TRADE,

ECONOMY,

AND WORK

Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies

U.S.-MEXICO

FORUM 2025

2

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS

Restore a cabinet-level economic

dialogue to institutionalize cooperation

and drive progress across the many

facets of the bilateral economic

agenda.

The USMCA creates pathways for

both cooperation and disputes. Focus

rst on strengthening cooperation as

both a way to address challenges and

improve regional competitiveness.

Strengthen regional supply chain

security by aligning essential industries

and establishing protocols for

emergency response.

Create a regional workforce

development dialogue. Technology is

quickly changing the future of work,

and a coordinated response is required.

Put sustainable development and

inclusive growth at the center of the

bilateral economic agenda. To maintain

public support for regional integration,

these shared challenges must be

adequately represented.

Support subnational leaders‘

involvement in the binational economic

relationship.

The nal section of this paper provides

a more detailed and complete set of

recommendations.

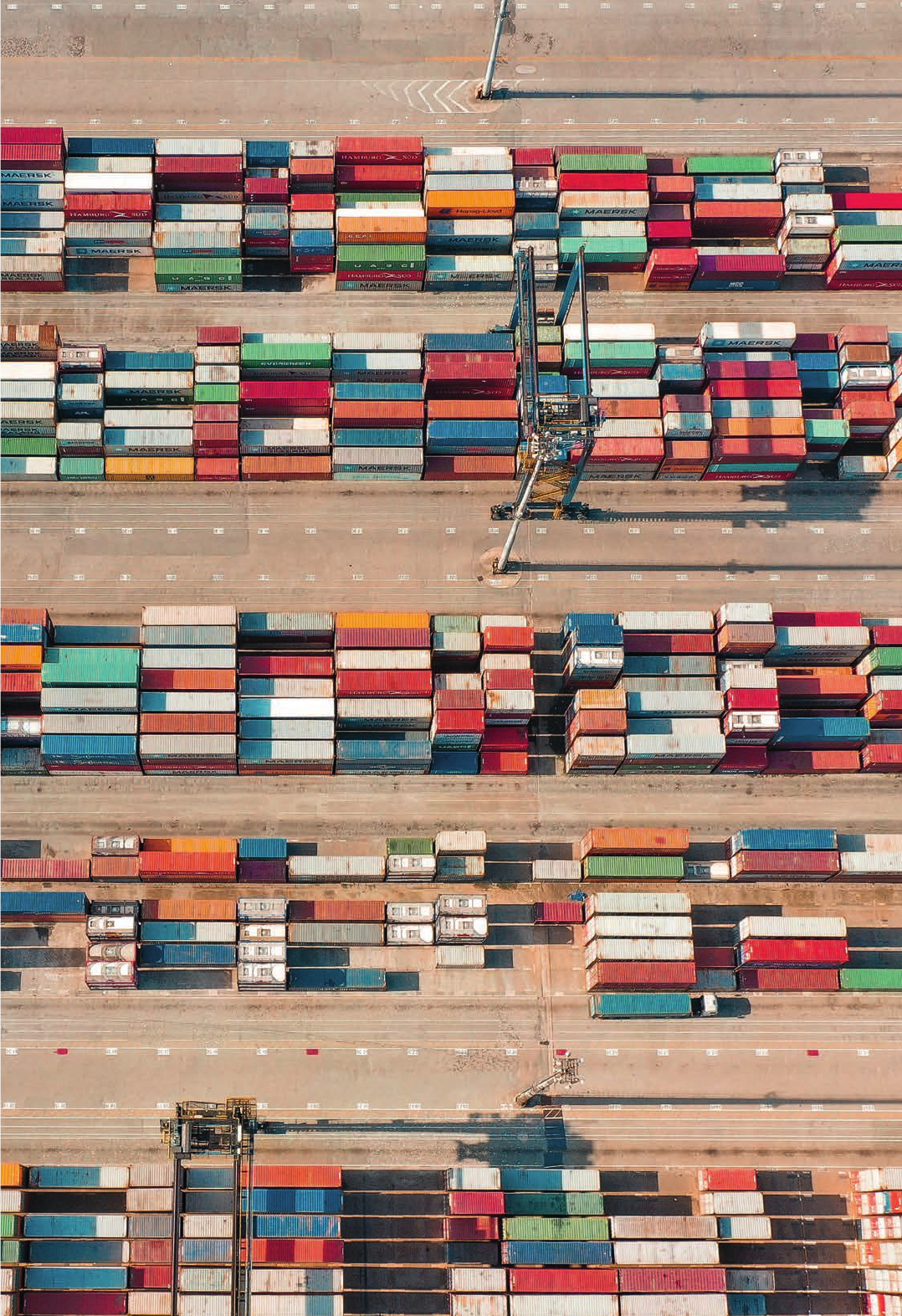

The economies of the United States and Mexico are deeply connected.

The United States is, by far, Mexico’s top trading partner, and Mexico is the

United States’ second largest partner.

1

While cross-border trade volumes

are massive, it is the depth of manufacturing integration that makes the

U.S.-Mexico economic partnership unique. A full half of bilateral trade is in

inputs for production, parts and materials moving back and forth across

the border as the two nations co-produce everything from automobiles to

beer.

2

Economic and productive integration, which has been fostered by the

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and now the United States-

Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), has synced the U.S. and Mexican

economies, which now tend to experience cycles of growth and recession

together. Deeper still, our competitiveness is linked. Through manufacturing

integration, the United States and Mexico can divide production in ways that

take advantage of their competitive advantages, strengthening the region.

In this way, the economic interests of Mexico and the United States have

become closely aligned. Productivity enhancements on one side of the

border strengthen the competitiveness of the region as a whole, and

despite the fact that there are cases in which an investment won on one

side of the border means an investment lost on the other, research shows

that it is more common for companies to simultaneously create jobs on

both sides of the border as they expand their investment in the regional

economy.

3

In the United States, some ve million jobs depend on trade with

Mexico, and a similarly large number of jobs in Mexico depend on trade

with the United States.

4

The ratication and implementation of the USMCA updated and restored

certainty to the system of regional trade and production, and the conclusion

of the renegotiation process opened space for the development of a new

bilateral (and with Canada, a trilateral) agenda for economic cooperation.

The USMCA was passed with broad support from representatives of every

major political party in the U.S. and Mexico, providing a stable platform for

the future of bilateral economic relations.

As the United States and Mexico each seek to stimulate recovery

domestically and prepare for economic transformation, they need to keep

in mind that the depth of North American integration makes job creation

and export growth largely regional enterprises. This short paper will explore

these challenges, examine the impact of changes to the regional economic

framework through the USMCA, and propose a series of measures the

United States and Mexico can take together in the coming years to

strengthen the regional economy.

A Challenging and Quickly Evolving Economic Outlook

The U.S. and Mexican economies, like others around the world, face

huge challenges as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. GDP for

2020 declined 4.3% and the IMF has forecast a much steeper 9% drop for

Mexico. The pandemic induced recession will force millions into poverty

1. https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/highlights/top/top2008yr.html

2. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/nal-report-growing-together-economic-ties-between-the-

united-states-and-mexico

3. Theodore H. Moran and Lindsay Oldenski, “How U.S. Investments in Mexico have increased investment

and jobs at home” in NAFTA 20 Years Later, Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International

Economics, November 2014

4. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/nal-report-growing-together-economic-ties-between-the-

united-states-and-mexico

U.S.-MEXICO FORUM 2025

Trade, Economy, and Work

A Shared Agenda for a Stronger Economic Future

Álvaro Santos and Christopher Wilson

3

in each country, increase internal inequality, and, because

of the dierence in the magnitude of recession expected

in each country, only serve to widen the development gap.

Reactivating the regional economy and recovering from the

recession will be the principal economic challenges facing

both the United States and Mexico for the next several

years.

Many possible options, such as scal stimulus and monetary

policy, are essentially domestic in nature, but there are

important matters of shared concern and even opportunity.

Both governments ordered the temporary closure of

activities not deemed “essential,” but a lack of cross-

border coordination, initially caused disruptions even to

critical industries such as medical device manufacturing.

In contrast, the U.S. and Mexican governments worked

closely together and jointly announced restrictions on non-

essential travel across the border. With border towns and

cities suering from the resulting economic slowdown, they

will need to coordinate just as closely to nd ways to safely

reopen the border.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, many companies

are reevaluating their global production networks and

prioritizing supply chain security and resilience as a result

of U.S.-China trade tensions and the pandemic. This oers

North America a tremendous opportunity to reshore

investment to the region, but it is an opportunity that could

be missed if the right policies and programs are not in place

to attract and welcome that investment.

Though accelerated by the pandemic, digital transformation

and automation have been roiling labor markets and rapidly

changing demand for skills for many years. Many workers,

especially in manufacturing and energy industries, but

increasingly in oce jobs, have been left behind as the

economy evolves before them. The U.S. and Mexico must

nd ways to support major improvements to our workforce

and skills development systems in order to maximize

regional competitiveness and ensure that all workers have a

place in the 21st Century North American economy.

Similarly, the demand for climate change action is more

urgent than ever. The response to this challenge is

especially important in the energy sector, and the U.S.-

Mexico Forum has a working group that has put together a

comprehensive strategy on sustainable development and

energy systems. Economic development and environmental

protection, including both climate change mitigation and

adaptation, cannot be divorced.

In the border region, the importance of addressing issues

of water scarcity became abundantly clear this year when

social unrest erupted in Chihuahua at the Boquilla Dam

as Mexico struggled to meet its water transfer obligations

under the binational water treaty. Ultimately, cooperation

prevailed but the challenges of resource scarcity will only

grow. Border region leaders will need to work together to

design and implement strategies that meet the economic

and environmental needs of their communities.

There is a huge potential for this type of cooperative

5. David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson, “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Eects of Import Competition in the United States,” National Bureau of Economic

Research Working Paper 18054, Cambridge, MA: NBER, May 2012, pp. 20-21, http:// www.nber.org/papers/w18054.

cross-border economic development in the border region.

Well over a billion dollars in commerce crosses the border

each day, and the GDP of the six Mexican and four U.S.

border states is larger than the GDP of all but the three

largest countries in the world. To take full advantage of

this opportunity, the U.S. and Mexican governments need

to facilitate and support greater cross-border cooperation

among state and local ocials in the region. Initiatives like

the Border Governors Conference, which has not met for

several years, and the Border Mayors Association need

robust support.

Fueled by growing gaps in income inequality, populism,

and economic nationalism have grown around the world

in recent years making regional and global cooperation

more dicult to pursue. In Mexico, this is evidenced by the

signicant productivity gap between globally connected

manufacturing and the rest of the economy. Persistent

underinvestment in the poorer south, limited development

of homegrown startups, and an insucient focus on

expanding the domestic supplier base for manufacturing

exporters have each contributed to the challenge. In the

United States, the decline of manufacturing employment

over the past several decades has contributed signicantly

to the rise of economic nationalism. Productivity enhancing

technology and the globalization of production, in particular

the insertion of China into global value chains, has increased

the pressure on low- to middle-skilled manufacturing

workers.

5

In both countries, domestic policy issues such

as taxation, education and workforce development, and

health are among the most important tools to address

problems related to income distribution, and North

American cooperation can play an important role in creating

opportunities for and protecting workers across the region.

Despite the prominence of trade skepticism heard in

both countries, the reality of the U.S.-Mexico economic

relationship is that we are stronger together. The deep

integration of the manufacturing and other productive

networks across the U.S.-Mexico border binds our economic

futures. Our region faces big challenges caused by the

coronavirus pandemic as well as deeper structural shifts. In

such challenging times it is easy to look inward and prioritize

domestic issues, but to do so would be a mistake, for both

countries. We must instead work together and embrace the

complementarities of our economies in order to strengthen

our global competitiveness and build a 21st Century

economy that works for everyone in each of our countries.

Trade, Supply Chains, and Work under the

New USMCA

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA),

eective since July 1, 2020, ended the uncertainty triggered

by the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade

Agreement (NAFTA) and the threat of its elimination. The

USMCA provides continuity with NAFTA on many fronts and

provides governments and market actors in North America

with a framework where they can operate with certainty.

... the reality of the U.S.-Mexico economic relationship is that we are

stronger together.

“

4

Estimates for USMCA’s growth impact on the U.S. economy

are very small. The U.S. International Trade Commission

estimated them around GDP 0.35% or $68.2 billion in the rst

six years. Although the Mexican government has referred to

it as an important element of its overall economic strategy,

there haven’t been similar estimates of the economic impact

of USMCA. The low estimates reinforce the importance

of holding realistic expectations about USMCA’s potential

in regard to economic growth. It also makes clear that

USMCA will not on its own solve the issues of economic

growth. Governments need to build on the structure

already constructed under NAFTA and further enhance and

“technologize” the private sector networks and the cross-

border infrastructure and processing to stimulate growth.

USMCA came into an environment signicantly dierent

from the free trade optimism that ushered in NAFTA twenty-

ve years before. Concerns about the eects of trade, the

deepening asymmetries between capital and labor, and

increasing economic inequality have fueled much of the

discontent against free trade agreements of the last three

decades in both poor and rich countries alike.

6

The U.S.

took an aggressive oppositional stance toward “globalist”

trade policy, withdrawing from TPP, starting a tari war with

China, renegotiating NAFTA and several bilateral trade

agreements, and using national security taris against

trading partners. And while these changes were executed

under the Trump Administration, both Hillary Clinton and

Bernie Sanders vowed to withdraw from the Trans-Pacic

Partnership (TPP) and renegotiate NAFTA if they had been

elected. The trade and investment agenda of the Biden

campaign — and of the incoming Biden administration —

make clear that many changes in U.S. policy are here to

stay. There will be continued attention to job creation in the

U.S., to the well-being of American workers, to discouraging

oshoring and investment abroad, and to encouraging

onshoring and investment at home.

NAFTA achieved an unprecedented economic integration

in North America, but its overall welfare eects fell far short

of what was expected. While ows of trade and investment

increased dramatically between the U.S. and Mexico, their

eect on growth was disappointing. During 1994-2016,

Mexico’s GDP per capita grew only 1.2% on average per year,

among the lowest in Latin America.

7

Mexico’s wages lagged

behind productivity, even in the successful, export-oriented

manufacturing rms.

8

In fact, the apparent paradox between

Mexico’s liberalization program heralded by NAFTA and its

underwhelming, domestic overall economic eects should

serve as warning about the connection between trade and

growth.

9

Instead of convergence with the U.S., Mexico has

experienced further divergence where it matters most.

Mexico’s GDP per capita is no higher relative to the U.S. than

it was in the years preceding NAFTA and labor productivity

is farther behind relative to the United States’ than in the

pre-NAFTA years.

10

While not all of the Mexican economy’s

virtues or ills can be pinned on NAFTA, it is clear that NAFTA

reshaped the Mexican economy and that subsequent

6. See, e.g., WORLD TRADE AND INVESTMENT LAW REIMAGINED: A PROGRESSIVE AGENDA FOR AN INCLUSIVE GLOBALIZATION (Álvaro Santos, David Trubek and Chantal

Thomas eds., Anthem Press 2019).

7. “Did NAFTA Help Mexico? An Update After 23 Years” Mark Weisbrot et al. Center for Economic and Policy Research (March 2017) https://www.cepr.net/images/stories/

reports/nafta-mexico-update-2017-03.pdf?v=2

8. Robert A. Blecker, Juan Carlos Moreno-Brid and Isabel Salat, “La Renegociación del TLCAN: La Agenda Clave

Que Quedó Pendiente” in La Reestructuración de Norteamérica a Través del Libre Comercio: Del TLCAN al TMEC (Oscar F. Contreras, Gustavo Vega Cánovas y Clemente Ruiz

Durán eds. 2020).

9. See Dani Rodrik, “Mexico’s Growth Problem”, Project Syndicate, Nov. 13, 2014 https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/mexico-growth-problem-by-dani-

rodrik-2014-11. See also See Nancy Birdsall, Dani Rodrik & Arvind Subramanian, How to Help Poor Countries, FOREIGN AFF., July/Aug. 2005, at 138.

10. Robert. A. Blecker, “Integration, Productivity, and Inclusion in Mexico: A Macro Perspective”, in Innovation and Inclusion in Latin America: Strategies to Avoid the Middle

Income Trap (Alejandro Foxley and Barbara Stallings eds. 2016) pp. 175- 204.

11. Oce of the U.S. Trade Rep., Exec. Oce of the President, Agreement between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada 05/30/19 Text (2018)

[hereinafter USMCA]. Ch. 4, app. to annex 4-B, Product-Specic Rules of Origin for Automotive Goods, art. 3.

12. Id. art. 4-B.7.

13. Id. arts. 4-B.3.7. and 4-B.6.

14. Enrique Dussel Peters, Efectos del TPP en la Economía de México: Impacto General y en las Cadenas de Calor de Autopartes-Automotriz, Hilo-Textil-Confección y Calzado,

Cuaderno de Investigación TPP-04, Senado de la República, 2017,p.24 https://dusselpeters.com/115.pdf

Mexican governments were not able to advance policies

that capitalized on the opportunities or tempered the

resulting asymmetries.

The new USMCA and the changes in U.S. policy will no

doubt bring challenges but also oer an opportunity to

focus on the distributional consequences of trade and

investment, which had been largely ignored, and on the

overall eects for the economy. For Mexico, this will oer

an opportunity to devise its own development strategy

without expecting USMCA to deliver it. If NAFTA oers one

clear lesson, it is that increasing (and now maintaining) trade

and investment ows is not a growth strategy. USMCA will

allow both countries to focus on domestic economic policy

while maintaining the potential benets of a high degree of

regional integration. For now, changes in USMCA on rules

of origin, investment and labor may portend a new direction

in U.S. policy for future trade agreements. Even if, for now,

USMCA preserved much of NAFTA, it may continue to

change as a result of future review cycles, now embedded

in the operation of USMCA by design. Below, we discuss the

most relevant changes USMCA has introduced.

1. Rules of Origin (ROO)

It is important to note that rules of origin in most sectors,

such as electronics and textiles, were maintained. This

ensures the continuity of most regional value chains

undisturbed. The most notable change came in the

automobile industry. Here, three aspects are noteworthy:

y The regional value content (RVC) requirement increased

from 62.5% to 75%, which means that the percentage of

non-regional content allowed dropped by 33.3%.

11

y A labor value content (LVC) requirement was that 40% of

the value of the car is manufactured with wages of at least

$16 dollars per hour.

12

y Certain automobile parts and components must be wholly

produced in the region and 70% of aluminum and steel

content should originate in the region.

13

The rules of origin for autos and auto parts agreed upon

in USMCA stand in stark contrast with those that had

been negotiated in TPP, which were considerably lower

than in NAFTA. This provides some relief to Mexican car

manufacturers in terms of the anticipated competition

with other TPP countries in the U.S. market. However, the

higher USMCA content requirement also presents important

challenges, given that an important share of inputs in

Mexican production come from outside North America.

14

An important question going forward is whether U.S. and

Mexican auto makers will be able to meet the higher

USMCA content requirement.

The new 75% regional value content aims to incentivize

greater production in North America and away from

5

other global value chains, notably from Asia. This may

present an opportunity for Mexico, if Mexican auto parts

suppliers expand the range of their production to include

additional inputs currently imported from outside the

region. Alternatively, global auto parts suppliers could move

production to Mexico so that their parts could be counted as

North American. Analysts estimate that 68% of production in

Mexico already meets the new content requirements.

15

An

open question is whether those rms who don’t meet these

requirements would adjust their production or opt out of

USMCA and abide by the U.S. most-favored-nation (MFN)

tari, which for autos is 2.5%.

The new 40% labor value content seeks to ensure that

the United States benets from a signicant part of the

production increase. Of this 40%, 15% can relate to research

and development, and information technology jobs, while

25% must relate to manufacturing costs. In Mexico, the

average wage rate in auto assembly ranges between $5

and $7 per hour,

16

while engineering and research and

development jobs already meet or are close to the $16

per hour requirement. This means that it will be practically

impossible for auto companies in Mexico to meet the $16

wage requirement in 25% of their production content, which

would have to come from the U.S. or Canada.

Analyses of the eects of the new ROO raise concerns

about possible increase in car prices, as cheaper parts from

other supply chains are substituted for more expensive

North American ones. A rise in consumer prices could

reduce demand and in turn lead to a production drop and

potential job losses.

17

2. Labor Rights and Labor Panels

The USMCA had three important features concerning labor

rights. First, the labor chapter included new state obligations

such as prevention of violence against workers, prohibition

on gender discrimination, and protection of migrant workers.

It also included an explicit recognition of the right to strike as

a component of the right to freedom of association.

Second, the labor chapter’s Annex includes a commitment

by Mexico to reform its labor laws and institutions. Mexico

adopted its new law on May 1, 2019 and is now in the

implementation phase. The reform i) establishes a new

dispute settlement system under the jurisdiction of Mexican

courts and eliminates the administrative labor conciliation

and arbitration boards, ii) creates an autonomous center for

labor conciliation and registration, which will register unions

and collective agreements, taking that function away from

the government, and iii) entrusts that center with verifying

that elections — deciding union leadership and majority

support of collective agreements — are personal, free,

direct and secret.

15. USMCA: Motor Vehicle Provisions and Issues, Congressional Research Service, Dec. 19, 2019. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11387

16. “Only 269,000 Mexicans earn more than US $16 per hour, or 308 pesos” Mexico News Daily, Aug. 30, 2018.

https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/only-269000-mexicans-earn-more-than-16-per-hour

17. See e.g. USMCA: Motor Vehicle Provisions and Issues, Congressional Research Service, Dec. 19, 2019. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11387

18. Graciela Bensusán, Empleos en México bajo presión: con o sin TLCAN, en LA REESTRUCTURACIÓN DE NORTEAMÉRICA A TRAVÉS DEL LIBRE COMERCIO: DEL TLCAN AL

TMEC (Oscar F. Contreras, Gustavo Vega Cánovas y Clemente Ruiz Durán.

Finally, the Protocol of Amendment created a new

expedited enforcement mechanism called the Rapid

Response Panels. This mechanism allows for review and

remediation of a denial of rights in a relatively short process

(120 days). The panelists may verify whether a violation

exists by visiting the facility in question. When a violation is

conrmed and goes unredressed, the complainant country

may impose sanctions on the goods produced in violation

of the agreement, including higher taris, nes, or denying

entry.

The changes introduced by USMCA will require

important adjustments in Mexico. If the federal labor

law is implemented eectively, workers would be able

to associate, form independent unions and bargain

collectively, in a way they have not been able to do for

decades. It could mean the end of widespread simulation

in the form of “protection contracts” between corrupt

union leaders and rms, where workers didn’t choose

their union or even know they belong to one. It would

also mean the end of government intervention in union

governance, intimidation or outright violence in voting for

crucial decisions, and a biased dispute settlement system.

A striking feature in the Mexican economy is that wages

declined not only in those rms that fell behind or in sectors

that failed to integrate, but also in the most successful,

export-oriented rms, which were highly integrated in

the North American market, where wages fell behind

productivity.

18

The labor reform could gradually result in

better wages for Mexican workers. Higher wages could

incentivize employers in various export sectors to rely

less on cheap labor as their main competitive advantage

and instead seek to add value in the production chain,

innovating in their products, process of production or

business strategies. Workers with greater incomes would

also stimulate domestic demand. It is early to tell but signals

so far seem to indicate that while at the federal level the

reform is proceeding as planned, at the state level there

may be more hurdles and less political will.

Statements from the United States Trade Representative

(USTR) and the American Federation of Labor and Congress

of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) indicating that they

expect to use the rapid response panels against Mexico

suggest that the mechanism will be tested in the near

future. As the experience of the World Trade Organization

has made clear, an excessive focus on dispute settlement

and strategic litigation could hamstring attempts to address

systemic problems. Adjudication could solve specic cases,

and it needs to be eective, but it is only one tool among

others in making sure commitments are enforced on both

sides.

Changes in USCMA labor rights was good news for

U.S. workers for at least two reasons. First, because it

incorporated the American labor movement concerns about

Changes in USCMA labor rights was good news for U.S. workers ...

“

6

social dumping, and it lended legitimacy to their concerns

about the distributional eects of trade. And second,

because it showed that the concerns of American workers’

organizations can be included, rather than excluded, in

trade negotiations and policy.

3. Changed Investment Regime and Reduction of Investor

Rights

USMCA introduced important changes in the investor-state

dispute settlement system (ISDS). The scope of investors’

rights was reduced to a “skinny” ISDS, which preserves

protection from direct expropriation and discriminatory

treatment but eliminates other rights under NAFTA. A new

requirement was that local remedies be exhausted before

investors can resort to arbitration. However, investors with a

“covered government contract” in specic sectors including

oil and natural gas, power generation, telecommunication,

transportation, and infrastructure enjoy the full panoply

of rights and can resort to arbitration without going rst to

national courts.

The reduction of rights responds to increasing concerns

about the investor-State dispute settlement system (ISDS)

in both developed and developing countries.

19

The USMCA

may indicate a new direction in trade agreements regarding

ISDS. The benet for U.S. and Mexico is the avoidance of

regulatory chill for fear of potential investor claims in areas of

public interest such as health and the environment, and the

prevention of costly liability and litigation costs for legitimate

regulation.

4. Digital Trade

USMCA liberalized the cross-border movement of data,

making the importation and exportation of digital products

duty free. It recognized the importance of measures to

protect consumers from fraudulent practices and protect

individual personal data. Furthermore, it outlawed data

localization requirements that made the establishment of

physical computing facilities a condition of doing business in

that country.

But there are two sources of tension. First, USMCA prevents

parties from assigning liability to internet service providers

for content placed on their platforms by third parties. Given

mounting concerns about fake news and disinformation

campaigns in social media platforms, we may see stricter

regulation in the U.S and the need to revise the USMCA

on this front. A second area of potential tension concerns

mechanisms for taxation of digital sales, which are allowed

under the USMCA as long as they are otherwise consistent

with the agreement. An important question is whether there

could be an evolving consensus on acceptable taxing

practices for digital companies, or if these would be ad hoc

understandings of dierent countries with the U.S., since

most of the aected global digital companies are American.

This may be a subject worth addressing in the context of the

USMCA Trade Commission.

Digital trade may oer an opportunity for small and medium-

size companies in Mexico to participate in regional trade

as service providers, in areas like cloud storage, ntech, or

software development.

5. Review Mechanism

While the U.S. original proposal for a ve-year sunset clause

did not make it to the nal text, USMCA is eective for a

renewable sixteen-year term (Article 34.7). On year six of the

Agreement (2026), the Free Trade Commission will meet to

conduct a “joint review” and the Parties may conrm they

19. See e.g. Robert Howse, International Investment Law and Arbitration: A Conceptual Framework in INTERNATIONAL LAW AND LITIGATION (H.R. Fabri ed., 2017).

https://www.iilj.org/publications/international-investment-law-arbitration-conceptual-framework/

want to renew the Agreement for another sixteen-year

term. If a party does not renew the Agreement on year six,

the Commission will meet and conduct a review every

year during the subsequent ten years, in which the parties

may conrm at any point their desire to renew it for another

sixteen-year term.

This term-specic feature of USMCA may create uncertainty

about the long-term continuation of the Agreement

and reduce incentives to invest in large-scale projects

that require big, upfront expenditures with expected

returns spanning many years. However, unlike NAFTA,

this mechanism provides an opportunity to evaluate the

operation and eects of the Agreement and to update

or amend it accordingly. By institutionalizing the review

process parties may be able to clarify interpretations when

there is doubt and to correct course if something is not

operating as expected.

How the U.S. and Mexico Can Work

Together to Take Advantage of this New

Framework

1. Work Together to Attract Auto Investment to the

Region

The biggest challenge for the industry is the possibility of

increasing production costs, which would result in higher

car prices, reducing consumer demand in North America

and competitiveness in export markets. Recently, the U.S.

and Mexico adopted alternative staging regime transition

periods to provide more exibility for companies aiming to

comply with the new rules. Both countries could use the

information received in companies’ applications to assess

the rules’ potential impact and ne-tune the strategy. This

could help governments minimize the potential negative

eects of the requirements, and consider longer transition

periods and possible exceptions. Evaluating the impact

of these rules of origin should be a priority in the review

process six years in.

2. A Coordinated China Strategy—Attracting Investment,

Managing Risks, Expanding Exports

The Transformation of Global Value Chains: We can

expect to see the continuation of a signicant transformation

in global value chains (GVC). The competitive race in the

digital economy and its telecom infrastructure will continue

to shape GVC and be a source of tension between the

U.S. and China. At the same time, the general U.S.-China

tensions, exemplied by the trade war, and the COVID-19

pandemic could make near-shoring increasingly relevant for

the U.S. and North America.

Mexico in the Context of U.S.-China Tensions: In USMCA,

Mexico committed to continue and to deepen its economic

integration with North America. On the other hand, Mexico

has an important trade relationship with China (its second

trading partner after the U.S.). Ideally, Mexico should

maintain both a deep and long-term relationship with the

U.S. and independent space to engage with China. USMCA

Article 32.10 provides that if a party enters into a free trade

agreement with a non-market economy, namely China, the

other parties may terminate the USMCA and replace it with a

bilateral agreement between them. This is another example

of how the growing U.S.-China tensions are inuencing trade

agreements. However, Mexico should be able to continue

to develop its trade and investment relationship with China,

without the need of a formal free trade agreement.

7

Mexico has seen a temporary benet in its trade relationship

with the U.S., becoming the latter’s rst trading partner as a

result of the tensions with China. Mexico’s potential benet

from the current tari war would depend on China’s share

in U.S. imports. There are ten sectors where Mexico could

benet, including electronics, auto parts, automobiles,

footwear, and apparel, among others (Dussel). However,

the trade gains for Mexico in terms of greater imports to

the U.S. so far have been minimal and FDI from the U.S. (or

China) has not increased. Taking advantage of this potential

opportunity would require a deliberate strategy from the

Mexican government and a coordinated strategy with the

private sector not seen yet. If the U.S. taris continue, there’s

also the potential of Chinese investment in Mexico in some

of these areas entering the U.S. market bypassing U.S. taris.

Again, whether this investment materializes, in the auto

sector or elsewhere, may depend not only on the incentives

that the new U.S. taris create for Chinese companies, but

on a deliberate strategy by the Mexican government.

Opportunities for Reshoring in North America and Greater

Integration with the U.S.: It is possible, though not certain,

that the Biden Administration will de-escalate the current

tari war with China, which has in fact increased the U.S.

trade decit. If the U.S. were to remove taris, it is unclear

when this would happen and in what sectors. What is

more certain is that the Biden Administration will launch a

“Supply America” plan to on-shore critical supply chains to

the U.S. and reduce dependence on China. This is part of a

broader plan on manufacturing and innovation, including

signicant investments in research and development. The

program seeks to strengthen domestic supply chains on

medical goods and equipment but goes beyond health

emergencies to include “energy and grid resilience

technologies, semiconductors, key electronics and related

technologies, telecommunications infrastructure, and key

raw materials.”

20

There will be a government-wide process,

in collaboration with the private sector, to monitor and

review vulnerabilities and address them as technology and

markets evolve.

A shift away from manufacturing dependency on China,

already visible in the auto sector in USMCA, can represent

an opportunity for North American supply chains, and for

Mexico specically, to take on some of that production.

Particularly if Mexico eectively implements its labor reform

and its manufacturing exports can no longer be perceived

as “social dumping”, Mexico’s proximity to the U.S., reliance

on a robust supply-chain infrastructure, qualied workforce

in manufacturing, and competitive labor costs could make it

attractive as a second-best to on-shoring, when producing

in the U.S. would make prices non-competitive.

3. Use Competitiveness Committee to Institutionalize

Further Trilateral Cooperation

Established by USMCA Chapter 25, the North American

Competitiveness Committee is composed by government

representatives of the three Parties and is scheduled to

meet annually. The committee’s mandate is broad, aiming

to “support a competitive environment” that promotes trade

and investment, but also regional economic integration

20. https://joebiden.com/supplychains/

21. See e.g. “Economic Impacts of Wait Times at the San Diego–Baja California Border,” San Diego Association of Governments, California Department of Transportation, District

11, January 19, 2006.

and development. It seeks to broaden the base of those

who benet from regional trade, assisting traders in each

party to identify further opportunities but also increase

the “participation of SMEs, and enterprises owned by

under-represented groups including women, indigenous

peoples, youth, and minorities.” It also seeks to propose

policies to develop a modern physical and digital trade and

investment infrastructure, as well as to foster cooperation on

technology and innovation.

As with any committee, it will be as good as the Parties

make it out to be. This could be a useful institutional

mechanism, which already foresees the engagement

with “interested persons” who can provide input. The U.S.,

Mexico, and Canada could use this committee to provide a

wide forum among the three nations, engaging the private

sector, labor, and civil society to receive important feedback

and ensure continued support for the Agreement. This will

not happen on its own and there may be inertia or even

resistance, so there will need to be a deliberate eort to

advance it and make the committee a relevant forum for the

governments and for civil society.

USMCA creates multiple committees, all under the purview

of supervision of the Free Trade Commission (Ch. 30). While

some of the committees pertain to specic trade areas

(i.e. agriculture, intellectual property, nancial services,

etc.), others are more general and cut across sectors. For

instance, in addition to the Competitiveness Committee,

there’s the Committee on SME Issues (Ch. 25), which is also

comprised of government representatives and scheduled to

meet annually. It foresees a trilateral dialogue on SMEs with

non-governmental actors. These more general committees

provide a space and a mechanism but don’t have ready-

made stakeholders. To ensure the eectiveness of the

USMCA institutional architecture, it will be important to

clarify the relationship between the dierent committees

and use these mechanisms to foster trilateral cooperation

on priorities.

4. Trade Facilitation and Cross-Border Infrastructure

There are 55 points of entry along the U.S.-Mexico border,

which process more than 80% of bilateral trade. With over

one million people and 447,000 vehicles crossing every

day, it is the most frequently crossed border in the world.

The U.S. and Mexico have an opportunity to streamline their

trade, implementing the new obligations under the USMCA

Customs Administration and Trade Facilitation chapter. In

addition, they should invest in infrastructure, both physical

and digital, to reduce wait times at the border that result in

billions of dollars lost.

21

Upgrading the ports of entry to build

a smart and ecient border that reects the dynamic trade

ows of the two countries could be a low-hanging fruit

where investment would yield important returns for both

countries.

There are ten sectors where Mexico could benet, including electronics,

auto parts, automobiles, footwear, and apparel ...

“

8

Beyond USMCA: An Agenda for Economic

Cooperation

As discussed above, the USMCA plays a critical role in

guaranteeing the future of North American trade and

manufacturing integration. It oers opportunities to attract

investments to the region and to eectively manage

conict in sensitive sectors. Nonetheless, it is not on its

own an economic growth strategy or a sucient bilateral

economic agenda. In fact, the intensity of the NAFTA

renegotiations over the past several years took so much

policymaker attention that other parts of the U.S.-Mexico

economic agenda lost steam. The High Level Economic

Dialogue (HLED), which coordinated this broader agenda,

did not survive the transition to the Trump Administration

in Washington, D.C., and the launching of the USMCA

negotiations. Now, with the USMCA passed and

implemented, it is time to create a new mechanism to

institutionalize and manage economic cooperation. To

be successful, however, this cannot simply be an exercise

in recreating the past. We must build institutions that are

capable of responding to the pressing economic challenges

of today and the opportunities on the horizon.

The new economic dialogue could be bilateral or trilateral

and North American in nature. In either conguration, three

components are needed to ensure its success. First is

leadership. The mechanism needs to be driven by cabinet-

level leaders that have the vision and energy to push

through bureaucratic bottlenecks and create meaningful

results that improve the lives of people on both sides of

the border. Second, a series of binational working groups

and councils need to be created to help design and then

drive progress on the agenda during the periods between

cabinet-level meetings. These groups need representation

from the wide range of agencies that must coordinate

eorts. Third, and importantly, robust mechanisms need

to be created to involve stakeholders and subnational

governments in the dialogue. The USMXECO CEO Dialogue

played an important role in generating ideas and helping

support initiatives of the HLED. Strong private sector

participation will again be very important, but outreach

needs to be stronger with civil society, labor, border

communities, and subnational governments both in the

border region and beyond. The importance of involving

border communities and subnational governments

from across both countries in the development and

implementation of U.S.-Mexico economic cooperation

cannot be overemphasized.

The rst task is to construct the agenda. It must be

ambitious and respond to the economic needs of average

people across the region. It needs to include elements

that the presidents could talk about in the Rose Garden or

National Palace. High prole issues such as job creation,

reducing inequality, and the climate crisis should be the

drivers of more specic and discrete tasks like improving

trade infrastructure, aligning regulation, or expanding

educational and research partnerships.

The rst component of any updated U.S.-Mexico economic

agenda must be to respond to the challenges (and

opportunities) presented by the COVID-19 pandemic and

related recession. The integration of cross-border supply

chains has created a deep level of interdependence

between the United States and Mexico; we supply one

another with medical devices that keep us safe during this

time, with vital food products, and with parts and materials

that allow factories on the other side of the border to keep

running. As such, the United States and Mexico must

create mechanisms to ensure that any future emergency

measures that impact production or logistics capacity be

at a minimum communicated and ideally coordinated with

ocials on the other side of the border. To the extent that

the governments of North America can align their denitions

of essential industries, they can increase their likelihood of

attracting investment from companies looking to strengthen

their supply chain security and resilience. Already, as a

result of pandemic-related supply chain disruptions and

increasing trade tensions between the United States and

China, companies are seeking to shorten and improve

reliability along their supply chains. The United States

remains the most attractive consumer market in the world,

so these dynamics create a strong incentive for greater use

of the North American production platform. To the extent

that the governments of North America can ensure investors

that they have developed systems to minimize disruption

during future crises, they will position themselves to take full

advantage of this trend.

NAFTA, just like economic globalization more generally, was

often portrayed by its critics as good for business elites but

not workers and impoverished communities. The reality may

be more complicated, but without a doubt the perception

left NAFTA vulnerable to attack and inherently unstable.

The strengthening of labor and environmental components

of NAFTA in the USMCA will help mitigate these attacks

in the future, but the United States and Mexico need to

develop a strategy of cooperation for inclusive growth. This

includes doing more to support greater participation of

small and medium sized businesses in regional trade. The

proliferation of e-commerce and ease of express shipping

make this more realistic than ever, but the prospect of

nding customers abroad and dealing with the customs

and logistics issues involved in international shipping

is still a major barrier. Border communities, which have

some of the highest rates of poverty in the United States,

need the support of the U.S. and Mexican governments to

develop and implement binational economic development

strategies that see their position on the border, with their

binational, bilingual, and bicultural populations, as an asset

to be leveraged for their development. Binational programs

to support women entrepreneurs, the development of

innovation ecosystems, and cross-border internships should

all be updated and revitalized.

The most important thing that can be done to promote

inclusive growth in the regional economy is an overhaul

of worker training systems. Rapid technological change,

more than anything else, has changed the labor market

THE IMPORTANCE OF INSTITUTIONS IN

U.S.-MEXICO RELATIONS

The United States and Mexico have an exceedingly

complex and broad relationship, encompassing

not only traditional issues of foreign policy but

also domestic matters such as the construction of

city roads to facilitate access to border crossings.

Achieving progress often requires the coordination

of actions from local, state, and federal actors from

across numerous agencies in both countries. Driving

coordination and overcoming bureaucratic obstacles

requires leadership from the highest levels, but also

working groups with the technical capacity to solve

problems. Institutions like the High Level Economic

Dialogue create synergy between these two levels,

with leaders providing the impetus to break through

bottlenecks and the working groups both identifying

important projects and providing the follow through

so that leaders feel their continued engagement is

productive.

9

landscape, bringing new value to higher education

and technical skills related to the management of new,

productivity-enhancing technologies. At the same time,

workers without those skills or education have seen their

opportunities diminish. Trade Adjustment Assistance has

played an important role in supporting workers who lost

their jobs due to increased import competition, but a much

larger, more comprehensive, and updated approach is

needed to address the simultaneous pressure put on many

workers from automation, robotics, and global competition.

Certainly, at its core, education and workforce development

is a domestic challenge for both the United States and

Mexico, but there are important ways in which, given

their economic integration, the two can also collaborate.

Tony Wayne and Sergio Alcocer have put forth a series of

recommendations for a regional workforce development

dialogue at the bilateral or trilateral level. They include the

following:

22

y Expand Apprenticeships and Other Types of Work-Based

Learning (WBL) and Technical Education, Including

Internships, Mentorships, and Mid-Career Learning

y Address Key Issues Surrounding Credentials, Including

Recognition and Portability, to Enhance Transparency

y Improve Labor Market Data Collection and Transparency,

Including Moving Towards Accepted Norms for

Employment, Education, and Skills-Related Data Collected

and for Making that Data Widely Available

y Identify Best Practices to Approach/Prepare for “The

Fourth Industrial Revolution,” the Transformative Arrival of

New Technologies and the Future of Work

We wholly endorse their recommendations and believe

workforce development to be a particularly timely addition

to the bilateral agenda for three reasons. First, the Andrés

Manuel López Obrador Administration has already made

the issue a priority, establishing a major youth internship

program, Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro (Youth Building

the Future). Adding a binational component supporting

young Mexicans and Americans taking internships across

the border would be a natural t and important way to build

an interculturally competent North American workforce.

Second, due to the decentralized nature of higher education

in especially the United States but also Mexico, workforce

development is a great topic for the type of state and local

engagement in bilateral relations that we recommend.

Finally, this topic puts the worker rst, contributing to a

more inclusive approach to bilateral economic relations. Of

course, it also improves regional competitiveness, but in a

way that stands in contrast to the perceptions of an elite-

focused approach to globalization and regional integration.

For a very similar set of reasons to those outlined above,

the United States and Mexico should focus on expanding

opportunities for binational research and educational

partnerships. In 2014, the U.S. and Mexico launched

FOBESI, the U.S.-Mexico Bilateral Forum on Higher

Education, Innovation and Research, which was designed

to complement and focus existing U.S. and Mexican

eorts to expand student and research exchange more

broadly.

23

Supporters of the initiative in government and

academic institutions found that short-term (a semester or

less) exchange programs had the most promise to attract

student and professor interest while also expanding the

opportunities to traditionally underserved populations.

Like workforce development, this item would benet from

22. Cite forthcoming chapter.

23. https://mx.usembassy.gov/education-culture/education/the-u-s-mexico-bilateral-forum-on-higher-education-innovation-and-research/

24. https://www.nga.org/news/press-releases/subnational-leaders-gather-at-2018-north-american-summit/

25. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/how-mexico-can-become-latin-americas-digital-government-powerhouse

its inclusion on the agenda for subnational forums for

cooperation like the Border Governors Conference and

North American Summit.

24

Technological advance is driving huge changes in the way

factories and oces around the world do business. Data

analysis is improving eciency in production and logistics;

articial intelligence systems (often hosted on the cloud)

are now the rst point of contact for many customer service

and IT departments; and meetings are at least as likely to

be virtual as they are in person. Digital transformation

is here today and will continue driving a restructuring of

work and the economy for years to come. Both the United

States and Mexico are well positioned to take advantage

of these trends, but both have major work to do to ensure

their workforces, infrastructure, and systems of governance

are ready for the economy of tomorrow. In particular,

Mexico lags behind other similarly developed nations in

the state of its digital economy.

25

The low proportion of its

population with a bank account, weak broadband access,

and unreliable post damper the growth of e-commerce and

sales of digital services. North America is otherwise primed

for major growth in regional e-commerce, so a concentrated

eort to improve these foundations of the digital economy in

Mexico could go a long way to create export opportunities

THE KEY ROLE OF STATE AND LOCAL

LEADERS

Increasingly, there are opportunities for governors,

mayors, and other subnational leaders to engage

counterparts across the border in ways that produce

tangible results for their constituencies. Over the

years, and with some ups and downs, organizations

like the Border Governors Conference, Border Mayors

Association, the U.S. National Governors Association,

and Mexico’s National Governors Conference (Conago)

have each participated in important cross-border

initiatives. They have worked to sustainably manage

water, reduce pollution, increase trade, coordinate

infrastructure development, and share best practices

on education and workforce development.

Because the United States and Mexico have federalist

systems of government, state and local leaders have

the power to impact key issues in bilateral relations. In

fact, though foreign relations are clearly the domain

of federal governments, state and local participation

is vital when it comes to things like building

interconnected road systems and growing student

exchange (and should be supported by the foreign

ministries). When managed successfully, state and

local leadership can even help tackle issues that are

too politically thorny for the federal governments, such

as immigration and water management.

The importance of local participation in bilateral

relations is especially apparent in border communities,

where everything from ghting res to economic

development has binational components, but mayors

from throughout both countries can nd value in

leading trade missions or developing university

partnerships across the border.

10

for small business. Focus is also needed on nancing opportunities for entrepreneurs in Mexico, which can in part be improved

by strengthening links between U.S.-based venture capital and Mexican startups.

Since NAFTA eliminated taris for most goods across North America, non-tari barriers, such as dierences in standards

and regulations ensuring product and food safety now act as some of the largest barriers to trade. Eorts to coordinate the

creation of compatible regulation across North America will improve regional competitiveness by allowing companies to

design and manufacture products for sale across the region. The United States has previously engaged both Canada (U.S.-

Canada Regulatory Cooperation Council) and Mexico (U.S.-Mexico High Level Regulatory Cooperation Council) on a bilateral

basis to harmonize regulation. These eorts should be revitalized and made trilateral. The eort should rst prioritize building

cooperation to write new rules before turning to the more dicult task of adjusting existing regulations to improve compatibility.

The Biden Administration has an ambitious plan to address climate change, and there are signicant opportunities for cross-

border collaboration in this area. The U.S.-Mexico Forum has a separate group that has developed a series of valuable

recommendations on issues of energy and sustainable development. Here we will just add that eorts on sustainable

development and energy must be fully integrated into the U.S.-Mexico economic dialogue. The U.S.-Mexico border region

should be prioritized and developed as an example for the world of what is possible in terms of international cooperation for

sustainable development. A council led by high level ocials from the economic and environmental agencies in both countries

should be formed with a mandate to create a comprehensive sustainable development strategy for the border region,

integrating approaches to water management, economic development, energy, and mobility.

Migration and drug policy are traditionally discussed by security ocials insofar as they form part of the bilateral agenda, yet

each has important economic dimensions, and the inclusion of economic ocials in the dialogue may open new areas for

cooperation. In the case of migration, the link is apparent, as the majority of migrants in the region are at least in part seeking

better work opportunities. U.S.-Mexico and North American cooperation to support economic development in Central America

could go a long way toward addressing the root causes of emigration from the Northern Triangle, and a regional dialogue

on the temporary movement of workers may open up spaces for the consideration of legislative action on the issue within

the United States. Marijuana has historically been bought and sold in the black market, outside of the purview of economic

regulators, but that dynamic is changing across North America. Canada has legalized recreational marijuana; Mexico is in the

process of doing so, and despite federal restrictions, several U.S. states have also created legal marijuana markets. While the

creation of a North American marijuana market will not be possible until U.S. federal law changes, there may be opportunities

to begin a dialogue to share best practices on regulatory frameworks and a future in which this market includes international

trade in the region.

Conclusion and Summary Recommendations

The United States and Mexico face an economic outlook that is at once challenging and promising. With the USMCA in

place and the COVID-19 vaccination rollout underway, two of the largest sources of uncertainty hovering over the regional

economy are clearing, oering hope that pent up consumption and investment may be on the horizon. Still, COVID-19 has

left a trail of destruction in its wake — businesses shuttered, evictions pending, and elevated levels of poverty. Political forces

in both countries make an inward, domestic-rst posture quite appealing right now, but to do so at the expense of regional

cooperation across North America would be a mistake. Only together can North America rise to the challenge of growing

international competition. Policies to address structural issues in each economy can and should be complementary to regional

economic collaboration. In so many ways, the United States and Mexico already share a regional economy, and in the wake of

crisis, they must work together to rebuild an even stronger, more inclusive and more competitive region.

Economy and Trade Group

Álvaro Santos Gordon Hanson

Christopher Wilson María Ariza

Sergio Alcocer Patricia Armendáriz

Juan Carlos Baker Renee Bowen

Earl Anthony Wayne Augusto Arellano

Enrique Dussel Viridiana Ríos

Beatriz Leycegui Santiago Salinas

Antonio Ortiz Mena Javier Treviño

This paper has been developed through a collaborative process and does not necessarily reect the views of any individual

participant or the institutions where they work.

Migration and drug policy are traditionally discussed by security ocials

insofar as they form part of the bilateral agenda, yet each has important

economic dimensions, and the inclusion of economic ocials in the dialogue

may open new areas for cooperation.

“

Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies

U.S.-MEXICO

FORUM 2025

USMEX.UCSD.EDU