THE ECONOMIC BENEFITS

OF U.S. TRADE

May 2015

2

Table of Contents

Ten Facts about U.S. Trade ....................................................................................................................... 3

I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5

II. The Economic Effects of U.S. Trade Integration .............................................................................. 7

Classic Gains from Trade .............................................................................................................. 7

Enhanced Productivity ........................................................................................................... 7

More Innovative Activity ..................................................................................................... 11

Higher Living Standards ....................................................................................................... 12

Labor Market Implications of Trade and Trade Agreements ................................................ 14

Higher Wages ........................................................................................................................ 14

Development Effects of Trade ................................................................................................... 22

Increased Economic Growth ............................................................................................... 22

Better Working Conditions .................................................................................................. 24

Stronger Environmental Protection ................................................................................... 26

Broader Inclusion and Participation ................................................................................... 29

III. Sector-Specific Trends in U.S. Trade ............................................................................................... 33

The Rise of Services Trade.......................................................................................................... 35

Manufacturing Rebound ............................................................................................................ 38

Robust Agricultural Trade .......................................................................................................... 40

IV. Current Trade Negotiations .............................................................................................................. 43

Trans-Pacific Partnership............................................................................................................ 45

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership ................................................................... 46

V. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................... 47

References ................................................................................................................................................. 48

3

Ten Facts about U.S. Trade

President Obama’s top priority is to make sure the United States builds on its economic

momentum by continuing to grow businesses, create jobs, and expand the middle class. That is

why the President is committed to free and fair trade agreements that level the playing field and

benefit American businesses and workers. This report presents original empirical evidence,

alongside a summary of the extensive economic literature, on a broad range of effects of

enhanced U.S. trade and U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs).

1

Highlights from this report include:

1. U.S. businesses must overcome an average tariff hurdle of 6.8 percent, in addition to

numerous non-tariff barriers (NTBs), to serve the roughly 95 percent of the world’s

customers outside our borders. The United States is already one of the most open markets

in the world, meaning that the main impact of new trade agreements would be to decrease

foreign barriers to U.S. exports. In 2014, almost 70 percent of U.S. imports crossed our

borders duty-free, but many of our trading partners maintain higher tariffs that create steep

barriers to U.S. exports.

2. Exporters pay higher wages, and the average industry’s export growth over the past twenty

years translated into $1,300 higher annual earnings for the typical employee. Studies of U.S.

manufacturing industries document that, on average, export-intensive industries pay workers

up to 18 percent more than non-export-intensive industries. Controlling for industry,

location, and worker characteristics, CEA finds that the average industry’s increase in exports

in the 1990s and 2000s translated into an additional $1,300 in annual earnings for the typical

middle-class worker.

3. Middle-class Americans gain more than a quarter of their purchasing power from trade.

Trade allows U.S. consumers to buy a wider variety of goods at lower prices, raising real wages

and helping families purchase more with their current incomes. This is especially important

for middle-class consumers who spend a larger share of their disposable income on heavily-

traded food and clothing items. Compared to a world with no trade, median-income

consumers gain an estimated 29 percent of their purchasing power from trade.

4. Over the past twenty years, the average industry’s increase in exports translated into 8

percent higher labor productivity, or almost a quarter of the total productivity increase over

that time. About half of all U.S. imports are inputs that businesses use to produce final goods,

which lowers firms’ production costs by making a greater variety of inputs available at lower

prices. Additionally, economic research shows that trade increases productivity for

businesses and the economy as a whole.

5. When countries make trade deals with China, outsourcing of American jobs increases, while

U.S. trade agreements do not change the rate of U.S. investment abroad. Trade agreements

1

This report complements work already published in Chapter 7 of the Council of Economic Advisers’ (CEA) 2015

Economic Report of the President.

4

with China offer countries preferential access to the vast Chinese market while accepting low

labor and environmental standards. U.S. FTAs, on the other hand, raise standards across the

board and help U.S. businesses export to foreign markets while still producing goods here.

U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in FTA partner countries shows little to no change after

completion of a trade agreement. However, China’s completion of a trade agreement

increases U.S. FDI in China’s FTA partners.

6. Trade raises labor standards and incomes abroad, helping developing countries lift people

out of poverty and expanding markets for U.S. exports. Research suggests that trade has

helped decrease poverty by raising wages around the world and also finds that expanding

U.S. market access promotes higher-quality employment in less-developed countries as

workers shift from informal to formal employment. Enforceable labor standards, which form

a central part of trade agreements the United States is currently negotiating, have also

complemented trade’s direct effects.

7. For every 1 percent increase in income as a result of trade liberalization, pollution

concentrations fall by 1 percent. This happens because the adoption of clean technologies

spread through trade more than offsets emissions resulting from increased transportation or

production. Current trade agreements amplify these effects: the Administration includes

environmental commitments as a core part of its values-driven trade approach, including

commitments to protect oceans, combat wildlife trafficking, and eliminate illegal logging.

8. Trade helps lower the gender wage gap, with a 10 percentage point decrease in tariffs

leading to a 1 percentage point drop in the wage gap. CEA studied the relationship between

tariffs and the gender wage gap, finding that industries with larger tariff declines saw greater

reductions in the wage gap. Trade also decreases discrimination based on race and

immigration status and is correlated with better human-rights conditions.

9. The United States has a $43 billion surplus in agricultural trade and is a worldwide leader

in agriculture, employing almost 1.5 million American workers. In 2014, one-half of the

wheat, rice, and soybeans produced in the United States was exported, along with over two-

thirds of almonds and walnuts and four-fifths of cotton and pistachios. The U.S. Department

of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that every $1 in agricultural exports stimulates another $1.22

in related business activity, so that agricultural exports increased total economic output by

almost $350 billion in 2014.

10. The United States is the global leader in services exports. Over the past 34 years, real U.S.

services exports have grown more than seven-fold, particularly in areas like insurance and

financial services. As a result, knocking down barriers to services trade is especially important

for the American workforce. Compared to the average across 40 other countries, including

most advanced economies and large emerging markets, the United States has lower trade

barriers in 14 out of 18 different service sectors. By one estimate, if U.S. services reached the

same export potential as manufactured goods, total U.S. exports could increase by as much

as $800 billion.

5

I. Introduction

The world’s economies are more interconnected than ever before. Since the middle of the last

century, declining policy barriers, transportation costs, and communication costs have driven a

swift rise in world trade and foreign investment, far outpacing the growth in world output. Even

so, the potential economic gains from trade for the United States are far from exhausted. U.S.

businesses must overcome an average tariff hurdle near 6.8 percent and countless non-tariff

measures to serve the roughly three-quarters of world purchasing power and more than 95

percent of world population that resides outside America's borders.

Expanding trade allows production inputs such as labor and capital to be used more efficiently,

which raises overall productivity. U.S. businesses that grow in response to increased market

access abroad support additional job opportunities. These firms are more productive and rely

more on capital and skilled workers, on average, than similar non-exporting firms. Partly because

of this, the wages paid by exporting firms tend to be higher than wages paid by non-exporters in

the same industry. In particular, evidence for the United States suggests that, in manufacturing,

average wages in exporting firms and industries are up to 18 percent higher than average wages

in non-exporting firms and industries.

In addition, international trade helps U.S. households’ budgets go further. Because our trading

partners also specialize in the goods and services for which they are relatively more productive,

the prices of those goods and services in the United States are lower than if we could only

consume what we produce. Trade also offers a much greater diversity of consumption

opportunities, from year-round fresh fruit to affordable clothing. In fact, research estimates that

the variety of imported goods increased approximately three-fold between 1972 and 2001. This

increase in variety provides U.S. consumers with value equivalent to 2.6 percent of gross

domestic product (GDP). According to other estimates, the reduction in U.S. tariffs since World

War II contributed an additional 7.3 percent to U.S. GDP, or approximately $1.3 trillion in 2014.

Distributed equally, that translates into an additional over $10,000 in income per American

household.

By increasing global production and consumption opportunities, international trade can promote

world economic growth and development. Trade among nations offers a mechanism to reduce

global poverty, which may decrease child labor and pull developing-country workers into jobs

with improved working conditions. Trade can also be a force toward the empowerment of

traditionally marginalized groups; for example, some empirical evidence suggests that decreased

discrimination against women is related to the effects of global competition brought about by

trade. Trade also facilitates the spread of new green technologies throughout the world, which

decreases emissions and improves air and water quality.

Because the process of globalization shifts resources within national economies, however, it can

also create challenges in areas like income inequality. For this reason, it is critical that

globalization is managed—in terms of both the types of trade agreements the United States

enters into and the domestic policies that are in place—in a way that ensures that more

6

Americans can take advantage of the opportunities afforded by trade, while being better able to

meet any challenges trade creates. Therefore, President Obama’s values-driven trade policy

seeks to do what is best for U.S. businesses and workers by enforcing international agreements

that improve labor and environmental standards around the world, combat corruption, and

strengthen the rule of law abroad. Encouraging such trade agreements maximizes globalization’s

benefits while minimizing globalization’s side effects. For example, new U.S. trade agreements

promote and enforce the rights of workers abroad, “leveling up” rather than “leveling down” and

risking workers’ rights in the United States. The Administration’s domestic policies, such as skills

training, infrastructure investment, and business tax reform, allow workers and firms to take

better advantage of the opportunities trade offers. At the same time, policies like Trade

Adjustment Assistance and the Affordable Care Act help protect workers from some of the

challenges associated with globalization.

The rest of this report is structured as follows. In Section II, we highlight the main economic

benefits of U.S. trade integration, starting with a review of the classic gains from trade, such as

higher productivity, faster innovation, lower prices, and more varieties. Next, we survey research

showing how trade supports jobs in larger, more productive, and higher-paying exporting firms

and comment on the role of U.S. FTAs in the outsourcing of jobs. The section ends with a

discussion of often overlooked development effects of expanding trade relations. Section III

presents a brief analysis of sector-specific trends in U.S. trade, highlighting separately

manufacturing, agriculture, and services. Section IV focuses on current trade negotiations with

countries in the Asia-Pacific (Trans-Pacific Partnership, TPP) and the European Union

(Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, T-TIP), and section V concludes.

7

II. The Economic Effects of U.S. Trade Integration

The process of globalization offers many new economic opportunities, but it also has created

challenges. Globalization is a result of both worldwide economic, social, and technological trends,

as well as specific policy changes. Analyzing globalization’s general impact is different from

analyzing any particular trade agreement. Understanding the impact of any particular agreement

requires both historical context, as well as an analysis of the relative tariffs of trading partners,

NTBs, and the relevant standards (for instance, on labor, environment, and intellectual property).

Classic Gains from Trade

Nevertheless, historical experience does underscore the potentially large gains from trade. In the

past half-century, as trade barriers around the world have diminished, these gains have

multiplied and are increasingly shared across different countries and different industries. Among

these classic gains from trade are enhanced productivity, increased innovative activity, and lower

prices on and greater variety of goods and services for consumers and producers.

Enhanced Productivity

Defined as the amount of output that can be generated with a given level of inputs, total factor

productivity (TFP) growth is historically associated with increasing real wages. Productivity

growth is necessary for sustained faster income growth of U.S. workers and profoundly important

for the living standards of middle-class Americans, in particular. Specifically, one of the major

factors in disappointing middle-class income growth since the 1970s has been the slowdown in

productivity growth that started around 1973. In fact, if productivity had continued growing at

the same rate as it did between 1948 and 1973—that is to say, at 1.9 percent per year—and

inequality followed its actual path, then Americans’ annual incomes in 2013 would have been 58

percent higher, a fraction equivalent to roughly $30,000 per household.

There is a large body of economic research on the relationship between international trade and

productivity growth, and its conclusions are generally positive for trade. For example, a recent

review by De Loecker and Goldberg (2014) concludes that “there is one robust finding that

emerges from this literature: globalization improves industry performance.” However, this

literature has not reached a consensus on why trade improves productivity. Long-established

theories of international trade suggest that trade liberalization will improve a nation’s economic

productivity through several different channels.

Production Reallocation

First, trade can improve economy-wide productivity by allowing each country to focus on its

comparative advantage. This benefit follows from the classic theory of trade gains first

expounded by economist David Ricardo in 1817. Productivity gains can also occur within an

industry if there is some heterogeneity between firms in that industry (Melitz 2003), as labor and

resources shift in response to lower trade costs to the most efficient firms—those best able to

take advantage of the opportunity to export. Several studies find evidence of this phenomenon

in U.S. manufacturing. For example, one study compares high- and low-productivity plants during

a time of falling tariffs and transportation costs and finds that industry productivity rises when

8

trade costs fall (Bernard et al. 2006). Additionally, trade may improve the productivity of specific

firms in an industry or even a single factory. If increased trade liberalization creates more demand

from overseas for certain products, firms may be induced to reallocate resources toward core

products. Bernard et al. (2011) find evidence to this effect.

Increased Market Size

Beyond the productivity gains from reallocation, additional gains arise when firms’ export

markets expand as the foreign trade barriers they face fall. If these firms can become more

efficient as they grow (a phenomenon known as economies of scale), their productivity will rise.

Lileeva and Trefler (2010) find evidence that Canadian firms that received preferential access to

the huge U.S. market under the terms of the 1989 Canada-U.S. FTA improved labor productivity

by investing in productivity-enhancing activities. Bustos (2011) finds similar evidence from

Argentina, which entered into a trade agreement with Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay in 1991.

Across these studies, the common mechanism is that exporting induces investments in

technology.

Learning-by-Exporting

Since the early 1990s, empirical research on trade has increasingly focused on firm-level data,

and several recent studies have found evidence of a causal link from trade to increased

productivity. Export activity offers firms opportunities to learn about foreign markets—perhaps

even gaining technical expertise from foreign buyers—leading to increased productivity (De

Loecker 2013). Productivity gains through exporting may also occur through increased

competition from foreign producers. This “learning-by-exporting” theory has support in a

literature spanning many countries and time periods. For example, De Loecker (2007) finds

evidence of learning by exporting for Slovenia and Van Biesebroeck (2005) finds support in sub-

Saharan Africa. A recent paper by Atkin, Khandelwal, and Osman (2014) experimentally

manipulates access to trade so as to simulate a randomized trial, and finds strong evidence that

Egyptian rug manufacturers (who randomly received an opportunity to export) became more

productive as a consequence of foreign trading opportunities.

While these findings may or may not generalize to more technologically advanced U.S. exporters,

they provide important evidence of a causal link between trade and productivity, suggesting that

the productivity improvements associated with trade do not necessarily only come through

domestic resource reallocation. Using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Foreign Trade Statistics

in combination with data from the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (NBER)

Manufacturing Industry Database (Becker, Gray, and Marvakov 2013) for the years 1989 to 2009,

CEA’s analysis confirms findings in the literature on the productivity-enhancing effects of

international trade. Table 1 reports coefficient estimates for two different specifications relating

trade to the level of labor productivity, defined as value-added per employee. Across the 377 6-

digit North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) industries, CEA documents the

positive association of international trade and labor productivity.

9

Relying on cross-industry and over-time variation in trade, our estimation includes industry fixed

effects to control for time-invariant differences across industries, which may affect productivity

levels, as well as year fixed effects to account for common cyclical variation, including in inflation.

The estimation also controls for industry size and the level of importing, where relevant. Though

the estimate implies that tariff reductions are associated with decreases in labor productivity,

this measured effect is insignificantly different from zero. The estimates in the second column,

however, point to a statistically and economically significant relationship. Industries with larger

increases in exports report larger increases in labor productivity. A 10 percent increase in an

industry’s exports is associated with a 0.2 percent increase in the industry’s labor productivity.

Over the two decades between 1989 and 2009, based on the average industry’s increase in

exports, these estimates imply approximately an additional 8 percent labor productivity boost as

compared to what would have happened with no change in international trade. Since average

labor productivity in the United States increased by about 35 percent over these two decades,

these estimates imply that international trade may have been responsible for about one quarter

of total productivity growth over the 1990s and 2000s.

The literature also suggests that many productivity improvements associated with exporting are

due to increased investments in technology. We provide some evidence for this hypothesis in

Table 2, which documents that industries with larger increases in exports are also those industries

with the largest increases in capital investment. Specifically, a 10 percent increase in exports is

associated with about a 0.6 percent increase in investment. Therefore, the average industry

invested about 22 percent more over the 1990s and 2000s, than would have been the case in a

world with no change in exports.

Tariff

0.060

(0.047)

Log Exports

0.022*

(0.013)

Indus try Fi xed Effects YES YES

Yea r Fixed Effects YES YES

Control for Imports NO YES

Control for Indus try Size YES YES

Observa tions 7,871 7,961

Log Labor Producti vity

Table 1: Trade and Labor Productivity

Note: Labor productivity is defined as value added per employee. Tariffs are the simple average of applied rates. Industry size is

defined as the inflation-adjusted value of total shipments by U.S. firms. Robust standard errors, clustered at the industry level, are in

parentheses. *** denotes significance at the 1-percent level, ** denotes significance at the 5-percent level, and * denotes significance

at the 10-percent level. The panel dataset comprises over 370 industries over the 1989-2009 period. Industries are defined according

to NAICS and are disaggregated to the six-digit level.

Source: Data on value added, employment, total shipments, and industry-specific price indices are from the NBER Manufacturing

Industry Database. Data on tariff rates are from the World Integrated Trade Solution database maintained by the United Nations

Statistical Division. Data on imports and exports by industry from 1989-2006 are from the U.C. Davis Center for International Data.

Data on imports and exports by industry from 2007-2009 are from the Foreign Trade Division of the U.S. Census Bureau.

10

Table 3 takes the analysis one step further to ask whether trade liberalization via decreases in

tariffs increases the rate of productivity growth. Industries that faced larger tariff declines over

the 1990s and 2000s experienced larger increases in both labor productivity growth and TFP

growth. A 10 percentage point decrease in tariffs corresponds to about a 0.4 percentage point

increase in labor productivity growth and about a half percentage point increase in TFP growth

over the two decades. In an era of relatively low productivity growth, these are large changes.

In summary, some studies conclude that trade leads to increased industry-wide productivity

through a reallocation of market share towards more productive firms (Melitz 2003; Bernard and

Log Investment

Log Exports

0.063*

(0.034)

Indus try Fixed Effects YES

Year Fixed Effects YES

Control for Imports YES

Control for Industry Size YES

Observa ti ons 7,961

Table 2: Trade and Investment

Source: Data on investment, total shipments, and industry-specific price indices are

from the NBER M anufacturing Industry Database. Data on imports and exports by

industry from 1989-2006 are from the U.C. Davis Center for International Data. Data on

imports and exports by industry from 2007-2009 are from the Foreign Trade Division of

the U.S. Census Bureau.

Note: Investment is deflated using industry-specific price deflators. Industry size is

defined as the inflation-adjusted value of total shipments by U.S. firms. Robust

standard errors, clustered at the industry level, are in parentheses. *** denotes

significance at the 1-percent level, ** denotes significance at the 5-percent level, and *

denotes significance at the 10-percent level. The panel dataset comprises over 370

industries over the 1989-2009 period. Industries are defined according to NAICS and are

disaggregated to the six-digit level.

Labor Productivi ty Growth TFP Growth

Tariff

-0.041*** -0.048***

(0.007) (0.006)

Indus try Fi xed Effects YES YES

Yea r Fixed Effects YES YES

Control for Indus try Size YES YES

Observa tions 7,867 7,867

Table 3: Trade and Productivity Growth

Note: Labor productivity is defined as value added per employee. TFP is defined as in Becker et al. (2013). Labor productivity growth

and TFP growth are defined as the one-year growth rate. Tariffs are the simple average of applied rates. Industry size is defined as

the inflation-adjusted value of total shipments by U.S. firms. Robust standard errors, clustered at the industry level, are in

parentheses. *** denotes significance at the 1-percent level, ** denotes significance at the 5-percent level, and * denotes significance

at the 10-percent level. The panel dataset comprises over 370 industries over the 1989-2009 period. Industries are defined according

to NAICS and are disaggregated to the six-digit level.

Source: Data on value added, employment, TFP growth, total shipments, and industry-specific price indices are from the NBER

Manufacturing Industry Database. Data on tariff rates are from the World Integrated Trade Solution database maintained by the

United Nations Statistical Division.

11

Jensen 1999; 2004a; 2004b). In other words, the selection of the most productive firms into

international markets means that productivity may cause trade. Other studies argue that the

causality goes in the opposite direction, with global trade driving increases in productivity (for

example, Lileeva and Trefler 2010 and Bloom, Draca, and Van Reenen 2011). It is difficult to

distinguish between these two mechanisms empirically, since both suggest a positive relationship

between trade and productivity. And in practice, both stories could be correct: trade may cause

productivity, at the same time as productivity causes trade.

More Innovative Activity

Most people associate the term “innovation” with new tools and technologies that improve their

daily lives. This makes sense; major innovations like the automobile or computer have a visible

impact on living standards. Economists, on the other hand, tend to focus on aggregate

innovation, as measured by TFP, as we touched on in the previous section. However, a growing

body of work also considers the impact of trade on innovative activities, such as research and

development (R&D) spending and patenting. Because there are several different mechanisms

that could produce this effect, it is helpful to divide the relevant theoretical channels into two

broad groups: (1) trade stimulates innovation directly, and (2) trade alters the incentives to

innovate.

Innovation Production Function

Both exporters and importers are frequently exposed to new ideas and novel tools, materials, or

techniques that make them more productive. Some of the learning that results is simply copying.

For example, many multinational companies have systems and standards to promote the

diffusion of “best practices” within their global supply chains (MacDuffie and Helper 1997 and

Distelhorst, Hainmueller, and Locke 2014). Learning also occurs when a firm adapts novel ideas

to suit its own operating environment, leading to both new goods and greater productivity. For

example, many American manufacturers and businesses in other industries have adopted aspects

of the “lean” production system, which was originally developed in Japan, and realized

substantial productivity benefits by tailoring the underlying ideas to meet their own needs (Teich

and Faddoul 2013).

Many of the new ideas that diffuse through trade are embodied in intermediate inputs. In fact,

roughly half of all U.S. imports are inputs into the production of final goods. Increases in the

quality and variety of these inputs can reduce domestic firms’ production costs, thereby inducing

American importers to expand production and employment. For example, Romer (1994) shows

that a country’s gains from international trade increase substantially when the benefits of

cheaper and more varied imported production inputs are taken into account.

Trade can also increase innovative productivity by allowing innovators to specialize. Greater

specialization can increase the amount of knowledge produced per unit of R&D investment if

companies in different countries focus on innovating in the areas where they have a comparative

advantage. For example, if engineers at one firm focus on improving memory chips, and

engineers at another firm focus on improving microprocessors, the R&D productivity of each firm

may be higher, leading to better and cheaper computers than if each company had to improve

12

both components simultaneously. Branstetter, Fisman, and Foley (2006) show that strengthening

foreign intellectual property protection leads to more outward licensing from the United States,

where U.S. companies allow other companies to use their ideas, products, or processes in

exchange for royalty payments. Specifically, the authors find that royalty payments from foreign

affiliates to U.S. parent companies increase by 16.6 percent on average following a reform that

strengthens intellectual property rights in the affiliates’ home country. This finding highlights the

role of NTBs for shaping trade in ideas, particularly if one country specializes in the “R” and the

other in the “D.”

2

The Incentives to Innovate

International trade allows companies to access a larger market, which yields more profit for a

given level of innovation, and therefore raises the incentive to innovate. For example, the global

reach of the “App Stores” managed by Apple and Google contributes to the large number of

software developers who populate those distribution platforms. Aw, Roberts, and Xu (2008) find

that firms with experience in foreign markets have a greater probability of R&D investment,

consistent with the idea that accessing larger foreign markets translates into higher expected

returns to R&D.

Even holding market size constant, increased trade can promote innovation by strengthening

competition. More than fifty years ago, Arrow (1962) pointed out that a monopolist may have

relatively weak incentives to innovate because its innovations do not allow it to “steal” business

from competitors. A similar idea appears in more recent “Schumpeterian” models of innovation

and economic growth (Aghion et al. 2005), where competition can promote growth by increasing

the expected payoffs of successful innovation. By bringing companies into a worldwide

marketplace, trade greatly increases the incentive for a firm to innovate in order to win business

from its competitors (Bloom, Draca, and van Reenen 2011), reinforcing the market-size effects

discussed above. However, Schumpeterian models also suggest that too much competition can

reduce innovation, because firms will not wish to invest in R&D if their discoveries are easily

copied and the resulting profits immediately dissipated.

Higher Living Standards

Perhaps the most broadly shared benefit of increased trade is lower prices for consumers and

producers in the domestic market. By allowing our trading partners to produce the goods in

which they are relatively more efficient, the United States can import at lower prices than would

prevail if we were to use our scarce resources to produce the goods ourselves. This “specialize in

what you do best, trade for the rest” philosophy makes everyday goods and services more

affordable and enhances the real earning power of American workers’ and families’ current

incomes.

Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal (2014) note that lower-income consumers spend a larger share of

their disposable income on heavily-traded food and clothing items, while higher-income

consumers devote a relatively larger share to spending on services, which can be harder or

2

For more analysis of trade in ideas, please see Box 7-1 in CEA (2015a).

13

impossible to trade. This implies that international trade is relatively more beneficial to middle-

class consumers. Specifically, as is illustrated in Figure 1, the authors estimate that U.S.

consumers at the 10

th

percentile of the income distribution would lose more than half of their

purchasing power if the United States shut out all international trade, owing to higher prices.

Median-income consumers would still lose more than a quarter of their purchasing power, as

compared to only a 3 percent gain in purchasing power for Americans at the 90

th

percentile of

the income distribution. Although these estimates are based on an extreme counterfactual, the

numbers remind us of the potential for new trade agreements to reduce prices in the United

States and raise consumers’ purchasing power, particularly for middle-class consumers.

Another underappreciated benefit of trade liberalization is increased variety for domestic

consumers and producers. With new importers come new products. This expanded selection

increases the welfare of consumers who appreciate having more choice. Broda and Weinstein

(2006) examine historical trade statistics and determine that the variety of imported goods

increased approximately three-fold between 1972 and 2001. Conventional import price indices

have trouble incorporating the value of increased choice, so this finding suggests that import

prices have effectively fallen even further than the conventional import price index would

suggest. The researchers estimate that this increased variety has provided U.S. consumers with

value equivalent to 2.6 percent of GDP, or approximately $450 billion in 2014. Mostashari (2010)

updates the calculations in Broda and Weinstein (2006) and reports that the number of varieties

of goods imported into the United States increased 33 percent between 1989 and 2007.

In addition, recent estimates suggest that over one-half of all U.S. imports are intermediate

inputs into the production process. The greater variety of imports available at lower prices

reduces firms’ production costs, thereby helping American businesses to expand production and

employment and increase the wages they can afford to pay. Since World War II, reductions in

U.S. tariffs are estimated to have contributed an additional 7.3 percent to U.S. GDP (Bradford,

Grieco, and Hufbauer 2005).

62

29

3

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

10th 50th 90th

Figure 1: Gains from Trade Across the Income Distribution

Percent of Purchasing Power Gained from Trade

Income Percentiles

Aggregate

Gains

Source: Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal (2014).

14

Labor Market Implications of Trade and Trade Agreements

Trade also has notable impacts on labor markets, many of them a direct result of the classic gains

from trade in terms of increased productivity and innovation. U.S. businesses that expand in

response to the increased foreign market access due to U.S. trade agreements support additional

jobs. The importance of such export-led job growth for the Nation’s income is reinforced by the

fact that wages in export-intensive manufacturing industries tend to be higher than wages in non-

export-intensive manufacturing industries. Of course, while the aggregate benefits of trade may

be large, they may also be unevenly distributed.

3

Trade, therefore, can also have adverse effects

for some workers. Domestic policies the Administration supports, such as investment in

infrastructure, worker training, and education, can help our labor force take advantage of the

considerable opportunities that trade opens up. For displaced workers and their families,

effective policies can help smooth the adjustment into new, potentially higher-paying jobs.

Higher Wages

Expanding U.S. market access abroad has important implications for the workforce at home. A

very long literature spanning decades and many different countries highlights that exporting

firms are systematically different from non-exporting firms even within the same industrial

category. Bernard and Jensen (1995) were the first to document this fact for the United States.

They note that exporting plants are larger in terms of employment, more productive in terms of

value added per worker, more strongly capital-intensive, and pay higher wages. These

differences persist even within detailed industrial categories, and controlling for firms’ regional

locations.

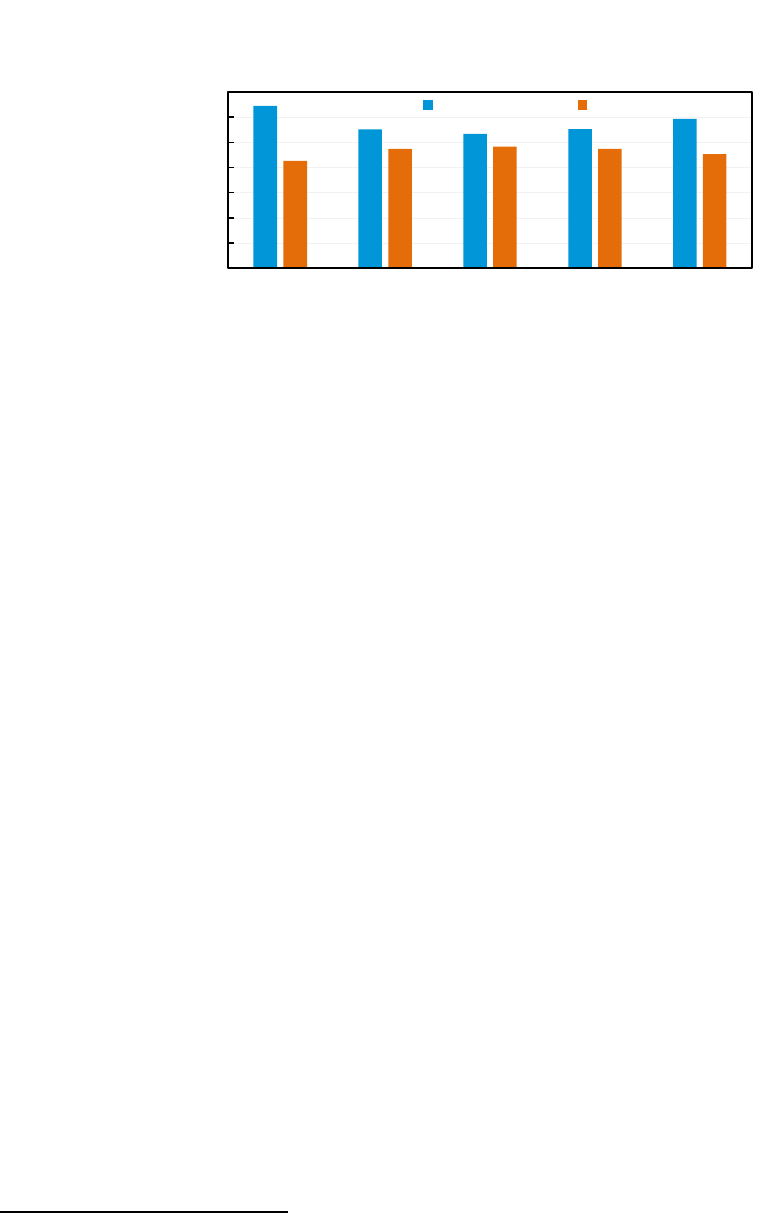

Figure 2 offers descriptive evidence relying on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Foreign Trade

Statistics matched to the NBER’s Manufacturing Industry Database. Export-intensive industries

are defined as those industries with above-average values of exports as a fraction of total

shipments (the export share) in 1989, and non-export-intensive industries are those industries

with below-average values of the export share in 1989.

4

For ease of illustration, in order to report

the various characteristics in comparable units, the Figure reports the industry’s characteristic as

a ratio to the average industry’s characteristic, calculated as described in the Figure note. On

average over the 1989 to 2009 period of data availability, relative to non-export-intensive

industries, export-intensive industries report 51 percent higher TFP growth, 17 percent higher

average wages (total wage bill per worker), 10 percent higher levels of labor productivity (total

shipments per worker), 17 percent higher value added per worker, and 31 percent higher capital

intensity (total real capital stock per worker), consistent with the findings in the academic

research.

3

For an examination of the relationship between trade and income inequality, refer to Chapter 7 of CEA (2015a). In

addition, Harrison, McLaren, and McMillan (2011) provide a summary of the large literature on the links between

globalization and inequality.

4

The average export share across the 377 6-digit NAICS industries was 12.7 percent in 1989.

15

Exporter Wage Premium

That exporters pay higher wages than similar non-exporters is a well-established feature of the

data across many countries and over decades (see Table 1 in Schank, Schnabel, and Wagner

2004). For the United States, estimates for the exporter wage premium (the amount by which

exporting industries and firms pay higher wages than non-exporting industries and firms) are as

high as 18 percent. Riker (2010) estimates that workers employed in U.S. export-intensive

manufacturing industries earned approximately 18 percent more than similar workers employed

in domestically-oriented manufacturing industries between 2006 and 2008. In follow-up work,

Riker and Thurner (2011) demonstrate that the relationship holds in services industries as well.

5

Controlling for industry differences, Bernard, Jensen, Redding, and Schott (2007) document a 6-

percent exporter wage premium in 2002: the average annual wage at exporting manufacturing

firms is 6 percent higher than the average annual wage at domestically-oriented manufacturing

firms.

5

In an update on this line of research, Riker (2015) estimates that workers employed in export-intensive

manufacturing industries earn a premium of 16.3 percent, and that workers employed in export-intensive services

industries earn a premium of 15.5 percent based on 2014 data.

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

TFP Growth Average

Wages

Labor

Productivity

Value Added

Per Worker

Capital

Intensity

Export-Intensive Non-Export-Intensive

Figure 2: Characteristics of Export-Intensive and

Non-Export-Intensive Industries, 1989-2009

Note: The ratio to the industry average is calculated as follows. Each industry’s

characteristic is measured relative to the industry average within the year and then averaged

over the 1989-2009 period and across export-intensive and non-export-intensive industry groups.

Source: National Bureau of Economic Research-Center for Economic Studies, Manufacturing

Industry Database; U.S. Census Bureau, Foreign Trade Statistics; CEA Calculations.

Ratio to the Industry Average

16

Source

Time Period

(s ector)

Wa ge Varia bl e

(a ggregati on)

Export Vari able

(a ggregati on)

Es timated Exporter

Wa ge Premi um

(i n percent)

Control Va riables

Bernard a nd Jensen (1995)

1976-1987

(ma nufa cturing)

Average annual

wage (pla nt)

Exporter dummy

(pla nt)

4.5

Capita l per worker

Hours per worke r

Plant s ize

Plant a ge

Multi pl ant dummy

Indus try Fixed Effects

Region Fixed Effects

Yea r Fixed Effects

Bernard a nd Jensen (1995)

1976-1987

(ma nufa cturing)

Average annual

wage (pla nt)

Exporter dummy

(pla nt)

1.7

Capita l per worker

Hours per worke r

Plant s ize

Firm Fixed Effects

Yea r Fixed Effects

Bernard a nd Jensen (1999)

1984

(ma nufa cturing)

Average annual

wage (pla nt)

Exporter dummy

(pla nt)

14.8

Plant s ize

Indus try Fixed Effects

State Fi xed Effects

Bernard a nd Jensen (1999)

1987

(ma nufa cturing)

Average annual

wage (pla nt)

Exporter dummy

(pla nt)

9.3

Plant s ize

Indus try Fixed Effects

State Fi xed Effects

Bernard a nd Jensen (1999)

1992

(ma nufa cturing)

Average annual

wage (pla nt)

Exporter dummy

(pla nt)

9.3

Plant s ize

Indus try Fixed Effects

State Fi xed Effects

Bernard, Jense n, Redding, a nd

Schott (2007)

2002

(ma nufa cturing)

Average annual

wage (fi rm)

Exporter dummy

(fi rm)

6.0

Firm s i ze

Indus try Fixed Effects

Rike r (2010)

2006-2008

(ma nufa cturing)

Weekly earni ngs

(i ndividual )

Export share

(i ndus try)

18.0

Indus try import s ha re

Individual educa tion

Individual a ge/a ge -s quared

Dummy for s al es /offi ce

occupati ons

Dummy for uni on partici pa tion

Gender

Race

Dummy for l ives in metro a rea

Rike r and Thurner (2011)

2006-2008

(s ervices )

Weekly earni ngs

(i ndividual )

Export-intens ive

dummy (industry)

15.8

Dummy for i ndividual a ge>=35

Dummy for coll ege graduate

Dummy for white col la r

occupati on

Gender

Race

Yea r Fixed Effects

Rike r (2015)

2014

(ma nufa cturing)

Weekly earni ngs

(i ndividual )

Export-intens ive

dummy (industry)

16.3

Dummy for i ndividual a ge>=35

Dummy for coll ege graduate

Dummy for gradua te degree

Gender

Race

State Fi xed Effects

Rike r (2015)

2014

(s ervices )

Weekly earni ngs

(i ndividual )

Export-intens ive

dummy (industry)

15.5

Dummy for i ndividual a ge>=35

Dummy for coll ege graduate

Dummy for gradua te degree

Gender

Race

State Fi xed Effects

Table 4: Summary of Export Wage Premium Literature

Note: The estimated exporter wage premia presented in this table are not directly comparable across rows, due to differences in the variables of interest, differences in control variables, and

differences in the estimation methodology.

17

Table 4 summarizes the literature on the U.S. exporter wage premium, as adapted from Table 1

in Schank, Schnabel, and Wagner (2004). Bernard and Jensen (1995) consider plant-level data on

the manufacturing industry, and ask how a given plant’s export status (a binary indicator for

whether the plant exports or not) relates to the plant’s average wage payments, controlling for

industry, region, and year effects, as well as other plant-specific variables (capital per worker,

hours per worker, plant size, plant age, and whether the plant is part of a multi-plant firm). The

interpretation of their estimated exporter wage premium is then that exporting plants pay higher

average wages than observationally-equivalent non-exporting plants located in the same region

and producing in the same industry and time-period. Riker (2010), by contrast, takes a different

approach. The author matches individuals to the industries in which they work, and relates the

individual’s earnings to her industry’s export share. His analysis controls for the worker’s location,

as well as several worker-level characteristics that influence wages, such as education, age, union

participation, gender, race, and binary variables for whether the worker is employed in a white-

collar profession and whether the worker lives in a metro area (both of which typically pay higher

wages). The interpretation of his estimated exporter wage premium is then that workers

employed in high export share industries report higher earnings than observationally-identical

workers, living in the same state, who work for low export share industries.

Therefore, it is important to note that the estimated wage differentials reported in Table 4 are

not directly comparable across rows, due to differences in the main variables of interest,

differences in control variables, and differences in the estimation methodologies, and should be

viewed as complementary estimates. On the one hand, estimates like those from Bernard and

Jensen (1995) inform us about average wages at exporting plants relative to non-exporting

plants, and estimates like those in Riker (2010) inform us about an individual worker’s wages

depending on whether the worker is employed in an exporting industry or not. In what follows,

CEA considers both cases.

Average Wages

Table 5 reports coefficients relating trade to average wages, following the same estimation

strategy that we employed in our analysis of trade and productivity—that is, we relate industry-

level exports to the industry’s average wage over the 1990s and 2000s, akin to the work in

Bernard and Jensen (1995) given data constraints. Controlling for time-invariant industry and

year factors, as well as industry size and imports, the results are suggestive of wage gains

associated with exporting, including for production workers. Notably, a 10 percent increase in

exports is correlated with a 0.1 percent increase in the industry average production wage,

suggesting average wages for production workers were about 4 percent higher than they would

have been in the absence of strong increases in U.S. export activity. This corresponds to about

$1,380 in increased earnings (in 2009 dollars) for the average production worker in the average

industry, or $1,520 in today’s dollars.

18

Individual Wages

How can exporters and non-exporters offer persistently different wages in the same product

categories? Several explanations for this feature of the data have surfaced in the literature. If

labor markets are assumed to be competitive, it is likely that while average wages at exporters

are higher, individual wages at exporters are not. Instead, it is likely that exporters hire a

systematically different type of worker; that is, more skilled workers who would earn higher

wages on average regardless of where they work—that is, at both exporters and non-exporters.

Explanations for why exporters require a higher-skilled labor force include the technological

requirements of exporting (Yeaple 2005; Bustos 2007, 2011) and that exporters produce higher

quality goods (Verhoogen 2008).

The point that wage differences between exporters and non-exporters persist even after

controlling for the observable characteristics of workers suggests departures from perfect

competition in the labor market. Amiti and Davis (2012) propose a fair-wages, rent-sharing

story—that is, exporters earn higher profits than non-exporters, which are then shared with their

workers. Alternatively, Davis and Harrigan (2011) and Frías, Kaplan, and Verhoogen (2009)

suggest that exporters may pay efficiency wages—as higher quality products require higher

quality workers, exporters pay efficiency wages to induce effort from workers. Finally, Davidson,

Matusz, and Shevchenko (2008) and Helpman, Itskhoki, and Redding (2010) argue for search and

matching frictions in the labor market. Due to complementarities between firm productivity and

worker ability, the more productive exporting firms have an incentive to screen for workers

above a given ability threshold. As higher ability workforces are harder to replace (i.e., the

screening cost is higher), multilateral bargaining over wages leads to higher wages at exporting

firms, even for very similar workers.

In order to account for some of the observable differences across workers who sort into exporting

industries, in Table 6, we consider a simple analysis using data on individual-level annual earnings

Log Average Wage Log Average Production Wage

Log Exports

0.007 0.010*

(0.004) (0.006)

Indus try Fi xed Effects YES YES

Yea r Fixed Effects YES YES

Control for Imports YES YES

Control for Indus try Si ze YES YES

Observa tions 7,961 7,961

Table 5: Trade and Average Wages

Note: Average wages are defined as total payroll per employee. Average production wages are defined as total production payroll

per production worker. Industry size is defined as the inflation-adjusted value of total shipments by U.S. firms. Robust standard

errors, clustered at the industry level, are in parentheses. *** denotes significance at the 1-percent level, ** denotes significance at the

5-percent level, and * denotes significance at the 10-percent level. The panel dataset comprises over 370 industries over the 1989-

2009 period. Industries are defined according to NAICS and are disaggregated to the six-digit level.

Source: Data on payroll, production payroll, employment, production employment, total shipments, and industry-specific price

indices are from the NBER M anufacturing Industry Database. Data on imports and exports by industry from 1989-2006 are from the

U.C. Davis Center for International Data. Data on imports and exports by industry from 2007-2009 are from the Foreign Trade

Division of the U.S. Census Bureau.

19

from the Current Population Survey (CPS) for the years 1989 to 2009. Closely following the work

in Riker (2010), the data match individual workers to the industries in which they work. The

regression then relates the level of exports in an industry to the individual’s earnings. Even when

controlling for differences in worker characteristics such as gender, education, race, and age,

differences in workers’ employment through industry fixed effects, and differences in workers

locations through state fixed effects, CEA confirms an exporter wage premium. CEA’s analysis

suggests that the strong increase in exports over the 1990s and 2000s translates into an

additional $1,300 in annual earnings for workers in today’s dollars.

6

Foster Access to Foreign Markets Without Outsourcing

A common criticism of U.S. FTAs is that U.S. firms will shift production and employment away

from the United States to our trading partners, assumed to have lower labor standards and lower

wages, in order to cut labor costs by effectively sending U.S. jobs abroad.

One motivation for FDI is to circumvent barriers to sales abroad—so to the degree that trade

agreements eliminate these barriers they make it easier to produce in the United States and

export abroad.

In addition, to the degree that trade agreements—directly or indirectly—raise labor standards

they can reduce some of the incentives that lead to outsourcing. Relying on data across many

countries over the 1980s and 1990s, Palley (2005) makes the case that higher labor standards are

6

More importantly, our analyses in Table 5 and Table 6 find no statistical relationship between increases in imports

and earnings. Any potential downside to workers’ wages due to import competition appears to be offset by the

benefits of increased imports of intermediate inputs (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2008).

Log Annua l Ea rnings

Log Exports 0.012*

(0.007)

Indus try Fixed Effects YES

State Fi xed Effects YES

Year Fixed Effects YES

Control for Imports YES

Control for Industry Size YES

Observa ti ons 224,055

Table 6: Trade and Individual Wages

Source: Data on earnings by industry are from the U.S. Census Bureau, Current

Population Survey, as downloaded from the IPUMS-CPS, University of Minnesota.

Data on imports and exports by industry from 1989-2006 are from the U.C. Davis Center

for International Data. Data on imports and exports by industry from 2007-2009 are

from the Foreign Trade Division of the U.S. Census Bureau. Data on total shipments by

industry are from the NBER M anufacturing Industry Database.

Note: Robust standard errors, clustered at the industry-year level, are in parentheses. ***

denotes significance at the 1-percent level, ** denotes significance at the 5-percent

level, and * denotes significance at the 10-percent level. The panel dataset comprises 75

industries over the 1989-2009 period. Industries are defined according to the 1990

Census Bureau industrial classification system.

20

associated with higher wages. Olney (2013) documents that foreign investment is responsive to

labor market standards in other countries. Using data on FDI abroad by U.S. companies, the

author finds that Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries

with fewer employment protections received more U.S. FDI, offering some suggestive evidence

of a wider globalization-inspired race-to-the-bottom on employment protections.

7

This logic is

why current and future U.S. trade agreements directly embed strong and enforceable labor

commitments into their main texts (see Section IV for more information on current trade

negotiations). Moreover, the results in Palley (2005) and Olney (2013) together suggest that by

increasing enforceable labor standards, and thus increasing wages, abroad though our trade

agreements, the United States can potentially curb the outsourcing of American jobs.

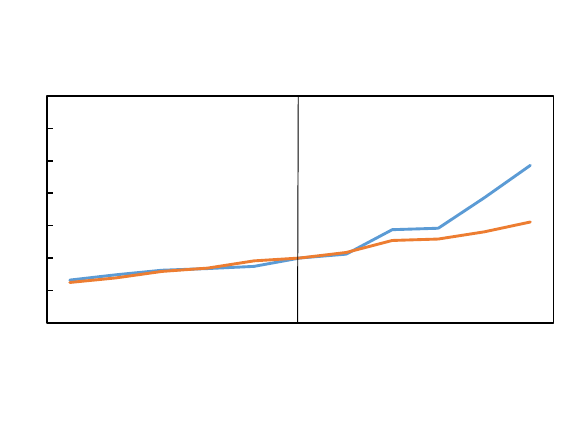

Figure 3 summarizes the evolution of the stock of U.S. FDI in our free trade partners before and

after the enactment of all 14 FTAs (across 20 countries).

8

For a baseline comparison, the analysis

also presents the evolution of the stock of U.S. FDI in non-FTA partners before and after our FTAs

entered into force. By construction, time zero is the date of entry into force of the agreement.

Our analysis of the relationship between U.S. trade agreements and outsourcing documents that

the stock of U.S. FDI in our FTA partners shows no notable increase after enactment of the

agreement relative to the increase in U.S. FDI in our non-FTA partners post-enactment.

Specifically, looking at GDP-weighted averages of the stock of investment over time, Figure 3

shows that, on average, U.S. FDI in our FTA partners grew by 6.3 percent per year in the five years

7

The employment protections measure used in the paper is only available for OECD countries, and thus many less-

developed countries are not included in the sample. However, that the paper finds an economically significant

relationship among OECD countries suggests that the relationship identified may be even stronger among a wider

set of countries.

8

The analysis that follows uses data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) on direct investment positions

valued on a historical cost basis. According to Ibarra-Caton and Mataloni (2014), the historical-cost value largely

reflects prices at the time of the investment.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

-5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5

Years from FTA Enforcement

Stock of Real FDI as Percent of FDI at FTA Enforcement

GDP-Weighted Average

across All Countries

Except FTA Partners

GDP-Weighted Average

across FTA Partners

Figure 3: Stock of Real U.S. FDI Abroad

Around U.S. Free Trade Agreements

Note: All values in real 2009 dollars, deflated using the U.S. GDP deflator.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Direct Investment Position; International Monetary Fund,

World Economic Outlook; CEA Calculations.

21

pre-FTA enforcement, close to the growth rate of U.S. FDI in our non-FTA partners in the five

years leading up to FTA enforcement (8.1 percent per year). There was essentially no trajectory

change in the annualized growth rate of U.S. FDI in our FTA partners in the five years following

FTA enactment (at 8.4 percent).

Given that one motivation for FDI abroad is to circumvent foreign trade barriers in order to serve

the foreign market, this is perhaps not surprising. In fact, some FDI may have been replaced by

U.S. exports to those markets post-FTA enforcement (as is suggested in Figure 7-5 of CEA

(2015a)), offsetting other potential increases in U.S. FDI associated with the liberalization of rules

on overseas investment in the new FTA. Therefore, the evidence in Figure 3 suggests that U.S.

firms do not increase net outsourcing when the United States enters FTAs. Although some

production could shift offshore to take advantage of new FTA rules, other production that would

have shifted offshore could end up staying in the United States, thanks to our improved access

to foreign markets.

Figure 4 reports the stock of U.S. FDI in China’s free trade partners. In this case, the data show

unambiguously that when China enters into FTAs, U.S. firms send more foreign investment

abroad (outsource more) to China’s free trade partners. Likely, U.S. companies take advantage

of the preferential access to the Chinese market—a key spoke in the global supply chain—

without any countervailing incentives to increase production in the United States (due to reduced

trade barriers abroad). Specifically, while the stock of U.S. FDI to China’s FTA partners and non-

FTA partners grew by around 9-10 percent per year before China’s FTAs entered into force, real

growth of U.S. FDI in Chinese FTA partners increased to 20 percent per year after China’s

agreements entered into force, without any comparable change in the growth rate of U.S. FDI in

China’s non-FTA partners.

The trends documented in the previous two charts are further supported by data on other

measures of multinational activity around U.S. and Chinese FTAs.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

-5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5

Years from FTA Enforcement

Stock of Real FDI as Percent of FDI at FTA Enforcement

GDP-Weighted Average

across All Countries

Except FTA Partners

GDP-Weighted Average

across FTA Partners

Figure 4: Stock of Real U.S. FDI Abroad

Around Chinese Free Trade Agreements

Note: All values in real 2009 dollars, deflated using the U.S. GDP deflator.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Direct Investment Position; International Monetary Fund,

World Economic Outlook; World Bank, World Development Indicators; CEA Calculations.

22

There are many potential explanations for the descriptive evidence presented in the figures

above—for example, there are differences in the types of countries that the U.S. engages with in

FTAs as compared with the types of countries with which China engages. Nevertheless, the trends

in the data are broadly consistent with the idea that U.S. FTAs do not actually encourage

outsourcing abroad. Instead, what may increase the outsourcing of American jobs is to remain in

the status quo; that is, without the United States to set high-quality labor standards around the

world, other countries enter into FTAs of their own and become magnets for outsourcing from

the United States. Further research on the relationship between trade agreements, FDI, and jobs

can help to elucidate these effects.

9

Development Effects of Trade

The United States engages in international trade and trade agreements to increase market-access

opportunities for U.S. businesses and workers and to lower prices and increase options for U.S.

consumers. In addition to these benefits, it is important to recognize the positive impact trade

has on global growth and security. The United States benefits directly when the rest of the world

is more prosperous and secure—providing a bigger and more stable market for American

exports. U.S. trade policy also has implications for labor rights in our trading partners, gender

equality, and environmental sustainability.

Increased Economic Growth

When countries specialize in the goods and services they can produce relatively efficiently and

trade for the rest, world production and consumption increase as existing global resources are

more effectively utilized. Simple international trade theory, therefore, suggests that increased

international trade can boost incomes. However straightforward this may seem, it is actually

quite difficult to discern empirically a causal relationship between trade and income. For

instance, countries may trade more because they are richer. Richer countries have better trading

infrastructure, such as good ports, and better access to information about opportunities abroad.

The fundamental challenge for statistical inference, then, is that while trade may affect income,

income also affects trade.

An extensive body of work examines the empirical association between trade openness and per

capita income growth. Frankel and Romer (1999) were among the first to attempt to establish a

causal picture of the impact of trade on income, arguing that the geographic placement of

countries provides a way to isolate a component of trade that is unrelated to income except

through its effect on trade. The authors use the distance between countries to predict the

amount of their bilateral trade, relying on the well-established relationship that proximity is a

strong predictor of trade flows (the so-called “gravity model”). Because a component of trade

flows isolated in this manner is highly correlated with income, the authors conclude that trade

has a positive causal effect on income.

9

Please see CEA (2015b) for further discussion of the relationship between FTAs and outsourcing.

23

Recent work argues that this approach should be refined to reflect that the distance between

countries may be related to non-trade determinants of income. For example, as documented by

Acemoglu et al. (2001), current economic development may depend directly on early economic

differences that have persisted over time, for example, differences related to geography and

climate. Changes in economic distance can help to isolate the impact of transportation costs on

income as these operate through the trade channel. Feyrer (2009a) relies on a unique event in

recent world history to identify changes in distance between country-pairs—the closure and re-

opening of the Suez Canal between 1967 and 1975. For some countries, this increase in sea

distance was substantial, and trade between such country-pairs dropped by 20 percent. Since

some country-pairs were not affected by the closing, it offers a unique experiment to test how

trade impacts income. The author concludes that every dollar of increased trade raises income

by about 25 cents.

Relying on another unique measure of time-varying distance between countries to predict

international trade, Feyrer (2009b) documents again the importance of international trade for

incomes. In this second paper, the author recognizes that the rapid progress in aircraft

technology in recent years dramatically changed the effective distances between countries—

goods that previously had to circumvent large land masses by ship, can now travel by air via the

great circle distance. These changes, therefore, differentially benefited pairs of countries linked

by relatively short air routes as compared with sea routes. Using country-specific, time-varying

measures of sea distance and air distance, the author concludes that trade has a significant

positive effect on income, such that a 1 percent increase in trade raises real income by 0.5

percent.

Trade’s potential to raise real income growth in U.S. trading partners holds substantial potential

benefits for us. Growth in our trading partners increases the demand for U.S. exported goods.

Figure 5 illustrates the strong correlation between growth in U.S. exports and growth in the rest

of the world.

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

-4 -2 0 2 4 6

Figure 5: U.S. Export Growth vs. Foreign GDP Growth,

2000-2014

Real U.S. Export Growth, Percent Year-Over-Year

Trade-Weighted Foreign GDP Growth, Percent Year-Over-Year

Note: Data displayed are quarterly year-over-year growth rates.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts; National Sources

via Haver Analytics.

24

Poverty

The world has made historic progress in reducing poverty in recent decades. The total number of

poor people around the world fell by nearly half a billion between 2005 and 2010, and the

numbers are estimated to fall further in coming years at rates never before seen in history

(Chandy and Gertz 2011). Largely due to growth in China and India, across-country global income

inequality recently witnessed the first decline since the Industrial Revolution (Milanovic 2013). A

range of research shows that trade has played a role in these developments.

Hanson (2007) investigates the case of Mexico in the decade surrounding the implementation of

the North American Free Trade Agreement between Canada, Mexico, and the United States.

Using state-level variation, the author documents that individuals born in states with high-

exposure to globalization have relatively higher wages than individuals born in states with low-

exposure to globalization. McCaig (2011) uses the 2001 U.S.-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

(BTA) to study the effects of increased market access to rich countries on poverty in developing

countries and finds that a one standard deviation decrease in provincial tariffs is associated with

a two-year rate of poverty reduction of between 33 and 40 percent. By contrast, work by

Topalova (2007, 2010) on India’s 1991 trade liberalization provides a different view. Although the

incidence of poverty in rural India fell 13 percentage points around the liberalization—from 37

percent in 1987 to 24 percent in 1999—areas of that country more exposed to trade experienced

progress toward poverty reduction that was not as rapid as other areas.

Better Working Conditions

A common argument against trade integration with countries in the developing world is the poor

labor standards of those countries. However, research finds that expanding access to U.S.

markets promotes higher-quality employment in less-developed countries as workers shift from

informal to formal employment, with little empirical evidence that local tariff reductions have an

offsetting effect—meaning that the forces unleashed by trade itself complement the effort to

include enforceable labor standards in our FTAs.

A recent paper by McCaig and Pavcnik (2014) finds that employment shifts from the household

business (informal) sector to the formal enterprise sector in Vietnam in the aftermath of large

U.S. tariff reductions as part of the U.S.-Vietnam BTA. Similarly, Paz (2014) reports that decreases

in foreign market tariffs decrease domestic informal employment in Brazil, while early work by

Goldberg and Pavcnik (2003), supported in Menezes-Filho and Muendler (2011), finds no

evidence of a link between declining import tariffs in Brazil and informal employment. More

importantly, work by Edmonds and Pavcnik (2005) documents a decrease in child labor

associated with increased international trade in Vietnam.

This is important because jobs in the informal sector are associated with lower wages, lower

employee benefits, worse working conditions, and lower job quality. McCaig and Pavcnik (2014)

report that workers in household businesses earn about 14 percent less than observationally

equivalent workers in the formal sector (in the same industry, province, and occupation).

Workers that switch to formal work (controlling for unobserved worker characteristics) earn

about 5 percent more than when they worked in a household business. Relying on information

25

from the Colombian National Household Survey, Goldberg and Pavcnik (2003) offer evidence that

informal sector work is associated with lower job and workplace satisfaction, very few benefits,

lower incidence of job training, and higher uncertainty about duration of employment. Formal

workers are more likely to receive individual benefits such as health coverage, dental coverage,

vacations, incentive bonuses, maternity leave, unemployment benefits and pensions, sick leave,

transportation benefits, insurance, and family subsidies. In fact, 83 percent of informal workers

report receiving no benefits through their job—this number is only 4 percent for formal workers.

Therefore, trade agreements that expand U.S. market access for countries at a lower level of

development can provide a market-based approach to improving labor conditions in the

developing world.

10

High standard U.S. trade agreements also contain commitments to promote

and enforce workers’ rights. In fact, Dewan and Ronconi (2014) analyze whether FTAs signed

between the United States and Latin American countries during the last decade produced higher

enforcement of labor regulations. Their estimates suggest that signing an FTA with the United

States increased both inspection resources (the number of inspectors) and inspection activities

(the number of inspections).

In addition, recent studies by the Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) of the U.S.

Department of Labor (DOL) assess the advancement of U.S. preferential trading partners in

combating the worst forms of child labor (ILAB 2012, 2013, 2014), as required by the Trade and

Development Act of 2000. Table 7 presents simple statistics based on data in these reports.

11

Across all three years, U.S. FTA partners were more likely than non-FTA partners to be assessed

by DOL as having “significantly advanced” in combating child labor. In particular, in 2013, 36

percent of U.S. FTA partners “significantly advanced,” while only 7 percent of non-FTA partners

“significantly advanced.” In fact, five of the 13 countries that DOL assessed as having “significantly

advanced” are U.S. FTA partners. Meanwhile, while approximately 11 percent of non-FTA

partners were assessed in 2013 as having made “no advancement,” no U.S. FTA partners were in

this category. Over all three years of data availability, U.S. FTA partners were less likely to make

“no advancement”.

10

Salem and Rozental (2012) provide a review of the literature on labor standards and trade.

11

Admittedly, these data provide only suggestive correlative evidence, and cannot be used by themselves to infer a

causal relationship.

26

In addition to the assessments in each year, Table 7 also documents that as a group FTA partners

were more likely to earn improved assessments over time. Notably, between 2011 and 2013, the

likelihood that an FTA partner “significantly advanced” increased by 27 percentage points, as

compared to only a 6 percentage point increase for non-FTA partners. Moreover, in the three

years of data, no FTA partner was ever assessed to have regressed in combating child labor. By

contrast, between 2011 and 2012, 9 percent of non-FTA partners regressed, and between 2012

and 2013, 16 percent of non-FTA partners saw downgraded assessments.

Finally, though most U.S. FTAs entered into force long before DOL began reporting on countries’

advancement in combating the worst forms of child labor, two countries (Colombia and Panama)

entered into free trading arrangements with the United States over the period of assessment.