V

OLUME

16,

I

SSUE

3,

P

AGES

61–82

(2015)

Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society

E-ISSN 2332-886X

Available online at

https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/

Corresponding author: Dr. Jeffrey R. Wilson, Harvard University, One Bow Street, Suite 250, Cambridge, Massachusetts,

02138, USA. Email: jeffreywils[email protected]. Website: http://wilson.fas.harvard.edu.

The Word Criminology:

A Philology and a Definition

Jeffrey R. Wilson

Harvard University

A

B

S

T

R

A

C

T

A

N

D

A

R

T

I

C

L

E

I

N

F

O

R

M

A

T

I

O

N

This essay looks into the past of criminology as a way to think about its future. I take a philological approach to the word

criminology, looking at the etymology and history of that word, to argue for a new definition of the field: Criminology is

the systematic study of crime, criminals, criminal law, criminal justice, and criminalization. I expand and explain this

definition with respect to some common and (I argue) misguided dictates of criminology as it is traditionally understood.

Specifically, I argue that criminology is usually but not necessarily academic and scientific, which means that

criminology can be public and/or humanistic. I arrive at these thoughts by presenting some early English instances of the

word criminology which predate the attempt to theorize a field of criminology in Italy and France in the 1880s, and I

offer some new readings of those Italian and French texts. These philological analyses then come into conversation with

some twentieth-century attempts to define the field and some twenty-first-century innovations in an effort to generate a

definition of criminology that is responsive to the diversity of criminology in both its original formation and its ongoing

transformations. Thus, the virtue of this new understanding of criminology is its inclusiveness: It normalizes unorthodox

criminological research, which opens up new possibilities for jobs and funding in the name of criminology, which holds

the promise of new perspectives on crime, new theories of criminology, and new policies for prevention and treatment.

Article History:

Received 02 February 2015

Received in revised form 01 June 2015

Accepted 10 July 2015

Keywords:

etymology, criminology, philology, criminal justice, criminal anthropology

© 20

15 Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society and The Western Society of Criminology

Hosting by Scholastica. All rights reserved.

Recent collections such as What is Criminology?

(Bosworth & Hoyle, 2011) and What is Criminology

About? (Crewe & Lippens, 2015) suggest a renewed

interest in defining the basis and scope of this field

given the infinite activities carried out in its name.

These collections bring together some of the world’s

leading criminologists to generate a kaleidoscopic

image of the field as it currently stands, but I want to

hazard a new statement of what criminology is by

going in the opposite direction and discussing the

origin and history of the term criminology.

1

In other

words, this is not a criminological study but a

philological study of the word criminology and a

philosophical study of the very idea of criminology.

My aims are not polemical. I am not attempting to

say what criminology should be. My aims are

analytical. I’m attempting to articulate what

criminology is and, from the perspective of

philology, the best way to do so is to look at where

the word came from, to survey what it has been said

to be, to consider what its practitioners have done in

its name, and then to produce a definition that is

abstract enough to be accurate yet specific enough to

be meaningful. Thus, I want to ask, what were the

62 WILSON

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

discourses out of which the word criminology

emerged in the nineteenth century? What was the

context and meaning of the early usage of the term?

What points were writers trying to make when they

first coined this term? And how has the term been

defined and redefined since its popularization in the

twentieth century?

But, it is also necessary to ask, who says our

current definition of the field must be accountable to

the earliest hiccups of the word? Absolutely no one,

but my suggestion is that the early uses of the word

criminology to signify wildly different activities in

wildly different contexts creates the basis for the

more inclusive and more accurate definition of a field

that has become wildly diffuse in recent years. With

the rise of “critical criminology” in the 1970s

(Taylor, Walton, & Young, 1974) and a swelling

number of more recent innovations – including

“radical criminology” (Platt, 1974), “newsmaking

criminology” (Barak, 1988), “peacemaking

criminology” (Pepinsky & Quinney, 1991) “cultural

criminology” (Ferrell & Sanders, 1995), “convict

criminology” (Richards & Ross, 2001), “popular

criminology” (Rafter, 2007), “visual criminology”

(Francis, 2009), “public criminology” (Loader &

Sparks, 2010), and “narrative criminology” (Presser

& Sandberg, 2015) – criminologists have spent much

of the past 40 years discovering new ways to do

criminology, new people to do it, and new goals it

can aim to achieve, effectively challenging the

mainstream twentieth-century tradition of thinking

that criminology must be academic and scientific.

With this recent reformation, criminology can

now be understood as the systematic study of crime,

criminals, criminal law, criminal justice, and

criminalization. While I expand and explain this

definition in my conclusion to this essay, I want to

note upfront that the keyword here is “systematic.”

Criminology is “systematic” as opposed to

“unsystematic,” meaning that it involves

interpretation with a method and affiliation with an

organization, but it is also “systematic” as opposed to

“academic” and “scientific.” The methods of

criminology are often though not necessarily

academic and scientific, which means that (a)

criminology usually comes in the form of

scholarship, but it can also come in the form of essay

and art; (b) criminology may be scientific (drawing

upon fields such as biology, psychology, and

sociology) and/or humanistic (taking cues from

philosophy and history as well as legal, cultural, and

literary studies); and (c) criminology can be either

analytical or ethical—that is, either pure research

concerned with an accurate understanding of crime or

applied research involved in the treatment of

criminals and the prevention of crime. From this

perspective, criminology is not a narrow, limited

discipline of academic research but an umbrella term

for a general field of inquiry, one that includes within

its scope many different sorts. If so, then the above

definition is potentially controversial because of what

it leaves out—gone are the insistences that

criminology is “scientific,” “academic,”

“sociological,” and “modern”—and the virtue of this

new definition is its inclusiveness. It acknowledges

new and unorthodox research in criminology, which

opens up new and unorthodox possibilities for

funding and employment in the name of criminology,

which holds the promise of new theories of crime and

new policies for prevention and treatment.

“The Very Word Criminology”:

The Need for a Philology of Criminology

A philological approach to the word criminology

is required because the different and sometimes

conflicting understandings of this field are reflected

in and are inextricable from the different and

sometimes conflicting accounts of the origin of the

word. In criminological scholarship, wild conjecture

seems to follow whenever someone writes the phrase

“the very word ‘criminology.’” Rock (1994) claimed

that “the very word ‘criminology’ seems to have been

first used in the 1850s and come into more general

usage in the 1890s when the subject began to be

taught in the universities of western Europe, at

Marburg, Bordeaux, Lyons, Naples, Vienna and

Pavia” (p. xvii). Lippens (2009), however, put the

date 20 years later: “The very word ‘criminology’

surfaced during the 1870s” (p. 2). While

contradictory, these claims both have some basis in

reality. According to the Oxford English Dictionary

(OED), the authoritative source on the English

language, the first recorded instance of the word

criminologist came in 1857 (“Criminologist,” 2014),

and the first instance of the word criminology in 1872

(“Criminology,” 2014). Yet Beirne (1993), who has

written our most authoritative account of the term,

insisted that “there is no recorded instance of the term

criminology ever having been used before the final

quarter of the nineteenth century” (p. 233).

This uncertainty about when the word criminology

first appeared is closely bound up with an uncertainty

about who invented it. O’Brian and Yar (2008, p.127)

credited Cesare Lombroso with creating the word,

while Reiner (2012, p. 32) wrote that it was not

Lombroso himself but his followers, and Pond (1999)

said that the first recorded use of this word did not

come from either Lombroso or his followers: “The

very word ‘criminology’ was not coined until 1879

when it was first used by the French anthropologist,

Topinard” (p. 8). Yet Bennett (1988) put the first

THE WORD CRIMINOLOGY 63

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

instance of the word criminology six years later: “The

word ‘criminology’ made its first appearance in

1885” (p. 7). Using this date, Beth (1941) explained

that “the Italian scientist Garofalo … coined the word

‘criminology’ in his work Criminologia (first edition

1885)” (p. 67). For his part, the eminent criminologist

Leon Radzinowicz (2002), founding director of the

Institute of Criminology at the University of

Cambridge, considered both Garofalo and Topinard

in a gripping yet ultimately inconclusive account of

his and his friends’ attempt to trace the origin of the

word:

Who was the first person to use the term?

Baron Raffaele Garofalo—next to Ferri the

most prominent expositor of the Scuola

Positiva—selected Criminology for the title

of his book, which first appeared in 1885….

Yet William Bonger, the Dutch

criminologist, stated that the first scholar to

use the term ‘criminology’ was the

Frenchman P. Topinard, who was not a

criminologist but an anthropologist.

However, Bonger failed to provide a

reference. I turned to Thorsten Sellin in the

hope that with his vast historical knowledge

of criminological thought he might be able

to confirm that Topinard was the first. I

went carefully through Topinard’s published

works, and the only paper I could find in

which he used the term criminology is the

one which he presented to a congress in

1889, four years after the appearance of

Garofalo’s book. At this point, I decided that

it was rather fastidious to attempt to track

down this terminological query. (p. 440–

441)

Here Radzinowicz associated Garofalo with a

biological (as opposed to sociological) approach to

criminology, and Knepper (2001) agreed that “it was

the criminologists working from the perspective of

biological positivism who invented the word

‘criminology,’” stating that “the term [was]

introduced at a criminal anthropology conference in

1889” (p. 64). Like Pond and Radzinowicz, Muncie

(2000) credited the word “criminology” to Topinard,

but not in 1879 (Pond’s year) or 1889 (Radzinowicz

and Knepper’s year): “In 1890 Topinard, writing in

the Athenaum, expressed his dislike for the term

‘criminological anthropology’ to describe the then

fledgling science of crime and criminality. He

reluctantly suggested using the term ‘criminology’

instead, ‘until a better term can be found’” (p. 227).

The Athenaum article that Muncie referred to,

however, was not written by Topinard. It was an

anonymous review of Havelock Ellis’s 1890 book,

The Criminal, and so Jones (2013) wrote that “it was

[Ellis] who, in promoting the ideas of Lombroso,

introduced the word ‘criminology’ into the English

language” (pp. 2–3). Rafter (2011) also credited Ellis

for the English word “criminology,” extending the

point to the Americas: “Britons became familiar with

the term when Havelock Ellis published The

Criminal (1890), his compendium of criminal

anthropology…. Americans learned of it when Arthur

MacDonald published Criminology [in 1893]” (p.

147).

So when did the word criminology become a

word: the 1850s, the 1870s, 1872, 1879, 1885, 1889,

1890, 1893? Where was it invented: England, Italy,

France, the United States? And who should be

credited with coining the term: Lombroso, Topinard,

Garofalo, Ellis, MacDonald, someone else, no one at

all?

In an effort to answer these questions, and to

correct several of the above misconceptions, Table 1

presents all known instances of the word criminology

from 1850–1890. I also want to note that, just as

there is no consensus on the origin of the word

criminology, there is no consensus on the nature of

the discipline signified by that word, as Rafter herself

discussed in her article “Criminal Anthropology in

the United States” (1992). In her essay, Rafter

showed that the debates which occurred during the

formation of criminology as a coherent discipline in

the United States—Is it an autonomous field? What is

its methodological orientation? Is it about knowledge

production or crime control?—continue to inform

our discussions of what criminology is and what it

does, an idea argued earlier by Jeffery (1959). In the

analysis of the original European discourse that

follows, I explore and expand upon this idea, taking

as my point of departure the notion that the multiple

and sometimes conflicting definitions of the word

criminology symbolize, follow from, and lead to

comparably conflicting understandings of the field of

criminology.

64 WILSON

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

Table 1: The Word Criminology, 1850-1890

Date Word Language Country Author Text

March 21,

1857

“criminologist

”

English England John Ormsby “Felons and Felon-Worship”

1860 “criminology” English England Joseph Ewart The Sanitary Condition and Discipline

of Indian Jails

April 3,

1872

“criminology” English United States H.T. “France”

1881 “criminology” English United States Andover

Theological

Seminary

Catalogue of the Officers and Students

1884 “criminologia” Italian Italy S.P.G.

Mazzarese

Quoted in Annali di Statistica [Annals of

Statistics] (Nov.-Dec., 1885).

1885 “criminologia” Italian Italy Raffaele

Garofalo

Criminologia: Studio Sul Delitto, Sulle

Sue Cause e Sui Mezzi di Repressione

[Criminology: The Study of Crime, its

Causes, and the Means of Repression]

December

5, 1885

“criminologia” Italian Italy L. Majno “La Scuola Positive di Diritto Penale”

[The Positive School of Criminal Law]

1886 “criminologia” Italian Italy Emanuele

Carnevale

Della Pena nella Scuola Classica e nella

Criminologia Positiva [On Punishment

in the Classical School and in Positive

Criminology]

1886 “criminologia” Italian Italy Guilio

Fioretti

Su la Legittima Difesa, Studio di

Criminologia [On Self-Defense, a Study

of Criminology]

1887 “criminalogie” French France Paul

Topinard

“L’Anthropologie Criminelle” [The

Criminal Anthropology]

1888 “criminologie” French France Gabriel Tarde “La Criminologie” [The Criminology]

June 18-20,

1889

“criminology” English United States Committee

on Prison

Reform

“Prison Reform”

August

1889

(published

1890)

“criminologie” French France Paul

Topinard

“Criminologie et Anthropologie”

[Criminology and Anthropology]

August

1889

(published

1890)

“crimnologie” French France Romeo

Taverni and

Valentin

Magnan

“De l'Enfance des Criminels dans ses

Rapports avec la Prédisposition

Naturelle au Crime” [A Criminal’s

Childhood in Relation to their Natural

Predisposition to Crime]

January

1890

“criminology” English United States Arthur

MacDonald

“Criminological”

1890 “criminology” English England Havelock

Ellis

The Criminal

August 30,

1890

“criminology” English England Anonymous “Criminal Literature”

September

6, 1890

“criminology” English England Anonymous Review of Havelock Ellis’s The

Criminal in Athenæum

THE WORD CRIMINOLOGY 65

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

The First Uses of the Word Criminology in

Nineteenth-Century English Literature

2

According to the OED, the first recorded instance

of the word criminology came in an article titled

“France” (signed only with the author’s initials,

“H.T.”) in the Boston Daily Advertiser on April 3,

1872, which drew attention to the newness of the

word by putting the neologism in quotation marks:

“The law school affords … lectures … on what the

French call ‘criminology,’ or the science of penal

legislation” (“Criminology,” 2014). Here

criminology is associated with France and Europe

more generally and, with this quote coming from a

Boston paper, it would seem that the United States

(not England) was the earliest home to criminology

in the English language. In this advertisement,

criminology is described as a science and is

associated with an academic institution, specifically

the law school at the College of France, and it is said

to be the study of criminal law. As such, this

quotation epitomizes our conventional image of early

criminology as continental, academic, and scientific

(see Becker & Wetzell, 2006; Gibson, 2002; Horn,

2003; Pick, 1993; Wetzell, 2000), but this image can

be qualified by looking at some English instances of

the word criminology that predate the OED’s first

recorded use. As I demonstrate in this section, the

first uses of the word criminology came in English,

not Italian or French, and those early instances

referred to loosely essayistic popular literature, not

rigorously scientific academic research.

As noted, the first instance of the word

criminology was predated by the first instance of the

word criminologist, which came in an anonymously

written book review entitled “Felons and Felon-

Worship” published in 1857 in The Saturday Review,

a London weekly newspaper. Beirne (1993)

identified the author of this review as “almost

certainly John Ormsby” (p. 236), an English travel

writer and translator, an attribution I follow here.

Ormsby’s review attended to the growing number of

mid-nineteenth-century English writers who found

crime fascinating and devoted themselves to

representations of and reflections on criminals. The

first sentence of Ormsby’s review suggested that this

new trend of “felon worship” was an outgrowth of

“what, for want of a better title, we may call the

Newgate Press” (p. 270). He was referring to a

literary fad in England that began with the immensely

popular posters and pamphlets sold at fairs and public

executions in London in the late eighteenth century,

sheets that were dubbed The Newgate Calendar.

Taking its name from London’s Newgate Prison,

where criminals were held for trial and (often)

execution, The Newgate Calendar was comprised of

heavily moralistic and highly formulaic criminal

biographies written initially by jailers and later by

lawyers who recounted the lives, crimes, confessions,

repentances, and executions of the criminals in the

prison (see Worthington, 2005). Enticing readers

with the sordid details of the criminal life, these

stories also admonished readers through their

representation of crime’s inevitable punishment and

the criminal’s inevitable regret. The tales were first

collected and published in book-form as The Newgate

Calendar in 1773 and were then revised and reissued

in many editions into the nineteenth century,

spawning an early nineteenth-century genre of crime

fiction called “the Newgate novel” (see

Hollingsworth, 1963), including examples such as

Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1837-1839).

Ormsby’s review addressed three samplings of

“the Newgate Press” from 1857. The first was titled

Scenes from the Lives of Robson and Redpath (1857),

written by an author who went only by his initials,

J.B. This book followed the Newgate tradition,

narrating and analyzing the misdeeds and

punishments of two criminals, William James

Robson (a playwright and criminal) and Leopold

Redpath (a criminal and philanthropist), for the

purpose of deterring readers from a life of crime. In

fact, the very first sentence of J.B.’s preface to

Scenes articulated the criminological theory of

deterrence fairly clearly: “Punishments were

instituted and are preserved by society for their

deterring effect upon the community, rather than

from a display of vengeance towards the criminal

who violates its laws.” Famously, Cesare Beccaria

(1764/1995) argued this theory of deterrence in his

treatise On Crimes and Punishments, which many

criminologists cite as the first text in “the classical

school” of criminology (e.g., Cullen & Agnew,

2013). In this regard, J.B. would belong to Beccaria’s

classical school, the major difference being that J.B.

was actually called a “criminologist” by one of his

contemporaries, as discussed below, while Beccaria

was not.

The second text covered in Ormsby’s review was

the Lamentation of Leopold Redpath (1857), an

anonymous poem about one of the criminals

discussed by J.B., but this time written from the

perspective of the criminal, who fancied himself a

Robin Hood, robbing the rich to feed the poor. This

poem was overtly sympathetic, turning a criminal

into a tragic hero, as evident in this excerpt which

Ormsby quoted:

Alas! I am convicted, there a no one to

blame

I suppose you all know Leopold Redpath is

my name;

66 WILSON

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

I have one consolation, perhaps I’ve more,

All the days of my life I ne’er injured the

poor. (p. 271)

Ventriloquizing the criminal, sympathetically

imagining his moral and mental progress, the

Lamentation is arguably an anticipation of the

“convict criminology” of Richards and Ross (2001)

or the “narrative criminology” of Presser and

Sandberg (2015). Moreover, this text, and the

Newgate tradition more generally, could contain the

germ of an “artistic criminology,” one which uses the

media of imaginative expression—from poems,

plays, and novels to paintings, photographs, films,

and other performance arts—to study crime and

criminals, and also one which mobilizes

criminological theories to unpack the artistic

creations of writers ranging from Homer and

Shakespeare to Dickens and Spike Lee—all

criminologists of a sort who, like the author of the

Lamentation, chose to present their theoretical

reflections on crime and criminals through artistic as

opposed to scholarly writing, producing what Rafter

(2007) has called “popular criminology.” In short, if

Scenes from the Lives of Robson and Redpath pointed

backward to Beccaria and the criminology of the

eighteenth century, the Lamentation of Leopold

Redpath pointed forward to some of today’s

emergent criminologies.

But is it prudent to call these works of

“criminology”? Ormsby thought so. Having

considered “a philosopher” and “a poet” (p. 271), he

then turned to the author of a third book, titled Dark

Deeds, and dubbed him a “criminologist” in the first

recorded instance of that term:

In the author of Dark Deeds we have a

criminologist of a third sort. J B. had proved

that theatricals, casinos, literature, peas out

of season, presentations at Court, and

extravagance generally, whether in notions

or expenditure, all lead to felony. The poet

had shown that benevolence and dishonesty

may co-exist in the same individual. The

purpose of the writer now before us is “to

show the short-lived success of crime by

examples carefully selected from the career

of those who have planned, and sinned, and

suffered.” (p. 271)

Before turning to Dark Deeds, I want to note that

Ormsby’s phrasing here (“a criminologist of a third

sort”) is fascinating because it conceives of all three

writers – one a philosopher, one a poet, and one an

essayist—as “criminologist[s].” Moreover, Ormsby

allowed for different “sorts” of criminologists. This is

the quality of criminology—diverse, not only in

content and method, but indeed in medium, allowing

for different manifestations in different forms of

expression ranging from expository prose to

imaginative poetry—that I am striving to capture in

my definition of the field. Indeed, that diversity in

content, method, and medium is precisely what we

see in in something like the Art/Crime Archive

(www.artcrimearchive.org) and in the concerns of

“cultural criminology” (Ferrell & Sanders, 1995),

which treats art and film as both an object of study

and as criminological commentary itself.

3

While published anonymously, Dark Deeds

(1857) announced in its subtitle that it was written By

the Author of ‘The Gaol Chaplain,’ a Cambridge-

educated clergyman named Erskine Neale. In the

introduction to Dark Deeds—which was lifted

wholesale from Neale’s earlier book Scenes Where

the Tempter has Triumphed (1849)—the author

looked at crime and asked what “father[s] the

offense” (p. iii). With his interest in the “fans et origo

malorum” (p. iv), “the source and origin of evil,”

Neale was, like many modern criminologists,

interested in criminogenesis, or crime causation. He

presented two causes of crime—“impunity” (p. iii)

and “vice … represented in the ascendant” (p. iv)—

the first a psychological theory of criminology

concerned with the mental transactions that result in

criminal actions, the second a sociological theory

addressing the relationship between literature and

crime. For the latter point, Neale argued that literary

representations of unpunished villainy both embolden

the criminal and misrepresent the world because

crime is always punished by the “Invisible Avenger,”

namely God (p. v). We can (and many of us would)

debate Neale’s conclusion that “that there is no such

thing as successful villany” (p. v), but what is beyond

debate is that—like the other entries in the Newgate

tradition—his argument was systematic, rigorous,

organized, and methodical. The method was not

scientific, and the data were not quantitative. Instead,

Dark Deeds consisted of a series of vignettes or

character portraits of criminals that Neale

encountered, interviewed, and studied. The 18

chapters of Dark Deeds range from five to 20 pages

of absolutely gripping narrative and deep (if often

theologically dogmatic) analysis, including titles such

as “Perverted Talent—Mathieson the Engraver,”

“The Female Assassin—Miss Ann Broadrick,” and

“The Gaming House an Ante-Room to the Gallows—

Henry Weston.” Reading these chapters feels exactly

like reading, say, the “cultural criminology” of Jeff

Ferrell (1997), whose approach to fieldwork,

theorized as “criminological verstehen,” attempts to

unravel the lived meanings of crime and justice by

attending to the subjective experiences and emotions

THE WORD CRIMINOLOGY 67

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

of an embedded researcher. Likewise, Neale’s Dark

Deeds consisted of “fieldwork” conducted by an

analyst immersed in the object of his study and using

a formal system or method of interrogation, one that

allowed him to gather, evaluate, and display

information with a relatively high degree of

consistency and rigor.

The three books covered in Ormsby’s “Felons and

Felon-Worship” represent a coherent body of

literature for a burgeoning field, a field pointing back

to the Newgate tradition, a field I would call

“criminology.” This field began with literary and

ethical accounts of crime and criminals written by the

public and the practitioners of criminal justice—

jailers and lawyers, not scholars, certainly not

scientists. If so, then the Newgate tradition has a

significant and previously overlooked role in the

disciplinary history of criminology. Although

criminology, both the word and the discipline, is

usually thought to have originated in Italy in the

1880s, there were instances of the word criminology,

and I would argue a field of criminology, in England

well before that time. To understand the Newgate

tradition as “criminology” is to suggest that, in its

inception—as in our current moment—criminology

could and does take the shape of humanistic,

essayistic writing done by criminal justice

professionals. Moreover, the moralistic tone and

purpose of the Newgate tradition reveals that

criminology began as “applied research” concerned

with the prevention of crime, not “pure research”

addressed solely to the understanding of crime. Some

criminologists may want to preserve the moniker of

criminology for pure, scientific research conducted

by academics, but the first instance of the word

criminology gestures toward a branch of the field that

is humanistic, popular, and practical, something that

might be called “public criminology” following

Loader and Sparks (2010). These very old and very

new instances of “public criminology” suggest that

criminology, then and now, need not be nervously

restricted to academic and scientific writing.

Given this broad and inclusive understanding of

criminology, it becomes necessary to ask what makes

something not criminology. In all its “sorts,” the

criminologist can be distinguished from the amateur,

as Ormsby did when he concluded that there are

“three great classes of felon-worshippers” (p. 272).

First, there are those who perversely love deviance

and wickedness. Second, there are those who only

obsess over criminals because everyone else is doing

so. But then Ormsby turned to a third class of “felon

worshipers” who anticipate what we now tend to

think of as criminologists:

Thirdly, we have those of the George

Selwyn stamp, for whom a criminal has a

sort of unhallowed fascination. They take a

deep interest in all he says and does, or has

said and done – they have an unquenchable

thirst for information as to whether his

health holds up, what he had for breakfast

the last morning, whether he takes kindly to

the crank, the colour of his hair and eyes, his

height, his habits, his disposition. They are

not to be confounded with the first class; for

they would not rescind one jot or tittle of his

sentence, or ameliorate his condition for any

consideration. The more you punish him, the

better pleased they are – only you must let

them know all the particulars. (p. 272)

In these three classes of “felon worshippers,” we

might distinguish criminophiles—those who love,

celebrate, and sentimentalize criminals—from

criminologists such as George Selwyn – those who

study criminals with an “unhallowed fascination.”

4

The criminologist is no less enthusiastic and

obsessive than the criminophile, but the criminologist

is interested in interpretation, not celebration. From

this perspective, it is an unsentimental interest, an

attempt at elucidation, and an attention to

particularity that distinguishes the criminologist who

studies crime from the amateur who is simply

fascinated by it.

Three years after “Felons and Felon-Worship,” the

word criminology appeared again in a book by

Joseph Ewart, M.D. entitled The Sanitary Condition

and Discipline of Indian Jails (1860). While Ewart’s

book is notable as an early, unrecorded instance of

the word criminology, it is also remarkable for its

articulations of actual criminological theories. In one

passage, Ewart used what we would now call a

“social learning theory” of criminology to describe

prison as a school for scoundrels, as “a course of

infamous training, under the ascendant reign of some

irreclaimable villain, who occupies the professorship

of criminology in this collegiate institution for the

reciprocal and universal dissemination of the blackest

vice and crime” (pp. 288–289). I do not want to take

this instance too seriously because clearly Ewart used

the word criminology ironically—meaning, as he did,

that criminology is the study of how to do crime—but

it is still noteworthy that in 1860 a British physician

writing about India used the word criminology 12

years before the OED’s first recorded usage.

Moreover, it is interesting to consider the fact that, in

this early instance, criminology was something that

was done by the criminal himself, suggesting another

early example of “convict criminology” (Richards &

Ross, 2001).

68 WILSON

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

As Neale’s Dark Deeds, J.B.’s Scenes, the

anonymous Lamentation, and Ewart’s Indian Jails

demonstrate, theories that now occupy a central place

in our current conversations about criminology were

present long before the scientific study of crime and

criminals became fashionable. If these texts included

the word criminology, and recognizable theories of

criminology, then what prevents us from calling them

properly criminological? Is it simply the absence of

science and statistics? That threshold will not suffice,

for the field of criminology was first theorized in

contrast to the science and statistics of criminal

anthropology, as I discuss in the next section.

In this section, I have addressed a couple of early

English instances of the word criminology which, to

be sure, were sporadic. They were not as clear and

deliberate as the explicit attempts to define the field

of criminology that began later in the nineteenth

century in Italy and France. But the earliest usage of

the word criminology in the context of the Newgate

tradition and other popular nineteenth-century

English writings on crime and prisons opens up for us

the possibility that humanistic, essayistic, and even

artistic statements on crime can be considered

criminology, then and now. From this perspective,

both ancient and modern essays, poems, plays, films,

and so forth can rightly be called criminological, as

can scholarship coming from the humanities, as long

as such works are sufficiently systematic, a position

that stakes its ground against the narcissistic claim

that the only statements on crime worthy of

validation as criminology are those using the

scientific method and coming from within the

hallowed walls of the university.

The First Uses of the Word Criminology

in Late Nineteenth-Century

Italian and French Literature

For the sake of clarity, and to correct some

common misconceptions, I’ll start this section by

saying that (a) someone named Mazzarese (not

Raffaele Garofalo, certainly not Cesare Lombroso)

was the first person to use the term criminology in

Italian, (b) Gabriel Tarde (not Paul Topinard) was the

first to use it in French, and (c) a group of New

England clergymen (not the American Arthur

MacDonald or the British Havelock Ellis) was the

first to use it in English to refer to a specific and

coherent discipline, although there were some earlier,

erratic instances of the word in English, as discussed

in the last section. In contrast to and independent of

its earlier usage in English, the word criminology was

first used in Italian and French as part of an effort to

theorize and name a specific academic pursuit,

although it was not always the same pursuit that

people had in mind when they said the word

criminology. In Italy and France, the word was used

to refer to both the established field of criminal

anthropology and an emerging field that was

positioned as an alternative to criminal anthropology,

a field more sociological in method and more

political in aim. Thus, from a philological

perspective, we can ask, did criminal anthropology

die out as a practice and get replaced by a different,

better practice called criminology? Or was the

practice of criminal anthropology simply renamed

criminology? Is criminal anthropology a kind of

criminology, or are criminal anthropology and

criminology different, even opposed approaches to

the question of crime?

5

Criminal Anthropology and Criminology in Italy

According to Google Books’s Ngram Viewer (see

Figures 1 and 2), the term criminal anthropology

came into usage first in Italy in the late 1870s and

then in France in the early 1880s, in both cases

predating the term criminology, and criminal

anthropology remained the more popular term well

into the twentieth century. In Italy, Cesare Lombroso

described his approach to criminals as

“anthropological” as early as the first edition of his

landmark book, Criminal Man (1876/2006, p. 92).

The tenets of Lombrosian criminal anthropology are

well known: crime is a natural phenomenon; there are

“born criminals” whose predisposition to crime can

be ascertained from their physical “anomalies”; thus,

scholars should study the criminal, not the crime (see

Horn, 2003). After publishing Criminal Man,

Lombroso regularly used the term criminal

anthropology to describe his intellectual project: He

founded a journal called Archives of Psychiatry,

Criminal Anthropology, and Legal Medicine in 1880,

for example, and he convened the first International

Congress of Criminal Anthropology in 1885. But, up

to this point in his career, he never referred to himself

as a criminologist or to his work as criminology.

Our most authoritative resource, The Grand

Dictionary of the Italian Language, cites Raffaele

Garofalo’s book titled Criminology (1885) as the first

instance of the word in Italian (“Criminologia,”

1961-2008), but there was at least one earlier

instance. A journal article published in 1885 by the

Commission on Judicial Statistics and Notaries

quoted from a book published in 1884 by one S. P. G.

Mazzarese, who wrote, “Now the social criminology

could reaffirm the great influence that physical and

moral elements have on human nature while also

taking into consideration constitution and character”

THE WORD CRIMINOLOGY 69

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

(as cited in p. 231). In this quotation, it is unclear

who the criminologists are. When he said the word

criminology, was Mazzarese referring to the works of

criminal anthropologists like Lombroso and claiming

that they consider both the natural and the social

influences on crime? Or, was Mazzarese referring to

a new field that saw crime as both a natural and a

social phenomenon, unlike Lombroso and the other

criminal anthropologists, who only saw crime as a

natural phenomenon? Because I have been unable to

track down the reference, it is difficult to tell. From

this quotation alone, we cannot know if Mazzarese

thought of criminal anthropology as criminology, but

we can be sure that Mazzarese thought of

criminology as a discipline treating crime as both a

natural and a social phenomenon. In this regard,

criminology has always been an interdisciplinary

field. It was never not sociological, and the

introduction of sociology to biological considerations

is what makes thought on crime “criminology.”

After the first recorded Italian usage by

Mazzarese, the word criminology appeared in the title

but not the text of three Italian books: Raffaele

Garofalo’s Criminology: A Study on Crime, its

Causes, and the Means of Repression (1885);

Emanuele Carnevale’s On Punishment in the

Classical School and in Positive Criminology (1886);

and Giulio Fioretti’s On Self Defense, a Study of

Criminology (1886). Of these three books, Garofalo’s

was by far the most influential. He was one of the

fathers of criminal anthropology, along with

Lombroso and Fiori, whom Garofalo dubbed “the

naturalists,” but like Mazzarese, Garofalo conceived

of criminology as both a natural and a social science,

as he stated in the opening of his book Criminology:

The criminal has been recently studied by

the naturalists, some of whom note his

anatomical and psychological aspects; he

has been presented as a type, as a variety of

the genus homo. But these studies are sterile

when applied to legislation. Not all of the

great number of criminals according to the

law answers the description of the

naturalists’ criminal man, which has thrown

doubt upon the practical value of such

studies. And yet this does not stem from an

error of method. The naturalists, while

speaking of the criminal, have omitted to tell

us what they meant by ‘crime.’ They have

left this task to the jurists, whom they

believed to be responsible, without

attempting to say whether or not criminality

from the legal standpoint is coterminous

with criminality from the sociologic point of

view. It is this lack of definition which has

hitherto rendered the naturalists’ study of

crime a thing apart and caused it to be

regarded as a matter of purely scientific

interest with which the science of criminal

law has nothing to do. (pp. 3–4)

If criminology was clearly a social science for

Garofalo, it was also an applied science, not the pure

science of “the naturalists.” That is, criminology was

not Garofalo’s term for what the criminal

anthropologists had been doing. Instead, he said that

the scientific methods of the naturalists needed to be

applied to legislation, and this application of

academic thought to public policy was what he

thought of as “criminology.” For the criminal

anthropologists, the central disciplinary distinction

was between the earlier, “classical school” and their

own, more modern, “positive school”; the key

distinction for Garofalo, however, was between “the

legal viewpoint” and “the sociological viewpoint.”

That is, where Mazzarese presented criminology as

an interdiscipline combining the methods and

concerns of biology and sociology, Garofalo added

legal studies to the mix. He did not take exception to

the scientific methods of “the naturalists.” Instead, he

lamented the fact that the criminal anthropologists

had not been sufficiently deliberate in their definition

of crime; they simply assumed that lawmakers had

arrived at the correct definition. Taking a step back,

we can see that, while the “critical criminology” of

the 1970s positioned itself against the legalism of

mainstream twentieth-century criminology (see

Taylor et al., 1974), the example of Garofalo shows

that criminology has always had the capacity to be

critical of legal definitions of crime. And, if Garofalo

was critical of the criminal anthropologists in the

academic sphere for not defining crime, he was also

skeptical of the politicians and lawyers in the public

sphere who actually were defining crime. That is,

Garofalo was suspicious of both “the naturalists” and

“the jurists,” creating a space for “criminologists” to

consider what a criminal is (a biological concern) by

considering what crime is (a sociological concern). In

sum, he thought criminology should be sociological,

not just biological; practical, not just theoretical;

public, not just academic; political, not just scientific;

and critical, not just legalistic. From this perspective,

Lombroso was not a criminologist.

As noted, Garofalo, Carnevale, and Fioretti all

used the word criminology in their titles, but not in

their texts, nor did they use the term criminologist. In

their texts, they did use the term criminalist, but this

appellation was not reserved strictly for Lombroso

and Ferri. For example, while Fioretti (1886) referred

to “the positive criminalist [il criminalista positivo]”

(p. 92), Carnevale (1886) used the term to discuss

70 W

ILSON

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

“the classical criminalists [i criminalisti classici]” (p.

16). Looking at Garofalo, Carnevale, and Fioretti we

must question whether the term criminology used in

their titles is what is done by the “criminalists”

discussed in their texts. Is a “criminalist” the same as

a “criminologist”? Is a “criminalist” a certain kind of

“criminologist”? Or is a “criminalist” specifically not

a “criminologist”? This terminological instability was

a hallmark of the discourse about crime in Italy in the

1880s, an inconsistency that followed the discourse

to France.

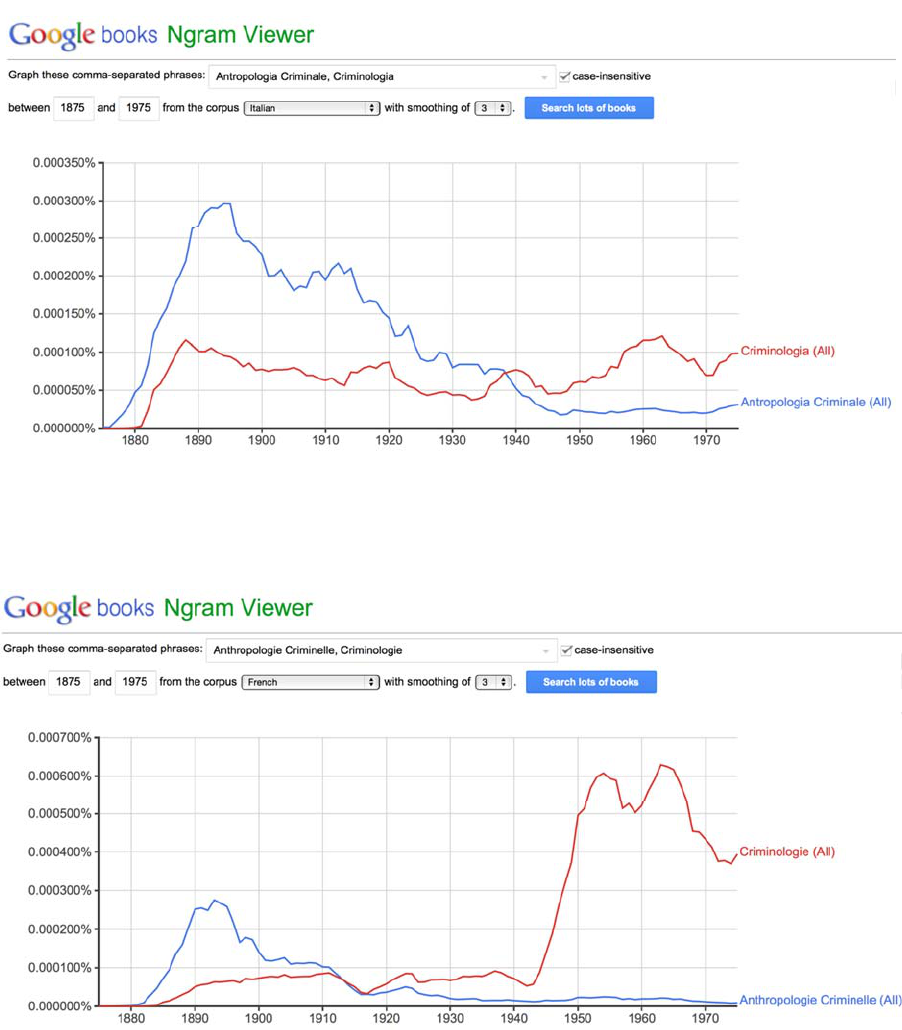

Figure 1: A Google Ngram

6

of the Frequency of the Words

Criminal Anthropology and Criminology in Italian from 1875-1975

Figure 2: A Google Ngram of the Frequency of the Words

Criminal Anthropology and Criminology in French from 1875-1975

THE WORD CRIMINOLOGY 71

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

Criminalogy and Criminology in France

If Garofalo was the first person to theorize the

discipline of criminology, and he did so in Italian in

1885, the first person to theorize the word

criminology as a term for the discipline was Paul

Topinard, writing in French first in 1887 and again in

1890. First, in an 1887 article titled “Criminal

Anthropology,” published in the Review of

Anthropology, Topinard discussed Lombroso’s

Criminal Man and suggested a different title: “Its

title, Criminal Man, perfectly reflects its contents: it

could just as well be entitled ‘Criminalogy’ except

for the fact that practical applications, professional

jurisprudence, the question of prevention and

punishment, are not covered in the book” (p. 659).

Note that Topinard’s term here was criminalogy with

an a, not criminology with an o, suggesting (per the

method of Lombardo and the criminal

anthropologists) the biological study of criminals or

criminality, not the sociological study of crime. But,

as Topinard treated the term, criminalogy was not

what Lombroso had been doing. Topinard said that

Lombroso’s work could be called criminalogy except

that, as Topinard saw it, Lombroso was theoretical,

academic, and scientific while Topinard’s

“criminalogist” would be practical, public, and

political. For Topinard, criminalogy is applied

research, whereas Lombroso and the criminal

anthropologists had been doing pure research.

Furthermore, the criminal anthropologists studied the

criminal as an animal, not crime as an event, but

Topinard had serious reservations about both their

methods and their theories, as he stated in the

conclusion of his review:

To accept as true the concept of atavism—

i.e., that certain individuals are predestined

to commit crime or that they possess a

physical and mental constitution which leads

to crime—would be to undermine at its

foundation the new branch of applied

science which has been developed under the

name of criminalogy. (p. 684)

The Lombrosan idea of the born criminal would

undermine Topinard’s vision of “criminalogy” (again

with an a) because criminalogy is an “applied

science”: It attends to prevention and punishment,

which are fool’s errands if crime is predetermined. In

sum, like Garofalo’s criminology, Topinard’s

criminalogy was conceived of as public, practical,

and political, concerned with the prevention of crime

and the punishment of criminals, not simply an

academic understanding of the causes of crime

arrived at through the scientific method, which had

been the narrow concern of criminal anthropology up

to that point.

In the following year, Topinard’s countryman and

colleague Gabriel Tarde (1888) wrote a blistering

critique of Garofalo in a paper titled “The

Criminology,” also published in the Review of

Anthropology. That is, Tarde, not Topinard, was the

first Frenchman to use the term criminology with all

the right vowels, although he only used the term in

his title and to name Garofalo’s book. In his article,

Tarde did not reflect on the term criminology but,

like Topinard, whom he cited, Tarde thought that

“the expression criminal anthropology is not immune

to serious criticism; criminal psychology would be

clearer” (p. 522). If Tarde thought criminal

psychology was a better pursuit than criminal

anthropology, we might pause to ask which of these

is actually criminology. Is criminal psychology a kind

of criminology, while criminal anthropology is not?

Or, are both criminologies, except that (from Tarde’s

perspective) criminal psychology is good

criminology, while criminal anthropology is bad? In

any event, keeping in mind our main concern, which

is the definition of criminology, we must remember

to produce a definition that is responsive to the

possibility that criminology is not necessarily a good

thing. Indeed, back in Italy in 1885, Luigi Majno had

already reported denigrations of the “scientific cult”

of Lombroso, whose studies were said to “fly by

alchemical calculations and metaphorical

criminology” (p. 1162). We must remember that the

word criminology can be a pejorative term, not the

title of a noble science, but a denigration of a naïve

scientism, as it has been in more recent studies such

as Stanley Cohen’s Against Criminology (1988) or

Carol Smart’s (1990) account of abandoning

criminology.

In 1889, at the second International Congress of

Criminal Anthropology, Biology, and Sociology,

Topinard gave a paper titled “Criminology and

Anthropology” in which he modified his earlier term

criminalogy with an a to the term Tarde had used,

criminology with an o. Imagining himself in

conversation with a criminologist, Topinard argued

that criminology is not anthropology because

criminology is practical while anthropology is purely

academic:

Nothing of what you are handling has to do

with anthropology; the science that you have

created and the growing number of criminals

that has made it so urgent, must not bear this

name, and the title of criminology is the

only one that suits it. (p. 489)

72 WILSON

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

For Topinard, criminology was a science but, he

insisted, it was an applied science, not a pure science

like anthropology. For Topinard, anthropology was

theoretical but criminology was practical, as he

concluded:

Criminology is a science of application and

not a pure science like anthropology.

Criminology does not concern itself with the

human that is animal, but solely with the

human as a social being. Criminology fits

into forensic medicine as well as ordinary

medicine, on one hand in sociology and in

its applications on the other. Criminology

has nothing to do with true anthropology. (p.

496)

For Topinard, criminology was not the study of the

criminal as a biological life form, which is perhaps

why he changed his earlier term criminalogy with an

a, which suggests the study of criminals, to

criminology with an o. Criminalogy with an a is a

biological discipline concerned with the criminal as a

natural phenomenon while criminology with an o is a

sociological discipline attending to crime as a social

phenomenon. For Topinard, there was no

criminology without sociology—criminology was

criminal anthropology plus sociology plus politics—

yet he thought that criminology had amassed enough

autonomy to be its own field:

While the title of criminology belongs to

you in its entirety, you are independent. You

contribute to your goals in all the sciences

by taking what suits you. You are

autonomous. Believe me, Messieurs, be

proud of yourselves. Display your real flag.

Surely, the legitimate title of your science is

that which M. Garofalo gave it, that of

criminology. (p. 496)

Criminal Anthropology as Criminology in Italy,

France, Great Britain, and the United States

Although Garofalo and Topinard used the word

criminology to distance themselves from the

discipline of criminal anthropology, others at the time

were using the word criminology as a synonym for

the phrase criminal anthropology. This was

especially true of the translation of criminal

anthropology into English, which first surfaced in

June of 1889 (remarkably, two months before the

second International Congress of Criminal

Anthropology, Biology, and Sociology) in a panel on

prison reform at a conference for congressional

churches in Boston, MA: “We shall treat this subject

in its relation to criminology more than its relation to

penology. As Christians we can wisely join hands

with the social scientist in studying the criminal more

than his crime” (p. 36). The Anglicization of

criminology was then more deliberately taken up by

the American Arthur MacDonald in a review essay

titled “Criminological” published in January of 1890

in The American Journal of Psychology.

7

Macdonald

used criminology and criminal anthropology

interchangeably and registered the diversity of the

emergent field by noting two main “parties”—“one

emphasizes the pathological or atavistic causes; the

other, the psychological and sociological” —and a

whole host of “divisions” such as criminal anatomy,

criminal jurisprudence, penology, prophilaxy

(“methods of prevention”), and “the philosophy of

criminology” (p. 115). Like MacDonald’s essay, an

anonymous English review titled “Criminal

Literature,” published in 1890 in The Saturday

Review, did not distinguish between “what is

variously called criminology or criminal

anthropology” (p. 265). Also like Macdonald, this

piece in The Saturday Review divided criminology

into two broad parts, although the parts were not the

same. The author of “Criminal Literature” saw “one

[part] which is sensible, which is not particularly

scientific, and which is as old as the hills [and] one

which is brand-new, which is scientific quand meme,

and which is chiefly nonsense” (p. 265). Macdonald

had separated a biological school from a psycho-

sociological school, but this anonymous English

writer drew a distinction between a criminology that

is scientific and one that is not. The English writer’s

suggestion that this last kind of criminology, the non-

scientific kind, is “as old as the hills” encourages us

to think that, at least from this writer’s perspective,

criminology is not necessarily scientific and not

necessarily modern. As we work toward our

definition, we must remember that criminology can

be ancient or modern, humanistic or scientific, and,

when scientific, biological or psychological or

sociological. And it can also be, as this writer said,

“nonsense.”

In the five short years between Garofalo’s Italian

usage of the term and the translation of the discourse

to a wider Western audience, there emerged a

proliferating number of orientations that criminology

could take and still be considered criminology. Just

consider the anonymous English review of Havelock

Ellis’s The Criminal published in the Athenæum

(1890) which described criminology as a “branch of

the anthropological sciences,” but “share[d] Dr.

Topinard’s dislike of the term ‘criminal

anthropology,’ and may adopt the term ‘criminology’

till a better can be found” (p. 325). Even though

Topinard specifically dissociated criminology from

THE WORD CRIMINOLOGY 73

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

anthropology because he thought criminology was

practical but anthropology was not, this review cited

Topinard in its claim that criminology is a discipline

within the field of anthropology, even as it rejected

the moniker “criminal anthropology.” What a mess!

As this reference to Topinard suggests, the

uncertainty about which term to use, criminal

anthropology or criminology, was prevalent even

back in France. In one paper delivered at The Second

International Congress of Criminal Anthropology,

Biology, and Sociology, two Frenchmen Taverni and

Magnan (1890) explicitly attached the word

criminology to the battle cry of criminal

anthropology: “To study the criminal rather than the

crime is the true spirit of modern criminology” (p.

49). And even in the earliest Italian writings,

Carnevale and Fioretti (both writing in 1886) clearly

used the term criminology to refer to the positive

school of criminal anthropology, yet it was not

necessarily a ringing endorsement. Neither Carnevale

nor Fioretti produced works of Lombrosan

anthropology. Carnevale explicitly sought to merge

the findings of the newer positive school with the

thinking of the older classical school. Fioretti married

the scientific scholarship of the positive school with

the humanistic scholarship of history. Both Carnevale

and Fioretti’s works read more like moral philosophy

than criminal anthropology, which brings us back to

the question that is the main concern of this essay:

What is criminology?

What would a definition of the field of

criminology look like if were made accountable to

the wide variety of activities carried out in the name

of criminology in its original formulation? From the

first to use the term in Italian, Mazzarese, we would

take that criminology can approach crime as either a

natural or a social phenomenon. From the first to use

the term in a major way, Garofalo, we would say that

criminology is practical and political. From the first

to theorize the term explicitly, Topinard, we would

add that criminology is autonomous in its

interdisciplinarity. And from the other writers of the

time—the Italians Majno, Carnevale, and Fioretti as

well as the Frenchman Tarde, the American

MacDonald, and the anonymous British reviewers—

we would gather that criminology could also be

another name for criminal anthropology, a name that

could be used either as grandiloquence or as a

pejorative. Thus, if we want a definition of the term

criminology that is responsive to it earliest usages, we

must provide one that allows for both the methods

and theories of the criminal anthropologists and the

critique and rejection of those very methods and

theories.

“Criminology is…”:

Twentieth and Twenty-First Century

Definitions and Debates

In the wake of the European debates about

criminology and criminal anthropology, and their

immigration to Great Britain and the United States,

the English-speaking world took the lead in

discussions of criminology. In the English language,

1890 was a watershed year after which the frequency

of the word criminology steadily grew during the first

half of the twentieth century, while interest in

criminal anthropology effectively disappeared by

1925 (see Figure 3). This transaction did not occur in

Italy and France until the 1940s (see Figures 1 and 2).

But defining the word criminology in English has

always been a treacherous endeavor.

Arguably, two early definitions by American

sociologists (published within one year of each other)

have been vying for the field for almost a century.

The first came from Thorsten Sellin (1938), who

insisted that criminology is scientific and is a pure

science, not an applied science: “The term

‘criminology’ should be used to designate only the

body of scientific knowledge and the deliberate

pursuit of such knowledge. What the technical use of

knowledge in the treatment and prevention of crime

might be called, I leave to the imagination of the

reader” (p. 3). The second definition came from

Edwin Sutherland (1939), who made no mention of

science but did extend the scope of criminology into

studies of law and society: “Criminology is the body

of knowledge regarding crime as a social

phenomenon. It includes within its scope the

processes of making laws, and of breaking laws, and

of reacting toward the breaking of laws” (p 1). Three

questions raised between these two definitions of

criminology have informed many of the subsequent

attempts to define the field:

1. Is criminology scientific?

2. Is criminology pure or applied research?

3. Is criminology the study of crime, narrowly

defined, or the study of crime and quite a bit

more (including ethics, law, justice, and

society)?

Criminologists since Sellin and Sutherland have

been split on these questions. Like Sellin, Elliott and

Merrill (1941, as cited in Sharma, 1998) thought that

criminology is scientific but, unlike Sellin, they

sought to extend the scope of criminology from basic

to applied research: “Criminology may be defined as

the scientific study of crime and its treatment” (as

cited in Sharma, 1998,

74 W

ILSON

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

Figure 3: A Google Ngram of the Frequency of the Words

Criminal Anthropology and Criminology in English from 1875-1975

pp. 1–2). Like Sutherland, Taft (1956, as cited in

Sharma, 1998) made no mention of science and

characterized criminology as a broadly

interdisciplinary field extending from academic to

political concerns: “Criminology is the study which

includes all the subject matter necessary to the

understanding and prevention of crimes together with

the punishment and treatment of delinquents and

criminals” (as cited in Sharma, 1998, p. 2). Jones

(1965) thought (like Sellin) that criminology is

scientific but (like Sutherland) that it is a social

science: “[Criminology is] the science that studies the

social phenomenon of crime, its causes and the

measures which society directs against it” (p. 1).

Explicitly building off of Sellin’s definition,

Wolfgang (1963) wrote that criminology is a science,

and it is, in fact, a discipline in its own right,

“autonomous,” as opposed to a broadly

interdisciplinary enterprise:

The term ‘criminology’ should be used to

designate a body of scientific knowledge

about crime…. Criminology should be

considered as an autonomous, separate

discipline of knowledge because it has

accumulated its own set of organized data

and theoretical conceptualisms that use the

scientific method, approach to

understanding, and attitude in research. (pp.

155–156)

Here, Wolfgang (again like Sellin) focused

criminology on a narrow topic— “knowledge about

crime”—yet Hoefnagels (1973) refused (like

Sutherland) to mention science and extended (again

like Sutherland) the bounds of the field far beyond

the matter of crime causation, suggesting rather

ambitiously that “criminology studies the formal and

informal processes of criminalization and

decriminalization, crime, criminals and those related

thereto, the causes of crime and the official and

unofficial responses to it” (p. 45). Most abstractly,

perhaps least helpfully, Garland (1994) wrote that

“criminology [is] a specific genre of discourse and

inquiry about crime—a genre which has developed in

the modern period and which can be distinguished

from other ways of talking and thinking about

criminal conduct” (p. 17).

There are even slightly different inflections in the

definition of the word criminology among the three

largest and most knowledgeable entities on the

subject, the American Society of Criminology (ASC),

the European Society of Criminology (ESC), and the

British Society of Criminology (BSC). Both the ASC

(2006) and the ESC (2003) define criminology as

“scholarly, scientific, and professional knowledge,”

but where the ASC specifies that its members pursue

THE WORD CRIMINOLOGY 75

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

“knowledge concerning the measurement, etiology,

consequences, prevention, control and treatment of

crime and delinquency” (para. 1), the ESC’s

definition of criminology more clearly emphasizes

institutional matters of law and justice, “including the

measurement and detection of crime, legislation and

the practice of criminal law, and law enforcement,

judicial, and correctional systems” (sec.1.c). For its

part, the BSC (2011) characterizes criminology not as

an academic pursuit, but rather as a public service,

stating that its objective is “to advance public

education about crime, criminal behaviour and the

criminal justice systems” (sec. 3.1).

Sometimes these competing definitions simply

register different emphases; sometimes they point to

fundamental disagreements about what criminology

is. Is it a discipline in its own right (“autonomous,” as

Wolfgang said), or is it an interdisciplinary field? Is it

a specifically modern discourse (as Garland said), or

are there pre-modern criminologies? Is it only

academic, or can it be public? Is it necessarily

scientific? If so, what does it mean to be scientific?

And if it is a science, is it a “pure science,” narrowly

concerned with understanding crime, or an “applied

science” also concerned with the prevention of crime

and the treatment of criminals? If, however,

criminology is not scientific, then what is it instead?

And is it only the study of crime, or is it, more

broadly, the study of crime and criminal justice? Or

is it, even more broadly, the study of crime, criminal

justice, and anything under the sun that relates to

crime and justice (including ethics, law, politics,

culture, and so forth)? Is it better to have a narrow

and limiting definition of the word criminology or a

broad and inviting definition?

The difficulties of questions such as these, and the

different responses different criminologists have

given to them, have led some to suggest that the best

definition of criminology is no definition at all. For

example, in their introduction to The SAGE

Dictionary of Criminology, McLaughlin and Muncie

(2005) considered the contested and contradictory

perspectives in criminology and concluded, “There

is, therefore, no one definition of ‘criminology’ to be

found in this dictionary but a multitude of noisy,

argumentative criminological perspectives” (p. xiii).

Another recent collection entitled What is

Criminology? (Bosworth & Hoyle, 2011) offered not

one but 34 answers to this question in its 34 chapters.

Actually, the collection offered no answer at all,

insofar as it split the question of the book’s title,

What is Criminology?, into six sub-questions: “What

is criminology for?” “What is the impact of

criminology?” “How should criminology be done?”

“What are the key issues and debates in criminology

today?” “What challenges does the discipline of

criminology currently face?” and “How has

criminology as a discipline changed over the last few

decades?” (pp. 4–7). These are all fascinating

questions (as, indeed, each of the 34 chapters in this

ground-breaking collection are invaluable reflections

on criminology by some of the world’s most

renowned criminologists), but they are questions that,

in their increased specificity, deflect attention away

from the difficult, abstract question of the book. So,

indeed, what is criminology?

A standard definition of the word criminology is

valuable insofar as it can help professional bodies

determine who is qualified to conduct research under

this banner, and therefore who should get jobs and

funding. Indeed, there is a relationship, and

sometimes a tension, between one’s definition of

criminology and one’s sense of who should be

considered a criminologist. On the one hand, the

criminologist who believes that any- and everyone

who has something to contribute to our understanding

of crime, criminals, and criminal justice should be

offered jobs and funding to conduct research tacitly

accepts a broad definition of what criminology is. On

the other hand, the criminologist who believes that

the success of criminology relies upon a narrow

definition of the field tacitly endorses the idea that

jobs and funding should be offered only to those who

conduct their research on the right topics and in the

right ways, whatever they may be. Thus, we must

know what criminology is in order to know a

criminologist when we see one. So, yet once more,

what is criminology?

The Etymology of Criminology

As we look toward the formulation of a new

definition, the etymology of the word criminology

can throw some light on the rather broad scope of this

field in terms of both the issues it addresses and the

methods it uses to address those issues.

The Etymology of –logy

First, with respect to those methods, the suffix -

logy indicates a systematic, though not necessarily

scientific, study of something. From the Greek word

λόγος, “word, speech, reason, discourse, account,”

the suffix -logy signifies the study of what is

indicated by the root word. It sounds simple enough,

and from this perspective criminology would be

defined as “the study of crime” or “the study of

criminals.” But the connotations of -logy complicate

matters. The -logy suffix often suggests a specifically

scientific study, as in words such as biology (the

scientific study of living organisms), geology (the

scientific study of the structure of the earth), and

76 WILSON

Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society – Volume 16, Issue 3

meteorology (the scientific study of the atmosphere).

What does it mean for a study to be “scientific”? The

word science comes from the Latin word scire, “to

know,” and science is, etymologically speaking,

simply “knowledge,” but scientific knowledge is not

just any knowledge, as explained in the Oxford

English Dictionary:

In modern use, [the word science is] often

treated as synonymous with ‘Natural and

Physical Science,’ and thus restricted to

those branches of study that relate to the

phenomena of the material universe and

their laws…. This is now the dominant sense

in ordinary use. (“Science,” 2014, 5b)

The natural and physical sciences have strictly

delimited content, namely material objects, and a

strictly defined method, the so-called scientific

method of observation, hypothesis, experiment, and

analysis. Some criminologists, among them the early

positivists, have argued for an understanding of

criminology as this kind of science, in which case the

definition of criminology would read something like

“the scientific study of the physical bodies of

criminals.”

Historically and etymologically, this definition is

unacceptable because criminological studies based in

biology always have and always will spill over into

psychological and sociological concerns—consider

the recent advent of “biosocial criminology” (see

Walsh, 2002). Indeed, psychology and sociology are

-logy words that refer to fields which employ the

scientific method on mental and social transactions,

not material objects. That is, the -logy suffix can and

often does signify a study that uses the scientific

method to address something that is not physically

found in the material world, something that is an

event, not an object, something like crime.

Many criminologists group criminology in this

class of -logy words, taking it to mean “the scientific

study of crime as a social phenomenon,” but we

should also exercise some caution here for two

reasons. First, there are plenty of -logy words that are

not scientific, such as theology (the systematic study

of God) and etymology (the systematic study of the

origins of words, the activity in which I engage in

this essay). There is no meaningful sense in which

theology and etymology are scientific enterprises as

we now use the term science (indeed, theology is

often seen as uniquely unscientific). Second, the

word science is simply too overwrought with

multiple meanings—pulled, as it is, between a

description of content (material objects) and a

description of method (controlled experimentation)

—to be useful for a definition of criminology. In

other words, the answer to the question, “Is

criminology a science?” is and always will be, “It

depends on what you mean by ‘science.’” If by

science you mean “the study of the structure and

behavior of the physical and natural world through

observation and experiment,” then, no, criminology is

not a science. If, however, by science you mean “a

connected body of observed facts and/or