7KH&RQVWUXFWLRQRI-D]]5DSDV+LJK$UWLQ+LS+RS0XVLF

$XWKRUV-XVWLQ$:LOOLDPV

6RXUFH

7KH-RXUQDORI0XVLFRORJ\

9RO1R)DOOSS

3XEOLVKHGE\University of California Press

6WDEOH85/http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2010.27.4.435 .

$FFHVVHG

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Musicology.

http://www.jstor.org

The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 27, Issue 4, pp. 435–459, ISSN 0277-92 69, electronic ISSN 1533-8347.

© 2010 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests

for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of California Press’s

Rights and Permissions website, http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintInfo.asp. DOI: 10.1525/

jm.2010.27.4.435.

435

I am grateful for the helpful comments and suggestions on this

material by a number of individuals, including Jane Brandon,

Carlo Cenciarelli, Mervyn Cooke, Dan Grimley, Tim Hughes,

Mark Katz, Adam Krims, Katherine Williams, and numerous

anonymous reviewers. I owe special thanks to the British Library

and Dawn-Elissa Fischer and Marcyliena Morgan at the Stanford

Hiphop Archive (now at Harvard University) for access to media

materials crucial to this article. Additional support was provided

through a research grant from the Economic and Social Research

Council, UK (Ref. PTA-026-27-2307).

1

Christopher John Farley, “Hip-Hop Goes Bebop,” Time, July 12, 1993, available at:

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,978844,00.html (accessed August

17, 2007).

2

Quoted in Danyel Smith, “Gang Starr: Jazzy Situation,” Vibe, May 1994, 88.

The Construction of

Jazz Rap as High Art

in Hip-Hop Music

J USTIN A. WILLIAMS

For doubters, perhaps rap + jazz will = acceptance.

1

—Christopher John Farley,

in Time, July 12, 1993

“T

he so-called jazz hip hop movement

is about bringing jazz back to the streets. It got taken away, made

into some elite, sophisticated music. It’s bringing jazz back where it

belongs.”

2

The late rapper Guru made this statement in a 1994 inter-

view for Vibe magazine, at a time when the “jazz rap” subgenre had be-

come a widely discussed phenomenon in media discourse. Simultane-

ously, the owering of eclectic rap groups and subgenres in the hip-hop

mainstream—a period some writers refer to as the “golden age” of the

JM2704_02.indd 435 11/22/10 5:06:09 PM

the journal of musicology

436

genre (1986–93)—was coming to an end.

3

During this era, multiple

subgenres aunted a wide variety of lyrical content, imagery, and eclec-

tic musical styles, digitally sampled and borrowed.

4

This essay focuses on a particular moment in hip-hop music history,

roughly 1989–93, which saw the construction of jazz rap as an alternative

to other rap subgenres such as “gangsta” and “pop rap.” Most impor-

tantly, the status of jazz as a sophisticated art form in the mainstream

culture industries in 1980s America played an important role in the cul-

tural reception of jazz rap. Despite Guru’s desire to bring jazz “back to

the streets,” the ideological damage had been done, so to speak—jazz

aesthetics and imagery contributed to highbrow distinctions within the

hip-hop music world.

Functionally speaking, the construction of jazz rap represented the

creation of a unique type of high art within the rap music world, the term

“high art” being understood specically as a distinction within the hip-

hop domain and not with respect to cultural discourse more generally.

When discussing rap music or hip-hop as an art form, writers position

certain groups or genres at the top of an authenticity hierarchy, as op-

posed to the lower “mass culture” of other rap subgenres. Although art-

ists, reviewers, and other commentators may not use the terms “high art”

or “mass culture” in the context of rap music, the meaning and purpose

of this distinction, which has been used for at least a century in American

culture, remain consistent with other cultural realms, past and present.

5

3

Considered by historians to begin in the mid- to late-1980s and ending in 1993,

this “golden age” began with Run-D.M.C.’s rise to popularity and ended with what Jeff

Chang calls “the big crossover” in Dr. Dre’s The Chronic. In this era, a diversity of artists

and groups such as N.W.A., Ice Cube, Public Enemy, and 2 Live Crew coexisted in the rap

mainstream with Jungle Brothers, KRS-One, De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, women

such as MC Lyte and Queen Latifah, and pop-rap artists MC Hammer and Vanilla Ice.

Writers and critics lament the loss of this “golden age” in light of the post-1992 hegemony

of gangsta rap in the mainstream. See Jeff Chang, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the

Hip-hop Generation (London: Ebury, 2005), 420; and William Jelani Cobb, To the Break of

Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip-hop Aesthetic (New York: New York University Press, 2008), 47.

4

A distinction is to be drawn between musical borrowing in general and (digital)

sampling, which amounts to a special case of musical borrowing. By the late-1980s or

early 90s, sampling had become cheaper and more efcient: many producers switched

from the E-Mu SP-1200 to Akai MPC samplers, which were more exible and allowed for

more complex sampling techniques. For more detail on this shift, see Classic Material: The

Hip-Hop Album Guide, ed. Oliver Wang (Toronto: ECW Press, 2003), 32; see also Joseph

G. Schloss, Making Beats: The Art of Sample-based Hip-hop (Middleton: Wesleyan University

Press, 2004), 34–35; and Felicia M. Miyakawa, Five Percenter Rap: God Hop’s Music, Message,

and Black Muslim Mission (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005), 107. For a thor-

ough explanation and discussion of digital sampling, see Mark Katz, Capturing Sound: How

Technology has Changed Music (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), in particular,

chap. 7, “Music in 1s and 0s: The Art and Politics of Digital Sampling,” 137–57; see also

Joanna Demers, “Sampling the 1970s in Hip-hop,” Popular Music 22, no. 3 (2003): 41–56.

5

Lawrence W. Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in Amer-

ica (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988).

JM2704_02.indd 436 11/22/10 5:06:09 PM

WILLIAMS

437

Although attempts to place artists and groups within subgenres are

inherently problematic, genre systems are nonetheless useful: “simply

reference points,”

6

as Krims suggests, a “blunt instrument” that is a

“necessary step in grasping representation in rap.”

7

As stereotypes or

“ideal types,” the genres in question are constructed and used by the

music industry, fans, and the media as structural interpretative frame-

works. Examining contemporary music journalism is a particularly use-

ful method by which to gauge this type of reception. Yet surprisingly,

journalism (especially on hip-hop) has received less attention than it

should in popular-music studies, for arguably it is reception, rather than

composer intentionality or a musicologist’s individual interpretation,

that proves crucial to the productive discussion of digital sampling and

other forms of borrowing in hip-hop and other musical cultures.

With regard to the term “jazz rap”: I use it here for the sake of

simplicity, since numerous classications (e.g., hip-bop or jazz hip-

hop) were given to artists and groups at the time. Jazz codes—sounds,

lyrical references, and imagery that were identied as jazz—facilitated

the establishment of this subgenre and became a focal point for writ-

ers and fans. Although groups belonging to the hip-hop “golden age”

sampled from a number of styles, jazz was a cultural product familiar

to the popular consciousness of various audiences in 1980s America.

Furthermore, ideological associations with jazz helped to shape iden-

tities for those who sampled and borrowed from jazz styles, and they

informed a hierarchy within hip-hop largely based on art-versus-com-

merce rhetoric.

Jazz and the 1980s

Mainstream jazz in the 1980s United States centered not so much on

new developments as on the revival of older styles; and what seemed to

dominate the public jazz discourse in this era was the notion that jazz was

serious art music. The 1980s witnessed a widespread expansion in the

cultural mainstream of what I call a “jazz art ideology,” many characteris-

tics of which developed during the bebop era of the 1940s and 50s; and

they were revived in part because of successful “neoclassical” conservative

jazz musicians like Wynton Marsalis.

8

By then, jazz had moved to concert

halls, academic institutions, and to within close proximity of the classical

6

Krims, Rap Music, 92.

7

Ibid., 55.

8

“Neoclassical” conservative jazz is a term used by Gary Giddins in his introduction,

“Jazz Turns Neoclassical,” Rhythm-a-ning: Jazz Tradition and Innovation in the ’80s (New

York: Oxford University Press, 1985), xi–xv. The idea of jazz as an elite art form was ad-

mittedly supported by a selected number of critics and writers well before the bebop era,

particularly in France, and often centering on the work of Duke Ellington.

JM2704_02.indd 437 11/22/10 5:06:10 PM

the journal of musicology

438

section of music stores. Jazz became a symbol for many things: America,

democracy, African American culture, and most important to this study,

highbrow art music.

9

Stylistically, the jazz revived in the 1980s became

what Stuart Nicholson calls “the hard-bop mainstream,”

10

and its pro-

motion by a number of younger musicians helped usher the music into

membership in the cultural aristocracy.

The 1980s jazz renaissance occurred in a number of ways, including

not only the touring of jazz artists and reissuing of jazz classics, but also

the aggressive marketing of a younger generation of jazz musicians. Films

like Bird (1988) and Round Midnight (1986) showed tormented genius

musicians, and Spike Lee’s Mo’ Better Blues (1990)

11

romanticized the jazz

world and put jazz in the cultural consciousness of the hip-hop genera-

tion.

12

As for print media, dozens of jazz books and autobiographies were

published and reissued to create and accommodate demand during this

jazz resurgence.

13

The Cosby Show, the most successful American sitcom of

the 1980s, presented an upper-middle-class black family, used jazz musi-

cians as guests (including Tito Puente, Dizzy Gillespie, the Count Basie

Band, Jimmy Heath, Art Blakey, and Max Roach) and featured jazz-based

scoring as music cues between scenes.

14

Although the show had been crit-

icized for avoiding issues of race explicitly, it reinforced jazz’s association

with the black middle class by suggesting a highbrow sophistication to be

set off against lower-class African American representations in popular

culture, notably the “hood” lms of the early 1990s.

15

9

Robert Walser noted that “by the 1980s, jazz had risen so far up the ladder of cul-

tural prestige that many people forgot it had ever been controversial.” He cited a 1987

resolution by the U.S. Congress that declared jazz had “evolved into a multifaceted art

form” and that the youth of America need “to recognize and understand jazz as a signi-

cant part of their cultural and intellectual heritage.” (Keeping Time: Readings in Jazz History,

ed. Robert Walser [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999], 332–33).

10

For a more complete description, see Stuart Nicholson, Jazz: The 1980s Resurgence

(New York: Da Capo Press, 1995), vi.

11

A popular single from the soundtrack of Mo’ Better Blues was “Jazz Thing” by the

hip-hop group Gang Starr (MC Guru and DJ Premier). The song tells a selective history

of jazz, uses a number of jazz samples from across jazz’s history, and includes characteris-

tic turntable scratching styles from DJ Premier. The single and accompanying music video

uses stock footage from older jazz performances, such as those from Duke Ellington and

Charlie Parker. “Jazz Thing” brought the group national attention, though Gang Starr as

a group subsequently tried to distance themselves from any jazz-rap categorization.

12

Other jazz lms of the 1980s worth mentioning are the Chet Baker documen-

tary Let’s Get Lost (1989), dir. Bruce Weber, and the Thelonious Monk biopic Straight, No

Chaser (1989), dir. Clint Eastwood. Additionally, a number of jazz musicians were writing

lm scores at the time (e.g., Terence Blanchard, Mark Isham, Lennie Niehaus).

13

Christopher Harlos, “Jazz Autobiography: Theory, Practice, Politics,” in Represent-

ing Jazz, ed. Krin Gabbard (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995), 132–33.

14

The show ran from 1984 to 1992 and was the number 1 show in America for ve

consecutive years.

15

These lms include Boyz n the Hood (1991), dir. John Singleton, South Central

(1992), dir. Steve Anderson, Juice (1992), dir. Ernest R. Dickerson, and Menace II Society

JM2704_02.indd 438 11/22/10 5:06:10 PM

WILLIAMS

439

Television commercials were also associating jazz with afuence.

Chase Manhattan Bank, American Express, the Nissan Inniti luxury

car, and Diet Coke all used jazz in their television advertising.

16

In 1988,

Yves Saint Laurent designed their fragrance “JAZZ For Men,” which

ran ads in Rolling Stone magazine and elsewhere.

17

Another advertise-

ment in a 1991 Rolling Stone featured British jazz saxophonist Courtney

Pine modeling GAP turtleneck sweaters.

18

Partially inspired by Wynton

Marsalis’s taste for ne suits (and that of the other young musicians

who followed his lead), marketers connected jazz with high fashion.

The clean-cut images portrayed by these jazz musicians suggested a cul-

tural elite, a higher-class ethos sharply contrasted to the working-class

images of many rock and heavy metal performers.

There was a further institutionalization of jazz in education: middle

schools and high schools added jazz bands to their lists of ensembles,

universities offered classes and degrees in jazz, and parameters of the

music were codied for the purposes of teaching improvisation.

19

As

Grover Sales commented in his aptly titled Jazz: America’s Classical Music

(rst published in 1984), “Monk, Mingus, Dolphy and the Miles Davis

Sextet with Coltrane and Evans will fuel musicians of the future, just as

Bach and Haydn prepare conservatory graduates.”

20

Wynton Marsalis, more than any other individual, played a key role

in the mass-scale legitimization of jazz in the 1980s. A trumpet player

and composer from New Orleans, he was the rst recording artist to

hold a record contract in jazz and classical music simultaneously (at

age nineteen, with Columbia Records), and the rst artist to win Gram-

mys in jazz and classical in the same year (1983; he repeated the feat

in 1984). He cofounded Jazz at Lincoln Center in 1987, rmly placing

(1993), dir. Albert and Allen Hughes. Juxtapositions of the black middle class and a

lower class were not new. For example, this distinction was made during the Harlem Re-

naissance in the 1920s. For more on the black middle class, see William Julius Wilson, The

Declining Signicance of Race (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978); Mary Patillo,

Black Picket Fences (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997); and Karyn Lacy, Blue-Chip

Black (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

16

See Krin Gabbard, intro. “The Jazz Canon and Its Consequences,” in Jazz among

the Discourses, ed. Gabbard (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995), 1–2; see also Gabbard,

Jammin’ at the Margins (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1996), 102; and Richard Cook,

Blue Note Records: The Biography (London: Secker and Warburg, 2001), 182.

17

One example can be found in Rolling Stone, no. 565, November 16, 1989, 1.

18

Rolling Stone, no. 600, March 21, 1991, 2. This was part of a larger GAP campaign

entitled “Individuals of Style,” which featured Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Maceo Parker,

Courtney Pine, and others. See John McDonough, “Jazz Sells,” Downbeat, October 1991, 34.

19

This includes methods taught by Jamey Aebersold, Jerry Coker, and David Baker.

For a more detailed account of these developments in jazz education, see David Ake, Jazz

Cultures (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 112–45 (chap. 5: “Jazz ’Traning:

John Coltrane and the Conservatory”).

20

Grover Sales, Jazz: America’s Classical Music (New York: Da Capo Press, 1992), 219.

JM2704_02.indd 439 11/22/10 5:06:10 PM

the journal of musicology

440

jazz in the concert hall on a regular basis. Described by Francis Davis

as “rebelling against non-conformity,”

21

Marsalis championed the great

composers of acoustic jazz while dismissing any nonacoustic endeavor

as a debased derivative of a pure art form. He was even more abruptly

dismissive of pop music and hip-hop. Inuenced heavily by jazz ide-

ologies of Stanley Crouch and Albert Murray, Marsalis became, to

quote Richard Cook, a “jazz media darling in an age when there simply

weren’t any others.”

22

Accepting interviews for magazines, television,

and newspapers as well as hosting jazz programs on National Public Ra-

dio and the Public Broadcasting System, Marsalis became the rare case

of a cultural producer (musician/composer) who was also a cultural

intermediary—a public intellectual whose inuence created boundar-

ies, denitions, and tastes for the public.

23

Reafrming the notion that

jazz was “America’s classical music,” he was (and still is) a gatekeeper of

the “jazz tradition.”

Although no time and place is ever truly homogeneous ideologi-

cally, the belief that jazz was a “serious music” became pervasive in

media discourse of the 1980s as jazz became associated with afuence,

sophistication, and a highbrow aesthetic that resisted being considered

a “popular music.”

24

Sonorities identied as jazz occupied the main-

stream cultural consciousness, and the political legitimacy of jazz would

affect the reception of those who borrowed from the imagery and mu-

sic of the genre.

Jazz Rap

Whereas musicians of the 1980s jazz mainstream tended to cultivate

older styles idiomatically intact, hip-hop artists were envisioning music

of the past differently, rst through the technology of the turntable,

21

Francis Davis, In the Moment: Jazz in the 1980s (New York: Oxford University Press,

1986), 29–41 (“The Right Stuff”). See also Stuart Nicholson, Is Jazz Dead? (Or has it moved

to a new address) (London: Routledge, 2005), 23–52 (“Between Image and Artistry: The

Wynton Marsalis Phenomenon”).

22

Cook, Blue Note Records, 212–13.

23

Perhaps the most exemplary document of his views at the time can be found

in an article Marsalis wrote for the New York Times (July 31, 1988) entitled “What Jazz

Is—and Isn’t,” subsequently anthologized in Walser, Keeping Time, 334–39. For more on

cultural intermediaries, see Keith Negus, “The Work of Cultural Intermediaries and the

Enduring Distance Between Production and Consumption,” Cultural Studies 16, no. 4

(2002): 501–15.

24

There were multiple forms of jazz in the 1980s, with a number of ideological

connotations. Two worth mentioning are the more avant-garde streams of jazz, exempli-

ed by John Zorn and Anthony Braxton, and smooth jazz, which was a lighter version of

fusion from the 1970s. Smooth jazz artists such as Kenny G and David Sanborn are often

the focus of criticism from jazz purists, but their albums were commercially successful in

the 1980s and helped to form their own signicant jazz subgenre.

JM2704_02.indd 440 11/22/10 5:06:11 PM

WILLIAMS

441

then with samplers and other studio technology to create something

new. Both hip-hop and jazz had their origins as dance music; they were

largely the product of African American urban creativity and innova-

tion, and they shared rhythmic similarities: hip-hop and hard-bop jazz

of the 1950s and 60s were stylistically dened by a dominance of the

beat. Bebop jazz was a source of inspiration for many 1950s hipsters

and beat poets, and poetry was often recited with jazz accompaniment

(almost as a proto-rap form). Improvisation (more specically, the abil-

ity to improvise in the generic idiom) was linked to authenticity in both

jazz and hip-hop.

25

For mainstream jazz, in addition to the technical

mastery of one’s craft, it was what one did with the past that made one

authentic, and battles (or “cutting contests”) were not uncommon in

the early days of jazz as a way to gain respect (and gigs) in the musical

community; in certain subgenres of hip-hop, one’s ability to freestyle

(improvise raps on the spot) and to “battle” rap are sure signs of au-

thenticity in certain “underground” rap and DJ circles.

Rap groups such as De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Gang Starr,

and Digable Planets emerged from the late 1980s and early 90s with

categorizations for their music, including jazz rap, jazz-hop, jazz hip-

hop, hip-bop, new jazz swing, alternative rap, and others.

26

Most overtly,

the shared African American musical lineage of jazz and hip-hop be-

came a focus in the reception of jazz rap in interviews and other jour-

nalism. From a practical standpoint, the artists’ parents and siblings of-

ten had record collections that were readily available and could be used

to sample.

27

In fact, some rap artists had jazz musician parents, most

25

Reginald Thomas, “The Rhythm of Rhyme: A Look at Rap Music as an Art Form

from a Jazz Perspective,” in African American Jazz and Rap: Social and Philosophical Ex-

aminations of Black Expressive Behavior, ed. James L. Conyers (London: McFarland, 2001),

165–66. For examples of underground rap scenes, see Marcyliena Morgan, The Real

Hiphop (Durham: Duke University, 2009), and Anthony Kwame Harrison, Hip Hop Under-

ground (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009). Cinematic examples of such battles

can be found in the Eminem quasi-biopic 8 Mile (2003), dir. Curtis Hansen.

26

The term “new jazz swing” can be found in Portia K. Maultsby, “Africanisms in

African American Music,” in Africanisms in American Culture, ed. Joseph Holloway, 2nd

ed. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005), 327. Jazz rap or alternative rap had

also been deemed (and dismissed as) “college boy” rap, no doubt inuenced by the high-

brow topics of groups like Digable Planets and jazz’s associations with college-educated,

middle-class audiences. Many groups, such as A Tribe Called Quest, did become popular

on college campuses before expanding to a wider audience. College radio stations also

had successful underground hip-hop communities that would also organize events on

campus. See Chang, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, 422; Shawn Taylor, People’s Instinctive Travels and

the Paths of Rhythm (New York: Continuum, 2007), 66; Krims, Rap Music, 65.

27

One example of a producer inuenced by his parents’ jazz tastes is DJ Premier;

Ty Williams “Rap Session—Hip-Bop: The Rap/Jazz Connection,” The Source, September

1992, 21. See also David Toop, The Rap Attack 2 (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1992), 189;

and Brian Coleman, Check the Technique: Liner Notes for Hip-hop Junkies (New York: Villard,

2007), 164–65, 235.

JM2704_02.indd 441 11/22/10 5:06:11 PM

the journal of musicology

442

recognizably rapper Nas, whose father Olu Dara occasionally performs

on his son’s albums. Rapper Rakim (of Eric B and Rakim) was a saxo-

phone player whose mother was a professional jazz and opera singer.

28

The father of turntablist Grandmaster D.ST (later DXT) managed jazz

musicians like Clifford Brown and Max Roach.

29

As Buttery of Digable

Planets raps, “my father taught me jazz, all the peoples and the anthem /

Ate peanuts with the Dizz and vibe with Lionel Hampton.”

30

If jazz and

hip-hop are most often treated as separate musical and cultural institu-

tions, then the linking of the two acted as a symbolic exchange, an alli-

ance that increased the social capital of both.

31

Many groups that sampled jazz were part of a loose collective called

the Native Tongues: Jungle Brothers, De La Soul, and A Tribe Called

Quest, all formed in New York in 1988, rapping politically and socially

conscious lyrics while promoting Afro-humanistic identities. Although

they were inspired by Afrika Bambaataa’s Zulu Nation, it was the New

York City scene generally that most directly inuenced both their jazz

awareness and their knowledge of early hip-hop. Taylor notes that A

Tribe Called Quest in particular “steered away from the ubiquitous funk

and old-school soul samples of their fellow Tongue members and em-

braced rock and roll and jazz. . . . They were socially relevant, proudly

black and whimsical, quirky and condent, a near perfect amalgama-

tion of the other two groups.”

32

The lyrics and imagery of these groups often displayed an ethos

most appropriately identied as bohemian,

33

and their references

spanned numerous countercultures, from hippies to Five Percenter cul-

ture, beatniks, and blaxploitation lms. In the case of Digable Planets,

overt references to bebop and hard bop musicians stood side by side

with their rendering of existential and Marxist philosophies. Album ti-

tles such as Digable Planets’s Reachin’: A Refutation of Time and Space and

A Tribe Called Quest’s People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm

28

Chang, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, 258.

29

Grandmaster D.ST was featured on the 1983 Herbie Hancock single “Rock It”

and this was one of the earliest high-prole collaborations between jazz and hip-hop art-

ists. S.H. Fernando, Jr., The New Beats: Exploring the Music, Attitudes, and Culture of Hip-Hop

(New York: Doubleday, 1995), 140.

30

Buttery, “Examination of What” (track 14) on Digable Planets, Reachin’ (A New

Refutation of Time and Space), (1:45).

31

Bourdieu makes the distinction between social capital and cultural capital in

“The Forms of Capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed.

John G. Richardson (London: Greenwood Press, 1986), 243–48.

32

Taylor, People’s Instinctive Travels, 9–10.

33

Krims, Rap Music, 65–70. Bohemianism is certainly a feature of the language and

style of the 1950s “hipsters” who also looked to jazz as part of a early cold war sensibility

of hipness. See Phil Ford, “Hip Sensibility in an Age of Mass Counterculture,” Jazz Perspec-

tives 2, no. 2 (2008): 121–63. And as Ford reminds us, “Elitism is essential to hipness,”

not only in contemporary jazz but also in cold war hip sensibilities more generally (142).

JM2704_02.indd 442 11/22/10 5:06:11 PM

WILLIAMS

443

project the complexity of their subject matter through an insider lan-

guage difcult to decipher (similar to arcane bebop song titles such as

“Epistrophy” and “Ornithology”). Both the obscurity of their lyrics and

their incorporation of jazz sonorities signaled a higher artistic plane—a

notion of rap as high art and expander of consciousness.

Jazz Codes

Musical elements that have been identied as jazz codes include a

walking acoustic bass, saxophones, trumpet with Harmon mute,

34

and

jazz guitar, to name a few.

35

As Steve Redhead and John Street have

written, authenticity “is rarely understood as a question of what artists

‘really’ think or do, but of how they and their music and image are

interpreted and symbolized,”

36

and the same could be said of genre

identications. For my purposes, the interpretation of jazz codes is an

issue of audience reception rather than intention or the identication

of sources for a jazz sample. Thus when Wynton Marsalis complained

in the late 1980s that “people don’t know what I’m doing, basically,

because they don’t understand music. All they’re doing is reacting to

what they think it remotely sounds like,”

37

he acknowledged that au-

thorial intent (or performer intent) may differ greatly from audience

interpretation. For example, an acoustic bass may signify a “live” jazz

aesthetic, even though it may be achieved through digital sampling. If a

rap group samples from a 1970s funk horn line, it may be identied in

its old context as funk; but in the newer context, the instrumentation of

sax and trumpet may be interpreted as jazz.

A jazz code falls under what Philip Tagg calls a genre synecdoche—

an instrument or musical structure that is shorthand for an entire style

or genre.

38

In jazz rap, this may be achieved by the timbre of a particular

34

The Harmon mute, specically designed for brass instruments, is made of metal

with a ring of cork around the outside so that air can escape only through the mute. It

creates a quiet but sharp and metallic sound and was often used to change timbre of the

trumpet or trombone in jazz big band music. It can be played with or without a metal

“stem” that drastically changes the sound when inserted in the mute. Its sound was spe-

cially associated with Miles Davis, who used the mute (without stem) frequently during

his long career.

35

This approach to jazz codes is particularly indebted to the semiotic methodolo-

gies of John Fiske and Philip Tagg.

36

Steve Redhead and John Street, “Have I the Right? Legitimacy, Authenticity and

Community in Folk’s Politics,” Popular Music 8, no. 2 (1989): 180. Redhead and Street

interpret Sting’s collaboration with jazz musicians for his rst solo album The Dream of the

Blue Turtles (1985) as a gesture of political legitimacy.

37

Rai Zabor and Vic Garbarini, “Wynton vs. Herbie: The Purist and the Cross-

breeder Duke It Out,” in Keeping Time, 342.

38

Philip Tagg, Introductory Notes to the Semiotics of Music, version 3 (1999), 26–27,

available at: http://www.tagg.org/xpdfs/semiotug.pdf (accessed August 22, 2009).

JM2704_02.indd 443 11/22/10 5:06:11 PM

the journal of musicology

444

instrument (e.g., saxophone) and the jazz performance approach to an

instrument (e.g., “walking” acoustic bass lines). The parameters of tim-

bre, instrumentation, and performance approaches are arguably more

important to jazz identity than syntactical processes (melody, harmony,

and other musical features that can be represented in score notation).

Jazz as a performance approach produces a particular jazz feel (nota-

bly “swung” eighth notes and expressive sub-syntactical microrhythmic

variations)

39

along with the associations of particular instruments and

their timbres. (Admittedly, this is better represented through recorded

excerpts than through the “categorical perception”

40

of a musical score,

though I provide some transcriptions for illustrative purposes below.)

41

Technically speaking, it is the sub-syntactical level of expressive timing

(that which contributes to Keil’s “engendered feeling”) that character-

izes a swing feel. As Matthew Buttereld argues, the groove in jazz arises

not from syntactical processes, but from expressive microtiming at the

sub-syntactical level.

42

These are the parameters that contribute to the

identication of jazz codes.

Codes, like music genres, simplify in order to clarify and categorize

a heterogeneous reality. The audience then interprets meanings with

regard to these codes, actively constructing from a text (in this case, a

recording) and changing the text in the process. Rather than simply a

transmission from media to individual, there is a conversation between

the two. The attempt to x such unxed texts through genre categori-

zation is one of the two strategies the music industry has for controlling

unreliable demand (creating stars is the other).

43

The texts in question

are nonetheless sites of constant shifts and change, so that interpreta-

tion is largely dependent on the perspective of listeners or interpretive

communities. For jazz rap, the socially situated interpretations point

to the 1980s mainstream jazz art ideology. What follows are examples

of “jazz codes” in the lyrics, imagery, and “beats” of two canonical jazz

39

Matthew W. Buttereld, “The Power of Anacrusis: Engendered Feeling in Groove-

Based Musics,” Music Theory Online 12, no. 4 (2006).

40

“Categorical perception” is a term that Eric Clarke uses to describe the way we

perceive music in certain durational categories (e.g., quarter note, eighth note, half note,

etc.). See Eric F. Clarke, “Rhythm and Timing in Music,” in The Psychology of Music, ed. Di-

ana Deutsch, 2nd ed. (Burlington: Burlington Academic Press, 1999), 490.

41

Most hip-hop studies take a sociological or historical approach rather than a

musicological one. In fact, the use of musical notation is, more often than not, seen as

exclusionary and elitist by many who do academic work on hip-hop music and culture.

My intention in including music examples is primarily to emphasize the importance of

the musical detail on hip-hop recordings, notably what may be described as an intra-

musical discourse, an element whose agency all too often goes unexplored in hip-hop

scholarship.

42

Buttereld, “The Power of Anacrusis,” 4.

43

Simon Frith, “The Music Industry,” in The Cambridge Companion to Pop and Rock, ed.

Simon Frith, John Street, Will Straw (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 35.

JM2704_02.indd 444 11/22/10 5:06:12 PM

WILLIAMS

445

rap groups: A Tribe Called Quest and Digable Planets. (Here I will use

the hip-hop terminology “ow” to designate the delivery of rap lyrics

and “beat” to refer to its sonic complement: not only its percussive ele-

ments, but all sounds on the recording that do not include the rapper’s

“ow.”)

In A Tribe Called Quest’s second album, The Low End Theory

(1991), where jazz bassist Ron Carter is featured on “Verses from the

Abstract,” jazz codes can be recognized throughout; the sounds of

acoustic bass, saxophone, and vibraphone are the most prominent of

these.

44

Q-Tip and Phife’s lyrics (on The Low End Theory) feature criti-

cism of the music industry and the more commercially successful pop,

R&B, and “new jack swing” artists.

45

Q-Tip pointedly sets himself apart

from pop rappers in “Check the Rhime”:

Industry rule number four thousand and eighty,

Record company people are shady.

So kids watch your back ’cause I think they smoke crack,

I don’t doubt it. Look at how they act.

Off to better things like a hip-hop forum.

Pass me the rock and I’ll storm with the crew and . . .

Proper. What you say Hammer? Proper.

46

Rap is not pop, if you call it that then stop (2:54–3:14).

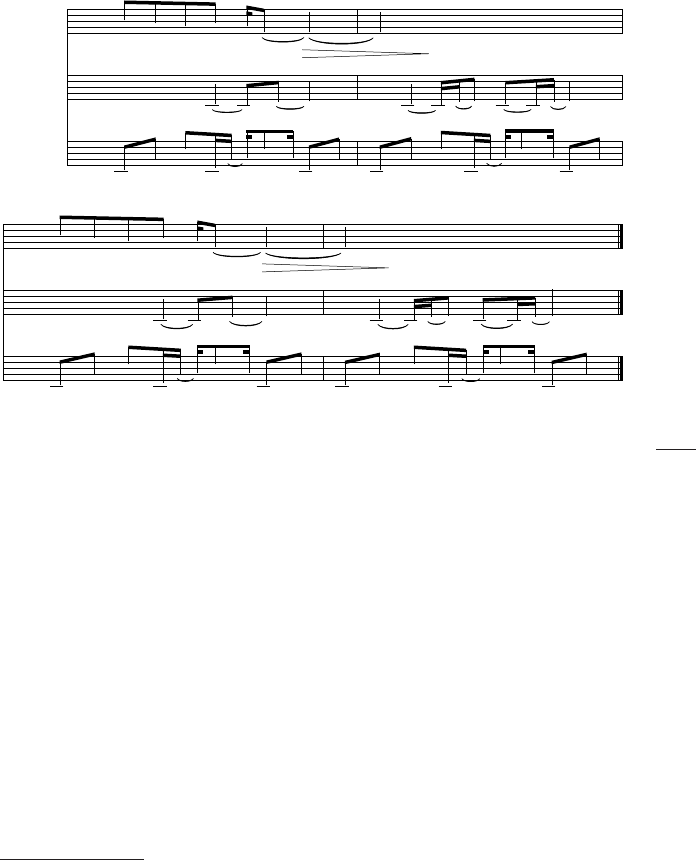

Example 1 shows the “Check the Rhime” saxophone phrase from

the chorus.

47

Acting as a jazz code, the sampled saxophone phrase pro-

vides a sonic alternative to R&B and pop rap, a musical complement

to the lyrical meaning. Phife invokes a similar distancing from pop on

their second single, titled “Jazz (We’ve Got),” when he claims that their

songs are “strictly hardcore tracks, not a new jack swing” (2:02). The

44

A Tribe Called Quest was formed in Queens in 1988. The members of the group

were producer/DJ Ali Shaheed Muhammad, MC/producer Q-Tip (Jonathan Davis), and

MCs Phife (Malik Taylor) and Jarobi (only on the rst album). Their debut album People’s

Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm (1990) also featured a number of jazz samples.

For analyses of unity between beat and ow in ATCQ’s “Scenario,” “Can I Kick It,” and

“Push It Along,” see Kyle Adams, “Aspects of the Music/Text Relationship in Rap,” Music

Theory Online 14, no. 2 (2008).

45

New jack swing was a style from the late-1980s and early-1990s that fused hip-hop

and R&B into a hybrid pop style. Notable producers included Teddy Riley, Jimmy Jam,

and Terry Lewis. The song “Show Business” discusses the difculties of working in the rap

music industry, structuring the common artist/group vs. music industry paradigm.

46

The use of the word “proper” in this instance is a reference to the catchphrase

used by MC Hammer in a 1991 Pepsi commercial, which introduced him as “MC Ham-

mer: rap star and Pepsi drinker.”

47

This phrase is sampled from “Love Your Life” by the Average White Band, Soul

Searching (1976) (also sampled by Fatboy Slim for “Love Life”). The song also samples

“Hydra” by Grover Washington Jr. from Feels So Good (1975) and the bass line from Min-

nie Riperton’s “Baby This Love I Have” and Steve Miller Band’s “Fly Like an Eagle.”

JM2704_02.indd 445 11/22/10 5:06:12 PM

the journal of musicology

446

chorus of “Jazz” contains a sample of Lucky Thompson playing the rst

four measures of the jazz standard “On Green Dolphin Street.” The

song opens with the group chanting “We’ve got the jazz” repeatedly

with a jazz drummer (on brushes) and an acoustic bass pedal point.

Another example of what may be understood as an instance of a

pop/rap binary comes from “Excursions,” the rst track in the Low End

Theory. After a four-measure bass intro (with no drums), Q-Tip raps the

following verse (to the solo acoustic bass accompaniment):

Back in the days when I was a teenager

Before I had status and before I had a pager

You could nd the Abstract [Q-Tip] listening to hip-hop

My pops used to say it reminded him of bebop

I said, well daddy don’t you know that things go in cycles

The way that Bobby Brown is just ampin’ like Michael.

These opening lyrics acknowledge the African American lineage from

bebop to hip-hop, yet a distinction is drawn between black “pop music”

such as that of Michael Jackson and Bobby Brown on one hand, hip-

hop and bebop on the other. “Excursions” opens with an acoustic bass

gure that loops throughout the song (ex. 2a).

48

48

This bass riff is from “A Chant for Bu” by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. The

original is in ¾ time, and producer Q-Tip was able to copy-and-paste the rst two eighth

notes of the measure to create a beat in common time: “I took the original bass line,

which was in ¾ time, and I put a beat onto the last measure to make it

4

/

4

. I made the

drums underneath smack, so it had that big sound. And I put a reverse [Roland TR-] 808

H

@

@

@

H @

@

@

@

@

@

Y

Alto and Tenor

Saxophones

= 98

O

example 1. “Check the Rhime” (0:05)

@

@

@

@

@

@

L

L

L

L

L

L

Y

Acoustic

Bass

= 84

O

3

example 2a. “Excursions” (0:00)

JM2704_02.indd 446 11/22/10 5:06:13 PM

WILLIAMS

447

The acoustic timbre sampled here signies a musical authentic-

ity that nds its roots in both folk music and jazz; and on the chorus,

samples from a recording of “Time” on the 1971 album This Is Madness

from The Last Poets represents a borrowing of both lineage and the

cultural prestige of poetry (ex. 2b).

Just as Wynton Marsalis and other neoclassical, conservative jazz

musicians in the 1980s distanced themselves from pop music, A Tribe

Called Quest was distancing rap from pop.

49

In order to classify A Tribe

Called Quest as “true” hip-hop, Q-Tip distinguished himself from pop

rappers like MC Hammer. Both beat and ow work together to gener-

ate a sense of authentic or noncommercial (i.e., countercultural) iden-

tity. A Tribe Called Quest drew on a long-standing art-versus-commerce

myth by evoking a sense of authenticity that aligned jazz, so-called al-

ternative rap, and other musics. Similarly, criticizing the popular music

industry positioned ATCQ on the outside, again distancing them from

associations of corruption and decay often attributed to mass music.

[drum machine] behind it, right before the beat actually kicks in. I loved that Last Poets

sample on there, too.” Quoted in Brian Coleman, Check the Technique, 443.

49

Of course, this distancing from pop had been a phenomenon before the 1980s:

bebop musicians distanced themselves from “commercial” swing music of the 1930s and

40s, and rock and punk musicians have often dened themselves against pop in lyrics

and interviews. Even earlier, Louis Armstrong received criticism for surviving the Great

Depression by having a singing career on Broadway.

@

@

@

@

¤

H

@

H

@

@

@

@

@

@

@

@

¤

H

H

L

L

L

L

L

L

Y

Y

Y

Trumpet

in B

Tenor

Saxophone

Acoustic

Bass

@

3

example 2b. “Excursions” (1:40)

JM2704_02.indd 447 11/22/10 5:06:14 PM

the journal of musicology

448

Economic denial is a familiar story, a quality of bourgeois production

found in jazz, rap, and many other forms of popular music and art as a

mark of their authenticity.

50

ATCQ’s recordings thus stage an awareness

of mainstream commercialism as other by suggesting that artists such as

MC Hammer and Bobby Brown are operating under a false conscious-

ness compared with their informed, less mainstream rap counterparts,

even if this is not explicitly the case. Such dichotomies are reminiscent

of what Phil Ford calls the “asymmetrical consciousness” of the hip-

ster and the square (“The hipster sees through the square but not vice

versa”).

51

Of all the jazz rap groups from this period, Digable Planets ar-

guably aunted jazz connections and references most overtly by men-

tioning jazz musicians in many of their lyrics and using numerous jazz

samples.

52

Their bohemian image, which had been largely borrowed

from the concept of the 1950s hipster, was evident in their use of such

jazz-related words as “cool,” “cat,” “hip,” and “dig.” Jazz was also used

as a marketing tool for the group. An ad for their debut album in The

Source magazine (April 1993) contained the headline “jazz, jive, poetry,

& style.” The same issue contained a Digable Planets interview with pic-

tures of the members in a jazz club setting, both male members being

shown with a trumpet. And their rst music video, for “Rebirth of Slick

(Cool Like Dat),” featured the group performing in a jazz club setting

in New York City. Jazz became the vehicle by which to market Digable

Planets and the framework to use for reviews, interviews, and other

journalism.

53

The complex collage of terminology and cultural references in their

lyrics borrowed from multiple countercultures: 1950s hipsters and beat

poets, spoken word poetry, hippies, Five Percenter Culture, “old school”

hip-hop (Fab 5 Freddy, Crazy Legs of the Rock Steady Crew, Sugarhill Re-

50

The idea of being “uncommercial” or not “selling out” was a characteristic of

authenticity found in a number of music genres. It extends at least as far back as the Ro-

mantic notions of transcendence and timelessness in nineteenth-century music. Bourdieu

has written about the idea of economic disinterestedness as a bourgeois production illu-

sion; see Pierre Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital,” 242.

51

Ford, “Hip Sensibility in an Age of Mass Counterculture,” 123.

52

Formed in 1989, Digable Planets included members Buttery (Ishmael Butler,

from Brooklyn), Doodlebug (Craig Irving, from Philadelphia), and Ladybug (Mary Ann

Viera, from Maryland).

53

“Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat)” was released in November 1992 in anticipa-

tion of the February 1993 album release of Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time and Space).

“Rebirth of Slick” received heavy radio airplay by January, the accompanying music video

was prevalent on both MTV and BET, and it had sold 400,000 copies by early February.

This single is by far the most well known from the group; it reached number 1 on the

Billboard Hot Rap chart and number 15 on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles chart, and the

album reached number 15 on the Billboard Top 200. “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat)”

also received a Grammy in 1994 for Rap Performance by a Duo or Group.

JM2704_02.indd 448 11/22/10 5:06:15 PM

WILLIAMS

449

cords), and other poets (The Last Poets, Nikki Giovanni, Maya Angelou).

There were jazz references (Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker, Hank Mob-

ley, Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach), allusions to 1970s blaxploitation lms

(e.g., Cleopatra Jones), and other signiers of African American identity

(e.g., Afros and other hair references such as “don’t cover up your nappy,

be happy with your kinkin” from “Examination of What”). As in so many

American countercultures, particularly those in the 1950s and 60s, refer-

ences to drugs (usually marijuana, as “nickel bags”) complemented an

antiauthoritarian atmosphere (speaking against Uncle Sam, the “pigs,”

and “fascist” conservatives). Lyrical references to Sartre, Camus, and po-

litically tinged lyrics about abortion (in the song “La Femme Fetal”) were

frequently mentioned in reviews of the album.

The sonic and visual imagery of the jazz club played a signicant

role in their music as well as in their media image. At the end of the

rst track of Reachin’, “It’s Good to Be Here” (which included jazz gui-

tar, trumpet, and acoustic bass), an announcer (3:25) begins to intro-

duce the group to the backdrop of a jazz piano vamp, with bass and

nger snapping on the backbeat (beats 2 and 4 in

4

/

4

time, ex. 3):

Good evening insects, humans too

The Cocoon Club

54

is pleased to present to you tonight a new band

Straight from sector six and the colorful ghettos of outer space

They are some weird mother fuckers but they do jazz it up

So let’s bring them out here, yeah.

54

The “cocoon club” is perhaps a reference to the famous Cotton Club of Harlem

as well as a continuation of the insect metaphors in their lyrics and stage names.

example 3. “Jazz Club Motive” from “It’s Good to Be Here” (3:35)

¤

¬

¬

¬

¤v

¬

@

d

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

h

¡

+

Keyboard

w/Piano Sound

= 112

O

Bass

Ride Cymbal

Finger Snaps

swing feel vamp

JM2704_02.indd 449 11/22/10 5:06:15 PM

the journal of musicology

450

Following these words from the announcer, Buttery introduces

the group and then says “the mind is time / the mind is space / a

horn rush, a bass ush / the mind’s the taste / so sit back, enjoy the

set, yeah,” later repeating this line during a fadeout. The music video

for “Rebirth of Slick” features the members taking the New York sub-

way to a local jazz club where they perform with a Japanese rhythm

section to a diverse, yet small, audience. (The entire video is shot in

black-and-white.) The irony of this is obvious—promoting a live aes-

thetic of a jazz club for a recording that had been constructed through

digital sampling. The presence of jazz instruments nonetheless suggests

“liveness.”

55

Because of the cultural associations with acoustic jazz (in

this case, acoustic bass, piano, and drums playing a jazz vamp), these

jazz instruments would be heard as live, thereby suggesting the authen-

ticity of unmediated expression and creativity. No doubt the narration

of the “announcer” plays a crucial role in creating a jazz club sound-

scape as well. A similar effect occurs at the end of “Swoon Units,” where

a jazz club “sound stage” is created by means of a jazz rhythm section

and the sound of audience talking (as Buttery says he is “hippin up

the nerds”). At the end of the album, each member of the band pro-

vides a nal stanza with the earlier jazz club motive sonic background.

These three separate jazz club interludes on the album use the same

musical material, thereby solidifying the interpretation of various jazz

tropes as central themes or as fundamental to the group’s image and

style.

56

Their debut single “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat)” is exemplary

in the use of jazz codes within hip-hop beats. As shown in table 1, the

instrumental introduction is sixteen measures long (4 + 4 + 4 + 4); the

rst four measures include the solo walking acoustic bass phrase that

repeats throughout the song (as bass gure 1; see ex. 4a).

57

The second four measures consist of bass gure 1 accompanied by

nger snapping on beats 2 and 4. The third set of four measures adds

drums, and the fourth adds a horn line with saxophone and trumpet.

Verses include acoustic bass and drums, with a variation on the bass line

(bass gure 2) in every concluding four-measure unit. On the chorus,

55

The most extensive study of “liveness” is Philip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in

a Mediatized Culture (London: Routledge, 1999).

56

“Last of the Spiddyocks,” a track with numerous jazz musician references and

features a Harmon muted trumpet in the beat, ends with audience applause—another

signier of liveness.

57

The bass line also features as a leitmotiv in “Appointment at the Fat Clinic”

(track 11) and “Escapism (Gettin’ Free)” (track 10), not as central to the basic beat as in

“Rebirth of Slick,” but as a small moment within the other two songs. This bass line, now

associated with Digable Planets’ moment of success, has been sampled by later rap artists

(e.g., E-40 for “Yay Area”).

JM2704_02.indd 450 11/22/10 5:06:16 PM

WILLIAMS

451

the words “I’m cool like that” repeat every two beats with the horn line

from the intro (with the bass and drums, ex. 4b).

The particular sonic texture from the chorus (horns, bass, and

drums) becomes the central jazz trope in the song. The drum sounds

(not given in the transcription) include a modied beat from The Hon-

eydrippers’ “Impeach the President” (1973), which is an often-sampled

example 4a. “Rebirth of Slick (Cool like Dat)”

L

L

L

C

L

Y

C

v

= 98

O

4

7

Bass figure 1

C C

C

Bass figure 2 (last 4 bars of each verse)

One-bar rhythm section

break going into chorus

example 4b. “Rebirth of Slick” chorus (0:29)

L

L

Y

Y

Y

Y

C

Acoustic

Bass

Trumpet

Tenor

Saxophone

& Trombone

Finger Snaps

C

TABLE 1

“Rebirth of Slick,” opening measures

Instrumental introduction measures

Solo acoustic bass (bass gure 1) 1–4

Bass gure 1 with nger snaps 5–9

Bass gure 1 with nger snaps and drums 10–14

Bass gure 1 with snaps, drums, and horn line 15–19

JM2704_02.indd 451 11/22/10 5:06:17 PM

the journal of musicology

452

funk song. The track is still identiable as jazz through the use of bass

and horns, although it does not use jazz-style drum sounds (a point

of comparison would be the drum sounds on A Tribe Called Quest’s

“Jazz”).

58

Doodlebug’s third verse of “Rebirth of Slick” demonstrates the ab-

stract, specialist language of their lyrics:

We get you free ’cause the clips be fat boss

Them dug the jams that commence to goin’ off

She sweats the beats and ask me could she puff it

Me I got crew kid, seven and a crescent

Us cause a buzz when the nickel bag a dealt

Him that’s my man with the asteroid belt

They catch a zz from the Mr. Doodlebig

He rocks a tee from the Crooklyn nine pigs

Rebirth of slick like my gangster stroll

The lyrics just like loot come in stacks and rolls

You used to nd the bug in a box with fade

Now he boogies up your stage plaits twist the braids.

Both A Tribe Called Quest and Digable Planets used complex lyrics that

may appear incomprehensible to a square outsider. As Kyle Adams has

argued, the lack of narrative unity or cohesion in the lyrical content of

groups like A Tribe Called Quest can be explained through a rapper’s

desire to match the sounds and rhythm of their “ow” to a precom-

posed “beat.”

59

Even if this is the case, connections to 1950s hipster ter-

minology signify a loosely unied countercultural or “hip” ethos be-

tween beat and ow.

60

Groups like A Tribe Called Quest and Digable

Planets were negotiating a complexity of topics and ideas musically and

lyrically, and a closer reading of the two groups would show striking dif-

ferences in a number of ways.

61

But in the media reception of many of

these groups, jazz became a readily identiable unifying force.

58

The timbres of funk drum sounds are a rmly ingrained sonic signier of hip-

hop, beats that allow a surprising amount of exibility for the sound of the overall prod-

uct, depending on the other sounds sampled or borrowed. The bass line and horn gures

derive from Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’ “Stretchin” from the album Reections in

Blue (1978).

59

See Adams, “Aspects of the Music/Text Relationship in Rap.”

60

I do not mean to imply here that nding unity should be the goal in music analy-

sis of any kind, as smaller units of meaning can also warrant investigation in the close

reading of music recordings. See Justin A. Williams, “Beats and Flows: A Response to Kyle

Adams,” Music Theory Online 15, no. 2 (2009).

61

Though I focus on jazz references in these groups, it is worth acknowledging the

high degree of unconcealed intertextuality in hip-hop music and culture more generally,

and I would go as far to say that it forms the fundamental aspect of hip-hop aesthetics.

JM2704_02.indd 452 11/22/10 5:06:17 PM

WILLIAMS

453

Media Reception

Jazz rap groups like A Tribe Called Quest were often dened by

their sounds in ways that their counterparts in other rap subgenres

could not be. To quote Crane, “Cultural information that is already fa-

miliar because of its associations with previous items of culture is more

readily assimilated into the core,”

62

the “already familiar” being jazz

codes and their attached high art ideologies. The “core,” in this case, is

the mainstream discourse as framed by various media; and print media

such as Rolling Stone, The Source, Vibe, and Rap Pages contextualized the

jazz samples in terms of class, intelligence, and artistic achievement.

One Rolling Stone review described the sounds of ATCQ’s rst al-

bum as “funkied quiet-storm pseudo-jazz you might expect young Afro-

centric upwardly mobiles to indulge in when they crack open that bottle

of Amaretto and cuddle up in front of the gas replace: plenty of sweet

silky saxophones.”

63

John Bush wrote “Without question the most intel-

ligent, artistic rap group during the 1990s, A Tribe Called Quest jump-

started and perfected the hip-hop alternative to hardcore and gangsta

rap.”

64

One writer expressed that the Low End Theory “demonstrated that

hip-hop was an aesthetic every bit as deep, serious and worth cherishing

as any in a century plus of African-American music . . . giving a rap the

same aesthetic weight as a Coltrane solo.”

65

Journalist Brian Coleman

wrote of the group “Every time they hit the studio they added a serious,

studious, jazz edge to their supremely innovative productions.”

66

Other

adjectives used suggested that they were “more cerebral”

67

than other

styles, had a “more intellectual bent,”

68

and were “more reective.”

69

62

Diana Crane, The Production of Culture: Media and the Urban Arts (London: Sage,

1992), 10.

63

Chuck Eddy, “Review of People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm,” Rolling

Stone, no. 576, April 19, 1990, 15.

64

John Bush, “A Tribe Called Quest,” allmusic.com, available at: http://allmusic.

com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&sql=11:dcxq95ld6e (accessed June 1, 2007).

65

Peter Shapiro, The Rough Guide to Hip-Hop, 2nd ed. (London: Rough Guides,

2005), 363, 365.

66

Coleman, Check the Technique, 435.

67

Big B, “Record Report—Arrested Development,” The Source, May 1992, no. 32,

56. See also “Jazz Rap,” in The All Music Guide to Hip Hop: The Denitive Guide to Rap and

Hip Hop, ed. Vladimir Bogdanov (San Francisco: Backbeat, 2003), ix.

68

“Given its more intellectual bent, it’s not surprising that jazz-rap never really

caught on as a street favorite, but then it wasn’t meant to.” “Jazz Rap,” in The All Music

Guide to Hip Hop, ix.

69

“Among the leading proponents of this more reective style (including De

La Soul and the Jungle Brothers), A Tribe Called Quest was arguably the most accom-

plished.” Considine and Randall, “A Tribe Called Quest,” from The New Rolling Stone Al-

bum Guide, 2004, on Rollingstone.com, available at: http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/

atribecalledquest/biography (accessed June 1, 2007).

JM2704_02.indd 453 11/22/10 5:06:18 PM

the journal of musicology

454

Such descriptions implied the elevation of this music to the status of a

(bourgeois) high art comparable to jazz.

For Digable Planets, media reception of Reachin’ also focused on

jazz as a high cultural facet of their music. Lyrical references to jazz

and musical borrowing of jazz codes featured prominently in reviews.

Digable Planets were described as “accessible without succumbing to a

pop mentality.”

70

Kevin Powell wrote in his review that Digable Planets

“is everything hip-hop should be: artistically sound, unabashedly con-

scious and downright cool. And Digable Planets is the kind of rap act

every fan should cram to understand.”

71

Both reviews noted an element

of intellectualism in their music, the former explicitly citing jazz and ex-

istentialist references. Another reviewer wrote that in Reachin’ “sampled

snatches of music from jazzmen Sonny Rollins and Art Blakey conjure

the feel of smoky bebop clubs and two-drink minimums. . . . These jazzy

undercurrents give the album a laid-back quality that refutes the riotous

stereotype of rap.”

72

The frequent juxtaposition of jazz rap with rapper/producer Dr.

Dre is particularly pertinent in the context of Digable Planets since

both had albums and singles released at about the same time.

73

Dr.

Dre’s album The Chronic is often seen as the yardstick historically and ge-

nerically when gangsta rap begins to dominate the rap mainstream and

crosses over into pop music realms.

74

ATCQ had also been compared

directly with Dr. Dre, as Kevin Powell wrote that A Tribe Called Quest

and De La Soul provided “nuthin’ but ‘P’ things: poetry, positive vibes,

and a sense of purpose.”

75

This was a reference to Dr. Dre’s “Nuthin’

But a ‘G’ Thang,” the rst single from The Chronic. Thus when the me-

dia reviewed Digable Planets or other jazz rap artists and albums, they

contrasted jazz rap with Dr. Dre (and his label Death Row Records),

viewing the latter as representative of a gangsta rap mainstream. The

distinctions drawn encompassed sonorities used, lifestyles promoted,

and ideologies implied. One article states:

70

Editors of The Source, “Pop Life,” The Source, January 1994, 26.

71

Kevin Powell, “Review of Reachin’ (A Refutation of Time and Space)” (4 stars), Rolling

Stone, no. 650, February 18, 1993, 61. Powell is most likely referencing the MC Lyte song

“I Cram to Understand You,” as intertextual references were often as important to hip-

hop journalism as it was to the music.

72

Farley, “Hip-hop Goes Bebop.”

73

Both Digable Planets (“Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat)”) and Dr. Dre (“Nuthin’

But a ‘G’ Thang”) had a single and music video permeating media space at the same

time. See Billboard, February 6, 1993. Both singles were nominated for the Best Rap Per-

formance by a Duo or Group Grammy Award, with Digable Planets winning the award.

74

See Chang, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, 420; and Eithne Quinn, Nuthin’ but a “g” Thang:

The Culture and Commerce of Gangsta Rap (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 161.

75

Kevin Powell, “Review of Midnight Marauders and Buhloone Mindstate,” Vibe, No-

vember 1993, 103.

JM2704_02.indd 454 11/22/10 5:06:18 PM

WILLIAMS

455

In the early 1990s, while Suge Knight’s Death Row records dominated

hip-hop with artists like Dr. Dre and Tupac, Digable Planets chose the

same high road that De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest had already

taken—they all but ignored gangsta culture. MCs Doodlebug, Butter-

y, and the sweet-voiced Ladybug combined a positive vibe with jazz

samples to create ultra-laid-back joints that provoked head bobbing

rather than drive-bys. Their debut, Reachin’, invaded college boom

boxes and birthed the Top 20 hit and Grammy winner “Rebirth of

Slick (Cool Like Dat).”

76

Placing De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, and Digable Planets on a

“high road” in opposition to Death Row artists like Dr. Dre and Tupac

Shakur juxtaposes the two with respect to subgenre and implies both

Digable Planets’ perceived audience and their listening space (“college

boom boxes”). Although both Dr. Dre and Digable Planets were consid-

ered rap music, for many the two represented opposite ends of a rap

spectrum. Such positioning, constructed by those who worked within

these imagined juxtapositions—including artists, media, fans, and the

industry—served to legitimate the artists’ own practices.

77

Jazz Codes and Meaning

Jazz is of course by no means univocal. It is important to note that

the jazz art ideology identied here is far from the only existing identity

for jazz in the 1980s and other eras. For example, in 1950s lm noir,

“crime jazz” often accompanied the corrupted, dark side of the city;

jazz projected sex, drugs, and other vices of a depraved urban land-

scape (e.g., The Sweet Smell of Success, The Man with the Golden Arm). As

bebop musicians were crafting an elite, virtuosic music appreciated by

hipster-intellectuals, jazz-inuenced lm scores used instruments such

as a scooping jazz saxophone to represent the sexuality of a femme fatale.

This is still evident in recent parodies of lm noir, for example on the

television cartoon series The Simpsons.

78

And although this essay is pri-

marily concerned with the use of jazz in the hip-hop world, there were

76

David Malley, “Digable Planets,” Rolling Stone Album Guide, 2004, available at:

http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/digableplanets/biography (accessed June 1, 2007).

77

Many other hip-hop groups, such as Organized Konfusion, Stetsasonic, Main

Source, Black Moon, Freestyle Fellowship, The Roots, Quasimoto, and Souls of Mischief

have incorporated jazz codes that have contributed to their alternative rap categoriza-

tions. Although the media gave much less attention to jazz rap after the mid-1990s, the

link between jazz and hip-hop continues into the twenty-rst century with artists including

U.S. trumpeter/rapper Russell Gunn, U.S. pianist Robert Glasper, and U.K. saxophonist/

rapper Soweto Kinch.

78

These musical tropes were still used in the 1980s; one example was the use of the

saxophone in the action series MacGyver for a sexually charged fantasy sequence between

MacGyver and a woman.

JM2704_02.indd 455 11/22/10 5:06:18 PM

the journal of musicology

456

instances in which inuence owed in the other direction as well: art-

ists closer to the jazz world who collaborated with musicians and ideas

from hip-hop scenes in the 1980s and 90s.

79

Were such practices defensible artistically? At worst, the less con-

servative jazz musician who used elements from hip-hop or the hip-hop

producer who digitally sampled from jazz records might be accused of

gravitating to whatever was commercially popular and protable at the

time. Record labels, by the same token, could be criticized for fostering

hip-hop and jazz collaboration in order to rebrand an old genre and

thus sell back catalogues. At best, jazz musicians who borrowed and

collaborated with hip-hop could be said to improve the genre, staying

close to their musical lineage while trying something new in the spirit

of jazz as a verb rather than a noun. Thus whereas jazz codes added a

degree of sophistication and cultural elevation to rap, hip-hop codes,

such as turntable scratches and hiss from sampled vinyl, could be heard

on a number of jazz recordings as “subcultural capital” said to signify

hipness or coolness.

80

The examples cited above help show how jazz can symbolize a va-

riety of meanings, depending on context and interpretive community,

for example high culture, the “street,” sexuality, hipness, elite tastes, or

urban corruption. However, it was jazz, constructed and distributed as

high art in the 1980s mainstream culture industries, that proved to be

the most pervasive ideology in contemporary cultural interpretations.

As Robert Fink has written, there is now a redenition of art music that

includes jazz (and rock); new composers borrow from rock and jazz, so

that “postminimalism’s embrace of alternative rock/jazz culture is arty

composers turning not away from artiness, but toward it.”

81

In many of these cases, the interpretation of jazz codes tends to-

ward the general rather than the specic, so that the precise meanings

79

For example, three years after Gang Starr’s successful “Jazz Thing” (where rapper

Guru stated, “The 90s will be the decade of a jazz thing”), Guru made a hip-hop album

entitled Jazzmatazz Vol. 1 (1993) in collaboration with various jazz musicians including

Branford Marsalis, Donald Byrd, and Courtney Pine, and he later produced three sub-

sequent volumes of the series (vol. 2, 1995, vol. 3, 2004, vol. 4, 2007). At this time, jazz

musicians such as Herbie Hancock, Branford Marsalis, Quincy Jones, Wallace Roney, and

Greg Osby were making hip-hop inuenced albums. Additionally, Blue Note Records

allowed the group US3 (led by British producers Geoff Wilkinson and Mel Simpson)

to sample extensively from their catalogue free of charge, producing Hand on the Torch

(1993), which became the top-selling album on Blue Note Records at the time, and the

rst to reach platinum sales in the United States. Their single “Cantaloop (Flip Fantasia)”

received widespread radio play and added to the jazz and hip-hop fusion trends at the

time. For information on the use of electronics, turntables, and sampling technology in

more recent jazz, see chap. 6, “Future Jazz,” in Nicholson, Is Jazz Dead?

80

“Subcultural capital” is theorized in Sarah Thornton, Club Cultures (Middletown:

Wesleyan University Press, 1996), 10–14.

81

Robert Fink, “Elvis Everywhere,” American Music 16, no. 2 (1998): 146.

JM2704_02.indd 456 11/22/10 5:06:18 PM

WILLIAMS

457

of songs can be less important than what the genre has been imag-

ined to represent. In an attempt to decode meaning, journalists often

categorize jazz rap artists in terms of preestablished frames. A muted

trumpet or a walking acoustic bass are recognizable signiers—sonic el-

ements that have become emblematic of jazz, as interpreted by certain

sociohistorically situated interpretive communities. As in earlier jazz al-

bums and concerts that used string sections as a sign of class (e.g., Paul

Whiteman’s symphonic jazz of the 1920s, “concert jazz” made famous

by Duke Ellington, or Charlie Parker with Strings from 1950), acoustic

bass and horns have become a sign of class in rap music.

82

Jazz in the

1980s became associated with the middle class, and its ideological as-

sociations were brought to groups who sampled jazz. Jazz rap became

identied as a counterculture (although the artists themselves do not

use the term), an “alternative” within the rap world, partly dened by

jazz signiers that reinforced preexisting cultural meanings.

As Gary Tomlinson has noted with respect to authentic meaning

in music, “all meanings, authentic or not, arise from the personal ways

in which individuals, performers and audience, incorporate the work

in their own signifying contexts. . . . The authentic meanings of a work

arise from our relating it to an array of things outside itself that we

believe gave it meaning in its original context.”

83

His comments point

to the importance of locating a context for the act of relating musical

codes “to an array of things outside itself,” a crucial component in the

study of musical borrowing and intertextuality of any era, and certainly

applicable to the understanding of jazz rap and the “signifying context”

for various interpretations of the genre.

Jazz codes arising from that context could easily be identied and

distinguished from other rap music sonorities that had largely become

the norm. For example, the sound of an acoustic bass—“Can I Kick It?,”

“Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat),” “Excursions”—is strikingly differ-

ent to that of the funk bass or synthesized bass of many rap styles, for

example, Dr. Dre’s “G-funk” style. And the use of a jazz guitar—“Bonita

Applebum,” “Push It Along,” and “It’s Good to be Here”—is conspicu-

ously opposed to the use of rock or metal guitars for Rick Rubin’s pro-

duction work with the Beastie Boys and Run D.M.C.: the former implies

82

The use of classical idioms and instruments to elevate jazz and African American

culture has a long history, best described in John Howland, Ellington Uptown: Duke Elling-

ton, James P. Johnson, and the Birth of Concert Jazz (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press,

2009). In light of these traditions, it is interesting to note that on a general level, jazz has

a similar function for hip-hop as classical forms had for concert jazz. The current case

may emphasize the African American cultural linkage, whereas the former emphasized

the hybridity between European (white) styles and African American ones.

83

Gary Tomlinson, “Authentic Meaning in Music,” in Authenticity and Early Music,

ed. Nicholas Kenyon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 123.

JM2704_02.indd 457 11/22/10 5:06:19 PM

the journal of musicology

458

a George Benson sound, whereas the latter points more to Eddie van

Halen or Jimi Hendrix. Likewise, a muted trumpet or certain horn

lines may suggest jazz, but in other styles of rap, instrumental horn lines

may be synthesized; more often, drum sounds from funk music will be

sampled with the accompanying horn sounds (e.g., trumpet, trombone,

saxophone) omitted from the sample.

To take the bifurcation of styles a step further: if early 1990s gang-

sta rap suggests a listening space of a car or West Coast block party, then

jazz rap may evoke more bourgeois environments, such as the modern-

day jazz club or a hi- stereo system in one’s living room. Jazz rap im-

plied a more introspective or private experience, to be listened to on

a Walkman as opposed to a dance club (e.g., early 90s pop rap of MC

Hammer or Vanilla Ice).

84

Musical codes can sometimes imply particu-

lar spaces (such as a jazz club), based on a number of factors, includ-

ing cultural and stylistic associations as well as dominant images from

our media-saturated society. If jazz is said to create a certain “vibe” or

“atmosphere,”

85

then this is further proof that jazz, and other musics,

have the ability to imply certain spaces in their recordings. In short,

sounds are situated spatially as well as socially and historically.

86

As Stuart Hall has written, one of the ideological functions of the

media is to distinguish between the center and the periphery—that

is, between the realm of a legitimizing “mainstream” and that of an

“alternative.”

87

But in a subculture, legitimacy is reversed, the center

being understood as inauthentic, whereas the periphery exudes authen-

ticity. Having a niche, perceived to be followed by few, helps to solidify

the subcultural identity of the periphery. For example, bebop, with its

niche authenticity as opposed to swing music, was one particular sub-

culture. The same niche authenticity can be said to exist in folk music,

art lms, so-called indie labels, “alternative” musics, and “conscious” or

“backpack” rappers. In an “age of mass counterculture” (to borrow Ford’s

phrase), the constructions of these subgeneric categories are important

84

Matt Diehl has described East Coast rap as “interior,” for contemplative Walk-

man listening on the subway as opposed to the West Coast automobile-centric listening

of “pop rap.” Matt Diehl, “Pop Rap,” in The Vibe History of Hip Hop, ed. Alan Light (New

York: Three Rivers Press, 1999), 129.

85

For an example of sampling to create atmosphere in Brand Nubian, see Mi-

yakawa, Five Percenter Rap, 111–14.

86

For attention to this third dimension from a geographical perspective, see Edward

Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places (Oxford: Black-

well, 1996).

87

Stuart Hall, “Culture, Media, and the Ideological Effect,” in Mass Communication

and Society, ed. James Curran, Michael Gurevitch, and Janet Woolacott (London: Open

University Press, 1977).

JM2704_02.indd 458 11/22/10 5:06:19 PM

WILLIAMS

459