ⌘)

(1 )(1 (p

s

1

, p

s

2

)) + /2

p

s

2

.

In the (0, 0) case, the online situation is similar

to retailers competing in a horizontally differentiated

market comprised of only channel-agnostic consumers.

The resulting equilibrium prices, therefore, reflect the

strength of consumers’ preferences for retailers, with

ˆ

p

on

1

⇤

ˆ

p

on

2

⇤ ✓. We refer to a price of ✓ as the “competi-

tive” price level to reflect the fact that this would be the

price charged in a standard Hotelling duopoly model

with one retail channel.

Next, we turn to the store channel, where we obtain

symmetric equilibrium prices of

ˆ

p

s

1

⇤

ˆ

p

s

2

⇤

8

>

>

>

><

>

>

>

>

:

v

✓

2

,

v

✓

1

2

+

1

1

,

✓

1

,

v

✓

>

1

2

+

1

1

. (3)

There are a few useful observations to be made here.

First, for v/✓

1

2

+ 1/(1 ), retailers serve the entire

market even though they charge the monopoly price

in-store. This is possible because of the existence of

SU consumers: Retailers prefer to charge the monopoly

price to extract all surplus from SU consumers if the

ratio of product value to retailer differentiation is suffi-

ciently low. Second, if v/✓>

1

2

+ 1/(1 ), then retailers

charge a store price of ✓/(1 ), which is larger than

the competitive price of ✓ . When v/✓ is sufficiently

large, retailers can no longer maintain monopoly prices

in-store and prefer to compete for SD consumers. How-

ever, the existence of SU consumers enables retailers

to charge more in-store than online, and the retailers

extract more surplus from both SU and SD segments.

Symmetric Self-Matching—(1, 1). In this case, both re-

tailers implement a self-matching policy. The first and

most obvious result of self-matching is the channel arbi-

trage effect, and the intuition here is straightforward.

Recall that SD consumers shop in-store and pay

ˆ

p

s

j

as

in Equation (3) absent a self-matching policy. However,

with a self-match they pay the lower online price while

shopping in-store, resulting in less profit for the retailer

due to arbitrage across channels.

Although this arbitrage intuition is correct, it is

incomplete in determining whether in equilibrium a

self-matching pricing policy will be adopted. When

a multichannel retailer chooses to self-match, there

emerges an important distinction between the store-

only decided (SD) and undecided (SU) consumers.

Whereas the SD consumers can obtain a price match,

SU consumers only know which product they desire

during a store visit. Because they lack evidence of a

lower online price, they always pay the store price.

Thus, even though the two segments of store con-

sumers obtain the product in-store, they effectively pay

different prices. Self-matching thus enables the retailer

to price discriminate consumers based on their deci-

sion stage.

Retailers’ profits in this self-matching setting are

thus

⇧

1, 1

1

⇤ (1 (1 ⌘))

1

(p

on

1

, p

on

2

)p

on

1

| {z }

Channel-Agnostic and Store-Only Decided

+ (1 ⌘)

2

p

s

1

| {z }

Store-Only Undecided

,

⇧

1, 1

2

⇤(1 (1 ⌘))(1

1

(p

on

1

, p

on

2

))p

on

2

+ (1 ⌘)

2

p

s

2

.

In the pricing sub-game, retailers set equilibrium on-

line prices

ˆ

p

on

1

⇤

ˆ

p

on

2

⇤ ✓, since there is no force to pre-

vent online prices from dropping to their competitive

level. However, retailers set store prices

ˆ

p

s

1

⇤

ˆ

p

s

2

⇤ (v

✓/2) to extract surplus from their respective “captive”

sets of SU customers, who pay the store price. We refer

to the ability to extract additional surplus from SU

consumers through self-matching as the decision-stage

discrimination effect.

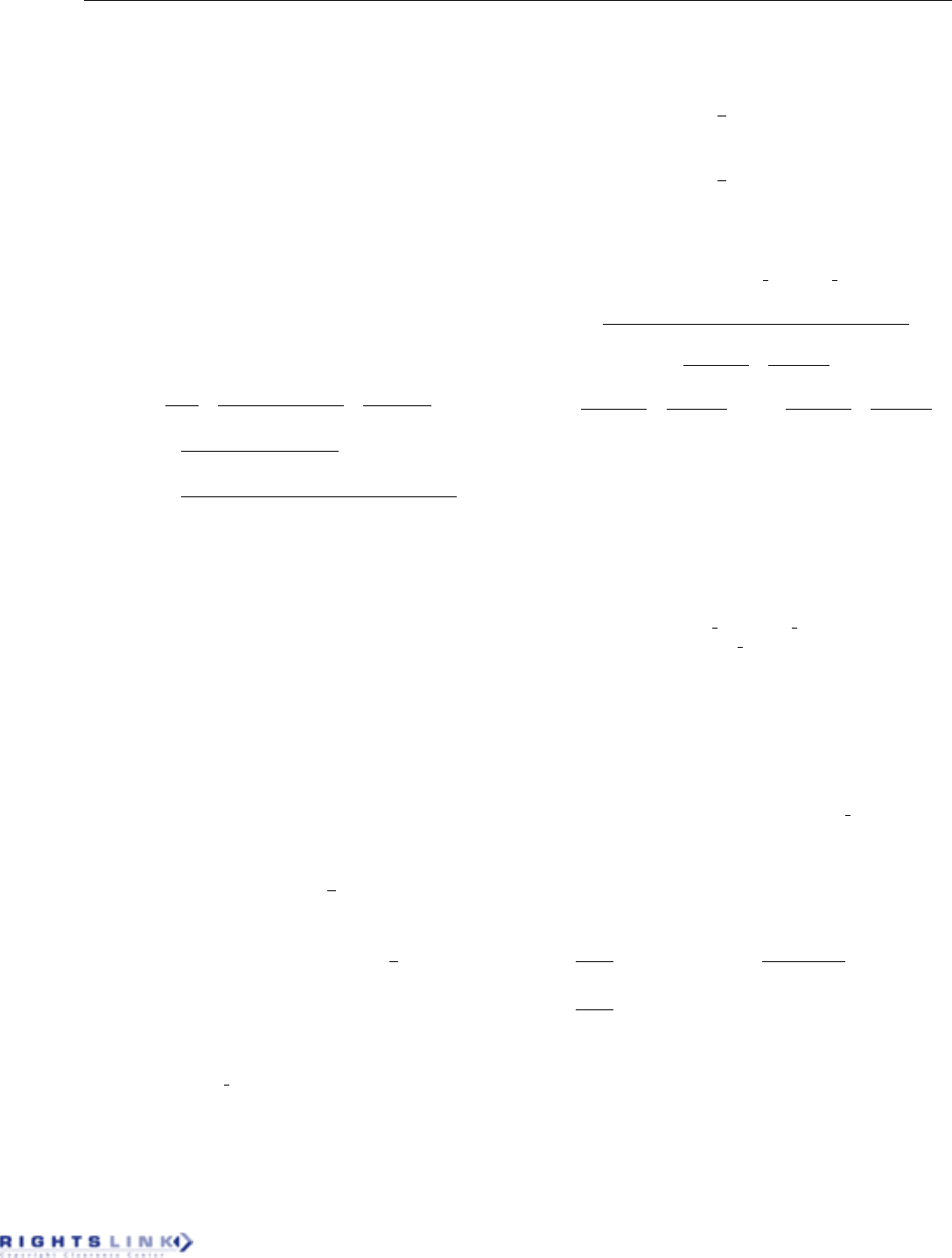

Figure 2 illustrates pricing and purchase outcomes

across the (0, 0) and (1, 1) subgames. The dashed

regions cover the segments that pay the store price,

whereas the solid-filled regions show the segments

that pay the online price. In the (0, 0) subgame, SU

and SD consumers purchase in-store and pay the same

store price, whereas AU and AD consumers purchase

online and pay the online price. In the (1, 1) subgame,

SU and SD consumers purchase in-store, but SD con-

sumers now pay the online price. Thus, self-matching

allows a retailer to simultaneously price discriminate

consumers across decision stages in the store and de-

segment decided consumers across channels.

Asymmetric Self-Matching—(1, 0). Next, we explore

the case wherein retailer 1 offers a self-matching policy

while retailer 2 does not, i.e., the (1, 0) self-matching

subgame. By symmetry (or relabeling), similar results

follow in the (0, 1) subgame. Observe t hat SD con-

sumers who visit retailer 1’s store can purchase there

and pay the lower of the online and store price,

i.e., min(p

on

1

, p

s

1

). However, if an SD consumer visits

retailer 2’s store instead, she faces a price of p

s

2

and can-

not obtain the online price in-store (since retailer 2 does

not self-match). Moreover, by offering a self-matching

policy, and as long as its online price satisfies p

on

1

< p

s

2

,

retailer 1 attracts some SD consumers who are closer in

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS 9

Figure 2. The Effects of Self-Matching

AU AD AD AU

SU SD SD SU

AU AD AD AU

SU SD SD SU

AU AD AD AU

SU SD SD SU

Retailer 1 Retailer 2

Online

In-store

Retailer 1 Retailer 2

Online

In-store

Retailer 1

Retailer 2

Online

In-store

(a) No self-matching—(0, 0)

(b) Symmetric self-matching—(1,1)

(c) Asymmetric self-matching—(1, 0)

Online price Store price

preference to the competing retailer 2 but who choose

to visit retailer 1’s store in anticipation of paying the

lower online price through a self-match.

For SD consumers, under p

on

1

< p

s

1

, the store price

of retailer 1 is irrelevant (since they retrieve the price

match); the retailer can set a store price level to capture

the highest possible surplus from the SU consumers

who are closer to its location. Thus, decision-stage price

discrimination persists in the asymmetric subgame.

We obtain the following profit functions:

⇧

1, 0

1

⇤ ⌘

1

(p

on

1

, p

on

2

)p

on

1

| {z }

Channel-Agnostic

+ (1 ⌘)

(1 )

1

(p

on

1

, p

s

2

)p

on

1

| {z }

Store-Only Decided

+ /2p

s

1

|{z}

Store-Only Undecided

,

⇧

1, 0

2

⇤ ⌘(1

1

(p

on

1

, p

on

2

))p

on

2

+ (1 ⌘)

(1 )(1

1

(p

on

1

, p

s

2

)) + /2

p

s

2

.

Solving for the second-stage pricing subgame, we find

that the online price levels chosen by the retailers are

higher than the Hotelling competitive price of ✓ in both

channels and critically depend on the ratio of prod-

uct value v to the retailer differentiation parameter

✓ as follows. For v/✓ (

4

3

+ 1/(6(1 (1 ⌘))) + /

(2(1 ))), both retailers will extract all surplus from

SU consumers and set prices

ˆ

p

on

1

⇤ ✓ +

(1 )(1 ⌘)(2v 3✓)

4(1 (1 ⌘)) ⌘

,

ˆ

p

on

2

⇤ ✓ +

(1 )(1 ⌘)(2v 3✓)

8(1 (1 ⌘)) 2⌘

,

ˆ

p

s

1

⇤

ˆ

p

s

2

⇤ v

✓

2

.

For v/✓>(4/3 + 1/(6(1 (1 ⌘))) + /(2(1 ))),we

find that retailers set prices

ˆ

p

on

1

⇤ ✓

✓

2

3

+

1

3(1 (1 ⌘))

◆

,

ˆ

p

on

2

⇤ ✓

✓

5

6

+

1

6(1 (1 ⌘))

◆

,

ˆ

p

s

1

⇤ v

✓

2

,

ˆ

p

s

2

⇤

ˆ

p

on

2

+

✓

2(1 )

.

Interestingly, equilibrium online prices in the asym-

metric self-matching (1, 0) case are greater than those

set in the no self-matching (0, 0) case and the sym-

metric self-matching (1, 1) case. The intuition follows

from the idea that although self-matching retailer 1

loses profit from the SD segment of consumers who

can invoke the price self-match, the policy effectively

acts like a “commitment device” to prevent online

prices from going all the way down to the compet-

itive level. More important, when only one retailer

self-matches online competition softens, which results

in channel-agnostic AD and AU consumers paying a

higher price (relative to the competitive online price of

✓ they were paying under no self-matching or sym-

metric self-matching cases). Thus, self-matching has a

positive effect on profits through t his third mechanism,

which we term the online competition dampening effect.

Note that the situation in the asymmetric (1, 0) case

differs from the case when both retailers self-match.

Under (1 , 1), SD consumers can redeem the online

price at both retailers’ stores, which forces online

prices down to their competitive level ✓. By con-

trast, Figure 2 illustrates how, in the asymmetric (1, 0)

case, SD consumers can only redeem the match from

retailer 1. Retailer 2 will price higher in-store relative

to retailer 1’s online price, as SD consumers and its

captive segment of SU consumers pay its store price,

whereas retailer 1 fully segments out its store con-

sumers through the self-matching policy invoked by

its SD consumers (while retailer 1’s SU consumers con-

tinue to pay its store price). However, to mitigate the

downside effect of channel arbitrage, retailer 1 does not

set its online price as low as ✓; this move also allows

it to extract greater surplus from the channel agnostic

segments. Because online prices are strategic comple-

ments across retailers, retailer 2’s best response is to

increase its online price as well. This results in online

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

10 Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS

Table 3. Effects of Self-Matching for Retailer 1 in a

Multichannel Duopoly

Relevant

Effect Subgames

() Channel Arbitrage: SD consumers redeem lower

online price in the store, reducing profits from SD.

(1, 0)(1 , 1)

(+) Decision-Stage Discrimination: Retailer avoids

competing for SD segment on store prices; instead

letting them obtain lower online prices. This

allows higher store prices to captive SU segment.

(1, 0)(1 , 1)

(+) Online Competition Dampening: Retailer charges

higher online price to mitigate arbitrage,

increasing profit from AD, AU, and SD segments.

(1, 0)

prices at both retailers being higher than the competi-

tive level, leading to online competition dampening.

The results detailed in this section are based on the

pricing subgame, taking the self-matching policies as

given. The pricing equilibria depend on the magni-

tudes of the three effects induced by self-matching.

Table 3 presents a summary of the effects we have iden-

tified. Note that the negative channel arbitrage effect

and the positive decision-stage discrimination effect

always occur for a self-matching retailer, while online

competition dampening occurs only when one self-

matches but the rival does not. We now examine the

full equilibrium results of the game beginning with the

self-matching strategy choices.

4.3. Self-Matching Policy Equilibria in a

Multichannel Duopoly

For a self-matching policy configuration to emerge in

equilibrium, it must be the case that neither retailer

would be better off by unilaterally deviating to offer a

different policy. Proposition 2 details the equilibrium

conditions and the resulting choices of self-matching

policies. Across all regions of the parameter space, we

restrict our focus to Pareto-dominant equilibria.

Proposition 2. In a duopoly featuring two multichannel

retailers, self-matching policies are determined by the follow-

ing mutually exclusive regions

• Asymmetric equilibrium (1, 0). One retailer will offer

to self-match its prices while the other will not when product

values are relatively low or retailer differentiation is high.

• Symmetric non-matching equilibrium (0, 0). Neither

retailer will self-match its prices when product values and

retailer differentiation are at intermediate levels.

• Symmetric matching equilibrium (1, 1). Both retailers

will self-match prices when product values are high or re-

tailer differentiation is low.

The above result indicates that all three types of

joint strategies can emerge in equilibrium depending

on the nature of the product and degree of compet-

itive interaction. To understand the intuition behind

the emergence of the different equilibria, it is critical to

examine how the focal retailer’s best response function

evolves as the ratio of product value to retailer dif-

ferentiation (v/✓) changes. We translate best response

functions into equilibria in Figure 3. The top arrow

depicts retailer 1’s best response if retailer 2 does not

self-match. The middle arrow depicts retailer 1’s best

response if retailer 2 self-matches. The dominant effects

for retailer 1 are listed below the arrows. The bottom

arrow shows the emergent Pareto-dominant equilibria.

The best response of the focal retailer depends on the

competitor’s self-matching strategy as well as the three

effects we have previously described, i.e., channel arbi-

trage, decision-stage discrimination, and online competition

dampening.

Retailer 1’s Best Response to Retailer 2 Not Self-

Matching. For low v/✓, the retailer’s store price (v

✓/2) is relatively close to its competitive online price

✓ because there is little additional surplus the retailer

can extract from its captive SU consumers by pricing

higher in-store. As a result, effects that have an impact

on the store channel, i.e., the negative channel arbi-

trage effect and the positive decision-stage discrimina-

tion effect are negligible. However, online prices can

increase with self-matching due to the online compe-

tition dampening effect. This leads retailer 1 to offer

a self-matching policy to take advantage of the addi-

tional profits from the online channel.

As v/✓ increases, so does the difference in prices

across channels. For intermediate values of v/✓, the

retailer can extract more surplus from SU consumers,

driving it to price higher in-store even if it does not self-

match, thus reducing the benefits of decision-stage dis-

crimination. Because a self-matching policy allows SD

consumers to redeem the lower online price, the chan-

nel arbitrage effect increases. As competition in the

online channel is more intense than in the store chan-

nel, the positive online competition dampening effect

can no longer overcome t he negative channel arbitrage

effect. Consequently, the channel arbitrage effect dom-

inates the other two effects, and t he retailer no longer

finds it profitable to self-match as a best response.

At high v/✓ levels, retailer 1 is compelled to compete

more intensely for SD consumers closer to retailer 2 in

preference, resulting in a store price of ✓/(1 ) that

no longer grows in v, if the retailer does not self-match.

Thus, the negative impact due to channel arbitrage is

limited. However, if the retailer were to offer a self-

matching policy, decision-stage discrimination would

allow it to charge the monopoly price (v ✓/2) to cap-

tive SU consumers, which increases as v/✓ increases.

This creates a strong positive impact on profits, result-

ing in retailer 1 choosing to offer self-matching.

Retailer 1’s Best Response to Retailer 2 Self-Matching.

We now turn to the case wherein retailer 2 decides to

offer a self-matching policy.

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS 11

Figure 3. (Color online) Retailer Best Responses

Best response of

retailer 1 given

retailer 2 does

not self-match

Self-match Do not self-match

Do not self-match Self-match

Equilibrium regions

(1,1)(0,1) or (1, 0) (0, 0)

Dominant effect

Dominant effect

Online competition

dampening (+)

Channel arbitrage (–) Decision stage

discrimination (+)

Online competition

dampening (+)

Decision stage

discrimination (+)

Best response of

retailer 1 given

retailer 2 self-

matches

Self-match

v

–

à

v

–

à

v

–

à

Recall that when both retailers self-match, the online

competition dampening effect ceases to exist. Because

retailer 2 is self-matching, its actions will result in

online competition dampening only if retailer 1 does

not self-match. This creates an incentive for retailer 1

to refrain from self-matching at low values of v/ ✓,to

benefit from online competition dampening through

strategic complementarity in prices. Furthermore, at

low values of v/✓, the decision-stage discrimination

effect is small as retailer 1 cannot extract a substantial

amount of surplus from SU consumers.

As v/✓ increases, the benefit of decision-stage dis-

crimination grows because the retailer can extract

greater surplus from SU consumers if it can charge

them a different price than SD consumers. This leads

retailer 1 to adopt self-matching for high values of v/✓.

Strategic Substitutes or Complements. We integrate

the best responses to obtain equilibrium strategies and

focus on whether self-matching strategies across retail-

ers are strategic complements or substitutes. We find

from the best responses that at low product values,

and/or at high levels of retailer differentiation, the self-

matching strategies act like strategic substitutes, so t hat

a retailer will choose the strategy opposite to that of its

competitor. As v/✓ increases to an intermediate level,

we obtain a symmetric equilibrium where no retailer

self-matches and strategies are strategic complements.

Finally, when v/✓ is above a high threshold, the strong

impact of decision-stage discrimination leads to self-

matching being a dominant strategy regardless of what

the competitor chooses. Figure 4 shows the equilibrium

regions that emerge in the v/✓ $ space for a fixed

value of ⌘ 2(0, 1) based on Proposition 2.

Next, we turn to how the equilibrium regions are

affected by and ⌘.

Corollary 1. An increase in the fraction of undecided con-

sumers will grow the asymmetric equilibrium region and

shrink the symmetric equilibrium regions.

According to the corollary, retailer 1 has more of an

incentive to offer a self-matching policy as increases,

implying that the v/✓-region for which we can sustain

the (1, 0) equilibrium expands. To understand the intu-

ition for Corollary 1, consider the case of focal retailer

1’s best response when retailer 2 does not self-match.

As the fraction of undecided consumers increases, the

Figure 4. Equilibrium Regions

Symmetric (0, 0)

Asymmetric (1, 0)

v/à

(ratio of product

value to

differentiation)

Ç (size of undecided segment)

Symmetric (1,1)

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

12 Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS

retailers stand to gain more from online competition

dampening (because of the greater fraction of AU con-

sumers). Thus, if retailer 1 self-matches, retailer 2 will

refrain from doing so (because when both self-match,

the online competition dampening effect is nullified).

The next corollary examines the effect of ⌘ on the

equilibrium regions.

Corollary 2. An increase in the fraction of channel-agnostic

consumers ⌘ will grow the region where retailers choose not

to self-match.

The profitability of self-matching largely depends on

the existence of SU consumers. When the fraction of

store-only consumers decreases (i.e., ⌘ grows), retail-

ers can no longer benefit as much from decision-stage

discrimination. Thus, the profitability of offering a self-

matching policy decreases as ⌘ increases.

4.4. Profitability of Self-Matching

We have thus far analyzed how retailers decide

whether to adopt self-matching policies and character-

ized the strategies that can be sustained in equilibrium.

Here, we examine the profit impact of having self-

matching available as a strategic option. The key issue

we seek to understand is whether retailers are com-

pelled by competitive forces to adopt self-matching,

even though it might not be beneficial and could result

in lower equilibrium profits were self-matching not an

option. The result in Proposition 3 addresses this issue.

Proposition 3. The profit implications of self-matching,

compared to the baseline case where self-matching is not

available as an option, are as follows

(a) In the asymmetric equilibrium (1, 0). The retailer

offering to self-match earns greater profits, but the competing

retailer earns lower profits.

(b) In the symmetric self-matching equilibrium (1, 1).

Both retailers earn higher profits when product valuation is

high or retailer differentiation is low. Otherwise, they both

earn lower profits.

We find that at low values of v/✓, the profit impact

of self-matching is asymmetric, with the self-matching

retailer obtaining higher profits.

We find t hat in the region of v/✓ where symmet-

ric self-matching occurs in equilibrium, when v/✓ is

close to its lower bound, self-matching reduces profits

for both retailers because of the lower positive impact

of decision-stage discrimination and the increasing

negative impact of channel arbitrage. This interaction

results in a situation wherein both retailers would have

benefitted had self-matching not been an option. How-

ever, when v/✓ is high, both retailers choose to self-

match and ear n higher profits. This occurs because at

high v/✓, decision-stage discrimination overtakes the

negative impact of channel arbitrage. Overall, we find

that the availability of self-matching as a strategy may

enhance profits for at least one retailer and can also do

so for both retailers for a range of parameters, high-

lighting the importance of self-matching as a strategic

option.

5. Extensions

The base model analyzed in Section 4 focused on devel-

oping an understanding of the mechanisms underlying

the effectiveness of self-matching and the conditions

for retailers to implement the policy in equilibrium.

Here, we have two main objectives. First, we will exam-

ine additional settings that are relevant to retailers as

they contemplate whet her to offer a self-matching pric-

ing policy. Second, we relax a few key assumptions in

the baseline model, with a view towards increasing the

range of applicability of the findings. Proofs for results

presented in this section are provided in Appendix B

and the Electronic Supplement.

5.1. Impact of “Smart-Device” Enabled Consumers

The baseline model characterized undecided con-

sumers as not knowing what specific product they

want until they visit a store to evaluate which item

from the many available options best fits their needs.

They could not invoke a self-matching policy because

they were in-store at the time of their final decision,

and there was no way for them to access the Internet to

produce evidence of a lower online price.

Here, we recognize the increasing importance of

mobile devices to alter this dynamic and examine the

implications for self-matching policies. Retail Touch-

Points (Fiorletta 2013) notes that, “Amplified price

transparency—due to the instant availability of infor-

mation via the web and mobile devices—has encour-

aged retailers to rethink their omnichannel pricing

strategies.” Intuitively, one might expect that the

greater the proportion of consumers who carry smart

devices and take the trouble to check online when

in-store, the less profitable self-matching should be

(because of the increased threat of cross-channel arbi-

trage). We show t hat this need not be the case.

Suppose that a fraction µ (0 <µ<1) of consumers

has access to the Internet while shopping in-store.

We refer to these consumers as “smart” to reflect the

notion that with the aid of Internet-enabled smart-

phone devices these consumers can easily obtain

online price information while in-store. Store-only

undecided smart consumers can now invoke a self-

matching policy if the online price offered by a retailer

is lower than its store price. Channel-agnostic unde-

cided smart consumers will effectively behave as we

have already modeled in the baseline model.

An increase in smart consumers can be understood

as increasing the fraction of store-only undecided (SU)

consumers who redeem the online price. However,

these consumers can only purchase from the retailer

Downloaded from informs.org by [128.36.7.68] on 18 September 2017, at 11:56 . For personal use only, all rights reserved.

Kireyev, Kumar, and Ofek: Match Your Own Price?

Marketing Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–23, © 2017 INFORMS 13

they first visit, by contrast to store-only decided (SD)

consumers who have the option of buying from other

retailers at the outset. To see how the existence of smart

consumers impacts retailers’ strategies, consider the

profits retailers earn if they both offer to self-match

⇧

1, 1

1

⇤ (1 (1 ⌘))

1

(p

on

1

, p

on

2

)p

on

1

+ (1 ⌘)

2

((1 µ)p

s

1

+ µp

on

1

),

⇧

1, 1

2

⇤ (1 (1 ⌘))(1

1

(p

on

1

, p

on

2

))p

on

2

+ (1 ⌘)

2

((1 µ)p

s

2

+ µp

on

2

).

Solving for the equilibrium reveals that retailers will

set p

on

1

⇤ p

on

2

⇤ ✓(1 µ) + µ✓/(1 (1 ⌘)) and

ˆ

p

s

1

⇤

ˆ

p

s

2

⇤ v ✓/2. Note that the online prices are increasing

in µ. We detail how smart consumers impact retailers’

equilibrium incentives to self-match in Proposition 4.

Proposition 4. In a duopoly with two multichannel retail-

ers, where some consumers can use a smart device in-store

to obtain online price information

(a) As the fraction of smart consumers increases, the

asymmetric equilibrium region grows, whereas the symmet-

ric self-matching equilibrium region shrinks.

(b) Retailer profits can increase in the fraction of smart

consumers.

At low product values, holding fixed the other

model parameters, more smart consumers enhance the

online competition dampening effect in the asymmet-

ric equilibrium, which allows retailers to price higher

online when offering to self-match. On the other hand,

the conditions for symmetric self-matching policies to

emerge in equilibrium for high product values become

more stringent as µ grows. That is, as µ ! 1, the sym-

metric self-matching region for high v shrinks in size to

zero. This happens because the existence of smart con-

sumers greatly erodes the positive decision-stage dis-

crimination effect of self-matching, as there are fewer

SU consumers who will still pay the high store price,

while more consumers pay the lower online price,

thereby reducing retailers’ incentives to self-match.

Thus, and somewhat counterintuitively, the presence

of smart consumers need not decrease the profitability

of a self-matching retailer (see proof of Proposition 4

in Appendix B for details of the profit enhancing case).

On the contrary, smart consumers can enable retail-

ers to charge higher online prices, increasing the prof-

itability of self-matching policies. This suggests that

given current technology trends, horizontally differen-

tiated retailers would find it worthwhile to more care-

fully examine whether self-matching is an appropriate

strategic option.

5.2. Mixed Duopoly: Multichannel

Retailer and E-Tailer

We consider the case of a multichannel retailer facing

a pure online e-tailer, i.e., a “mixed duopoly market.”

This market structure is becoming more important for

a number of multichannel retailers, e.g., several retail-

ers find that Amazon and potentially other e-tailers are

their primary rivals. Past research has considered the

strategic implications of direct sellers, such as e-tailers,

competing with traditional retail channels (Balasubra-

manian 1998). Motivation for mixed channel structures

and a different type of consumer heterogeneity across

channels has been studied by Yoo and Lee (2011). How-

ever, to our knowledge, decision-stage heterogeneity

and self-matching policies have not been examined in

this setting.

We denote the focal multichannel retailer as retailer 1

and the online-only e-tailer as retailer 2. In this setting,

only retailer 1 can offer a self-matching policy in stage 1

of the game. Subsequently, both retailers set prices and

compete for demand per the timeline in Figure 1.

First, consider the case wherein the multichannel

retailer does not self-match its prices. Store-only con-

sumers can only consider retailer 1’s store channel and

are captive to this retailer, whereas channel-agnostic

consumers have the option of shopping across the two

retailers’ online sites. Profits for both retailers can be

expressed as follows:

⇧

0, 0

1

⇤ ⌘

1

(p

on

1

, p

on

2

)p

on

1

| {z }

Channel-Agnostic Decided and Undecided

+ (1 ⌘)p

s

1

| {z }

Store-Only Decided and Undecided

, (4)

⇧

0, 0

2

⇤ ⌘(1

1

(p

on

1

, p

on

2

))p

on

2

| {z }

Channel-Agnostic Decided and Undecided

.

Retailer 1 serves as an effective monopolist for store-

only consumers (SD and SU segments), who comprise

a combined segment of size 1 ⌘, and will attempt to

extract surplus from them by setting a store price of

ˆ

p

s

1

⇤ v ✓. Note that by contrast to the multichannel

duopoly, store-only decided consumers do not drive

down prices in the mixed duopoly case because the e-

tailer does not have a store that serves as a competitive

option. Both retailers compete online for the channel-

agnostic consumers, who form a segment of size ⌘.

We allow for channel-agnostic undecided consumers

who are closer in preference to retailer 2, the e-tailer,

to browse the product category at retailer 1’s store and

then purchase online from the e-tailer. The equilibrium

online prices are at the competitive level, with

ˆ

p

on

1

⇤

ˆ

p

on