2019

National Prole

of Local Health Departments

Public health is at the forefront of public attention and discourse worldwide in a way that is unparalleled in modern

times. COVID-19 brought the normally hidden work of public health into the limelight and has held it there with a

variety of fascinating results. “Epidemiologist” is now a common word, news outlets routinely discuss the merits of

population testing metrics, and for months, the nation tuned into briengs by the White House Coronavirus Task Force

headed byVice President Pence.

During the pandemic, data from the National Prole of Local Health Departments (Prole) studies have been in great

demand. The data have been highlighted by NACCHO and its national partners in communications to policymakers,

aswell as featured in newspapers, magazines, and newscasts all over the country.

Prole data are an incredible source of context for the current COVID-19 pandemic response. In fact, the Prole study

is the only longitudinal study of its kind focused on the infrastructure and practice of local health departments (LHDs).

As such, it highlights the impact of the continued underfunding of public health around the country. As health

departments tackle the largest pandemic in modern history, the workforce is strained, resources are redirected to

the response, essential services are disrupted, and leaders are faced with political pressures ranging from rings to

deaththreats.

In support of LHDs, NACCHO and its funding partners at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and

the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) remain committed to providing evidence regarding the state of local

public health that is objective, accurate, and useful. To reinforce these eorts, NACCHO is teaming with ZS Associates

and LiveStories to create interactive products that allow LHDs to access their data, compare it to state and regional

benchmarks, and combine it with health and healthcare metrics from other national datasets to create ready-made

reports on their local public health context.

Finally, I want to give special recognition to the NACCHO Prole Team that managed the daily work of the 2019 Prole

study in challenging conditions during the pandemic. They elded hundreds of emergency requests for data; worked

from home during the stay-at-home orders; endured endless Zoom calls with kids, partners, and pets in the background;

staed NACCHO’s Incident Command System in support of the federal response; and still delivered a quality product

ontime.

Aaron Alford

Senior Director, Research & Evaluation

Acknowledgments

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

2

NACCHO is pleased to present the 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments (Prole) to local health

departments (LHDs), policymakers, public health researchers, and the public health community. The Prole study

is the only one of its kind that collects data about LHD infrastructure and practice at the nationallevel.

LHDs are the backbone of the nation’s public health system as the “boots on the ground” for delivery of public health

services. Our rapidly changing world and crises like the COVID-19 pandemic emphasize the need for timely information

and data to support public health practice, especially at the local level. The Prole study provides accurate and useful

information about LHDs nationwide that are essential for making data-driven decisions and engaging in evidence-based

services. Such data are especially critical today, as we face national and global challenges that aect the health and

well-being of every community. In an era of unstable funding, LHDs increasingly depend upon reliable and useful data

to help them make dicult choices under sometimes less-than-ideal operating conditions. With data from the Prole

study, the public health community can prevent and combat disease and health inequities and make sound decisions

toimprove and enhance the physical and mental health of every individual.

The key to unleashing the power of data is action. Using data to drive decision-making is one of the best recommended

uses of this Prole. NACCHO looks forward to working with all of its diverse stakeholders in public health to continue

identifying new and interesting ways to use this powerful dataset to drive additional research, inuence important

policies, educate others on the importance of local governmental public health, and demonstrate the impact of public

health in communities across our country.

Jennifer Kertanis Lori Tremmel Freeman

President, NACCHO Chief Executive Ocer, NACCHO

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

3

Our nation’s experience with the COVID-19 pandemic

and previous public health emergencies has revealed

how critically important it is to collect inclusive

health data at the community level. NACCHO’s Prole

study provides the only comprehensive picture of

activities, workforce, funding, and priorities of local

health departments (LHDs) across the country.

These data are key for decision-makers seeking

evidence-based support to address the unique

needs of their specic communities. It’s my hope

this report will encourage policymakers to begin

collecting even more equity-focused data, with

the goal of supporting the infrastructure, funding,

stang, and programming of our nation’s LHDs in

ways that provide everyone in America a fair and just

opportunity for health andwell-being.

Richard E. Besser

President and CEO

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) is pleased to support NACCHO and its work

on the National Prole of Local Health Departments

(Prole) study. This 2019 Prole report is a valuable

resource for all public health professionals,

policymakers, federal agencies, researchers, and

others to use to understand our nation’s current local

public health infrastructure. The work of local health

departments is critical in protecting the health of

the community. I would like to commend NACCHO

and the local health departments who provided

these data, and their dedication and contribution

topublichealth.

Robert R. Redeld, MD

Director

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

4

National Prole of Local Health Departments Workgroup Members

Betty Bekemeier, PhD, MPH, MSN, FAAN

University of Washington

Bonnie Bruesho, RN, DNP, PHN

Dakota County Public Health Department

Maggie Carlin, MPH

Association of State and Territorial Health Ocials

Glenn Czarnecki, MPA

Tennessee Department of Health, Southeast Region

Jenine Harris, PhD

Washington University in St. Louis

Alannah Kittle, MPH

Association of State and Territorial Health Ocials

Ruth Maiorana

Maryland Association of County Health Ocers

Doug Mathis, MA

Henry County Health Department

NACCHO Prole Team

Aaron Alford, PhD, MPH, PMP

Senior Director of Research & Evaluation

Debra Dekker, PhD

Director of Evaluation

Karla Feeser, MPH

Senior Research Analyst

Kellie Hall, MSOD

Senior Research & Evaluation Specialist

Shaunna Newton, MPH

Senior Research & Evaluation Specialist

Carolyn Miller, MSHP, MA

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Carol Moehrle, RN, BSN

Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, North Central District

Jacquelynn Orr, DrPH, MHA

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Sergey Sotnikov, PhD

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Oktawia Wójcik, PhD

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Susan Zahner, DrPH, RN, FAAN

University of Wisconsin

Carlos Zometa, PhD

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(Those acknowledged served as a workgroup member during 2018, 2019,

or 2020.)

Jonathan P. Leider, PhD

Consultant

NACCHO would also like to acknowledge the following

people for their work on the 2019 Prole study:

Nathalie Robin, MPH

Previous Senior Research Analyst

Kari O’Donnell, MA

Previous Research & Evaluation Specialist

Johnnetta Davis-Joyce, MA

Previous Senior Director of Research & Evaluation

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

5

Contents

CHAPTER 1

Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 11

CHAPTER 2

Jurisdiction and Governance .......................................................................................... 20

CHAPTER 3

Partnerships ........................................................................................................................... 28

CHAPTER 4

Leadership .............................................................................................................................. 39

CHAPTER 5

Workforce ................................................................................................................................ 47

CHAPTER 6

Finance .................................................................................................................................... 64

CHAPTER 7

Programs and Services ...................................................................................................... 75

CHAPTER 8

Emergency Preparedness andResponse ................................................................... 97

CHAPTER 9

Assessment, Planning, andAccreditation ................................................................106

CHAPTER 10

Quality Improvement andWorkforce Development ...........................................118

CHAPTER 11

Public Health Policy ..........................................................................................................127

CHAPTER 12

Informatics............................................................................................................................137

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

6

Figures

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 | Questionnaire topics, by questionnaire type and response rate .............................................................................................................. 14

1.2 | Number of LHDs in study population and number of respondents, by state ............................................................................................. 15

1.3 | Number of LHDs in study population and number of respondents, by size of population served .................................................................. 16

Chapter 2

Jurisdiction and Governance

2.1 | Size of population served by LHDs in the study population ................................................................................................................... 21

2.2 | Percent of United States population served by LHDs ............................................................................................................................ 22

2.3 | Geographic jurisdictions served by LHDs, by size of population served .................................................................................................... 23

2.4 | Type of LHD governance, by state ..................................................................................................................................................... 24

2.5 | LHDs as a part of a combined Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA), by state ................................................................................... 25

2.6 | LHDs with a local board of health (LBOH), by size of population served and type of governance ................................................................... 26

2.7 | Functions that local boards of health (LBOHs) utilize on a continuous basis .............................................................................................. 27

Chapter 3

Partnerships

3.1 | Cross-jurisdictional sharing of services, by size of population served and type of governance ...................................................................... 29

3.2 | Type of cross-jurisdictional sharing of services .................................................................................................................................... 30

3.3 | LHD partnerships and collaborations in the past year ........................................................................................................................... 31

3.4 | Formal* LHD partnerships and collaborations, over time ....................................................................................................................... 32

3.5 | Direction of information exchange between LHDs and partner organizations in the past year ...................................................................... 33

3.6 | Engagement with academic institutions in the past year, by size of population served................................................................................ 34

3.7 | Engagement with academic institutions in the past year, by degree of urbanization ................................................................................... 35

3.8 | Engagement with specic academic institutions in the past year ............................................................................................................ 36

3.9 | Number of research studies in which LHDs participated during the past year, by size of population served and degree of urbanization ............... 37

3.10 | Participation in research activities during the past year, by size of population served ................................................................................ 38

Chapter 4

Leadership

4.1 | Characteristics of LHD top executives ................................................................................................................................................ 40

4.2 | Age of LHD top executives, over time ................................................................................................................................................ 41

4.3 | Tenure of LHD top executives, over time ............................................................................................................................................ 42

4.4 | Average tenure (in years) of LHD top executives, over time and by size of population served ....................................................................... 43

4.5 | Highest degree obtained by LHD top executive, by size of population served and degree of urbanization ...................................................... 44

4.6 | Specialized degrees obtained by LHD top executive, by size of population served and degree of urbanization ................................................ 45

4.7 | Characteristics of new versus experienced LHD top executives ............................................................................................................... 46

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

7

Figures

Chapter 5

Workforce

5.1 | Number of Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs) ............................................................................................................................................. 48

5.2 | Mean and median number of employees and Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs), by size of population served ........................................................ 49

5.3 | Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs) per 10,000 people, by size of population served ............................................................................................ 50

5.4 | Estimated size of the LHD workforce ................................................................................................................................................. 51

5.5 | Distribution of Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs), by degree of urbanization .................................................................................................... 52

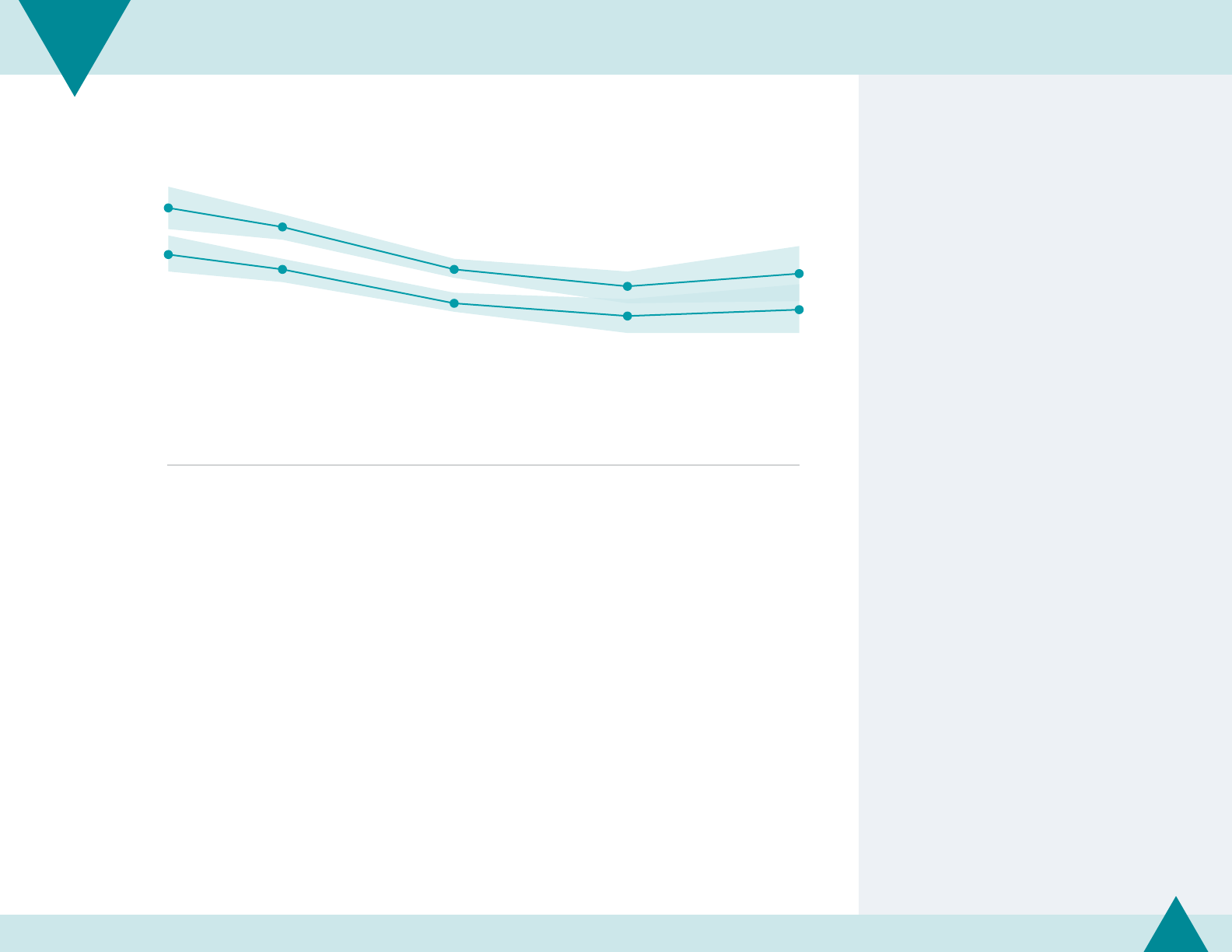

5.6 | Estimated size of LHD workforce, over time ........................................................................................................................................ 53

5.7 | Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs) per 10,000 people, over time and by size of population served ......................................................................... 54

5.8 | LHD workforce that retired, over time ................................................................................................................................................ 55

5.9 | Occupations employed at LHDs, by size of population served ................................................................................................................ 56

5.10 | Stang patterns (in median Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs)) at LHDs, by size of population served ................................................................. 57

5.11 | Estimated number of Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs) in select occupations ................................................................................................. 58

5.12 | Workforce composition ................................................................................................................................................................. 59

5.13 | Estimated size of select occupations, over time.................................................................................................................................. 60

5.14 | Job losses among LHDs due to layos and/or attrition in the past year, by size of population served andtype of governance .......................... 61

5.15 | Job losses among LHDs due to layos and/or attrition, over time .......................................................................................................... 62

5.16 | Number of jobs lost and added, over time and by size of population served............................................................................................ 63

Chapter 6

Finance

6.1 | Total annual expenditures ............................................................................................................................................................... 65

6.2 | Mean and quartiles of total annual expenditures ................................................................................................................................. 66

6.3 | Median and quartiles of annual per capita expenditures and revenues, by size of population served and type of governance ............................ 67

6.4 | Overall median annual expenditures per capita, by state ....................................................................................................................... 68

6.5 | Median and mean annual per capita expenditures, over time................................................................................................................. 69

6.6 | Revenue sources ........................................................................................................................................................................... 70

6.7 | Median and mean annual per capita revenue sources, by LHD characteristics ........................................................................................... 71

6.8 | Median and mean annual per capita revenue sources, over time ............................................................................................................ 72

6.9 | Changes in LHD budgets, over time .................................................................................................................................................. 73

6.10 | Percent of LHD’s budget cut in the current scal year compared to the previous scal year ........................................................................ 74

Chapter 7

Programs and Services

7.1 | Clinical programs and services provided directly by LHDs in the past year ................................................................................................ 76

7.2 | Population-based programs and services provided directly by LHDs in the past year .................................................................................. 77

7.3 | Adult and child immunization services provided directly by LHDs in the past year, by size of population served and degree of urbanization ........ 78

7.4 | Screening and treatment for diseases and conditions provided directly by LHDs in the past year,

by size of population served and degree of urbanization ...................................................................................................................... 79

7.5 | Maternal and child health services provided directly by LHDs in the past year, by size of population served and degree of urbanization .............. 80

7.6 | Other clinical services provided directly by LHDs in the past year, by size of population served and degree of urbanization ............................... 81

7.7 | Epidemiology and surveillance services provided directly by LHDs in the past year, by size of population served and degree of urbanization ....... 82

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

8

Figures

7.8 | Population-based primary prevention services provided directly by LHDs in the past year, by size of population served and degree of urbanization ....... 83

7.9 | Regulation, inspection, or licensing services provided directly by LHDs in the past year, by size of population served and degree of urbanization ...... 84

7.10 | Environmental health services provided directly by LHDs in the past year, by size of population served and degree of urbanization .................. 85

7.11 | Other population-based services provided directly by LHDs in the past year, by size of population served and degree of urbanization .............. 86

7.12 | Number of services contracted out by LHDs, by size of population served .............................................................................................. 87

7.13 | Programs and services provided most frequently via contracts ............................................................................................................. 88

7.14 | Provision of population-based primary prevention services by other organizations independent of LHD funding .......................................... 89

7.15 | Programs and services more likely to be provided in rural jurisdictions .................................................................................................. 90

7.16 | Programs and services more likely to be provided in urban jurisdictions................................................................................................. 91

7.17 | Change in percent of LHDs providing clinical programs and services since 2008 ...................................................................................... 92

7.18 | Change in percent of LHDs providing population-based programs and services since 2008 ....................................................................... 93

7.19 | Changes in provision of services in the past year ................................................................................................................................ 94

7.20 | Growing, stable, and shrinking services in the past year ...................................................................................................................... 95

7.21 | Changes in provision of services, by changes in budgets in the past year ................................................................................................ 96

Chapter 8

Emergency Preparedness andResponse

8.1 | Changes in LHD budgets for emergency preparedness activities, by size of population served and census region ........................................... 98

8.2 | Funding sources for emergency preparedness activities ....................................................................................................................... 99

8.3 | Response to specic all-hazards events in the past year, over time .........................................................................................................100

8.4 | Response to specic all-hazards events in the past year, by size of population served ................................................................................101

8.5 | Response to specic all-hazards events in the past year, by census region ...............................................................................................102

8.6 | Number of LHD responses to specic all-hazards events in the past year .................................................................................................103

8.7 | Use of select volunteer groups in emergency preparedness activities .....................................................................................................104

8.8 | Use of select volunteer groups in emergency preparedness activities, over time ....................................................................................... 105

Chapter 9

Assessment, Planning, andAccreditation

9.1 | Participation over time in a community health assessment (CHA), community health improvement plan (CHIP),

and/or strategic plan (SP) within ve years ........................................................................................................................................107

9.2 | Participation in a community health assessment (CHA), community health improvement plan (CHIP), and/or strategic plan (SP)

within ve years, by size of population served .................................................................................................................................... 108

9.3 | Data included in most recent community health assessment (CHA), over time .........................................................................................109

9.4 | Use of tools for most recent community health improvement plan (CHIP) ...............................................................................................110

9.5 | Actions taken in the past three years to implement or sustain a community health improvement plan (CHIP), over time .................................. 111

9.6 | Level of collaboration with non-prot hospitals on most recent community health needs assessment(CHNA) ...............................................112

9.7 | Types of collaboration with non-prot hospitals on most recent community health needs assessment(CHNA) ..............................................113

9.8 | Level of engagement with Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) accreditation in 2019 ........................................................................114

9.9 | Level of engagement with Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) accreditation, over time ....................................................................115

9.10 | Formal engagement in Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) accreditation, over time and by size ofpopulation served ........................... 116

9.11 | Reasons for not pursuing Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) accreditation ................................................................................... 117

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

9

Figures

Chapter 10

Quality Improvement andWorkforce Development

10.1 | Level of quality improvement (QI) implementation, over time .............................................................................................................119

10.2 | Level of quality improvement (QI) implementation, by size of population served ....................................................................................120

10.3 | Number of quality improvement (QI) projects implemented in the past year .......................................................................................... 121

10.4 | Number of quality improvement (QI) projects implemented in the past year, by level of QI implementation ................................................122

10.5 | Elements of an agency-wide quality improvement (QI) program currently in place at LHD, over time .......................................................... 123

10.6 | Use of any competency sets for workforce development, planning, and action ....................................................................................... 124

10.7 | Use of the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals .............................................................................................................125

10.8 | Use of the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals, over time ............................................................................................... 126

Chapter 11

Public Health Policy

11.1 | Involvement in policy areas in the past two years, by size of population served ......................................................................................128

11.2 | Involvement in select policy areas, over time....................................................................................................................................129

11.3 | Involvement in policy areas related to tobacco, alcohol, opioids, or other drugs in the past two years, bysize of population served..................130

11.4 | Involvement in policy areas related to tobacco, alcohol, opioids, or other drugs in the past two years, bydegree of urbanization .....................131

11.5 | Involvement in policy areas related to tobacco, alcohol, or other drugs, over time ...................................................................................132

11.6 | Involvement in developing new or revising existing ordinances in the past two years, byLHDcharacteristics...............................................133

11.7 | Topic areas of new or revised ordinances in the past two years ............................................................................................................134

11.8 | Engagement in assuring access to healthcare services in the past year .................................................................................................. 135

11.9 | Engagement in assuring access to healthcare services, over time ......................................................................................................... 136

Chapter 12

Informatics

12.1 | Level of activity in information technology systems ...........................................................................................................................138

12.2 | Implementation of information technology systems, by size of population served ..................................................................................139

12.3 | Implementation of information technology systems, over time ...........................................................................................................140

12.4 | Organizations involved in information management for LHDs .............................................................................................................141

12.5 | Use of communication channels for general or emergency response communications ............................................................................142

12.6 | Any use of communication channels, by size of population served ....................................................................................................... 143

12.7 | Any use of communication channels, by type of governance ..............................................................................................................144

12.8 | Any use of communication channels, by degree of urbanization ..........................................................................................................145

12.9 | Any use of communication channels, over time ................................................................................................................................146

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

10

This chapter includes the following:

Study background and methods.

Questionnaire topics.

Number of local health departments (LHDs)

instudy population.

Denitions of LHD jurisdiction size, type of

governance, census regions, and urbanization.

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

The National Association of County and City Health Ocials (NACCHO) conducted the rst National Prole of Local

Health Departments (Prole) study from 1989 to 1990. This study helped to dene a local health department (LHD) and

describe how funding, stang, governance, and activities of LHDs vary across the United States. In the three decades

since, NACCHO has conducted an additional eight Prole studies, including in 2019. All Prole studies have been funded

by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); beginning in 2007, NACCHO has also received funding from

the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF).

Purpose

The purpose of the Prole study is to develop a comprehensive and accurate description of LHD infrastructure and

practice. Data from the Prole study are used by many people and organizations across the United States. For example,

LHD sta use the data to compare their LHD to others within their state or the nation; data are used to inform public

health policy at the local, state, and federal levels and can support projects to improve local public health practice; and

data are used in universities to educate the future public health workforce about LHDs and by researchers to address

questions about public health practice. NACCHO sta use Prole data to develop programs and resources that meet

the needs of LHDs and to advocate eectively for LHDs. NACCHO also generates Geographic Information System (GIS)

shapeles and denitions of Prole study LHD jurisdictions that support visual description and denition of LHDs for

researchers and policymakers.

Study Methodology

Study population

Every Prole study uses the same denition of an LHD: an administrative or service unit of local or state government,

concerned with health, and carrying some responsibility for the health of a jurisdiction smaller than the state. There

are approximately 2,800 agencies or units that meet the Prole denition of an LHD. Some states have a public health

system structure that includes both regional and local oces of the state health agency. In those states, the state health

agency chooses to respond to the Prole survey at either the regional or local level, but not at both levels.

NACCHO uses a database of LHDs based on previous Prole studies and consults with state health agencies and State

Associations of Local Health Ocials (SACCHOs) to identify LHDs for inclusion in the study population. For the 2019

Prole study, a total of 2,459 LHDs were included in the study population. Rhode Island was excluded from the study

because the state health agency operates on behalf of local public health and has no sub-state units. For the rst time,

Hawaii wasincluded.

Introduction

CHAPTER

1

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

12

Sampling

All LHDs in the study population received a common set of questions, called the the Core questionnaire. A randomly

selected group of LHDs also received one of the two sets of supplemental questions (or modules). LHDs were selected

to receive the Core questionnaire only or the Core plus one of the two modules using stratied random sampling

(without replacement), with strata dened by the size of the population served by the LHD. The module sampling

process is designed to produce national estimates but not to produce state-level estimates.

Questionnaire development

The NACCHO Prole team developed both the Core and module questionnaires by rst reviewing the 2016 Prole

questionnaires to determine how each question performed among respondents and what questions should be kept,

modied, or deferred to a future Prole questionnaire. The team also reviewed questionnaires from previous years (e.g.,

2013, 2010, 2008, 2005) to identify whether any questions should be repeated in 2019. Lastly, the team developed

new questions based on current public health topics. An advisory group—comprising LHD leaders, sta from aliate

organizations, and researchers—and other subject matter experts within NACCHO provided input and feedback on new

and revised survey questions. Many questions in the Core and module questionnaires have been used in previous Prole

studies and provide an ongoing dataset for comparative analysis; most new items were placed in modules. The Prole

team piloted the questionnaire from December 2018 to January 2019 among 28 LHDs (13 completed it for a response

rate of 46%). NACCHO interviewed select LHDs to assess whether certain sections and questions performed as expected.

The Prole team revised the survey as needed and nalized it for distribution.

Questionnaire distribution

In January 2019, NACCHO sent an e-mail announcement to all 2,459 LHDs in the study population. In the e-mail,

LHDs were given the opportunity to designate another sta person as the primary contact to complete the Prole

questionnaire. NACCHO launched the nal questionnaire from March to August 2019 via an e-mail sent to the

designated primary contacts. The e-mail included a link to a web-based questionnaire, individualized with preloaded

identifying information specic to the LHD. LHDs could print a hard copy version of their Prole questionnaire by using

alink in the questionnaire introduction or could request that NACCHO sta send a copy via e-mail orU.S. mail.

The Prole team conducted extensive eorts to encourage participants to complete the questionnaire. Before and

during the administration period, NACCHO disseminated promotional materials about the survey via NACCHO’s print

and electronic publications (i.e., Public Health Dispatch, NACCHO Connect, NACCHO Voice) and social media channels.

NACCHO sta and a nationwide group of Prole study advocates conducted follow-up with non-respondents using

e-mail messages and telephone calls. NACCHO also oered technical support to survey respondents through an e-mail

address and telephone hotline. The nal response rate for the 2019 Prole study was 61%.

Introduction

CHAPTER

1

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

13

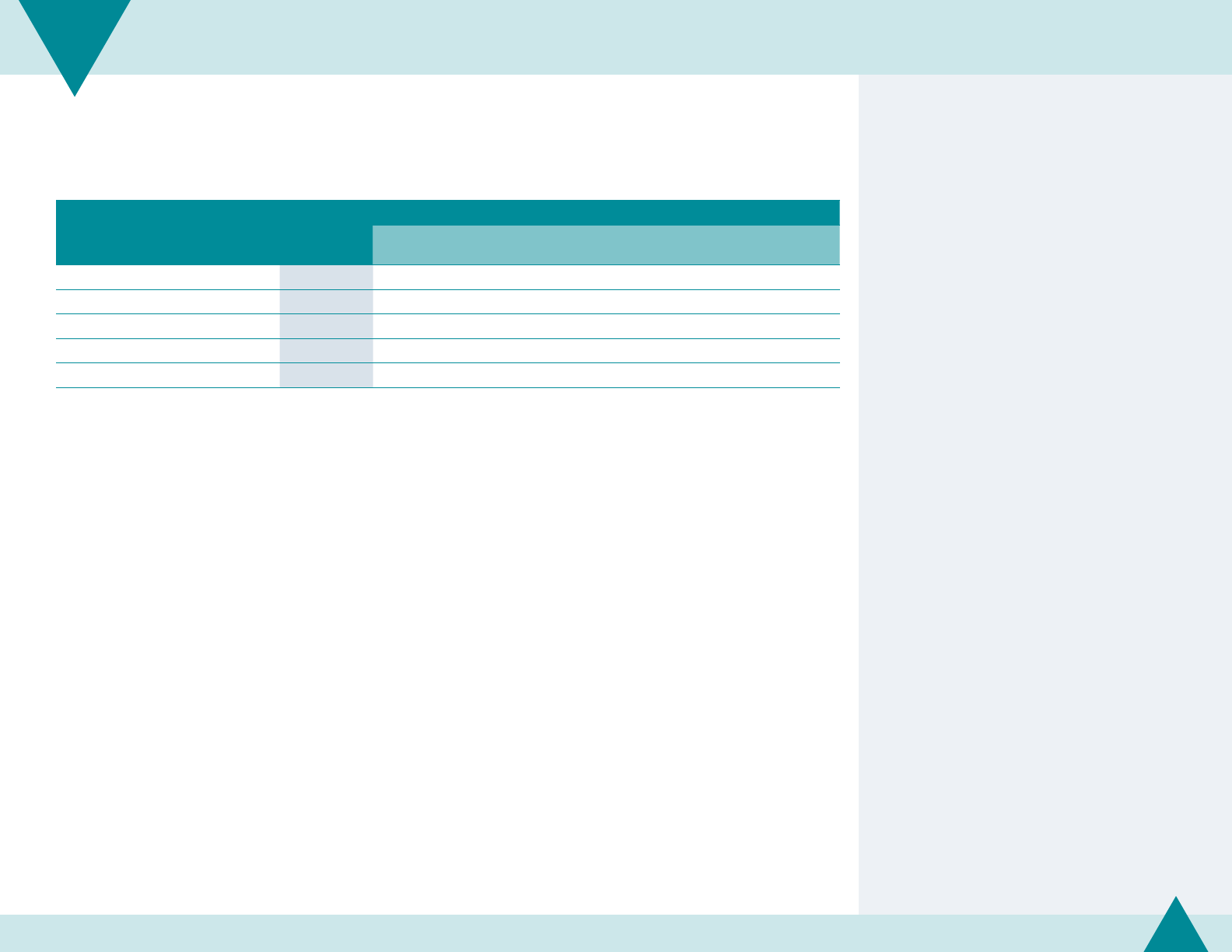

Figure 1.1 | Questionnaire topics, by questionnaire type and response rate

The 2019 Prole study questionnaire

included a set of questions (Core

questionnaire) sent to all LHDs in the

United States; additional supplemental

questions were grouped into

twomodules.

LHDs were randomly assigned to receive

only the Core questionnaire or the Core

plus one of the two modules.

Many questions in the Core and module

questionnaires have been used in previous

Prole studies and provide an ongoing

dataset for comparative analysis; most new

items were placed in modules.

Core Module 1 Module 2

(Core only response rate = 59%) (Core + Module 1 response rate = 61%) (Core + Module 2 response rate = 65%)

LHD top executive LHD interaction with academic institutions Jurisdiction and governance

Jurisdiction and governance Partnerships and collaboration

Community health assessment

andplanning

Workforce Cross-jurisdictional sharing of services Human resources issues

Stang changes Emergency preparedness Quality improvement

Programs and services Access to healthcare services Public health informatics

Public health policy Guide to Community Preventive Services

Community health assessment

andplanning

Evaluation of Prole

Accreditation

Funding

Changes in LHD budget

Introduction

CHAPTER

1

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

14

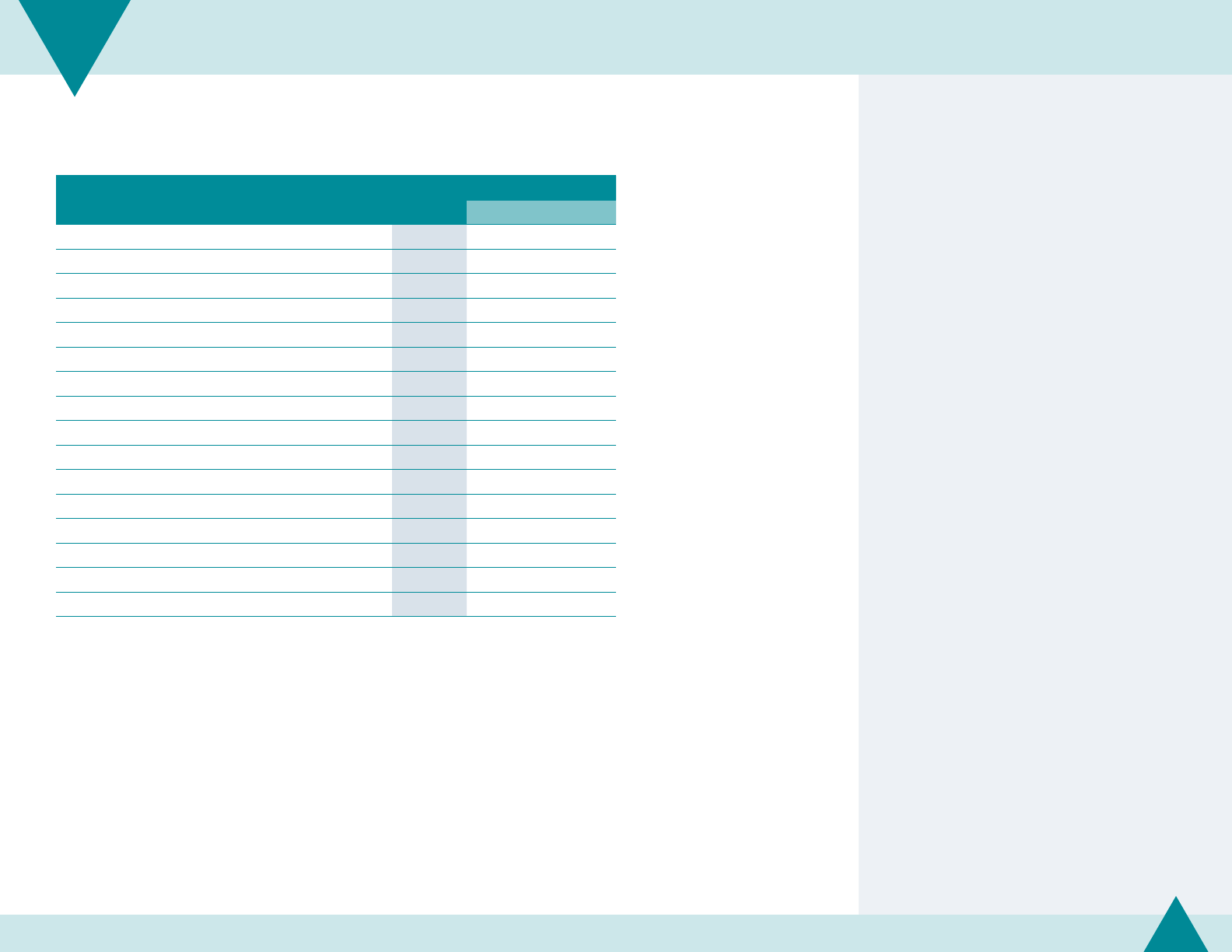

Figure 1.2 | Number of LHDs in study population and number of respondents, by state

Overall, 1,496 LHDs responded to the 2019

Prole study for a response rate of 61%.

Most states had a response rate of 50% or

more, with the exception of Connecticut,

Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Mississippi,

Missouri, Montana, New Mexico,

Oklahoma, and West Virginia.

Alabama, the District of Columbia, Idaho,

Nevada, South Carolina, and Vermont had

response rates of 100%.

State

Total number

of LHDs

Number of

respondents Response rate

All 2,459 1,496 61%

Alabama 66 66 100%

Alaska 2 1 50%

Arizona 15 10 67%

Arkansas 75 71 95%

California 61 34 56%

Colorado 53 27 51%

Connecticut 67 32 48%

Delaware 2 1 50%

District of Columbia 1 1 100%

Florida 67 65 97%

Georgia 18 9 50%

Hawaii 3 2 67%

Idaho 7 7 100%

Illinois 93 76 82%

Indiana 93 34 37%

Iowa 98 44 45%

Kansas 100 52 52%

Kentucky 60 42 70%

Louisiana 10 7 70%

Maine 10 9 90%

Maryland 24 23 96%

Massachusetts 293 110 38%

Michigan 44 28 64%

Minnesota 74 55 74%

Mississippi 3 1 33%

State

Total number

of LHDs

Number of

respondents Response rate

Missouri 114 55 48%

Montana 51 12 24%

Nebraska 19 14 74%

Nevada 3 3 100%

New Hampshire 2 1 50%

New Jersey 92 54 59%

New Mexico 5 2 40%

New York 58 37 64%

North Carolina 85 59 69%

North Dakota 28 27 96%

Ohio 113 61 54%

Oklahoma 70 30 43%

Oregon 33 25 76%

Pennsylvania 16 9 56%

South Carolina 4 4 100%

South Dakota 8 7 88%

Tennessee 95 92 97%

Texas 72 36 50%

Utah 13 7 54%

Vermont 12 12 100%

Virginia 35 20 57%

Washington 35 25 71%

West Virginia 48 22 46%

Wisconsin 86 61 71%

Wyoming 23 14 61%

Introduction

CHAPTER

1

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

15

Figure 1.3 | Number of LHDs in study population and number of respondents, by size of population served

LHDs serving smaller populations had

lower response rates than did those

serving larger populations.

Because there are relatively few LHDs

serving large populations, the higher

response rates among LHDs serving larger

populations are important for ensuring

that ndings are representative for LHDs in

this category and to the analytic capacity

of the study data.

Size of population served

Total number

of LHDs

Number of

respondents

Response

rate

All 2,459 1,496 61%

<25,000 979 523 53%

25,000–49,999 510 313 61%

50,000–99,999 385 253 66%

100,000–249,999 293 203 69%

250,000–499,999 142 96 68%

500,000–999,999 100 72 72%

1,000,000+ 50 36 72%

Introduction

CHAPTER

1

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

16

Survey Weights and National Estimates

Unless otherwise stated, national statistics presented were computed using survey weights. NACCHO developed survey

weights for the items from the Core questionnaire to account for dierential non-response by size of population served;

survey weights used to produce statistics from modules also accounted for sampling. By using survey weights, the

Prole study provides national estimates for all LHDs in the United States. Beginning in 2019, we used post-stratication

(based on year and population size) and nite population correction; the condence intervals associated with some

statistics may dier from items published in previous years due to this change.

Longitudinal comparisons for workforce were constructed using NACCHO Prole data from 2008 through 2019. The

2008–2016 workforce estimates reported in 2019 dier from those estimates reported in previous years due to two

factors. First, a small number of LHDs were removed from the analysis over the past years to enhance comparability

through 2019. In 2020, NACCHO created a multi-year dataset to analyze trends for various reasons, including in response

to the COVID-19 crisis. As part of the process, NACCHO conducted an enhanced data review which revealed a very small

number of LHDs with ongoing reporting errors. Though few in number, these LHDs reported more employees and Full-

Time Equivalents (FTEs) than the average respondent in their population size category, thus marginally impacted the

national estimates. Second, 95% condence intervals were generated across all years using nite population correction

and post stratication, based on categories of population size served. This handles non-response adjustment by

population size and accounts for the fact that population size by category is known and limited in size.

Introduction

CHAPTER

1

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

17

Subgroup Analysis

Throughout this report, data are analyzed by various LHD jurisdiction characteristics, namely size of population served,

type of governance, United States census regions, and degree of urbanization.

Size of population served

Statistics are compared across LHDs serving jurisdictions of dierent population sizes. LHDs are classied as small if

they serve fewer than 50,000 people, medium if they serve between 50,000 and 500,000 people, and large if they serve

500,000 or more people. For certain statistics that are highly dependent on size of population served (e.g., nance and

workforce statistics), a larger number of population subgroups are used.

Type of governance

Statistics are compared across LHDs’ relationship to their state health department. Some LHDs are agencies of local

government (referred to as locally governed). Others are local or regional units of the state health department (referred

to as state-governed). Some are governed by both state and local authorities (called shared governance). Refer to

Chapter 2 (Jurisdiction and Governance) for more details.

United States census region

Statistics are also compared across United States census regions. All LHDs in each state are classied as being in the

North, South, Midwest, or West, per the U.S. Census Bureau (http://www.census.gov/econ/census/help/geography/

regions_and_divisions.html).

Degree of urbanization

Statistics are compared across LHD jurisdiction degree of urbanization. Each LHD in the Prole study population was

classied as serving either an urban or rural jurisdiction. This classication system used the National Center for Health

Statistics (NCHS) Urban-Rural Classication Scheme denitions (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.

htm) and the Economic Research Service (ERS) Frontier and Remote Area Codes (https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-

products/frontier-and-remote-area-codes/). Each LHD was coded as urban or rural based on whether the majority of

people it served were from urban or rural settings (calculated for each census tract the LHD serves). This classication

system is new to the 2019 Prole. The estimates associated with some statistics may dier from items published in

previous years due to this change.

Introduction

CHAPTER

1

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

18

Study Limitations

The Prole study is a unique and comprehensive source of information on LHD nances, infrastructure, workforce,

activities, and other important characteristics. However, several limitations should be considered when using the results

of this study. Given the large scope of this study, the level of detail available does not provide extensive information

on all dimensions of the topics addressed. For example, the Prole provides information about whether or not an LHD

provides a specic program or service but does not provide any information about the scope or scale of that program or

service. All data are self-reported by LHD sta and are not independently veried. LHDs may have provided incomplete,

imperfect, or inconsistent information for various reasons.

While the Prole questionnaire includes denitions for many items, not every item or term is dened. For example, the

questionnaire does not include denitions for each of the 67 programs and services included in the Prole questionnaire.

Consequently, respondents may have interpreted questions and items dierently.

Responding to the Prole questionnaire is time-intensive; consequently, respondents may have skipped some questions

because of time restrictions. In addition, responses to some questions may have been based on estimation to reduce

burden. In particular, questions on nance were dicult for LHDs to answer and yielded large amounts of missing data.

Refer to Chapter 6 (Finance) for more details.

Comparisons with data from prior Prole studies are provided for some statistics, but these comparisons should be

viewed with caution because both the study population and the respondents are dierent for each Prole study. In

addition, comparisons are not tested for statistical signicance.

Introduction

CHAPTER

1

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

19

This chapter includes the following:

Population sizes served by local health

departments (LHDs).

Geographic jurisdictions served by LHDs.

Governance of LHDs.

Combined Health and Human

ServicesAgencies.

Local boards of health.

Jurisdiction and Governance

CHAPTER 2

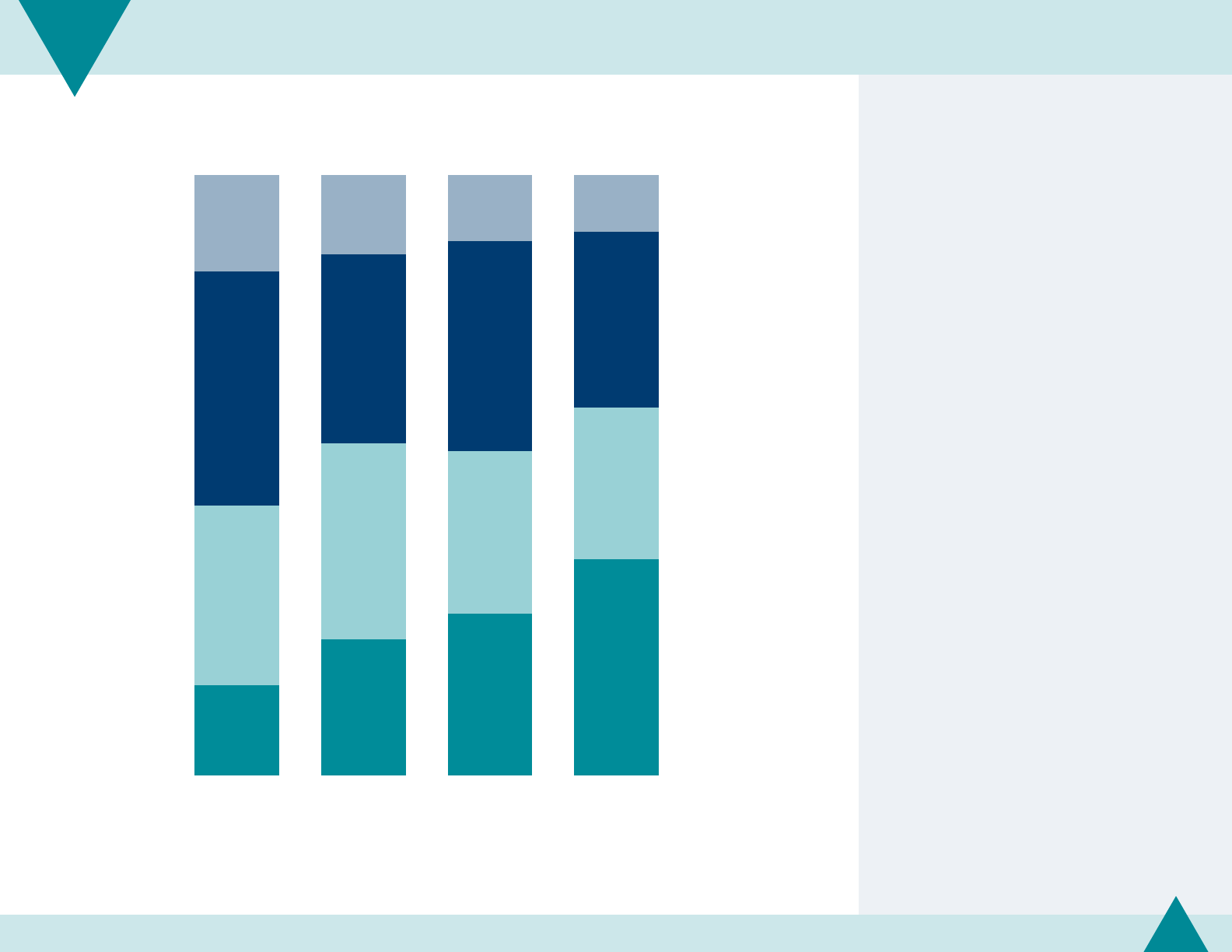

Figure 2.1 | Size of population served by LHDs in the study population

There are approximately 2,800 LHDs in

the United States, but not every unit

is included in the Prole study. LHDs

operating under a centralized government

structure may include multiple levels (e.g.,

county units and multi-county regions or

districts). The state health agency selects

one level for inclusion in the Prole.

2,459 LHDs were included in the 2019

Prole study population.

LHDs serve dierent sized jurisdictions

across the U.S. Of the 2,459 LHDs included

in the 2019 Prole study population, 61%

serve fewer than 50,000people.

Size of population served N Percent

<10,000 404 16%

10,000–24,999 575 23%

25,000–49,999 510 21%

50,000–74,999 248 10%

75,000–99,999 136 6%

100,000–199,999 238 10%

200,000–499,999 198 8%

500,000–999,999 100 4%

1,000,000+ 50 2%

Total 2,459

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

21

CHAPTER

2 Jurisdiction and Governance

Technical note

The total population served by all LHDs included in the

study represents 98% of the total U.S. population.

61%

9%

Small (<50,000)

33%

37%

Medium (50,000–499,999)

6%

52%

Large (500,000+)

Percent of all LHDs Percent of population served by LHDs

N=2,459

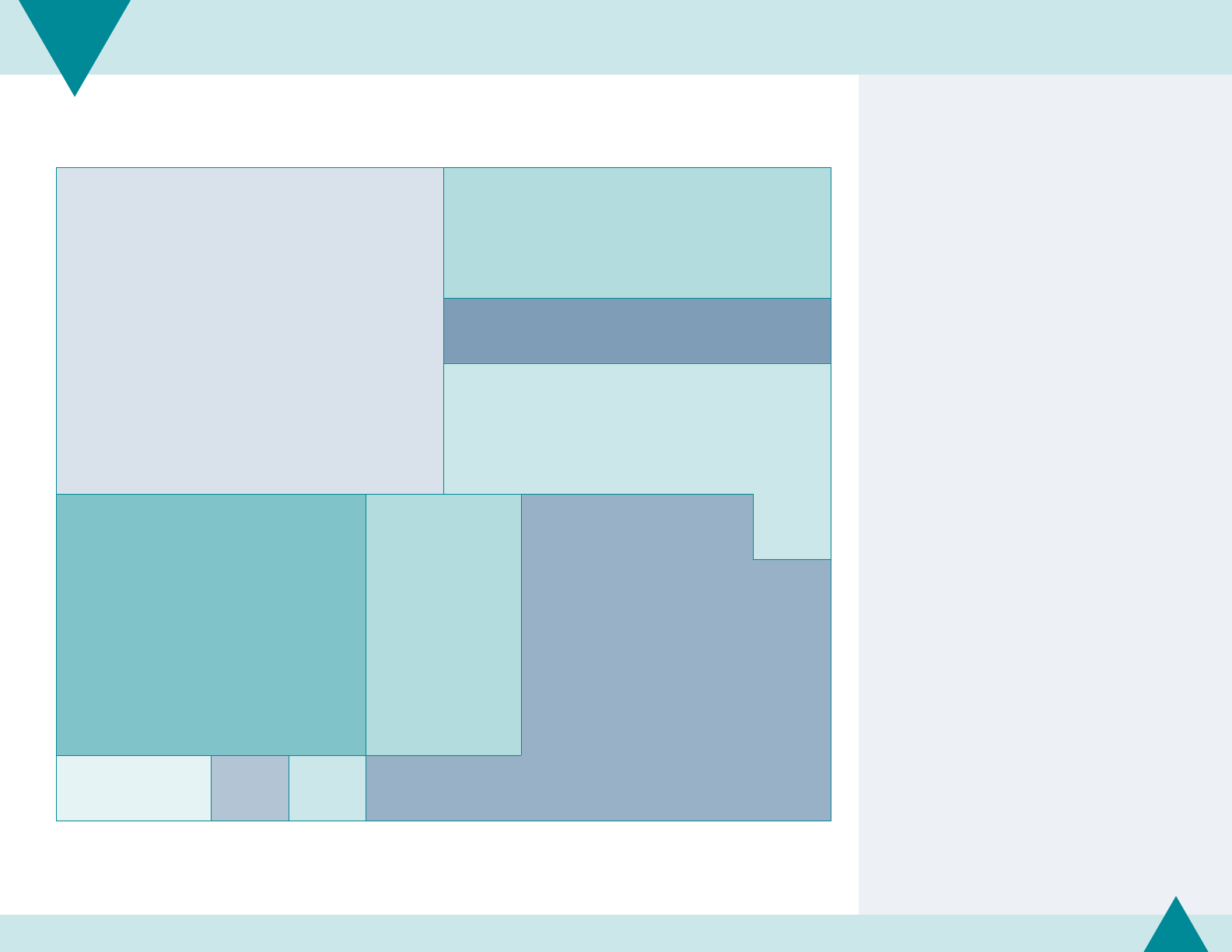

Figure 2.2 | Percent of United States population served by LHDs

Throughout this report, small LHDs are

classied as those that serve populations

of fewer than 50,000 people; medium

LHDs serve populations of between 50,000

and 500,000 people; and large LHDs serve

populations of 500,000 or more people.

Although only 6% of all LHDs are classied

as large, they serve about half of the U.S.

population.

The majority of LHDs are small, but

together, they serve less than 10% of the

U.S. population.

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

22

CHAPTER

2 Jurisdiction and Governance

*County includes city-counties

**Other includes LHDs serving multiple cities or towns

N=2,459

70%

71%

67%

70%

19%

24%

11%

6%

8%

3%

14%

23%

3%

2%

7%

1%

All LHDs

Small (<50,000)

Medium (50,000–499,999)

Large (500,000+)

County*

City or town

Multi-

county Other**

Percent of LHDs

Size of population served

Figure 2.3 | Geographic jurisdictions served by LHDs, by size of population served

Approximately two-thirds of LHDs are

county-based, and an additional 8% serve

multiple counties. One-fth of LHDs serve

cities or towns.

Large LHDs are less likely to serve cities or

towns but are more likely to serve multiple

counties than small LHDs.

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

23

CHAPTER

2 Jurisdiction and Governance

RI was excluded from the study

N=2,459

LA

ID

AZ

UT

MT

WY

NM

CO

AL

FL

SC

TN

KY

IN

OH

NC

SD

KS

NE

MN

WI

IA

IL

MO

AR

MS

OK

ND

OR

CA

NV

WA

TX

MI

GA

AK

HI

PA

ME

VA

NY

CT

WV

VT

NH

MA

DE

DC

RI

MD

NJ

Figure 2.4 | Type of LHD governance, by state

Of the 2,459 LHDs included in the 2019

Prole study population, 1,886 are locally

governed, 405 are units of the state health

agency, and 168 have shared governance.

In 30 states, all LHDs are locally

governed. These states are referred

toasdecentralized.

All LHDs in Florida, Georgia, and Kentucky

have shared governance.

All LHDs in Arkansas, Delaware, Hawaii,

Mississippi, New Mexico, and South

Carolina are units of the state health

agency. These states are referred to

ascentralized.

n Local (all LHDs in state are units of local government)

n State (all LHDs in state are units of state government)

n Shared (all LHDs in state governed by both state and local authorities)

n Mixed (LHDs in state have more than one governance type)

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

24

CHAPTER

2 Jurisdiction and Governance

RI was excluded from the study

n=1,479

LA

ID

AZ

UT

MT

WY

NM

CO

AL

FL

SC

TN

KY

IN

OH

NC

SD

KS

NE

MN

WI

IA

IL

MO

AR

MS

OK

ND

OR

CA

NV

WA

TX

MI

GA

AK

HI

PA

ME

VA

NY

CT

WV

VT

NH

DE

DC

RI

MD

MA

NJ

MD

MA

Figure 2.5 | LHDs as a part of a combined Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA), by state

One in ve LHDs are currently part of a

combined Health and Human Services

Agency (HHSA).

More than half of LHDs in six states are

part of a combined HHSA; at least one-

third of LHDs in eight states are a part of a

combined HHSA; and fewer than one-third

of LHDs in the remaining states are a part

of a combined HHSA.

Combined Health and Human Services

Agency(HHSA)

A combined health and human services agency can be

dened as an agency that administers all programs dealing

with health and welfare. A combined health and human

services agency provides a broad range of health and social

services to promote wellness, self-suciency, and a better

quality of life by integrating health and social services

through a unied service-delivery system.

n More than 50% of LHDs

n 33%–50% of LHDs

n Less than 33% of LHDs

n DC, ID, MS, and UT had insucient data

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

25

CHAPTER

2 Jurisdiction and Governance

20% 50% 30%

All LHDs

20% 51% 29%

Small (<50,000)

21% 50% 30%Medium (50,000–499,999)

19% 38% 43%

Large (500,000+)

33% 9% 58%

State

18% 63% 19%

Local

11% 41% 48%

Shared

Advisory

Governing No LBOH

Size of population served

Percent of LHDs with a local board of health

Type of governance

n=1,469

Figure 2.6 | LHDs with a local board of health (LBOH), by size of population served and type of governance

Seventy percent of LHDs have a local

board of health (LBOH).

A larger proportion of small LHDs have

LBOHs compared to large LHDs.

Locally governed LHDs are more likely

to have a LBOH compared to LHDs

that are state-governed or with shared

governance.

A higher proportion of LHDs have LBOHs

with a governing role compared to an

advisory role. However, state-governed

LHDs are more likely to have an advisory

LBOH than a governing body.

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

26

CHAPTER

2 Jurisdiction and Governance

*Among LHDs with a LBOH

n=1,016

75%

Oversight

66% Policy development

61% Legal authority

49% Continuous improvement

47% Resource stewardship

47% Partner engagement

8% None of the above

Percent of LHDs* with LBOH utilizing function

Figure 2.7 | Functions that local boards of health (LBOHs) utilize on a continuous basis

The National Association for Local Boards

of Health (NALBOH) identies six functions

of public health governance.

Most LHDs have LBOHs that provide

oversight, while fewer have LBOHs that

provide resource stewardship and partner

engagementfunctions.

Local board of health functions

Oversight is to assume ultimate responsibility for public health performance

in the community by providing necessary leadership and guidance in order

to support the public health agency in achieving measurable outcomes,

such as by hiring or ring the agency head.

Policy development is to lead and contribute to the development of policies

that protect, promote, and improve public health while ensuring that the

agency and its components remain consistent with the laws and rules to

which it issubject.

Legal authority is to exercise legal authority as applicable by law and

understand the roles, responsibilities, obligations, and functions of the

governing body, health ocer, and agency sta, such as by adopting public

health regulations and imposing or enforcing quarantine or isolation orders.

Continuous improvement is to routinely evaluate, monitor, and set

measurable outcomes for improving community health status and the public

health agency’s/governing body’s own ability to meet itsresponsibilities.

Resource stewardship is to assure the availability of adequate resources to

perform essential public health services, such as by approving the LHD budget,

setting and imposing fees, imposing taxes for public health, or requesting a

public health levy.

Partner engagement is to build and strengthen community partnerships

through education and engagement to ensure the collaboration of all

relevant stakeholders in promoting and protecting the community’s health.

Refer to the 2015 Local Board of Health Prole for additional data on

these functions (available at www.naccho.org/resources/lhd-research/

national-prole-of-local-boards-of-health).

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

27

CHAPTER

2 Jurisdiction and Governance

This chapter includes the following:

Cross-jurisdictional sharing of services.

Local health department (LHD) partnerships

and collaborations.

LHD engagement with academic institutions.

Partnerships

CHAPTER 3

More than half of LHDs share resources

(such as funding, sta, or equipment) with

other LHDs on a continuous, recurring,

non-emergency basis, regardless of size.

A larger proportion of LHDs with shared

governance share resources than locally

governed LHDs.

n=369

Size of population served

Type of governance

All LHDs

55%

Small (<50,000)

56%

Medium (50,000–499,999)

54%

Large (500,000+)

54%

State

59%

Local

52%

Shared

69%

Percent of LHDs sharing services or resources with other LHD(s)

Figure 3.1 | Cross-jurisdictional sharing of services, by size of population served and type of governance

Cross-jurisdictional sharing ofservices

Cross-jurisdictional sharing of services is a phrase used

to refer to the various means by which jurisdictions work

together to provide public health services. LHDs across the

country are looking to cross-jurisdictional sharing as a way

to help them more eciently and eectively deliver public

health services. The information provided in this section

reects sharing resources on a continuous, recurring, non-

emergency basis.

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

29

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships

n=359–363

38% LHD provides functions/services for another LHD

35% LHD receives functions/services from another LHD

33% LHD shares a sta member with another LHD

29% Another LHD shares a sta member with LHD

24% LHD shares equipment with another LHD

21% Another LHD shares equipment with LHD

Percent of LHDs sharing resource/service with other LHD(s)

Figure 3.2 | Type of cross-jurisdictional sharing of services

More than one-third of LHDs receive

functions or services from another LHD

or provide functions or services for

anotherLHD.

LHDs are more likely to share resources

with another LHD than they are to receive

them. For example, one-third of LHDs

share sta members with another LHD,

while 29% have another LHD share a sta

member with them.

Cross-jurisdictional sharing ofservices

Cross-jurisdictional sharing of services is a term used to

refer to the various means by which jurisdictions work

together to provide public health services. LHDs across the

country are looking to cross-jurisdictional sharing as a way

to help them more eciently and eectively deliver public

health services. The information provided in this section

reects sharing resources on a continuous, recurring, non-

emergency basis.

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

30

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships

n=183–366

Percent of LHDs working with organization in any way

Percent of LHDs regularly scheduling meetings, have written agreements, or share personnel/resources with organization

84% 47%

84% 41%

78%

78%

39%

35%

77% 31%

71% 29%

35% 18%

Government partners

Criminal justice system

Local planning

Parks and recreation

Economic and community development

Housing

Transportation

Tribal government

97% 77%

94% 74%

93% 46%

92% 62%

57% 89%

74% 22%

72% 39%

Healthcare partners

Emergency responders

Hospitals

Physician practices/medical groups

Community health centers

Mental health/substance abuse providers

Veterinarians

Health insurers

25%

98%

71%

96% 21%

92% 72%

88% 62%

87% 44%

87% 48%

82% 45%

74%

Community-based partners (e.g., education, non-government)

K–12 schools

Media

Community-based non-prots

Faith communities

Colleges or universities

Businesses

Cooperative extensions

Libraries

Figure 3.3 | LHD partnerships and collaborations in the past year

LHDs work with a variety of partners in

their communities in a variety of ways,

such as sharing information, regularly

scheduling meetings, establishing

written agreements, and sharing

personnel/resources.

More than 95% of LHDs work with

some partners, including emergency

responders, K-12 schools, and the media.

Collaborations with other partners

are less universal, including tribal

governments, transportation agencies,

andhealthinsurers.

Overall, LHDs are less likely to collaborate

in ways beyond exchanging information

(i.e., regularly scheduling meetings,

establishing written agreements,

or sharing personnel/resources).

This dierence is particularly large

for the media (only 21% collaborate

beyond information exchange while

96% exchange information) and

veterinarians (only 26% collaborate

beyond information exchange while

74%exchangeinformation).

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

31

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships

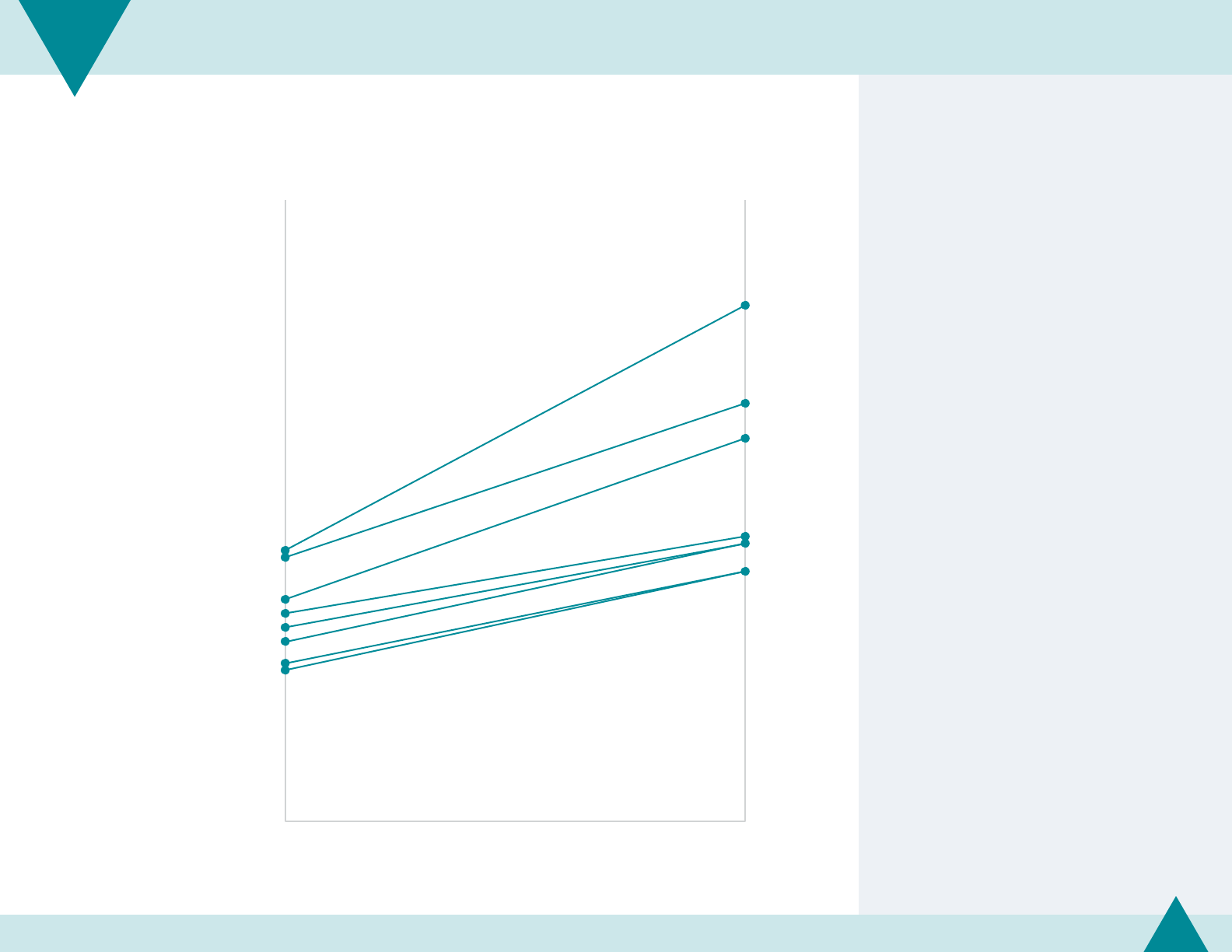

Figure 3.4 | Formal* LHD partnerships and collaborations, over time Percent of LHDs that *share personnel/resources and/or have written agreements

Healthcare partners Government partners

K–12 schools

Colleges or

universities

Community-based

non-prots

Cooperative

extensions

Faith communities

Businesses

Media

Libraries

59%

38%

49%

45%

30%

53%

34%

18%

39%

28%

10%

23%

19%

8%

19%

18%

7%

26%

13%

12%

11%

5%

16%

Community-based partners

2016 20192008

Local planning

Criminal

justice system

Parks and

recreation

Economic and

community

development

Transportation

Housing

Tribal

government

26%

10%

18%

19%

14%

25%

11%

7%

15%

9%

12%

17% 17%

2016 20192008

Emergency

responders

Hospitals

Physician

practices/

medical groups

Community

health centers

Health insurers

Mental health/

substance abuse

providers

Veterinarians

61%

39%

44%

57%

35%

2016 20192008

47%

38%

30%

26%

42%

24%

23%

32%

19%

14%

19%

34%

21%

n=414–447 n=218–483 n=183–366

Although the proportion of LHDs reporting formal

collaborations with many organization types decreased

between 2013 and 2016, it increased between 2016

and2019.

Despite these increases, the proportion of LHDs reporting

formal collaborations with many organization types

has not recovered to 2013 results. In particular, formal

partnerships with emergency responders, hospitals,

andK-12 schools saw the greatest overall declines.

Conversely, LHDs were more likely to report formal

partnerships with health insurers, colleges or universities,

and businesses in 2019, compared to 2013.

LHDs are generally less likely to have formal partnerships

with government partners than with either healthcare or

other community-based partners.

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

32

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships

n=183–365

44%

39%

38%

36%

36%

27%

21%

36%

42%

25%

39%

33%

24%

12%

Government partners

Local planning

Criminal justice system

Parks and recreation

Economic and community development

Housing

Transportation

Tribal government

79%

58%

51%

45%

43%

37%

35%

34%

26%

57%

43%

31%

23%

35%

19%

37%

Community-based partners

Media

K–12 schools

Community-based non-prots

Businesses

Faith communities

Colleges or universities

Libraries

Cooperative extensions

Percent of LHDs sending data Percent of LHDs receiving data

63%

57%

50%

48%

46%

39%

35%

48%

49%

44%

44%

34%

34%

Healthcare partners

Physician practices/medical groups

Hospitals

Mental health/substance abuse providers

Emergency responders

Community health centers

Veterinarians

Health insurers

60%

Figure 3.5 | Direction of information exchange between LHDs and partner organizations in the past year

With most partners, a greater proportion

of LHDs sent data than received data when

sharing information in the past year. In

particular, LHDs were three times as likely

to send data to media partners than to

receive data.

In the past year, more than half of LHDs

shared data (sent and received) with

hospitals and K-12 schools.

Few LHDs shared data (sent or received)

with transportation agencies and

tribalgovernments.

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

33

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships

Figure 3.6 | Engagement with academic institutions in the past year, by size of population served

All LHDs

Size of population served

Small

(<50,000)

Medium

(50,000–

499,999)

Large

(500,000+)

LHD accepts students from academic institutions as trainees, interns, or volunteers 76% 66% 91% 93%

LHD actively recruits graduates from academic institutions 31% 17% 50% 67%

LHD sta serve on an academic institution advisory group 28% 16% 42% 67%

LHD sta serve as faculty in academic institutions 23% 8% 40% 76%

Faculty/sta from academic institutions have served in a consulting role for LHD 23% 10% 39% 58%

Academic instruction collaborates with LHDs on research studies 22% 11% 33% 67%

LHD contracts with academic institution to provide public healthservices 11% 8% 14% 22%

LHD has formal relationship with academic institutions to provide training or

professional development for LHD sta

11% 5% 16% 35%

Academic institutions have agreements or policies on providing LHD with access

toscientic and professional journals

8% 3% 15% 25%

None of the above 21% 30% 6% 4%

Some LHDs engage and partner with

academic institutions. Three-quarters

accept students from academic

institutions (as trainees, interns, or

volunteers) but fewer actively recruit

graduates frominstitutions.

Fewer than one-third of LHDs have sta

that serve on an academic institution

advisory group or as faculty.

Medium and large LHDs are more likely

to engage in partnership activities with

academic institutions than small LHDs.

Notably, almost all larger LHDs accept

students from academic intuitions.

In 2019, LHDs were less likely to have

a formal relationship with academic

institutions to provide training or

professional development for LHD sta

than in 2016 (25%, not shown).

n=373

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

34

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships

Technical note

A new schema for categorizing urban and rural LHDs was

used for 2019 estimates. These data may not be comparable

to previous year estimates. Refer to page 18 for more

information on the methodology.

Figure 3.7 | Engagement with academic institutions in the past year, by degree of urbanization

LHDs in urban areas are more likely to

engage with academic institutions. For

example, 41% actively recruit graduates

from academic institutions, compared to

only 20% of LHDs in rural areas. Similarly,

35% of urban LHD sta serve on faculty in

academic institutions, compared to only

11% of rural LHD sta.

All LHDs

Degree of urbanization

Urban Rural

LHD accepts students from academic institutions as trainees, interns, or volunteers 76% 80% 72%

LHD actively recruits graduates from academic institutions 31% 41% 20%

LHD sta serve on an academic institution advisory group 28% 37% 18%

LHD sta serve as faculty in academic institutions 23% 35% 11%

Faculty/sta from academic institutions have served in a consulting role for LHD 23% 33% 12%

Academic instruction collaborates with LHDs on research studies 22% 29% 14%

LHD contracts with academic institution to provide public health services 11% 14% 8%

LHD has formal relationship with academic institutions to provide training or professional development

forLHD sta

11% 14% 7%

Academic institutions have agreements or policies on providing LHD with access to scientic and

professional journals

8% 12% 4%

None of the above 21% 15% 26%

n=373

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

35

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships

*In schools or programs other than nursing or public health

n=311

83% Schools of nursing

74%

Four-year colleges

or universities*

67%

Accredited schools or

programs of public health

45% Community colleges (two-year)*

Figure 3.8 | Engagement with specic academic institutions in the past year

LHDs are more likely to be engaged with

Schools of Nursing than other kinds of

academic institutions.

Two-thirds of LHDs partner or interact

with accredited schools or programs of

publichealth.

Less than half of LHDs engaged with two-

year community colleges in the past year.

Percent of LHDs engaging with academic institution

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

36

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships

1%

Size of population served

24% 75%Small (<50,000)

44% 6% 50%Medium (50,000–499,999)

51% 32% 17%Large (500,000+)

Degree of urbanization

38% 6% 56%Urban

26% 3% 71%Rural

Percent of LHDs participating in research studies

32% 5% 63%All LHDs

4 or more

studies1 to 3 studies No studies

n=303

Figure 3.9 | Number of research studies in which LHDs participated during the past year, by size of population served

and degree of urbanization

One in three LHDs reported participating

in at least one research study during the

past year.

Large LHDs were more likely to participate

in research studies than small and medium

LHDs. In particular, one-third of large LHDs

participated in more than three studies

during the pastyear.

LHDs in urban areas participate in a greater

number of research studies than those in

rural areas.

Technical note

A new schema for categorizing urban and rural LHDs was

used for 2019 estimates. These data may not be comparable

to previous year estimates. Refer to page 18 for more

information on the methodology.

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

37

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships

n=324

Figure 3.10 | Participation in research activities during the past year, by size of population served

More than half of LHDs did not participate

in research activities during the past

year. The most common research activity

LHDs did participate in was collecting,

exchanging, or reporting data for a study.

Large LHDs were more likely to report

participating in research activities than

small LHDs. For example, 56% of large

LHDs applied research ndings to

practices within their own organization,

compared to only 7% of small LHDs.

All LHDs

Size of population served

Small

(<50,000)

Medium

(50,000–

499,999)

Large

(500,000+)

Collecting, exchanging, or reporting data for a study 29% 19% 39% 64%

Disseminating research ndings to key stakeholders 18% 9% 30% 50%

Applying research ndings to practices within own organization 17% 7% 29% 56%

Analyzing and interpreting study data and ndings 17% 10% 24% 58%

Identifying research topics and questions that are relevant to public health practice 15% 8% 21% 50%

Recruiting study sites and/or study participants 11% 6% 13% 52%

Helping other organizations apply research ndings to practice 11% 6% 14% 39%

Developing or rening research plans and/or protocols for public health studies 9% 3% 13% 35%

None of the above 62% 74% 47% 16%

NACCHO | 2019 National Prole of Local Health Departments

38

CHAPTER

3 Partnerships